Abstract

This paper looks into how German and international students make use of their respective multilingual repertoires for the construction of academic knowledge. After a short survey of previous research on benefits and problems of English medium instruction for non-native speakers of English two explorative studies carried out at a German university will be presented which highlight the practices / preferences of students for language choice in various types of communication at the university and the underlying motives and assumptions for these choices. Different from previous research, which concentrates mainly on the official teaching-learning discourse in lectures and seminars, these studies focus on the complex interplay of various types of text and discourse typical of university contexts of teaching and learning. The first one deals with note-taking in lectures, the second one is a questionnaire study on preferred language choices in academic contexts of communication. The results suggest that students do not fully exploit their multilingual resources and that their preferred language choices tend to lead to a mere reproduction of knowledge. Therefore suggestions are formulated for a more productive use of students’ multilingualism enhancing the depth of processing and the availability of academic knowledge.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Beitrag beschäftigt sich mit der Frage, wie deutsche und internationale Studierende ihr jeweiliges Mehrsprachigkeitsrepertoire für die Konstruktion akademischen Wissens einsetzen. Nach einem kurzen Überblick über bisherige Forschungen zu Nutzen und Problemen englischsprachiger Lehre für Nichtmuttersprachler des Englischen werden zwei explorative Studien vorgestellt, die an einer deutschen Universität durchgeführt wurden und die Praktiken bzw. Präferenzen der Sprachenwahl von Studierenden in universitären Kommunikationssituationen und die diesen Praktiken/Präferenzen zugrundeliegenden Annahmen beleuchten. Dabei wird – anders als bei der in bisherigen Untersuchungen vorherrschenden Fokussierung auf den offiziellen Lehr-Lerndiskurs in Vorlesungen und Seminaren – das komplexe Zusammenspiel unterschiedlicher Text- und Diskurstypen, durch das universitäre Kommunikation charakterisiert ist, in den Blick genommen. In der ersten Studie geht es um die Sprachenwahl beim Mitschreiben von Vorlesungen. Bei der zweiten Studie handelt es sich um eine Fragebogenstudie zu Präferenzen für die Sprachenwahl in unterschiedlichen studiumsbezogenen Kommunikationssituationen. Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass Studenten ihre mehrsprachigen Ressourcen nur eingeschränkt nutzen und dass ihre Präferenzen für die Sprachenwahl tendenziell zu einer bloßen Reproduktion von Wissen führen. Der Beitrag endet mit Vorschlägen für eine produktivere Nutzung der Mehrsprachigkeit der Studierenden zur Steigerung von Verarbeitungstiefe und Verfügbarkeit akademischen Wissens.

Resumen

Este trabajo versa sobre el uso que estudiantes alemanes y alumnos internacionales hacen de sus respectivos repertorios multilingües en la construcción del conocimiento académico. Tras un breve análisis de los beneficios y los problemas que la enseñanza en inglés plantea para los alumnos cuya lengua materna no es el inglés, se presentan dos estudios exploratorios realizados en una universidad alemana que ponen de manifiesto las prácticas y preferencias que estos alumnos manifiestan en sus elecciones lingüísticas a la hora de participar en distintos intercambios comunicativos, así como las motivaciones y supuestos en los que se basa dicha elección. A diferencia de la investigación previa centrada especialmente en el análisis del discurso oficial del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en las clases universitarias y los seminarios, estos dos estudios se centran en la compleja interacción de varios tipos de textos y discursos de los contextos universitarios de enseñanza y aprendizaje. El primer estudio trata de la toma de notas durante la clase, mientras que el segundo da cuenta de un cuestionario sobre las preferencias de elección de lengua en dichos contextos de comunicación. Los resultados sugieren que los alumnos universitarios no explotan sus recursos multilingües y que sus preferencias de elección lingüística tienden a acabar en una mera reproducción del conocimiento. Por tanto, se proponen sugerencias para potenciar un uso más productivo del mutilingüismo de los alumnos aumentando la profundidad del procesamiento y la disponibilidad del conocimiento académico.

9 References

Airey, John. 2010. The ability of students to explain science concepts in two languages. Hermes – Journal of Language and Communication Studies 45. 35–49.10.7146/hjlcb.v23i45.97344Search in Google Scholar

Airey, John. 2011. The relationship between teaching language and student learning in Swedish university physics. In Bent Preisler, Ida Klitgard & Anne H. Fabricius (eds.) Language and learning in the international university. From English uniformity to diversity and hybridity, 3–18. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847694157-004Search in Google Scholar

Airey, John. 2012. ‘I don’t teach language.’ The linguistic attitudes of physics lecturers in Sweden. AILA Review 25. Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education. 64–79.10.1075/aila.25.05airSearch in Google Scholar

Altbach, Philip G., Liz Reisberg & Laura E. Rumbley. 2009. Trends in global higher education. Report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Congress on Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO.10.1163/9789004406155Search in Google Scholar

Backus, Ad, Durk Gorter, Karlfried Knapp, Rosita Schjerve-Rindler, Jos Swanenberg, Jan D. ten Thije & Eva Vetter. 2013. Inclusive multilingualism: Concept, modes and implications. European Journal of Applied Linguistics 1(2). 179–215.Search in Google Scholar

Bartolotti, James & Viorica Marian. 2014. Bilingual memory: structure, access, and processing. In Jeanette Altarriba & Ludmila Isurin (eds.), Memory, language and bilingualism: Theoretical and applied approaches, 7–47. Cambridge: CUP10.1017/CBO9781139035279.002Search in Google Scholar

Björkmann, Beyza. 2013. English as an academic lingua franca. Berlin etc.: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110279542Search in Google Scholar

Bolton, Kingsley & Maria Kuteeva. 2012. English as an academic language at a Swedish university: parallel language use and the “threat” of English. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 33. 429–447.10.1080/01434632.2012.670241Search in Google Scholar

Cenoz, Jasone & Durk Gorter. 2011. A holistic approach to multilingual education: Introduction. Modern Language Journal 95. 339–343.10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01204.xSearch in Google Scholar

Dalton-Puffer, Christiane. 2013. A construct of cognitive discourse functions for conceptualising content-language integration in CLIL and multilingual education. European Journal of Applied Linguistics 1(2). 216–252.10.1515/eujal-2013-0011Search in Google Scholar

Doiz, Aintzane, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013a. English-medium instruction at universities. Global challenges. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847698162Search in Google Scholar

Doiz, Aintzane, David Lasagabaster & Manuel Sierra. 2013b. Future challenges for English-Medium Instruction at the tertiary level. In Aintzane Doiz, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013. English-medium instruction at universities. Global challenges, 213–221. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847698162-015Search in Google Scholar

Doiz, Aintzane, David Lasagabaster & Manuel Sierra. 2013c: English as L3 at a bilingual university in the Basque Country, Spain. In Aintzane Doiz, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013. English-medium instruction at universities. Global challenges, 84–100. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters10.21832/9781847698162-009Search in Google Scholar

Fandrych, Christian & Betina Sedlaczek. 2012. “I need German in my life”. Eine empirische Studie zur Sprachsituation in englischsprachigen Studiengängen in Deutschland. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag Brigitte Narr.Search in Google Scholar

Fishman, Joshua. 2000. Who speaks what language to whom and when?. In Li Wei (ed.): The bilingualism reader, 89–106. London/ New York: RoutledgeSearch in Google Scholar

Gogolin, Ingrid. 1994. Der monolinguale Habitus der multilingualen Schule. Münster: Wax-mann.Search in Google Scholar

Hellekjaer, Glenn Ole. 2006. Screening criteria for English-medium programmes: A case study. In Robert Wilkinson, Vera Zegers & Charles van Leeuwen (eds.). 2006. Bridging the assessment gap in English-medium higher education. Bochum: AKS-Verlag, 43–60.Search in Google Scholar

Hellekjaer, Glenn Ole. 2010. Language matters: Assessing lecture comprehension in Norwegian English-medium higher education. In Christiane Dalton-Puffer, Tarja Nikula & Ute Smit (eds.) Language use and language learning in CLIL classrooms, 233–258. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/aals.7.12oleSearch in Google Scholar

Hincks, Rebecca.2010. Speaking rate and information content in English lingua franca oral presentations. English for Specific Purposes 29 (1). 4–18.10.1016/j.esp.2009.05.004Search in Google Scholar

Kling, Joyce M. & Lars S. Stæhr. 2011. Assessment and assistance: Developing university lecturers’ language skills through certification feedback. In R. Cancino, K. Jæger & L. Dam (eds). 2011. Policies, principles, practices: New directions in foreign language education in the era of educational globalization, 213–245. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kling, Joyce M. & Lars S. Stæhr. 2012. The development of the Test of Oral English Proficiency for Academic Staff (TOEPAS). University of Copenhagen.Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Annelie & Anja Münch. 2008. Doppelter Lernaufwand? Deutsche Studierende in englischsprachigen Lehrveranstaltungen. In Annelie Knapp & Adelheid Schumann (eds.). 2008. Mehrsprachigkeit und Multikulturalität im Studium, 169–193. Frankfurt / Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Annelie. 2011a. Using English as a lingua franca for (mis-)managing conflict in an international university context: An example from a course in engineering. Journal of Pragmatics. 43 (4). 978–990.10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.008Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Annelie. 2011b. When comprehension is crucial: Using English as a medium of instruction at a German university. In: Annick De Houwer & Antje Wilton (eds.). English in Europe today. Sociocultural and educational perspectives, 51–70. Amsterdam: John Benjamins10.1075/aals.8.05knaSearch in Google Scholar

Knapp, Annelie. 2012. Das MUMIS-Projekt. In: Adelheid Schumann (Hg.) Interkulturelle Kommunikation in der Hochschule, 11–16. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag10.1515/transcript.9783839419250.11Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Annelie & Silke Timmermann. 2012. UniComm English – ein Formulierungswörterbuch für die Lehrveranstaltungskommunikation. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 41 (2). 42–59.Search in Google Scholar

Mauranen, Anna. 2012. Exploring ELF. Academic English shaped by non-native speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Meuter, Renata. 2009. Neurolinguistic contributions to understanding the bilingual mental lexicon. In Aneta Pavlenko (ed.): The bilingual mental lexicon. Interdisciplinary approaches, 1–25. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters10.21832/9781847691262-003Search in Google Scholar

Preisler, Bent, Ida Klitgard & Anne Fabricius (eds.). 2011. Language and learning in the international university. From English uniformity to diversity and hybridity. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847694157Search in Google Scholar

Redder, Angelika, Dorothee Heller & Winfried Thielmann (Hgg.). 2014. Eristische Strukturen in Vorlesungen und Seminaren deutscher und italienischer Universitäten. Analysen und Transkripte. Heidelberg: Synchron.Search in Google Scholar

Seidlhofer, Barbara. 2011. Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford: OUP.Search in Google Scholar

Shohamy, Elana. 2013. A critical perspective on the use of English as a medium of instruction at universities. In Aintziane Doiz, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013. English-medium instruction at universities: Global challenges, 196–210. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters10.21832/9781847698162-014Search in Google Scholar

Siepmann, Dirk, John D. Gallagher, Mike Hanney & Lachlan Mackenzie. 2008. Writing in English: A guide for advanced learners. Tübingen/ Basel: Francke.Search in Google Scholar

Smit, Ute. 2010: English as a lingua franca in higher education. A longitudinal study of classroom discourse. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110215519Search in Google Scholar

Smit, Ute and Emma Dafouz. 2012. Integrating content and language in higher education. An introduction to English-medium policies, conceptual issues and research practices across Europe. AILA Review 25. Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education, 1–12.Search in Google Scholar

Thielmann, Winfried. 2009. Deutsche und englische Wissenschaftssprache im Vergleich. HInführen – Verknüpfen – Benennen. Heidelberg: Synchron Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Thielmann, Winfried. 2012. Zur Einzelsprachenspezifik wissenschaftlichen Sprachausbaus im gnoseologischen Funktionsbereich von Sprache. Linguistik online 52 (2/12). 53–68.10.13092/lo.52.296Search in Google Scholar

van den Broek, Paul. 2010. Using texts in science education: Cognitive processes and knowledge representation. Science 328, 453–456.10.1126/science.1182594Search in Google Scholar

van der Walt, Christa. 2013. Multilingual higher education. Beyond English medium orientations. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847699206Search in Google Scholar

van der Walt, Christa & Martin Kidd. 2013. Acknowledging academic biliteracy in higher education assessment strategies: A tale of two trials. In Aintzane Doiz, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013. English-medium instruction at universities. Global challenges, 213–221. Bristol etc.: Multilingual MattersSearch in Google Scholar

Vinke, A.A., J. Snippe & W. Jochems. 1998. English-medium content courses in non-English higher education: A study of lecturer experiences and teaching behaviours. Teaching in Higher Education 3. 383–394.10.1080/1356215980030307Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, Robert. 2013. English-medium instruction at a Dutch university: Challenges and pitfalls. In Aintzane Doiz, David Lasagabaster & Juan Manuel Sierra (eds.). 2013. English-medium instruction at universities. Global challenges, 3–23. Bristol etc.: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847698162-005Search in Google Scholar

Appendix1 Source texts for note-taking

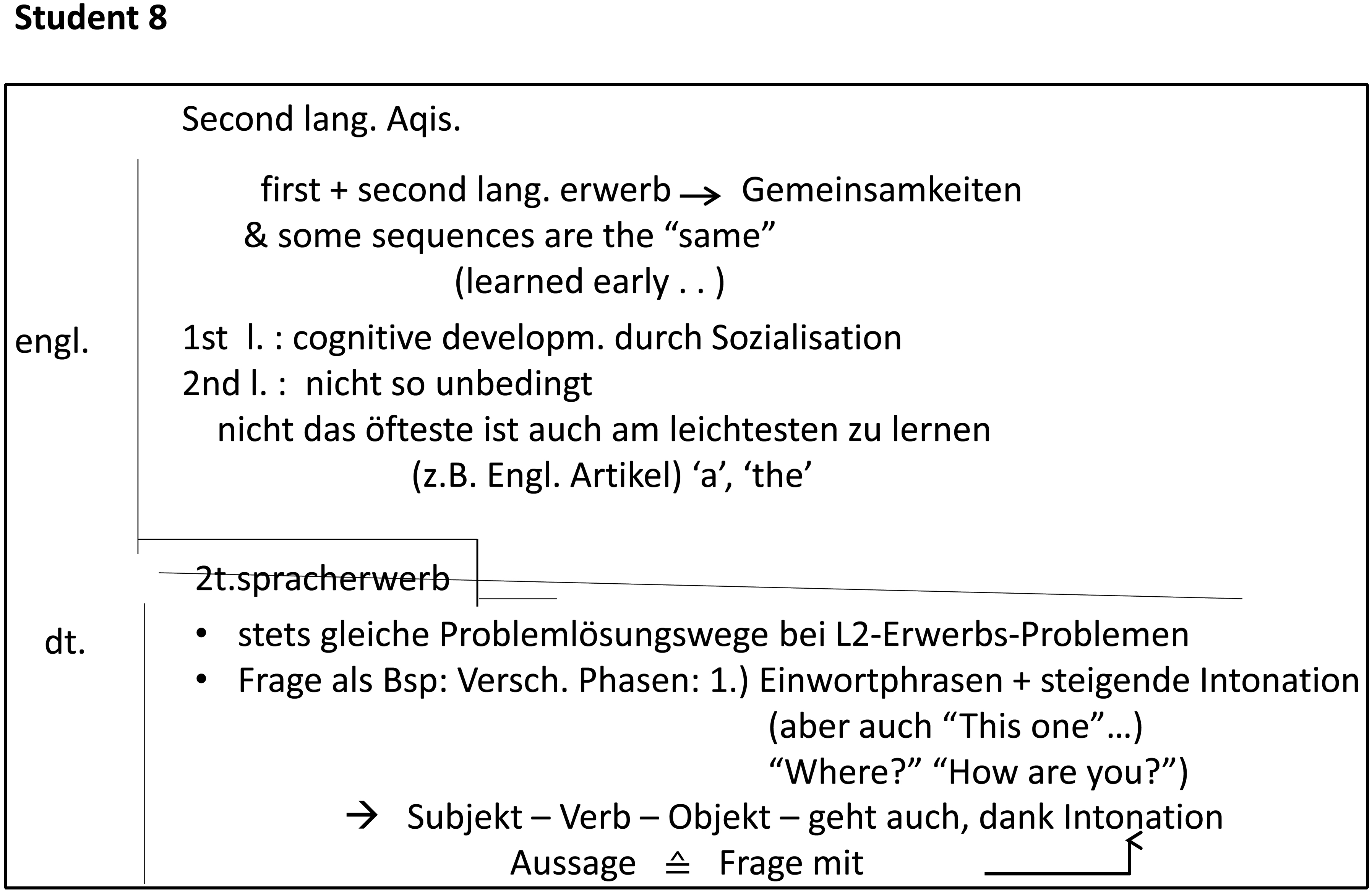

A Lernersprache

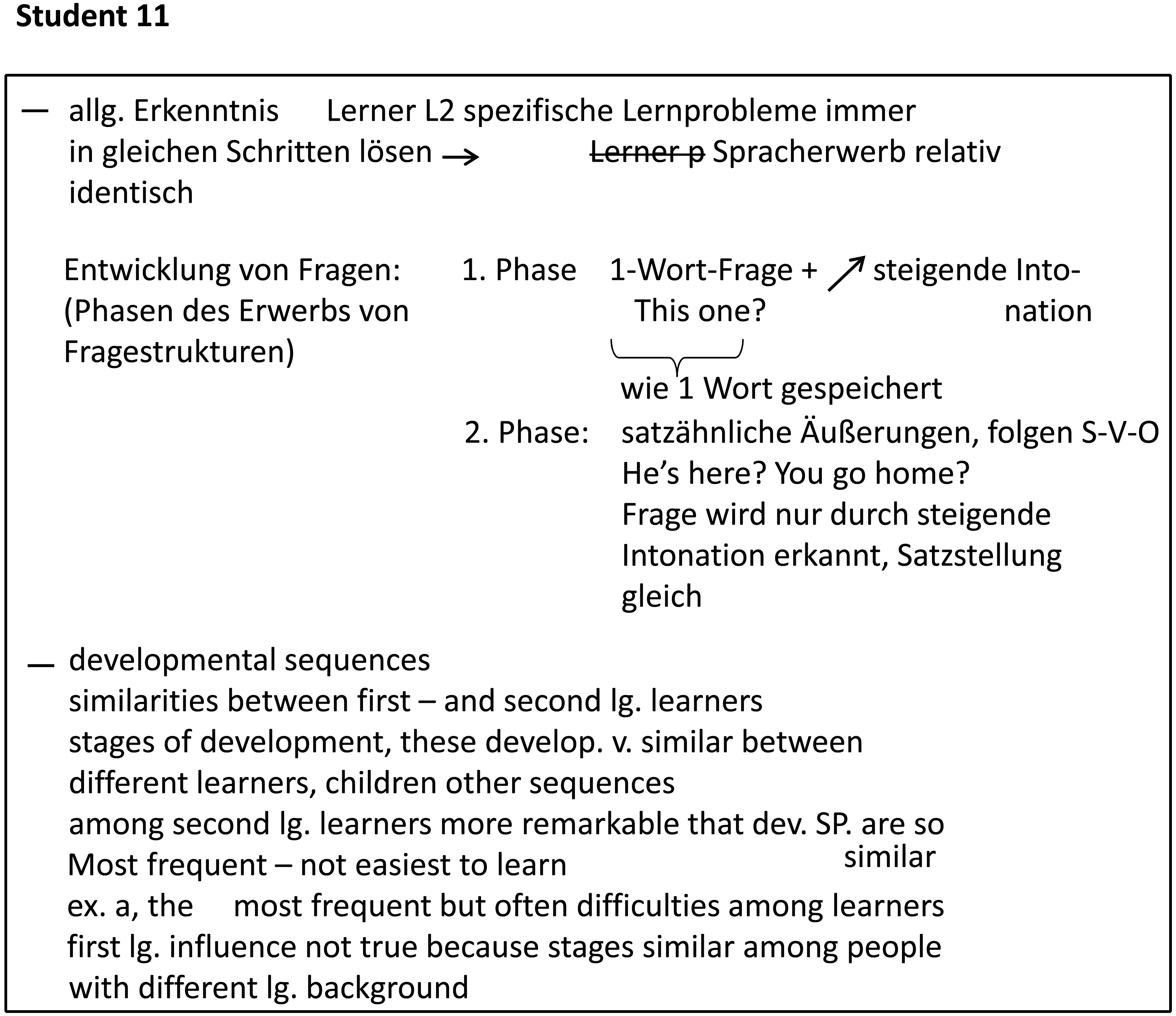

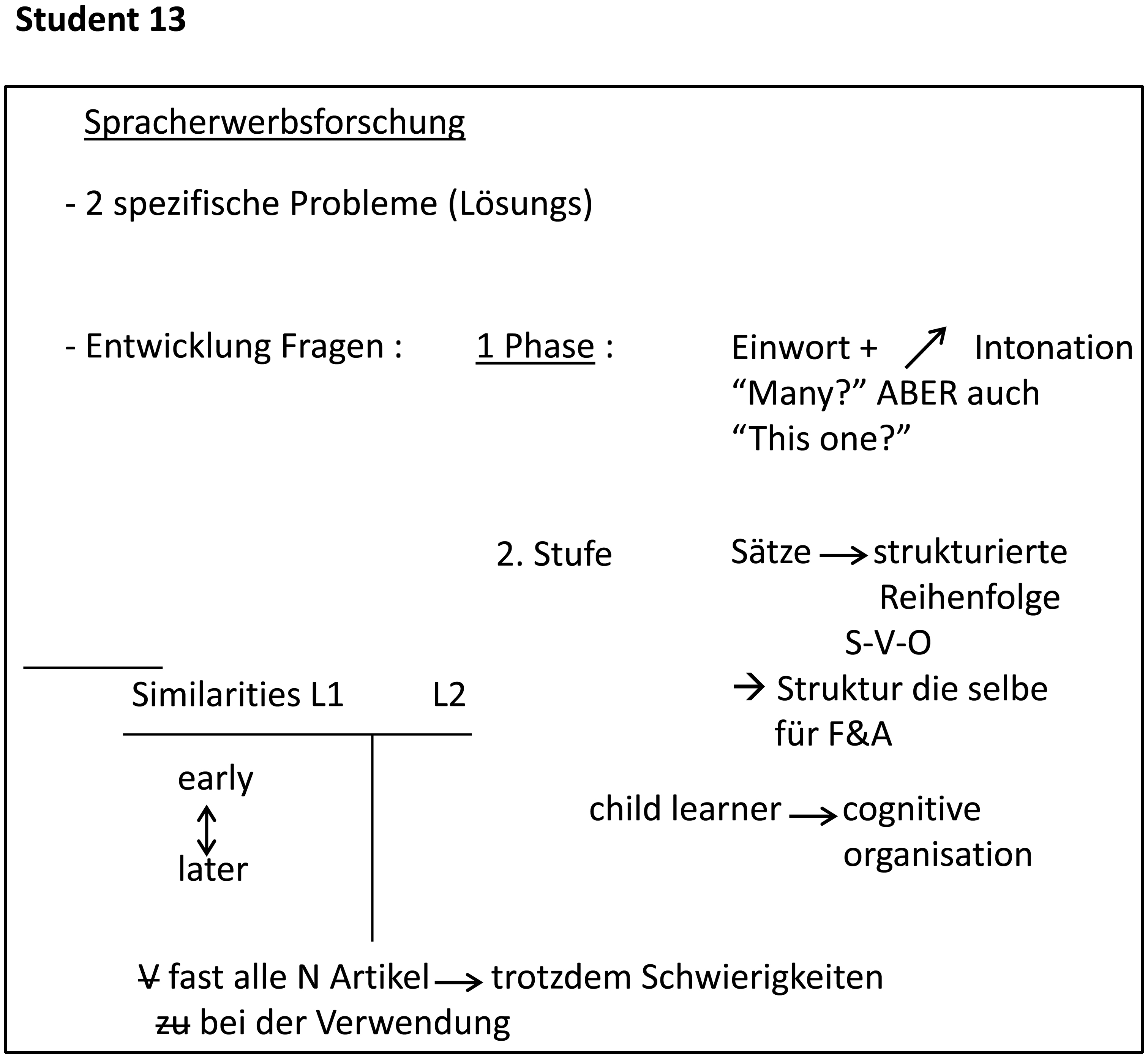

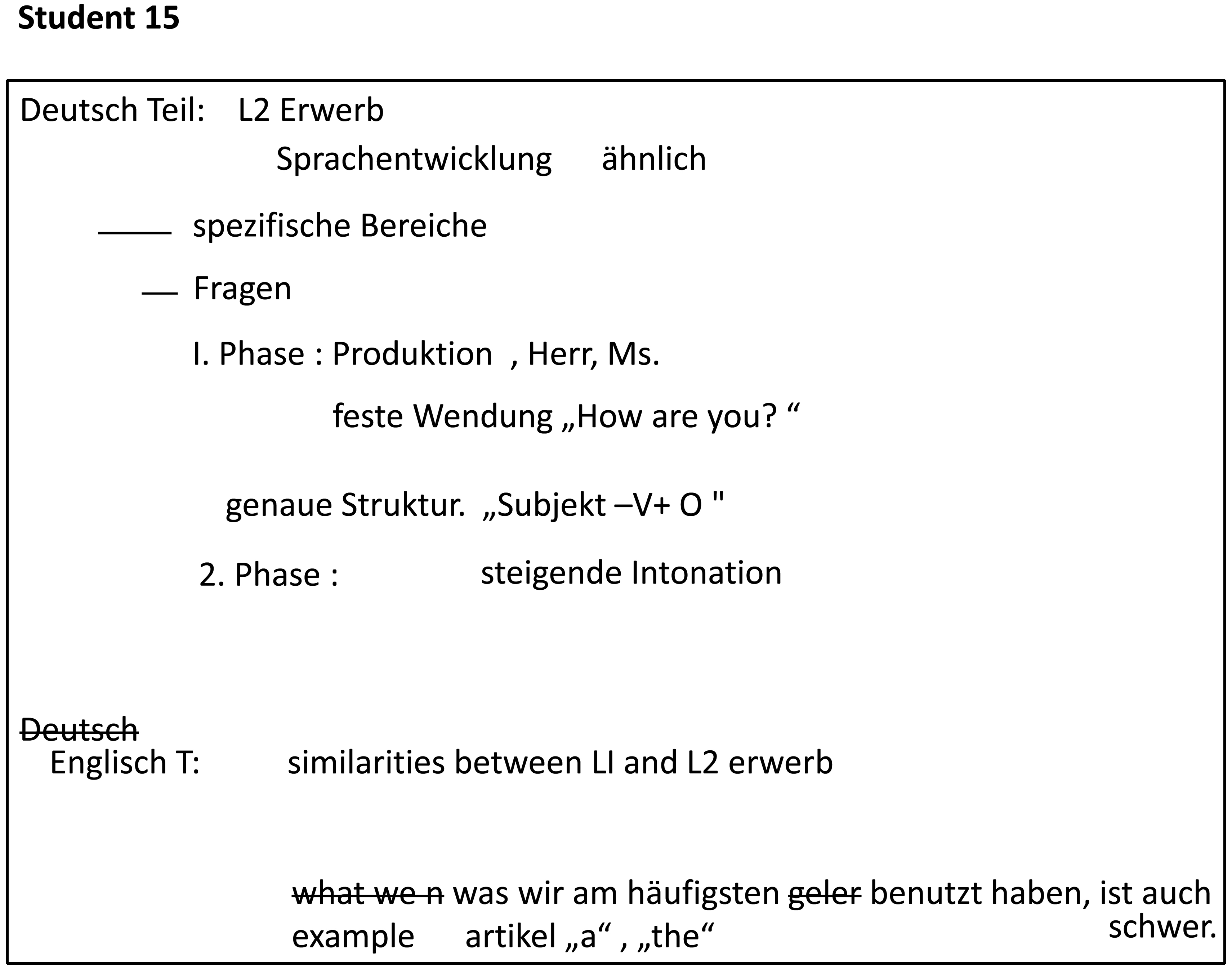

Eine allgemeine Erkenntnis der L2-Erwerbsforschung besteht darin, dass Lerner L2-spezifische sprachliche Lernprobleme stets in denselben Schritten lösen. Dies führt dazu, dass die sprachlichen Entwicklungsstadien einzelner Lerner erstaunlich ähnlich sind.

Wie sieht nun die Zweitsprachenentwicklung genauer aus? Konzentrieren wir uns dabei zunächst auf einen spezifischen Bereich der L2-Entwicklung, nämlich der Entwicklung von Fragen in der Lernersprache Englisch.

Die erste Phase beim Erwerb von Fragestrukturen ist die Produktion von Ein-Wort-Fragen mit steigender Intonation, zum Beispiel “here?” oder “this one?” oder “my money?”. Wie man sieht, muss man dabei die Definition des Begriffs “Wort” ein wenig dehnen, denn in der Zielsprache besteht die Äußerung “this one?” eigentlich aus zwei Worten. Wir wissen jedoch von der Studie von zweitsprachlichen Korpora, dass Lerner auf dieser Stufe Ausdrücke wie “this one?” als EINEN Eintrag im mentalen Lexikon speichern. Die Lernersprache enthält auf der ersten Stufe viele Ein-Wort-Einheiten dieser Art. Diese Ein-Wort-Einheiten können mit Worten der Zielsprache übereinstimmen, z. B. “where?” oder auch aus ganz festen Wendungen bestehen wie etwa “how are you?”.

Sobald Lerner satzähnliche Äußerungen produzieren, stellt man fest, dass diese einer genauen Struktur folgen, und zwar der einfachen Folge Subjekt – Verb – Objekt.

Dies gilt auch für Fragesätze, zum Beispiel “He is here?” oder “You go home?”. Dabei erkennt man die Frage an der steigenden Intonation. Das heißt, auf der zweiten Stufe ist die Wortstellung dieselbe für Fragen und Aussagen.

(taken from: Pienemann, Manfred, Jörg-U. Keßler & Eckhard Roos (Hrsg.). 2006. Englischerwerb in der Grundschule. Paderborn etc.: Ferdinand Schöningh, 34f.; slightly modified)

B Developmental sequences

Research on language acquisition has revealed that there are important similarities between first and second language learners. One important finding has been that, in both first and second language acquisition, there are sequences or ‘stages’ in the development of particular structures. That is, certain features of the language seem to appear relatively early in a learner’s language while others are acquired much later. A somewhat surprising finding is that these developmental sequences are similar across learners from different backgrounds: what is learned early by one is learned early by others.

Among child language learners, this is perhaps not so unexpected, because their language learning is partly tied to their cognitive development, that is to their learning about the relationships among people, events, and objects around them. But among second language learners, whose experience with the language may vary quite widely and whose cognitive development is essentially stable, it is more remarkable that developmental sequences are so similar. Furthermore, although learners obviously need to have opportunities to hear or read certain things before they begin to use them, it is not always the case that those features of the language which are most frequent are easiest to learn. For example, virtually every English sentence has one or more articles (‘a’ or ‘the’), but many learners have great difficulty using these forms correctly. Finally, although there is some evidence that the learners’ first language influences the sequences, many aspects of these developmental stages are similar among learners from many different first language backgrounds.

(taken from: Lightbown, Patsy & Nina Spada.1999. How languages are learned. Oxford: OUP, p. 76; slightly modified.)

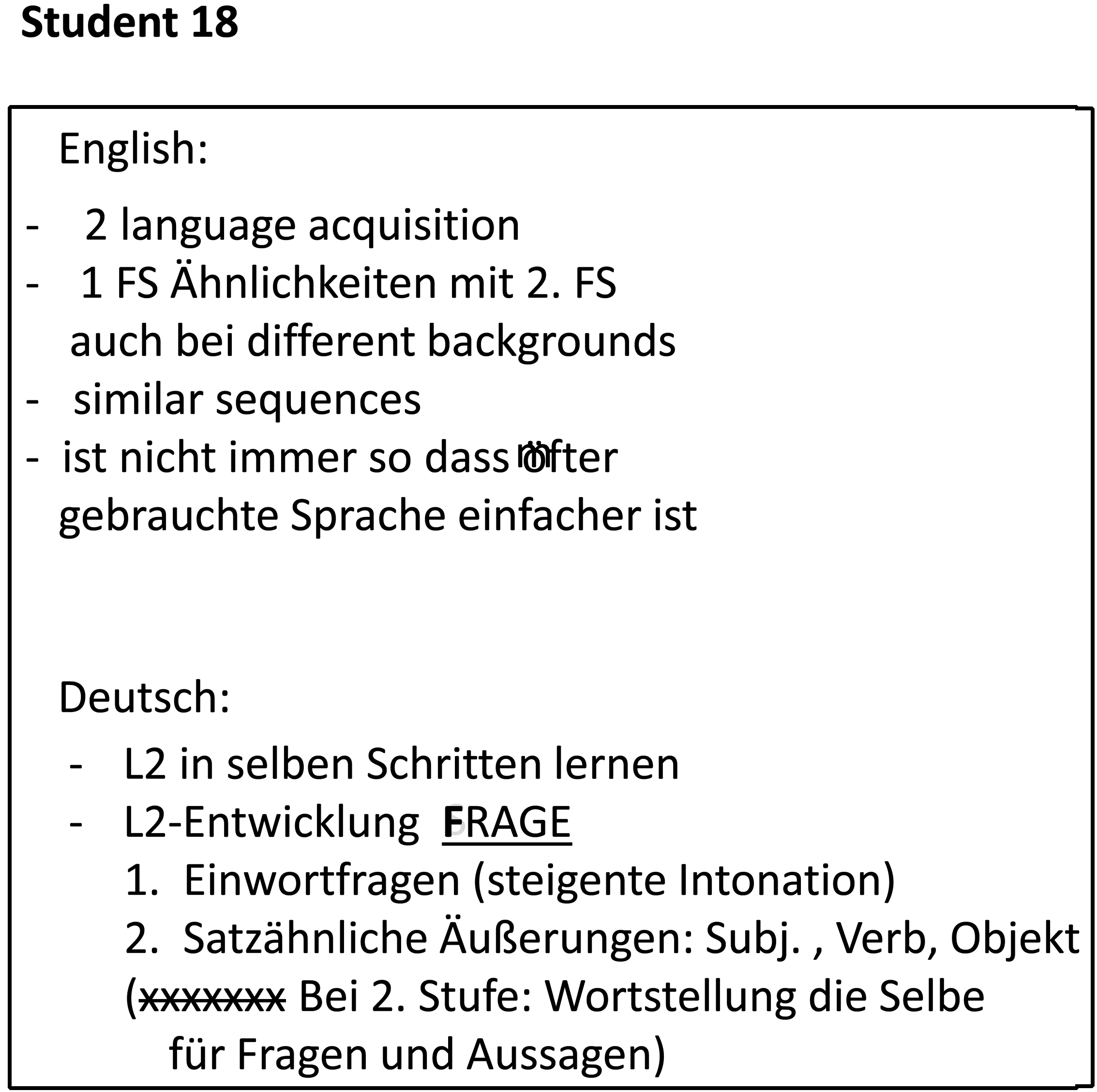

2 Examples of students’ notes

© 2014 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language choice and the construction of knowledge in higher education

- “Well I don’t know what to say to that”: Exploring tensions between the voices of medicine and the lifeworld in the management of diabetes

- Interpreting risks. Medical complications in interpreter-mediated doctor-patient communication

- The use of Basque in model D schools in the Basque Autonomous Community

- Early Foreign Language Learning: the Case of Mother Tongue Influence in Vocabulary Use in German and Spanish Primary-School EFL Learners

- On AILA Europe

- Dutch Association of Applied Linguistics: Association Néerlandaise de Linguistique Appliqée (Anéla)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language choice and the construction of knowledge in higher education

- “Well I don’t know what to say to that”: Exploring tensions between the voices of medicine and the lifeworld in the management of diabetes

- Interpreting risks. Medical complications in interpreter-mediated doctor-patient communication

- The use of Basque in model D schools in the Basque Autonomous Community

- Early Foreign Language Learning: the Case of Mother Tongue Influence in Vocabulary Use in German and Spanish Primary-School EFL Learners

- On AILA Europe

- Dutch Association of Applied Linguistics: Association Néerlandaise de Linguistique Appliqée (Anéla)