67Within the European Member States, it should now be possible to establish a limited liability company fully online. This study compares how the Directive which mandates online formation, has been implemented in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. In particular, it examines whether and, if so, how these countries approach the various cybersecurity risks involved in online formation. The Directive considers these cybersecurity risks, however, the focus is mainly on the requirements regarding the availability of online formation and to a lesser extent the requirements pertaining to the authentication of the founders, as well as the authenticity and integrity of electronic documents. The primary emphasis of the Directive is strongly placed on achieving the objective of facilitating easier, quicker, and more time- and cost-effective company formation. The approach taken by the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany in implementing the Directive and enabling online formation demonstrates a notable level of similarity. All have made sure to safeguard the traditional role of notaries in company formation in these countries. Despite the Directive’s emphasis on availability, the primary concern for these Member States lies in ensuring the security of online formation. All impose strict requirements regarding cybersecurity and opted for the highest standards regarding authentication (assurance level ‘high’) and authenticity (qualified electronic signatures).

I. 68Introduction

Since the summer of 2021, EU Member States must enable people who want to set up a limited liability company to do this fully online. A visit in person to a civil-law notary (hereinafter: notary) or other authority should no longer be needed. The European Directive as regards the use of digital tools and processes in company law (hereinafter: the Directive[1]) adopted in mid-2019 calls for this. In view of a competitive internal market, the aim of the Directive is to facilitate the initiation of economic activities in another Member State by making the formation of a company easier, quicker, and more time- and cost-effective.[2]

Member States have a reasonable margin of appreciation in the way they implement the Directive and set up a procedure for the online formation of companies. For those Member States that did not already allow online formation, 69the implementation is anything but simple. In many cases, they not only have to amend their legal framework regarding the formation of a company, but also have to set up new infrastructure that enables online formation. Moreover, online formation entails various cybersecurity risks that do not exist, or not in the same form, in traditional ‘offline’ formation.

Considering the purpose of a competitive internal market, it is worthwhile to investigate the similarities and possible differences between Member States in the procedure for online formation. In this study, we compare how the Directive has been implemented in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. In addition, we examine whether and, if so, how these countries approach the various cybersecurity risks involved in online formation.

In each of these countries, the notary plays a key role in the formation of a company. In addition, prior to the time that the Directive came into force, none of these countries already allowed fully online formation. Lastly, research shows that the formation of a company in another Member State takes place primarily between neighbouring countries with significant linguistic, social, and economic similarities.[3]

We first discuss the Directive (II). Next, we examine for each separate country how the formation of companies generally takes place and how the Directive is implemented (III-V). Online formation leads to various cybersecurity risks. In Section VI, we cover the relevant provisions in the Directive, and we examine per country to what extent the implemented system for online formation addresses these risks. We end with a conclusion (VII).

II. Online Formation of Companies According to the Directive

The Directive is intended to make the formation of companies easier, quicker, and more time- and cost-effective through the use of digital tools and processes.[4] It must be possible to form a company fully online.[5] Under the Directive, both the act of formation and the formal registration of a company fall under the definition of ‘formation’. Formation is defined as “the whole process of establishing a company in accordance with national law, including the drawing up of the company’s instrument of constitution and all the necessary steps 70for the entry of the company in the register”.[6] Member States are required to ensure the possibility of online formation for at least the specific types of companies as listed in Annex IIA of the Directive.[7] Furthermore, Member States were expected to implement the Directive no later than 1 August 2021.[8]

The Member States must ensure that companies can be established fully online without the ‘applicants’ (hereinafter: founders) having to appear in person before any authority or person mandated under national law to deal with any aspect of the online formation of companies.[9] In the countries studied, these persons or authorities are the notary (charged with the execution of the notarial deed) and the Registry Court respectively the Chamber of Commerce (charged with processing the entry in the register).

It is up to the Member States to lay down detailed rules on the procedure for online formation. The Directive contains a number of conditions to this end. The starting point is that the online formation can be effected by submitting documents and information, such as extracts from the commercial register, in electronic form.[10] Furthermore, the rules to be established by the Member States should also cover, amongst others, the use of templates, the information and documents that are required for online formation, the procedures to ensure that the founders have the necessary legal capacity, and the means to verify the identity of the founders.[11] In addition, Member States may choose to establish provisions with regard to, for example, safeguarding the legality of the deed of incorporation and the role of the notary in online formation.[12]

Part of the simplification of the formation procedure is that it should be possible to establish a company using a template.[13] It would be logical for Member States to make available templates for ‘standard’ companies and establish additional provisions or procedures for companies requiring more customized approaches. Member States should make these templates and certain information on online 71formation available on websites. These templates and information should be in a language that as many international users as possible largely understand.[14]

The Directive also prescribes a timeframe for the online formation. If the company is formed exclusively by natural persons who use the aforementioned templates, the online formation must be completed within five working days after the date of the completion of all required formalities. In all other cases, a period of ten working days applies.[15]

There is one exception to the requirement that companies can be established fully online: mandatory physical presence is permitted if it is necessary to prevent identity misuse or alteration or to guarantee that the founders have legal capacity or possess the authority to represent a company.[16]

The Directive contains comparable rules for the entry of a company in the register. The Member States must ensure that the documents and information that are required to be disclosed by companies can be filed fully online, without the necessity to appear in person.[17] In connection therewith, it must be possible to verify the origin and integrity of the documents submitted online.[18]

Finally, Member States must ensure that they have rules on the disqualification of directors. Those rules shall include the possibility to take into account any disqualification that is in force, or information relevant for disqualification, in another Member State.[19] Member States may require that persons applying to become directors declare whether they are aware of any circumstances which could lead to a disqualification in the Member State concerned.[20]

III. Online Formation of Companies in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, since 1 January 2024, it is possible to incorporate a limited liability company (besloten vennootschap met beperkte aansprakelijkheid, hereinafter: BV) fully online.[21] The Netherlands implemented the obligations 72of the Directive (II) with the Act of 28 Juni 2023 (Wet online oprichting BV, hereinafter: Dutch Implementation Act[22]). The Dutch Implementation Act amended amongst others the Dutch Companies Act (Burgerlijk Wetboek Boek 2 (BW)) and the Dutch Notaries Act (Wet op het notarisambt (Wna)).

1. Formation of a Limited Liability Company (BV)

In the Netherlands, the notary plays a key role in the formation of a BV. A company comes into existence upon the execution before a Dutch notary of the deed of incorporation (akte van oprichting).[23] The deed contains – amongst others – the articles of association. A notarial deed is a constitutive requirement for the formation. In the absence of a notarial deed the company does not come into existence. If the notarial deed lacks authenticity, then the company does come into existence, but it can be dissolved due to a defect in its formation.[24]

Under the conventional (‘offline’) system of formation, the deed of incorporation is executed in the Dutch language.[25] Each founder and each person who takes up one or more shares at the time of the formation shall sign the deed of incorporation.[26] They have to appear before the civil-law in person or have to be represented.[27] Representation requires a power of attorney in writing.[28] A notarial power of attorney is not required.[29]

73The directors are obliged to have the BV registered in the commercial register and to deposit an authentic copy of the deed of incorporation and the documents attached thereto at the office of the commercial register.[30] The registration is – unlike in Belgium or Germany – not a constitutive requirement for formation of the BV.[31] Usually, the executing notary takes care of the registration. This registration is done fully digital via the online webservice of the Chamber of Commerce (Kamer van Koophandel): “Online Registreren Notarissen”.[32]

The notarial involvement in the formation of the BV has – similar to that of the Belgian (IV.1) and German (V.1) notarial involvement – the following three functions: enhancement of legal certainty, the legal protection of parties, and the prevention and combating of abuse.[33] The enhancement of legal certainty consists, inter alia, of the notary ensuring that the incorporation and the mandatory subsequent steps take place in a duly authorised manner and in accordance with relevant legislation. As such, the notary identifies the founders, verifies their legal capacity, examines whether payment on shares has taken place, and handles the registration in the commercial register and, if applicable, the ratification of legal acts performed prior to the formation. The judicial protection results, among other things, from the general information requirement under the Dutch Notaries Act[34] and the notary’s special obligation to warn (the Belehrungspflicht).[35] As an advisor he must not only counsel and inform parties, but also actively alert them to or warn them of the specific judicial consequences of the incorporation of a BV.[36] Lastly, the notary has the task of detecting and combating fraud, money laundering and terrorist financing and other forms of abuse.[37]

74Before the Dutch Implementation Act, it was not possible in the Netherlands to establish a BV fully online. The provisions regarding the execution of a notarial deed had been written based on the idea that the involved parties appear in person before the notary.[38] In addition, the rules governing professional ethics and conduct, plus the obligation of due care of the notary prevented incorporation of the BV in a fully digital way. A notary in principle had to exercise his duty of checking the intention of parties, of informing the parties, and his special obligation to warn (the Belehrungspflicht) in a personal meeting.[39]

2. Online Formation of a Limited Liability Company (BV)

As a result of the Dutch Implementation Act the certification by a notary in the context of the formation of a BV may be carried out by means of video communication. The Netherlands has stayed as much as possible in line with the conventional (‘offline’) system of incorporation and has maintained the central role of the notary.[40]

The core of the Dutch Implementation Act consists of an instruction to the Royal Dutch Association of Civil-Law Notaries (Koninklijke Notariële Beroepsorganisatie; hereinafter: KNB) to set up and manage a designated system (a ‘system for data processing’) that makes online formation possible.[41] The exact 75characteristics of this system are further specified in the rules (the ‘Verordening elektronische notariële akte’ and ‘Reglement elektronische notariële akte’) drafted by the KNB. All civil-law notaries will be required to be connected to this system.[42] The system must meet a number of preconditions.

First, the system must allow the possibility of signing the electronic notarial deed of incorporation.[43] Signing takes place by means of an electronic signature.[44] Preparation of the notarial deed itself can take place outside the system, for example via email or telephone contact with the notary.[45] This can be done through the use of a model instrument prepared and made available online by the KNB.[46]

In addition, the notary must be able to identify the parties involved via electronic identification means.[47] It should also be possible within the system to set up a direct video and audio link between the various parties, witnesses, and the notary in an electronic way.[48] A hybrid meeting through both partial physical and online presence is possible as well.[49] The video and audio link offers the notary, inter alia, the online possibility to meet his general disclosure obligation under the Dutch Notaries Act[50] and his special duty to warn (the Belehrungspflicht).[51] Furthermore, the system should provide the possibility to make online payments (for example, to meet the obligation of payment on shares) and to collect certain data about how online incorporation works in practice (such as the number of online incorporations and the number of instances in which models are used).[52]

76In order to make online formation possible, a new article is added to the Dutch Companies Act stipulating that a company can be formed electronically, using a model deed of incorporation.[53] The online formation is – as in Belgium but different from Germany – only possible if the contribution on the shares is made in in cash.[54] The rationale is to initially limit the availability of online formation to simple situations and subsequently expand it to more complex formations if desired.[55]

The Dutch Companies Act now also contains time frames within which the online formation should be completed.[56] For an incorporation by natural persons making use of a template, this time frame is five working days, while in other cases the online formation must be completed within ten working days.[57] If the deadline is not met, the notary notifies the founders of the reasons for the delay. No sanction is mentioned in case of delay.

The Netherlands has also made use of the possibility in the Directive to include a provision for director disqualification.[58] The intended (supervisory) director of the company to be established online must declare whether he or she has had a director disqualification imposed by another Member State on grounds that are comparable to the grounds of the director disqualification in Art. 106 a of the Dutch Bankruptcy Act (Faillissementswet (Fw)). If this is the case, the intended director cannot be appointed.[59] The restriction of Art. 106 a Fw is to prevent the acknowledgement of director disqualifications by another Member State for reasons that would provide insufficient grounds for a director disqualification under Dutch law.[60] The regulation for director disqualifications raises various questions and has been received critically by legal scholars.[61] One of the concerns pertains to the effectiveness of the regulation. For example, it is 77not clear whether and how the notary should verify the declaration of the intended (supervisory) director.[62]

The template that can be used for online formation is at least in English.[63] In addition, it has been determined that the deed of incorporation, as well as subsequent amendments to the articles of association, may also be executed in English. This is an exception to the main rule that the deed is in Dutch.[64]

IV. Online Formation of Companies in Belgium

Setting up a company fully online was made possible for the first time in Belgium by the Act of 12 July 2021[65] (hereinafter: the Belgian Implementation Act) implementing the Directive (II). The Belgian Implementation Act amended the Belgian Companies Act (Wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen (WVV)) and the Belgian Notaries Act (Wet van 25 ventôse jaar XI op het notarisambt (Wet ventôse)). As a result, it has been possible since 1 August 2021 to set up a company with limited liability fully online. Previously 78this was not possible. In Belgium the Directive truly acted as a catalyst, to overcome the reservations many had against online formation.

1. Formation of Limited Liability Company (BV)

In Belgium, a notarial deed has always been and remains[66] mandatory for the setting up of corporations, in the sense of companies with limited liability, that is companies that take the legal form of a besloten vennootschap met beperkte aansprakelijkheid (BV; private company), naamloze vennootschap (NV; public company) or coöperatieve vennootschap (CV; cooperative company).[67]

The function of the notary in company formation is similar to that of the Dutch (III.1) and German (V.1) notary and is traditionally seen as threefold: firstly, the notary has to provide legal certainty by checking that all formal requirements have been met, secondly, the notary guides founders through the formation process, and informs them about the implications of the formation (the Belehrungspflicht), and thirdly, the notary checks compliance with certain specific mandatory rules from outside company law (such as anti-money-laundering legislation).

The Belgian Implementation Act did not change the different formal and disclosure steps that have to be taken when setting up a company in Belgium. The most important steps are the following. First of course, drafting the articles of incorporation (oprichtingsakte[68]) in the form of a notarial deed. Second, the 79notary registers the notarial deed with the registrar of the commercial court (Ondernemingsrechtbank), which gives rise to the legal birth of the company and its attainment of legal personality. The notarial deed will be the first document in the electronic “company file” that the court registrar keeps for every company that is registered with it, and in which a whole series of other documents[69] have to be filed in accordance with the provisions of the Belgian Companies Act. Finally, an excerpt from the articles of association has to be published in the Appendices to Belgium’s Official Gazette, so that the company can rely against third parties on the information thus disclosed.

Since 2006, a system of “E-depot” has been in operation, meaning that notaries, after having drafted a notarial deed on paper could, and since 2016 as a rule have to, send an electronic version of the articles of incorporation to the court registrar and the Kruispuntbank van Ondernemingen (Central Enterprise Database, hereinafter: KBO).[70] If documents are indeed sent electronically to the court registrar and the KBO database, the necessary data, intended for publication in the Official Gazette, are automatically forwarded to that service, as well as to the VAT administration, and the company would receive on the same day as its formation its “enterprise number” which it needs to be allowed to start operating a business.

2. Online Formation of a Limited Liability Company (BV)

As in the past, the intervention of a notary who draws up a notarial deed is still required under the Belgian Implementation Act. However, a physical visit to the notary is no longer required. The founders can take part in an online video meeting with the notary and sign documents remotely through an electronic signature. A paper version of the notarial deed is no longer required (cf IV.1). Notarial deeds can now be fully digital.

The amended Belgian Notaries Act states that “authentic” (i.e. notarial) deeds concerning the formation of legal persons may also be drawn up in “dematerialized” (i.e. digital) form and that the notary may draft such digital acts without the parties being present in person before him; parties may be present “at a distance”, i. e. online, and proceedings may take place through a video meeting 80through a designated system set up by the Royal Belgian Federation of Notaries (Koninklijke Federatie van het Belgisch Notariaat, hereinafter: FedNot).[71] The FedNot has indeed set up such a system (and had been busy creating the network quite a while before the Belgian Implementation Act was adopted[72]) and has called it “StartMyBusiness”.

The wording of the new rules was initially limited to the articles of incorporation, which also contain the articles of association.[73] If the articles of incorporation take the form of a notarial deed, then later changes to the articles of association will also require a notarial deed. But since a second amendment to the Belgian Notaries Act, it is possible, since 26 June 2023, to also perform changes to the articles of association in a digital format. However, since such changes to the articles require a decision by the general meeting, a fully online amendment is only possible if the general meeting can also be held online. Since December 2020, restrictions on online meetings have been lifted and they can now be organized on the initiative of the board of directors.[74] It has to be admitted, however, that Belgian online general meetings are not completely online, since the “bureau” of the general meeting (the chair of the meeting and usually one or two more directors or administrative support staff or the company secretary) is still required to physically sit together in a specific location[75], usually either at the registered office of the company or at the notary’s office; in practice, the bureau will normally sit together with the notary in one location. So, in effect, shareholders, directors and others can take part through a videolink in a physical meeting held by the bureau. The result is that for changes to the articles of a company that was set up online, a physical meeting between the notary and at least one director will still almost always take place, because the rules on online participation in general meetings still require the bureau to meet in person, in a location where they may be joined by any shareholder who prefers to attend the general meeting in person rather than online.

Furthermore, the online procedure may – similar to the Dutch system, but different from the German system – only be applied when all contributions are 81fully in money and not in kind.[76] If any of the founders want to make a contribution in kind, the parties will have to appear in person before the notary.[77]

Note that the Belgian Notaries Act allows the articles of incorporation of all legal persons to be drawn up in a digital format, not just those of a besloten vennootschap (BV) or naamloze vennootschap (NV). Henceforth, any time parties use a notary for the formation of a legal person, they will be able to use the fully online procedure. It is irrelevant whether the legal person is a company (always for profit in Belgium), an association (can only be used for non-profit organisations in Belgium) or private or public foundation, and irrelevant as well whether the law mandates a notarial deed for the articles of incorporation[78] or not.[79] Hence, the ambit of the Belgian Implementation Act is much broader than the Directive. The latter indicates that Member States may limit the online formation to certain types of companies (II).

Anyone wishing to set up a legal person using a digital notarial deed, will have to register on the StartMyBusiness system. The accompanying website contains information files on how to set up a company and what the implications and duties of those involved are. They are the basic and standardised information that a notary could provide to company founders as part of his advisory duty, but this standardised information cannot replace individual advice the notary may have to give, as part of his deontological Belehrungspflicht (see before), to company founders, during the online meeting.

82The website of StartMyBusiness also contains standard articles of association that founders can use as a template, but only for the besloten vennootschap (BV), even though, as mentioned before, Belgian legislation now also allows the naamloze vennootschap (NV) and indeed all other legal persons to be set up fully online. The Directive mandates that such templates are provided for at least the BV (II), and the FedNot, not forced to do otherwise by statute, have construed this minimalistically by not providing a template for the NV (or any other legal person).

The online video meeting between the notary and the founders must take place through the StartMyBusiness system. The meeting cannot take place through ordinary commercial video-platforms such as Zoom or MS Teams. Parties who so wish always have the right to be physically present at the notary’s office. This could result in “hybrid” meetings, with some founders taking part online, others being present at the premises of the notary. During the videocall, the notary will perform his function in the usual way. For instance, he may read part of the draft text of the documents to the parties and may advise them orally on their obligations as company founders. In the end, the notary and the founders will electronically sign the digital documents (VI.2.b).

As explained above, after the notary has executed the articles of incorporation, they need to be registered with the registrar of the commercial court, and an excerpt needs to be published in the Official Gazette. The Belgian Implementation Act has introduced a shorter timeframe to do this for online than for offline transactions. Under the traditional (offline) system, where parties physically meet with the notary, the notary has 30 days after the date of the notarial deed to register it with the commercial court.[80] The excerpt needs to be published in the Official Gazette within 10 days[81] after the registration. The law now states that, in accordance with the Directive, in case of an online formation, “the formation of the company needs to be handled within 10 days”. This means that within 10 days after the date on which the notary has signed the notarial deed, that deed must be registered with the court register and the excerpt must be published in the official gazette within the same 10 day period.[82] If all founders in an online procedure are natural persons and they use the template provided on the StartMyBusiness portal (which only provides a template for the BV (private company)), the time limit for registration and disclo83sure is 5 days. If these time limits are not respected, the notary will inform the founders about the reasons for the delay.

For historical political reasons, the use of languages is a sensitive issue in Belgium, with the constitutionally enshrined principles of territoriality and exclusivity, meaning in Flanders the official language is Dutch, in Wallonia it is French[83], and Brussels is bilingual (French-Dutch). This means (among other things) that all “official acts” must be in the official language, otherwise they are usually null and void[84] and fines can be imposed on private firms or civil servants using the “wrong” language in official documents or communications. The concept of “official acts” does not only pertain to government documents, but also to many corporate documents, including the articles of incorporation. All recent lobbying efforts to change the application of this law to private firms, by allowing the use of English as an alternative to Dutch or French, have failed, even though the vast majority of firms would like to see such a change. It therefore does not come as a surprise that Belgium has made no efforts to make the use of its BV company form more attractive to foreigners by offering a template in English, let alone allowing English as an official language for corporate documents. In other words, the traditional language rules apply to an online formation in the same way as to an offline procedure.

The Directive also contains some optional rules on director disqualification (II). Belgium has had rules on director disqualification since 1934 (in a separate act outside the Belgian Companies Act)[85], and these are regularly amended. One problem with the rules was that they were weakly enforced, and one reason for that was that there was no easily accessible database with persons, including directors, who had been disqualified. An Act of 4 May 2023 tries to partially tackle the problem by organizing a new Central Register of Director Disqualifications[86] that will centralize the relevant data. Certain categories of court staff and civil servants, but also notaries, will have access to all data in the 84register for professional purposes.[87] The general public will have access to a list with the names of the disqualified persons and the time period during which they are subject to a disqualification. The registrar of the court register where appointments of directors and people with similar functions have to be registered, and notaries that intervene in the registration process, will have to refuse such registration of directors who are subject to a disqualification. Unlike the Netherlands (III.2), this provision on directors’ disqualification applies to directors of all companies, whether they are incorporated fully online or through the ‘traditional offline’ manner. In addition, when a new director is appointed at a company or other private organization, the board of the company will have to issue a statement that accompanies the registration document pertaining to the newly appointed director, saying that this director is not subject to disqualification measures in another member state of the European Economic Area. If such a statement is lacking, the registrar or notary must inform a section of the district criminal court, and that section may decide to do a search through the system of Europe-wide linked registers for any sort of disqualification the director may be subject to in other EEA member states.[88]

V. Online Formation of Companies in Germany

In Germany, since 1 August 2022, it has been made possible to incorporate a limited liability company (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, hereinafter: GmbH) fully online. Germany implemented the obligations of the Directive (II) with the Act of 5 July 2021 (Gesetz zur Umsetzung der Digitalisierungsrichtlinie, hereinafter: DiRUG[89]) and the Act of 15 July 2022 (Gesetz zur Ergänzung der Regelungen zur Umsetzung der Digitalisierungsrichtlinie und zur Änderung weiterer Vorschriften, hereinafter: DiREG[90]). The DiRUG and DiREG amended, amongst others, the German Act on Limited Liability Companies (Gesetz betreffend die Gesellschaften mit beschränkter Haftung (GmbHG)) and the German Notarisation Act (Beurkundungsgesetz (BeurkG)). As a result of these reforms, it is now possible to appear before the notary online in the process of setting up a GmbH. Previously, this was not possible.

1. 85Formation of a Limited Liability Company (GmbH)

In Germany, as in Belgium and the Netherlands, the formation of a GmbH is not possible without the involvement of a notary. The articles of association require a notarial deed and therefor certification (Beurkundung) by a notary.[91] For this purpose, amongst others, the articles of association are laid down in a notarial deed[92] (deed of incorporation), which is read out loud to the participants in the presence of the notary, and is approved and signed by them personally.[93] The notary can certify the articles of association in a foreign language if he has sufficient familiarity with the foreign language.[94] However, for the registration in the commercial register a certified German translation must be attached.[95]

The articles of association must be signed by all founding shareholders.[96] This signature may be executed either in person or by power of attorney established or authenticated (beglaubigt) by a notary.[97] Subsequently, the GmbH must be registered in the commercial register.[98] The registration is, as in Belgium but unlike in the Netherlands, a constitutive requirement for formation of the GmbH.[99]

If there is a lack of form in the certification procedure, the articles of association are generally void.[100] Such a lack of form also means that the registry court (Registergericht) has to refuse to make the entry in the commercial register.[101] However, if the GmbH is registered despite the lack of form, the defect is remedied.[102]

86The rationale for the requirement of a notarial intervention in the incorporation of the GmbH is similar to that of the Netherlands (III.1) and Belgium (IV.1): firstly, the enhancement of legal certainty protection, secondly, the legal protection of the founders: it is intended to make them aware of the significance and consequences of their actions, and thirdly, notarial certification serves the purpose of guaranteeing material correctness.[103]

2. Online Formation of a Limited Liability Company (GmbH)

As a result of the DiRUG, the certification by a notary in the context of the formation of a GmbH may be carried out by means of video communication.[104] This online certification process can only take place using a designated system that is operated by the Federal Chamber of Notaries (Bundesnotarkammer).[105] The use of other systems, such as Zoom or Teams, is not allowed.[106]

The traditional certification procedure is to be mirrored in the online procedure. The notary ascertains the identity of the participants by means of a photograph transmitted electronically to him as well as by means of electronic identification means.[107] Subsequently, an electronic notarial deed must be drawn up, read out loud to the participants in the digital presence of the notary, and signed by the participants and the notary electronically.[108] A template (Musterprotokolle) can be used.[109] The templates are only available in German; there is debate as to whether the Directive mandates that the templates are also made available in English.[110] Hybrid certification through 87both partial physical and online presence of participants is possible as well.[111]

Finally, the online incorporated GmbH can be registered electronically in the commercial register by the notary.[112] For the online formation by solely natural persons making use of a template, the registration shall take place within five working days after the receipt of the complete application, while in other cases of online formation the registration must be completed within ten working days.[113] If the deadline is not met, then the registry court notifies the founders of the reasons for the delay.[114]

Initially, the online formation of a GmbH was only possible if the contribution to the shares was made in cash.[115] However, as of 1 August 2023, the scope of online incorporation process is expanded by the DiREG and the online formation of a GmbH with contributions in kind is – unlike in the Netherlands (III.2) and Belgium (IV.2) – also possible.[116]

From a German perspective, the rules on directors disqualification from the Directive essentially do not introduce anything new.[117] The GmbHG already contained a catalogue of criminal offences as a result of which a person may not be appointed as a director; comparable foreign offences were already taken into account.[118] What is new is that as a result of the DiRUG other European occupational and trade disqualifications now also lead to directors disqualification.[119]

VI. Cybersecurity of Online Formation of Companies

The online formation of companies entails various cybersecurity risks that are not present, or not in the same form, in a formation that is fully offline.[120] On88line formation leads to new risks in relation to the authentication of the founders (VI.1), the authenticity and integrity of electronic information (VI.2), and the availability of the infrastructure required for online formation (VI.3). In this Section, we will analyse how the Directive and national implementations deal with these risks.

1. Authentication of Founders

The founders may adopt a false name online. It is therefore necessary to verify the identity of the founders. The Directive contains provisions regarding this ‘authentication’. It mandates the Member States to enable the use of ‘electronic identification means’ within the meaning of the ‘eIDAS Regulation’ (VI.1.a).[121] The Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany all demand electronic identification means with a ‘high’ assurance level (VI.1.b)

a) Authentication of founders in the Directive

Article 13g(3)(b) of the Directive states that the implementations by the Member States should specify, inter alia, the means to verify the identity of the founders ‘in accordance with Article 13b of the Directive’. Article 13b stipulates that the Member States must ensure that citizens of the European Union can use electronic identification means for this purpose. First, the founders must be able to use a means that has issued under an ‘electronic identification scheme’ that has been approved by the Member State.[122] Second, they should be able to use means issued in other Member States that have been recognised for the purpose of cross-border authentication in accordance with Article 6(1) 89of the eIDAS Regulation. For example, for the incorporation of a GmbH in Germany, Dutch founders could use DigiD or eHerkenning. Similarly, a Dutch BV can be established by German founders using their National Identity Card.[123]

Article 6(1) of the eIDAS Regulation contains an obligation for ‘public sector bodies’, including private entities that have been mandated to offer public services.[124] When access to a public service requires identification using an electronic identification means, means issued in other Member States must also be recognised under certain conditions.[125] These conditions ensure that Member States are only obligated to accept foreign electronic identification means that provide sufficient certainty about the identity of the founder. First, the relevant electronic identification scheme must be registered and included in the list of the European Commission.[126] A scheme can only be included if it provides sufficient guarantees in relation to the identity of the user. It must meet one of the assurance levels (‘high’, ‘substantial’, ‘low’) elaborated in the ‘Implementing Regulation’ pursuant to Article 8(3).[127] This Implementing Regulation contains specifications to guarantee the reliability of the electronic identification means. The stringency of these specifications depends on the assurance level of the means.

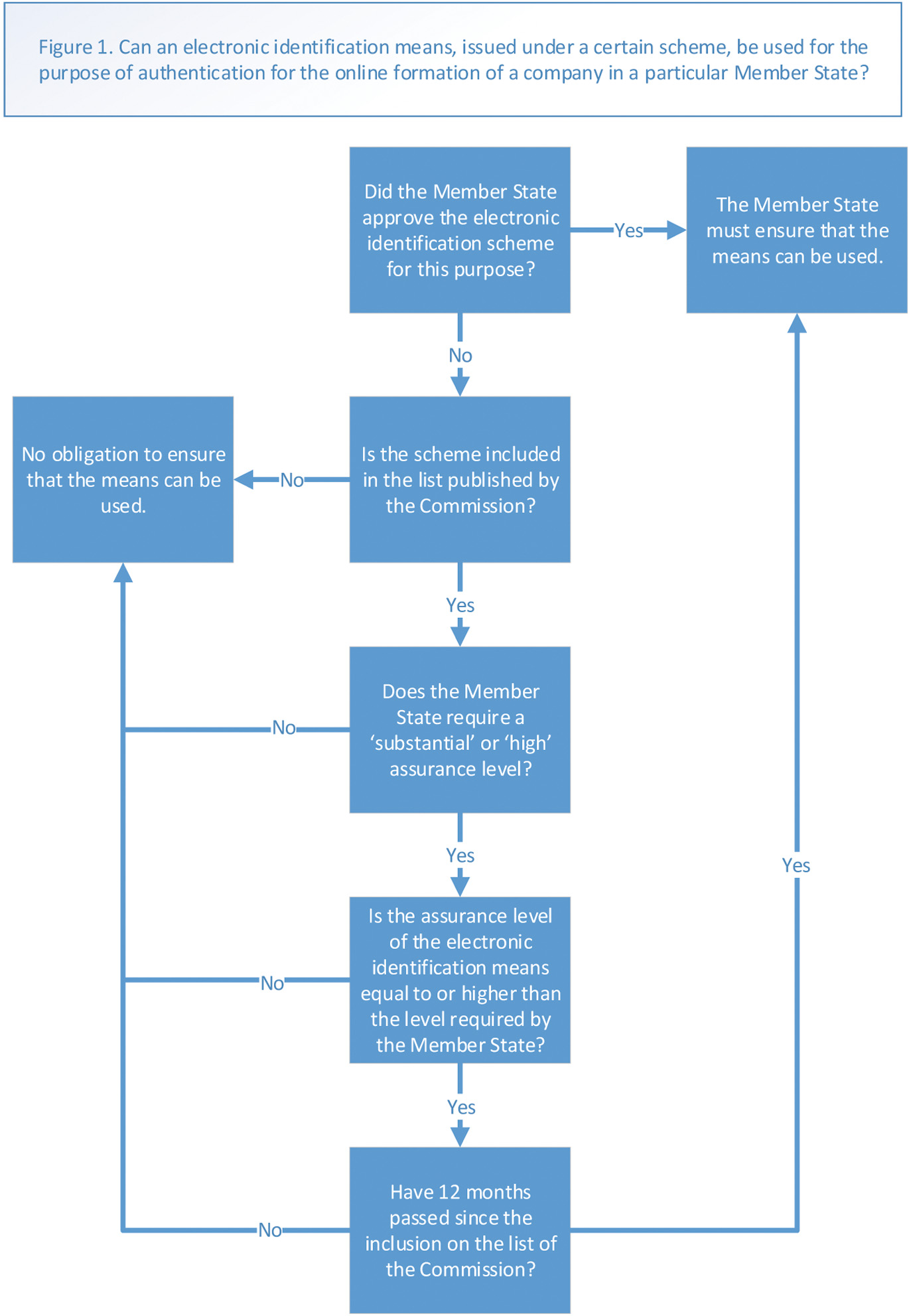

The obligation to recognise electronic identification means also depends on the assurance level required by the Member State.[128] The ‘foreign’ means must 90achieve the same level as the means approved by the Member State. Furthermore, an obligation to recognise only exists if the required assurance level is ‘substantial’ or ‘high’.[129] A Member State is never required to recognise means that have a ‘low’ assurance level,[130] even if the approved natural scheme also only guarantee a ‘low’ assurance level. This means that a Member State could theoretically frustrate the cross-border online formation of companies by citizens from other Member States by only approving an electronic identification scheme with a ‘low’ assurance level that (in practice or de jure) is only available to its own citizens. Figure 1 provides a chart to determine whether an electronic identification means can be used in a certain country.91

92The Directive provides a framework for the authentication of the founders: it should be done with electronic identification means. However, it does not contain minimum requirements regarding the reliability of the electronic identification means approved under Art. 13b(1)(a) of the Directive. The requirements on the authentication are thus largely left to the discretion of the Member States. The Directive does not prevent Member States from allowing online formation with unreliable electronic identifiers.[131] On the contrary, it prohibits overly strict authentication requirements that render the online formation impossible.[132] For example, it is not permitted to always require the physical presence of the founders for their authentication. This should be an exception and may only be required in situations where there are reasons to suspect that identity misuse or a lack of legal capacity or authority to represent the company.[133] At the same time, the option to require the physical presence in some situations does show that the obligation to allow online formation is not absolute. Cybersecurity can override this obligation in some limited circumstances.

b) Authentication of Founders in the Member States

Although the Directive does not place strict minimum requirements on the electronic identification means used for the authentication of the founders, The Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany have each opted for the assurance level ‘high’.

The Netherlands simply requires an electronic identification means with the assurance level ‘high’.[134] The system for data processing should facilitate the authentication with these means.[135]

The rules in Belgium and Germany are more extensive. Germany requires an electronic identification means issued under one of the three notified national schemes with the assurance level ‘high’ or an electronic identification means issued by another Member State with the same assurance level.[136] In Belgium, the founders can either use the Belgium means ‘Citizen eCard’, ‘Foreigner 93eCard’ or ‘Itsme’[137] or, if they are EU Citizens, any other recognised electronic identification means with the same assurance level.[138] Since the Belgian schemes assure a ‘high’ level,[139] the other schemes must also meet this level. Furthermore, the law also allows identification using specific advanced or qualified electronic signatures or seals (VI.2.a) with a similar level of security. This is only possible if these specific signatures or seals have been recognised as such by royal decree after a recommendation from the FedNot. Belgium and Germany also provide obligations about the use of photographs. Germany requires authentication with a photograph in addition to an electronic identification means.[140] In Belgium, a notary is allowed to request a photograph from the official Belgian or foreign registries to further the authentication of the founders.[141]

Other national provisions also strengthen the authentication. More specifically, they show that the important role of civil law notaries in the online formation of companies also extends to the authentication of the founders. In each of the discussed Member States, the online formation involves a video call with the founders and the notary through the national systems for online formation.[142] Although this call is not explicitly or exclusively meant for the authentication of the founders, it does give the notary an additional chance to detect identity fraud and other irregularities. This adds another element to the authentication.[143] Gaining access to an electronic identification means is insufficient if the fraudster is unable to deceive the notary in the video call. This is especially relevant in Germany and Belgium, where the law explicitly provides that photographs can or must play a role in the authentication. Finally, in accordance with the Directive, a notary can demand the physical presence of the founders when there are reasons to suspect identity misuse or a lack of legal capacity in each of the Member States.[144]

2. 94Authenticity and Integrity of Electronic Information

The online formation and registration of a company depends on the formation and disclosure of several documents.[145] For online formation, it should be possible to create and submit the documents and information completely online.[146] However, digital information can be altered. This can lead to doubts in regard to the ‘integrity’ of the provided information. Furthermore, someone could pose as a founder and provide false information. In this case, the ‘authenticity’ of the information is compromised. These risks also affect the ‘non-repudiation’ of the formation of the company. If the integrity and authenticity are not guaranteed, it is not possible to prove that the founders actually formed a company in accordance with the provided information. They could deny that they formed the company or claim that they formed a company with different characteristics.

The risks in relation to the authenticity and integrity of electronic information can be further subdivided into the information that is provided by the founders, the information that is subsequently entered into the register, and the information that is issuedby the register. The Directive only contains general provisions about the information provided by the founders, whereas the rules about the information entered into and issued by the registers are much stricter (VI.2.a). Although this could cause risks in relation to the role of the notary, the Member States have addressed these risks by extending the strict requirements to the information provided by the founders (VI.2.b).

a) Authenticity and Integrity of Electronic Information in the Directive

The Directive contains various relevant provisions in relation to the authenticity and integrity of electronic information. Article 13j(2) contains a general obligation about the information entered into the register. It must be possible to verify the ‘origin’ and integrity of the documents in the register electronically. Furthermore, Article 13j(4) provides that Article 13g(2) to (5) applies mutatis mutandis to the online filing of documents and information. This could be interpreted to mean, for example, that Member States should also lay down rules on the use of electronic identification means for the purpose of filing the relevant documents.[147] However, electronic identification means only guarantee that the authenticated person filed a document. They do not guarantee that this document corresponds with the document in the register or that 95this document has not been altered. In other words, electronic identification means guarantee authentication (VI.1.a), but not the integrity and authenticity of the information itself.

Art. 13g(3)(c) of the Directive, which also applies mutatis mutandis, offers a potential solution. The Member States should also lay down rules about the use of ‘trust services’ within the meaning of Art. 3(16) of the eIDAS Regulation by the founders. This includes rules about ‘electronic signatures’ and ‘electronic seals’. These signatures and seals are data in electronic form, attached to or logically associated with other data in electronic form and can be used by the ‘signatory’ to sign (for signatories) or to ensure the latter’s origin and integrity (for seals).[148]

Electronic signatures can exist in different forms. For example, the signatory can sign a document by adding a scanned written signature or with an electronic identification means. However, these methods do not guarantee the integrity of the signed document. They do not prevent the document from being altered. Furthermore, a scanned written signature can also be inserted by another person.

In contrast, ‘advanced’ and ‘qualified’ electronic signatures and seals[149] do guarantee integrity and authenticity.[150] They can only be created by the signatory.[151] Furthermore, they make sure that any change to the signed document is detectable.[152] These results are generally achieved by asymmetric cryptography. The signatories sign the relevant documents by generating and encrypting a ‘hash’ of the document with their ‘private key’. This encrypted hash functions as an electronic signature. It can only be generated with the private key of the signatory, and thus verifies the authenticity of the document. It also ensures integrity. The signature depends on a hash of the signed document. If the document is changed, the hash will be different and the signature will no longer be valid.

The register can check (or ‘validate’)[153] the signature with the public key of the signatory. This key is linked in a cryptographic manner to the private key. Although it cannot be used to generate the signature, it does enable its verification. The public key is, as the name suggests, public. The register therefore 96does not depend on the cooperation of the signatory for the verification of the signature. For this reason, advanced and qualified electronic signatures go beyond the requirements of Art. 13g(2) of the Directive. They do not only guarantee the authenticity (or ‘origin’) and integrity of the documents. They also achieve non-repudiation. The signatory cannot deny that it has signed the documents.

The register can only rely on the signature if it knows that a specific public key belongs to a specific signatory. This is generally achieved with a (qualified) ‘certificate for electronic signature’ that is issued by a (qualified) ‘trust service provider’.[154] The trust service providers verify the identity of the signatories.

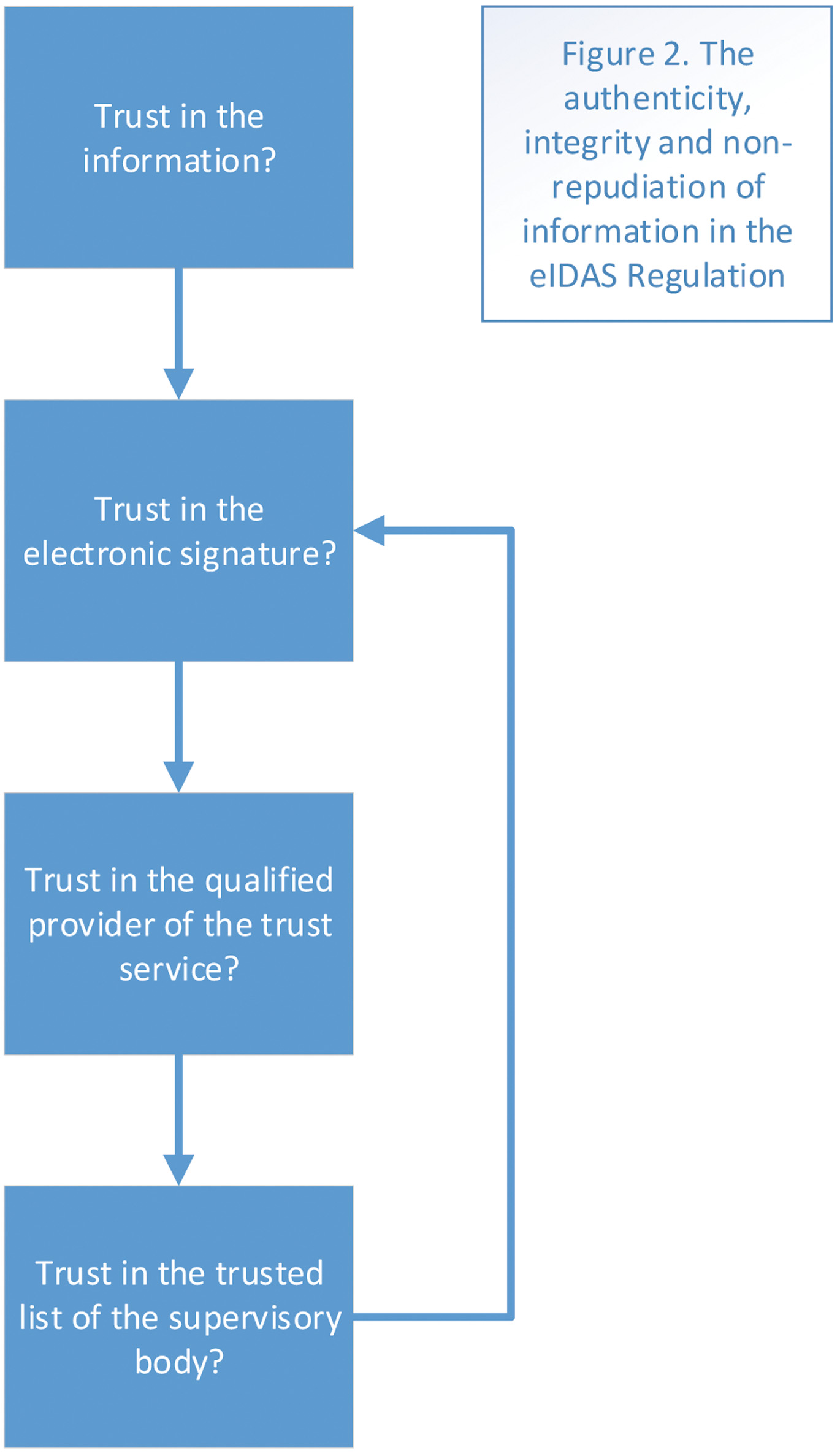

Qualified electronic signatures offer the most certainty. The eIDAS Regulation formulates more stringent requirements for these signatures than for ‘normal’ or ‘advanced’ electronic signatures.[155] They are also subject to more supervision. They may only be offered by providers of trust services who have received the ‘qualified’ status from the national supervisory body of the Member State where they are established.[156] Furthermore, the Member States must establish, maintain, and publish ‘trusted lists’ pursuant to Art. 22(1) of the eIDAS Regulation. These lists contain information on the qualified providers for which they are responsible. The European Commission publishes an overview of the various lists.[157] The trusted lists enable the register and other parties to verify whether a specific trust service provider is ‘qualified’. Under Art. 22(2) of the eIDAS Regulation, the trustworthiness of these lists is guaranteed by an electronic signature. Figure 2 gives an overview of the way electronic signatures and the system of the eIDAS regulation can achieve the authenticity, integrity, and non-repudiation of electronic information.

97Besides provisions on the reliability of the information entered into the register, the Directive also contains rules on the integrity and authenticity of the information issued by the register. This is especially relevant if a company is formed by another legal person. In this case, it may be necessary to verify that this legal entity exists, has not been declared insolvent, and that the agent has the power to represent it.[158] Article 16a(4) of the Directive stipulates that elec98tronic copies and extracts should be authenticated by means of trust services. The authentication is explicitly intended to guarantee integrity and authenticity. Article 16a(4) states that it is meant ‘to guarantee that the electronic copies or extracts have been provided by the register’ and are ‘a true copy’.[159]

The Directive thus explicitly obligates the Member States to ensure that trust services can be used to guarantee the authenticity and integrity of the information entered into and issued by the register. Although it does not explicitly obligate Member States to prescribe advanced or qualified electronic signatures or seals for this purpose, these are obviously to be preferred from a cybersecurity perspective. They provide authenticity, integrity, and non-repudiation and thus ensure the compliance with Articles 13j(2) and 16a(4) of the Directive.

b) Authenticity and Integrity of Electronic Information in the Member States

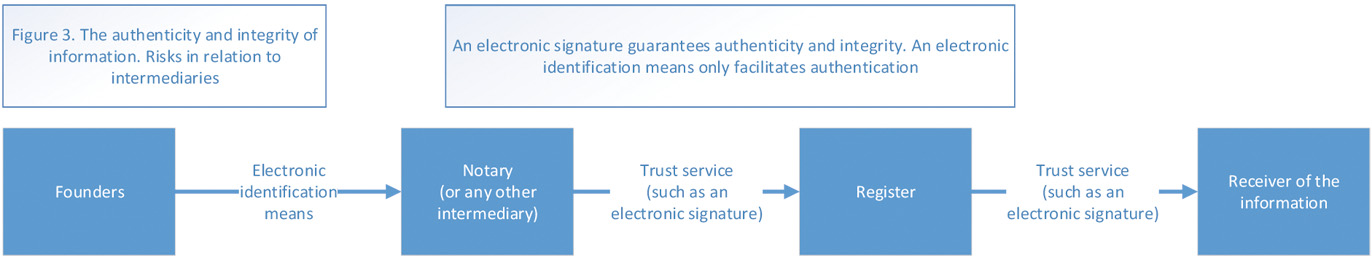

The involvement of a notary introduces new complications in relation to the authenticity and integrity of electronic information. In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, the relevant documents are typically entered into the register by the notary (III.1, IV.1 and V.2).[160] Furthermore, the most important document, the notarial deed, is not supplied directly by the founders. Instead, it is prepared by the notary.

This leads to new risks. In theory, the information provided by the founders to the notary could be altered before it is entered into the register. As discussed in Section VI.2.a, the prescribed electronic identification means do not guarantee authenticity and integrity. Even if the notary uses an advanced or qualified electronic signature, the information provided by the founders to the notary could still be altered before it is entered into the register or included in the notarial deed. Figure 3 gives an overview of this issue.

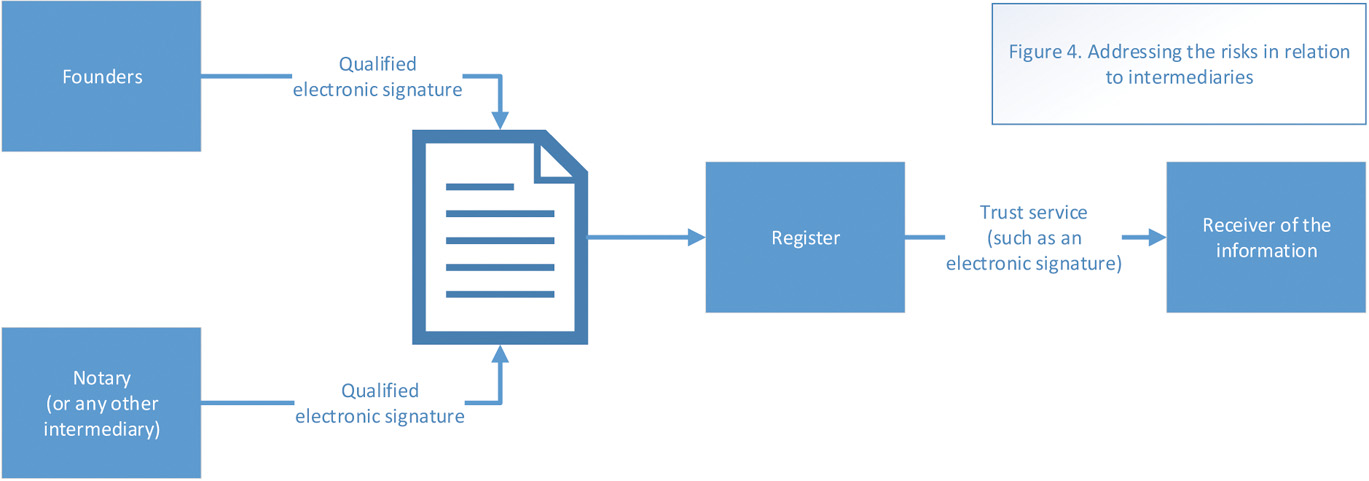

99The Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany deal with this issue in a similar way. In the case of ‘offline’ incorporation, authenticity and integrity are safeguarded by the fact that the founders all physically sign the same physical deed that is prepared by the notary. This solution is also used with online formation. The various designated systems enable the founders to electronically sign the digital notarial deed (III.2, IV.2 and V.2). Furthermore, they each require a qualified electronic signature, thus safeguarding authenticity and integrity.[161] Figure 4 gives an overview of this solution.

Some differences between the Member States exist. The electronic identification means registered in Belgium also allow the creation of a qualified electronic signature.[162] If the founders use other means, the qualified electronic signature is created through the designated system. In contrast, the Netherlands requires a (separate) qualified electronic signature of the type PAdES LTA or PKCS#7 LTA,[163] placing the burden of obtaining such a signature on the founders. Finally, the German BeurkG does not prescribe a specific form of quali100fied electronic signatures. However, it does emphasise that the signatories should create the signatures themselves, thus also placing the burden on the founders.[164]

3. Availability of Infrastructure for Online Formation

Finally, the successful online formation of a company depends on the ‘availability’ and ‘accessibility’ of the required infrastructure. Online formation is not an attractive option if it is more complicated, more expensive, slower, and more unreliable than offline formation.

a) Availability of Infrastructure for Online Formation in the Directive

The Directive is intended to enable and stimulate the online formation of companies as an easy, quick, and time- and cost-effective alternative to offline formation (II). In order to guarantee this attractiveness, it contains several provisions that deal with the availability of the required infrastructure.

First, Articles 13g(1) and 13j(1) of the Directive mandate the Member States in general terms to ensure that it is possible to form and register a company fully online. Other provisions deal with specific aspects. Various of these aspects have been discussed in Section II. For example, Member States should provide templates and free, concise, and user-friendly information to assist in the formation of companies. Furthermore, online formation should be possible within a certain timeframe.

Any fees for online procedures may not endanger the accessibility of online formation. Such fees should therefore be transparent and applied in a non-discriminatory manner. They may not exceed the costs of providing the services.[165] This also applies to fees for obtaining an electronic copy of documents and information included in the registers.[166] It should be possible to pay for online procedures by means of a widely available online payment service that can be used for cross-border payments.[167] Similarly, the online payment of share capital should also be possible.[168]

101In some situations, it is necessary to obtain information from other Member States. For example, it may be necessary to determine whether a director has been disqualified in another Member State.[169] Member States are therefore obligated to provide each other and the general public with electronic copies of the documents and information included in the registers. This exchange is achieved through the ‘system of interconnection of registers’.[170] Pursuant to Article 13i(3) and (4), this includes information that is relevant for the disqualification of directors.

b) Availability of Infrastructure for Online Formation in the Member States

In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, online formation depends on a designated system that is provided by the national associations of notaries (III.2, IV.2 and V.2). In essence, this means that the Member States have passed on their obligations in relation to the availability and accessibility of online formation to these associations.

The Dutch law is particularly explicit. The Dutch Notaries Act states that the designated system should comply with various requirements.[171] For example, it should facilitate the authentication with electronic identification means, electronic signatures and the online payment and be reliable and secured. Similarly, the German system operated by the Bundesnotarkammer should enable, inter alia, the video communication between the notary and participants, the electronic identification of participants, and the use of a qualified electronic signature.[172] Belgium does not have a similar explicit provision, but the division of 102responsibility remains the same. Next, the accessibility of online formation is enhanced by the requirement to provide templates and information (VI.3.a). In this regard, it is noteworthy that only the Netherlands stipulates that these templates should also be provided in English (III.2, IV.2 and V.2).

Finally, the proposed Article 2:175a(3) of the Dutch Civil Code charges the notaries with the timely completion (III.2) of the online formation without any reference to the designated system. If this is not possible, the notary has to inform the founders.[173] German law provides a different rule. It charges the registry court (Registergericht) with the timely registration of the formation of the company. It has five or ten working days from the receipt of the application (V.2).[174] This means that the legal maximum period only starts to run after the video meeting with the notary.[175] The legal maximum is thus much longer in Germany. Belgium law takes a middle ground. The notary is responsible for the timely foundation, but the period only starts to run after the deed is prepared and signed (IV.2).[176]

This discrepancy is the result of a difference between the laws of the Member States. In the Netherlands, registration is obligatory, but not required for the existence of the company (III.1). In Germany and Belgium, registration is a constitutive requirement for the existence of the company as a legal person (IV.1 and V.1). For this reason, the Directive does not force Germany and Belgium to guarantee faster online formation.[177]

VII. Conclusion

Within the European Member States, it should now be possible to incorporate a limited liability company fully online. The purpose of the Directive, which mandates online formation, is to promote a competitive internal market by facilitating the initiation of economic activities in another Member State; the formation of a company should be easier, quicker, and more time- and cost-effective.

103In this study, we compare how the Directive has been implemented in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. In particular, we examine whether and, if so, how these countries approach the various cybersecurity risks involved in online formation in their respective legislation. The Directive considers these cybersecurity risks. However, in our view, these provisions of the Directive lack adequate balance. There is a noticeable disparity between the requirements concerning the availability of online formation and the requirements pertaining to the authentication of the founders, as well as the authenticity and integrity of electronic documents. The provisions relating to availability are more detailed, numerous, and prescriptive than those relating to authenticity and integrity. The primary emphasis of the Directive is strongly placed on achieving the objective of facilitating easier, quicker, and more time- and cost-effective company formation.

During the implementation of the Directive, Member States were faced with various decisions. Not only did they need to alter the existing legal framework for the formation of a company, they also had to establish a partially new designated system for online formation. Throughout this process, Member States were particularly confronted with the need to carefully consider and assess the trade-off between the availability and the authenticity and integrity of online formation.

In their procedures for online formation the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany all impose strict requirements regarding cybersecurity. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that these procedures demonstrate primarily similarities in all three countries. All have opted to mirror the conventional (‘offline’) method of formation, thereby preserving the key role of the notary in the formation process. Additionally, the responsibility for designing and overseeing the designated system for online formation has been entrusted to the respective national associations of notaries in all three countries. In the preconditions for that designated system, all countries opted for the highest standards regarding authentication (assurance level ‘high’) and authenticity (qualified electronic signatures). Hence, despite the Directive’s emphasis on availability, the primary concern for these Member States lies in ensuring the security of online formation.

Besides these similarities, there are also some differences between the three countries. For instance, in the Netherlands the templates for online formation are provided not only in the native language but also in English, Belgium has used the implementation of the Directive as an opportunity to extend the option of online formation to all types of legal persons, and in Germany online formation is also possible with contribution in kind.

© 2024 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- The Regulation of Corporate Governance in European Financial Market Infrastructures: A Critique

- Duty of Loyalty: Corruption of Company Directors and Prohibition of External Remuneration

- Cybersecurity and Online Formation of Companies in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany

- The Strategic Importance of Public Recapitalisation in Banking Resolution, What Ireland Can Tell

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- The Regulation of Corporate Governance in European Financial Market Infrastructures: A Critique

- Duty of Loyalty: Corruption of Company Directors and Prohibition of External Remuneration

- Cybersecurity and Online Formation of Companies in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany

- The Strategic Importance of Public Recapitalisation in Banking Resolution, What Ireland Can Tell