Abstract

This essay excavates the “literary structure of ecocide” through a techno-allegorical reading of Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses, particularly its staging of the “still” as both apparatus and hermeneutic paralysis. It traces how Faulkner’s text performs a self-dismantling of literary production by interrogating the very machine of its own inscription – the writing that simultaneously intoxicates and arrests temporal flux. The “still,” functioning as pharmakon, materializes the double-bind of literary representation: it produces the semantic enclave of meaning while revealing literature’s complicity in proprietization logics that undergird ecocidal acceleration. Through Faulkner’s engagement with a “blackness” that precedes racialized binarization, the essay posits a “junctureless backloop of time’s trepan” where archiolithic inscriptions might reconfigure the techno-semantic plantation economy. The analysis surfaces an anterior “literary” dimension of climate catastrophe by identifying how hermeneutical operations – ritualized hunts, circular readings, and semantic proprietization – engineer the subject as ecocidal being. Mobilizing theoretical intersections with Benjamin’s “materialistic historiography” and Stiegler’s arche-cinema, the essay positions Faulkner’s text as enacting a dolphin-flip against both modernist techniques and the “era of the Book,” suggesting that the dismantling of literary apparatuses might open toward alternative inscriptive technologies beyond the catastrophic parenthesis of Western semantic enclosures.

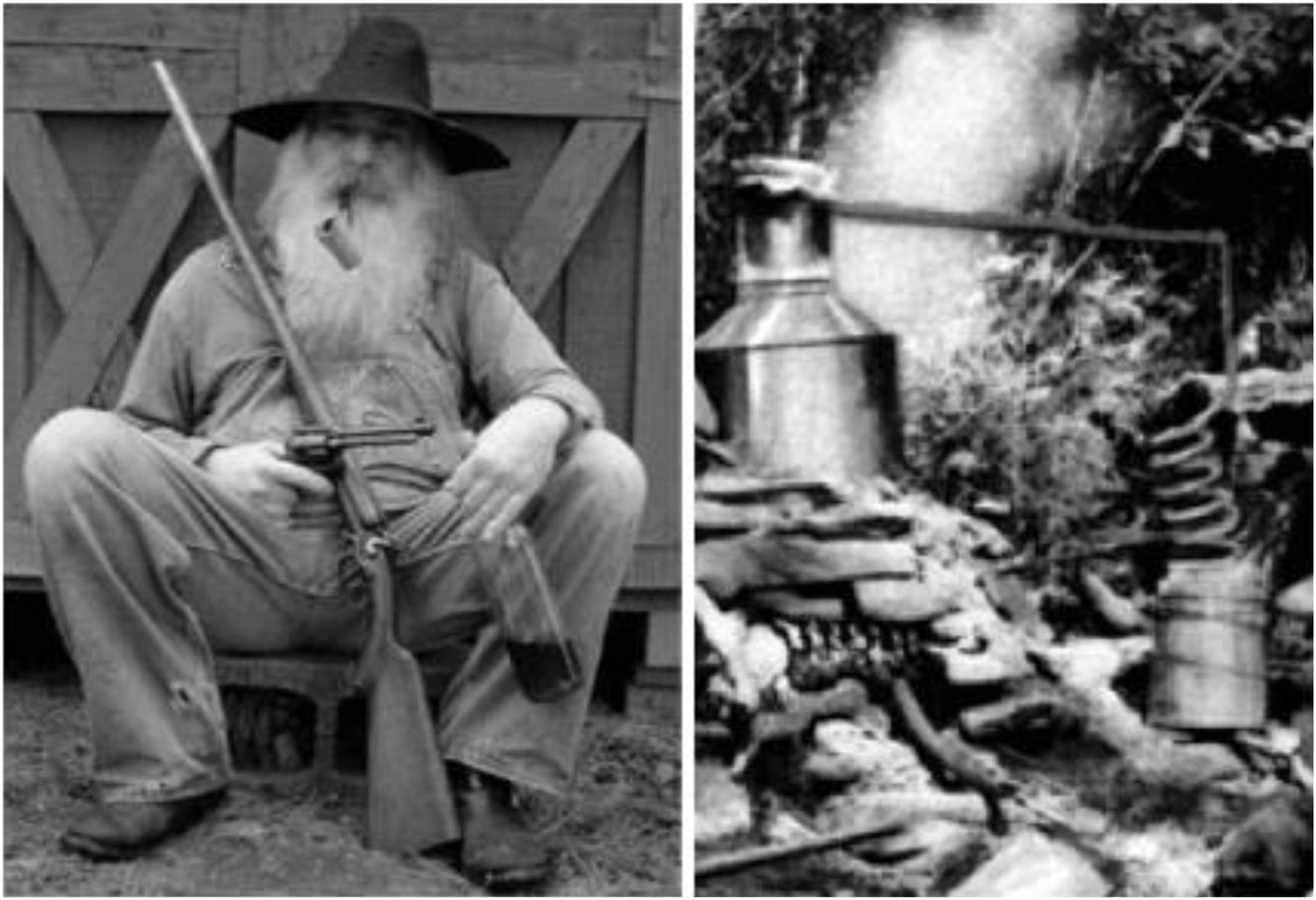

It is impossible to account for the bearded fellow in the shot above apart from the ruined still – yet we encounter him as composite: defending something with a pistol and rifle, holding a bottle and puffing a corncob. The first is the iconic “hillbilly” in the Appalachia, weaponized and guarding his bottle; the second, a moonshine kettle and a “still,” the pieces of the machine dismembered (post raid?). Together, these technics comprise a precarious semantic organism. There, curling and dismembered, is the “worm.” But it is clear which is dominant and who is the acquired guard, servicer and consumer. I was drawn to these images when envisioning the “still” in a Faulkner text I will examine. And I will suggest it double there as a technic-allegoresis of human production by and as a semantic enclave and pharmacological intoxicant – moonshine. I will use this “still” to probe a missing factor in our percolating address of “climate change”: I will call this the literary structure of ecocide (Cohen 2012, 2016; Cohen, Colebrook and Miller 2016).

1

There is an unusual text in Faulkner, embedded in a yet more unusual one (Go Down, Moses), in which something like this “still” appears. I say unusual, since it seems to me not only to be that “late” writing in which the author immerses himself in blackness most, as it is known. The volume is unusual for turning subtly yet destructively against the entirety of “Faulkner’s” production to that point, against in a way “literature.” The Moses of the title who would go down is, among others, that authorial achievement at that point (“Faulkner”) together with the era of the Book, which would be entangled with the doomed histories of proprietization and theft that would seem to be Isaac McCaslin’s (or the volume’s) ecocidal legacy. So these tales dispersed across a century, tracking different blood lines, heirs to a hermeneutic “plantation” itself run as a ritual when we first encounter it in “Was,” which opens the volume’s mosaic or fractal parts. This hunt arrives as already worn out, done in play again and again, the commodified reader enjoying the machinal movement of reading that parallels that of an escaped slave being returned (again and again) to the plantation, knowingly and without repercussion, much as the fox will be “treed” by a dog within the house by Uncle Buddy, in play, again and again. It will be repeated as a “race” with more or less sporting interest, even where, as in the last iteration closing “Was,” the dopey hunting dog that flails about “too quick” and short-circuits the “race” is named “old Moses.” It is the only appearance of the titular name of the lawgiver in the volume. “Was’” ante-bellum setting seems, nonetheless, to reflect on a paralysis within the emergent contemporary era (which is addressed in “Delta Autumn” as the European wars accelerate), which is also to say, within then modernist reading rituals. For instance, if by now Faulkner sells stories because he is famed as a regionalist of the “South,” and readers of magazines expect some “Southern” commodity, this ante-bellum frontier tale on the plantation, a frontier comedy at that, almost mocks what it is not. It is public reading models, now, that is locked in the plantation economy, or its faux version. What “civil war” does it linger before?

Note: if I say Go Down, Moses is Faulkner’s work most on blackness, I do not only say it is only so on blacks or black people alone. The blackness that it accesses seems to precede the binarization out of which white and black, light and dark, are valorized and nominalized; it precedes the artifice of “light” – say, the fire and the hearth, and veers into an order of inscriptions that, in “The Bear,” will be put into question with the great “epochs” of the Book out of which America, American slavery, and the proprietization of the “old earth” enters as a sheer technic. Without comment for the moment, there is a blackness within the “black” sociographs, one that is tied to something like technics itself, inscriptions, yet which, because it precedes white and black, or “light” itself, like a film projector before it is juiced on, is not mimetic at all – hence its perpetual escape from (and return to) the semantic “plantation”: it is this factor, that an archiolithic trace is appealed to before the era of the Book, before and outside the plantation hermeneutics that has paralyzed “literature,” before a “Moses” who is both giver and destroyer of inscriptions, that a line like the following in the blackest of black writings here, “Pantaloon in Black,” can be engaged and has relevance, today, for emerging, like an escaped slave, from the literary anthropocene “era”: I am thinking to the line referenced to the titanic black laborer at the paper mill, Rider, in whose name we hear both (Writer and Reader, as he “crosses” to tool-room to confront the cheating “white nightwatchman,” Birdsong: “the junctureless backloop of time’s trepan.”).

When we get to a later tale, “The Fire and the Hearth,” we may not notice the return of this machine. It is a machine, “the still” mentioned above, which this time the tale wants to put out of play, remove from the literary kitchen, much as the short-circuiting of reading itself seems mimed as a fateful ritual paralysis earlier in “Was.” Faulkner seems to be casting out, or isolating, different machines the writing had dependent on, manipulated, or been produced by – as if to see whether Faulknerian writing can escape, again and otherwise, the historical envelope that constrains it, as he knows, going back at least to Homer (as we see in “A Rose for Emily”), or here, whatever “Moses” implies. It is opening this tale that the black character Lucas Beauchamp, a then freed tenant farmer during the “reconstruction” on what had been the plantation, makes a move that begins a long comedy. If literary writing is the drug, intoxicant or pharmakon that would respond to a greater poison of history itself, yet cannot stop extending or being appropriated by the latter (the returned escaped black slave), how does one interrupt this drip – this liquor about which Faulkner has much to do and to write (particularly in “Pantaloon”), to the point of checking in a sanitorium to detoxify during the period of writing here, must be curtailed at its source – or at least, the hermeneutic apparatus that guarantees circular, consequenceless rituals of reference and meaning. The hunt, like reading, is short-circuited when the gold it seeks is planted in advance, when the prey (fox, slave) knowingly plays the role and returns. Faulknerian writing (if one considers that at an event and an archival network) does an unusual thing here, as mentioned. What do we say about a narrative that removes “moonshine” from its arsenal of effects, and does so by removing the “still” itself? It is of interest, however, when we pose the question today of a literary structure of climate chaos itself:

First, in order to take care of George Wilkins once and for all, he had to hide his own still. And not only that, he had to do it singlehanded – dismantle it in the dark and transport it without help to some place far enough away and secret enough to escape the subsequent uproar and excitement and there conceal it…. The spot he sought was a slight overhang on one face of the mound; in a sense one side of his excavation was already dug for him, needing only to be enlarged a little, the earth working easily under the invisible pick, whispering easily and steadily to the invisible shovel until the orifice was deep enough for the worm and kettle to fit into it, when – and it was probably only a sigh but it sounded to him louder than an avalanche, as though the whole mound had stooped roaring down at him – the entire overhang sloughed. It drummed on the hollow kettle, covering it and the worm, and boiled about his feet and, as he leaped backward and tripped and fell, about his body too, hurling clods and dirt at him, striking him a final blow squarely in the face with something larger than a clod – a blow not vicious so much as merely heavy-handed, a sort of final admonitory pat from the spirit of darkness and solitude, the old earth, perhaps the old ancestors themselves… – a fragment of an earthenware vessel which, intact, must have been as big as a chum and which even as he lifted it crumbled again and deposited in his palm, as though it had been handed to him, a single coin.[1]

Faulkner’s “still” is to be buried in an earth, effaced. Yet that triggers “old earth” to be then exposed, saturated with time, fall out, and then only to give up another artifact or technical object – an earthen vessel with a gold coin. The clods disclose another machine. The imprinted coin not just money (yet) but the gold, what triggers all mad pursuit, and itself a pure technic. Lucas Beauchamps tries to bury or disappear the “still” – we are talking moonshine here, illegal brew with a kick, and a reflective, lunar shine – and gets hit by another, homelier jug of sorts (perhaps what Wallace Stevens calls a “jar,” whose poetic lineage runs elsewhere in Go Down, Moses to a recitation of Keats’ urn). The “still,” as the word suggests, at once distills, or in-toxicates, and is addictogenic, and promises an arrest or stilling of an unreadable flux. Lucas Beauchamp, in a tale from after the civil war, is a then freed tenant farmer during the “reconstruction” on what had been the plantation, makes a move that begins a long comedy. Accordingly, Lucas is the black tenant farmer renting on what was the old plantation – a hermeneutic plantation of rituals of hunts, of escapes and returns, with a spell going back to its absent patriarch Carothers. Lucas’ blackness however cannot be ciphered in a face that precedes and moves behind or absorbs faces, antedates its original, defaces:

the face which was not at all a replica even in caricature of his grandfather McCaslin’s but which had heired and now reproduced with absolute and shocking fidelity the old ancestor’s entire generation and thought – the face which, as old Isaac McCaslin had seen it that morning forty-five years ago, was a composite of a whole generation of fierce and undefeated young Confederate soldiers, embalmed and slightly mummified – and he thought with amazement and something very like horror: He’s more like old Carothers than all the rest of us put together, including old Carothers. He is both heir and prototype simultaneously of all the geography and climate and biology which sired old Carothers and all the rest of us and our kind, myriad, countless, faceless, even nameless now except himself who fathered himself, intact and complete, contemptuous, as old Carothers must have been, of all blood black white yellow or red, including his own.[2]

One notes about Lucas’s “still” two things of relevance to an early 21st century scan of a literary structure of “climate change” – that is, really and in fact, the cause, if you like, of the disarticulation of the biosphere and climactic tectonics by man. You doubt me? Let me be precise by what I mean: I am not interested in how these new ecocidal horizons, in which suddenly an “anthropocene” era is acknowledged (oh, my!) which is synonymous with accelerating extinction events, or how we can now read these logics as in the archive from its inception (back, aesthetically, to what Bernard Stiegler calls arche-cinema – that initialization of perceptual orders, movement, mimesis, collective mnemonics, animation, the hunt, and the play of “light” on the walls of caves, sketches of megafauna and animemes thirty-odd thousand years ago). I am not interested, here, in a literature of climate change that is emerging with great difficulty in novels, as Amitav Ghosh has targeted for remark. Unlike disaster cinema, that is, where a certain climate change panic has been channeled, if in a distinctly anaesthetizing way (someone always survives and renews the future). Such an-aestheticization plays into something that no one seems to note yet: the arrival of something like the 21st century politics of (managed) extinction. (And you were wondering why the “0.0001 %” needs to now own all that stuff, from water to robotics, going forward?)

By saying literary cause of “climate change” I am aware it invites ridicule on numerous fronts – “You mean,” let me say this for you, “this zone we have all moved beyond, literary stuff, the aesthetic, is actually where the impasse of ecocide resides or is engined?” Lucas, here, would probably go silent, maybe even retreat behind a wall of clichéd blackness: “Without changing the inflection of his voice and apparently without effort or even design Lucas became not Negro but nigger, not secret so much as impenetrable, not servile and not effacing, but enveloping himself in an aura of timeless and stupid impassivity almost like a smell.” I will do the same, to a degree, since there is a black optics in this writing (in all writing) that I will draw on later. For now: even if the topos of “language” and climate change has been ignored, I will resist the long dossiers that need still to be assembled here, many just practical in nature, to focus instead on something quite precise: the way in which, it would seem, a certain hermeneutical tick naturalized in Western discourse conforms to how hyper-industrial “man” is produced and re-enforced as an ecocidal being – that certain ways in which meaning has been produced consolidate this, and even play to the forms of occlusion staged or encountered today.

What Lucas calls his “still,” which is also that of Faulkner, is what produces this socialized discourse of the “we.” The “still,” in effect, must be set aside. The addictogenic and machinal at the same time in Go Down, Moses – in which the gold coin sought by the “divining machine” is like that meaning or revelation which the reader seeks and hunts down like gold.

There are, nonetheless, vast zone where the question of language, read, epistemic regimes, metaphoric idiocies, engineered for failure public terms, and climate chaos churn the mill, quite aside from troll armies of post-truth vintage, and this starting with the most obvious and leading through cognitive and neural settings: for one, the abyssal public nomenclature that surrounds these realities, a mix of dead metaphors and flat scientisms which corporate-sponsored denialists must have considered a gift; another: the streams of corporate media and memory programs that have disarticulate attention; and then, the “literary” origins of key cultural memes or ideologemes (“Nature” as a commodified misreading of Romanticism). And so on – all worthy, but I am after something else. What I do have in mind is more lethal, and it returns us to the “still.” [3]

Faulkner’s disassembles his own writing machine in Go Down, Moses – a “late” work that turns against the writer’s own preceding production he questions as a “literary” game mastered within the era of what is called “the Book.” The Moses of the title encompasses, or marks as a stutterer and forger, some first giver of inscriptions and “the Book” (as its called in “The Bear”). It could be said to put the former in its entirety in question, drifting into the black zone (black voices and networked figures, blackness as what precedes “light” or the binary of white and black dependent on it – in the “old earth”). So it digs up, here, one of the machines of the literary plantation and the epoch of the Book, or rather, it buries it, tries to efface or hide it, triggering a long narrative detour where a new, spiffier machine will be introduced directly to hunt gold coins, a metal detector (early vintage), called a “divining machine” and full of accessories (“an oblong metal box with a handle for carrying at each end, compact and solid, efficient and business-like and complex with knobs and dials”). Three machines appear in Lucas’ trajectory, a strangely negative autoscopy that the writing performs on itself – now that the greats works were written and assembled, (“Faulkner,” or what he names “Yoknapatawpha”).[4]

You will forgive my starting out with a reading – even a truncated, literary one, but you will have noticed the “literary” part seems in meltdown here. Even when reading seems portrayed as comic ritual, like the eternal return of the escaped slaves (who are in on it too), the paralysis of the sterile twin brothers, or the closer it comes to invoking an “old earth,” the more machines, artefacts (vessels), or stamped gold coins proliferate – even when the latter will, later, be planted only then again to be “found” by the divining machine, as if manipulating readers into thinking they “discovered” new meanings in their reading as a controlled if ritual hunt. In fact, the hunt will have, from the first text in the volume on (“Was”), been a game, with everyone knowing the rules, to be repeated endlessly. That is, the prey itself (fox, runaway slave) is in on it too: such a consequence free “race,” as its called, is to be evaluated aesthetically. It will be fun or brisk or “too quick.” It will be like so may variations of “literature” or interpretation – repeated again and again. Thus the first tale, “Was,” ends with the dog Old Moses chasing a fox named So(u)they. These names put us into a cartoon world (like the name Popeye in Sanctuary), only the kitsch now is “literature” and the duped readership chases, finds what’s planted there, and dopily rejoices as the crate hangs about its neck: “Old Moses went right into the crate with the fox, so that both of them went right on through the back end of it. That is, the fox went through, because when Uncle Buddy opened the door to come in, old Moses was still wearing most of the crate around his neck until Uncle Buddy kicked it off of him.”[5] Again, let us leave the doggie’s name out of this, “old Moses,” the name of the Lawgiver and transcriber into stone tablets of Yahweh’s initiating inscriptions, the stutterer who goes down with a Nietzschean inflection of “going under,” yet who comes down, also, twice with his laws, the first time smashing them and then replicating, making a copy or second original (for stone tablets, about a month’s time). Across Go Down, Moses we witness a sort of absolute mourning at work, as in “Pantaloon in Black,” but also a mourning for the old woods, and an earth, and a precession not only of “America’s” artefaction by theft (the imposition of men like “old Carothers” who proprietized all). One also witnesses where “Faulkner” does a dolphin-flip of sorts – turning against the array of “modernist” techniques and the era of the Book which he, this writing, assembled and proprietized (the alien-tongued “Yowknapatawpha” county, Faulkner the proprietor). That is, it seems to turn against an age of “literature” that would have been, inescapably, complicit. The entire volume simulates the titanic black laborer at the logging mill, Rider, wandering about beyond intoxication, beyond mourning his dead wife “Mannie” (little man). Rider’s name echoes the words writer and reader at once, as he circles from the mill – where logs (or logoi) are tossed about like matchsticks, and where, properly, paper would be produced – to the “tool shed” where the crapgame run by the white nightwatchman, Birdsong, cheating the black mill workers as a ritual all sides repeat, to catch him out and cut his throat with a razor as the latter’s pistol was coming out. Before he severs Birdsong’s head with a razor, essentially, he is described as passing “the junctureless backloop of time’s trepan.” This line puts on display what the writing’s experience of itself would be: the precession of a representational history, doomed and criminalized at appearance (enslaving, stealing, creating “property”), in which the writing machines of the era of “literature” going back through Rome, Greece and Egypt will be cited and preceded. A trepan is a surgical operation in the back of a skull itself, to alter physically the head’s ill – a cutting, or re-inscribing, like trying to reach impossibly behind oneself to lift oneself up. Here practiced on time, the “junctureless backloop” posits, within the writing systems put in play by the illiterate Rider, an altering of inscriptions out of which time would be disorganized or reprojected. The experience mimes a logic invoked by Walter Benjamin’s “materialistic historiography,” by which dormant anterior archival nodes (“pasts”) would be restitched to advance alternative “futures” to those being closed out – the enemy in which is any form of “historicism,” which is also to say, mimeticism, empiricism, phenomenology, pragmatism, materialism, and so on: literalizing programs of reference that function like the trains introduced to the big “woods” (extending the ledgers in “The Bear”). What does it mean, however, to hit this sweet spot, so to speak, this “junctureless backloop of time’s trepan,” such that something like the inscriptions by which time, perceptual apparatuses, and historial devastations can be recast?

2

I return to the “still” which Lucas tries to bury, hide, or take out of play – precisely when he encounters an alternate machine spit back at him from the dark soil, hit him in the face, and deliver the ruinous, haphazard gold coin that, in any event, had been placed there and forgotten by some erased hand. If in Go Down, Moses a certain Faulkner turns against the entire premise of the Western writing machine, it puts the achieved authorship called “Faulkner” into question (the last tale, titled as the book itself, “Go Down, Moses,” puts out the word “catafalque” to name this going under).[6] It opens, in “Was,” at once too early and too late: the rituals of repetitive modernist interpretations are already, in the ante-bellum plantation world, an empty game in which the chase, hunt, or reading quest is returned to the same place again and again, all in on it, the repetition deteriorating as the aesthetic pleasure wanes. The final caricature of “old Moses,” the hermeneutic hunting dog reminiscent of Disney’, with a crate around his head, mimes this limit – and puts something like a child’s cartoon, say featuring Disney’s Pluto, at the pre-origin of the writing scene and histories the volume engages from it, that of the two aged and sterile twin brothers, Amodeus and Theophilus, Buck and Buddy, the disavowing plantation owners who keep up appearances yet, short of the intervention of the text “Was,” would terminate in advance the family line and continuum.

“Was” presents a comic script about these ante-bellum plantation rituals being undone. The old sterile twins living as if man and wife gather in themselves every faux binary by which the plantation order would have been patriarchally managed – an order inverted and disowned but by the twins but simulated in inverse play (slaves sleep in the unfinished big house, can run out at night if they are back at dawn, will be hunted and restored if they run off, which they know and assist). So, when Lucas turns to a certain familiar machine, a “still” which produces moonshine, an apparatus to be buried in the earth itself, something would be set aside within this time scape and deteriorating historial archive (identified with a canine Moses, and going under or down). What, again, did Nietzsche have in mind by this going under – again, since I forget, frankly: it cannot be stepped out of afterall, any more that the pan-technic toxicologies and spells that a hyper-industrial “society of dis-affected individuals” (Stiegler), can step outside of an encompassing and consolidating encirclement and penetration of mnemotechnic streams that interrupt attention, loss care, and “proletarianize” the senses themselves.

So, why does the writing put the “still” itself away – or try to? That, by a black figure who antecedes all facial histories and derivations (particularly when he mimes the category of “nigger” – the black blackness that dissimulates before any reader) (particularly, but not only, white readers: “Pantaloon in Black” opens describing a: “barren plot by shards of pottery and broken bottles and old brick and other objects insignificant to sight but actually of a profound meaning and fatal to touch, which no white man could have read”). Moreover, why, at an obscure site in a somewhat marginal script by an “old white guy” author, do I seek, or pretend to, a literary dimension to “climate change” itself – its actual prosecution, mutation, irreversible and ecocidal logics?

What is Faulkner doing (again) in the mud, stepping outside the entire mnemotechnic parenthesis of the Book, the proprietization of eveything, and its own complicity, signalled by the recedivist old Isaac in “Delta Autumn,” the hope of the lineage or volume, who only delays extinction of the family line by a generation and who attempts self-dispossession, stepping outside of the propertied inheritance and procreative chain, to no avail. While Go Down, Moses is the premier work on black figures in this canon (Faulkner’s), it veers toward a blackness that antecedes racially defined blackness, that locked in a binary system with light or whiteness – like that attributed, in Sanctuary, to the figure and eyes of Popeye (“like black knobs”), face melted away like candle wax, also illiterate, a criminal prosthesis given to corncobs, the violating inversion of any sanctuary, “interiority,” cave, eco, or literary legalism.

The “still,” of course, is a curious machine, on which the dark libidinal economy and nervous system of the rural communals depend: it distills and drips a poison, or technic pharmakon, that would be put out of play as Go Down, Moses fields various combinatoire or algorithms of the impossibility of escaping a doomed parenthesis – what I will, in a moment, like not to “ecological” thinking and the faux idyllicism of the overrun and dilution of a civilization (since this is what is at stake, then, as now, the replacement of a “civilization,” only it is not the one of a few decades or centuries, but antecedent to Moses, Egyptian pictograms and “time” – it encompasses and precedes, necessarily, arche-writing in its institutional formations). It, the “still,” arrests itself. While I will liken this zone of a literariness before “literature,” to Stiegler’s positing of arche-cinema in a moment, the prehistorial initializing of a technic history, mnemonic setting, and collective form of mimesis (all cinematic in structure), (or to what Benjamin invokes as the prehistorical and a “natural history” specifically voiding the both nature or history), I am more distracted by this idiot “still” itself – with its ridiculous hollow bellied kettle and “worm.” Its intoxicant is a drug, the equivalent today of industrial meth-labs in the rural south, through which the community is sustained, and it is of course double in its drip: the first, drip, equally ambivalent, is the drug of literary trances and forms of consumption art extends – an imaginary “still” or interruption of the flux of disappearances without remains. But the second perhaps absorbs the first, much as the ritual of “literary” interpretations as the repetitive and consequenceless rehearsal of a hunt that returns the escaped prey in mutually agreed play to the same place, gaming again and again, as the plantation order (which references not the ante-bellum imaginary in fact, but the state of the readership and “modernist” moment contemporary to the writing).

I would like, accordingly, to extract this “still” as an image, and carry it off to examine – as if, like Lucas, extracting it from the cultural or hermeneutic machine that seems trapped in this bad eternal recurrence. To return as if to or posit a “junctureless backloop of time’s trepan” identifies the non location of this performative defacement and resetting of inscriptions – out of which “reals” are generated, histories disastrously programed, ecocides decided.

References

Cohen, T. 2012. “Polemos: ‘I Am at War with Myself’ or, DeconstructionTM in the Anthropocene?” Oxford Literary Review 34 (2): 239–57. https://doi.org/10.3366/olr.2012.0044.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, T. 2016. “Escape Velocity: Hyperpopulation, Species Splits, and the Counter-malthusian Trap (After ‘tipping Points’ Pass).” Oxford Literary Review 38 (1): 127–48. https://doi.org/10.3366/olr.2016.0183.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, T., C. Colebrook, and J. H. Miller. 2016. Twilight of the Anthropocene Idols. London: Open Humanities Press.10.26530/OAPEN_588463Search in Google Scholar

Faulkner, W. 1990. “The Fire and the Hearth.” In Go Down, Moses, edited by 1st Vintage international. New York: Vintage.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai Jiao Tong University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction: On Reading

- The Simple and Initial Literary Reading Its Characterization, Importance, and Power

- The Art of Poetry and the Poetry of Art in Shakespeare’s Sonnets

- Close Reading at a Distance: Genre, Realism, and Ecology in Robinson Crusoe

- Close Reading and Irish Poetry: Antoine Ó Raifteirí, Pádraig Ó hÉigeartaigh and Seamus Heaney

- Happy Translation and the Now of Recognizability: Walter Benjamin’s 1936 Dialogue

- Faulkner’s “Still” and the Closure of Ecriture

- The Recovery of Self in Emotional Authenticity: Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun

- Translation as Method: Exploring Soundscape in Travel Writing through Intersemiotic Translation

- Eye Movement Patterns of Reading Literary Texts for Translation

- Hölderlin’s Quake

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction: On Reading

- The Simple and Initial Literary Reading Its Characterization, Importance, and Power

- The Art of Poetry and the Poetry of Art in Shakespeare’s Sonnets

- Close Reading at a Distance: Genre, Realism, and Ecology in Robinson Crusoe

- Close Reading and Irish Poetry: Antoine Ó Raifteirí, Pádraig Ó hÉigeartaigh and Seamus Heaney

- Happy Translation and the Now of Recognizability: Walter Benjamin’s 1936 Dialogue

- Faulkner’s “Still” and the Closure of Ecriture

- The Recovery of Self in Emotional Authenticity: Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun

- Translation as Method: Exploring Soundscape in Travel Writing through Intersemiotic Translation

- Eye Movement Patterns of Reading Literary Texts for Translation

- Hölderlin’s Quake