Abstract

The paper is concerned with problems in steganography on the detection of embeddings and statistical estimation of positions at which message bits are embedded. Binary stationary Markov chains with known or unknown matrices of transition probabilities are used as mathematical models of cover sequences (container hles). Based on the runs statistics and the likelihood ratio statistic, statistical tests are constructed for detecting the presence of embeddings. For a family of contiguous alternatives, the asymptotic power of statistical tests based on the runs statistics is found. An algorithm of polynomial complexity is developed for the statistical estimation of positions with embedded bits. Results of computer experiments are presented.

1 Introduction

The paper is concerned with a topical problem in steganographic information security—this is the problem of embedding detection, that is of the construction of statistical tests for the existence of embeddings and of statistical estimates of positions (points) of embeddings.

The problem of detection of embeddings was studied in [1, 2, 3, 4] under the assumption that the probabilistic model of a cover sequence is completely known. So, in [1] statistical tests were constructed for the embedding existence in the case when the initial (cover) sequence is modeled by a Bernoulli scheme of independent trials; it was also shown that the embedding detection is impossible if the fraction of the embeddings tends to 0 as the length of the initial sequence tends to to. A similar fact was proved in [3]. In [2] a most powerful statistical test for the embedding existence was constructed for the model based on a Bernoulli scheme of independent trials, and statistical estimates of the fraction of embeddings were put forward. Statistical estimates of the model parameters of the embedding in a binary Markov chain were constructed and examined in [5]; they allow to make preliminary conclusions on the fraction of embeddings. It is worth mentioning that the majority of studies on the detection of embeddings are based on empirical characteristics of sequences, which involve methods of discriminant analysis for testing the embedding existence. We also note that the above problems of recognition of embeddings are close to those on the detection of deviations of output sequences of cryptographic generators from uniformly distributed random sequences [6].

Our purpose in this paper is to continue the studies initiated in [5]: we construct and analyse statistical tests for the embedding existence, and to develop algorithms for the statistical estimation of embeddings points.

The paper is organized as follows. In § 2 we describe the mathematical (q, r)-block model of embedding in a binary Markov chain. In §3 we construct statistical tests for the embedding existence based on the runs statistics and on the short runs statistics, and in § 4 we consider tests based on the likelihood ratio statistics. In §5, we put forward an algorithm of polynomial complexity for statistical estimation. The results of numerical experiments are given in § 6.

2 Mathematical model of embedding

We define the generalized (q, r)-block model of embedding, a particular case of which was proposed by the authors of the present paper in [5]. Throughout, (Ώ, F, P) is the underlying probability space, V = {0,1} is the binary alphabet, VT is the space of binary T-dimensional vectors, O (■) is the ‘big O’ notation introduced by Landau, N is the set of natural numbers, I{A} is the indicator of an event A, ut2t1 =(ut1,..., ut2 ) ∈ Vt2-tl+1(t1, t2 ∈ ℕ, t1 < t2) is a binary string of t2 -t1 + 1 successive symbols of some sequence {ut : t ∈ ℕ}, w(•) is the Hamming weight, 𝔏{ξ} is the probability distribution of a random variable ξ, Β(θ) denotes the Bernoulli distribution with parameter θ ∈ [0, 1]: Ρ{ξ = 1} = 1 - Ρ{ξ = 0} = θ, Φ(•) is the distribution function for the standard normal law 𝒩(0, 1).

According to [5], an adequate model of the cover sequence for embedding a message is a binary sequence xT1= (x1, x2, ..., xT) ∈ VT, xt ∈ V, t = 1, ..., T, of length T, which is a homogeneous hrst-order binary Markov chain with symmetric matrix of one-step transition probabilities P:

Here, ε is the parameter of the model: the case ε = 0 corresponds to a scheme of independent trials which was examined in [1]. The case ε > 0 takes into account an attraction-type dependence, and the ε < 0, a repulsiontype dependence. We note that the Markov chain (1) satishes the ergodicity conditions [7] and has the uniform stationary distribution (1/2, 1/2). In what follows, we shall assume that the Markov chain (1) is stationary, and so its initial probability distribution agrees with the uniform distribution.

In practical applications [5] a message is subject to a cryptographic transformation before being embedded in the cover sequence, and hence we assume in what follows that a message ξ1M = (ξ1, ..., ξM) ∈ VM, M < T, is a sequence of M independent Bernoulli random variables:

The stego-key γ1T = (γ1 ..., γT) ∈ VT specihes the points (time instants) at which the message bits ξΜ1 are embedded in the sequence x1T. We introduce a special (q, r)-block model of the stego-key γT1(q, r ∈ ℕ, r < q), assuming that the length of the sequence xT1 is a multiple of q: T = Kq.

Let ζk ∈ V, 𝔏{ζk} = 𝔅(δ), k = 1, ..., K, be auxiliary independent random variables, which govern the choice of the blocks {x(k) = xkq(k-1)q+1} for embedding the message ξM1: if ζk = 1, then r successive bits of the message are embedded in r randomly chosen bits of the block x(k) if ζk = 0 then no embedding in the block x(k) is performed; G(q, r) = {g(q, r)1, ..., g(q, r)Crq} = {uq1 ∈ Vq : w(uq1) = r} is the set consisting of

Cqr lexicographically ordered binary vectors of length q equipped with the Hamming weight r; g1, g2, ... are independent random variables, gk has uniform probability distribution on the set {1, ..., Crq},

In the (q, r)-block model of embedding, the sequence γT1 consists of blocks of length q: γ(1) = γq1, γ(2) = γ2qq + 1, . . ., γ(K) = γKq(K - 1)q + 1,

the parameter δ characterizes the fraction of embeddings. We note that for the (q, r)-block model of embedding the maximum capacity for the stego system is Tr/q bits, while the cardinality of the set of all possible stego-keys

is |Γ(q, r)| = (1 + Crq)T/q. In the case q = r = 1, we have the classical model [5] of a bit-wise embedding, |Γ(1, 1)| = 2T.

For the most commonly encountered in steganography methods of embedding (the ‘LSB replacement’ and the ‘± embedding’ [8]) the random stego-sequence YT1 = (Y1, ..., YT) is generated by the sequences {xt}, {ξt}, {γt} via the function transform

where τt = ∑tj = 1 γj. The sequences {xt}, {ξt}, {γt} are assumed to be jointly independent.

We note that for r = 1 the model presented here coincides with the q-block model considered in [5].

From the practical point of view, the case with θ0 = θ1 = 1/2 in (2), which presents the greatest challenge for embedding detection, is the most noteworthy in the framework of the Markov model of embedding (1)-(4). In this case the one-dimensional distribution of probabilities is not distorted for an embedding in (4),

Another justihcation of the relevance of the case considered in the present paper is the practical utilization of preliminary cryptographic transformation of a message that removes the nonuniformity in the probability distribution of symbols.

3 Embedding detection based on the runs statistics

3.1 Using the total number of runs statistics

We introduce two hypotheses concerning the fraction δ ∈ [0, 1] of embeddings:

The hypothesis H0 means that there are no embeddings and the stego-sequence YT1 agrees with the cover sequence xT1. The composite alternative H1 means there exist embeddings with some unknown fraction δ > 0. If the parameter of the cover sequence ε is known, then the null hypothesis, which will be denoted by H0, ε, is simple; otherwise, H0 is also a composite hypothesis. If the hypothesis H0 holds, then the probability measure P will be denoted by P0, otherwise, by Pδ. One similarly denotes the moments of random variables. The distributions P0 and Pδ were found in [5].

Lemma 1. Under the hypothesisH0, ε, the probability distribution of the stego-sequenceYT1 is as follows

where

is the minimal sufficient statistics withH0, ε.

The statistics BT is called the ‘runs test’ in [9] (it means the total number of runs). By virtue of (1), under the hypothesis H0 the sequence of indicators I{Yt ⊗ Yt+1 = 1} consists of independent random variables with Bernoulli distribution 𝔅(2-1(1 - ε)). Using the exact binomial probability distribution of the statistics BT with the known value of ε, one may construct a randomized statistical test for the embedding existence with the given probability of the hrst kind error α, . However, for practical purposes, it is more convenient to use its asymptotic variant as T → ∞, which is given by the critical region

where tα is the α-quantile of the standard normal distribution: Φ(tα) = α.

Theorem 1. Let the model of embedding (4) hold. Then asT → ∞ the asymptotic size of test (7) for the hypothesesH0, ε, H1based on the total number of runs statisticsBTcoincides with a preassigned significance levelα ∈ (0, 1). The asymptotic expression for the power of this test in the case of the(1, 1)-model of embedding and of the family of simple contiguous alternativesH1, δ : {δ = ρ/Tβ}, β > 0, is as follows:

Proof. Under the hypothesis H0, the De Moivre-Laplace limit theorem implies that

Hence, using (9) we have, as T → ∞,

In the case q = r = 1, under the alternative H1, it follows from (1), (2), (4), (5) that the initial hrst moment of the random variable BT is equal to

Using similar arguments, we calculate the initial second moment under the alternative H

For the variance, we have

By the construction (4) the random sequence {Yt} satishes the strong mixing property [10, 11], and hence the central limit theorem for weakly dependent random variables holds,

In the case ε > 0, we take into account (10) and substitute δ = ρ/Tβ as T → ∞ into the expression for the power. As a result, we have

Analyzing various values of β in this expression, we arrive at (8). The case ε < 0 is dealt with similarly. □

3.2 Using the short runs statistics

Let us construct the sequence of indicators of sign changes in the sequence Y1, ..., YT ∈ VT:

Next, we define the set of patterns in sequence (11):

here 𝔟τ is the chain of τ successive 0’s bounded from the left and right by 1’s. Such patterns specify series of 0’s and 1’s of length τ + 1 in the stego-sequence {Yt}. Further, we consider the disjoint random events ℭτ, τ ∈ ℕ ∪ {0}:

Lemma 2. Let the model of embedding (4) hold, q = r = 1. Then under the alternativeH1 the probability distribution of the random events ℭτ is given by

where 𝔞τ(δ, ε) → 0 as δ → 0, |ε| < 1.

Proof. Using the law of total probability for the model of embedding under consideration we hnd that

Theorem 2. Under the hypotheses of Lemma 2, the function 𝔞τ(δ, ε) has the asymptotic expansion

Proof. We partition the set 𝔘τ+2, 1 = {uτ+21 = (u1, ..., uτ+2) ∈ Vτ+2: w(uτ+21) = 1}, |𝔘| = τ + 2, of binary vectors of length τ + 2, τ ≤ 3, with unit Hamming weight into three disjoint subsets:

Arguing as in the proof of Lemma 2, we have

Let us consider the case τ ≥ 2. The subset 𝔘(j)τ+2, 1, j ∈ {0, 1, 2}, contains sequences uτ+21 ∈ 𝔘τ+2, 1 such that the events ℭτ ∩ {γt+τ+lt = uτ+21} are equiprobable under the alternative Hl:

Now (13) with τ ≥ 2 follows by substitution of (15) into (14). The case τ < 2 in (13) is considered similarly. □

Theorem 3. Under the hypotheses of Lemma 2, the function 𝔞τ(δ, ε) has the second-order asymptotic expansion

where

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 2, the set of stego-keys 𝔘τ+2, 2 being split into classes of equiprobable events.

From Theorems 2, 3 it follows that under the alternative Hl (existence of embeddings) the probability distribution of the total number of runs of a given length differs from that distribution under the hypothesis H0. In particular, for ε > 0 the probabilities of the events ℭ0, ℭ1, ℭ2 increase as δ increases from 0 to 1, whereas for τ > τε = 2 + ε(3 + ε)(1 - ε)-1 the probability Pδ{ℭτ} decreases with the increasing of δ. This being so, we consider the statistics

where the statistics 𝓑T, 2 is the total number of series of 0’s and of 1’s of length 1 in the sequence {yt}, and the statistics 𝓑T, 1 is related to the total number of runs statistics BT by the relation 𝓑T, 1 = BT - zT-l - 1.

Using Theorem 1 from [5] one may show that under the alternative Hl the initial ftrst-order moments of the bivariate statistics (𝓑T, 1, 𝓑T, 2), as given by (17), read as

From (18) it is seen that for ε > 0 the mean number of sign changes or of two neighbouring sign changes is larger when the embeddings exist than in the opposite case.

Theorem 4. Let the model of embedding (4) holds. Then, asT → ∞, the statistical test for the hypothesesH0, ε, H1of the asymptotic significance level α ∈ (0, 1) based on the bivariate statistics (17) is given by the critical region

where the region 𝓓1, 2is as follows

that is,

Proof. Using the fact that under the hypothesis H0, ε the random variables {zt} are independent and have the Bernoulli distribution 𝔅(2-1(1 - ε)), and since the random variables zt zt+1 and zszs+1 are independent if |t - s| > 1, we hnd that

Next, since the sequence of pairs (Zt, ZtZt+1) ∈ V2 is 1-dependent, it follows that as T → ∞ the random vector

In Fig. 1 the region 𝓓1, 2 for the case ε > 0 is marked by the ‘+’ sign. Such a form of the domain follows from the asymptotical normality of the bivariate statistics (𝓑T, 1, 𝓑T, 2) and from expressions (18). To calculate the probability of the hrst kind error, we use the linear transform of the region 𝓓1, 2. We apply the matrix Σ- 1/20 to the unit vectors (1, 0), (0, 1) ∈ 𝓡2 and construct the Gram matrix:

![Figure 1 The region 𝓓1, 2 for ε > 0 and the scattering ellipses for 5 e [0, 1].](/document/doi/10.1515/dma-2016-0002/asset/graphic/j_dma-2016-0002_fig_001.jpg)

The region 𝓓1, 2 for ε > 0 and the scattering ellipses for 5 e [0, 1].

The angle φ between the vectors ul and u2 is expressed in terms of the coefficient of correlation:

Because of the joint asymptotic normality of statistics (17), the random variable

has an asymptotically exponential distribution with the parameter 1/2 as T → ∞. Hence, from the equation

we find

Lemma 3. Under the (1, 1)-model of embedding and the alternativeHlthe random variableszt, zsare independent if |t - s| ≥ 2, the random variableszt, zszs+lare independent if |t - s| ≥ 2, and the random variables ztzt + 1, zszs + 1 are independent if |t - s| ≥ 3.

Proof. Let us consider the random variables zt, zt+k, k ≥ 2, and find the expectation Eδ{ztzt+k}, k ≥ 2:

Since the random variables zt, zt+k are binary and since cov, {zt, zt+k} = 0 for k ≥ 2, then such variables are independent. A similar argument shows that the random variables zt, zszs+l are independent if |t - s| ≥ 2 and that the random variables ztzt+l, zszs+l are independent if |t - s| ≥ 3. □

Now we will employ Lemma 3 to hnd asymptotic expressions for the hrst and second moments of the bivariate statistics (𝓑T, 1, 𝓑T, 2) under the alternative H1, δ. The hrst-order moments were found in (18). In the course of the proof of Theorem 1 it was shown that

In view of Lemma 3 we have, as T → ∞,

Using the law of total probability, we hnd, for the model of embedding (1, 1),

We thus have

Using Lemma 3 as T → ∞ we hnd the variance DÒ{Bf2}:

A similar argument as for Pδ {ztzt+1zt+2 = 1} shows that

As a result, we have

Using the strong mixing property [10], one may show that under the alternative H1, δ the distribution of the random vector

as T → ∞ is asymptotically normal 𝓝2((0, 0)′, Σ1) with zero mean and covariance matrix Σ1 = (σ1, ij), i, j = 1, 2, where

Unfortunately, for the test (19) based on the short runs statistics we have not succeed to obtain an explicit expression for the power and to examine it, because the covariance matrix depends on δ. This dependence is illustrated in Fig. 1, which depicts the scattering ellipses (corresponding to the asymptotic matrices) when the parameter δ is increasing from 0 to 1. The following important property of the asymptotically normal distribution of the random vector (17) under the alternative H1, δ is worth pointing out: with 5 changing from 0 to 1 the centre of the asymptotically normal distribution of the bivariate statistics (𝓑T, i, 𝓑T, 2) always lies on the line

Taking into account the property (22), we construct a statistical test for the hypotheses H0, ε, H1 based on the statistics obtained as the orthogonal projection of the statistics (𝓑T, i, 𝓑T, 2) on the line (22). Such a test for ε > 0 is given by the critical region

Theorem 5. Let the model of embedding (4) hold and let ε > 0. Then, asT → ∞, the asymptotic size of test (23) for the hypothesesH0, ε, H1based on the projection of the short runs statistics

coincides with the significance level α ∈ (0, 1). The asymptotic power of this test for the (1, 1)-model of embedding and for the family of contiguous alternatives

Proof. The angle between the line (22) and the b2-axis is φ = arctan (1/2(2 - ε)), and hence, the orthogonal projection of the point (𝓑T, i, 𝓑T, 2) on this line is given by

Multiplying this expression by cosec ϕ, we get the random variable 𝔥, which, according to (21), has the asymptotically normal distribution 𝓝1(0, d#x1D525;) under the hypothesis H0, ε. Hence, P0{X𝔥 +1 α} → α as T → ∞.

Let us hnd the power of test (23) as T → ∞ for contiguous alternatives of the form indicated in the theorem. We have

Substituting

4 Embedding detection on the basis of the likelihood ratio statistics

Let us now consider the case when the parameter ε in (1) is unknown and separated from the zero: ε0 ≤ |ε| < 1, where ε0 > 0 is the known boundary value.

We construct the likelihood function for the observed stego-sequence yT1 ∈ V_T. Following [5], we partition the set Vt of binary t-dimensional vectors into t + 1 disjoint subsets,

where

The partition (26), (27) generates the partition of all possible trajectories of fragments of the key sequence γt1 = ut1 ∈ Vt.

Lemma 4. The likelihood function for the (q, r)-block model of embedding is as follows

where

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 5 for the q-block model of embedding in [5].

To test the hypotheses H0, H1 on the existence of embeddings we now construct the statistical likelihood ratio test [12]. The statistics λT of this test for the hypotheses H0, H1 takes the form

where

Besides, according to [5],

The statistical test of size α ∈ (0, 1) based on the statistics λT is defined by the critical region

where λα > 0 is the solution of the equation

Here, F0(ε, T, λT) is the distribution function of the statistics (28) under the null hypothesis H0.

To estimate the value of λα satisfying (30), we use the Monte Carlo method: we model M0 samples of a Markov chain of length T with the parameter ε0. For each sample we calculate the value of the statistics by (28). Let λ(1), ..., λ(M0) be the calculated values. Then λα can be estimated by the sample quantile of level 1 - α:

the accuracy of this estimate increases with M0 → ∞. So, the statistical tests (29) for the embedding existence assumes the formml:

the hypothesis H0 (respectively, H1) is adopted if p ≥ α (p < α),

The available asymptotic properties of the likelihood ratio test [12, 13] may be used under the regularity conditions [12] guaranteeing the existence, uniqueness, and asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters ε and δ.

Theorem 6. Under the model of embedding (4), asT → ∞ the test of asymptotic significance level α ∈ (0, 1) based on the likelihood ratio statistics for the composite null hypothesis is given by the critical region (29) with the threshold λα = χ21-α, 1; that is,

This test is consistent under fixed alternatives δ = δ1 > 0:

The proof follows the argument of [13] with the use of the central limit theorem for weakly dependent random variables [10].

5 5 Statistical estimation of embeddings points

If the alternative H1 is adopted, then there arises the problem of estimation of points of embeddings—these being the time instants t ∈ {1, ..., T} at which in accordance with (4) a bit of the sequence {xt} is replaced by a bit of the hidden message {𝔏t}.

Theorem 7. LetγT1 = (γ1, ..., γT) ∈ Γ(q, r)be the key sequence corresponding to the(q, r)-model of embedding, yT1 ∈ VT be the observed stego-sequence,

is attained for the statistics

which maximizes the a posteriori probability of the stego-key. The minimum of error probability is as follows:

Proof. We choose an arbitrary statistics

and calculate for it the corresponding error probability for the estimate of the true stego-key error probability for the estimate of the true stego-key γT1 ∈ Γ(q, r):

After equivalent transformations, using (34) and the rlaw of total probability, we hnd that

Minimizing this expression in f(•) and using (34), we obtain the optimal function f(•) in the form

which agrees with the statistics (32).

Substituting (36) into (35), we get (33). □

The estimate (32) by the maximum a posteriori probability criterion admits the following equivalent representation, which is convenient for its evaluation:

The solution of problem (37) for the (q, r)-block model of embedding by the exhaustive search has a computational complexity

We set

The initial values of 𝔰t(u1, ..., ut) with t = 1, ..., c are as follows:

here, φt(˙) is the same as in Lemma 4.

Theorem 8. Under the(q, r)-block model of embedding (4), q > r, the recurrence relation

holds for 𝔰t(ut - c, ..., ut) with t > c, where

Proof. In the case q ≤ 2r + 2 we have

The case q > 2r + 2 is dealt with similarly. Combining these cases, we arrive at (39). □

Corollary 1. Under the hypotheses of Theorem 8 the estimate

Proof. The estimate

The algorithm of the estimation of embedding points (the forward run (38), (39), the backward run (40)) has a numerical complexity

Having estimate the embedding points γT1 by (40), one can construct an estimate ξ^ of the message itself:

6 Results of computer experiments

We give the results of three series of computer experiments using simulated data.

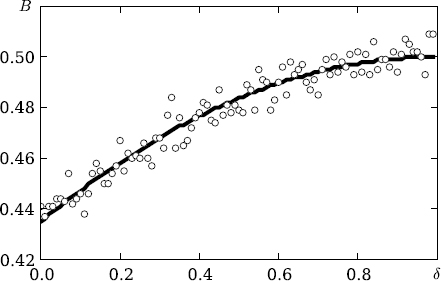

Series 1. The initial Markov sequence (1) of length T = 104 with the parameter ε = 0.13 was simulated. For q = r = 1, the key Bernoulli sequence was simulated using (3) with various values of the parameter δ ∈ [0, 1], the stego-sequence yT1 was constructed by (4). Figure 2 depicts the total number of runs statistics BT versus the fraction of embeddings δ. Circles mark the values of the statistics

The total number of runs statistics BT versus the fraction of embeddings δ

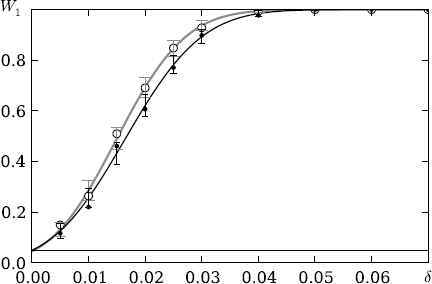

Series 2. As in Series 1, the Monte Carlo method with the number of replications M1 = 28 was used to construct estimates of powers for the tests (7), (23) under the hypotheses H0, ε, H1 with known cover sequence parameter ε = 0.48; the length T = 213, the signihcance level α = 0.05, and the fraction of embeddings δ ∈ {0.005, 0.01, 0.015, 0.02, 0.025, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, 0.07}.

Powers of the tests XB+1α, X𝔥 +1α versus the fraction of embeddings δ.

Figure 3 shows graphically the powers of the statistical tests (7), (23) versus the fraction of the embeddings δ. The black solid line depicts the theoretical curve of the test power (7) based on the total number of runs statistics, the grey solid line shows the theoretical curve of the test power (23) based on the projection of short runs statistics, the black circles correspond to estimates of the powers of test (7), the white circles show estimates of the powers of test (23). The 95%-conhdence intervals for the powers of tests (7) and (23) are shown in grey and black, respectively.

It is seen from the graph that test (23) based on the short runs statistics is more powerful than test (7) based on the total number of runs statistics. Numerical experiments show that for small values ε the powers of tests (7) and (23) are practically the same.

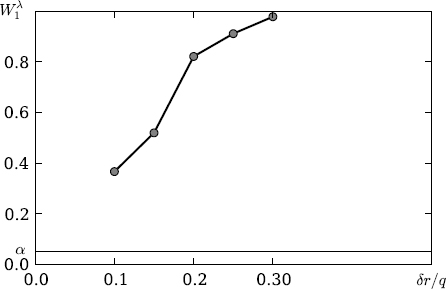

Power of the test 𝔥λ1α versus the fraction of embeddings δr/q..

Series 3. For the block model of embedding with q = 2, r = 1, the Monte Carlo method was used to hnd the threshold estimates

Computer experiments demonstrate the efficiency of the statistical test thus constructed for the embedding detection and the agreement between theoretical and experimental results.

In conclusion, we note that embeddings may also be detected using small-parametric models of highorder Markov chains [15].

Note: Originally published in Diskretnaya Matematika (2015) 27, No3, 123–144 (in Russian).

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to A. M. Zubkov for suggesting to study the runs statistics for the embedding detection and to the referees for comments and advices.

References

1 Ponomarev K. I., “A parametric model of embedding and its statistical analysis”, Discrete Math. Appl, 19:6 (2009), 587-596.10.1515/DMA.2009.039Search in Google Scholar

2 Ponomarev K. I., “On one statistical model of steganography”, Discrete Math. Appl., 19:3 (2009), 329-336.10.1515/DMA.2009.021Search in Google Scholar

3 Ker A., “A capacity result for batch steganography”, IEEE Signal Process. Lett., 14:8 (2007), 525-528.10.1109/LSP.2006.891319Search in Google Scholar

4 Shoytov A.M., “On the fact of detecting the noise in hnite Markov chain with an unknown transition probability matrix”, Prikl. Diskr. Mat., 2010, Na Supplement Na 3, 44-45 (in Russian).Search in Google Scholar

5 Kharin Yu. S., Vecherko E. V., “Statistical estimation of parameters for binary Markov chain models with embeddings”, Discrete Math. Appl., 23:2 (2013), 153-169.10.1515/dma-2013-009Search in Google Scholar

6 Zubkov A. M., “Pseudorandom number generatgors and its applications”, Proc. II Int. Sci. Conf. “Mathematics and security of information technologies”, 2003, 200-206.Search in Google Scholar

7 Kemeny J. G., Snell J. L., Finite Markov chains, Van Nostrand, 1960.Search in Google Scholar

8 Ivanov V.A., “Models of inclusions into homogeneous random sequences”, Tr. Diskr. Mat., 10 (2008), 18-34 (in Russian).Search in Google Scholar

9 A statistical test suite for random and pseudorandom number generators for cryptographic applications: NIST Special Publication 800-22 Rev. 1a., Nat. Inst. Stand. Technol., 2010.Search in Google Scholar

10 Doukhan P., Mixing: properties and examples, Springer-Verlag, 1994.10.1007/978-1-4612-2642-0Search in Google Scholar

11 Kharin Yu. S., Voloshko V. A., “Robust estimation of AR coefficients under simultaneously influencing outliers and missing values”, J. Statist. Plan. Infer., 141:9 (2011), 3276-3288.10.1016/j.jspi.2011.04.015Search in Google Scholar

12 Ivchenko G. I., Medvedev Yu. I., Mathematical statistics, Vysshaya shkola, Moscow, 1984 (in Russian).Search in Google Scholar

13 Wald A., “Tests of statistical hypotheses concerning several parameters when the number of observations is large”, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 54:3 (1943), 426-482.10.1090/S0002-9947-1943-0012401-3Search in Google Scholar

14 Rabiner L. R., “A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition”, Proc. IEEE, 77:2 (1989), 257-286.10.1016/B978-0-08-051584-7.50027-9Search in Google Scholar

15 Kharin Yu. S., Petlitskiy A. I., “A Markov chain of order s with r partial connections and statistical inference on its parameters”, Discrete Math. Appl., 17:3 (2007), 295-317.10.1515/dma.2007.026Search in Google Scholar

© 2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Article

- Frame classification of the reduced labeled blocks

- Article

- Detection of embeddings in binary Markov chains

- Article

- Circuit complexity of symmetric Boolean functions in antichain basis

- Article

- Functions without short implicents. Part I: lower estimates of weights

- Article

- Two-dimensional renewal theorems with weak moment conditions and critical Bellman – Harris branching processes

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Article

- Frame classification of the reduced labeled blocks

- Article

- Detection of embeddings in binary Markov chains

- Article

- Circuit complexity of symmetric Boolean functions in antichain basis

- Article

- Functions without short implicents. Part I: lower estimates of weights

- Article

- Two-dimensional renewal theorems with weak moment conditions and critical Bellman – Harris branching processes