Abstract

There is widespread recognition of the vital role small and medium enterprises (SME) play in the sustainability of the Canadian rural landscape. However, rural entrepreneurs face barriers and challenges throughout the start-up and growth stages of their ventures. The rapid development of e-commerce, coupled with increasing big-box competition and shifting demographics challenge the sustainability of rural SMEs. The literature recognizes gaps in SME owner capability, pertaining to business planning, the use of financial information, the implementation of Information Technologies, and funding. It should be noted that the effectiveness of Government policies regarding support for training in these areas through publically funded agencies is well documented. However, research regarding the effectiveness of these agencies in reaching and meeting the needs of rural venture owners is primarily restricted to funding requirements. This paper examines the utilization and satisfaction of venture support agencies and community organizations by rural SME owners in 14 communities through a Business Expansion and Retention (BR&E) research project conducted in Alberta, Canada. The results indicated that agency usage can be effectively predicted by firm size, degree of localization, and planning. Results indicate that while many owners identified the need for assistance in training and funding, the utilization of support agencies, underscored by the lack of user satisfaction, may hinder rather than enhance venture viability and growth. The implications for government policy are discussed in the context of enhancing the effectiveness of support agencies, thereby contributing to the viability of ventures and the sustainability of rural communities.

1 Introduction

In Canada, and across the globe, SMEs are essential players in the realm of job growth, economic stability, and innovation (North and Smallbone 2006; OCED 2003; Smith 2006; Shields 2005). As small firms, defined as those with less than 499 employees, they have been observed to grow faster than larger firms and thus small firms have continued to operate as vehicles for employment, revenue, and trade (Krasniqi 2007). In Canada, SMEs account for 98.2% of all businesses, employing 7.7 million people, which is equivalent to 69.7% of the total private labor force (Industry Canada 2013). Small businesses have and continue to make significant contributions to Canada’s economic success, creating over 100,000 jobs, equivalent to 78% of all new private positions and 31% of total research and development expenditures, between 2002 and 2012. While only 10.4% of SMEs have been involved in, they generated sales of $150 billion, or 41% of Canada’s total export value (Industry Canada 2013). Venture owners reflect an aging population; almost 50% of SME owners between the ages of 50 and 64 years of age (Industry Canada 2013).

The distribution of Canadian ventures by size is concentrated into four industries: wholesale trade and retail (18.8%), construction (11.7%), and services (22.2%). The smallest organizations, with less than four employees, dominate several industrial sectors constituting 75.7% of service, 71.9% of agricultural, 70.3% of fishing, and 33.9% of manufacturing enterprises. Overall, Canadian SME owners are more diverse and innovative than they have been in the past, partly due to an increase in business education (Industry Canada 2012). The manufacturing industry exhibited the highest level of business innovation, with 58.1% of firms demonstrating such behavior, knowledge-based industries (50.0%), services (43.5%), and retail trade (41.1%) evolved at a greater rate than agricultural-based firms (27.8%) and transportation (27.5%). While there are high-growth firms across industry sectors, construction at 4.9%, building and support at 4.6%, and services at 4.5% represented the highest growth firms in terms of employment (Industry Canada 2013).

Resource sectors such as farming, forestry, mining, and fisheries exert a stronger, though decreasing, influence on rural-based businesses (Industry Canada 2013; Ring, Peredo, and Chrisman 2009). Today, the population of farmers in rural areas has decreased significantly and in their place new, innovative business ventures are being established (Carrington and Zantoko 2008). Moreover, rural ventures are connecting to other businesses and customers around the world through exporting and e-commerce. By 2004, only one-third of prairie province SME owners were operating a business in agriculture and other primary industries (Carrington and Zantoko 2008), juxtaposed against notable growth in the service, wholesale, and tourism sectors (Industry Canada 2012).

Due to developments in ICT technology, rural communities are overcoming traditional barriers associated with “remoteness” (North and Smallbone 2000, 2006). Although there have been major increases in small businesses, the intent behind their creation is different than in urban areas. Usually, small town entrepreneurs start a business in an effort to create their own conditions of employment or to ensure they can maintain their lifestyle in a particular rural community (Dabson 2003; Siemens 2010). Smith (2006) concluded that many of these entrepreneurs create their employment to survive instead of working to become hugely successful and expanding. In essence, they want to stay local and preserve their rural way of life. The distribution of employer breakdown is dominated by ventures employing less than 4 people (55.1%), 19.8% employ between 5 and 9, 23.3% employ 10 to 9, with only 1.7% employing between 100 and 500 (Industry Canada 2013).

It has been observed that SMEs play a pivotal role in job and bonding communities (Morris and Brennan 2000; Riding and Orser 2007). In the absence of larger counterparts, SMEs are considered to be the economic engine within rural communities. SME growth is multi-dimensional and depends upon various internal factors such as owner–manager ambition and competency, and external factors such as region-specific infrastructure and the broader economy (Shaw and Conway 2000). The majority of recent literature on Canadian SMEs focuses on new venture creation, yet limited attention has been paid to the retention and expansion of SMEs in rural areas. This paper attempts to fill this gap by providing novel evidence and a new perspective from one of Canada’s most prosperous regions, Alberta.

Alberta, with an annual growth rate of 3% over the past decade, has the fastest growing economy in Canada and is the site of a growing business community (Riding and Orser 2007). SMEs account for 99.9% of all businesses in Alberta, with a significant portion (98.2%) employing less than 100 people (Industry Canada 2013). In the Prairie Provinces 53% of entrepreneurs were located in urban areas, with 47% in rural locations, reflecting a larger number of rural entrepreneurs in Prairie Provinces compared to the rest of Canada (Industry Canada 2012).

Rural communities in Alberta, measured at 661,848 square kilometers with a population of 3.6 million, face economic and social challenges due to an aging demographic as well as the isolated nature of their lifestyle. As such, business retention is a necessary condition in order to sustain rural communities; municipal and provincial levels of government are actively seeking strategies that will work toward an effective retention system. In the current work, we examine the utilization and satisfaction of venture support agencies and community organizations by rural SME owners in 14 communities through a Business Expansion and Retention (BR&E) research project conducted in Alberta, Canada. We ask what types of SMEs are most likely to use the services of venture support agencies and how satisfied are the SME owners with the services?

Note that we follow the convention to use the terms of SME owners and entrepreneurs interchangeably (Darren and Conrad 2009). In the context of rural Alberta, we consider SME owners and entrepreneurs as they identify and subsequently explore the environmental opportunities and do not emphasize the creativity embedded in the classic Schumpeter notion of entrepreneurship (Schumpeter 1934).

In the remaining sections of the paper, we first review relevant literature to set a stage for our investigation. The following two sections present our research methodology and findings, respectively. In the final section, we conclude by highlighting the insights from the current study and pointing out directions for future research.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Barriers and Issues for Rural Communities

In rural communities, entrepreneurs encounter challenges unique to their isolated location and market, including reduced amounts of educated, skilled and available labor, limited access to technology, and difficulties associated with obtaining financing. The remoteness barrier represents the physical divide between rural businesses and cities, where most potential customers, educational institutions, government agencies, networks, and business consultants are located. In a rural setting, should an entrepreneur decide to seek advice, there may only be one accountant or bank located in their locale, thus severely limiting choice. Rural branches of banks and credit unions may tend to exclusively cater to local resources or traditional businesses, making it difficult for innovative entrepreneurs to access funding for business ventures that may extend “outside the box” (North and Smallbone 2006). There may also be a lack of infrastructure, telecommunications, suppliers, R&D facilities, and manufacturers, further inhibiting rural entrepreneurs (Siemens 2010).

Obstructed access to financing opportunities is another barrier faced by rural entrepreneurs due to bank lending preferences that are geared toward larger firms with high growth potential; smaller, remote rural firms are not seen as worthy of financing (Drabenstoff and Henderson 2006; Siemens 2010). According to Riding and Orser (2007), rural SME owners in Western Canada are more likely to turn to informal sources of financing – such as family and friends – over financing institutions, despite a fairly low rejection rate for loan applications, at 11%.

Due to the aforementioned aging demographic and a declining total population, rural communities are not overly populated with skilled workers, resulting in limited growth capabilities and, consequently, SME owners assume a majority of workforce responsibilities for the business (Carrington and Zantoko 2008). Knowledge-based rural ventures in particular face challenges in securing employees with software experience and programming skills. Rural youth seeking education in urban centers remains an ongoing brain drain trend, removing them from the local community’s labor force, often permanently (North and Smallbone 2006).

While North and Smallbone (2006) argue that the use of online education and training addresses a handful of skill gaps, some rural areas still lag behind urban areas due to limited investment in computers and software. Unless rural ventures form alliances with other firms, IT equipment may be too expensive of an investment (Gulumser-Akgun, Baycan, and Nijikamp 2011).

2.2 An Overview of BR&E

Business Retention & Expansion (BR&E) is a widely used survey employed to identify issues and strengths for small and medium enterprises (SME) (Cothran 2006; Jagoda 2010). It is a community-based economic development model that promotes job growth by identifying survival and growth barriers facing local businesses, while also facilitating practical strategies for local business owners and municipal representatives to develop an economic plan that will work toward improving the business climate and instilling local action (Salant and Dillman 1994). The model is based on the philosophy that existing firms are key to community economic prosperity, and that communities dominated by small, locally owned businesses experience greater economic stability and a higher level of prosperity as defined by socioeconomic well being (Flora et al. 1992; Lyson and Tolbert 1996).

The role of economic development agencies, government bodies and academic institutions in developing SME owner skills and capabilities is evolving, with an increased focus on linkages. The following three strategies for rural economic development are commonly acknowledged by economists and scholars:

Expansion through recruitment of entrepreneurs from outside the community (Green 2005),

Expansion of existing employers (Green, Fleischmann, and Kwong 1996; Shaffer, Deller, and Marcouiller 2006),

Enhancing the attractiveness of local amenities such as recreational centers and cultural events to attract new residents (Besser, Recker, and Parker 2009).

Business Retention and Expansion (BR&E) programs have been employed by economic development agencies in North America for over 20 years, mostly with respect to the expansion of existing employs partially due to the limited success of the other strategies (Green 2005). Job creation in particular has been predominantly generated through existing rather than new enterprises, with between 70 and 90% of all new positions emerging from existing businesses (Birch 1987; Kraybill 1995; Zoysa and Herath 2007). Multiple studies have concluded that communities dominated by small, locally owned businesses demonstrate higher levels of economic stability and enhanced socioeconomic indicators for resident well-being (Boothroyd and Davis 1993; Flore et al. 1992). While a rapidly changing economic and technological environment creates challenges, researchers have determined that a high level of small business growth may occur, most notably in the manufacturing sector. The role of economic development agencies in contributing to the advancement of owner skills, capabilities and funding opportunities is perceived to be critical to the sustainability of rural communities.

A primary goal of economic development agencies and governing bodies has been the expansion of existing local businesses and an increase in the number of entrepreneurial ventures (Besser, Recker, and Parker 2009). Typical economic development tactics include business incubators, business networks, training for owners and staff, and financial assistance for venture launch and expansion. BR&E programs provide a vital component of the economic development process by identifying the challenges facing local business owners, such as financing barriers, lack of information technology or marketing skills, as well as obstacles instituted as a result of municipal bylaws. The BR&E process is collaborative, typically involving representatives from economic development agencies and a leadership team comprised of local representatives from the business community and the municipality (Cothran 2006).

A study by Besser, Recker, and Parker (2009), based on the framework proposed by Stone (2001), distinguishes between proximal and distal outcomes, examining the impact of economic development initiatives such as BR&E projects. The study involved 99 rural towns in Iowa between 1994 and 2004, using interviews with key informants and data from the U.S. Census Bureau as the basis for their research (1990, 2000). Results verified the impact of economic events; small towns with BR&E projects between 1990 and 2000 experienced only marginal decreases in quality of life compared to larger counterparts. Further, towns that were able to successfully attract employers from outside the community and hosted a BR&E event experienced the largest increase in median household income, as well as a positive impact on the quality of life for residents (Besser, Recker, and Parker 2009).

The BR&E process has been employed in Canada with the purpose of examining barriers facing SMEs with regards to securing financing as well as the adoption of e-commerce. A study of 79 SMEs located in Corner Brook, Newfoundland identified the challenges associated with securing debt financing through the BR&E interview process and determined that the majority of firms rely upon government funding programs rather than bank financing (Jagoda and Herath 2010). The study draws attention to the enhanced capabilities of business owners through suggesting methods that work toward eliminating constraints associated with debt financing, thereby promoting venture growth. The study also clarified the use of information technology, such as e-commerce, by rural ventures. While owners were aware of the benefits of e-commerce adoption, smaller and newer firms lacked the resources to develop their website or pursue valuable functions such as online purchasing and order tracking (Jagoda 2010). The study suggested enhanced government funding and training programs targeted toward potential e-commerce adoptees, in assuming that such initiatives would contribute to economic development in rural communities.

The BR&E process entails a standard survey, which is partially modified by each community to highlight local issues and concerns, such as municipal bylaws, the shut-down of a local plant, or planning by the Chamber or municipality. Many BR&E programs rely upon volunteers, such as members of the Chamber of Commerce or other business networks to administer the survey face-to-face (Morse and Loveridge 1998). This process allows probing questions to clarify responses and can also identify critical issues that require immediate assistance. The personal interviews also establish a personal relationship and may facilitate the development of a mentoring relationship (Cothran 2006). Furthermore, mail, telephone, and Internet surveys are also employed by BR&E programs. Survey data are then analyzed to identify issues and trends, the results of which can be circulated among participants and community representatives. Researchers typically turn the planning and implementation processes over to a local planning committee comprised of SME owners and community representatives.

2.3 Role of Support Agencies

When faced with challenges during the venture start-up period, many rural entrepreneurs require external help and advice in the midst of trials and tribulations. Government agencies, banks, accountants, lawyers, universities, R&D development centers, local networks and business networks extend guidance to businesses in remote locations; otherwise, these businesses would struggle to find success in rural contexts (Arikan 2010; Dyer and Ross 2008). There are many services, both public and private, which seek to enhance the entrepreneurial climate in rural communities, including government-funded venture support agencies that provide financing, business plan development and skill development for marketing and employee management through direct consultation, as well as extensive online aid via website access. Public agencies are located in larger cities, using websites and phone services to connect with rural entrepreneurs. Publicly funded agencies can also facilitate the creation of value between firms through workshops and networking events, where owners can meet each other and create strategic alliances (Konsti-Laakso, Pihkala, and Kraus 2012).

The impact of support agencies in venture launch and growth is unproven to date; there have been numerous studies that have observed many rural entrepreneurs to not utilize public services for their businesses. A study by Gasse et al. (2004) found that only around one-third of new Canadian entrepreneurs who responded had utilized public agencies when they started their business. Wyckham, Wedley, and Culver (2001) conducted a study wherein 279 Canadian entrepreneurs found public support agencies to be unimportant (2.19 on a 5 point scale with 1 being little importance, and 5 being great importance). Several studies have observed a low utilization rate of publicly support agencies (Curran and Blackburn 2000; Bennett and Robson 1999; Stevenson and Lundström 2001), with one Canadian study by Good and Graves (1993) finding that just 10% of the 160 entrepreneurs surveyed had sought agency support. The experience level of the SME owner has been identified as a determining factor in the usage of support agencies, with owners in the post-launch stage more likely to reference their own experience than seek assistance from agencies (Audet and St. Jean 2007; Jay and Schaper 2003).

Business plan preparation is a core offering by government-funded support agencies. Plans are perceived to be key determinants in venture viability and sustainability due to both external requirements, such as funding agencies, and internal capacity as an instrument to improve performance (Castrogiovannie 1996; Honig and Karlsoon 2004; Stone and Brush 1996 Planning proponents argue that the benefits of planning include faster decision making, reduction of uncertainty, the introduction of controls and new forms of actuation, allowing firms to reduce uncertainty, predict and better prepare for the future (Delmar and Shane 2003; Goll and Rasheed 1997; Wiltbank et al. 2006). Detractors of planning observe that the resources required to prepare the plan are counterproductive for the organization and may contribute to cognitive rigidities and limited flexibility (Vesper 1993). Brinckmann et al. (2010) established that business planning is relevant for the success of both new and established SMEs, particularly in rapidly changing or challenging environments. Both the outcome and the process impact firm success, as written plans and a comprehensive process provide greater probability of firm sustainability and success. The process of business planning – planning meetings, market and scenario analysis, the use of financial forecasting, competitive analysis, and the use of information technology – augments firm performance (Brinckmann et al. 2010). As such, the role of agencies as facilitators in plan preparation could be a strategic contributor to venture success and sustainability.

However, many rural entrepreneurs prefer to rely upon word of mouth, family, and friends for business support as opposed to government agencies (Audet and St-Jean 2007; Shields 2005; North and Smallbone 2006). Furthermore, should a rural entrepreneur seek external help, it is usually in the form of accountants, bankers, or lawyers, as these professionals are vital in the start-up process (Dyer and Ross 2008).

There are many factors which influence SME owners to bypass support agencies, including (1) the services offered are perceived to be ill-fitting or unsupportive of their business needs (Curran and Blackburn 2000; Dalley and Hamilton 2000); (2) a lack of confidence in the support agency itself, or the processes required to receive help (Curran and Blackburn 2000); (3) business owners are unaware of the services offered (Audet and St-Jean 2007; Curran and Blackburn 2000; Dalley and Hamilton 2000; North and Smallbone 2006; Young 2002); (4) the application process is difficult and takes too much time (Dalley and Hamilton 2000; Young 2002); and (5) business owner perception that they do not require external help (Audet and St-Jean 2007; Curran and Blackburn 2000; Pineda et al. 1998, Pineda, Lerner, and Miller 2003).

A Canadian study by Audet et al. (2007) determined that 80% of users sought agency assistance for funding, with training being a minor motivator for seeking advice. Their findings are supported by (Shanklin and Ryans 1998; Wyckham, Wedley, and Culver 2001) who determined securing financing as the most important area of support provided by agencies.

The negative perception of public service agencies by SME owners is a significant barrier to the utilization of such services. The cause of the negative perception has not been identified in its entirety and it is unclear how personal experiences versus media and social influences affect said perception. A limited degree of literature has suggested that once business owners have experience with venture agencies, they are more likely to find them useful (Audet and St-Jean 2007; Curran and Blackburn 2000). As such, a key to agency usage may entail both building awareness of agency services and overcoming the venture owner’s lack of trust. One study suggested that social relationships within the community are a proven resource that builds trust and understanding of these public services (Woodhouse 2006). Due to common backgrounds, shared experiences and frequent interactions, rural communities have strong social relationships and trust (Peredo and Chrisman 2006), contributing to the preference by SME owners to refer to family and friends for business support.

The questions emergent from the literature pertaining to SME owner use of venture support agencies refer not only to the degree to which agencies address the needs of owners but also the relative degree to which the plethora of support agencies are sought out by owners. Researchers have limited their research to the study of utilization patterns for one aspect of usage, such as venture launch or financing, or the relationship between a single agency and SMEs. Studies also limited the range of their analysis in rural agency usage to government-funding agencies, not recognizing the role of social business networking organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce. We seek to provide insight into how SME owners perceive the expected satisfaction gleaned from support agencies across Alberta. Our main research questions consist of two related questions as given below:

Do venture support agencies meet the needs requirements of rural SMES?

What are the patterns of usage of services

What organizational factors can predict the use of agency/services

How satisfied are the users of these agencies and what are the patters of satisfaction?

It should be noted that many of the agencies exist as provincial outlets for Canadian federal agencies and the processes are often replicated and offered to SMEs across Canada. As such, the agencies provide a full spectrum of support organizations available to SME owners.

3 Methodology

The authors are engaged in an Alberta wide study with researcher teams from four post-secondary institutions working with 14 rural communities. The BR&E model was employed to investigate rural business retention and expansion constraints and opportunities. The data collection was conducted in two stages. First a survey questionnaire was used to gather various types of information of rural businesses including size, number of employees, use of support agencies, etc. This also included open-ended questions where business owners could provide detailed description on challenges on agency usage. Then, a semi-structured questionnaire was used to gather detailed information on use of agencies and future plans. The survey contains 79 questions and typically requires 20 min for the participant to complete. The survey is an adaptation of a widely used instrument, with the exception of an added section pertaining to SME owners’ use and perception of venture support agencies. Agencies referenced in the survey are either funded by the provincial or federal government or member organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce. Participants were asked to evaluate their experiences with the agencies over the past three years. The agencies typically offer both urban and rural support to SME owners and have been operational for more than a decade, with some having offered services for over fifty years. A brief description and website reference for each agency are provided in Table 1.

Agencies providing SME support.

| Agency providing SME support | Description of services |

| Regional Economic Development Agency (REDA) | The primary purpose of the Regional Alliance Agencies (REDA) is to support the continued development of a provincial network. These alliances would enable regions to compete more effectively in a global marketplace and improve investment attraction, resulting in greater prosperity locally, regionally, and provincially. Funded by the Alberta Government REDA provides one-stop access to business information and advice, research services, seminars, and workshops. Local rural representatives also encourage investment opportunities in the each region. http://eae.alberta.ca/economic-development/regional-development.aspx |

| Canadian Youth Business Foundation (CYBF) | The Canadian Youth Business Foundation (CYBF), funded by the Canadian federal government, support venture start-up for those aged 18 to 39. CYBF assists potential entrepreneurs through the business life cycle from pre-launch planning to implementation. They provide: business plan mentoring, guidance regarding overcome challenges, network development, as well as financing. CYBF provides access to up to $50,000 in start-up financing and access to up to $30,000 in expansion financing through a partnership with the Business Development Bank of Canada. Online Business Resources are available at http://www.cybf.ca |

| Community Futures (CF) | Community Futures (CF) is a community economic development program funded by the Government of Canada through economic development agencies operating in the four western Canadian provinces. Economic initiatives include business development loans, technical support, training, and information. Local offices engage in a wide array of community initiatives, including strategic planning processes, research and feasibility studies, and the implementation of a diverse range of community economic development projects. http://www.communityfuturespanwest.ca/what-is-cf.php |

| Alberta Women’s Enterprise (AWE) | Alberta Women Entrepreneurs (AWE), which is funded by both provincial and federal governments, offers services and support for women entrepreneurs across the province. AWE provides: loans up to $150,000, training and workshops, and access to networks and markets. http://www.awebusiness.com/ |

| Local Municipality (City) | The municipalities in rural communities administer regulatory requirements pertaining to signage, water and waste management, parking, and business registration. Many also offer SME advice through their economic development office. |

| The Business Link (BL) | The Business Link is a not-for-profit organization supported by the Government of Canada and the Government of Alberta, with offices in the two major cities Edmonton and Calgary. It works with a network of business development centers across the province to provide access to resources to rural centers. Business specialists are available to provide advice on: start-up, incorporation, financing and loan programs, to product sourcing, e-business, exporting, importing, and government and private sector programs and services. Targeted assistance is available to immigrant and First Nation’s entrepreneurs. http://www.canadabusiness.ab.ca |

| Rotary Club/Rotary International or Kiwanis (RI) | Both clubs are international service clubs whose stated purpose is to bring together business and professional leaders in order to provide humanitarian services, encourage high ethical standards in all vocations, and help build goodwill and peace in the world. The clubs are secular, and typically meet weekly or monthly for social events during with their service goals, which often include local economic development initiatives. Funds are sought for health and education requirements community projects. Many rural SME owners are members of the clubs. http://sites.kiwanis.org, www.rotary.org |

| Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) | The Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) is a member-funded agency providing both services and a lobbying voice for SMEs. It represents the interests of the small business community to all three levels of government in their fight for tax fairness, reasonable labor laws, and reduction of regulatory paper burden. Mentoring is available to members through counsellors in each province. http://www.cfib-fcei.ca |

| Alberta Business Family Institute (ABFI) | The Alberta Business Family Institute (ABFI) provides support to family enterprises through: succession and estate planning, corporate governance, leadership development, and conflict resolution. Funded by the Government of Alberta ABFI has online reference material as well as long-term development for family ventures. http://www.business.ualberta.ca/Centres/ABFI.aspx |

| Local Chamber of Commerce (CC) | Chambers of Commerce are organized provincially and funded by members, with the Alberta Chapter comprised of 126 Chambers representing over 23,000 businesses. The mandate of the Alberta Chambers of Commerce is to ensure its members’ business interests are improved through the development and advocacy of pro-business policy to the provincial and federal governments. http://www.abchamber.ca |

| Export Development Canada (EDC) | Export Development Canada (EDC) is a self-financing, Crown corporation that operates at arm’s length from the Government. EDC supports and develops Canada’s export trade by helping Canadian companies respond to international business opportunities. EDC provides insurance and financial services, bonding products, and small business solutions to Canadian exporters and investors and their international buyers. A range of trade finance and risk management services is offered to Canadian exporters doing business in over 200 markets worldwide. http://www.edc.ca |

| Rural and Co-operative Secretariat (RCS) | Canada’s Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat (RCS) is responsible for coordinating the Government of Canada’s effort toward co-operative development. The Secretariat advises the government on policies affecting co-operatives, co-ordinates the implementation of such policies, and encourages use of the co-operative model for the socio-economic development of Canada’s communities. The Secretariat also enhances information sharing and collaboration among federal, provincial and territorial governments, co-operatives, academics and other stakeholders engaged in the development of co-operatives. It is engaged in rural economic development projects across Canada. http://www.canada2012.coop/en/government_of_canada/RCS |

The project was launched in the fall of 2011, using data up to December 31, 2013, as well as workshops and information sharing that have been completed or ongoing. The survey requests were sent out to 1,000 rural business owners in 14 communities in the province of Alberta. The communities were selected to represent the cross section of rural business landscape of Alberta. Most of the communities had less than 20,000 people and the largest community selected had around 60,000 people. These communities represented oil- and gas-based business communities in northern Alberta as well as agricultural-based businesses in southern Alberta. Representatives from the local Chamber of Commerce and the economic development representative from the local municipality facilitated contact with owners, who were contacted through e-mail, information sessions, and personal calls at their business location. While some participants completed online or print surveys, interviews were conducted with those owners who preferred personal meetings. Attempts were made to contact business owners ranging from home businesses to large manufacturing companies. Participation was limited to organizations with some degree of local ownership and control; franchises and branches of national operations, such as banks, were not included. The study focused on barriers, skills, perceived issues, and challenges for local owners. The respondents provided a solid representation of the business community in the area with SMEs from varied industries and organizations, ranging from owner operated ventures with only one employee to organizations with more than 100 employees. Out of the 454 responses returned, 408 of the surveys were complete and usable for the study. This represents an overall effective response rate of 40.8%, which we believe to be quite satisfactory.

Survey results were presented to participants and members of the community, such as municipal representatives and economic development officers, through workshops and community meals. Participants who could not attend were provided with results via mail or e-mail. Participants were invited to training sessions or individual consultations presented by the researchers and specialists in each community to address strategic or operational issues. Workshop topics included: developing a marketing plan, succession planning, developing an effective website, and strategic advertising and promotion. The researchers provided results to municipal and Chamber of Commerce representatives, as well as facilitating discussions with the representatives regarding strategies for local economic initiatives. Further, the researchers hosted a BR&E Symposium to present interim results with the participating venture support agencies and government funders, aiming to spark a discussion regarding potential strategies to improve SME owner satisfaction with agency services.

The data were coded and analyzed using SPSS21. First, a reliability analysis was undertaken to test the validity of the survey questions. Then, the key research questions were addressed using regression analysis and cluster analysis. However, not all of the questions included in the survey were used in the analysis due to statistical reasons (e.g. not relevant to the current paper) or other discretionary reasons (e.g. choice of content to meet the editorial requirements).

3.1 Analysis

The sample represents a good cross section of the companies operating in rural Alberta in terms of size, maturity, ownership, and the type of business activities covered. The organizations surveyed ranged from home-based businesses to large, established enterprises. The average age of firms was 17 years with a range of 1–120 years, indicating that a good majority of companies were young and are therefore expected to have relatively high interest in retention and expansion. As shown in Table 2 most of the companies in the sample had less than 10 employees. It can be observed that close to a quarter of the companies did not have employees, while 55% of the firms had 2–9 employees. The top three industry sectors represented in the sample were retail, service, and accommodation. These findings are consistent with other studies previously carried out in Canada (Jagoda and Herath 2010). More than 75% companies are locally based. Most of these companies are serving small local communities and have little appetite to expand beyond their territory.

Participant profile.

| Percent | |

| Type of industry | |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 3.3 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 1.3 |

| Construction | 7.6 |

| Manufacturing | 4.0 |

| Wholesale trade | 1.5 |

| Retail trade | 34.3 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 1.3 |

| Finance and insurance | 3.8 |

| Accommodation and food services | 6.8 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 2.0 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 2.0 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 4.8 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 2.8 |

| Public administration | 4.0 |

| Other services | 18.4 |

| Other | 2.1 |

| Total | 100.0 |

| Firm size (Number of employees) | |

| Owner only | 22.3 |

| 2–9 | 55.4 |

| 10+ | 22.3 |

| Degree of localization | |

| Non localized (Branch plant/Sales office/Franchise) | 22.1 |

| Localized | 77.9 |

We proposed three organizational factors to serve as general descriptors of the population chosen for this study: firm size (as represented by number of employees); extent of planning (as measured by use of business and succession plans); and degree of localization (measured by organization type). The selection of organizational factors was based on the previous studies related to the use of support agencies. First, the firm size measured by the number of employees has been linked to the agency usage as lack of manpower was often considered to be a hindering factor of using the agencies (Siemens 2010; Riding and Orser 2007). In other words the firms with higher number of employees are more likely to use agencies than the smaller firms. Second, the extent of planning relates to the growth expectations. The current literature suggests that the firms that have growth expectations will deploy various planning and will see for external help to achieve their goals (Honing and Karlsoon 2004). Third, we introduced the degree of localization to capture the decision-making power at local level. The current literature suggests that the more control the business owners have to make decisions at local level, the more likely they are to seek assistance from the agencies (Dimitratos et al. 2010; Muhammad, Harrison, and Beaumont-Kerridge 2009). In this context, we assume that the franchises or branch offices are less likely to seek assistance from the venture support agencies due to control of the head office.

In the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate their experience using 12 agencies and rank their satisfaction with the experience. All major agencies supporting rural communities in Alberta were included in this list of agencies. In the first step, we were interested in looking at the relationship among three organizational factors and agency usage. Usage was coded as a binary variable (i.e. owners used agency or did not use the agency) so that we could deploy logistic regression and decision tree models. Before investigating the relationship among variables, the reliability and dimensionality of the key variables used were checked using Cronbach’s alpha. Initial analysis using logistic regression revealed that more than 50% (206 cases out of 408) could not be used as they have at least one missing value in the variables. Therefore, we decided to ascribe the dataset so all cases can be used for analyses. The ascription was based on the “accumulated distribution” method, in which the objective is to keep distributions of valid values between original and ascribed datasets as close as possible.

Crosstab with Chi-square tests were first used as a pilot analysis to check the relationship between selected variables in an effort to identify the main predictors of agency usage. Agency usage was used as the column variable and ten variables including firm size, existence of business plan and succession plan, degree of localization and business owner characteristics, gender of business owner, etc. were used as row variables. The tests found that firm size, existence of business plan and succession plan were significant (Asymp Sig is below 0.05) and the degree of localization and gender of the business owner was marginal (significance between 0.05 and 0.1). These results clearly established the statistical significance of the three predictors of agency usage by rural business. The significance of co-relations between the key factors means that they can be treated as distinct variables that represent the three key constructs.

To confirm the usage patterns, logistic regression was used using binary dependent variable (agency usage) and the firm size, existence of business plan and succession plan, degree of localization and gender of the business owner were the independent variables. The results are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Cross-tabulation and chi-square.

| Variable | Pearson chi-Square | |

| Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) | |

| Size of the company | 14.576 | 0.001 |

| Degree of localization | 6.717 | 0.010 |

| Use of business plan | 5.590 | 0.018 |

| Use of succession plan | 1.101 | 0.294 |

| Gender of the business owner | 3.205 | 0.073 |

Logistic regression: classification tables.

| Observed | Predicted | ||||

| Usage | Percentage correct | ||||

| 0 | 1 | ||||

| Block 0 | |||||

| Agency usage | 0 | 0 | 120 | 0.0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 288 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall percentage | 70.6 | ||||

| Block 1 | |||||

| Agency usage | 0 | 33 | 87 | 27.5 | |

| 1 | 20 | 268 | 93.1 | ||

| Overall percentage | 73.6 | ||||

Results from logistic regression.

| Variable | B | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) |

| Degree of localization | −1.038 | 9.027 | 0.003 | 0.354 |

| Business plan | 0.847 | 5.901 | 0.015 | 2.333 |

| Succession plan | −0.772 | 5.106 | 0.024 | 0.462 |

| Firm size | −1.702 | 14.254 | 0.000 | 0.182 |

The “Overall Percentage” increased from 70.6% in Block 0 (with only constant) to 73.8% in Block 1 with all independent variables. Although the percentage was not improved significantly, the Chi-square test model was very significant (Sig=0.000), which means that these variables had a significant impact on the dependent variable. The results confirmed that degree of localization, use of business and succession plans, and the size of firm were significant predictors of agency usage. These result matched with the Chi-square test results in the Crosstab analysis.

The results showed three important trends. First, non-localized companies are less likely (ratio=0.354) to use agencies. Second, companies with a “current business plan” are more likely (ratio=2.333) to use the services of agencies than those companies without a plan. In contrast, companies that have a “current succession plan” are less likely (ratio=0.462) to use agencies than those companies without a succession plan. Third, smaller businesses (owner only or 2–9 employees) are less likely (ratio 0.182 and 0.504) to refer to an agency than bigger companies with 10 or more employees. These findings are largely consistent with those of the previous studies identified in the current literature.

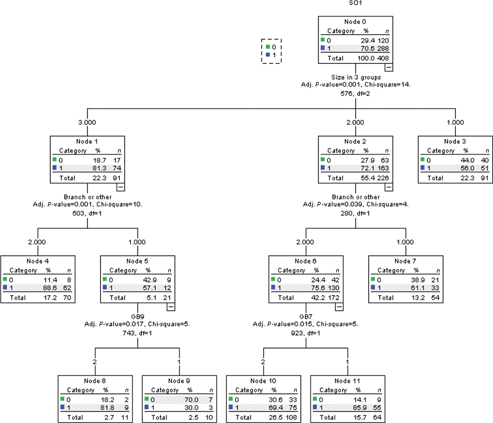

To further our analysis, decision tree models were used to analyze agency usage patterns by rural business owners. The results are shown in Figure 1. According to the results, the most significant variable predicting agency usage was firm size, followed by degree of localization, and the existence of business and succession plans. Among the 408 companies surveyed, the average usage rate was 70.6%. The rates of smaller companies were below this average. Particularly among the 91 owner-only companies (coded as 1 in the decision tree), only 56.0% identified using the services of agencies. On the other hand, among the 91 companies with 10 or more employees, the usage rate was 81.3%, significantly higher than the average. The degree of localization was identified as the next significant variable. This node shows that no matter how large the company, the incidence rates of using the agencies among highly localized companies are higher than others. These results confirmed the findings of the logistic regression and cross tabulation. When adding further variables to the decision tree, we found that companies with 2–9 employees are more likely to use the agencies if they are highly localized or have a “current business plan”. Their incidence rates were 10% higher than the average.

Decision tree.

In order to identify patterns for agency usage, we first employed cluster analysis to identify any “usage groups”, assuming that these groups represent the distinct characteristics identified in this study. The two-step clustering led to the identification of four clusters, accounting for approximately 31, 31, 30, and 7% of the sample, respectively. As shown in Table 6, the four clusters exhibited distinct features in terms of agency usage.

Cluster solution.

| Cluster | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Size | 128(31.4%) | 127(31.1%) | 125(30.6%) | 28(6.9%) |

| Inputs: Use of agencies | REDA Did not use (100%) | REDA Did not use (55.9%) | REDA Did not use (100%) | REDA Used (100%) |

| CYBF Did not use (100%) | CYBF Did not use (92.1%) | CYBF Did not use (99.2%) | CYBF Used (96.4%) | |

| CF Did not use (100%) | CF Used (54.6%) | CF Did not use (100%) | CF Used (100%) | |

| AWE Did not use (100%) | AWE Did not use (90.6%) | AWE Did not use (99.2%) | AWE Used (100%) | |

| City Used (100%) | City Used (59.1%) | City Did not use (100%) | CityUsed (100%) | |

| BL Did not use (99.2%) | BL Did not use 92.9%) | BL Did not use (99.2%) | BL Used (100%) | |

| RI Did not use (86.7%) | RI Did not use (77.2%) | RI Did not use (100%) | RI Used (96.4%) | |

| CFIB Did not use (85.2%) | CFIB Did not use (80.3%) | CFIB Did not use (99.2%) | CFIB Used (100%) | |

| ABFI Did not use (97.7%) | ABFIDid not use (97.6%) | ABFIDid not use (100%) | ABFI Used (96.4%) | |

| CC Used (75%) | CCUsed (77.2%) | CC Did not use (100%) | CC Used (100%) | |

| EDC Did not use (99.2%) | EDCDid not use (97.6%) | EDC Did not use (100%) | EDC Used (100%) | |

| RCS Did not use(100%) | RCS Did not use (98.4%) | RCS Did not use (100%) | RCS Used (85.7%) | |

| Characteristics | Number of employees 2–9 employees (57.0%) | Number of employees 2–9 employees (56.7%) | Number of employees 2–9 employees (51.2%) | Number of employees 2–9 employees (60.7%) |

| Gender of the business ownerFemale (50.8%) | Gender of the business owner Male (53.5%) | Gender of the business ownerMale (47.2%) | Gender of the business ownerFemale (67.9%) | |

| Business Plan No (60.2%) | Business Plan No (55.1%) | Business PlanNo (66.4%) | Business Plan Yes (60.7%) |

The cluster analysis confirmed multiple patterns of agency usage, and that the four groups identified are discernible. In order to explore the characteristics of the four clusters identified, the organizational and owner-specific factors identified in the literature were used. As shown in Table 5, the first cluster consists of companies that mainly used two agencies operating locally, namely City Council and the Chamber of Commerce for business development. The companies in the second cluster used a broader base of local agencies. In addition to City Council and Chamber of Commerce, the companies in this cluster sought help from a federally funded agency, Community Futures, which operates out of rural communities. By contrast, the companies in the third cluster did not use any agency or had been very light users, connecting to only one agency in the past three years. The fourth cluster consisted of companies that use agencies frequently. Most of them sought assistance from multiple agencies to solve their issues related to business retention and expansion. The companies in this cluster used multiple agencies to aid their business operations.

Table 6 also provides the percentage of the most significant variables including organization size, gender of the business owner, and the usage of a business plan to guide the operations. We then conducted one-way ANOVA to measure the characteristics that can best describe the differences. The results showed that the user groups were significantly different from each other in regard to company size, gender of the business owner, and the use of a business plan. Using Post Hoc multiple comparisons (Scheffe), we looked at organization size, gender of the business owner, and business plan usage to guide the operations more closely in light of the ANOVA results. The results are shown in Table 7. The results indicate that the organization size is the only parameter that differentiates the four clusters, while differences between clusters 1 and 4 can be explained by gender and use of business plan.

Multiple comparisons of clusters.

| Dependent variable | Two step cluster number | Mean difference | Std. Error | Sig. |

| Number of employees work at this location | 1–2 | −0.28687* | 0.08252 | 0.008 |

| 1–3 | −0.31756* | 0.08236 | 0.002 | |

| 1–4 | −0.39457* | 0.13694 | 0.042 | |

| Gender of the business owner | 1–4 | −0.318* | 0.108 | 0.035 |

| Use of Business Plan | 1–4 | 0.293* | 0.102 | 0.042 |

As the final step in our analysis, we investigated the level of satisfaction among agencies. In the survey we asked participants whether they have used any support agencies operating in or servicing their towns. If they had used an agency we then asked participants to rank their satisfaction on a scale from 1–5 (low-high). The results are summarized in Table 8. The results indicate that there is a similar pattern with respect to knowledge of and satisfaction with agencies. Most rural businesses have had business dealings with the local agencies, such as the municipal office or local Chamber of Commerce, but have had limited exposure to national or provincial agencies. Further analysis using one-way ANOVA test revealed that there are no major differences in levels of satisfaction based on size of the firm, degree of localization, and the extent of planning. Other agencies, such as Business Link showed marginal differences in satisfaction concerning the size of the firm (sig. 0.065), Export Development of Canada on the degree of localization (sig. 0.053), Alberta Women’s Enterprise (sig. 0.025), and City Council (sig. 0.053) on the extent of planning.

Satisfaction of support agencies.

| Support agency | Satisfaction | |

| Mean | Stand. Dev. | |

| Regional Economic Development Agency | 3.51 | 1.227 |

| Canadian Youth Business Foundation | 3.05 | 1.335 |

| Community Futures | 3.92 | 1.150 |

| Alberta Women’s Enterprise | 2.73 | 1.361 |

| City of Council | 3.39 | 1.178 |

| The Business Link | 2.82 | 1.335 |

| Rotary Club/Rotary International or Kiwanis | 3.74 | 1.214 |

| Canadian Federation of Independent Business | 3.23 | 1.318 |

| Alberta Business Family Institute | 2.79 | 1.409 |

| Local Chamber of Commerce | 3.40 | 1.180 |

| Export Development Canada | 2.66 | 1.285 |

| Rural and Co-operative Secretariat | 2.46 | 1.476 |

4 Discussion

Overall, our statistical analysis identified the presence of three significant organizational factors when predicting agency usage in the context of rural businesses. We found that the presence of multiple user groups – when combining two or more of the distinctive variables identified – partially explained the relationship between the type of agencies and their usage by business owners. In the remainder of this section we will summarize the inferences drawn from this analysis.

First, cross tabulation, chi-squared tests, and logistic regression identified the most significant predictors of agency usage. The size of the firm, degree of localization and existence/usage of business and succession planning were all found to be significant. Moreover, the companies with more employees were inclined to use the agencies. In particular, the use of agencies among businesses with only one employee (owner only) was relatively lower than the other two groups. The interviews carried out during the information sharing sessions indicated that finding time to meet or contact the agencies was the major reason inhibiting agency usage. As one business owner mentioned,

“…We are too busy running our business and do not have any time to meet agencies… they are only open during business hours….

Those who were using agencies were often only sought out local agencies such as the Chamber of Commerce and municipal services. Although previous studies (see Konsti-Laakso, Pihkala, and Kraus 2012) indicated that the support agencies can facilitate the value creation through workshops and networking events, the results indicate that the business owners prefer more intimate interactions with the support agencies. Many business owners preferred to have one-on-one support as opposed to accessing assistance services through a website or over the phone. Although the agencies included in this study were providing a full range of financial and consulting support, very few had local offices in the communities. If a rural owner required one-on-one help they were expected to travel more than 200 km to meet the agency personnel in the major cities of either Calgary or Edmonton. Many indicated travel is not an option, as they would be required to close their businesses for at least one day. In addition, some communities had difficulties in accessing broadband internet, thereby limiting their ability to receive assistance from the agencies that were only active online beyond city borders. These results are consistent with other studies carried out in Canada (Jagoda and Herath 2010; Jagoda 2010).

The degree of localization had a positive effect on agency usage for the companies studied in this sample. Localized firms used agencies more frequently than non-localized companies. This was significant; the companies who acted as branch or sales office are likely to have an internal support system. As one business owner for a branch office outlined:

… we are getting enough support from our main office so we do not believe other agencies can provide substantially higher value…

In addition, these companies had a limited reach beyond their geographic area. They were not likely to expand into neighboring communities due to both financial and human resources limitations.

Interestingly, owners with business plans sought agency support more than others, reflecting their intention to expand. This reflects the literature regarding business plan preparation and agency usage patterns; agencies are a key resource in business plan preparation, which is perceived as most worthwhile by those launching or expanding a venture (Castrogiovannie 1996; Honing and Karlsoon 2004; Read and Sarasvathy 2006). Comprehensive analysis of the data collected in this study confirms the findings of the previous studies that most business owners sought help in building debt capital, website development, and marketing (Audet et al. 2007; Wyckham, Wedley, and Culver 2001). Many business owners expressed their desire to seek external advice through agencies, yet had a limited understanding of the services provided. The major reasons cited for bypassing the agencies confirm the findings of the previous studies such as ill-fitting for their business needs (Curran and Blackburn 2000; Dalley and Hamilton 2000), lack of confidence in the agency (Audet and St-Jean 2007), complexity of the process (Young 2002; Dalley and Hamilton 2000), and lack of awareness of the agencies (Curran and Blackburn 2000).

Our research also revealed interesting findings surrounding the use of succession planning. The results indicated that companies who had succession planning in effect were less likely to use the agencies. This may appear surprising at first glance, as a considerable number of business owners were more than 50-years old and were eager to benefit from their profits. A majority indicated that their children had little interest in continuing the business as they preferred to move to bigger cities in the province. One business owner summarized:

…my children went to a college in Calgary and do not want to come back… I have no one in the family to take over this business and am looking for someone to sell this business to…

However, a deeper analysis using qualitative information points to two possible reasons. First, these companies are likely to be family owned, suggesting that they may be more secretive. Second, the current owner/manager is deferring responsibilities to the next generation leader, thereby not actively seeking improvement. The decision tree analysis confirms the above findings and indicates that the firm size is the major factor in predicting agency usage, while degree of localization and existence of business and succession ranked as second and third, respectively.

Next, a cluster analysis identified four different user groups based on the type of agencies they used in the business development process. The analysis of variances revealed that the differences between these clusters can be explained by the size of the organization (as represented by number of employees), gender of business owner and, to a lesser extent, by the use of a business plan to guide operations. The results give a clear indication of usage patterns and the type of agencies business owners prefer to use. Distinct characteristics of each cluster are explained below.

The first cluster contains firms that did not seek help from any agency. This cluster can be referred to as “non-users” and is dominated by male owners who do not have business or succession plans to guide their operations. Further investigation of their future plans suggests that they wish to maintain the status quo with little interest in expansion. Most of the business owners in this category intend to secure their profits by transferring the business to family members or through divestment.

The second cluster consists of firms that appear to be open minded, yet have limited contact with local agencies such as the Chamber of Commerce, the municipality, and to a lesser extent, Community Futures. This cluster can be referred to as “regional users”. These agencies have a local office either in the community (Chamber of Commerce and City) or a nearby community so that business owners may easily seek personalized assistance. Although there are more male owners than female, the difference in gender is not significant. About half of the business owners in this category used all three agencies, which may reflect a “local problems–local solutions” trend. Many of the business owners we met with during workshops indicated that they only trust agencies with staff living in the local community. As one business owner mentioned:

…if something goes wrong we can go back and ask for solution… we do not believe the consultants in Edmonton or Calgary understand rural businesses…

It is possible that if other agencies commit to a physical presence in local communities, as opposed to a solely web-based presence, this cluster may be expanded.

The third cluster consists of businesses that seek help from agencies and perceive their services as essential and inherently local. We can refer to this faction of businesses as “ultra local”. A majority of businesses in this category used exclusively Chamber of Commerce and/or City services and rarely used other agencies. Most of these companies only attended services offered annually (e.g. workshops) by the City or Chamber of Commerce. Some of the business owners indicated that they were only mildly motivated to make use of these services in an effort to “get something” from tax dollars and/or subscription fees.

The fourth cluster consists of a small group of businesses that used multiple agencies. This group can be classified as “heavy users”. One of the significant observations regarding this group pertains to the higher number of female business owners over male business owners. When compared to cluster 1, the percentage of female business owners is significant. Most of the companies held a business plan that may lead them to seek external help or that may reflect the assistance in planning they received by visiting one of the agencies. Our analysis confirms that most of these business owners are planning to expand their firms, which would likely lead them to seek assistance from agencies.

The results pertaining to the perceived usefulness and resourcefulness of support agencies raise concerns regarding agencies’ ability to provide services that meet the needs and requirements of rural SMEs. Generally speaking, survey participants who accessed agency services expressed disappointment with a majority of the agencies. The strongest level of satisfaction, at approximately 75%, was associated with the Rotary Club or Kiwanis Club, both of which typically focus on volunteer activities and local economic development projects. The two second most popular agencies were Community Futures and the local branch of the Chamber of Commerce, with an average satisfaction rate of 76% and 75% respectively. Both agencies have a regional presence in the rural communities, with Community Futures not offering services to urban venture owners. The results do not support the findings of Audet and St. Jean (2007) and Curran and Blackburn (2000), both of whom suggested that once business owners experience venture support agencies they are much more likely to find them useful. This discrepancy may be attributed to earlier studies’ tendency to analyze the perceived fit between SME owner needs and agency services. Our study focuses on the level of satisfaction with the agency services, rather than the fit between agency services and owner needs.

Of special interest to this specific subject area are the weak results for three agencies that have a national mandate to serve both urban and rural SME owners, with offices in each province across Canada. The Business Link, Canadian Youth Business Foundation, and Alberta Women’s Enterprise each received a satisfaction rating of less than 60%, at 56%, 54% and 50% respectively. It should be noted that each of these agencies was not widely used, with only 5% to 7% of survey participants accessing their services. It raises the question of whether rural entrepreneurs may not be seeking assistance from these agencies due to negative feedback via word of mouth from family and business associates regarding their experiences. Research by Shields (2005) suggests that word of mouth heavily influences the use of agencies; if so several years of negative usage would hinder the appeal of agencies. User satisfaction for the other agencies ranged from 60% to 65%, indicating that services were adequate. While the limited presence in rural communities could provide some explanation for the reduced levels of satisfaction, it does not explain the satisfaction range for agencies with centralized services. For example, seven of the twelve support agencies have offices in urban centers with web and phone support for rural ventures. However, while the overall level of satisfaction for these agencies is poor, ranging from 54% to 65%, some of the agencies were able to perform their duties more effectively, despite their city-based centralized services.

The results are significant for both the agencies and their funders with regards to how they communicate their services to the broader rural SME community, and in the effectiveness of their service delivery. Several of the agencies must overcome a negative perception held by rural users, which in turn could restrict the utilization of their services. It is unlikely that agencies rated 60% or lower would receive recommendations from users, thereby contributing to reduced usage. All of the agencies included in the study have a mandate to serve rural SME constituents; those that have not successfully reached SMEs in need of their services could benefit from a review of their communication and operational practices.

The results also raise concern regarding the sustainability and expansion capability of rural SME owners. Survey results clearly identified that owners required training to enhance their operational effectiveness in finance, marketing, IT, and planning, as well as obtaining financial support for expansion. Barriers to growth exist and will continue to exist until the agencies modify their communication strategies, their range of services, or their methodology for providing services. In order to improve the usage of effectiveness agencies could deploy a few strategies. First, the clear identification of the services needed by the rural business owners is required (Dalley and Hamilton 2000). This could be done using a detailed survey of needs through focus groups or interviews. Second the services offered by the agencies need to be tailored to the needs of the business owners. The “one-size-fit all” philosophy will create lack of confidence in the agency and program (Curran and Blackburn 2000). Improving the experience of the business owners will not only help to increase the trust and understanding of the agencies and programs offered by them (Woodhouse 2006) but also promote the agencies through their networks (Audet et al. 2007). Third, the agencies need to rethink the delivery mode of their services to make them more user-friendly. While the modern information and communication technologies are useful in covering a large area (Jagoda 2010), many business owners have yet to take the advantage of the online services due to complexity of application process (Young 2002) or lack of knowledge (Jagoda 2010). One of the ways to address to this problem is to use more local offices or field-agents in local communities (Dyer and Ross 2008).

5 Conclusion

This paper examines the utilization and perception of venture support agencies as well as local community agencies by rural SME owners as determined through a BR&E research project conducted in the province of Alberta, Canada. The results indicated that agency usage can be effectively predicted by firm size, degree of localization, and use of planning. The key findings also indicated that while SME owners could benefit from training and mentoring, the majority did not access the services provided by support agencies. Further, when the SME owners did approach the agencies for assistance the majority of the agencies whom provided services were perceived to be unsatisfactory. Those owners who sought assistance typically tried more than one organization, either for the same issue or additional issues. Cluster analysis provided clarity regarding usage patterns based upon growth expectations and size. The usage pattern indicated that local organizations, such as the municipal office and the Chamber of Commerce, were visited most frequently, with the services of the Community Futures offices being the second most frequently visited agency. High rates of usage reflected the growth expectations of firms and were tied to the preparation of business plans or expansion planning. However, the lowest levels of usage and satisfaction were recorded for agencies funded by the provincial or federal government that supposedly have province-wide mandates but centralized services. The lack of usage could be explained by the narrower mandate for some of the services; however, it does not entirely explain poor user satisfaction. The limited utilization of many agencies that could potentially enhance SME venture viability and growth, and the weak perception of service effectiveness suggests that a review of agency communication methods and services could be beneficial. The findings are similar to other studies previously carried out in Canada, providing additional insight regarding SME owner perception and utilization of support agencies. Previous studies focus primarily on the funding functions of support agencies, whereas our study included agencies and organizations providing varied services.

Results could be further clarified using businesses in other provinces in Canada and the United States. In-depth interviews with SME owners would provide insight into the core reasons behind the dissatisfaction with services provided by many agencies, as well as the drivers for higher levels of satisfaction. Such interviews might also provide details regarding the decision process by which users select agencies, and whether the issue that precipitated the visits or interactions with support agencies was eventually addressed through the agency’s services. Future research will include sharing the findings of this study with representatives from the agencies, as well as funding organizations, such as the provincial and federal Canadian Government, and conducting BR&E studies in other Canadian provinces.

References

Arikan, A. 2010. “Regional Entrepreneurial Transformation: A Complex Systems Perspective.” Journal of Small Business Management 48 (2):152–73.10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00290.xSearch in Google Scholar

Audet, J., and E. St-Jean. 2007. “Factors Affecting the Use of Public Support Services by SME Owners: Evidence From a Periphery of Canada.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 12 (2):165–80.10.1142/S1084946707000629Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, R. J., and P. J. A. Robson. 1999. “The Use of External Business Advice by SMEs in Britain.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 11:155–80.10.1080/089856299283245Search in Google Scholar

Besser, T. L., N. Recker, and M. Parker. 2009. “The Impact of New Employers from the Outside, the Growth of Local Capitalism, and New Amenities on the Social and Economic Welfare of Small Towns.” Economic Development Quarterly 23 (4):306–16.10.1177/0891242409340899Search in Google Scholar

Birch, D. 1987. Job Creation in America. New York, NY: Free Press/MacMillan Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Boothroyd, P., and H. C. Davis. 1993. “Community Economic Development: Three Approaches.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 12:230–40.10.1177/0739456X9301200307Search in Google Scholar

Brinkmann, J., D. Grichnik, and D. Kapsa, 2010. “Should entrepreneurs plan or just storm the castle? A meta-analysis on contextual factors impacting the business planning–performance relationship in small firms.” Journal of Business Venturing 25:24–40.10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.007Search in Google Scholar

Carrington, C., and L. Zantoko, 2008. Small business financing profiles: Rural-based entrepreneurs. Government of Canada, Small Business and Tourism Branch.Search in Google Scholar

Castrogiovannie, G. J. 1996. “Pre-Startup Planning and the Survival of New Small Businesses: Theoretical Linkages.” Journal of Management 22 (6):801–22.10.1177/014920639602200601Search in Google Scholar

Cothran, H. M. 2006. Business retention and expansion (BRE) programs: Developing a business retention and expansion survey. Food and Resource Economics Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida.10.32473/edis-fe654-2006Search in Google Scholar

Curran, J., and R. Blackburn. 2000. “Panacea or White Elephant? A Critical Examination of the Proposed Small Business Service and Response to the DTI Consultancy Paper.” Regional Studies 34 (2):181–206.10.1080/00343400050006096Search in Google Scholar

Dabson, B. 2003. Supporting rural entrepreneurship. Proceedings of main streets of tomorrow: Growing and financing rural entrepreneurs.Search in Google Scholar

Dalley, J., and B. Hamilton. 2000. “Knowledge Context and Learning in the Small Business.” International Small Business Journal 18:51–60.10.1177/0266242600183003Search in Google Scholar

Darren, L., and L. Conrad. 2009. Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management in the Hospitality Industry. Jordan Hill: Elsevier Linacre House.Search in Google Scholar

Delmar, F., and S. Shane. 2003. “Does Business Planning Facilitate the Development of New Ventures?” Strategic Management Journal 24 (12):1165–85.10.1002/smj.349Search in Google Scholar

Dimitratos, P., S. Lioukas, K. I. N. Ibeh, and C. Wheeler. 2010. “Governance Mechanisms of Small and Medium Enterprise International Partner Management.” British Journal of Management 21 (3):754.10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00620.xSearch in Google Scholar

Drabenstoff, M., and J. Henderson. 2006. “A New Rural Economy: A New Role for Public Policy.” Management Quarterly 47 (4):4–18.Search in Google Scholar

Dyer, L., and C. Ross. 2008. “Seeking Advice in a Dynamic and Complex Business Environment: Impact on the Success of Small Firms.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 13:1–17.10.1142/S1084946708000892Search in Google Scholar

Flora, J. L., G. P. Green, E. A. Gale, F. E. Schmidt, and C. B. Flora. 1992. “Self-Development: A Viable Rural Development Option?” Policy Studies Journal 20:276–88.10.1111/j.1541-0072.1992.tb00155.xSearch in Google Scholar

Gasse, Y., M. Tremblay, T. V. Menzies, and M. Diochon. 2004. La Dynamique et les characteristiques des enterprises emergentes: Les premiers stades de developpement. Annual meeting of Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Quebec City, 5–8 June.Search in Google Scholar

Goll, I., and A. M. A. Rasheed. 1997. “Rational Decision-Making and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Environment.” Strategic Management Journal 18 (7):583–91.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<583::AID-SMJ907>3.0.CO;2-ZSearch in Google Scholar

Good, W. S., and J. R. Graves. 1993. “Small-Business Support Programs: The Views of Failed Versus Surviving Firms.” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 10 (2):66–76.10.1080/21692610.1993.11683547Search in Google Scholar

Green, G. P. 2005. “What Role Can Community Play in Local Economic Development?” In Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century, edited by D. L. Brown and L. E. Swanson, 343–53. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.10.5325/j.ctv14gp32b.32Search in Google Scholar

Green, G. P., A. Fleischmann, and T. M. Kwong. 1996. “The Effectiveness of Local Economic Development Policies in the 1980s.” Social Science Quarterly 77:609–17.Search in Google Scholar

Gulumser-Akgun, A. A., T. Baycan, and P. Nijikamp. 2011. Repositioning rural areas as promising future hot spots. VU University Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Economics.Search in Google Scholar

Honig, B., and T. Karlsoon. 2004. “Institutional Forces and the Written Business Plan.” Journal of Management 30 (1):29–48.10.1016/j.jm.2002.11.002Search in Google Scholar

Industry Canada. 2012. Small Business Quarterly. 14 (1): Small Business Branch.Search in Google Scholar

Industry Canada. 2013. Key Small Business Statistics. Small Business Branch.Search in Google Scholar

Jagoda, K. 2010. “The Use of Electronic Commerce by SMEs.” Entrepreneurial Practice Review 1 (3):36–47.Search in Google Scholar

Jagoda, K., and S. K. Herath. 2010. “Acquisition of Additional Debt Capital by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from Canada.” International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development 8 (2):135–51.10.1504/IJMED.2010.031545Search in Google Scholar

Jay, L., and M. Schaper. 2003. “Which Advisers Do Micro-Firms Use? Some Australian Evidence.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 10:136–44.10.1108/14626000310473166Search in Google Scholar

Konsti-Laakso, S., T. Pihkala, and S. Kraus. 2012. “Facilitating SME Innovation Capability Through Business Networking.” Innovation Capability and Business Networking 21 (1):93–105.10.1111/j.1467-8691.2011.00623.xSearch in Google Scholar

Krasniqi, B. 2007. “Barriers to Entrepreneurship and SME Growth in Transition: The Case of Kosava.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 12 (1):71–94.10.1142/S1084946707000563Search in Google Scholar

Kraybill, Jr. F. 1995. “Retention and Expansion First.” Ohio’s Challenge 8 (2):4–7.Search in Google Scholar

Lyson, T. A., and C. M. Tolbert. 1996. “Small Manufacturing and Nonmetropolitan Socioeconomic Well-Being.” Environment and Planning 28:1779–94.10.1068/a281779Search in Google Scholar