Abstract

This study explores the diachronic development of the Mandarin complex directional complement guòlái ‘come over’ from the macro-event perspective. By analyzing data retrieved from the CCL corpus spanning 15 Chinese dynasties (1046 BCE-1920s), this study reveals that guòlái ‘come over’ can be initially traced back to the pattern guò N (ér) lái, where guò and lái functioned as distinct motion verbs. It then served as a motion verb, which subsequently grammaticalized into a directional complement. The diachronic evolution of the macro-event types represented by the V guòlái construction can tentatively be described as: Motion Event > Event of Realization > Event of State Change / Event of Action Correlating (> Event of Temporal Contouring). This study further proposes the Unidirectional Progression Hypothesis concerning the entire closed set of directional complements, suggesting that Mandarin directional complements evolve both in form and meaning along a unidirectional trajectory, becoming syntactically tighter and semantically more abstract.

1 Introduction

Mandarin complex directional complements have been widely examined since the 1980s (Yang 2004). Previous research has predominantly concentrated on their semantics (e.g., Liu 1998; Zhang 2010; Zhou 1991), sentence patterns (e.g., Xiao 1992; Zhang and Fang 1996), as well as language acquisition and pedagogy (e.g., Yang 2003; Zhu 2018, 2019). Additionally, some studies have embraced a cognitive perspective, investigating the motivating image schemas (e.g., Ma 2005) and applying the principle of temporal sequence to their syntactic structures (e.g., Yang 2005, 2017). However, it is worth noting that, apart from a few studies such as Li (2018, 2019) that mainly focused on simplex directional complements from a cognitive semantic perspective, the exploration of complex directional complements from the macro-event perspective has been relatively scant.

According to Talmy (2000b), the macro-event, regarded as fundamental and ubiquitous in the underlying conceptual organization of language, forms the basis of his well-known two-way typology (Talmy 1985, 1991, 2000b). Within this framework, Mandarin is classified as a satellite-framed language, a categorization that has sparked debate over the past few decades (e.g., Shen 2003; Shi 2011; Li 2018) due to its complex grammaticalization processes, which influence both its form and typological classification. Scholars have put forward divergent perspectives: some contend that ancient Mandarin was verb-framed and subsequently evolved into a satellite-framed language in modern times (e.g., Shi 2011; Li J. 2020), while others advocate for classifying Mandarin as a parallel-framed language (Slobin 2004; Luo 2008). Overall, prior research has not only recognized the challenges inherent in the two-way typology but has also emphasized the need for more generalized principles governing the expression of two related events and their semantic relationships across languages. Motivated by these discussions, the Macro-event Hypothesis (Li 2019, 2020, 2023) was proposed as a new theoretical framework to address these issues, introducing four continua: semantic, syntactic, grammaticalization, and typological. While some studies have provided preliminary support (e.g., Li and Liu 2021; Liu and Li 2023), empirical evidence specifically from Mandarin complex directional complements remains scarce. Therefore, to further validate this hypothesis, this study investigates the diachronic development of guòlái ‘come over’ from the macro-event perspective, with a particular focus on its syntactic and semantic evolution.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the fundamental concepts and prior studies on Mandarin directional complements. Section 3 introduces the macro-event and the Macro-event Hypothesis. Section 4 details the methodology, followed by the presentation of results in Section 5. Section 6 discusses the findings in relation to previous research and introduces the Unidirectional Progression Hypothesis. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the major findings and points out the limitations.

2 Mandarin directional complements

In Chinese linguistics, there is a consensus that directional complements, originally independent verbs, have undergone grammaticalization to serve as complements following the main verb. Lyu (1980) identified two types of verb-complement constructions: directional complement construction and resultative construction, with guòlái ‘come over’ exemplifying the former. Liu (1998) further systematically compiled an exhaustive inventory of Mandarin directional complements from a semantic perspective. She defined directional complements as “directional verbs functioning as complements after a verb or adjective” (p. 1) and identified a closed set of 28 directional complements in Mandarin – 11 simplex and 17 complex – categorizing guòlái ‘come over’ within the latter group (see Table 1).

28 Mandarin directional complements (C = complement) (Li 2018: 595).

| Simplex C (11) | Complex C (17) |

|---|---|

| C1: 来-lái ‘come’ | Ways of Compounding: C3-C11 + C1/C2 = C12-C28 |

| C2: 去-qù ‘go’ | |

| C3: 上-shàng ‘up’ | C3 + C1 = C12 C12: 上来-shànglái ‘come up’ |

| C3 + C2 = C13 C13: 上去-shàngqù ‘go up’ | |

| C4: 下-xià ‘down’ | C4 + C1 = C14 C14: 下来-xiàlái ‘come down’ |

| C4 + C2 = C15 C15: 下去-xiàqù ‘go down’ | |

| C5: 进-jìn ‘into’ | C5 + C1 = C16 C16: 进来-jìnlái ‘come into’ |

| C5 + C2 = C17 C17: 进去-jìnqù ‘go into’ | |

| C6: 出-chū ‘out’ | C6 + C1 = C18 C18: 出来-chūlái ‘come out’ |

| C6 + C2 = C19 C19: 出去-chūqù ‘go out’ | |

| C7: 回-huí ‘back’ | C7 + C1 = C20 C20: 回来-huílái ‘return come’ |

| C7 + C2 = C21 C21: 回去-huíqù ‘go back’ | |

| C8: 过-guò ‘pass’ | C8 + C1 = C22 C 22 : 过来-guòlái ‘come over’ |

| C8 + C2 = C23 C23: 过去-guòqù ‘go over’ | |

| C9: 起-qǐ ‘up’ | C9 + C1 = C24 C24: 起来-qǐlái ‘get up’ |

| C10: 开-kāi ‘away’ | C10 + C1 = C25 C25: 开来-kāilái ‘away’ |

| C10 + C2 = C26 C26: 开去-kāiqù ‘away’ | |

| C11:到-dào ‘to’ | C11 + C1 = C27 C27: 到…来-dào…lái ‘come to’ |

| C11 + C2 = C28 C28: 到…去-dào…qù ‘go to’ |

Specifically, the Mandarin complex directional complement guòlái ‘come over’, the focus of the present research, is a compound of two distinct verbs, i.e., guò ‘pass’ and lái ‘come’. According to the online version of Hanyu Da Zidian (Great Compendium of Chinese Characters),[1] the most extensive and comprehensive Chinese dictionary detailing the form, pronunciation, and meaning of each character, guò conveys directional meanings such as “pass” and “cross (a river, the sea, etc.)”, denoting physical displacement in space. It also extends into the temporal domain, meaning “over”, as seen in chī guò fàn ‘eat-PFV a meal’. As for lái, it carries the directional meaning of “from there to here” or “from far to near”, in contrast to qù ‘go’ or ‘leave’. It can also indicate a temporal period, as exemplified in yòu lái ‘since childhood’, a usage attested in the Tang dynasty. Each of these meanings is illustrated with examples from the dictionary, as shown in Table 2.

Dictionary meanings of guò and lái.

| 过-guò ‘pass’ | 1. Jīngguò ‘pass’. | Zǐ jī qìng yú wèi, yǒu hékuì ér

guò

kǒngshì zhī mén zhě. Confucius hit Qing at Wei there-be carry-basket CONJ pass Confucius GEN door NOM ‘When Confucius was striking a Qing (a kind of musical instrument) in the state of Wei, a man carrying a straw basket passed his door.’ (Lùn Yǔ · Xiàn Wèn, the Warring States Period) |

| 2. Dùguò ‘cross (a river, the sea, etc.)’. |

Guò

shuǐ cǎi píng. pass river pick-up duckweed ‘Cross the river and pick up the duckweed.’ (Shī Pǐn · Zì Rán, the Tang Dynasty) |

|

| 3. Guòqù ‘over’. | Ruò shì

guò

ér hòu zhī, zé yǔ wúzhìzhě qí yǐ. if affair pass CONJ afterwards know CONJ with without-wisdom-NOM equal SFP ‘If someone only understands the event after it was over, it is equivalent to being unintelligent.’ (Xīn Lùn · Guì Sù, the Northern Qi Dynasty) |

|

| 4. Dùguò, guòhuó ‘live a life’. | Nánér zhàng jiàn chou ēn zài, wèi kěn túrán

guò

yīshēng. man hold sword repay favor exist NEG willing in-vain spend life ‘A man should repay a favor with a sword, unwilling to live a life in vain.’ (LuànHòu Sù NánLíng FèiSì Jì ShěnMíngFǔ, Tang Dynasty) |

|

| 来-lái ‘come’ | 1. Yóu bǐ zhì cǐ ‘from there to here’; yóu yuǎn dào jìn ‘from far to near’. Yǔ “qù” “wǎng” xiāngduì ‘constrasting with qù ‘go’ and wǎng ‘go’’. | Yǒu péng zì yuǎnfāng

lái

. There-be friend from far-place come ‘It is always a pleasure to greet a friend coming from afar.’ (Lún Yǔ · Xué Ér, the Warring States Period) |

| 2. (Shìwù) chǎnshēng ‘(things) appear’; dàolái ‘arrive’. | Fú yōuhuàn zhī

lái

, yīng rénxīn yě. TOP suffering-trouble GEN come disturb heart SFP ‘When sorrows come, one would suffer from a heartbreaking pain.’ (Huái Nán Zǐ · Chù Zhēn, the Han Dynasty) |

|

| 3. Biǎo mǒu duàn shíjiān ‘symbolizing a period of time’; yǐlái ‘ever since’. | Wú yòu

lái

zài jiā héng wén rúshì. I childhood since at home constantly hear like-this ‘I’ve been hearing it at home since my childhood.’ (Jìn Shū · ShíLè ZàiJì Shàng, the Tang Dynasty) |

According to Xiandai Hanyu Cidian (7th edition) (2016), when the two lexical items combine to form guòlái, it conveys the directional sense of “moving from another place toward the speaker (or the subject of narration)” (p. 502), explicitly indicating both the path and the endpoint of motion. Remarkably, when guòlái functions as a complement following another verb, it generates implications distinct from those of guò or lái respectively, setting it apart from other complex directional complements (Liu 1998: 16–17). For example, guòlái can indicate a restoration or transformation to a normal or positive state, as in “wǒ míngbái guòlái le ‘I came to understand’”, whereas guò and lái alone cannot convey this meaning. This suggests that the diachronic development of guòlái exhibits the unique semantic characteristics, making it a compelling subject for further investigation.

Since the 1920s, Mandarin directional complements have drawn scholarly attention, with Li’s New Chinese Grammar (1924) serving as an early precursor. Following his work, researchers investigated this issue (e.g., Lyu 1953; Zhang 1953; Chao 1968; Lyu 1980; Li and Thompson 1981; Zhu 1982), albeit not systematically. Since the 1980s, research on directional complements has expanded significantly, developing along multiple lines of inquiry. Firstly, many studies adopted a semantic approach, as seen in works by Meng (1987), Liu (1998), Zhou (1991), Xie and Qi (1999), Cao (2023), among others. Liu (1998) provided a comprehensive semantic analysis that remains influential. Xie and Qi (1999) further examined both the core and extended meanings of the complex directional complements guòlái ‘come over’ and guòqù ‘go over’. The second line of research has focused on syntactic structure, especially the positioning of objects (e.g., Zhang and Fang 1996; Jia 1998; Lu 2002; Yang 2005). Findings reveal that the position of the object depends on factors such as the main verb, context, and the nature of the object. Studies have also examined structural variations in detail, including Zhang’s (1991b) and Yang (2001)’s analyses of “V + C + le” and “V + le + C”, as well as Xiao’s (1992) comparison of “V + lái + N” and “V + N + lái”. From a cognitive perspective, Zeng (2009) offered an innovative study on the syntactic form “V dé (bù) guòlái/guòqù”, identifying three distinct meanings – ability, possibility, and evaluation. More recently, research has shifted toward the acquisition and teaching of complex directional complements, especially in Mandarin as foreign language education, with an emphasis on error analysis and acquisition order (e.g., Xu and Gao 2013; Zhu 2018, Zhu 2019).

Notably, studies have increasingly applied a cognitive perspective to Mandarin directional complements (e.g., Ma 2005; Yang 2017; Cao 2021; Yan and Chen 2021; Xu and Li 2022; Cao 2023). However, few studies have combined the cognitive approach with a diachronic perspective, with notable exceptions including Wu (2003), Wang and Gong (2015, 2018), Li (2018, 2019), Li and Liu (2021). In addition, previous research has primarily focused on simplex directional complements, leaving the diachronic mechanisms underlying the evolution of complex ones unexplored. To address these gaps, the present study delves into the evolution of the Mandarin complex directional complement guòlái ‘come over’, exploring its motivations from a cognitive semantic perspective, especially through the lens of the macro-event framework. The following section provides a detailed discussion of the macro-events and the Macro-event Hypothesis.

3 The macro-events and the Macro-event Hypothesis

According to Talmy (2000b: 213), the “macro-event” is a fundamental and pervasive type of event complex in the conceptual organization of language. It can be conceptualized in two ways: as composed of two simpler events and their relation, or as a single fused event expressed within a single clause. Moreover, Talmy (2000b: 214) proposed 5 types of macro-events: Motion Event, Event of Temporal Contouring, Event of State Change, Event of Action Correlating, and Event of Realization. Table 3 illustrates these categories with examples from both English and Mandarin, including instances where guòlái ‘come over’ is used.

Talmy’s five types of macro-events with examples from English and Mandarin.

| Types | Talmy’s examples | Examples with V guòlái |

|---|---|---|

| Motion event | The ball rolled in. | Wèishēngyuán pǎo

guòlái

. medic run come-over ‘The medic ran over.’ (People’s Daily, 2021) |

| Event of Temporal Contouring | They talked on. | Jǐshínián dōushì zhèyàng xiě

guòlái

. decades always in-this-way write come-over ‘(He) has been written in this way for decades.’ (People’s Daily, 2019) |

| Event of State Change | The candle blew out. | Háizi zhōngyú xǐng

guòlái

. kid finally awake come-over ‘The kid finally woke up.’ (People’s Daily, 2021) |

| Event of Action Correlating | She sang along. | Tā yòu gēn

guòlái

. She again follow come-over ‘She followed over again.’ (Wang Shuo 2012[1992], Guò Bǎ Yǐn Jiù Sǐ) |

| Event of Realization | The police hunted the fugitive down. | Suǒyǐ zhègè quēdiǎn yídìng néng hěnkuài de míbǔ

guòlái

. therefore this shortcoming definitely can quickly remedy come-over ‘Therefore, this shortcoming can definitely be remedied very quickly.’ (People’s Daily, 1951) |

Based on the fundamental concept of the macro-event, Talmy (1985, 1991, 2000a, 2000b) developed his well-known two-way typology: languages that characteristically map the core schema (primarily the Path) of the macro-events into the verb are classified as verb-framed, while those that encode the core schema in the satellite are satellite-framed. He (2000b: 222) further argues that Mandarin Chinese is a satellite-framed language, with verb complements recognized as typical examples. However, when applied to diachronic data in Mandarin, this typology has triggered a heated discussion over the past few decades (e.g., Shen 2003; Shi 2011; Li 2018). Moreover, as highlighted in Section 2, research has rarely focused on Mandarin complex directional complements from the macro-event perspective. Structurally, these complements are formed by combining two simplex directional complements, making them more intricate than simplex ones. This complexity suggests the plausibility of a more elaborate cognitive mechanism underlying their formation.

Beyond Mandarin, Talmy’s typology has faced broader challenges in cross-linguistic applications (e.g., Slobin 2004; Croft et al. 2010; Naidu et al. 2018), which led to the emergence of the Macro-event Hypothesis (Li 2019, 2020, 2023). This hypothesis comprises four continua, three of which, i.e., the semantic continuum, the syntactic continuum, and the grammaticalization continuum, are targeted in the present study, as demonstrated below:

The Macro-event Hypothesis: …This dichotomy might alternatively be viewed as a continuum in several aspects. With corresponding semantic gradations, there might exist syntactic gradations from a double to a single clause representation, and, within the single clause, from less to more grammaticalization of certain constituents… (see Li [2023: 139] for the full account).

The most salient advantage of the Macro-event Hypothesis is its diachronic perspective. Talmy’s two-way typology is essentially based on synchronic data, overlooking typological shifts driven by grammaticalization, such as Mandarin’s evolution from a verb-framed to a predominantly satellite-framed language. By incorporating a diachronic lens, the three continua proposed in the hypothesis offer deeper insights into the inherent complexities of language change. Additionally, the Macro-event Hypothesis presents several other advantages (Li 2023: 139). By employing the unified terms for both form and meaning – Macro-event at the semantic level and clause at the syntactic level – it establishes a concise yet powerful one-to-one mapping between meaning and form. This approach not only resolves disputes concerning the two-way typology but also addresses challenges related to categories like “Satellite” and “Path”, making it a more explanatory and cohesive model. Furthermore, unlike other models of Motion Event typology, which primarily focuses on motion-related constructions, the Macro-event Hypothesis encompasses a broader range of core linguistic constructions, including resultatives, conditionals, and complex sentences with two events. As a result, it provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding event integration in language evolution.

Previous studies have provided preliminary support for one of the continua, i.e., the grammaticalization continuum. For example, Li and Liu (2021) studied the diachronic development of 11 simple directional complements and argued that “a linguistic form that represents a motion event always grammaticalizes the V2 position,” (p. 398) as seen in lái ‘come’ in shǐ lái ‘drive to’, rather than in lái chī ‘come and eat’. This principle is termed the “position and event type hypothesis in grammaticalization.” Furthermore, using diachronic data on the Mandarin causative verb shǐ ‘make’, Liu and Li (2023) traced the semantic shift of shǐ from the send construction to the make construction, driven by event integration. Their findings further support the grammaticalization continuum in language change. However, additional empirical evidence is required to validate this continuum. To justify the Macro-event Hypothesis and determine the evolutionary order of the macro-events in Mandarin directional complement constructions, this study conducts a diachronic corpus-based analysis of the Mandarin complex directional complement guòlái. Employing the measures of frequency and proportion, it aims to explore the syntactic development and the evolutionary order of the macro-events represented by V guòlái from 11th century BCE to the 1920s.

4 Data and methodology

4.1 Corpus and periodization

The analyses are based on the 2014 online version of the Center for Chinese Linguistics Corpus, Peking University (abbreviated as CCL)[2] (Zhan et al. 2003, 2019), a widely used corpus of Chinese containing over 700 million characters. Specifically, the data for this study were drawn from its Classical Chinese sub-corpus, which comprises 163.7 million characters, 41.05 % of which are categorized by dynasties. This dataset spans from the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 BCE) to the early Republican period (1920s), covering a total of 15 dynasties. Following the traditional periodization in Chinese linguistics (e.g., Wang 1957; Li 2004; Guo 2013) and the chronological segmentation used in the CCL, this study clusters the 15 dynasties into five historical stages, following the periodization used by Du and Li (2021) (see Table 4). This periodization reflects characteristics of Mandarin’s phonology, grammar and morphology in each stage and aligns with broader societal changes, providing a structured framework for examining its diachronic evolution.

Periodization of data.

| Stage | Time span | Dynasties |

|---|---|---|

| I: Archaic Chinese | The 11th century BCE – the 3rd century | Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE), Eastern Zhou (770-256 BCE), Han (202 BCE-220) |

| II: Early Middle Chinese | The 3rd century – the 7th century | Six Dynasties (222–589), Sui (581–618) |

| III: Late Middle Chinese | The 7th century – the 13th century | Tang (618–907), Five Dynasties (907–979), Song (960–1279) |

| IV: Early Modern Chinese | The 13th century – the 20th century | Yuan (1271–1368), Ming (1368–1644), Qing (1644–1912) |

| V: Modern Chinese | The 20th century | The Early Period of the Republic of China (1912–1920s) |

4.2 Data collection

Firstly, to closely examine the diachronic development of guòlái ‘come over’, we focused on how the two independent verbs, guò ‘pass’ and lái ‘come’, compounded to form a single lexical unit that further grammaticalized into a complex directional complement. To ensure a maximally inclusive search, we used the pattern “过$10来” (guò $10 lái), which retrieved sentences where the two target words appeared within a span of fewer than 10 characters. In this way, how the two words were combined and further developed could be observed. Finally, 14,524 occurrences were obtained. Given the relatively large number of instances from the Ming Dynasty (N = 2586), Qing Dynasty (N = 8631), and the Early Republican Period (N = 2752), we randomly selected 1,000 occurrences from each period using Python. The resulting dataset was then manually processed to remove semantically unrelated instances. After this refinement, 2,126 sentences were identified as valid data for further analysis (see Table 5).

Frequency of “guò $10 lái” in each stage.

| Stage | Dynasty | Raw dataa | Valid data | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Western Zhou | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Eastern Zhou (the Spring and Autumn Period) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Eastern Zhou (the Warring States Period) | 3 | 0 | ||

| Han (Western Han) | 2 | 0 | ||

| Han (Eastern Han) | 16 | 1 | ||

| II | Six Dynasties | 47 | 1 | 1 |

| Sui | 0 | 0 | ||

| III | Tang | 55 | 11 | 89 |

| Five Dynasties | 38 | 16 | ||

| Song (Northern Song) | 188 | 29 | ||

| Song (Southern song) | 109 | 33 | ||

| IV | Yuan | 97 | 68 | 1470 |

| Ming | 1000 (Random) | 669 | ||

| Qing | 1000 (Random) | 733 | ||

| V | The Early Republican Period | 1000 (Random) | 564 | 564 |

| Total | 3555 | 2126 | ||

-

a‘Raw data’ refers to the entire dataset retrieved using the search pattern before any manual filtering, including all sampled instances of the target structure, regardless of their semantic relevance.

Secondly, to investigate the evolutionary order of the macro-events represented by the V guòlái construction, data points of this form were retrieved. Since the corpus data have not yet been segmented or annotated, the present data utilized the query of “过来” (guòlái) and manually processed the extracted occurrences, totaling 7,467.

During manual processing, the syntactic structures of V guòlái with objects proved to be a point of debate. As summarized by Zhang (1991a, 1991b), four syntactic forms of “C3-11 C1-2 (= the complex directional complements)” (see Table 1) involving objects have been identified:

A: V C3-11 C1-2 O (e.g., ná guòlái tā ‘bring it over’)

B: V C3-11 O C1-2 (e.g., ná guò tā lái ‘bring it over’)

C: V O C3-11 C1-2 (e.g., ná tā guòlái ‘bring it over’)

D: bǎ O V C3-11 C1-2 (e.g., bǎ tā ná guòlái ‘bring it over’)

To ensure the accuracy, we adopt Yang’s (2005) claim that these syntactic structures reflect different cognitive patterns and adhere to the principle of temporal sequence (Dai and Huang 1988). This principle states that the relative order of two syntactic units is determined by the temporal sequence of states they represent in the conceptual domain. In Yang’s analysis, only in the V C3-11C1-2 O structure is the complex directional complement fully grammaticalized, as it conceptualizes V C3-11C1-2 as a unified whole. For example, in ná guòlái tā ‘bring it over’, ná guòlái ‘bring over’ represents the entire movement process, while tā ‘it’ serves as the theme of this movement. In contrast, in other structures, V and C3-11 C1-2 are interpreted as separate cognitive units, with C3-11C1-2 functioning as a directional verb rather than a grammaticalized complement. Therefore, these structures are better classified as serial verb constructions, where V and C3-11C2 operate as two independent verbs with no grammatical dependency between them. Specifically, V O C3-11C1-2 is considered the most typical serial verb construction. In the expression ná tā guòlái ‘bring it over’, the action of ná tā ‘take it’ occurs first, followed by the movement guòlái ‘come over’, making it a clear example of a serial verb construction. Similarly, V C3-11 O C1-2 is also classified as a serial verb construction (see Wang [1989]), as V C3-11 O (ná guò tā ‘take it’) and (O) C1-2 ([tā] lái ‘it comes’) represent two sequential actions, though this structure is less typical. Finally, the cognitive pattern of bǎ O V C3-11C1-2, falling under disposal constructions, is similar to that of V O C3-11 C1-2, as exemplified by Guō Yīng bǎ Wáng Dǐng huóqín guòlái ‘Guo Ying has captured Wang Ding alive and brought him over’. In this example, bǎ Wáng Dǐng huóqín ‘captured Wang Ding alive’, which can be paraphrased as the VO order huóqín Wáng Dǐng, represents the initial action, while guòlái ‘come over’ follows as the subsequent event. This sequential structure aligns with the cognitive pattern of V O C3-11 C1-2, where C3-11C1-2 functions as a directional verb.

Based on the criteria, the present study considers only Form A as valid and excluded data from the other three syntactic structures to avoid ambiguity. Occurrences of “jiāng O V guòlái” were also removed, as this pattern can be seen as an alternate of Form D (Liu and Cuyckens 2023). Moreover, instances of “V dé/bù guòlái” were excluded to prevent ambiguity, as this structure serves a different semantic and functional role from V guòlái. Specifically, V dé/bù guòlái expresses the notion of ability or inability, as in ná dé/bù guòlái ‘have/not have the ability to bring over’, rather than simply denoting directional movement. Finally, 1,406 occurrences remained, as seen in Table 6.

Frequency of V guòlái in each stage.

| Stage | Dynasty | Raw data | Valid data | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Western Zhou | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eastern Zhou (the Spring and Autumn Period) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Eastern Zhou (the Warring States Period) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Han (Western Han) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Han (Eastern Han) | 0 | 0 | ||

| II | Six Dynasties | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sui | 0 | 0 | ||

| III | Tang | 6 | 1 | 11 |

| Five Dynasties | 7 | 1 | ||

| Song (Northern Song) | 18 | 8 | ||

| Song (Southern song) | 14 | 1 | ||

| IV | Yuan | 46 | 10 | 774 |

| Ming | 1025 | 342 | ||

| Qing | 5110 | 422 | ||

| V | The Early Republican Period | 1241 | 621 | 621 |

| Total | 7467 | 1406 | ||

4.3 Data analysis

This study adopts a data-driven approach to explore the diachronic syntactic development of guòlái ‘come over’. It traces the syntactic forms relevant to guòlái in terms of frequency and distribution across five stages. Furthermore, by calculating the occurrence frequency of the macro-event types represented by V guòlái in each stage, this study seeks to identify their evolutionary order.

5 Results

5.1 The syntactic development of guòlái ‘come over’

This section focuses on the diachronic development of the syntactic structures associated with the varied usages of guòlái ‘come over’ in each stage. Since only two relevant occurrences were found in the first two stages, it is reasonable to argue that guòlái, or even its earliest form, had not yet become entrenched. From Stage III onward, the frequency of occurrences increased, marking the starting point of our analysis. This observation also corresponds to the findings of Li (2019).

5.1.1 Overall trend

Through data-driven coding, we identified 20 types of syntactic structures associated with guòlái ‘come over’ across all occurrences, as exemplified in Table 7.

20 types of syntactic structures of guòlái from Stage I to Stage V.

| Types | Structures | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A | guò (N)…(bù) lái V/N | Tōu lù ér guò, …lái dào jīnlíngjiāng àn. sneak-down path and pass come arrive JinLing-river bank (Xiao Mo He) passed by sneaking down the path…came and arrived at the bank of Jin Ling River. |

| B | guò N (ér) lái | Zhǔrén guò qiáo lái, … master cross bridge come The master crossed the bridge and came (to visit) … |

| C | guò N lái (N) V | Guò jiāng lái tóu. cross river come seek-shelter (They) crossed the river and came to seek shelter. |

| D | V guò (N)…lái V/N | Fúzi zǒu guò xītiān, què lái xīnluóguó lǐ. whisk walk past the-West but come Silla inside The whisk walked past the West but came to Silla. |

| E | guòlái | Niānqǐ mùqiáo yuē: “guòlái.” pick-up wooden-bridge say come-over (The Zen master) picked the wooden bridge up and said: “come over.” |

| F | guò dé (N) lái | Wǒ rúhé guò dé lái. I how live AUX come How can I live it through? |

| G | guò bù lái | Biànshì nánzǐ, yě dúzì guò bù lái. even men also independent live NEG come Even men cannot live it through independently. |

| H | V guòlái | Liánmáng jiē guòlái. promptly take come-over (He) promptly took (her) over. |

| I | V le guòlái | Liánmáng pǎo le guòlái. quickly run PFV come-over (Xue Pan) quickly ran over. |

| J | V dé guòlái | Nǎlǐ néng chōngshā dé guòlái. How could (the invaders) have the ability to charge over? |

| K | V bù guòlái | Qì dōu tòu bù guòlái. air ADV get NEG come-over (Zhang Qiugu) cannot breathe. |

| L | V N guòlái | Ná qízǐ guòlái… take pieces come-over Take the pieces over… |

| M | V le N guòlái | Biàn qǔ le mǎbiān guòlài. then take PFV horsewhip come-over Then (he) took the horsewhip over. |

| N | V zhe N guòlái | Qiàhǎo mǎsǎoér qí zhe gè lǘzǐ guòlái. just Mrs.Ma ride PROG QUAN donkey come-over Mrs. Ma just came over riding a donkey. |

| O | V guò N lái | …Děng wǒ qǔ guò jūnlìngzhuàng lái. wait I-OBJ bring past military-order come Wait for me to bring over the military order. |

| P | V bù guò N lái | Mǎchē yīshíjiān zhuǎn bù guò shēn lái. carriage suddenly turn NEG past body come The carriage could not turn over suddenly. |

| Q | bǎ N V guòlái | …Bǎ shēnzi zhí pū guòlái. PREP body directly pounce come-over (A pig) directly pounced towards (Emperor Shun). |

| R | jiāng N V guòlái | Jiāng xiùqiú qǔ guòlái. PREP embroidered-ball bring come-over (The Princess) brought a embroidered ball over… |

| S | V jiāng guòlái | Chōng jiāng guòlái. rush AUX come-over (Beasts) rushed over. |

| T | guòlái dè/(zhī)rén | Èrrén dōushì guòláizhīrén… the-two both experienced-people The two have both been there… |

Table 8 presents the detailed information on the frequency of each structure across five stages, illustrating the evolution of these syntactic patterns over time. Notably, the absence of guò N lái (N) V, guò bù lái, and V de guòlái in Stage V may be attributed to variations in data diversity across different dynasties.

The distribution of different structures from Stage I to Stage V.

| Types | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | Stage V | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 17 |

| B | 0 | 1 | 26 | 23 | 2 | 52 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 16 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 9 | 26 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 25 | 313 | 78 | 417 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| G | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| H | 0 | 0 | 11 | 351 | 204 | 566 |

| I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 42 | 72 |

| J | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| K | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 24 |

| L | 0 | 0 | 4 | 138 | 47 | 189 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 8 | 23 |

| N | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| O | 0 | 0 | 8 | 408 | 100 | 516 |

| P | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Q | 0 | 0 | 1 | 51 | 15 | 67 |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| S | 0 | 0 | 1 | 58 | 19 | 78 |

| T | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Sum | 1 | 2 | 89 | 1470 | 564 | 2126 |

The three most frequently used syntactic structures are Type H, V guòlái, Type O, V guò N lái, and Type E, guòlái. Type O represents one of the syntactic forms of complex directional complements involving objects. Its high frequency in our data aligns with previous findings, which indicate that this form is the most frequently used and the least constrained, as it adheres to both syntactic and prosodic rules (Dong 1998). Diachronically, Type B, guò N (ér) lái, where guò and lái function as independent verbs, was frequently used in Stage III but gradually declined, giving way to usages characterized by Type E, guòlái, and Type H, V guòlái, along with their variations. In contrast, V guòlái was rarely used in Stage III but increased in frequency in Stages IV and V. By Stage V, V guòlái had become the most dominant form, confirming its entrenchment as a complex directional complement. Furthermore, by this stage, more than half of the syntactic structure types were related to V guòlái, demonstrating its widespread use. This trend further illustrates the progressive grammaticalization of guòlái over time.

Having examined the syntactic forms of guòlái from a broad perspective, we explore its development in greater detail across each stage.

5.1.2 Stage III

At Stage III, although the dataset is smaller compared to later periods, there is a noticeable increase in occurrences relative to earlier stages. The syntactic structures identified in Stage III are presented in Table 9.

The distribution of different structures in Stage III.

| Types | Structures | Sum | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | guò N (ér) lái | 26 | 29.21 % |

| E | guòlái | 25 | 28.09 % |

| G | V guòlái | 11 | 12.36 % |

| A | guò (N)…(bù) lái V/N | 8 | 8.99 % |

| O | V guò N lái | 8 | 8.99 % |

| C | guò N lái (N) V | 4 | 4.49 % |

| L | V N guòlái | 4 | 4.49 % |

| D | V guò (N)…lái V/N | 1 | 1.12 % |

| Q | bǎ N V guòlái | 1 | 1.12 % |

| S | V jiāng guòlái | 1 | 1.12 % |

| 89 | 100 % |

According to Table 9, Type B, guò N (ér) lái, is prevalent at this stage, where guò and lái function as independent verbs denoting motion (e.g., [1]). The first event, guò N signifies movement across a location, while the second event, ér lái, demonstrates the action of approaching an endpoint.

| Dámó | dàshī | cóng | nántiānzhúguó | guò | hǎi | ér | lái. |

| Dharma | Master | from | Southern-Tianzhu-Kingdom | across | sea | and | come |

| ‘Master Dharma came across the sea and arrived here from the Southern Tianzhu Kingdom.’ | |||||||

| (Zu Tang Ji, the Five Dynasties) | |||||||

The second most frequent structure is Type E, guòlái, in which guò and lái function collectively to signify the act of approaching or arriving at a specific location, as exemplified in (2). In this context, the meaning of guò is comparatively subordinate to that of lái, which emphasizes proximity to the reference point. For example, in (2), if lái is deleted, the sentence instead conveys the meaning of “the creditor passing (a place)”. Regardless of whether guòlái is used as a serial verb construction or an independent verb at this stage, its syntactic relationship has become more closely bounded, with speakers increasingly using guò and lái together to denote a unified, integrated event, i.e., a macro-event.

| Zhàizhǔ | zàn | guòlái . |

| Creditor | momently | come-over |

| ‘The creditor came over momently.’ | ||

| (Tang Shi, the Tang Dynasty) | ||

The emergence of Type G, V guòlái, further supports this point, as guòlái started to serve as a complex complement following the main verb, reinforcing the increased syntactic tightness between guò and lái. For example, in (3), guòlái functions as a complement to encode the core schema, [path], while the main verb, qīn ‘invade’, represents the [manner] of the Motion Event. However, despite its structural significance, V guòlái accounts for only slightly more than 10 % of the total instances, indicating that its use as a complex directional complement was not yet widespread at this stage.

| Ruò | zhèbiān | gōngfū | shǎo, | nàbiān | bì | qīn | guòlái. |

| If | this-side | effort | less | that-side | must | invade | come-over |

| ‘If this side has less effort, that side must invade it.’ | |||||||

| (Zhu Zi Yu Lei, the Northern Song Dynasty) | |||||||

Overall, the frequency distribution suggests a preliminary evolutionary path wherein guòlái transitions from its earlier use in guò N (ér) lái ‘passing through a location and coming’ to functioning as a directional verb, eventually undergoing grammaticalization as a complex directional complement denoting “come over”. This shift also reflects the combination of two discrete clauses into a unified, single clause. It is worth noting that the frequency of derivatives of V guòlái remains relatively low at this stage, indicating that its development as a complex directional complement was still in its early phase.

5.1.3 Stage IV

This stage accounts for the majority of the data, warranting a thorough examination. According to Chinese Linguistics (Li 2004), the language from this period is considered foundational for modern Chinese. The surge in data can be attributed to the rise of colloquialism during this era. Table 10 presents the frequency and proportion of all syntactic structures, revealing the emergence of 10 additional types compared to Stage III. A higher degree of grammaticalization and entrenchment of guòlái is evident at this stage, as guòlái and V guòlái can accept various intervening linguistic elements, including tense markers such as zhē (the progressive marker) (see Type N) and lē (the perfect marker) (see Type I, M), negation marker bù (see Type K, P, G), and auxiliaries dé (see Type F, J) and jiāng (see Type S).

The distribution of different structures in Stage IV.

| Types | Structures | Dynasty | Frequency | Sum | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | V guò N lái | Yuan | 20 | 408 | 27.76 % |

| Ming | 270 | ||||

| Qing | 118 | ||||

| H | V guòlái | Yuan | 10 | 351 | 23.88 % |

| Ming | 150 | ||||

| Qing | 191 | ||||

| E | guòlái | Yuan | 9 | 313 | 21.29 % |

| Ming | 62 | ||||

| Qing | 242 | ||||

| L | V N guòlái | Yuan | 20 | 138 | 9.39 % |

| Ming | 72 | ||||

| Qing | 46 | ||||

| S | V jiāng guòlái | Yuan | 1 | 58 | 3.95 % |

| Ming | 37 | ||||

| Qing | 20 | ||||

| Q | bǎ N V guòlái | Yuan | 0 | 51 | 3.47 % |

| Ming | 10 | ||||

| Qing | 41 | ||||

| I | V le guòlái | Yuan | 0 | 30 | 2.04 % |

| Ming | 7 | ||||

| Qing | 23 | ||||

| B | guò N (ér) lái | Yuan | 2 | 23 | 1.56 % |

| Ming | 17 | ||||

| Qing | 4 | ||||

| D | guò (N)…lái V/N | Yuan | 1 | 16 | 1.09 % |

| Ming | 9 | ||||

| Qing | 6 | ||||

| M | V le N guòlái | Yuan | 0 | 15 | 1.02 % |

| Ming | 4 | ||||

| Qing | 11 | ||||

| K | V bù guòlái | Yuan | 0 | 14 | 0.95 % |

| Ming | 6 | ||||

| Qing | 8 | ||||

| C | guò N lái (N) V | Yuan | 0 | 12 | 0.82 % |

| Ming | 8 | ||||

| Qing | 4 | ||||

| R | jiāng N V guòlái | Yuan | 0 | 8 | 0.54 % |

| Ming | 3 | ||||

| Qing | 5 | ||||

| F | guò dé (N) lái | Yuan | 0 | 7 | 0.48 % |

| Ming | 6 | ||||

| Qing | 1 | ||||

| J | V dé guòlái | Yuan | 1 | 6 | 0.41 % |

| Ming | 1 | ||||

| Qing | 4 | ||||

| N | V zhe N guòlái | Yuan | 2 | 6 | 0.41 % |

| Ming | 3 | ||||

| Qing | 1 | ||||

| A | guò (N)…(bù) lái V/N | Yuan | 0 | 5 | 0.34 % |

| Ming | 3 | ||||

| Qing | 2 | ||||

| T | guòlái dè/(zhī)rén | Yuan | 2 | 5 | 0.34 % |

| Ming | 1 | ||||

| Qing | 2 | ||||

| P | V bù guò N lái | Yuan | 0 | 3 | 0.20 % |

| Ming | 0 | ||||

| Qing | 3 | ||||

| G | guò bù lái | Yuan | 0 | 1 | 0.07 % |

| Ming | 0 | ||||

| Qing | 1 | ||||

| 1470 | 100.00 % |

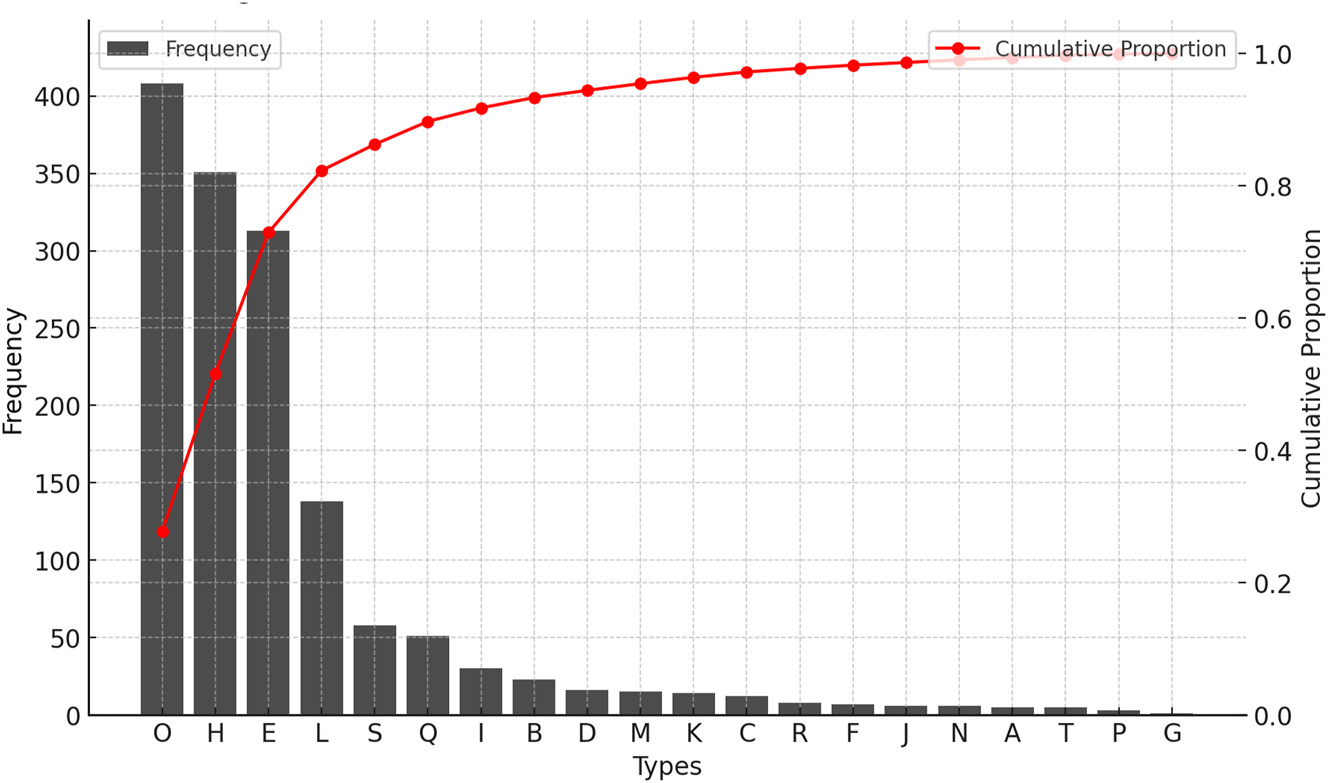

To better illustrate this trend, the frequency and distribution of data at Stage IV are visualized in Figure 1.

The frequency and cumulative proportion of each type in Stage IV.

According to Figure 1, three types – Type O, V guò N lái (cf. [4]), Type H, V guòlái (cf. [3]), and Type E, guòlái (cf. [2]) – exhibit higher frequencies, collectively accounting for nearly 75 % of the data in this stage. Notably, V guò N lái emerges as the most prevalent usage during this period, reaching its peak in the Ming Dynasty. As discussed in Section 4.2, this form is considered one of the derivations of V guòlái that involves the object, further supporting the higher syntactic tightness between guò and lái. For example, in (4), qǔ guò shū represents Event 1, denoting the action of “taking the book”, where the displacement applies to the book rather than the agent. Event 2, marked by lái, represents the agent’s movement of “carrying the book to the reference point”. Rather than being expressed in two separate clauses, these two events are integrated into a single clause, validating the syntactic continuum proposed in the Macro-event Hypothesis.

| Jīng | Gōng | qǔ | guò | shū | lái. |

| Jing | Gong | take | come | book | over |

| ‘Jing Gong took the book over.’ | |||||

| (Yuan Dai Hua Ben Xuan Ji, the Yuan Dynasties) | |||||

Unlike V guò N lái, both V guòlái and guòlái exhibit a consistent upward trend over time, reflecting their increasing entrenchment and conventionalization. Furthermore, the proportion of V guòlái surpasses that of guòlái, indicating the gradual establishment of guòlái as a complex directional complement rather than as an independent verb.

5.1.4 Stage V

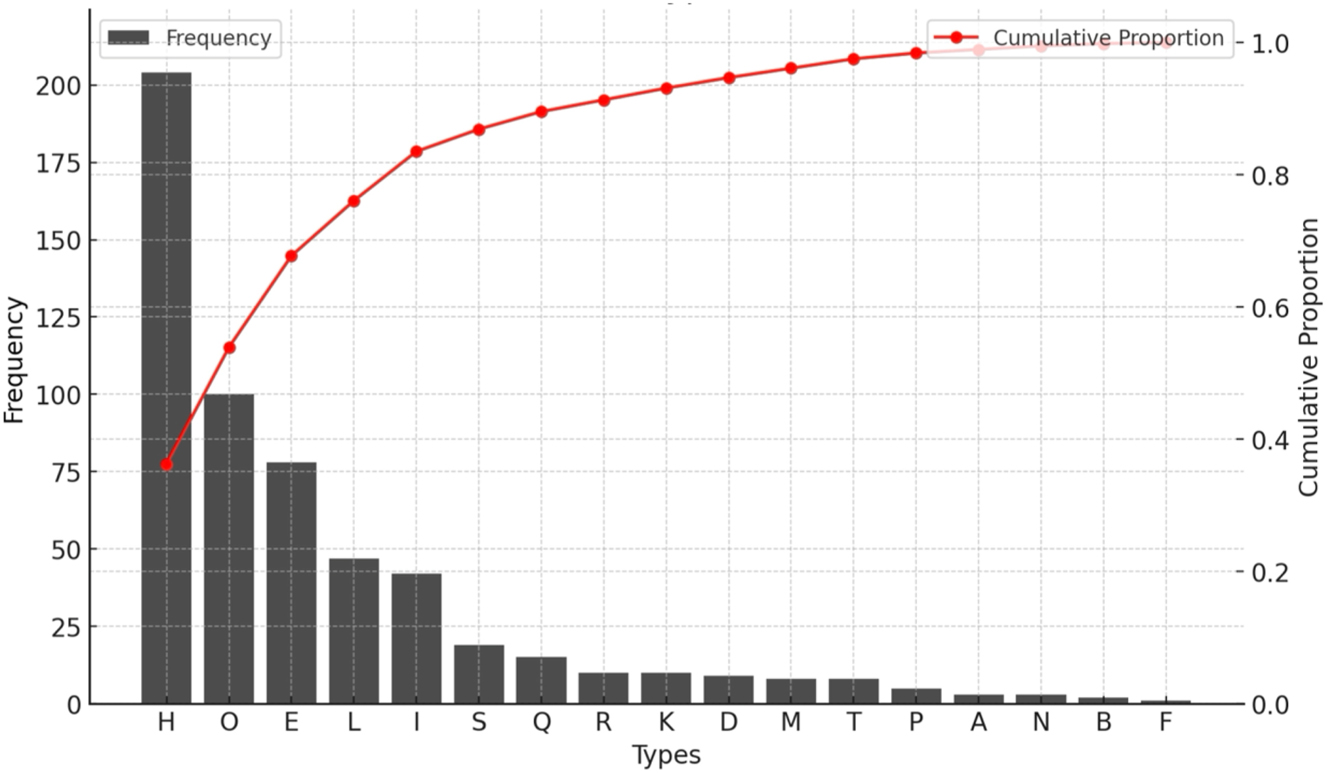

Although this stage covers a relatively short period, the data closely resemble modern Chinese. In addition, the dataset contains over five hundred instances, suggesting the widespread use of guòlái. The frequency and distribution of each syntactic structure are shown in Table 11 and visualized in Figure 2.

The distribution of different structures in Stage V.

| Types | Structures | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | V guòlái | 204 | 36.17 % |

| O | V guò N lái | 100 | 17.73 % |

| E | guòlái | 78 | 13.83 % |

| L | V N guòlái | 47 | 8.33 % |

| I | V le guòlái | 42 | 7.45 % |

| S | V jiāng guòlái | 19 | 3.37 % |

| Q | bǎ N V guòlái | 15 | 2.66 % |

| K | V bù guòlái | 10 | 1.77 % |

| R | jiāng N V guòlái | 10 | 1.77 % |

| D | V guò (N)…lái V N | 9 | 1.60 % |

| M | V le N guòlái | 8 | 1.42 % |

| T | guòlái dè/rén (adjective) | 8 | 1.42 % |

| P | V bù guò N lái | 5 | 0.89 % |

| A | guò (N)…(bù) lái V/N | 3 | 0.53 % |

| N | V zhe N guòlái | 3 | 0.53 % |

| B | guò N (ér) lái | 2 | 0.35 % |

| F | guò dé (N) lái | 1 | 0.18 % |

| 564 | 100.00 % |

The frequency and cumulative proportion of each type in Stage V.

Drawing insights from the data, it is strikingly evident that Type H, V guòlái, now dominates the overall distribution. Its proportion has steadily increased over time, rising from 12.36 % to 23.88 % and then to 36.17 %, further reinforcing the higher degree of grammaticalization of guòlái as a complex directional complement. In contrast, Type E, guòlái, exhibits the opposite trend, with its proportion decreasing from Stage III to V (28.09 % to 21.29 % to 13.83 %), indicating a shift in guòlái’s function from an independent verb to a complement. Remarkably, Type B, from which guòlái originated, now appears in only two instances, which supports the hypothesis that its syntactic evolution has progressed from separate clauses to a single clause rather than the reverse. Finally, with its increased degree of grammaticalization, guòlái exhibits greater flexibility and versatility in usage. Particularly noteworthy is the prevalence of object-involving constructions derived from V guòlái, such as Type O and Type L, as evidenced by their increasing frequency and proportion.

5.2 The semantic development of the V guòlái construction: the evolutionary order of the macro-events

This section delves deeper into the development of the V guòlái construction from the macro-event perspective. While its structural composition has remained stable since its emergence, the onset of grammaticalization marked a notable expansion in its semantic scope. Over time, V guòlái began to convey a broader range of meanings, initiating its grammaticalization journey. These semantic developments can be roughly categorized into five types of the macro-events.

By tracing the evolutionary sequence of the macro-events represented by this construction, this study aims to provide a cognitive framework that contributes, to some extent, to our understanding of the evolution of Mandarin. Given the absence of valid data from Stage I and II, we tentatively posit the emergence of guòlái as a directional complement at Stage III. This finding aligns with previous research in Chinese linguistics such as Wang (2005: 186), which identifies the Song Dynasty as the period of its emergence.

5.2.1 Stage III

As V guòlái itself is a directional complement construction, its prototypical function of expressing spatial orientation makes the Motion Event the earliest and most frequent macro-event type represented by this construction. In this usage, guòlái functions as a satellite encoding the core schema [path], while the main verb V encodes [manner]. For example, in (3), the main verb qīn ‘invade’ conveys the manner of the movement, and the complement guòlái makes explicit the route, i.e., from far to the reference point. Additionally, a notable expansion in its meaning occurred, where V guòlái began to signify Events of Realization, as exemplified in (5):

| shì | tā | céng | jīnglì | guòlái. |

| is | he | already | experience | come-over |

| ‘He has already experienced.’ | ||||

| (Zhu Zi Yu Lei, the Northern Song Dynasty) | ||||

Nevertheless, it is imperative to acknowledge the limited availability of data from this period, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. In Stage III, only 5 occurrences of Realization Events were recorded (Table 12).

The distribution of the macro-event types in Stage III.

| Types | Tang | Five dynasties | Song (Northern song) | Song (Southern song) | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Temporal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State Change | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correlating | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Realization | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 11 |

5.2.2 Stage IV

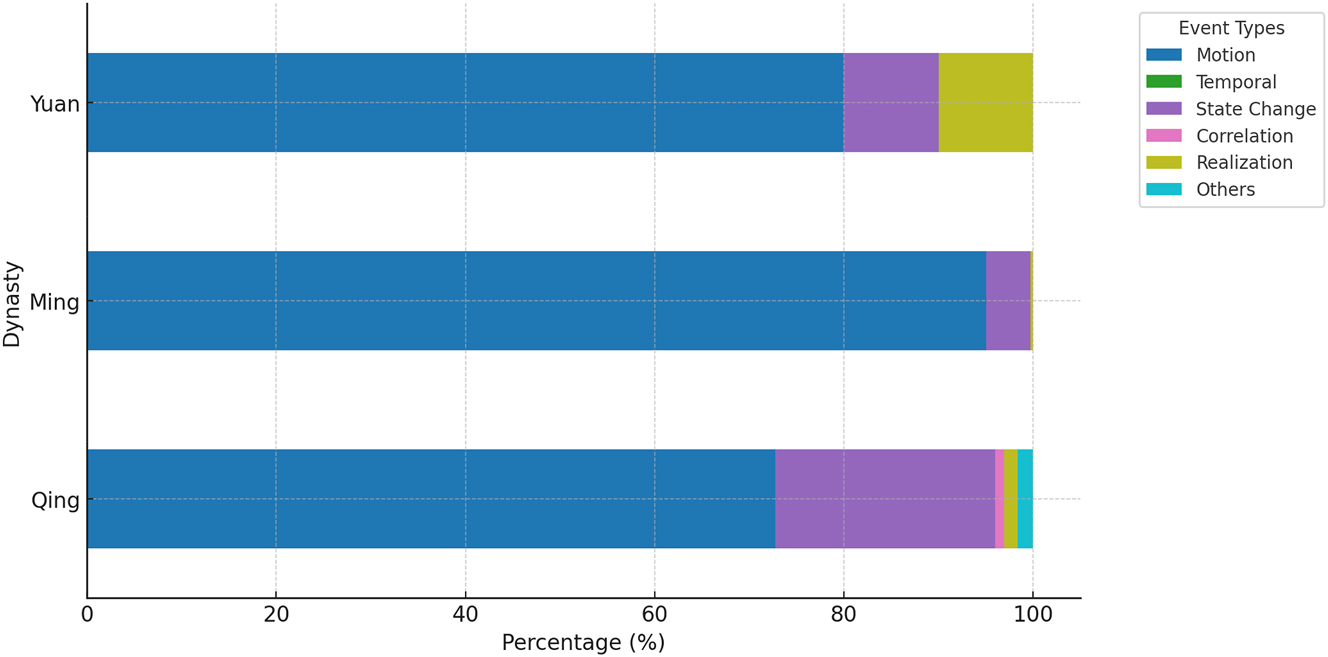

During this stage, the usage of the V guòlái construction surged. The corresponding distribution is presented in Table 13, with a visual representation in Figure 3.

The distribution of the macro-event types in Stage IV.

| Types | Yuan | Ming | Qing | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | 8 | 325 | 307 | 640 |

| Temporal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State Change | 1 | 16 | 98 | 115 |

| Correlating | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Realization | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 10 | 342 | 422 | 774 |

The comparison of distribution in each dynasty in Stage IV.

It is noteworthy that the macro-event types represented by V guòlái became increasingly diverse over time, as illustrated in Figure 3 by the growing variety of colors, confirming its expanding semantic scope. In addition, this construction started to represent events that do not fit into the established five macro-event types, a trend particularly evident during the Qing dynasty. These instances have been collectively categorized as “Others”, encompassing expressions such as huíxiǎng guòlái ‘reminiscing about something’, fǎn guòlái ‘in turn’. A more detailed discussion of these cases is provided in Section 6.1.

Despite this diversification, Motion Events remain the most prevalent category across all dynasties, which aligns with the inherent directional nature of V guòlái. Notably, the Event of State Change (cf. [6]) has witnessed a consistent rise in proportion, as illustrated by the expanding grey segments in Figure 3. This trend suggests that guòlái has developed the capacity to denote changes beyond mere physical displacement, such as marking a transition from the state of being asleep to being awake, as illustrated in (6). It is pertinent to observe that, as of this analysis, the Temporal Contouring Events have yet to appear in the dataset.

| Tiān | Shī | xǐng | guòlái. |

| Tian | Shi | awake | come-over |

| ‘Tian Shi woke up.’ | |||

| (San Bao Tai Jian Xi Yang Ji, the Ming Dynasty) | |||

5.2.3 Stage V

Similarly, the diverse macro-events observed in Stage V are succinctly summarized in Table 14. The distribution pattern closely mirrors that of the Qing Dynasty, with Motion Events remaining the most dominant, followed by State Change events. Notably, the Event of Temporal Contouring remains conspicuously absent in this period as well.

The distribution of macro-event types in Stage V.

| Types | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Motion | 485 |

| Temporal | 0 |

| State Change | 126 |

| Correlating | 2 |

| Realization | 2 |

| Others | 6 |

| Total | 621 |

5.2.4 Overall trend

In conclusion, a comparative analysis of the distribution of the macro-event types across stages is undertaken, offering insights into the potential evolutionary order of macro-events encapsulated by the V guòlái construction (Table 15).

The distribution of macro-event types from Stage III to Stage V.

| Types | Stage III | Stage IV | Stage V | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | 6 | 640 | 485 | 1131 |

| Temporal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State Change | 0 | 115 | 126 | 241 |

| Correlating | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Realization | 5 | 8 | 2 | 15 |

| Others | 0 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Total | 11 | 774 | 621 | 1406 |

Based on the data analysis, Motion Events consistently dominate each stage, reinforcing the prototypical nature of V guòlái as a directional complement construction. Intriguingly, while Events of Realization made an early appearance, their proportional representation has dwindled over time, whereas Events of State Change have exhibited a steady increase in diachronic usage. Meanwhile, Events of Temporal Contouring remain entirely absent. However, since the analysis only includes data up to the Early Republic Period, and Section 3 identified examples of the Event of Temporal Contouring in the contemporary subpart of the CCL corpus, we propose the following hypothesized developmental trajectory of macro-events: Motion Event > Event of Realization > Event of State Change / Event of Action Correlating (> Event of Temporal Contouring). Additionally, the macro-events that fall outside the established five types warrant further attention, as they challenge the classification framework proposed by Talmy (2000b).

6 Discussions

The current study provides significant insights into the diachronic evolution of the Mandarin complex directional complement guòlái from two perspectives: syntactic structures and the macro-event types, or more broadly, form and meaning.

6.1 The syntactic development of guòlái ‘come over’

From a syntactic perspective, the findings indicate that guòlái, originally conceived as a motion verb, derives from the pattern guò N (ér) lái, where guò and lái functioned as two separate motion verbs. Over time, it underwent grammaticalization, ultimately becoming a directional complement in the form of V guòlái. With a higher degree of grammaticalization, V guòlái has developed the ability to co-occur with various intervening elements, including the Chinese tense marker zhē and lē, the negation marker bù, and the auxiliaries dé and jiāng. It also allows for intervening objects, as seen in structures such as V N guòlái and V guò N lái. Furthermore, guòlái can appear in disposal constructions, including those introduced by bǎ and jiāng.

The syntactic development of guòlái aligns with the syntactic continuum observed in the transition from a double-clause to a single-clause representation. This progression supports the grammaticalization continuum proposed in the Macro-event Hypothesis (Li 2023: 139). For instance, during Stage III, guò and lái functioned as two distinct independent verbs (cf. [1]). By Stage IV, the combined usage of guòlái had significantly increased, predominantly conveying the meaning of “come over”. Importantly, the concept of “passing through a location and arriving at a reference point” became encapsulated within a single clause through the use of guòlái, as exemplified in (7):

| Shícháng | guòlái | zǒuzǒu. |

| Often | come-over | visit |

| ‘Please often come over and visit us.’ | ||

| (Yuan Dai Hua Ben Ji Xuan, Stage IV) | ||

Ultimately, when combined with another verb signifying the manner of movement, guòlái undergoes grammaticalization, transforming into a directional complement, as illustrated in (8):

| Jiàn | yòu | yǒu | liǎnggè | gōngnǚ | cóng | chuáng | qián | zǒu |

| See | again | have | two-PL | maid | from | bed | front | walk |

| guòlái | ||||||||

| come-over | ||||||||

| ‘(Yuan Zhang) saw that two more maids walked over from the bed.’ | ||||||||

| (Ming Dai Gong Wei Shi, Stage V) | ||||||||

The examples above demonstrate that, during the development of V guòlái, two distinct events – “passing by a place” and “moving closer to the reference point” – have been diachronically conceptualized as a single, integrated event: “come over.” This development is further reinforced by the incorporation of manner verbs, all encapsulated within a single clause. This observation aligns with the syntactic continuum proposed in the Macro-event Hypothesis.

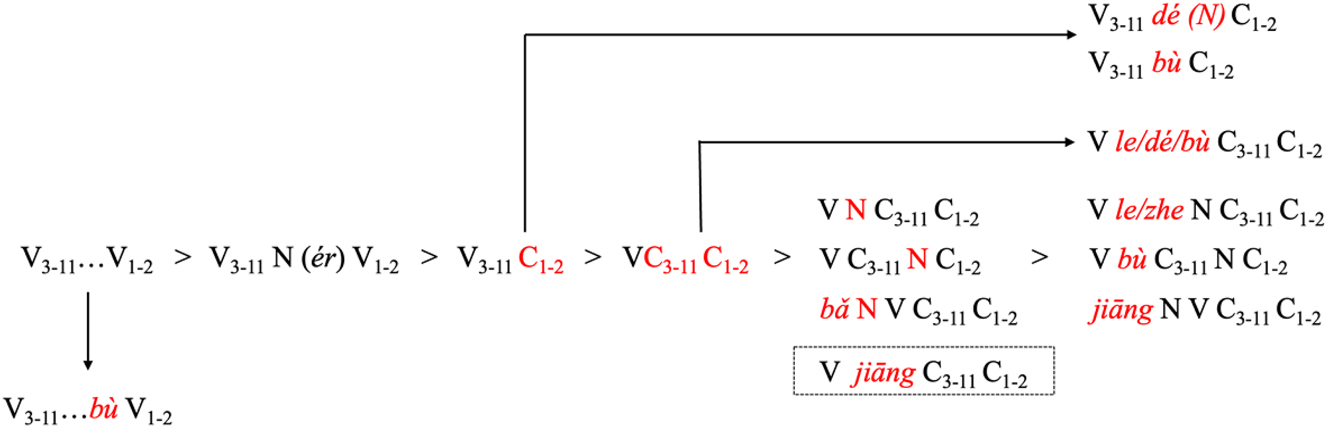

Drawing upon the developmental sequence of guòlái, a broader schema for the syntactic evolution of all complex directional complements can be proposed (cf. Figure 4), providing support for the syntactic and grammaticalization continua outlined in the Macro-event Hypothesis.

The syntactic evolutionary sequence of Mandarin complex directional complements.

6.2 The semantic evolution of V guòlái construction

Concerning the macro-event types represented by V guòlái over time, this study hypothesizes its evolutionary order as Motion Event > Event of Realization > Event of State Change / Event of Action Correlating (> Event of Temporal Contouring). The sequence corresponds partially to Zhang (1991b), who posits that the “directional meaning” (Motion Event) of complex directional complements has bleached to resultant meaning (Event of Realization), and to state meaning (Event of State Change) throughout the process of linguistic evolution (p.185). However, it is slightly different from that raised by Li (2019), which illustrates the development path as Motion Event > Event of State Change > Event of Temporal Contouring > Event of Realization by examining the 11 simplex directional complements. The differences can be explained as follows. Firstly, the present study only explores one complex directional complement, guòlái, and the final development process may largely result from its own unique characteristics. Secondly, presenting the Event of Realization is the second step of the evolution, which may be due to the meaning of accomplishment expressed by guò ‘pass’. In addition, since data is limited, it is hard to decide the appearance order of the Event of State Change and the Event of Action Correlating. Therefore, the hypothesized sequence is only tentative and needs support from future studies.

Remarkably, the Event of Temporal Contouring did not appear throughout the whole process. Even though we identified relevant occurrences in the contemporary Chinese corpus included by CCL that are beyond the scope of our discussion, these instances are few in comparison to other types of macro-events and they are not typical examples compared to those proposed by Talmy (2000b). Most of them denote a Temporal Contouring Event with a specific focus on the progression from the past to the present, rather than from the present to the future. This can be explained by the basic directional meaning of guòlái. Liu (1998) argues that guòlái indicates an object moving closer to the standpoint of the speaker. Zhang (2010) and Wang (2005) also demonstrated that guòlái expresses the direction of the move, i.e., to the speaker. Therefore, metaphorically, it refers to a target moving from the past to now (the speaker), rather than from now to the future, such as in xiě guòlái “have/has been written”. It is possible that the event of “write” continues, but it is not the pivot. However, the activating process of the Event of Temporal Contouring emphasizes the target’s “progression through time” (Talmy 2000b: 231), which is in nature opposite to the event presented by V guòlái. Thus, Talmy’s Temporal Contouring Event should be revised to explain this language phenomenon.

Furthermore, there are instances that cannot be categorized into the five types of macro-events. For example, the above example of xiǎng guòlái ‘reminiscing about sth.’ or huíxiǎng guòlái ‘reminiscing about’, as well as fǎn guòlái ‘in turn’ or dào guòlái ‘in turn’ in its idiomatic usage, meaning ‘reversely’ or ‘in contrary’, as shown by (9). They cannot be classified into any discernible type, which impedes the refinement of the existing macro-event types.

| Tā | diào | guòlái | biàn | rùle | Mǎn Gǔ Er Tài | dè |

| She | turn | come-over | then | join-PFV | Mang Gu Er Tai | POSS |

| dǎng | ||||||

| party | ||||||

| ‘She, in turn, joined Mang Gu Er Tai’s party.’ | ||||||

| (Qing Dai Gong Ting Yan Shi, Stage V) | ||||||

Moreover, through data annotation, it is doubtful that whether the core schema of the Event of State Change is expressed by the verbs or by the satellite guòlái. For example, (1) verbs indicating ‘awake’, such as xǐng, jīngxǐng, qīngxǐng; (2) verbs indicating ‘understand’ including wù, juéwù, míngbái, lǐjǐe; (3) verbs referring to ‘change’ and ‘reverse’, such as biàn, fǎn, dào; (4) verbs indicating ‘marry’ consisting of jià and qǔ. In Chinese, these verbs inherently convey the notion of change from one stage to another, which aligns with Talmy’s (2000b: 238) argument regarding the combination of transition types with states. Consequently, the core schema of the Event of State Change is possibly encoded within the verb itself rather than the satellite. However, Talmy believed that Mandarin is a satellite-framed language, with the core schema encoded by the satellite guòlái. This presents a paradox, as he also argues that the core schema of the State-Change Events is represented by the main verb in verb-framed languages but by satellites in satellite-framed ones. The specific location of the core schema in this type of construction remains an issue for future study.

Similarly, the Event of Action Correlating faces a similar dilemma, as the only collocated verb gēn ‘follow’ in Chinese inherently implies two participants. Therefore, it becomes evident once more that Mandarin Chinese does not adhere strictly to the characteristics of a typical satellite-framed language, which contributes valuable insights to language typology debates.

6.3 A qualitative examination on the macro-event types represented by the 28 Mandarin directional complements

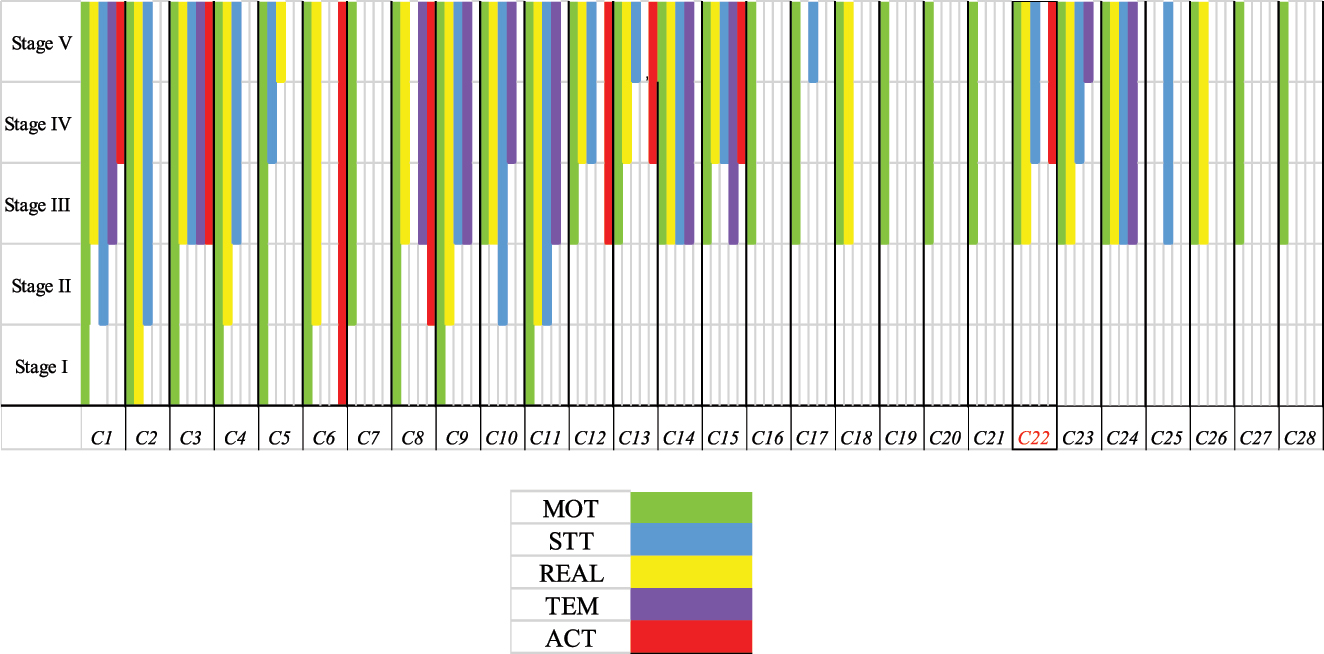

The meticulous examination of the diachronic development of guòlái ‘come over’ led us to question whether all Mandarin directional complements undergo a similar developmental process to represent five types of the macro-events. To address this inquiry, this research proceeded by qualitatively analyzing the diachronic data of all 28 directional complements (cf. Table 1). Data retrieval employed the same corpus and periodization as that of guòlái, albeit not using a systematic quantitative statistical method. Rather, once we identified more than one occurrence encoding a specific macro-event type, we assumed the directional complement construction’s capability to represent that type of the macro-event. This approach aligns with Flach’s (2021) perspective that once textual evidence of a certain construction is discovered in corpora, it is reasonable to assume its conventional usage in publishing or correspondence, even within a limited subsection of the speech community. Finally, a tentative development path of all 28 Mandarin directional complements is delineated and visualized in Figure 5. The color blocks, categorized into five types, correspond to five distinct types of the macro-event. The appearance of a color block at a stage signifies the complements’ capacity to represent that macro-event type.

The development of the macro-event types represented by the 28 Mandarin directional complement constructions.

From Figure 5, several conclusions can be drawn:

Mandarin complex directional complement constructions emerge significantly later, primarily surfacing at Stage III (618–1279), whereas most simplex directional complement constructions appear predominantly in Stage I (1046 BCE-220). Exceptions include huí ‘back’ and kāi ‘away’. This finding aligns with broader research in Chinese linguistics (e.g., Liang 2007; Song 2012).

Directional complement constructions involving kāi ‘away’ and kāilái ‘away’ initially do not represent Motion Events, possibly due to the distinct semantics of kāi, as discussed in Wang (2005), Wang and Gong (2015).

Generally, the evolutionary sequence of the macro-event types represented by all directional complement constructions can be summarized as follows: Motion Event > Event of Realization/State Change > Event of Temporal Contouring. The Event of Action Correlating is excluded, since it tends to be encoded within the semantics of the main verb rather than in the directional complements (see Section 6.1). Moreover, since complex directional complements consist of a simplex directional complement (i.e. C3 – C11) combined with lái ‘come’ or qù ‘go’ to indicate reference points, their meanings are more specific and therefore more constrained than those of simplex complements. Consequently, most complex directional complements lack the ability to represent the Event of Temporal Contouring, further validating Liang’s (2007) findings.

This developmental process not only corresponds to the grammaticalization cline across the five types of macro-events proposed by Li (2018) but also to the semantic evolution path proposed by Liang (2007) based on a qualitative analysis of shàng ‘up’, xià ‘down’, and qǐlái ‘get up’. Moreover, it aligns with the widely acknowledged evolution of human cognition, which transitions from spatial to temporal concepts, paralleling the evolution of human language. For instance, Lakoff and Johnson (2003) [1980] argue that temporal metaphors in languages often originate from spatial metaphors. Similarly, Evans (2004: 5) suggests that humans commonly conceptualize and discuss time in terms of motion through and location within three-dimensional space, thereby attributing the emergence of temporal concepts to spatial ones. Heine et al. (1991) proposed a general hierarchical grammatical structure: person > object > activity > space > time > quality. Huang and Heish (2008) further refined this framework by introducing the concept of “non-specific space” between “space” and “time”, highlighting the need for a more nuanced categorization. However, these theories may oversimplify the relationship between time and space, treating “time” as a monolithic category rather than recognizing its internal complexity. The evolutionary order of macro-event types represented by Mandarin directional complements suggests that the notion of “time” encompasses multiple dimensions, including culmination and continuation, rather than existing as a singular entity.

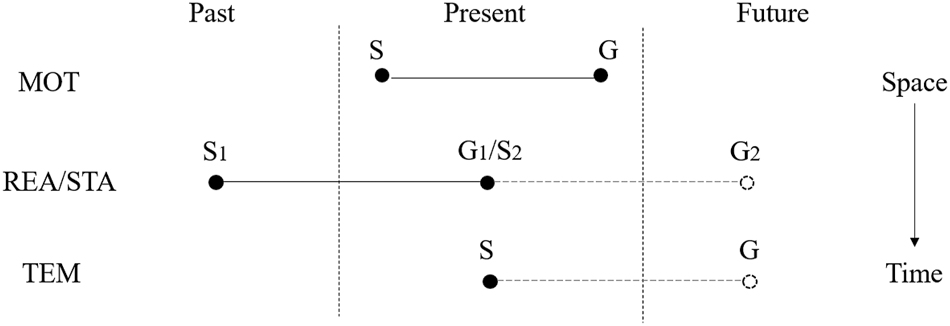

Specifically, the evolution follows a continuum from events rooted in spatial configurations to events extending into the future, with events culminating in the present serving as the transitional phase. This transition reflects a gradual shift from concrete spatial relations to temporally abstract meanings, where the boundaries between past, present, and future are relative to the discourse context. Figure 6 illustrates the underlying logic of this continuum, where S represents the starting point, and G denotes the goal of the conceptual trajectory.

The cognitive explanation for the development of the macro-event types represented by the 28 Mandarin directional complement constructions.

Motion Events are the most tangible, as they occur within the spatial dimension and can therefore be initially represented by most directional constructions. Over time, Events of Realization and State Change begin to incorporate the temporal dimension, as they denote event progression along time, especially emphasizing the endpoint of an action or a change-of-state event. Specifically, Events of Realization highlight the accomplishments of actions at present, whereas Events of State Change mark the endpoints of preceding actions or states and the inception of new ones. However, both only encode culmination, rather than temporal continuation. This tendency may explain why Events of State Change typically follow Events of Realization in most directional complements. Finally, Events of Temporal Contouring, being the most abstract, focus on the continuation of actions or states from past or present into the future. Many directional complement constructions, particularly complex ones including guòlái in this study, struggle to represent this type of macro-events due to the constraints imposed by lái ‘come’ and qù ‘go’ in the second complement position. In conclusion, Mandarin directional complements witness the development of indicating concepts of space > culmination > continuation. This pattern aligns with the semantic extension path of Mandarin directional complements proposed by Chinese scholars such as Liu (1998), Liang (2007), Song (2007), and Wang and Gong (2018). Future studies can further substantiate this sequence through corpus-based quantitative analysis.

Overall, drawing on the syntactic and semantic development of the entire closed set of Mandarin directional complements, this study proposes the Unidirectional Progression Hypothesis: the closed set of Mandarin directional complements has evolved simultaneously in both form and meaning along a unidirectional trajectory. Syntactically, this evolution has moved toward greater structural compactness – shifting from two clauses to a single clause, with increasing degree of grammaticalization within the single-clause structure. Semantically, it has progressed from concrete to more abstract meanings, starting from two independent motion events that merged into a single macro-event of motion, subsequently expanding to other macro-event types, representing culmination and continuation in the temporal dimension. Both trends follow a unidirectional path, with later stages exhibiting stronger syntactic integration and a more abstract semantic relationship between the main verb and the directional complement.[3]

7 Conclusions

In summary, this study conducts an in-depth diachronic analysis of the complex directional complement guòlái ‘come over’ from a cognitive semantic perspective.

Syntactically, guò and lái initially functioned as discrete motion verbs in two clauses, with guò signifying “passing through a location” and lái denoting “coming to the location (of the speaker)”. Over time, they merged into a single verb, guòlái, meaning “come over”, and began to be used within a single clause. Subsequently, guòlái was used after the main verb and further grammaticalized into a directional complement, exhibiting a higher degree of grammaticalization over time, as evidenced by its ability to co-occur with inserted objects and tense markers. A more general schema for the syntactic evolution of all complex directional complements is proposed in Figure 4, further reinforcing the syntactic and grammaticalization continua of the Macro-event Hypothesis.

Semantically, based on the present data, the evolutionary order of the macro-event types represented by guòlái can be delineated as Motion Event > Event of Realization > Event of State Change / Event of Action Correlating (> Event of Temporal Contouring). Additionally, this study qualitatively examined the macro-event types represented by all 28 Mandarin directional complements, reaffirming their evolutionary progression in encoding concepts of space > culmination > continuation from the macro-event perspective. However, within the scope of our study, which extends up to the 1920s, due to the semantic constraints imposed by lái ‘come’ and qù ‘go’ in the second complement position, most complex directional complements, including guòlái, advance only to the second stage, i.e., culmination. Yet, in the Contemporary Mandarin sub-corpus of CCL, guòlái has been observed to represent temporal continuation, suggesting that other directional complements may exhibit similar developments.

Building on the findings of syntactic and semantic development, this study proposed a broader hypothesis encompassing the entire closed set of complements – the Unidirectional Progression Hypothesis. This hypothesis integrates both syntactic and semantic evolution, suggesting a unidirectional trend toward greater structural tightness and increased semantic abstraction. Therefore, this research contributes to the diachronic study of linguistic typology and offers valuable insights into the intricate cognitive mechanisms that shape human language, with a particular focus on Mandarin complex directional complements.

While offering valuable insights, the present study also has certain limitations that can serve as catalysts for future research. Firstly, the periodization employed in this study spans a vast time frame, making it challenging to precisely delineate the evolutionary order of both syntactic forms and the macro-event types. This issue is inherent to many diachronic studies on Mandarin. However, despite this constraint, the general development pattern can still be identified and warrant further exploration. Furthermore, for verbs that inherently encode the meaning of “change” or “action correlating”, further research is needed to explore the nuances of their semantic evolution.

Funding source: National Social Science Fund of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 21BYY045

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful for the insightful comments and suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers and editors. All remaining errors are solely our responsibility.

-

Research funding: This study is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China entitled “A Diachronic Typological Study on the Chinese Verb-complement of Macro-event” (21BYY045, PI: Fuyin Thomas Li).

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository, at https://osf.io/qr7z8/.

References

Cao, Hongyu. 2021. Hanyu fuhe quxiang buyu yu dongci guanliandu de shizheng yanjiu – Yi “shanglai shangqu xialai xiaqu” weili [An empirical study on the correlation between compound directional complements in Chinese and verb association – Taking “shanglai, shangqu, xialai, xiaqu” as examples]. Waiyu Yanjiu [Foreign Language Research] 38(6). 40–45.Search in Google Scholar

Cao, Hongyu. 2023. Xiandai Hanyu xianhe fanchou kuozhang xiaoying de celiang – Yi fuhe quxiang buyu “qilai” weili [Measurement of the expanding effect of the prominent category in modern Chinese – A case study of the compound directional complement “qilai”]. Hanyu Xuexi [Chinese Language Learning](3). 63–71.Search in Google Scholar

Chao, Yuenren. 1968. A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Croft, William, Jóhanna Barðdal, Willem Hollmann, Violeta Sotirova & Chiaki Taoka. 2010. Revising Talmy’s typological classification of complex event constructions. In Hans C. Boas (ed.), Contrastive studies in construction grammar, 201–235. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cal.10.09croSearch in Google Scholar

Dai, Haoyi & He Huang. 1988. Shijian shunxu he hanyu de yuxu [Temporal sequence and word order in Chinese]. Guowai Yuyanxue [Foreign Linguistics](1). 10–20.Search in Google Scholar

Dong, Xiufang. 1998. Shubu dai bin jushi zhong de yunlyv zhiyue [Prosodic constraints in verb-complement constructions with objects]. Yuyan Yanjiu [Studies in Language and Linguistics](1). 55–62.Search in Google Scholar

Du, Jing & Fuyin Li. 2021. Hongshijian lishi yanbian lianxutong [The diachronic evolution continuum of Macro-events]. Waiwen Yanjiu [Foreign Studies] 9(3). 1–9+106.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, Vyvyan. 2004. The structure of time: Language, meaning and temporal cognition. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Flach, Susanne. 2021. From movement into action to manner of causation: Changes in argument mapping in the into-causative. Linguistics 59(1). 247–283. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2020-0269.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Xiliang. 2013. Hanyushi de fenqi wenti [The periodization problem in Chinese language history]. Yuwen Yanjiu [Linguistic Research](4). 1–4.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd, Ulrike Claudi & Friederike Hünnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization: A conceptual framework. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Su-miao & Shelley Ching-yu Hsieh. 2008. Grammaticalization of directional complements in Mandarin Chinese. Language and Linguistics 9(1). 469–501.Search in Google Scholar

Jia, Yu. 1998. Lai/qu” zuo quxiang buyu shi dongci binyu de weizhi [The position of the verb object when “lai/qu” functions as a directional complement]. Shijie Hanyu Jiaoxue [World Chinese Teaching](1). 41–46.Search in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 2003 [1980]. Metaphors we live by, 2nd edn. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226470993.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Li, Charles N. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1981. Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.10.1525/9780520352858Search in Google Scholar

Li, Fuyin Thomas. 2018. Extending the Talmyan typology: A case study of the macro-event as event integration and grammaticalization in Mandarin. Cognitive Linguistics 29(3). 585–621. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2016-0050.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Fuyin Thomas. 2019. Evolutionary order of macro-events in Mandarin. Review of Cognitive Linguistics 17(1). 155–186. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.00030.li.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Fuyin Thomas. 2020. Hongshijian jiashuo ji qi zai hanyu zhong de shizheng yanjiu [Macro-event hypothesis and its empirical research in Chinese]. Waiyu Jiaoxue Yu Yanjiu [Foreign Language Teaching and Research] 52(3). 349–360+479–480.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Fuyin Thomas. 2023. The macro-event hypothesis. In Fuyin Thomas Li (ed.), Handbook of cognitive semantics (Volume 3), 119–145. Leiden & Boston: Brill.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Fuyin Thomas & Na Liu. 2021. Potentials for grammaticalization: Sensitivity to position and event type. Review of Cognitive Linguistics 19(2). 363–402. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.00088.li.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jiachun. 2020. Xiandai hanyu shixian shijian cihuihua moshi de leixingxue kaocha – Jiyu kouyu youdao shiyan de zhengju [A typological investigation of lexicalization patterns for macro-events in modern Chinese – Based on evidence from spoken language induction experiments]. Jiefangjun Waiguoyu Xueyuan Xuebao [Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages] 43(4). 71–77+137.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jinxi. 1924. Xinzhu guoyu wenfa [Newly written national language grammar]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jinxi. 2004. Li Jinxi yuyanxue lunwen ji [Collected linguistic papers of Li Jinxi]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Search in Google Scholar

Liang, Yinfeng. 2007. Hanyu quxiang dongci de yufahua [Grammaticalization of directional verbs in Chinese]. Shanghai: Xue Lin Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Meili & Hubert Cuyckens. 2023. Alternation in the Mandarin disposal constructions: Quantifying their evolutionary dynamics across twelve centuries. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 21(1). 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2023-0038.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Na & Fuyin Thomas Li. 2023. Event integration as a driving force of language change: Evidence from Chinese 使-shǐ-make. Language and Cognition 36. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2023.36.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Yuehua. 1998. Quxiang buyu Tongshi [An inventory of directional complements]. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Jianming. 2002. Dongci hou quxiang buyu he binyu de weizhi wenti [Concerning the verbal complement of direction and the position of object]. Shijie Hanyu Jiaoxue [Chinese Teaching in the World](1). 5–17.Search in Google Scholar

Luo, Xinghuan. 2008. Ying han yundong shijian cihuihua moshi de leixingxue yanjiu [A typological study of lexicalization patterns in motion events in English and Chinese]. Waiyu Jiaoxue [Foreign Language Education] 29(3). 29–33.Search in Google Scholar

Lyu, Shuxiang. 1953. Yufa xuexi [Grammar learning]. Beijing: China Youth Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lyu, Shuxiang. 1980. Xiandai hanyu babai ci [Eight hundred words in modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, Yubian. 2005. Quxiang dongci de renzhi fenxi [Cognitive analysis of directional verbs]. Hanyu Xuexi [Chinese Language Learning](6). 34–39.Search in Google Scholar