Abstract

This exploratory interdisciplinary study investigates how fan translations on digital platforms reshape the portrayal of literary characters, using Jin Yong’s A Hero Born: The Legend of the Condor Heroes (射雕英雄传) as a case study. Grounded in a framework combining Lefevere’s rewriting theory, Jenkins’ convergence culture, and the Five-Factor Model of personality, the research treats fan translation as a collective cultural rewriting that unfolds through participatory digital discourse. The study integrates a computational analysis of characters’ Big Five personality traits with a qualitative analysis of online fan discussions. This mixed-methods approach reveals how a digital community’s cultural and ideological stances shape its translation choices and character interpretations. The findings suggest that fan translations are culturally mediated transformations driven by community engagement. These translations exhibit observable changes in character personality traits that correspond to the fan community’s values and interpretations. By extending Lefevere’s framework into the realm of participatory culture, this study develops a new methodology for analyzing how characters are received and reconstructed across different translations. The research contributes to both translation studies and digital humanities by demonstrating how online communities collectively negotiate and reinterpret literary characters within their specific cultural contexts, thus offering valuable insights into translation as a collaborative cultural practice in the digital age.

1 Introduction

The digital era has transformed translation practices, with online platforms and communities playing a key role in shaping how literary works are interpreted and received (Cronin 2010; Littau 2016). The rise of fan translations, driven by technological advancements and increased access to translation tools, has enabled amateur translators to actively engage in shaping texts and their meanings (Jiménez-Crespo 2017). Unlike professional translation, fan translation is collective and community-driven. Audiences act as both consumers and producers of translated works. (Cronin 2010). This shift raises important questions about how fan translations influence readers’ perceptions of literary characters and how online communities contribute to these interpretations.

One critical challenge in literary translation is the portrayal of characters through language. Characterization involves the attribution of traits, qualities, and identities to figures in a story (Jannidis 2009). Dialogue, in particular, is central to this process, as it provides insight into a character’s emotions, intentions, and personality (Mahlberg 2013). Translating dialogue requires careful attention, as it directly shapes how characters are understood in the target language. While professional translators have been studied extensively in this regard (Bosseaux 2013; McIntyre and Lugea 2015), the work of fan translators, who often operate within participatory online communities, remains less explored. Fan translators not only translate texts but also engage with their communities to discuss, interpret, and collaboratively refine their translations, further shaping how characters are represented and understood.

This study acknowledges that applying computational personality models trained on contemporary conversational data to semi-classical literary texts presents methodological challenges. As exploratory interdisciplinary research, it aims to establish a preliminary framework for character-focused translation analysis rather than providing definitive claims about personality trait accuracy. The primary contribution lies in demonstrating the potential for integrating computational methods with traditional translation studies approaches, laying groundwork for future research with more extensive validation.

While prior research on Wuxia translations (Diao 2023; Wu and Li 2021, 2022) has provided valuable linguistic insights, these studies have primarily focused on translation strategies and linguistic variation rather than the transformation of character portrayal. This gap is particularly relevant in the context of fan translations, where character interpretation is shaped by community engagement and participatory practices. Diao’s (2023) survey of English translations of Jin Yong’s works highlights the importance of individual translator styles in shaping character perception, while corpus-based studies (Wu and Li 2021) offer quantitative evidence of linguistic variation across translations. These studies provide a useful foundation but do not fully explore the qualitative dimension of character portrayal.

Jin Yong’s The Legend of the Condor Heroes (射雕英雄传) provides a valuable case study for examining how fan translations influence character portrayal. The novel has been widely translated and discussed by fan communities since 2007. These translations, shared and debated across forums and social media platforms, depict how fan translators and readers collectively interpret character traits and narrative elements. Huang Rong, one of the novel’s central characters, has been a particularly prominent focus of fan translations and discussions. Her dialogue plays an important role in shaping her personality and has inspired various interpretations within fan communities. Examining how her character is translated and received offers insights into the relationship between fan translation practices and reader engagement.

This study analyzes how fan translations reshape character portrayal in The Legend of the Condor Heroes, focusing on one of protagonists Huang Rong’s personality as reflected in her dialogue. It uses a mixed-method approach that integrates computational and qualitative analysis. Computationally, the study applies the Big Five personality traits model (McCrae and John 1992; Goldberg 1993) to analyze dialogue patterns in fan translations and the original text. This model, widely used in psychology, provides a framework for identifying personality traits based on linguistic features. Qualitatively, the study examines discussions from fan forums and online platforms to understand how readers interpret and respond to translations. By combining these methods, the research aims to explore how translation practices influence character portrayal and how fan communities engage with these interpretations.

The findings of this study contribute to ongoing discussions in translation studies by highlighting the role of fan translators and digital communities in shaping literary reception. Fan translations demonstrate how amateur translators make creative and interpretive decisions that influence how characters are understood across languages. These decisions are not made in isolation but are shaped by the cultural, ideological, and social dynamics of the communities in which fan translations circulate.

To explore these dynamics, this study adopts André Lefevere’s concept of rewriting (1992/2016) as a theoretical framework to analyze how fan translators reinterpret and reshape texts in participatory online communities. Rewriting, as defined by Lefevere, refers to the transformation of texts under the influence of cultural, ideological, and social forces. In the context of fan translation, rewriting takes on a participatory dimension, as fan translators collaborate with their communities to adapt texts to meet the expectations and preferences of their target audience. This framework provides a lens to examine how fan translators portray characters such as Huang Rong in The Legend of the Condor Heroes and how these portrayals reflect the cultural and narrative priorities of fan communities.

Using rewriting as a theoretical lens, this study explores how fan translators adapt dialogue and narrative elements to reflect the values and expectations of their communities. By focusing on the portrayal of Huang Rong, a central figure in The Legend of the Condor Heroes, this research examines how fan translations reshape characterization and contribute to the participatory process of meaning-making. This leads to three key research questions.

This study addresses three key questions:

How do fan translators represent character traits, particularly through the translation of dialogue?

How do online communities interpret and discuss these character portrayals?

How does the collective participation of fan communities contribute to the understanding of characters in translated works?

By focusing on these questions, the research provides insights into the practices of fan translators and the ways in which digital communities engage with translated texts. It highlights the collaborative nature of fan translation and its impact on cross-cultural literary communication in the digital age.

The following sections open with a review of the key concepts of rewriting and fan translation, emphasizing their collaborative and transformative aspects. It then explores character reconstruction in translation studies, with an emphasis on Wuxia literature, before introducing interdisciplinary methodologies for analyzing character representation. The conclusion reflects on the implications of these findings and proposes directions for future research.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Rewriting and Fan Translation

Fan studies have significantly expanded in recent decades, highlighting the role of fan-created content in shaping contemporary media. Fan fiction and fan translation, as key areas of engagement, illustrate how fans actively reinterpret original texts. Early studies on fan fiction established a framework for understanding such reinterpretations (Bacon-Smith 1992; Pugh 2005). These works provided insight into how fan communities engage with existing narratives, modifying and expanding them to reflect alternative character developments and storylines.

The concept of rewriting, as introduced by Lefevere (1992/2016), provides a theoretical foundation for understanding fan translation. Lefevere frames translation as an act of rewriting that is influenced by ideological, cultural, and institutional forces, demonstrating how translations serve as a form of textual manipulation (Hermans 1999/2019). In parallel, Jenkins’ (1992) concept of textual poaching highlights the participatory nature of fan engagement, wherein fans appropriate and rework texts to align with their own interpretive frameworks. These perspectives converge in fan translation, where amateur translators simultaneously function as interpreters and active participants in cultural adaptation.

Building on these foundational theories, scholars have examined fan translation as a participatory practice (O’Hagan 2009) and a form of cultural mediation (Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva 2012). Research on fansubbing (Díaz Cintas and Muñoz Sánchez 2006) highlights its collaborative nature, while studies on Chinese fan translators (Li 2021) emphasize diverse motivations such as content sharing and skill development. Dwyer (2012) and Massidda (2020) note the creative aspects of fan translation, highlighting how translators often adapt content to better align with their cultural expectations and audience preferences. While fan translation research has extensively explored collaboration and cultural impact, it has not fully addressed the character portrayal. Fan fiction studies have analyzed character reinterpretation (Thomas 2011; Van Steenhuyse 2011), but fan translation research has largely focused on broader processes rather than how characters are subtly reshaped during translation. This gap presents an opportunity to explore how fan translators adapt character personalities, reflecting linguistic and cultural priorities.

2.2 Character Portrayal in Translation Studies

This section focuses specifically on character portrayal in translation studies. While previous research has explored how texts are reshaped across linguistic and cultural contexts, the representation of characters – particularly in genres like Wuxia literature – remains underexplored. Translators, whether professional or amateur, do not merely convey words; they reinterpret and reconstruct characters, imbuing them with cultural and ideological concerns for new audiences. This study addresses a key gap by extending the discussion of fan translation into the field of Wuxia character portrayal.

Foundational works by Bosseaux (2007) established the importance of linguistic choices in shaping character perception in translated texts. These studies provide valuable insights into Western literature translation but do not address the unique challenges posed by translating Chinese Wuxia novels, where characters often reflect deep cultural and philosophical underpinnings. Theoretical frameworks by Boase-Beier (2014) emphasize the interplay between translator interpretation and creative decision-making, highlighting how translators’ subjective understanding influences the final portrayal of characters. However, these frameworks have yet to be applied to Wuxia literature, leaving a gap that this study aims to address by examining how these principles manifest in the translation of martial arts heroes and other key characters.

Our study addresses this critical research gap by focusing on the portrayal of characters in fan translations of Wuxia novels. Specifically, we will analyze the strategies and methods fan translators use to render character portrayals, comparing their translations with the original texts. Key elements such as dialogue, internal monologue, and behavioral descriptions will be examined to understand how translation choices affect character representation. Additionally, we will investigate how fan translators’ creative decisions impact the reception and interpretation of these characters in the target culture.

2.3 The Big Five Personality Traits Model and Computational Methods in Literary and Translation Studies

Traditionally, character portrayal in translation studies has been analyzed qualitatively, but recent interdisciplinary approaches have integrated computational methods and psychological models such as the Five-Factor Model to examine character transformation. The application of computational techniques has evolved from author profiling (Argamon et al. 2005) to literary analysis, where personality traits are inferred through textual features. Early computational literary studies focused on character relationships (Srivastava et al. 2016; Chaturvedi et al. 2016), but later work incorporated psychological frameworks (Flekova and Gurevych 2015; Bamman et al. 2013, 2014), linking textual features with established personality models.

Flekova and Gurevych (2015) were among the first to apply psychological theories to computational literary analysis, demonstrating how character personality can be inferred from textual data. Bamman et al. (2014) introduced Bayesian mixed-effects modeling to analyze character archetypes in fiction, providing a framework that integrates linguistic and narrative structures. These studies illustrate how computational methods can deepen our understanding of character representation beyond traditional literary analysis.

While computational methods have proven effective for Western literature, their application to Chinese Wuxia texts presents challenges. Personality constructs may manifest differently across cultures due to variations in linguistic norms, narrative structures, and social values. Traits like “agreeableness” or “openness” may be expressed differently in Wuxia literature, where characters embody Confucian, Daoist, or martial ideals. Fan translators, who are often highly familiar with the source text’s cultural nuances, may prioritize cultural fidelity over direct linguistic equivalence, further influencing character portrayal.

Recent research has adopted computational methods for cross-cultural contexts (Van de Vijver and Leung 2021). Quantitative tools combined with qualitative analysis have been employed to assess how personality traits manifest in dialogue, internal monologue, and behavioral descriptions (Xu 2022; Polzehl 2015). These approaches demonstrate significant variations in character portrayal, illustrating how linguistic, cultural, and psychological factors interact in translation. Wuxia literature, where character personalities are closely tied to cultural values, provides a particularly rich site for this methodology, allowing researchers to analyze how traits such as “loyalty” and “justice” are conveyed or reinterpreted in translation.

By applying these interdisciplinary methods to translation studies, particularly in the context of fan translations, researchers can uncover how characters are reshaped across linguistic and cultural boundaries. This study builds on existing research by applying these methods to the understudied area of Wuxia fan translations, offering new insights into how literary characters are reinterpreted and transmitted across cultures. Ultimately, this approach contributes to a deeper understanding of character portrayal in cross-cultural literary transmission and highlights the potential of computational methods to bridge the gap between literary analysis and translation studies.

3 Methodology: Computational Analysis and Community Interpretation

Building on the theoretical foundations of rewriting and fan translation, this study adopts an integrated methodological framework to explore character portrayal across translations. By combining computational personality analysis with qualitative observation of digital communities, the methodology enables both quantitative identification of translation-induced changes and qualitative insights into how readers interpret these shifts.

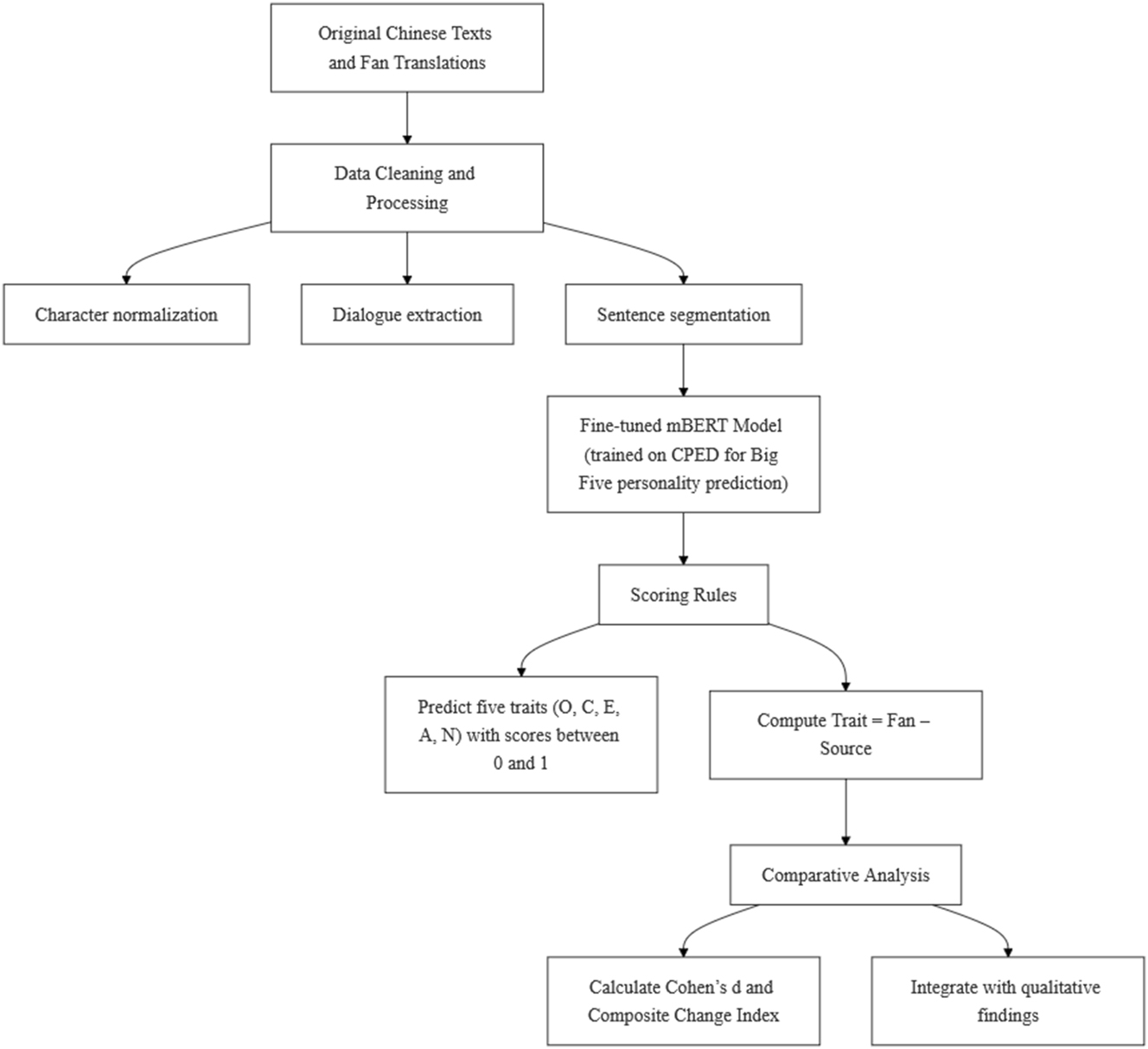

This study employed Multilingual BERT (mBERT; Devlin et al. 2019), fine-tuned on the CPED dataset (Chinese Personalized and Emotional Dialogue; Chen et al. 2022), to predict Big Five personality traits in both Chinese and English (see the experiment workflow in Figure 1). Pre-trained on over 100 languages, mBERT provided a unified framework for cross-linguistic personality prediction by projecting different languages into a shared semantic space. Fine-tuning on CPED, a large-scale corpus of modern Chinese dialogues annotated with personality and emotional traits, allowed the model to better capture culturally embedded expressions of personality in Chinese texts.

Experiment workflow.

To adapt mBERT for trait prediction, CPED Big Five labels were treated as binary (high or low), with unknown cases masked. Soft labels of 0.8 and 0.2 were applied to reduce polarity and allow smoother learning. The model was fine-tuned for up to five epochs with early stopping, using a learning rate of 2 × 10−5 and a batch size of 16. To avoid data leakage, the dataset was split 80/10/10 into training, validation, and test subsets without speaker overlap. During inference, the model produced a probability for the high class, interpreted as a continuous trait score for each utterance and averaged across all utterances attributed to the same character.

While CPED is based on contemporary spoken dialogue (e.g., TV scripts), its dialogic structure and personality labels make it a useful proxy for modeling personality in literary texts, where character traits are likewise conveyed through speech patterns, lexical choices, and interpersonal dynamics. We recognized that stylistic and temporal differences existed between modern conversation and historical fiction, particularly in terms of register and rhetorical devices. To mitigate the effects of such domain mismatch, our analysis did not emphasize absolute trait scores but instead compared relative differences across translation versions for the same character. By focusing on relative changes, the approach minimizes cultural and stylistic variability and highlights meaningful shifts in character portrayal.

To further assess the plausibility of the model’s predictions, we conducted a qualitative comparison with widely circulated character interpretations. In the absence of a unified scholarly framework for psychological profiling in Wuxia fiction, we treated the Wuxia Fandom encyclopedia (https://wuxia.fandom.com) as a proxy for aggregated reader-informed consensus. Although community-generated, this source consolidates long-standing interpretive traditions and provides a coherent account of how characters such as Guo Jing and Huang Rong are generally perceived. Descriptive terms drawn from fandom entries (e.g., “loyal,” “dutiful,” “compassionate”) were then mapped to approximate Big Five categories with reference to the 435 personality adjectives compiled by Saucier and Goldberg (1996). This heuristic but structured mapping offered a way to evaluate whether model predictions were broadly compatible with recognizable character traits.

Take, for example, the case of Guo Jing. The Wuxia Fandom entry characterizes Guo Jing as:

Frequently described as dumb, slow, and inarticulate, Guo Jing is the complete opposite of his clever and witty wife, Huang Rong. His most distinguishing characteristic, apart from mental slowness, is his constant fight for moral rectitude. … He embodies loyalty, compassion, magnanimity, generosity and an overriding desire to protect the people. … He is widely considered to be the platonic ideal of the Confucian Xia.

We compared these descriptions with the model’s predictions for Guo Jing (based on the fan-translated version), mapping descriptive terms to the Big Five using the personality adjective framework of Saucier and Goldberg (1996) (see Table 1).

Comparison of Guo Jing’s Big Five Traits between fandom.com description and fan translation.

| Trait | Fandom description | Mapped adjectives (Saucier & Goldberg) | Model score | Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | Reserved and inarticulate, but later becomes proactive | reserved, quiet, unexpressive → moderately outgoing | 0.651 | Partially aligned |

| Neuroticism | Emotionally steady, dignified | calm, stable, unemotional | 0.250 | Aligned |

| Agreeableness | Loyal, compassionate, generous | loyal, kind, forgiving, cooperative | 0.902 | Aligned |

| Conscientiousness | Principled, dutiful, rigid moral code | dutiful, disciplined, rule-bound | 0.951 | Aligned |

| Openness | Morally traditional, limited imagination, but capable of growth | conventional, traditional, practical | 0.701 | Partially aligned |

The high scores for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness correspond closely to Guo Jing’s portrayal as loyal, dutiful, and morally upright, while the low Neuroticism score reflects his composure and emotional steadiness. Extraversion and Openness show only partial alignment, capturing his eventual emergence as a proactive leader while overstating his imaginative scope.

This exercise suggests that the model’s predictions are broadly consistent with recognizable and widely discussed features of major characters, providing a plausible bridge between computational outputs and established literary interpretations. At the same time, the comparison remains qualitative and interpretive rather than definitive. We see it as a first step toward integrating computational personality modeling into literary translation studies. Future refinements could include expert annotation of character arcs, triangulation with reader-generated data (e.g., reviews on Goodreads or Douban), and intersubjective reliability checks by involving multiple annotators. This validation step also provides a basis for the subsequent analysis, where we apply the model to a curated set of characters across Chinese source texts and their English translations.

The study examines 40 chapters of the second edition of She Diao Ying Xiong Zhuan (射雕英雄传, 修订版/三联版) and its English fan translation (Condor Trilogy – Eagle Shooting Hero), a collaborative work by translators including Minglei Huang, Foreva, and Strunf. These texts were selected for their completeness, narrative importance, and availability in digital formats. To ensure robust analysis, characters were chosen based on their narrative significance and role diversity, including both protagonists (Guo Jing and Huang Rong) and secondary characters (Ke Zhen E, Han Xiao Ying, Han Bao Ju, Zhu Cong, and Qiu Chu Ji). Each selected character had at least 50 dialogue instances, ensuring sufficient data points for meaningful computational analysis.

Dialogue extraction was performed using a hybrid computational approach that combined Voyant Tools with custom Python scripts optimized for bilingual processing. Direct speech is critical for personality prediction because it reflects a character’s voice, tone, and linguistic choices, which are key indicators of personality traits. In the Chinese text, markers such as “道” (said), “说” (spoke), and “问” (asked) were used to identify utterances, while in the English translation, punctuation patterns (e.g., quotation marks) and speaker tags served as indicators. This process ensured accurate identification of character utterances, with Table 2 summarizing the direct speech counts for the selected characters across the source and translated texts.

Direct speech extraction from original Chinese and fan translation.

| Character | Direct speech numbers in source text | Direct speech numbers in fan translation |

|---|---|---|

| Guo Jing | 1,152 | 1,109 |

| Huang Rong | 1,081 | 1,030 |

| Qiu Chu Ji | 175 | 110 |

| Ke Zhen E | 127 | 136 |

| Zhu Cong | 80 | 85 |

| Han Xiao Ying | 66 | 52 |

| Han Bao Ju | 51 | 55 |

After extracting character dialogues, we performed a series of preprocessing steps to prepare the texts for analysis. This included punctuation normalization, resolution of ambiguous pronoun references in semi-classical Chinese, word segmentation using Jieba (v.0.42.1), and speaker tagging to ensure accurate attribution of each utterance. We then applied the previously fine-tuned mBERT model to predict Big Five personality traits for each utterance. Given the linguistic and stylistic gap between modern dialogue (CPED) and literary fiction, we focused on relative trait differences across translation versions rather than absolute values. This strategy allowed us to highlight shifts in character portrayal while accounting for potential cultural and domain mismatches.

After extracting the Big Five personality trait scores for each character from both the original text and the fan translations using our pre-trained model, we employed Cohen’s d to quantify differences in character portrayals. Cohen’s d provides a standardized effect size that is well-suited for translation studies due to its comparability across traits and characters, as well as its established interpretive benchmarks (Cohen 1988, 1992; Lakens 2013). We calculated Cohen’s d as

where a positive value indicates that the trait is stronger in the English fan translation, and a negative value indicates that it is stronger in the original Chinese text. Following Cohen’s (1992) guidelines, values of approximately 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were interpreted as small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

To capture overall shifts in character portrayal, we also computed a composite effect size by averaging the absolute d values across the five traits:

This composite score provides a holistic measure of how much a character’s personality shifts in fan translation, regardless of the direction of change (Gignac and Szodorai 2016).

By focusing on relative changes rather than absolute scores, our approach avoids pitfalls of direct cross-linguistic comparison while retaining analytical utility. For example, a decrease in openness may reflect simplified dialogue or the omission of culturally specific markers of intellectual curiosity, while an increase in conscientiousness might signal an emphasis on responsibility added by translators. Such patterns illustrate the interpretive decisions shaping fan translations. Using the same computational model across source and translated texts ensures consistency, so that observed differences genuinely reflect translation-induced variation rather than methodological artifacts (Jannidis et al. 2016; Boyd and Pennebaker 2017).

3.1 Online Community Analysis

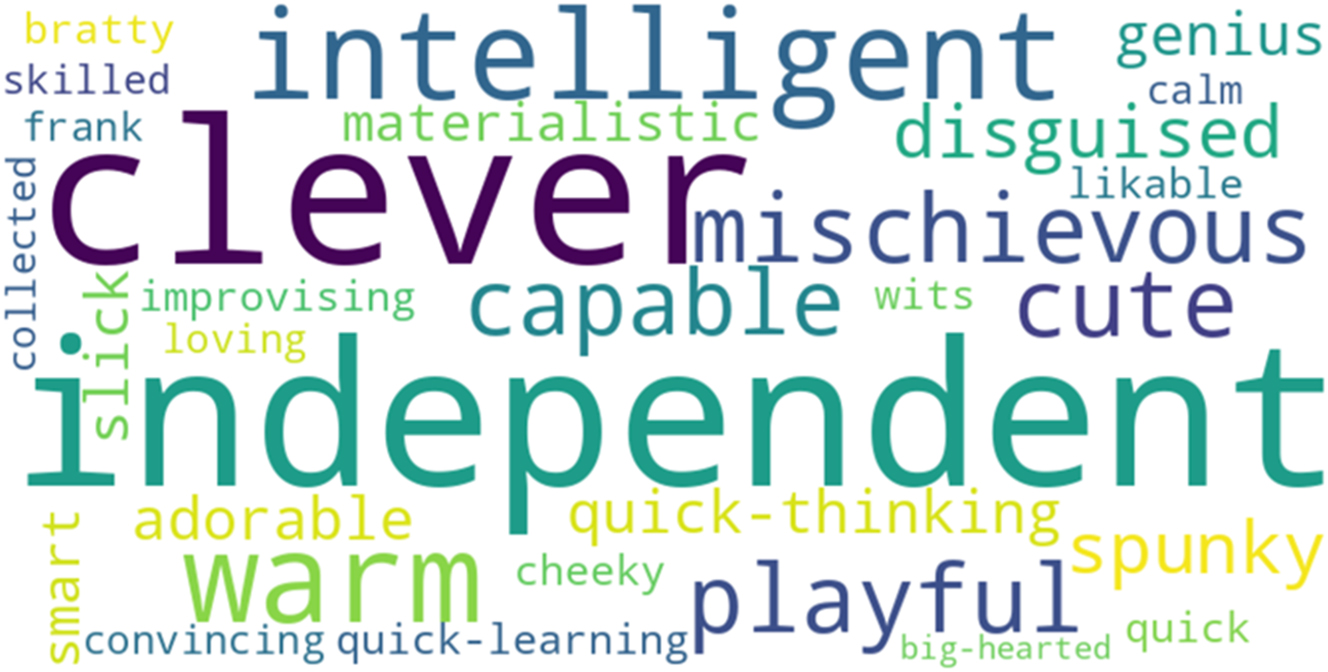

To supplement the quantitative analysis, this study explores how digital communities describe and interpret character portrayals in The Legend of the Condor Heroes (LOCH). By focusing on fan discussions, this section aims to investigate whether the opinions and perceptions expressed in online posts align with the trends observed in the quantitative data. Huang Rong, one of the central figures in LOCH, was selected as the focal point for this analysis due to her complex characterization and prominent role in the narrative.

A WordCloud was used to visualize frequently mentioned descriptors of Huang Rong from online discussions. Spcnet.com was chosen as the sole data source, as it is one of the most active and influential forums for Wuxia enthusiasts, providing a rich participatory space where fans engage in detailed debates about translation choices and character traits. The data collection process focused on forum posts specifically discussing Huang Rong in the context of LOCH. Search parameters such as “Huang Rong,” “HR,” and “LOCH” were used to locate relevant discussions. To capture the immediate reception of the fan translation, posts from 2005 to 2007 were prioritized, minimizing the potential influence of later reinterpretations or adaptations of her character.

The collected text was first cleaned to remove unrelated elements like usernames, timestamps, and other unnecessary content. Using TF-IDF analysis (v.1.3.0), we extracted adjectives and descriptive phrases about Huang Rong from the cleaned text. Common descriptors were then displayed in a word cloud using Python’s WordCloud library (v.1.9.2), where the size of each word shows how often it appears in the text. By centering this analysis on Huang Rong and comparing her portrayal in fan discussions with the quantitative findings, this approach provides an additional layer of insight into how translations shape audience perceptions of character traits. The word cloud offers a macroscopic view of how fans collectively describe Huang Rong, complementing the systematic data with qualitative insights drawn from community discourse.

4 Findings and Results

This section presents the key findings, focusing on the relative changes in personality trait scores between the original text and fan translations. By analyzing shifts in the Big Five personality traits, the study highlights how fan translations reshape character portrayals in The Legend of the Condor Heroes. Instead of interpreting absolute trait values, the analysis prioritizes differences between versions to uncover how fan translators adapt characters to reflect modern cultural and narrative preferences.

4.1 Computational Analysis Results

This section presents the results derived from the computational model, which calculates the selected characters across original and versions of the text (see Table 3).

Character personality traits in original and fan translation.

| Character | Version | Extraversion | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo Jing | Original | 0.50213 | 0.34987 | 0.75102 | 0.80034 | 0.59876 |

| Fan | 0.65128 | 0.24953 | 0.90215 | 0.95087 | 0.70142 | |

| Huang Rong | Original | 0.65032 | 0.40187 | 0.55124 | 0.70298 | 0.79965 |

| Fan | 0.84976 | 0.30125 | 0.45087 | 0.85213 | 0.94982 | |

| Ke Zhen E | Original | 0.45132 | 0.35087 | 0.64976 | 0.60213 | 0.49987 |

| Fan | 0.55243 | 0.32978 | 0.85124 | 0.68097 | 0.51032 | |

| Qiu Chu Ji | Original | 0.40098 | 0.30124 | 0.70213 | 0.65087 | 0.60132 |

| Fan | 0.48176 | 0.25987 | 0.90243 | 0.73154 | 0.70087 | |

| Zhu Cong | Original | 0.50187 | 0.35132 | 0.59987 | 0.70213 | 0.65098 |

| Fan | 0.58243 | 0.31976 | 0.68124 | 0.54897 | 0.68176 | |

| Han Xiao Ying | Original | 0.55042 | 0.45176 | 0.59897 | 0.75231 | 0.64958 |

| Fan | 0.65189 | 0.39843 | 0.65072 | 0.49876 | 0.54923 | |

| Han Bao Ju | Original | 0.40187 | 0.30054 | 0.69943 | 0.65128 | 0.55076 |

| Fan | 0.50231 | 0.27986 | 0.90178 | 0.80213 | 0.57142 |

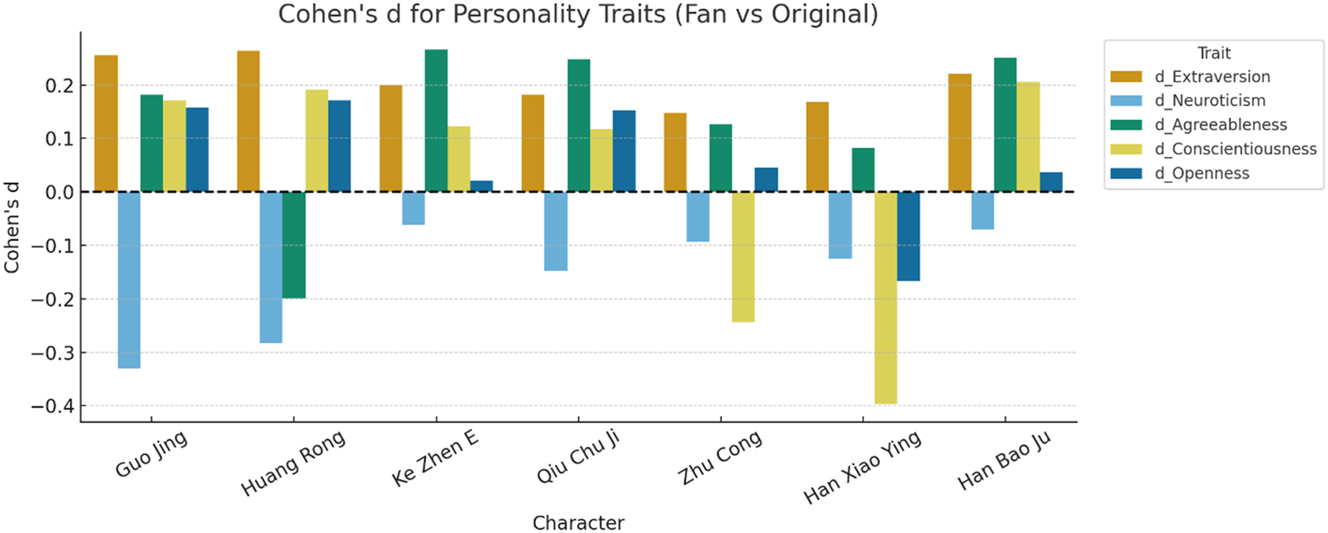

Based on these scores, we calculated Cohen’s d values to measure the effect size of the differences in personality traits between the original text and the fan translations and further derived a Composite Change Index (CCI) to summarize the overall magnitude of change for each character. Table 4 and Figure 2 present these results. Although the CCI values indicate that overall shifts are modest, the results also reveal variation across characters. Guo Jing and Huang Rong show comparatively larger changes, particularly in Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness, while figures such as Zhu Cong and Ke Zhen E remain relatively stable. At the level of specific traits, a consistent pattern emerges, with Extraversion often heightened and Neuroticism generally reduced in fan versions. Taken together, these patterns suggest that fan translations do not radically redefine character identities but recalibrate selected traits in ways that emphasize social assertiveness and emotional stability, thereby subtly reshaping how readers engage with the characters.

Character Cohen’s d and composite d value.

| Character | d_Extraversion | d_Neuroticism | d_Agreeableness | d_Conscientiousness | d_Openness | Composite_d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo Jing | 0.256 | −0.33 | 0.182 | 0.171 | 0.157 | 0.219 |

| Huang Rong | 0.264 | −0.283 | −0.199 | 0.191 | 0.171 | 0.222 |

| Ke Zhen E | 0.2 | −0.062 | 0.266 | 0.123 | 0.021 | 0.134 |

| Qiu Chu Ji | 0.182 | −0.147 | 0.248 | 0.117 | 0.152 | 0.169 |

| Zhu Cong | 0.148 | −0.094 | 0.127 | −0.243 | 0.046 | 0.132 |

| Han Xiao Ying | 0.168 | −0.125 | 0.083 | −0.397 | −0.167 | 0.188 |

| Han Bao Ju | 0.221 | −0.071 | 0.251 | 0.206 | 0.037 | 0.157 |

Cohen’s d effect sizes for personality traits (fan translation vs. original).

Lefevere’s (1992) contention that translation is a type of rewriting influenced by the target culture’s poetic and ideological systems rather than merely a linguistic act helps to clarify this kind of shift. Characters are not only translated as individuals but reconfigured as functional elements within the narrative. Their personalities, behaviors, and relationships are reframed to align with cultural values and storytelling conventions. The observed changes in characters such as Guo Jing and Huang Rong therefore illustrate how translators adapt central figures to resonate with familiar archetypes, while ensuring that supporting characters continue to serve the story’s structural needs.

The following sections build on this perspective by examining how these personality trait shifts reflect the translators’ cultural and narrative priorities, focusing on Guo Jing’s heroic archetype, Huang Rong’s portrayal as a heroine, and the relational dynamics of the supporting characters.

4.1.1 Guo Jing: The Reimagining of a Hero

In the fan translation, Guo Jing’s Extraversion rises from 0.50 to 0.65 (Cohen’s d ≈ +0.30). This shift to a more outgoing disposition reshapes his image as the leading daxia. In Jin Yong’s Chinese original, Guo Jing is first and foremost characterized by Confucian virtues such as humility, loyalty, and strong communal responsibility (Song 2023). His plain speech, respect for elders, and ready alliances undergird a moral clarity that hinges on ethical restraint and relational trust.

By contrast, the fan translation subtly amplifies his social assertiveness, often rendering his dialogue with a more confident tone and active phrasing. For example, in the Chinese original, Guo Jing advises Genghis Khan: “大汗, 我这匹红马脚力快极, 你骑了回去, 领兵来打, 我们在这里挡住敌兵。” (Chapter six) (literal translation: “Khan, my red horse is very fast, you ride back and bring reinforcements, we will block the enemy here.”). The fan translation condenses this into: “Khan, take my red horse, ride back, and lead the troops. We will hold the line here.” The shift from a deferential suggestion to a commanding directive highlights Guo Jing as a more decisive leader who actively rallies others.

A similar modification is made to his relationship with Huang Rong. At one point in the original, Guo Jing says, “蓉儿, 我跟你在一起, 真是欢喜。” (Chapter eight) (literal translation: “Rong’er, being with you truly makes me happy.”). The fan translation embellishes this to: “Rong’er, I am with you, and I am really, really, really happy.” Here, what was understated affection has been turned into a declarative and effusive sentiment, rendering Guo Jing emotionally forthcoming in a way that aligns more strongly with Western norms of heroic intimacy.

These examples demonstrate how source hesitation or restraint is recast into decisive statements and emphatic emotions in the fan translation. Whereas the source text situates Guo Jing’s heroism within a supportive network of shared values, the translation nudges him toward self-directed agency and charismatic visibility. This recalibration not only bridges cultural frameworks but also aligns Guo Jing with a model of heroism that prizes assertive communication and performative leadership. In this sense, the fan translation operates as a form of rewriting à la Lefevere, reshaping Guo Jing’s character to accommodate both the ideological expectations and narrative preferences of a new cultural environment.

4.1.2 Huang Rong: Highlighting Independence and Intelligence

Huang Rong is a central figure in Jin Yong’s Condor Trilogy, playing a key role across the series. In The Legend of the Condor Heroes, she is introduced in her teenage years as the daughter of Huang Yaoshi, the apprentice of Hong Qigong, and the lifelong partner of Guo Jing. Later, she becomes the first female leader of the Beggars’ Sect, embodying a multifaceted character who navigates roles as a romantic partner, a filial daughter, a strategist, and a leader. In the original text, Jin Yong’s portrayal of Huang Rong leans heavily on her beauty and charm, as demonstrated during her first appearance in Chapter Seven, where her physical allure is vividly described. However, the fan translation shifts its focus, emphasizing her intelligence and independence over her traditional roles as a companion or daughter. Rather than simply mirroring the original, the fan translation actively reinterprets Huang Rong’s role, drawing readers into a version of her character that prioritizes agency over tradition.

This shift is particularly evident in moments where Huang Rong asserts control over how others address her. In Chapter Eight, after revealing her true gender to Guo Jing, she says: 黄蓉嫣然一笑, 说道: ”我本是女子, 谁要你黄贤弟、黄贤弟的叫我?快上船来罢。” 黄蓉笑道: ”你也别叫我黄贤妹, 叫我作蓉儿罢。我爸爸一向这样叫的。” (literal translation: Huang Rong smiled and said, “I am actually a girl, who asked you to keep calling me Brother Huang? Get on the boat.” Huang Rong laughed and said, “Don’t call me Sister Huang either, call me Rong’er. My father has always called me that.”) Fan translation modified it as: Huang Rong smiled sweetly and said, “I’m a girl. Who said you could keep calling me Brother Huang? Get on the boat.” She chuckled and added, “And don’t call me Sister Huang either. Just call me Rong’er. That is the name I prefer. My father always calls me that.”

The fan translation emphasizes Huang Rong’s assertiveness in rejecting both “brother” and “sister” labels, choosing instead a name of her own. The phrase “That is the name I prefer” adds a clear declaration of self-identification. The shift in tone from playful self-disclosure in the original to a more self-directed assertion in translation marks a subtle but deliberate act of reclaiming voice. By foregrounding her preference for “Rong’er,” the fan translation reframes the interaction as one of agency and identity-making, not just playful banter. This moment exemplifies the broader tendency in the fan translation to reorient her character around autonomy and interiority.

This interpretive shift is also reflected in the computational analysis of Huang Rong’s personality traits. Notably, her Extraversion decreases by 0.2667, while Neuroticism increases by 0.2867. These changes suggest a deliberate reconfiguration of her character in the fan translation, one that emphasizes emotional depth and internal struggles over external charm and sociability. At the same time, her Agreeableness increases by 0.2004, indicating a stronger emphasis on her ability to connect with others on a personal level, while Conscientiousness and Openness decrease slightly (by 0.1929 and 0.1716, respectively). These changes collectively produce a Composite Change Index of 0.2237, reflecting a broader transformation in how Huang Rong is portrayed.

In the original text, Huang Rong is depicted as a clever, playful, and lively heroine whose quick wit and strategic thinking make her an essential partner to Guo Jing (Chen 2017). Her personality fits the traditional archetype of lively and intelligent heroines in Chinese literature, where female characters are celebrated for their charm, intellect, and problem-solving skills. However, her independence is often framed within the context of her relationships, particularly as a romantic partner and a devoted daughter. Her occasional moments of doubt or jealousy are understated, and her primary role is to support Guo Jing and drive the narrative forward through her cleverness.

The fan translation, however, reframes Huang Rong’s character by amplifying her emotional depth and independence. Although independence is not a Big-Five factor in itself, we infer it from the narrative shift, the reduced emphasis on relational roles, together with a lower Extraversion score, and from the translators’ explicit choices in paratextual notes. The increase in Neuroticism reflects a deliberate effort to explore her internal struggles and vulnerabilities, presenting her as a more emotionally layered character. Her insecurities and moments of self-doubt are given greater weight, making her struggles more visible and relatable to modern audiences. This shift aligns with Western storytelling conventions, where characters are often expected to balance external competence with internal emotional challenges. Such a portrayal enhances Huang Rong’s relatability while maintaining her core traits of intelligence and resourcefulness.

At the same time, the increase in Agreeableness suggests that the fan translation places greater emphasis on Huang Rong’s interpersonal qualities, portraying her as someone who is not only intelligent but also empathetic and supportive in her interactions. This adjustment enhances her emotional connection with other characters, reinforcing her role as a trusted ally and partner to Guo Jing. By contrast, the slight decreases in Conscientiousness and Openness may reflect a shift away from her role as an idealized, almost flawless heroine in the original text, allowing for a portrayal that feels more grounded and human. Thus, the fan translation portrays Huang Rong as more independent in her decision-making while maintaining her warmth and support for others. Here, her independence reflects personal agency rather than social detachment.

These changes also highlight a broader cultural negotiation in translating Huang Rong’s character. In the original Chinese context, her identity is deeply tied to her relational roles – as a daughter, a partner, and a disciple. Her cleverness and charm are celebrated within this framework, reinforcing traditional literary archetypes. In the fan translation, however, her independence and personal agency are given more prominence. By presenting her as a character who navigates both external challenges and internal conflicts, the fan translation adapts her to align with modern Western ideals of female protagonists, where autonomy and self-awareness are highly valued.

Ultimately, the fan translation preserves Huang Rong’s defining traits of cleverness and wit while expanding her emotional and interpersonal dimensions. This reinterpretation ensures she remains an integral and compelling figure in the story, bridging cultural expectations and resonating with a broader audience. Through these changes, Huang Rong emerges not just as a lively and intelligent heroine but also as a fully realized character whose independence and emotional depth take center stage.

4.1.3 Supporting Characters: Strengthening Relational Harmony

Beyond the protagonists, the translation also reshapes the supporting cast in subtle yet consistent ways. The supporting characters, such as Han Baoju and Qiu Chuji, also exhibit notable adjustments, particularly in the trait of Agreeableness. For example, Han Baoju’s score increases from 0.70 in the original to 0.90, while Qiu Chuji’s score rises from 0.70 to 0.85. The pattern points to a deliberate attempt to strengthen the cooperative and supportive image of the secondary characters, reinforcing their role as allies to the protagonist.

In the original Wuxia narrative, supporting characters often serve as moral guides and loyal companions, embodying the communal values that are central to the genre. Their distinct personalities and occasional conflicts with one another create a dynamic network of relationships that enrich the story and help the protagonist grow. However, in the fan translation, these characters are portrayed with heightened Agreeableness, emphasizing their selflessness and loyalty. This adjustment positions them more firmly as extensions of Guo Jing’s moral and heroic journey, reducing any potential tension or competition for narrative attention.

The reframing of these characters aligns with the target audience’s preference for relational harmony in storytelling. By emphasizing their cooperative traits, the translators ensure that the supporting cast contributes to Guo Jing’s development without overshadowing him. Meanwhile, their heightened Agreeableness reinforces the narrative’s themes of trust and solidarity, reflecting cultural values that prioritize teamwork and mutual support.

4.1.4 Personality as a Cultural Bridge

The observed changes in personality traits across central and supporting characters reflect how fan translators reinterpret the narrative to align with the cultural and narrative frameworks of the target audience. Guo Jing’s reduced Extraversion reframes his heroism as a quiet, introspective strength, resonating with individualistic ideals of leadership. Huang Rong’s heightened emotional expressiveness adds a layer of relatability that aligns with Western expectations for heroines who balance capability with emotional depth. Meanwhile, the increased Agreeableness of the supporting cast reinforces themes of loyalty and cooperation, ensuring that their roles remain focused on advancing the protagonist’s journey.

These changes demonstrate how personality traits serve as tools of cultural storytelling, allowing translators to reshape characters in ways that resonate with the ideological and poetic systems of the receiving culture. By reimagining these characters, the translators not only adapt the story to fit the expectations of the target audience but also preserve its core themes and narrative functions, creating a cultural bridge between the original and translated versions.

4.2 Digital Community Analysis

To verify whether our quantitative findings reflect audience perceptions, we analyzed forum posts about Huang Rong from the Spcnet Wuxia Forum (2005–2007). Using a TF-IDF approach, we extracted adjectives to build a word cloud that visualizes how fans collectively describe her character.

The word cloud (see Figure 3) reveals that fans most frequently describe Huang Rong as clever, independent, warm, and playful. These descriptors support our computational findings in several ways. The emphasis on warmth aligns with the observed increase in Agreeableness, highlighting her enhanced interpersonal appeal in the fan translation. However, the relationship between fan perceptions and computational measures requires careful interpretation. While adjectives like clever and intelligent reflect perceived mental agility, they should not be conflated with the Big Five trait of Openness, which our model shows decreases slightly in the fan translation. We interpret this decrease as reflecting simplified culturally specific references rather than diminished intelligence.

Most frequently used descriptors of Huang Rong in fan discussions (Spcnet.com, 2005–2007).

Computational analysis shows that Extraversion decreases while Neuroticism increases, suggesting fan translators have shifted Huang Rong’s portrayal toward greater introspection and emotional depth. The word cloud supports this interpretation through its combination of descriptors. Alongside spirited terms like mischievous and spunky, fans also emphasize qualities like independent, capable, and collected. This suggests readers appreciate both her playful nature and her emotional maturity, indicating a more psychologically complex character where vulnerability and composure coexist. Taken together, the descriptors align with our computational findings in meaningful ways. The emphasis on independence and capability corresponds to increased Neuroticism in our analysis, reflecting greater emotional complexity and self-reflection rather than social anxiety. The coexistence of playful and collected descriptors supports the observed decrease in Extraversion, suggesting a character who maintains her spirited nature while displaying more introspective qualities.

The convergence between computational analysis and community discourse demonstrates a coherent reinterpretation in the fan translation. Fan translators preserve Huang Rong’s core traits of intelligence and charm while amplifying her emotional complexity and autonomy. This dual-layered analysis illustrates how participatory translation selectively foregrounds characteristics that resonate with contemporary readers, aligning with Lefevere’s concept of rewriting texts to reflect new cultural expectations. The differences between some community descriptors and Big Five model outputs highlight that fans may emphasize qualities such as wit or warmth that extend beyond traditional personality taxonomies, suggesting the richness of character interpretation in participatory translation contexts.

5 Discussion and Implications

The results of this study demonstrate how fan translators engage in deliberate reinterpretations of character traits to align with the cultural expectations and narrative conventions of the target audience. Through the modification of personality dimensions such as Guo Jing’s Extraversion, Huang Rong’s emotional expressiveness, and the Agreeableness of the supporting cast, we observed how translation serves as a mode of cultural negotiation. These adjustments highlight how translators reshape characters to resonate with the values and archetypes of the receiving culture, while maintaining their narrative significance.

Building on these findings, this study extends Lefevere’s (1992/2016) rewriting theory into new territory by examining its application to character construction in translation. Additionally, it situates this process within the unique context of fan translations, which operate in participatory digital spaces where ideological and cultural dynamics are negotiated in real time. By integrating computational analysis of personality traits with qualitative observations from digital communities, we uncover how character reinterpretation in fan translations reflects broader cultural and ideological forces, particularly as they manifest in collaborative, fan-driven contexts.

Lefevere’s rewriting theory emphasizes how translations are shaped by the interplay of institutional patronage, ideology, and poetics within established literary systems. Ideology, in this framework, is defined as “the conceptual grid that consists of opinions and attitudes deemed acceptable in a certain society at a certain time” (Hermans 1999/2019, 127), enforced by patrons such as publishers and other institutional gatekeepers. However, our findings demonstrate that in fan translations, the forces shaping translation outcomes differ from those in professional or institutional contexts. Fan translations operate within a digital, participatory framework where ideological and poetic norms are negotiated collectively by the community rather than dictated by traditional patrons.

The case of Huang Rong illustrates this shift. Computational analysis shows that fan translations tend to amplify personality traits such as openness and extraversion, reshaping her characterization to emphasize qualities like wit, independence, and emotional warmth. These amplified traits align closely with the values and preferences of fan communities, as seen in our analysis of Spcnet.com discussions. The word cloud generated from these discussions highlights descriptors such as “clever,” “playful,” and “independent,” demonstrating how fans collectively interpret and articulate her character. This alignment suggests that fan translators and their communities actively engage in reshaping characters, not merely translating texts but transforming them to reflect communal ideals and subcultural values.

This process reveals a reconfiguration of ideology in fan translations. While Lefevere’s model situates ideology as a force imposed by institutional patrons, fan translations illustrate how ideology can emerge organically from collective meaning-making within digital spaces. For instance, the emphasis on Huang Rong’s independence and wit in fan translations reflects the ideological priorities of a participatory fan culture, where characters are reshaped to align with contemporary values of agency, relatability, and emotional depth. These priorities stand in contrast to the more constrained portrayals found in official translations, which are often shaped by institutional concerns such as marketability or fidelity to the source text.

In addition to highlighting a shift in ideological dynamics, this study deepens our understanding of the relationship between rewriting and character construction. By examining systematic differences in personality traits between fan and official translations, we demonstrate how translation functions as a site of character reimagination. Fan translations do not simply adapt characters for a new audience but actively reconstruct them, amplifying specific traits to resonate with the interpretive preferences of their communities. In the case of Huang Rong, this reconstruction foregrounds her wit and independence, traits that fan communities celebrate as central to her appeal. This suggests that rewriting in translation is not limited to textual or poetic dimensions but extends to the field of character portrayal, where translators and readers negotiate how fictional identities are constructed across multilingual and multicultural contexts.

Our methodological approach strengthens these findings through its dual focus. The combination of computational analysis of personality traits with qualitative observations of fan discussions yields both quantitative evidence of systematic shifts in character portrayal and rich insights into the interpretive processes that shape these transformations. The computational findings demonstrate measurable differences in Huang Rong’s personality traits between fan and official translations, while the analysis of Spcnet.com discussions highlight how these differences are shaped by collective negotiation within the fan community. Together, these methods illustrate how translation, as a form of rewriting, functions as a collaborative and iterative process in digital spaces.

These findings suggest that Lefevere’s rewriting theory remains highly relevant in understanding translation but requires adaptation to account for the unique dynamics of digital and fan-driven contexts. In traditional settings, rewriting is shaped by institutional gatekeepers who impose ideological constraints and poetic norms. In contrast, fan translations operate within a decentralized framework where collective interpretation and subcultural values replace institutional authority as the dominant forces shaping translation outcomes. This shift highlights the need to reconsider how ideology operates in translation, particularly in participatory digital environments where multiple translations coexist, interact, and evolve in response to community dialogue.

Ultimately, this study contributes to translation studies by extending the scope of rewriting theory into the realm of character construction and by revealing how ideology functions differently in fan translations. By focusing on the participatory dynamics of digital spaces, we demonstrate how translations are not merely products of individual translator choices or institutional constraints but are shaped by the collective values and interpretive priorities of their communities. This perspective challenges traditional assumptions about the forces shaping translation and highlights the transformative potential of digital platforms in enabling collaborative, community-driven approaches to rewriting.

6 Conclusions

This exploratory study introduces an interdisciplinary methodology that integrates translation studies, literary analysis, deep learning, and psychology to examine character portrayal in fan translations. By applying this framework to Jin Yong’s The Legend of the Condor Heroes, the research demonstrates how fan-based translations are shaped by collective interpretive priorities and subcultural values within digital communities, reflecting the participatory dynamics of online fan culture. The analysis of Huang Rong’s portrayal illustrates how fan translations systematically alter specific personality traits, revealing how fan communities collectively reshape literary characters to align with their shared cultural and ideological priorities.

Building on these findings, this study extends Lefevere’s rewriting theory into digital contexts, emphasizing how ideology operates differently in fan-driven versus institutional translation environments. The analysis shows that fan translators exercise significant interpretive agency in reshaping literary figures through community-based practices. Unlike traditional translations shaped by institutional gatekeepers, fan translations emerge from decentralized, participatory processes that reflect collective interpretations and values, highlighting a distinct model of literary adaptation driven by community engagement.

The character-centric methodology developed here provides valuable insights into an underexplored aspect of Wuxia translation studies. By focusing on how non-professional translators actively reconstruct literary characters, this research deepens our understanding of character translation across linguistic and cultural contexts. The findings contribute to broader discussions about amateur translation’s impact in the global literary sphere, particularly relevant given the contemporary coexistence of fan-based translations, AI-assisted translations, and professionally published versions in Chinese internet literature circulation.

As a proof-of-concept investigation, this research establishes that fan translations systematically alter character portrayals in measurable ways, with changes that align with community interpretations expressed in online discussions. While acknowledging significant methodological constraints, the integration of personality psychology frameworks with translation studies demonstrates the potential for computational approaches in character analysis and represents an emerging interdisciplinary direction that warrants further development.

The broader methodological framework offers the most significant contribution to the field, opening new possibilities for understanding how digital communities collectively reshape literary characters through participatory translation practices. Future research building on this foundation should expand to multiple translations, conduct extensive cross-cultural validation of personality models, and incorporate more comprehensive community analysis. Despite its limitations, this study contributes to ongoing discussions about translation as cultural mediation in the digital age, establishing a foundation for more robust interdisciplinary approaches to character-focused translation research.

Funding source: Direct Grant for Research 2025/26 (Project code: 4051279), Arts and Languages Panel, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Award Identifier / Grant number: 4051279

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: AI tools were used for proofreading.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Direct Grant for Research 2025/26 (Project code: 4051279), Arts and Languages Panel, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Argamon, S., S. Dhawle, M. Koppel, and J. W. Pennebaker. 2005. “Lexical Predictors of Personality Type.” In Proceedings of the 2005 Joint Annual Meeting of the Interface and the Classification Society of North America.Search in Google Scholar

Bacon-Smith, C. 1992. Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bamman, D., B. O’Connor, and N. A. Smith. 2013. “Learning Latent Personas of Film Characters.” In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 352–61. Sofia, Bulgaria: Association for Computational Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Bamman, D., T. Underwood, and N. A. Smith. 2014. “A Bayesian Mixed Effects Model of Literary Character.” In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers).10.3115/v1/P14-1035Search in Google Scholar

Boase-Beier, J. 2014. Stylistic Approaches to Translation. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315759456Search in Google Scholar

Bosseaux, C. 2007. How Does it Feel? Point of View in Translation: The Case of Virginia Woolf into French (No. 29). Rodopi.10.1163/9789401204408Search in Google Scholar

Bosseaux, C. 2013. “‘Bloody Hell. Sodding, Blimey, Shagging, Knickers, Bollocks. Oh God, I’m English’: Translating Spike.” Gothic Studies 15 (1): 21–32. https://doi.org/10.7227/gs.15.1.3.Search in Google Scholar

Boyd, R. L. and J. W. Pennebaker. 2017. Language-Based Personality: A New Approach to Personality in a Digital World. Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 18: 63–8.10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.07.017Search in Google Scholar

Chaturvedi, S., S. Srivastava, H. Daume III, and C Dyer. 2016, March. Modeling Evolving Relationships between Characters in Literary Novels. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 30 (1).10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10358Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Y. 2017. Roaming Nüxia: Female Knights-Errant in Jin Yong’s Fiction. Diss.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Y., W. Fan, X. Xing, J. Pang, M. Huang, W. Han, et al.. 2022. “Cped: A Large-Scale Chinese Personalized and Emotional Dialogue Dataset for Conversational AI.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.14727.10.36227/techrxiv.19919483.v1Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, J. 1992. “A Power Primer.” Psychological Bulletin 112 (1): 155–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.Search in Google Scholar

Cronin, M. 2010. “The Translation Crowd.” Tradumàtica: Tecnologies de la traducció 8: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.100.Search in Google Scholar

Devlin, J., M. W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova. 2019, June. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies 1: 4171–86. https://doi.org/10.26034/cm.jostrans.2006.737.Search in Google Scholar

Diao, H. 2023. “A Survey and Critique of English Translations of Jin Yong’s WuXia Fictions.” In Understanding and Translating Chinese Martial Arts, 49–70. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.10.1007/978-981-19-8425-9_4Search in Google Scholar

Díaz-Cintas, J., and P. Muñoz Sánchez. 2006. “Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation in an Amateur Environment.” JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation 6: 37–52. https://doi.org/10.26034/cm.jostrans.2006.737.Search in Google Scholar

Dwyer, T. 2012. “Fansub Dreaming on ViKi: “Don’t Just Watch But Help When You Are Free”.” The Translator 18 (2): 217–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799509.Search in Google Scholar

Flekova, L., and I. Gurevych. 2015. “Personality Profiling of Fictional Characters Using Sense-Level Links Between Lexical Resources.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.Search in Google Scholar

Flekova, L., and I. Gurevych. 2015. “Personality Profiling of Fictional Characters Using Sense-Level Links Between Lexical Resources.” In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Lisbon, Portugal.10.18653/v1/D15-1208Search in Google Scholar

Gignac, G. E. and E. T. Szodorai. 2016. Effect Size Guidelines for Individual Differences Researchers. Personality and Individual Differences 102: 74–8.10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, L. R. 1993. “An Alternative “Description of Personality”: The Big-Five Factor Structure.” In Personality and Personality Disorders. 2nd ed., 34–47. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Hermans, T. 2019. Translation in Systems: Descriptive and Systemic Approaches Explained, 2nd ed. Routledge.10.4324/9780429285783Search in Google Scholar

Jannidis, F. 2009. “Character.” In Handbook of Narratology, edited by P. Hühn, 14–29. Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110217445.14Search in Google Scholar

Jannidis, F., I. Reger, M. Krug, L. Weimer, L. Macharowsky, and F. Puppe. 2016. “Comparison of Methods for the Identification of Main Characters in German Novels.” DH: 578–82.Search in Google Scholar

Jenkins, H. 1992/2012. Textual Poachers: Studies in Culture and Communication. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.10.4324/9780203114339Search in Google Scholar

Jiménez-Crespo, M. 2017. “How Much Would You Like to Pay? Reframing and Expanding the Notion of Translation Quality Through Crowdsourcing and Volunteer Approaches.” Perspectives 25 (3): 478–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2017.1285948.Search in Google Scholar

Lakens, D. 2013. “Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for t-Tests and ANOVAs.” Frontiers in Psychology 4: 863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863.Search in Google Scholar

Lefevere, A. 1992/2016. Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9781315458496Search in Google Scholar

Li, D. 2021. “The Transcultural Flow and Consumption of Online WuXia Literature Through Fan-Based Translation.” Interventions 23 (7): 1041–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801x.2020.1854815.Search in Google Scholar

Littau, K. 2016. “Translation and the Materialities of Communication.” Translation Studies 9 (1): 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2015.1063449.Search in Google Scholar

Mahlberg, M. 2013. Corpus Stylistics and Dickens’s Fiction. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203076088Search in Google Scholar

Massidda, S. 2020. “Fansubbing: Latest Trends and Future Prospects.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility, 189–208.10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2_10Search in Google Scholar

McCrae, R. R., and O. P. John. 1992. “An Introduction to the Five‐Factor Model and Its Applications.” Journal of Personality 60 (2): 175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x.Search in Google Scholar

McIntyre, D., and J. Lugea. 2015. “The Effects of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Subtitles on the Characterisation Process: A Cognitive Stylistic Study of The Wire.” Perspectives: Studies in Translationology 23 (1): 62–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2014.919008.Search in Google Scholar

O’Hagan, M. 2009. “Evolution of User-Generated Translation: Fansubs, Translation Hacking and Crowdsourcing.” The Journal of Internationalization and Localization 1 (1): 94–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/jial.1.04hag.Search in Google Scholar

Pérez-González, L., and Ş. Susam-Saraeva. 2012. “Non-professionals Translating and Interpreting: Participatory and Engaged Perspectives.” The Translator 18 (2): 149–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506.Search in Google Scholar

Polzehl, Tim. 2015. Personality in Speech: Assessment and Automatic Classification. Heidelberg: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-09516-5Search in Google Scholar

Pugh, S. 2005. The Democratic Genre: Fan Fiction in a Literary Context. Bridgend: Seren.Search in Google Scholar

Saucier, G., and L. R. Goldberg. 1996. “Evidence for the Big Five in Analyses of Familiar English Personality Adjectives.” European Journal of Personality 10 (1): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0984(199603)10:1<61::aid-per246>3.0.co;2-d.10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199603)10:1<61::AID-PER246>3.0.CO;2-DSearch in Google Scholar

Song, W. 2023. “Worlding Jin Yong’s Martial Arts (WuXia) Narrative in Three Keys: Narration, Translation, Adaptation.” In A World History of Chinese Literature, edited by Y. Zhang, 253–63. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003167198-27Search in Google Scholar

Srivastava, S., S. Chaturvedi, and T. Mitchell. 2016. “Inferring Interpersonal Relations in Narrative Summaries.” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 30 (1). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10349.Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, B. 2011. “What is Fanfiction and Why Are People Saying Such Nice Things About It?” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies 3: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5250/storyworlds.3.2011.0001.Search in Google Scholar

Van de Vijver, Fons J. R., and Kwok Leung. 2021. Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research, Vol. 116. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Van Steenhuyse, V. 2011. “Jane Austen Fan Fiction and the Situated Fantext.” English Text Construction 4 (2): 165–85. https://doi.org/10.1075/etc.4.2.01van.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, K., and D. Li. 2021. “Normalization, Motivation, and Reception: A Corpus-Based Lexical Study of the Four English Translations of Jin Yong’s Martial Arts Fiction.” In New Perspectives on Corpus Translation Studies, edited by V. X. Wang, L. Lim, and D. Li, 117–42. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-4918-9_7Search in Google Scholar

Wu, K., and D. Li. 2022. “Are Translated Chinese WuXia Fiction and Western Heroic Literature Similar? A Stylometric Analysis Based on Stylistic Panoramas.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 37 (4): 1376–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac019.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Weilai. 2022. Stylistic Dialogue Generation Based on Character Personality in Narrative Films. PhD diss. Bournemouth University.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Chongqing University, China

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A Survey-Based Analysis About Consequential Risk of Errors and Ethical Complexities in the Use of AI-Powered Machine Translation in High-Stakes Situations

- Temporal Dynamics of Emotion and Cognition in Human Translation: Integrating the Task Segment Framework and the HOF Taxonomy

- Big Five Personalities Across 200 Years: A Large-Scale Study on the Description of Male- and Female-Dominated Occupations

- Modeling Character in Translation: Computational and Qualitative Insights from Wuxia Fan Translations

- Review Articles

- A Synthetic Review of MALL Research: Artifact, Environment, and Task

- A Systematic Review of the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Second Language Writing Education

- Interview

- Literary Awards as Humanities Data: Measuring Prestige in the Digital Age – an Interview with James English

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A Survey-Based Analysis About Consequential Risk of Errors and Ethical Complexities in the Use of AI-Powered Machine Translation in High-Stakes Situations

- Temporal Dynamics of Emotion and Cognition in Human Translation: Integrating the Task Segment Framework and the HOF Taxonomy

- Big Five Personalities Across 200 Years: A Large-Scale Study on the Description of Male- and Female-Dominated Occupations

- Modeling Character in Translation: Computational and Qualitative Insights from Wuxia Fan Translations

- Review Articles

- A Synthetic Review of MALL Research: Artifact, Environment, and Task

- A Systematic Review of the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Second Language Writing Education

- Interview

- Literary Awards as Humanities Data: Measuring Prestige in the Digital Age – an Interview with James English