Abstract

In the context of globalization and university internationalization, sustainability can serve as both a pedagogical goal and course content that connects English language education with other disciplines. This study reports an initiative integrating the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into an English for Global Citizenship (EGC) curriculum at an international liberal arts faculty in a private university in Tokyo. Drawing on the theoretical framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), the course design operationalized CLIL’s four dimensions—content, communication, cognition, and community—through six global issue modules. Using a repeated cross-sectional survey design, longitudinal student feedback collected across nine administrations from 1083 respondents was reanalyzed. Learners consistently valued SDG integration, reported perceived gains particularly in presentation, listening, and writing as well as in increased motivation and awareness of global issues, while also expressing a continuing need to strengthen speaking. Findings suggest that incorporating SDGs into university-level English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses can foster learner engagement and autonomy and contribute to sustainable, well-coordinated curriculum management. The study concludes by highlighting the importance of systematic program evaluation and stronger articulation between English and related content courses to enhance the long-term sustainability of language programs.

抄録

グローバル化と大学の国際化が進む中で、「持続可能性」は英語教育を他分野とつなぐ教育目標であり、学習内容としても機能し得る。本研究は、東京都内の私立大学国際教養学部におけるEnglish for Global Citizenship(EGC)カリキュラムに、国連の持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)を統合した実践を報告する。持続可能な開発のための教育(ESD)および内容言語統合型学習(CLIL)の理論に基づき、CLILの4つの側面(内容・コミュニケーション・認知・共同体)を6つの地球規模課題モジュールを通して実践した。2016〜2023年度に実施した9回の質問紙調査に基づく1083名の学生フィードバックを再分析した結果、学生の多くはEGCカリキュラムへのSDGsの統合を肯定的に捉え、特にプレゼンテーション・リスニング・ライティング能力の向上、および学習意欲やグローバル課題への意識の高まりを実感すると回答した一方で、スピーキング能力強化への継続的なニーズも示された。SDGsを大学のアカデミック英語教育に取り入れることは、学習者による主体的な学びを高め、プログラム全体の円滑なカリキュラム運営に寄与する可能性が示唆された。最後に、言語プログラムの体系的プログラム評価と、英語科目および関連科目間の連携強化の必要性を指摘し、言語プログラムの持続可能性を高めるための方向性を論じる。

Résumé

Dans un contexte de mondialisation et d’internationalisation des universités, la durabilité peut à la fois être un objectif pédagogique et un contenu reliant l’enseignement de l’anglais à d’autres disciplines. Dans cette étude détaillant une initiative pédagogique réalisée dans une faculté d’Arts libéraux internationaux d’une université privée de Tokyo, nous expliquons comment les Objectifs de développement durable (ODD) des Nations Unies ont été intégrés au programme d’anglais pour la citoyenneté mondiale. Coordinatrice du programme, l’auteure s’est appuyée sur les travaux en éducation au développement durable (EDD) et sur l’enseignement des matières par l’intégration d’une langue étrangère (EMILE/CLIL) pour la conception des cours et cet article décrit comment, en conformité avec les exigences du CLIL, les ODD ont été incorporés à des modules d’anglais portant sur les enjeux internationaux. L’analyse des données tirées de neuf enquêtes réalisées entre 2016 et 2023 auprès de 1083 étudiants montrent que les apprenants ont apprécié l’inclusion des ODD aux cours et perçu des améliorations dans les quatre champs du CLIL (contenu, communication, cognition, communauté). Ils ont notamment indiqué avoir vu progresser leurs compétences linguistiques, leur motivation ainsi que leur sensibilité aux enjeux internationaux. L’étude met en évidence l’intérêt d’intégrer les ODD aux cours d’anglais académique puis conclut sur la nécessité d’évaluations systématiques et de futurs développements curriculaires afin de renforcer la durabilité de ce type de programmes.

1 Introduction

Sustainability is a shared goal in the globalized society, while people seek wellness and well-being at individual levels. In response to social needs, Japanese universities have increasingly offered courses on sustainability that feature the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While 344 universities in Japan have departments with “international” in their names, 16 offer undergraduate degrees in “international liberal arts” (Knowledge Station 2024). Liberal arts education as defined by American Association of Colleges and Universities (2024) is “an undergraduate education that promotes integration of learning across the curriculum and co-curriculum, and between academic and experiential learning, in order to develop specific learning outcomes that are essential for work, citizenship, and life.” Locating the liberal arts in an international context, many of the liberal arts departments in Japan identify their role as providing interdisciplinary perspectives to address global issues that require critical thinking and collaboration beyond a discipline. In such a context, the sustainability or the SDGs serve as a bridge connecting different fields to examine global issues from diverse perspectives.

Among these institutions is Juntendo University, a private university in Tokyo. It is known for its medical school established in 1838 and it identifies itself as a health-promoting university with the philosophy of jin (“benevolence”), emphasizing care, empathy, and social responsibility. As of 2025, it has nine departments including medicine, sports science, nursing, physical therapy and radiological technology, clinical examination, health data science, and pharmacy. The Faculty of International Liberal Arts (FILA), was established in 2015 as the first social science and humanities department that embodies the philosophy of jin by combining health and well-being perspectives with intercultural and sustainability-oriented education. Students take intensive English courses as well as a variety of foundational courses and the second foreign language courses (French, Spanish, or Chinese) during the first two years of their undergraduate program. In the third and fourth years, students choose among three disciplines: Global Health Services, Global Society, and Intercultural Communication.

English for Global Citizenship (EGC), a mandatory second-year English program, plays a central role in linking language learning with the exploration of global issues. Designed with a CLIL-based linguacultural approach, EGC engages students in English-medium discussion and critical reflection on issues such as peace, gender, poverty, and climate change collaboratively. The author, serving as the course coordinator of between 2015 and 2023, administered a survey to explore students’ needs, to evaluate students’ attitudes and perceptions of the program, to assess the effectiveness of the course, and to make necessary revisions for further course development each year. Analyzing longitudinal surveys, this article reflects on how the EGC course has evolved and explore how students have perceived the value of the curriculum, particularly after SDGs integration in 2018. This study ultimately considers how English language education can foster sustainability not only as course content but as a pedagogical practice within international liberal arts education.

2 Literature review

2.1 Education for Sustainable Development: Global and Japanese perspectives

The United Nations (2024a) adopted the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” in 2015 with 17 development goals, known as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). UNESCO established Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to address urgent environmental issues, including global warming, within existing school subjects. Rieckmann et al. (2017) examined how ESD functions under UNESCO to promote the achievement of the SDGs through government policies, curriculum, materials development, teacher training, and individual teachers’ classroom practices. They highlighted the importance of assessing students’ learning outcomes and effects of the program to provide quality education sustainably and effectively.

Empirical research has also supported the positive educational impact of ESD. Olsson et al. (2022), for example, demonstrated through a longitudinal study with Swedish upper secondary students that ESD can enhance students’ action competence for sustainability, though sustained engagement is needed to develop learners’ confidence in enacting change. The benefits of ESD have also been highlighted in terms of learners’ internal development such as motivation and self-exploration in addition to acquiring and developing knowledge in course content (e. g., Araneo 2024). Further to this, O’Flaherty and Liddy (2017) reviewed 44 studies on development education, ESD, and global citizenship education and reported that ESD interventions enhance learners’ sustainability awareness, values, and competencies. The studies suggest that ESD not only fosters cognitive understanding but also promotes transformative, behavior-oriented learning outcomes, that are essential for sustainable societies.

ESD has gathered attention further in Japan especially after the adoption of the SDGs and various initiatives in the public and private sectors (e. g., Tanaka 2017). Under the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japanese National Commission for UNESCO (2016) published guidelines for conducting ESD and encouraged schools from the elementary to high school levels to offer classes and organize events on global issues and SDGs. The Japanese Society of ESD was established in 2017 and it started offering regular meetings where teachers and researchers share ideas for ESD practices at schools via different kinds of content courses such as science, social studies, and language courses at various school levels. Beyond public schools, many educational organizations, for instance, Global Incubation and Fostering Talents (GiFT) General Incorporated Association (2018), provide sustainability-themed programs and workshops. Today, the SDGs are considered relevant to students at all school levels. As the SDGs have become widely visible in Japanese society, many students enter higher education with prior exposure to sustainability themes, making university education an area for deeper, critical engagement with these global goals.

2.2 English language teaching and sustainability

A common route integrates sustainability through content-focused English language teaching. The compatibility of the content-focused language instruction and ESD has been widely discussed, particularly in Europe, where researchers have explored how teachers and students perceive sustainability in English language education and how sustainability can be effectively embedded in classroom practices.

Much of the existing research on sustainability in language education has focused on perceptions, shedding light on how teachers and learners conceptually link sustainability with language learning. Arslan and Curle (2024), for example, explored teacher’s perceptions of integrating ESD and the SDGs in foreign language teaching in Turkey. Many of the teachers surveyed regarded sustainability as an important pedagogical theme, associating it with lifelong learning and English as a lingua franca. Similarly, Kuusalu et al. (2024) conducted a questionnaire study with Finnish university students majoring in languages and found that they perceived social and cultural dimensions of sustainability as most relevant to language teaching, while the economic dimension received less clarity.

Beyond language classrooms, sustainability has also become a critical focus in language teacher education. In Spain, Alcantud-Díaz and Lloret-Catalá (2023) demonstrated how sustainability can be positioned as a core component of EFL teacher training, highlighting the importance of empowering educators as active agents of social change. In wider contexts, Kuusalu et al. (2025) examined pre-service teachers’ reflections on ecological and economic sustainability in Namibia and Finland. Namibian participants tended to associate sustainable development with personal and community engagement, while Finnish participants emphasized material consumption patterns and institutional responsibility. Both groups raised awareness toward the SDGs, underscoring the critical role of teacher education in preparing future educators to promote sustainability across contexts.

While a majority of existing research studied learner and teachers’ perceptions, a few have explored how sustainability is enacted in actual classrooms. Mambu (2022) conducted a classroom-based case study in Indonesia, analyzing SDG-related materials, tasks, teacher prompts, and student interactions in an undergraduate English course. The study found that the materials and tasks stimulated students’ critical engagement and reflection on global issues, illustrating how sustainability themes can serve to develop learners’ critical thinking in English language education.

Theoretically, Maijala et al. (2024) proposed Transformative Language Teaching for Sustainability (TLS) as an approach to integrate ESD into language education as a social change practice. TLS situates learner-centered language teaching within transformative pedagogy to develop competencies such as critical thinking, collaboration, and intercultural awareness. Their framework situates TLS within transformative pedagogy and highlights how learner-centered methods can integrate sustainability themes into language classes. The study also outlined pedagogical implications for content and methods and proposed an interdisciplinary, theory-based model for implementing TLS in both classroom practice and teacher education. Expanding on this theoretical foundation, Maijala, et al. (2025) documented a variety of TLS initiatives. Building on these trends in theorizing and practicing sustainability-oriented language education, the present study seeks to extend this line of inquiry by examining university students’ perceptions of sustainability within English language learning in Japan.

2.3 Sustainability and English language education in Japan

While the integration of sustainability remains relatively new in Japan, the pedagogical foundations for content-focused instruction had already been established in its English as a foreign language (EFL) context through the adoption of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL).[1] Developed under the European plurilingualism, CLIL aims to balance language and content learning through its four interrelated dimensions known as 4Cs (i. e., content, communication, cognition, and culture/community), fosters intercultural awareness, and promotes various types of collaborative learning in both first and additional languages (e. g., Coyle et al. 2010; Lin 2016; Llinares et al. 2012; Mehisto et al. 2008). In Japan, Sasajima (2015) introduced CLIL-based English classes practiced in various educational settings from elementary to university levels in Japan and other Asian countries, often designed collaboratively by language and subject teachers. These initiatives established a basis for integrating sustainability-related content into English education.

The first CLIL-based English curriculum at the university-level in Japan was reported by Watanabe et al. (2011), implemented as part of an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) program, offered to a variety of science and humanity major first year students at a private university in Tokyo. The curriculum consisted of a first-semester course focusing on academic communication skills, followed by content-specific academic English electives (e. g., literature, natural science, anthropology, intercultural communication). Data collected through tests, classroom observations, and student evaluations showed that CLIL fostered both linguistic development and critical engagement with content. Izumi et al. (2012) later reflected on the program’s two-year implementation, analyzed various data gathered from teachers and students, and examined student needs and program challenges. They highlighted the importance of shared pedagogical philosophy among teachers and administrators, leadership, organizational support, and ongoing assessment of information and the data gathered from different parties in sustaining CLIL-based innovation.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, only a few studies have reported practices explicitly connecting ESD and CLIL at university EAP courses in Japan. Jodoin (2020), for example, incorporated ESD into a mandatory English course with undergraduate students majoring in policy studies at a private university in Hyogo. He conducted a survey in his three classes to explore the effect of the program. When results were compared between two student groups before and after the incorporation of ESD, 75 students who attended “ESD best-practice course” outperformed the other 76 students who attended “pre-ESD course” in the previous year in terms of their motivation to learn English, environmental literacy, and positive attitudes toward environmental values, beliefs, and norms. The researcher highlighted that the classroom activities connected to local issues promoted transformative and deeper learning. In this context, embedding SDGs within CLIL-based courses was found effective to promote student-centered instruction to help learners develop skills in problem-solving, critical thinking and knowledge application.

More recently, Cardiff et al. (2023) reported their practice of incorporating SDGs and ESD within three elective English courses at a private university in Chiba. To illustrate how sustainability can be operationalized in language teaching, the authors outlined the course designs including objectives, content structures, and assessments. The three courses respectively focused on (a) key SDG issues and possible solutions, (b) the history and culture of LGBTQ+ studies, and (c) well-being. Reflecting on their implementation, the authors identified three essential factors in teaching SDGs through CLIL-based university English courses: (a) socio-cultural context of students’ everyday lives, (b) curricular flexibility, and (c) instructors’ expertise and personal engagement. Both Jodoin (2020) and Cardiff et al. (2023) demonstrated that integrating sustainability into English education can cultivate critical, locally grounded, and globally aware learners while also highlighting challenges and the need for continuous professional development and institutional support to sustain such practices with further improvement.

These studies illustrate how ESD and the SDGs have gradually integrated into English language teaching in Japan, particularly through CLIL-based EAP courses at the university level. The following section provides a closer look at how sustainability-oriented English education has been implemented and developed in a specific Japanese university context.

2.4 English for Global Citizenship at Faculty of International Liberal Arts

The English language program at FILA consists of the first- and second-year mandatory English courses. The two-year English program was initially designed according to a linguacultural approach (Agar 1994; Díaz 2013) as one type of CLIL. The approach assumes a close relationship between language and culture, encouraging learners to explore diverse perspectives and develop intercultural sensitivity. Shaules (2016), who was also a program designer when the FILA was established, explained the curriculum aimed to provide opportunities for students to encounter visible and hidden aspects of cultures (worldviews, values, communication styles, and ways of thinking); notice the similarities and differences among different cultures; and cultivate tolerance and multiple perspectives. With this principle, the first-year English course, originally titled Interactive International English (IIE), emphasized intercultural communication through collaborative and output tasks in small class sizes with mixed proficiency levels and backgrounds. Imai (2017) reported that group discussions and essay writing activities enhanced students’ intercultural awareness and understanding of academic conventions. While the structure, materials, instructors and instructional foci of the first-year course have greatly changed in response to the department’s policy change streaming student proficiency, faculty composition and student demographics, the second-year course has retained the curriculum’s original principles including the linguacultural approach and the collaborative learning in small-sized classes up to date.

The English for Global Citizenship (EGC) course for second-year students was designed to help learners become globally minded individuals who take autonomous actions, play an active role in the international community, and collaborate with others to solve global issues facing Japan and the world using their own specialties. Adopting a CLIL approach, the course is structured around six thematic global issue modules (see Table 1 to be presented later). As an instructional goal, the first semester modules assist students in localizing contemporary global issues to the self and Japan, while the second semester modules help students understand the effects of globalization on their lives, and identify ways to contribute to the world from Japan. The modules were designed to be interrelated, encouraging recursive reflection across topics. The course also plays an important role as a liaison to content courses in three disciplinary tracks in later years.

Instruction is conducted through in-house module booklets combining authentic newspaper articles, documentaries, and adapted sources (see online Attachment 1). The booklets were created by teachers for the first few cohorts and have later been updated regularly in response to events in Japan and the world. In designing booklets, efforts have been made to include materials representing various English types and their backgrounds. Students engage in reading, discussions, and writing tasks (e. g., summaries, opinions, cause-and-effect and problem-solution essays), and oral tasks (presentations, debates, group projects). Students’ performance is assessed according to their accomplishment of the module assignments to achieve the content and language goals outlined on the front page of each module booklet. These goals were set by analyzing student needs and discussing evaluation criteria for major assignments among teachers (Imai 2023). Throughout the year, students pursue individual research projects on global issues of their choice, keeping annotated bibliographies and preparing for the department-wide year-end poster presentations.

As the learning goal of each semester, the EGC course also features two joint events each year: a writing contest in July, in which students collaboratively write petition letters addressing global issues, and a poster presentation showcase in January, where students share their action plans with peers, faculty, and guests from the university community. These events foster motivation, peer modeling, and public engagement. Grades and credits are awarded based on attendance and participation, completion of the module learning program, final products for each semester and additional small activities and progress on autonomous learning. The course also includes online extensive reading, timed writing, vocabulary study, and brief in-class skill activities, with individual counseling held twice every semester.

Each cohort consists of approximately 240 students, divided into 20 class sections of 10 to 12 learners according to English proficiency levels, as measured by the TOEFL ITP scores from December of the previous year. The students spend most of the class time within the department at EGC, meeting four times a week to earn four credits per semester, usually forming a learning community within the department. The unified curriculum ensures consistency across sections while allowing flexibility for each proficiency level and learner group. Each class is co-taught by a pair of instructors—one L1 English-speaking (non-Japanese) and one L2 English (Japanese-speaking)[2]—who collaborate through regular meetings and shared assessment standards. In addition, teachers coordinate to conduct course orientations each semester and administer content quizzes during joint classes.

In response to growing social awareness of sustainability including the trend of ESD in junior and senior high schools and popularity of the SDGs in the business sector, the author initiated the integration of the SDGs into the EGC curriculum in 2018. The six modules were refined and explicitly aligned with relevant SDGs (see Table 1). Each module booklet presented the associated goals at the beginning, started with discussion questions on those goals, and statistical data from official UN sources (e. g., United Nations, 2024 b; United Nations Statistics Division, 2024), and included research, presentation, and writing tasks related to the selected SDGs.

Themes of English Global Citizenship modules and the related SDGs by numbers

| Module | SDGs | |

| First semester(April – July) | 1. Peace and Conflict 2. Gender Inequality 3. Poverty |

16, 17 4, 5, 10 1, 2, 3, 6 |

| Second semester(October – January) | 1. Climate Change 2. Culinary Traditions and Wellness 3. Inbound Tourism |

7, 12, 13, 14, 15 2, 12, 13, 14 8, 9, 11 |

Joint learning sessions were also implemented to strengthen students’ foundational understanding of the SDGs. In 2018 and 2019, the author, as the lead instructor, offered several joint classes for all cohorts, where students listened to a short lecture and exchanged ideas in groups. Finally, each class section presented the learning outcomes to the audience from the other sections. By academic year 2020, students were better informed about the SDGs through the department’s first-year basic seminars taught in Japanese prior to the EGC. In subsequent years, collaboration expanded to include special lectures with guest speakers with professional or academic expertise in sustainability and events such as the annual Refugee Film Festival sponsored by the UNHCR Japan Office.

Further to these, the poster showcase became explicitly connected to the SDGs in 2018. Students now identify relevant SDG logos and explain how their proposed actions contribute to achieving the goals. From 2019, each year’s showcase started to be unified under an umbrella theme (Table 2). While early student projects focused on general awareness activities (e. g., donations, social media campaigns), recent guidance encourages concrete, locally feasible initiatives at community level. Having an audience from the entire department is expected to motivate students in their presentations, which is one of the milestones in their undergraduate studies.

Common themes for poster showcase 2019–2023

| Academic Year | Poster Themes |

| 2019 | What can we do for sustainable 2023? |

| 2020 | Sustainability and the new normal |

| 2021 | Sustainability: Resilience and adaption |

| 2022 | Restoring trust for a sustainable future |

| 2023 | Forward looking actions for a sustainable society |

More recently, the integration of sustainability has extended across department beyond the EGC course. The EGC curriculum is regularly presented at faculty development meetings, and module booklets are shared among instructors of related courses in three disciplinary tracks. Each semester’s orientation provides students with a list of classes that students can take either concurrently with or after the EGC in relation to each module theme. This alignment fosters coherence across the liberal arts curriculum. In 2023, the author launched new field study programs titled “Global English in Action” in Cebu, the Philippines, in every September, and in Hawaii, the United States, in every March. The programs provide experiential learning opportunities on global issues and create chances to use English as a global language. These tours involved interacting with local communities and students, and conducting their project work. These field studies aimed to connect classroom learning with real-world application through English as a global language.

The EGC course thus represents a longitudinal example of how CLIL-based English education can integrate sustainability themes in a Japanese university context. Over nearly a decade, the curriculum has evolved to connect language learning with intercultural competence, critical thinking, and the SDGs. Building upon these developments, the present study analyzes survey data collected between 2016 and 2023 in the program to examine how students have perceived the course and its educational value in fostering global citizenship and sustainability awareness.

2.5 Research questions

Building upon the literature reviewed above, this study examines how sustainability-oriented English teaching is implemented and perceived in a Japanese university context. Previous studies have examined the theoretical frameworks of ESD and CLIL (e. g., Maijala et al. 2024) and reported individual classroom practices (e. g., Cardiff et al. 2023; Jodoin 2020; Mambu 2022). This article has reflected on how the English for Global Citizenship (EGC) course was initially designed at Juntendo University’s Faculty of International Liberal Arts (FILA) as a CLIL-based English course and how the course has incorporated the SDGs into its content since 2018. As far as is known, however, the incorporation of SDGs into CLIL-based English courses has not been examined in an EAP context within a specific department under a unified curriculum over an extended period longitudinally.

To address this gap, this study now focuses on how international liberal arts majors have perceived the effectiveness of the EGC and responded to the implementation of the SDGs. By analyzing students’ survey data collected over multiple academic years, this study seeks to identify trends in learner perceptions, strengths of the course, potential areas for further improvements and implications for sustainable curriculum development in English language education. Accordingly, the following research questions were addressed:

How do university students majoring in international liberal arts perceive the value of their learning program in English for Global Citizenship?

What areas of improvement are informed by the learners’ feedback on the course?

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design and participants

This study is a longitudinal descriptive study, adopting a repeated cross-sectional survey design to investigate students’ attitudes towards the English for Global Citizenship (EGC) curriculum across eight academic years at the Faculty of International Liberal Arts (FILA) at Juntendo University. Each year, a different cohort of second-year students participated in the survey. Data were collected from 2016 to 2018 (twice each year) and 2021 to 2023 (once each year) as summarized in Table 3.[3] Across nine administrations, 1,083 students responded, representing perspectives from the majority of the second-year cohort each year.

Student enrollment and response

| Academic Year and Semester |

Enrollment

(n) |

Response

(n) |

Return Rate

(%) |

| 2016 first | 124 | 92 | 74.2 |

| 2016 second | 116 | 81 | 69.8 |

| 2017 first | 122 | 91 | 74.6 |

| 2017 second | 120 | 93 | 77.5 |

| 2018 first | 120 | 93 | 77.5 |

| 2018 second | 114 | 91 | 87.7 |

| 2021 second | 241 | 218 | 90.4 |

| 2022 second | 206 | 184 | 89.3 |

| 2023 second | 209 | 140 | 66.9 |

| TOTAL | 1372 | 1083 | 78.9 |

The participants represented a diverse range of English proficiency levels. The university mandates all first-year students across all departments to take the Test of English as a Foreign Language Institutional Testing Program (TOEFL ITP) twice each academic year to ensure consistency in language education standards. The average scores among FILA’s first- and second-year students typically range between 440 and 460, with individual scores spanning from approximately 380 to 670. Students are encouraged to achieve a score of 480 or higher to demonstrate their readiness for advanced studies or global job market. The program and its curriculum design align with Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001, 2020) targets–-C1 English and B1 French, Spanish, or Chinese–-upon the graduation.[4]

3.2 Instrument

The survey was designed to ask students to reflect on their learning experiences in the EGC (e. g., content, language learning activities, assignments, language learning motivation, events, class format, peer collaboration, teacher support, relevance to other classes, and autonomous learning opportunities) and self-evaluate their efforts. The survey consisted of a Likert-scale items section measuring learner attitudes and an open-ended response section to explore their supplementary insights. The first section involved 30–40 sentence items, depending on the year. Students expressed their opinions and levels of agreement, which were evaluated on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: agree, and 4: strongly agree). Approximately half of the sentence items have been retained since the first administration in 2016 to explore any potential changes in learner perception over the years. Thus, the present paper focuses on reporting the cross-year comparisons of responses to these consistently retained items. The second section included several open-ended questions for students to highlight the strengths of the program and to express need for further improvement. Only the responses to the Likert-scale items section are reported in this paper, while the open-ended responses were qualitatively coded to provide supplementary insights.

3.3 Procedure and data analysis

The data were gathered annually and primarily used to self-monitor the course and update it in response to inputs from students before starting a new academic year[5] and were re-analyzed for the purpose of this study. The survey was administered on a semester basis from 2016 to 2018 during both the first and second semesters through an online survey tool. In recent years, the survey administration was reduced from twice an academic year to once, and the survey are distributed online on the last day of the academic year in January from 2021. Responding to the survey was anonymous and voluntary, but since the survey was introduced as part of class time, the program achieved a high return rate (M=78.9 %). Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data, using Microsoft Excel, and year-to-year changes were illustrated visually through figures. This approach allowed for the comparison of group-level trends in students’ attitudes over time.

4 Findings

Learner perception of the value of their English learning program at the EGC is reported according to the four Cs of CLIL (content, communication, cognition, and community), followed by their assessment of the effect of the program on their language learning motivation, confidence, and relevance to other courses.

4.1 Content

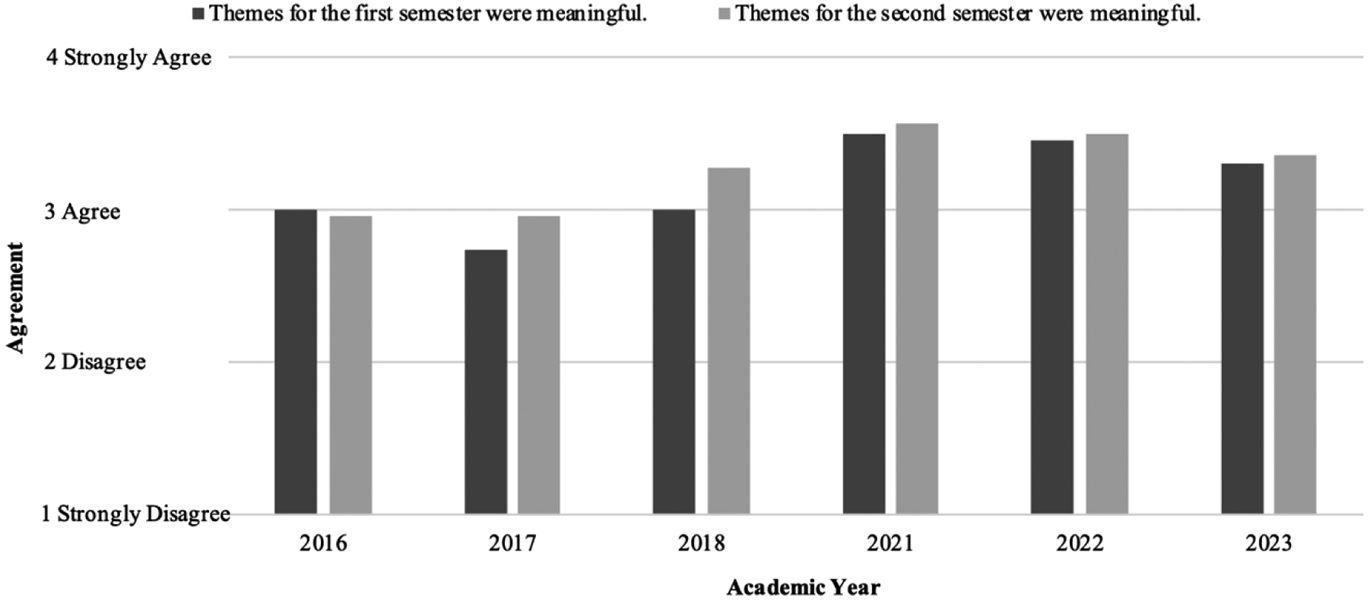

The survey asked students whether they considered each semester’s module themes and booklets meaningful. Table 4 summarizes learner attitudes toward the course content and module booklets. Throughout these years, the learners were quite positive about global issues as the course content and the in-house materials. The mean exceeded three (agree) in the second semester of 2017 and in the first semester of 2018, and their attitudes became more positive between 2018 to 2013.

Learner attitudes toward course contents and materials

| Academic Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

| Semester | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Student (n) | 92 | 81 | 91 | 93 | 93 | 91 | 218 | 184 | 140 | |

| Semester 1 Contents 1 | M | 2.99 | n/a | 2.74 | n/a | 3.00 | – | 3.50 | 3.46 | 3.30 |

| SD | 0.65 | – | 0.85 | – | 0.69 | – | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.70 | |

|

Semester 2

Contents 2 |

M | n/a | 2.95 | n/a | 3.03 | n/a | 3.27 | 3.56 | 3.49 | 3.36 |

| SD | – | 0.69 | – | 0.7 | – | 0.73 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.68 | |

| Module Booklets3 | M | 2.82 | 2.89 | 2.67 | 2.86 | 2.83 | 2.91 | 3.33 | 3.32 | 3.10 |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.71 | |

Notes: Statements presented in the survey were 1: “Themes for the first semester were meaningful”; 2: “Themes for the second semester were meaningful”; 3: “Original module booklets were useful.”

As illustrated in Figure 1, the mean remained similar, slightly below three between 2016 and 2017, but their attitudes clearly exceeded three (agree) in 2021 to 2023. Although the present study excludes the survey from 2019 and 2020, it seems that the SDGs quickly became popular among people in general under the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicate that the implementation of SDGs in global-issue modules in 2018 has been positively recognized by a majority of the students. In particular, the scores in 2021 and 2022 may reflect the maturity of material development, as only minimum revisions were made. The slight decline in 2023 indicates the need for further updating the reading and audio/video materials.

Learner attitudes toward course contents for academic years 2016–2023.

In 2022 to 2023, the survey asked students about their level of accomplishment in understanding global issues. Quite many students (92.9 % in 2022, 90.7 % in 2023) indicated that they achieved most of the content and language goals presented in each module booklet by choosing either “4: strongly agree” or “3: agree.” A similar degree of agreement was reported from 2021 to 2023 regarding their indepth understanding of global issues in Japan and the world (98.2 % in 2021, 98.3 % in 2022, and 95.7 % in 2023) and the availability of learning opportunities on global issues (94.5 % in 2021, 96.7 % in 2022, and 91.4 % in 2023).

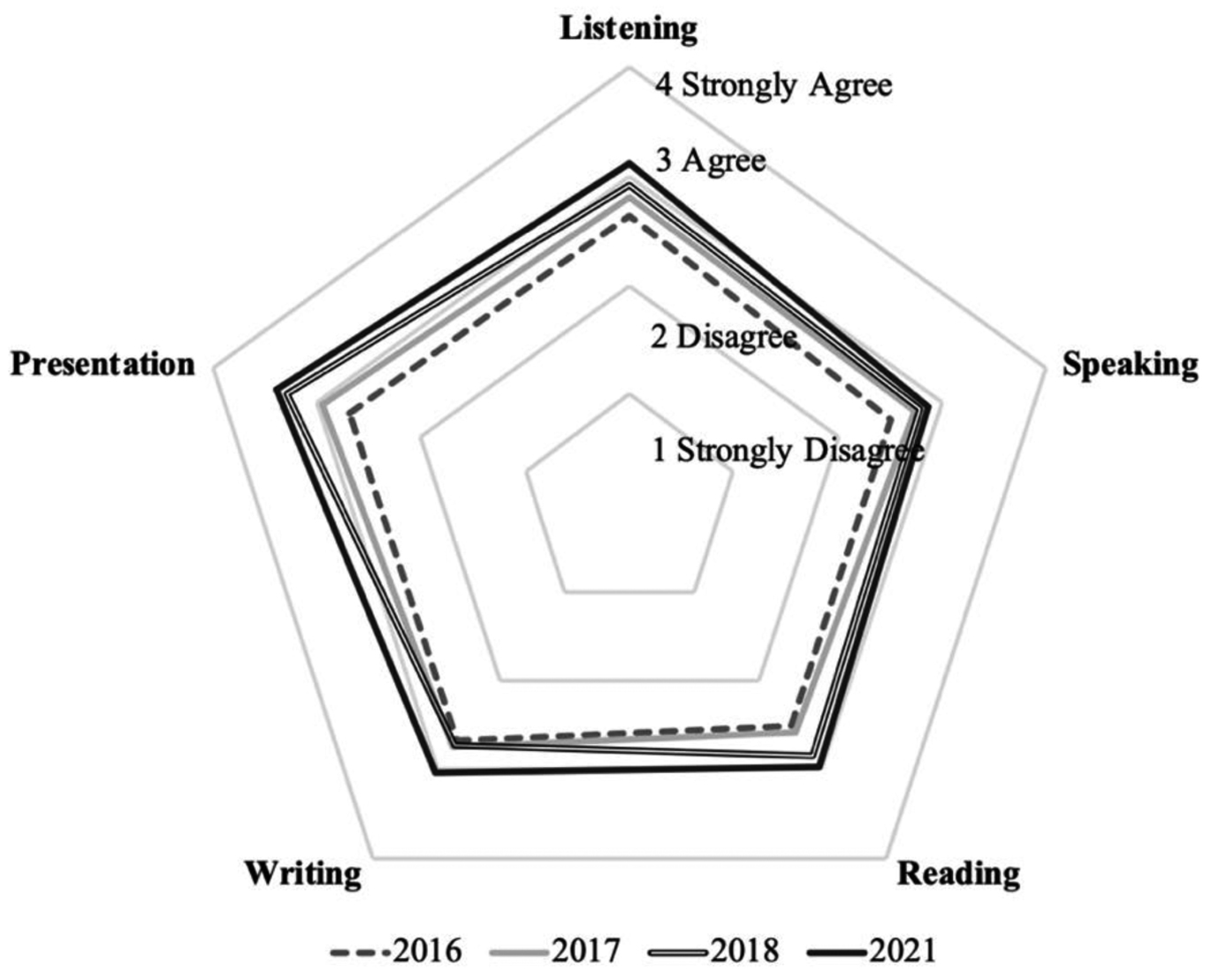

4.2 Communication

Five of the survey items asked students whether they felt that their language skills required for communication (i. e., listening, speaking, reading, writing, and presentation) had improved. Table 5 summarizes learners’ assessment of their own communication skills from 2016 to 2021. Between 2016 and 2018, learners reported steady self-assessments of all five communicative skills. In particular, their self-assessment exceeded three (agree) for presentation skills in 2018, and for listening and writing skills in 2021. As illustrated in Figure 2, students believed that the EGC has the most positive impact on their presentation skills, while their perception of other skills remained similar over the six years.

Learners’ self-assessment of five communicative skills

| Survey Items on Language Skills | Academic Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2021 | |

| Student (n) | 81 | 93 | 91 | 218 | ||

| 1 | I feel my listening skills have improved. | M | 2.64 | 2.81 | 2.92 | 3.12 |

| SD | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.64 | ||

| 2 | I feel my speaking skills have improved. | M | 2.51 | 2.74 | 2.79 | 2.87 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.70 | ||

| 3 | I feel my reading skills have improved. | M | 2.51 | 2.57 | 2.84 | 2.96 |

| SD | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.64 | ||

| 4 | I feel my writing skills have improved. | M | 2.67 | 2.74 | 2.73 | 3.03 |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.65 | ||

| 5 | I feel my presentation skills have improved. | M | 2.69 | 2.95 | 3.29 | 3.39 |

| SD | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.64 | ||

Learners’ self-asessment of five communicative skills.

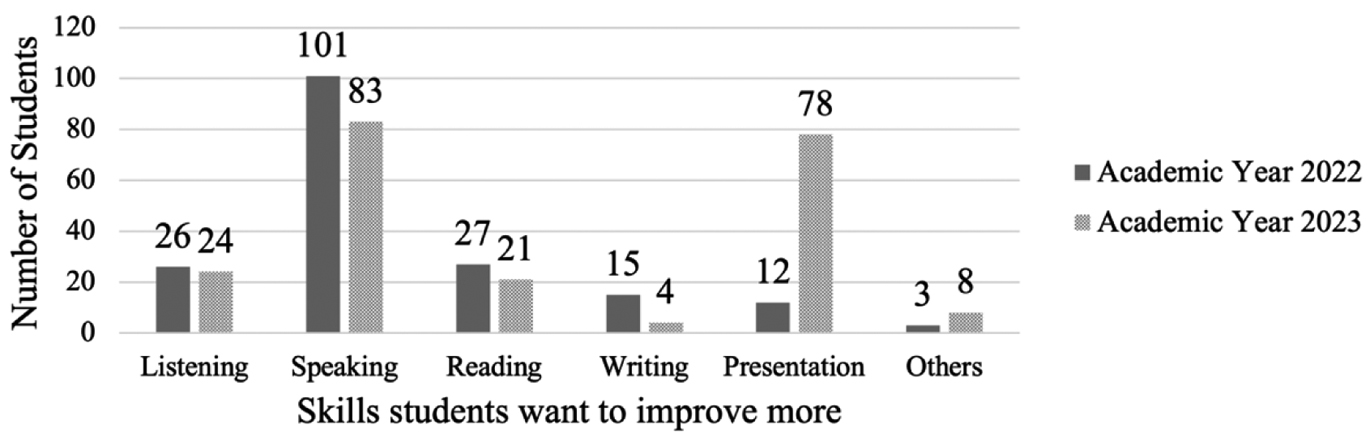

In 2022 and 2023, the survey asked students to report the type of English skills they want to improve. As illustrated in Figure 3, a majority (184 students in total) chose speaking skills; this result corresponds with the higher degree of disagreement with the item asking whether they felt they had improved their speaking skills. In addition to speaking skills, 90 students reported that they want to improve their presentation skills. The response numbers dropped to 50 students for listening and 48 for reading skills. The relatively high demand for presentation skills and some needs for listening and reading skills may be attributed to the inclusion of diverse listening and reading passages on global issues and sustainability, as well as presentation assignments, usually connected to the SDGs, required students to conduct bibliographic research and prepare poster presentations for an extended period. Only 19 students over two years expressed their wish to improve their writing skills. These results imply students’ need and preference to improve their speaking skills, while they placed less importance on writing skills.

Learners’ choice of communication skills to improve.

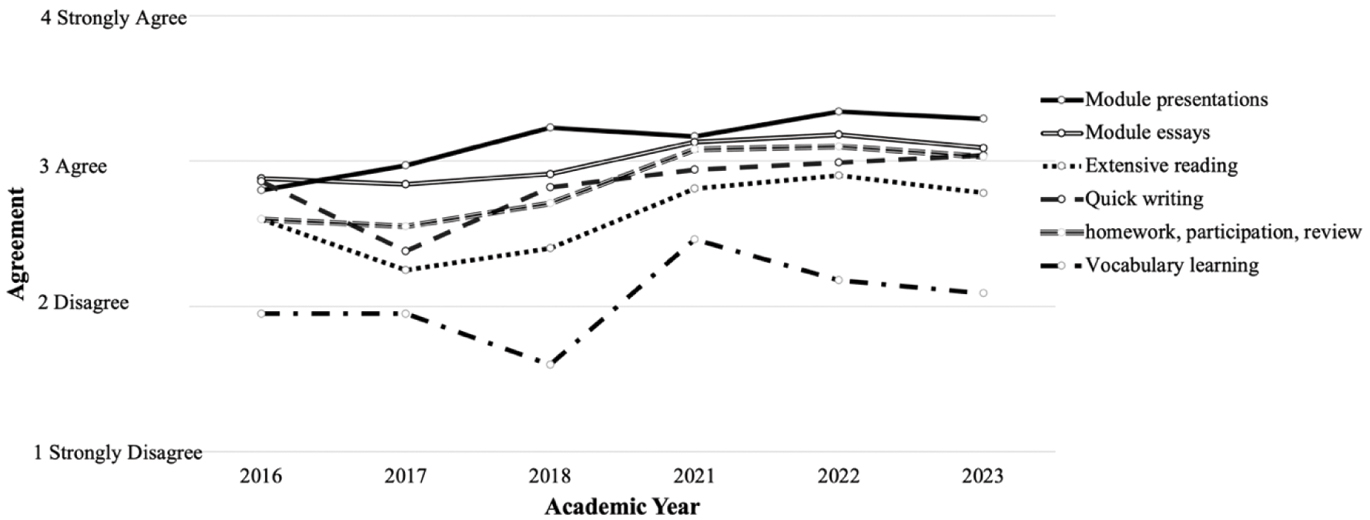

4.3 Cognition

A variety of module assignments, activities, and tasks attempt to help students develop cognitive skills; students are also encouraged to work on vocabulary, extensive reading, and test preparation. Table 6 summarizes learners’ attitudes toward module and autonomous learning activities. As shown in the table, students evaluated presentation and writing assignments for each module positively, and their attitudes improved further between 2018 and 2023. This improvement may reflect the arrangement of activities and tasks following consistent patterns within the booklets and major assignments were decreased in number and sequenced so that students could experience various text and presentation genres from simple to more complex tasks. Earlier, students were required to work on both writing and presentation assignments to consolidate each module, but since 2018, students have been assigned to work on either essay writing or presentations for each module. The module booklets began introducing more input tasks rather than output tasks. These changes also reflect the department's minor curriculum revisions in 2019 which reduced the number of EGC credits from eight to four per semester.

Learners’ attitudes toward module and autonomous learning activities

| Survey Items on Cognitions | Academic Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Student (n) | 81 | 93 | 91 | 218 | 184 | 140 | ||

| 1 | Presentation assignments for each module were meaningful. | M | 2.80 | 2.97 | 3.23 | 3.17 | 3.34 | 3.29 |

| SD | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.68 | ||

| 2 | Writing assignments for each module were meaningful. | M | 2.88 | 2.84 | 2.91 | 3.13 | 3.18 | 3.09 |

| SD | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.72 | ||

| 3 | I worked hard on homework, class preparation, review, and assignments. | M | 2.60 | 2.55 | 2.71 | 3.08 | 3.10 | 3.03 |

| SD | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.78 | ||

| 4 | X-Reading (online extensive reading) was useful. | M | 2.60 | 2.25 | 2.40 | 2.81 | 2.90 | 2.78 |

| SD | 0.91 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.86 | ||

| 5 | Quick writing (timed free writing) was useful. | M | 2.86 | 2.38 | 2.82 | 2.94 | 2.99 | 3.04 |

| SD | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.72 | ||

| 6 | I regularly study English vocabulary using Quizlet and other tools. | M | 1.95 | 1.95 | 1.60 | 2.46 | 2.18 | 2.09 |

| SD | 0.82 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | ||

In regard to autonomous learning tasks, while the mean average generally increased, students’ attitudes were varied. Most of the students were positive about the online extensive reading administered through X-Reading and quick (timed-free) writing tasks, but when they were asked about vocabulary learning, they rather responded negatively. Figure 4 also shows students’ attitudes regarding vocabulary learning, which were always lower than their attitudes toward other tasks throughout the years. The results suggest the need for further improvement of vocabulary learning program and of the extensive reading tasks because individual differences appear in how effectively students engage in vocabulary study and extensive reading. All the mean averages slightly decreased in 2023; this also suggests that the course must explore ways to further develop students’ cognitive skills.

Transition of learner attitude on cognitive tasks 2016–2023.

4.4 Community

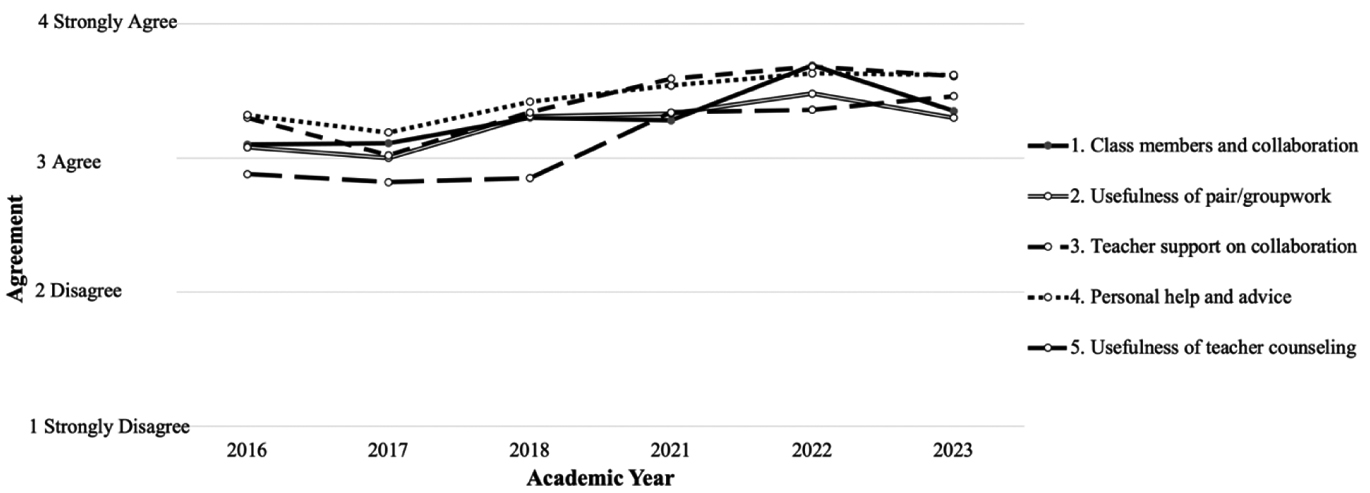

The EGC encourages students to develop their learning community by engaging in a variety of collaboration opportunities, such as working in pairs or small groups. Teachers model such collaboration by teaching together, creating materials, and running joint classes. Thus, the survey asked students about their attitudes toward collaboration and teacher support. As summarized in Table 7 and Figure 5, the students’ attitudes toward class collaboration were always high; in fact, in more recent surveys, students’ attitudes were rated much closer to “4: strongly agree.”

Learners’ attitides toward class collaboration and teacher support

| Survey Items on Community | Academic Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Student (n) | 81 | 93 | 91 | 218 | 184 | 140 | ||

| 1 | Class members were able to collaborate with one another. | M | 3.10 | 3.11 | 3.30 | 3.28 | 3.69 | 3.35 |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.70 | ||

| 2 | Pair work and groupwork were useful for my own learning. | M | 3.08 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 3.33 | 3.48 | 3.30 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.62 | ||

| 3 | Our teachers were trying to create a collaborative atmosphere in the classes. | M | 3.30 | 3.02 | 3.34 | 3.59 | 3.68 | 3.61 |

| SD | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.58 | ||

| 4 | My teachers offered personal help and advice. | M | 3.32 | 3.19 | 3.42 | 3.54 | 3.63 | 3.62 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.56 | ||

| 5 | English learning counseling with my teachers were useful. | M | 2.88 | 2.82 | 2.85 | 3.34 | 3.36 | 3.46 |

| SD | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.69 | ||

Leaner atittudes toward student collaboration and teacher help from 2016 to 2023.

The results also suggest the students felt satisfied with individualized support from their teachers. In regard to the counseling sessions, the students’ attitudes became very positive, particularly after 2021. In early years, the course required students to attend two counseling sessions every semester and they were relatively structured, with worksheets and numerous points to cover. In recent years, teachers were given more flexibility regarding the structure of counseling and while the first counseling is required for all students, the second one is optional, so teachers and students can schedule additional counseling whenever the need arises or when an opportunity comes up.

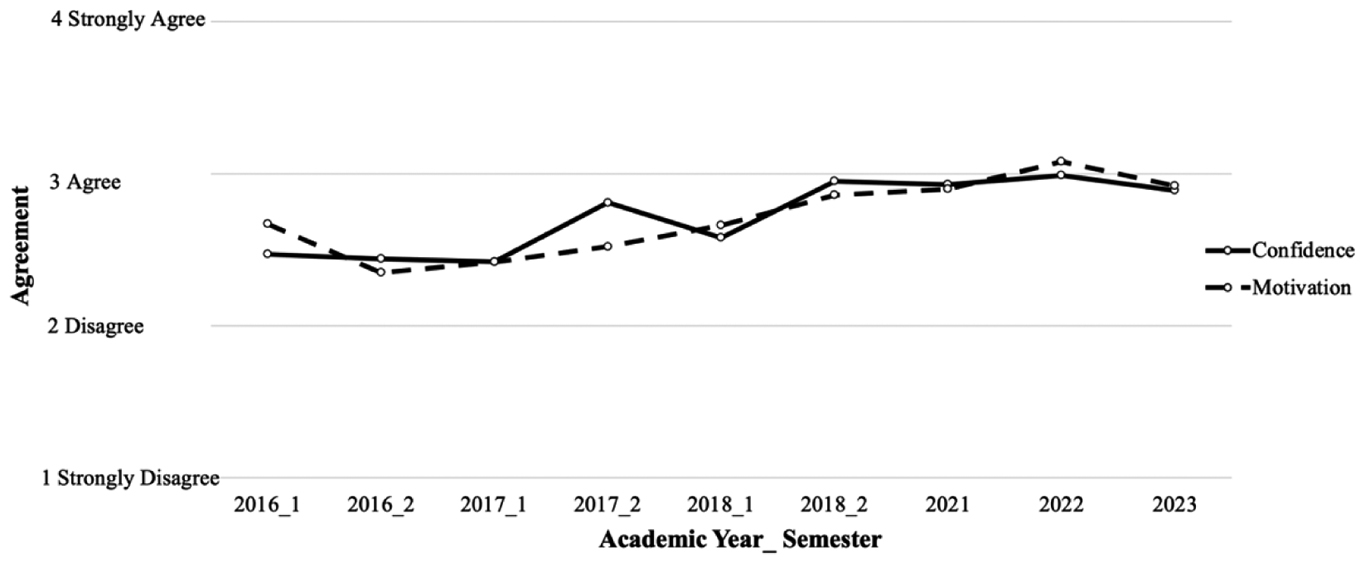

4.5 Learner motivation and relevance to other courses

The survey retained items on language learning motivation and confidence every year. Table 8 reports the mean average of students’ self-report of their motivation and confidence and Figure 6 presents a similar trend in the mean over the period of time. Both confidence and motivation increased slightly throughout the study period. After the EGC included the SDGs, the mean approached “3: agree.” The results indicate the positive influence of the current EGC curriculum on English learning motivation and that students gained confidence, while the slight decrease in 2023 implies the need to further explore ways to motivate learners and help them feel more confident. Positive responses to these items were encouraging for the program.

Learners’ self-report on their confidence and motivation.

| Academic Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

| Semester | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Student (n) | 92 | 81 | 91 | 93 | 93 | 91 | 218 | 184 | 140 | |

| Confidence 1 | M | 2.47 | 2.44 | 2.42 | 2.81 | 2.58 | 2.95 | 2.93 | 2.99 | 2.89 |

| SD | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.78 | |

| Motivation 2 | M | 2.67 | 2.35 | 2.42 | 2.52 | 2.66 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 3.08 | 2.92 |

| SD | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.81 | |

Notes: Statements presented in the survey were 1: “I think I gained confidence in using English.”; 2: “I was able to keep my motivation to learn English.”

Learner perception of English learning motivation (2016–2023).

The EGC was initially designed based on language skills and knowledge development during the first-year English course as a foundation and help students prepare for advanced courses and seminars in their third and fourth years. Recent surveys included two additional items regarding the relevance of EGC to the first-year English, advanced-level content studies, and future careers. As shown in Table 9, most students (87 % or more) in each year agreed that their learning experience in EGC was different from that in their first-year English, which focused on academic skill building and liberal arts content. It appears that students perceived their learning experience in EGC as unique, although further discussion is required on whether greater collaboration between the first- and second-year English courses is necessary and feasible. In terms of course relevance to other content courses, while three-quarters of the students acknowledged the connection to their advanced area studies and future careers, approximately 17 to 29 % did not observe the connection. Since the relevance of the content is expected to help students find meaning in their learning, further initiatives may be necessary to make the purpose of the course and content explicit for enrolling students over each semester.

Learners’ assessment on the English course relevance to others

|

Academic

Year |

Student

(n) |

M

(SD) |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||||

| My learning experience at EGC was different from the first-year English course. | |||||||

| 2021 | 218 | 3.32 (0.72) |

2 (0.9 %) |

26 (11.9 %) |

91 (41.7 %) |

99 (45.4 %) |

|

| 2022 | 184 | 3.48 (0.58) |

0 (0.0 %) |

8 (4.3 %) |

80 (43.5 %) |

96 (52.2 %) |

|

| 2023 | 140 | 3.31 (0.64) |

1 (0.7 %) |

11 (7.9 %) |

72 (51.2 %) |

56 (40.0 %) |

|

| Learning at the EGC is connected to the studies in three areas, seminars, and desired career paths. | |||||||

| 2021 | 218 | 3.01 (0.74) |

6 (2.8 %) |

40 (18.3 %) | 117 (53.7 %) |

55 (25.2 %) |

|

| 2022 | 184 | 3.05 (0.71) |

5 (2.7 %) |

26 (14.1 %) | 107 (58.2 %) |

46 (25.0 %) |

|

| 2023 | 140 | 2.86 (0.810 |

8 (5.7 %) |

33 (23.6 %) | 70 (50.0 %) |

29 (20.7 %) |

|

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Overview of the findings

The EGC, originally designed as a CLIL-based English course within at FILA, has evolved over a decade since its launch in 2016. The program fulfilled the four dimensions of CLIL―content, communication, cognition, and community― and demonstrated continuous development, particularly after incorporating the SDGs into its global issues content. Regular student surveys provided valuable feedback, enabling ongoing refinement of tasks, materials, and course sequencing.

Overall, undergraduate students majoring in international liberal arts perceived the value of their in-house EAP program combining CLIL and ESD at the EGC positively. They generally perceived the content positively, appreciated the inclusion of SDG-related content, acknowledged their improvements in language skills, particularly the focus on presentation skills, and opportunities for collaboration. In terms of community, the course provides students with a collaborative learning environment with individual support from teachers when necessary. Individual counseling sessions appear to be more valued when they conducted flexibly. The results also revealed their needs and areas for improvement, such as enhancing speaking skills over listening, reading, and, supporting autonomous through vocabulary learning and extensive reading. The course effectively helped students maintain their motivation and developed their confidence and cognitive engagement, functioning as a bridge between the first-year English and advanced disciplinary courses and future careers.

5.2 Theoretical and pedagogical implications

By adopting a CLIL approach, the EGC successfully integrated language instruction with globally relevant content aligned with ESD and topics international liberal arts majors are particularly interested in. The learner motivation, confidence, and self-assessment of their language skills demonstrate one aspect of the program’s effectiveness. The learners’ positive attitudes toward the course reflected its alignment with ESD’s transformative aims (O’Flaherty & Liddy, 2017; Olsson et al., 2022) and with the intercultural, critical, and collaborative focus of Transformative Language Teaching for Sustainability (TLS) (Maijala et al., 2024).

The EGC’s course design also resonates with Jodoin’s (2020) and Cardiff et al.’s (2023) findings that embedding sustainability within language education enhanced motivation and awareness of real-world issues. Its interdisciplinary framework, connecting liberal arts and social responsibility, situates English learning as a social practice rather than a purely linguistic endeavor—thus aligning with recent global shifts toward sustainability-oriented pedagogy.

5.3 Learner perceptions and areas for improvement

While the EGC achieved many of its goals, several findings indicate the need for further development. First, one aspect requiring further improvement is the course content beyond the SDGs. Recent students have already been exposed to SDGs everywhere in their daily lives or in lessons prior to university; therefore, the SDGs are not necessarily new to them. Given students’ prior knowledge of the SDGs, the EGC should go beyond introductory awareness, focusing more on analyzing how the SDGs function in society critically; the benefits of achieving the SDGs for companies, government, organizations, and individuals by examining corporate case studies, government policies, and community initiatives; and how business operates along with the SDGs. Along this line, the students can also explore related framework. Concurrently, corporate businesses and industries started appealing to their SDG-related initiatives as part of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities and for publicity. For example, websites of leading Japanese companies like Toyota and Sony, among others, explain how their products and corporate initiatives respond to social needs to achieve various SDGs and include their CSR reports for everyone to access. Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2024) also reported interviews of many food industries, mentioning how their initiatives are relevant to the SDGs. Similarly, an increasing number of businesses are investing in concepts such as environment, society, and governance (ESG) (e. g., Liu and Nemoto 2021; Okimoto and Takaoka 2024). Therefore, an important competence for current university students is building skills to examine SDGs critically and explore related concepts such as CSR and ESG in their process of understanding companies’ profiles. Particularly when the students aim to work in globalized world, such information is an important indicator to proceed with job-hunting activities. The course should also help students analyze how the SDGs are implemented in society more critically and develop the ability to evaluate the extent to which the SDGs have been achieved.

At the same time, the course coordinators and teachers should be aware of cautions against greenwashing or SDGs washing (e. g., Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. 2022; Nishitani 2009; Nishitani et al. 2021). In the area of ESD research, various limitations and challenges have been identified. For example, Nagata (2017) cautioned that ESD could be shallow if the instruction simply introduces SDGs as concepts. Encouraging students to examine both authentic corporate reports (e. g., Toyota, Sony) and critiques against SDG-washing would deepen their critical literacy and prepare them for global contexts.

Moreover, class discussions could explore the approaching 2030 deadline, debating whether it is possible and discussing how it could be possible and why the process is delayed. In addition to covering the SDGs more deeply and critically, six existing global issue modules could be further developed by gathering students’ academic interests in this educational context. In the present study, FILA introduced “a ‘global health’ approach to tracking all global issues” along with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals logos by emphasizing Goal 3: Good health and well-being (Juntendo University 2024a). Thus, each module could explore its relevance to health, medicine, and wellness, representing the uniqueness of the course in a health-promoting university. Associating health aspects with global issues would address the needs and interests of students who choose the Global Health Services for their major and would help others develop health literacy as a necessary skill to survive in a globalized society. Both sustainability and wellness seem to be concepts related to issues and problems shared by all human beings, particularly in this educational context.

5.4 Curriculum coherence and program sustainability

The sustainability of the EGC curriculum depends on its alignment with other components of the faculty’s English, foreign language, and liberal arts contents. Survey data in the present study indicated that few students recognized continuity between the first- and second-year English curricula (2022 and 2023 survey administrations). The first-year English course, originally titled as Interactive International English (IIE) taught intercultural communication as its content, but it shifted its instructional emphasis to skills development and test-taking strategies and preparation for TOEFL ITP in 2017. Fortunately, the EGC has retained the original linguacultural principles which formed the basis of the original first-year English curriculum (Agar 1994; Díaz 2014), and was able to continue developing as a curriculum, but the gap between the two English curricula has long unexamined. Re-establishing this connection—both conceptually and pedagogically—could provide a more coherent two-year language learning trajectory. In particular, some content needs to be effectively coordinated between the two courses, and tasks and assignments could be designed and scheduled sequentially and consistently to build language skills over time.

In addition, stronger articulation between the EGC, other foreign language courses (French, Spanish, Chinese), and content courses would also enhance coherence of learning program within the faculty. Reviving the earlier departmental emphasis on plurilingualism—valuing multiple languages equally—would allow students to use diverse linguistic repertoires to explore global issues across languages and cultures (Kramsch, 1993; Risager, 2007). For instance, while most classes are conducted in English, students may sometimes be encouraged to utilize their knowledge and skills in Japanese, French, Spanish, Chinese, and other foreign languages and compare ideas in various languages, understand issues deeply, and complete tasks efficiently. The department also has a variety of linguistic resources for both World Englishes and foreign languages; thus, plurilingualism should be further put into practice by introducing students to various Englishes and encouraging them to use their knowledge in a variety of languages. Such plurilingual approaches could bridge language, identity, and intercultural understanding in deeper ways.

The EGC could also explore ways to connect global issues content with regular French, Spanish, and Chinese courses and short-term language training programs or field studies overseas. In the current context, some of the global issue content, including the SDGs, are covered in the EGC and are often treated in first-year foundational courses in Japanese. Although the EGC curriculum has been widely introduced in faculty development meetings with module booklets distributed to major content faculty members, the curriculum must make further efforts to be known to all instructors beyond core faculty members within the department. If the EGC reaches out to these instructors, they may have ideas, feedback, and perspectives to enrich the content and materials. By ensuring a strong connection between the language and content courses, students can easily place more value on what they learn in second-year English courses.

From an institutional perspective, maintaining teacher collaboration and shared governance remains crucial for the program’s long-term sustainability. As the number of faculty and class sections has doubled from 10 classes by seven full-time instructors in 2016 to 20 classes by 12 full-time instructors in 2024, coordination challenges have grown. Over the last eight years, most instructors have remained in their positions, collaborated closely, and managed to achieve a shared understanding of the program’s background and educational philosophy. However, the course must continue to develop by welcoming new members and perspectives, even during faculty transitions such as role changes, retirements or turnovers. Building a system for continuous faculty development, peer mentoring among faculty members, the department’s support in managing the entire English program, and shared administrative responsibilities among coordinators will be essential to sustain the curriculum’s quality and coherence. As emphasized in previous reflections on CLIL implementation (Izumi et al. 2012), the program’s purposes and objectives should be further integrated thoroughly and systematically in all rounds of the language program administration. Those include analyzing needs initially and continuously, designing courses and materials, planning teaching methodology, administering internal and external assessment, and evaluating student work.

5.5 Future directions and conclusion

Finally, conducting a curriculum-wide program evaluation would provide systematic evidence to make decisions for further refinement. Evaluation plays an important role for the growth of curriculum in university settings (e. g., Milleret and Silveira 2009). Given that the curriculum stability has already been achieved, the course may be mature enough to identify its value and challenges for further development. Drawing on program evaluation frameworks in higher education (e. g., Norris et al. 2009; Patton and Campbell-Patton 2022), future research could integrate linguistic performance data, classroom observations, and stakeholder interviews to assess the EGC’s broader impact. In the current context, many aspects within the department have changed greatly over the last decade; thus, revisions and modifications may be required to achieve consistency in the learning program within departments and running the language program more effectively.

The EGC course illustrates how a CLIL-based English curriculum can function as a sustainable educational model—linking language learning, global citizenship, and critical engagement with sustainability. As the world approaches 2030, higher education faces the dual challenge of maintaining linguistic and ecological sustainability. This case study has demonstrated that university-level English education can play a crucial role in nurturing globally minded, critically reflective learners who contribute meaningfully to a sustainable future.

Note

This article is part of the Special Issue: “Global Goals for Sustainability in European Language Teaching” (guest editors: Minna Maijala & Salla-Riikka Kuusalu)

Acknowledgements

The author expresses sincere gratitude to all former and current EGC teachers and coordinators for their continued discussions on educational issues and their valuable contributions to curriculum development. Special appreciation is extended to the editors of this special issue for their constructive feedback and insightful input during the development of this paper.

References

Agar, Michael. 1994. Language shock: Understanding the culture of conversation. New York: Perennial. Search in Google Scholar

Alcantud-Díaz, María & Carmen LLoret-Catalá. 2023. Bridging the gap between teacher training and society. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) in English as a foreign language (EFL). Globalisation, Societies and Education. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2283510Search in Google Scholar

American Association of Colleges and Universities. 2024. “Trending topic: What is liberal arts education?” https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/what-is-liberal-education (accessed 21 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Araneo, Phyllis. 2024. Exploring education for sustainable development (ESD) courses in higher education: A multiple case study including what students say they like. Environmental Education Research 4(3). 631–660. 10.1080/13504622.2023.2280438Search in Google Scholar

Arslan, Sezen & Samantha Curle. 2024. Institutionalising English as a foreign language teachers for global sustainability: Perceptions of education for sustainable development in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Research 125. 1–12.10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102353Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Donna M., Marguerite Ann Snow & Marjorite Wesche. 2003. Content-based second language instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. 10.3998/mpub.8754Search in Google Scholar

Brown, James Dean. 1995. The elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. Search in Google Scholar

Cardiff, Philip, Malgorzata Polczynska & Tina Brown. 2023. Higher education curriculum design for sustainable development: Towards a transformative approach. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25(5). 1009–1023. 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2023-0255Search in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. 2001. Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Strasbourg: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. 2020. Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4 (accessed 30 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Coyle, Do, Philip Hood & David Marsh 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Diaz, Adriana Raque. 2013. Developing critical languaculture pedagogies in higher education. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783090365Search in Google Scholar

Global Incubation and Fostering Talents(GiFT)General Incorporated Association. 2018. “Educators’ summit for SDGs 4.7: For fostering global citizenship, November 25, 2018.” https://j-gift.org/educators-summit2018/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Heras-Saizarbitoria, Urbieta Iñaki, Laida & Olivier Boiral. 2022. Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29(2). 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.220210.1002/csr.2202Search in Google Scholar

Imai, Junko. 2017. Teaching writing through Content Language Integrated Learning: Content analysis of student essays and group discussions. Juntendo Journal of Global Studies 2. 80–86. Search in Google Scholar

Imai, Junko. 2023. English for Global Citizenship: Program development through analysis of student feedback. Juntendo Journal of Global Studies 8. 57–70.Search in Google Scholar

Izumi, Shinichi, Makoto Ikeda & Yoshinori Wananabe. 2012. CLIL (Content and language integrated learning) New challenges in foreign language education at Sophia University, Volume 2: Practices and applications. Tokyo: Sophia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Japanese National Commission for UNESCO. 2016. A guide to promoting ESD (Education for Sustainable Development), 1st edn. Ministry of Education, Culture Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.Search in Google Scholar

https://www.mext.go.jp/unesco/004/1405507_00001.htm (accessed 32 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Jodoin, Joshua John. 2020. Promoting language education for sustainable development: A program effects case study in Japanese higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 21(4). 779–798.10.1108/IJSHE-09-2019-0258Search in Google Scholar

Juntendo University. 2024 a. “Faculty of International Liberal Arts.” https://www.juntendo.ac.jp/academics/faculty/ila/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Juntendo University. 2024 b. “Faculty introduction: Undergraduate competency.” https://www.juntendo.ac.jp/academics/faculty/ila/about/competency/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Knowledge Station. 2024 (June 28). “Kokusai kyoyou gakubu (international liberal arts departments).”Search in Google Scholar

https://www.gakkou.net/daigaku/src/?srcmode=fid&fi (accessed 27 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire. 1993. Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kuusalu, Salla-Riikka, Päivi Laine, Minna Maijala, Maarit Mutta & Mareen Patzelt. 2024. University language students’ evaluations of ecological, social, cultural and economic sustainability and their importance in language teaching. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25(9). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-05-2023-0169Search in Google Scholar

Kuusalu, Salla-Riikka, Minna Maijala, Minna Maunumäki, Minna Maunula, & Meameno Aileen Shiweda. (2025). Ecological and economic sustainability in Namibian and Finnish pre-service language teachers’ reflections. In: Harju-Luukkainen, Heidi, Suzanne Garvis, Jonna Kangas, João Marôco, Minna Maunula, Minna Maunumäki (eds.), Generating sustainable futures through teacher education: Globally rethinking higher education. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-3329-6_14Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel. 2016. Language across the curriculum and CLIL in English as an additional language (EAL) context: Theory and practice. Singapore: Springer. 10.1007/978-981-10-1802-2Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Lian, & Naoko Nemoto. 2021. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) evaluation and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Accounting and Finance 21(4). https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JAF/article/view/335 (accessed 12 June 2024.10.33423/jaf.v21i4.4522Search in Google Scholar

Llinares, Ana, Tom Morton & Rachel Whittaker. 2012. The role of language in CLIL. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Long, Michael (ed.). 2005. Second language needs analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Lynch, Brian K. 2010. Language program evaluation: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Maijala, Minna, Salla-Riikka Kuusalu, & Riikka Ullakonoja (eds.) 2025. Towards transformative language teaching for sustainability: From theory to practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.10.1007/978-3-031-85493-4Search in Google Scholar

Maijala, Minna, Niklas Gericke, Salla-Riikka Kuusalu, Leena Maria Heikkola, Maarit Mutta, Katja Mäntylä & Judi Rose. 2024. Conceptualising transformative language teaching for sustainability and why it is needed. Environmental Education Research 30(3). 377–396.Search in Google Scholar

https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2167941 Search in Google Scholar

Mambu, Joseph Ernest. 2022. Embedding Sustainable Development Goals into critical English language teaching and learning. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 20(1). 46–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2022.209986310.1080/15427587.2022.2099863Search in Google Scholar

Mehisto, Peeter, David Marsh & Maria Jesus Frigolas. 2008. Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Oxford: MacMillan.Search in Google Scholar

Milleret, Margo & Agripino Silveira. 2009. The role of evaluation in curriculum development and growth of the UNM Portuguese program. In John M. Norris, John McE Davis, Castle Sicicrope & Yukiko Watanabe (eds.), Toward useful program evaluation in college foreign language education, 57–82. Hawaii: National Foreign Language Resource Center, University of Hawaii.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2024. “Sustainable development goals and food industries.” https://www.maff.go.jp/j/shokusan/sdgs/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Nagata, Yoshiyuki. 2017. A critical review of education for sustainable development (ESD) in Japan: Beyond the practice of pouring new wine into old bottles. Educational Studies in Japan 11. 29–41.Search in Google Scholar

https://doi.org/10.7571/esjkyoiku.11.29 Search in Google Scholar

Nishitani, Kumitaka. 2009. An empirical study of the initial adoption of ISO 14001 in Japanese manufacturing firms. Ecological Economics 68(3). 669–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.05.02310.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.05.023Search in Google Scholar

Nishitani, Kumitaka, Thi Bich Hue Nguyen, Throng Quy Trihn, Qui Wu & Katsuhiko Kobuku. 2021. Are corporate environmental activities to meet sustainable development goals (SDGs) simply greenwashing? An empirical study of environmental management control systems in Vietnamese companies from the stakeholder management perspective. Journal of Environmental Management 296. 113364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113364Search in Google Scholar

Norris, John, M., John McE Davis, Castle Sicicrope & Yukiko Watanabe (eds.). 2009. Toward useful program evaluation in college foreign language education. Hawaii: National Foreign Language Resource Center, University of Hawaii. Search in Google Scholar

O’Flaherty, Joanne & Mags Liddy. 2017. The impact of development education and education for sustainable development interventions: A synthesis of the research. Environmental Education Research 24(7). 1031–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1392484Search in Google Scholar

Okimoto, Tatsuyoshi & Sumiko Takaoka. 2024. Sustainability and credit spreads in Japan. International Review of Financial Analysis 91. 103052.Search in Google Scholar

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.103052 10.1016/j.irfa.2023.103052Search in Google Scholar

Olsson, Daniel, Niklas Gericke & Jelle Boeve-de Pauw. 2022. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited: A longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability. Environmental Education Research 28(3). 405–429.Search in Google Scholar

https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2033170 10.1080/13504622.2022.2033170Search in Google Scholar

Patton, Michael Quinn & Charmogne E. Campbell-Patton. 2022. Utilization-focused Evaluation (5th edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Rieckmann, Marco, Lisa Mindt & Senan Gardiner. 2017. “Education for sustainable development goals Learning objectives. UNESCO.”Search in Google Scholar

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed 31 May 2024). Search in Google Scholar

Risager, Karen. 2007. Language and culture pedagogy: From a national to a transnational paradigm. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. 10.21832/9781853599613Search in Google Scholar

Sasajima, Shigeru. 2015. CLIL atarashii hassou no jugyou: Rika ya rekishi wo gaikokugo de oshieru? [CLIL new idea for teaching: Teaching science and history in a foreign language?]. Tokyo: Sanshusha. Search in Google Scholar

Shaules, Joseph. 2016. The development of model of linguaculture learning: An integrated approach to language and culture pedagogy. Juntendo Journal of Global Studies 1. 2–17.Search in Google Scholar

Sony. 2024. “Sustainability.” from https://www.sony.com/en/SonyInfo/csr/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Tanaka, Haruhiko. 2017. Current state and future prospects of education for sustainable development (ESD) in Japan. Educational Studies in Japan 11. 15–28. https://doi.org/10.7571/esjkyoiku.11.15Search in Google Scholar

The Japanese Society of Education for Sustainable Development. 2004.Search in Google Scholar

https://jsesd.xsrv.jp/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Toyota. 2024. “Sustainable development goals.” Search in Google Scholar

https://global.toyota/en/sustainability/sdgs/#/earth (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

United Nations. 2024 a. “The 17 Goals.” https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

United Nations. 2024 b. “Sustainable development goals.”Search in Google Scholar

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sdg-fast-facts/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

United Nations Statistics Division. 2024. “The sustainable development goals report 2023: Special edition.” https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sdg-fast-facts/ (accessed 31 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Watanabe, Yoshinori, Makoto Ikeda & Shinichi Izumi. 2011. CLIL (Content and language integrated learning): New challenges in foreign language education at Sophia University, Volume 1: Principles and methodologies. Tokyo: Sophia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2024-0041).

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Promoting sustainability in European language teaching

- Language teachers as educators for sustainability in Finland – Factors influencing teachers’ perception of their agency

- Finnish pre-service language teachers’ understanding of culture – from cultural humility to social justice

- Addressing linguistic and social sustainability: morphological awareness among multilingual students with varying first-language literacy levels

- Incorporating Sustainable Development Goals into an English for Global Citizenship Curriculum at an International Liberal Arts University in Japan

- Analyzing the effectiveness of dialogue practice in English as a lingua franca using the model of Transformative Language Teaching for Sustainability