Pilot investigation into the influence of racial implicit bias on physician clinical reasoning

-

Cristina M. Gonzalez

, Maria L. Deno

, Tavinder K. Ark

, Miriam Helft

, Adina L. Kalet

, Diana J. Burgess

, Malika T. Samuel

, Marla R. Fisher

and Steven J. Durning

Abstract

Objectives

Evidence for the impact of racial implicit bias and clinical reasoning remains conflicting. Our inability to characterize the relationship between racial implicit bias and clinical reasoning (CR) precludes development of comprehensive interventions seeking to address the impact of racial implicit bias on clinical encounters. To address this gap, we conducted a simulation-based investigation with clinical presentations with known health disparities, cognitive stressors common to clinical environments, and Black and White standardized patients (SPs).

Methods

We recruited 75 early-career generalist physicians from five academic medical centers in New York, NY, USA. Physicians engaged in a three-station simulation. The first was for level-setting, familiarizing physicians with the online platform. The second was a diagnostic dilemma – an atypical presentation of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The third tested treatment decision-making in acute pain. Immediately afterward, physicians completed the Race Implicit Association Test (IAT) and Race Medical Cooperativeness (RMC) IAT measuring affective and cognitive implicit biases, respectively. Two investigators assessed CR accuracy by applying a scoring rubric to physicians’ post-encounter notes.

Results

Statistical analyses revealed no significant correlations between physicians’ Race-IAT scores and CR by SP race. However, for ACS, a moderate correlation was suggested between physicians’ RMC-IAT scores and CR accuracy when seeing Black (R=0.36, CI −0.04 to 0.6), but not White, SPs (R=0.1, CI −0.44 to 0.24).

Conclusions

This study expands our understanding of the complex impact of racial implicit bias on clinical encounters. Future, larger studies should explore affective and cognitive implicit biases’ effects on CR across varied clinical scenarios and contexts with diverse SPs.

Introduction

Clinical reasoning (CR) refers to the complex cognitive process that enables clinicians to observe, obtain, and interpret information resulting in decision-making and action (both diagnostic and management decisions) [1]. CR occurs within contexts subject to the same societal and structural influences that lead to persistent racial health disparities [2], 3]: For example, unequal access to care, racial minorities being disproportionately cared for in under resourced health systems, and delays in seeking care due to mistrust or other factors contribute to racial health disparities and are contextual factors that can affect the clinical encounter [4], [5], [6]. Racial disparities in diagnostic accuracy and timeliness of diagnosis have been demonstrated [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Disparities are present in both diagnostic and management decisions when physicians are caring for Black patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and acute injury requiring pain management [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19].

It remains unknown if racial implicit bias impacts clinicians’ clinical reasoning (CR) and causes it to vary when seeing patients from different social groups (e.g. different races), and therefore if such variations in CR may contribute to known racial healthcare disparities. Studies exploring racial implicit bias as a contributor to disparities in CR have yielded conflicting results. Some investigators have found associations between clinicians’ implicit bias and disparities in CR [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], while others have not [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Characterizing the relationship between racial implicit bias and CR could identify the patient’s racial background as a contextual factor and then guide the design of CR interventions to support equitable diagnostic and treatment decisions, and ultimately, health equity.

In contrast to the conflicting research on racial implicit bias and its potential impact on physicians’ CR, there is robust evidence of the association between racial implicit bias and disparities in physician communication when seeing Black and White patients [34], [35], [36], [37]. At least three explanations for the relative strength of the evidence for the influence of implicit bias on physician communication have been proposed. First, most communication studies have been conducted in real world practice settings, in contrast to most CR studies, which evaluate physicians’ reasoning using paper or computer-based clinical vignettes. In real-world practice settings, physicians work under conditions riddled with cognitive stressors such as time constraints, environmental stressors such as noise, interruptions from both staff and the electronic health record notifications, and fatigue, among others. These stressors increase cognitive load, enhancing the probability that physicians will use heuristics – cognitive shortcuts more vulnerable to implicit bias – to guide their CR [25]. When, in real world practice settings, these stressors are combined with clinical ambiguity and increased complexity of tasks, both communication skills and CR are more likely to be influenced by racial implicit bias [38], [39], [40], [41]. On the other hand, research suggests that in low stress conditions, such as when responding to paper- or computer-based clinical vignettes, physicians are able to tap into their conscious egalitarian values and resist the influence of implicit bias on their decision-making processes [25], 29], 39]. Second, because communication may be a more automatic and affective and less cognitive and deliberate than CR it may more likely be impacted by implicit bias, regardless of the context in which it is studied. And thirdly, unlike communication challenges, the quality of CR may be more dependent on the specifics of the clinical situation [42]. For instance, CR in established conditions such as hypertension, which are linked with objective, guideline-driven approaches may be much less impacted by racial implicit bias than CR in highly ambiguous, uncertain situations [43].

To address the gaps in the literature, we previously conducted a high-fidelity simulation study to investigate the association between racial implicit bias and communication skills in physician volunteers when seeing Black or White standardized patients (SPs). Given the aforementioned known robust evidence of the association between communication disparities and racial implicit bias, we designed the simulations to include cognitive stressors and iteratively piloted and revised the simulations until they elicited the expected disparities in physician communication skills when seeing Black and White and SPs [44], 45]. In that prior work, we chose two clinical scenarios, one with ACS and the other with acute pain, due to the documented racial disparities in ACS diagnosis and treatment and also in pain assessment and management [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19, 22], 46], 47]. All three scenarios were iteratively developed with community member, SPs, members of the investigative team, and clinical experts. The ACS case presented a diagnostic dilemma which may have been more cognitively demanding [44], it had a stronger association with disparities in communication skills ratings received by physicians when seeing a Black or White SP than the acute pain case. The acute pain case, which was a treatment decision, did result in lower communication skills ratings by female Black SPs than White SPs, but this difference was not as strongly associated with physician racial implicit bias as the ACS case.

In this paper, we seek to characterize the association between racial implicit bias and physician CR when seeing Black or White SPs in otherwise identical clinical presentations. We hypothesized that physicians’ implicit bias would be associated with lower quality CR, inclusive of diagnostic and treatment outcomes when seeing Black SPs as compared to White SPs.

Subjects and methods

Subjects and setting

We recruited residents and junior faculty generalist physicians from five major academic medical centers in New York City. Physicians were not informed that the study was investigating the influence of racial implicit bias; physicians were only told that they were participating in piloting educational simulations. Potentially eligible physicians received email invitations from chief residents, program directors, and division chiefs. Those who were interested in participating were directed to a website via a QR code, where they were screened for eligibility (generalist physicians who were residents or within the first 5 years of their faculty appointment-interns were excluded) and if eligible, were given the opportunity to sign up for a specific date and time. We limited eligibility to early career physicians in adult general medicine disciplines to achieve similar experience levels among our study participants given that clinical experience impacts the experience of stress in authentic clinical practice settings (including clinical ambiguity). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Study procedures

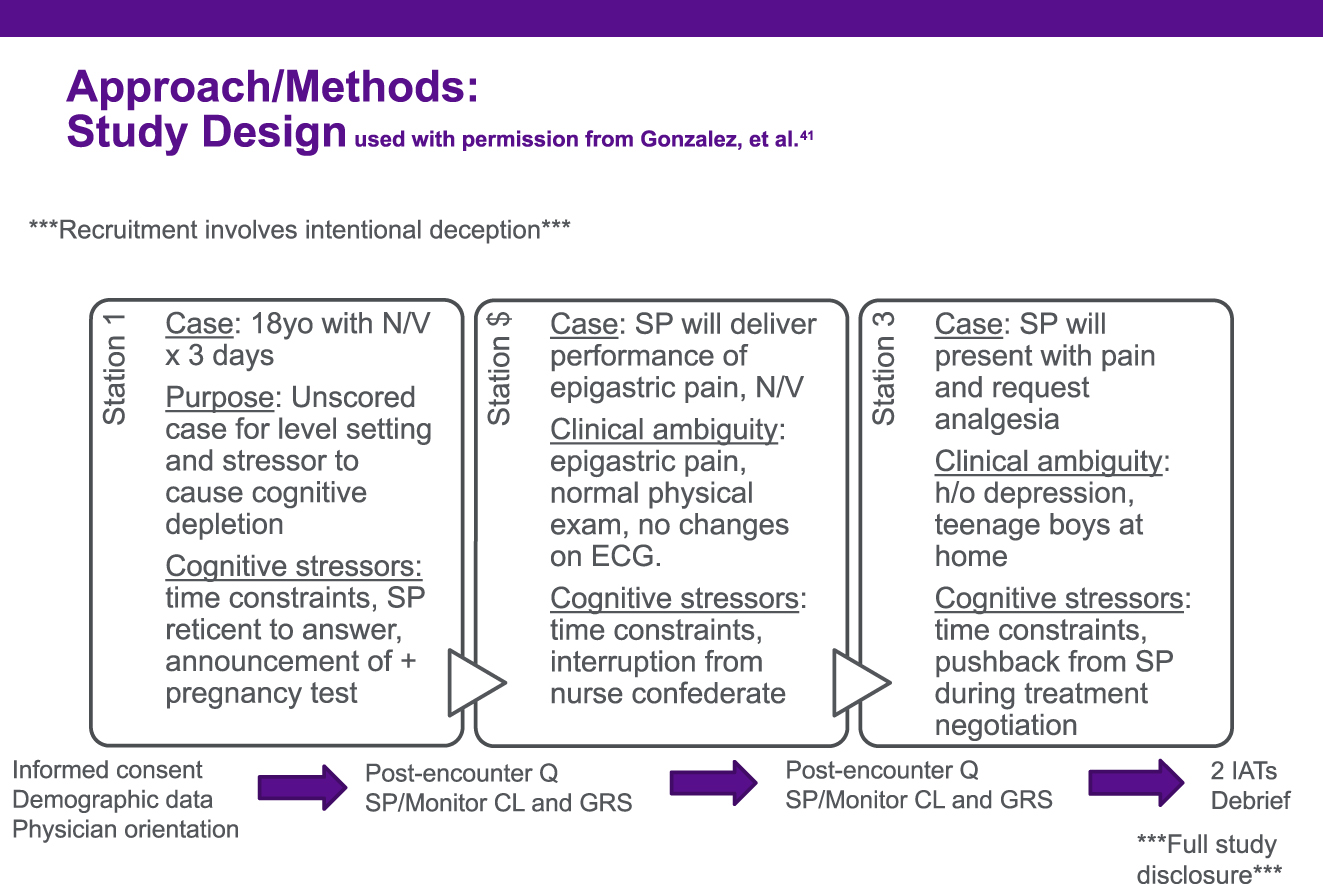

We developed and previously described a three-station simulation exercise [44]. Briefly, each scenario included cognitive stressors common to clinical environments (e.g., time constraints, interruptions, clinical ambiguity, etc.). Because the study began during the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitating virtual delivery, the first scenario was a level-setting scenario to familiarize physicians with the process of interviewing and examining SPs over a virtual platform (Zoom™). For the second scenario, we chose acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presenting with epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. SPs were trained to deliver a history – consistent with ACS – of a stuttering course of progressively worsening exertional epigastric discomfort lasting longer and occurring more frequently over the last few months, culminating in the presenting symptoms. SPs were not to offer this information, they had to be asked by the physician. The third scenario was a woman in acute pain who had tried alternating acetaminophen (1 g) and ibuprofen (400 mg) for up to six total doses a day (three doses of each medication) without relief of her pain that is discovered to be due a rib fracture through X-ray result read during the encounter. During the simulation, physicians interviewed and (virtually) examined SPs, discussed their diagnostic and treatment plans with the SP, and wrote a post-encounter diagnostic and treatment plan. Both physicians and SPs were blinded to the focus of the study on racial implicit bias. To prevent unblinding of physicians to the study including racial implicit bias and to foster natural behaviors when examining the SPs, the two IATs were completed after the final SP encounter. After completing the three SP encounters and two Implicit Association Tests (IATs), physician participants were debriefed on the study purpose. Study procedures are detailed in Figure 1.

Flow of procedures for early career generalist physicians participating in a three-station standardized patient exercise from 2022-2023. Q, questionnaire; SP, standardized patient; CL, checklist; GRS, global rating scale; IAT, Implicit Association Test.

Implicit Association Tests

Physicians completed the Race IAT [48]; this IAT reflects affective racial bias (prejudice) using timed associations with valanced words such as joy and evil. They subsequently completed the Race and Medical Cooperativeness IAT (RMC-IAT) which measures mental associations between race and cooperativeness with medical recommendations [28], 34], 44]. This latter IAT reflects cognitive biases (stereotyping) in a medical context using timed associations with words such as adherent and resistant; this RMC-IAT was initially developed by Cooper et al., [34]. IATs are scored by a continuous variable referred to as a D-scores, which for the purposes of interpretation, are divided into seven categories of pro-White (positive D-scores), neutral (−0.15 to 0.15), or pro-Black (negative D-scores) with the cutoffs of 0.35, 0.65, and >0.65, for slight, moderate, or strong preferences for the construct in the IAT, respectively.

Assessing CR accuracy

During a piloting phase with 28 physicians, we developed a rubric to score CR, our primary outcome, within each scenario. Physicians wrote a post-encounter note with their diagnostic impressions and treatment plans after each scenario. They were instructed to write with enough detail that a physician assistant would be able to carry out the plan. For each scenario, two investigators (CMG and FM in acknowledgments) independently read a subset of the post-encounter notes (n=14) and identified components of the diagnostic and management plans, representative of physician CR. They came to a consensus on a categorical and ordinal 4-point CR scoring with a score of 1 representing the most accurate CR based on the clinical history the SPs provide when asked the appropriate questions. They then applied these scores to the original 14 notes and an additional 14 notes. Scoring disagreements were resolved through discussion, which contributed to further refinement of the scoring rubric. With the initial 28 notes (scored from the pilot rounds used in developing the three-station simulation [44]), the investigators finalized the scoring rubric. The finalized scoring rubrics (Table 1) were independently applied by CMG and MLD to post-encounter notes written during this study.

Scoring rubric applied to physician written diagnostic and management plans to assess clinical reasoning (CR) accuracy in two simulated clinical cases.

| Definition | Scores awarded | Physicians n, % |

|---|---|---|

| ACS Case: CR accuracy score | ||

| – Dx: ACS- Physician sends to the Emergency Department (ED) immediately for unstable angina | 1 | 15 (20) |

| – Dx: possible ACS, but Physician keeps patient at Urgent Care Center to draw troponins to rule out NSTEMI, send patient to ED if positive troponins | 2 | 19 (25) |

| – Dx: rule out stable coronary artery disease: physician refers patient to outpatient cardiology or labs drawn but no follow up plan is established | 3 | 20 (27) |

| – Dx: any diagnosis related to gastrointestinal system. | 4 | 21 (28) |

| Acute pain case: CR accuracy score | ||

| – Offer opioids | 1 | 57 (76) |

| – Offer lower strength pain management (e.g. tramadol or less than 5 mg oral morphine equivalent) | 2 | 7 (9) |

| – Offer opioids if initial (non-opioid) pain management fails (patient must return) | 3 | 2 (3) |

| – Pain management without any opioids | 4 | 9 (12) |

| Acute pain case: video observation score | ||

| – Physician offers opioid for pain management; no SP prompting | 0 | 38 (51) |

| – Physician offers opioid for pain management; after SP prompting | 1 | 21 (28) |

| – Physician does not offer opioid for pain management; after SP prompting | 2 | 8 (10) |

| – Physician offers nonopioid for pain management; no SP prompting | 3 | 4 (5) |

| – Encounter ended before SP prompted physician for opioid | 4 | 2 (3) |

| – SP prompted physician for opioid, but encounter ended- no physician response | 5 | 2 (3) |

-

Distribution of n=75 physician’s primary diagnosis and initial diagnostic workup when seeing a 52 year-old-man presenting with nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain (acute coronary syndrome (ACS) case) and n=75 physician’s treatment plan when seeing a 48-year-old woman with acute fracture of the 8th and 9th ribs (acute pain case).

Assessing the discussion around opioid prescribing (secondary outcome)

For the acute pain simulation, we trained SPs to request Percocet if the physician did not offer an opioid for their rib fracture; they were trained to wait to ensure that the physician had made their treatment recommendation before sharing that their neighbor had advised that Percocet might help if the clinician does not recommend an opiate. To capture if the physician required this request by the patient before offering opioids for pain management, MH and CMG independently reviewed video recordings. The scoring rubric used for this secondary outcome is detailed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

A series of Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to assess the hypothesized relationships between physician IAT scores (Race IAT and RMC-IAT analyzed separately), with CR Accuracy and OP Behavior scores, analyzed separately by SP race (Black or White).

Results

A total of 75 physicians participated in the study. Due to technical difficulties, we are missing IAT scores for 2 physicians and one ACS CR score and two acute pain simulation scores. Table 2 lists demographic data for the full sample and Table 3 lists the physicians mean IAT and RMC-IAT scores reported by physician race and the race of the SP evaluated. Overall, Race IAT scores are more pro-White than RMC-IAT scores suggesting affective bias is stronger in this cohort than cognitive bias. Physicians who identified as White or other Race IAT scores in the moderate and strong range, respectively, while Asian and Black physicians’ scores were in the neutral range. Black SPs were seen by physicians with a mean RMC-IAT score at the top of the neutral range; White SPs were seen by physician with a RMC-IAT score at the lower end of slightly pro-White.

Demographic data for n=75 physicians participating in a simulation study investigating the impact of racial implicit bias on clinical reasoning from 2022 to 2023.

| Category | Subcategory | Count/info |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 39 |

| Male | 34 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Race | White | 32 |

| Asian | 29 | |

| Black or African American | 4 | |

| More than one race | 1 | |

| Unknown or Not Reported | 9 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic or Latino Hispanic/Latino |

70 5 |

| Age range | Ages 26–30 | 50 |

| Ages 31–35 | 22 | |

| Ages 36–40 | 3 |

Implicit Association Tests (IAT) scores of n=75 physicians who completed the measures as part of a simulations-based research study investigating the impact of racial implicit bias on clinical reasoning conducted from 2022 to 2023.

| Physician race | Mean physician race IAT score (±s.d.) | Mean physician RMC-IAT score (±s.d.) |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | −0.017 (0.131) | 0.079 (0.536) |

| Black | −0.090 (0.515) | −0.358 (0.290) |

| White | 0.328 (0.446) | 0.184 (0.357) |

| Other | 0.43 (0.421) | 0.204 (0.366) |

|

|

||

| SP race | Physician race IAT | Physician RMC-IAT |

|

|

||

| Black | 0.270 (0.403) | 0.121 (0.343) |

| White | 0.381 (0.475) | 0.185 (0.424) |

-

Data reports the average IAT scores and standard deviations of scores by physician race and by SP race for the race IAT and the RMC-IAT, race and medical cooperativeness IAT. IATs are scored by D-scores divided into seven categories of pro-White (positive D-scores), neutral (−0.15 to 0.15), or pro-Black (negative D-scores) with the cutoffs of 0.35, 0.65, and >0.65, for slight, moderate, or strong preferences, respectively.

Overall, there were no statistically significant bivariate correlations between Race IAT or RMC-IAT and CR scores or discussion of opioid prescribing scores by the race of the SP (Table 4). Physicians’ CR scores were moderately correlated with RMC-IAT (R=0.36, p=0.075, CI −0.04, 0.66) when seeing Black SP. In contrast, there was negligible correlation of RMC-IAT on decision-making scores when seeing White SP (R=0.1, p=0.537, CI −0.44, 0.24).

Pearson’s bivariate correlation between physician’s (n=75) clinical reasoning (CR) accuracy scores in an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) standardized patient (SP) case and an acute pain SP case and their offering of opioids (for the latter case) with physician’s Race Implicit Association Test (IAT) or Race and Medical Cooperativeness IAT (RMC-IAT) scores, by the SP’s race in a study conducted from 2022 to 2023).

| Row | Variable | IAT | Case-SP race | SPs | Pearson’s R | p-Value | Confidence interval, CI | Interpretation of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CR accuracy score | Race | ACS-Black | n=28 | 0.3 | 0.118 | (−0.08, 0.61) | Affective implicit bias may not be correlated with physician’s CR with Black SPs |

| 2 | CR accuracy score | Race | ACS-White | n=33 | <0.1 | 0.667 | (−0.27, 0.41) | Affective implicit bias may not be correlated with CR with White SPs |

| 3 | CR accuracy score | RMC | ACS-Black | n=25 | 0.36 | 0.075 | (−0.04, 0.66) | Although not statically significant there may be a moderate correlation between cognitive bias (stereotyping) and CR with Black SPs |

| 4 | CR accuracy score | RMC | ACS-White | n=33 | 0.1 | 0.537 | (−0.44, 0.24) | Cognitive implicit bias may not be correlated with physician CR with White SPs |

| 5 | CR accuracy score | Race | Acute Pain-Black | n=29 | <0.1 | 0.614 | (−0.28, 0.45) | Affective implicit bias may not be correlated with physician CR with Black SPs |

| 6 | CR accuracy score | Race | Acute Pain-White | n=30 | 0.3 | 0.107 | (−0.60, 0.07) | Affective implicit bias may not be correlated with physician CR with White SPs |

| 7 | CR accuracy score | RMC | Acute Pain-Black | n=27 | <0.1 | 0.995 | (−0.38, 0.38) | Cognitive bias may not be correlated with physician’s CR with Black SPs |

| 8 | CR accuracy score | RMC | Acute Pain-White | n=29 | 0.26 | 0.171 | (−0.57, 0.12) | Cognitive bias may not be correlated with physician’s CR with White SPs |

| 9 | Offering opioids | Race | Acute Pain-Black | n=28 | <0.1 | 0.106 | (−0.30, 0.44) | Affective bias may not be correlated with physicians offering opioids to Black SPs |

| 10 | Offering opioids | Race | Acute Pain-White | n=30 | 0.3 | 0.106 | (−0.60, 0.07) | Affective implicit bias may not be correlated with physicians offering opioids to White SPs |

| 11 | Offering opioids | RMC | Acute Pain-Black | n=26 | 0.14 | 0.479 | (−0.26, 0.50) | Cognitive bias may not be correlated with physicians offering opioids to Black SPs. |

| 12 | Offering opioids | RMC | Acute Pain-White | n=29 | 0.22 | 0.249 | (−0.54, 0.16) | Cognitive bias may not be correlated with physicians offering opioids to White SPs. |

Discussion

We conducted the first, to our knowledge, high-fidelity simulation study to investigate the relationship between implicit bias and CR as assessed by scoring of physician written diagnostic and management plan accuracy. Our study, with its small sample size, did not yield statistically significant results regarding our main hypotheses that physicians’ implicit bias would be associated with lower quality CR, inclusive of diagnostic and treatment outcomes when seeing Black SPs as compared to White SPs. However, we had some suggested findings that should guide future work on implicit bias and its impact on health disparities. First, our study included a potentially more (ACS diagnostic dilemma) and potentially less (rib fracture requiring pain management) cognitively demanding case. As previously seen in the literature, implicit bias did not appear to influence CR accuracy in the potentially less cognitively demanding case bias [38], [39], [40], [41]. For the potentially more cognitively demanding case, outcomes for the Race and RMC- IAT were distinct from each other. The Race IAT, which measures affective bias (prejudice) using timed associations between images of Black and White faces with valanced words such as joy and evil, had minimal to no correlation with CR. Our data suggested a possible moderate correlation between the RMC-IAT, which measures cognitive bias (stereotyping of Black patients as less medically cooperative than White patients), and physician CR accuracy scores when seeing Black SPs which was not evident when physicians were seeing White SPs. Suggesting that stereotyping (a cognitive implicit bias) rather than prejudice (an affective implicit bias) may be a factor in disparities in CR. If this finding can be confirmed it may have implications for developing interventions with a comprehensive approach to achieving equitable outcomes.

Our study highlights the importance of integrating cognitive stressors common to clinical environments into simulation-based research and the importance of adequate sample size to study the impact of cognitive implicit bias on CR. Similar to our study, Oliver and colleagues did find an association between RMC-IAT scores and the decision to refer a hypothetical patient for knee replacement by race, but Race IAT scores were not associated with this clinical recommendation [28]. CR is highly complex [1]; it is possible that physicians may develop cognitive biases which negatively influence their CR over the course of medical training. This is supported by findings in a study observing changes in medical students’ performance in simulated encounters from the first to second year of medical school [49]. In the first year, medical students performed equally well with Black and White SPs in all domains of history-taking and communication skills. In the second year, however, medical students performed equally well with all SPs in history gathering, but worse in every other domain tested with Black compared with White SPs [49]. These findings demonstrate a need to continue to investigate the impact of the curriculum and learning environment throughout medical education and training on learners’ and physicians’ stereotyping of patients and development of cognitive implicit bias that negatively impact their CR. Finally, our findings support evidence on the different impact between affective and cognitive implicit bias (i.e. prejudice and stereotyping) and add to the literature on CR and context specificity and cognitive load [1], [2], [3, 6], 50], 51].

Our study is the first to specifically investigate simulated encounters with SP race and physician racial implicit bias as contextual factors that may affect CR; our findings provide guidance for next steps in this important area of research. We have previously outlined the implications for simulation-based education and research in addressing the impact of implicit bias on clinical encounters. Our current findings expand on our prior recommendations by highlighting the importance of studying both affective and cognitive implicit bias (e.g. through Race- and RMC-IATs, respectively). CR is known to be impacted by multiple cognitive biases (e.g., anchoring, recall, and confirmation biases, among others) when caring for patients. Stereotyping may be an additional cognitive bias that further detracts from effective CR when seeing patients that hold minoritized identities – in our case Black SPs [3].

Limitations

While we were powered to find anticipated communication disparities, we were underpowered to draw definitive conclusions on the impact of racial implicit bias on CR. While using SP based simulation allowed us to create authentic clinical contexts it is resource intense and therefore did limit the sample size and specific clinical situations we could study. Future studies should explore the relationship between implicit biases and clinical reasoning in a range of clinical scenarios, contexts and cognitive stressors. The expression of physician implicit bias may have been limited by two factors: 1) choosing early career physicians may have resulted in physicians with more exposure to instruction on implicit bias compared to the general physician population; and 2) the inclusion of a challenging clinical presentation in level-setting scenario (scenario 1) may have actually induced more deliberate, Type 2 thinking thereby potentially skewing our results to the null.

Despite these limitations, our study advances the literature in characterizing the impact of implicit bias and informs efforts to develop interventions to address this negative impact. Larger studies seeking to address the impact of implicit bias could consider using both affective IATs to measure prejudice and cognitive IATs to measure stereotyping by clinicians, and the impact of those respective biases on CR outcomes with SPs and actual patients. Among our next steps are an in-depth qualitative video analysis to identify verbal and nonverbal physician behaviors that contribute to CR accuracy.

Conclusions

Racial implicit bias may impact clinical reasoning; this impact, however, is nuanced and contextual. This study suggested a potential impact of cognitive implicit bias (i.e. stereotyping) on CR accuracy when physicians are seeing Black SPs, but not when seeing White SPs – a finding that might inform future study design and power calculations in research aiming to understand the complex phenomenon of CR. Our findings support the need for a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to future simulation-based research seeking to address the impact of racial implicit bias on clinical encounters, with the ultimate goal of contributing to health equity.

Funding source: Department of Defense, the NIH and VA HSR&D

Award Identifier / Grant number: NH170001, R61AT012309, 1R61NS130636, SDR 21-012, I

Funding source: National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities

Award Identifier / Grant number: K23MD014178

Funding source: National Academy of Medicine's Scholars in Diagnostic Excellence

Acknowledgments

Felise Milan, MD for initial development of CR scoring rubric.

-

Research ethics: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the NYU Grossman School of Medicine IRB #23–00037, approved 2020 and 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: Dr. Gonzalez and this project is funded by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities K23MD014178. Dr. Burgess receives funding through the Department of Defense, the NIH and VA HSR&D through grants NH170001, R61AT012309, 1R61NS130636, SDR 21-012, IIR 20–115.

-

Data availability: Inquiries can be sent to the corresponding author and will be considered on a case by case basis.

References

1. Holmboe, ES, Durning, SJ. Assessing clinical reasoning: moving from in vitro to in vivo. Diagnosis (Berl) 2014;1:111–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Merkebu, J, Battistone, M, McMains, K, McOwen, K, Witkop, C, Konopasky, A, et al.. Situativity: a family of social cognitive theories for understanding clinical reasoning and diagnostic error. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7:169–76. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Connor, DM, Lypson, ML, Gonzalez, CM. Advancing diagnostic excellence with medical education in diagnostic equity. N Engl J Med 2025:In Press. 393:1202–14. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2411882.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Care COUaERaEDiH. Unequal treatment: what healthcare providers need to know about racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Inst Med, National Acad Sci 2002:1–7.Search in Google Scholar

5. Association of American Medical Colleges. Addressing Racial Disparities in Health Care: A Targeted Action Plan for Academic Medical Centers. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

6. Feagin, J, Bennefield, Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Udoetuk, S, Dongarwar, D, Salihu, HM. Racial and gender disparities in diagnosis of malingering in clinical settings. J Racial Ethn Health Dispar 2020;7:1117–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00734-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Eack, SM, Bahorik, AL, Newhill, CE, Neighbors, HW, Davis, LE. Interviewer-perceived honesty as a mediator of racial disparities in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:875–80. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100388.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Olbert, CM, Nagendra, A, Buck, B. Meta-analysis of black vs. white racial disparity in schizophrenia diagnosis in the United States: do structured assessments attenuate racial disparities? J Abnorm Psychol 2018;127:104–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000309.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Newman-Toker, DE, Moy, E, Valente, E, Coffey, R, Hines, AL. Missed diagnosis of stroke in the emergency department: a cross-sectional analysis of a large population-based sample. Diagnosis (Berl) 2014;1:155–66. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Goyal, MK, Chamberlain, JM, Webb, M, Grundmeier, RW, Johnson, TJ, Lorch, SA, et al.. Racial and ethnic disparities in the delayed diagnosis of appendicitis among children. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28:949–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Tsoy, E, Kiekhofer, RE, Guterman, EL, Tee, BL, Windon, CC, Dorsman, KA, et al.. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in timeliness and comprehensiveness of dementia diagnosis in California. JAMA Neurol 2021;78:657–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. DeVon, HA, Burke, LA, Nelson, H, Zerwic, JJ, Riley, B. Disparities in patients presenting to the emergency department with potential acute coronary syndrome: it matters if you are black or white. Heart Lung 2014;43:270–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.04.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Shafiq, A, Gosch, K, Amin, AP, Ting, HH, Spertus, JA, Salisbury, AC. Predictors and variability of drug-eluting vs bare-metal stent selection in contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the PRISM study. Clin Cardiol 2017;40:521–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22693.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Karnati, SA, Wee, A, Shirke, MM, Harky, A. Racial disparities and cardiovascular disease: one size fits all approach? J Card Surg 2020;35:3530–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocs.15047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Thompson, T, Stathi, S, Buckley, F, Shin, JI, Liang, CS. Trends in racial inequalities in the administration of opioid and non-opioid pain medication in US emergency departments across 1999–2020. J Gen Intern Med 2024;39:214–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08401-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Benzing, AC, Bell, C, Derazin, M, Mack, R, MacIntosh, T. Disparities in opioid pain management for long bone fractures. J Racial Ethn Health Dispar 2020;7:740–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00701-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Kang, H, Zhang, P, Lee, S, Shen, S, Dunham, E. Racial disparities in opioid administration and prescribing in the emergency department for pain. Am J Emerg Med 2022;55:167–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.02.043.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Anderson, KO, Green, CR, Payne, R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 2009;10:1187–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Green, AR, Carney, DR, Pallin, DJ, Ngo, LH, Raymond, KL, Iezzoni, LI, et al.. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1231–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Sabin, JA, Rivara, FP, Greenwald, AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care 2008;46:678–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181653d58.Search in Google Scholar

22. Sabin, JA, Greenwald, AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Publ Health 2012;102:988–95. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2011.300621.Search in Google Scholar

23. Daugherty, SL, Blair, IV, Havranek, EP, Furniss, A, Dickinson, LM, Karimkhani, E, et al.. Implicit gender bias and the use of cardiovascular tests among cardiologists. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.006872.Search in Google Scholar

24. Colon-Emeric, CS, Corazzini, K, McConnell, E, Pan, W, Toles, M, Hall, R, et al.. Study of individualization and bias in nursing home fall prevention practices. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:815–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14675.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Stepanikova, I. Racial-ethnic biases, time pressure, and medical decisions. J Health Soc Behav 2012;53:329–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512445807.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hausmann, LR, Myaskovsky, L, Niyonkuru, C, Oyster, ML, Switzer, GE, Burkitt, KH, et al.. Examining implicit bias of physicians who care for individuals with spinal cord injury: a pilot study and future directions. J Spinal Cord Med 2015;38:102–10. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772313y.0000000184.Search in Google Scholar

27. Kalbaugh, CA, Beidelman, ET, Howard, KA, Witrick, B, Clark, A, McGinigle, KL, et al.. Implicit racial bias and unintentional harm in vascular care. JAMA Surg 2025. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2024.7254.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Oliver, MN, Wells, KM, Joy-Gaba, JA, Hawkins, CB, Nosek, BA. Do physicians’ implicit views of African Americans affect clinical decision making? J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27:177–88. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.120314.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Haider, AH, Schneider, EB, Sriram, N, Dossick, DS, Scott, VK, Swoboda, SM, et al.. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;77:409–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000000392.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Hirsh, AT, Hollingshead, NA, Ashburn-Nardo, L, Kroenke, K. The interaction of patient race, provider bias, and clinical ambiguity on pain management decisions. J Pain 2015;16:558–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Haider, AH, Schneider, EB, Sriram, N, Dossick, DS, Scott, VK, Swoboda, SM, et al.. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg 2015;150:457–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Puumala, SE, Burgess, KM, Kharbanda, AB, Zook, HG, Castille, DM, Pickner, WJ, et al.. The role of bias by emergency department providers in care for American Indian children. Med Care 2016;54:562–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000533.Search in Google Scholar

33. Blair, IV, Steiner, JF, Hanratty, R, Price, DW, Fairclough, DL, Daugherty, SL, et al.. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:987–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2795-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Cooper, LA, Roter, DL, Carson, KA, Beach, MC, Sabin, JA, Greenwald, AG, et al.. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Publ Health 2012;102:979–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2011.300558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Penner, LA, Dovidio, JF, Gonzalez, R, Albrecht, TL, Chapman, R, Foster, T, et al.. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2874–80. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.66.3658.Search in Google Scholar

36. Blair, IV, Steiner, JF, Fairclough, DL, Hanratty, R, Price, DW, Hirsh, HK, et al.. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1442.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Hagiwara, N, Slatcher, RB, Eggly, S, Penner, LA. Physician racial bias and word use during racially discordant medical interactions. Health Commun 2017;32:401–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1138389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Burgess, DJ. Are providers more likely to contribute to healthcare disparities under high levels of cognitive load? How features of the healthcare setting may lead to biases in medical decision making. Med Decis Mak 2010;30:246–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x09341751.Search in Google Scholar

39. van Ryn, M, Saha, S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA 2011;306:995–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Blair, IV, Steiner, JF, Havranek, EP. Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: where do we go from here? Perm J 2011;15:71–8. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/11.979.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Johnson, TJ, Hickey, RW, Switzer, GE, Miller, E, Winger, DG, Nguyen, M, et al.. The impact of cognitive stressors in the emergency department on physician implicit racial bias. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:297–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Dehon, E, Weiss, N, Jones, J, Faulconer, W, Hinton, E, Sterling, S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:895–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13214.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Whelton, PK, Carey, RM, Aronow, WS, Casey, DEJr., Collins, KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb, C, et al.. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American college of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12:579 e1–e73.10.1016/j.jash.2018.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Gonzalez, CM, Ark, TK, Fisher, MR, Marantz, PR, Burgess, DJ, Milan, F, et al.. Racial implicit bias and communication among physicians in a simulated environment. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e242181. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Ark, TKFM, Kalet, A, Milan, F, Marantz, PR, Burgess, D, Starrels, JL, et al.. My neighbor said Percocet might help. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37:199.Search in Google Scholar

46. Fiscella, K, Epstein, RM, Griggs, JJ, Marshall, MM, Shields, CG. Is physician implicit bias associated with differences in care by patient race for metastatic cancer-related pain? PLoS One 2021;16:e0257794. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257794.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Hoffman, KM, Trawalter, S, Axt, JR, Oliver, MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:4296–301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Project Implicit. Implicit Association Test 2011. Available from: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/.Search in Google Scholar

49. Rubineau, B, Kang, Y. Bias in white: a longitudinal natural experiment measuring changes in discrimination. Manag Sci 2012;58:660–77. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1439.Search in Google Scholar

50. Balakrishnan, K, Arjmand, EM. The impact of cognitive and implicit bias on patient safety and quality. Otolaryngol Clin 2019;52:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2018.08.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Payne, BK, Vuletich, HA, Brown-Iannuzzi, JL. Historical roots of implicit bias in slavery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:11693–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818816116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2026 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.