The Regulation of Corporate Governance in European Financial Market Infrastructures: A Critique

-

Eilís Ferran

1This article is the first to consider the variations in governance requirements applicable to European financial market infrastructures. It charts the tangled combination of laws, codes and regulations that apply to the governance of the largest European central counterparties, central securities depositories, and international central securities depositories. Despite the similarity of these institutions in terms of their sector, criticality, complexity and purpose, there are substantive variations in what is required of their governance. Here we question whether this variance is an appropriate reflection of differing institutional needs or a by-product of piecemeal regulatory reform.Our research found no apparent need to regulate for consistency of board size or structure, nor in relation to specificities of committee requirements. However, there are convincing arguments that change is needed around the meaning and application of independence. The current approach to FMI directorial independence is a poor fit given the sectors highly technical nature, its interconnectedness, and the limited pool of available expertise. On top of this, expertise, diversity, and commitment can become trade-offs for adherence to the requirements of independence. We argue that regulation needs to be sensitively calibrated to ensure these important factors do not get squeezed out under the weight of formalized independence. It is our view that independence requirements can be structured to create better balanced boards where the needs of independence, expertise, diversity, and commitment can be weighed against each other in context.

1. 2Introduction

This paper studies the corporate governance of the main Europe–based central counterparties (CCPs, also known as clearing houses) and central securities depositories (CSDs), of which a subset are international central securities depositories (ICSDs) and, where relevant, their parent companies. CCPs, and (I)CSDs are key post-trade financial market infrastructures (FMIs).[1]

Our focus group – Deutsche Börse group (DBG), Euroclear Group, Euronext Group, and London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) – includes the dominant actors in both CSD and CCP services in Europe: Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (CBL), the ICSD within the DBG; Euroclear Bank (EB), the ICSD within Euroclear; and the LCH CCPs, owned by the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG).[2] The inclusion of the Euronext Group in our study is explained by its ambitious plans to develop its inhouse clearing business alongside its ownership of a number of domestic CSDs.[3] This selection allows for a 3study of major actors that share the experience of operating in a regulatory environment that has been mostly shaped by EU law.

Post-trade FMIs are important to the proper functioning of the economy, central bank implementation of monetary policy, and the overall stability of the financial system. Their systemic criticality has provided strong justification for extensive public interest-oriented regulation of FMI corporate governance. FMI corporate governance has a strong public interest orientation that distinguishes it from the shareholder primacy variety of corporate governance that remains at the heart of Anglo-American corporate laws applicable to listed commercial companies, notwithstanding growing interest in attaching greater weight to the interests of other constituencies in corporate decision-making.[4] Like banks, FMIs are special in this respect.

We focus on the size and shape of boards and board committees, directorial independence, collective and individual expertise, time commitment and diversity. These elements are ‘fundamental’ to sound governance and ‘non-negotiable’ according to Elizabeth McCaul, a member of the European Central Bank (ECB) supervisory board.[5] They are the key governance features targeted by existing bank and FMI regulation.[6]

4Our study takes us beyond regulatory requirements specific to CCPs and CSDs to also include bank governance regulation, because some FMIs hold banking licences, and to parent/financial holding company governance because the FMIs in question are members of larger corporate groups. As such, we confront the issue of regulatory difference across sectors and consider whether this variety appropriately reflects variance in business models and risk profile or is an anomalous and unintended side-effect of piecemeal rulemaking processes. This paper seeks to add to existing literature on this topic, which until now has not examined the FMI context specifically.[7] Unjustified regulatory inconsistencies are untidy and add to complexity but more serious still is their potentially limiting impact on the eligible pool of appointable candidate-directors in this specialist and highly technical sector, especially their cumulative impact on FMIs that also hold banking licences. Related to this is our concern that criteria that define (lack of) independence by reference to business connections could further constrain available talent pools given the nature of the FMI sector, which is dominated by major actors that serve as hubs of densely interconnected, global networks.

Our study is relevant to the analysis of the interface between stakeholder-oriented regulatory requirements and shareholder-oriented corporate laws. The FMIs in our study are shareholder-owned, for-profit companies with boards that are subject to appointment and removal by shareholders in accordance with normal corporate laws and governance procedures, but their business success depends on regulatory licences whose retention depends on meeting supervisory expectations, including with respect to individual and collective directorial suitability. Supervisors have prioritized a more intrusive approach to fit and proper (F&P) assessments in recent years;[8] and while they may hesitate to press the nuclear button of revoking an individual’s F&P status, they are becoming increasingly assertive about applying qualitative measures and in their willingness to use the annual supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP) to increase the pressure on institutions to address governance weaknesses.[9] Directors of FMIs thus operate within an environment of demanding 5risk management frameworks, stringent supervisory oversight and potentially costly capital charges if controls are ineffective.[10] While we are clear that there is no room for complacency about the effectiveness of financial market supervisors in ensuring that stakeholder interests receive due consideration by boards (not least because recent bank failures have reminded us that supervisors can slip up too[11]), our analysis will be premised on a relatively positive view of oversight by external supervisors as a powerful mechanism for giving ‘bite’ to the public interest (or stakeholder) focus of regulatory-led corporate governance requirements.[12] At the same time, we are also mindful of the need for supervisors to be held appropriately accountable for their use of these impactful discretionary powers.[13]

The paper proceeds as follows. After this introduction, Section 2 reviews the ‘specialness’ arguments that are used to justify regulatory intervention into financial sector corporate governance, starting with bank corporate governance, where the literature is most developed, and then considering these arguments in the FMI context. Section 3 outlines certain distinctive features of our focus group’s business models, operating environment, and regulatory frame6works.[14] Section 4 (board size and shape) and section 5 (the board composition challenge) present our analysis and core findings. Our key normative contribution is to argue for a rationalization of the formal independence tests across the domains that we study (banks and FMIs) and for independence of mind to become a more generally applicable regulatory requirement. We also highlight inconsistencies for which we can see no principled justification, such as the failure to extend board diversity requirements to CCPs. Section 6 concludes.

2. ‘Specialness’

2.1. Banks

We begin this section by briefly reviewing the extensive body of literature relating to bank corporate governance.[15] Many FMIs are part of larger groups that include entities that hold banking licences; some of the major FMIs that we focus on in this study hold limited purpose banking licences.

The literature establishes that the need for a distinctive approach to the corporate governance of banks is based on a range of factors including their capital structure, leverage, and money creation function, the asymmetry between an opaque and complex business and highly liquid liabilities, their multitudinous stakeholders, their size, scale and interconnectedness, and the greater burden of regulation under which they operate.[16] There is circularity to the argument that regulating the governance of banks is necessary because the heavy regulation of the industry impedes the market forces upon which other sectors rely to support their governance standards. However, the shock of the 2008 financial crisis put paid to the notion that private monitoring of bank governance could ever be effective without extensive government intervention. That shock continues to shape regulatory thinking to this day.

7The 2008 financial crisis ignited a regulatory drive to strengthen the alignment between the internal corporate governance arrangements of financial market actors and public interest objectives.[17]Making bank corporate governance work better came to be seen as “critical to the proper functioning of the banking sector and the economy as a whole”.[18] ‘Soft law’ corporate governance norms thus hardened into ‘hard law’ prudential regulatory requirements with a strongly stakeholder-oriented character that reflected banks’ systemic significance, highly distinctive risk profile, and asset and funding structures.

The greater emphasis on a stakeholder/public interest focused variety of governance was supported by evidence from the financial crisis of higher levels of risk-taking in banks where shareholders had stronger rights.[19] ‘Good’ corporate governance from a shareholder perspective was revealed often to have been misaligned with bank soundness.[20] An inescapable conclusion from the bailouts and restructurings that came to define the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis was that bank corporate governance could never be reduced to a simple problem of conflicts of interests between management and shareholders.[21] The trade-offs between stakeholders are more complex.

The current Basel Corporate Governance Principles for banks are bracingly unequivocal in asserting that “the primary objective of corporate governance should be safeguarding stakeholders’ interest in conformity with public interest on a sustainable basis”. Moreover: “among stakeholders, particularly with respect to retail banks, shareholders’ interest would be secondary to depositors’ interest”.[22]

2.2. 8FMIs

The Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) – which are the international standards for FMIs – are as unequivocal as the Basel Principles for banks in stating that governance should promote the safety and efficiency of the FMI, and support the stability of the broader financial system, other relevant public interest considerations, and the objectives of relevant stakeholders.[23] Like banks, FMIs are opaque and complex businesses with multitudinous stakeholders. FMIs, especially CCPs, take risk out of the financial system but in so doing they concentrate risk in themselves. They are also more interconnected with other market players than other financial institutions. FMIs’ IT systems handle a mindboggling volume of clearing and settlement traffic daily, and any failures or interruptions could transmit major shocks throughout the financial markets. In an era of intensifying cyber and ransomware threats against critical infrastructure, it is more vital than ever that these technology-heavy, systemically important institutions are well run. The failure of a major FMI would be globally catastrophic given their size, scale and interconnectedness. There are thus strong public interest justifications for regulatory intervention aimed at ensuring that FMIs construct boards that balance profitable pursuit of existing business lines and new technological opportunities against the need for resilience to withstand attacks and a robust approach to risk and systemic safety.

Of course, it is not for the State to seek entirely to displace the market forces that normally shape the design of corporate governance. What will best serve the public interest is a combination of regulation, best practice guidance, contractual requirements and market incentives that provides the optimum mix between flexibility, stability and simplicity. However, the strong incumbent network effects enjoyed by, and limited competition between, the dominant actors in the FMI ecosystem are further reasons why regulation may need to do more of the heavy lifting than would be required in other market segments. To place this comment in context, the next section explores distinctive features of the European FMI market.

3. 9European FMI business models, operating environment and regulatory framework

3.1. CSDs and ICSDs

CSDs are central to the financial markets in most countries and across borders.[24] Their main functions are to record the issuance of securities (notary service), maintain securities accounts at the top level (central maintenance service) and operate a securities settlement system (securities settlement service).[25] A CSD acts as an issuer when it takes responsibility for these services. It acts as an investor CSD when it facilitates the access of investors to the issuer CSD by opening accounts in other CSDs to enable cross-system settlement. A single CSD may perform both roles. CSDs typically provide a range of ancillary issuer services. Certain CSDs (mostly the ICSDs[26]) hold banking licences that enable them to offer settlement in commercial bank money and provide intra-day liquidity.[27] ICSDs may also offer settlement in central bank money.[28]

The EU harmonized the regulation of CSDs at Union level in 2014 with the adoption of the Central Securities Depositories Regulation (CSDR).[29] CSDR was onshored into UK domestic law as part of the Brexit process and the cor10porate governance elements of the CSDR framework that are relevant to this paper continue to apply in the UK.[30] One of the stated aims of CSDR was to create more competition between CSDs but, apart from the ICSDs, European CSDs continue to operate mostly along national lines. With few exceptions, there remain significant barriers to the provision of cross-border CSD issuer services for domestic securities, including unharmonized securities and company laws, and nationally specific corporate action and withholding tax processes.[31] Since the barriers are rooted in varieties of substantive law, recent changes to CSDR to streamline passporting processes may not make much practical difference.[32] On the other hand, competition in settlement could be impacted by recent changes that introduce additional possibilities for the provision of banking-type ancillary services .[33]

Providing investor CSD services is not a significant business line for European domestic CSDs[34] and does not require a regulatory passport as it can be achieved by CSDs simply becoming participants in each other’s systems.[35] Global custodians that provide cross-border custody and settlement services by being participants in different issuer CSDs are an alternative way for investors to operate internationally.

ICSDs are a subset of the broader category of CSDs and have a more international orientation, supporting the distribution and trade of securities and funds, across multiple international markets and their settlement in different currencies. Euroclear Bank and CBL are central to what has become the world’s largest international capital market for cross-border distribution of securities to investors globally.[36] The ICSDs combine core CSD functions with banking services and are supervised as both. This dual regulatory status has governance implications, which we discuss further in sections 4 and 5 of this paper. Euroclear Bank and CBL compete as issuer and investor CSDs and in11creasingly in funds distribution and other ancillary services.[37] As investor CSDs they are also in competition with global custodians and other CSDs.[38] The increasing provision by ICSDs of more post-trade services, traditionally provided by national CSDs, suggests the fragmented European market for CSD services may be becoming more streamlined.[39]

3.2. CCPs

The key feature that distinguishes CCPs from other providers of clearing services is that a CCP becomes the counterparty for all transactions recorded on its books: the CCP replaces each buyer in the contract with the seller and each seller in the contract with the buyer.[40] By stepping in between buyers and sellers and thereby breaking the chain of interconnection, CPPs ensure that if one party fails to perform their side of the contract, that failure does not ripple through the financial markets.[41] CCPs have sophisticated operational and default management mechanisms that enhance transparency and reduce counterparty, credit, liquidity, operational and contagion risk. CCPs also perform important market monitoring and surveillance functions. All of which contributes to their high systemic significance.

The European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR), adopted in 2012, harmonized CCP regulation and imposed mandatory CCP derivatives clearing requirements.[42] EMIR was onshored into UK domestic law during the 12Brexit transition and the corporate governance elements of the EMIR framework continue to apply in the UK.[43] As CCPs have progressively become more critical to financial stability, their soundness has inevitably become an ever more important policy concern.[44] This has led to the adoption of new, or significantly enhanced, dedicated CCP resolution frameworks.[45] The corporate governance requirements that we discuss further in sections 4 and 5 of this paper are distinctive in the extent to which they include the significant involvement of market participants (clearing members and end clients) in internal governance processes.[46]

The tendency of European CCPs to specialise in the clearing of certain asset classes means that financial institutions that seek to centrally clear different assets need cross membership (or indirect participation) with several CCPs.[47] There are interoperability arrangements that allow clearing members of one CCP to centrally clear trades carried out with members of another CCP without the need for dual membership. However, regulatory permission to establish interoperability links is not granted lightly because, from a stability perspective, they introduce greater complexity and additional contagion channels due to the inter-CCP dependencies that they involve.[48]

European regulation seeks to facilitate competition between CCPs by providing for non-discriminatory access to a CCP from different trading venues[49] and 13vice versa.[50] However, the reality, as noted by Thomadakis and Lannoo, is that while “small CCPs may have a local footprint, cleared markets are structured around global hubs with broad cross-border access”.[51] Activity is concentrated in a small number of CCPs because of network externalities and the costs of fragmentation in clearing (in terms of loss of netting and collateral saving opportunities).[52]

The LCH subgroup (including French-based LCH SA and UK-based LCH Ltd) within the LSEG group stands at the forefront of clearing business in Europe and internationally and provides clearing services across a wide range of classes of financial instruments.[53] LCH SA holds a French banking licence.[54] Eurex is the DBG’s primary CCP. Eurex’s authorization as a CCP covers securities, derivative, repos and certain other assets. It also holds a German banking licence.[55]

Euronext’s move away from LCH as its preferred CCP and its promotion of its own in-house CCP is an important development but it is too early to assess its significance.

4. Boards and Board Committees: A Snapshot

With the market context sketched out, we now turn to the detail of internal governance arrangements within our study group.

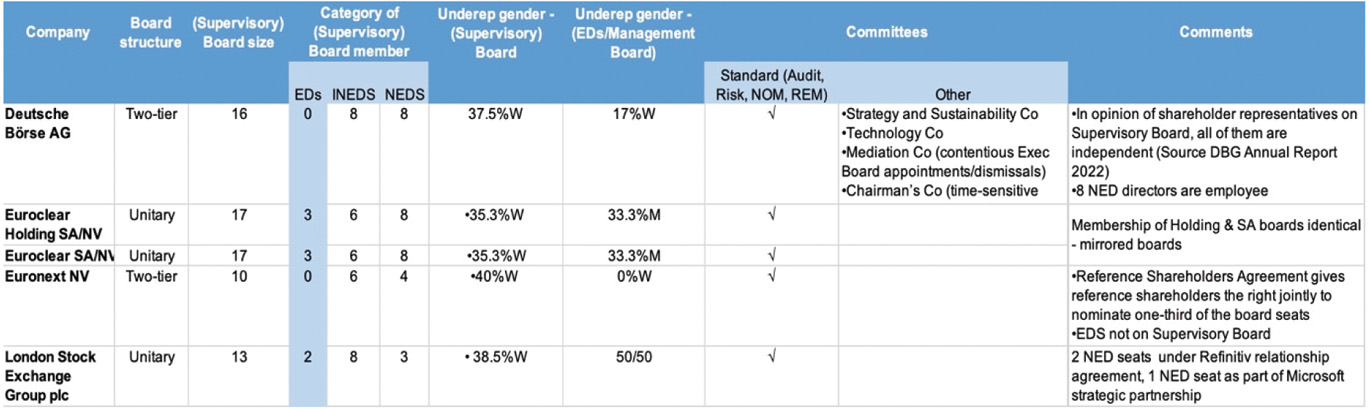

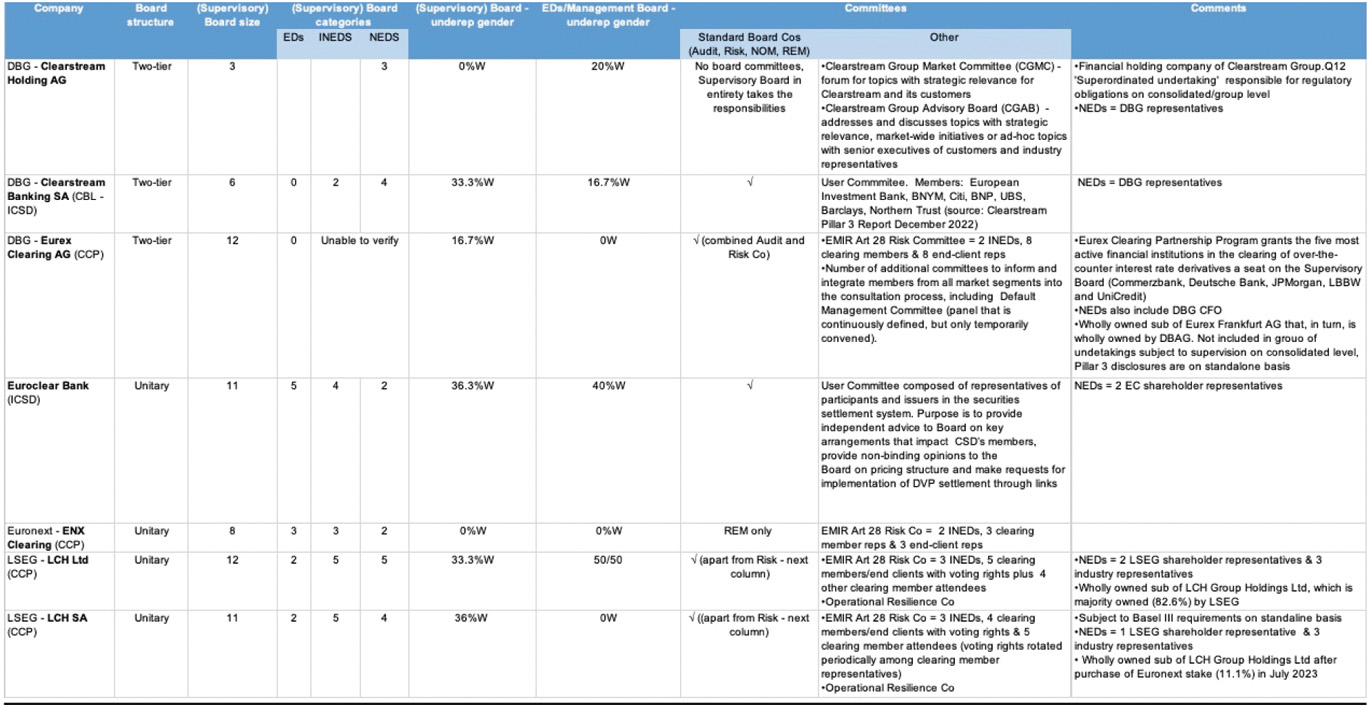

Table 1 below provides a snapshot of board composition and committee structures of the ultimate parents within our chosen focus group entities as at end August 2023. Table 2 does the same for the major CSDs and CCPs in our 14study and, where relevant, their intermediate holding companies. Both tables are based on publicly available information, including consolidated annual reports, Pillar 3 disclosure reports[56] and public announcements that we tracked down during our research, and to the best of our knowledge they are accurate as at end August 2023. Director turnover makes it inevitable that the picture will date quickly but it serves as a valuable point-in-time indicator of the design of corporate governance in groups containing CCPs and (I)CSDs that are subject to banking and/or FMI regulation.

4.1. 15Group Level Considerations

The ultimate parent of the DBG, Euronext and LSEG groups is a listed entity: respectively Deutsche Börse AG, Euronext NV, and London Stock Exchange Group plc. The corporate governance of the parents, as listed companies, is shaped by their domestic corporate law, articles of association, listing requirements, corporate governance codes and other recommendations, plus any applicable sectoral regulatory requirements and guidance.

For the purposes of this research, Euroclear SA and Euroclear Holding are together treated as the parent of the Euroclear group.[57] Being privately owned, Euroclear is not subject to listing requirements and is outside the scope of the Belgian Code on Corporate Governance (BCGC), but it may look to these as a source of guidance on governance good practice.

As the top-level entities of corporate groups that include CCPs and/or CSDs (some of which hold banking licences), the governance of the parent companies in our study is influenced by regulatory requirements relating to both FMI and bank governance. There are requirements relating to the suitability of shareholders to ensure sound and prudent management in the Regulations governing CSDs[58] and CCPs[59], and also in the prudential regulatory framework for banks.[60] Relevant to the DBG, Euronext and LSEG groups in their roles as owners of market operators, there are also similar suitability require16ments under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFIDII), relating to persons in a position to exercise, directly or indirectly, significant influence over the management of a regulated market.[61]

Euroclear SA and Euroclear Holding are ‘parent financial holding companies’ (FHCs) under the EU banking prudential regulatory framework,[62] which means that the F&P supervisory oversight regime for board members applies to their FHC role.[63] Additionally, Euroclear SA is also subject to the prudential regulation of its corporate governance because, under Belgian banking law, it is a regulated institution supporting a domestically systemically important financial institution and a ‘other systemically important institution’. Deutsche Börse AG and the London Stock Exchange plc are also the ultimate parent companies of EU credit institutions, but they are not FHCs because as diversified businesses, prudential consolidation operates at sub-consolidation levels.[64] Therefore, in discussing the governance requirements applicable to FHCs, we will focus our attention on the Euroclear group and Belgian law.

4.2. 17Board Structure and Size

The choice of board structure – two-tier or unitary (one-tier) – is governed by national laws. The German and Dutch companies in our study (i.e. the DBG companies and Euronext NV) have two-tier boards.[65] Deutsche Börse AG’s supervisory board conforms with German labour codetermination requirements.[66] LCH SA (French incorporated) and ENX Clearing (Italian incorporated[67]) make use of the optionality in their respective jurisdictions as between unitary or two-tier boards. The UK-incorporated members of the LSEG in our study (LSEG plc and LCH Ltd) have unitary boards in accordance with UK company law. Belgian corporate law generally permits a choice between a unitary or two-tier board structure but there is a special regime for banks and FHCs whereby members of the management committee (all in the case of a bank and three in the case of a financial holding company) must be board members.[68] As there is only one board, for simplicity in the tables we present the Euroclear boards as unitary.

Board size is affected by formal independence requirements.[69] For FMIs, at least one third, but no less than two, members of the board must be independent.[70] For banks, the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) does not specify a minimum number or proportion of independent directors but supervisory guidance provides that it is good practice for a bank to have at least one independent director and that significant banks should have a ‘sufficient number’ of independent directors.[71] In addition, committee composition requirements 18and guidance, which are discussed in the following sub-section, indirectly influence board size due to the de facto need for sufficient independent non-executive directors (INEDs) relative to the number of other non-executive directors (NEDs) and executive directors (EDs) to populate committees appropriately.

Independence expectations in national corporate governance codes are relevant to the listed parent companies in our study. Here, there is substantial jurisdictional variation. The UK Corporate Governance Code (UKCGC) (applicable to LSEG plc) recommends the chair be independent on appointment and for at least half the board, excluding the chair, be independent.[72] The Dutch Corporate Governance Code (DCGC) (applicable to Euronext NV) recommends the majority of the supervisory board members are independent.[73] The German Corporate Governance (GCGC) (applicable to Deutsche Börse AG) recommends more than half of the shareholder representatives on the supervisory board are independent from the company and the management board.[74] In addition, if the company has a controlling shareholder, at least two of the shareholder representatives should be independent from the controlling shareholder (or one if the board comprises six or fewer members).[75] While the Euroclear parent entities are not listed, the Belgian Corporate Governance Code (BCGC) is a best practice reference point. The BCGC expectation is for an ‘appropriate number’ of independent directors, with a minimum of three.[76]

Overall, the empirical evidence is contradictory[77] or inconclusive[78] on the underlying causal effects of bank board size on performance/risk management. We have not found relevant empirical studies of FMI boards. Analysis of board size in the FMI space is complicated by the fact that some major FMIs remain ‘user-owned, user-governed’ organizations, which tend to have larger boards. For instance, the user-owned, user governed behemoth US Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) has a board of 21 members.[79] CLS, the user-owned, user-governed global settlement infrastructure for FX, currently 19has a board of 20 members.[80] SWIFT, the leading provider of secure financial messaging services, which is structured as a Belgian cooperative, has a large board of 25 members.[81] All in all, while size cannot be dismissed as entirely irrelevant – every organization needs a board that is large enough to be effective but not so large as to be inefficient – those bank corporate governance studies that indicate that board size alone is not a critical factor in performance or risk management also seem apt in the FMI context.

4.3. Board Committees

CSDs must establish risk, audit and remuneration board committees each chaired by a person with appropriate experience and independence from the executive directors, typically an independent non-executive director (INED).[82] The majority of members of each committee must be non-executive.[83] CSDs are also required to have user committees comprised of representatives of issuers and participants from each of their securities settlement systems.[84] User committees are entitled to provide independent advice to the management body on key arrangements that impact on their members, including the criteria for accepting issuers or participants into the system, the service level and pricing structure.[85] Although user committee advice is not binding, they can inform the competent authority if it is not followed.[86] CSDs are also obliged to disclose when decisions have been taken that do not follow the advice of the user committee.[87] This creates the possibility of supervisory intervention and illustrates our point that supervisors can help curb managerial tendencies to prefer shareholder interests at the expense of other stakeholders. However, due to an absence of user committee data, we have not tested this empirically.

20CCPs are required to have audit and remuneration committees but unlike CSDR, EMIR does not specify eligibility criteria for committee membership.[88] CCPs are also subject to the requirement for a special type of risk committee.[89] CCP risk committees should be composed of representatives of the CCP’s clearing members, independent members of the board and representatives of its clients.[90] None of these groups may have a majority on the committee.[91] Competent authorities may request to attend risk committee meetings in a non-voting capacity and to be duly informed of the activities and decisions of the risk committee. Like the user committee for a CSD, a CCP’s risk committee is able to provide independent but non-binding advice to management on arrangements that may affect the risk management of the CCP.[92] Similarly, the CCP’s competent authority can be drawn into situations where management does not follow the advice of its risk committee.[93] The risk committee shall inform the board in a timely manner of any new risk affecting the resilience of the CCP and likewise, reasonable efforts must be made to consult the committee in emergency situations, including on developments relevant to clearing members’ exposures to the CCP and interdependencies with other CCPs.[94]

The multi-stakeholder structure of the risk committee relates to the distinctive CCP default management mechanisms, which include margin requirements and pooled funds contributed by participants to cover exposures that are not covered by margin calls. Paolo Saguato has argued for a stronger and more binding voice to be given to CCP members as the final risk bearers.[95] It remains questionable whether strengthening the voice of CCP members is compatible with directors’ fiduciary duties on decision-making or – for CCPs that hold banking licences – with regulatory requirements on bank/ FHC director suit21ability that relate to independence of mind.[96] Establishing whether the public interest goals of financial regulation is best served by greater empowerment of CCP members would require close examination of whether the incentives of those members are any more or less aligned with the public interest than those of shareholders.[97] In defence of the status quo, it can be argued that the board of a CCP, including those members that are shareholder-nominated, has strong incentives to prioritize the stability of the broader financial system, not only to protect its regulatory licence, but also to maintain its franchise value, which is predicated on trust in its reliability as a risk manager.

Banks that are significant in terms of size, internal organization and complexity are required to have a nomination committee comprised of non-executive directors and a remuneration committee constituted to enable it to exercise competent and independent judgment (which effectively limits eligibility to non-executives).[98] These requirements apply to those significant CCPs and CSDs that hold banking licences. The chair and the majority of members of a bank remuneration committee should be INEDs.[99] An independent chair is also a good practice requirement for bank nomination committees and is expected for the largest banks (G-SIIs and O-SIIs).[100]

Banks are also required to have a risk committee and an audit committee, comprised of non-executive directors.[101] Smaller/less complex banks may combine their audit and risk committees – see, for example, Eurex Clearing (Table 2), which holds a German banking licence and which has a combined audit and risk board committee as well as a separate CCP risk committee.[102] In the largest banks (G-SIIs and O-SIIs) the chair of the risk committee is expected to be independent and the committee should include a majority of members who are independent (while in other significant institutions a ‘sufficient number’ of INEDs is enough).[103] In all cases, the chair of the risk committee should be neither the chair of the management body nor the chair of any other committee.[104] A 22direct reporting line from the chief risk officer to the chair of the risk committee reinforces the ability of the committee chair to take an independent but fully informed view.

The law that requires banks to have audit committees also extends to listed companies and is thus applicable to the listed parent companies in our group.[105] As public interest entities, audit committees of banks, insurance companies and listed companies are to be composed of non-executive directors, and a majority of these are to be independent directors.[106] The chair must also be independent.[107] At least one member of the audit committee is required to have competence in accounting and/or audit.[108] In the aftermath of the Wirecard scandal, Germany passed the Financial Integrity Strengthening Act, which requires public interest entities’ audit committees to have at least two financial experts, one with expertise in accounting and the other with expertise in the field of auditing.[109]

The UK (for LSE), German (for Deutsche Börse AG), and Dutch (for Euronext) corporate governance codes provide also for nomination committees[110] and remuneration committees[111] in the context of listed companies. There are differences in the extent to which these codes expect committees to be chaired and/or comprised of independent directors.[112]

This section has demonstrated the importance of independence as a factor that determines board size and shape. The implications of a lack of a single, stan23dardized notion of the optimal number or proportion of independent directors and of significant variance in degrees of ‘hardness’ of applicable independence requirements merits closer examination. Glossed over up to this point is the multiplicity of applicable independence criteria that vary both in form and content. In the next section, we explore the myriad of complex independence requirements that must be navigated alongside seeking to achieve a balanced board with a dynamic mix of personalities and the right technical skill set.

5. Board and Board Committees: The Composition Challenge

Nachemson-Ekwall and Mayer stress the importance of getting board appointments right as, in the event of failure, “no other aspect of corporate governance – monitoring, measurement or incentives – can fully rectify the damage”.[113] ‘Who is the ‘right’ appointment?’ will never be simply a person-specific question since ‘rightness’ depends on the qualities that an individual brings to the overall skills matrix and what they add to the diversity of the board as a whole.

Diversity and skills’ expectations are growing for companies in general and for FMIs in particular. FMIs increasingly face cyber risks to which they must be alert and prepared. Furthermore, the speed of technological development necessitates rapid innovation in areas including blockchain, distributed ledger technologies (DLT), tokenization and digital currencies, to identify scalable ways of doing business differently. Digital expertise has become a priority for FMI boards but broadening the range of skills, knowledge and experience while keeping board size manageable and maintaining governance efficiency is difficult. ESG is another pertinent example of the expanding set of expected skills. New demands come along but old ones rarely drop off. All of which makes it imperative that importance attached to one criterion does not crowd out other important criteria by excessively restricting director eligibility. It is with this thought in mind that we explore independence criteria and their relationship with other elements that go towards the composition of a well-balanced board.

5.1. 24Directorial Suitability: Independence

There are two concepts of independence relevant to this discussion: ‘being independent’ and ‘independence of mind’. Being independent, also described as formal independence, is typically determined according to proxies that contra indicate independence, such as employment, business or family relationships and ties. Independence of mind is different in that it denotes a quality of mind that is expected of all directors regardless of whether they are, in the formal sense, independent directors. Initially our focus is on the first limb: formal independence.

5.1.1. Formal Independence

Financial regulation attributes an explicit public facing trustee-like role to independent directors by looking to them to help ensure that the interests of all internal and external stakeholders are considered, and that independent judgment is exercised in conflict-of-interest situations.[114] Independent directors in the financial sector thus complement supervisory oversight in ensuring that stakeholder interests are appropriately factored into the way businesses are run.

Who or what are the independent directors of the companies in our focus groups expected to be independent from?[115] From the corporate law starting point of viewing independent directors as a solution to agency problems, independence from executive management and/or controlling shareholders is the obvious answer to this question.[116] However, since independent directors of FMIs and banks have responsibilities towards a broader range of stakeholders, additional indicators of (lack of) independence that take account of relationships with members (CCPs) and customers and suppliers (CSDs/banks) are also required.

As already noted, Tables 1 and 2 oversimplify the formal independence concept by glossing over the multiple different definitions/interpretations that are applicable. The body of law, supervisory guidance and best practice applicable to the companies in our focus group contains a plethora of different approaches to defining independence indicators depending on type of business 25(CSD, CCP, bank, FHC, other parent company), whether or not listed, and jurisdiction of incorporation. That such differences exist is an issue that deserves attention. Does it make sense for the formal independence criteria for CCPs and CSDs to be different from those for banks (and investment firms)? Is difference justifiable because it reflects an appropriately nuanced regulatory response to variations in business models and avoids the ‘one approach fits all’ mentality? Or is the reality that the differences are a product of fragmented rulemaking and insufficiently joined up thinking? And if, or to the extent that, the differences are not rooted in rationality, are there material implications for talent pools? The inadvertent narrowing of talent pools could have outsized impact for the FMIs in our study group. This article has discussed that the FMI post-trade market is dominated by a small number of large operators that function as hubs of densely interconnected networks within and across markets and is characterised by limited competition. If effectively the entire sector is in some way a user of a large CCP or CSD’s services and the applicable independence criteria exclude users and their senior officers, finding eligible directors with the relevant skills, knowledge and experience could be very challenging.

The definition of formal independence that applies in the CCP context is a mandatory one focused on the director not having, or having had in the preceding five years, a family, business or other relationship that raises a conflict of interest with the CCP or its controlling shareholders, its management or its clearing members.[117] There is no equivalent legislative definition of directorial formal independence for CSDs but ESMA has stated that the definition provided for in other Union legislation is to be taken into account and that the CCP definition is applicable.[118] Unlike in relation to banks (detailed below), there is no explicit mechanism for a CCP or CSD to argue that a person who is in a relationship that raises a conflict of interest issue should nevertheless still be treated as an independent director. A five-year sanitisation period covering ties with members, management and shareholders is long in time and broad in scope, especially for those large FMIs that are major hubs to which many financial market participants are connected. The specialized nature of clearing and settlement businesses means the pool of those with adequate technical understanding is unlikely to be deep, so barring industry specialists from serving as independent directors until their specialist knowledge has become quite stale could be counterproductive.

26Formal independence is not a mandatory requirement in EU banking law and it is addressed only in the non-binding joint ESMA/European Banking Authority (EBA) Suitability Guidelines.[119] Under the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines the overarching test is that lack of independence is indicated by “present or recent past relationships that could influence the member’s objective and balanced judgement and reduce the member’s ability to take decisions independently”.[120] This is supplemented by a prescribed list[121] of circumstances in which a lack of independence is presumed, subject to a ‘comply or explain’ mechanism whereby on a case-by-case basis a board can rebut the presumption by demonstrating why the member’s ability to exercise objective and balanced judgment and to take decisions independently is not affected by the circumstances.[122] The final say on this will lie with the bank’s supervisor in its supervisory F&P assessment.

National supervisory authorities and financial institutions are expected to make every effort to comply with the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines but national supervisors can depart from full compliance by using the comply or explain mechanism.[123] The German Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) has used this mechanism not to comply with the Suitability Guidelines with respect to formal independence.[124] The BaFin takes the view that the formal independence criteria in the Suitability Guidelines are too re27strictive and narrow the institution’s room for manoeuvre disproportionately when appointing supervisory board members. It also flags the possibility of conflicts with German labour and co-determination laws as well as State laws relating to public savings banks. The Banque de France also reserves its position on several points relating to the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines.[125] The Banque de France notes that in French law, failure to comply with one or more of the criteria listed in the Suitability Guidelines does not constitute a presumption of non-independence. Analysis of independence must also consider other measures, in particular those that would be developed by French institutions in the context of laws and regulations in force and which could achieve the same objective of independence. On the other hand, the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) has withdrawn its reservations to the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines.[126] Luxembourg intends to comply and has not made any reservations.[127] The ECB in its role as direct supervisor of significant credit institutions within the Single Supervisory Mechanism applies the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines but only where formal independence is envisaged by national law.[128]

That some national supervisors and the ECB depart from the interpretation of formal independence in the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines in this way speaks to our concern that the rigid application of prescriptive requirements could inadvertently and excessively narrow the talent pool. While our work has not allowed us independently to test whether the BaFin’s concern about undue restrictiveness has substance, it is a powerful statement for a supervisor to have made. Although non-compliance by national supervisors with guidelines issued by the European Supervisory Authorities is permitted, it is not common.[129]

28In the absence of unequivocal evidence that director independence fosters both better performance and lower risk,[130] a relatively flexible approach seems appropriate to avoid giving too much weight to formal independence at the expense of specialist expertise. This assessment is not fundamentally at odds with the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines since general compliance by supervisory authorities still leave rooms for case-by-case requests for a director to be considered independent notwithstanding that an indicator of lack of independence is met. It would be interesting to know more about whether banks make material use of this option and if they do, how do supervisors react. For example, are sanitization periods rigidly observed or is there a willingness to look at the substance of current relationships in circumstances where a previous formal connection ended at some point short of the required period? More transparency with respect to both firm and supervisory practice in this area would help in determining whether an optimal degree of flexibility is achieved in practice, and in monitoring for arbitrariness or other misuse in the exercise of significant supervisory discretionary power.[131]

The difference in approach between the guidelines-based framework for testing the formal independence of bank directors and the legislative framework for CCPs and CSDs also calls for comment. For FMIs that hold banking licences, overlapping requirements that have the same aim but differ in detailed respects represent an additional regulatory burden that could conceivably further constrict the directorial talent pool without a counterbalancing public interest gain. The five-year sanitization period that is applicable in the CCP/CSD context stands out as especially idiosyncratic. Yet rather than merely shortening the sanitization period, our preferred approach for testing formal independence of CCP and CSD directors would be for consideration to be given to shifting to a more flexible guidelines-based approach that is similar to that for banks, adapted as appropriate for context.

For the listed parent companies in our study, the applicable national Corporate Governance Codes provide further interpretations of formal independence. Corporate governance codes are oriented towards the traditional corporate law agency problems (directors and majority shareholders) and this orientation is reflected in the independence tests. The UKCGC provides a non-exhaustive list of circumstances and if one of these is present the board must 29provide a clear explanation for treating the director in question as independent.[132] The DCGC also provides a list of circumstances demonstrating lack of independence.[133] Independence under the GCGC covers both being independent from the company and its management board, and being independent from any controlling shareholders.[134] In a comply of explain framework, supervisory board members are to be considered independent from the company and its management board if they have no personal or business relationship with the company or its management board that may cause a substantial – and not merely temporary – conflict of interest.[135] The chairs of the supervisory board, the audit committee and the remuneration committee are to be independent from the company and the management board.[136] However, an expectation for independence from the controlling shareholder applies only to the chair of the audit committee.[137]

The Belgian parent companies in our study are not listed companies and hence not directly covered by the BCGC but as FHCs they are covered by Belgian banking law, which applies independence criteria that are broadly consistent with the BCGC as well as with the ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines.[138]

5.1.2. Independence of Mind

CRD, but not CSDR or EMIR, expressly requires directors to display independence of mind.[139] Independence of mind pertains to the exercise of inde30pendent judgement[140] and is evidenced through behavioural skills including courage, conviction and strength, the ability to ask questions and resist group-think.[141] Independence of mind is an ongoing requirement, and represents a standard by which directors are required to operate, whether they are considered to be formally independent or not.[142] Directors must be willing to challenge a popular view and express a distinctive position or risk falling short of the independence of mind requirement. Admittedly, it would take considerable discretionary judgement to determine that a person is unsuitable because of a lack behavioural skills such as courage or strength. This is a weakness of the independence of mind test of directorial suitability compared to the objective tests of formal independence. The strength of the independence of mind tests lies in the onus it places on the individual director to demonstrate independence behaviorally on an ongoing basis, as opposed to relying entirely on proxies prior to appointment. Assessing and verifying independence of mind becomes a matter to be established (or otherwise) ex post. Once independence of mind is called into question, evidence of behavior(s) that indicate a lack of courage, conviction or strength (for example), may be read alongside adverse interests, including those covered by formal independence tests, as potential indicators of lack of independence of mind.

The independence of mind requirement and rules relating to the management of conflicts of interest coincide to an important degree. Independence of mind requires the absence of conflicts of interests which may impede a director’s ability to perform their duties.[143] In broad terms, “there is a conflict of interest if the attainment of the interests of the appointee adversely affects the interests of the supervised entity”.[144] Conflicts are assessed according to a list of scenarios such as economic interests, personal relationships, employment and political influence.[145] ECB guidance on the independence of mind criterion includes a number of situations and thresholds where there is a presumption that a conflict of interest exists.[146] However, a director who never has a view of their own and always goes along with the most powerful voice in the room could be perfectly free of conflicts yet still be said to lack independence of mind.

5.1.3. 31Do We Need Both Formal Independence and Independence of Mind?

Applied proportionately, both concepts of independence can add value to the construction of a board that is effective for its stakeholders. The independence of mind requirement is an essential adjunct to the effective operation of governance arrangements relating to the management of conflicts of interest.[147] Authentic application on an ongoing basis of the ‘independence of mind’ concept, to the extent it can be reliably tested, may be more effective than an assessment of who a director has had connections with at the time of appointment and reappointment. In our view, therefore, the fact that there is no explicit independence of mind regulatory requirement applicable to directors of CCPs and CSDs is an anomalous gap in regulatory coverage.[148] While there is some overlap with general corporate law fiduciary duties relating to the exercise of independent judgment and avoidance of conflicts of interests, these private law duties, which are owed to, and enforceable by, companies, are not an adequate substitute for regulatory commitments overseen by supervisors and enforced by means of rigorous fitness and propriety suitability assessments and other supervisory processes. A more effective regulatory approach, we suggest, would be to make independence of mind the baseline for directors of all companies within our focus group, supplemented by flexible formal independence requirements that can respond to demands of context and allow for the appropriate prioritization of expertise. Supervisory guidance is a more appropriate instrument than hard law to provide a framework with the requisite degree of flexibility. A broadening of academic research to include a greater focus on the personal qualities and characteristics that influence directors’ ability to maintain an independent perspective is also called for.[149] The question posed by Mehran and others[150] – “How do we assess whether board members exercise intellectual independence in carrying out their duties?” – deserves greater attention.

5.2. 32Directorial Suitability: Expertise, Diversity and Time Commitment

In advocating for a flexible approach to formal independence supplemented by a more generally applicable independence of mind regulatory criterion we draw support from academic literature that has questioned the emphasis on formal independence tests.[151] Hambrick et al argue that the ideal director will have all of four qualities: independence, expertise, motivation and bandwidth.[152] However, this quadrilateral model asks a lot of a single individual and those who present all qualities in equal measure are likely to be quite rare. Realistically, composing an effective board will involve looking for a distribution of desired qualities across the board collectively, factoring in the trade-offs involved in emphasizing one quality over another, especially the trade-off between formal independence and expertise. Diversity is a fifth desirable quality that involves looking at the whole board, rather than individual directors. We consider these qualities and their regulation below.

5.2.1. Expertise

A lack of expertise may inhibit effective monitoring[153] and the provision of advice and counsel.[154] An independent director’s level of expertise can impact on their credibility leading to “a negative dynamic” with the executives.[155] On the other hand, lack of independence within a board and the consequential need to manage conflicts of interest procedurally, may erode board collegiality by requiring individual directors regularly to absent themselves from discussion of certain topics; or may even disrupt information flows by fostering a 33defensive attitude amongst executives regarding what that they are willing to share.

The German Financial Integrity Strengthening Act exemplifies the impetus towards regulating for more specialist expertise, requiring financial experts on the audit committees of public interest entities. In the FMI context specialist expertise is particularly salient because the industry is arcane, technology heavy, technically complex, and critical in purpose. Good induction and ongoing training can bring all board members up to a certain level of technical understanding, but it cannot substitute for years of intensive professional experience in the industry itself. This implies that the well-composed board that is collectively able to understand and make decisions about an FMI’s activities, business model, risk appetite, strategy, markets, operational threats, legal and regulatory environment and so on, requires adequate industry expertise around the table; and also that at least some of this expertise should be located with non-executive directors to enable them to effectively challenge the executive management as necessary.[156] At the same time, broader skills, knowledge and expertise expected of directors (e. g. in accounting and audit, governance, firm culture and values, or people management) are more transversal and could be acquired from a wide range of professional backgrounds, both inside the financial sector and beyond. This transversal quality is also true of rising expectations for directorial knowledge, skill and expertise in areas such as the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda,[157] data, digitalization and cyber security, and money laundering and terrorist financing.[158] The DCGC captures the rising trend with its note that “Sustainability and digitisation are not separate or supporting processes, but go to the heart of the company’s strategy and business operations [... and it] is important to pay attention to this in the composition of the management board and the supervisory board, as well as in the periodic training and education”.[159] Requirements that restrict the eligible pool of candidates need to be carefully calibrated to ensure that they do not do more harm than good.

Beyond a certain minimum threshold level, exactly what constitutes appropriate expertise at an individual level will be a judgment question that depends on the specific institutional context and mix of qualities present in its board’s collective skills matrix. Putting it another way, expectations of individual and collective expertise are best considered in tandem, since one shapes the other. The 34collective dimension is explicitly mentioned in the CRD context[160] but EMIR, which refers to the board, including its independent members, having ‘adequate expertise in “financial services, risk management and clearing services”[161] and CSDR, which refers to “an appropriate mix of skills, experience and knowledge”[162] could be clearer on this point.

The ESMA/EBA Suitability Guidelines for banks amplify the expectations with regard to expertise but they do so in a way that strives to walk a careful path between supporting efficiency and consistency in suitability assessments and imposing ‘tick box style’ de facto uniformity.[163] The ECB in its guidance as a bank supervisor also leaves room for differentiation for type of role, type of institution and specialized requirements, and allows for justification where an appointee is found to be lacking in some area, for example by reference to a training plan or the board’s overall collective suitability.[164] However, there are also instances where supervisory guidance on expected boardroom skillsets assumes a harder edge, for example around climate and environmental issues,[165] or with respect to information technology and security and management of risks related to money laundering and terrorist financing.[166] Care is needed to strike a workable regulatory and supervisory balance between influencing boardroom change to ensure that there is adequate relevant expertise to address new topics and growing areas of concern while not intruding so far into matters of eligibility as to make the task of finding suitable directors as elusive as the search for the holy grail.

5.2.2. Diversity

A notable mandatory requirement for banks, and CSDs (but not yet CCPs) is for board diversity policies and/or gender targets.[167] Under Belgian law this 35requirement extends to the Euroclear parent entities as financial holding companies.[168] The requirement embraces educational and professional background diversity, in addition to the more traditional factors of gender and age, but with emphasis on gender balance.[169] Geographical provenance is also singled out, in particular for institutions that are active internationally.[170] Other aspects of diversity such as ethnicity and disability are not referred to. Though arguably incomplete and relatively toothless, the requirement to have a policy or set a target helps by establishing diversity expectations whilst leaving room for institutions to tailor goals to their own circumstances. Such an approach is tenable given the complex matrix of director requirements needed in the FMI sector and the fact that our study group are already relatively advanced in respect of gender diversity. Table 1 indicates that a 40 percent target has already been achieved or is within reach for all the parent companies in our group, at least at (supervisory) board level. Progress among executive directors/managing boards (Table 1) and within groups (Table 2) is more variable.

The EU listed companies in our sample are subject to the mandatory requirement that, by 30 June 2026, they have a board composition in which members of the underrepresented sex hold; (a) at least 40 percent of non-executive director positions; or (b) at least 33 percent of all director positions, including both executive and nonexecutive director.[171] The UK takes a more flexible approach, adopting the comply or explain model for listed companies to disclose against a 40 percent gender target for boards and senior management and require at least 1 senior board position to be female and at least one to be an ethnic minority.[172]

The case for the soft law regulation of diversity is defensible notwithstanding the additional complexity added to the search for suitably qualified persons to serve as directors of FMIs. At a minimum, and given supervisory concern about the lack of vigour with which diversity on management teams and 36boards of banks is pursued,[173] we can see no good reason for CCPs not to adopt the same approach as CSDs and banks.

5.2.3. Time Commitment

Boards will not function well if they are populated by directors who have so many directorships that they are unable to give each of their mandates the required amount of attention. This has come to be known as the ‘overboarding’ problem. The time that a director can commit to their mandate will naturally be of interest both to the company’s shareholders and to its supervisor as part of F&P suitability assessment and ongoing oversight after appointment. However, for the significant banks in our study, overboarding is also addressed by a mandatory quantitative rule that limits the number of directorships an individual may hold (four NED roles or one ED role and two NED roles[174]).[175] Interestingly, in the Belgian case (and thus relevant to Euroclear) the flexibility for Member States to apply the CRD directorial suitability requirements to FHCs accounting for their specific role, has resulted in the quantitative limit not being applied.[176]

The precautionary stance inherent in having a prescribed quantitative limit on mandates derives support from studies linking overboarding with underperformance and/or higher risk-taking, particularly in larger, more complex companies where directors’ have enhanced risk monitoring responsibilities.[177] Notwithstanding some contradictory findings in the literature, Kress argues that “on balance, the weight of the evidence strongly suggests that busy directors are associated with worse performance and higher risks in large financial firms”.[178] In view of the compelling evidence that overstretched directors detract from good corporate governance, it is hard not to see legitimacy in the EU’s quantitative limit for significant banks notwithstanding its potentially 37limiting effect on the size of the eligible directorial talent pool. However, to go significantly further could be problematic. Kress argues that the US should follow the EU in regulating overboarding but that it should impose even more stringent restrictions on key directors (lead INED, risk committee chair and audit committee chair) and counterbalance the foregone professional opportunities that result from such restrictions with substantially increased directorial remuneration.[179] One concern that we have with this proposal is that tighter restrictions could disproportionately hit recruitment in areas where talent is scarce (such as ESG or digital) or from women, ethnic minorities or other groups that are underrepresented at board level, thus contributing to incoherence between policy priorities. With considerations relating to harmony between policy objectives in mind, a case could be made for introducing greater flexibility into the regime for significant banks – making limits a matter for supervisory guidance rather than hard law and/or providing more room for the limit to be increased on a case-by-case basis or for it not to apply to certain roles (as in the case of FHCs).[180] In the interests of cross-sectoral consistency, consideration could also be given to whether there is a convincing rationale for CCPs and CSDs not to be subject to the same EU-wide time commitment framework as banks.

6. Conclusion

This article is the first to consider the variations in governance requirements applicable to European FMIs. We have charted the tangled combination of laws, codes and regulations that apply to the governance of the largest European CCPs, CSDs and ICSDs and found variation that depends on business type, ownership structure, jurisdiction, and institutional size. Given the similarity of these institutions in terms of their sector, criticality, complexity and purpose, we question the extent to which the variation in regulation is an appropriate reflection of differing requirements or a by-product of piecemeal regulatory reform in the shadow of the financial crisis. We conclude that there are examples of both kinds of variance and, in the case of those consequent to piecemeal reform, we call for a more consistent approach to the regulation of FMI governance.

38We see no apparent need for change to bring about consistency of board size or structure, nor in relation to specificities of committee requirements. These provide necessary flexibility that recognize the nuance in business operations. However, there are convincing arguments that change is needed around the meaning and application of independence, with a more flexible application of formal tests of independence and a greater focus on independence of mind. We suggest that the current approach to FMI directorial independence is a poor fit given the sectors highly technical nature, its interconnectedness, and the limited pool of available expertise. Specifically, we argue for (i) reconsideration of the tests of formal independence in the FMI context potentially leading to closer alignment with the directorial independence tests for banks; (ii) more flexible application of the formal independence tests supported by greater transparency of supervisory practice in this matter; and (iii) greater prominence to be given to the independence of mind requirement, which we regard as being wide enough to cover not only adverse interests but also unwillingness to challenge groupthink.

We further argue that expertise, diversity and commitment can be trade-offs for adherence to the requirements of independence. Regulation needs to be sensitively calibrated to ensure these important factors in governance arrangements do not get squeezed out under the weight of formalized independence. Our preferred approach to the application of independence requirements would create more room for boards to be constructed on a balanced basis in which independence, expertise, diversity and commitment can be weighed against each other in context.

Note

We are grateful to Professor Franco Passacantando for his insightful comments on an earlier version and to others with whom we have been able to discuss our ideas. All remaining errors and omissions are our own responsibility.

© 2024 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- The Regulation of Corporate Governance in European Financial Market Infrastructures: A Critique

- Duty of Loyalty: Corruption of Company Directors and Prohibition of External Remuneration

- Cybersecurity and Online Formation of Companies in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany

- The Strategic Importance of Public Recapitalisation in Banking Resolution, What Ireland Can Tell

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- The Regulation of Corporate Governance in European Financial Market Infrastructures: A Critique

- Duty of Loyalty: Corruption of Company Directors and Prohibition of External Remuneration

- Cybersecurity and Online Formation of Companies in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany

- The Strategic Importance of Public Recapitalisation in Banking Resolution, What Ireland Can Tell