Abstract

Existing studies are not clear about the process of building organizational resilience that is crucial for the performance of firms. To tap into this still unexplored terrain, the aim of this qualitative study is to shed more light on how organizational resilience is built amid challenges from a perspective of path constitution. We present a single, longitudinal case study of the dynamic development of China Light & Textile Industry City Group, the leading textile trading platform operator in China. The results show that the process of organizations building resilience could be regarded as a process of organizational path constitution. Therefore, a theory model of the organizational resilience building was developed, which expanded the applicable scope of the path constitution theory. Further, this study deconstructed the mechanism of resilience building based on the interaction between opportunity space and organizational learning, which contributes to the organizational resilience literature and enriches the body of qualitative research in corporate management. Additionally, our findings provide practical implications for companies to maintain resilience and sustainable performance.

1 Introduction

In a dynamic world, it is imperative for companies to survive and thrive amidst continuous and unexpected challenges (DesJardine et al., 2019; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Nyaupane et al., 2021). Organizational resilience is considered to be the ability of enterprises to recover fast from turbulence and maintain sustainable performance (Anwar et al., 2021; Maghbouli & Pourhabib Yekta, 2021; Sinha & Edalatpanah, 2023) by mobilizing and accessing the resources available (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Linnenluecke, 2017), which emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the organization and the environment (Palanikumar et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2017). This concept is often viewed as a desirable characteristic for organizations to cope with environmental discontinuities and to seize opportunities emerging from the changing environment (Hall et al., 2017; Jia et al., 2020; Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007). Thus it has recently gained increasing momentum in economic and business science and practice (Clément & Rivera, 2017; DesJardine et al., 2019; Hillmann, 2021; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Limnios et al., 2014; Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017), especially in practice of firm performance.

Further, from a process perspective, it is of great significance to examine how organizational resilience is built (Barin Cruz et al., 2016; Powley, 2013; Sun et al., 2011; Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007), which, unfortunately, is not sufficiently comprehensive. The existing literature focuses primarily on the role of internal organizational behaviors or factors (Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017), such as leadership behaviors (Teo et al., 2017), trainings and HR development (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Luthans, 2002), network (Barasa et al., 2018; Cotta & Salvador, 2020), innovation practice (Dragicevic et al., 2023), and psychological capital (Fang et al., 2020). However, there remains scope for additional research about other possible aspects beyond the organizational level. In this case, devoting attention to the interactions between organizations and their environment (Williams et al., 2021) is helpful for gaining a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanism of organizational resilience building and providing a practical reference for companies about how to keep a sustainable performance.

Integrating the theories of “path dependence” and “path creation,” the path constitution theory considers organizational path evolution as a process that combines the “emergent” nature of path dependence (Arthur, 1994; Schreyögg & Sydow, 2011; Sydow et al., 2009; Vergne & Durand, 2010) and the “conscious behavior” of path creation (Garud et al., 2010; Sydow et al., 2012). According to this theory, organizational learning and opportunity space serve as two key elements which are the foundations of this theory. Organizational learning, as a form of conscious organizational actions and a key factor influencing organizational performance and survival (Argote et al., 2003; Kane & Alavi, 2007), refers to observing, evaluating, and acting on stimuli from within and outside the organization in a cumulative, interactive, and purposeful fashion (Brown & Starkey, 2000; March, 1991). Organizational learning helps organizations adapt to the changing environment and is the premise of organizational path adjustment. On the other hand, opportunity space refers to the perceived range of resources and knowledge available to an organization in the environment, which provides the possibility for organizational learning and path development (Kornish & Ulrich, 2011). Therefore, the organizational path constitution is an outcome of the interaction between organizational learning and opportunity space.

However, less attention has been devoted to examining how organizational learning and opportunity space play a role together in affecting the organizational abilities or performance, specifically the organizational resilience. Scholars have investigated opportunity spaces (Jing & Benner, 2016; Kornish & Ulrich, 2011; Kurikka et al., 2022) or organizational learning (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Dodgson et al., 2013; Kane & Alavi, 2007; Tortorella et al., 2020; Zhang & Zhu, 2019) in explaining organizational development (e.g., technological improvement, green innovation, and workplace relationships), respectively. Nevertheless, current studies have not explored how these two elements interact with each other, and what is the influence of this interaction on organizational performance. In other words, it is not clear how resilience is influenced by the process of path constitution.

In this study, we focus on the role that the process of path constitution plays in explaining organizational resilience building for sustainable performance. To this end, we attempted to investigate how organizational resilience is built under different challenges through path constitution, with a longitudinal case study of the development of China Light & Textile Industry City Group Co., Ltd (LTC), the largest textile trading platform operator in China. Our study makes two main contributions to current literature. First, our findings showed that the process of organizations to build resilience for sustainable performance could be regarded as a process of organizational path construction, which expanded the applicable scope of the path constitution theory. Second, this study deconstructed the mechanism of organizational resilience building based on the interaction between opportunity space and organizational learning (two key elements of path constitution theory), which contributes to the organizational resilience literature and enriches the body of qualitative research in firm operating.

2 Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis Framework

2.1 Organizational Resilience

The research on the process and mechanism of organizational resilience has become a widely discussed topic in economic and business management science and practice (Clément & Rivera, 2017; DesJardine et al., 2019; Hillmann, 2021; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017), especially in the field of firm performance (Anwar et al., 2021). It is regarded as a promising perspective on how organizations survive and thrive amidst crisis or turbulence (DesJardine et al., 2019; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021). In this study, organizational resilience refers to the ability of an organization to maintain functioning and sustainable performance when faced with turbulence and challenges by mobilizing and accessing the resources around (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021). Therefore, in the process of resilience building, the dynamic interaction between the organization and the environment (Williams et al., 2017) is emphasized.

Research on organizational resilience has been highly context-dependent (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Linnenluecke, 2017). For instance, scholars have investigated organizational resilience to crisis scenarios or life-threatening events (Howe et al., 2023; Mithani, 2020), such as supply chain disruptions (Cotta & Salvador, 2020; Ghasemi et al., 2022; Islam Mim et al., 2022; Klibi et al., 2010; Urciuoli et al., 2014; Voss & Williams, 2013), extreme climate change (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2013; Tisch & Galbreath, 2018; Wedawatta & Ingirige, 2012; Winn & Pogutz, 2013; Winston, 2014), and the COVID-19 global pandemic (Groschke et al., 2022; Hadjielias et al., 2022; Su et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2023; Zhang & Qi, 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Obviously, organizational resilience is preceded by internal or external challenges (crisis or turbulence) (Liu et al., 2023) and is built by managing them (Linnenluecke, 2017). Furthermore, it is essential to address how it is built (Barin Cruz et al., 2016; Powley, 2013; Sun et al., 2011; Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007) encountering challenges, which, unfortunately, is not sufficiently explored.

The existing literature on organizational resilience building process focuses mainly on how internal organizational behaviors or factors (Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017) affect organizational performance. For example, a number of studies have demonstrated that organizational factors such as leadership behavior (Teo et al., 2017), trainings and HR (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Luthans, 2002), network (Barasa et al., 2018; Cotta & Salvador, 2020), and psychological capital (Fang et al., 2020; McCoy & Elwood, 2009) contribute to resilience building. However, organizations are inherently dependent on the broader social ecosystem in which they are located (Williams et al., 2021), and resources outside the organizations are also critical for improving organizational resilience. Therefore, there is still room for further investigation into other possible aspects beyond the organizational level. Moreover, studying the influence of environmental resources on organization and the dynamic interaction between organization and environment (Williams et al., 2021) will help us to further reveal the internal mechanism of organizational resilience and sustainable performance.

2.2 Path Constitution

Synthesizing the theories of “path dependence” and “path creation,” the path constitution theory regards organizational path development as a process that combines the “emergent” nature of path dependence (Arthur, 1994; Schreyögg & Sydow, 2011; Sydow et al., 2009; Vergne & Durand, 2010) and the “conscious behavior” of path creation (Garud et al., 2010). This theory holds that path constitution is a continuous process (Meyer & Schubert, 2007) in which there is the role of emergent environment that occurs naturally and is not deliberately planned, as well as the role of strategic control and deliberate action (Sydow et al., 2020). Accordingly, actors recognize that they cannot fully control the path development, but they can to some extent influence it through conscious behavior. Besides, the process of path constitution can be divided into different phases: path generation (path creation resulting from conscious actions or path emergence resulting from random events), path continuation (path persistence or path extension), and path termination (path breaking or path dissolution) (Meyer & Schubert, 2007). Accordingly, the organizational conscious actions and the emergent environment are both considered significant in the constitution of organizational paths, thus providing a possible perspective to explain how the organizations achieve resilience.

In this theory, organizational learning and opportunity space are two key elements. Organizational learning refers to observing, evaluating, and acting on stimuli from within and outside the organization in a cumulative, interactive, and purposeful fashion (Brown & Starkey, 2000; March, 1991). It is a typical form of conscious actions and a key factor influencing organizational survival and performance (Argote et al., 2003; Grant, 1996; Kane & Alavi, 2007). While opportunity space indicates the perceived range of available options (i.e., resources and knowledge) for organizational variance (Kornish & Ulrich, 2011), which arise from the resources and knowledge accumulated in the environment (Alvarez et al., 2010; Jing & Benner, 2016). In the process of path constitution, opportunity space not only provides existing alternative resources and opportunities for organizational managers to make strategic decisions, thus forming self-reinforcing mechanisms and path persistence, but also provides resources and knowledge for managers to learn and consciously deviate, thus forming new path creation. Instead of passively accepting and utilizing existing resources and knowledge, organizational managers consciously adopt different organizational learning models and actively influence opportunity space (Sydow et al., 2020). Consequently, in an evolutionary view (Kurikka et al., 2022), through the interaction between the two, organizational paths evolve gradually, therefore, building organizational resilience. In this sense, we could regard the resilience building as a process of path constitution as a response to environmental turbulence.

More specifically, in the organization literature, there are two modes of learning: exploration and exploitation. On the one hand, exploration engages organizations in “search, variation, risk-taking, experimentation, and innovation” for new knowledge to improve flexibility (Holmqvist, 2004; Lavie et al., 2010; March, 1991), in which the opportunity space of the organization is often expanded (Beckman et al., 2004). On the other hand, exploitation enhances productivity and efficiency through “refinement, choice, selection, implementation and execution,” building on current knowledge base (Holmqvist, 2004; Lavie et al., 2010; March, 1991), where the opportunity space is often constrained (Lavie et al., 2010; Ossenbrink et al., 2019). However, the difference between exploration and exploitation is often a matter of degree rather than kind. In this case, exploration–exploitation should be viewed as a continuum rather than a choice between discrete options (Lavie et al., 2010). That is to say, there is a cycle of exploration–exploitation (Rothaermel & Deeds, 2004). The first time an organization experiments or innovates, it enacts exploration, but as the organization repeats these experiments or the application of newly acquired knowledge, it develops exploitative routines. Consequently, exploration evolves into exploitation (Brunner et al., 2008; Lavie et al., 2010), and vice versa.

To date, how organizational learning and opportunity space play a role together in affecting the organizational resilience or performance still remains unexplored. Most studies have investigated opportunity spaces (Jing & Benner, 2016; Kornish & Ulrich, 2011; Kurikka et al., 2022) or organizational learning (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Dodgson et al., 2013; Kane & Alavi, 2007; Tortorella et al., 2020; Zhang & Zhu, 2019) in explaining organizational development (e.g., technological improvement, green innovation, and workplace relationships), respectively. For example, some studies have shown that organizational learning drives organizational resilience and sustainable business performance (Borazon et al., 2023; Hadi & Baskaran, 2021). Mao et al. (2023) have demonstrated that organizational learning has a moderating effect on the relationship between slack resources and organizational resilience. Kim and Park (2020) have proved organizational learning’s positive effects on organizational effectiveness and next outcomes. Jing and Benner (2016) have proposed that the opportunity spaces of organizations interact with organizational change efforts, thus influencing organizational survival. To sum up, current studies have not precisely investigated the influence of this interaction on the process of path constitution and organizational performance.

2.3 Theoretical Analysis Framework

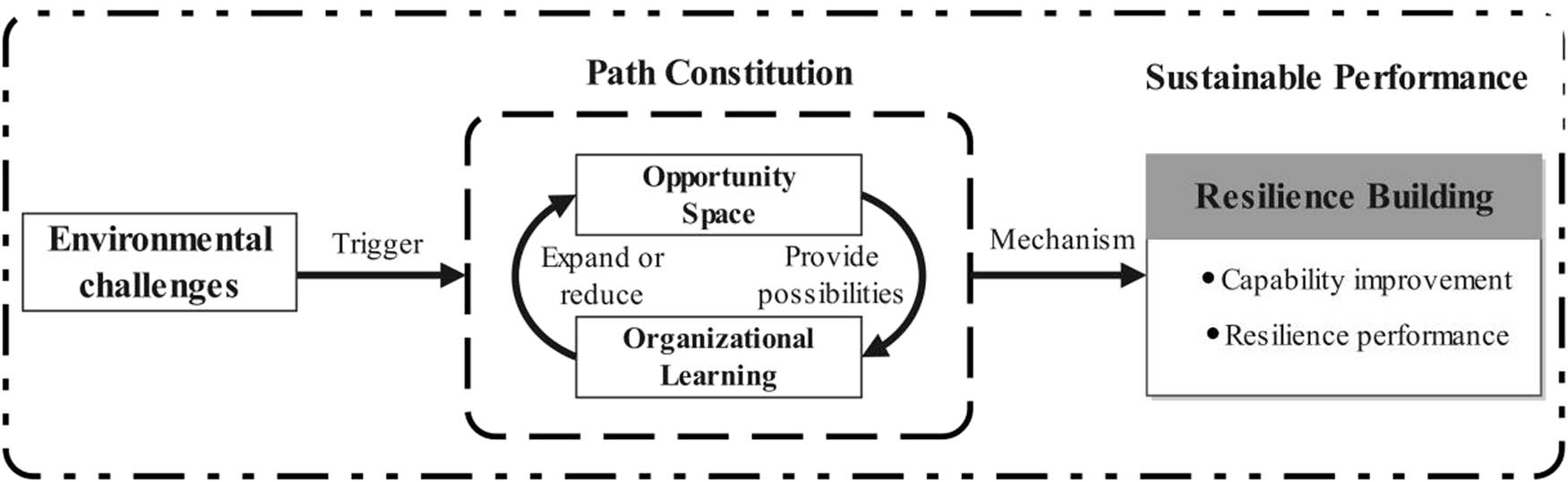

Considering the core theoretical viewpoints of the existing literature, we sorted out the analysis framework of “path constitution - resilience building” (as presented in Figure 1), surrounding the research question of “how should organizations build resilience through path constitution when faced with challenges” with a case study at the firm level. Specifically, different challenges prompt organizations to take strategic actions (i.e., organizational learning). At different stages, the interaction between organizational learning and opportunity space leads the path constitution process progressively, building resilience as a consequence of firm’s sustainable performance step by step.

Theoretical analysis framework.

3 Method

In this study, we opted a longitudinal single case study design to investigate the organizational resilience building process through path constitution. This setting is suitable for exploring our research question, because (a) the aim of this study is to deconstruct the process of organizational resilience building, which is to answer the “how” questions, while the research question can be presented in a more vivid and detailed fashion in case studies (Eisenhardt, 2020), (b) as this study focuses on process phenomena, a single case study is ideal for providing a detailed account of the complexity of the latter (Langley et al., 2013), and (c) longitudinal case studies are useful for comparing how organizations evolve and change at different phases (Van de Ven & Huber, 1990) to derive the inner patterns of organizational resilience development.

3.1 Case Selection

In this study, we adopted theoretical sampling to select LTC as the research case for three reasons. First, the typicality of the cases (Pettigrew, 1990) was considered. As a company based on textile specialized market in China, it has maintained the leading position in the textile trading sector, which is typically a success compared with competitors who failed to stay resilient in the midst of turbulences. Second, the case is inspiring (Eisenhardt, 2020). It has continued to prosper amid complicated and changing economic situations over the past 30 years in China and globally, inspiring different types of organizations, especially peer companies, to cope with adversities and maintain well operated. Third, the data continuity was considered. LTC has gone through different stages, which showcased the dynamic mechanism of organization resilience. Fourth, our study was supported by the key interviewees, and therefore had access to important archival material, which contributed to the integrity and continuity of data sources.

3.2 The Case

Reviewing the history and current activities of LTC would help analyze its dynamic process of resilience building and well performing. LTC was established in 1993 in Keqiao (a district in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China). It is mainly engaged in running a textile specialized market, an online–offline textile trading platform, and has businesses in logistics and exhibition service for textile trading. The total construction area of the offline market is more than 1.29 million square meters, with more than 20,000 shops, more than 33,000 traders, daily traffic of 100,000 visitors, trading more than 50,000 kinds of textiles with 192 countries (regions) around the world. At present, this market is the largest platform for textile trading in Asia, where a quarter of the world’s textiles are traded every year (the turnover of the online–offline market is presented in Figure 2).

Specialized market turnover of LTC from 2012 to 2021. Source: Data were derived from the China Commercial Circulation Association of Textile and Apparel.

From the very beginning, LTC was the first path-creator to start operating textile specialized market (i.e., building, leasing, and management and service of stores within the market) in the sector. LTC started the first unified and standardized physical market to provide suppliers, traders, and buyers with a public platform to achieve the industrial economies of scale. As LTC successively expanded its market scale and submarkets, the market soon became the largest textile distribution center in China, benefitting all the participants in textile trading. However, starting in 2000, the company faced two major challenges within the sector.

In the first stage, several competitors in other regions of China followed LTC’s step and establish textile specialized markets one after another, attracting buyers and sellers from LTC’s market, which “crowded out its domestic market share.” Besides, due to a lack of experience, LTC was faced with management issues which damaged the interests of many participants. However, LTC put effort into addressing the emerging challenges by exploiting knowledge and resources on specialized market management and business expansion to maintain its leading position.

In the second stage, with the transformation and upgrading of China’s traditional textile and dyeing industry in 2010s, LTC was also beginning to face challenges of transformation and upgrading. On the domestic front, LTC’s management mode could not match the new business philosophy and new trend of diversified and personalized consumption. On the international front, LTC was in fierce competition with enterprises from Southeast Asian countries. To avoid a path lock-in of operating offline specialized markets due to product homogeneity and low-cost competition and to adapt to the new trend in the sector, LTC began to explore a rearrangement of strategy and business units. As a result, LTC had become a well-known competitive high-level international platform of textile trading.

By examining how the firm overcame challenges to stay well operating in the two phases, we uncovered that long-term success is profoundly influenced by the effective interaction of organizational learning in various businesses and opportunity space provided by its stakeholders, such as suppliers, traders, buyers, and local government. (LTC’s business divisions and its relationship with stakeholders are presented in Figure 3).

Business divisions of LTC and its relationship with stakeholders.

3.3 Data Collection

To arrive at a thorough understanding of how LTC built resilience through path constitution facing with adversities over time, we employed a variety of data collection approaches, such as on-site interviews, direct observation, and archival data (as presented in Tables 1 and 2) to ensure that the research information and sources complemented and cross-validated each other (Yin, 2013).

Interview content and coding

| Roles | Interviewees | Code | Content | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-makers | Chief executives at each stage | F1–6 | Development process of LTC, including strategies, scope of business, management, international marketing, adversities and actions, achievements, and typical events in each phase, etc. | 6 |

| Senior managers | F7–21 | 15 | ||

| Local policy-makers | Local governmental chief leaders and officers | F22–33 | Various aspects of policy implementation, which are helpful for the development process of LTC, and LTC’s achievements in each phase, typical deeds, and market management | 12 |

| Important groups relevant with LTC | Representatives of local associations or chambers of commerce in textile sector | F34–43 | Establishment history of associations and chamber of commerce, internal management, scope of functions, and relations to LTC | 10 |

| Traders in the specialized textile market | Domestic traders engaged in domestic trade | F44–51 | Entrepreneurial stories, relations with LTC, strategic management, risk management, Internet +, industrial transformation and technological innovation, corporate social responsibility, etc. | 8 |

| Domestic traders engaged in international trade | F52–55 | 4 | ||

| Foreign businessmen | F56–65 | 10 | ||

| Suppliers of textile products | Suppliers of textiles | F66–76 | 11 | |

| Fashion and creativity entrepreneurs in textile sector | F77–82 | 6 | ||

| Science and technology entrepreneurs in textile sector | F83–89 | 7 | ||

| Witnesses and documentarians | Local press and media | F90–97 | Development of LTC, industrial transformation and development and technological innovation, Internet, property rights protection and brand building, development of e-commerce platform, etc. | 8 |

| Writers | F98–100 | 3 |

Note: All the members of local associations or the chamber of commerce in the textile sector are traders or suppliers in the specialized market.

Secondary data sources

| Data sources | Material | Code | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Articles | News articles | S 1n | 30 |

| Relevant articles on platform of local government departments | S 2n | 16 | |

| Relevant articles on the official platform of LTC | S 3n | 20 | |

| Relevant articles on industry Publications | S 4n | 35 | |

| Archival data | Firm White Paper, Firm Five-Year Plan, Firm handbook, Firm Annual Report | N n | 10 |

| Observation | Fashion Week, Textile Expo, World Textile Merchandising Conference (both online and offline) | T n | 4 |

First, we conducted two rounds of on-site interviews (at least 2 h each) with a total of 100 key participants and witnesses of the development of the firm (as presented in Table 1). These interviewees are current and former organizational relevant members in various roles at different hierarchical level who were involved in the firm’s resilience building activities. From March to September 2021, we visited the company and its closely related institutions (relevant industry associations/institutes and local chambers of commerce, foreign chambers of commerce, news media, etc.) to conduct interviews. We executed the semi-structured interviews, mainly focusing on the topics of development process of the firm, key events and important strategic measures, and outcomes. Additionally, to avoid bias in the interviews, we recorded the interviews and transcribed them into oral documents within 24 h, and re-confirmed with the narrators, and finally arranged them into written materials.

Second, by conducting direct observation, we correlated the abstract interview content with the actual context and verified each other. We visited the company and the textile market under its jurisdiction. We also attended the Fashion Week, textile Expo, World Textile Merchandising Conference (online and offline), and other exhibitions. Meanwhile, we obtained observation records and collected 2G of electronic data. Additionally, our field records have been cross-confirmed by different team members to ensure the authenticity and accuracy of the recorded content.

Third, we cross-validated interviews and observations by collecting a variety of archival data. We searched for relevant articles from various public platforms, such as platform of local government departments, official platform of LTC, and industrial publications. We also sorted out all kinds of important files within the company, including the white paper, 5-year plans, handbooks, and annual reports.

3.4 Data Analysis

In this study, to realize the sublimation from “good story” to “good theory,” we adopted a structured data analysis methodology (Gioia et al., 2013) to establish the link between data and theory. First, comparing interview transcript with secondary data, a granular event timeline and holistic overview of LTC’s history, strategy, and scope of business (as presented in Table 3) were systematically sorted out and the development process was divided into three phases. Second, the case was analyzed through first-order concepts and second-order themes, and aggregated dimensions based on existing theories with the qualitative data analysis software NVIVO12. We labeled these dimensions (e.g., path persistence) either by capturing the content at a higher level of abstraction or by referring to existing literature. Finally, going back and forth between data collection and theory development, we iteratively refined the theoretical framework until it was robust.

Business events in LTC’s development

| Year | Events | Business units | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMO | OSMO | LS | ES | ||

| 1993 | LTC was founded | × | |||

| 1994–1996 | Four submarkets had been built | × | |||

| 1997 | LTC became the first listed company in China to focus on specialized textile market operating | × | |||

| 2000–2005 | LTC rezoned all the submarkets according to the categories of textiles and kept the expansion of submarkets | × | |||

| 2006 | The Department of Business Room Transfer and Sublease Transaction Service was established. LTC issued a market management and service document | × | |||

| 2007 | LTC established a service center for foreign businessmen | × | |||

| 2010 | The international logistics center was opened for the traders to provide international logistics public service, including one-stop service for customs clearance and inspection | × | |||

| 2011 | LTC built two submarkets specialized in curtains and greige cloth respectively. Until then, there were over 20 submarkets belonging to LTC | × | |||

| 2012 | LTC started the business of online specialized textiles market | × | |||

| 2016 | The International Logistics and Warehousing Center was established | × | |||

| The “Fangzhiwang” APP was available in the mobile application market | × | ||||

| 2017 | The company held its first overseas self-organized exhibition in Myanmar and organized 143 traders from the offline market to attend the exhibition | × | |||

| 2018–2019 | The company organized a group of suppliers and traders to go to the USA, Italy, and Myanmar successively to participate in textile and fabric exhibitions | × | |||

| 2020 | After the implementation of the “cloud business program,” LTC conducted 14 cloud exhibitions, 58 cloud releases, and 117 live broadcasts throughout the year to promote the development of cross-border e-commerce among the market | × | |||

| LTC implemented a three-year action plan for market intelligence governance | × | ||||

| 2021 | LTC kept conducting the “cloud business program” | × | |||

| LTC built the first foreign franchise area in China to provide a one-stop butler service for foreign traders | × | ||||

Note. SMO, specialized market operation; OSMO, online specialized market operation; LS, logistic service; ES, exhibition service.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the data analysis, we took the following steps in this study: (1) We repeatedly verified the data with the interviewees during data collection and used multiple data sources for cross-checking (Yin, 2013). For example, we validated data from field interviews and direct observations using publicly available literature and archives to avoid backtracking bias. (2) We strictly adopted a “back-to-back” approach for independent analysis, discussed the controversial results collectively, and consulted experts in the field until a consensus was reached. (3) To improve the matching between the data and theory, the logical rationality, and to construct a robust theoretical framework, we drew comparisons between the data analysis, theoretical literature, and analytical memos. (4) We implemented our results after reinterviewing the firm’s representatives and asking for their evaluation of our findings and framework if our results concurred with their experience and understanding.

4 Results

In this study, in order to derive the theoretical framework, we analyzed LTC’s developing process, with a focus on identifying how it responded to different challenges and experienced a path constitution process through the interaction between different types of organizational learning and opportunity space with resilience being built gradually as an outcome. In the present case, organizational learning is reflected in the exploration and exploitation of the various business units related to textile trading, that is, offline market, online market, logistics, and exhibition. Additionally, the resources provided by the supportive market participants in the organizational environment, including suppliers, traders, buyers, and the local government, constitute the opportunity space.

4.1 The Starting Point: Path-creator, Expansion, and Profits

From the very beginning, LTC was the first path-creator to start operating textile specialized market (i.e., building, leasing, and management and service of stores within the market) in the sector. Before the company was established, there were already a very large number of local enterprises and traders engaged in textile trading. But since there was no unified and standardized physical market to provide them with a public platform to achieve the industry economies of scale, in 1993, LTC “seized such an opportunity and started to build specialized markets to bring together the practitioners of textile trading” (F1), including suppliers, traders, and buyers. By 1996, after a quick expansion, it already owned a specialized market with a construction area of 220,000 m2 , four submarkets, and more than 6,000 stores, dealing with textile and fabrics, such as household textile, yarn, greige cloth, apparel and fashion, fashion accessories, textile machinery, and textile stock, gathering a large number of participants (i.e., suppliers, traders, and buyers) in textiles trading. In 1997, LTC was successfully listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, laying the capital foundation for the expansion of the textile specialized markets. “LTC was the first company to be listed on stock in China which was based on the business of specialized wholesale market operating” (F91).

With LTC successively expanding its market scale and dividing into more submarkets, the market soon became the largest textile distribution center in China, benefitting all the participants in textile trading in it. As a senior manager in LTC recalled, “we leased stores to traders who come from provinces of Guangdong, Sichuan, Jiangsu and Fujian,” leading to the situation in which “there are no extra stores to rent out” (F3). Therefore, it is a win–win situation, “both the LTC and its stakeholders made considerable profits thanks to the expansion” (F8). Furthermore, “As this market gathers a large number of people, logistics and capital flows, it has a large contribution to the local textile industry” (F9). In the words of one local governmental chief leader, “due to the economies of scale and cost-effectiveness, merchants from all over China flocked to the market, selling the textiles from this market to the rest of the whole country” (F7), which enhanced LTC’s visibility and reputation.

4.2 The First Entrepreneurial Stage (2000–2011)

4.2.1 The First Challenge: Leadership under Threat

Notably, the leadership was soon under threat. Several competitors in other regions of China followed LTC’s step and established textile specialized markets one after another since late 1990s, attracting buyers and sellers from LTC’s market, which “crowded out its domestic market share” (F9). The products in the market are relatively homogeneous, with raw materials and fabric markets dominating the scene, “as a result, the market is increasingly unable to meet the needs of traders and buyers for a wider range of products” (F29). Besides, due to the lack of experience, LTC was faced with a range of issues, such as management inefficiency like “confusing products segmentation in submarkets” and high rents (F2), which damaged the interests of many participants. As one trader recalled, “At that time, it took buyers hours to find the right variety of textiles, and the fact that the prices of the same variety of textile found in different submarkets were different made us distrust the whole market, as a result, many buyers prefer other specialized markets” (F57), leading to financial difficulty for suppliers due to a large amount of product inventory backlog. As one supplier stressed, “low price competition reduced the profitability of our products and forced us to consider providing our products to other markets rather than the one that LTC owns” (F69). Additionally, some traders’ income could not cover the high rent, leading to a notable phenomenon that “large traders flew out to Guangdong, Jiangsu and other places” (F30). In a word, due to the failure of internal management to keep pace with the rapid expansion of scale, the loss of customers posed a great threat to the path-creator.

4.2.2 Exploitation and Opportunity Space for Expansion

4.2.2.1 Exploitation

After the path had been created, LTC had acquired preliminary knowledge and resources on specialized market management and business expansion. In order to maintain its productivity and efficiency, and leading position in the sector, LTC continuously exploited the current experience about external outreach and internal management accumulated in the early years, making the existing path more dominant by improving and upgrading the organizational behavior pattern. On the one hand, in order to support the further expansion, a complementary unit of logistic business was started. The international logistics center was opened to provide international logistics public service, including one-stop service for customs clearance and inspection. As a senior manager of logistic unit introduced, “the center provides stock management, sample display, joint consignment and catering, accommodation, auto repair and other supporting services, which makes the efficiency of textiles trading greatly improved” (F10) and benefits all the participants. On the other hand, in order to solve issues of internal management, LTC set up a specific department, the Department of Business Room Transfer and Sublease Transaction Service, to better standardize market management and services, and to have the submarkets rezoned. As a senior manager explained, “LTC issued the first documentary on specialized market management measures in China, establishing a systematic and standardized market management mechanism. […] we started to re-classify the submarkets by categories, improved the conditions of hardware and facilities, supervised the business behavior of traders, which enhanced business environment within the market” (F21). The specialized market management measures were established and further standardized a unique market management mechanism (F3).

In this stage, the main mode of organizational learning is exploitation, through which the original organizational behavior pattern and organizational structure are optimized. That is to say, specifically, LTC put effort into addressing the emerging challenge by exploiting current knowledge about scaling up and internal management to maintain its leading position. Moreover, through exploitation, LTC had expanded its external resources and business environment, which is what we call the opportunity space for expansion in this study (as presented in Table 4).

Exemplary quotes and encoding results of first entrepreneurship stage

| Aggregated dimension | Second-order theme | Exemplary quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational learning | Exploitation | In view of the chaotic classification of business varieties and low-price competition in various textile markets, we carried out reasonable planning, systematic management, and improvements of the business environment (F5) |

| To expand the popularity of the textile market, we decided to attract investment from all over the country, promote the operating market environment, and market the idea of “Release water for fish, raise chickens for eggs” (long-term development) (F11) | ||

| We introduced the specialized market management measures, and established and further standardized a unique market management mechanism (F3) | ||

| Opportunity space | Opportunity space for expansion | The local government convinced some market management and financial departments to adopt preferential policies to support traders, especially those with a shortage of capital. At the same time, the market management department also collected the demand information of textile sales for the operators through various channels to help them reverse the loss situation (F4) |

| At that time, specialized markets were just booming all around the country, and traders could choose to engage in textile trading at any location. They were, however, definitely looking for policy-friendly areas. To attract operators, we promoted the growth of the specialized market by lowering taxes (F2) | ||

| With the expansion and prosperity of the professional market, traders from other provinces encountered problems, such as difficulties enrolling children in local schools. Although a relatively minor matter, the government should be willing to assist, so that foreign traders can remain and do business with peace of mind (F23) | ||

| Thanks to the comprehensive textile industrial system, we could find whatever textile product we need. And this has consolidated our industrial foundation to become larger and stronger (F25) | ||

| The LTC has a significant impact on the textile industry. Without this platform, there would be no industry. In turn, the industry also promotes the development of LTC (F93) | ||

| Path constitution | Path persistence | Given that LTC standardized its market management and service, it has established a fully-fledged product chain, “from chemicals, machinery, and grey fabric in the upstream, raw materials and fabrics in the midstream, to garment accessories and home textile products in the downstream” (F17) |

| LTC’s stay in the textile trading sector has been further consolidated thanks to a complete supply chain of textile products (F4) | ||

| Organizational resilience | Resource transformation capability | Our group of textile merchants has long not only been Chinese; increasingly more cloth merchants speaking Arabic, English, Japanese, Korean, and other languages have appeared, therefore LTC’s domestic and international position has gradually solidified (F12) |

| LTC’s platform has really given us great support. Without the market of LTC, a large number of textile printing and dyeing enterprises would have withdrawn from the market (F43) | ||

| We can respond quickly in R&D, production, and sales according to the market conditions to adapt to the needs of our customers. Our company has established market information perception and interaction based on the location advantage of the specialized market (F70) | ||

| The platform of LTC has indeed given us great support in that it provides us with the most cutting-edge and comprehensive platform of trading and information exchanging in the sector (F53) |

4.2.2.2 Opportunity Space for Expansion

In turn, there is no doubt that LTC’s exploitation was profoundly dependent on opportunity space for expansion. As our analysis shows, the opportunity space for expansion of LTC is mainly manifested by the local textile industry and the sound business environment. On one side, as the supplier, the local textile and dyeing manufacturers have laid a strong foundation for the development of textile specialized market. As the first textile production base formed in China, there are enough local textile enterprises providing the market with sufficient and abundant textiles. As one founder of LTC stressed, “back in 1990s, there were more than 500 local SMEs producing polyester, chemical fiber and cotton textiles, without which our market would not have been created” (F1), because “there would have been no suppliers” (F25).

Moreover, due to the significance of LTC to the local textile industry, the local government also attached great importance to the development of the market and had taken a series of supportive measures, creating a stable business environment for all the participants of textile trading. For instance, the local government issued a set of “favorable policies, such as tax credits” (F25) for the participants within the market, supporting LTC’s explorative activities. The market management department also collected the demand information of textile sales for the operators through various channels to help them establish various sales channels (F4). Additionally, the local government founded the Textile Expo to build a platform for textile trading and information exchange. LTC has participated in the Textile Expo since 1999, which is still held twice every year until now, “building a perfect trading platform for textile enterprises and trading companies, buyers and professional visitors to showcase their products” (F24). A local governmental officer agreed that “the original purpose of founding the Textile Expo is to expand the market’s domestic and international influence, giving full play to the role of the specialized market as a distribution center” (F12).

4.2.3 Path Persistence and Resource Transformation Capability

4.2.3.1 Path persistence

As a result of the interaction between exploitation and opportunity space for expansion in this stage, LTC continued to focus on the operation of textile specialized market, so that the path of the organization had been consciously sustained. In this regard, path persistence refers to the notion that after achieving path creation, an organization makes the existing path more dominant by improving and completing the organizational behavior pattern of the existing path in a “positive feedback” fashion. Our analysis shows that, as LTC standardized its market management and service, it has established a full-fledged product chain, “from chemicals, machinery, and grey fabric in the upstream, raw materials and fabrics in the midstream to garment accessories and home textile products in the downstream” (F17). By 2007, LTC already owned 20 submarkets, each with its own differentiated textile category. For example, some submarkets specialize in curtains and drapes. At the same time, the textile industry, as an important anchor, has formed a complete industrial system, “from upstream polyester fiber and chemical fiber raw materials to midstream weaving, dyeing, and finishing, and then to the downstream of the garment, and home textile” (F17). In summary, “LTC’s stay in textile trading sector has been further persisted thanks to a complete chain of textile products and a full supply chain within the professional market” (F4).

4.2.3.2 Resource Transformation Capability

Meanwhile, LTC acquired its resource transformation capability, that is, the conscious behavioral capability to internalize internal and external resources into its own advantages, notably in the utilization of relative resources such as industry platform and political institutions, to maintain its unique competitiveness in the face of overall industry changes. As analyzed above, LTC is no longer the only company in China that is mainly engaged in operating textile specialty markets. Facing fierce competition in the sector, the company has been able to find its strengths and continue to use its industrial resources and knowledge to increase its influence both at home and abroad, thus enabling the company to achieve multiple successes: In 2010, LTC’s specialized market turnover reached 43.9 billion RMB, accounting for 7.8% of the fiscal revenue in the district it is located. This specialized market has become the largest light textile market in the world with the largest variety of products in operation. Particularly, LTC was awarded the “Best Specialized Market in the World” at the 2010 Global SME Cooperation Conference in Shanghai.

4.3 The Second Entrepreneurial Stage (2012–2021)

4.3.1 The Second Challenge: Transformation and Upgrading

In the 2010s, with the transformation and upgrading of China’s traditional textile and dyeing industry, the specialized market was also beginning to face challenges of transformation and upgrading. On the domestic front, textile traders and suppliers in LTC’s market, who are mainly engaged in large-scale wholesale business and volume, need to change their business philosophy and mode as soon as possible to adapt to the new trend of diversified and personalized consumption. On the international front, the accelerated transfer of labor-intensive industries represented by textiles and garments to countries in Southeast Asia and other places with lower labor costs will pose a challenge to its product exports and participation in international competition. In addition, with the rise of e-commerce, there was an urgent need for LTC to expand its online trading market platform, as the company’s CEO recalled at the time, “we have to build our own e-commerce platform just like we built the physical market back then, so that it can become the largest domestic or even global e-commerce online trading market for textiles and stick to the sector” (F2). Moreover, contradictory to the enlargement of textile trading volume, the limited load-bearing capacity of original market supporting facilities, especially the logistics and storage facilities, continue to hinder the efficiency of trading. At the end of this stage, with the outbreak of COVID-19, the company was also facing huge challenges in terms of sales and logistics. Therefore, with the promotion of industrial structure upgrading and the occurrence of more uncertain events, the company is suffering from a comprehensive and deeper turbulence.

4.3.2 Exploration and Opportunity Space for Branding

4.3.2.1 Exploration

To avoid a path lock-in of operating offline specialized markets due to product homogeneity and low-cost competition and to adapt to the new trend in the sector, LTC began to explore a rearrangement of strategy and business units. To be specific, LTC focused on the new strategic goal of “intellectualization and internationalization” (F3) to meet the challenges of industrial transformation and upgrading. In terms of intellectualization, the company began to explore the “online display, offline experience” trading model to build an international market trading and service platform system. In 2012, the online trading platform developed by LTC realized online textile products trading. “There are two online trading platforms, gathering offline traders and suppliers to establish online stores, releasing product information, and collecting order demands from global buyers to realize the accurate matching of product information, enterprise information and order information” (F18). In 2015, LTC further developed a mobile application “Fangzhiwang,” thus building a multi-terminal online platform system for textile trading. In addition, LTC has innovatively implemented the “Three-Year Plan for intellectualization” (F19) and set up the market intellectual service center to provide offline market analysis, information translation, store optimization, promotion and attraction, and operation hosting services to strengthen the deep connection between the online and offline markets. Due to the increase in foreign business and international trade, LTC has even built the first foreign franchise area to provide one-stop butler service for foreign traders.

In terms of internationalization, in addition to developing a global online trading platform to expand trading volume, the company has also launched an exhibition business. LTC attempted to regularly organize offline matchmaking meetings for traders and textile manufacturers, and organize delegations to participate in various textile professional exhibitions at home and abroad. LTC conducted a series of global matchmaking meetings, one after another, with an increasing number of textile enterprises joining the promotional activities (F13). In 2017, for instance, LTC held its first overseas self-organized exhibition in Myanmar and organized 143 traders from the offline market in the exhibition. As a senior manager of exhibition unit recalled, “One after another, LTC organized a group of traders to go to the USA, Italy and Myanmar to participate in textile and fabric exhibitions” (F15). In recent years, the offline exhibition activities have been limited by the COVID-19 pandemic, nevertheless LTC has innovated various projects such as cloud exhibition, cloud live broadcast, cloud release, and cloud docking. After the implementation of the “cloud business program,” “in 2020 alone, LTC carried out 14 cloud exhibitions, 58 cloud releases and 117 live broadcasts in order to promote the development of cross-border e-commerce for the offline market” (F20). LTC also offers free live-streaming skills training for operators in the market to help them adapt quickly to the online sales model since the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this stage, the main mode of organizational learning is exploration. The organization experienced a variety of new changes and experiments to gradually expand knowledge boundaries. In other words, specifically, LTC explored new strategies and units for transformation and upgrading, therefore, by exploration, LTC had expanded its resources for becoming a well-known competitive high-level international platform of textile trading, which is what we call here the opportunity space for branding (as presented in Table 5).

Exemplary quotes and encoding results of second entrepreneurial stage

| Aggregated dimension | Second-order theme | Exemplary quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational learning | Exploration | In 2011, we dedicated every effort for building the “Online Textile Specialized Market” platform (F7) |

| Based on the online trading platform, we launched the “Fangzhiwang” mobile application to further provide an online trading platform (F10) | ||

| We implemented the “online display, offline experience” procurement model, and established a market intelligence service center to provide market analysis, information translation, store optimization, promotion and attraction, operation, and hosting services for market participants (F9) | ||

| We conducted a series of global matchmaking meetings, one after another, with an increasing number of textile enterprises joining our promotional activities. (F13) | ||

| In 2020 alone, LTC conducted 14 cloud exhibitions, 58 cloud releases, and 117 live broadcasts to promote the development of cross-border e-commerce for the offline market (F20) | ||

| Opportunity space | Opportunity space for branding | We found that the China Fabric Sample Warehouse played an integral role in the classification of fabric products, and the integration of upstream and downstream resources in the supply chain for LTC (F19) |

| Every year, we organize traders and manufacturers to travel the world to participate in promotion activities. We have been to the United States, Mexico, Egypt, Italy, France, Korea, Japan, and other countries, and through the promotion, we introduce foreign merchants to LTC’s specialized market (F28) | ||

| The Overseas Market Promotion Association has established offices in 12 countries, including USA, Brazil, UK, Turkey, Italy, Vietnam, Indonesia, UAE, Myanmar, Malaysia, Ethiopia, and the Philippines, and will set up many overseas branches in countries along the “Belt and Road.” We also have the network resources of dozens of national textile associations all over the world (F40) | ||

| Our institution provides various services such as pattern art design, popular fabric design, modern art design, textile analysis and testing, textile technology promotion and application for suppliers and traders in LTC’s specialized market (F39) | ||

| Path constitution | Path breaking | Through transaction mode transformation, function enhancement, business mode diversification and service diversification, LTC has realized the switch from a traditional transaction service provider to a modern industrial integrated service provider (F10) |

| Through the external display of quality textile products, we provide the overseas designers of European high-end brands a new understanding of our fabrics. We have created a “new business card” for international textile capital (F19) | ||

| Their main direction is to connect the digital market and digital logistics through the digital platform supported by the “Global Textile Network” to create a closed loop of the entire industry chain ecology of “Digital LTC” (F6) | ||

| In my opinion, if LTC wants to improve its development level, it must determine the correct positioning and find a highlight: digital reform is an opportunity (F6) | ||

| Our brand building object is to link the upstream and downstream of the industry chain, to enhance the brand influence, so as to better integrate the domestic and international market into “double cycle” (F19) | ||

| After the implementation of the “cloud business program,” in 2020 alone, we carried out 14 cloud exhibitions, 58 cloud releases and 117 live broadcasts in order to promote the development of cross-border e-commerce for the offline market” (F20) | ||

| Organizational resilience | Knowledge renewal capability | As soon as LTC realized that existing knowledge about business segmentation and operating models was no longer valid, they began to update its body of knowledge about internal management and external outreaching (F6) |

| To our understanding, it is not only a matter of operating rules, but also a reflection of commercial civilization and regional culture (F11) | ||

| LTC’s digital transformation has enabled itself to connect with domestic and international markets. The E-commerce platform makes the market more extensive and transparent, which greatly reduces transaction costs (F19) |

4.3.2.2 Opportunity Space for Branding

As this study analyzed, LTC’s exploitation was highly reliant on opportunity space for branding as well. The opportunity space for branding of LTC is mainly manifested by the support of various agencies and associations in the local textile industry and favorable marketing initiatives of local government. At this stage, a complete local textile industry system has been formed, giving rise to various agencies and associations for subdivided industries such as China Textile Industry Federation and association of textile engineering, printing and dyeing, wallcovering, curtains, and embroidery. These agencies and associations play an important role in regulating the business practices, setting industry standards, and promoting innovation in the textile industry including LTC. For example, as a national textile fabric service platform agency that was set up by the China Textile Industry Federation, China Fabric Sample Warehouse provides professional services including product display and promotion, product research and development, product certification, fabric planning, professional training, and information sharing for all the participants of the specialized market. As described by the agency’s main director, “we assist companies with branding needs in organizing, organizing and developing fabric samples, as well as sorting out and optimizing supplier channels” (F36).

In the meanwhile, favorable initiatives implemented by the local government facilitate the formation of opportunity space for branding. A series of promotional events has been taken by the local government to expand the influence and reputation of the specialized market at home and abroad. Among them, the World Textile Merchandising Conference plays an important role in gathering all kinds of textile industry resources for branding of local textile industry and LTC’s specialized market. The local government founded this Conference in 2018 and started the “leading the textiles to every corner of the world” promotion plan, committed to promoting the specialized market as an important node of international and domestic double cycle of textile industry. The conference integrates textile industry resources from around the world and promotes the vertical extension of the entire industrial chain of the local textile industry from raw materials and design to brand creation and promotion by integrating the advantages of platforms such as textile expositions, fashion weeks, professional forums and promotion activities, and enhancing the added value of the entire local textile industry.

4.3.3 Path Breaking and Knowledge Renewal Capability

4.3.3.1 Path Breaking

As a consequence of the interaction between exploration and opportunity space for branding in this stage, based on extending the existing path of focusing on operating the specialized market, LTC gradually avoided the existing path dependence on offline business and led to a new path by adopting explorative learning practices for transformation and upgrading. In this sense, path breaking means that organizations consciously and cautiously deviate from the existing path when they have perceived that the existing path may lead to a lock-in and steer the path toward achieving breakthrough. As shown in our analysis, through the strategy of “intellectualization and internationalization,” LTC succeeded in transformation and upgrading of offline to online–offline business. It “promoted the transformation of its primary functions from offline trading services into online–offline, international logistics, and exhibition services” (F93), thereby extending the value chains of products. The data showed that the specialized market achieved an offline turnover of 250.176 billion yuan, and an online turnover of 80.913 billion yuan. In particular, the online platform has more than 2.08 million registered members, 100,000 online stores, and 3.38 million daily visits. At present, this specialized market has become the world’s largest textile distribution center, where nearly a quarter of the world’s textiles are traded each year, and where products are exported to 192 countries and regions. As a government official in charge commented, “through transaction mode transformation, function enhancement, business mode diversification and service diversification, the company has realized the switch from a traditional transaction service provider to a modern industrial integrated service provider” (F10). And without such a shift, “this market would not be able to attract more buyers from all over the world and bring high-quality professional textiles to the world” (F56).

4.3.3.2 Knowledge Renewal Capability

Simultaneously, LTC acquired its knowledge renewal capability, that is, the ability to reconfigure the organization’s knowledge about internal structure and external relationship with stakeholders through critical self-improvement, which was manifested in the self-renewal in terms of transaction mode and functions. As analyzed above, faced with challenges of transformation and upgrading, “as soon as it realized that existing knowledge about business segmentation and operating models was no longer valid, the company began to update its body of knowledge about internal management and external outreaching” (F6) through the interplay of exploration and opportunity space for branding. “They used digitalization to empower traditional trade and redefine the concept of services, the model of management and the structure of business units” (F96). Relying on the Online specialized market with multi-device, all individual traders in the physical market have realized online transactions. In 2017, LTC was successfully listed as one of the “Top 30 Online and Offline Integrated Specialized Markets in China.” Furthermore, it has competently entered Korea, Italy, Vietnam, the United States, Nigeria, and other countries to conduct promotional activities, and the products have been exported to 192 countries and regions in 6 continents.

4.4 Theoretical Model: Resilience Building through Path Constitution

According to the aforementioned analysis, we developed a model of the organizational resilience building process through path constitution (as presented in Figure 4). First, the process of resilience building refers to the process of continuous path constitution of organizations. The “emergent” environmental challenges trigger the constitution of organizational paths, while the conscious strategic learning behavior (Singh et al., 2015; Sydow et al., 2012) dynamically determines the direction of path (path creation/path persistence/path breaking), thereby influencing organizational resilience building. Second, this study further reveals that the formation mechanism of organizational resilience building is the interaction between different types of organizational learning and opportunity space. In other words, the resources and knowledge gradually accumulated through organizational learning (Jing & Benner, 2016) provide the possibility for organizational change and learning (Kornish & Ulrich, 2011). Third, as organizational paths are continually constituted, organizational core capabilities (that is, manifestations of organizational resilience in various stages) are developed consequently as an outcome of firm’s sustainable performance.

Organizational resilience building process model.

5 Conclusion

5.1 Implications for the Literature

Organizational resilience is considered to be the ability of firms to recover fast from turbulence by mobilizing and accessing the resources available and to maintain sustainable performance. This study aims to investigate how organizational resilience is built amid challenges from a perspective of path constitution by drawing on a longitudinal case study of the China Light & Textile Industry City Group, the leading textile trading platform operator in China. We find that the way of organizations building resilience to sustain stable performance is a process of organizational path constitution. Meanwhile, a model of organizational resilience building was developed. Our study makes two main contributions to current literature. On the one hand, we deconstruct how a firm’s resilience is built from a path constitution perspective. Existing literature on organizational resilience building focus primarily on the role of internal organizational behaviors or factors (Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017). Devoting attention to the interactions between organizations and their environment, our findings showed that the process of organizations to build resilience and maintain good performance could be seen as an interaction process, in which the organizational conscious actions and the emergent environment are both considered significant, expanding the applicable scope of path constitution.

On the other hand, this study deconstructs the mechanism of organizational resilience building based on the interaction between opportunity space and organizational learning (two key elements of path constitution theory). Current studies have investigated opportunity spaces (Jing & Benner, 2016; Kornish & Ulrich, 2011; Kurikka et al., 2022) or organizational learning (Borazon et al., 2023; Hadi & Baskaran, 2021; Kim & Park, 2020; Mao et al., 2023) in explaining organizational development, respectively. Our study investigates how organizational resilience is built and how the company performance is influenced in the interaction process of these two elements from a micro perspective, augmenting the literature on organizational resilience and the body of qualitative research in firm operating.

5.2 Limitations and Future Work

There remain several limitations to this study: (1) Organizational resilience building is regarded as a process of continuous development under the changing environment of the organization, but loose organizational structures may allow multiple paths to exist at the same time. To ensure the core focus and clarity of the main line of research, this article does not discuss the possibility of multiple paths coexisting, which future research should investigate. (2) Since every organization has its own way to achieve resilience, and there is no “magic ten step formula” (Horne, 1997), our findings are based on an in-depth observation of single case, it remains open to what extent our findings are generalizable to incumbent organizations in other sectors. Thus, a comparative analysis could provide deeper insights into the uniqueness and effectiveness of the proposed model. (3) In this study, organizations are supposed to specialize in either exploration or exploitation, but organizational ambidexterity (i.e., a firm’s ability to simultaneously pursue exploitation and exploration) (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Ossenbrink et al., 2019) provides us a broader vision of managing the coexist and trade-off between the two modes of learning in the future research. (4) This study focuses on the long-term perspective, which may not fully address immediate or short-term resilience-building strategies that companies might need during sudden crises or disruptions. Future study should shed more light on the analysis of responses to international emergencies such as Covid-19, etc.

5.3 Practical Implications

The practical implications of this study are as follows: First, in an ever-changing world, enterprises should always be aware of, and make full use of, the perceived range of resources and knowledge available when faced with challenges, and timely adjust the path constitution decision accordingly. Second, companies need to deeply understand the basic logic of organizational resilience building, and maintain sustainable performance through continuous optimization of the interaction between organizational learning and opportunity space. To be specific, enterprises should focus on different ways of organizational learning to obtain a better interaction with the resources and knowledge available in different path constitution stages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, which have improved an earlier version of this manuscript.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant number 22NDJC056YB) and the Soft Science Research Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant number 2023C25045).

-

Author contributions: Gennian Tang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Wenhui Luo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – review & editing. Yaping Zheng: Resources, Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Qunfang Zhou: Resources, Validation, Data curation.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Young, S. L. (2010). Debates in entrepreneurship: Opportunity formation and implications for the field of entrepreneurship. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 23–45). Springer.10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_2Search in Google Scholar

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–71710.1287/orsc.1080.0406Search in Google Scholar

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., & Rouziou, M. (2021). Weathering a crisis: A multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(3), 864–892. doi: 10.1177/10422587211046545.Search in Google Scholar

Argote, L., McEvily, B., & Reagans, R. (2003). Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Management Science, 49(4), 571–582.10.1287/mnsc.49.4.571.14424Search in Google Scholar

Arthur, W. B. (1994). Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.10029Search in Google Scholar

Barasa, E., Mbau, R., & Gilson, L. (2018). What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(6), 491.10.15171/ijhpm.2018.06Search in Google Scholar

Barin Cruz, L., Aguilar Delgado, N., Leca, B., & Gond, J. P. (2016). Institutional resilience in extreme operating environments: The role of institutional work. Business & Society, 55(7), 970–1016.10.1177/0007650314567438Search in Google Scholar

Beckman, C. M., Haunschild, P. R., & Phillips, D. J. (2004). Friends or strangers? Firm-specific uncertainty, market uncertainty, and network partner selection. Organization Science, 15(3), 259–275. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1040.0065.Search in Google Scholar

Borazon, E. Q., Lee, M. T., & Yang, C. C. (2023). Antecedents and consequences of organizational resilience in Taiwan’s accommodation sector. Asia Pacific Business Review. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2023.2242802.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, A. D., & Starkey, K. (2000). Organizational identity and learning: A psychodynamic perspective. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 102–120.10.5465/amr.2000.2791605Search in Google Scholar

Brunner, D. J., Staats, B. R., Tushman, M., & Upton, D. M. (2008). Wellsprings of creation: Perturbation and the paradox of the highly disciplined organization. Harvard Business School Boston.10.2139/ssrn.1093007Search in Google Scholar

Clément, V., & Rivera, J. (2017). From adaptation to transformation: An extended research agenda for organizational resilience to adversity in the natural environment. Organization & Environment, 30(4), 346–365.10.1177/1086026616658333Search in Google Scholar

Cotta, D., & Salvador, F. (2020). Exploring the antecedents of organizational resilience practices – A transactive memory systems approach. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(9), 1531–1559. doi: 10.1108/ijopm-12-2019-0827.Search in Google Scholar

DesJardine, M., Bansal, P., & Yang, Y. (2019). Bouncing back: Building resilience through social and environmental practices in the context of the 2008 global financial crisis. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1434–1460. doi: 10.1177/0149206317708854.Search in Google Scholar

Dodgson, M., Gann, D. M., & Phillips, N. (2013). Organizational learning and the technology of foolishness: The case of virtual worlds at IBM. Organization Science, 24(5), 1358–1376. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1120.0807.Search in Google Scholar

Dragicevic, N., Hernaus, T., & Lee, R. W. B. (2023). Service innovation in Hong Kong organizations: Enablers and challenges to design thinking practices. Creativity and Innovation Management, 32(2), 198–214. doi: 10.1111/caim.12555.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenhardt, K. M. (2020). Theorizing from cases: A commentary. In Research methods in international business (pp. 221–227). Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-22113-3_10Search in Google Scholar

Fang, S., Prayag, G., Ozanne, L. K., & de Vries, H. (2020). Psychological capital, coping mechanisms and organizational resilience: Insights from the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake, New Zealand. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100637. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100637.Search in Google Scholar

Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47, 760–774.10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.xSearch in Google Scholar

Ghasemi, P., Hemmaty, H., Pourghader Chobar, A., Heidari, M. R., & Keramati, M. (2022). A multi-objective and multi-level model for location-routing problem in the supply chain based on the customer’s time window. Journal of Applied Research on Industrial Engineering. doi: 10.22105/jarie.2022.321454.1414.Search in Google Scholar

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151.Search in Google Scholar

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge‐based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122.10.1002/smj.4250171110Search in Google Scholar

Gröschke, D., Hofmann, E., Müller, N. D., & Wolf, J. (2022). Individual and organizational resilience – Insights from healthcare providers in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 965380. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.965380.Search in Google Scholar

Hadi, S., & Baskaran, S. (2021). Examining sustainable business performance determinants in Malaysia upstream petroleum industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294, 126231. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126231.Search in Google Scholar

Hadjielias, E., Christofi, M., & Tarba, S. (2022). Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Business Economics, 59(4), 1351–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11187-021-00588-0.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2017). Tourism and resilience: Individual, organisational and destination perspectives. Channel View Publications.10.21832/9781845416317Search in Google Scholar

Hillmann, J. (2021). Disciplines of organizational resilience: Contributions, critiques, and future research avenues. Review of Managerial Science, 15(4), 879–936. doi: 10.1007/s11846-020-00384-2.Search in Google Scholar

Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2021). Organizational resilience: A valuable construct for management research? International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(1), 7–44. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12239.Search in Google Scholar

Holmqvist, M. (2004). Experiential learning processes of exploitation and exploration within and between organizations: An empirical study of product development. Organization Science, 15(1), 70–81. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1030.0056.Search in Google Scholar

Horne III, J. F. (1997). The coming age of organizational resilience. Paper Presented at the Business Forum.Search in Google Scholar

Howe, L., Johnston, S., & Côte, C. (2023). Mining-related environmental disasters: A High Reliability Organisation (HRO) perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 417, 137965. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137965.Search in Google Scholar

Islam Mim, T., Tasnim, F., Rahman Shamrat, B. A., & Xames, M. D. (2022). Performance prediction of green supply chain using Bayesian belief network: Case study of a textile industry. International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, 11(4), 327–348. doi: 10.22105/riej.2022.360383.1333.Search in Google Scholar

Jia, X., Chowdhury, M., Prayag, G., & Chowdhury, M. M. H. (2020). The role of social capital on proactive and reactive resilience of organizations post-disaster. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 48, 101614.10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101614Search in Google Scholar