Abstract

The study aims to explore the digital literacy (DL) of EFL teachers at Vietnamese universities using both a questionnaire and in-depth interviews. Teachers’ DL is a critical issue in the digitalization of education systems worldwide, including in Vietnam, as technology integration in education is only effective when teachers are digitally competent. In this regard, DL is one of the key factors influencing technology adoption and driving innovation within educational institutions. The questionnaire was used to evaluate teachers’ DL and was proven to be reliable and valid for use in the current study, demonstrating construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis. The findings indicate that the majority of EFL teachers exhibited good levels of DL. Although teachers’ competence in assessment was the highest, their competence in digital self-learning and updating was the lowest. Qualitative data from the in-depth interviews partially support the quantitative findings by reinforcing the questionnaire results and enabling a more comprehensive understanding of teachers’ DL within their teaching context. Regarding gender differences in DL levels, male teachers demonstrated higher digital literacy than female teachers, although the difference was not statistically significant.

1 Introduction

Since the 1980s, great effort was exerted to officially integrate computers and digital devices into educational institutions. In recent years, digital technologies have become an essential component of schools at all levels, especially in higher education, supported by government investment and initiatives from Ministries of Education and Training (MOET) worldwide and driven by innovation and technological development. Recognizing the impact of ICT on education in general, and on language teaching and learning in particular, the Vietnamese MOET has launched a series of policies promoting the application of ICT in education across all subjects, with a particular emphasis on English as a foreign language (EFL). These policies aim to establish clear directions for ICT development in education, as various stakeholders believe that integrating technology into education can lead to significant improvements in teaching and learning methods, as well as in education management. Furthermore, it can enhance the quality of education, develop a more skilled workforce, and promote national development.

According to a report on the status of ICT integration into education in Southeast Asian countries in 2010, Vietnam is in the third stage of the four-stage model of the UNESCO ICT development in education (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization [SEAMEO] 2010), which includes emerging (becoming aware of ICT), applying (learning how to use ICT), infusing (understanding how and when to use ICT), and transforming (specializing in the use of ICT). However, the result from OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (OECD 2018) depicts that only 43 % of Vietnamese teachers who participated in the survey “frequently” provide opportunities for students to apply ICT to the learning process, while 53 % is the average percentage of other countries in the group. Additionally, 97 % of teachers in the survey reported that ICT use for teaching has been included in formal education or training, while 80 % of teachers on average felt well-prepared for the use of ICT for teaching after finishing their studies. Furthermore, the survey reported that 93 % of teachers on average participated in professional development activities including the use of ICT for teaching in the 12 months prior to the survey; thus, a large need (55 %) exists for training in the use of ICT for teaching compared with 18 % across the OECD. In other words, teachers’ digital literacy (DL) is becoming a major issue as digitalization rapidly expands in the Vietnamese education system, because technology integration is only effective when teachers are digitally competent. Despite the significance of DL, an updated image of the DL of teachers at universities in the Vietnamese context, especially EFL teachers, is lacking, while DL is one of key factors that determines technology adoption and educational institution innovation.

In the field of EFL teaching and learning, recent studies indicate that DL can support teachers in achieving their pedagogical goals and assist language learners in improving their language skills, as well as in broadening and deepening their vocabulary (e.g., Golonka et al. 2014). Basically, technology that supports EFL teachers in planning lessons, communicating with colleagues and students, searching for information, producing word texts, and presenting lectures, among others, is becoming popular (e.g., Blin and Munro 2008). To date, EFL teachers and learners have been able to receive substantial support through the integration of digital technologies specifically designed for language teaching and learning. Furthermore, educators are considered role models for students; hence, if teachers are fully equipped with DL, they will be capable of providing guidance, demonstrating their knowledge and skills, and helping students apply technology to learning in both creative and critical ways. To address these needs, the present study aims to fill the research gap by exploring the DL of EFL teachers at Vietnamese universities using both quantitative and qualitative data. In addition, the study identifies several potential factors that may influence their DL. The findings of the present study may contribute to the development of technology integration in EFL teaching and learning in the Vietnamese context in particular, and in language education more generally.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Digital literacy definitions and frameworks in educational context

The term DL, which was first used by Gilster (1997), is conceptualized in multiple ways at the macro and micro levels. The conceptualization of DL at the high-stake level typically covers the role of citizenship (Røkenes and Krumsvik 2016). For example, Martin and Madigan (2006) propose that DL is the ability of addressing digital infrastructure and devices that empower the digital age. At the micro level, DL is frequently defined in specific contexts. For instance, in the school context, DL is understood as the knowledge, skill, and attitude of educators toward the use of digital media in teaching to facilitate the achievement of learning goals among learners and to equip them with essential knowledge and skills for future professions.

Different frameworks and models were developed to provide guidelines for school stakeholders in developing the DL of teachers as well as help educators assess their DL at the international level (e.g., Redecker and Yves 2017), national level (Education & Training Foundation 2019), or at the research-based level (e.g., Krumsvik 2014). Although a variety of frameworks and models exist, their components can be re-categorized into sub-scales according to the DigCompEdu framework (Redecker and Yves 2017), which includes five major components, namely, professional engagement, digital resource, teaching and learning, assessment, empowerment of learners, and facilitation of the digital competence of learners. In the Vietnamese educational system, multiple policies have been issued to support school stakeholders – especially teachers and students – in applying technology to teaching and learning. However, they have not proposed the DL framework for teachers but used other international DL frameworks to measure the DL of teachers (e.g., UNESCO 2013a, 2013b; Redecker 2017). Therefore, the current study used the components of DigCompEdu (Redecker and Yves 2017) to scaffold the assessment of teachers in the Vietnamese context, because the factors of this framework cover the core DL that teachers should achieve. Additionally, digital self-updating and self-learning will be considered as additional components alongside the five aforementioned ones, as technology evolves rapidly in the digital environment. Therefore, both teachers and students need to be competent in self-directed learning and in continuously updating their DL. As a result, this component was included in the digital literacy framework proposed for Vietnamese students by Do et al. (2021).

2.2 Instruments for measuring teacher digital literacy

Drawing on DL frameworks, scholars (e.g., Wang and Lu 2021; Siddiq et al. 2016) have developed instruments to measure teacher DL using two common approaches: pragmatic and psychometric. Based on the type of collected data, an instrument can be categorized under objective or subjective evaluation. In the literature, many studies used subjective assessment (e.g., Çebi and Reisoğlu 2022), whereas others used objective assessment (e.g., Wang and Lu 2021). The subjective instrument was designed based on teachers’ digital self-efficacy and can indirectly measure their DL. It is about teachers’ perceived confidence about their skills in using technologies to support their teaching and professional development (Yang and Cheng 2009). In using subjective assessments to measure DL among teachers, some researchers have criticized that the results may lack reliability and validity due to the low correlation between self-efficacy in DL and actual performance (Hatlevik et al. 2018). In addition, there is a possibility that teachers may overestimate their DL because they believe that they could complete the tasks; however, in real-life situations, there are many problems that they have to deal with while integrating technologies in their teaching, assessing students, and using digital platforms for their professional development tasks. The self-efficacy DL instruments are normally designed as Likert scale questionnaires or multiple-choice questionnaires on which teachers could rate their skills or knowledge (e.g., Do and Nguyen 2025). Another approach to assessing teachers’ DL is through objective measures such as tests, observations, and interviews. An objective instrument is also not a perfect one, because the result may be influenced by the technical ability of an assessment tool (Chanta-Jiménez 2021), or the assessment criteria, or the perceptions, experiences, knowledge, and skills of the evaluators. Therefore, researchers need to consider several factors when developing a DL measurement tool, as technology is constantly evolving. Thus far, few studies have combined objective and subjective assessments to measure teachers’ DL, even though this approach is recommended for a more comprehensive evaluation. The current study aims to explore the DL of EFL teachers in the Vietnamese educational context on the basis of the six components of DigCompEdu (Redecker and Yves 2017) and one additional component, namely, digital self-learning and updating, which were proposed by the UNESCO (2013a, 2013b). In addition, the study adopts the DigCompEdu Check-In tool for academics (Inamorato dos Santos 2019) to evaluate the DL of EFL teachers. Furthermore, in-depth interviews are conducted to gain a deeper understanding of their DL.

3 Methodology

The study employed a cross-sectional design to evaluate the DL levels of EFL teachers at Vietnamese universities. The research was conducted in two stages. First, participants completed a questionnaire, followed by in-depth interviews with selected individuals to supplement and enrich the questionnaire data.

3.1 Research questions

The study aims to seek answers to the following research questions:

RQ1. Is the questionnaire reliable and valid for assessing the DL of EFL teachers?

RQ2. What is the status quo of the DL of EFL teachers based on quantitative data?

RQ3. What is the extent of the digital literacy of EFL teachers based on qualitative data?

3.2 Sample of the study

The study recruited a total of 205 EFL teachers from various public and private universities across different regions of Vietnam. The participants represented a diverse sample in terms of gender, age, years of teaching experience, academic qualifications, and institutional affiliations. Participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to data collection. Table 1 presents the detailed demographic characteristics of the sample, including distributions by gender, teaching experience, academic rank, and region.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| Gender | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 70 | 135 | |||

| % | 34.1 | 65.9 % | |||

| Age range | <25 | 25–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | |

| N | 14 | 50 | 117 | 24 | |

| % | 6.8 | 24.4 | 57.1 | 11.7 | |

| Year of teaching with technology experience | 1–5 years | 6–10 years | 11–15 years | 16–20 years | >20 years |

| N | 30 | 65 | 98 | 12 | 0 |

| % | 14.6 | 31.7 | 47.8 | 5.8 | 0 |

3.3 Instrument

The questionnaire was adapted from the DigCompEdu CheckIn Tool for Academics (Inamorato Dos Santos 2019) which comprises 22 competencies organized under six categories. The questionnaire includes 25 items with seven components, namely, professional development, digital resources, teaching and learning, assessment, empowerment of learners, facilitation of the digital competence of learners, and digital self-learning and updating. The original questionnaire was designed to evaluate the DL of teachers in higher education; however, all items of the questionnaire were narrowed down in terms of scope to match that of EFL teachers. The first part aims to explore the demographic information of the teachers (e.g., gender, age, years of experience, and school digital development). The second part focuses on exploring the DL of teachers by requesting them to respond to questions with multiple choices that describe the level of DL. Based on the responses of the participants, the study evaluated their level of DL using six levels of skills, namely, A1 (newcomer), A2 (explorer), B1 (integrator), B2 (expert), C1 (leader), and C2 (pioneer). The questionnaire was translated into Vietnamese, and a few language teachers and researchers verified the content and language prior to its dissemination to teachers via Google forms. The study was carried out between September 2023 and January 2024. During this period, data were collected through a two-stage process. First, a questionnaire designed using Google Forms was distributed to teachers. This was followed by in-depth interviews conducted online via Zoom to objectively evaluate teachers’ digital literacy and to strengthen and validate the questionnaire responses.

4 Data analysis and results

4.1 RQ1. Is the questionnaire reliable and valid for assessing the DL of EFL teachers?

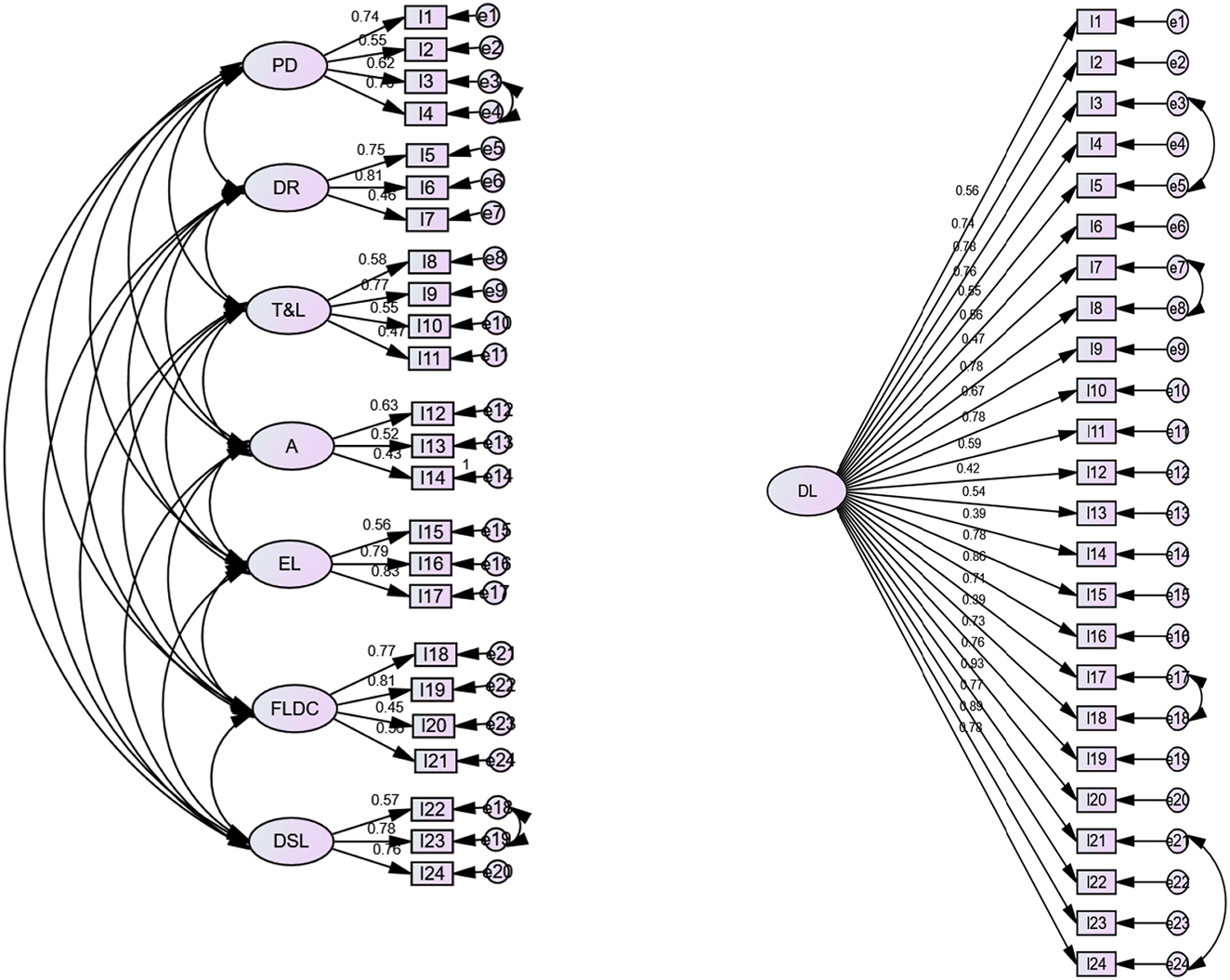

The study employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the model fit using IBM SPSS AMOS 22. Two models were tested: a one-dimensional and a seven-dimensional model. One item was omitted due to its low factor loading.

For the one-dimensional model, the CFA results did not indicate a good model fit (CFI = 0.88, TLI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.07). After modifying the model by correlating four pairs of error terms, the results showed an acceptable fit (CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06). Regarding the seven-factor model, the initial results met the cut-off criteria for acceptable fit (CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.07). The model was subsequently revised by correlating two pairs of error terms, after which the fit indices improved (CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06). Overall, the CFA results indicated that the seven-dimensional model fitted the data better than the one-dimensional model; however, both models achieved acceptable fit after modification (Figure 1).

One- and seven-dimensional models.

Additionally, Rasch analysis was conducted to examine the validity of the 25 items. The results indicated that the item and person fit statistics were acceptable for all items, with values ranging from 0.61 to 1.23. This suggests that the items functioned appropriately at the item level. Reliability reached Cronbach’s α = 0.87, indicating good internal consistency (Hair et al. 2006).

4.2 RQ2. What is the status quo of the DL teachers based on quantitative data?

Data were analyzed using SPSS, and the descriptive statistics indicated that the majority of teachers (40 %) were at the B2 (expert) level, 35.6 % were at the B1 (integrator) level, and 19.5 % were at the C1 (leader) level. Only a few teachers reported low proficiency at A2 (1.5 %) or high proficiency at C2 (pioneer; 3.4 %) (see Figure 2). In terms of digital tool use, teachers most frequently used presentations (85.9 %), video/audio clips (81.6 %), video/audio creation tools (83.5 %), digital quizzes or polls (79.1 %), and interactive apps or games (74.3 %). In contrast, tools for online learning environments such as digital posters (38.3 %), mind maps or planning tools (42.7 %), and blogs or wikis (29.6 %) were less commonly used. Additionally, 26.7 % of the teachers reported using other tools for purposes such as story or game creation, video/audio recording, or providing feedback. Regarding their working environment, teachers reported positive perceptions of departmental support for digital resources and investment. For example, they agreed with statements such as “The department supports the development of my digital competence” and “The department invests in updating and improving the technical infrastructure” (M = 4.09, SD = 0.37). They also expressed confidence in their use of digital technology (M = 4.01, SD = 0.21). Figure 3 illustrates the teachers’ DL components based on their self-reported responses. Among the seven components of DL, teachers’ competencies in assessment, empowerment of learners, facilitation of the digital competence of learners, and professional engagement were higher than those in other components (M = 4.12, SD = 1.72; M = 4.03, SD = 0.88; M = 4.02, SD = 0.91; M = 4.00, SD = 0.87, respectively). Although competence in digital self-learning and updating was rated as the lowest component (M = 3.95, SD = 0.70), competence in digital resources was slightly higher than that in teaching and learning (M = 3.98, SD = 0.88; M = 3.96, SD = 0.96).

Distribution of teachers across DigCompEdu levels.

The results of the t-test indicated that male teachers had slightly higher levels of DL than female teachers; however, the difference between the two genders was not statistically significant (F = 0.12, t = 0.43, p > 0.01). In addition, the ANOVA results revealed no significant differences in DL among teachers based on age (mean square = 2.07, F = 3.08, p > 0.01). Regarding teaching experience, teachers with greater experience in using digital technology generally demonstrated higher levels of digital literacy, increasing from the 1–5-year group (M = 3.94, SD = 0.72) to the 6–10-year group (M = 3.99, SD = 0.72) and peaking in the 11–15-year group (M = 4.17, SD = 0.86). However, this upward trend did not continue among teachers with more than 15 years of experience, as those in the 16–20-year group reported lower levels of digital literacy (M = 3.62, SD = 0.16). Notably, the difference between teachers with 6–10 years and those with 16–20 years of experience was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Mean scores across seven digital literacy components.

4.3 RQ3. What is the extent of the digital literacy of EFL teachers based on qualitative data?

Apart from the questionnaire, the study selected ten teachers to participate in in-depth interviews. The teachers were given the opportunity to demonstrate their competencies in relation to the seven components of DL. In terms of professional development, teachers used various digital channels to communicate and collaborate with colleagues. Six out of the ten teachers reported using email and Facebook groups to share documents and exchange messages, two worked with colleagues via Zalo groups, and two used institutional platforms provided by their faculty or university to communicate and collaborate. The teachers also demonstrated how they sent instant messages, reacted to colleagues’ comments, and contributed to shared documents in these environments. Notably, the teachers tended to rely on popular digital channels for communication and collaboration.

Last year, the faculty collaborated with Microsoft to create a working environment that required us to use our school email accounts to log in. The environment is safe and private; therefore, I feel comfortable using this platform. At first, we were not familiar with it and experienced some difficulties with the new online working environment. However, after attending several training sessions, we are now able to work on it effectively.

Apart from the main platforms used for communication and sharing, teachers also employed other forms of digital technology when necessary or urgent, such as Zoom and Skype. In general, they were skillful in using these digital channels, as they frequently utilized them not only at work but also in their daily lives.

In terms of digital resources, four out of the ten interviewees demonstrated how they used available online materials and digital books to prepare lesson plans (e.g., pronunciation sounds from online dictionaries and downloaded videos, audio files, or images attached to presentation platforms). The remaining six teachers combined existing digital resources with self-created materials for their lectures (e.g., recording videos, editing or combining videos and images, creating English stories using programming software, and designing online tests).

The course books that I use include everything I need for my lectures, so I do not have to create teaching materials myself. I just use the materials that come with the digital book. Sometimes, I also use other relevant resources that I find on the Internet.

In the teaching and learning component, all teachers who participated in the interviews reported that their classrooms were equipped with projectors, laptops, and Internet access, enabling them to integrate technology into their lectures. Two out of the ten teachers occasionally used interactive whiteboards during their classes; however, this practice depended on classroom management conditions. The teachers demonstrated several lecture materials that incorporated various technologies (e.g., interactive games; online speaking platforms such as Flipgrid; and online writing platforms such as massive open online courses [MOOCs]). Their lectures were designed primarily using presentation software, such as PowerPoint and Prezi, with attached digital videos and online links, among other materials. In the classroom, three out of the ten teachers used online platforms (e.g., Nearpod, Seesaw, and ClassPoint) that allowed students to interact with their tasks, while the remaining teachers relied mainly on slideshow presentations and switched to online resources (e.g., digital games and polls) when necessary.

The Internet connection in my classroom is not stable when many students use it at the same time. Therefore, I usually use PowerPoint for my presentations. When necessary, students use their digital devices to complete tasks, while online and collaborative activities are normally assigned as homework.

Assessment depends on the types of tasks in which teachers use different technologies. For example, four out of the ten teachers reported using online platforms designed for speaking lessons (e.g., Flipgrid and podcasting tools) to assess students’ English-speaking tasks. In these cases, teachers and classmates provided feedback online. Six teachers required students to prepare digital presentations for in-class speaking practice. For English writing tasks, seven out of the ten teachers used the Review function in Microsoft Word to comment on students’ written assignments. They also used Grammarly to double-check the written work, while others provided feedback directly through online writing platforms.

I like to use MOOCs for students’ written assignments because the software supports basic grammar checking. Their classmates can read and review each other’s work if I enable that function. This gives students the opportunity to learn from their peers’ mistakes. In addition, when I grade the assignments, students also receive notifications.

For the empowerment of learners and the facilitation of their digital competence, the interviewed teachers reported that they were concerned with addressing their students’ learning needs and were interested in creating collaborative digital learning tasks. In addition, they encouraged students to create their own digital learning materials and share them with their peers.

In my English lessons, students are given the opportunity to create their own English stories related to the target topics. For example, Scratch is a visual programming language that allows students to create their own stories in English by using their creativity and language skills. Of course, students take another course where they learn how to use this software.

For self-digital learning and updating, four out of the ten teachers reported that they updated their knowledge and skills in technology use by participating in conferences or online courses. Three teachers collaborated with colleagues to learn how to use technology in teaching by observing others’ lectures and attending short training courses. The remaining teachers were members of online groups where they learned updated knowledge and skills related to integrating technology into their teaching.

Well, sometimes the workload is too heavy, and I don’t have time to update my digital skills. However, we have opportunities to join short training sessions that are organized through collaborations among universities or by higher-level organizations. We learn and practice what we gain from those trainings.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The present study was conducted to explore the DL of EFL teachers at Vietnamese universities using a questionnaire and in-depth interviews. The questionnaire used to evaluate teachers’ DL was shown to be both reliable and valid for use in the study, demonstrating construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and item-level validity through Rasch analysis. The study found that the majority of the teachers (75.6 %) are at the expert and integrator levels of DL. This result indicated a good level of DL among EFL teachers at universities. Although the competence of teachers in assessment reached the highest level, their competence in digital self-learning and updating is the lowest. The possible reason for this finding may result from the frequency use of digital technologies for assessing students’ achievement. It can be noticed that teachers are confident in their competence of using technologies in assessment because technologies could support them in checking students’ language mistakes. In a study by Do and Nguyen (2025) that measured the digital competence of English lecturers across universities in Vietnam, the researchers found that most participants self-rated themselves as having a high level of digital competence, which aligns with the findings of the current research. However, their study revealed that the highest proficiency was observed in professional engagement, while the lowest was in assessment. This pattern differs from the current research, which identified a different distribution of strengths across the competence domains, possibly reflecting contextual factors such as institutional environments or participants’ teaching experience. The qualitative data from the in-depth interviews partially confirmed the quantitative findings, as they reinforced the results of the questionnaire. It was reported in the in-depth interviews that the extent teachers used technologies in their teaching, learning as well as other tasks for the professional development also depends on the working environment, the content and format of the curriculum, the types of English skill lectures, and the facilities of the classrooms. Moreover, we were able to examine the DL of the teachers more comprehensively in their teaching context. Competence in digital self-learning and updating was included as a subscale in the DL framework proposed for Vietnamese students by Do et al. (2021). Both teachers and students should be proficient in this competence, as technology is continually evolving. As reported in the results, competence in self-learning and updating was the lowest among the six DL components. This area should receive greater attention and support, as teachers who are proficient in independently updating their digital skills are more likely to improve their overall DL, despite the rapid pace of technological advancement. Moreover, understanding the extent to which teachers can integrate technology into the teaching and learning process is a critical first step in planning investments in digital infrastructure, designing targeted interventions, and improving technology integration in education. The research findings may be useful for policy makers, curriculum designers, school stakeholders, researchers, teachers, and students who are involved in English teaching and learning with technology in specific and technology integration in education in general. In the case of gender difference in DL level, the DL of male teachers is higher than those of female teachers, although the difference is non-significant. This result is in line with those of previous studies (e.g., Guillén-Gámez et al. 2021; Do and Nguyen 2025), and against the results of some other studies (e.g., Siddiq and Scherer 2019). However, no consensus existed on this issue in different contexts, and the level of DL of individuals was dependent on various personal and environmental factors. This study has its limitations. First, the sample is small; thus, the result cannot be generalized to other educational EFL contexts in Vietnam. In addition, the number of teachers who participated in the in-depth interviews is also small. Future research that focuses on the same topic may increase the sample size and use other instruments (e.g., observations and tests) to fully and comprehensively evaluate the DL of teachers. Regarding DL instruments, updated assessment tools that reflect emerging technologies and competencies should be developed and applied in longitudinal studies. These tools should combine both subjective and objective measures to provide a more comprehensive understanding of DL among EFL teachers. It is recommended that questionnaires and interviews be supplemented with additional instruments – such as classroom observations and performance-based tests – to enhance the accuracy of DL evaluation. This approach is particularly important given the potential influence of cultural factors on self-assessment. In the Vietnamese context, for instance, male teachers may be more confident and less likely to acknowledge their limitations, whereas female teachers may tend to be more modest. These cultural tendencies could significantly affect the outcomes of self-reported data and other forms of subjective research.

Funding source: Szegedi Tudományegyetem

Award Identifier / Grant number: 8040

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board reviewed the research proposal and approved conducting the research.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the ADVANCED 150100 project provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (ADVANCED_24), by the Research Programme for Public Education Development, Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Grant KOZOKT2025-4), and the University of Szeged Open Access Fund (Grant number: 8040). The research was also supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Cluster of the Centre of Excellence for Interdisciplinary Research, Development and Innovation of the University of Szeged. Anita Habók is a member of the Digital Learning Technologies Incubation Research Group.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained upon appropriate request from the corresponding author.

References

Blin, Françoise & Morag Munro. 2008. Why hasn’t technology disrupted academics’ teaching practices? Understanding resistance to change through the lens of activity theory. Computers and Education 50(2). 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.09.017.Search in Google Scholar

Çebi, Ayça & İlknur Reisoğlu. 2022. Adaptation of self-assessment instrument for educators’ digital competence into Turkish culture: A study on reliability and validity. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 28. 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09589-0.Search in Google Scholar

Chanta-Jiménez, Sara. 2022. Uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación para la evaluación dentro de aulas de clases: Una revisión de literatura sistematizada. Praxis, Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación 18(2). 237–259. https://doi.org/10.21676/23897856.4007.Search in Google Scholar

Do, Van Hung, Tran Duc Hoa, Nguyen Thi Kim Dung, Bui Thu Thanh Thuy, Nguyen Thi Kim Lan, Dao Minh Quan, Dong Duc Hung, Bui Thi Anh Tuyet, Bui Thi Thanh Huyen, Tran Thi Thanh Van & Trinh Khanh Van. 2021. Khung năng lực số dành cho sinh viên [Digital competence framework for students]. https://ussh.vnu.edu.vn/vi/news/khoa-hoc/ra-mat-khung-nang-luc-so-danh-cho-sinh-vien-20961.html (accessed 1 July 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Do, Mai Phuong Thi & Hoang Minh Nguyen. 2025. Digital competence of English lecturers in Vietnam. Vietnam Journal of Education 9(2). 238–252. https://doi.org/10.52296/vje.2025.473.Search in Google Scholar

Education & Training Foundation. 2019. Digital teaching professional framework: Taking learning to the next level. https://www.et-foundation.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/181101-RGB-Spreads-ETF-Digital-Teaching-Professional-Framework-Full-v2.pdf (accessed 5 July 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Gilster, Paul. 1997. Digital literacy. New York: Wiley.Search in Google Scholar

Golonka, Ewa M., Anita R. Bowles, Victor M. Frank, Dorna L. Richardson & Suzanne Freynik. 2014. Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning 27(1). 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315.Search in Google Scholar

Guillén-Gámez, Francisco D., Ma José Mayorga-Fernández, Javier Bravo-Agapito & David Escribano-Ortiz. 2021. Analysis of teachers’ pedagogical digital competence: Identification of factors predicting their acquisition. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 26. 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-019-09432-7.Search in Google Scholar

Hair, Joseph F.Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin & Rolph E. Anderson. 2006. Multivariate data analysis, 6th edn. International: Pearson Education.Search in Google Scholar

Hatlevik, Ove Edvard, Inger Throndsen, Massimo Loi & Greta B. Gudmundsdottir. 2018. Students’ ICT self-efficacy and computer and information literacy: Determinants and relationships. Computers and Education 118. 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.011.Search in Google Scholar

Inamorato Dos Santos, Andreia. 2019. Practical guidelines on open education for academics: Modernising higher education via open educational practices. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.Search in Google Scholar

Krumsvik, Rune Johan. 2014. Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58(3). 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.726273.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, Allan & Dan Madigan. 2006. Digital literacies for learning. London: Facet Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 2018. Results from TALIS 2018. https://www.oecd.org/countries/vietnam/TALIS2018_CN_VNM.pdf (accessed 1 July 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Redecker, Christine. 2017. European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.Search in Google Scholar

Redecker, Christine & Punie Yves. 2017. Digital competence of educators. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.Search in Google Scholar

Røkenes, Fredrik M. & Rune J. Krumsvik. 2016. Prepared to teach ESL with ICT? A study of digital competence in Norwegian teacher education. Computers and Education 97. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.014.Search in Google Scholar

SEAMEO (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization). 2010. Status of ICT integration in education in Southeast Asian countries. Bangkok: SEAMEO Secretariat.Search in Google Scholar

Siddiq, Fazilat, Ove Edvard Hatlevik, Rolf Vegar Olsen, Inger Throndsen & Ronny Scherer. 2016. Taking a future perspective by learning from the past: A Systematic review of assessment instruments that aim to measure primary and secondary school students’ ICT literacy. Educational Research Review 19. 58–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Siddiq, Fazilat & Ronny Scherer. 2019. Is there a gender gap? A meta-analysis of the gender differences in students’ ICT literacy. Educational Research Review 27. 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.03.007.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 2013a. Guidelines on adaptation of the UNESCO ICT competency framework for teachers: Methodological approach on localization of the UNESCO ICT-CFT. https://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214726.pdf (Accessed 1 July 2024).Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 2013b. Guidelines on adaptation of the UNESCO ICT competency framework for teachers: Methodological approach on localization of the UNESCO ICT-CFT. UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education. Available at: https://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214726.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Yue & Hong Lu. 2021. Validating items of different modalities to assess the educational technology competency of pre-service teachers. Computers and Education 162. 104081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104081.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Heng-Li & Hsiu-Hua Cheng. 2009. Creative self-efficacy and its factors: An empirical study of information system analysts and programmers. Computers in Human Behavior 25(2). 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.10.005.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.