Abstract

This article discusses a distinct function of the third person singular pronominal clitic =eš in Persian: to denote definiteness. In certain possessive constructions, =eš does not refer to an external possessor but serves to make its host identifiable – whether through association with another item in the linguistic or situational context or as an anaphoric definite marker without any association. The use of possessive markers for definiteness has been observed in Uralic, Trans-Eurasian, Austronesian, Semitic, and Mayan language families; this study presents evidence of a similar development in Persian, an Indo-European language of the southwestern Iranian branch. The present article examines various definite uses of =eš through colloquial examples from social media and historical examples from a New Persian corpus. The findings trace the development of =eš, illustrating how its associative link to external entities weakens over time until it functions as an anaphoric definite marker. A tentative grammaticalization path is proposed in which the abstraction of the possessive meanings leads to the eventual loss of possessive semantics in =eš, resulting in the loss of person and number features in anaphoric uses. Additionally, the article discusses how increasing frequency of =eš has contributed to its development across stages of New Persian.

1 Introduction

The third person singular pronominal clitic =eš [1] in Persian, a Southwestern Iranian language, serves multiple functions, one of which is to mark possession, as shown in example (1c). In addition to its use in adnominal possessive constructions, =eš also exhibits several non-possessive functions. This article focuses on one such function – marking definiteness – by analyzing a range of examples in which =eš appears as a definite marker.

In Persian, possessive constructions are head-marked. In these constructions, the possessed can be marked by an Ezafe particle[2] followed by a possessor as either a nominal or a free pronoun, or it can be marked by a pronominal clitic serving as the possessor of the construction. Examples in (1) illustrate the three forms of possessive constructions in Persian respectively, among which the third form, featuring the third person singular pronominal clitic (pc.3sg) as possessor (1c), is the focal point of this article.

| Māšin=e | mahsā. |

| car=ez | Mahsa |

| ‘Mahsa’s car.’ | |

| Māšin=e | u. |

| car=ez | pn.3sg |

| ‘Her car.’ | |

| Māšin=eš. |

| car=pc.3sg |

| ‘Her car.’ |

However, there are examples in Persian where the pc.3sg, although present as a possessive clitic in adnominal constructions, does not convey a possessive meaning and cannot be classified as pronominal or possessive. Instead, it serves various other functions, as illustrated in examples (2). The role of the pc.3sg in (2a) has previously been identified and discussed as a contrastive-partitive function (Etebari et al. 2020), which evolved from its original possessive use. In this context, the clitic indicates that the two entities belong to a similar set while contrasting with one another. This article focuses on another non-possessive function of the pc.3sg, as demonstrated in example (2b), where it is employed to render an item identifiable. In this case, the clitic is used to convey definiteness. Here, the pc.3sg does not refer to any entity as the possessor of ketāb ‘book’ but serves a definite function to specify which book is being referred to. In none of these examples do the clitics refer to explicit nominal items in the co-text or context that could be interpreted as possessors.

| Vaqti | ǰavun=ā=š | in | hame | dardmand=an, |

| when | young=pl=pc.3sg | dem | all | afflicted=cop.prs.3pl |

| be-bin | pir=ā =š | četor=an. | ||

| sbjv-see.prs | old=pl=pc.3sg | how=cop.prs.3pl | ||

| ‘When the young people are this much in pain, look how the old ones are.’ | ||||

| (http://programmeridea.blogfa.com/post/17, posted 30 September 2011) | ||||

| Xund-i=š 3 ? | |||

| read.pst-2sg=pc.3sg | |||

| āre, | ketāb =eš | xub | bud-Ø. |

| yes | book=pc.3sg | good | cop.pst-3sg |

| – ‘Did you read it?’ | |||

| – ‘Yes, the book was good.’ | |||

| (Jahanpanah 2001: 25) | |||

- 3

Note that pronominal clitics in Persian fulfill various functions, one of which is possessive. Additionally, they can function as core arguments, as demonstrated in this example.

This phenomenon is commonly referred to in the literature as the non-possessive, non-prototypical, secondary, extensive, or discourse uses of possessive markers, and it is considered a typical feature of the Uralic and Trans-Eurasian language families. Generally, possessive markers (affixes/clitics) across languages are employed to indicate possessors in possessive constructions, conveying relationships such as ownership, kinship, whole-part, and attribution (Aikhenvald 2012). However, research has demonstrated that possessive markers in several languages have evolved to express functions that extend beyond traditional possessive meanings, including contrast, emphasis, topicality, and definiteness. This indicates that they do not refer to any nominal possessor present in the syntactic structure or situational context. These developments have primarily been observed in various languages within the Uralic (Abondolo and Valijärvi 2023; Collinder 1957, 1960; Gerland 2014; Havas et al. 2023; Janda 2015; Kiss 2018; Nikolaeva 2003; Tauli 1966) and Trans-Eurasian (Grönbech 1936; Janhunen 2003; Johanson and Csató 2022; Nikolaeva and Tolskaya 2011; Nilsson 1985; Schlachter 1960; Schroeder 1999; Serebrennikov 1963) families, but they have also been identified in a few languages from other families, including Semitic (Armbruster 1908; Huehnegard and Pat-El 2012; Kapeliuk 1994; Leslau 1995; Rubin 2010), Austronesian (Ewing 1995; Sneddon 1996), Mayan (Lehmann 1998), and Indo-European[4] (Etebari et al. 2020).

This article aims to describe the various uses and the distribution of the pc.3sg as a definite marker in New Persian. It also proposes a tentative path for the clitic transition from marking possession to expressing definiteness. Persian history is divided into three stages: Old Persian (6th–4th BCE), Middle Persian (3rd BCE–9th CE), and New Persian (10th CE onward). In the New Persian period, pronominal clitics lost their second-position constraint and developed into proclitics. Consequently, they began to serve as possessors in adnominal constructions, a function that was absent in earlier stages of the language. The development of possessive PCs in New Persian and the semantic relations they convey have been analyzed by Etebari (2020) and Etebari et al. (2023). The current study seeks to investigate how the definite uses of the pc.3sg in Persian aligns with the different categories of definiteness introduced in linguistic theory, particularly in Hawkins (1978). Are they limited to associative and situational contexts, or do they have anaphoric uses? Does this usage appear across different centuries of New Persian, or is it a more recent development? How far does it advance along the grammaticalization path, and are these uses obligatory? The study examines whether there is a diachronic shift in the usage of the clitic, and whether its definite function correlates with the frequency of its possessive use over time. The results provide further evidence for the capability of possessive markers to be source of grammatical definite markers.

The current analysis is based on data from a historical corpus of 500,000 words (Etebari 2020), consisting of 33 prose samples from various centuries of New Persian (see Table 1 in the Appendix). Each sample contains 1,500 words, and three manuscripts from three different authors are selected per century. The selection criteria are as follows: first, the simplicity of the language, to minimize the influence of literary style, rhythm, and figures of speech on the usage of PCs. Second, the narrativity of the texts, which allows for the identification of clitics with various person and number features. Therefore, the manuscripts chosen include genres such as fiction, historiography, and travelogues, all of which feature storytelling and dialogue. Third, the dates of the texts must be reliably established. From this half-million-word corpus, approximately 2,500 constructions involving possessive pronominal clitics are extracted and analyzed. Additionally, colloquial Persian is examined to determine if there are any differences in usage and to provide further insight. The use of pronominal clitics is notably more frequent in colloquial Persian. The colloquial examples presented in this article are sourced from social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of research on the development of possessive markers that convey definite functions across various language families and introduces previous approaches to definiteness marking. In Section 3, different definite uses of the Persian pc.3sg are discussed through illustrative examples. Section 3.1 examines the associative function of the pc.3sg, which diverges from its possessive role. Section 3.2 discusses how contextual definiteness emerges from this associative function, while Section 3.3 highlights non-associative anaphoric uses of the pc.3sg as a definite marker. Section 4 presents preliminary remarks on the grammaticalization path of the pc.3sg into a definite marker, focusing on the factors of obligatoriness and frequency in these developments. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key discussions of the article.

2 Previous approaches

Definiteness is traditionally defined based on two characteristics: identifiability (or familiarity) and inclusiveness (or uniqueness). Identifiability involves cases where the identity of an item is known to both speaker and hearer. Uniqueness, on the other hand, does not necessarily imply familiarity but rather that only one entity exists “satisfying the description used” (Lyons 1999: 8). Jesperson (1924) defines definiteness as the familiarity of a linguistic item, determined with four different contexts. Familiarity may arise from an “explicit contextual basis” where a referent is introduced in prior linguistic discourse, or an “implicit contextual basis”, in which the item is familiar by association with another previously mentioned entity – also known as “associated anaphoric use”. Familiarity can also be based on a “situational basis”, where the identity of the entity is inferred from a non-linguistic context, whether immediate or broader. Lastly, a “constant situational basis” underlies cases “the sun”, aligning with the uniqueness feature (Lyons 1999: 254).

The difference between implicit contextual and situational bases is that “with the latter there is no overt mention of the thing providing the contextual basis” (Lyons 1999: 254). This distinction is applied in the present study’s analysis. Building on Jespersen’s framework, Hawkins (1978) categorizes different uses of the English the, described below. This categorization is frequently applied in analyzing various uses of definite markers, including possessives, across languages (Hawkins 1978: 106–130):

Anaphoric uses

In simple, e.g., a book: the book, and more complicated sequences, e.g., a lathe: the machine or X travelled: the journey.

Visible or Immediate situation uses

In, e.g., Pass me the bucket where the item is visible to both speaker and hearer or in, e.g., beware of the dog where the item does not need to be visible to both parties.

Larger situation uses

In, e.g., the church, the queen, or the earth for members of the same village, nation or planet.

Associative anaphoric uses

In, e.g., a book: the author, a house: the roof, a car: the length, or a wedding: the bride with the notions of “part-of” or “attribute”, and as the most frequent uses of the.

Some scholars, among them Löbner (1985) and Himmelmann (1996), distinguish pragmatic from semantic definiteness based on whether the identification of an item relies on situational context or is independent of it. Within this framework, semantic definiteness corresponds to direct anaphoric uses of definite markers, with a progression from pragmatic to semantic definiteness marking a shift toward “the status of full-fledged definite article” (De Mulder and Carlier 2011: 8). The definite article is described as a morpheme that accompanies nouns, indicating their definiteness or specificity (Dryer 2013). Lyons (1999) describes this stage as grammatical definiteness, defining it as the grammaticalization of identifiability – a concept rooted in pragmatics and tied to information structure. He contrasts grammatical definiteness with the definiteness function of possessive markers, which he considers a non-grammatical type of identifiability (Lyons 1999: 278).

Also, Becker (2021) differentiates between definite articles and potential definite markers, including possessives in Uralic languages. She notes that while possessives may extend to referential functions, their occurrence is largely shaped by discourse-pragmatic factors. The possessive and definite functions overlap, but possessives in these languages do not systematically mark definite reference, nor are they obligatory, thus remaining on the gradual grammaticalization path toward definiteness (Becker 2021: 13). As a result, it is difficult to distinguish such possessive markers from definite articles. Becker (2021: 34) emphasizes that this distinction “requires clear, language-independent criteria”.

Using Hawkins’ (1978) categorization and introducing the concept of “anchor” as an associative referent, Fraurud (2001) describes various uses of possessive markers with a definite function in languages such as Komi and Udmurt (Uralic), Turkic (Trans-Eurasian), and Yucatec (Mayan). An anchor, in this context, is any linguistic or non-linguistic element associated with the referent of an item marked by a possessive, helping to establish its definiteness (Fraurud 2001: 252–253). Fraurud asserts that in these languages, possessives with a definite function are predominantly associative, indicating an association between the possessively marked item and another contextual element; anaphoric uses, while possible, are relatively rare.

These languages, however, also exhibit a non-associative or direct anaphoric definite function. Simonenko (2014) argues that the third singular possessive suffix in Komi “has the same grammatical status as the English definite article”, encompassing all four categories of Hawkins’ (1978) classification. Similarly, Collinder (1960: 203) and Tauli (1966: 148) describe this marker in Uralic languages – excluding Finnish, Sami, Mordvin, and Hungarian – as an equivalent or corresponding to the definite article in the Indo-European languages. Gerland (2014) further notes that possessive affixes in Komi, Udmurt, Nganasan, and Mari can express all four definiteness categories, suggesting a potential grammaticalization pathway for these markers. Nikolaeva (2003: 135) also affirms that the definite uses of the third possessive affix in Uralic are comparable to the uses of the definite article in article languages, aligning with all of Hawkins’ categories. However, she adds that this marker is not fully grammaticalized, as its use remains non-obligatory within the Uralic family (Nikolaeva 2003: 135).

In Turkic languages, Schroeder (1999) provides examples from Turkish in which the third person singular possessive suffix has a “definitizing” function, although he argues that these definite uses are primarily associative (or relational, as he terms it) and do not convey direct anaphora. Grönbech (1936) and Kononov (1956), however, suggest a more advanced development, asserting that this suffix in Turkish has already evolved into an article. Johanson (1991) counters this view, contending that these definite uses are not systematic and thus cannot be considered fully developed articles (Fraurud 2001: 248). Menges (1968: 113) also notes that in certain Trans-Eurasian languages, including Turkish, “the possessive significance of the suffix of the third person can completely recede when it defines or determines a noun”, in which case it functions similarly to an article in Indo-European or Semitic languages. Comparable observations have been made for other Turkic languages, such as Chuvash (Grönbech 1936; Benzing 1993), Tatar (Serebrennikov 1963), Sakha (Pakendorf 2007), Dolgan (Stachowski 2010), as well as some Tungusic and Mongolic languages like Udihe (Nikolaeva and Tolskaya 2011) and Khamnigan Mongol (Janhunen 2003).

This phenomenon extends beyond Uralic and Trans-Eurasian families. The definite function is also present in the possessive affixes of certain Austronesian languages, such as Colloquial Jakartan Indonesian (Englebretson 2003; Himmelmann 2001; Rubin 2010; Sneddon 1996) and Cirebon Javanese (Ewing 1995). Rubin (2010) notes a distinction between formal and colloquial Indonesian: in both, the third singular possessive denotes contextual definiteness, while in colloquial use, it can additionally signal anaphoric definiteness. Similar developments are attested in several Semitic languages, primarily from the Ethiopic branch, such as Amharic, Ge’ez, Akkadian, Argobba, Harari, and Chaha (Appleyard 2005; Armbruster 1908; Leslau 1995; Rubin 2005, 2010). In these languages, the definite article and the third person possessive suffix are identical, with the article commonly believed to have derived from the possessive form (Rubin 2005: 89). Rubin (2010) and Landsberger (1948) show that in Chaha and Akkadian, the definite article marks contextual definiteness, whereas in Amharic, it has further developed to express anaphoric definiteness as well (Rubin 2010: 112). The definite uses of possessive markers also appear in Yucatec Maya, where they function similarly to the English definite article (Lehmann 1998).

Definiteness marking in Persian remains a topic of debate. It is commonly believed that written Persian lacks a true marker for definiteness, relying instead on bare nouns or demonstratives to express it. In addition, the postnominal object marker rā serves to denote both functions of definiteness and specificity (Dabir-Moghaddam 1990; Karimi 2003). In colloquial Persian, the suffix -e marks nouns and adjectives to signal identification (Lazard 1957; Rasekh-Mahand 2009). Recent studies by Nadimi and Ataei (2018) and Nourzaei (2023) have demonstrated that the -e suffix is not limited to colloquial usage but also appears in written Persian. These scholars trace the suffix back to earlier stages of Persian, suggesting that it evolved from an evaluative marker, referred to as the k-suffix by Nourzaei (2023). Similar developments can be observed in other Iranian languages, such as Balochi and Kurdish (Haig 2018), where k-suffixes also serve to denote definiteness. Despite its use across various definiteness categories in Persian (Nourzaei 2023; Rasekh-Mahand 2009), the -e marker is highly variable and dependent on factors such as speaker, genre, and context (Nourzaei 2023). Moreover, von Heusinger and Sadeghpoor (2020) argue that in colloquial Persian, -e can combine with indefinite markers, where it signals specificity rather than definiteness (see example [8c]).

Definite uses of possessives within the Iranian language family have not received significant attention. Thus far, they have primarily been identified in Persian, specifically related to the third-person singular pronominal clitic. A handful of studies (Etebari et al. 2020; Ghatreh 2007; Jahanpanah 2001; Rasekh Mahand 2009; Shaqaqi 2014) have noted that the pc.3sg in colloquial Persian functions as a definite marker. Rasekh Mahand (2009: 90) further emphasizes that this marker conveys anaphoric definiteness, referring to nouns previously mentioned in discourse rather than relying on situational context or general knowledge. The following section will explore the various definite uses of the pc.3sg in Persian.

3 Definite uses of the third person singular clitic =eš in Persian

Possessives in Persian express a wide range of meaning relations. Research by Etebari (2020) and Etebari et al. (2023) identifies 21 distinct meaning relations conveyed by possessive constructions which include a possessive clitic. Among these, the associative relation stands out; it signifies a connection between the possessor and the possessed that does not align with traditional meanings of possession – such as ownership, kinship, whole-part relationships, or attribution – but rather indicates a general association between the two items. Drawing on Hawkins’ (1978) categorization of definite uses, outlined in Section 2, I will now discuss how the definite function of the pc.3sg in Persian emerges from this associative meaning relation.

3.1 Associative definiteness

While the associative anaphoric function identified in Hawkins’ (1978) categorization is generally represented by possessive pronominal clitics (PCs) in Persian, in this section, I will explore instances where the pc.3sg transitions away from its possessive function and instead indicates definiteness through its association with another item.

Before delving into examples featuring the =eš clitic in its associative definite function, I will first examine the associative meaning relations present in Persian possessive constructions, which can involve pronominal clitics across all persons and numbers. For instance, example (3) illustrates a possessive construction in which the relationship between the possessor and the possessed cannot be inferred solely from the components of the construction. Instead, additional context is necessary to clarify the association. In this case, depending on the context, the term dozdat ‘your thief’ could indicate the thief who has stolen from you, the thief who previously kidnapped you, or the individual for whom you are seeking assistance, such as when addressing a police officer.

| Dozd=at | rā | peydā | karde=am. |

| theif=pc.2sg | obj | found | do.ppf=1sg |

| ‘I have found your thief.’ | |||

| (Hossein Kord Shabestari, 10th AH/16th CE) | |||

In these constructions, the possessed is associated with the possessor, but the relation is more complex or indirect. This article claims that the development of =eš into a definite marker began within possessive constructions with associative relation. While in typical associative possessive constructions the PCs correspond to explicit nominal items, similar constructions also occur in which the referents are less explicitly defined. In example (4a), the marker =aš is not used with its possessive function but rather signals associative definiteness with regard to harf ‘talk’. The sentence implies that we talk easily when it is the (right) time to talk, and the time is familiar to the hearer because it is associated with harf ‘talk,’ marked by =aš. Similarly, in (4b), =eš acts an associative definite marker, making arzeš ‘value’ identifiable through its association with the previously mentioned čiz ‘thing’. Here, arzešeš is neither a possessive construction nor is =eš functioning as a possessor. In the examples in (4), the referential relationship has been weakened, with the previous mention serving to make the possessed item identifiable. Though identifiability is achieved through this associative link, there is no explicit nominal item within the text to which =eš directly refers or could act as a possessor.

| Harf | be | vaqt=aš | mi-keš-ad. |

| talk | to | time=pc.3sg | ipfv-draw-3sg |

| ‘Talking will be easy at the right time.’ | |||

| (Charand-o Parand, 14th AH/20th CE) | |||

| Age | ye | čiz-i | hanuz | zehn=et=o | dargir.karde=Ø | ||

| if | a | thing-indf | still | mind=pc.2sg=obj | prey.do.ppf=3sg | ||

| arzeš =eš | ro | dār-e | ke | barāye | be.dast.āvord-an=eš | ||

| worth=pc.3sg | obj | have.prs-3sg | that | for | to.hand.bring-inf=pc.3sg | ||

| risk | kon-i. | |||||||

| risk | do.sbjv-2sg | |||||||

| ‘If something continues to weigh on your mind, it’s worth taking the risk to achieve it.’ | ||||||||

| (https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=2440089066275594, posted 5 Oct 2019) | ||||||||

To clarify this process, the three examples in (5) illustrate how the referential link between the nominal possessor and =e/aš becomes progressively weaker. Examples (5a) and (5b) come from classical Persian (15th and 16th centuries, respectively), and example (5c) is from contemporary colloquial Persian. Both examples (5a) and (5b) involve two temporal concepts linked associatively. In (5a), the referent of =aš, i.e., ruz ‘day’, is explicit and available in the close linguistic co-text, while in (5b), the referent of =aš, šab ‘night’, is more distant in the co-text yet still explicit. However, these constructions cannot be considered possessive in the conventional sense. Persian does not form possessive constructions like šab=e ruz ‘day’s night’ and ruz-e šab ‘night’s day’. Instead, in these cases, =aš serves as an associative definite marker that ensures the identifiability of its hosts by connecting them to nominal items mentioned earlier in the co-text. The clitic =aš here does not function as a possessor but establishes associative links that render the host terms identifiable.

| Ruz=i | ke | šab=aš | in | vāqe’e | voqu |

| day=indf | that | night=pc.3sg | dem | incident | happening |

| yāft-Ø. | |||||

| find.pst-3sg | |||||

| ‘A day when, that night after it, this incident happened.’ | |||||

| (Matla-e Sa’deyn va Vajma-e Bahreyn, 9th AH/15th CE) | |||||

| Šab=e | digar | mir-bāqer | be | xāne=ye | amir=i | |

| night=ez | another | Mir-Baqer | to | house=ez | emir=indf | |

| rafte, | dastbord=i | zade, | ruz =aš | xabar | be | obeyd |

| go.ppf | robbery=indf | hit.ppf | day=pc.3sg | information | to | Obeyd |

| dād-and. | ||||||

| give.pst-3pl | ||||||

| ‘The night after, Mir-Baqer went to an emir’s house, committed robbery, and the day after, they informed Obeyd.’ | ||||||

| (Hossein Kord Shabestari, 10th AH/16th CE) | ||||||

| Man | harčeqadr=am | in | mozu | ro | tozih | be-d-am, |

| pn.1sg | how.much=add | dem | topic | obj | explanation | sbjv-give-1sg |

| bāz | fardā =š | yek=i | ye | aks | dast | mi-gir-e |

| again | tomorrow=pc.3sg | one=indf | a | photo | hand | ipfv-take-3sg |

| mi-ā-d | mi-g-e | mu-hā=ye | man | daqiqan | hamin | |

| ipfv-come-3sg | ipfv-say-3sg | hair-pl=ez | pn.1sg | exactly | dem | |

| rang | mi-š-e? | |||||

| color | ipfv-become-3sg | |||||

| ‘No matter how much I explain this topic, the next day, someone will still take a photo in their hand and ask “Will my hair be dyed this color?”’ | ||||||

| (https://www.picuki.com, posted 20 Oct 2019) | ||||||

In example (5c), while =š marks a temporal concept, there is no corresponding temporal concept in the prior co-text for =š to associate with directly. Here, =š does not refer to any specific item; instead, it weakly implies an implicit temporal referent like ‘anytime,’ which can be inferred from the preceding context. Without =š, the hearer would interpret that the event mentioned after fardā ‘tomorrow’ is simply set to occur after the present moment. However, with the addition of =š, the speaker conveys that this event has constantly taken place following the first event described. Thus, =š stablishes a link between fardā and the first event, marking it for identifiability through its association with the broader context. In such cases, =š ensures identifiability by connecting the host to a larger, contextual framework, giving rise to the pc.3sg’s use as a contextual definite marker.

3.2 Contextual definiteness

In this function, the contextual concept can encompass both linguistic/textual and non-linguistic/situational contexts. Known as contextual definiteness, this usage relies on the broader context or immediate situation – rather than a specific nominal item – to make a referent identifiable. In the historical corpus of New Persian, instances of contextual definite uses of the pc.3sg are not found prior to the 19th centurgue written in that century, notable for its simple language and frequent use of possessive =aš. In (6a), the author describes the surrounding landscape as they travel and uses =aš with rāh ‘road’ to convey a specific comment about the road they are on. Here, the association does not link to any specific nominal item; instead, it draws on broader co-textual elements, such as the mentions of the ‘valley’ and ‘river’ in relation to the ‘road’. Similarly, in (6b), the noun fasl ‘season’ is marked with =aš, allowing it to be identified based on information provided in the text. By using =aš, the speaker makes clear which season is intended – the one associated with blooming meadows. In both cases, =aš functions as a contextual definite marker, facilitating identifiability through reference to the broader context.

| Kamkam | darre | tang | šode, | sarāzir | be | rudxāne |

| slowly | valley | narrow | become.ppf | descended | to | river |

| šod-im. | Rāh =aš | barāye | savāre | va | boneh | |

| become.pst-1pl | way=pc.3sg | for | rider | and | baggage | |

| eyb=i | na-dār-ad. | |||||

| problem=indf | neg-have.prs-3sg | |||||

| ‘The valley gradually narrowed as we descended toward the river. The road posed no trouble for either the riders or the baggage.’ | ||||||

| (Safarnāmeh-ye Khorāsān, 13th AH/19th CE) | ||||||

| Sahrā=ye | dast=e | čap | tamāman | seriš | ast-Ø, | |||

| meadow=ez | side=ez | left | totally | Eremurus | cop.prs-3sg | |||

| zard | o | sefid | o | xeyli | qašang. | Ammā | dah | ruz |

| yellow | and | white | and | very | beautiful | but | ten | day |

| az | fasl =aš | gozašte | ast-Ø. | Agar | dar | |||

| since | season=pc.3sg | pass.ppf | cop.prs-3sg | if | in | |||

| fasl =aš | āmade | bud-im | ke | in | gol-hā | |||

| season=pc.3sg | come.ppf | cop.pst-1pl | that | dem | flower-pl | |||

| tarotaze | bud-Ø,[…] | |||||||

| fresh | cop.pst-3sg | |||||||

| ‘The meadow on the left is covered with Eremuruses – yellow, white, and very beautiful. But the (right) season has passed by about ten days. If we had arrived during the (right) season, these flowers would have been fresh, […]’ | ||||||||

| (Safarnāmeh-ye Khorāsān, 13th AH/19th CE) | ||||||||

Beyond co-text, the non-linguistic situational context can also stablish the identity of a particular item. In colloquial Persian, there are numerous cases where =eš is used in this way, with the speaker relying on the immediate environment to mark definiteness. In example (7a), the speaker describes a lemon-shaped candle depicted in a picture. By adding =eš to limu (‘lemon’), the speaker clarifies that they mean the specific lemon in the picture. Without =eš, the statement could be interpreted more generally as a comment on lemons being aesthetically pleasing, rather than referring to the specific lemon candle in the image. Similarly, in example (7b), a couple is inspecting a house they are thinking of buying. While discussing it, one of them marks xune ‘house’ with =eš, indicating the specific house they are presently viewing. Here, =eš effectively signals contextual definiteness, grounded in the shared physical environment, underscoring how definiteness by =eš can be conveyed through situational context as well as linguistic cues.

| Āxe | be-bin-id | čeqadr | limu=š | qašang-e, |

| but | sbjv-see-3pl | how.much | lemon=pc.3sg | beautiful-cop.prs.3sg |

| čeqadr | vāqe’i-e. | |||

| how.much | real-cop.prs.3sg | |||

| ‘But look at how beautiful the lemon is. How real it looks.’ | ||||

| (https://www.instagram.com/mold.nb.candle/p/CcLYh0vtpKB/?img_index=1, posted 10 Apr 2022) | ||||

| Xune=aš | xub=e | hā, | vali | xeyli | dur=e. |

| house=pc.3sg | good=cop.prs.3sg | emp | but | very | far=cop.prs.3sg |

| ‘The house is good, but it is too far.’ | |||||

| (http://forum.pop-music.ir/threads, posted 27 Apr 2015) | |||||

It is important to note that the categories of definiteness discussed here are not rigidly separated but exist along a continuum. This continuum illustrates the gradual weakening of the link between =eš and a specific nominal referent, eventually leading to cases where =eš functions as a standalone marker of definiteness with no remaining association to a possessor. This endpoint represents a distinct category known as direct/non-associative anaphoric definiteness.

3.3 Direct anaphoric definiteness

Another use of =eš as a definite marker is to denote anaphora, where =eš functions purely as a grammatical marker of definiteness without any associative link. This anaphoric usage, similar to patterns found in Indonesian, has been observed exclusively in colloquial Persian. Examples in (8) demonstrate this direct anaphoric function: here, =eš does not stablish any association with other items, either explicitly or implicitly. In (8a), an advertisement on a website, the writer first introduces her own mobl ‘sofa’ in the title. When she refers to it again in the description, the sofa is marked with =eš to convey definiteness. A similar function is seen in (8b), where the initially introduced indefinite ketāb ‘book’ is marked with the definite =eš on its second mention.

| Mobl=e | haft.nafare=ye | xeyli | tamiz. | Mobl=eš | xeyli |

| sofa=ez | seven.person=ez | very | clean | sofa=pc.3sg | very |

| tamiz=e, | bedun=e | pāregi | va | šekastegi. | |

| clean=cop.prs.3sg | without=ez | tear | and | fractur | |

| Qeymat=e | xub=i | ham | zad-am. | ||

| price=ez | good=indf | add | hit.pst-1sg | ||

| ‘A very clean seven-person sofa. The sofa is very clean, without any tear or fracture. I have also written a very good price.’ | |||||

| (www.sheypoor.com, posted 26 Feb 2020) | |||||

| Dust | na-dār-am | ketāb-i | ro | qabl | az | xundan=eš | |

| like | neg-have.prs-1sg | book-indf | obj | before | from | reading=pc.3sg | |

| moarefi | kon-am, | vali | če | kon-am | ke | ham | |

| introduction | do.prs-1sg | but | what | do.prs-1sg | that | add | |

| ketāb =eš | xub=e | ham | sāheb=e | ketāb. | |||

| book=pc.3sg | good=cop.prs.3sg | add | owner=ez | book | |||

| ‘I don’t like to recommend a book before reading it. But both the book and the author (lit. the owner) of the book are good.’ | |||||||

| Yāru | doxtar-e | term.avali-e | savār=e | otobus=e | dānešgāh |

| dude | girl-def | semester.first-def | rider=ez | bus=ez | university |

| bud. | Dāšt-Ø | piāde | mi-šod-Ø | mi-xāst-Ø | |

| cop.pst.3sg | prog-3sg | on.foot | ipfv-become-3sg | ipfv-want-3sg |

| pul | be-d-e | be | rānande. | […] | Dānešgāh=e |

| money | sbjv-give-3sg | to | driver | university=ez | |

| olum.tahqiqāt, | puli | nist-Ø | otobus-ā=ye | ||

| science.research | un.free | neg.cop.prs-3sg | bus-pl=ez | ||

| dāxel=e | dānešgāh =eš. | ||||

| inside=ez | university=pc.3sg | ||||

| ‘A freshman girl was on the university bus. When she was getting off, she wanted to give money to the driver. […] Science-and-Research university. The buses inside the university are free.’ | |||||

| (https://twitter.com/mtinmhm/status/1841186851777847734, posted 1 Oct 2024) | |||||

In example (8c), the speaker produces two initial sentences where the specific lexical item dāneshgāh ‘university’ is used as a bare noun. When asked which university, the speaker provides the name and subsequently refers to it again using dāneshgāh, this time marked with the clitic =eš, indicating anaphoric reference. In all the examples mentioned above, the identifiability of the marked items is signaled by the use of =eš. Given such grammaticalized anaphoric uses, =eš appears to represent a more advanced stage of grammaticalization, which will be discussed in the next section. Before proceeding, note that in example (8c), the definite suffix -e is also used, marking nouns doxtar ‘girl’ and term.avali ‘freshman’ in the first line. However, in this instance, -e functions to mark specificity rather than definiteness (see von Heusinger and Sadeghpoor 2020). A comprehensive study is necessary to investigate the interaction of -e and =eš markers, and the conditions under which these two markers of definiteness are used, both from a semantic and syntactic perspective, though this is beyond the scope of the present article.

4 Some thoughts on the grammaticalization path

Analysis of historical data, when available, helps us understand how possessive markers evolve into markers of definiteness. Persian, with its rich textual tradition, offers valuable diachronic data through which to examine this semantic shift. Specifically, the grammaticalization of the possessive pc.3sg into denoting definiteness in New Persian sheds light on the process by which possessive markers acquire definite functions. Grammaticalization, as described by Kurylowicz (1965: 52), involves a diachronic process from a lexical to a grammatical item or from a less grammatical to a more grammatical one. This process entails the gradual ripping “off [of] the lexical features until only the grammatical features are left” (Lehmann 1995: 129), namely semantic bleaching or weakening, through which semantic components are lost. Hence, the item becomes “semantically less concrete” and “pragmatically less significant” (Diessel 1999: 117). Both of these features of grammaticalization in Diessel’s definition are evident in the shift of the Persian pc.3sg from a marker of possession to one of definiteness.

Pronominal clitics are never stressed. Among three types of adnominal possessive structures in Persian (examples in [1]), if a possessor is emphasized or salient, structures like (1a) or (1b) are used allowing a nominal or unbound pronominal possessor to focus possessor. When possessor is a clitic, it is highly known and given, rendering the PCs’ role as possessor “pragmatically less significant”. This factor – considering definiteness and possession as two of the types of nominal determination – facilitates the semantic shift of the pc.3sg from expressing the possessor of the construction to serving only as a determiner for the head noun. Personal pronouns are essentially definite (Roberts 2003: 330), and possessed items are definite when the possessor is definite (Barker 2000: 218). This pattern applies across many of the world’s languages, including Persian. Thus, when an item is marked by a possessive pc.3sg in Persian, it becomes definite.

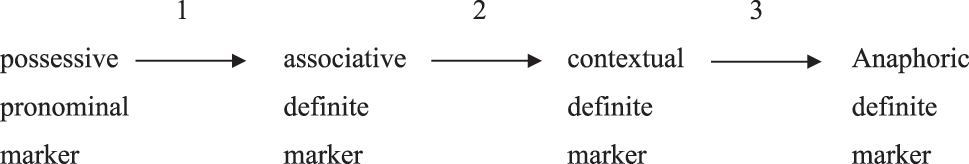

As discussed in Section 3, this definiteness feature is conferred to the head noun (possessed) first through its association with another element in the linguistic co-text that is already definite. In more advanced stages of grammaticalization (see Figure 1), this association extends beyond individual elements, linking instead to the broader linguistic or situational context, which entirely contributes to determining the definiteness of the head noun. Gerland (2014: 282) explains that possessive suffixes, when used to convey definiteness, “link the referent to a cognitive frame evoked in the discourse or already established between the participants”. She also argues that possessive markers in Uralic languages, which display definite uses, contain both possessive and definite components in their core meaning; the possessive component is suspended when the marker is used with its definite function. Accordingly, she terms these markers “relational suffixes” (Gerland 2014: 282).

Grammaticalization path of the possessive =eš into a definite marker.

The key question is, then, why and how possessive meaning is suspended or eventually lost. The grammaticalization of possessive markers into non-possessive roles, such as definiteness marking, unfolds two main parts: the loss of possessive meaning and the loss of person and number features.[5] Both parts involve a phase of becoming “semantically less concrete” (Diessel 1999: 117), as will be described below. Possessive markers are inherently compositional; they refer to another item (possessor), agreeing with it in person and number, and they make this item possessor of the construction by stablishing a possessive relationship with the head noun. As Barker (1995) explains, possessive constructions consist not only of possessor and possessed but also of a possessive relation between them. The semantics of this relation is shaped by context or by the lexical meanings of the nominal items in the construction (Lander 2008: 581).

In New Persian, Etebari (2020) and Etebari et al. (2023) have identified 21 distinct meaning relations within possessive constructions involving a PC as the possessor, noting that these relations are not similarly distributed historically but have shifted over time. In the early centuries of New Persian, kinship and body-part relations predominated, while other relations developed gradually. One outcome of this study is the finding that abstract relations developed later than concrete ones. For example, early whole-part relations encoded by possessive PCs in Persian included only concrete body parts or parts of physical items, but later encompassed more abstract concepts, such as membership in a group. This shift eventually contributed to the grammaticalization of the pc.3sg, along a different pathway, into markers of partitivity and contrast (see Etebari et al. 2020).

This process of abstraction in meaning relations is accompanied by a shift in the referentiality of the possessive pc.3sg itself. As mentioned above, over time the pc.3sg came to refer not only to specific nominal items (in [4], [5a], and [5b]) but also to broader contexts within the co-text (in [5c] and [6]) or the situational setting (in [7]). After this stage of grammaticalization, the possessor was no longer textually accessible, leading to a gradual loss of the possessive meaning as the association with a specific possessor diminished. This stage, termed “desemanticization of possessive meaning”, is noted in a similar grammaticalization pathway for possessive suffixes in Udmurt (Serdobolskaya et al. 2019).

Following this stage, possessive markers eventually lose their person and number features, allowing them to be used in constructions where the implied possessor differs in person and number. This occurs in the final stage of the grammaticalization, which includes anaphoric uses of the pc.3sg (in [8]). For example, in (8a), one might expect a 1SG PC to agree with the owner of the sofa, yet a pc.3sg appears instead, indicating a generalization of the grammatical function (Serdobolskaya et al. 2019). This feature, in which the marker no longer aligns with the possessor’s person and number, led Kiss and Orsolya (2018) and Mikhailov (2024) to treat the definiteness functions of possessive markers in Udmurt and Kazym Khanty as distinct from the proper possessive function, regarding them instead as “a synchronically independent marker” (Mikhailov 2024: 41).

Based on this discussion, Figure 1 outlines a proposed grammaticalization pathway for the development of the pc.3sg into a definite marker.

However, such shifts from possessives into non-possessive functions do not always fulfil the prerequisites of grammaticalization. The most debated criterion is the obligatoriness of the new uses. Obligatoriness is considered the key indicator of the status of grammaticalization, as it signifies that a category has become an obligatory element in the grammar of a language, when the speakers have no option to leave the category unspecified (Lehmann 1995: 124). When a category reaches this stage, it is recognized as fully grammaticalized. In case of non-possessive uses of possessive markers, the usages are generally found to be non-obligatory (Fraurud 2001: 254), or obligatory only in specific contexts (Nikolaeva 2003; Simonenko 2014). The main conclusion, therefore, is that these non-possessive markers do not represent fully grammaticalized markers, particularly because they can be freely omitted and lack distributional freedom, or systematic usage that Johanson (1991) associates with grammaticalized elements.

The concept of obligatoriness should not be viewed a leap from non-obligatory status but rather as a gradual process, much like grammaticalization itself (Lehmann 1995). As Hopper and Traugott (2003: 32) explain, grammaticalization – as well as associated criteria like semantic bleaching and obligatoriness – is historical and ongoing, meaning that “we will often not see a completed instance of grammaticalization”. With obligatoriness as a criterion, it is possible to observe varying degrees of grammaticalization or to investigate “how far the grammaticalization process has developed” (Fraurud 2001: 254).

In Persian, the non-possessive pc.3sg is obligatory in associative and contextual definite uses but appears non-obligatory when used anaphorically. In associative and contextual definite uses, omitting the pc.3sg typically shifts the meaning to something more generic. As discussed in Section 3, the presence of the PC is crucial in identifying which nominal item the speaker intends. Conversely, in constructions like those in examples (8), where the pc.3sg is used with anaphoric definite function, the overall meaning remains intact whether or not the PC is included. The primary difference is that without the PC, the expression takes on a more formal tone, typical of written formal Persian but less natural in informal colloquial Persian. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between written and spoken uses, as Rubin (2010) has done for Indonesian. Although the pc.3sg may be freely omitted when used anaphorically, it would rarely occur that way in natural speech, potentially indicating a transitional phase in its grammaticalization as a definite marker. A similar phenomenon is seen in the Semitic language family. For instance, in Chaha, the use of the possessive suffix with definite function, compared to colloquial mode, is more syntactically restricted in formal contexts and is not employed anaphorically, while in Amharic, another Ethiopic language, the third-person possessive suffix does not exhibit this restriction and is widely used as a definite marker even in formal language (Rubin 2010).

To address why these developments have occurred in certain languages, one key factor to consider is frequency. Textual frequency is often viewed as crucial to grammaticalization processes (Hopper and Traugott 2003: 126–127). Following this idea, Fraurud (2001) employs Cyr’s (1993) cross-linguistic quantification criteria, where demonstratives in Montagnais, an Algonquian language, are classified as definite articles due to their high frequency, comparable to that of definite articles derived from demonstratives in other languages. Fraurud (2001) argues that the high discourse frequency of possessive markers – compared with parallel possessive categories in other languages – is evidence for an ongoing grammaticalization process towards definite marking. Fraurud (2001) compares the ratio of noun phrases with possessive markers to all noun phrases in data samples from Udmurt, written Turkish, and Yucatec Maya, contrasting them with English and Swedish. The results show a significantly higher ratio in the first group (20 %–40 %) compared to Swedish and English (less than 2 %). Although Persian corpora are limited, a smaller corpus of colloquial Persian (Haig and Rasekh-Mahand 2022), containing approximately 18,000 words, indicates a ratio of 13 %. This frequency data supports the view that Persian possessive markers are similarly undergoing grammaticalization into definite markers.

However, an important consideration in this comparison is that comparing the degree of grammaticalization between two categories “presupposes that they are functionally similar” (Lehmann 1995: 111) or, as Cyr (1993: 197) puts it, assumes a similar “semantico-functional range of application”. Although the possessive constructions in both groups are labelled as possessives, their functional ranges differ across these languages. Furthermore, regarding frequency, Hawkins’ (1978) classification of definite uses in English sheds light on an additional distinction. English typically uses the definite article the to express a range of meaning relations, while in languages like Udmurt and Turkish, many of these relations – particularly associative anaphoric relations – are instead expressed by a possessive marker. Hawkins (1978) observes that the associative anaphoric use is the most frequent definite use of the in English, yet this relation is conveyed by a possessive marker in group one languages, such as Persian. Consequently, a higher frequency of possessive markers in these languages does not, on its own, indicate grammaticalization toward definiteness. Rather, it reflects the differing linguistic strategies these languages employ for definite marking.

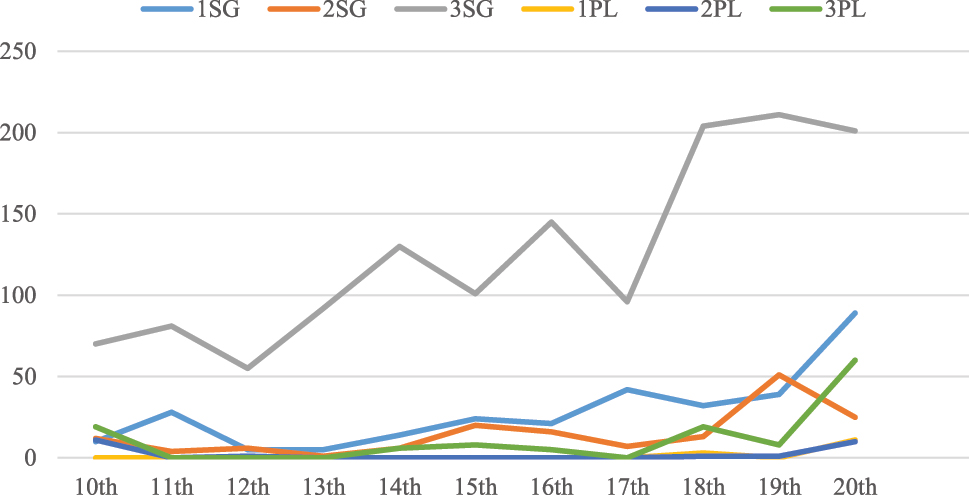

I would like to emphasize the crucial role of frequency in the grammaticalization of possessives into definites by illustrating the diachronic frequency of the pc.3sg in Persian, which provides a deeper insight. Hopper and Traugott (2003: 127–129) suggest that an “increased frequency of a construction over time” serves as “prima facie evidence of grammaticalization”, where “repetition of forms may lead to their ‘liberation,’ or ‘emancipation’ (Haiman 1994), from their earlier discourse contexts”. Examining the frequency of the Persian pc.3sg diachronically yields compelling results. Figure 2 illustrates the frequencies of pronominal clitics across several centuries of New Persian (10th–20th). Of nearly 2,500 adnominal constructions containing possessive pronominal clitics in the Etebari (2020) corpus, 70 % feature the pc.3sg. As shown in Figure 2, all PCs – and especially the pc.3sg – exhibit a notable increase in usage beginning in the 17th century.

Diachronic frequency of possessive pronominal clitics in New Persian (Etebari 2020).

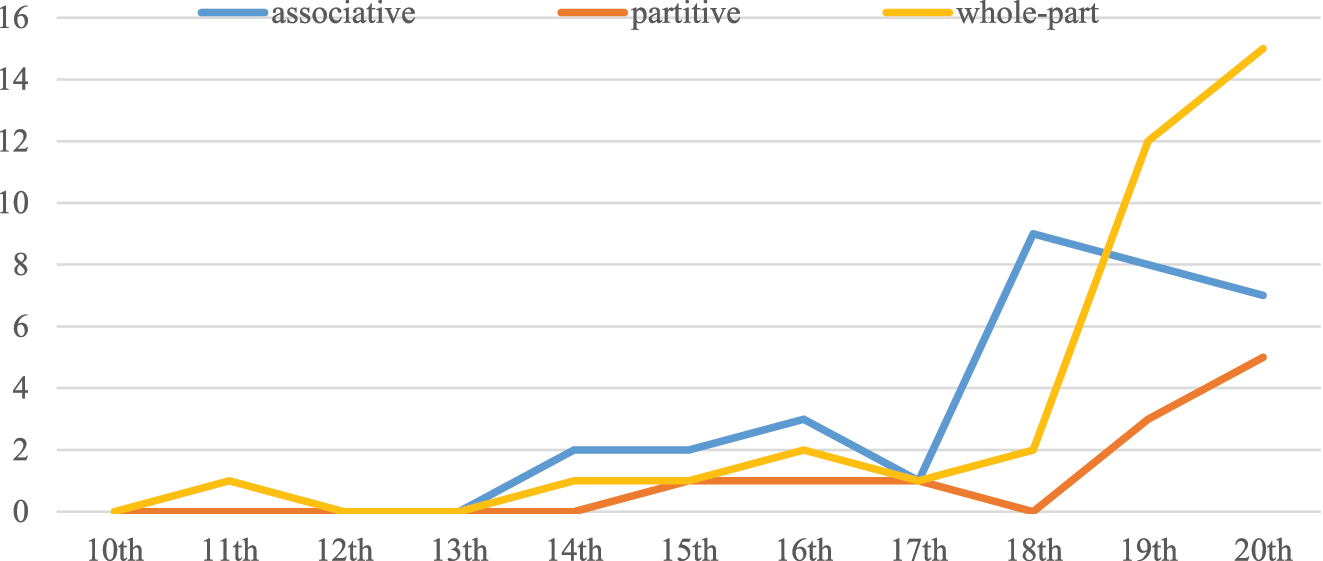

Not only have the frequencies of pronominal clitics increased significantly over the last three centuries, but both the frequency and range of abstract meaning relations have also broadened considerably. Figure 3 depicts three specific meaning relations, – whole-part (excluding body-part relations), partitive, and associative – which have shown dramatic growth in frequency during this period. The frequency increase in whole-part and partitive relations underscores the role of frequency in driving the development of the pc.3sg into contrastive-partitive marker (Etebari et al. 2020). Additionally, we observe a marked rise in associative meaning relation, which involve any context-specific relationship between possessor and possessed that falls outside typical possessive meaning relations, such as ownership, kinship, whole-part, attributive, or origin relations. The substantial increase in associative relation since the 17th century appears to have facilitated the development of the pc.3sg’s contextual definiteness function, which is not evidenced in the corpus prior to the 19th century.

Diachronic frequencies of three meaning relations of possession in New Persian (Etebari 2020).

Several scenarios can be proposed regarding the future development and grammatical status of these emerging definite markers. Fraurud (2001: 255) suggests that one possible development is for possessive markers to lose their possessive meanings, allowing other constructions – such as those with free pronouns as possessors – to become the default way of expressing possession. However, this scenario is less likely in Persian, as the possessive marker in this language is not merely a possessive form but a pronominal clitic that also functions as an object argument. A more probable outcome for Persian is a scenario similar to that of Amharic, where both possessive and definite clitics coexist as homonyms (Rubin 2010). Additionally, we may see a development akin to the situation in Chaha or Indonesian, where definite uses of the pc.3sg diverge between formal and colloquial registers (Rubin 2010). In this case, the grammaticalized, obligatory definite marker could develop primarily in colloquial Persian while remaining optional in formal Persian, reflecting distinct pathways in colloquial versus formal language.

5 Conclusions

This article has explored the development of the definiteness function in the third person singular pronominal clitic (pc.3sg) in New Persian, particularly in its role as a possessor in various adnominal constructions. It has been demonstrated that the pc.3sg extends beyond its original possessive function and is used to denote identifiability of the head noun for the hearer. Through the examination of authentic examples from colloquial Persian, as well as historical data from a corpus of New Persian (Etebari 2020), the study reveals that the pc.3sg is employed for three types of definiteness, categorized by Hawkins (1978). These include associative anaphoric and immediate situational uses, as well as non-associative anaphoric definiteness, which represent a more advanced stage in the grammaticalization of possessive markers. This study further shows that different definiteness uses exhibit a shift over time among various centuries of New Persian, helping us to establish a tentative grammaticalization path.

The findings indicate that the associative definite function of the pc.3sg emerges from its possessive use, wherein identifiability is established by making associations with other nominal items. This marks the first stage in the grammaticalization path of the pc.3sg. Notably, the frequency of the possessive pc.3sg has increased since the 17th century, leading to the development of weaker associations that link the head noun to the broader linguistic co-text or to the situational context. This shift marks a significant change in usage, as such contextual definiteness was largely absent in earlier periods, particularly before the 19th century.

As the pc.3sg is grammaticalized from denoting possession to serving as a determiner of definiteness, it undergoes a process of desemanticization, gradually losing its possessive meaning. This shift is evidenced by derivation and increased frequencies of abstract meaning relations in possessive constructions of New Persian with possessive clitic over time. This builds the second stage of the grammaticalization path. Eventually, this process culminates in the loss of the associative component, resulting in the pc.3sg functioning as an anaphoric definite marker akin to an article. This use of the pc.3sg is primarily observed in colloquial Persian. In this third stage of grammaticalization, the pc.3sg loses its person and number features and becomes grammatically generalized. The study further highlights that the definite pc.3sg clitic exhibits obligatory use only in associative and situational contexts uses, while remaining optional in anaphoric uses. This variation indicates the transitional phase of the clitic’s grammaticalization from possessive to definite marker.

List of abbreviations

- 1

-

first person

- 2

-

second person

- 3

-

third person

- add

-

additive

- cop

-

copula

- def

-

definite

- dem

-

demonstrative

- emp

-

emphasizer

- ez

-

Ezafe particle

- indef

-

indefinite

- inf

-

infinitive

- ipfv

-

imperfective

- neg

-

negative

- obj

-

object

- pc

-

pronominal clitic

- pl

-

plural

- pn

-

pronoun

- ppf

-

perfect participle

- prog

-

progressive

- prs

-

present

- pst

-

past

- sbjv

-

subjunctive

- sg

-

singular

Texts included in the corpus (Etebari 2020).

| Date | Title | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 4AH/10CE |

Tārikh-e Bal’ami

Tafsir-e Tabari Tafsir-e Qurān-e Pāk |

Abu Ali Mohammad Bal’ami Mansur Ebn-e Nuh Samani Anonymous |

| 5AH/11CE |

Tārikh-e Beyhaqi

Siāsatnāmeh Safarnāmeh |

Abu al-Fazl Beyhaqi Nezam al-Molk Toosi Naser Khosrow Qobadiani |

| 6AH/12CE |

Dārābnāmeh

Samak-e Ayār Rownaq al-majāles |

Abu Taher Ebn-e Hasan Tarsoosi Faramarz Ebn-e khodadad Ebn-e Abdollah Mohammad Ebn-e Ahmad Samarqandi |

| 7AH/13CE |

Tabāqt-e Nāseri

Bakhtiārnāmeh Nezām al-Tavārikh |

Seraj al-Din Jowzjani Shams al-Din Moḥammad Daqayeqi Marvazi Abdollah ebn-e Omar Beyzavi |

| 8AH/14CE |

Koliyāt

Tootināmeh Tārikh-e Gozideh |

Obeyd Zakani Zia al-Din Nakhshabi Hamdollah Mostowfi |

| 9AH/15CE |

Bahārestān

Dārābnameh Matla-e Sa’deyn va Majma-e Bahreyn |

Abd al-Rahman Jami Mohammad Biqami Kamal al-Din Abd al-Razaq Samarqandi |

| 10AH/16CE |

Hossein Kord Shabestari

Badāye’ al-Vaqāye’ Tazkare-ye Shāh Tahmasb |

Anonymous Zeyn ad-Din Mahmood Vasefi Shah Tahmasb Safavi |

| 11AH/17CE |

Ālamāray Shāh Esmāeil

Jāme’ al-Tamsil Jahāngirnāmeh |

Anonymous Mohammad Hablerudi Nur al-Din Mohammad Jahangir Gurkani |

| 12AH/18CE |

Monsha’āt

Majmal al-Tavārikh Rostam al-Tavārikh |

Abu al-Qasem Qaem Maqam Farahani Abu al-Hasan Golestaneh Mohammad Hashem Asef |

| 13AH/19CE |

Safarnāme-ye Khorāsān

Ketāb-e Ahmad Amir Arsalān-e Nāmdār |

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar Mirza Abdolrahim Talbof Mohammad Ali Naqib al-Mamalek |

| 14AH/20CE |

Shalvārha-ye Vasledār

Siāhatnāme-ye Ebrāhim Beyg Charand-o Parand |

Rasoul Parvizi Haji Zeyn al-Abedin Maraqei Ali Akbar Dehkhoda |

References

Abondolo, Daniel & Riitta-Liisa Valijärvi (eds.). 2023. The Uralic languages. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2012. Possession and ownership: A cross-linguistic perspective. In Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald & Robert M. W. Dixon (eds.), Possession and ownership, 1–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Appleyard, David. 2005. Definite markers in modern Ethiopian Semitic languages. In Geoffrey Khan (ed.), Semitic studies in honor of Edward Ullendorff, 51–61. Leiden: Brill.Suche in Google Scholar

Apresyan, Valentina & Maria Polinsky. 1996. The article system in spoken Eastern Armenian. In Howard I. Aronson (ed.), NSL. 8: Linguistic studies in the non-Slavic languages of the Common Wealth of Independent States and the Baltic Republics, 19–32. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.Suche in Google Scholar

Armbruster, Charles H. 1908. Initia Amharica: An introduction to spoken Amharic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Barker, Chris. 1995. Possessive descriptions. Stanford: CSLI Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Barker, Chris. 2000. Definite possessives and discourse novelty. Theoretical Linguistics 26. 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2000.26.3.211.Suche in Google Scholar

Becker, Laura. 2021. Articles in world’s languages. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Benzing, Johannes. 1993. Das possessivsuffix der dritten Person. In Claus Schönig (ed.), Bolgarisch-tschuwaschische studien (Turcologica 12), 251–267. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Collinder, Björn. 1957. Survey of the Uralic languages. Stockholm: Almquist och Wiksell.Suche in Google Scholar

Collinder, Björn. 1960. Comparative grammar of the Uralic languages. Stockholm: Almqvistoch Wiksell.Suche in Google Scholar

Cyr, Danielle. 1993. Cross-linguistic quantification: Definite articles vs. demonstratives. Language Sciences 15. 195–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/0388-0001(93)90013-i.Suche in Google Scholar

Dabir-Moghaddam, Mohammad. 1990. Pirâmun-e râ dar zabân-e Farsi [About -râ in the Persian language]. Iranian Journal of Linguistics 7. 2–60.Suche in Google Scholar

De Mulder, Walter & Anna Carlier. 2011. Definite articles. In Bernd Heine & Heiko Narrog (eds.), Oxford handbook of grammaticalization, 522–535. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives: Form, function, and grammaticalization. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. 2013. Definite articles. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), World atlas of language structures online. Munich: Max Planck Digital Library.Suche in Google Scholar

Englebretson, Robert. 2003. Searching for structure: The problem of complementation in colloquial Indonesian conversation. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Etebari, Zahra. 2020. Diachronic development of pronominal clitic system in new Persian: A functional-typological approach. Mashhad: Ferdowsi University.Suche in Google Scholar

Etebari, Zahra, Alizadeh Ali & Mehrdad Naghzguy-Kohan. 2023. Naqsheh-ye ma’naei-e malek-e vajebasti dar sakht-e ezafi-e farsi-e no [A semantic map of possessive pronominal clitics in pertensive constructions of New Persian]. Language Related Research 13(6). 289–323.Suche in Google Scholar

Etebari, Zahra, Alizadeh Ali, Mehrdad Naghzguy-Kohan & Maria Koptjevskaja Tamm. 2020. Development of contrastive-partitive in colloquial Persian: A grammaticalization from possessive =eš. STUF - Language Typology and Universals 73(4). 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1515/stuf-2020-1019.Suche in Google Scholar

Ewing, Michael C. 1995. Two pathways to identifiability in Cirebon Javanese. BLS (Special session on discourse in Southeast Asian languages of Berkeley Linguistics Society) 21. 72–82. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v21i2.3389.Suche in Google Scholar

Fraurud, Kari. 2001. Possessives with extensive use: A source of definite articles? In Irène Baron, Michael Herslund & Finn Sørensen (eds.), Dimensions of possession, 243–267. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Gerland, Doris. 2014. Definitely not possessed? Possessive suffixes with definiteness marking function. In Thomas Gamerschlag, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald & Wiebke Petersen (eds.), Frames and concept types: Applications in language and philosophy (Studies in linguistics and philosophy 94), 269–292. Cham & Heidelberg: Springer.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghatreh, Fariba. 2007. Moshakhaseh-ha-ye tasrifi dar zaban-e farsi-e emrooz [Inflection in contemporary Persian]. Dastoor 3(3). 52–81.Suche in Google Scholar

Grönbech, Kristina. 1936. Der Turkische sprachbau. Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard.Suche in Google Scholar

Haig, Geoffrey. 2018. Optional definiteness in Central Kurdish and Balochi: Conceptual and empirical issues. Paper presented at the third workshop on information structure in spoken language corpora (ISSlaC3). Münster: University of Münster, 7–8 December 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

Haig, Geoffrey & Mohammad Rasekh-Mahand. 2022. HamBam: The Hamedan-Bamberg corpus of contemporary spoken Persian. Bamberg: University of Bamberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Haiman, John. 1994. Ritualization and the development of language. In William Pagliuca (ed.), Perspectives on grammaticalization, 3–28. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Havas, Ferenc, Erika Asztalos, Nikolett F. Gulyás, Laura Horváth & Bogáta Timár. 2023. Typological database of the Volga area finno-Ugric languages (VolgaTyp). Budapest: ELTE Finnugor Tanszék.Suche in Google Scholar

Hawkins, John A. 1978. Definiteness and indefiniteness: A study in reference and grammaticality prediction. London: Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

Heusinger, Klaus von & Roya Sadeghpoor. 2020. The specificity marker -e with indefinite noun phrases in modern colloquial Persian. In Kata Balogh, Anja Latrouite & Robert D. Van ValinJr. (eds.), Nominal anchoring, 115–147. Berlin: Language Science Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. 1996. Demonstratives in narrative discourse: Taxonomy of universal uses. In Barbara A. Fox (ed.), Studies in anaphora, 205–254. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. 2001. Articles. In Martin Haspelmath, Ekkehard König, Wulf Oesterreicher & Wolfgang Raible (eds.), Language typology and language universals: An international handbook, 831–841. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Hodgson, Katherine. 2022. Grammaticalization of the definite article in Armenian. Armeniaca: International Journal of Armenian Studies 1. 125–149.Suche in Google Scholar

Hopper, Paul J. & Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Huehnegard, John & Na’ama Pat-El. 2012. Third-person possessive suffixes as definite articles in Semitic. Journal of Historical Linguistics 2(1). 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhl.2.1.04hue.Suche in Google Scholar

Jahanpanah, Simindokht. 2001. Zamir-e motasel-e š va dāštan: Do gerayesh-e taze dar zaban-e goftari-e emruz-e Tehran [The bound pronoun =eš and dāštan, two new tendencies in colloquial Persian of Tehran]. Zabanshenasi 31. 19–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Janda, Gwen E. 2015. Northern Mansi possessive suffixes in non-possessive function. Eesti ja Soome-Ugri keeleteaduse ajakiri 6(2). 243–258. https://doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2015.6.2.10.Suche in Google Scholar

Janhunen, Juha A. 2003. Khamnigan Mongol. In Juha A. Janhunen (ed.), The Mongolic languages, 83–101. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Jesperson, Otto. 1924. The philosophy of grammar. London: Allen and Unwin.Suche in Google Scholar

Johanson, Lars. 1991. Bestimmtheit und mitteilung perspektive im türkischen satz. In György Hazai (ed.), Linguistische Beiträge zur Gesamtturkologie, 225–250. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.Suche in Google Scholar

Johanson, Lars & Éva A. Csató (eds.). 2022. The Turkic languages. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kapeliuk, Olga. 1994. Syntax of the noun in Amharic. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Karimi, Simin. 2003. Word order and scrambling. New York: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Kiss, Katalin É. 2018. Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix. In Huba Bartos, Marcel D. Dikken, Zoltan Banreti & Tamas Varadi (eds.), Boundaries crossed, at the interfaces of morphosyntax, phonology, pragmatics and semantics, 87–105. Cham & Heidelberg: Springer.Suche in Google Scholar

Kiss, Katalin É. & Orsolya Tanczos. 2018. From possessor agreement to object marking in the evolution of the Udmurt -jez suffix: A grammaticalization approach to morpheme syncretism. Language 94. 733–757. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.0.0233.Suche in Google Scholar

Kononov, Andrej N. 1956. Grammatika sovremennogo Tureckogo literaturnogo jazyka [Grammar of contemporary literary Turkish]. Moskva & Leningrad: Nauka.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuryłowicz, Jerzy. 1965. The evolution of grammatical categories. Diogenes 51. 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/039219216501305105.Suche in Google Scholar

Lander, Yuri. 2008. Varieties of genitive. In Andrej Malchukov & Andrew Spenser (eds.), Handbook of case, 581–592. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Landsberger, Benno. 1948. Sam’al: Studien zur entdeckung der ruinenstaette Karatepe. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.Suche in Google Scholar

Lazard, Gilbert. 1957. Grammaire du persan contemporain. Paris: Klincksieck.Suche in Google Scholar

Lehmann, Christian. 1995. Thoughts on grammaticalization. Munchen & Newcastle: Lincom Europa.Suche in Google Scholar

Lehmann, Christian. 1998. Possession in Yucatec Maya: Structures, functions, typology. Munchen & Newcastle: Lincom Europa.Suche in Google Scholar

Leslau, Wolf. 1995. Reference grammar of Amharic. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Löbner, Sebastian. 1985. Definites. Journal of Semantics 4(4). 279–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/4.4.279.Suche in Google Scholar

Lyons, Christopher. 1999. Definiteness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Menges, Karl H. 1968. The Turkic languages and peoples: An introduction to Turkic studies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Mikhailov, Stiopa. 2024. Diagnosing Northern Khanty unpossessives, or how to tell a synchronically independent marker from its diachronic source. Ural-Altaic Studies 4(55). 31–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Nadimi, Mahmood & Tahmineh Ataei. 2018. The definite -e in classical Persian texts. Dastoor 14. 173–182.Suche in Google Scholar

Nikolaeva, Irina. 2003. Possessive affixes in the pragmatic structuring of the utterance: Evidence from Uralic. In Pirkko M. Suihkonen & Bernard Comrie (eds.), International symposium on deictic systems and quantification in languages spoken in Europe and North and Central Asia, 130–145. Izhevsk: Udmurt State University/Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.Suche in Google Scholar

Nikolaeva, Irina & Maria Tolskaya. 2011. A grammar of Udihe. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Nilsson, Birgit. 1985. Case marking semantics in Turkish. Stockholm: Stockholm University.Suche in Google Scholar

Nourzaei, Maryam. 2023. Diachronic development of the k-suffixes: Evidence from classical New Persian, contemporary written Persian and contemporary spoken Persian. Iranian Studies 56(1). 115–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/irn.2021.27.Suche in Google Scholar

Pakendorf, Birgitte. 2007. Contact in the prehistory of the Sakha (Yakuts): Linguistic and genetic perspectives. Leiden: Leiden University.Suche in Google Scholar

Rasekh-Mahand, Mohammad. 2009. Ma’refe va nakare dar zaban-e farsi [Definiteness and indefiniteness in Persian]. Dastoor 5. 81–103.Suche in Google Scholar

Roberts, Craige. 2003. Uniqueness in definite noun phrases. Linguistics and Philosophy 26. 287–350. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024157132393.Suche in Google Scholar

Rubin, Aron. D. 2005. Studies in Semitic grammaticalization. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.Suche in Google Scholar

Rubin, Aron. D. 2010. The development of the Amharic definite article and an Indonesian parallel. Journal of Semitic Studies 55(1). 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgq050.Suche in Google Scholar

Schlachter, Wolfgang. 1960. Studien zum possessivsuffix der Syrjänischen. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Schroeder, Christoph. 1999. The Turkish nominal phrase in spoken discourse. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Serdobolskaya, Natalia, Maria Usacheva & Timofey Arkhangelskiy. 2019. Grammaticalization of possessive markers in the Beserman dialect of Udmurt. In Lars Johanson, Lidia Federica Mazzitelli & Irina Nevskaya (eds.), Possession in languages of Europe and North and Central Asia, 291–311. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Serebrennikov, Boris A. 1963. Istori_eskaja morfologija permskix jazykov [The historical morphology of Permic languages]. Moscow: Akademija Nauk.Suche in Google Scholar

Shaqaqi, Vida. 2014. Vaje-bast-e jaygah-e dovom dar farsi [Second position clitic in Persian]. In Mohammad Rasekh-Mahand (ed.), Barrasi-ye vajehbast dar zabanha-ye irani [Study of clitics in Iranian languages], 13–35. Tehran: Neviseh.Suche in Google Scholar

Simonenko, Alexandra. 2014. Microvariation in Finno-Ugric possessive markers. In Hsin-Lun Huang, Ethan Poole & Amanda Rysling (eds.), Proceedings of the forty-third annual meeting of the north east linguistic society (NELS 43), vol. 2, 127–140. Amherst & Massachusetts: GLSA.Suche in Google Scholar

Sneddon, James N. 1996. Indonesian: A comprehensive grammar. London & New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Stachowski, Marek. 2010. On the article-like use of the Px2Sg in Dolgan, Nganasan and some other languages in an areal Siberian context. Finnisch-Ugrische Mitteilungen 32(33). 587–593.Suche in Google Scholar

Tauli, Valter. 1966. Structural tendencies in Uralic languages. The Hague: Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Zolyan, Suren. 2024. On the so-called “definite article” in Eastern Armenian: Grammatical constraints and pragma-semantics functions. Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology XXVIII. 641–672.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Papers

- Go to church or die in prison: PPs with bare institutional nouns in the history of English

- Possessives as source of definite articles? Diachronic evidence from Persian

- Lenition of voiced stops in Kurdish

- Third-person singular present tense inflectional variation in Medieval and Early Modern English scientific texts: a corpus-based study

- The emergence of stand-alone insubordinate conditional clauses in Hungarian

- Tracing the origins and grammaticalization path of Irish English habitual do V: an analysis of the 1641 Depositions

- The diachronic development of the inchoative construction in Spanish: a case of constructionalization

- Negative correlative coordination in Indo-European: emergence, evolution and variability

- Book Reviews

- Xinyue Yao: The present perfect and the preterite in Late Modern and Contemporary English. A corpus-based study of grammatical change

- John D. Bengtson: Basque and its closest relatives. A new paradigm

- Stephanie Roussou and Philomen Probert: Ancient and medieval thought on Greek enclitics

- Sophia J. Oppermann: Coordination structures in Old and Middle High German

- Program Review

- IE10.com. Reconstructing Latin inscriptions with Aeneas

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Papers

- Go to church or die in prison: PPs with bare institutional nouns in the history of English

- Possessives as source of definite articles? Diachronic evidence from Persian

- Lenition of voiced stops in Kurdish

- Third-person singular present tense inflectional variation in Medieval and Early Modern English scientific texts: a corpus-based study

- The emergence of stand-alone insubordinate conditional clauses in Hungarian

- Tracing the origins and grammaticalization path of Irish English habitual do V: an analysis of the 1641 Depositions

- The diachronic development of the inchoative construction in Spanish: a case of constructionalization

- Negative correlative coordination in Indo-European: emergence, evolution and variability

- Book Reviews

- Xinyue Yao: The present perfect and the preterite in Late Modern and Contemporary English. A corpus-based study of grammatical change

- John D. Bengtson: Basque and its closest relatives. A new paradigm

- Stephanie Roussou and Philomen Probert: Ancient and medieval thought on Greek enclitics

- Sophia J. Oppermann: Coordination structures in Old and Middle High German

- Program Review

- IE10.com. Reconstructing Latin inscriptions with Aeneas