Abstract

Nigerian literature has long used paper and film as primary media for cultural expression and exporting African culture and civilisation. However, the advent of datafication and botification in the turn of millennium, particularly within social media, has brought forth a new era. This shift is peculiarly evident in the ‘Twitterverse’, where Nigerian Twitterature, or ‘Xerature’, emerged in 2014, largely due to the work of Nigerian-American novelist Teju Cole. His minimalist ‘Twittories’ addressed Nigeria’s socio-political landscape. This article aims to raise awareness, trace the origins, and define this evolving genre while proposing canonisation and methodological approaches to its study reported in a sustained reading of Hafsat Dauda (@HafsahDauda)’s Las, Las Nigeria is Home 2020.

1 Introduction

In this study, we focus on what constitutes Nigerian Twitterature, its evolution, how to read it, and the process of canonising this local Twitterature for mainstream scholarship. This is our significant contribution to the development of African electronic literature in this era of digital revolution and acculturation.

The literary phenomenon of Twitterature emerged in July 2006 (Raguseo 2010), driven by the rise of short-form literature characterised by nano-linguistics, i.e., concise linguistic forms, semantic prosody, and digital semiotic elements expressed on the Twitter platform. This trend is also influenced by the declining attention span of young people. Canadian researchers have established that between 2000 and 2015, the average attention span dropped by a third, from 12 to 8 s (Stokel-Walker 2021). This shift in cognitive engagement among millennials forms the bedrock of Twitterature and its associated reading modalities.

Twitterature, or Xerature[1], is a multimodal literary practice constrained by a limit of 280 characters (originally 140), making it a distinctive and incisive form of expression. Like traditional print literature, Twitterature is polymorphic, encompassing a variety of genres and forms (Waliya 2023a). However, X (formerly Twitter)’s premium artificial intelligence feature, Grok, extends these possibilities beyond normal technical constraints by editing tweets, aiding in image generation, assisting with coding tasks, and responding to queries (X 2024). It is essential to recognise Twitterature as a global literary form, unbounded by geographical and linguistic barriers, largely due to the Internet and tools like Google Translate and Grok, which are integrated into the microblogging platform (Waliya 2023b; X 2024). These tools enhance its utility for creative social causes, particularly in fostering good governance through digital activism (Waliya 2020). The study of Nigerian Twitterature is particularly significant because it also stems from activism. Every new medium of communication, such as X (formerly Twitter), influences the ethnography, anthropological and narrative structures of the societies that adopt it. Bouchardon and Riguet (2022) highlight this by referencing Jack Goody’s theory of Graphical Reason and Bruno Bachimont’s Computational Reason, which assert that “each new technical medium transforms our ways of thinking, knowing, and acting” (p. 17). Moreover, this transformation is fuelled by interactive reading experiences. Changes in the format or platform of reading inevitably alter how we experience and understand the texts we engage with (Walsh and Horowitz 2016). Nigerian society, being highly active on X (formerly Twitter), reflects this shift, prompting a re-examination of the canonicity of its literary practices.

Canonising Nigerian Xerature as literature involves establishing a standard model that other works can follow to gain public acceptance. However, the concept of the literary canon has evolved in the digital age due to the rise of digital poetics and the democratisation of internet content. Today, electronic literature, as a form of collaborative creative writing, is accessible to all, with restrictions primarily determined by the chosen nano-literary genre and the technological constraints of the platforms, rather than the content of the literary expressions themselves (Waliya 2023b; Rucar 2015).

Consequently, canonicity in this sense is not about restriction and exclusion of other works but it is all about inclusive digital arts that conform to the digital poetics and text configuration of each technology of discourse as well as projecting Nigerian socio-cultural realities.

We shall use Xerature and Twitterature interchangeably in this study, as both refer to the same concept, though Xerature is our own coinage.

2 Nigerian Twitterature, Twitterateurs, and Its Historical Development

Twitterature represents a new literary genre that exists within the digital realm. It originated through the efforts of collaborative literary groups in Europe and America. Notable early contributors include the Anglo-Saxon group Booktwo (https://x.com/booktwo), Twittories (www.twittories.wikispaces.com) in Ireland, The Story So Far in the United Kingdom, and the Spanish group Rayuela (https://x.com/rayuela), which began tweeting literary content as early as 2006 when the platform was launched. These groups referred to their practice as ‘literature 2.0’ (Raguseo 2010). In 2007, Canadian poet Mélusine (@TwittLitt) began publishing nano-poems on Twitter, capturing a wide audience (Bataillon 2011). In the United States, Dene Grigar launched the 24-Hr Micro-Elit Project in 2008, collecting 85 short stories that explored life in 21st-century urban settings (Pisarski 2017; Grigar 2016). By December 29, 2009, Twitterature had evolved into a recognised term, deriving its name from the best-selling book by Aciman and Rensin, Twitterature: The World’s Greatest Books in 20 Tweets or Less. This book summarised 20 classical works of world literature (Aciman and Rensin 2009). The term quickly gained traction, leading to widespread academic discussions, competitions, and critiques within literary circles (Moisan 2012). By 2011, Twitterature was declared the ‘Literature of the Year 2011’ (Brou 2011). In the following years, the platform saw an increase in Twitterbots, leading to the rise of procedural, robotic literary creativity (Waliya 2023a).

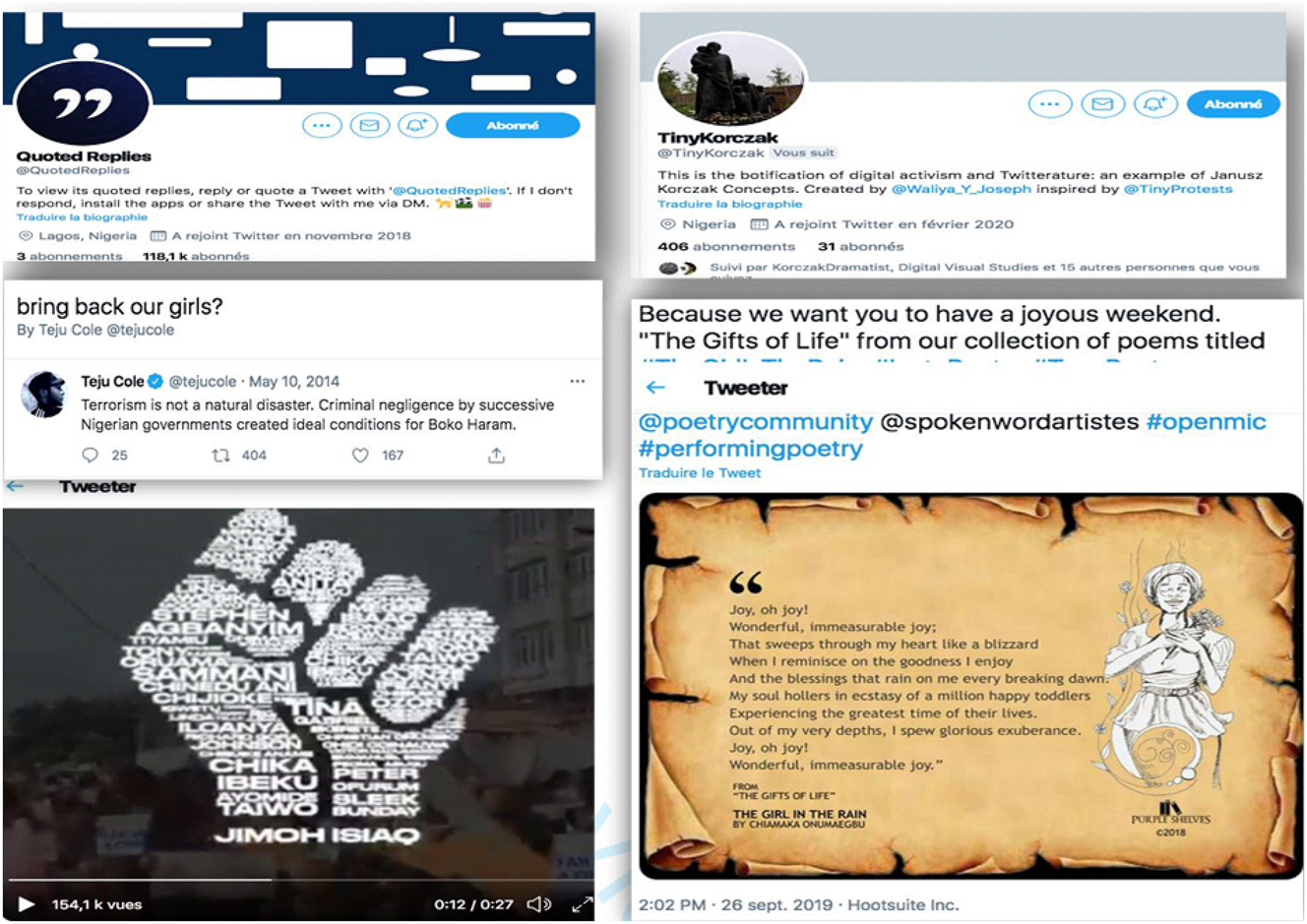

As for Nigerian Twitterature, its roots can be traced to short stories on Twitter by Teju Cole (@tejucole), such as A Piece of The Wall (2014), Hafiz (2014), Small Fates (2014), and more notably Bring Back Our Girls?, published on May 3, 2014. These are considered the earliest examples of Nigerian Twitterature (Cole 2014a; Waliya 2023a; Cole 2014b). Bring Back Our Girls? Is a homo-diegetic tweetfic, written to complement the global activism hashtag #BringBackOurGirls campaign, initiated by Michelle Obama, which sought to rescue 276 Chibok schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram (Cole 2014a). Nigerian Twitterary storytellers, or Twitterateurs, often create multiple Twitter accounts corresponding to the characters in their Twifics, using interactions marked by ‘@’ to facilitate dialogue or hashtags to thread their narratives, ensuring coherence and fluidity in storytelling, similar to other Twitterateurs worldwide (Waliya 2022). In December 2019, Poetry House Nigeria was established as a collaborative writing hub aimed at encouraging young Nigerian writers, poets, and spoken word artists (@NigeriaPoetry 2020). This group uses multimedia, such as photographs and videos, to overcome Twitter’s character limitations and maximise creative potential. During the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, the initiative ‘Poetry for Nigeria, by Nigerians’ (@NigeriaPoetry) emerged, along with the Instagram handle @nigerian_poetry, to give voice to latent writers and foster poetic cultural production among Nigerian poets both in Nigeria and the diaspora (Poetry for Nigeria, by Nigerians 2020). These groups have become an avenue for expressing social and political critiques, as evident in works like Las, Las Nigeria Is Home by Hafsah S. Dauda (Dauda 2020) and #EndSARS BOT (@endsarsbot_) by Abdulfatai Suleiman (Suleiman 2019), among others.

3 What Counts as Nigerian Twitterature, Its Canonicity and Reading Methods

Twitterature, while rooted in the broader tradition of Nigerian literature, stands out due to its digital creation, viral distribution, and engagement with the larger Twitterverse community. Unlike traditional literature, Nigerian Twitterature is characterised by its digital materiality, which includes factors such as accessibility, visibility, and interactivity within the Twitter ecosystem. It is a form of nano-literature that relies heavily on digital and algorithmic culture, shaped by the constraints and affordances of the Twitter platform, yet creatively circumventing technical restrictions by using embedded texts on images and incorporating videos to express deeper emotional attachments to Nigeria. The concept of Twitterature is linked to the early days of computer programming, where constraints like memory space led to concise coding practices (Gere 2008). This idea may have inspired Twitter’s original 140-character limit, which was expanded to 280 characters in 2018. Twitterature, therefore, embodies a form of rational reductionism and minimalism, simplifying human expression into a concise form, yet remaining powerful enough to influence societal events.

Nigerian Twitterature is defined as short fictional stories, poems, plays, riddles, or proverbs confined to 280 characters (previously 140). These works are enriched by the generative and interactive nature of Nigerian themes, cultures, folklore, and heritage, all expressed through the unique medium of Twitter, now X, with its expanded capabilities (see Figure 1).

Example of Nigerian Twitterature.

Reading Nigerian Twitterature requires an understanding of its multimedia elements, techno-words, and techno-signs. These components – emojis, photos, gifs, videos, hashtags, and hyperlinks – are essential for effectively engaging with Twitterature (Waliya 2023a). Twitter’s threading feature, for example, organises longer narratives, requiring readers to navigate from the top of a thread to the bottom to fully comprehend the story.

However, Twitterature can also present challenges. The integration of hypertext links can lead to digressions, creating what is known as “serendipity” (Ensslin 2007, 35). In electronic literature, serendipity refers to the act of moving back and forth or digressing from a lexia or the main subject via internal or external links. This can cause confusion, known as the “aesthetics of frustration” (Bootz 2016, 156), where readers must revisit the text to fully understand the narrative – a process termed the “aesthetics of revis (ita)ion” (Ensslin 2007, 41). These methods or approaches to reading are uniquenly present in digital texts. Additionally, like other forms of electronic literature, Twitterature often controls the reading experience, dictating how and when readers engage with the text, unlike traditional literature where readers have more freedom. This controlled interaction reflects the influence of data influxes and digital structures on modern reading practices.

As social media evolves, so too does the practice of Twitterature. Changes in Twitter’s ownership, policies, and monetisation in June 2022, alongside the emergence of new platforms like Meta’s Threads, present both challenges and opportunities for the future of Twitterature. Despite these shifts, Twitter remains a key platform for digital literary creativity, with its large user base ensuring the ongoing relevance of literary tweets in the digital age. The issue of remuneration for Twitterateurs, raised by critics such as Delsart (2018), has been addressed. Twitter now rewards artists for their content, encouraging the continued growth of Twitterature within both the literary and technological spheres. It worth noting, however, that although Twitter still boasts 250 million daily active users, this figure has dropped by 30 % in 2024 (Pequeño IV 2024).

Regarding the reading methodologies applicable to Nigerian Twitterature, for instance, Hafsat Dauda’s Las, las Nigeria is Home (2020) (Dauda 2020) fall within the categories of linear reading (thanks to thread affordance), close reading, serendipitous reading, revision and re-visitation reading, and visual performative reading. However, metonymical reading is excluded as it is not a generative form of Twitterature. Metonymical reading differs from other forms of reading twittext, as it is specific to Twitterbot poetry and Twitterbot fiction, which are generative, stochastic, and procedural. It means “it generates itself within a given posting time frame, without a clear beginning or ending. It is read metonymically” (Waliya 2023a, 69). Hence, metonymical reading involves reading a part of the text to refer to the understand of the whole digital text. This method was developed by Waliya (2019–2023) to analyse generative electronic literature in his Master’s thesis at Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria. Ajah (2022) adds that reading in the Twitterverse, particularly multimodal tweets containing emojis and videos mixed with text, is viewed as on-screen performance, where readers become spectators who read, view, and interact with the content and media. Twittext is thus perceived as “an event due to multimodality” (Ajah 2022, 682). Therefore, reading twittext should also be approached as a performative act of cognition and data visualisation within the digital ecosystem.

4 The Reading Experiment of Hafsah S. Dauda’s Tweet-Videopoem

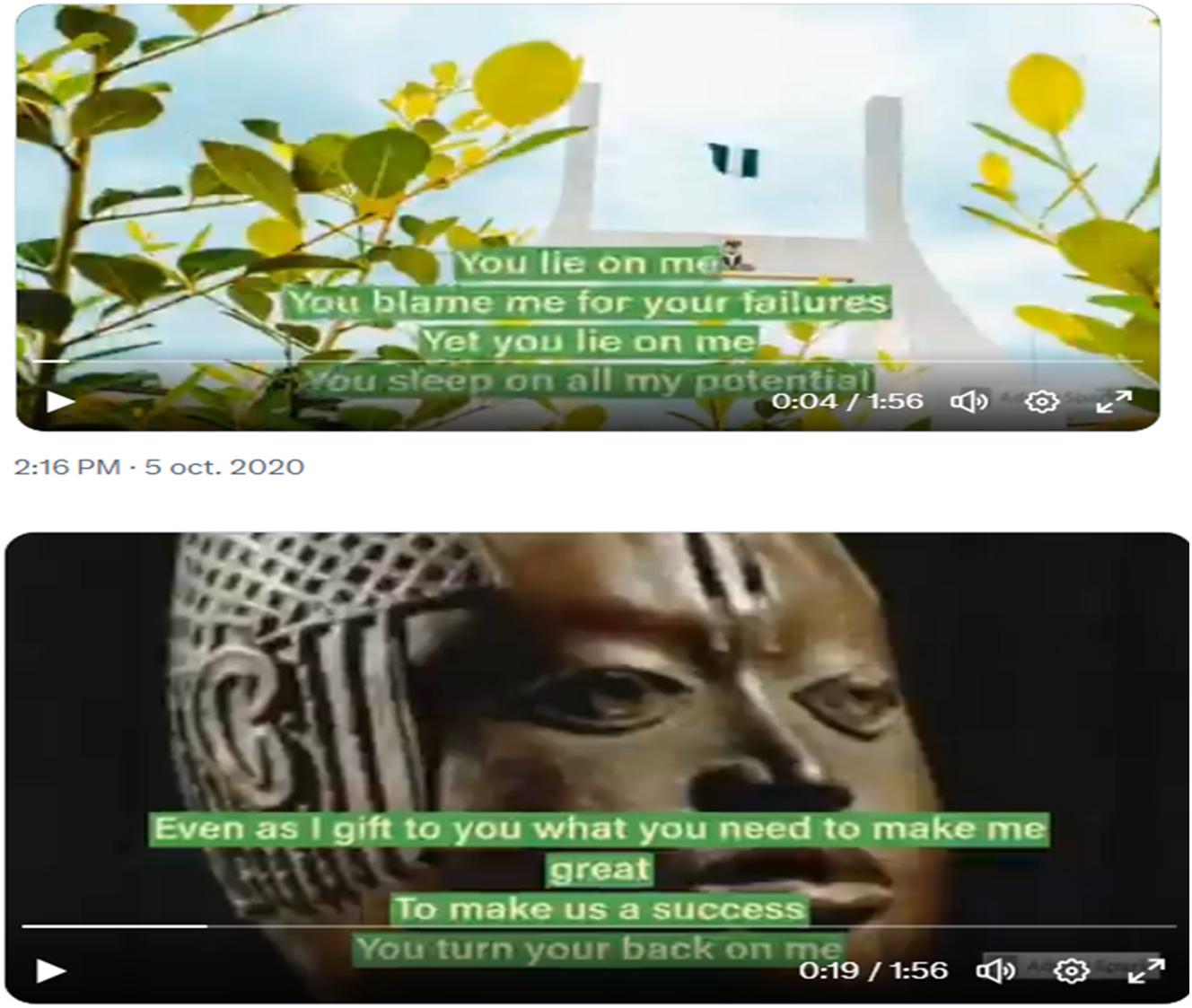

Las, las Nigeria is Home (Figure 2) explores the intricate blend of textual, visual, and auditory elements, combining to express deep emotions about Nigeria’s state on the 60th anniversary of its independence. Hafsah Dauda’s work, created during the EndSARS protests on the 5th of October 2020, delves into a range of cultural semiotics, videos, and images to convey her frustrations and hopes for Nigeria. The tweet-poem leverages the affordances of media embedding on Twitter, contributing to the large group of collaborative tweet-poets under the guise of the Nigerian Tweet-poetry Anthology, titled Poetry for Nigeria, by Nigerians (@NigerianPoetry) in 2020.

Title of Hafsah’s Tweet-videopoem.

The modalities of reading Twitterature have been discussed extensively in Waliya’s recent works, such as Twittérature: Lecture Symétrique du Twitterbot-Théâtre (2022) and Twittérature: Analyse Technodiscursive de La Twitterbot Poésie de Leonardo Flores (2023), where he identifies Twitter’s features – such as threads, hashtags, technical character constraints, comments, likes, attached photographs, videos, links, shares, Google Translate, emojis, etc… – as elements that facilitate comprehensive reading in the Twitterverse, particularly for arranging tweets in top-to-bottom linear readings of non-generative literary tweets. Hafsah Dauda employed hashtags like #nigeria, #change, #youth, #internationalyouthday, #poetry, and #poetrycommunity, which encapsulate the main themes and intended audience of Las, las Nigeria is Home (2020).

This tweet-videopoem shares thematic similarities with Jimoh Tolulope (@LOPE_64)’s Palliative versus Corruption (2020), In the Memory of the Fallen (2020), A Government of Silence (2020), and Dicenna Emeka (@dicennaemeka)’s Changes (2020), which centre their social messages on the interplay between Nigerians, the Nigerian government, and the youth.

The metric structure of Las, las Nigeria is Home alternates between quatrains and tercets, with each stanza accompanied by symbolic images that emphasise Hafsah’s connection to her country. The stanzas transition from expressions of frustration, where Nigeria is personified as a failing entity, to a gradual shift towards optimism as Nigeria responds to Hafsah, asking for patience and hope.

Stanzas I and II (Figure 3) of Hafsah S. Dauda’s tweet-poem are free quatrains, inscribed as white textual verses on a green foreground. These stanzas vividly express Hafsah’s frustrations, encapsulating the emotional toll of her experiences in Nigeria. Despite her significant investment in the country, it feels as though her efforts are in vain. She personifies Nigeria as a living man, confronting him with the accusation that he has squandered her talents. Yet, in a poignant twist, Nigeria shifts the blame onto her, suggesting that she has not fully maximized her potential.

Stanzas I and II.

These picturesque stanzas resonate even more deeply when heard in her spoken word performance, where the weariness in her voice adds a layer of emotional intensity. The rhymes and rhythms in her verses function as “pluriplanar units, harmonised across the vocalic, visual, and textual dimensions” (Hébert 2019, 216). These elements are segmented, serialised, and arranged to evoke meaning in the reader’s mind.

Visually, the image of a budding tree juxtaposed with the towering City Gate in Abuja serves as a powerful metonym for Nigeria. The tree, symbolising the younger generation represented by Hafsah, is dwarfed by the height of the City Gate, which symbolises the oppressive weight of Nigeria on its younger citizens.

Additionally, the sculptured head of a woman on the dark background in Stanza II represents Hafsah herself, a woman who relentlessly strives for success despite the continuous frustration imposed by the political system in Nigeria. This imagery highlights the futile nature of her endeavours, as her efforts are repeatedly thwarted by the country’s entrenched political structures.

Stanzas III and IV of Hafsah S. Dauda’s tweet-poem continue her poignant lamentation, both structured as free tercets. In Stanza III, Hafsah uses the image of a painted face adorned with the Nigerian flag, with eyes brimming with tears, to depict the heartbreak and pain she experiences whenever she reflects on her identity as a Nigerian. This visual metaphor captures her despair over Nigeria’s bleak future, especially in contrast to the optimism she sees in other countries, where citizens are assured of a brighter future. At the time of composing this poem, Hafsah was studying psychology in the UK, and her psychic reflections led her to perceive hope for other nations while her hopes for Nigeria felt increasingly crushed.

Stanza IV features a symbolic figure of ‘60’ as a background to the white-text tercet, representing Nigeria’s 60th anniversary of independence. Beneath this symbolic figure, the letters ‘TOGE’ are rendered illegible, while the word ‘THER’ is bold and legible. This visual noise, a technique borrowed from American visual poets, symbolises the dissonance in Nigeria: though Nigerians are ostensibly united, in reality, they are deeply divided Engberg (2007). describes this tactic “of illegibility to destabilize conventional modes of reading resemble the visual strategies of some digital visual noise poems, particularly in the use of layered overprinting.” (p. 134). In Hafsah’s poem, this erasure of some letters while leaving others legible signifies the noise about unity that belies the actual polarization within the country.

Hafsah’s pessimism extends to the broader narrative of Nigeria’s 60 years as a sovereign State. She expresses doubt that these six decades have brought any meaningful hope to its citizens. If Nigeria, after 60 years, cannot unify its diverse ethnic groups and move beyond its colonial past, Hafsah suggests that the nation is destined to remain stagnant. Her pessimism is further underscored by the appended images of former and current Nigerian leaders, whom she views as failures for not fulfilling the promises of independence. These leaders, in her view, have not led Nigerians to the ‘promised land’ envisioned at the nation’s founding.

Stanza V of Hafsah S. Dauda’s tweet-poem is a tercet overlaid on images reflecting Hausa-Fulani cultural symbols, continuing the theme of Nigeria’s ‘foolish’ state due to ethnic polarization. The use of these images as the backdrop underscores the deep-seated ethnic divisions that have sown discord and marginalization within the country, particularly among the diverse populations in Northern Nigeria. By focusing on the Hausa-Fulani, Hafsah highlights these tensions and the sense of exclusion felt by other ethnic groups in the North, further emphasising the fractured nature of the nation.

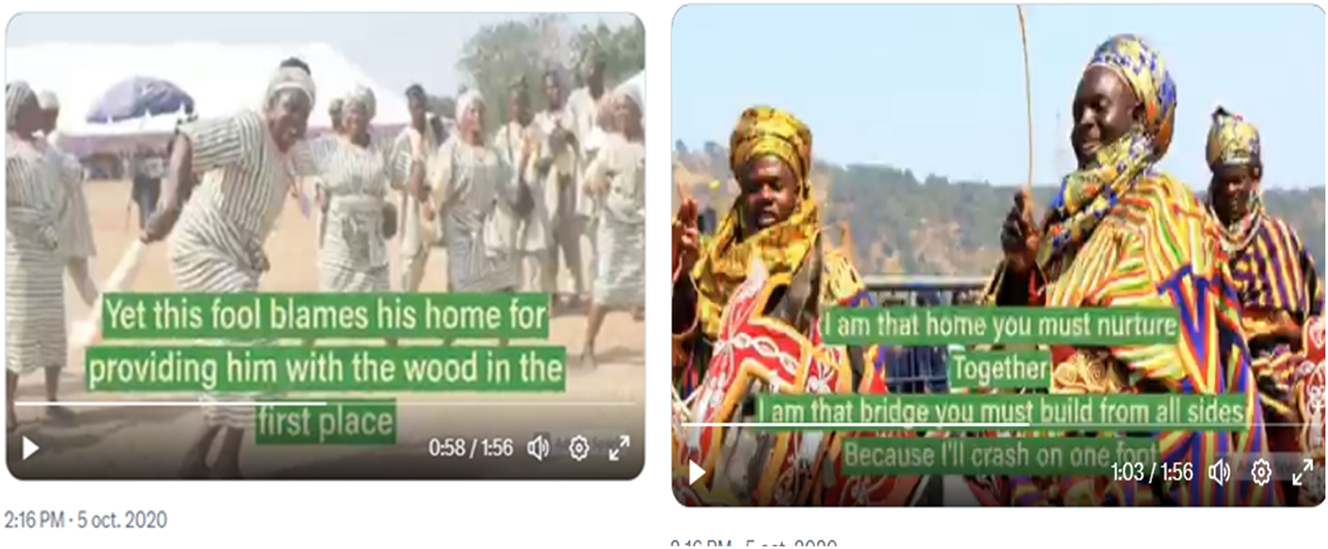

Stanza VI shifts to a quatrain, where Hafsah delves into the ‘foolishness’ of Nigeria, which she attributes to the nation’s self-destructive tendencies – manifested through madness, greed, and corruption (Figure 4). This stanza portrays a country that, instead of harnessing its potential and fostering unity, has allowed these vices to drive it towards ruin. The deliberate transition from a tercet in Stanza V to a quatrain in Stanza VI (Figure 5) mirrors the escalation of Hafsah’s critique, moving from the issue of ethnic polarity to a broader condemnation of the systemic issues that have plagued Nigeria. Through these stanzas, Hafsah paints a vivid picture of a nation ensnared by its own shortcomings, unable to rise above the challenges that have defined its post-independence history.

Stanzas III and IV.

Stanzas V and VI.

In Figure 6, representing Stanzas VII and VIII of Hafsah S. Dauda’s tweet-poem, the visual and textual elements continue to deepen the critique of Nigeria’s failures and the complex relationship between the poet and her country whereas Stanza VII is a white-text tercet superimposed on a green background featuring cultural images of women dancing in front of men, all dressed in traditional attire. The scene captures a moment of cultural celebration, yet Hafsah juxtaposes this with her ongoing disenchantment with Nigeria. The imagery of women dancing to the men’s drums symbolises the roles and expectations within society, reflecting a broader metaphor for how Nigeria has shifted the blame for its failures onto its natural resources rather than taking responsibility for its actions. This stanza critiques the nation’s tendency to externalize blame rather than addressing the root causes of its issues.

Stanzas VII and VIII.

Stanza VIII transitions into a quatrain, where Hafsah personifies Nigeria, allowing it to respond to her accusations. Nigeria presents itself as a ‘tender being’ – a fragile entity that requires careful nurturing and a channel that connects all its citizens (Figure 7). This stanza suggests that for Nigeria to thrive, it must emphasise holistic national development, ensuring that no geopolitical zone is marginalised. If Nigeria fails to achieve this inclusivity, it risks ceasing to exist as a unified entity. The background images in Stanza VIII, showing a motion of royalty, signify Nigeria’s potential for glorious progress. This regal imagery contrasts with the poem’s earlier critique, suggesting that despite its flaws, Nigeria still holds the promise of greatness if it can overcome its internal divisions and failures.

Stanzas IX and X.

Through these stanzas, Hafsah conveys a complex emotional landscape – one of deep frustration with Nigeria’s current state, but also a recognition of the nation’s potential if it can rise to the challenge of inclusive development. The interplay of cultural imagery and poetic text enhances the poem’s message, making it a powerful commentary on Nigeria’s past, present, and future.

Stanza IX continues as a quatrain superimposed on an image of drummers playing talking drums, symbolising Nigeria’s hopeful evolution into greatness. This stanza suggests that, despite the country’s current state, it still holds the promise of emerging as a significant power. Nigeria is portrayed as a ‘giant child’ at its 60th Independence anniversary, with a future that surpasses even Hafsah’s expectations. The image of the drummers, traditional symbols of communication and celebration, underscores Nigeria’s potential for growth. The stanza reflects a plea for patience, as Nigeria asks Hafsah – and by extension, all Nigerians – to believe in its capacity for greatness despite current shortcomings whilst Stanza X features a tercet overlaid on an image of the sports supporters’ club of Nigeria. This visual representation suggests a shift in Nigeria’s tone, responding to Hafsah’s critique with a request for understanding and support. Nigeria acknowledges Hafsah’s frustrations but urges her to be less harsh. The image of enthusiastic sports fans encourages Hafsah to cheer for the country, paralleling the way sports supporters back their team through thick and thin. This stanza signifies Nigeria’s desire for solidarity and confidence from its people (Figure 8).

Stanzas XI and XII.

Stanza XI reinforces this sentiment by declaring Nigeria as an eagle – a symbol of strength and resilience. This metaphor indicates that Nigeria is a force to be reckoned with, one that can be relied upon for future success. The stanza’s final verses invite Hafsah to join Nigeria in its journey, recognising her as a fellow compatriot. This inclusive gesture emphasises the notion of collective effort and shared destiny, urging Hafsah to rise together with the nation rather than remain disillusioned. Through these stanzas, the poem transitions from critique to a hopeful dialogue, portraying Nigeria as a country still in development but with a strong foundation and potential for greatness. The interplay of imagery and text underscores the evolving relationship between Hafsah and her country, reflecting a complex blend of disappointment, hope, and encouragement.

Stanza XII includes a tercet overlaid on images of the Nigerian sports supporters’ club lifting the Nigerian flag and cheering on their players. This visual and textual combination reinforces the metaphor of rallying behind the nation and its leaders. Just as the supporters raise the flag to show their commitment, Hafsah’s poem suggests that all Nigerians must stand united to propel the country forward. This unity and support are crucial for achieving national goals and overcoming challenges.

Stanzas XIII and XIV continue this theme of national pride and solidarity, as shown in Figure 9. In Stanza XIII, Nigeria responds to Hafsah’s earlier disillusionment by asserting its deep connection to her. Despite her frustrations and attempts to distance herself – whether by changing her name, nationality, or appearance – Nigeria remains a fundamental part of her identity. This stanza emphasises that no matter where Hafsah goes or what she does, Nigeria is an intrinsic part of who she is. The imagery and text convey that the bond with Nigeria is inescapable and enduring.

Stanzas XIII and XIV.

In Stanza XIV, Hafsah’s tone shifts from frustration to a hopeful call for collective effort. She uses the interjection “Las, las” to underscore her message, which, in Nigerian youth language, means “at last” or “in the end.” This term, often used on social media, reflects a sense of finality and emphasis. This language choice connects Hafsah with the youth, creating a shared understanding within her generation. This young language “may be likened to a class language which is developed because of a desire to establish an identity apart or a distinct speech code that defines closeness or in-group relations …” (Nzuanke and Ajimase 2014, 88). By integrating this colloquial expression, Hafsah connects with a younger audience who understands this in-group language. She encourages all Nigerians to contribute to building their nation, reinforcing the idea that despite her grievances, Nigeria is ultimately her home and a place worth investing in.

Figures in the text highlight key stanzas, such as Stanzas I and II, where Hafsah’s emotional distress is palpable, and Stanzas IX and X, where Nigeria begins to plead for understanding and unity. The poem uses visual noise techniques, symbolic imagery, and Naijá language to communicate its message. However, the poet is living in the UK while writing for her other fellow Nigerians to be optimistic. How sincere and genuine is her emotional attachment to Nigeria? Was it nostalgic? If she really trusts in her dream for Nigeria, should she have remained in Nigeria to study the psychology she was mastering in the UK?

5 Conclusions

This work has defined and critiqued Nigerian Twitterature, examining its canonicity through the examples of Hafsat Dauda’s Las, las Nigeria is Home (2020). It has highlighted both close and distant reading approaches as suitable methods for engaging with this form of literature. Furthermore, the study has demonstrated Nigerian Twitterature’s role as an evolving literary practice on Twitter, contributing to both mainstream scholarship and social good.

The experimental analysis concludes by positioning Nigerian Twitterature as a platform for amplifying the voices of underrepresented writers, enabling them to engage creatively with global audiences. However, the rise of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) is increasingly automating the production of Twitterature, presenting new challenges for creative writers. What does the future hold for these writers? Will they become collaborators with AI, or will AI take over the writing, leaving humans to critique?

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Aciman, Alexander, and Emmett Rensin. 2009. Twitterature: The World’s Greatest Books in Twenty Tweets or Less. London: Penguin.Search in Google Scholar

Ajah, Richard O. 2022. “Multimodality, performance and technopoetics in Johanna Waliya’s Bilingual African digital poetry.” In Current Issues in Descriptive Linguistics and Digital Humanities, edited by Moses Effiong Ekpenyong, and Imelda Icheji Udoh, 669–85. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.10.1007/978-981-19-2932-8_45Search in Google Scholar

Bataillon, Stéphane. 2011. ‘Vous Avez Dit Twittérature, La Littérature Sur Twitter: Un État Des Lieux. Blog. 2011. https://www.stephanebataillon.com/en/twitterature-twitter-et-la-litterature/.Search in Google Scholar

Bootz, Philippe. 2016. “Une approche modélisée de la communication: application à la communication par des productions numériques.” HDR. Paris: Université Paris 8.Search in Google Scholar

Bouchardon, Serge, and Marine, Riguet. 2022. “Digital Textualities: Motile Writing.” In Exploring Contemporary Digital Poetics, edited by Mourad El Fali, 17–43. Fez: Laboratoire de Langue, Littérature, Imaginaire et Esthétique.Search in Google Scholar

Brou, Yah Edith. 2011. L’homme Aux Vers Noirs: Invente La Twittérature. Blog. Atelier Radio France Internationale (blog). 2011. https://atelier.rfi.fr.Search in Google Scholar

Cole, Teju. 2014a. Bring Back Our Girls? Microblog. Twitter. 2014. https://x.com/tejucole/timelines/462974573135536128.Search in Google Scholar

Cole, Teju. 2014b. Collection/Twitter. Microblog. Twitter. 2014. https://x.com/tejucole/timelines/462974573135536128.Search in Google Scholar

Dauda, Hafsat. 2020. Stories By I sur Twitter. Twitter. 2020. https://x.com/HafsahDauda/status/1313105805147807745.Search in Google Scholar

Delsart, Éloïse. 2018. “La Littérature á l’épreuve Du Numérique: Naissance de La Twittérature.” In Romanica, Vol. 30, 205–11. Limoges: Université de Limoges.Search in Google Scholar

Engberg, Maria. 2007. “Born digital: writing poetry in the age of new media.” PhD Thesis, Engelska institutionen.Search in Google Scholar

Ensslin, Astrid. 2007. Canonizing Hypertext: Explorations and Constructions. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Gere, Charlie. 2008. Digital Culture, 2nd ed. London: Reaktion Books.Search in Google Scholar

Grigar, Dene. 2016. “The 24–Hr. Micro–Elit Project. Social Media Narrative: Issues in Contemporary Practice.” Online Symposium. Facebook: The Rutgers Camden Digital Studies Center.Search in Google Scholar

Hébert, Louis. 2019. An Introduction to Applied Semiotics: Tools for Text and Image Analysis. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429329807Search in Google Scholar

Moisan, Mylène. 2012. La Twittérature, Cet Art Médiéval…. Blog. LeSoleil Numérique. 2012. https://www.lesoleil.com/5098da2d2185337385233a11ec61a7ed.Search in Google Scholar

@NigeriaPoetry. 2020. Poetry House Nigeria (@NigeriaPoetry)/Twitter. Twitter. 2020. https://x.com/NigeriaPoetry.Search in Google Scholar

Nzuanke, Samson, and Angela Ajimase. 2014. “Youth Language as a Transnational Phenomenon: The Case of French in Nigeria.” LWATI: A Journal of Contemporary Research 11 (4): 87–110.Search in Google Scholar

Pequeño, IV, and Antonio. 2024. X Usage Dropped 30% In Last Year, Study Says. Web. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/antoniopequenoiv/2024/03/06/usage-of-elon-musks-x-dropped-30percent-in-the-last-year-study-suggests/.Search in Google Scholar

Pisarski, Mariusz. 2017. “Digital Postmodernism: From Hypertexts to Twitterature and Bots.” World Literature Studies 9 (3): 41–53.Search in Google Scholar

Poetry for Nigeria, by Nigerians. 2020. Poetry for Nigeria, by Nigerians. Twitter. 2020. https://x.com/NigerianPoetry.Search in Google Scholar

Raguseo, Carla. 2010. “Twitter Fiction: Social Networking and Microfiction in 140 Characters.” The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language 13 (4). https://tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume13/ej52/ej52int/.Search in Google Scholar

Rucar, Yan. 2015. La Littérature Électronique : Une Traversée Entre Les Signes. Espace Littéraire. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal.10.4000/books.pum.2483Search in Google Scholar

Stokel-Walker, Chris. 2021. TikTok Boom: China’s Dynamite App and the Superpower Race for Social Media. Canbury: Canbury Press.Search in Google Scholar

Suleiman, Abdulfatai. 2019. #EndSARS BOT (@endsarsbot_)/Twitter. Microblog. Twitter. https://x.com/endsarsbot_.Search in Google Scholar

Waliya, Yohanna Joseph. 2020. ‘Digital Activism & “Botification” of Janusz Korczak’s Concepts in “Twitterature”’. In What Would Korczak Do? Reflections on Education, Well-Being and Children’s Rights in the Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic, 21–40. UNESCO Janusz Korczak Book Series. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej.Search in Google Scholar

Waliya, Yohanna Joseph. 2022. “Twittérature: lecture symétrique du Twitterbot-théâtre.” In Exploring Contemporary Digital Poetics, 217–45. Fez: Laboratoire de Langue, Littérature, Imaginaire et Esthétique.Search in Google Scholar

Waliya, Yohanna Joseph. 2023a. “Twittérature: Analyse Technodiscursive de La Twitterbot Poésie de Leonardo Flores.” Master thesis. Zaria: Ahmadu Bello University.Search in Google Scholar

Waliya, Yohanna Joseph. 2023b. “African Literature on MAELD and ADELD Platforms: Grafting the Buds of a Nascent E-Literature.” Afrique(s) En Mouvement N° 7 (1): 55–64. https://doi.org/10.3917/aem.007.0055.Search in Google Scholar

Walsh, Brandon, and Sarah Horowitz. 2016. Introduction to Text Analysis: A Coursebook. Blog. Brandon Walsh. https://walshbr.com/blog/text-analysis-coursebook/.Search in Google Scholar

X. 2024. “Grok.” X (formerly Twitter), https://x.com/i/premium_sign_up (Accessed 27 September 2024).Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Chongqing University, China

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Research Articles

- The Semiotics of Latency: Deciphering the Invisible Patterns of the New Digital World

- Everyone Leaves a Trace: Exploring Transcriptions of Medieval Manuscripts with Computational Methods

- Friend or Foe? A Mixed-Methods Study on the Impact of Digital Device Use on Chinese–Canadian Children’s Heritage Language Learning

- OCR Approaches for Humanities: Applications of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning on Transcription and Transliteration of Historical Documents

- Review Article

- Applying Topic Modeling to Literary Analysis: A Review

- Research Articles

- From Literature 2.0 to Twitterature or Xerature: The Birth and Canonicity of Nigerian Xerature

- Understanding CFL Learners’ Perceptions of ChatGPT for L2 Chinese Learning: A Technology Acceptance Perspective

- Brief Report

- Waiting for the Perfect Time: Perfectionistic Concerns Predict the Interpretation of Ambiguous Utterances About Time

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Research Articles

- The Semiotics of Latency: Deciphering the Invisible Patterns of the New Digital World

- Everyone Leaves a Trace: Exploring Transcriptions of Medieval Manuscripts with Computational Methods

- Friend or Foe? A Mixed-Methods Study on the Impact of Digital Device Use on Chinese–Canadian Children’s Heritage Language Learning

- OCR Approaches for Humanities: Applications of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning on Transcription and Transliteration of Historical Documents

- Review Article

- Applying Topic Modeling to Literary Analysis: A Review

- Research Articles

- From Literature 2.0 to Twitterature or Xerature: The Birth and Canonicity of Nigerian Xerature

- Understanding CFL Learners’ Perceptions of ChatGPT for L2 Chinese Learning: A Technology Acceptance Perspective

- Brief Report

- Waiting for the Perfect Time: Perfectionistic Concerns Predict the Interpretation of Ambiguous Utterances About Time