Abstract

While verbs and argument structure constructions are essential for deriving sentence meaning, their roles in sentence processing remains less known. To address this issue, the present study explored how a verb’s lexical properties and the strength of verb–construction associations influence second language (L2) sentence processing. In two self-paced reading experiments, Korean-speaking learners of English and native English speakers read English argument structure constructions containing verbs with varying lexical properties and association strength. In both Experiment 1 (involving the prepositional dative construction) and Experiment 2 (involving the caused-motion construction), only the L2-English learners, and not the native speakers, spent more time integrating the target constructions with verbs of weaker associations than those with stronger associations. Furthermore, the learners exhibited greater difficulty with verb–construction integration when the verbs were less frequent and less concrete; L2 proficiency did not modulate these effects. Our findings support the constructionist approach, suggesting that both verbs and verb–construction associations play an instrumental role in sentence comprehension.

1 Introduction

The usage-based constructionist approach to language learning (Ellis et al. 2013; Goldberg 1995, 2006], 2019]) emphasizes the pivotal role of both verbs and argument structure constructions in the formulation of sentence meaning. According to this approach, language users derive information both from verbs, including lexico-semantic cues, predicate expectations, and valency, and from argument structure constructions (i.e., clause-level units carrying their own form and meaning, henceforth referred to as ‘constructions’) to construct linguistic representations in memory to arrive at the correct interpretation of a sentence (Bencini and Goldberg 2000; Goldberg 1995, 2013]; Johnson and Goldberg 2013; Kaschak and Glenberg 2000). Crucially, speakers do not integrate verbal and constructional information in an entirely arbitrary or innovative manner. Instead, they implicitly adhere to statistical constraints imposed on the frequencies of verbs, constructions, and their combinations (Ambridge et al. 2015; Ellis 2002; Robenalt and Goldberg 2015). For example, previous research suggests that English speakers are less likely to extend the use of a verb to a new construction (e.g., ?The magician disappeared the rabbit) if the verb is frequently attested in an alternative construction that conveys the same intended meaning (e.g., The magician made the rabbit disappear).

While the acquisition of statistical regularities associated with the integration of verbs and constructions has been extensively studied in first language (L1) acquisition (Ambridge et al. 2015; Boyd and Goldberg 2011; Robenalt and Goldberg 2015; Stefanowitsch 2011), it remains relatively less understood how second language (L2) learners use this information for sentence comprehension. Moreover, much of earlier work has focused on comprehenders’ detection of overgeneralization errors in offline tasks involving acceptability judgments (Ambridge et al. 2015; Robenalt and Goldberg 2015, 2016]; Tachihara and Goldberg 2020). Although acceptability judgment tasks provide insights into speakers’ explicit knowledge of verbs and constructions, they do not directly capture the real-time integration of these information sources during sentence comprehension. Given the frequently observed disparities between L2 learners’ explicit knowledge and their automatized knowledge (e.g., Jiang 2007), it is necessary to further investigate L2 learners’ real-time language processing abilities through online tasks. To address this gap, the current study aims to broaden the scope of previous research by examining L2 learners’ sensitivity to verbal and constructional information using online self-paced reading tasks.

Beyond statistical information, our study also examines how specific lexical properties of verbs influence L2 learners’ integration of verbs and constructions during real-time processing. Verbs possess various lexical properties such as frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness (Kyle and Crossley 2015). Frequency refers to how often a verb occurs in language use, while concreteness relates to how easily a verb can be perceived by the senses. Familiarity reflects how well a verb is known to learners, and meaningfulness pertains to the richness of a verb’s semantic associations. While previous studies have shown that verb frequency plays a significant role in L2 processing (e.g., Hopp 2017), the effects of other lexical attributes on L2 learners’ ability to combine verbs with constructions in sentence processing remain unclear.

Our primary objective is to explore whether L2 learners exhibit a reduced sensitivity to frequency-based information from verbs and constructions compared to native speakers. Specifically, we investigate the extent to which a verb’s lexical attributes, such as frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness, or the strength of verb–construction associations influence the integration of a verb and a construction by L2 learners during real-time processing. As will be discussed below, various theoretical perspectives offer different predictions regarding the impacts of a verb’s lexical properties and verb–construction associations on verb–construction integration during online processing. Some researchers advocate for a verb-centered perspective (Chomsky 1981; Healy and Miller 1970; Pinker 1989), emphasizing the primacy of verb information in deriving the meaning of a sentence, thereby influencing L2 sentence processing. In contrast, others place a great emphasis on the interplay between a verb and a construction in facilitating sentence comprehension (Ambridge et al. 2008; Bencini and Goldberg 2000; Goldberg 1995, 2013]). To assess these approaches, this study employs a series of experiments designed to test whether only verb-specific variables, or both verb-specific and association variables, significantly influence L2 learners’ integration processes. This analysis allows us to address the competing predictions put forth by the two perspectives, which are elaborated in the following section.

2 Roles of a verb and a construction in sentence comprehension

Among the various cues utilized during sentence comprehension, the main verb has long been recognized as a key contributor to sentence meaning. Verbs convey essential lexical information for constructing event representations and specifying the syntactic realization of its argument structures (Levin 1993; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 2005). Thus, verb information provides fundamental cues that enable comprehenders to establish a mental model of an event, incrementally integrate incoming materials, and even engage in predictive processing (Altmann and Kamide 1999). The special status of verbs has led many researchers to propose that verbs play a decisive role in determining the overall meaning of a sentence (Chomsky 1981; Healy and Miller 1970; Pinker 1989). This perspective, referred to as a verb-centered view, underscores the significance of verb information in clausal interpretation across various contexts, including online processing.

In contrast to the verb-centered view, the usage-based constructionist approach maintains that sentence meaning is not solely derived from the verb but from the integration between the verb and an argument structure construction (Bencini and Goldberg 2000; Goldberg 1995). For example, according to the constructionist approach, the meanings of the sentences in (1) stem from the lexical contribution of the verb kick and its combination with the respective argument structure constructions. Specifically, the transitive construction (1a) combines with the verb to denote a simple transitive action; the ditransitive construction (1b) conveys the transfer of an object; the caused-motion construction (1c) indicates a change of a theme in location; the resultative construction (1d) denotes a change in the state of a theme.

| Paul kicked the ball. (Transitive construction + kick) |

| Paul kicked me the ball. (Ditransitive construction + kick) |

| Paul kicked the ball into the hole. (Caused-motion construction + kick) |

| Paul kicked the ball flat. (Resultative construction + kick) |

The variation in meaning observed in sentences containing the same verb but with different argument structure configurations, as illustrated in (1), suggests that a verb alone may not fully determine the meaning of a sentence. Instead, the integration of information from both the verb and the construction is necessary to arrive at a complete understanding of a sentence (Goldberg 1995, 2013]).

A central concept relevant to the integration of verbs and constructions is Goldberg’s (1995) notion of fusion. Goldberg proposed that sentence meaning is constructed via the fusion of the roles provided by a verb and a construction. For instance, the sentence “Paul gave me a ball” derives its meaning through the combined contribution of the verb gave, which specifies the participant roles of giver (Paul), givee (me), and given (a ball), along with the ditransitive construction, which licenses the argument roles of agent, recipient, and patient. In this example, the verb’s participant roles coincide with the argument roles profiled by the construction, facilitating the fusion without conflict. However, there are cases where the verb’s participant roles alone may not suffice to fully convey the meaning of a sentence. As an illustration, the verb kick, which inherently involves only two participants roles of kicker and kickee, can appear in a resultative sentence such as “Paul kicked the ball flat”. In such instances, Goldberg (1995) posited that any role left unspecified by the verb (in this case, ‘flat’) is profiled instead by the argument structure construction. Consequently, although the verb kick profiles only kicker and kickee, it can be integrated with the resultative construction after the construction licenses an additional role of ‘resulting state’.

In line with the constructionist approach, ample evidence suggests that language users can understand and produce sentences with various types of verbs, including those lacking a certain argument role or those with little semantic content, with the help of constructional information (Ambridge et al. 2008; Goldwater and Markman 2009; Kaschak and Glenberg 2000). Moreover, English speakers draw upon constructional information to interpret sentences, sometimes independent of the lexical status of a verb within the sentence (Ahrens 1995; Ambridge et al. 2008; Bencini and Goldberg 2000). This concurrent utilization of verb and construction cues has also been observed in the domain of L2 comprehension and production. Numerous studies have demonstrated L2 learners’ facility of constructional knowledge in tasks such as sentence sorting, acceptability judgment, and sentence production (Ellis and Larsen–Freeman 2009; Gries and Wulff 2005; Kim and Ro 2024; Kim et al. 2023; Manzanares and López 2008). However, most previous research relies on offline tasks, which may induce participants’ metalinguistic judgments, or on written corpus data that lacks control for relevant features, rendering it difficult to identify specific factors influencing L2 learners’ use of verbal and constructional information. To more precisely assess L2 learners’ ability to utilize verbal and constructional information in sentence comprehension, it is necessary to systematically manipulate relevant cues in carefully designed tasks that probe learners’ moment-to-moment sentence processing.

In an attempt to contribute to the ongoing debate surrounding the verb-centered view versus the constructionist approach to L2 sentence processing, this study aims to test the modulating roles of a verb’s lexical properties and the association strength between a verb and a construction during sentence processing. To this end, we conducted online self-paced reading tasks in which we measured L2 learners’ reading times while they processed sentences that varied in verb frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness, as well as in the strength of verb–construction associations. To assess the effects of these factors, we teased apart the influences of verb lexical properties and verb–construction associations by manipulating these variables. Before presenting our experimental findings, we provide a concise overview of theoretical models of L2 processing, particularly regarding the integration of verbs and constructions, which enable the formulation of specific predictions for our study.

3 Theoretical approaches to L2 integration of verbs and constructions

Various theoretical models predict persistent difficulty in the L2 integration of verb and construction information. Some models expect L2 learners’ reduced ability of verb–construction integration mainly due to their inefficient retrieval of verb information. For instance, the Weaker Links hypothesis (Gollan et al. 2008) assumes that L2 learners experience greater difficulty with the retrieval of L2 words as a direct function of their weak and unstable lexical representations, primarily stemming from limited experience with an L2. Several studies have provided supporting evidence of this hypothesis by demonstrating that L2 learners are slower and less accurate than monolingual speakers in making lexical decisions (e.g., Lemhöfer et al. 2008) and retrieving word information for resolving structural ambiguities (e.g., Hopp 2017). Moreover, a delayed lexical retrieval in L2 learners is indicated by greater frequency effects in L2 processing: L2 speakers show slowdowns in processing lower-frequency versus higher-frequency words to a greater extent than L1 speakers (e.g., Gollan et al. 2011).

Slower lexical processing in L2 learners is also predicted by the Revised Hierarchical Model (Kroll and Stewart 1994), which proposes that word meanings in the L2 mental lexicon are more strongly linked to the L1 than L2 word forms. According to this model, L2 learners (and particularly those at lower proficiency levels) have difficulty with directly accessing meaning via an L2 word form, relying instead on the L1 translation equivalent to access meaning. As a consequence of this L1-mediated lexical access, the model predicts delayed and less automatized word processing in L2 learners since they continually experience interference from L1 words when attempting to access the semantic information of target words.

While the Weaker Links hypothesis and the Revised Hierarchical Model provide valuable insights into L2 lexical processing, they do not directly address verb–construction integration. However, their predictions regarding slower lexical retrieval in L2 learners provide a foundation for our research hypotheses. Building on these models, we hypothesize that delayed verbal processing in L2 learners may have cascading effects on the integration of verbal and constructional information. Relevant to this issue, recent studies demonstrate that L2 learners’ slower lexical access and retrieval may indeed lead to delayed or less robust integration of syntactic information in sentence processing. For instance, Hopp (2014) found that only L2 learners with fast lexical retrieval skills exhibited native-like patterns in resolving relative clause attachment ambiguity during online processing. Extending these findings to the issue of verb–construction integration, it is conceivable that a slower retrieval of a verb may potentially impede the integration between the verb and constructional information, particularly given the key role of a verb in shaping sentence meaning (Healy and Miller 1970; Pinker 1989).

In contrast to the predictions of these models, the constructionist approach posits that a verb is not the only factor at work. According to this perspective, the conjoined roles of a verb and a construction also influences L2 processing. The importance of the association between a verb and a construction has been extensively documented in both L1 (Akhtar 1999; Ninio 1999; Tomasello 2003) and L2 contexts (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009; Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2009; Kim and Rah 2019; Kim et al. 2020). In particular, research on L2 production has shown that the ability to coordinate verbal and constructional information serves as a reliable indicator of L2 development (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009; Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2009; Kyle and Crossley 2017). For example, Kyle and Crossley (2017) observed that essays with higher holistic scores contained sentences involving less frequent verb–construction combinations and stronger associations between them. These findings suggest that more proficient L2 writers can combine and use less frequent verbs with constructions in more conventional ways.

The systematic relationship between L2 learners’ language development and their ability to integrate verb–construction associations in production allows for distinct predictions regarding the real-time integration of verbal and constructional information during L2 sentence processing. The current study tested the validity of these predictions by measuring L2 learners’ reading times for integrating information from a verb and a construction while manipulating verb-related information and verb–construction association strength across two self-paced reading experiments. In Experiment 1, participants were presented with English prepositional dative sentences containing verbs with distinct association strength with the construction (e.g., The secretary sent/texted the schedule to the president). We investigated whether learners experienced processing difficulties depending on the verb–construction association strength (stronger versus weaker association) and the verb’s lexical properties (frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness) during the integration process. Building on the findings from Experiment 1, Experiment 2 expanded the construction type to include the caused-motion construction and incorporated verbs with varying degrees of association strength with the target construction. This study aimed to address the following research questions.

Do verb-related properties, verb–construction association strength, or both influence L2 learners’ real-time integration of a verb and the prepositional dative construction? (Experiment 1)

Do these factors influence L2 learners’ real-time integration of a verb and the caused-motion construction? (Experiment 2)

4 Experiment 1: English prepositional dative construction

4.1 Participants

The study involved 92 participants, comprising 28 adult native English speakers (NS group) and 64 adult Korean-speaking learners of English (NNS group). The NS group, serving as the control group, consisted of self-identified English speakers (males: 16, females: 12; mean age = 38, SD = 11.7). Participants in the NNS group (males: 47, females: 17, mean age = 22, SD = 4.0) were recruited from universities in South Korea who had learned English in an instructed setting. According to a language background questionnaire, L2 participants had their first exposure to English at the age of 8 (SD = 2.3) through a regular school curriculum. Their mean length of residence in English-speaking countries was 5 months (SD = 12.1).[1]

We utilized two independent measures to estimate the learners’ English proficiency: a written cloze test (Brown 1980) and self-rated English proficiency. In the cloze test, participants read three short passages and completed 50 blanks using appropriate words or phrases. The mean score for the L2 participants in the cloze test was 29 out of 50 (SD = 8.9), indicating proficiency equivalent to intermediate to advanced levels, as referenced in a previous study employing the same test (Grüter et al. 2017). Participants also provided self-ratings of their English proficiency on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) across four domains: listening, reading, speaking, and writing. The mean self-rated English proficiency across the four domains was 6.4 out of 10 (SD = 1.5). These proficiency measures from the cloze test and the overall self-rated English proficiency were converted to z-scores and then averaged to derive a combined proficiency score for each participant (Grüter et al. 2017). The composite proficiency score ranged from −2.5 to 1.8 (SD = 0.8). This score was included in the analysis model as a continuous variable to examine whether L2 proficiency influenced the learners’ integration of verbal and constructional information during online processing.

All participants received monetary compensation for their participation.

4.2 Materials

The stimuli consisted of 48 sentences employing the English prepositional dative construction. We chose this construction type due to its high frequency in the input and its compatibility with a wide range of verbs (Campbell and Tomasello 2001; Goldberg 2019). These sentences convey the meaning that an object is transferred (e.g., The secretary sent the schedule to the president) and can alternate to the double-object dative construction (e.g., The secretary sent the president the schedule).

The sentences were aligned across two conditions based on verb–construction association strength: stronger (k = 24) and weaker association (k = 24). For a detailed analysis of participants’ processing patterns, each sentence was presented in seven regions (Rs), as illustrated in (2). This segmentation facilitates precise measurement of processing times for specific sentence components (Just et al. 1982), particularly the post-verbal region (R3), thereby enabling the identification of potential processing difficulties associated with varying strengths of verb–construction associations in this region.

| Stronger association condition: |

| The secretary (R1) / sent (R2) / the schedule to the president (R3) / after (R4) / work (R5) / on (R6) / Tuesday (R7). |

| Weaker association condition: |

| The secretary (R1) / texted (R2) / the schedule to the president (R3) / after (R4) / work (R5) / on (R6) / Tuesday (R7). |

Sentences in both conditions were identical except for the verb type in R2. The stronger association condition included verbs that are more likely to occur in the dative construction (e.g., send) compared to those in the weaker association condition (e.g., text). The association conditions were determined based on statistical biases observed in previous studies regarding the verbs’ occurrence in the dative construction (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009; Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2009; Gries and Stefanowitsch 2004; Levin 1993). To quantify the strength of verb–construction associations and ensure that verbs in the two conditions significantly differed in association strength, we conducted a collexeme analysis (Gries and Stefanowitsch 2004). This analysis measures the probability of a verb occurring in the target construction based on the frequency of their co-occurrence. The degree of association was quantified using a delta P value, calculating by subtracting the probability of the dative construction occurring as an outcome with any other verb as the cue from the probability of a particular construction as an outcome given a particular verb cue (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009).[2] This collexeme strength was computed for each stimulus using TAASSC (Kyle 2016), which utilizes frequency information from the academic section of the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies 2010). An independent sample t-test confirmed that the mean delta P value was significantly higher for the stronger association condition compared to the weaker association condition, t(46) = 2.136, p = 0.038, Cohen’s d = 0.570, indicating that verbs in the stronger association condition were more strongly associated with the target construction than those in the weaker association condition.

We also measured lexical properties of each verb in the stimuli, including verb frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness, which have been identified as significant indicators of L2 lexical development (e.g., Kyle and Crossley 2015). The inclusion of these variables builds on the reasoning that lower values on these properties may make it more challenging to retrieve the verb’s lexical information. Verb frequency was determined using the CELEX lexical database (Baayen et al. 1996). Concreteness (i.e., how much concrete concepts a word contains), familiarity (i.e., how familiar a word is), and meaningfulness (i.e., how many associative concepts a word shares with other words) were calculated based on ratings provided by native English speakers from the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Wilson 1988). Descriptive statistics of each property’s values are presented in Table 1. These values were entered into the analysis model as continuous variables to investigate whether the verb’s retrieval difficulty associated with these properties modulates L2 learners’ verb–construction integration.

Lexical information of the verbs used in Experiment 1.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 2.051 | 0.914 |

| Concreteness | 258.5 | 205.8 |

| Familiarity | 390.7 | 266.1 |

| Meaningfulness | 236.3 | 222.6 |

Other than the verbs, words across the sentences were closely matched on frequency. Following the main verb in R2, the two verbal complements were presented in a single region in R3. This way of combining the analysis region across the two verbal complements offers insight into participants’ verb–construction integration without causing extra processing difficulties. Given that many of the verbs, particularly those in the weaker association condition, are more frequently employed in simple transitive constructions than in prepositional dative constructions, the separation of the first complement (i.e., direct object) from the second (i.e., indirect object) may lead to potential misanalysis of the syntactic structure upon encountering the first complement. This misinterpretation can increase reading times when participants subsequently read the second complement.

The verb-centered view predicts that only the verb’s lexical properties will modulate the processing time in R3, leading to increased reading times as the verb is more difficult to retrieve. In contrast, the constructionist approach predicts that both the verb–construction association strength and the verb’s lexical information would influence reading times at R3 where readers will need to update their initial analysis by integrating the verb subcategorization information with the constructional frame. To test these predictions, the post-verbal complements (R3) were analyzed as the critical region. We additionally analyzed the following region (R4) to capture any spillover effects.

The two versions of the sentences were counterbalanced across two lists and randomly assigned to participants so that each person encountered only one condition of a single item. The complete experimental sentences can be found in Appendix A. The experimental stimuli were intermixed with 40 filler items comprising a variety of structural types such as simple intransitive, simple transitive, double object, relative-clause, and causative constructions.

4.3 Procedure

The experiment was run via a web-based interface using Ibex Farm (Drummond 2013). Each participant logged onto the experimental site and completed the language background questionnaire and the self-paced reading task. Participants in the NNS group additionally completed the written cloze test and self-ratings of English proficiency.

Prior to the self-paced reading task, participants received written instructions and worked through five practice items. In each trial, a target sentence was presented on a region-by-region basis in the non-cumulative moving window paradigm (Just et al. 1982). For example, a series of dashes appeared on the screen in the beginning of a trial, indicating the position of each region in the target sentence. Upon pressing the spacebar, the dash in the first region was replaced by the first phrase (e.g., The secretary). Subsequent spacebar press revealed the word in the following region (e.g., sent) while eliminating the previously displayed region, allowing participants to process the entire sentence at their own pace.

Following each sentence, a truth-false verification question was presented to assess participants’ understanding of the sentence. Half of the questions pertained to the content of the main clause, while the other half focused on the remaining part of the sentence. Participants responded by clicking on one of the two options provided below the question. The position of the correct and incorrect choices was randomly assigned by the program. We measured the participants’ reading times on each region as well as their accuracy rates on the verification questions.

The whole experiment took about 20 minutes for the NS group and 40 minutes for the NNS group.

4.4 Results and discussion

Prior to data analysis, we excluded three participants from the NS group and five from the NNS group, who scored below 80 % on the verification questions across all items. The mean accuracy rates for the remaining participants (25 NSs, 59 NNSs) were 91.8 % (SD = 6.0) for the NS and 89.4 % (SD = 5.1) for the NNS group. Although the scores were higher for the NS group compared to the NNS group (t(82) = 1.799, p = 0.076, Cohen’s d = 0.416), the participants in both groups achieved at least 80 % accuracy, indicating that they generally paid close attention to the sentence meaning during the task.

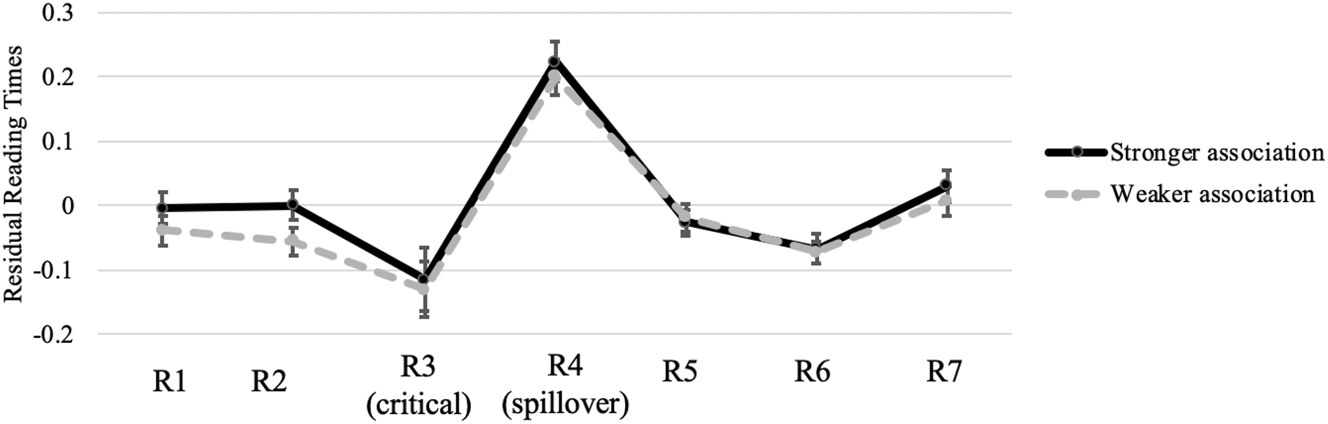

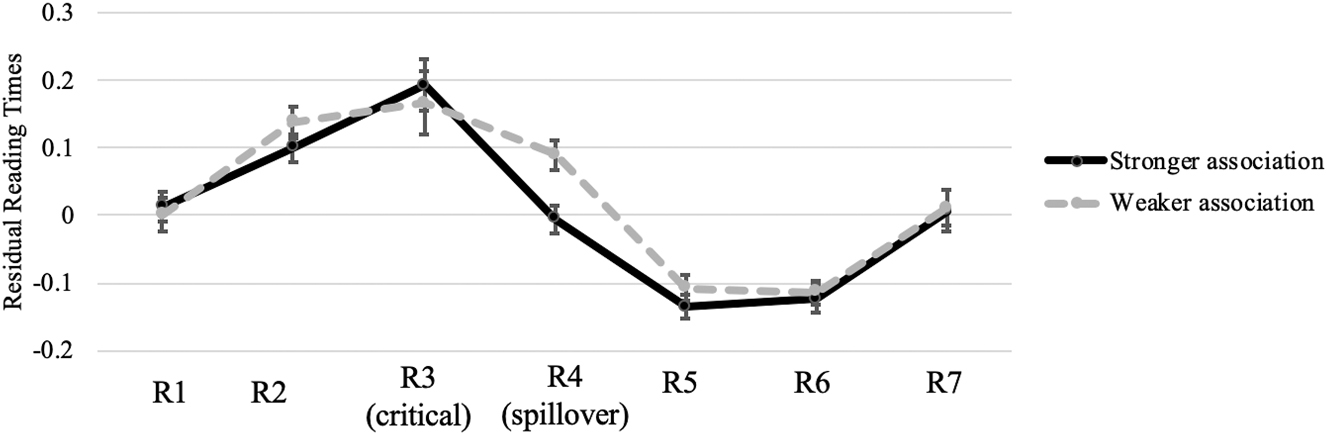

The reading time (RT) data for these participants were trimmed in the following steps. First, RTs longer than 3,000 ms and shorter than 100 ms were removed as outliers, which affected 2.7 % of the entire data. Next, RTs that fell beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean (5.9 %) were further eliminated. The remaining RTs were log-transformed to satisfy the normal distribution requirement (Ratcliff 1993). Finally, the log-transformed RTs were converted to residual RTs to adjust for differences in individuals’ reading speed and word length across items. Residual RTs across conditions are displayed in Figure 1 for the NS group and Figure 2 for the NNS group (mean raw RTs are reported in Appendix C). As shown in these figures, the NS group had almost identical reading times between the two conditions across all regions, whereas the NNS group spent longer times on R4 in the weaker association condition compared to the stronger association condition.

Residual RT profiles for the NS group; error bars denote 95 % confidence intervals.

Residual RT profiles for the NNS group; error bars denote 95 % confidence intervals.

To statistically compare the two groups’ reading-time patterns across the two conditions, linear mixed-effects regression models (lmer; Baayen 2008) were fitted to the residual RTs at the critical (R3) and spillover regions (R4), respectively. Each model included Group (NS, NNS) and Association (strong, weak) as fixed effects, which were centered around the mean using deviation coding (NS and strong association condition were coded as −0.5), and the random effects of Participant and Item. We constructed the maximal random-effects structure allowed by the design (Barr et al. 2013). The modelling was conducted in R version 4.3.3 (R Core Team 2024). Model outputs on R3 and R4 are presented in Table 2.

Experiment 1: Model outputs with the verb–construction association factor.

| Added factor | Region | Fixed Factors | Estimate | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb–construction association | Region 3 | Intercept | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.538 |

| (critical) | Group | 0.30 | 0.07 | < 0.001*** | |

| Association | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.750 | ||

| Group × Association | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.918 | ||

| Region 4 | Intercept | 0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.001*** | |

| (spillover) | Group | −0.17 | 0.04 | < 0.001*** | |

| Association | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.053 | ||

| Group × Association | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.047* |

-

***p < 0.001; *p < 0.05.

The model focusing on R3 showed a main effect of Group, with longer RTs in the NNS than the NS group, which is indicative of the typical trend of slower processing among L2 learners. Apart from this effect, there was no discernible effect of Association or an interaction between Group and Association. These findings suggest that both groups exhibited similar reading speeds across the two association conditions in the critical region.

The model for R4 showed a main effect of Group, with longer RTs observed for the NS group compared to the NNS group. Although no reliable effect of Association was found, there was a significant interaction between Group and Association. To further analyze this interaction, we conducted post-hoc Tukey tests for each group using estimated marginal means from the emmeans package in R (Lenth 2024). The results revealed a significant effect of Association for the NNS group (b = −0.09, p = 0.039), but not for the NS group (b = 0.01, p = 0.987). These findings suggest that only the L2 learners experienced greater difficulty when integrating the construction with verbs of weaker associations compared to those with stronger associations.

To further explore the modulating roles of the verb-related information on participants’ processing patterns, we included additional factors: verb frequency, concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness (all transformed to z-scores). Before conducting mixed-effects regression, we inspected potential collinearity among these variables, using correlation analyses. We set a correlation coefficient threshold of 0.7 (e.g., Kyle 2016). The results of these correlation analyses can be found in Appendix D. Our results indicated strong correlations between familiarity and concreteness (r = 0.847, p < 0.001), familiarity and meaningfulness (r = 0.730, p < 0.001), and concreteness and meaningfulness (r = 0.752, p < 0.001). To ensure that our models included variables with unique properties, we retained only verb frequency and concreteness, which showed stronger correlations with Association than verb familiarity and meaningfulness. These values were centered around the mean and added as continuous variables to the models. The model outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Model outputs in Experiment 1 with the verb-related factors.

| Added factor | Region | Fixed Factors | Estimate | SE | P value |

|

|

|||||

| Verb frequency | Region 3 | Intercept | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.510 |

| (critical) | Group | 0.30 | 0.07 | < 0.001*** | |

| Frequency | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.825 | ||

| Group × frequency | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.453 | ||

| Region 4 | Intercept | 0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.001*** | |

| (spillover) | Group | −0.17 | 0.04 | < 0.001*** | |

| Frequency | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.221 | ||

| Group × frequency | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.039* | ||

| Verb concreteness | Region 3 | Intercept | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.524 |

| (critical) | Group | 0.30 | 0.07 | < 0.001*** | |

| Concreteness | 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.993 | ||

| Group × concreteness | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.197 | ||

| Region 4 | Intercept | 0.11 | 0.02 | < 0.001*** | |

| (spillover) | Group | −0.16 | 0.04 | < 0.001*** | |

| Concreteness | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.083† | ||

| Group × concreteness | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.067† | ||

-

***p < 0.001; *p < 0.05; †p < .1.

At R3, we only found a main effect of Group in both the model that included verb frequency and the model that included verb concreteness. This effect indicated that the NNS group had significantly slower processing speed compared to the NS group. However, there were no significant effects associated with verb properties and their interaction with Group.

Turning to R4, the model including verb frequency demonstrated an interaction between Group and Frequency, as well as a main effect of Group. The model including verb concreteness revealed a marginal interaction between Group and Concreteness, along with a significant effect of Group and a marginal effect of Concreteness. In light of these interactions, we further conducted by-group analyses. In the NS group, none of the verb-related factor reached significance (all ps > 0.1). Conversely, in the NNS group, significant effects emerged for both verb frequency (b = −0.03, p = 0.025) and concreteness (b = −0.05, p = 0.004), with increased RTs as these values decreased. These findings suggest that L2 learners experienced greater processing difficulty in the spillover region when the verb was less frequent and less concrete.

Adding proficiency scores to the models did not reveal any significant interactions, suggesting that the participants’ proficiency did not influence their processing behaviors.

In summary, the results of Experiment 1 indicated that the L2 learners’ processing of the prepositional dative construction was influenced by both the association strength between the verb and the construction and the lexical properties of the verb. These findings are consistent with the constructionist approach, which predicted that both verbs and verb–construction association influence L2 sentence processing. It appeared that our L2 participants’ limited experience with the L2 resulted in reduced sensitivity to the statistical patterns of verb and construction usage, leading to difficulties in integrating verbal and constructional information during processing.

However, it is important to note some caveats before drawing definitive conclusions. First, the study focused exclusively on the prepositional dative construction, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, despite the graded nature of verb–construction association (Kyle 2016), the study employed a categorical approach by bisecting the association types into two conditions. This method of grouping may have obscured potential effects of individual differences in verb–construction association. To address these concerns, we conducted a second self-paced reading study (Experiment 2), which focused on the caused-motion construction and considered the continuous properties of verb–construction association.

5 Experiment 2: English caused-motion construction

5.1 Methods

The same participants from Experiment 1 joined Experiment 2, which occurred approximately one month later. It followed the same procedure as the previous experiment. The experimental items consisted of 32 caused-motion sentences, which were distributed across eight regions, as illustrated in (3).

| Susan (R1) / put (R2) / cookies (R3) / on the plate (R4) / as (R5) / she (R6) / |

| set (R7) / the table (R8). |

These sentences share semantic and structural features with the prepositional dative sentences used in Experiment 1. Both sentence types suggest that an object undergoes a change as a result of an agent’s action (Goldberg 1995). However, while the prepositional dative sentences in Experiment 1 involve a change in possession, the caused-motion sentences in Experiment 2 describe a change in an object’s position. We selected these closely related yet distinct constructions to minimize structural and semantic variations. While this approach compromises the diversity of constructions, it allows us to closely examine the roles of verbs and verb–construction associations in tightly controlled contexts, thereby enabling a more precise comparison of findings across both experiments.

In this experiment, two significant modifications were made compared to Experiment 1. First, the association score between the verb and the construction was treated as a continuous variable. We conducted a collexeme analysis to obtain a delta P value for each sentence, which was then converted to z-scores for data normalization. Second, in contrast to Experiment 1, where the two post-verbal complements were lumped in a single segment, we separated the second post-verbal complement (R4) from the first one (R3). This change aimed to accurately capture the point at which the integration of the verb and construction occurs. Unlike in Experiment 1, the verbs in this experiment involve caused-motion meanings, presupposing the existence of both a moved object and a goal. Therefore, no misanalysis was expected when the two post-verbal complements were separated. As a result, the second post-verbal complement (R4) was designated as the critical region for analysis, while the following segment (R5) served as the spillover region. The complete list of experimental items is available in Appendix B. The experimental items were interspersed with 48 filler items that included a variety of structures, such as intransitives, transitives, causatives, and relative clauses.

In addition, we measured the lexical properties of the verb using the same calculation methods as those in Experiment 1. The descriptive statistics of the verb–construction association strength and verb-related metrics are presented in Table 4.

Information of the verbs used in Experiment 2.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Association strength | −0.316 | 0.677 |

| Frequency | 2.256 | 0.887 |

| Concreteness | 263.8 | 182.9 |

| Familiarity | 406.8 | 259.9 |

| Meaningfulness | 291.1 | 191.7 |

5.2 Results and discussion

We first report the participants’ responses to the truth-value verification questions. Two participants (one from the NS group and one from the NNS group) were excluded from further analysis due to their low accuracy on the questions (less than 80 %). This resulted in a remaining sample of 27 participants in the NS group and 63 participants in the NNS group. All participants scored at least 80 %: the mean accuracy for the remaining participants was 91.5 % (SD = 6.8) for the NS group and 89.1 % (SD = 5.7) for the NNS group. The RT data from these participants were screened for outliers using the same method as in Experiment 1. RTs beyond the range of 100–3,000 ms (0.9 % of the entire data) and RTs more than 2 standard deviations from the mean (4.6 %) were eliminated. The trimmed RTs were then log-transformed and residualized. The mean raw RTs can be found in Appendix E.

To probe the effects of verb–construction association and verb-related values on the participants’ processing, we created linear mixed-effects regression models to analyze the residual RTs in the R4 and R5. As in Experiment 1, we inspected potential multicollinearity among the verb-related variables. We found strong correlations between familiarity and concreteness (r = 0.927, p < 0.001), familiarity and meaningfulness (r = 0.969, p < 0.001), and concreteness and meaningfulness (r = 0.961, p < 0.001). Therefore, we eliminated verb familiarity and meaningfulness. The results of these correlation analyses can be found in Appendix F. For each region, the models included a fixed factor of verb–construction association or verb-related values as a continuous variable (centered around the mean), as well as a categorical fixed factor of Group (NS, NNS). The Group factor was centered around the mean using deviation coding, with NS coded as −0.5. The maximal random-effects structure allowed by the design was used to include random intercepts for Participant and Item, as well as a by-participant random slope for Association and a by-item random slope for Group. The results of the models are presented in Table 5.

Model outputs in Experiment 2: Critical region.

| Added factor | Region | Fixed Factor | Estimate | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb–construction association | Region 4 | Intercept | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.002** |

| (critical) | Group | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.011* | |

| Association | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.636 | ||

| Group × Association | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.615 | ||

| Region 5 | Intercept | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.923 | |

| (spillover) | Group | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.008** | |

| Association | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.143 | ||

| Group × Association | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.030* | ||

| Verb frequency | Region 4 | Intercept | 0.07 | 0.01 | < 0.001*** |

| (critical) | Group | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.012* | |

| Frequency | −0.06 | 0.01 | < 0.001*** | ||

| Group × frequency | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.850 | ||

| Region 5 | Intercept | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.972 | |

| (spillover) | Group | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.002** | |

| Frequency | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.200 | ||

| Group × frequency | −0.12 | 0.03 | < 0.001*** | ||

| Verb concreteness | Region 4 | Intercept | 0.07 | 0.01 | < 0.001*** |

| (critical) | Group | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.012* | |

| Concreteness | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.024* | ||

| Group × concreteness | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.376 | ||

| Region 5 | Intercept | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.966 | |

| (spillover) | Group | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.002** | |

| Concreteness | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.191 | ||

| Group × concreteness | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.009** |

-

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

At R4, the main effect of Group consistently emerged, with the NNS group showing longer RTs than the NS group, regardless of the continuous variable added as a fixed factor. Although there was no main effect of Association, the effects of verb-related factors were found to be significant without its interaction with Group, with longer RTs observed as these verb-related values decreased. This result indicates that participants spent more time in this region as the verb became less frequent and less concrete. However, we did not observe any interaction between each of these factors with Group.

At R5, the main effect of Group continually emerged, regardless of the continuous factor included. Although Association, Verb frequency, and Verb concreteness did not reach significance, they all interacted significantly with Group, indicating that their effects varied between the NS and NNS groups. To unpack these interactions, separate analyses were conducted for each group using linear mixed-effects models that included each continuous variable as a fixed factor. The results showed that none of the factors were significant for the NS group (association: b = 0.03, p = 0.437; frequency: b = 0.05, p = 0.075; concreteness: b = 0.03, p = 0.174). In contrast, the model for the NNS group showed a main effect of each factor (association: b = −0.09, p = 0.019; frequency: b = −0.07, p < 0.001; concreteness: b = −0.06, p = 0.011). These findings indicate that the NNS group experienced greater processing difficulty when the verb–construction association strength was weaker, and the verb was less frequent and less concrete, whereas the NS group showed no signs of such difficulty.

When adding the L2 participants’ proficiency scores as a continuous variable to the L2 model, we did not find any significant interaction between the proficiency scores and association strength or the verb-related factors, in both R4 and R5 (all ps > 0.1). These findings are reminiscent of the outcomes obtained from Experiment 1, indicating a lack of proficiency effect on the integration of verb and construction in L2 processing. We will return to this finding and explore its potential explanations in General Discussion.

In summary, the results of Experiment 2 provided additional evidence that L2 learners’ integration of a verb and a construction was influenced by both the association strength and the verb’s lexical properties. This finding is consistent with the processing patterns obtained in Experiment 1, suggesting that the effects of verb–construction association strength and verb-related factors extended to the caused-motion construction. In the following section, we discuss these findings in light of the theoretical approaches to the L2 integration of a verb and a construction outlined earlier.

6 General discussion and conclusion

This study investigated the modulating roles of verb–construction association and verb-related properties in L2 sentence processing. Two self-paced reading experiments were conducted, each involving different construction types. The results from both experiments provided converging evidence that L2 learners encountered varying degrees of processing difficulties, contingent upon the strength of associations between a verb and a construction, as well as the lexical properties of the verb. Specifically, the findings revealed that L2 learners exhibited increased processing times when the verb had weak association with the target construction, and when the verb was less frequent and less concrete.

The significant effects of the verb-related factors suggest that L2 learners’ integration of verbs and constructions was tempered by delayed retrieval of verb information. This finding aligns with the Weaker Links hypothesis (Gollan et al. 2008) and the Revised Hierarchical Model (Kroll and Stewart 1994), which propose that L2 learners struggle with lexical retrieval during processing. While previous studies primarily focused on word frequency as the main source of lexical retrieval delays during L2 syntactic processing (Hopp 2014), our study expanded this investigation to include not only verb frequency but also concreteness, familiarity, and meaningfulness. Consequently, we have demonstrated that various aspects of verb lexical properties can influence its retrieval.

In line with the Weaker Links hypothesis and the Revised Hierarchical Model Recall, we attribute the observed difficulties in lexical retrieval and the integration of verbs and constructions among our L2 participants to their limited experience with the L2. As the L2 participants in our study primarily engaged with English in classroom settings, where input quantity and quality were likely restricted (Saito 2017), they may have lacked sufficient exposure to the target verbs. This paucity of naturalistic L2 input may have hindered their ability to retrieve verb meanings and integrate them with the target constructions. Moreover, the learners’ limited English experience may have rendered it difficult for them to efficiently inhibiting interference from their L1 knowledge when accessing the meanings of target verbs. In addition to supporting the notion of delayed lexical retrieval, our findings also demonstrated that this delayed retrieval impeded the integration of verbal and constructional information during L2 processing. These results extend prior research, which showed the influence of delayed lexical processing in syntactic ambiguity resolution (Hopp 2014), by demonstrating the effect of verbal retrieval on the integration of verbs and constructions.

Notably, our findings offer novel evidence that L2 processing is influenced by both the lexical properties of verbs and their associations with constructions. Contrary to the verb-centered view, which predicted that verb retrieval serves as the major determinant affecting the verb–construction integration process, our results reveal that the association strength between verbs and constructions also impacts L2 learners’ integration of verbs and constructions. This finding aligns with the constructionist approach that emphasizes the combined contribution of verb and construction information to derive a sentence meaning (Goldberg 1995, 2013]). Once again, we propose that our L2 participants’ limited experience with the L2 serves as a major factor contributing to their reduced ability to uptake the distributional patterns of verbs within the constructions. For example, our learners had greater difficulty in integrating the dative construction with the verb text (e.g., The secretary texted the schedule to the president) compared to send during online processing. This discrepancy may arise from the fact that the association between text and the dative construction remained more tenuous within the limited and noisy representations of L2 knowledge among the L2 participants, leading them to perceive it as an uncommon occurrence outside of their language experience. In contrast, the native speaker group was unaffected by association strength, as they spent similar amounts of time to integrate verbal and constructional information. It appears that they had established stable and detailed representations based on an abundance of concrete exemplars showcasing the usage of verbs and constructions in the input (e.g., the dative use of the verbs send and text). This extensive language-usage experience may have facilitated their utilization of fully developed constructional knowledge for sentence processing.

The divergent processing patterns observed in our L2 participants may also have been influenced by the increased cognitive load associated with integrating verbs and constructions. Previous research has shown that even advanced L2 learners exhibit delayed or less accurate processing behaviors when integrating multiple sources of information, which can be attributed to reduced automaticity and limited memory capacities (Cunnings 2017; Pozzan and Trueswell 2016; Sorace 2011; Sorace and Filiaci 2006). Therefore, it is plausible that our L2 participants experienced considerable demands on their working memory resources when integrating multiple information sources, leading to effortful and delayed integration of verbs and constructions during sentence processing. However, since our design did not specifically account for working memory or processing demands, the precise interplay between cognitive demands on verb–construction integration and their effects on learners’ processing behavior remains unclear. Future research should explore this connection in detail by involving learners with varying working memory capacities or from different L2 learning contexts. For instance, L2 learners with higher working memory capacity or those who have undergone long-term immersion in the L2 may exhibit more target-like processing of verb–construction integration (Linck et al. 2014; Pliatsikas and Marinis 2013).

In contrast to the significant influence of verb-related information and verb–construction association, we did not find notable modulating effects of proficiency on the processing patterns of L2 learners. This finding appears inconsistent with previous observations that an increase in proficiency leads to the expansion of L2 learners’ knowledge about verbs and constructions, enabling them to utilize a wide range of verbs within target constructions (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009; Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2009; Kyle and Crossley 2017). There are several possible explanations for the absence of a proficiency effect in our study. One plausible account is that the proficiency levels of our participants were not sufficiently high. Despite our efforts to recruit L2 learners with varying proficiency levels, our sample primarily consisted of learners who acquired English in a classroom setting, which is the most common type of college student population in South Korea. Furthermore, the small sample size may have limited the variability in participants’ proficiency, potentially reducing the statistical power to detect any proficiency effects in our analyses. To address these limitations, future research should increase the sample size and include learners with a broader range of proficiency levels.

An alternative interpretation of the lack of a significant effect of proficiency is that L2 learners’ reduced ability to extract statistical patterns of verb–construction association remains a vulnerable aspect of L2 processing. It is plausible that the linguistic representations of L2 knowledge are inherently less stable and noisier compared to those of L1 knowledge (Futrell and Gibson 2017; Tachihara and Goldberg 2020). Consequently, L2 learners may have lingering difficulties in utilizing statistical information regarding verb–construction association during processing, irrespective of their level of proficiency in the L2. This interpretation suggests that even highly proficient learners may not be entirely free from the influence of their inherently unstable and noisy representations. It highlights the persistent challenges that L2 learners face in developing fully native-like processing abilities, particularly when it comes to integrating verbs and constructions in a statistically appropriate manner.

If this speculation is valid, the integration of verb and construction information in the L2 can be considered as an additional significant source of difficulty in the processing of non-dominant languages. This variable may serve as another influential factor alongside previously recognized factors, such as unstable lexical representations (Hopp 2018), limited ability to compute syntactic dependencies (Clahsen and Felser 2006, 2018]), limitations in working memory capacity (Hopp 2014), and interference in memory retrieval operations (Cunnings 2017). To determine the generalizability of L2 learners’ reduced ability to deploy statistical information of verb–construction association, further research is necessary to examine the L2 processing of verb–construction integration across learners with diverse language backgrounds and learning contexts. Such investigations will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how L2 learners in various contexts cope with the challenges of integrating verb and construction information during sentence processing. This line of inquiry will shed further light on the underlying mechanisms that contribute to differences in processing between L1 and L2 speakers.

Finally, we acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, the significant roles of verb-related variables and verb–construction associations observed in our study are confined to the prepositional dative and caused-motion constructions. As previously noted, these two constructions are highly related in terms of form and meaning, which enables a focused comparison of findings across both experiments in controlled contexts. However, this narrow focus also presents limitations in the generalizability of our findings. As the observed effects are specific to these two constructions, they may not extend to other construction types that differ substantially in form or meaning. Moreover, the controlled nature of our study may not fully capture the complexity and diversity of language use in real-world contexts where a wider range of construction types and verbs are employed. To address these limitations, future research should broaden the scope to include a wider variety of construction types with diverse syntactic structures and meanings.

Second, the reading-time data in our study may not be entirely consistent. Although Ibex Farm, the online platform used in our experiments, is well-established and frequently employed in reading-time studies, the reliability of the data may have been affected by variability in online conditions experienced by participants. To mitigate the potential effects of this variation, we trimmed data by removing outliers and residualizing reading times. We also accounted for individual differences by incorporating by-participant random slopes and intercepts in our model. Nevertheless, some limitations remain, particularly concerning the network variability present among participants, which could introduce noise into the data. Therefore, future studies should consider employing more stable and ecologically valid methods, such as collecting self-paced reading or eye-tracking conducted in a controlled offline lab setting, and compare these outcomes with those of the current study.

Third, we acknowledge that conducting separate analyses for verb–construction association, verb frequency, and verb concreteness may increase the risk of the Type I error. Given the distinct theoretical constructs and the variability within our data, we treated each variable independently through separate models. Nonetheless, this approach may necessitate a more stringent threshold for statistical significance to mitigate the increased likelihood of false positives. For instance, one may employ the Bonferroni correction method, adjusting the significance threshold to p < 0.017 (derived from 0.05 divided by 3 for our main analyses). It is important to note that when applying this more conservative threshold, some of the effects reported as significant become only marginal. This adjustment in significance levels underscores the importance of cautious interpretation of our results. Future studies should address this issue by considering alternative statistical approaches, such as multiple regression, or employing larger sample sizes to achieve more reliable insights into the relationships between these variables and L2 processing.

Fourth, while our study offers insights into the conjoined roles of both verb-specific variables and the associations between verbs and constructions, it remains unclear which factor makes a stronger contribution to L2 processing. Because our primary objective was to test the hypotheses of the verb-centered view and the constructionist approach, investigations into the relative weight of each factor are beyond the scope of this research. However, future research could build upon our findings to develop a more comprehensive method that analyzes the interplay between lexical and constructional factors. Specifically, additional statistical techniques such as multiple regression analysis or structural equation modeling could be employed to disentangle the relative contributions of verb-specific variables and verb–construction association in L2 processing.[3]

Despite these limitations, we believe this study provides new insights into the individual and interactive roles of verbs and constructions in L2 sentence processing. The observed effects highlight the combined influence of verb–construction association and verbs’ lexical properties on L2 learners’ integration of verbs and constructions. Future research should aim to broaden the scope of investigation to include a wider variety of constructions and employ more ecologically valid methods. These efforts will enhance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying L2 processing, particularly regarding the integration of verbs and constructions.

-

Data availability: The R scripts and datasets in this article are available in the OSF repository, at https://osf.io/vkfyj/.

Appendix A: Experimental sentences used in Experiment 1

| The student sent/emailed the homework to his professor after he was finally finished. |

| The lady made/baked the cake for her son because it was his favorite food. |

| The businessman gave/offered the laptop to his girlfriend because hers was broken. |

| The engineer got/offered the lamp to his coworker because her room was dark. |

| The woman made/cooked the pasta for her husband because he worked so hard. |

| The guest handed/presented the gift to the host before she left in the evening. |

| The secretary sent/texted the schedule to the president after work on Tuesday. |

| The lawyer passed/faxed the file to the intern as she left the office. |

| The CEO gave/assigned the office to the analyst after consulting his partner. |

| The scientist showed/displayed the notebook to his assistant as he explained his latest project. |

| The secretary bought/booked the flight ticket for her boss early in the morning. |

| The musician brought/knitted the scarf for his teacher because of her help with music theory. |

| The student wrote/forwarded the letter to her professor after the completion of her project. |

| The doctor bought/served the dinner for the nurse after a romantic date at the beach. |

| The editor bought/saved the cookies for the typist because she had not eaten. |

| The bartender handed/offered the beer to the dancer because she looked lonely. |

| The waiter took/delivered the pizza to the customer after he served the appetizer. |

| The librarian brought/presented the novel to the student because she was eager to read it. |

| The woman showed/presented the coupon to the cashier to get a 15 % discount for the shoes. |

| The banker bought/fetched the stapler for his coworker because he asked to use it. |

| The boy passed/delivered the note to his friend during class on Monday morning. |

| The gentleman threw/pitched the coin to the beggar because he asked for it. |

| The player threw/pitched the ball to his coach because he asked to see it. |

| The professor wrote/prepared the letter for the student because she was at the top of her class. |

Appendix B: Experimental sentences used in Experiment 2

| <Caused-motion construction> Kevin brought the sofa into his room after he finished cleaning. |

| John brought the book to school after he finished reading. |

| Susan placed cookies on the plate as soon as she sat on the table. |

| Amy placed dishes on the table before the guests arrived. |

| Susan put cookies on the plate as she set the table. |

| Hailey put the doll in the box before she went outside. |

| Jason sent the news to his friends as soon as he heard it. |

| Peter sent flowers to his fiancé because it was her birthday. |

| Kevin shifted the sofa into his room after he finished cleaning. |

| Rob shifted the bag to his other shoulder as he crossed the street. |

| Jessica spilled water onto the table when her parents were having dinner. |

| Beth spilled juice onto the floor when she suddenly stood up. |

| Jason spread the news to his friends when he heard it. |

| Matthew spread the jam on the bread as he listened to the radio. |

| Jessica took a flower into her room because she had a vase. |

| Lisa took a dog into her house when she found it on the street. |

| Susan dropped a letter on the table while I was in the office. |

| Sally took the dog into the house when she found her on the street. |

| Tom threw the ball over the wall when he found it in the yard. |

| Paul sent some money to his mother before he went on a journey. |

| Billy sent flowers to my house when I graduated from the school. |

| Ethan dropped a magazine on the sofa when I felt bored. |

| Tom kicked the ball into the hole when played alone in the park. |

| Justin brought his dog to the party because everyone loved the dog. |

| Julie faxed the message to the company before she returned to her office. |

| Nathan passed a sandwich to me when I was sitting on the bench. |

| Ronald sent an email to the government while he was in the office. |

| Celine delivered a cake to my house because it was my birthday. |

| Derek showed his ID to the guard as he entered the building. |

| Jorge showed his dog to me when I visited his room. |

| Aaron threw his hat on the sofa as he entered the room. |

| Nancy tossed the menu on the table after she finished her order. |

Appendix C: Raw reading times (standard deviations) in milliseconds by region in Experiment 1

| Group | Condition | R1 | R2 | R3 (critical) | R4 (spillover) | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native speakers | Strong | 498 (226) | 410 (141) | 703 (367) | 545 (245) | 399 (164) | 385 (125) | 511 (206) |

| Weak | 468 (158) | 418 (164) | 673 (336) | 528 (229) | 397 (134) | 379 (110) | 507 (209) | |

| Nonnative speakers | Strong | 588 (285) | 538 (231) | 952 (332) | 495 (197) | 419 (188) | 426 (165) | 593 (291) |

| Weak | 587 (287) | 606 (294) | 958 (374) | 548 (233) | 431 (189) | 431 (176) | 597 (276) |

Appendix D: Correlations between the lexical properties of verbs in Experiment 1

| Pearson’s Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Association | Frequency | Familiarity | Concreteness | Meaningfulness | |

| 1. Association | Pearson’s r | – | ||||

| p-value | – | |||||

| 2. Frequency | Pearson’s r | 0.177 | – | |||

| p-value | 0.085 | – | ||||

| 3. Familiarity | Pearson’s r | 0.082 | 0.534 | – | ||

| p-value | 0.426 | < 0.001 | – | |||

| 4. Concreteness | Pearson’s r | 0.033 | 0.511 | 0.847 | – | |

| p-value | 0.751 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | ||

| 5. Meaningfulness | Pearson’s r | 0.123 | 0.609 | 0.730 | 0.752 | – |

| p-value | 0.231 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | |

Appendix E: Raw reading times (standard deviations) in milliseconds by region in Experiment 2

| Group | R1 | R2 | R3 (critical) | R4 (spillover) | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native speakers | 468 (158) | 418 (164) | 673 (336) | 528 (229) | 397 (134) | 379 (110) | 507 (209) |

| Nonnative speakers | 587 (287) | 606 (294) | 958 (374) | 548 (233) | 431 (189) | 431 (176) | 597 (276) |

Appendix F: Correlations between the lexical properties of verbs in Experiment 2

| Pearson’s Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Association | Frequency | Familiarity | Concreteness | Meaningfulness | |

| 1. Association | Pearson’s r | – | ||||

| p-value | – | |||||

| 2. Frequency | Pearson’s r | 0.532 | – | |||

| p-value | 0.002 | – | ||||

| 3. Familiarity | Pearson’s r | 0.306 | 0.658 | – | ||

| p-value | 0.088 | < 0.001 | – | |||

| 4. Concreteness | Pearson’s r | 0.354 | 0.580 | 0.927 | – | |

| p-value | 0.047 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | ||

| 5. Meaningfulness | Pearson’s r | 0.343 | 0.581 | 0.969 | 0.961 | – |

| p-value | 0.054 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | – | |

References

Ahrens, Kathleen V. 1995. The mental representations of verbs. San Diego: University of California Unpublished doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Akhtar, Nameera. 1999. Acquiring basic word order: Evidence for data-driven learning of syntactic structure. Journal of Child Language 26. 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/s030500099900375x.Search in Google Scholar

Altmann, Gerry T. M. & Yuki Kamide. 1999. Incremental interpretation at verbs: Restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition 73. 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00059-1.Search in Google Scholar

Ambridge, Ben, Julian M. Pine, Caroline F. Rowland & Chris R. Young. 2008. The effect of verb semantic class and verb frequency (entrenchment) on children’s and adults’ graded judgments of argument-structure overgeneralization errors. Cognition 106. 87–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.015.Search in Google Scholar

Ambridge, Ben, Amy Bidgood, Katherine E. Twomey, Julian M. Pine, Caroline F. Rowland & Daniel Freudenthal. 2015. Preemption versus entrenchment: Towards a construction-general solution to the problem of the retreat from verb argument structure overgeneralization. PLoS One 10. e0123723. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123723.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, R. Harald. 2008. Analyzing linguistic data. A practical introduction to statistics using R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511801686Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, R. Harald, Richard Piepenbrock & Leon Gulikers. 1996. The CELEX lexical database [CD-ROM]. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Linguistic Data Consortium.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68. 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bencini, Giulia M. L. & Adele E. Goldberg. 2000. The contribution of argument structure constructions to sentence meaning. Journal of Memory and Language 43. 640–651. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2000.2757.Search in Google Scholar

Boyd, Jeremy K. & Adele E. Goldberg. 2011. Learning what not to say: The role of statistical preemption and categorization in a-adjective production. Language 87(1). 55–83. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2011.0012.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, James. 1980. Relative merits of four methods for scoring cloze tests. The Modern Language Journal 64. 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1980.tb05198.x.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Aimee L. & Michael Tomasello. 2001. The acquisition of English dative constructions. Applied Psycholinguistics 22. 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716401002065.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris.Search in Google Scholar

Clahsen, Harald & Claudia Felser. 2006. Continuity and shallow structures in language processing. Applied Psycholinguistics 27. 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716406060206.Search in Google Scholar

Clahsen, Harald & Claudia Felser. 2018. Some notes on the shallow structure hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40. 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263117000250.Search in Google Scholar

Cunnings, Ian. 2017. Parsing and working memory in bilingual sentence processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20. 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728916000675.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2010. The Corpus of Contemporary American English as the first reliable monitor corpus of English. Literary and Linguistic Computing 25. 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqq018.Search in Google Scholar

Drummond, Alex. 2013. Ibex Farm. Available at: http://spellout.net/ibexfarm/ (not available as of 30 September 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2002. Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 24. 143–188. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263102002024.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. & Fernando Ferreira-Junior. 2009. Constructions and their acquisition: Islands and the distinctiveness of their occupancy. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 7. 188–221. https://doi.org/10.1075/arcl.7.08ell.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. & Diane Larsen-Freeman. 2009. Constructing a second language: Analyses and computational simulations of the emergence of linguistic constructions from usage. Language Learning 59. 90–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00537.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C., Matthew Brook O’ Donnell & Ute Römer. 2013. Usage-based language: Investigating the latent structures that underpin acquisition. Language Learning 63. 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00736.x.Search in Google Scholar

Futrell, Richard & Edward Gibson. 2017. L2 processing as noisy channel language comprehension. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20(4). 683–684. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728916001061.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2013. Argument structure constructions versus lexical rules or derivational verb templates. Mind & Language 28. 435–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12026.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2019. Explain me this: Creativity, competition, and the partial productivity of constructions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.2307/j.ctvc772nnSearch in Google Scholar

Goldwater, Micah B. & Arthur B. Markman. 2009. Constructional sources of implicit agents in sentence comprehension. Cognitive Linguistics 20. 675–702. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2009.029.Search in Google Scholar

Gollan, Tamar H., Rosa I. Montoya, Cynthia Cera & Tiffany C. Sandoval. 2008. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language 58. 787–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.001.Search in Google Scholar

Gollan, Tamar H., Rosa I. Montoya, Cynthia Cera, Tiffany C. Sandoval, Wouter Duyck & Keith Rayner. 2011. Frequency drives lexical access in reading but not in speaking: The frequency-lag hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 140. 186–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022256.Search in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan Th & Anatol Stefanowitsch. 2004. Extending collostructional analysis: A corpus-based perspective on ‘alternations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 9. 97–129. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.9.1.06gri.Search in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan Th & Stephanie Wulff. 2005. Do foreign language learners also have constructions? Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 3. 182–200. https://doi.org/10.1075/arcl.3.10gri.Search in Google Scholar

Grüter, Theres, Hannah Rohde & Amy J. Schafer. 2017. Coreference and discourse coherence in L2. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7. 199–229. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.15011.gru.Search in Google Scholar

Healy, Alice F. & George A. Miller. 1970. The verb as the main determinant of sentence meaning. Psychonomic Science 20. 372. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03335697.Search in Google Scholar

Hopp, Holger. 2014. Working memory effects in the L2 processing of ambiguous relative clauses. Language Acquisition 21. 250–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2014.892943.Search in Google Scholar

Hopp, Holger. 2017. Cross-linguistic lexical and syntactic co-activation in L2 sentence processing. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7. 96–130. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.14027.hop.Search in Google Scholar

Hopp, Holger. 2018. The bilingual mental lexicon in L2 sentence processing. Second Language 17. 5–27.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Nan. 2007. Selective integration of linguistic knowledge in adult second language learning. Language Learning 57. 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00397.x.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Matt & Adele Goldberg. 2013. Evidence for automatic accessing of constructional meaning: Jabberwocky sentences prime associated verbs. Language and Cognitive Processes 28(10). 1439–1452. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2012.717632.Search in Google Scholar

Just, Marcel A., Patricia A. Carpenter & Jacqueline D. Woolley. 1982. Paradigms and processes and in reading comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 3. 228–238.10.1037//0096-3445.111.2.228Search in Google Scholar

Kaschak, Michael P. & Arthur M. Glenberg. 2000. Constructing meaning: The role of affordances and grammatical constructions in sentence comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language 43. 508–529. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2000.2705.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Hyunwoo & Yangon Rah. 2019. Constructional processing in a second language: The role of constructional knowledge in verb-construction integration. Language Learning 69. 1022–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12366.Search in Google Scholar