Abstract

Loanwords are lexical terms borrowed from foreign languages by transliterating the original sound of the borrowed words with the recipient language’s consonants and vowels. This paper focuses on lexical borrowing in the Korean language from a diachronic perspective. Based on approximately 9,500 Korean loanwords extracted from a corpus of women’s magazine articles of residential sections (the Korean Contemporary Residential Culture Corpus), we investigated the alteration of loanword usage from 1970 to 2015. Having introduced our definition of Korean loanwords in phonological and morphological terms, we performed statistical analysis particularly with type/token frequency and cultural/core loanwords, along with semantic analysis with Period Representative Loanword (PRL). We argue that, in addition to its gradual and rapid increase over time, Korean loanword usage underwent a remarkable evolution in the 1990s.

1 Introduction

Social contact brings changes to a language. In the case of large-scale social contact such as war or compulsory unification, the linguistic incidence can be so radical to drive languages to extinction, but in most cases, the linguistic influence is limited to words (Calvet 1998, 1999; Crystal 2000; Hagère 2000). Social contact often brings about a demand for new lexical items in the recipient language to facilitate the diffusion of imported objects or concepts. Existing candidate words in the recipient language may be reused through semantic extension or reduction; furthermore, new lexical items such as nurik̕un in Korean, meaning ‘netizen’ in English, are created if there are no suitable words in the language. Names are also borrowed directly from the donor language along with the designated object or concept. For instance, when ‘island kitchen’, an object that did not exist in Korea, was introduced to Korean society, its English name was also adopted. It is called aillɛndɯ kʰitʃʰin in Korean, which is transliterated from ‘island kitchen’ in English. Lexical items transferred from a donor language to a recipient language by transliteration are called werɛʌ in Korean, which corresponds to loanwords in English.[1]

In this study, we attempt to investigate the diachronic evolution of lexical borrowing in the Korean language, by analyzing approximately 9,500 Korean loanwords extracted from a corpus of magazine articles published from 1970 to 2015. As one of the rare corpus-based studies of Korean lexical borrowing, we will illustrate how the Korean loanword usage has been changed through a statistical analysis of corpus data and its semantic interpretation.

This paper comprises five sections. In Section 2, we introduce the definitions and linguistic features of Korean loanwords. After describing our corpus data and loanword selection (§ 3), we present our statistical approaches based on type/token frequency and cultural/core loanword analysis (§ 4). Finally, we suggest a semantic interpretation of the diachronic changes in Korean loanwords with Period Representative Loanword (PRL) and discussion (§ 5 and § 6).

2 Brief presentation of Korean loanwords

According to Tadmor (2009: 55), lexical borrowing is universal to the extent that the average borrowing rate is as high as 24.2 % in most languages. The Korean language is not an exception, having borrowed many words from languages such as Chinese, Mongolian, Manchu, and Jurchen, spoken since ancient times in neighboring regions. In the first half of the 20th century, diverse words were introduced from the Japanese language during the Japanese colonial era. After the Korean Liberation in 1945, many lexical items were borrowed from English due to political relations between Korea and the US at the time (Cho 2014).

With respect to lexical representation, Korean words are distinguished into three categories: native Korean words, Sino-Korean words, and loanwords. Unlike native Korean words, Sino-Korean words can be represented using Chinese characters, and are divided into indigenous words and loanwords. Indigenous Sino-Korean words are invented and used mainly in Korea, whereas Sino-Korean loanwords are imported from China or Japan. For example, p'yŏnŭijŏm (便宜店) ‘convenience store’ is an indigenous Sino-Korean word used mainly in Korea, whereas sahoe (社會) ‘society’ is a Sino-Korean loanword imported from Japan. Loanwords are lexical terms borrowed from foreign languages by transliterating the borrowed words’ original sound, such as pilting ‘building’, moderhausŭ ‘model house’, sʰɯtʰail ‘style’ and k'ŏt'ŭn ‘curtain’. In our study, we regarded as loanwords the lexical items satisfying the following constraints:

Phonological constraints

Loanwords are transliterated using Korean consonants and vowels. We frequently find two or more phonological allomorphs; for example, the English word ‘antique’ is borrowed in Korean to be written as ɛntʰikɯ or ɛntʰik̚. We accept all phonological variations as loanwords, considering while using loanwords, speakers tend to not be too attentive to their orthographical representation (Mudrochova 2020). Furthermore, allomorphs designate the same object or concept regardless of whether they are differentiated in their orthographical form.

The lexical items represented using Chinese characters are excluded. It is very difficult to rebuild the transliteration process of all Sino-loanwords, as in some cases, it is necessary to retrieve the original sound in the donor language of words borrowed hundreds of years ago. We concentrate our discussion on loanwords that are not represented using Chinese characters, including those borrowed from English, French, German, and so on.

Morphological constraints

Loanblends (Haugen 1950), which employ the combination of a loanword and a native or Sino-Korean word, are excluded. For example, aillɛndɯ ɕik̚tʰak̚—composed of aillɛndɯ, transliterated from ‘island’ in English, and of ɕik̚tʰak̚, a Sino-Korean word meaning ‘table’—is excluded, whereas aillɛndɯ kʰitʰin, transliterated word by word from ‘island’ and ‘kitchen’ in English, is considered a loanword.

As Moravcsik (1975) mentions, verbs are not usually borrowed as they are, but as nouns, which then undergo a verbalization process inherent to the recipient language. Based on this idea, in the loanword category, we account for verbs or adjectives consisting of a loanblend with the Korean verbalizing suffixes, -hada ‘do’ or -tweda ‘become’, as long as they indicate the predicate value of borrowed words. For example, tɯraibɯhada (English verb ‘drive’ + Korean active suffix -hada), mɛtsʰitweda (English verb ‘match’ + Korean passive suffix -tweda) and romɛntʰikʰada (English adjective ‘romantic’ + -hada) are considered loanwords in our study.

Compound nouns are treated as a composition of morphologically independent nouns. For example, udɯ pɯllaindɯ ‘window shade made of wood’ is separated into udɯ ‘wood’ and pɯllaindɯ ‘window shade’ in the morphological analysis. Therefore, each noun is treated as a separate loanword in the morphological analysis.

Constraints regarding the part of speech (POS)

In our study, loanwords are confined to words belonging to the following POS: common nouns, proper nouns, verbs, and adjectives, which comprise the most significant proportion of loanwords according to Haspelmath (2009).

3 Data description

3.1 Corpus data

After observing loanwords in 41 different languages, Tadmor (2009: 64–65) discovered that most languages tend to borrow more words from similar fields with resistance. According to this study, the three semantic fields most affected by lexical borrowing are religion and belief, clothing and grooming, and housing. These fields are also regarded as the domains most affected by social and cultural contact. The Korean Contemporary Residential Culture Corpus (KCRCC),[2] on which our study is based, concerns the third semantic field, housing. It consists of 749 articles from the residential sections of 5 Korean women’s magazines published between 1970 and 2015. The titles of the magazines are Tsubusʰɛŋhwal ‘Housewives Living (STYLER)’, Yʌsʰʌŋdoŋa ‘Women’s Dong-A’, Yʌsʰʌŋdzuŋaŋ ‘Women’s JoongAng’, Yʌwʌn ‘Yeowon’, and Hɛŋbogi kadɯkʰan dzip̚ ‘A Home Full of Happiness’. They had a wide range of subscribers during the period of publication. According to Cartier (2019) who analyzed all the articles published by the 250 French press outlets from 2015 to 2017, women’s magazines such as Elle and Grazia are the second most productive media for loanwords, after the local versions of the international press outlets, such as Huffington Post and Slate. Naturally occurring and irrelevant to interlinguistic translation, women’s magazines are good resources for observing of the diachronic evolution of lexical borrowing.

To build our corpus, we collected all the articles from the related sections every five years between 1970 and 2015. Magazine articles are commonly organized using a section head, headline, standfirst, body text, pictures, image captions, etc. We selected only the headline, standfirst, body text, and captions to build the corpus, while excluding the section heads, which define the subject area (Figure 1).

An example of the magazine articles. Yʌsʰʌŋdzuŋaŋ ‘Women’s JoongAng’. 2010.11: 700–701.

The corpus consists of 565,824 ʌdzʌl,[3] which accounts for a total of 36,715 word-types and 1,211,017 word-tokens.[4] We divided our corpus into five-year intervals to obtain 10 periods, each of which is characterized by the data in Table 1.

Description of the Korean contemporary residential culture corpus.

| Article | ʌdzʌl | Word-type | Word-token | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 55 | 64,103 | 12,563 | 136,682 |

| 1975 | 48 | 38,732 | 8,812 | 84,360 |

| 1980 | 57 | 39,956 | 8,916 | 87,508 |

| 1985 | 60 | 52,589 | 10,298 | 116,853 |

| 1990 | 72 | 89,795 | 13,440 | 200,186 |

| 1995 | 90 | 60,111 | 10,139 | 129,272 |

| 2000 | 94 | 54,412 | 8,215 | 115,242 |

| 2005 | 116 | 54,262 | 8,408 | 112,556 |

| 2010 | 83 | 57,523 | 10,254 | 117,580 |

| 2015 | 74 | 54,341 | 9,905 | 110,778 |

| Total | 749 | 565,824 | 100,950 | 1,211,017 |

3.2 Loanword selection

It is difficult to distinguish true borrowing from nonce borrowing which seems to be used only in a coincident and incoherent manner by specific speaker groups (Donohue and Wichmann 2008; Poplack and Dion 2012; Sablayrolles 2019). The process of identifying loanwords in this study was implemented as follows: First, we extracted 5,582 loanwords with reference to the Korean Standard Unabridged Dictionary edited by the National Institute of Korean Language. However, dictionaries were found to be insufficient sources for referencing since their list of loanwords was not exhaustive and numerous phonological variations had not been considered. Then, we organized a committee of six linguists, including the authors of this paper. All the members reviewed each potential loanword independently, and then participated together in the crosscheck evaluation to determine the true loanword list. Through this process, various commonly used loanwords such as pʰɛbɯrik ‘fabric’, pʰɯllawʌ ‘flower’, tsʰeʌ ‘chair’, and raipʰɯ ‘life’ were identified, in addition to proper noun loanwords referring to materials (e.g., tsollatʰon ‘zolatone’) and brand names (e.g., ikʰea ‘IKEA’). Finally, with the 3,952 loanwords additionally identified, we obtained a more comprehensive list consisting of 9,534 loanwords. Table 2 lists the number of types and tokens of the collected loanwords.

Number of types and tokens of loanwords.

| 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | 704 | 501 | 466 | 734 | 939 | 954 | 904 | 1,207 | 1,357 | 1,768 |

| Token | 1,951 | 1,495 | 1,386 | 2,814 | 5,471 | 5,338 | 5,732 | 8,491 | 7,662 | 8,884 |

By classifying loanwords in terms of POS, we found that almost 90 % of the loanwords are common nouns. This result is in accordance with the observations presented by Muysken (1981), Haspelmath (2009) and Winford (2010), where the proportion of nominal loanwords is significantly higher than that of verbs or adjectives.

As shown in Figure 2, our corpus reveals that the distribution of POS in content words and loanwords is not identical. The proportion of POS in content words is ordered in such a way that common nouns > verbs > adjectives > proper nouns, whereas for loanwords, it is ordered as follows: common nouns > proper nouns > verbs > adjectives. The proportion of verbs and adjectives in loanwords is so small that it is negligible. In other words, the Korean language tends to borrow mostly common nouns and proper nouns from other languages, while words belonging to predicative categories such as verbs and adjectives are rarely borrowed.

Ratio of each part of speech (POS) in content words and loanwords.

In fact, nouns are known to be borrowed more easily than other parts of speech in most languages (Moravcsik 1978; Myers-Scotton 2002; Whitney 1881). Nominal words receive thematic roles and their insertion in another language is less disruptive to its syntactic structure (Vinet 1996). Therefore, verbs used to be borrowed as if they were nouns (Haspelmath 2008: 7–8; Meillet 1921 [cited in Thomason and Kaufman 1988: 348]; Moravcsik 1975; Moravcsik 1978: 111–112). The Korean language is not an exception insofar as many predicative words in foreign languages are incorporated into nominal items in Korean before verbalization with -hada ‘do’ or -tweda ‘become’ (Jun 2014: 160–162) (cf. Section 2). For example, the English verb ‘match’ is borrowed in Korean to become the nominal word mɛtsʰi, which is then verbalized by verbal suffixation with -hada ‘do’ or -tweda ‘become’.[5]

4 Statistical analysis of Korean loanwords

4.1 Frequency

The frequency of loanwords gradually increased from 1970 to 2015 in our corpus. In Figure 3, the numbers on the straight and dotted lines indicate the proportion of loanword types and tokens, respectively, of all content words for each period. Both tokens and types of loanwords indicate a strong rising tendency, particularly since 1990. From 1990 to 1995, the ratio of loanword-tokens increased by 4.1 % pts., whereas it increased by only 1–2 % pts for each period from 1970 to 1990. As for loanword-types, the ratio remained between 6.5 % and 8.6 % from the period 1970 to 1990 and then drastically increased to 11.3 % in 1995. The ratios of loanword-types and loanword-tokens have increased continuously, reaching 22.7 % (type ratio in content words) and 21.3 % (token ratio in content words) in 2015. These values are very close to the average borrowing rate (24.2 %) proposed by Tadmor (2009).

Type and token ratio of loanwords in content words.

4.2 Standardized data analysis

The type-token ratio (TTR) is an extensively used measure of lexical diversity, but is easily affected by corpus size (Baayen 2001; Koplenig et al. 2019; Richards 1987; Tweedie and Baayen 1998). To prevent the corpus size effect, before calculating the TTR for each period, we standardized our data as follows. First, we created a subset of 84,000 tokens for each period regardless of the number of articles included, and segmented the subsets into 3,000-token subsets to calculate the average of types and tokens for each period. Figure 4 shows the average of types and tokens for 28 units of each period.

Average types and tokens of standardized data sets.

The standardized data of our corpus confirmed that both types and tokens increased considerably from 1990 to 1995. Tokens moderately increased in the span from 1,101 to 2,017 until 1990, and after a surge in 1995, they continued to grow, reaching 7,037 in 2015. The mean values of types ranged from 500 to 1,000 until 1990, and subsequently showed a notable increase.

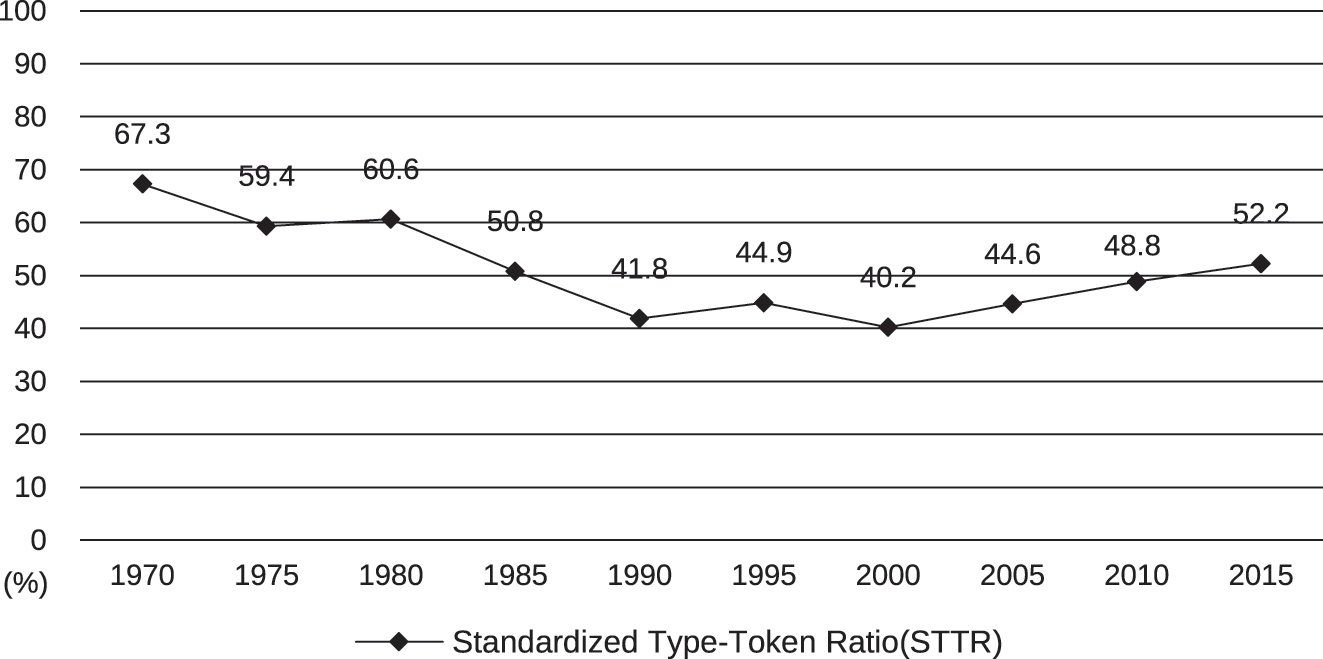

For more precise understanding, the standardized type-token ratio (STTR) were calculated from the given data as follows (Figure 5).

Standardized Type-Token Ratio (STTR).

From 1970 to 1985, STTR exceeded 50 %. Since 1990, when the measure fell to 41.8 %, it has not shown any further significant increase, remaining under 50 % except in 2015 when the measure was 52.2 %.

Given the increase in types and tokens and the decrease in the STTR observed in the magazine corpus in the 1990s, we can observe that Korean lexical borrowing underwent significant changes in the 1990s, along with a gradual increase in loanwords.

4.3 Comparative analysis

To verify our observations of the KCRCC, we also analyzed loanwords in the Chosun Ilbo Corpus, which was built and distributed by the Institute of Language and Information Studies (ILIS) at Yonsei University. Chosun Ilbo (tsosʰʌɲilbo), founded in 1920, is a major daily newspaper published in Korea.

We analyzed a subset corpus standardized by ʌdzʌl.[6] Each period has 3,000,000 ʌdzʌl, equivalent to 25,182,067–28,802,874 tokens. Applying the same method as we did to the KCRCC, we extracted content words and counted the types and tokens of loanwords in the set. Again, we discovered a remarkable rising tendency of loanwords in the Chosun Ilbo Corpus in the 1990s, which was observed in the KCRCC. Figure 6 shows our type/token analysis of the subset data of the Chosun Ilbo Corpus.

Number of types and tokens of subset data of the Chosun Ilbo Corpus.

The loanword-types which are represented by the line remained under 3,000 until 1990, and showed a marked increase in the period 1991–2000, reaching over 3,600. The loanword-tokens numbered approximately 300,000 until 1990, and after a surge in the period 1991–2000, they continued to number approximately 500,000.

The ratio of loanword-types and loanword-tokens in content words demonstrates the same tendency in Figure 7. Stable between 3.4 % and 3.7 % from 1971 to 1990, the ratio of loanword-types increased to 4.0 % in the period 1991–1995 and then to 4.4 % in the period 1996–2000. The ratio of loanword-tokens shows a similar pattern. It remained under 2.8 % until 1990, and then rose to 3.3 % in the period 1991–1995 and 4.2 % in the period 1996–2000. A significant change in loanwords is thus also revealed in the 1990s by the analysis of Chosun Ilbo Corpus.[7]

Type and token ratio of loanwords in content words.

Our analysis of the KCRCC and the Chosun Ilbo Corpus confirms that Korean lexical borrowing underwent important changes in the 1990s. This result is supported by the cultural/core loanword analysis of the KCRCC which we will present in the following section.

4.4 Cultural loanwords versus core loanwords

According to Myers-Scotton (2002), loanwords are of two kinds: cultural loanwords and core loanwords. The former indicates loanwords to designate newly imported objects or concepts that are unnamed in the recipient language, whereas the latter indicates those that duplicate existing native words. Core loanwords are distinguished from cultural loanwords in that they reflect a conscious action to choose foreign lexical items instead of alternative native words in a given context. Admitting that the community sharing language usage and its social meanings functions as “the ultimate mediator of borrowing behavior”, speakers not only use loanwords to fulfil the functional needs of vocabulary, but also select and use them according to the need of the social context in which they participate (Poplack 2018). This aspect is more effectively seen in relation to core loanwords than cultural loanwords, where the former imposes a speaker’s choice between loanwords and their alternative native words, whereas the latter was originally created to complement the absence of necessary lexical items in the recipient language community. In this section, we classified the loanwords of the corpus into a core borrowing group and a cultural borrowing group to explore ‘how many’ and ‘in which period’ core loanwords are more frequently used, compared to cultural loanwords. This approach effectively illustrates Korean speakers’ social attitudes toward loanword usage over time.

We implemented cultural/core loanword classification process for all the loanwords included in the corpus. Six linguists independently determined whether loanwords could be substituted for native words to conduct a primary classification, and then corrected the results according to the agreed principles, through cross-checking. For instance, names of objects introduced with the advent of new electronic devices, such as kʰʌmpʰyutʰʌ ‘computer’ and odio ‘audio’, or the names of tools and materials used in architecture and interior decoration, such as kɯllukʌn ‘glue gun’ and tsollatʰon ‘zolatone’ were classified as cultural loanwords, since they don’t have any alternative native words. In contrast, some loanwords related to colors, including kʰʌllʌ ‘color’, hwaitʰɯ ‘white’, and tʰon ‘tone of color’ were classified as core loanwords used in parallel with substitutable alternative words sʰεk̚k̕al ‘color’, hayansʰεk̚ ‘white’ and sʰεk̚ts̕o ‘tone’.

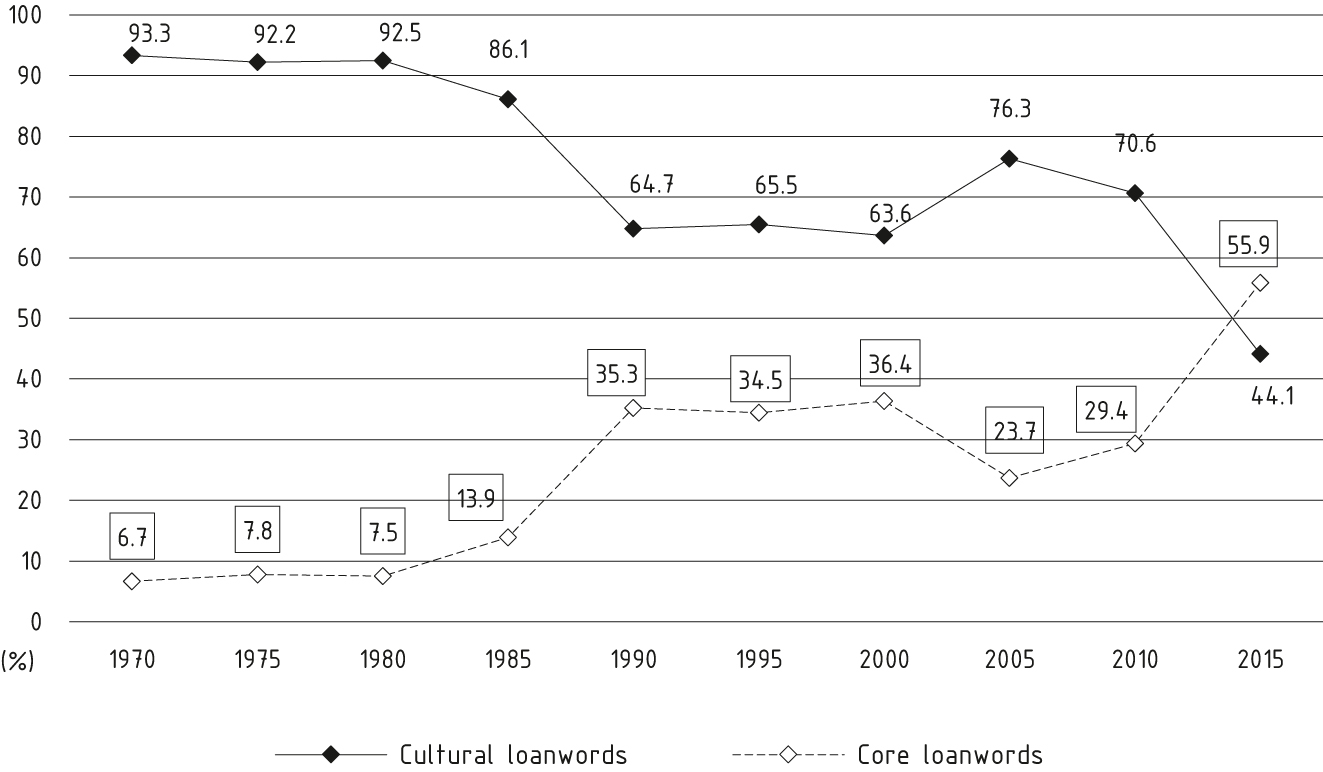

The comparative analysis of the loanwords in the corpus is presented in Figure 8. The numbers on the straight line represent the proportion (%) of cultural loanwords in relation to all the loanwords for each period, whereas those on the dotted line represent the proportion of core loanwords.

Cultural loanwords versus core loanwords in content words.

Cultural loanwords constitute a more significant proportion across periods, except in the most recent period – 2015. This result supports the general observation of vocabulary borrowing, by which the borrowing of core vocabulary is much rarer than that of cultural vocabulary (Haspelmath 2009: 36). However, a more detailed analysis based on the increasing and decreasing tendencies over time indicates that core loanwords began to increase remarkably, narrowing the gap between the cultural loanwords and the core loanwords from 1990, when the proportion of core loanwords increased from 13.9 % to 35.3 %, while the proportion of cultural loanwords decreased from 86.1 % to 64.7 %. This indicates a drastic change, considering that the proportion of cultural loanwords has been maintained at around 90 % and that core loanwords have remained at around 10 % until 1985. The growing tendency of core loanwords ultimately resulted in the reversal of core loanwords over cultural loanwords by about 11.8 % pts in the period 2015, even though it has subtle fluctuations.

Alternations between core loanwords and alternative native words carry significant social meaning (Blom and Gumperz 2000). The social context of loanword usage and change, as well as the sociolinguistic conditions of communication where the speaker and listener exist, are useful for explaining the “flexibility and dynamic nature” of borrowing (Winter-Froemel 2010). When considered in terms of social motives, the speech behavior of loanwords can be understood as a process indexing the speaker, granting justification to their identity, and further forming a membership centered on the relevant community (Zenner et al. 2015). If we admit that the public sentiment of wanting to be associated with the prestige of the donor language as a social motive for using loanwords has a strong hold (Cartier 2019), the significant increase in core loanwords can be understood as a phenomenon reflecting growing curiosity and admiration for foreign cultures as well as exotic tastes widely shared in Korean society during those periods.[8]

Preference for core loanwords to alternative native words in our corpus has been reinforced in conjunction with media characteristics of public magazines, which seek to provoke public interest and demand. Public magazines are among the representative mass media that introduce new cultures to readers and strive to become cultural icons leading public trends. In particular, the use of loanwords in diverse advertising arouses images such as stable social stereotypes connected to the language speakers (Hornikx et al. 2013 [cited in Zenner et al. 2019: 2]). The magazines reflect the interests and needs of the public as well as the social trends in magazine texts, encouraging readers to equate their identity with the objects or characters appearing in the magazine. In other words, the prevalence of admiration for foreign cultures and exotic tastes in Korean society is reflected in the increasing use of core loanwords in the magazine corpus.

From a diachronic perspective, the analysis of cultural loanwords and core loanwords confirmed once again that the 1990s were an important decade for lexical borrowing. Core loanwords started to show a remarkable increase from 1990, when the number tripled all of a sudden. Since then, the gap between cultural and core loanwords has remained narrow for over a decade. The sudden increase in core loanwords could be interpreted as an important signal, indicating a drastic inclination of Korean society toward foreign culture and language in this period, insomuch as core loanwords reflect the conscious choice of speakers considering the social meanings of loanword usage.

In the following section, we perform a semantic analysis of Period Representative Loanwords (PRL). Observing semantic values of highly ranked PRL for each period with examples, we will elucidate another important aspect of Korean loanword change over time.

5 Semantic analysis of Period Representative Loanword (PRL)

5.1 Definition of PRL

To obtain a more precise and detailed description of diachronic changes of Korean loanword usage, we sought to observe the loanwords that are more frequently used in a particular period than in others. To this end, we adopted the Kullback–Leibler divergence (KL divergence) (Kullback and Leibler 1951; Kullback 1968; Kim et al. 2013). The KL divergence measures the difference between one distribution and a reference distribution. In our case, the average probability distribution of a word appearing in each period is the reference distribution, to which we compare the probability distribution of the word appearing in a particular period. If the KL divergence is small, the word is not as frequent in the given period as in other periods. If it is significant, it indicates that the word is used more frequently in that period than in the others.

With q A (W)—the probability of a word W appearing in a certain period A—and r(W)—the average probability of the word appearing in all periods, KL divergence is defined as follows:

We calculated KL divergence for all the loanwords appearing in our corpus to list the most distinctive words for each period; this list includes words that are frequently used in one period as compared to others. Then, we selected the loanwords whose divergence value was over 0.0007 and referred to them as Period Representative Loanwords (PRL). We made a PRL list of 271 words in types and 15,456 words in tokens. Table 3 shows the number of PRLs in types and tokens for each period.

Number of types and tokens of period representative loanword (PRL).

| 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | 4 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 18 | 37 | 60 | 45 | 67 | 271 |

| Token | 98 | 225 | 206 | 735 | 1,155 | 1,027 | 2,230 | 4,128 | 2,533 | 3,119 | 15,456 |

Based on the PRL list, we analyzed semantic characteristics of each period. In this way, we again confirm the importance of the 1990s in terms of lexical borrowing.

5.2 PRL in 1970–1990: housing facilities and new residential lifestyle

In the list of PRL of these periods, we found many lexical items regarding construction materials and housing facilities as well as vocabulary on heating, air conditioning and energy use in households. With the rapid industrialization and urbanization of Korean society, many Koreans began to live in apartments with verandas, giving up individual homes or the traditional residences called hanok. They seem to have familiarized themselves with the new Western residential environment. Table 4 shows the highly ranked PRLs in each period below.

PRL in 1970–1990.

| 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pʌsʰɯ | pʰaipʰɯ | poillʌ | pildiŋ | apʰatʰɯ |

| bus | pipe | boiler | building | apartment | |

| 2 | tʰɛk̚ɕi | sʰɯkʰil | sʰɯtʰenresʰɯ | kasʰɯ | eʌkʰʌn |

| taxi | embroidery | stainless | gas | air conditioner | |

| 3 | kʰonkʰɯritʰɯ | kʰʌʌtʰɯn | enʌdzi | eʌkʰʌn | poillʌ |

| concrete | curtain | energy | air conditioner | boiler | |

| 4 | kʰentʰɯdzi | poillʌ | ɕ̕iŋkʰɯe | pʰʌ | kasʰɯboillʌ |

| kent paper | boiler | sink | fur | gas boiler | |

| 5 | hep̚pʌn | tʰɛŋkʰɯ | apʰatʰɯ | model | |

| Hepburn | tank | apartment | model | ||

| 6 | apʰatʰɯ | hotʰel | sʰɯpʰʌndzi | peranda | |

| apartment | hotel | sponge | veranda | ||

| 7 | alminyum | kasʰɯ | sʰɯpʰikʰʌ | ||

| aluminium | gas | speaker | |||

| 8 | ribiŋ | pʌsʰɯ | kʰapʰetʰɯ | ||

| living | bus | carpet | |||

| 9 | tʰɛŋkʰɯ | sʰɯwitsʰi | |||

| tank | switch | ||||

| 10 | sʰɯtʰeinresʰɯ | sʰɯpʰɯriŋ | |||

| stainless | spring | ||||

| 11 | pʰɯllasʰɯtʰik̚ | mɛtʰɯrisʰɯ | |||

| plastic | mattress | ||||

| 12 | tʰii | meikʰʌ | |||

| tee | brand | ||||

| 13 | pum | ||||

| boom | |||||

| 14 | pʰeintʰɯ | ||||

| paint |

Among the PRL of 1970 are pʌsʰɯ ‘bus’ and tʰɛk̚ɕi ‘taxi’. These public transportations are mentioned in the corpus, specifically appearing in the discussion on the convenience experienced by city dwellers who moved and settled in the new residential area of the suburbs to avoid housing shortages in the center of cities. The word kʰonkʰɯritʰɯ ‘concrete’ was presented as the main material for a variety of architectural and civil engineering works and often appeared in discussions on heating, insulation, or waterproofing.

| usʰʌn toro pʰogirado nʌlbʌdziɲik̕a pʌsʰɯ unhɛŋɕigaɲi tsoŋdzʌnbodado 5bun nɛdzi 7bunganɯn tantsʰuk̚t̕wen gʌt̚ kat̚t̕a. |

| ‘The interval between buses seems to have shortened by 5 to 7 minutes as the roads have been widened.’ |

| kʰonkʰɯritʰɯ pyʌgɯn (…) idzuŋbyʌgɯro hadzi anɯmyʌn kyʌllo t̕ɛmune |

| kompʰaŋiga sʰɛŋginda. |

| ‘Concrete walls should be doubled, otherwise they will get mold because of dew.’ |

In 1975, as in the previous period, many lexical items of construction materials were found such as alminyum ‘aluminum’, sʰɯtʰenresʰɯ ‘stainless’ and pʰɯllasʰɯtʰik̚ ‘plastic’. At the same time, the PRL in this period reveals the newly arrived modern lifestyles and the Western housing culture. For instance, apʰatʰɯ ‘apartment’ emerged out of the context of describing the structure or convenience of indoor spaces (example 3), whereas ribiŋ ‘living room’ was presented on its concept being explained by comparing it to the kitchen or dining room (example 4). Another PRL, poillʌ ‘boiler’ is used to characterize heating systems such as coal briquettes, electric heating, and oil boiler heating (example 5).

| hyʌndɛhwahan dzugʌsʰɛŋhware yaŋɕigin apʰatʰɯ sʰɛŋhwarɯl hanɯn |

| ɲip̚ts̕udzadɯrɯn t̕ɛt̕ɛro nok̚s̕ɛge pingonɯl tsadzu nɯk̕ige twenda. |

| ‘Dwellers of apartments, which are a modernized housing lifestyle, used to feel the lack of greenery.’ |

| ribiŋ kʰitʰiɲina taiɲiŋ ribiŋ (ɕik̚t̕aŋgwa kʌɕirɯl han kʰanɯro han paŋ)in |

| gyʌŋunɯn, (…) tɛdamhan kʰɯn muɲirɯl tʰɛkʰanda. |

| ‘Large patterns are selected for living kitchens or dining living (a room in which a dining room and a living room are combined into a compartment).’ |

| 20 pʰyʌŋ ihae tsibɯn yʌntʰan poillʌga yʌlhyoyul tsʰɯŋmyʌnesʰʌ yurihada. |

| ‘Briquette boilers are favorable for houses with floor areas of less than 20 pyong(about 66 square meters) in terms of thermal efficiency.’ |

In 1980, the word enʌdzi ‘energy’ was found during discussions on energy efficiency and tʰɛyaŋɲyʌl enʌdzi ‘solar energy’ as an alternative to coal or oil-based heating systems. The loanword tʰɛŋkʰɯe ‘tank’ emerged in the context of water tanks storing solar heat. In the same vein, ɕ̕iŋkʰɯe ‘sink’ was used in corpus with sʰɯtʰenresʰɯ ‘stainless’ as a semi-permanent and energy saving material, reflecting a contemporary interest in the home facilities.

| oilsʰyokʰɯ ihu, enʌdzi mundzega k(y)esʰok̚ uri sʰɛŋhwarɯl ʌdup̚k̕e nurɯgo |

| it̚t̕a. |

| ‘The energy problem has made our life continuously darker since the oil shock.’ |

| tsʰʌɯm multʰɛŋkʰɯe murɯn ɕibi to tsʌŋdoyʌs̕ɯna, (…) kot̚ ok̚s̕aŋesʰʌ |

| nɛryʌonɯn muls̕oriwa hamk̕e pʰaipʰɯga t̕ɯk̕ɯnt̕ɯk̕ɯnhɛdzʌt̚t̕a. |

| ‘At first, the temperature of the water tank was about 12 degrees but in a moment, the pipes became hot with the sound of water.’ |

In 1985, meikʰʌ ‘brand’ and pum ‘boom’ are noticeable. The word meikʰʌ ‘brand’ often appeared in conjunction with yumyʌŋ ‘famous’ or tɛ ‘great’. Loanwords regarding brand names are used to appeal to people’s desire to be associated with the social and economic prestige of the brand (Haspelmath 2009; Tranter 1997). Another PRL, pum ‘boom’ was often used in compound words related to the construction business or investment in real estate (kʌntsʰuk̚p̕um ‘boom of construction’ and pildiŋ ɕintsʰuk̚p̕um ‘boom of newly constructed buildings’; pudoŋsʰan tʰudzabum ‘boom of investment in real estate’ and tʰugibum ‘boom of speculation’).

| yumyʌŋ meikʰʌe tsʰimdɛrɯl kuipʰɛs̕ʌdo sʰayoŋ t̕ɛe kwaʎʎi budzogɯro |

| sʰumyʌŋi tantsʰuk̚t̕wenɯn gyʌŋudo sʰɛŋginɯn sʰudo it̚t̕a. |

| ‘Even if you buy a bed from a famous brand, it may not last for a long time due to insufficient care.’ |

| ribatʰɯ, kɯlloria, porɯneo tɯŋ tɛmeikʰʌe kagu kap̚s̕ɯn pisʰɯtʰan |

| sʰudzunɯl irugo it̚t̕a. |

| ‘Furniture form great brands such as Livart, Gloria, Borneo, etc. are similarly priced.’ |

The PRL model ‘model’ and beranda ‘veranda’ are among the PRL of the period 1990, in addition to apʰatʰɯ ‘apartment’. The word model ‘model’ is found in the compound word model hausʰɯ ‘model house’; it is also used to signify ‘samples’ of industrial products. The PRL beranda ‘veranda’, an indoor space of apartments draws a particular attention in this period. Verandas were considered private indoor gardens decorated by dwellers, which reflected their individual tastes. This phenomenon implies that people began to pursue values higher than those of convenience or energy saving in their residences.

| ol dzʌnbangie ʌmtsʰʌŋnan daŋtsʰʌm gyʌŋdzɛŋɲyurɯl poin pundaŋ |

| apʰatʰɯe model hausʰɯ. |

| ‘Model house for Bundang area apartments with an enormous bid to hit rate in the first half of this year.’ |

| ɕillɛro k̕ɯrʌdɯrin beranda tsʌŋwʌn. |

| ‘Veranda garden moved to the indoor space.’ |

Most PRLs of the periods from 1970 to 1990 are intensively associated with the alteration of residential lifestyles and housing facilities, such as apʰatʰɯ ‘apartment’, poillʌ ‘boiler’, ribiŋ ‘living room’, and beranda ‘veranda’, which did not previously exist in Korean traditional houses and were introduced from the Western residential culture. Many other PRLs are concerned with construction materials such as kʰonkʰɯritʰɯ ‘concrete’ as well as heating and air-conditioning facilityes.

5.3 PRL in 1995–2015: various tastes and aesthetic value

Observing the PRL from 1995 to 2015, we encountered a drastic discontinuity with those from the previous periods. In the PRL list of these periods, tidzain ‘design’, intʰeriʌ ‘interior’, kʰʌllʌ ‘color’ and sʰɯtʰail ‘style’ were prevalent, whereas the most representative PRLs of the periods 1970–1990, apʰatʰɯ ‘apartment’ and construction material names like kʰonkʰɯritʰɯ ‘concrete’ were absent. We also found loanblend verbs such as romɛntʰikʰada ‘be romantic’, mɛtsʰihada ‘to match’ and sʰetʰiŋhada ‘to set’, none of which were included in the PRL list of the previous periods. As mentioned above (cf. Section 2), verbal loanwords result from a selective verbalization process inherent to the recipient language; therefore, they are generally used less frequently than nouns. Table 5 presents the PRL for the periods 1995–2015.

PRL in 1995–2015.

| 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | kʰʌtʰɯn | sʰopʰa | kʰʌllʌ | kʰʌllʌ | tidzain |

| curtain | sofa | color | color | design | |

| 2 | pʰeintʰiŋ | t’eibŭl | hwaitʰɯ | pʰɛtʰʌn | kʰʌllʌ |

| painting | table | white | pattern | color | |

| 3 | ɛk̚sʰesʰʌri | kʰʌtʰɯn | ɛntʰikɯ | kɛllʌri | intʰeriʌ |

| accessary | curtain | antique | gallery | interior | |

| 4 | kʰʌbʌ | pʰɛbɯrik̚ | sʰɯtʰail | kʰapʰe | pʰɛtʰʌn |

| cover | fabric | style | cafe | pattern | |

| 5 | emdekʰo | ɛntʰik̚ | tʰail | tidzain | sʰɯtʰɛmpʰɯ |

| Mdeco | antique | tile | design | stamp | |

| 6 | sʰ(y)epʰɯrain | pʰom | modʌn | sʰɯtʰail | tidzainʌ |

| Chefline | foam | modern | style | designer | |

| 7 | tsʰekʰɯ | kʰʌbʌriŋ | kʰɯrisʰɯmasʰɯ | pʰointʰɯ | pɯrɛndɯ |

| check | covering | Christmas | point | brand | |

| 8 | ribon | tidzain | palkʰoɲi | rum | sʰɯtʰail |

| ribbon | design | balcony | room | style | |

| 9 | sʰopʰa | aidiʌ | tidzain | sʰaidzɯ | hausʰɯ |

| sofa | idea | design | size | house | |

| 10 | kʰonʌ | intʰeriʌ | pʰɛbɯrik̚ | mɛtsʰihada | mai |

| corner | interior | fabric | match | my | |

| 11 | rʌgɯ | kʰʌmpʰyutʰʌ | pʰointʰɯ | hwaitʰɯ | pintʰidzi |

| lug | computer | point | white | vintage | |

| 12 | mɛtsʰi | kʰusʰyʌn | intʰeriʌ | sʰetʰiŋhada | sʰ(y)eʌ |

| match | cushion | interior | set | share (house) | |

| 13 | ɕitʰɯ | rʌndʌn | romɛntʰikʰada | ɕimpʰɯl | pʰɛbɯrik̚ |

| sheet | London | be romantic | simple | fabric | |

| 14 | sʰɯweden | tsʰeri | ɛntʰik̚ | ɕiɲiʌ | tʰeibɯl |

| Sweden | cherry | antique | senior | table |

In the period 1995, lexical items regarding interior decoration, such as kʰʌtʰɯn ‘curtain’, sʰopʰa ‘sofa’, rʌgɯ ‘rug’, ɕitʰɯ ‘sheet’ as well as intʰeriʌ ‘interior’ and pʰeintʰiŋ ‘painting’ were included in the PRL list. For the first time, a country name, sʰɯweden ‘Sweden’ and brand names such as emdekʰo ‘Mdeco’ and sʰ(y)epʰɯrain ‘Chefline’ were found in the list. The word sʰɯweden ‘Sweden’ appeared in an article introducing the official residence of the Swedish ambassador in Seoul, which was rebuilt at the time. Brand names appeared in the captions presented with pictures in articles, together with the price information of the products.

The interest in interior decoration continues in 2000, as vocabulary referring to furniture and items such as tʰeibɯl ‘table’, kʰʌtʰɯn ‘curtain’, and pʰɛbɯrik̚ ‘fabric’ are moved to the top of the PRL list, together with the words describing interior design methods such as kʰʌbʌriŋ ‘covering’, tidzain ‘design’ and pʰointʰɯ ‘point’. In this period, words expressing a specific style such as ɛntʰik̚ ‘antique’ and those related to colors, including tsʰeri ‘cherry’ appeared in the PRL list for the first time.

In 2005, we encountered the loanblend predicate romɛntʰikʰada ‘be romantic’ for the first time in the PRL list. Once again, verbs and adjectives are not borrowed as much as common nouns between languages; however, during this period, loanblend verbs and adjectives began to appear in the PRL list. Two more loanblend verbs were presented in 2010, including mɛtsʰihada ‘match’ and sʰetʰiŋhada ‘set’. Another characteristic of 2010 is the interest in various spaces other than the home. kɛllʌri ‘gallery’ and kʰapʰe ‘café’ are ranked as the third and the fourth PRL on the list. These words are used in conjunction with the suffix -kat̚t̕a ‘be similar to’, the postpositional particle tsʰʌrʌm, meaning of the preposition ‘like’, and with the nouns sʰɯtʰail ‘style’ or kʰonsʰep̚tʰɯ ‘concept’.

In 2015, with a total of 67 of the most distinctive PRLs, many brand names were included in the list. Brand names were first presented in little picture captions in 1995, but they were used more in the text of promotional articles in 2015.

| ʌriɲi ɕisʰʌnesʰʌ mandɯrʌdzinɯn ɲikʰeae kagudɯl. |

| ‘furniture of IKEA made from the viewpoint of children’ |

| ribatʰɯ tsʰinhwangyʌŋ gamsʰʌŋ ai baŋ kʰɛmpʰein. |

| ‘Livart’s campaign for children’s rooms with environment-friendly sensibility.’ |

Another major characteristic found from the PRL list in 2015 was that the interest in residence was different from the existing types of dwelling. The words sʰ(y)eʌhausʰɯ ‘share house’ and sʰosʰ(y)ʌlhaudziŋ ‘social housing’ particularly emerged in the PRL list; they mostly appeared in the context of explaining what they are and introducing well-known cases in foreign countries.

The PRLs of the periods 1995–2015 are so homogeneous that several words are repeatedly presented; tidzain ‘design’, intʰeriʌ ‘interior’, kʰʌllʌ ‘color’, sʰɯtʰail ‘style’, pʰointʰɯ ‘point’, hwaitʰɯ ‘white’, pʰɛtʰʌn ‘pattern’ and pʰɛbɯrik̚ ‘fabric’ appear at least three times in the PRL list of these periods. Almost all the PRLs in these periods seem to be related to the aesthetic value and individual taste of space.

Another remarkable property of the PRLs of these periods is diversity. We found various names of furniture and interior accessories between 1995 and 2015: sʰopʰa ‘sofa’, rʌgɯ ‘rug’, ɕitʰɯ ‘sheet’, tʰeibɯl ‘table’, kʰusʰyʌn ‘cushion’, kʰʌbʌ ‘cover’ as well as kʰʌtʰɯn ‘curtain’. An interest in various types of space was also revealed in terms of PRL such as kɛllʌri ‘gallery’ and kʰapʰe ‘café’. Moreover, the interest in new lifestyles concerning the types of dwelling such as kesʰɯtʰɯ hausʰɯ ‘guest house’ and sʰ(y)eʌ ‘share house’ was initiated as mentioned above.

The last but the most significant characteristic of these periods is emergence of loanblend predicates as PRL: romɛntʰikʰada ‘be romantic’, mɛtsʰihada ‘match’ and sʰetʰiŋhada ‘set’.

6 Conclusions

In addition to the gradual and rapid increase in the usage of loanwords over time, our analysis of corpus data revealed that Korean loanword usage has undergone significant alterations, particularly in the 1990s.

First, there was a dramatic increase of loanwords, both in terms of type and token.

Second, the attitude of Korean speakers toward loanword usage changed remarkably in these periods; they began to choose core loanwords instead of alternative native Korean words along with verbal loanblends suffixed with -hada ‘do’ or -tweda ‘become’.

The loanwords from 1970 to 1990, and those from 1995 to 2015 are semantically distinct; loanwords designating construction materials and housing facilities were mostly used in the former period, whereas those reflecting the aesthetic value and individual taste of interior design were predominant in the latter period.

If social contact brings about changes in lexical items, the alteration of Korean lexical borrowing observed in public magazine articles, particularly in the 1990s, could be explained by the impacts of certain social phenomena. For example, having experienced international mega-events, such as the Asian Games in 1986 and the Olympic Games in 1988, both hosted in Seoul, the Korean government eliminated its control over the quota of travelers overseas in 1989, and overseas trips by Korean citizens increased explosively (Bridges 2008). At the same time, foreign language education in Korean public schools was strengthened in the 1990s. From this period, all Korean elementary school students had to learn English compulsorily, whereas foreign languages were required only for middle and high school students before (Hong 2012; Joo 2010). In addition, special high schools called “Foreign Language High Schools” were founded or legitimized to cultivate leaders with proficiency in speaking various foreign languages (Kim and Kim 2015; Kwon et al. 2006). In commercial context, international messaging media, including public magazines such as Newsweek, Vogue, and Elle, began to issue local versions in Korean in the 1990s (Cheon 2014).

Our investigation of lexical borrowing contributes to understanding the incidence of social contact in the Korean language from a diachronic perspective. The comparative analysis based on the notion of cultural/core loanwords was found to be effective in elucidating the evolution of Korean speakers’ attitudes toward foreign languages and cultures. The KL divergence and PRL analysis allowed us to characterize each period in relation to loanword usage. These corpus-based methodologies are expected to prove helpful in diachronic or comparative research exploring further language contact.

Abbreviations

- KCRCC

-

Korean Contemporary Residential Culture Corpus

- KL Divergence

-

Kullback–Leibler Divergence

- PRL

-

Period Representative Loanword

- POS

-

Part of Speech

- STTR

-

Standardized Type-Token Ratio

- TTR

-

Type-Token Ratio

Funding source: Yonsei University

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Yonsei University Research Grant of 2021.

References

Ahn, Heedon. 1991. Light verbs, VP-movement, negation and clausal architecture in Korean and English. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Harald. 2001. Word frequency distributions. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.10.1007/978-94-010-0844-0Search in Google Scholar

Blom, Jan-Petter & John Gumperz. 2000. Social meaning in linguistic structure: Code-switching in Norway. In Wei Li (ed.), The bilingualism reader, 111–136. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Bridges, Brian. 2008. The Seoul Olympics: Economic miracle meets the world. The International Journal of the History of Sport 25(14). 1939–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360802438983.Search in Google Scholar

Calvet, Louis-Jean. 1998. Language wars and linguistic politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198235989.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Calvet, Louis-Jean. 1999. Pour une écologie des langues du monde. Paris: Plon.Search in Google Scholar

Cartier, Emmanuel. 2019. Emprunts en Français Contemporain : Etude Linguistique et Statistique à Partir de la Plateforme Néoveille. In Alicja Kacprzak, Radka Mudrochova & Jean-François Sablayrolles (eds.), L’emprunts en question(s), 145–185. Limoges: Lambert-Lucas.Search in Google Scholar

Cheon, Junghwan. 2014. Words of the times and sentences of desire. Seoul: Maeumsanchaek.Search in Google Scholar

Cho, Namho. 2014. Acceptance of and response to loanwords in the Korean language. The Journal of Humanities 39. 13–38.Search in Google Scholar

Chrystal, David. 2000. Language death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Donohue, Mark & Søren Wichmann. 2008. The typology of semantic alignment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199238385.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Grimshaw, Jane & Armin Mester. 1988. Light verb and θ-making. Linguistic Inquiry 19(3). 205–232.Search in Google Scholar

Hagège, Claude. 2000. Halte à la mort des langues. Paris: Edition Odile Jacob.10.3917/puf.hageg.2001.01Search in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2008. Loanword typology: Steps toward a systematic cross-linguistic study of lexical borrowability. In Thomas Stolz, Dik Bakker & Rosa Salas Palomo (eds.), Aspects of language contact: New theoretical, methodological and empirical findings with special focus on romanization processes, 43–62. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110206043.43Search in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2009. Lexical borrowing: Concepts and issues. In Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor (eds.), Loanwords in the world’s languages: A comparative handbook, 33–54. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110218442.35Search in Google Scholar

Haugen, Einar. 1950. The analysis of linguistic borrowing. Language 26. 210–331. https://doi.org/10.2307/410058.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, Chansook. 2012. Compress individualization and ‘gender’ category in 1990s Korea. Women and History 17. 1–25.10.22511/women..17.201212.1Search in Google Scholar

Hornikx, Jos, Frank van Meurs & Robert-Jan Hof. 2013. The effectiveness of foreign-language display in advertising for congruent versus incongruent products. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 25(3). 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2013.780451.Search in Google Scholar

Joo, Eunwoo. 2010. A decade of freedom and consumption, and the onset of cynicism: The Republic of Korea, its conditions of everyday life in the 1990s. Society and History 88. 307–344.Search in Google Scholar

Jun, Jaeyeon. 2014. A study on the classification of Korean words borrowed from French and their usage. French Studies 67. 153–197.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, Beomil. 2021. A quantitative study of language change in the Korean Newspaper: Focusing on Chosun Ilbo Articles from 1920 to 2015. Seoul: Yonsei University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Hasoo, Hyunjung Son, Jaeyun Lee & Beomil Kang. 2013. A quantitative approach to the relation between politics and language. Discourse and Cognition 20(1). 79–111. https://doi.org/10.15718/discog.2013.20.1.79.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Seongyul & Hoonho Kim. 2015. Diversification of high school system in Korea-changes, performances and challenges. Educational Research and Practice 81. 27–56.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Yongha. 1995. Verbal nouns, double object and the verb ‘ha-’. Korean Journal of Linguistics 20(4). 45–70.Search in Google Scholar

Koplenig, Alexander, Sascha Wolfer & Carolin Müller-Spitzer. 2019. Studying lexical dynamics and language change via generalized entropies: The problem of sample size. Entropy 21(5). 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21050464.Search in Google Scholar

Kullback, Solomon. 1968. Information theory and statistics. New York: Dover Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Kullback, Solomon & Richard A. Leibler. 1951. On information and sufficiency. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 22. 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729694.Search in Google Scholar

Kwon, Oryang, Kyungsoon Boo, Dongil Shin, Jinkyoung Lee & Seokboon Hyoun. 2006. A consideration on how to activate English language education for elementary and middle school students through the evaluation for 10 years’ outcome. Seoul: Ministry of Education & Human Resources Development.Search in Google Scholar

Moravcsik, Edith. 1975. Verb borrowing. Vienna Linguistic Gazette 8. 3–30.Search in Google Scholar

Moravcsik, Edith. 1978. Universals of language contact. In Joseph Greenberg & Edith Moravcsik (eds.), Universals of human language, vol. 1, method and theory, 93–122. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Mudrochova, Radka. 2020. La Francisation des Emprunts à L’anglais D’après L’orthographe Rectifiée: Son Application en Français de France et en Français Québécois. Cahiers de praxématique 74. https://doi.org/10.4000/praxematique.6367.Search in Google Scholar

Muysken, Pieter. 1981. Half-way between Spanish and Quechua: The case for relexification. In Arnold Highfield & Valdman Albert (eds.), Historicity and change in creole studies, 52–78. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Myers-Scotton, Carol. 2002. Contact linguistics: Bilingual encounters and grammatical outcomes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198299530.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Oh, Yoonjung. 2017. A study on Korean residential culture in the Corpus of Women’s Magazine. Seoul: Ewha Womans University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Oh, Yoonjung. 2020a. Lexical changes in the Korean residential culture corpus: Focused on semantic classification of nouns. Language and Information 24(3). 27–45. https://doi.org/10.29403/li.24.3.2.Search in Google Scholar

Oh, Yoonjung. 2020b. Contemporary Korean residential sensibility represented in the corpus. The Korean Cultural Studies 39. 173–209.Search in Google Scholar

Poplack, Shana. 2018. Borrowing: Loanwords in the speech community and in the grammar. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780190256388.003.0004Search in Google Scholar

Poplack, Shana & Nathalie Dion. 2012. Myths and facts about loanword development. Language Variation and Change 24. 279–315. https://doi.org/10.1017/s095439451200018x.Search in Google Scholar

Richards, Brian. 1987. Type/token rations: What do they really tell us? Journal of Child Language 14(2). 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000900012885.Search in Google Scholar

Rüdiger, Sofia. 2018. Mixed feelings: Attitudes towards English loanwords and their use in South Korea. Open Linguistics 4. 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0010.Search in Google Scholar

Sablayrolles, Jean-Francois. 2019. Les Emprunts Face aux Xénismes, Pénégrinismes, Internationalismes, Statalismes. In AlicjaKacprzak, Radka Mudrochova & Jean-Francois Sablayrolles (eds.), Emprunts en question(s). Limoges: Lambert-Lucas.Search in Google Scholar

Suh, Jungsoo. 1975. Research on the grammar of verb ‘ha-’. Seoul: Hyungseul Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Tadmor, Uri. 2009. Loanwords in the world’s languages: Findings and results. In Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor (eds.), Loanwords in the world’s languages: A comparative handbook, 55–75. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110218442.55Search in Google Scholar

Thomason, Sarah Grey & Terrence Kaufman. 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.10.1525/9780520912793Search in Google Scholar

Tranter, Nicolas. 1997. Hybrid anglo-Japanese loans in Korean. Linguistics 35. 133–166. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1997.35.1.133.Search in Google Scholar

Tweedie, Fiona J. & Harald Baayen. 1998. How variable may a constant be? Measures of lexical richness in perspective. Computers and the Humanities 32(5). 323–352. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1001749303137.10.1023/A:1001749303137Search in Google Scholar

Vinet, Marie-Thérèse. 1996. Lexique, Emprunts et Invariants: Une Analyse Théorique des Anglicismes en Français du Québec. Revue Québécoise de linguistique 24(2). 165–181. https://doi.org/10.7202/603119ar.Search in Google Scholar

Whitney, William Dwight. 1881. On mixture in language. Transactions of the American Philological Association (1869–1896) 12. 1–26.10.2307/2935667Search in Google Scholar

Winford, Donald. 2010. Contact and borrowing. In Raymond Hickey (ed.), The handbook of language contact, 170–187. Malden, MA & Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781444318159.ch8Search in Google Scholar

Winter-Froemel, Esme. 2010. Les People, les Pipoles, les Pipeuls: Variance in Loanword Integration. PhiN: Philologie im Netz 53. 62–92.Search in Google Scholar

Zenner, Eline, Drik Speelman & Drik Geeraerts. 2015. A sociolinguistic analysis of borrowing in weak contact situations: English loanwords and phrases in expressive utterances in a Dutch reality TV show. International Journal of Biling 19. 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006914521699.Search in Google Scholar

Zenner, Eline, Laura Rosseel & Andreea S. Calude. 2019. The social meaning potential of loanwords: Empirical explorations of lexical borrowing as expression of (social) identity. Ampersand 6. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2019.100055.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Evaluation of keyness metrics: performance and reliability

- Let my speakers talk: metalinguistic activity can indicate semantic change

- The blurring of the boundaries: changes in verb/noun heterosemy in Recent English

- The linguistic organization of grammatical text complexity: comparing the empirical adequacy of theory-based models

- Present perfect and preterit variation in the Spanish of Lima and Mexico city: findings from a corpus analysis

- Lexical borrowing in Korean: a diachronic approach based on a corpus analysis

- Truth be told: a corpus-based study of the cross-linguistic colexification of representational and (inter)subjective meanings

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Evaluation of keyness metrics: performance and reliability

- Let my speakers talk: metalinguistic activity can indicate semantic change

- The blurring of the boundaries: changes in verb/noun heterosemy in Recent English

- The linguistic organization of grammatical text complexity: comparing the empirical adequacy of theory-based models

- Present perfect and preterit variation in the Spanish of Lima and Mexico city: findings from a corpus analysis

- Lexical borrowing in Korean: a diachronic approach based on a corpus analysis

- Truth be told: a corpus-based study of the cross-linguistic colexification of representational and (inter)subjective meanings