Abstract

Many verbs in English show causative and noncausative uses. The goal of this paper is to identify a factor most strongly associated with the realizations of the causative alternation. We report a corpus study that tested effects of three semantic and contextual factors – intentionality, contextual identifiability, and external causality – against 3,864 instances of causative and noncausative uses of 135 alternating verbs extracted from the automatically parsed British National Corpus. Our results of a series of multifactorial analyses of the corpus data indicate that intentionality and contextual identifiability are significantly associated with the realizations, with contextual identifiability being the most predictive factor: causative situations with a clear identifiable agent are realized predominantly as a causative, whereas those with a less clear, non-agentive cause are generally expressed noncausatively. Building on Rappaport Hovav, Malka. (2014). Lexical content and context: The causative alternation in English revisited. Lingua 141. 8–29. DOI:10.1016/j.lingua.2013.09.006, Rappaport Hovav, Malka. (2020). Deconstructing internal causation. In Elitzur A. Bar-Asher Siegal & Nora Boneh (eds.), Perspectives on causations: Selected papers from the Jerusalem workshop 2017, 219–256. Berlin: Springer and Lee, Hanjung. (2023). Cause identifiability and the causative alternation in English: A corpus-based analysis. Linguistic Research 40(3). 353–385, accounts of contextual constraints on the causative alternation, we propose that the observed pattern of form-meaning associations in the data can be interpreted as a consequence of general principles of communicative efficiency.

1 Introduction

Many verbs in English show the two argument realization options in (1a) and (1b), which together constitute the causative alternation (also known as the “anticausative” or “causative/inchoative” alternation). This alternation is characterized by verbs that have both causative and noncausative uses, where the causative use roughly means ‘cause to V-intransitive’. The causative variant expresses causation wherein the causer brings about a change in location or state of the causee or patient as in (1a), whereas the noncausative variant expresses just the caused event as in (1b). Concomitantly, the causative variant includes a causer argument absent in the noncausative variant. This paper investigates semantic and contextual factors which determine the (non)expression of the cause argument.[1]

| a. | Perry broke the fence. | (causative variant) |

| b. | The fence broke. | (noncausative variant) |

There is growing consensus in the literature that the constraints on the alternation involve both lexical and nonlexical factors (e.g., Rappaport Hovav 2014, 2020; Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2012; Schäfer 2008), contra earlier approaches that tried to attribute the alternation to the lexically specified nature of the event and the cause argument (e.g., Alexiadou et al. 2006; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Reinhart 2002). Recent quantitative studies incorporate various semantic and contextual factors such as the nature of causation and the identifiability of the ultimate cause of the event in specific discourse contexts, to successfully account for the corpus frequency distribution of the alternation variants (e.g., Haspelmath et al. 2014; Lee 2023; Samardžić and Merlo 2018). However, these factors have been considered in isolation by different scholars, and few studies have simultaneously investigated them in relation to the causative alternation. This gap led us to ask whether the nature of causation and cause identifiability in context influence the choice of the alternation variant when tested simultaneously. The goal of this paper is to identify the factor most strongly associated with the variant (that is, causative or noncausative) on the basis of a careful analysis of 3,864 instances of causative and noncausative uses of 135 alternating verbs extracted from the British National Corpus (BNC).

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of major theoretical and empirical approaches to the lexical and other constraints on the causative alternation in English. Section 3 describes the data source and the data extraction process and discusses the variables tested in this study. Section 4 introduces the statistical methods and presents the results of the quantitative analyses. The results of a series of multifactorial analyses indicate that both intentionality and contextual identifiability are significantly associated with the realizations, with contextual identifiability emerging as the most predictive factor. In Section 5, we discuss a possible explanation of these findings and the cross-linguistic implications of this study. Section 6 concludes the paper by discussing further theoretical and empirical implications of this study and challenges for future work.

2 Theoretical background

This section examines major theoretical approaches to the causative alternation and quantitative studies on the frequencies of the causative and noncausative uses of alternating verbs.

2.1 Theoretical approaches to constraints on the causative alternation

Previous approaches to the causative alternation fall into two major classes. The first class assumes that the main constraint on the alternation derives from the lexical characterization of the cause argument. This class of approaches has been most fully developed in Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) and Reinhart (2002, 2016). The second class assumes that the constraints on the alternation follow from the lexical classification of the verb together with nonlexical factors, stressing the interplay of lexical and nonlexical factors in explaining the limited productivity of the alternation. This class of approaches is represented by Alexiadou (2010), Alexiadou and Doron (2012), Alexiadou et al. (2006), Rappaport Hovav (2014, 2020), and Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2012), despite significant differences among their analyses.

A key assumption shared by many accounts of the causative alternation that represent these two classes of approaches is that the alternation is enabled by the underlying lexical structure of the alternating verbs (e.g., Alexiadou et al. 2006; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Reinhart 2002, 2016; Samardžić and Merlo 2018, among others). In their seminal work, Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) first proposed that the crucial lexical-semantic distinction for characterizing the class of alternating verbs is between verbs denoting internally caused eventualities and those denoting externally caused eventualities. They assume that verbs denoting internally caused eventualities, such as bloom and blossom, are lexically monadic, selecting only the argument denoting the entity undergoing the change specified by the verb. Conversely, verbs denoting externally caused eventualities, such as destroy and open, are lexically dyadic, additionally selecting a cause argument. On their account, a subset of verbs denoting externally caused events, such as break and open, undergo a process of lexical binding of the external argument, which prevents the external argument from being expressed syntactically, thus resulting in the noncausative variant of the alternation. Reinhart (2002, 2016) provides a similar characterization of the class of alternating verbs. Like Levin and Rappaport Hovav’s (1995) analysis, her analysis of the causative alternation takes the causative variant to be basic, deriving the noncausative variant from it via a lexical operation of decausativization. This operation applies to verbs that simply specify that their subject is a cause, subsuming agents, natural forces, and instruments (Reinhart 2016: 25).

Thus, both Levin and Rappaport Hovav’s (1995) and Reinhart’s (2002, 2016) accounts characterize the class of alternating verbs over the causative variant of the alternation as verbs with no lexical specification for the causing event. This characterization predicts that alternating verbs can appear with a wide range of semantic types of NPs, as shown in (2a) and (2b). In contrast, the verb murder specifies something about the causing event (it must involve intention). Hence, this verb cannot undergo lexical binding or decausativization, and does not participate in the alternation, as shown in (3).

| a. | The vandals/the rocks/the storm broke the windows. |

| b. | The butler/the key/the wind opened the door. |

| a. | The hit men/*the bullets/*the plan murdered the gangster. |

| b. | *The gangster murdered. |

A challenge encountered by such lexically-oriented accounts is that some verbs which fit the characterization of the class of alternating verbs do not alternate, as illustrated for destroy and kill in examples (4) and (5). As noted out by Rappaport Hovav (2014: 15), English verbs of destruction and killing are often classified as externally caused and do not lexically specify any particular cause of the state change, as indicated by the fact that these verbs allow a range of NPs as cause as in (4a) and (5a). Nevertheless, these verbs do not alternate, as shown in (4b) and (5b).

| a. | The vandals/the storm/the intense heat destroyed the crops. | ||

| b. | *The crops destroyed. | (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 15, (31)) | |

| a. | The marauders/the position/the cold killed the chickens. | ||

| b. | *The chickens killed. | (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 15, (32)) | |

Another challenge for Levin and Rappaport Hovav’s (1995) and Reinhart’s (2002, 2016) lexically-oriented accounts arises because the causative alternation is not entirely constrained by the lexical specification of the verb; contextual factors also play a critical role. If the lexical specification of the verb were solely responsible for constraining the alternation, then all externally caused verbs that are compatible with NPs, bearing a range of semantic roles in subject position, would be expected to appear in both variants, regardless of the properties of the NP chosen as the theme. However, this is not the case. Change of state verbs that may select agents, natural forces, and instruments as subjects may still not exhibit noncausative uses for some choices of causative variant themes. As Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) note, causative sentences of change-of-state verbs − the prototypical causative alternation verbs − lack a noncausative counterpart, as demonstrated in examples (6) and (7).

| a. | He broke his promise/the contract/the world record. | ||

| b. | *His promise/*The contract/*The world record broke. | ||

| (Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995: 85, (9)) | |||

| a. | The waiter cleared the table. | ||

| b. | *The table cleared. | (Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995: 104, (55)) | |

Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2012) demonstrate that similar patterns are found with other change of state verbs such as empty, lengthen and shorten. These verbs conform to the lexical specification of the class of alternating verbs, and do indeed alternate, as exemplified by clear in (8). However, in certain cases, a noncausative variant is ill-formed in isolation, as in (7b) above.

| a. | The wind cleared the sky. | |

| b. | The sky cleared. | (Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995: 104, (55)) |

Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995: 102) propose that the rule of lexical binding is limited to cases where the verb denotes an “eventuality [that] can come about spontaneously without the intervention of an agent” (cf. Haspelmath 1993; Smith 1978). This accounts for the contrast between (8b), which describes an event that can take place without an agent, and (6b) and (7b) which cannot.

However, the spontaneity condition on application of lexical binding is problematic on both theoretical and empirical grounds. First, it is not the verb’s meaning that determines spontaneity or agent involvement; instead, world knowledge and properties of events tell us that certain events, such as clearing of the sky and lengthening of the days, do not need the intervention of an agent, while others, like clearing of the counter/the table and lengthening of the skirt, necessitate such intervention. Thus, the constraint on the availability of variants appears to be non-lexical in nature (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2012; Schäfer 2008). Rather, as Rappaport Hovav (2014) accurately observes, it seems to be a constraint on the suitability of the noncausative variant in describing events of a certain type. The non-lexical nature of this constraint on the alternation thereby challenges the basic assumptions of Levin and Rappaport Hovav’s (1995) and Reinhart’s (2002, 2016) lexically-oriented accounts, which assume that all alternating verbs are inherently dyadic and the noncausative form is derived through a lexical rule that removes the cause argument.

A further empirical problem of the spontaneity condition on the application of lexical binding is the prevalence of noncausative uses of alternating verbs that describe events involving an unspecified external agent. Consider the following examples of noncausative sentences of open from the BNC in (9), discussed by Lee (2023: 360).[2] These examples describe events of opening that require the participation of an agent: opening shops and opening a village; these contrast with opening a door which could be done by an agent, an instrument, or even a natural force (see (2b)).

| a. | It is hoped that the builders will be on site by July and <the first shops will open by Christmas 1994>. (BNC W:misc, K98-126) |

| b. | <A second phase of the village is due to open> in July 1991 featuring a traditional Irish thatched cottage, entertainment, a street market at weekends and more craft workshops. (BNC W:misc, B29-636) |

In example (9), the addressee may not be able to determine the specific identity of the agent, but can infer the type of agent, such as the owner of a shop and the local government. In such cases, the unexpressed agent is type-inferable, though its exact identity remains unidentifiable, irrelevant and unimportant. This kind of inferable agent is generally disfavored in causative uses, if not entirely excluded. However, contrary to this observation, Levin and Rappaport’s (1995) account predicts that agentive uses of verbs lack a noncausative variant, as on their account a process of lexical binding is restricted to verbs denoting an event that can come about spontaneously.

Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2012) and Rappaport Hovav (2014) propose a non-derivational approach to the alternation which diverges from their own earlier analysis and those of Reinhart (2002, 2016), as well as non-derivational analyses embodied in Alexiadou et al. (2006) and others. In the realm of change-of-state verbs, Rappaport Hovav (2014) makes a three-way classification, summarized in Table 1.

Rappaport Hovav’s (2014) three-way classification of change-of-state verbs.

| Verbs that lexically select an external cause argument (non-alternating in English) | Verbs that specify something about the nature of the involvement of an external cause, such as murder and assassinate |

| Verbs that specify nothing about the nature of the causing event, for example, kill and destroy | |

| Verbs lexically associated with an internal argument only (alternating in English) | Verbs that specify the nature of the change of state but nothing specific about the cause of the change of state, such as break, open and clear |

According to Rappaport Hovav (2014), verbs such as murder and assassinate, which lexicalize both a volitional action and a change of state, are lexically associated with an external cause argument, and this argument cannot be omitted. Verbs of destruction and killing share this pattern, as their external cause argument cannot be omitted. Consequently, the verbs of the first two classes are indistinguishable by lexical adicity in English. In contrast, verbs that allow alternation in English are lexically associated solely with their patient. Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2012) and Rappaport Hovav (2014) provide systematic evidence supporting this view. The addition of the cause is non-lexical, driven by the well-known constraint that the cause must be construable as a direct cause – a cause with immediate control over the eventuality. Building on Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2012), Rappaport Hovav (2014) suggests that a causer can be realized with a change-of-state verb just when the event being described involves direct causation in the sense defined by Wolff (2003: 5). This constraint contributes to the determination of the semantic type of NPs allowed as the external argument in given contexts. It does not, however, explain why alternating verbs differ with respect to how often they are used as a causative and as a noncausative and which variant is appropriate in a given discourse context. For this, we need a theory which accounts for the (non-)appearance of the cause argument.

Rappaport Hovav (2014) provides a pragmatic account of the (non-)appearance of the cause argument. Drawing on Grice’s (1975) maxims of conversations, she argues that if the expression of the cause is deemed relevant, it is typically preferred since the causative variant is more informative. The degree of informativeness of the causative variant is influenced by factors such as contextual identifiability and predictability of the cause. For instance, if the cause is recoverable in some way from context, then the sentence with the cause expressed is no longer more informative than the corresponding sentence that expresses just the change of state. In that case, mentioning the cause seems superfluous and the noncausative may be preferred from economy considerations like Grice’s (1975) Maxim of Manner, which dictates avoiding prolixity.

Sometimes the speaker will leave the agent unmentioned though the causative variant would be more informative. This happens, according to Rappaport Hovav (2014), when the speaker does not know the cause; consequently, the noncausative is required because the speaker cannot truthfully specify the cause. Rappaport Hovav (2014, 2020) shows that this account covers constraints on the alternation which have been taken to be lexical and also those which are more clearly non-lexical in earlier accounts.

The inclusion of contextual constraints in the analysis of the causative alternation has recently gained ground in an empirical work by Lee (2023). In the following subsection, we discuss this work and other quantitative studies on the causative alternation.

2.2 Quantitative studies on the causative alternation

Quantitative studies on the causative alternation have focused on the morphosyntactic form of alternating verbs, which has emerged as a major locus of cross-linguistic variation. In his typological work, Haspelmath (1993), distinguishes five types of encoding of the causative alternation: (i) the marked causative type, where the causative variant is formally marked as opposed to the noncausative variant (illustrated by Georgian in Table 2); (ii) the marked anticausative type, where the noncausative variant is formally marked as opposed to the causative variant (as in the Polish example); (iii) the labile type, with no formal change in the verb occurs (as seen in English); (iv) the equipollent type, where both the causative and the noncausative variant bear special morphology that is attached to a shared stem (as in the Japanese example); and (v) the suppletive type, where the two variants are expressed by verbs which are formally not related (as in the Russian example). The different marking strategies illustrated in Table 2 represent only the most prevalent markings. Languages may adopt different strategies for different verbs. For instance, in Korean, the intransitive version of the verb meaning ‘open’ is morphologically marked, whereas the transitive version is not marked (i.e., yel-li- ‘open (intransitive)’ versus yel- ‘open (transitive)’). On the other hand, the transitive version of the verb meaning ‘freeze’ is morphologically marked, while the intransitive version remains unmarked (i.e., el- ‘freeze (intransitive)’ versus el-li- ‘freeze (transitive)’).

Encoding types of the causative alternation (Haspelmath 1993, adapted).

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| (i) Marked causative | Georgian |

| duγ-s ‘cook (intransitive)’ – a-duγ-ebs ‘cook (transitive)’ | |

| (ii) Marked anticausative | Polish |

| złamać się ‘break (intransitive)’ – złamać ‘break (transitive)’ | |

| (iii) Labile | English |

| break ‘break (intransitive)’ – break ‘break (transitive)’ | |

| (iv) Equipollent | Japanese |

| atum-aru ‘gather (intransitive)’ – atum-eru ‘gather (transitive)’ | |

| (v) Suppletive | Russian |

| goret’ ‘burn (intransitive)’ – žeč ‘burn (transitive)’ |

Numerous empirical studies have shown that the morphological marking of the causative alternation correlates with spontaneity (Croft 1990; Haspelmath 1993, 2008, 2016; Haspelmath et al. 2014; Nedjalkov 1969). Haspelmath (1993: 103) contends that the more spontaneous an event is, the more likely it is to be expressed with a marked causative:

[A] factor favoring the anticausative expression type [=marked anticausative] is the probability of an outside force bringing about the event. Conversely, the causative expression type [=marked causative] is favored if the event is quite likely to happen even if no outside force is present. (Haspelmath 1993: 103; modified)

This study has been extended, and its results have been reinterpreted with a novel explanation in Haspelmath (2008, 2016) and Haspelmath et al. (2014). In Haspelmath’s view, the recurrent pattern in the encoding of the alternation reflects a principle of efficient communication: unmarked forms remain unmarked due to their high frequency of use (as measured by corpus frequency) irrespective of the lexical properties of verbs.

The relation between the lexical properties of verbs and formal encodings of the causative alternation has been examined in a recent corpus study by Samardžić and Merlo (2018). They revisit the concept of external causation, defining it as the likelihood of an external agent’s involvement in an event described by a verb. They refer to this property as Sp for spontaneity (following Haspelmath [1993]), and consider the degree of Sp as a scalar component integrated into the lexical representation of alternating verbs, assigned as a common property across the causative and noncausative realizations (Samardžić and Merlo 2018: 905). Statistical analyses of data extracted from the English component of the parallel corpus Europarl reveal that the corpus-based measure of Sp correlates with the rank of verbs based on the C/A ratio calculated from the typology of the morphological marking of the verbs across languages.[3] Samardžić and Merlo (2018) interpret this correlation as evidence that the probability of external causation is a grammatically relevant lexical property, influencing both the corpus frequency distribution of structural realizations of alternating verbs and the typological distribution of their morphological markings: both are seen as effects of the distribution of Sp-value across verb types. This interpretation posits that the ratio between causative and noncausative uses of a verb serves as a quantifiable indicator of a verb’s lexical property.

Another notable result of this work is that the Sp-value exhibits a normal distribution across a large set of verbs listed by Levin (1993). Given that a normal distribution is symmetric and concentrated around the mean, this finding suggests that most alternating verbs can be expected to describe events with approximately a 50 percent likelihood of involving an external causer. Samardžić and Merlo’s (2018: 914) analysis further shows that while most verbs are neutral regarding external causality, only some tend to be assigned extreme Sp-values. If the majority of alternating verbs indeed describe events whose external causer can be present or absent with similar probability, this raises several questions unaddressed in Samardžić and Merlo (2018): what determines the appearance of the cause argument in a given context? Why one variant is chosen rather than the other when, in principle, both might be possible? Is the choice a matter of lexical, semantic, discourse or contextual considerations?

These questions are taken up in Lee’s (2023) work, which tests several predictions on the relationship between the frequencies of causative and noncausative uses of alternating verbs and the ease with which the ultimate cause of an event can be identified in specific discourse contexts. Figure 1 illustrates the classification of cause types based on ease of identification (Lee 2023: 362).

Classification of cause types according to the ease of identification.

Agents are regarded as the prototypical causes (Croft 1991; Lakoff 1990; Talmy 1976, 2000) and are typically isolatable as the ultimate cause because they often have intentions to bring about specific changes. In contrast, when an event is nonagentive, determining its ultimate cause can prove more challenging. Rappaport Hovav (2014) contends that sentences such as The window opened and The vase broke are easier to accept than sentences such as The table cleared and The skirt lengthened because it is easy to imagine a scenario in which the speaker sees the change of state but not the act which brings it about: i) the change of state is brought about by some nonagentive cause lacking intentions (e.g., by the wind), and then the cause may not be easily identifiable; (ii) the change of state is brought about by the action of an agent from a distance. When there are a number of causes normally present simultaneously, it becomes even more difficult to identify the ultimate cause of an event. This happens in various circumstances when a change is recoverable by default or unidentifiable from context. Many natural events of change have default causes. As noted by Rappaport Hovav (2014: 24), there are a number of causes normally present simultaneously for changes which come about in the normal course of events (e.g., hair growing longer, trees growing, skies clearing) or those that occur gradually over the course of time. Thus, it is generally difficult to identify a single, isolatable cause for such changes.

One of the main results of Lee’s (2023) corpus study of 12 change-of-state verbs is that there is a strong positive correlation between the ease of identifying the cause and the frequency of verb uses: verbs predominantly used as a causative tend to have a higher percentage of agent causers, a cause type characterized by the greatest ease of identifiability, whereas verbs that are more frequently used as a noncausative cause are associated with cause arguments that are less easily identifiable. A further notable result is the increased proportion of nonagentive causers in the causative uses of verbs that are used more frequently as a noncausative. Nonagentive causers are less frequent in verbs that are predominantly used as a causative. These findings are consistent with the results of Heidinger and Huyghe’s (2024) recent corpus study on French change-of-state verbs. Furthermore, they offer corroborative evidence of a relationship between the noncausative use of a verb and the semantic role of its transitive subject: the more frequently the transitive subject of a verb is a nonagentive causer (as opposed to an agent or instrument), the more likely the verb is used as a noncausative (as opposed to a transitive causative).

In addition to presenting these novel empirical findings, Lee (2023) proposes an account for the observed correlation between cause types and verb uses based on communicative efficiency. Developing the line of argumentation in Levshina (2022), she argues that the correlation between agents and the causative variant, as well as between nonagentive causers and the noncausative variant, stems from the principle of efficient language use, which posits a positive correlation between benefits and costs in communication. According to this principle, high costs correlate with high benefits, and low costs correlate with low benefits. Therefore, language users are incentivized to invest more effort and time in conveying information that yields greater benefits, and to expend less effort and time on information of less utility (Levshina 2022: 22).[4] From the efficiency perspective, the causative variant, which specifies the cause of a change of state, involves greater costly but is simultaneously more informative than the noncausative variant, which expresses just the change of state. As Rappaport Hovav (2014) has noted, the choice of the causative variant is preferrable unless the extra information, namely, the cause of the change of state, is redundant, unimportant, or unidentifiable. Consequently, the high costs associated with producing a more complex structure are justified by the substantial relevance and significance of the identifiable agent in describing a change of state and the enhanced informativeness of the causative variant. These constitute the communicative benefits in a broadly encompassing sense and ultimately motivate the efficient division of labor between the two causative alternation variants.

This idea is compatible with Rappaport Hovav’s (2014, 2020) pragmatic account of the causative alternation based on Gricean maxims of conversation. However, previous corpus-based studies, including Lee’s (2023) recent work, have utilized monofactorial analyses to test the impacts of individual semantic or contextual factors. There remains a lack of research employing the multifactorial analysis necessary to determine whether these individual factors independently affect the corpus frequency distribution of the alternation variants when tested concurrently. The current study aims to fill this gap by utilizing three multifactorial methods to identify a range of factors influencing variant choice in the causative alternation and to assess the impact of each factor while controlling for others.

In summary, accounts of the causative alternation must explain its limited productivity. Accounts that incorporate both semantic and contextual constraints are most successful at meeting this challenge. Precisely what factors play a more important role and how they interact in constraining the alternation is a matter for continued exploration. The following sections discuss a corpus study that tested the effects of the semantic and contextual factors known from the literature – externally versus internally caused change of state, intentionality, and the contextual identifiability of the causer – against a large set of alternating verbs.

3 Data and methodology

This section first describes the data source and methods for data collection and analysis (Section 3.1) and then discusses the variables examined in this study (Section 3.2).

3.1 Procedures

3.1.1 Selection of verbs

The focus of this study is a major class of verbs that exhibit the causative alternation, known as change-of-state (COS) verbs. The selection of these verbs is motivated by the fact that these verbs instantiate the ‘become’ semantics that favors the participation in the causative alternation, but also show variability in the frequency of causative versus noncausative uses.

We compiled a sample of COS verbs from Levin (1993), a lexical resource that describes the semantic properties and syntactic behaviors of over 3,000 English verbs. From the 9 subclasses of COS verbs identified as alternating verbs by Levin (1993), we selected the following 3: i) break verbs (e.g., break, shatter, split), ii) verbs that are zero-related to adjective (e.g., clear, open, warm), and iii) other alternating verbs of change of state (e.g., change, freeze, melt). Break verbs refer to actions that bring about a change in the material integrity of some entity. Verbs that are zero-related to adjective denote a change in the physical state described by the base and have a ‘(make) become + base’ semantic structure. Other alternating verbs of change of state include various verbs that involve changes in physical state. Unlike other COS verbs ending in -en, -ify, -ize and -ate, which carry the deadjectival affixes, this class includes members that have both nominal (e.g., change, heat, and light) and adjectival bases (e.g., close, mature, and short). This diverse selection averts formal bias and ensures morphological variety in the corpus data.

Although a full account of the causative alternation requires examining a broad range of verb classes participating in the alternation, concentrating on these three major subclasses of prototypical alternating verbs reduces interference from idiosyncratic verb meanings and results in a more refined dataset.

3.1.2 Data extraction

The data source for this study is the BNC, a 100 million word collection of samples of written and spoken language from a wide range of sources originally compiled by Oxford University Press in the 1980s − early 1990s. The BNC was selected as the data source for a first step toward multi-corpora analysis aimed at comparing the use of identical verbs additional English corpora representing more recent language use (e.g., the BNC2014, the ANC, and the COCA).

To conduct the multifactorial analysis required for this study, it was essential to extract the relevant corpus data from the raw BNC texts in a format amenable to further statistical analysis. Consequently, we established a pipeline for systematic data collection and processing; this ensures the reproducibility and replicability of our results. This section outlines the data processing pipeline depicted in Figure 2.

Procedures for data collection and analysis.

To identify instances of the two patterns involved in the causative alternation, it was necessary to add syntactic information to the corpus data. For this purpose, the raw BNC text comprising unannotated sentences was parsed automatically using a dependency parser. In this study, dependency parsing was performed using Stanza, an open-source Python natural language processing toolkit that supports 66 human languages and was developed by the Stanford NLP Group (Qi et al. 2020). Dependency parsing builds a tree structure of words from the input sentence, representing the syntactic dependency relations between words. The resulting tree representations, which follow the Universal Dependencies formalism (https://universaldependencies.org), are useful in many downstream applications. More specifically, this initial parsing step produces a corpus in a format known as the CoNLL-U format. Such a metadata file consists of split sentences that specify various types of information about each word in the sentence, including the word’ form, its position in the sentence, its lemma, its part-of-speech (pos) tag, and dependency relations (deprel)). This information facilitates the identification of relevant corpus data of interest in this study, enabling the automatic retrieval of causative and noncausative uses of verbs. Figures 3 and 4 provide the graphical dependency representation for the example sentence in (8a) and (8b), respectively.[5]

Graphical dependency representation for the sentence: The wind cleared sky.

Graphical dependency representation for the sentence: The sky cleared.

In Figures 3 and 4, all words in a sentence are connected through dependency relations, defined as binary relations that hold between a governor (also known as a head) and a dependent. For instance, the subject and object depend on the main verb; determiners depend on the nouns they modify; and so on. The labeled arc is directed from the governor to the dependent.[6]

The second step involved extracting causative and noncausative instances of verbs classified as alternating in Levin (1993) from the parsed corpus. In this study, we will consider only instances of active transitive realizations and intransitive realizations. The passive instances were extracted but excluded from the analysis, as including passives complicates the interpretation of the regression model.[7] Furthermore, we focused only on one-word uses of the verbs, excluding complex verbs composed of [verb + particle], known as verb particle constructions (VPCs), such as break down and melt away. The exclusion was based on the observation that not all multi-word uses of verbs under scrutiny exhibit the causative alternation. For example, the verb break is frequently used in VPCs, and shows some concentrated use as a sense that does not have a change-of-state interpretation, as in the war broke out. The VPC break out has a coming-into-existence sense and lacks the causative counterpart that can be paraphrased as ‘cause the war to happen’. As it is difficult to exclude only such VPCs, all VPCs were excluded from the analysis.

To retrieve only the relevant data, we wrote a Python script that identified the one-word causative and noncausative instances of 354 alternating verbs. Our script identified the causative instances by selecting sentences that contain dependency relations tagged as “nsubj” (nominal subject) and “dobj” (direct object) and governed by “root”. To extract the noncausative instances, the extraction script utilized an algorithm that filtered out sentences lacking a “dobj” dependency relation governed by “root”. Additionally, the script utilized an algorithm to exclude VPCs and passive sentences by identifying specific patterns that include the presence of “aux:pass” (passive auxiliary) and “compound:prt” (phrasal verb particle).

The data extracted during the initial two steps of the pipeline necessarily contain processing-related errors because they are collected automatically from an automatically parsed corpus. Consequently, the third step involved filtering the data to remove such errors. A manual evaluation of the dataset was conducted to assess the extent to which the analyses were accurate. The validation reveals a bias toward identifying the extracted instances as noncausatives when they are not, and this bias was found in instances of a majority of verbs included in the analysis. The noncausative bias is primarily attributed to the incorrect analysis of English passive constructions headed by the verb be such as The door was opened as noncausatives rather than passives. Other cases of incorrect analyses resulted from parsing errors that led to the assignment of an incorrect form. For instance, an intransitive form was assigned where a transitive form with an elided object should have been, or the actual forms found were not verbs but adjectives or nouns (e.g., open, close, clear, dry). As the current extraction method cannot automatically handle these cases yet, such errors were manually removed from the dataset.

Furthermore, we excluded the following constructions from the samples of relevant tokens eventually analyzed, because controlling for the direct causation interpretation and the change-of-state interpretation were paramount:

Transitive uses that are not causative: the subject is not the cause as in She broke her leg;

Uses that do not have a change-of-state interpretation as in the book opens (=begin) with an introduction to the theory of syllables;

Noncausatives modified by an adjunct phrase that does not express a direct cause as in The service in the bank improved as a result of her complaint: in this

example, her complaint is not construed as a direct cause of the change. Hence,

this sentence does not have the paraphrase Her complaint improved the service. A better paraphrase would be: The bank improved their service because of/as a result of her complaint.

Finally, we excluded idiomatic uses of the verbs to control for the influence of the non-compositional meaning on their ability to alternate and the interpretation of the sentences.

The filtering step produced a total of 15,763 extracted instances of alternating verbs, encompassing 4,566 causative instances and 8,761 noncausative instances.[8] For practical reasons, we chose to analyze a subset of the data, specifically 3,864 causative and noncausative instances of break verbs, deadjectival verbs, and other alternating verbs of change of state. Some verbs within these classes do not occur in the causative or noncausative variants in the dataset and were thus excluded. The final data set includes 13 break verbs, 34 of deadjectival verbs, and 88 other alternating verbs of change of state. We analyzed corpus occurrences of causative and noncausative uses of these 135 verbs, following the methodology outlined in the subsequent subsection.

In order to conduct a statistical analysis, the data destined for the multifactorial analysis were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet and manually annotated with five variables (verb, realization, intentionality of causation, contextual recoverability, and external causality of change of state) to compose the final dataset for this study. Figure 5 displays the first line of the file containing the final dataset for the verb abate:

Screenshot of the file containing the final dataset (the first line for abate).

3.2 Coding predictor variables for multifactorial analysis

This section provides an overview of the three semantic and contextual factors included as predictor variables in the multifactorial analysis, as listed in Table 3. The reliability of the coding, as indicated by the high inter-rater agreement score (Light’s kappas) exceeding 0.80, establishes the credibility of the coding schema.

Semantic/contextual factors operationalized as predictor variables.

| Variables | Values | Expectations |

|---|---|---|

| Intentionality | Intentional (Intent) | Causative |

| Nonintentional (NIntent) | Noncausative | |

| Contextual identifiability | Recoverable cause (RC) | Noncausative |

| Nonrecoverable cause: | ||

| Unknown cause (NRC_UC) | Noncausative | |

| Identified cause (NRC_IC) | Causative | |

| External causality | Externally caused COS (ExtCOS) | Causative |

| Internally caused COS (IntCOS) | Noncausative |

3.2.1 Intentionality

This variable distinguishes between agentive and nonagentive causes. As discussed in Section 2.2, agents are typically easily isolatable as an ultimate cause since they often have intentions to bring about specific changes. When an agent is involved in causing an event, that agent must be usually be expressed because it is more informative to mention the ultimate cause of the change of state who intends to bring about that change, if the ultimate cause is known and relevant (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 26). Consequently, the noncausative variant is generally disfavored as a description of an agentive situation unless the agent was established previously or hinted at in the discourse (see Section 3.2.2).

When an event is nonagentive, however, it may be more difficult to ascertain its ultimate cause, and using a noncausative variant becomes appropriate. Sentences such as The sky cleared and The vase broke are easier to accept compared to sentences such as The table cleared and The record broke, because they are more likely to describe a change of state brought about by a nonagentive cause that lacks intentions (e,g., by some natural force).

For the purposes of this study, the distinction between agentive and nonagentive causes was reformulated as a property of the causing action with two values: intentional causation and nonintentional causation.

Intentional causation. A causing action was coded as intentional when it denotes actions that can only be carried out intentionally (e.g., opening shops and closing business). Cases which denote a change of state not necessarily brought about by an intentional agent (e.g., breaking the window and opening the door) were classified as intentional when the context of the sentence or the immediate discourse environment indicates that the causer acted intentionally, as illustrated in (10).

| a. | The protesters broke the window. | |

| b. | I pushed and pushed on the door, and <it finally opened>. | |

| (McCawley 1978, cited in Rappaport Hovav 2014: 22, (62)) |

Nonintentional causation. All other cases were coded as nonintentional.[9] Examples of nonintentional causation are given in (11). In (11a) and (11b), the causer affects the patient accidentally or unintentionally; (11c) exemplifies inanimate causes lacking intention. (11d) describes a change of state (alteration in economic circumstances) that is unlikely initiated by intentionally acting causers.

| a. | I leaned against the door and <it accidentally opened>. | |

| (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 17, adapted from example (41)) | ||

| b. | <John broke the window> when he was playing football. | |

| (Levshina 2022: 168) | ||

| c. | The rocks/the storm broke the window. | |

| d. | Or should it adjust its policy as <circumstances change> and attempt to fine-tune the economy? (BNC W:commerce, J15-1447) |

In line with Rappaport Hovav (2014, 2020), one might expect intentional causation to increase the probability of causatives, while nonintentional causation is likely to increase the likelihood of noncausatives.

3.2.2 Contextual identifiability

This variable captures the degree to which the cause of a change of state is contextually identifiable, differentiating between recoverable cause (RC) and nonrecoverable cause (Non-RC). A recoverable cause is defined as one that can be contextually identified, whereas all other cases were considered a nonrecoverable cause and classified into unknown cause (UC) or identified cause (IC).

An identified cause is defined as a cause of a change of state explicitly singled out as the primary cause in the clause where the alternating verb is used. Identified causes and the change they bring about are specified in the same clause, enabling their clear identification as the ultimate cause of the change without having to rely on the surrounding context. The following two cases were considered identified causes: (i) causes realized as the subject or the external argument in the causative variant, and (ii) causes realized in other positions of the clause where the investigated verb is used. Research on lexical causatives has established that the subject of the causative is necessarily characterized as a cause that is conceptualized as both proximate and ultimate (Levshina 2022, Rappaport Hovav 2014, Wolff 2003).[10] The data coding procedure adopted this widely accepted perspective by counting causes realized as the subject in the causative variant as instances of an identified cause. Further cases of an identified cause from the corpus are given in (12). In (12a) the cause (Bannister) fulfills two roles: it serves directly as the object of the matrix verb permit, and indirectly, through indexing, as the external argument in the complement clause containing the verb break (Radford 1988, 1997); in (12b) and (12c), the prepositional phrase containing the cause modifies the verb phrase headed by the verb (melt and broke).

| a. | The record was broken by scientific training and pacing in which two first-class athletes sacrificed themselves to permit Bannister <to break the record>. (BNC W:non-ac:soc_science, A6Y-24) |

| b. | … these crystals melt in hot water. (BNC W:fict:prose, H8A-2435) |

| c. | The window broke from the pressure/from the explosion/from Will’s banging. (Heidinger and Huyghe 2024: 191, (23a)) |

The restriction to causes realized in the same clause where the change is specified excludes causes specified or hinted in the surrounding context from cases of identified cause. Instead, these causes were coded as recoverable causes, that is, causes that can be contextually identified. The following types of cause were regarded as recoverable causes: (i) previously mentioned cause, (ii) hinted cause, (iii) default cause, and (iv) type-inferable cause. The first two types are contextually identifiable based on information available from the immediate discourse context, whereas the latter two types are considered recoverable because they are part of what discourse participants know about the way the world works.

Previously mentioned cause. A cause can be recoverable when it has been established in the surrounding context, that is, in the clauses or sentences preceding or following it. These are cases such as those illustrated in (10b) and (11a) above, wherein the cause of the change mentioned in the preceding clause licenses the noncausative variant of the verb. In (11a) the causing action was performed unintentionally, while in (10b) it was performed intentionally.

Hinted cause. A cause can also be recoverable when the cause might be subtly suggested in the surrounding context. An example is (13) uttered in the context of an event with many tables and food served by waiters. In such contexts, a noncausative variant may be used to describe the event.

| As the night wore on, <the tables slowly cleared> and there was nothing left for the late comers to eat. (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 26, (81)) |

Default cause. Another type of recoverability, as noted by Rappaport Hovav (2014), is the default cause, defined as causes that are part of discourse participants’ common knowledge about the way the world works: they are recoverable by default. Examples of a default cause of the event are causes of changes which occur in the normal course of events such as the lengthening of hair, the growth of a tree, and the clearing of the sky. According to Rappaport Hovav (2014: 24), one attribute that distinguishes default causes from identified causes is the presence of multiple simultaneous causes for changes that occur as part of the normal course of events. Consequently, it is typically difficult to pinpoint a single, isolatable cause for such changes. When the cause is recoverable by default, the use of the causative variant would be odd.

Type-inferable cause. Another type of cause that is recoverable from world knowledge about the properties of eventualities is termed a type-inferable cause. An example with a type-inferable cause is given in (14). The when-clause in this example describes the closure of a hospital effected through the involvement of an agent who can be inferred to be typically responsible for such an event, namely, the hospital’s owner (see also (9) above). The precise identity of the agent is unimportant and need not be specified. This seems to be the reason for the general avoidance of the type-inferable cause in causative uses, although it is found in agentless passives (refer to Thompson [1987: 499] for further discussion).

| Careful plans have been made for these people so that when <the hospital eventually closes> they will not find themselves on the streets. |

| (BNC W:non-ac:polit_law_edu, HH3-9982) |

The noncausative variant may also be appropriate when neither speaker nor the hearer is aware of the ultimate cause of the event. The following types of cause were considered unknown causes (UCs): (i) cause from a distance, (ii) cause for a gradual change, and (iii) unidentifiable cause.

Cause from a distance. As noted by McCawley (1978), the choice of the verbs come and go determines the orientation of the speaker: in (15) the speaker is probably positioned in the lunchroom. Consequently, this example allows the hearer to infer that the speaker does not know how the door was opened.

| <The door of Henry’s lunchroom opened> and two men came in. | ||

| (McCawley 1978, cited in Rappaport Hovav 2014: 22, (59a)) |

Cause for a gradual change. Another type of unknown cause is the cause for a gradual change discussed by Rappaport Hovav (2014). Consider (16):

| With the 1929 stock market crash, <skirts lengthened> but kept their narrow silhouette, with longer waistlines. (Rappaport Hovav 2014: 27, (83)) |

This sentence does not describe a change in the length of an individual skirt, but rather a change in the kind of skirt. It reports a situation in which, over time, there are a variety of instantiations of the kind, and when comparing one to another over this period, the length is seen to increase. It is likely that multiple causes (and reasons) contribute to the gradual change in the kind, which are generally diffuse and not uniquely identifiable.

Unidentifiable cause. In numerous instances, an identifiable cause could not be discerned and the available contextual information did not indicate the cause of a state change. These instances, characterized by unclear and unidentified causes due to insufficient information, were categorized as cases of unknown cause. An example with an unidentifiable cause is given in (17).

| People can enjoy reading about you even if they don’t like your music and if enough of them do, it improves your chances of more coverage the next time you need it. … Although the total press coverage of pop music increased dramatically over the last ten years, <the quality hasn’t improved> and the power of music papers to make and break an artist has greatly dissipated. |

| (BNC W:misc, A6A-449) |

From the immediate discourse context, it is apparent that the influence of music papers augmented the probability of obtaining more press coverage for artists and their music. However, the reason for the persistently unimproved quality of pop music, despite a significant increase in total press coverage, remains unclear.

Determining whether the cause for a change is a recoverable cause or an unknown cause required a careful analysis of the context. We used the CQPweb interface of the BNC to access preceding and subsequent context. CQPweb (Hardie 2012) is an online corpus analysis tool that serves as an interface to the corpus workbench software (CWB) and its effective corpus query processor (CQP) search utility (https://cqpweb.lancs.ac.uk). The most convenient method to view context is by searching for query expressions and concordancing the results. As shown in Figure 6, by default, the CQPweb system displays only the immediate text unit containing the search element (in this case, But the age structure within this total has changed).

Viewing a concordance with surrounding sentences in the CQPweb.

To examine more context, one can simply click on the search element (underlined and center-aligned in the concordance line). This action opens a new window displaying the entire text from which the search element originates (Figure 7). This configuration enables reading the context immediately before and after the sentences (highlighted in the window).

Displaying more context in the CQPweb.

3.2.3 External causality

This variable adapts of the distinction between internal versus external causation as discussed in Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995), capturing whether a change of state comes about in a natural circumstance or not. Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) consider this distinction relevant for the lexical representation of verbs, which encodes the conceptualization of events, introducing categories for verbs they label externally and internally caused. The major classes of internally caused verbs in their analysis include (i) a variety of activity verbs, (ii) verbs of emission; and (iii) a subset of change of state (COS) verbs such as bloom, blossom, corrode, decay, erode, rust, and wither.[11] Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995: 97) cite this class of COS verbs as nonalternating; nonetheless, corpus studies by McKoon and Macfarland (2000) and Wright (2001, 2002) reveal that these verbs are sometimes found in causative variants.

Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) provide two partially overlapping yet essentially distinct characterizations of internal causation: (i) causation residing in the single argument, namely, the entity undergoing the change, and (ii) causation inherent to the natural course of development of the changing entity. However, it is not accurate to characterize internally caused COS verbs as describing events devoid of external causes, occurring solely due to the inherent properties of their arguments. For instance, when a flower blooms, factors external to the flower such as temperature, sunlight, and moisture are surely influential. On the other hand, flowers bloom in the natural course of events. Rappaport Hovav (2020: 228) argues that it is more accurate to characterize internally caused changes of state as those which come about in the changing entities as part of their natural development.

This characterization of internally caused changes of state can be straightforwardly applied to other alternating COS verbs. In this study, an internally caused COS is defined as a COS that comes about in the natural course of events as a result of the internal properties of the argument undergoing the state change; an externally caused COS is defined as a COS induced by an external cause, which is not inherent to the entity’s natural development. Unlike internally caused changes, externally caused changes of state occur with the intervention of an external causer, including agents, nonintentional acts, instruments, and abstract processes, or with a significant input of external force or energy. These various types of external causers correspond to different types of external causation and collectively represent a continuum along which different languages establish their limits on possible external causers (Wolff et al. 2009).

The meaning of the investigated verbs is compatible with descriptions of either internally or externally caused changes of state though they may vary in the likelihood of describing certain types of changes. As noted by Rappaport Hovav (2020) and others, the exact nature of the change is largely determined by the chosen theme of the change of state. In this study, the external causality of a COS was assessed by examining two aspects of the syntactic context: (i) the choice of internal arguments found with the verbs, and (ii) modifiers of the arguments and the verb phrase. For instance, naturally occurring changes of state, such as the clearing of the sky and the opening of clouds, have been considered internally caused changes of state. Such changes generally occur independent of human control, although certain environmental conditions and natural forces can regulate the onset and rate of change by acting physically on the theme of the change of state.

Changes in concrete or abstract entities are more subject to human control. As such, when verbs take concrete entities or abstract entities, the nature of the change was determined by analyzing modifiers of the arguments and the verb phrase, as well as the choice of both internal and external arguments. For example, nonagentive melting events like the melting of ice or ice cream at room temperature have been counted as instances of internally caused COS. On the other hand, the melting of substances or objects such as wax and metal by heating has been counted as instances of externally caused COS. Melting of someone’s heart has also been considered a description of an externally caused COS, as this change does not occur as part of the natural progression of the theme of the change of state.

To illustrate further, the natural drying of hair, sweat, or a towel has been regarded as a description of an internally caused drying event. However, drying them by a machine, in the sun, or in front of a fire requires external heat and thus has been regarded as a description of externally caused drying events. Further examples of causative and noncausative uses of the verbs studies, describing internally and externally caused changes of state, are given in (18) and (19), respectively.

| a. | This railing is just outside my door. On a very cold winter morning before <the temperature melted the ice>, I was able to capture this image. |

| (Rappaport Hovav 2020: 242, (61)) | |

| b. | <Sweat began to dry> and strength seeped back into my limbs. |

| (BNC W:misc, AT-2138) | |

| c. | When <the ice melted>, some shallow lakes remained where boulder clay blocked old river courses. (BNC W:non-ac:soc_science, B1H-2052) |

| d. | <The sugars dissolve into the water> and the sweet liquid, called wort, is pumped to a copper. (BNC W:misc, A13-63) |

| a. | Their warm Spanish eyes in luxuriant black eyelashes melted my heart. |

| (BNC W:biography, AC6-205) | |

| b. | The Central Bank has frozen all remittances of profits, dividends and interest. (BNC W:pop_lore, ABF-1212) |

| c. | Sarah let Roy carry Benny into the house, and as she looked at Janine comforting her only daughter, <the ice in her heart melted>. Going to the girl, she put her arm around her shoulders. (BNC W:fict:prose, CR6-982) |

| d. | I picked up a young bird which one of my cats had caught; I held it in my hands in the hope that it might survive. The shock had been too great, though, and its heart went into convulsions. And then came a moment when I was aware that <its personal life was dissolving>, and I could somehow perceive that a greater life, a kind of group ‘bird soul’ was taking over … (BNC W:non_ac:humanities_arts, CCN-1379) |

If it could not be determined contextually whether the change of state was internally or externally caused, a third category ‘unclear causality’ was added. Instances of unclear causality were excluded from the samples of relevant tokens that were subsequently analyzed.

In line with previous studies, one can expect that internally caused changes of state are more associated with noncausatives, while externally caused changes of state are more typically associated with causatives.

The influence of these factors discussed in this section will be examined through the following hypotheses:

| Hypothesis 1: Intentionality (nature of causing action) |

| a. | The causative is more likely if the causing action is intentional. |

| b. | The noncausative is more likely if the causing action is nonintentional. |

| Hypothesis 2: Contextual identifiability (type of cause) |

| a. | The causative is more likely if the cause is clearly singled out and identified. |

| b. | The noncausative is more likely if the cause is recoverable or unknown. |

| Hypothesis 3: External causality (kinds of change of state) |

| a. | The causative is more likely if the COS described by the sentence is externally caused. |

| b. | The noncausative is more likely if the COS described by the sentence is internally caused. |

Since these variables overlap and are interrelated, it would be impossible to determine from individual examples whether the choice of variant can be attributed to one variable or another. To test the simultaneous effects of these predictors, we used three popular multivariate methods in corpus linguistics: conditional inference trees, conditional random forests (Levshina 2015, 2016, 2020, 2022; Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012) and mixed-effects logistic regression (Baayen 2008; Baayen et al. 2008; Jaeger 2008, 2011). These methods are described in the following section.

4 Results

This section introduces the statistical methods and reports the results of our descriptive statistical analysis (Section 4.1) and multifactorial analyses (Sections 4.2 and 4.3).

4.1 Descriptive statistics

We analyzed the distribution of the causative and noncausative variants in relation to the three factors described in Section 3.2.[12] Figure 8 shows the proportional distribution of the two variants and the absolute frequencies according to the levels of the factors.

Proportional distribution of alternation variants by intentionality, cause identifiability and spontaneity.

Intentionality. The proportional distributions in Figure 8 confirm our hypotheses regarding the influence of intentionality of causation as posited in (20). We can see that the causative variant is proportionally preferred over the noncausative variant when the causing action is intentional, aligning with (20a). Conversely, when the causing action is nonintentional, the noncausative is preferred, as outlined in (20b).

Recall that the category of nonintentional causes encompasses inanimate causes and nonintentional animate causers. While animates may act intentionally or unintentionally in precipitating a particular event, inanimates lack the capacity for intentional action. This difference between inanimate causes and animate causers suggests that inanimate causes are more closely linked to nonintentional causation. To investigate whether this is the case in our data, we have further analyzed nonintentional causes that are explicitly expressed in the clause of the COS verb or identifiable contextually by their ontological class. Figure 9 shows the frequency distribution of nonintentional causes among the two variants based on their animacy.

Frequency distribution of animate and inanimate nonintentional causes.

We can see that there is a marked asymmetry between inanimate causes and animate causers: nonintentional causes are predominantly inanimates in both variants. There were merely 43 instances of a nonintentional animate causer realized as a causative subject, constituting only 6.56 % of the 655 causatives with a nonintentional causer subject in the dataset; the number of noncausative instances with a nonintentional animate causer totals 148, accounting for 7.86 % of all 1,884 noncausative uses with a nonintentional causer. All these cases are recoverable causes either overtly expressed in the local linguistic context or hinted at in the surrounding context, as exemplified in (11a) and (13) above, respectively. While inanimate causes can be expressed as adjuncts in noncausatives as illustrated in (12c) above, animate causers cannot (Alexiadou and Schäfer 2006: 41):

| *The window broke from John. |

This difference between inanimate causes and animate causers is consistent with the proposal that inanimate causes are more closely associated with the noncausative variant than are animate causers (Alexiadou and Schäfer 2006; Heidinger and Huyghe 2024). Further evidence supporting this is provided by analyzing the realization patterns of prototypical examples of inanimate causes – natural forces and conditions. We analyzed a total of 215 instances of natural forces and conditions identified or identifiable as causes, examining the frequency of their realizations and the cause types. The results of this analysis of natural causes are summarized in Figure 10.

Frequency distribution of subtypes of natural causes.

Figure 10 shows that natural causes predominantly appear in the noncausative variant. Concerning natural causes in noncausatives, the discrepancy between RCs and ICs (adjunct PPs in noncausatives) is striking: RCs significantly outnumber ICs. When assessing the relative frequency of subtypes of RCs, it was found that 102 instances were default causes (DCs), and 53 instances were RCs mentioned or suggested in the local linguistic context. It is noteworthy that noncausatives with these RCs take up 80.31 % of all instances of noncausatives with a natural cause. Examples of noncausatives with recoverable and identified natural causes from the BNC are given in (24) and (25), respectively. We revisit to these findings in Section 5 and propose an efficiency-based explanation for them.

| a. | <Early fog had cleared> and the airport manager and I were standing on the tarmac lining up the motorcade when my car phone rang. |

| (BNC W:commerce, ADK-1948) | |

| b. | <The store burned> because, some minutes after 11 am on 25 April, a 6.9 earthquake heaved the town, our houses and the store briefly off the ground and, in the store, an electric coffee pot overturned. |

| (BNC W:non_ac:polit_law_edu, CAK-814) |

| a. | In the midst of summer when you came out, <your eyes burned with sunlight> and your small meaty smooth arms and legs were stung by the pavement’s heat. (BNC W:misc, A6C-46) |

| b. | Ambitions soon melted under an unseasonally hot sun. |

| (BNC W:pop_lore, A15-394) |

Contextual identifiability. The proportional distributions in Figure 8 also confirm our hypotheses regarding the influence of contextual identifiability as discussed in (21). We observe that the causative variant predominates when the cause is clearly singled out and identified; specifically, when the cause and the change are specified in the same clause (NRC-IC). Conversely, in cases where the cause is either recoverable or unknown, the pattern shifts: the noncausative prevails if the cause is recoverable (RC), and it is exclusively selected when the cause is unknown (NRC-UC). There are 49 instances of causative uses with a recoverable cause, constituting merely 3.02 % of the total 1,620 causative instances in the dataset. Predominantly, such cases of recoverable cause subjects in the causative uses of the alternating verb in our dataset are omitted subjects of finite verbs, which refer back to the subject in the immediately preceding sentence or to a salient entity introduced earlier in the discourse, as illustrated in (26).[13]

| a. | Crushed a snail? (BNC S:conv, KDE-4073) |

| b. | Should have defrosted him earlier. (BNC W:fict:prose, F9X-1688) |

External causality. The proportional distribution of the realization of internally caused changes of state is in line with our hypothesis in (22b). Figure 8 shows that the noncausative is the categorical choice when describing an internally caused COS. There are no attested instances of causative uses describing an internally caused COS within our dataset. As already mentioned, we excluded instances of transitive uses of the analyzed verbs that are not causative. Examples of the transitive uses removed from the final dataset are given in (27):[14]

| a. | The seeds you’ve planted are sprouting the tenderest of young green shoots. |

| (BNC W:fict:prose, HGN-2707) | |

| b. | Already the wounds sprout new growth. (BNC W:fict:prose, CM4-1549) |

However, the proportional distribution of the realization of externally caused changes of state is not consistent with our hypothesis regarding the influence of externally caused changes of state as outlined in (22a). As shown in the figure, the noncausative variant is marginally favored over the causative variant even when the sentence describes an externally caused COS.

In the subsequent subsection, we will use conditional inference trees and conditional random forests in order to identify the set of independent variables that significantly differentiate between the two variants.

4.2 Tree and forest analysis

Conditional inference trees (CITs) and conditional random forests (CRFs) were introduced to linguistic analysis in a paper by Tagliamonte and Baayen (2012) and have been fruitfully used in models of linguistic variation (Hundt et al. 2021; Levshina 2015, 2016, 2020, 2022; Szmrecsanyi et al. 2016). These methods are non-parametric permutation approaches that do not assume a specific distribution of the data, but rather build a model through resampling from the input.

CITs are methods for regression and classification based on recursive partitioning. They split the data recursively into smaller subsets based on predictor variables that co-vary most strongly with the outcome. For each binary split, the data is evaluated for the predictor that best preserves the homogeneity of each split (e.g., all causatives and all noncausatives) at a certain significance level. This splitting process continues until no further splits can significantly increase the subset’s homogeneity with respect to the outcome variable. Despite their utility, single trees have the disadvantage that they very much hinge on the dataset at hand and are hence subject to a high degree of variability. Conditional random forests (CRFs) mitigate this by resampling across a predefined number of trees through a conditional permutation scheme and thus particularly robust to, for instance, predictor collinearity (see Levshina [2020] for details).

CITs and CRFs can be particularly useful in situations where the use of parametric methods (in particular, regression models) may not be suitable, such as in situations characterized by ‘small n, large p’, (where n is the number of observations and p is the number of predictors), complex interactions, non-linearity, and correlated predictors (Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012). They are also noted for their robustness in the presence of outliers. Furthermore, CITs facilitate the intuitive interpretation of complex interactions involving more than two predictors.

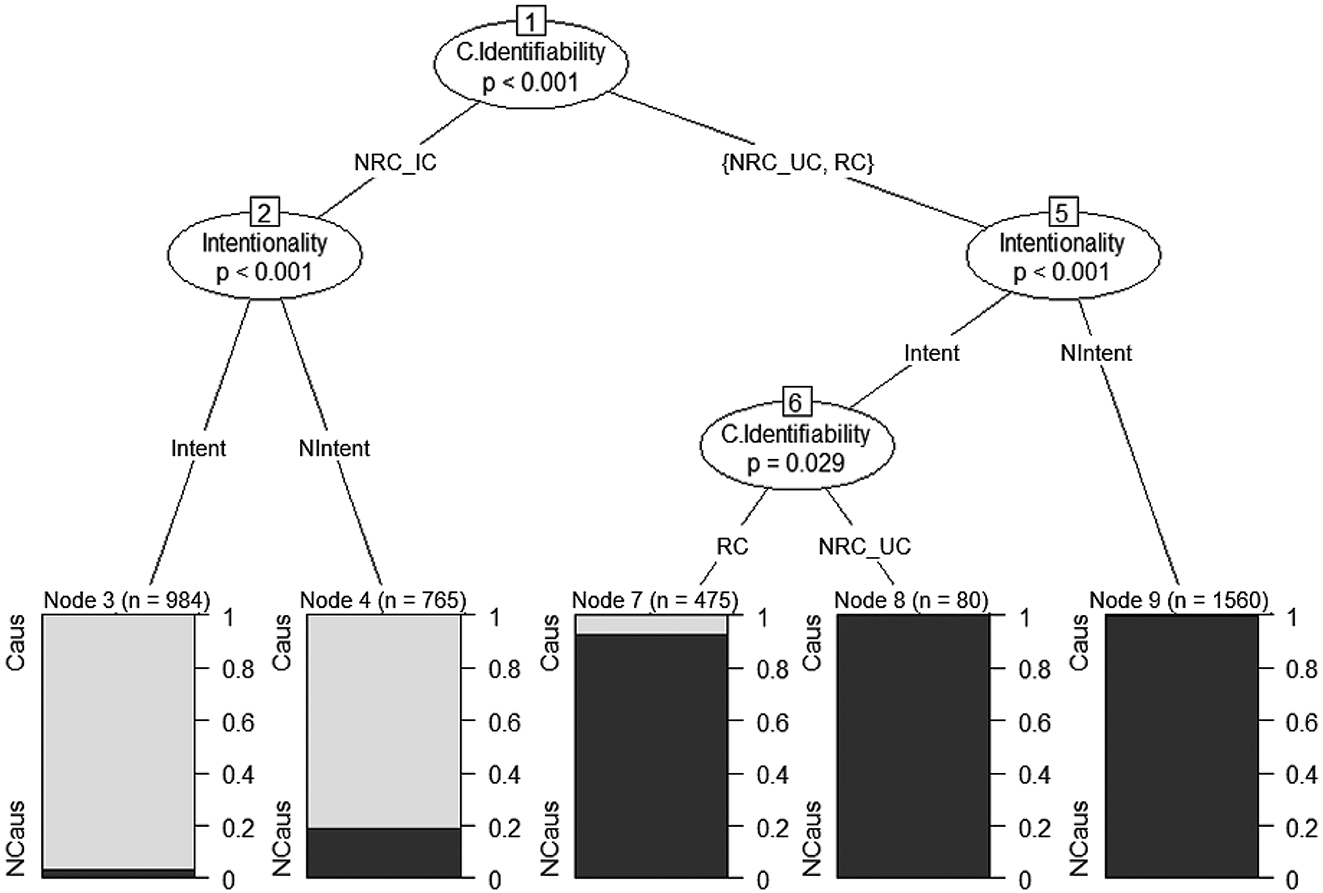

Figure 11 shows an individual CIT fitted to the data using the function ctree ( ) in the party package in R. The ovals highlight the names of the variables selected for the best split, along with the corresponding p-values. The levels of the variables are specified on the ‘branches’. The bar plots at the bottom (‘leaves’) display the proportions of the two variants in each end node (‘bin’), which contain all observations with a given combination of features. The number of observations in each bin is noted in parentheses above the boxes.

Conditional inference tree of the variant choice.

The plot is presented with all significant splits at the 0.05 level and should be interpreted from the top down.[15] The interpretation proceeds as follows. First, the algorithm looks for the variable most strongly associated with the variant (causative or noncausative). This variable is contextual identifiability (see Node 1). It then divides the data along this variable into two subsets, separating observations with NRC_ICs (cases on the left side of the tree) from those with RCs and NRC_UCs (cases on the right side of the tree). We observe that causative situations involving NRC_ICs are expressed predominantly with a causative (Nodes 3 and 4), whereas those involving RCs and NRC_UCs are realized predominantly as a noncausative (Nodes 7, 8 and 9). Subsequently, the algorithm seeks another variable significantly associated with the variant. On both sides of the tree, the subsequent split occurs with the variable of intentionality (Nodes 2 and 5), indicating that in cases where the cause type is similarly identifiable, the intentionality of the causer becomes relevant. Descending the left-hand branch from Node 2, where the cause is an NRC_IC type, the proportion of causative outcomes is higher in situations of intentional causation (Node 3: 96.7 %) compared to nonintentional causation (Node 4: 80.9 %). Conversely, on the right-hand branch from Node 5, where the cause is recoverable or unknown, the proportions in the bar plots in the node leaves show that noncausative is uniformly preferred in instances of intentional causation with NRC_UCs (Node 8: 100 %) and that noncausative is more prevalent in instances of nonintentional causation (Node 9: 99.2 %), relative to intentional causation with RCs (Node 7: 92.2 %). Note that the variable external causality is not used in the data splitting because it does not significantly correlate with the outcomes (with p < 0.05) in the model. These results support the conclusion that contextual identifiability is the most predictive factor, followed by intentionality, while external causality appears to have a minimal impact in differentiating between the two variants.

The results of the CIT analysis were corroborated by the CRF analysis, where a CRF consists of an ensemble of multiple CITs. In addition to measures of classification accuracy, CRFs facilitate conditional variable importance scores, which show how important each variable is in predicting the outcome (in our study, the use of the causative and noncausative variants), taking into account all other variables and their interactions. To compute this measure for a predictor, the algorithm averages results across numerous trees and measures the reduction in predictive capability when the predictor is randomly permuted. As explained in Levshina (2016, 2020), a notable distinctive feature of CRFs is their ability to ascertain the conditional variable importance measures, offering certain benefits over non-conditional approaches (Strobl et al. 2007). Specifically, these measures are unbiased towards correlated predictors and with regard to the number of categories in a categorical variable. Furthermore, CRFs are superior to other popular random forest methods as they make predictions by retaining information about individual observations in each tree without pruning the trees. Consequently, terminal nodes with a high count of observations exert more influence because they provide more data points for calculating predicted values.

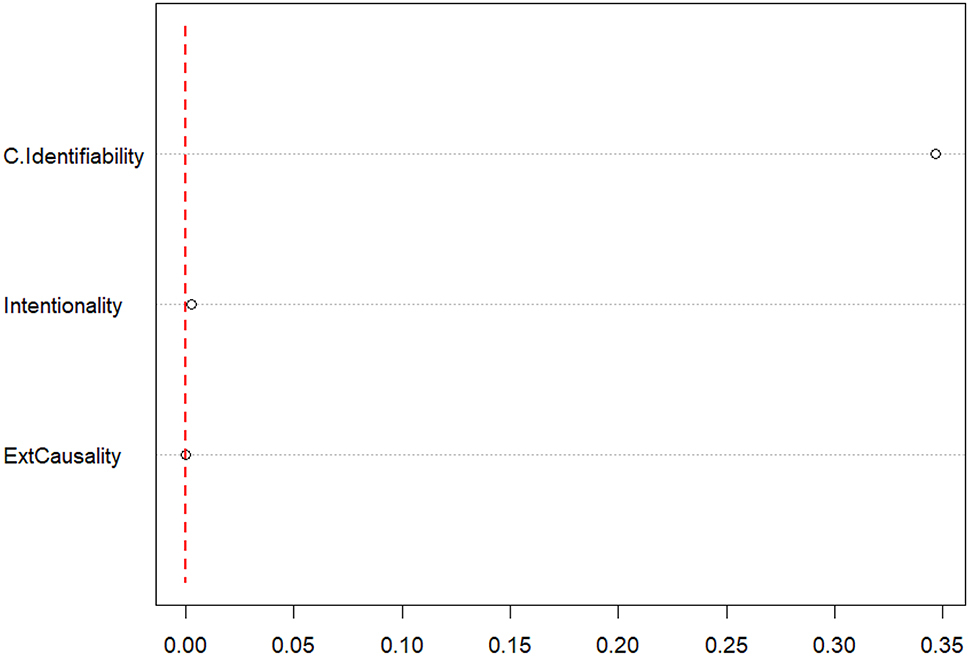

We created a random forest comprising 500 trees, and subsequently computed the variable importance scores.[16] The variable importance scores are presented in Figure 12 in order of decreasing importance. The horizontal axis represents the conditional variable importance (CVI) for each predictor. The dashed line separates the important scores on the right from the unimportant ones on the left. If a variable is irrelevant, its importance values vary around zero.

Conditional variable importance (CVI) scores of the variables based on CRFs.

Figure 12 shows that contextual identifiability is the most important predictor for the choice between the two alternation variants (CVI score: 0.337). This variable also predominantly facilitated the splits in the CIT. Consistent with the results of the CIT analysis, intentionality emerges the second most important variable (CVI score: 0.0036). Notably, external causality does not seem to have any discriminatory power in the CRF.

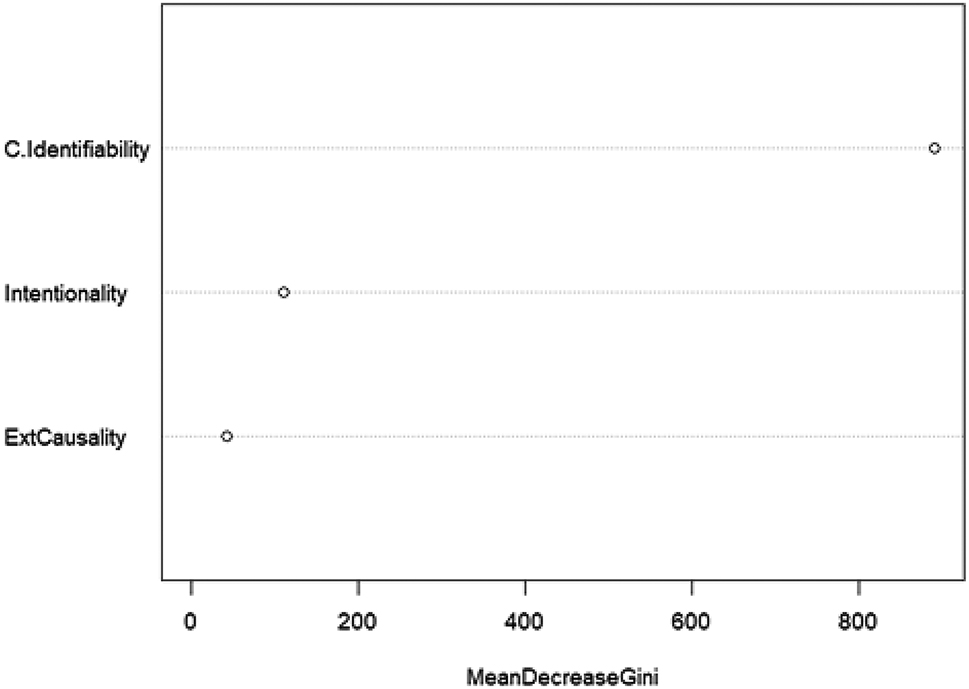

We compared the variable importance scores obtained from the CIF analysis with those derived from non-conditional random forests. The mean decrease accuracy plot in Figure 13 demonstrates that all three variables play a role in random forests:[17] with contextual identifiability being the most important predictor, followed by intentionality and external causality.

Gini scores of the variables based on RFs.

To summarize, the results of the CIT, CRF and RF analyses suggest that contextual identifiability is the most predictive factor, whereas the other two variables are less useful for distinguishing between the two variants. In the next subsection, we will use mixed-effects logistic regression modeling to gain a more robust insight into the size of the predictors’ effect, their interactions, and random effects (verb specific effects on variation).

4.3 Mixed-effects logistic regression model