Abstract

The aim of this paper is to explore the linguistic expression of extreme large quantities by focusing on some Italian adverbial constructions characterised by the [a + X NOUN<plural>] pattern. These constructions can be considered as quantity intensifiers used to express a constructional meaning related to abundance that can be summarised as ‘a lot, in large quantities’. After presenting the syntactic and semantic properties shared by these expressions, a set of data extracted from the web will be analysed with a corpus-driven approach. The goal of the work is twofold: on one side, a comparison between the combinatorial contexts of the selected expressions will be presented and discussed, in order to highlight similarities and differences between them; on the other, a qualitative analysis of a specific multiword, a fiumi, will be proposed.

1 Introduction

The notions of quantification and intensification[1] traditionally belong to separated domains. The former can be defined as the property of attributing a quantity to a measurable or quantifiable phenomenon (Hadermann et al. 2010; reprised in: Adler and Asnès 2013: 10); the latter can be defined as a set of operations used by speakers to express a form of graduation thanks to which it is possible to measure or modify “the degree of a given entity, property or event” from a lower to a higher degree (Bolinger 1972; Micheli forthcoming).[2] Despite these differences, Gaatone (2008) points out the possibility to group quantifiers and intensifiers under the same category, because they both share a common property, i.e., scalarity, which may be defined as the capability of referring to a progressive scale of values (Adler and Asnès 2013: 10). From this perspective, intensification is realized through a scalar property expression called intensifier, which is used to modulate the degree of gradable notions, either on a qualitative or on quantitative level (Ghesquière 2017: 34), according to the nature of the objects considered and to the type of semantic relation encoded. Following Piunno (2021: 134) “in the case of quality intensifiers, the intensification is based on a relation of similarity involving semantic prototipicality (Rapatel 2015) and categorisation of the intensified item by prototypes (Anscombre and Tamba 2013)”, as in perfetto imbecille (‘total idiot’, lit. ‘perfect idiot’), where perfetto highlights how the subject is the best representative of a prototypical imbecille category. On the other level, “quantity intensifiers are able to make the intensified item gradual and to (metaphorically) refer to the highest degree of a certain quantity” (Piunno 2021: 135), as in tutto matto (‘completely mad’, lit. ‘all mad’).

Within the linguistic strategies used in Italian to convey an intensified meaning,[3] this paper will focus on lexical intensifiers, e.g. linguistic units able to convey an intensifying meaning to the lexemes with which they occur (Piunno 2021: 134). This set is mainly composed of adjectives and adverbial items (Bolinger 1972), which share the ability to modify the degree of gradable properties conveyed by descriptive elements (Ghesquière 2017: 33; see also Cacchiani 2011: 763). More specifically, this work aims to provide an overview of a selected number of adverbial multiword expressions having the shape of a prepositional phrase and conveying a constructional meaning related to abundance, as shown in the examples below (1a–c):

| il | buon | vino | e | il | rum | della | Martinica |

| the | good | wine | and | the | rum | of_the | Martinique |

| scorrevano | a | fiumi | |||||

| flow-pst.3pl | to | rivers | |||||

| ‘Good wine and rum from Martinique were flowing in large quantities.’ | |||||||

| vendere | milioni | di | copie | di | libri |

| sell-inf | millions | of | copies | of | books |

| e | fare | i | soldi | a | palate |

| and | do-inf.pres | the | money | to | spadefuls |

| ‘Sell millions of copies of books and make a lot of money.’ | |||||

| Sarà | che | mangio | cioccolata | a | vagonate |

| be-fut.3sg | that | eat-pres.1sg | chocolate | to | wagonload-pl |

| ‘Maybe it is because I eat tons of chocolate.’ | |||||

To summarise the content of this work, in Section 2 the structures considered, e.g. partially filled constructions, will be presented from a theoretical point of view, describing both their syntactic and semantic properties. In Section 3, a quantitative study based on the comparison between the combinatorial contexts of the selected constructions will be discussed. Section 4 will be devoted to the presentation of a case study based on a fiumi. The analysis of frequency data (Section 4.1) will be followed by a syntactic and a semantic analysis (Section 4.2) and a more detailed description of the elements co-occurring with the multiword expression. Finally, in Section 5 a few provisional conclusions will be formulated.

2 Partially filled constructions: syntactic and semantic properties

This work focuses on some Italian multiword expressions taking the form of prepositional phrases fulfilling an adverbial function; all these lexemes are composed of the preposition a (lit. to) followed by a plural noun, whose meaning can be summarised as ‘a lot’, ‘in large quantities’, as shown by the examples extracted from the itTenTen20[4] corpus in Table 1.

Adverbial multiword expressions meaning ‘a lot’ extracted from the itTenTen20 corpus.

| Adverbial multiword expressions meaning ‘a lot’ | Examples |

|---|---|

| a badilate | mangio lenticchie a badilate |

| (lit. ‘to shovelfuls’) | ‘I eat a large quantity of lentils’ |

| a carrellate | si raccolgono a carrellate le noci moscate |

| (lit. ‘to cartloads’) | ‘nutmegs are gathered in large quantity’ |

| a carrettate | Avrei guadagnato oro a carrettate |

| (lit. ‘to cartloads’) | ‘I would have earned a lot of gold’ |

| a fiumi | Il sangue scorreva a fiumi |

| (lit. ‘to rivers’) | ‘The blood was flowing in large quantity’ |

| a mucchi | Per le strade ci sono cadaveri, a mucchi |

| (lit. ‘to piles’) | ‘There are large quantities of corpses lying on the streets’ |

| a ondate | I guai arrivano sempre a ondate |

| (lit. ‘to waves’) | ‘Troubles always come in large quantities’ |

| a pacchi | proprio io che dovrei saperne a pacchi |

| (lit. ‘to packages’) | ‘me, of all people, who should know a lot about it’ |

| a palate | facciamo soldi a palate |

| (lit. ‘to spadefuls’) | ‘we make a large quantity of money’ |

| a valanghe | le firme che stanno arrivando a valanghe |

| (lit. ‘to avalanches’) | ‘signatures that are arriving in large quantity’ |

| a vagonate | ne possono vendere a vagonate |

| (lit. ‘to wagonloads’) | ‘they can sell a large quantity of them’ |

This kind of structures have been described in the literature as partially filled constructions (cf. Fillmore et al. 1998; as far as Italian is concerned, e.g., Piunno 2018, 2023; Simone and Piunno 2017; see also Goldberg 2006 for partially lexically specified constructions; Casadei 2024 for phraseological constructions), i.e. a subtype of phraseological unit characterised by:

Semi-fixed syntactic patterns;

Lexical variation and semantic restrictions;

Constructional meaning.

As partially filled constructions, these adverbial multiword expressions are composed of two (or more) portions in a fixed order (a): the first one represents a stable and unchanging part, always filled by the preposition a, while the second one admits only a limited set of lexical items (b); in this specific case, the adverbial multiword expressions taken into account share a common morpho-syntactic pattern, whose empty slot has to be filled by a nominal element.

| [fixed slot + variable slotsemantic restriction] |

| [a + NOUN<plural>] |

Generally, the nominal element shows some peculiar properties: at the morphological level, it appears exclusively in the plural form while at the semantic level it may belong to the class of containers or metonymically refer to its content (Piunno 2018: 197):

| [a + NOUN CONTAINER<plural>] |

| [a + badilate/carrellate/carrettate/palate/vagonate] |

This is the case of the nouns reported in (3) (e.g., badilate, carrellate, carrettate, palate and vagonate), each of which specify a container value (badile, carrello, carretto, pala and vagone), while the remaining nouns filling the slot (fiumi, mucchi, ondate and valanghe) do not.

At the semantic level, the whole structure shows a constructional meaning connected to ‘abundance’ (c), which is “predictable from the […] pattern and is shared by different sequences responding to the same restrictions” (Piunno 2023: 401).

Partially filled constructions cannot be considered as prototypically multiword expressions: firstly, they show a low degree of cohesion and syntactic fixity; secondly, they are characterized by different degrees of fixedness and so they are not completely lexicalised (Piunno 2023: 401). Despite this, they can be considered as constructions in terms of the framework of Construction Grammar (cf. among all, Croft 2001; Fillmore et al. 1998; Goldberg 1995, 2006; Hilpert 2013, 2014) because they represent a form-meaning pair conveying a conventional non-compositional or idiomatic semantic and pragmatic value (Fillmore et al. 1998: 501; reprised in Piunno 2023: 401).[5] These constructions also represent a phenomenon of regularity in the lexicon, although on a sociolinguistic level they are common in informal contexts of neo-standard varieties of Italian, and consequently not acceptable in formal speech or writing.

If we consider these adverbial constructions more closely, it is possible to identify a subgroup of partially filled constructions composed by the preposition a and a plural noun ending with an -ata suffix (4):

| [a + NOUN<plural>] |

| [a + badilate/carrellate/carrettate/ondate/palate/vagonate] ‘a lot, in large quantities’ |

Most of the nouns used represent instruments (e.g. badile ‘shovel’, carrello ‘cart’, pala ‘loader’) and the -ata suffix is used to turn nouns into punctual events (e.g. una carrettata, una palata…); for this reason when the nouns are employed in the singular form, they convey the meaning of ‘blow of X’, or ‘quantity lifted by means of X’ (5a);[6] when used in the plural, however, they lose their primary meaning connected to the instrument to acquire a quantitative high value, both in autonomy (5b) or within the construction (5c):

| una | badilata | di | terra |

| a | shovel | of | ground |

| ‘A quantity of ground lifted with a shovel.’ | |||

| badilate | di | soldi |

| shovels | of | money |

| ‘A big quantity of money.’ | ||

| soldi | a | badilate |

| money | to | shovels |

| ‘A big quantity of money.’ | ||

In the example (5c), the adverbial multiword acts as an intensifier enhancing the quantity connected to the noun soldi ‘money’, and losing the meaning connected to the instrument.

Although these structures were first introduced by Piunno (2018) into the broader topic of adjectival and adverbial modifiers, a qualitative study specifically devoted to the quantitative structures mentioned above is still missing. For this reason, the next section will provide an analysis of adverbial multiwords focusing on their combinatorial preferences. The aim is to show wherever these constructions select common combinatorial contexts and/or show peculiarities related to their specific structure.

3 Combinatorial context of use of the selected constructions

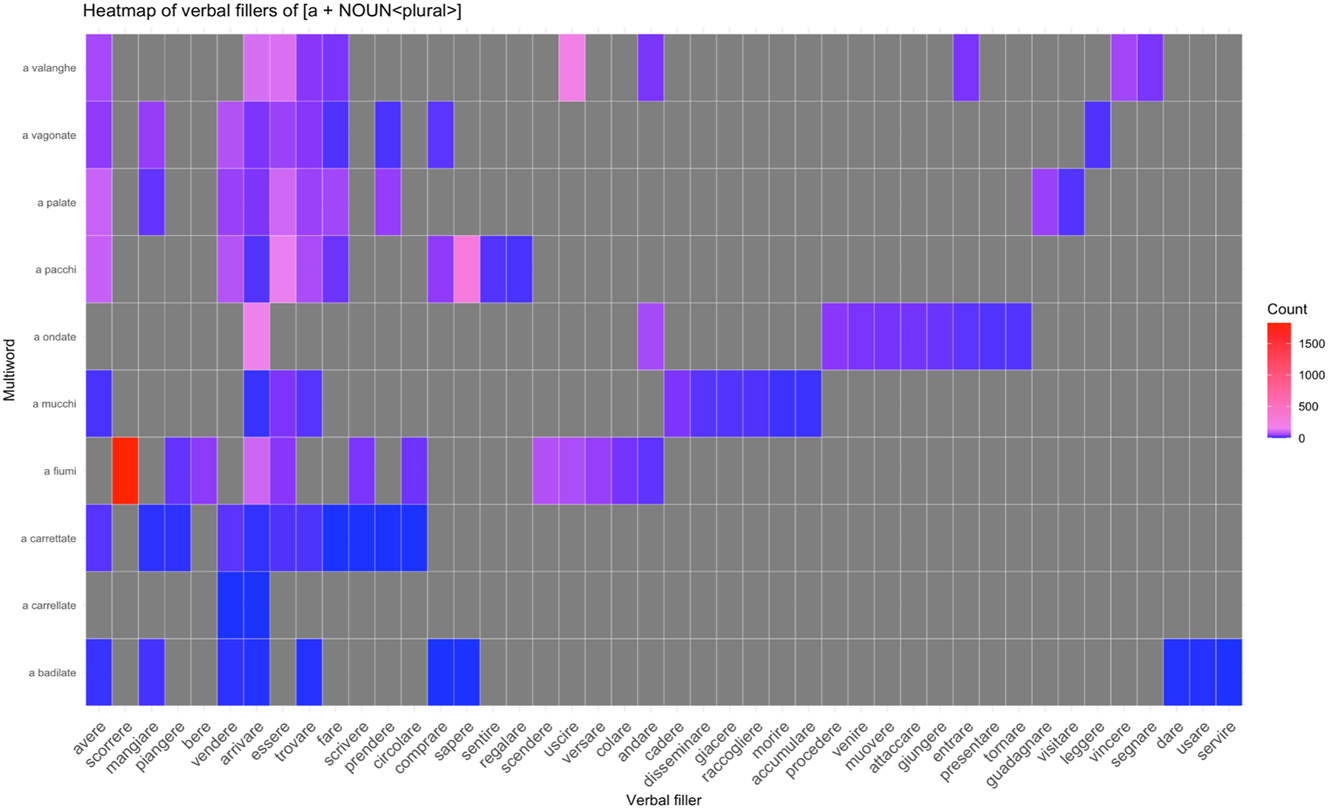

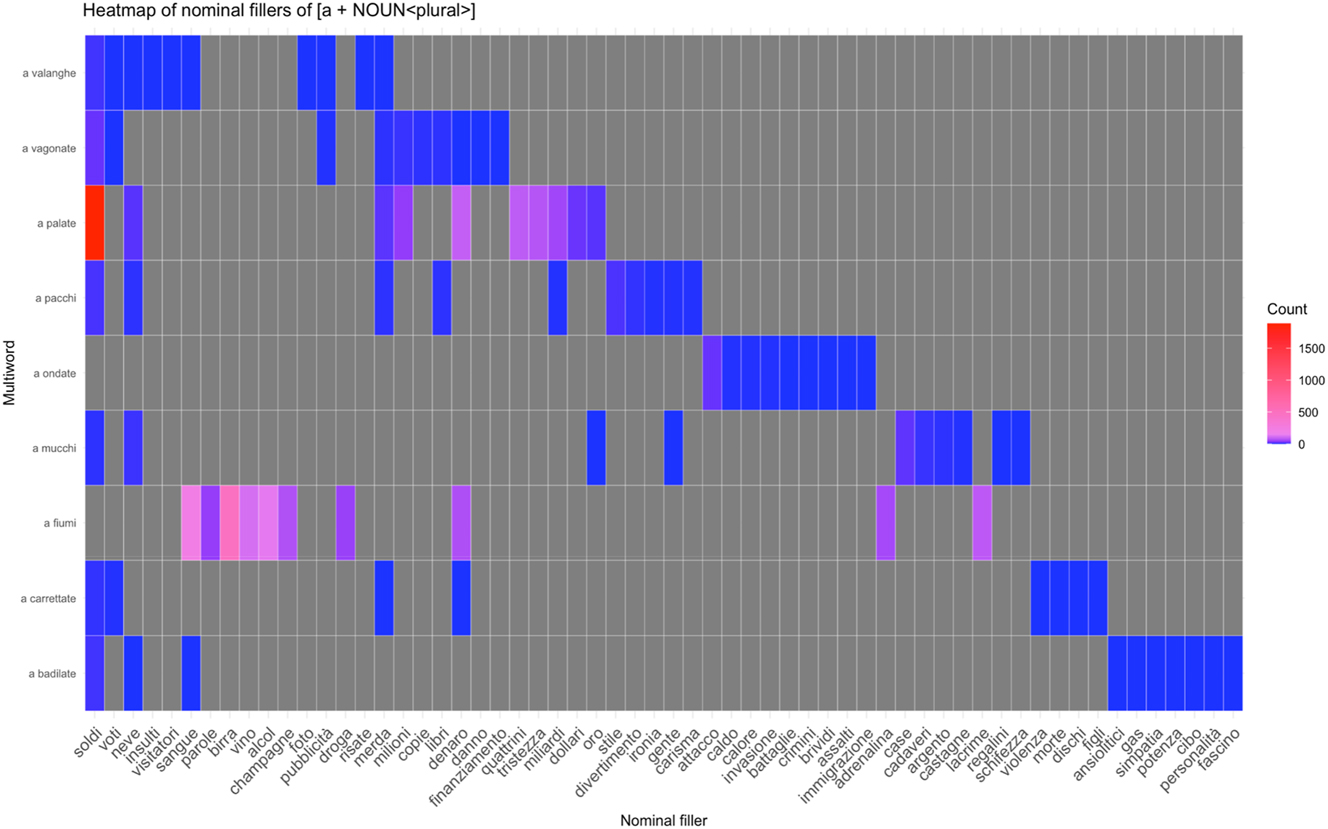

To provide a comparison of the verbal and nominal elements that appear in combination with each construction, data was extracted from the itTenTen20 corpus, which has been investigated using the advanced CQL functions of the Sketch Engine interface[7] (Kilgarriff et al. 2014). The list of partially filled constructions considered within this work (e.g., a badilate, a carrellate, a carrettate, a fiumi, a mucchi, a ondate, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe) was retried from Piunno (2018). After selecting the multiword expressions, the combinatorial contexts of use of each of them were taken into account: the 10 most frequent lemmas of the KWIC with an absolute frequency greater than 1 were selected for each partially filled construction, distinguishing between verbal and nominal items. The results concerning both groups are displayed in a heatmap using R,[8] made up as follows: on the vertical axis are listed (bottom-top in alphabetical order) the 10 multiword expressions considered;[9] the horizontal axis displays the 10 (if any) most frequent elements co-occurring with the selected partially filled constructions, following a random order. The connecting point between a multiword expression and the co-occurring element is represented by a cell. If there is a connection (i.e. if a linguistic element is selected by a construction as a combinatorial context of use) the box will be coloured. Besides, depending on the frequency of these structures within the corpus, the cell will assume a different colour: darker colours (tending towards blue) correspond to lower frequency values, whereas colours tending towards red symbolise a higher one. If two or more partially filled constructions share a common co-occurring element, this is only listed once on the x-axis. There will then be as many coloured boxes in the same column as there are multiword expressions involved.

The results connected to verbs are shown in Figure 1; those of nouns will be displayed in Figure 2.

Heatmap of verbal fillers.

Heatmap of nominal fillers.

As for verbal elements co-occurring with the partially filled constructions, 45 verb forms were extracted from the corpus. Most of them (29 out of 45) occur only in one construction, as shown in Table A.1. Within this group falls the verb scorrere ‘to flow’ with the highest absolute frequency (1826 tokens), which, however, occurs exclusively with the multiword expression a fiumi. The only verb attested with all adverbial partially filled constructions is arrivare ‘to arrive’ (475 tokens), of which some examples from the corpus are given in (6):

| messaggini | che | a | volte | arrivano | a |

| messages | that | to | times | arrive-pres.3pl | at |

| carrellate | |||||

| cartloads | |||||

| ‘Text messages that sometimes arrive in large quantities.’ | |||||

| la | sfiga | è arrivata | a | badilate |

| the | bad_luck | arrived-pst.3sg | to | shovels |

| ‘Bad luck arrived in abundance.’ | ||||

| un | giorno | o | l’ | altro | le | ordinazioni | arriveranno |

| the | day | or | the | other | the | orders | arrive-fut.3pl |

| a | mucchi | ||||||

| to | piles | ||||||

| ‘Someday orders will come in large quantities.’ | |||||||

| Oggi | sono | i | turisti | ad | arrivare | a |

| today | be-pres.3pl | the | tourists | to | arrive-inf.pres | to |

| vagonate | ||||||

| wagonloads | ||||||

| ‘Nowadays tourists arrive massively.’ | ||||||

The most shared verbal elements include avere ‘to have’ (309 token, 7 constructions), essere ‘to be’ (491 tokens, 7 constructions), trovare ‘to find’ (199 tokens, 7 constructions), vendere ‘to sell’ (202 tokens, 6 constructions) and fare ‘to do’ (113 tokens, 5 constructions). The detailed list with frequencies is shown in Tables A.2 and A.3 in Appendix. The selected multiword expressions share a predilection for light verbs which, given their broad meaning, can be selected as co-occurring elements by several constructions.

Frequency counts reveal that the number of tokens is at the lowest values, especially with the multiword expressions a badilate, a carrellate e a carrettate, whose values do not exceed 30 tokens. On the contrary, some of the elements combining with a pacchi, a palate and a valanghe are closer to 500. The only verb combined with the construction that reaches the top of the scale is the already mentioned scorrere, the only one represented by the colour red.

Based on these data, the multiword expressions that share the highest number of verbal elements with each other are a carrettate, a pacchi, a palate and a vagonate, with among all the 6 most frequent verbs. On the contrary, a fiumi and a ondate seem to differ the most from all the others: to begin with, a fiumi shares three verbs (i.e. piangere ‘to cry’, scrivere ‘to write’ and circolare ‘to circulate’) exclusively with a carrettate, in addition to the two verbs shared by all the multiword expressions (i.e. essere ‘to be’ and arrivare ‘to arrive’); besides, a ondate shares only two verbs with the other partially filled constructions, both of them related to motion: arrivare (in common with all) and andare ‘to go’ with a fiumi and a valanghe.

As for the nominal combinatory contexts, the number of total nominal items is much higher than the verbal ones, as shown in Figure 2.

As displayed in the heatmap, only nine of the selected multiword are represented: in fact, in our data, a carrellate does not occur with nouns as possible co-occurring elements.

More generally, 59 nouns are employed by one or more multiword, against the 45 verbs discussed above. As in the previous case, most of them (48 out of 59) occur in a single construction, as shown in Table A.4. The nouns that combine with more than four constructions are: soldi ‘money’ (1,941 tokens, 7 constructions), followed by denaro ‘money’ (155 tokens, 5 constructions), neve ‘snow’ (30 tokens, 5 constructions) and merda ‘shit’ (28 tokens, 5 constructions). The detailed list with frequencies is shown in Tables A.5 and A.6 in Appendix. These four nouns are related to solid referents, two of which belong to the economic sphere (soldi and denaro). This domain also includes other kind of nouns, as shown in the following examples (7):

| non | che | gli | spiaccia | la | prospettiva | di |

| not | that | him | regret-pres.3sg | the | perspective | of |

| una | futura | disponibilità | di | dollari | a | palate |

| a | future | availability | of | dollars | to | spadefuls |

| ‘He doesn’t mind the perspective of a future availability of money galore.’ | ||||||

| iter | amministrativi | velocizzati | e | autoreferenziali, |

| processes | administratives | accelerated | and | self-referentials |

| finanziamenti | a | vagonate | ||

| fundings | to | wagonloads | ||

| ‘Fast-tracked and self-referential administrative processes, a lot of fundings.’ | ||||

| soldi, | milioni | a | vagonate |

| money | millions | to | wagonloads |

| ‘Money, millions galore.’ | |||

The economic domain is well represented by several nominal items, such as dollari ‘dollars’ (7a) and quattrini ‘a few pennies’ (employed exclusively by a palate), finanziamenti ‘fundings’ (a vagonate, 7b), milioni ‘millions’ (shared by a palate and a vagonate, 7c) and miliardi ‘billions’ (a pacchi and a palate).

Despite the broader variety of co-occurring nominal items, it is possible to distinguish several categories of nouns according to the specific construction: a palate is used with concrete references related to the above-mentioned economic domain; a ondate is mostly used with action names related to war (e.g. attacco ‘attack’, battaglie ‘battles’, crimini ‘crimes’, invasione ‘invasion’, assalti ‘assaults’) while a fiumi is used instead with liquid referents (e.g. alcol ‘alcohol’, birra ‘beer’, vino ‘wine’, champagne).

By looking at frequency counts, as in the previous heatmap, only one item reaches the top of the scale with more than 1,500 tokens (e.g. soldi ‘money’), while the majority of the nouns have low values. The construction that stands out among all for higher items values is a fiumi followed by a palate, both characterized by the shades of colour pink.

Overall, it is apparent that the selected multiword expression acts as intensifiers of both verbal and nominal items. The number of verbs is lower than nouns: the first category includes many verbs with broad meanings that can be employed by a high number of multiwords; however, the presence of many light verbs leads to major difficulties in identifying the combinatorial preferences of each multiword expressions, with the exception of a few cases. On the contrary, the second one has a higher number of items, but it is easier to group the nouns employed by a single fully filled construction.

A fiumi turns out to be one of the multiword expressions that differs most in the choice of co-occurring elements and only partially share combinatorial contexts with the other adverbial constructions: in fact, it is characterised more by verbal and, especially, nominal items related to a liquidity semantics, as opposed to the others who prefer more concrete nouns and verbs. For these reasons, a case study based on the multiword a fiumi will be proposed.

4 The multiword expression a fiumi

As already mentioned, this case study relies on data extracted from the itTenTen20 corpus. Only the first 300 random concordances (out of 6,550) of the corpus were manually checked and annotated: each occurrence of the multiword a fiumi was classified depending on the combinatorial contexts of use, in order to identify the lexical items most frequently co-occurring with the multiword expression; afterwards fillers were lemmatised and classified according to POS.

231 out of the original 300 concordances were considered for qualitative analysis. All the structures that could not be associated with the pattern under investigation were rejected, as in (8):

| si | lascia | andare | a | fiumi | di | retorica |

| himself | leave-pres.3sg | go-inf.pres | to | rivers | of | rhetoric |

| senza | fine | |||||

| without | end | |||||

| ‘[he] indulges in endless streams of rhetoric.’ | ||||||

In the example considered, fiumi acts as intensifier on its own: although the preposition a and the plural noun occur, the two elements together do not form the pattern analysed in this work and for this reason they were rejected.

At first, the frequency of the constructions within the selected concordances will be presented; subsequently, the constructions will be analysed both on a syntactic and semantic level.

4.1 Frequency

The dataset is composed in Table 2.

Dataset from itTenTen20.

| Types | Tokens | Hapax | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VERB + [a + fiumi] | 27 | 137 | 18 |

| NOUN + [a + fiumi] | 40 | 94 | 31 |

The resulting dataset consists of 231 tokens, 67 types and 49 hapax, with a TTR of 0.29. Considering the combinatorial contexts of use, the multiword a fiumi combines both with verbal and nominal items to form adverbial constructions. More specifically, there are two broader semi-specified constructions, whose pattern can be represented respectively as follow:

| VERB + [a + fiumi] |

| NOUN + [a + fiumi] |

According to the dataset, 137 tokens (27 types) show the multiword expression preceded by a verb, whereas 94 tokens (40 types) are preceded by a noun. The results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Frequency of the instances of the partially filled construction VERB + [a + fiumi] in the selected concordances.

| Partially filled construction with VERB + [a + fiumi] | Frequency |

|---|---|

| scorrere a fiumi | 96 |

| ‘to flow in large quantities’ | |

| bere a fiumi | 5 |

| ‘to drink in large quantities’ | |

| scendere a fiumi | 4 |

| ‘to descend in large quantities’ | |

| entrare a fiumi | 3 |

| ‘to enter in large quantities’ | |

| essere a fiumi | 3 |

| ‘to be in large quantities’ | |

| sgorgare a fiumi | 3 |

| ‘to spring in large quantities’ | |

| correre a fiumi | 3 |

| ‘to run a lot’ | |

| riversare a fiumi | 2 |

| ‘to pour in large quantities’ |

Frequency of the instances of the partially filled construction NOUN + [a + fiumi] in the selected concordances.

| Partially filled construction with NOUN + [a + fiumi] | Frequency |

|---|---|

| birra a fiumi | 26 |

| ‘beer in large quantities’ | |

| alcol a fiumi | 15 |

| ‘alcohol in large quantities’ | |

| lacrime a fiumi | 5 |

| ‘tears in large quantities’ | |

| sangue a fiumi | 5 |

| ‘blood in large quantities’ | |

| vino a fiumi | 4 |

| ‘wine in large quantities’ | |

| adrenalina a fiumi | 2 |

| ‘adrenalin in large quantities’ | |

| energia a fiumi | 2 |

| ‘energy in large quantities’ | |

| pensieri a fiumi | 2 |

| ‘thoughts in large quantities’ |

By looking at verbal fillers, the most frequent constructions are scorrere a fiumi (96 tokens), bere a fiumi (5 tokens) and scendere a fiumi (4 tokens), while birra a fiumi (26 tokens) and alcol a fiumi (15 tokens) are the most frequent expressions with nominal fillers.

The results related to the frequency of this partially filled construction in the selected concordances do not differ much from those of the corpus as a whole. In fact, most of the values represented in Tables 3 and 4 match with the frequencies of Tables 5 and 6.

Frequency of the instances of the partially filled construction VERB + [a + fiumi] in the corpus.

| Partially filled construction with VERB + [a + fiumi] | Frequency |

|---|---|

| scorrere a fiumi | 1,853 |

| ‘to flow in large quantities’ | |

| arrivare a fiumi | 109 |

| ‘to arrive in large quantities’ | |

| sgorgare a fiumi | 78 |

| ‘to spring in large quantities’ | |

| versare a fiumi | 44 |

| ‘to pour in large quantities’ | |

| essere a fiumi | 38 |

| ‘to be in large quantities’ | |

| bere a fiumi | 38 |

| ‘to drink in large quantities’ | |

| scrivere a fiumi | 34 |

| ‘to write a lot’ | |

| colare a fiumi | 28 |

| ‘to leak in large quantities’ |

Frequency of the instances of the partially filled construction NOUN + [a + fiumi] in the corpus.

| Partially filled construction with NOUN + [a + fiumi] | Frequency |

|---|---|

| birra a fiumi | 482 |

| ‘beer in large quantities’ | |

| sangue a fiumi | 221 |

| ‘blood in large quantities’ | |

| alcol a fiumi | 137 |

| ‘alcohol in large quantities’ | |

| vino a fiumi | 115 |

| ‘wine in large quantities’ | |

| lacrime a fiumi | 80 |

| ‘tears in large quantities’ | |

| champagne a fiumi | 65 |

| ‘champagne in large quantities’ | |

| denaro a fiumi | 62 |

| ‘money in large quantities’ | |

| adrenalina a fiumi | 51 |

| ‘adrenalin in large quantities’ |

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, scorrere a fiumi is the most frequent construction both considering its partial (96 tokens) and absolute frequency (1,853 tokens), as well as the second one birra a fiumi (26 and 482 tokens respectively in Tables 4 and 6). By comparing the values shown in the previous tables, the similarities affect adverbial multiword expression mostly preceded by a noun: in fact, 6 out of 8 of the most frequent constructions are also present in the top 8 of the entire corpus, with slight differences in ranking (birra a fiumi, alcol a fiumi, lacrime a fiumi, sangue a fiumi, vino a fiumi and adrenalina a fiumi); the proportion is lower for verbal constructions, with only 4 out of 8 overlapping items (scorrere a fiumi, bere a fiumi, essere a fiumi, sgorgare a fiumi). After providing these preliminary considerations regarding the frequency, a qualitative analysis of a fiumi will be provided in the next sub-sections: in Section 4.2, the morpho-syntactic and semantic properties of the extracted data will be illustrated, while in Section 4.3, the contexts of the multiword expression a fiumi will be analysed, distinguishing between the co-occurring verbal and nominal elements.

4.2 Morpho-syntactic and semantic properties

As already explained, the adverbial multiword selected for this case study shows the abstract construction [a + X NOUN<plural>]: more specifically, it is composed by the preposition a followed by the plural noun fiumi (lit. rivers). The two parts always occur adjacently, and do not allow the insertion[10] of modifiers such as numerals or other quantifiers:

| le parole scorrevano a fiumi |

| ‘Words were flowing’ (lit. ‘words were flowing to rivers’) |

| *le parole scorrevano a tanti fiumi |

| (lit. ‘words flowed at many rivers’) |

| *le parole scorrevano a mille fiumi |

| (lit. ‘words flowed at thousands of rivers’) |

In the cases under consideration, the slot of the multiword pattern subject to lexical variation is filled by the noun fiumi, which responds to the same semantic restrictions of the nouns mentioned before (see Section 2): when used in the plural, in fact, fiumi loses its primary meaning of ‘large natural stream of water flowing’ to acquire a more abstract one as ‘large quantity of a flowing substance’[11] (11).

| Large stream of water > large quantity of a liquid |

Despite the shift in meaning, the semantics associated with liquidity remains crucial for the selection of the elements with which the multiword expressions co-occurs: in fact, as already emerged in Section 2 and as will be seen in more detail in the course of this section, they mostly designate liquid referents or related to a liquid dimension.

A further step can be represented by a transition from a liquid dimension to a different one:

| Large stream of water > large quantity of something liquid > large quantity of something (not necessarily liquid) |

A fiumi not only combines with nouns and verbs belonging to a liquid domain, but also joins concrete or abstract referents that are treated as liquids due to a metaphorical mechanism. This change of meaning is made clear by considering the previous example in (10), where the quantity of words spoken (le parole) is metaphorically assimilated to a continuous flow of water (scorrevano a fiumi).

As with other adverbial multiwords, a fiumi refers to an indefinite high quantity. It is not possible to determine the quantity associated with the noun or verb that appears in the combinatorial context and only the high degree of the quantity conveyed by the entire construction can be highlighted. Unlike other intensifiers, however, the multiword is strongly characterised by the connection between the evaluative phenomenon and its duration: more precisely, a fiumi does not only convey an intensified meaning (of a high quantity) but extends that value over a period of time:

| a fiumi → high quantity of X in non-limited period Y. |

Although all selected multiwords convey a high quantity, the degree of indefiniteness and duration in time seem to vary depending on the noun occurring in the pattern: in the case of fiumi, the shift of meaning from ‘large stream of water flowing’ to ‘large quantity of something’ preserves a semantic dimension related to the ‘flow’; this ensures that in the transposition of meaning what emerges is the duration of the ‘flow’ that is not predetermined in time and does not begin or culminate at a precise moment.

To summarise then, at the semantic level, the multiword acts as a modifier at a phrase-level and conveys a meaning that could be summarised in the hyperbolic formula ‘X in large quantity and continuously’. More specifically, it behaves like a quantity intensifier of the nominal or verbal item with which it occurs:

| lexemeintensified [lexemeintensifier] |

| VERB/NOUN [a + fiumi] |

The intensifying meaning of the multiword is shown in the following example:

| Lo | scandalo | dei | soldi | pubblici | regalati | a |

| The | scandal | of | money | public | give_away-ptcp.pst | to |

| fiumi | ||||||

| rivers | ||||||

| ‘The scandal of public money given away in large quantities.’ | ||||||

In the example considered (14), the multiword intensifies the action expressed by the verb regalare ‘to give’, enhancing the large amount of money wasted over a period of time. In this way, a fiumi can therefore be considered a grammaticalised form that passes from a concrete meaning to convey an evaluative one, due to a functional specialisation and a loss of referentiality whereby intensification remains instead of quantity.

In the last Section 4.3 the combinatorial contexts of use of the multiword will be considered.

4.3 Combinatorial contexts of use of the multiword a fiumi

As already discussed, the multiword a fiumi combines both with nouns and verbs in order to convey a quantitative intensified meaning.

Starting from verbs, the multiword co-occurs with movement and action verbs with 137 occurrences. Movement verbs belong to different classes, denoting processes that are protracted in time (e.g. scorrere ‘to flow’), or more punctual and dynamic actions (e.g. arrivare ‘to arrive’, sgorgare ‘to spring’). Most of these verbs express an action involving the movement (concrete or abstract) of a liquid substance, usually an alcoholic beverage (43 tokens) or blood (26 tokens):

| tanti | visitatori, | meno | espositori | del | passato | ed | il |

| many | visitors | less | exhibitors | of | past | and | the |

| whisky | che | scorreva | a | fiumi | |||

| whisky | that | flow-pst.3sg | to | rivers | |||

| ‘Many visitors, fewer exhibitors than in the past and a lot of whisky flowing.’ | |||||||

| Ho visto | il | sangue | scorrere | a | fiumi |

| See-pst.3sg | the | blood | flow-inf.pres | to | rivers |

| ‘I saw the blood flowing.’ | |||||

As shown in example (16), scorrere ‘to flow’ is once again one of the most frequently used verbs of movement both for beverages (16a) or blood (16b).

Although the verbal items belong to different actional classes, their combination with the multiword highlights more strongly the trait of [+durativeness]: it might almost be supposed that, when combined with a fiumi, verbs of accomplishment and achievement such as arrivare or sgorgare turn into verbs of activity indicating processes that take place in non-limited periods of time. This can be confirmed by the fact that conveying an iterative meaning, the multiword emphasises the protraction of the action over time:

| scendeva | acqua | a | fiumi |

| descent-pst.3sg | water | to | rivers |

| ‘It rained a lot.’ | |||

| le | lacrime | ricordo | bene | che | sgorgarono |

| the | tears | remember-pres.1sg | good | that | spring-pst.3pl |

| a | fiumi | ||||

| to | rivers | ||||

| ‘I cried a lot.’ | |||||

Combined with the multiword, the verbs scendere ‘descent’ (17a) and sgorgare ‘spring’ (17b) – used idiomatically to describe the actions of raining and crying – show a sort of protraction of the action of over time instead of denoting sudden changes of state. In (17a) the progressive meaning of the sentence is supported by the use of the imperfect tense, which could be used on its own to convey a progressive meaning; on the contrary, in (17b) the multiword a fiumi emphasises the aspectual change of sgorgarono which turns into an ongoing action.

In addition to movement verbs, the multiword also combines with verbs that actively involve a subject doing something, such as bere ‘to drink’ (five tokens in selected concordances).

The semantic field of drinking prevails also in the choice of the nominal items with which the multiword combines, where there is a combinatorial preference for items linked to beverage. As already pointed out in the comparison in Section 3, liquid nouns represent fillers employed almost only by a fiumi, while the other multiwords prefer to combine with solid referents. Hence, this preference characterises liquids (and more specifically spirits) as exclusive fillers of a fiumi, emphasising the semantic specialisation of the items that intensifies.

Apart from two cases (e.g. cappuccini and coca-cola), the beverage is always alcoholic, as in the following examples (18):

| alcol | a | fiumi | e | cibo | a | go go |

| alcohol | to | rivers | and | food | to | many |

| salvano | le | uscite | di | moltissimi | giovani | |

| save-pres.3pl | the | exits | of | many | young | |

| ‘Unlimited alcohol and food save the nights of many young people.’ | ||||||

| ottima | acustica | praticamente | ovunque | e | birra | a |

| excellent | acoustics | practically | everywhere | and | beer | to |

| fiumi | ||||||

| rivers | ||||||

| ‘Great acoustics almost everywhere and beer galore.’ | ||||||

| Urla, | abbracci, | champagne | a | fiumi |

| Scream | hughes | champagne | to | rivers |

| ‘Screams, hugs and a lot of champagne.’ | ||||

The multiword’s predilection for nouns associated with alcohol marks once again a semantics connected to excess; in (18a), for example, a fiumi acts as an intensifier of the noun it precedes (alcol) and highlights the high quantity of the liquid substance considered, as if it was continuous and never-ending during the cocktail dinner.

The preference for excess-related items is also found in the choice of other non-liquid fillers, such as drugs (four tokens in total):

| il | mito | della | bella | vita | fatta | di |

| the | mith | of | pretty | life | make-ptcp.pst | of |

| soldi | facili, | cocaina | a | fiumi | ||

| money | easy | cocaine | to | rivers | ||

| ‘The myth of a good life made of easy money and abuse of cocaine.’ | ||||||

| Con | il | doping | a | fiumi […] | andrebbe |

| With | the | doping | to | rivers […] | go-cond.pres.3sg |

| anche | lui | ||||

| too | him | ||||

| ‘With doping he would also go.’ | |||||

In addition to the cases just discussed, there are other examples of non-liquid fillers, such as abstract nouns (20):

| pensieri | a | fiumi | scorrono | veloci |

| thoughts | to | rivers | flow-pres.3pl | fast |

| ‘(flow of) thoughts flowing fast.’ | ||||

| telegiornali | pilotati | dalle | segreterie | di | partito, |

| newscast | drive-ptcp.pst | of_the | secretariat | of | party |

| pubblicità | a | fiumi | |||

| advertisement | to | rivers | |||

| ‘News programmes piloted by party secretariats, continuous flow of advertising.’ | |||||

Other examples of that kind are adrenalina ‘adrenaline’ and energia ‘energy’ (both represented by two tokens), emozioni ‘emotions’ and libidine ‘lust’ (one token each). When they co-occur with a fiumi, these names become gradual and can be analysed as action names indicating processes: in other words, as displayed by the example above, many thoughts come in the course of time (20a), as well as many advertisements (20b) are broadcast on television. In the light of this, a fiumi can be considered as a trigger for a reading as a mass noun of the modified noun, hence only the high degree of the quantity conveyed by this last one.

The data extracted and the examples analysed therefore highlight how the semantics associated with liquidity is deeply embedded in the multiword considered. A fiumi mostly selects referents belonging to a liquid semantics, both in the case of nouns and verbs: the group [+liquid] includes movement verbs (e.g., scorrere, entrare, andare, sgorgare, approdare) and verbs concerning the consumption or flowing of a liquid (e.g., piangere, bere, iniettare, sudare), as well as several nominal fillers, such as items related to beverages (e.g., cappuccini, birra, alcol, vino, champagne, spumante, grappa), natural phenomena (e.g., acqua, pioggia) and body fluids (e.g., sangue, lacrime). Nevertheless a fiumi also selects lexemes not belonging to the liquid dimension [-liquid], but whose combination within the pattern leads to a transformation into an element as part of a flow: this is confirmed especially by several nominal fillers, such as the ones related to drugs (e.g., cocaina, erba e coca, spaccio, doping), money (e.g., miliardi, soldi, contanti, fonte di denaro, scommesse), food (e.g. cioccolato, cioccolata, crema) and emotions and moods (e.g., emozioni, pensieri, risate, adrenalina, energia).

5 Conclusions

This study explored some Italian adverbial partially filled constructions, i.e. a subtype of phraseological unit formed by the preposition a and a plural noun, conveying a quantitative and iterative meaning connected to ‘abundance’. After describing the syntactic and semantic properties of this category as a whole, a comparison of the combinatorial contexts of the selected adverbial constructions was made. What emerged from the analysis of the data is twofold. Considering the verbal items, the selected multiword expressions preferably combine with light verbs in order to convey an intensifying meaning; the common use of verbs such as andare ‘to go’, essere ‘to be’ and avere ‘to have’ demonstrates how the adverbial constructions can be interchanged without entailing differences in the meaning conveyed by the entire construction.

As for the co-occurring nominal elements, there is greater specialisation in the choice of nouns; in fact, there are stronger differences between one multiword and the other: to provide some examples, a palate combines with nouns related to the domain of ‘money’, while a ondate is mostly used with action names related to ‘war’. These results demonstrate at the same time the high combinatoriality with nominal items belonging to different semantic fields and a finer selection of co-occurring elements depending on the multiword expression used.

What is possible to observe is that, in most cases, the broader construction involves both a noun and a verb that are linked by a semantic relation, as in the following example:

| avrei guadagnato | oro | a | carrettate |

| earn-cond.pst.1sg | gold | to | cartloads |

| ‘I would have earned gold in big quantity.’ | |||

| il whisky | che | scorreva | a | fiumi |

| whisky | that | flow-pst.3sg | to | rivers |

| ‘A lot of whisky flowing.’ | ||||

In (21), the intensifying value conveyed by the construction applies to both the verbs (guadagnare ‘earn’, scorrere ‘flow’) and the nouns (oro ‘gold’, whisky ‘whiskey’) simultaneously, enhancing the quantity of gold earned in (21a) and the quantity of whisky flowing in (21b).

Despite the loss of referentiality shared by all the multiword expressions, the extracted data also highlighted some differences according to the noun employed within the pattern: in the case of constructions with an instrument nouns ending with an -ata suffix (e.g. badilata ‘shot given with a shovel’), the meaning conveyed is more attached to the quantitative dimension; on the other hand, constructions with the multiword a fiumi seems to differ from all the expressions of the previous case and convey a more abstract meaning. For this reason, a study based on this specific multiword expression was also carried out.

Besides sharing the same morpho-syntactic and semantic pattern of the other adverbial constructions, the multiword expression a fiumi acts as a quantity intensifier of the lexemes with which it occurs, mainly nominal and verbal items related to the semantic domain of liquidity (e.g. scorrere a fiumi ‘to flow in large quantities’, birra a fiumi ‘beer in large quantities’). When it is used inside the pattern, fiumi loses its primary meaning of ‘large natural stream of water flowing’ to specialize and convey the lexicalized meaning of ‘large quantity of (something)’: in the metaphorical switch of meaning, the name preserves the semantic dimension connected to the ‘flow’ whose focus shift from quantity to the duration of the process connected to the quantity expressed over a non-determined period of time, as illustrated in (22):

| il | buon | vino | e | il | rum | della | Martinica | scorrevano | a |

| the | good | wine | and | the | rum | of_the | Martinique | flow-pst.3pl | to |

| fiumi | |||||||||

| rivers | |||||||||

| ‘Good wine and rum from Martinique were flowing in large quantities.’ | |||||||||

The meaning conveyed in (22) can be resumed as ‘high quantity of wine and rum continuously flowing for a long period of time’. In this way, a fiumi not only acts as a quantitative modifier, but also as adverbial intensifier conveying an iterative value linked to the repetition and the protraction of the action expressed.

Looking at fillers more closely, a fiumi shares a restricted number of co-occuring elements with the other structures analysed: in fact, it mostly selects nouns and verbs related to the flowing of substance (in particular alcoholic beverage), as opposed to the other multiwords, almost always combined with more solid referents.

Although the semantics associated with ‘duration’ seems to affect the other constructions employing a noun related to natural events (e.g. a valanghe, a ondate), the analysis showed that a fiumi accurately selects its combinatorial contexts: in fact, all the selected nominal elements (both concrete and liquid) can be treated as flowing substances, as well as verbal ones denote the protraction of actions or movements over a long period of time.

The results obtained from this work open avenues for further research on quantitative adverbial partially filled constructions: firstly, to perform a qualitative analysis also on the other selected multiword expressions, in order to highlight more precisely the features of each structure; secondly, to compare the results of the qualitative analysis, in order to highlight more strongly differences and similarities between the combinatorial contexts of use of the selected constructions; last but not least, to extend the analysis also on the other Romance languages where this kind of constructions are attested (Piunno 2018), such as Spanish.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

See Tables A.1, A.2, A.3, A.4, A.5, and A.6.

Verbal fillers employed only by one adverbial multiword expression.

| Verbal filler | Adverbial multiword using the verbal filler | Number of adverbial multiwords |

|---|---|---|

| accumulare ‘to accumulate’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| attaccare ‘to attack’ | a ondate | 1 |

| bere ‘to drink’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| cadere ‘to fall’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| colare ‘to pour’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| dare ‘to give’ | a badilate | 1 |

| disseminare ‘to disseminate’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| entrare ‘to enter’ | a ondate | 1 |

| giacere ‘to lie’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| giungere ‘to arrivare’ | a ondate | 1 |

| guadagnare ‘to earn’ | a palate | 1 |

| leggere ‘to read’ | a vagonate | 1 |

| morire ‘to die’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| muovere ‘to move’ | a ondate | 1 |

| presentare ‘to present’ | a ondate | 1 |

| procedere ‘to proceed’ | a ondate | 1 |

| raccogliere ‘to collect’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| regalare ‘to give’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| scendere ‘to descend’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| scorrere ‘to flow | a fiumi | 1 |

| segnare ‘to score a goal’ | a valanghe | 1 |

| sentire ‘to hear’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| servire ‘to serve’ | a badilate | 1 |

| tornare ‘to return’ | a ondate | 1 |

| usare ‘to use’ | a badilate | 1 |

| venire ‘to come’ | a ondate | 1 |

| versare ‘to pour’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| vincere ‘to win’ | a valanghe | 1 |

| visitare ‘to visit’ | a palate | 1 |

Most frequent verbal fillers of the selected multiwords.

| Verbal filler | Adverbial multiwords using the verbal filler | Number of adverbial multiwords |

|---|---|---|

| arrivare ‘to arrive’ | a badilate, a carrellate, a carrettate, a fiumi, a mucchi, a ondate, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 8 |

| avere ‘to have’ | a badilate, a carrettate, a mucchi, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 7 |

| essere ‘to be’ | a carrettate, a fiumi, a mucchi, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 7 |

| fare ‘to do’ | a carrettate, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 5 |

| trovare ‘to find’ | a badilate, a carrettate, a mucchi, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 6 |

| vendere ‘to sell’ | a badilate, a carrellate, a carrettate, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate | 6 |

Number of tokens of the most frequent verbal fillers of the selected multiwords.

| avere | essere | fare | arrivare | vendere | trovare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘to have’ | ‘to be’ | ‘to do’ | ‘to arrive’ | ‘to sell’ | ‘to find’ | |

| a badilate | 6 | – | – | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| a carrellate | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | – |

| a carrettate | 15 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 16 | 11 |

| a fiumi | – | 35 | – | 102 | – | – |

| a mucchi | 10 | 30 | – | 6 | – | 15 |

| a ondate | – | – | – | 169 | – | – |

| a pacchi | 93 | 144 | 22 | 13 | 69 | 56 |

| a palate | 95 | 104 | 49 | 30 | 44 | 45 |

| a vagonate | 39 | 45 | 12 | 30 | 67 | 34 |

| a valanghe | 51 | 121 | 28 | 115 | – | 35 |

| Total tokens | 309 | 491 | 113 | 475 | 202 | 199 |

Nominal fillers employed only by one adverbial multiword.

| Nominal filler | Adverbial multiword using the nominal filler | Number of adverbial multiwords |

|---|---|---|

| adrenalina ‘adrenaline’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| alcol ‘alcohol’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| ansiolitici ‘anxiolytics’ | a badilate | 1 |

| argento ‘silver’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| assalti ‘assaults’ | a ondate | 1 |

| attacco ‘attack’ | a ondate | 1 |

| battaglie ‘battles’ | a ondate | 1 |

| birra ‘beer’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| brividi ‘shivers’ | a ondate | 1 |

| cadaveri ‘corpses’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| caldo ‘hot’ | a ondate | 1 |

| calore ‘heat’ | a ondate | 1 |

| carisma ‘charisma’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| case ‘houses’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| castagne ‘chestnuts’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| champagne | a fiumi | 1 |

| cibo ‘food’ | a badilate | 1 |

| copie ‘copies’ | a vagonate | 1 |

| crimini ‘crimes’ | a ondate | 1 |

| danno ‘damage’ | a vagonate | 1 |

| dischi ‘records’ | a carrettate | 1 |

| divertimento ‘fun’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| dollari ‘dollars’ | a palate | 1 |

| droga ‘drug’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| fascino ‘charm’ | a badilate | 1 |

| figli ‘children’ | a carrettate | 1 |

| finanziamento ‘financing’ | a vagonate | 1 |

| foto ‘photo’ | a valanghe | 1 |

| gas | a badilate | 1 |

| immigrazione ‘immigration’ | a ondate | 1 |

| insulti ‘insults’ | a valanghe | 1 |

| invasione ‘invasion’ | a ondate | 1 |

| ironia ‘irony’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| lacrime ‘tears’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| morte ‘death’ | a carrettate | 1 |

| parola ‘word’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| personalità ‘personality’ | a badilate | 1 |

| potenza ‘power’ | a badilate | 1 |

| quattrini ‘beggars’ | a palate | 1 |

| regalini ‘little gifts’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| risate ‘laughter’ | a valanghe | 1 |

| schifezza ‘rubbish’ | a mucchi | 1 |

| simpatia ‘sympathy’ | a badilate | 1 |

| stile ‘style’ | a pacchi | 1 |

| tristezza ‘sadness’ | a palate | 1 |

| vino ‘wine’ | a fiumi | 1 |

| violenza ‘violence’ | a carrettate | 1 |

| visitatori ‘visitors’ | a valanghe | 1 |

Most frequent nominal fillers of the selected multiwords.

| Nominal filler | Adverbial multiwords using the nominal filler | Number of adverbial multiwords |

|---|---|---|

| denaro ‘money’ | a carrettate, a fiumi, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate | 5 |

| merda ‘shit’ | a carrettate, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 5 |

| neve ‘snow’ | a badilate, a mucchi, a pacchi, palate, a valanghe | 5 |

| soldi ‘money’ | a badilate, a carrettate, a mucchi, a pacchi, a palate, a vagonate, a valanghe | 7 |

Number of tokens of the most frequent nominal fillers of the selected multiwords.

| soldi | neve | merda | denaro | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘money’ | ‘snow’ | ‘shit’ | ‘money’ | |

| a badilate | 8 | 2 | – | – |

| a carrellate | – | – | – | – |

| a carrettate | 5 | – | 2 | 5 |

| a fiumi | – | – | – | 62 |

| a mucchi | 4 | 7 | – | – |

| a ondate | – | – | – | – |

| a pacchi | 1886 | 15 | 16 | 89 |

| a palate | 95 | 104 | 49 | 30 |

| a vagonate | 20 | – | 4 | 2 |

| a valanghe | 8 | 2 | 2 | – |

| Total tokens | 1941 | 30 | 28 | 155 |

References

Adler, Silvia & Maria Asnès. 2013. Qui sème la quantification récolte l’intensification. Langue Française 177(1). 9–22. https://doi.org/10.3917/lf.177.0009.Search in Google Scholar

Anscombre, Jean-Claude & Irène Tamba. 2013. Autour du concept d’intensification. Langue Française 177(1). 3–8. https://doi.org/10.3917/lf.177.0003.Search in Google Scholar

Berthelon, Christiane. 1955. L’expression du haut degré en français contemporain: essai de syntaxe affective. Berne: A. Francke.Search in Google Scholar

Bolinger, Dwight. 1972. Degree words. Berlin & Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110877786Search in Google Scholar

Cacchiani, Silvia. 2011. Intensifying affixes across Italian and English. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 47(4). 758. https://doi.org/10.2478/psicl-2011-0038.Search in Google Scholar

Casadei, Federica. 2024. La costruzione fraseologica italiana [a tutto/a N]. In Federica Casadei & Sabine Kösters Gensini (eds.), I fraseologismi schematici. Questioni descrittive e teoriche, 83–113. Roma: Aracne.Search in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2001. Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: Oxford Academic.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198299554.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fillmore, Charles J., Paul Kay & Mary Catherine O’Connor. 1998. Regularity and idiomaticity in grammatical constructions: The case of “let alone”. Language 64(3). 501–538. https://doi.org/10.2307/414531.Search in Google Scholar

Gaatone, David. 2008. Un ensemble hétéroclite: les adverbes de degré en français. In Jacques Durand, Benoit Habert & Bernard Laks (eds.), Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française – CMLF’08. Paris: Institut de Linguistique Française.10.1051/cmlf08125Search in Google Scholar

Ghesquière, Lobke. 2017. Intensification and focusing. The case of pure(ly) and mere(ly). In Maria Napoli & Miriam Ravetto (eds.), Exploring intensification: Synchronic, diachronic and cross-linguistic perspectives, 33–54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.189.03gheSearch in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hadermann, Pascal, Michel Pierrard & Dan van Raemdonck (eds.). 2010. La Scalarité. Paris: Larousse.Search in Google Scholar

Hilpert, Martin. 2013. Constructional change in English: Developments in allomorphy, word formation, and syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139004206Search in Google Scholar

Hilpert, Martin. 2014. Construction grammar and its application to English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kilgarriff, Adam, Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý & Vít Suchomel. 2014. The sketch engine: Ten years on. Lexicography 1(1). 7–36.10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9Search in Google Scholar

Micheli, M. Silvia. forthcoming. Evaluative morphology. In Adam Ledgeway & Martin Maiden (eds.), The Oxford handbook of Italian language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Napoli, Maria & Miriam Ravetto (eds.). 2017. Exploring intensification. Synchronic, diachronic and cross-linguistic perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.189Search in Google Scholar

Piunno, Valentina. 2015. Sintagmi Preposizionali come Costruzioni Aggettivali. Studi e Saggi Linguistici LIII(1). 65–98.Search in Google Scholar

Piunno, Valentina. 2018. Sintagmi preposizionali con funzione aggettivale e avverbiale. München: LINCOM Studies in Romance Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Piunno, Valentina. 2021. Coordinated constructional intensifiers: Patterns, function and productivity. In Carmen Mellado Blanco (ed.), Productive patterns in phraseology and construction grammar. A multilingual approach, 133–163. Berlin & Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110520569-006Search in Google Scholar

Piunno, Valentina. 2023. Intensifying constructions in Italian. Types, function and representation. In Jean-Pierre Colson (eds.), Phraseology, constructions and translation. Corpus-based, computational and cultural aspects, 399–408. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain.Search in Google Scholar

Rainer, Franz. 2015. Intensification. In Peter O. Müller, Ingeborg Ohnheiser, Susan Olsen & Franz Rainer (eds.), Word-formation: An international handbook of the languages of Europe, 1339–1351. Berlin & Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Rapatel, Philippe. 2015. De la délexicalisation/grammaticalisation à l’intensification. Hal archives-ouvertes.fr. 1–13. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01066454/document (accessed 11 February 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Simone, Raffaele & Valentina Piunno. 2017. Combinazioni di parole che costituiscono entrata. Rappresentazione lessicografica e aspetti lessicologici. Studi e Saggi Linguistici LV(2). 13–44.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.