Abstract

This paper investigates the main features of the Genoese insurance market between 1564 and 1572, thanks to the analysis of an unpublished tax register that preserves all insurance policies drafted in Genoa in that period. Marine insurance, intended as an archetypical risk-shifting technique, is probably the oldest financial instrument intended solely to protect against the economic consequences of commercial losses. Conventional premium insurance was developed as a tool to transfer risk during the commercial revolution of the late middle ages. This development was first led by Italian cities, among whom Genoa played a key role. However, Genoese operators involved in the insurance sectors, which belonged almost exclusively to the patrician families ruling the republic, acted as a mutual “risk-community” in a semi-closed market: a sort of “syndicate”. They shared among them the risks of maritime routes calling at the port of Genoa. Insurance was a zero-sum game, with low losses and gains that did not allow a true single-sector specialisation.

1 Introduction

Marine insurance was long recognized as a crucial innovation in pre-modern commerce, allowing merchants and shipmasters to shift the voyage risks onto third parties. According to the New Institutional Economics school, insurance was a crucial development that influenced the European economic growth between the medieval and the early modern periods. Its development, however, was far from being a structured process (North 1990).[1] In the early, small, markets insurance could be a sort of zero-sum game: the maritime risk could be always shifted to the same operators. This is even truer when there is no clear distinction among business operators involved in the insurance and shipowning sectors, who could act both as insurers and insured. Such hybrid systems in Europe survived for a long time, as was the case for early modern Genoa (Iodice and Piccinno 2021a).

Genoa was the capital of a small oligarchic republic and an early example of an insurance and financial market, where local businessmen acted as a mutual “risk-community”: insurance allowed them to shift/share the maritime risk among them, thus spreading the extra costs of maritime trade. During the Late Renaissance, Genoa was one of the first markets specialized in securing maritime trade, together with Florence and Venice.

This paper uses a new dataset to investigate, from a qualitative and quantitative perspectives, the features of the Genoese insurance market between 1564 and 1572. We focus on the identity of the underwriters of the policies to examine whether they acted as a community – a “syndicate” – in a semi-closed market and the routes they used to insure risks. The dataset is the outcome of the digitisation of a policy book containing 757 maritime insurance policies drawn up in Genoa between February 1564 and March 1572.[2] The sixteenth century was a crucial moment in the history of insurance, since tools designed to tackle sea risks were still in their infancy.

Extensive research on insurance sources was conducted between the first and the second half of the twentieth century but it was in the last decades that scholars marginalized them. It was only in recent years and with new researches on networks, multidisciplinary interactions between risk-management tools and in-depth digitally-elaborated quantitative analysis they regained part of their old fashion. Ceccarelli (2020), for example, observed how the sixteenth-century Florentine insurance operators acted as if they were members of an informal small club, where trust relations and shared codes of conduct prevailed over the competition. In a world without probability, this was the mechanism utilised by a business community to manage the transformation of uncertainty into a calculable risk. In particular, he stressed the need to extend the historical analysis to overcome the idea that a business organization, in order to exist, must have a definite legal form, official recognition, and specific features (coercive authority, etc.). The outcome of this research is that a similar “informal” business organization existed in sixteenth-century Genoa, as well.

The Genoese Republic, to use an expression of Count Gorani (1740–1819), a Milanese writer and diplomat in the service of the Austrian monarchy, was “the most envied, the most denigrated and the least known” among all maritime republics (Assereto 1985). Studies on Venice, in contrast, are far more common. His observation reflects the poor circulation of the Genoese historical researches outside Italian academia. Nevertheless, the publications on the Republic of Genoa made by foreign scholars during the second half of the twentieth century partly reinvigorated the literature, as was the case with the comparison between Genoese and Maghribs traders in Greif (2006). Spooner (1956) referred to the “Age of the Genoese” when studying the history of the Republic between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and its relation with the Spanish monarchy. The same expression was later popularised by Braudel (1984).

The few studies on the Genoese insurance market in the Renaissance were published during the second half of the twentieth century. Melis (1975) and Giacchero (1984) focused on selected sources to highlight the functioning of early marine insurance and the Genoese peculiarities. Giacchero partially studied the sources employed in this paper, but his aim was to offer a brief survey on Genoese insurance policies and rules from the medieval to the early modern period. Tenenti (1978), on the other hand, used a small sample of Genoese sources in a quantitative way to build tables related to insurance prices on specific routes. He was interested in Genoese insurance sources considered as a proxy to evaluate the connections between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean maritime trade during the sixteenth century. Tenenti was among the first scholars to highlight the importance of comparing insurance sources, as he partially did between Genoese and Ragusan policies. He suggested potential lines of research that the wealth of Genoese sources should allow to follow: both Tenenti and Giacchero stressed out the necessity and the potential of further archival investigations. Finally, Piccinno (2016) recently considered the importance and the evolution of the Genoese insurance market from a qualitative and a procedural/legal point of view.

By readdressing the Genoese insurance market through an evaluative qualitative text analysis, we argue that local operators shared among them the risks of maritime routes calling at the port of Genoa, acting according to the collectivist model described by Greif (1994). In collectivist societies, each individual socially and economically interacts mainly with members of a specific religious, ethnic, or familial group in which contract enforcement is achieved through informal economic and social institutions. Members of collectivist societies feel involved in the lives of other members of their group. Greif, however, considered medieval Genoese traders as the archetype of individualist society: we believe that the distinction is not so clear-cut and different situations could co-exist. If for the Genoese traders one can correctly refer to an individualist society, for the early insurance market it is more correct to refer to a collectivist one. In the early insurance sector, the degree of insecurity was high, therefore the greater need for trust and sharing of losses within the community: without trust, ex-ante commitment required to sign an insurance policy would not have been possible. Partially sharing the risk among the operators involved is inevitable when insurance operates in a semi-closed market, as it was Genoa in the sixteenth century: probably this was the only feasible solution. Asymmetric information and the geographical boundaries of the courts’ jurisdictional power limited the ability of coercion-based institutions to enforce insurance contracts with oversea partners, shipmasters, or institutions.[3] It was only when the insurance industry became more speculative that the situation evolved to the individualist paradigm. For sixteenth- and, probably, seventeenth-century Genoa, insurance remained a collateral activity that did not bring significant immediate benefits. Yet, it was a socially necessary activity to distribute the unpredictable damages resulting from maritime trade, which was essential both because many Genoese were involved in it as merchants or shipowners, and because Genoa depended on the maritime sector for its survival.

2 Main Features of the Genoese Insurance Sector

Marine insurance first spread across Tyrrhenian coast cities in the late Middle Ages, and then to the rest of the Mediterranean, following a remarkable growth in the volume of trade and financial activities. As to marine insurance regulations, Genoa was one of the most active and innovative centres (Piergiovanni 2012a). The first insurance policy known to date was drawn up in Genoa by notary Tommaso Casanova, on 18 March 1343 (Giacchero 1984). The first Genoese marine insurance regulation dates back to 1369, following a decree by the Doge Gabriele Adorno (Piccinno 2016). On 5 March 1409 the republic’s administrators enacted a tax on insurance, the introitus unius pro centenario securitatum. The tax forced insurers and insured in Genoa to pay the Ufficio di Moneta magistracy a rate proportional to the sum insured and the premium collected. In 1416, its management was transferred to the Casa di San Giorgio (Gioffré 1966). San Giorgio was a semi-private institution made up of Genoese patricians to whom the Republic, administered by individuals belonging to the same patrician families, turned to when it needed capital. In return, the republic entrusted San Giorgio with the collection of specific taxes (Felloni 2006).

The insurance buyer and the underwriter paid the insurance tax equally. The tax was levied through brokers, who were required by law to report every insurance policy within eight days from its stipulation. The 1409 regulation does not seem to have undergone any reform, except for a rate increase in 1490.[4] In 1435, since insures and buyers avoided paying the tax by having their policies drafted through notarial deeds without a broker, severe sanctions were established; private individuals were allowed to sign the policy without a broker only on condition that they reported the contracts and referred all disputes to San Giorgio.

During the massive expansion of the European markets during the fifteenth century, marine insurance became increasingly regulated. Genoese rules probably followed those from the Consolat de Mar, issued between 1435 and 1484 (Addobbati 2016). Shipowners and merchants had a certain leeway in dealing with insurance policies, for example regarding which types of risks could be covered. The common practice of adding the ad florentinam clause indicated the maximum possible extent of the cover, which essentially included every possible risk, beyond the shipwreck or capture by enemies (Giacchero 1984). General Averages, which refers to the partition rate to be paid by each merchant in the case of a voluntary damage to minimise an imminent danger, was excluded, albeit until the enforcement of the Civil Statutes in 1589.[5] Other restrictions and limitations were removed over time: the one on the insurance of foreign vessels and cargoes was formally lifted in January 1408, while the one on insuring vessels bound beyond Gibraltar was removed in the 1420s.[6]

Standard policies usually reported significant information on the parties involved, the insured object and the related expenses, to allow easy identification. The policies specified also each underwriter’s name and the amount he accepted to cover, in golden ducati. A single policy could have multiple underwriters with different insured amounts. If there was a broker, he also signed the contract.

The members of Genoese aristocracy were among the most active insurance buyers and underwriters, along with a minority of other businessmen for whom insurance was an investment. Following the 1528 constitutional reforms, the republic was ruled by an oligarchy of patricians involved in all sectors of economic activities. Patricians were reunited in Alberghi that, according to Greif (1995), were “clan-like social structures whose purpose was to strengthen consorterial ties among members of various families through a formal contract and by assuming a common surname, usually that of the Albergo’s most powerful line”. Trade was concentrated, by and large, in the hands of the noble families belonging to different Alberghi. The same applied to the insurance sector, which is why it is possible to refer to it as a semi-close system. Frequent economic interactions among the same patricians probably strengthened existing ties, motivating them to interact further, socially as well as economically. These repeated interactions, which we observe in the policy book noted above, and the resulting social networks for information transmission could facilitate informal collective economic and social punishments for deviant behaviour (Greif 1994). Genoese patricians were involved in different business sectors, through which they managed to accumulate capital and become leading players in international finance, leading to the so-called Age of the Genoese. They acted not only as insurers, but also as merchants and shipowners. In the latter cases, they could buy insurance policies from the very same partners with whom usually they underwrote insurance policies.

Insurance contracts did not cover all journeys, nor all goods carried by sea. Insurance buyers decided whether to insure the entire cargo of a ship or only a part of it, in order to limit the premium costs and ensure the shipment’s profitability. Underwriters, on the other hand, decided whether to sign a policy or not after having carefully assessed transport risks depending on the type of cargo, its value, the vessel employed, the shipmaster, and the route. Scholars still debate the most influential factors relating to the determination of premiums.[7] A single element was often enough to determine a price variation. Operators needed a certain know-how and up-to-date information on the safety of the sea, and they also had to be knowledgeable about trade, routes, ports, ships and shipmasters: they had to be true risk experts (Ceccarelli 2020).

The source we analysed shed new light on the degree of expertise and the internal dynamics of the Genoese insurance market, while testing the trends that so far emerged from analyses of other pre-industrial insurance markets. As mentioned, Genoa boasted a traditional, reciprocal model of risk transfer/risk sharing where players often served simultaneously as underwriters and as buyers of insurance policies. The socio-professional background, the wide range of financial interests and the continuity of operations in the market, allowed Genoese operators to convert the maritime risk – the common threat – into a more or less stable percentage, the premium.

3 A Dataset Analysis: The Introitus Unius Pro Centenario Securitatum

The policy book employed for this analysis is kept in the San Giorgio fund of the Archivio di Stato di Genova (1564–1572).[8] It appears to be the only surviving one related to the introitus unius pro centenario securitatum. It covers the period between February 1564 and March 1572. It is also known as the Libro di carico della gabella sulle assicurazioni marittime. It was kept by Clemens de Nigrono [Di Negro] Navonus, a broker, and Petrus Vincentius Delfinus di Coniglia, his assistant. Clemens waited until he had a fair number of policies reported by brokers and insurers before proceeding with their transcriptions in the book. He operated with his partner Nicolaus Lomellinus [Lomellini]. Both the Di Negro and the Lomellini were among the leading families of the Genoese aristocracy.[9]

The book seems complete. The regularity of the transcriptions month by month corroborates this observation. Each policy is very detailed and contains the following: name of the buyer/s, name of the underwriter/s, goods insured, total insured amount in golden Ducati with each underwriter’s shares, premium in Genoese lire, tax due, and its settlement. Vernacular Latin was the language used.

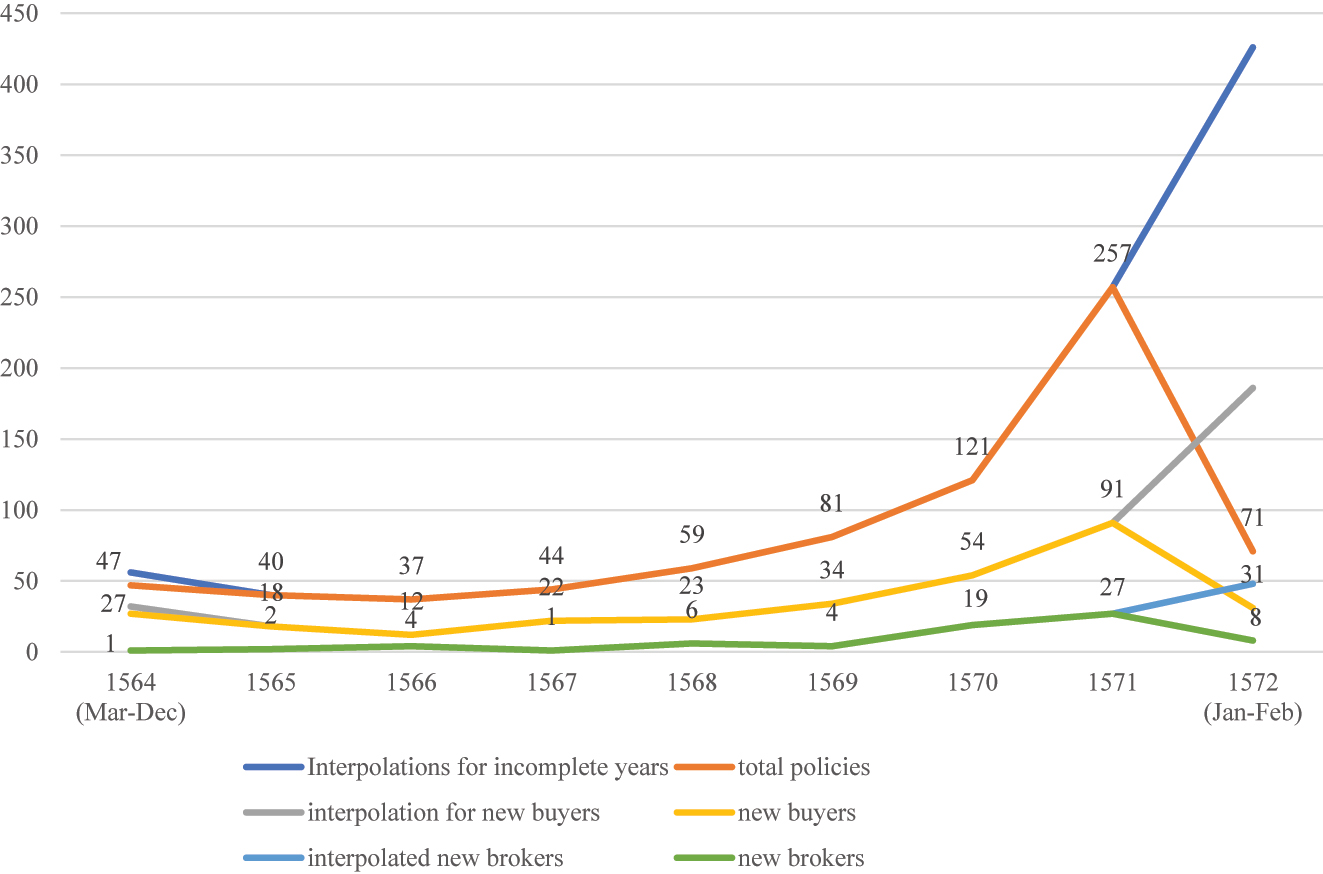

The total number of recorded policies is 757. Figure 1 shows how this number increased significantly over the examined period, from 40 recorded policies in 1565 to 257 in 1571. The interpolations of the missing months of 1564 and 1572 confirm the general trends. The positive orientation of the line is probably evidence of the intensification of trade and the growing penetration and commercial interchange in the Iberian market during this period (Pacini 2013). The carati maris tax in the same years, for example, which was usually contracted out by San Giorgio for about 260,000 lire per year, was contracted out for 412,075 lire in the period 1568–1572.[10]

Yearly total of policies, new buyers and new brokers 1564–1572. Source: author compilation based on Archivio di Stato di Genova (1564–1572).

The increase in the number of policies is similarly reflected in the increase in new policyholders – from 27 in 1564 to 91 in 1571 – and new brokers or commission buyers – from 1 in 1564 to 27 in 1571 – the functioning of which is explained in the next pages. Such increase could also be an evidence of the relative efficiency of the system. The positive trend lines, especially regarding the orange and dark blue lines for the new policies, could be determined by expanding trade networks, as well as by improved surveillance on those who avoided paying the insurance tax and, therefore, recording their policies in the book.

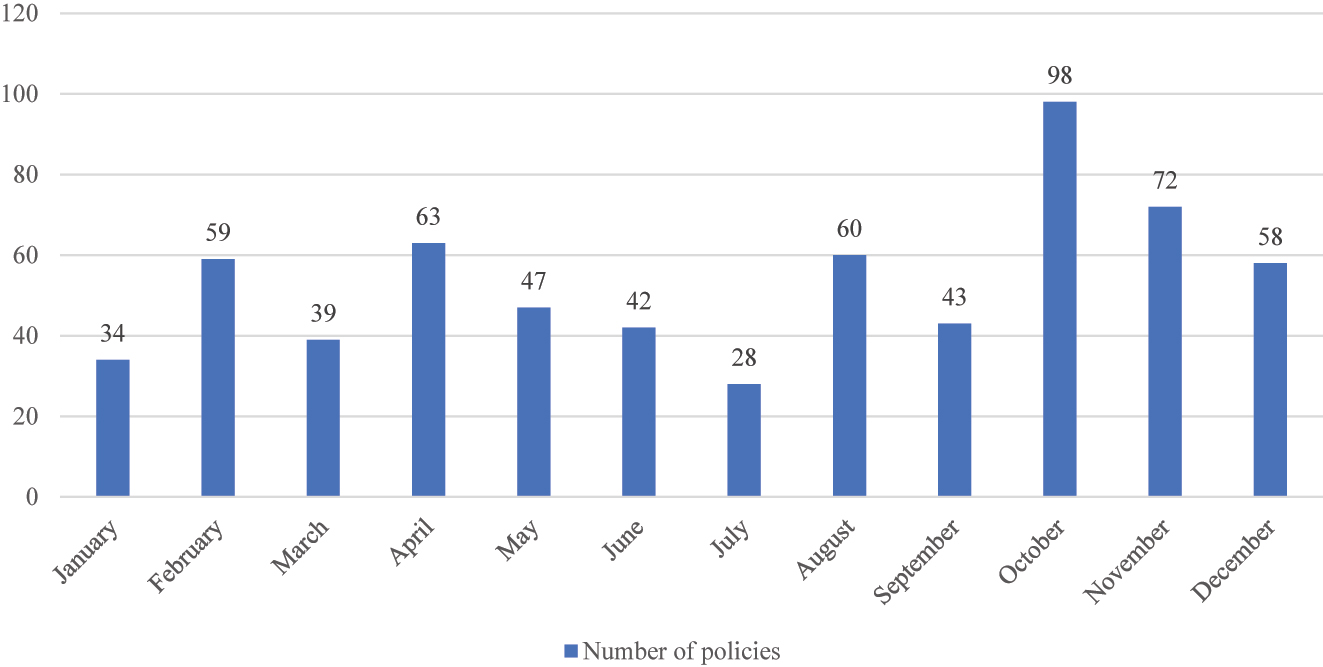

The Genoese businessmen involved in the insurance sector operated all year long, as results in Figure 2. Although there is a small peak in October (98 policies), this is probably due to the fact that many vessels with cargoes of wheat sailed in that period: the republic depended on the arrival of vessels loaded with wheat to ensure the necessary food supplies. In this sense, goods’ seasonality could influence the amount of insurance policies drafted per month, rather than climatic factors.

Number of policies drafted in Genoa per month, 1565–1571. Source: author compilation based on Archivio di Stato di Genova (1564–1572).

The routes to and from the port of Genoa formed the heart of the Republic’s economic system (Kirk 2005). Almost the entire manufacturing sector also depended on maritime trade for both the import of raw materials and the export of finished products. That is why it is not possible to observe a seasonality in the drafting of the policies, and why the patricians were so actively involved in a sector that usually did not provide great profits. Pooling of insurance underwriters among the patriciate aimed at protecting and fostering maritime trade, in which the same individuals were involved, more than to provide an immediate gain.

As emerges in Figure 3, operators engaged in the insurance market preferred to focus on traditional Mediterranean routes and products, specialising in neighbouring areas in close geographic proximity. In particular, it is possible to observe the strong links between Genoa and Sicilian or Spanish seaports. The Western Mediterranean area was the focus of Genoese trade: wheat arrived primarily from Sicily, while wool, salt, silver, and colonial goods arrived from Cadiz, Alicante, Cartagena, or the Balearic Islands.

![Figure 3:

Main maritime routes insured in Genoa, 1564–1572. Source: visualization of data in a digital map obtained through the database risky business [https://riskybusiness.labs.vu.nl/Map].](/document/doi/10.1515/apjri-2022-0037/asset/graphic/j_apjri-2022-0037_fig_003.jpg)

Main maritime routes insured in Genoa, 1564–1572. Source: visualization of data in a digital map obtained through the database risky business [https://riskybusiness.labs.vu.nl/Map].

The same preference for geographic proximity was common also in other sixteenth-century Italy insurance markets. Scott-Baker (2022), for example, reports how the Salviati bank in Florence, in 1586, refused to lend money to Giovanni Enriques, in Rome, to pay for an insurance cover on the Portuguese convoy sailing from southwest India to Lisbon. The request was an unusual one for the Florentine insurance market: they could not find anyone “who wants to run such a rischio, particularly in the manner proposed to us by your friend in Lisbon”.

In Genoa there were significant exceptions, such as the policies drawn up for the voyages from Lisbon to Royan (France), England, Flanders, Antwerp, Bruges, or the Spanish colonies in the New World. The Genoese patricians were risk specialists and repositories of considerable know-how. They could effectively gather information and exploit their business and family networks in the main nodes of the Genoese diaspora to operate simultaneously in several markets (Iodice and Piccinno 2021b). Members of the Genoese diaspora were spread across Europe and the European colonies, in particular in Spain, Portugal, and the Low Countries. In Seville, for example, out of approximately forty transatlantic insurance policies drafted in 1542, eight mention subscribers belonging to the following noble Genoese families: Spinola, Grillo, Lercari, Lomellini, Serra, Raggio, Salvago, Sopranis (Giacchero 1984).

Different kinds of goods were insured in the examined policy book: gold and silver, wheat, silk, coral, cochineal, and so on. Seventy-four policies do not mention the insured object, while two hundred and twenty-five contracts concern unspecified “goods” (mercibus). Sixty-six policies are insurances on wheat, including a cargo of wheat, gold and silver. Twenty-eight policies concern consignments of gold, nineteen of silk or wool cloths, seventeen of coral, and so on. Sixty policies are insurances on vessels.

There were two policies concerning slave cargoes. One policy insured the slaves on the Genoese ship of Paolo Spinola, which was supposed to sail from Seville to Cape Verde and San Juan de Ulúa (Mexico) in the autumn of 1569 (Archivio di Stato di Genova 1564–1572). Cristoforo Centurione bought an insurance on goods worth 4050 scudi at the rate of 8.25% and on nigres slaves for 4000 scudi at 5.75%. The other analogous case is the policy of Stefano Pinello, who in 1571 insured a cargo of mori slaves for 1500 scudi at a premium of 5.25% from Cape Verde to San Juan de Ulúa and Veracruz, on the ship of Francesco Hernandez (Archivio di Stato di Genova 1564–1572).[11] The Genoese probably preferred to operate in this sector from Spanish markets such as Seville.[12]

The techniques available to Genoese underwriters allowed them flexible risk management strategies. The subscription on commission was widespread and occurred in 148 policies out of 757 (19.55%). This phenomenon was common in sixteenth-century Italian insurance markets: an underwriter acted on behalf of someone else willing to provide insurance cover on a distant market, but being unable to do so in person. These policies are indicated in the book as follows: [commissioner’s name] in nomine [real underwriter’s name]. Commission resembled the buying and selling-on of quotas. It was, therefore, similar to reinsurance, another frequent practice in Genoese policies, along with co-insurance.

Co-insurance and reinsurance allowed underwriters to protect themselves from excessive exposure to risk. Reinsurance was widespread in Florence, for example, since the end of the fifteenth century (Del Treppo 1957; Melis 1975). It allowed the subscribers to resell their quotas for a higher premium: it was a speculative risk-transfer technique. In the sample of 757 policies examined, there are about 50 reinsurance policies (6.6%) (resecuratione), in which the re-insured asset is often not mentioned. For example, seventeen reinsurances were signed by a certain Paolo Uva, a common surname in Southern Italy, for routes touching exclusively Messina or Adriatic and Ionian seaports.[13]

Thirty out of 288 underwriters (10.4%) used co-insurance, a simple but valid solution to share the risks of navigation. They operated together with close relatives or business partners. It is common to find one or both partners also acting as individual underwriters in other policies. Perhaps they agreed on partnerships in the case of routes perceived as particularly risky, or simply to better cope with the eventual claim to be paid. No clear patterns emerge from the sources examined.

Single quotas, initially bought by one insurer, could also subsequently be subdivided among more individuals, so that the risk was spread more widely through informal agreements. This was frequent in other marketplaces as Florence (Ceccarelli 2020). Such custom emerges only when looking at the bank accounts of each individual underwriter, when the payments of premiums were registered. Since dividing quotas between underwriters seemed very common in Genoa, it was even recorded in tax sources, it can be assumed that there was a scarce need for such informal practice.

The range of available mechanisms to ease the management of risk, as well as the possibility to adapt them to one’s needs, increased the efficiency of the Genoese insurance market. Underwriters bought risk as a commodity, as they would do when dealing with financial speculation and investments, to secure maritime trade. This pattern is corroborated by the almost total absence of policies signed by a single underwriter. Large groups of Genoese underwriters insured even the most common routes, such as the Messina–Livorno, although more individuals were involved in underwriting policies involving Atlantic or eastern Mediterranean seaports.

As already mentioned, 288 underwriters signed policies individually or in societies. The insurance business was run in almost total monopoly by the Genoese patriciate. The names of various members of the Spinola, Doria and Lomellini families, in particular, appear the most frequently. Gaspar Suares, present in 2 policies, seems to be the only foreigner. He maybe was a relative of Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, ambassador of Emperor Charles V in Genoa from 1529 to 1549.[14] Some of the patricians probably resided abroad, such as Gian Battista Fieschi raguseus (from Dubrovnik), while other names belonged to well-known members of the Genoese financial élite, such as Adamo Centurione. He was a well-known merchant and one of the main financiers of the Habsburg Crown. According to Giacchero, the Genoese aristocracy operating in the insurance business acted in such a cohesive way as to resemble an informal insurance company:

In Genoa, insurance companies either do not emerge or have an ephemeral life: on the other hand, in cases of risk-taking on average and significant amounts, a compact aggregate of insurers from the major families is grouped together, which for years, without interference from outsiders, helps to bring business to fruition: and the practice is so consistent, in terms of names and timing, as to make it reasonable to assume that these are not casual encounters but a concerted agreement within the framework of a real de facto society.[15]

The Genoese businessmen were indiscriminately and consistently involved in the management of maritime risk through insurance. The members of the patrician Pinelli family, whose continuous involvement in insurance made them almost a dynasty of risk experts, constitute a significative example. The shipmaster Valentino Pinelli was involved in the first known insurance policy of 1343, mentioned above. The names of Michele, Paolo, and Stefano, are among the underwriters recorded in the policy book we examined. On the buyers’ side, we find Giovanni Francesco son of Francesco, Alessandro, his son Agostino, and Stefano again. Stefano Pinelli also acted in partnership with Filippo Spinola as both insurer and insured. His name was even mentioned by the jurist Stracca (1622), author of a treatise on commercial law collecting exemplary judgments of the Genoese Rota Civile.[16]

Although some underwriters invested more money than others, they all seem to refrain from being the first to underwrite a policy. A remarkable peculiarity of the Genoese insurance market is the almost complete lack of leading insurers. The latter is the name scholars give to those underwriters that most frequently accepted to sign a new policy when it was placed on the market.[17] They were credited by all the other actors in the sector with great experience and superior access to information. Both the buyers and the brokers tried to obtain their opening signature, since this assisted them to place the remaining quotas more easily. The credibility supplied by the leading insurers who were well-known operators could persuade infrequent underwriters to follow. No such figure emerges from the names of underwriters who were the first to sign policies in Genoa. The only recurrent names (from 2 to 6 times) are of those who were generically more active in the sector, therefore they were statistically more likely to appear more in the first position. On average, each underwriter was a leading insurer in 1.2 policies. Four hundred and ninety-nine policies feature a different underwriter each time: the median is 1.

Other strategies emerge when focusing on the activity of a single underwriter. That of Antonio Spinola son of Tommaso is a classic application of a follower strategy, someone who agrees to sign a policy only following someone who played the role of the leading insurer. He was involved as an underwriter in 283 policies, about 37% of the total. He insured goods to the value of 140,135 ducati, in quotas whose median is 300 ducati. His premiums’ median, from which he collected 7612.5 ducati, was 5.25%. Despite his remarkable role in absolute terms, he almost never subscribed a policy as the leading underwriter. Only in 6 of them, he appears as a leading insurer. He did not seem to prefer one route over another: he underwrote policies related to Tyrrhenian, Eastern or Western Mediterranean routes, and also from Northern Europe, as well as on routes not touching Genoa at all. In almost every policy he participated with the largest quota, or at least at the same rate as the main underwriter/s. Sometimes he underwrote a policy in exchange for a premium surcharge. The increase was recorded in the policy, as was the case of the premium increase from 5.25% to 6.25% in 1568 for the insurance on a cargo from Livorno to Alicante, or from 4% to 5% in 1570 on a ship bound for Genoa (Archivio di Stato di Genova 1564–1572). Rarely, he also underwrote twice the same policy. For example, in the insurance on goods on a galleon sailing from Lisbon to Livorno signed in 1567, he appears as both a leading insurer and follower, with two 300 ducati quotas (Archivio di Stato di Genova 1564–1572). Perhaps the high premium (10.25%) and the need to find operators willing to cover an insured amount of 4400 ducati led him and 24 other patricians to share this maritime risk. When investing large sums of capital, over 1000 ducati, the names of Cristoforo Centurione or Angelo Lomellini were often mentioned among the other underwriters. This led us to assume the presence of an inner circle of major underwriters who underwrote together specific policies. Further studies on their account books and letters would allow us to verify such theory.

4 Conclusion

The analysis of the policy book highlighted how Genoese underwriters acted as a group of “risk experts”, although with varying intensity depending on the insurer. The group’s cohesion derived from family connections, business ties, political ties, or from a combination of motives. The collectivist economic organization probably was the only successful option in a sector marked by such an high degree of uncertainty. They formed a sort of informal partnership firm, capable of distributing insurance cover among dozens of investors. Once a collectivist structure is adopted, it influences the rules of historically subsequent games and hence the resulting societal organization. The insurance sector’s structure adopted in Genoa in this period could be one of the reasons behind the late implementation of insurance companies in Genoa, in comparison to those that spurred in France and England in the early modern period. However, Genoa remained a relevant insurance centre in Europe, which relied on individual insurers and short-time partnerships.

When perusing the lists of underwriters transcribed in the policy book, it is remarkable to note how some names tend to appear in succession, one after the other, almost testifying to a common strategy, deliberate and agreed upon. Even when the number of Genoese active in insurance rose during the examined period, the “rules of the game” did not change. It is almost as if there was a “syndicate” compiled by co-insurers who operated in variable ways and forms, but which were probably based on definite, albeit not formalised, agreements.

Underwriters profited from updated information, business expertise, and their often longstanding and dynastic involvement in the insurance sector. These factors allowed them to make predictions through unconscious inferences to obtain an essential sharing/transferring of risk, that contributed to reduce transaction costs compared to insurance prices in other markets and to foster international maritime trade. When looking at all policies, some geographical specialisation can be inferred, but individuals did not seem to favour one route over another. Likewise, no operator seemed to prefer the risky role of leading insurer. They alternated almost systematically in opening policies. This factor further reinforces the impression of a risk community that preferred to split losses and gains in a semi-closed market structure. This also emerges from other studies (Iodice and Piccinno 2021a) which have shown how the activity of Genoese insurers between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was a zero-sum game that did not allow a true single-sector specialisation.

-

Data availability statement: The research data supporting this publication are openly available from the Open Access database Risky Business, hosted by the University of Amsterdam (VU) at: https://riskybusiness.labs.vu.nl/.

References

Primary Sources

Archivio di Stato di Genova, S. G. 1564–1572. Imposte e Tasse, unit 33110.Search in Google Scholar

Archivio di Stato di Genova, S. G. 1335–1648. Libro dei regolamenti di varie gabelle, unit 24065.Search in Google Scholar

Secondary Sources

Addobbati, A. 2016. “Italy 1500–1800: Cooperation and Competition.” In Marine Insurance. Origins and Institutions, 1300–1850, edited by A. Leonard, 46–77. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Assereto, G. 1985. “Dall’amministrazione patrizia all’amministrazione moderna: Genova.” In L’amministrazione nella storia moderna, Vol. I, 95–159. Milan: Giuffré.Search in Google Scholar

Berti, M. 1973. “Alcuni momenti salienti dell’evoluzione nel sistema dei trasporti marittimi nel Mediterraneo dal Medioevo all’età moderna.” In La penisola italiana e il mare. Costruzioni navali, trasporti e commerci, edited by T. Fanfani, 71–88. Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane.Search in Google Scholar

Boiteux, L. A. 1968. L’assurance maritime à Paris sour le régne de Louis XIV. Paris: Roche D’Estrez.Search in Google Scholar

Braudel, F. 1984. Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century, III, The Perspective of the World. London: William Collins Sons & Co.Search in Google Scholar

Brilli, C. 2016. Genoese Trade and Migration in the Spanish Atlantic, 1700–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ceccarelli, G. 2020. Risky Markets: Marine Insurance in Renaissance Florence. Leiden: Brill.Search in Google Scholar

De Lara, Y. G. 2008. “The Secret of Venetian Success: A Public-Order, Reputation-Based Institution.” European Review of Economic History 12: 247–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1361491608002281.Search in Google Scholar

Del Treppo, M. 1957. “Assicurazioni e commercio internazionale a Barcellona nel 1428–1429.” Rivista Storica Italiana 69: 508–41.Search in Google Scholar

Felloni, G., ed. 2006. La Casa di San Giorgio: il potere del credito. Genoa: Società Ligure di Storia Patria.Search in Google Scholar

Fusaro, M., A. Addobbati, and L. Piccinno, eds. 2023. Sharing risk: General Average and European Maritime Business (VI–XVIII Centuries). London: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

García-Montón, A. 2022. Genoese Entrepreneurship and the Asiento Slave Trade, 1650–1700. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Giacchero, G. 1984. Storia delle assicurazioni marittime. L’esperienza genovese dal Medioevo all’età contemporanea. Genoa: SAGEP.Search in Google Scholar

Gioffré, D. 1966. “Il debito pubblico genovese. Inventario delle compere antreriori a San Giorgio o non consolidate nel banco (sec. XIV–XIX).” In Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, VI (LXXX).Search in Google Scholar

Greif, A. 1994. “Cultural Beliefs and the Organization of Society: A Historical and Theoretical Reflection on Collectivist and Individualist Societies.” Journal of Political Economy 102/5: 912–50. https://doi.org/10.1086/261959.Search in Google Scholar

Greif, A. 1995. “Political Organizations, Social Structure, and Institutional Success: Reflections From Genoa and Venice During the Commercial Revolution.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 151/4: 734–40.Search in Google Scholar

Greif, A. 2006. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Iodice, A., and L. Piccinno. 2021a. “Shifting and Sharing Risk: Average and Insurance between Law and Practice.” In Maritime Risk Management. Essays on the History of Marine Insurance, General Average and Sea Loan, edited by P. Hellwege, and G. Rossi, 83–110. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.Search in Google Scholar

Iodice, A., and L. Piccinno. 2021b. “Whatever the Cost. Grain Trade and the Genoese Dominating Minority in Sicily and Tabarka.” In Business History, Special Issue Paper in Minorities and Grain Trade in Early Modern Europe, 1–19.Search in Google Scholar

Kingston, C. 2007. “Marine Insurance in Britain and America, 1720–1844: A Comparative Institutional Analysis.” The Journal of Economic History 67: 379–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050707000149.Search in Google Scholar

Kirk, T. A. 2005. Genoa and the Sea. Policy and Power in an Early Modern Maritime Republic, 1559–684. Baltimore: Baltimore University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Melis, F. 1975. Origini e sviluppi delle assicurazioni in Italia (secoli XIV–XVI), I, Le Fonti. Rome: Istituto Nazionale delle Assicurazioni.Search in Google Scholar

North, D. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pacini, A. 2013. Desde Rosas a Gaeta. La costruzione della rotta spagnola nel Mediterraneo occidentale nel secolo XVI. Milan: Franco Angeli.Search in Google Scholar

Piccinno, L. 2016. “Genoa 1340–1620: Early Development of Marine Insurance.” In Marine Insurance. Origins and Institutions, 1300–1850, edited by A. Leonard, 25–46. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Piergiovanni, V. 2012a. “Assicurazione e finzione.” In Norme, scienza e pratica giuridica tra Genova e l’Occidente medievale e moderno, Vol. II, edited by V. Piergiovanni, 1167–71. Genoa: Società Ligure di Storia Patria.Search in Google Scholar

Piergiovanni, V. 2012b. “The Rise of the Genoese Civil Rota in the XVIth Century: The ‘Decisiones de Mercatura’ Concerning Insurance.” In Norme, scienza e pratica giuridica tra Genova e l’Occidente medievale e moderno, Vol. II, edited by V. Piergiovanni, 915–32. Genoa: Società Ligure di Storia Patria.Search in Google Scholar

Scott-Baker, N. 2022. In Fortune’s Theatre. Financial Risk and the Future in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Spooner, F. C. 1956. L’Economìe Mondiale et les Frappes Monétaires en France, 1493–680. Paris: éditions EHESS.Search in Google Scholar

Spooner, F. C. 1983. Risks at Sea: Amsterdam Insurance and Maritime Europe, 1766–1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Stracca, B. 1622. De mercatura decisiones et tractatus varii. Cologne: Cornelius Egemont de Grassis.Search in Google Scholar

Tenenti, A. 1978. “Assicurazioni genovesi tra Atlantico e Mediterraneo nel decennio 1564–1572.” In Wirtschaftskräfte in der europäischen Expansion, Vol. II, edited by J. Schneider, 9–36. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Harold D. Skipper Award-winning Paper of the 2022 Asia-Pacific Risk and Insurance Association Conference in Shanghai, China

- The Impact of Product-Dependent Policyholder Risk Sensitivities in Life Insurance: Insights from Experiments and Model-Based Simulation Analyses

- 2022 Insurance History Conference in Basel, Switzerland

- Special Issue: History of Insurance in a Global Perspective: A Novel Research Agenda

- Economic and Environmental Conditions for the Diffusion of Insurance in Three Non-Euro-American Regions During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- Marine Insurance in Early Modern Genoa (1564–1571): A Risk-Shifting or Risk-Sharing Tool?

- Who Do You Trust? Trust and Insurance Through Africa’s Past and Future

- The Risk of Natural Catastrophe in Early America: Perspectives from the Phoenix Assurance Company London and Nascent US Insurers

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Harold D. Skipper Award-winning Paper of the 2022 Asia-Pacific Risk and Insurance Association Conference in Shanghai, China

- The Impact of Product-Dependent Policyholder Risk Sensitivities in Life Insurance: Insights from Experiments and Model-Based Simulation Analyses

- 2022 Insurance History Conference in Basel, Switzerland

- Special Issue: History of Insurance in a Global Perspective: A Novel Research Agenda

- Economic and Environmental Conditions for the Diffusion of Insurance in Three Non-Euro-American Regions During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- Marine Insurance in Early Modern Genoa (1564–1571): A Risk-Shifting or Risk-Sharing Tool?

- Who Do You Trust? Trust and Insurance Through Africa’s Past and Future

- The Risk of Natural Catastrophe in Early America: Perspectives from the Phoenix Assurance Company London and Nascent US Insurers