Nanomedicine has its roots deeply in experimental research: the scanning microscopes have opened the door to nano scale analysis, nanomaterials including fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, and lipidic and polymeric nanomaterials were created as novel constructive building blocks, and the combination of nano-fluidics, single molecule/nanoparticle photonics as analytic tools have gone hand in hand to create. Starting in basic, experimental science, this very productive and interdisciplinary field of nanomedicine (1) has rapidly progressed towards preclinical science and clinical application and is strongly interacting with related sciences, e.g., toxicology, stem cell therapies, therapeutic gene therapy, and the clinical sciences.

Nanomedical materials are in most cases supramolecular constructs built up from multiple building blocks that belong to different classes, e.g., proteins and synthetic polymers, lipids and nucleic acids, metals with a protein corona, to mention only a few. These combinations deliver an impressive range of innovative functionality and novel properties that are appealing for preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic application.

While the experimental productivity in the field of such new materials is overwhelming, solid and systematic understanding of the field is lagging behind. This can be explained on one side by the fact that nanomedicine is a young scientific field, and on the other side by the challenge that the large domain of small molecules, combined with the large domain of proteins, further combined with the large domains of polymers as well as inorganic materials forms a huge combinatorial universe, representing a daunting challenge to a specialist focusing on one specific method or material, following the evolution of scientific specialization in the last century.

Computational approaches to each individual component exist in principle, but are rarely combined:

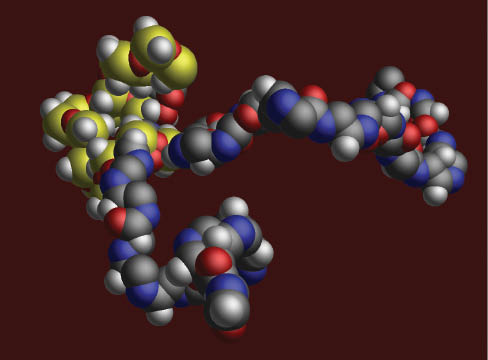

‘Ab initio’ simulation of small molecules (although still challenged by seemingly simple, but as it now turns out, challenging problems like the properties of water and its interaction with other molecules), combined with modeling of polymers (Figure 1);

computational proteomics, although still limited in its predictive power for key nanomedical questions like the structure and interaction of membrane proteins with macromolecules and particles;

computational approaches to cell biology and systems biology, shedding light on the cellular processes that can be triggered by cell–nanomaterials interaction

computational toxicology, e.g., by prediction of the interaction of small molecules with key pathways responsible for drug toxicity;

computational pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling;

disease modeling based on individual characteristics, a prerequisite for a personalized medicine

prognostic modeling for disease outcome and individual disease cost-effectiveness;

data mining and ‘big data’ approaches to enhance our understanding of the large datasets produced daily in our labs, clinics, and administration departments, which could be of benefit for the medicine of the future.

Computational modeling of triblock copolymer composed of oxazolines and siloxane. Block copolymers are an important building block of complex nanosystems (4).

Publications describing application of such computational tools to nanomaterials (2), composite analytic systems (3) and the interdisciplinary challenges of nanomedical progress have started to appear, but are still far too sparse to render the computational technologies a factor that significantly accelerates the translation of nanoscience towards real-world applications.

Such a field, which might be called “Computational Nanomedicine” is therefore almost inexistent at the current time, but sorely needed. We therefore challenge the computational science community to address this gap, to interact with experimental, preclinical and clinical scientists to define needs and to contribute solutions that deepen our understanding at the fundamental level, that broaden our understanding of our experiments, and that help us to predict nanomaterials characteristics and nano-bio interaction, up to therapeutic or toxic effects of materials and impact on disease course and cost effectiveness of such approaches.

This journal welcomes submissions that use computational approaches to advance the field, in the expectation that this will accelerate our progress towards a personalized, highly effective, innocuous, and cost-effective medicine of the future through the application of nanomedicine (5).

About the author

References

1. Mollenhauer J. Nanomedicine – interdisciplinarity par excellence. Eur J Nanomedicine 2013;5:1–2.10.1515/ejnm-2013-0008Search in Google Scholar

2. Klein J. Probing the interactions of proteins and nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007;104:2029–30.10.1073/pnas.0611610104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Zimmermann M, Delamarche E, Wolf M, Hunziker P. Modeling and optimization of high-sensitivity, low-volume microfluidic-based surface immunoassays. Biomed Microdevices 2005;7:99–110.10.1007/s10544-005-1587-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Brož P, Benito SM, Saw C, Heider H, Pfisterer M, Marsch S, et al. Cell targeting by a generic receptor-targeted polymer nanocontainer platform. J Control Release 2005;102: 475–88.10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Hunziker P. Comprehensive targeting: the avenue to a personalized, highly effective, innocuous, and cost-effective medicine of the future. Eur J Nanomedicine 2013;5:3–4.10.1515/ejnm-2013-0014Search in Google Scholar

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Publication ethics and publication malpractice statement

- Editorial

- Nanomedicine enabled by computational sciences

- What’s up in nanomedicine?

- News from the European Foundation for Nanomedicine (CLINAM)

- Review

- Novel radioisotope-based nanomedical approaches

- Original Articles

- Silver nanowires as prospective carriers for drug delivery in cancer treatment: an in vitro biocompatibility study on lung adenocarcinoma cells and fibroblasts

- Plasmid linearization changes shape and efficiency of transfection complexes

- Opinion Paper

- Why healthcare open innovation is failing for nanomedicines

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Publication ethics and publication malpractice statement

- Editorial

- Nanomedicine enabled by computational sciences

- What’s up in nanomedicine?

- News from the European Foundation for Nanomedicine (CLINAM)

- Review

- Novel radioisotope-based nanomedical approaches

- Original Articles

- Silver nanowires as prospective carriers for drug delivery in cancer treatment: an in vitro biocompatibility study on lung adenocarcinoma cells and fibroblasts

- Plasmid linearization changes shape and efficiency of transfection complexes

- Opinion Paper

- Why healthcare open innovation is failing for nanomedicines