Challenges and requirements of AI-based waste water treatment systems

-

Antoine Dalibard

, Lukas Simon Kriem

Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising tool for enhancing the efficiency, accuracy, and sustainability of water treatment systems. However, integrating AI into water treatment comes with its own set of challenges, and specific requirements must be met to fully utilize the potential of these techniques. This study delves into the complexities associated with implementing AI in waste water treatment (WWT) and the necessary prerequisites for developing effective AI-based solutions. The most commonly utilized AI techniques in WWT applications fall under the umbrella of supervised Machine Learning (ML). Supervised ML models serve as excellent tools (correlation coefficient >0,8) for modeling, predicting, and optimizing WWT processes. They have a wide range of applications, including data cleansing, system design, control optimization and predictive maintenance. ML models are particularly useful in optimizing process parameters with significant energy savings achievable (up to 30 % reported in literature). The main challenges for the implementation of such models in WWT are: quality data availability, efficient data management along the data chain and the choice of appropriate ML models. These challenges are highlighted with two concrete examples in the field of water reuse for microalgae cultivation and predictive maintenance of cooling towers. These examples showcase the diverse range of potential use cases for AI and machine learning, especially in wastewater applications.

Zusammenfassung

Künstliche Intelligenz (KI) hat sich als vielversprechendes Werkzeug zur Verbesserung der Effizienz, Genauigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit von Wasseraufbereitungssystemen erwiesen. Die Integration von KI in die Wasseraufbereitung bringt jedoch eine Reihe von Herausforderungen mit sich, und es müssen bestimmte Anforderungen erfüllt werden, um das Potenzial dieser Techniken voll auszuschöpfen. Diese Studie befasst sich mit der Komplexität, die mit der Implementierung von KI in der Abwasseraufbereitung verbunden ist, sowie mit den notwendigen Voraussetzungen für die Entwicklung effektiver KI-basierter Lösungen. Die in der Abwasserbehandlung am häufigsten eingesetzten KI-Techniken fallen unter das überwachte maschinelle Lernen (ML). Überwachte ML-Modelle eignen sich hervorragend (Korrelationskoeffizient >0,8) für die Modellierung, Vorhersage und Optimierung von Wasseraufbereitungsprozessen. Sie haben eine breite Palette von Anwendungen, einschließlich Datenbereinigung, Systemdesign, Steuerungsoptimierung und prädiktive Wartung. ML-Modelle sind besonders nützlich bei der Optimierung von Prozessparametern, wobei erhebliche Energieeinsparungen erzielt werden können (in der Literatur wird von bis zu 30 % berichtet). Die wichtigsten Herausforderungen bei der Umsetzung solcher Modelle in der Kläranlage sind: die Verfügbarkeit hochwertiger Daten, eine effiziente Datenverwaltung entlang der Datenkette und die Auswahl geeigneter ML-Modelle. Diese Herausforderungen werden anhand von zwei konkreten Beispielen aus dem Bereich der Wasserwiederverwendung für die Mikroalgenzucht und der vorausschauenden Wartung von Kühltürmen aufgezeigt. Diese Beispiele zeigen die Vielfalt der potenziellen Anwendungsfälle für KI und maschinelles Lernen, insbesondere im Abwasserbereich.

1 Introduction

Water is a finite and essential resource, playing a pivotal role in sustaining life, agriculture, industry, and ecosystems. With the growing global population, urbanization, and the impacts of climate change, the demand for effective water reuse systems has become more critical than ever. In this context, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising tool to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and sustainability of WWT systems [1]. AI-based water systems leverage sophisticated algorithms, machine learning, and data analytics to enhance the efficiency of WWT processes. The current applications are diverse: predictive maintenance, control optimization, real-time monitoring and fault-detection as well as decision support tools [2], [3]. Therefore, the potential for improvement of such systems is expected to be significant [4], [5]. However, the integration of AI in water treatment is not without its challenges and specific requirements need to be met in order to utilize the potential of such techniques [6], [7]. Especially, the need of a huge amount of quality data still remains a barrier for an accurate and successful implementation of AI based solutions [1], [3], [8].

This work does not aim to review extensively the AI solutions in the field of WWT systems. It rather explores the complexities associated with implementing AI in WWT systems and the essential prerequisites for developing effective and reliable AI-based solutions. Finally, it will give an introduction into successful implementations of AI for control optimization and predictive maintenance of water-based systems.

2 AI in wastewater treatment plants

2.1 AI techniques used for water treatment systems

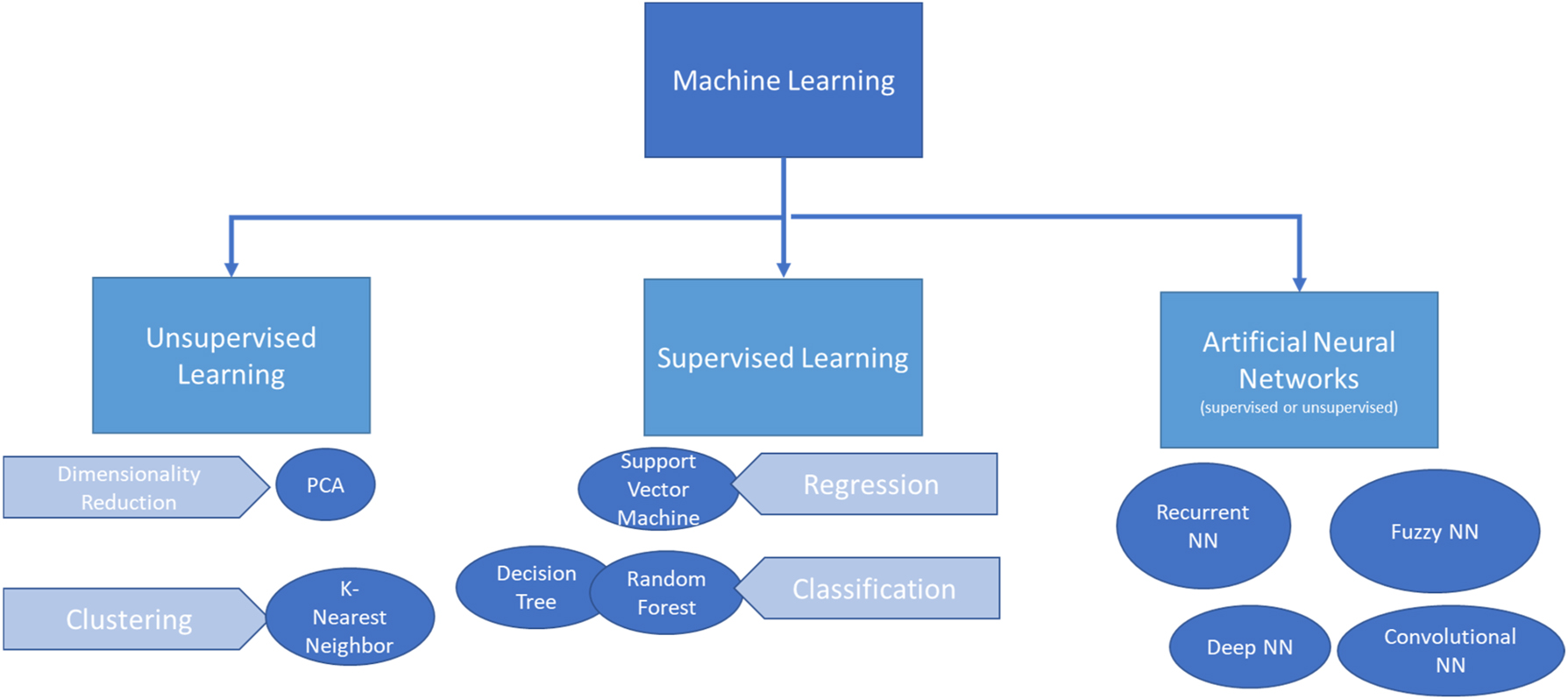

The increasing abundance on AI applications and literature has resulted in a diversity of artificial intelligence models and subcategories which can be often modified to fulfil different purposes or even combined to cater for the most complex applications [9]. One way to handle the vast amount of information is to take a step back and look at the different techniques most commonly used when deploying AI for matters of wastewater treatment. Considering that most models and algorithms have initially been developed to serve other purposes, such as business problems, a lot of work has been invested in the tailoring of AI methods [3]. Without any claim to completeness, Figure 1 illustrates the most commonly used AI techniques found in water treatment applications. The vast majority fall under one or more disciplines of Machine Learning (ML).

Most common AI techniques used in water and wastewater treatment refer to ML and its subcategories. ANNs can classify as either supervised or unsupervised learning depending on the exact technique.

ML aims to create models for accurate prediction and decision-making based on learned data. Common ML models include Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Decision Tree (DT), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Self-Organizing Map (SOM) and Adaptive-Network-Based Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS). ML techniques can be distinguished between whether models are trained on a labeled dataset, where the input data is paired with corresponding desired outputs (=supervised learning) and model training on unlabeled data (=unsupervised learning), where the system must find patterns, relationships, or structures within the data on its own. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) use unit nodes to simulate neurons, processing information by adjusting interconnection weights between nodes. ANNs typically comprise an input layer, hidden layers, and an output layer. Activation functions like sigmoid, tanh, and ReLU introduce nonlinearity for complex computations. As the number of hidden layers increases, ANNs can build more intricate nonlinear models, enhancing their expressive capabilities. The most used ANN models mainly include Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Fuzzy Neural Networks (FNNs) and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) (see [5] for details).

ML models are a great tool for modeling, predicting, and optimizing WWT processes (WWTP). The main applications include removal of diverse water contaminants, process control and optimization, anomaly detection and system diagnostics as well as data management and decision support system [5]. Research led by El Fels et al. highlights the prevalence of supervised learning in wastewater treatment, with popular models including ANN, RF, SVM, LR, ANFIS, DT, and GB. The analysis showed that more than 30 articles have been published on the adsorption technique. Activated sludge has been the subject of more than 25 studies, followed by more than 10 articles on screening and constructed wetland systems [7]. The study shows that the choice of the proper model depends on the considered water treatment technology and the data available for training (see Figure 2). Since a typical WWT plant consists in different separated processes, a global AI-based WWT system might used different ML modelling approaches [1], [6].

Post et al. developed a real-time monitoring method for micropollutants in WWTPs by deploying a combination of a CNN model and laser-induced Raman and fluorescence spectroscopy (LIRFS). This approach demonstrated exceptional precision (R 2 = 0.74), surpassing detection limits and successfully identifying micropollutants that might escape detection when using conventional WWTP monitoring methods [10]. Nnaji et al. predicted the removal efficiencies for COD and colouring solids from textile wastewater using a biobased coagulant prepared from seed extract (Luffa cylindrica). The authors used RSM, ANN and ANFIS to predict the performance. With an R 2 of 0.99 ANFIS showed the best model performances for COD elimination [11]. In Cuxhaven, Germany, a WWTP operator implemented achieved a 30 % reduction in aeration energy demand by using virtual sensors to estimate incoming C, N, P loads and further predict the best set points to operate the aerators. ML models were created for the carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous elimination processes by utilizing data from the plant’s SCADA system [4]. The examples emphasize the broad spectrum of potential use cases for AI and ML in particular for wastewater applications.

However, a generalized implementation of AI techniques in WWT is currently limited by some hurdles all along the data chain: insufficient data availability for model training, model complexity and interpretability, integration with existing systems (control, data management) [1]. Therefore, a successful implementation of AI solutions in WWT can be achieved if some technical requirements are respected all along the data process chain [12].

![Figure 2:

Cross matrix of WTP processes and investigated ML method (Source: [7]).](/document/doi/10.1515/auto-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_auto-2024-0023_fig_002.jpg)

Cross matrix of WTP processes and investigated ML method (Source: [7]).

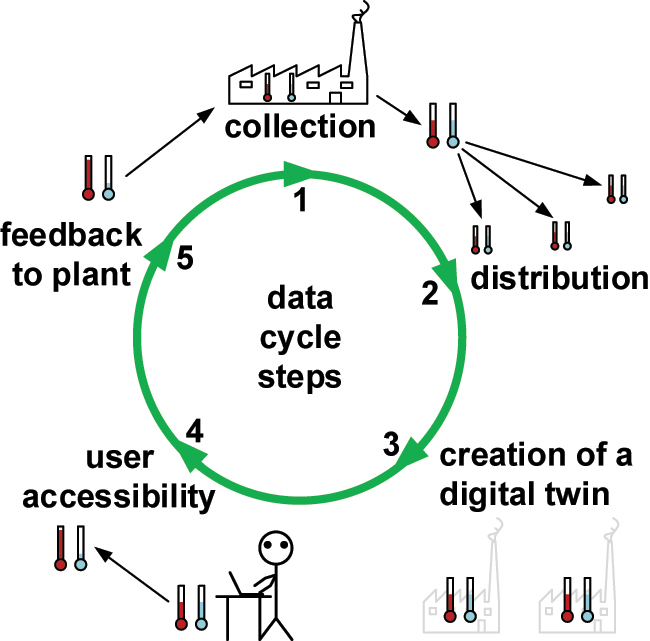

2.2 Technical requirements and challenges for AI implementation

The successful implementation of AI in water treatment systems relies on specific requirements all along the data chain, from the data collection to the actual feedback to the plant (Figure 3). The main pre-requisites for the data cycle steps and the challenges associated to their implementation are discussed in the following.

Technical requirements for the implementation of AI in water treatment systems.

2.2.1 Data acquisition/collection

In a first step, sensor data of the water plant (e.g. temperature, flow rates, pH, electrical conductivity …) have to be collected and stored. These data are then transformed by a programmable logic controller (PLC) into digital values with specific time intervals and accuracy. The challenge is to determine the necessary time resolution and accuracy for each data point in order to create a meaningful digital representation of the plant. These data points are then stored using a time series format in a structure which is derived from the real system structure. For water treatment systems, this structure is often based directly on the piping and instrumentation diagram (P&ID) of the plant.

2.2.2 Data distribution/communication

Another important step is the data communication between the different actors of the data chain [12]. It depends mainly on the infrastructure available on-site like satellite, mobile or fixed network and sometimes on the available energy. A preferred implementation is the use of cloud servers which are used as relays to receive, merge and distribute data in a structured way. When selecting a suitable technology, latency, robustness, availability, scalability must be considered. A latency time of up to one second should be acceptable for a wastewater treatment plant; servers offered as standard can meet this requirement.

2.2.3 Digital twins

Once the data are stored in the structure, a digital twin of the plant can be created by using different AI techniques, as shown previously. Here, the main challenges for developing accurate models are to ensure both data availability and data quality. Indeed, the successful development of digital twins rely on a reasonable set of historical data able to describe the behavior of the plant by changing process parameters. The digital twin can be operated directly on site (edge computing) or remotely via the defined communication system.

2.2.4 User accessibility

This step consists in making data access easier for inexperienced users (time stamp synchronization). In the past, potential users (e.g. technical staff without specific IT knowledge) have struggled to benefit from digitalization because they found it too complicated to access. To address this, the stored data structure is based on reality (plant physical architecture) and can be easily accessed if one has knowledge of the wastewater treatment plant. Commercially available programs like Excel, Origin, or MATLAB can be used for access without additional tools. User-generated data is also included in the digital twin, and it can be added without the need for extra tools.

2.2.5 Feedback to the plant

The last step deals with the sending of AI-generated data to the actuators, for e.g. in the case of an AI-based control optimization. The PLC can then access this data and uses the values as setpoints to control the wastewater plant. It is crucial for the PLC logic to check the setpoints for meaningfulness and approve them before using them. For instance, specifying a liquid water temperature setpoint above the boiling temperature of water at the given working pressure has to be avoided. In such cases, a default value is assumed, and a warning message is given to the plant operator.

2.2.6 General challenges

The use of AI in water and in particular in wastewater systems is a high-potential and challenging domain. Besides the technical requirements there are conceptual and general challenges relating to the characteristics of water systems that need to be taken into account when developing or deploying AI in these sectors. For example, some of the most crucial water parameters for environmental and health compliance (microbiology, COD, BOD, …) have to be analyzed in laboratories resulting in lower data quantities compared to sensor data as well as complex temporal and statistical relationships. In addition, many AI techniques require large amounts of data to reflect a certain variability in the processes in order to build robust models. As treatment plants usually have fairly stable processes this requirement implies a long data collection time. Insufficient data can increase the risk of overfitting a model, in which the model can give good results within the boundaries of the training data but struggles to extrapolate results beyond those boundaries, or underfitting when there is not enough data. Further challenges arise from the natural drift of sensors which can decrease data credibility with implications for the model and its interpretation. This is currently the main barrier for advancements towards self-learning systems, the ultimate vision for AI.

Choosing the right machine learning model for a wastewater problem is a difficult task. Several factors need to be considered, such as the data typology, the size and quantity of the data set, the number of features, the complexity of the problem, and the evaluation criteria and performance measures. Transferability of one model to other setting can be difficult as most AI methods are built on data for that particular context (process, location etc.) and would need comprehensive reworking to work in a new setting. Finally, the interpretability of some models can be difficult as some techniques, such as ANNs, can appear non-transparent, which might lead to false conclusions or wrong causalities. In conclusion, AI can pose a powerful tool to advance sustainable water management practices but remains a highly complex domain still under development.

3 Examples of implementation and use of AI in water-based systems

3.1 AI-based control of microalgae cultivation for water reuse

3.1.1 Introduction

The photosynthetic microorganism microalgae has gathered significant attention in recent decades as a promising source with various applications for producing biofuel, nutrient supplements, food, pharmaceuticals, and other high-value products [13]. The most advantageous characteristic of microalgae production is the possible usage of nonarable land fields, without threatening food security. Meanwhile, using CO2 as a carbon source during cultivation makes microalgae an important microorganism for a circular economy [14]. Microalgae cultivation requires a significant amount of water for culture medium with essential nutrients and other elements that support their growth. Traditional microalgae cultivation in open ponds leads to huge amounts of water loss through evaporation. In contrast, cultivation in a closed system with a photobioreactor is preferable for minimizing water loss and contamination and facilitating accurate control of the production process. The latter is considered in the present work.

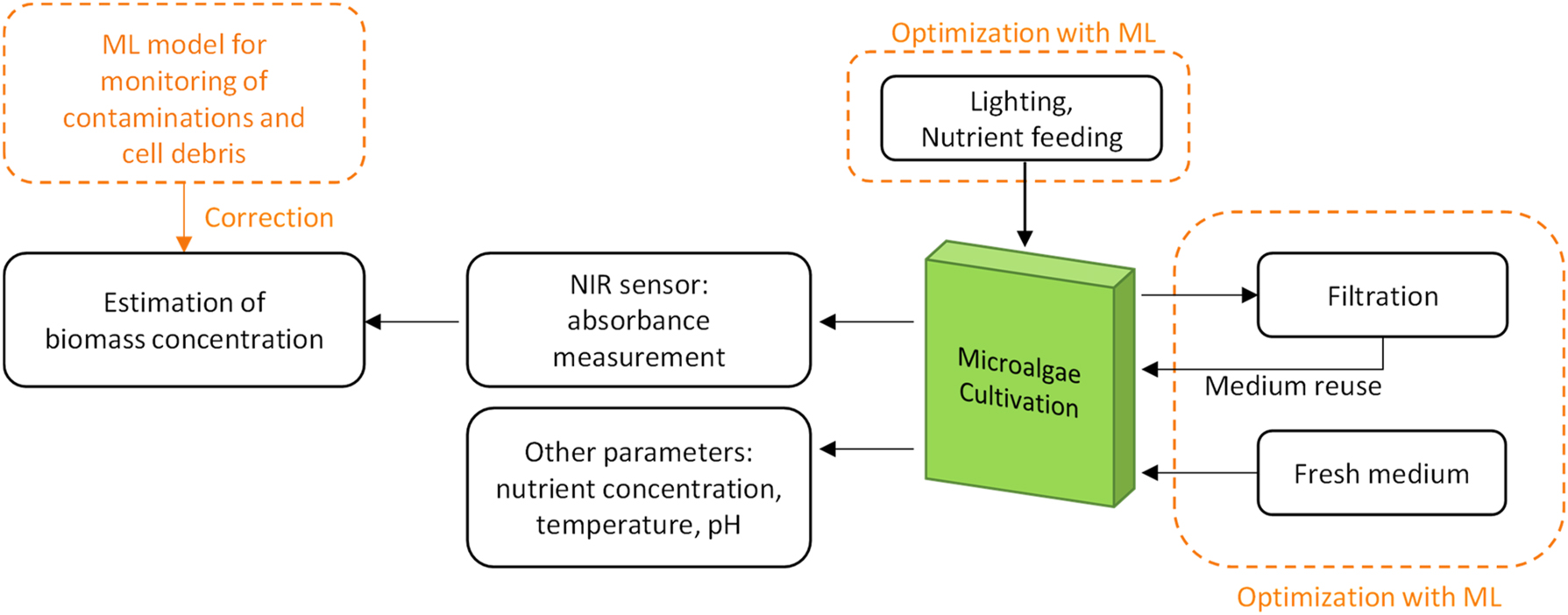

3.1.2 Implementation of a machine learning based method

The integration of machine-learning-based methods represents a promising possibility to improve the efficiency of water reuse in microalgae cultivation. To successfully implement machine-learning-based control strategies, various parameters must be considered. Biomass concentration, pH value, temperature, nutrient concentrations, cell debris, and contaminations are critical factors that must be carefully monitored. Among these parameters, biomass concentration is the most crucial one to monitor the growth condition of cultivation, which the NIR absorption sensor can estimate [15]. However, the accuracy of online biomass estimation will be affected by the existence of microalgal cell debris and contaminations of other microorganisms. Machine learning algorithms is used to estimate the amount of cell debris.

Understanding the growth mechanisms of microalgae regarding the aforementioned key parameters is essential for control strategies of medium reuse. Such a control system should take cultivation conditions in continuous or batch mode into account. Taking continuous cultivation as an example, the dilution rate yields the optimal growth should be decided, which depends on the amount of biomass to be harvested through continuous membrane filtration. Nutrient concentrations in the recycled medium should be monitored and used as key parameters to decide the dilution rate. In addition, the quality of the culture medium should be monitored to decide the reasonable time point to introduce fresh medium, because the quality of culture medium decreases over time through medium recycling. Here, the growth of microalgae regarding dilution rate with recycled medium and cultivation time is modeled using machine learning algorithms (Figure 4).

Example of use of ML methods for water reuse in microalgae production systems.

Our investigations show that microalgae growth can be modeled successfully (R 2 > 90 %) by using a long-short-term memory (LSTM) network [7]. The same framework can be extended to the growth modeling regarding medium recycling. Nutrient concentrations and the time-series data of medium quality should be included as additional input data to the existing LSTM model. By doing so, the LSTM should also be able to capture the growth mechanism considering varying nutrient concentrations and medium quality over the cultivation period. Afterward, the trained model can be used to determine the optimal dilution rate and total cultivation time through model predictive control. Because such machine learning models are purely data-based, they require a large amount of cultivation data with sufficient quality that contains needed variations of the parameters of interest. Moreover, the parameters to be used during cultivation with such a machine-learning-based control system should be within the range of the data available.

3.2 Detection of biofilm formation in cooling towers for predictive maintenance

Biological developments in water systems can affect a specific physical process negatively. Being able to detect changes in these systems can help to maintain these processes. AI can be applied to enhance the detection of biofilm formation in cooling towers through the analysis of various data sources. A biofilm is described as a thin layer of microorganisms that can accumulate and form a resistant film on surfaces in water systems, including cooling towers, and may lead to issues such as reduced heat exchange efficiency and increased energy consumption. Once biofilms are formed within a system, they are difficult to remove as classic treatments to remove microorganisms such as heat treatment, chemicals or physical application are not able to remove these biofilms. Being able to detect biofilm formation early can help in maintaining a clean system and prevent the reduction of heat exchange efficiency.

So far and with the improvement of large amounts of data acquisition, data processing and interpretation gives new insights especially in the topic of detection of biofilms. As said, detection of biofilm formation is detected whenever the heat exchange capacity is reduced. However, at this stage long downtimes are expected to clean the system. For that reason, an early detection mechanism including a variety of sensors coupled with AI may be able to detect formation early and thus apply countermeasures early to reduce downtimes. A variety of sensors may be able to collect data parameters that in summary are able to detect biofilms formation early. The measurement of nutrient levels in the water or on pipe surfaces can provide an indication of the potential for biofilm growth [16], [17] (Figure 5). Similarly, biofilms release metabolic by-products such as acids and enzymes that can be measured. Measuring flow rates and monitoring for areas of low flow or stagnation can help identify potential areas for biofilm growth [18]. Other indicator values that indicate biofilm formation are temperature and conductivity that play a role when coupling data with AI. Finally, and in order to be able to have a good feedback of biofilm formation all sensor need to be integrated in a way to continuously monitor and collect real time data. After preprocessing steps, such as baseline correction and noise reduction the data can be used in supervised learning models using historical data with labeled instances of biofilm presence or absence and how data parameters disagree.

![Figure 5:

Possible monitoring concept for the biofilm detection (source: [17]).](/document/doi/10.1515/auto-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_auto-2024-0023_fig_005.jpg)

Possible monitoring concept for the biofilm detection (source: [17]).

Besides a supervised learning model, the implementation of an unsupervised learning model can be used for the detection of anomalies to identify deviations from normal patterns. However, the risk of using unsupervised models is that the anomaly may not necessarily be introduced by biofilms formation but other factors. Using these kind of AI-based detection models may allow early detection of biofilm formation. Coupling this with an alarm warning system or automatic cleaning procedures in a control system can automate responses, such as adjusting chemical dosages or initiating cleaning processes. By combining various AI techniques, including supervised and unsupervised learning, and real-time monitoring, the detection of biofilm formation in cooling towers can be significantly improved. This proactive approach allows for timely intervention, reducing the impact of biofilm on cooling tower performance and enhancing overall system efficiency. However, it will be vital to understand which measurements are necessary for such a control system and will be part of future research.

4 Conclusion and outlook

It is well known that artificial-intelligence methods can be used to optimize, model, and automate water treatment systems successfully if sufficient qualitative data are available [2]. The main applications are: predictive maintenance, control optimization, real-time monitoring and fault-detection as well as decision support tools [5], [6]. Current research works show that the different processes involved in WWT plants can be modelled successfully using different supervised ML modelling approaches [2], [7], [11], [12]. However, implementing AI-based water treatment systems introduces several challenges that need to be addressed for the successful deployment and operation of these technologies. These challenges are mainly related to:

data availability and quality required for the development of accurate AI models,

simplified data structure/management to ensure an optimal communication between the different actors and

choice of an appropriate AI-methods depending on the data available and the system to be modelled [12].

Possible implementations of AI techniques for control optimization and predictive maintenance of water-based systems are discussed for two concrete examples in the field of water reuse for microalgae cultivation and predictive maintenance of cooling towers. The examples show that data availability (in quality and quantity) is crucial for the implementation. Here additional research is required to improve existing measurement technologies (hardware) and develop alternative ones (such as soft sensors) in order to provide additional online quality data [19].

Ongoing researches focus on the further development of the data structure and its implementation in different industrial water treatment plants. Future works will be focus on the development of hybrid models (using both AI and physical approaches) in order to decrease the amount of data required and allow a faster implementation.

About the authors

Antoine Dalibard studied “Mechanical Engineering” at the Technical University of Troyes (UTT) in France and graduated in 2004. He obtained a master degree in renewable energies and environmental management at the University of Barcelona in Spain (2006). Then he worked for more than 10 years at the Stuttgart University of Applied Sciences as researcher in the field of renewable energy systems for building application. Since 2018, he is working at Fraunhofer IGB in the department of water technologies as leader of the group physical and chemical separation processes with a special focus on model-based optimization of water treatment plants.

Lukas Kriem has been working since June 2020 as a scientist at Fraunhofer IGB. In 2014, he received his Bachelor’s degrees in Biology, Chemistry and Environmental Science from Drury University in Springfield, MO, USA. He then received his Master’s degree in Chemistry with a focus on environmental chemistry from Missouri State University in Springfield, MO, USA in 2017. In June 2017, he became part of Fraunhofer IGB as a PhD candidate at the University of Stuttgart in a Horizon2020 Marie Curie funded project and received his PhD degree in 2022. Since June 2023, he has also been Group Manager for Bioprocess Engineering and Microbiology. His focus areas are the use of Raman technologies for biological and chemical samples, the detection of microorganisms in liquid samples, biological characterization of surfaces and the characterization, avoidance and use of biofilms.

Marc Beckett studied “Biology” at the University of Bonn in Germany and graduated in 2012. He obtained a master degree in “Environmental Sciences” from the University of Freiburg in 2017. Since 2018 Marc Beckett is working for the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB in the area of sustainable water management approaches under the Water-Energy-Food Nexus framework. His work focusses on water reuse applications and the deployment of digital tools for the operation, management and monitoring of water reuse schemes.

Stephan Scherle studied physical engineering at the Ravensburg-Weingarten University of Applied Sciences. Since 2000, he has been developing measuring devices in the field of solar radiation measurement and soil respiration at the Karlsruhe Research Center, the Max Planck Institute and the Fraunhofer Institute. With the continuous improvement of measuring systems, the interface between the physical and digital world has become increasingly important for his work.

Yen-Cheng Yeh worked as young researcher at the University of Stuttgart between 2017 and 2022. Then he joined the “Algae Biotechnology” working group at Fraunhofer IGB where he has been developing models for the predictive control of large-scale algae cultivation in the “Algae Biotechnology”. In 2024, he completed his doctorate at the University of Stuttgart on the topic of “Improving optical measurements, online monitoring, growth modelling, and automated control in microalgae production of Phaeodactylum tricornutum”.

Ursula Schließmann studied process engineering at the University of Stuttgart. In 1995, the engineer joined Fraunhofer IGB, where she first developed new processes in the field of membrane and process technology, and then completed her doctorate on “Development of a Combination Process Based on Membrane Technology for the Treatment of a Fermentatively Produced Product” in 2009. She has continuously expanded the area of wastewater treatment and water purification. In 2011, she became Head of the Environmental and Bioprocess Engineering Department, and since 2019 she is the coordinator of the Environmental and Climate Protection area at the institute. After several years as a lecturer at the University of Stuttgart, she currently lectures at the University of Hohenheim on bioprocess engineering, environmental process engineering and bioeconomy.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

[1] S. Zhang, Y. Jin, W. Chen, J. Wang, Y. Wang, and H. Ren, “Artificial intelligence in wastewater treatment: a data-driven analysis of status and trends,” Chemosphere, vol. 336, 2023, Art. no. 139163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139163.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] M. Lowe, R. Qin, and X. Mao, “A review on machine learning, artificial intelligence, and smart technology in water treatment and monitoring,” Water, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1384, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14091384.Search in Google Scholar

[3] M. S. Zaghloul and G. Achari, “Application of machine learning techniques to model a full-scale wastewater treatment plant with biological nutrient removal,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 10, no. 3, 2022, Art. no. 107430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.107430.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Xylem, Wastewater Treatment Plant Uses AI to Reduce Aeration Energy Use by 30%. Available at: https://www.xylem.com/en-us/making-waves/water-utilities-news/ Accessed: Apr. 09, 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Y. Wang, et al.., “A review on applications of artificial intelligence in wastewater treatment,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 18, 2023, Art. no. 13557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813557.Search in Google Scholar

[6] G. Alam, I. Ihsanullah, M. Naushad, and M. Sillanpää, “Applications of artificial intelligence in water treatment for optimization and automation of adsorption processes: recent advances and prospects,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 427, 2022, Art. no. 130011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130011.Search in Google Scholar

[7] El A. El Fels, L. M. Abdelhafid, A. Kammoun, N. Ouazzani, O. Monga, and M. L. Hbid, “Artificial intelligence and wastewater treatment: a global scientific perspective through text mining,” Water, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 3487, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15193487.Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. Jain, et al.., “Overview and importance of data quality for machine learning tasks,” in Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, CA, USA, Virtual Event, 2020, pp. 3561–3562.10.1145/3394486.3406477Search in Google Scholar

[9] Y. K. Dwivedi, et al.., “Artificial Intelligence (AI): multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy,” Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 57, 2021, Art. no. 101994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

[10] C. Post, et al.., “Possibilities of real time monitoring of micropollutants in wastewater using laser-induced Raman & fluorescence spectroscopy (LIRFS) and artificial intelligence (AI),” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, p. 4668, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22134668.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] P. C. Nnaji, V. C. Anadebe, O. D. Onukwuli, C. C. Okoye, and C. J. Ude, “Multifactor optimization for treatment of textile wastewater using complex salt–Luffa cylindrica seed extract (CS-LCSE) as coagulant: response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial intelligence algorithm (ANN–ANFIS),” Chem. Pap., vol. 76, no. 4, pp. 2125–2144, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-021-01971-7.Search in Google Scholar

[12] S. Pandey, et al.., “Wastewater treatment with technical intervention inclination towards smart cities,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 18, 2022, Art. no. 11563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811563.Search in Google Scholar

[13] M. Rizwan, G. Mujtaba, S. A. Memon, K. Lee, and N. Rashid, “Exploring the potential of microalgae for new biotechnology applications and beyond: a review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 92, pp. 394–404, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.034.Search in Google Scholar

[14] A. G. Olabi, et al.., “Role of microalgae in achieving sustainable development goals and circular economy,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 854, 2023, Art. no. 158689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158689.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Y.-C. Yeh, B. Haasdonk, U. Schmid-Staiger, M. Stier, and G. E. M. Tovar, “A novel model extended from the Bouguer-Lambert-Beer law can describe the non-linear absorbance of potassium dichromate solutions and microalgae suspensions,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 11, 2023, Art. no. 1116735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1116735.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] S. J. Salgar-Chaparro, K. Lepkova, T. Pojtanabuntoeng, A. Darwin, and L. L. Machuca, “Nutrient level determines biofilm characteristics and subsequent impact on microbial corrosion and biocide effectiveness,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 86, no. 7, 2020, Art. no. e02885-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02885-19.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] A. Pereira and L. F. Melo, “Online biofilm monitoring is missing in technical systems: how to build stronger case-studies?” npj Clean Water, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-023-00249-7.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Y. Li, Y. Zhu, Y. Hao, P. Xiao, Z. Dong, and X. Li, “Practical reviews of exhaust systems operation in semiconductor industry,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 859, no. 1, 2021, Art. no. 12074. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/859/1/012074.Search in Google Scholar

[19] P. M. Ching, R. H. So, and T. Morck, “Advances in soft sensors for wastewater treatment plants: a systematic review,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 44, 2021, Art. no. 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102367.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Vorwort 2025

- Survey

- Information Circularity Assistance based on extreme data

- Methods

- Subjective task-load influences anthropomorphism during cooperative human and robot hand movements

- Applications

- Concept study of an autonomous aerial mobile network relay for pre-hospital emergency care

- Challenges and requirements of AI-based waste water treatment systems

- Modeling propagation competition between hostile influential groups using opinion dynamics

- Hesse-Matrix-basierte Qualitätsmanagementsysteme für die Fertigungsindustrie

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Vorwort 2025

- Survey

- Information Circularity Assistance based on extreme data

- Methods

- Subjective task-load influences anthropomorphism during cooperative human and robot hand movements

- Applications

- Concept study of an autonomous aerial mobile network relay for pre-hospital emergency care

- Challenges and requirements of AI-based waste water treatment systems

- Modeling propagation competition between hostile influential groups using opinion dynamics

- Hesse-Matrix-basierte Qualitätsmanagementsysteme für die Fertigungsindustrie