Abstract

This study explores the decision-making behaviour of economic actors in relation to transfer pricing by applying a three-layer practice theory. A critical review of the literature using snowball sampling and a thematic analysis of interview data from the Ministry of Finance, tax consultants and the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority bring to light novel conceptualisations and perspectives on the transfer pricing phenomenon. This study addresses scholarly gaps by exploring a confluence of legal, implementation and exploitative dimensions in transfer pricing regulation. The study also makes a novel contribution by proposing a model that could be useful to policymakers and tax authorities in ameliorating tax avoidance through transfer pricing.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Related Literature

Aspects of Transfer Pricing (TP) as a Rational Decision

Dimensions of TP Regulation

Conceptual Framework

Methodology

Literature Review Methodology

Literature Search and Selection

Inclusion and Exclusion Decisions

Data Collection through Interviews

Findings

Analysis and Discussion of Results

Behaviour of MNEs towards TP

How Tax Authorities React to the TP Practices of MNEs

The Adequacy of TP Rules and Resources to Implement the TP Laws and Regulations and Curb Tax Avoidance

Conclusion, Limitations, and Recommendations

Strengthen the Legislative Framework

Instil Cooperation and a Relationship Based on Mutual Trust, Transparency, and Respect

Allocation of Adequate Resources for the Tax Authorities to Execute Their Mandates

Increase Transparency and Accountability of Public Officials

Intensive Scrutiny of MNEs

Regulation of Tax Practitioners

Design Regional/Nation-Specific TP Guidelines

References

Tax Enforcement

Tax Enforcement and Dispute Resolution: National and International Challenges

Conceptualising the Behaviour of MNEs, Tax Authorities and Tax Consultants in Respect of Transfer Pricing Practices – A Three-Layer Analysis, by Eukeria Wealth, Sharon A. Smulders and Favourate Y. Mpofu, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2022-0036.

Will Proclaimed Changes to Multinationals’ Taxation Have an Actual Effect and What Will Really Change for Africa?, by Andrea Musselli, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2024-0010.

Collection of Taxes from Ultimate Beneficiaries: Russian Regulatory Model, by Imeda Tsindeliani, Maria Egorova, Evgeniya Vasilyeva, Inessa Bit-Shabo and Vitaly Kikavets, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2020-0149.

Transfer Pricing Audit Challenges and Dispute Resolution Effectiveness in Developing Countries with Specific Focus on Zimbabwe, by Favourate Yelesedzani Sebele-Mpofu, Eukeria Mashiri and Patrick Korera, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2021-0026.

International Tax Avoidance and the Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rule

Legal Form or Unfair Substance? A Symposium Around the Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rule, by Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Yuri Biondi, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2024-0105.

The Relationship between Taxation, Accounting and Legal Forms, by Thomas Kollruss, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2019-0076.

Why Tax Planning Without Considering Societal Interests is Unfounded, by Ute Schmiel, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2021-0115.

The (Social) Tasks of Business Tax Research and the Binding Effect of the Statutory Tax Burden Decision, by Thomas Kollruss, https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2022-0089.

1 Introduction

Transfer pricing (TP) has gained prominence with the advent of globalisation as multinational enterprises’ (MNEs) activities transcend borders (Asongu et al., 2019; Kabala & Ndulo, 2018). MNEs have been at the centre of a heated debate regarding whether their existence is beneficial or harmful to developing economies. This is because of the conflicting roles of the TP phenomenon, which includes accounting for intercompany transactions, appraisal of divisional management, minimising tax and maximising shareholder value (Bradley, 2015; Ekstrom et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2014). While TP is a legitimate accounting practice (Asongu, 2016; Asongu et al., 2019), there is a general consensus in the literature that MNEs have an incentive to manipulate it for purposes of minimising their tax liabilities and achieving higher group profits (Bhat, 2009). Therefore, TP becomes an important strategic governance decision in promoting the organisational (MNE) goals. For MNEs to achieve profit maximisation, MNEs may need to reduce their costs. This may include employing TP strategies such as mis-invoicing, use of tax havens and profit shifting, which are associated with aggressive tax avoidance, a behaviour which contradicts sustainability goals (Biondi, 2017; Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021a). Quiggin (2005) stresses that the aim of globalisation was to prevent third-world poverty and debt from happening, but with MNEs being monopoly providers of investment and employment and negotiating generous tax concessions; globalisation has widened the gap between the rich and the poor. Kotz (2000) added that neo-liberalism magnifies class conflicts, which can discourage capitalist investment. This leaves governments in a catch-22 situation regarding which path to take between promoting investment and maximising their tax base for the betterment of social welfare. While Kotz (2000) hints that globalisation creates difficulties for individual states to independently regulate business across their borders, he emphasises that the major limiting factor is the political will rather than the technical feasibility of doing so.

The African states have been identified as the main victims of the TP phenomenon as MNEs are mainly created and domiciled in developed countries and this is where they shift their profits to (Dharmapala & Riedel, 2012). This practice disadvantages developing countries by transferring income away from where the value was created and this undermines the developing countries’ ability to mobilise domestic revenue and finance sustainable development (Bhumika, 2018). This scourge is felt severely in Sub-Sahara Africa where more than US$60 billion per year is lost due to MNE transfer mispricing activities (Curtis & O’Hare, 2017; UNCTAD, 2020). Linder (2019) expounds that this amount exceeds the foreign aid that the region receives annually and poses structural obstacles to the economic growth of Sub-Saharan Africa. Literature confirms the limited ability of African states to deal with this complex phenomenon (Dharmapala & Riedel, 2012; Oguttu, 2016, 2017; Shongwe, 2019). This is compounded by the enigmatic nature of TP and its complexity for both tax authorities and MNEs (Cazacu, 2017; Maya, 2015). Cazacu (2017) elucidates that the TP phenomenon is subject to contradictory views and complicated by the heterogeneity of tax jurisdictions and their economic environments. These variations may result in the double taxation of MNEs or under-taxation which explains why MNEs and tax authorities’ interests are diametric as MNEs’ TP decisions are predominantly tax-motivated (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021a) while tax authorities seek to protect their tax base.

Li (2006) asserts that with or without double taxation treaties, unharmonised TP systems hinder the successful elimination of double taxation and income shifting. These un-harmonised systems validate the tax authorities continued increased scrutiny of MNEs (Tully, 2012) while the MNEs remain susceptible to double taxation, and are therefore motivated to search for more complex TP schemes and tax avoidance strategies (Sikka & Haslam, 2007). To counteract these “creative compliance” stances (Sikka & Willmott, 2010) by taxpayers, governments often revise their legislation in an attempt to reduce or eliminate this behaviour and its repercussions. Other ways of achieving this goal include introducing significant penalties, new documentation requirements, and increased audit procedures (Holtzman & Nagel, 2014). The appropriateness and comprehensiveness of the TP legislation should be considered in the light of the sophistication and “creative non-compliance” schemes employed by taxpayers in each specific country (McBarnet, 2001). This leads to an adversarial approach as opposed to collaborative and productive synergies, as energies get displaced into mutually exclusive behaviours that undermine cohesive co-determination models of growth and social good (McIntosh & Buckley, 2015). This diametric relationship between tax authorities and taxpayers (MNEs) becomes a vicious cycle that ultimately impedes foreign investment and consequently causes unintended revenue losses. Revenue losses in turn affect livelihoods and other socio-economic conditions of citizens of all affected countries (Sikka & Willmott, 2010).

For decades, Zimbabwe’s economic growth has been stifled, and identifying the causes and remedies to boost its economic growth would be crucial, especially considering that the Zimbabwean government introduced TP legislation and rules in 2016. It is evident from the Income Tax Act (Chapter 23: 06) that Zimbabwe moved from anti-avoidance rules to specific TP rules. What was the rationale of legislators to move from general anti-avoidance rules to specific TP rules? The reason points to the need to improve the effectiveness of TP regulation in mitigating tax avoidance by MNEs (Mashiri, 2018).

In light of the above, this study seeks to explore the behaviour of economic actors concerning their TP decisions by applying the rationality theory. This is a novel contribution to the literature as the application of the rationality theory has not been applied to TP before. Rationality theory involves selecting an option among various available options that is favourable to oneself (Levin & Milgrom, 2004). In the context of TP, economic actors include the tax authority, tax consultants, and taxpayers, which in this case are the MNEs. The central question is how do the economic actors behave in relation to the application of the TP legislation and the regulation thereof? Tracy (2013) concedes that the social phenomenon (TP) is created from the rational economic decisions and consequent actions of the ‘economic actors’. This study thus focuses on exploring and understanding the decision-making behaviour in respect of TP of three ‘economic actors’, the MNEs, government (Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA) and the Ministry of Finance (MOF)), and tax consultants by applying the rationality theory.

The theoretical concept of rationality is examined both through literature as well as by reviewing the qualitative views of the economic actors on TP, making this study distinctive in terms of a more novel confluence of the method, theory, and context. Not only is the application of the rationality theory to TP a theoretical contribution, but its stratification into three dimensions of administrative, implementation, and legal rationality draws upon the seminal work by Weber (1968). This paper aims to rationalise how the economic actors (government, MNEs, and tax consultants) behave towards the application of TP legislation and its regulation. This would inform effective policy construction towards minimising tax avoidance and Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) by MNEs through manipulative TP practices. From the perspective of the rationality theory, the conflicting behaviour of the various economic actors involved in TP is sought to be understood by obtaining answers to the following questions:

What is the behaviour of MNEs towards TP?

How do the tax authorities react to the TP practices of MNEs?

How adequate are the TP laws and regulations to curb tax avoidance?

What model can tax authorities use to combat TP practices that lead to tax avoidance and BEPS by MNEs?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 contains the literature review which first explains aspects of TP as a Rational Decision (Subsection 2.1) and then expounds on the various dimensions of TP regulation in subsection 2.2. Subsection 2.3 provides the conceptual framework for the study and section 3 explains the methodology applied in the study while Section 4 highlights the findings of the study. The paper ends with Section 5, which concludes with the findings, outlines the limitations of the study and provides recommendations for future research.

2 Related Literature

TP is a legitimate accounting practice (Asongu et al., 2019; Asongu & Nwachukwu, 2016) but literature shows that it is being used as a tax avoidance tool by MNEs (Mashiri, 2018; Oguttu, 2020). The rationality theory, referred to by Weber (1968) as formal rationality, is employed as the theory to solve the TP puzzle. Weber (1968) describes formal rationality as decision-making that applies calculative practices without regard for human values. He stresses that it is institutionalised in bureaucratic structures and capitalist ideologies where profits are the focus. This reasoning unravels the possible behaviour of taxpayers juxtaposed with that of the tax authorities. Uyanik (2010) describes the visions of tax authorities and MNEs as diametrical opposites as tax authorities strive to maximise revenue mobilisation, and taxpayers focus on minimising their tax liability as much as possible. However, the effectiveness of tax authorities may be moderated by corruption or political interference (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021a) and the antagonistic tendencies of tax consultants (Mashiri et al. 2021). Scott (2000) adds that taxpayers as economic actors will engage in deliberate calculative strategies that give them minimum tax payments while the legislators together with the tax authority will calculate measures that will effectively draw maximum tax receipts from taxpayers. Hai and See (2011) who described taxpayers as economic tax-evaders who will always make decisions based on weighing the gain of successful non-compliance against the risk of being caught supported this.

Rationality involves being calculative, and the rationality theory assumes taxpayers and tax authorities are rational players who seek to maximise their group profits by minimising their tax liability and by maximising their tax base respectively (Sikka & Willmott, 2010). The same authors indicated that people within organisations make rational economic decisions to exploit many opportunities to ensure their after-tax global income is maximised. Rational economic decisions are therefore not value-free despite the inherent logic but are also exploitative and self-serving.

2.1 Aspects of Transfer Pricing (TP) as a Rational Decision

TP as a rational decision entails how economic groups such as taxpayers and tax authorities with their diverse motives and intentions manipulate their position concerning social phenomena (Rouse, 2007). The formal rationality theory by Weber (1968) may be employed as the central theory to solve the TP puzzle. Brunsson (1982) adds that rationality theory involves making decisions where there is at least a choice/two options. He adds that rationality implies ‘playing’ with rules to get the best possible outcomes.

MNEs and tax authorities’ behaviours are influenced by their roles as taxpayers and regulators respectively. They each strive to achieve their unique objectives and interests. Jonge (2012) notes that rational behaviour is a combination of three factors, namely the capacity to use the right resources to accomplish a set goal, the ability to allocate the scarce resources in ways that provide maximum utility, and the ability of the agent to be self-regarding. Self-regarding entails serving one’s well-being, and this is a fundamental attribute of rational players (Jonge, 2012) in a TP setting. Jose (2009) explains that the rationality concept is useful in resolving the decision-making problem. When applied to TP-related problems, these include the complexity of setting transfer prices that are consistent with the host nation’s tax requirements for MNEs, and making appropriate TP adjustments in the case of the tax authorities (Adams & Drtina, 2010). The rationality theory is deployed towards an inquiry into taxpayer behaviour as well as reactions that tax authorities can take to counter the avoidance tendencies of certain taxpayers. Table 1 below summarises three aspects of TP as a rational decision among these two major players.

Aspects of TP decisions.

| TP Aspect | Findings | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Motives | Profit maximisation, minimisation of tax liability (tax avoidance and evasion), goal congruence, managerial effectiveness are the major decisions of MNEs while tax authorities largely focus on maximising the revenue collected | Beebeejaun (2018), Bhat (2009), Blouin et al. (2018), Mashiri (2018), McNair et al. (2010), Padhi (2019), Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021a), Walton (2019), Wier (2020) |

| Strategies | Over and/under-pricing, mis-invoicing, debt shifting, use of tax havens, use of intangibles, use of service fees, and technical and management fees are the exploitative strategies used by MNEs, while tax authorities utilise strategies such as TP auditing, penalties etc | Mashiri et al. (2021), Choi et al. (2020), Kabala and Ndulo (2018), Klassen et al. (2017), Kwaramba et al. (2016), Marques and Pinho (2016), Oguttu (2017), Reuter (2012) |

| Challenges | Subjectivity of the arm’s length principle, weak capacities of revenue authorities, lack of technical expertise and experience, underdeveloped TP regulations, lack of cooperation, complex MNE transactions, shortage of information and databases, weak dispute resolution mechanisms, and political obstacles are the primary challenges faced by both tax authorities and MNEs. | Barrogard et al. (2018), Blumenthal and Ratombo (2017), Cooper et al. (2017), Curtis and Todorova (2011), Kabala and Ndulo (2018), Mashiri (2018), McNair et al. (2010), Nakayama (2012), Silberztein (2009) |

-

Source: Own compilation.

Faced with options to choose from, rational players carefully calculate the costs and benefits of possible choices and then elect the one which gives them a higher pay-off (Scott, 2000). Scott (2000) says tax-related behaviour is guided by rewards and punishments, and questions why players should choose an action that will benefit others more than themselves. Jose (2009) explains that the rationality concept is useful in resolving the decision-making problem. Considering the thrust of rationality theory, making rational decisions and actions comes at a cost, Jonge (2012) refers to it as the burden of making a rational choice. These may include identifying alternatives and weighing up their costs and benefits. Saunders-Scott (2013) established that increased TP regulation is associated with significant compliance costs for the taxpayer. Eichfelder and Kegels (2012) further note that the compliance costs of taxpayers are not affected by the tax law alone, but by its enforcement through the tax authorities as well. Enforcement of or maximisation of the tax base by tax authorities involves costs such as audit costs. Penalties that come with non-compliance are the determining factor in taxpayer behaviour, according to Kirchler et al. (2008). The same goes with the rewards for compliance, and rational economic actors do not prioritise the interests of others and are, as claimed, exploitative (Scott, 2000). Therefore, tax authorities may decide to strengthen their tax administrative measures without considering the cost implications on the taxpayers, which may stifle voluntary compliance. With this rational decision taken by tax authorities, taxpayers, in turn, engage in tax avoidance and evasion activities without due regard for their actions on the economy, tax revenue mobilisation efforts, and the general public. Both the tax authorities and MNEs ignore the overall economic, social and political costs, thus making decisions, self-serving decisions.

2.2 Dimensions of TP Regulation

TP regulation consists of different dimensions which are embedded in tax administration, enforcement and compliance with TP rules. Governments draft TP legislation, which is enforced by the tax authorities, and these authorities, in the discharge of their duties, can display exploitative tendencies. Similarly, taxpayers are generally antagonistic to the efforts of tax authorities. Jonge (2012) advocates for some sort of win-win situation, which allows one to achieve one’s legacy without sabotaging other actors or players. He also criticises economic actors who improve their situation through interactions that worsen other actors. This is evident in MNEs’ behaviour when they hire tax consultants to design tax avoidance strategies that result in domestic enterprises’ competitive disadvantage while also depriving governments of their national revenue (Oguttu, 2016). MNEs are believed to possess the power and influence to hire and collude with professional accountants in devising sophisticated structures to avoid tax (Mashiri et al., 2021; West, 2018). Some of the exploitative tendencies of MNEs are briefly revealed through certain of their TP strategies such as misinvoicing and the use (or misuse) of management fees (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021a; Sikka & Willmott, 2010).

Tax authorities also exhibit exploitative behaviour in several ways such as failing to train their staff, which ultimately compromises their performance, operational effectiveness, and risk management (Brunsson, 1993: 2). Collier and Dykes (2020) point out that the misapplication of the OECD TP guidelines is extensive due to the pervasive problems associated with the ALP. These challenges include the difficulties in applying the principle attributed to the likely contradictory interpretations given by different tax authorities. The other problems involve the worrying effects of the rising and contested concept of value creation as well as the lack of comparable transactions especially concerning intangibles. Buttner and Thiemann (2017) portend that the regulation of TP especially in the developing country context has been largely politicised by international tax technocrats in an effort to shield their self-serving interests. These and other related issues pervert the creation of effective means to fighting corporate tax avoidance, and MNEs continue leveraging the flaws of the existing TP system. Issues of revenue authority capacitation and inadequacies in resources (human, technical and financial) continue to be thorny issues in addressing TP manipulation in developing countries (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2022). Gupta (2012) established that MNEs continue to shift income to minimise taxes even with increased governmental regulations, while Lohse and Riedel (2012) found stringent TP measures inhibiting tax avoidance. However, Asongu and Nwachukwu (2016) defend the tax avoidance by MNEs arguing that it is justified by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), but Sikka and Willmott (2010) refute such claims arguing that such behaviour is exploitative and detrimental to the public good.

Governments through their various institutions find themselves focused on two directions simultaneously. For example, concerning TP, the Ministry of Finance drafts TP legislation to regulate the TP practising transaction to reduce their manipulation and at the same time protect the tax base. On the other hand, in designing these regulations governments want to strike a balance between their revenue mobilisation needs and remaining a preferred destination for investors and thus attracting foreign direct investment (Cooper et al., 2017; Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021a). In the case of tax authorities, despite their key motive being maximum revenue mobilisation for the country, their aggressiveness is often stifled by political interference and the need to protect the country’s reputation as an investment destination of choice (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2021b; Readhead, 2017).

From the reviewed studies it is evident that the rational decisions of economic actors concerning TP crystallise themselves in the three dimensions of rationality: legal, implementation, and exploitative rationality, and with varying implications. An aggregated synopsis of the findings and their implications as they relate to the three dimensions of TP regulation is presented in Table 2. The table gives a summary of selected studies from the literature review that show how the three dimensions are evident in the actions of government (through tax authorities and ministries of finance), MNEs, and tax consultants.

Dimensions of TP regulation.

| Dimensions of TP regulation | Findings | Implications | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal framework | There is a lack of legislative clarity, weak or underdeveloped TP laws, inconsistencies in the application of tax laws, ineffective TP regulations, fiscal appeals courts, and a lack of appropriate legal expertise | Lack of harmony between administrative capacities and unclear TP legislation cripples the effective implementation of TP laws | Oguttu (2016), Mashiri (2018), Tørsløv et al. (2020), Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021b) |

| Legal rationality is also evident in dispute resolution through the courts, with MNEs defending their position supported by tax consultants | For example, in Zimbabwe TP is regulated using the OECD guidelines (international-oriented), yet the implementation is in terms of national and domestic laws. | ||

| Implementation practice | There is lack of harmony between TP legislation and the resources to implement the legislation. Inconsistency in the interpretation and application of the TP legislation is also evident. The aggressiveness of tax officers and corruption causes conflict between the objectives of tax authorities and MNEs. | These challenges in applying TP legislation such as inadequate skills, expertise, knowledge and resources compromise the implementation of the law. This opens the door for exploitative rationality. MNEs use their resources to get experts to help them organise their transactions in a complex way to exploit TP laws and at times to defend them in legal battles | Barrogard et al. (2018), Blouin and Robinson (2020), Cooper et al. (2017), Mpofu and Wealth (2022), Curtis and Todorova (2011), Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021a), Silberztein, (2009) |

| Political power imbalances and lack of cooperation from some countries and their tax authorities allow for TP manipulation by MNEs or their affiliates in such jurisdictions | |||

| Exploitative practice | Differences in tax jurisdictions, tax rates, and legislation are taken advantage of by MNEs | These differences provide opportunities for revenue leakages | Mashiri et al. (2021), Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021a), Mashiri (2018), Twesige et al. (2020), Sikka (2010) |

| MNEs use their strong financial power to employ experts such as tax consultants, computer specialists, lawyers, and accountants to assist in tax planning and structuring of their TP transactions | This results in high capital flight | ||

| This causes tax evasion and loss of government revenues as taxpayers bribe tax officials | |||

| There appears to be a high level of tax avoidance as the literature estimates that MNE pays 32% less tax than similar local firms. Over 70% of multinational companies claim to be making losses yet there are volumes of internal transfers. | Tax specialists help MNEs avoid tax resulting in an unfair competitive advantage of MNEs against domestic firms. This also impedes tax revenue mobilisation efforts | ||

| Tax erosion results in limited national resources to address global pandemics and national needs. | Kabala and Ndulo (2018), Shongwe (2019), Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021b) |

-

Source: Own compilation.

In the next section, the TP conceptual framework as informed by the literature review that underpins this study is presented.

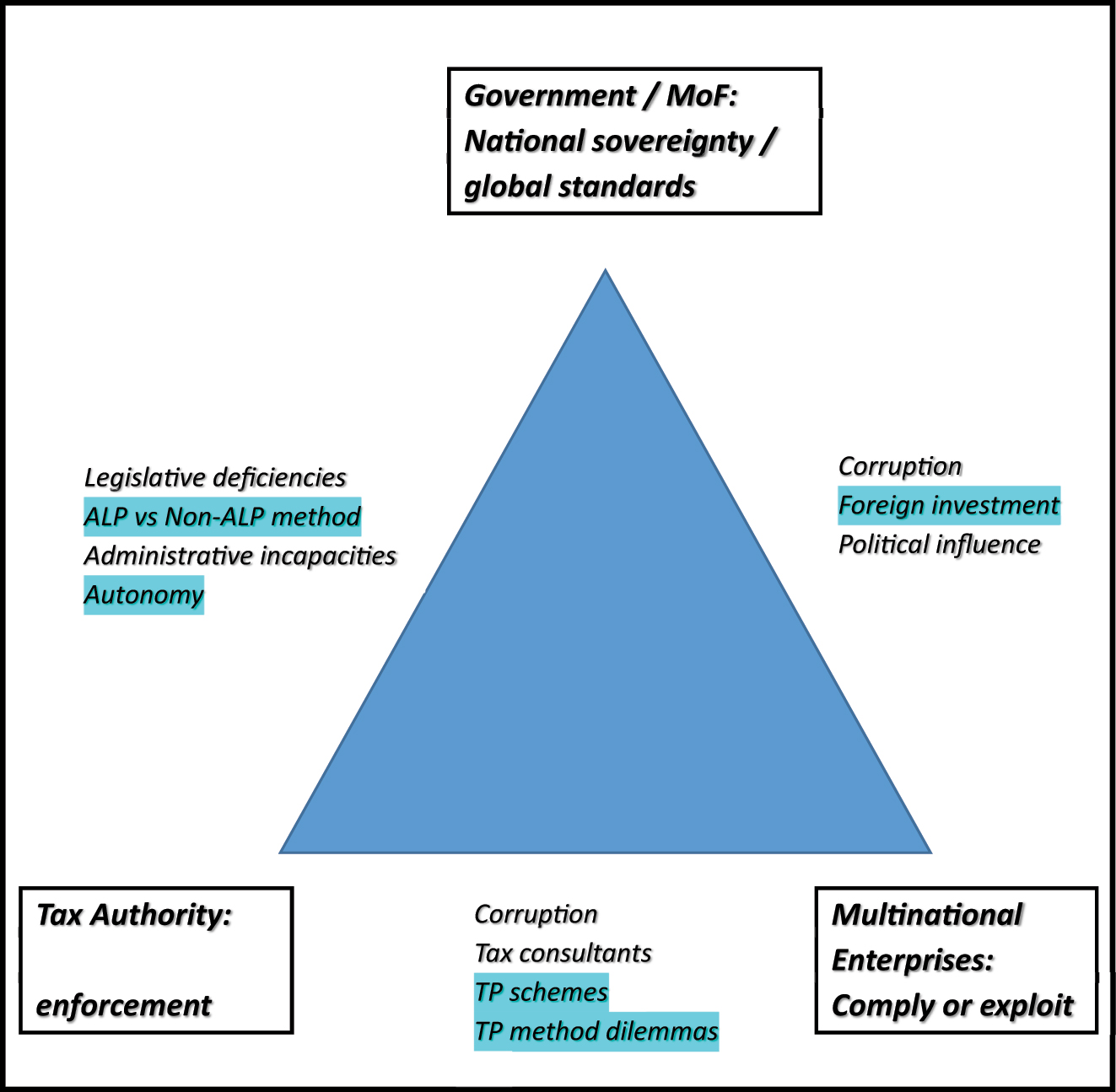

2.3 Conceptual Framework

The different views points stemming from the review of the literature were used in the construction of a general conceptual framework to guide TP regulation concerning developing countries. This framework is set out in Figure 1. This framework be further refined to apply not only to the Zimbabwean context but to other developing countries as well. The framework was premised on a three-layered framework, that is, the legal, implementation, and exploitation dimensions. The three rationality perspectives crystallise in the actions of the three different actors. Facilitating factors, which act as enablers of TP decisions, implementation of, influence the decisions and actions of these actors and compliance with TP legislation. Within the overall TP practice, there were countless instances of implementation reality challenges, and rationalistic decisions infused in literature, and these were categorised around the three-layered dimensions. The governments, which are at the top of the hierarchy, face rational decision-making between tightening their tax laws and creating a “pro-business environment” (Hasseldine et al., 2012). Central to this study is the TP practice theory that is based on the compliance or exploitative elements which are influenced by exogenous (tax consultancy advice) or indigenous factors (such as corruption) as shown in Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for developing country contexts. Source: Own compilation.

Government is denoted for designing legislation. The literature revealed how developing countries’ governments are faced with the dilemma to align TP rules to national priorities rather than just adopting international guidelines to conform to global expectations. Tax authorities are faced with implementation realities because of the legal and administrative resources (Kabala & Ndulo, 2018; Mashiri, 2018). It has been shown that tax authorities are flooded with both legislative deficiencies and administrative incapacities, which undermine their enforcement abilities. Some of the tax authorities are semi-autonomous if not 100% government controlled, hence affecting the level of objectivity expected in executing tax matters and ensuring fairness and equity. Tax-motivated corruption is also rampant in developing countries. Imam and Jacobs (2007) attribute this to low monetary incentives to tax administrators, which has resulted in tax administrators being the initiators of tax evasion through bribes (Gauthier & Goyette, 2014). As if that is not enough, the invisible hand of tax consultants is arguably very influential in determining the compliance or exploitative decisions of MNEs (Mashiri et al., 2021; Wier, 2020). They engage in a number of possible TP schemes such as round-tripping, mis-invoicing and use of services (Sebele-Mpofu, 2021). While governments are faced with the conundrum of choosing between the arm’s length and the non-arm’s length approaches, MNEs are equally confronted with the dilemma of which TP method to choose that would give them the best tax outcome. This comes at a time when some of the MNEs would have obtained investor’s licences by corrupt means. Because of the drive for foreign investment in developing countries, some government officials use their political muscle to indemnify errant MNEs at the expense of the national pocket. These three prominent actors’ decision-making processes have either had positive or negative repercussions on the fiscus.

3 Methodology

Tax decisions are often rooted in human-based behaviours and not simply numerical calculations. The methodological and epistemological positions applied in this study depart from the current mainstream approaches adopted by studies such as Wier (2018), and Merle et al. (2019) who used quantitative approaches in studying TP. This study adopts a qualitative, interpretive approach (as opposed to statistical inferences) to provide insight into TP at a policy and implementation/practice level. Finér and Ylönen (2017) advocate for qualitative approaches, arguing that they are important for enhancing the understanding of complex social phenomena such as TP and in awarding access to previously unknown knowledge against the limitations of dominant quantitative tax avoidance research studies already conducted. To understand the behaviour of the economic actors, qualitative methodologies were adopted as summarised in Table 3. The methodology section was divided into two parts, the non-empirical and the empirical part. The first part explains the literature review (part 3.1) and the second part (part 3.2) explains the empirical data collection through interviews.

Summary of research methodology.

| Research philosophy | Interpretivism was employed to understand the tax behaviour of the economic actors. |

| Research design | The study was exploratory with the use of both primary and secondary data |

| Research approach | Qualitative approach |

| Population and sampling | MNEs, MOF, ZIMRA officers, and tax consultants appointed by MNEs as suggested by Hasseldine et al. (2012: 9). Purposive sampling was applied to obtain information-rich participants |

| Data collection | In-depth interviews performed face to face with MOF, ZIMRA, and tax consultants used by MNEs were conducted |

| Data analysis | Thematic analysis was applied to interview data following Brinkmann and Kvale (2015) with the aid of ATLAS. ti 8™., while NVIVO was used for analysing literature. |

-

Source: Own compilation.

3.1 Literature Review Methodology

As outlined earlier, the study integrated a critical literature review and in-depth interviews. Petticrew and Roberts (2008: 19) explain a critical review as a “critical evaluation of the literature according to argument or logic and/or epistemological tradition of the review subject.” The aim is to bring to light novel conceptualisations and perspectives on the research phenomenon, in this case, TP legislation, enforcement, and compliance. TP as a rational decision can be best presented in the summary of studies as given in Table 1 and that focus on three important aspects of TP in developing countries: TP motives, strategies, and challenges. These three aspects better accentuate the three dimensions of tax ruling that were evident from the literature review: legal, implementation, and exploitative dimensions. Therefore, the need for an organised evaluative review of the literature cannot be overemphasised.

3.1.1 Literature Search and Selection

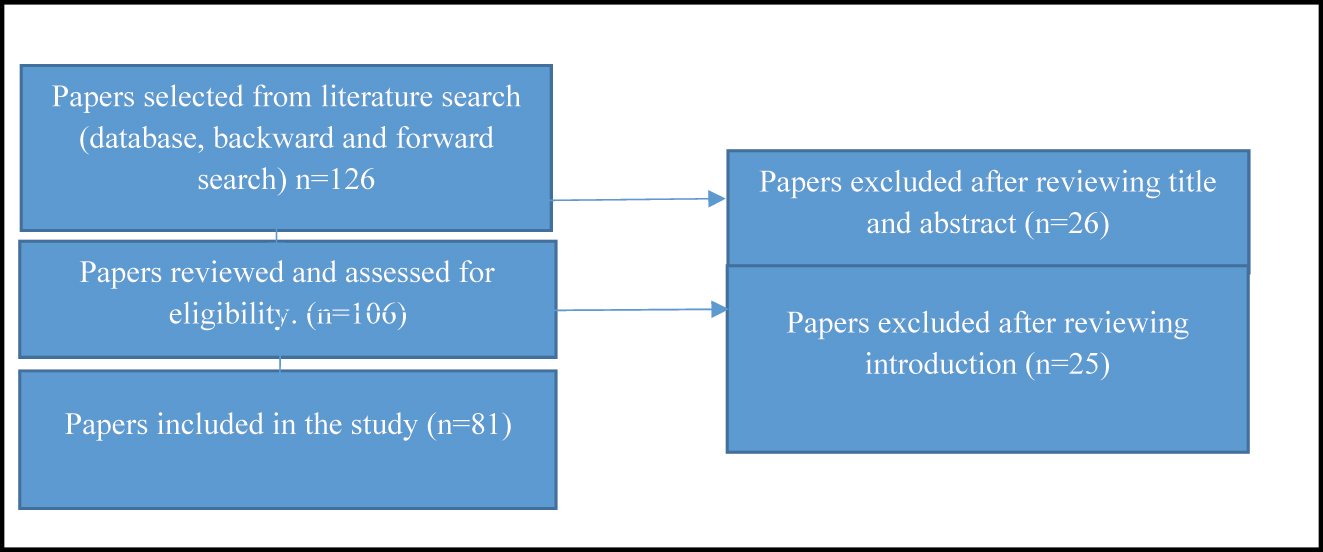

To access relevant studies, the first step was to search for studies on TP regulation; TP legislation (ruling), TP implementation, and TP manipulation (exploitation) in developing countries. The Google scholar database was chosen based on recommendations from various literature review scholars who recommend it based on being extensive, comprehensive, and open access (Snyder, 2019; Xiao & Walton, 2019). Xiao and Walton (2019: 103) adduce the database as “a very powerful open access database that archives journal articles as well as ‘grey literature’ such as conference proceedings, thesis, and reports. The output from the initial database search yielded 90 papers. These papers from the initial search were complemented with snowballing (Jalali & Wohlin, 2012). This was done through “citation analysis or citation mining” of the references of the selected papers as suggested by Padron et al. (2018).

The snowballing was undertaken in three steps. The first step was to search the Google scholar database that provided the first group of 90 papers. Second, from the preliminary papers, the researchers carried out backward snowballing (moving backwards by assessing the reference list) of the articles considered relevant after reading through the titles and abstracts. Third, forward snowballing was also conducted, advancing forward by identifying articles citing the articles selected in steps one and two (Jalali & Wohlin, 2012). Backward snowballing assisted the researchers to find the pioneer works by Brunsson (1982) and Ritzer (2007). On the other hand, forward snowballing allowed the researchers to identify current works related to TP such as Mashiri (2018) and Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021a). In addition, the researchers selected the most cited scholars identified through citation mining on the selected papers and conducted a forward search on them. The most prominent works included those of Oguttu (2016, 2017, 2020), Asongu (2016), Asongu et al. (2019), and Brunsson (1982, 1993, 2007).

3.1.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Decisions

The focus was on original peer-reviewed papers as well as grey literature (conference proceedings and theses). The researchers read all the titles, keywords abstracts, and introductions for the studies’ outputs generated from the database search. The researchers opted to widen the analysis of studies to include the introduction because some titles and abstracts did not provide adequate information on the study. The review methodology process is briefly summarised in the flow chart in Figure 2.

Flowchart summarising the literature review process. Source: Own compilation.

3.2 Data Collection through Interviews

Data was gathered using in-depth interviews with the drafters of the legislation (MOF), the enforcers of the legislation/tax authority (ZIMRA) as well as the taxpayers who are required to comply with the legislation and who in this case are the MNEs or their tax consultants (TCs). To comprehensively understand the tax behaviour of the economic actors in Zimbabwe, interview questions were centred on Zimbabwe’s TP rules, ZIMRA’s administrative capacity, various TP strategies used by MNEs, and international TP guidelines. To achieve the objectives of the study, the ZIMRA Investigations and International Affairs department was purposefully selected as it is the one responsible for handling TP issues in Zimbabwe. The Revenue and Tax Policy Department in the MOF, which is responsible for the drafting of the TP rules in Zimbabwe and tax consultants, formed part of the research participants. A total of 10 ZIMRA officials, seven tax consultants, and three specialists from the MOF were successfully interviewed. The sample was considered adequate to attain the saturation point as guided by Blaikie (2018) and Mpofu (2021), who advocate for small samples as long as participants are knowledgeable, experienced, and have in-depth knowledge of the subject matter. Although the researchers intended to interview MNEs, the MNEs’ accountants were not as receptive as expected, probably because of their limited knowledge of the subject or their fear of potential victimisation because of the sensitivity of taxation issues.

The navigation of ‘rational’ legislative systems such as TP legislation in an assumed conscious as well as contradictory manner informed the approaches, design, and methods. The initial coding, which distilled the lived experiences, interpretations, and realities of the economic actors (Braun & Clarke, 2014), was recorded as a preliminary point of analysis. Data were analysed using deductive content analysis (Elo & Kyngas, 2008) with the aid of ATLAS. ti 8™. During data analysis legal (rule-based), implementation (which is how the rules play themselves out) and the exploitative dimensions of non-compliance had strongly grounded codes. These codes, together with the literature, were interpreted to form themes and then final assertions. Such themes include MNEs’ attitude towards TP, reactions of tax authorities to MNEs’ TP activities and the adequacy of revenue authority resources in implementing and enforcing TP legislation.

All ethical considerations were observed. Permission letters were sought from the participating organisations, consent from individual participants was also attained, personally identifiable data was kept confidential and member checks were conducted to ensure the trustworthiness of the results. This article reinforces the importance of the legislative and administrative muscles of a tax authority. It moves from abstract and anecdotal evidence presented in the literature review section to an empirical dissection of the TP problem in a developing country context in Section 4.

4 Findings

The findings of the research are discussed from the three dimensions of practice which were evident from the reviewed literature. These are the legal, implementation, and exploitative dimensions. The legally anchored dimension is legislation-based which is applied through legislative policy construction. The implementation dimension on the other hand speaks to how the regulations are shifted into strategies and operations, thus the application of TP principles. These two dimensions are closely linked, as implementation relates to the practical application of the legal aspects and the implication of the enforcement of legislation within a given context. MNEs tend to exploit the weaknesses in legislative policy construction and prescription to their advantage to engage in tax avoidance. The crevices may come in three forms: the legal paradigms, the interpretation of the legislation, and the implementation of the legislation as affirmed by Bradley (2015). The findings from the literature review that crystallised themselves in the three dimensions of TP regulation were integrated with the outcomes of the analysis of interview data to give a more balanced perspective with literature being used to support or contradict the findings from primary data. The primary data was discussed under three main themes concerning the research questions guiding the paper. These are the behaviour of MNEs towards TP (4.1.1), reactions of tax authorities to MNEs’ TP activities, and the adequacy of revenue authority resources in implementing and enforcing TP legislation.

4.1 Analysis and Discussion of Results

The following sections give a discussion of the findings as guided by the research questions. The discussion is centred on the interview responses to the behaviour of the three economic actors in relation to legal, implementation and exploitation dimensions.

4.1.1 Behaviour of MNEs towards TP

The tax consultants acknowledged how involving the preparation of the TP documentation makes it difficult for taxpayers to prepare them on their own, although the TCs benefit from this in the form of huge fees income. MNEs have been accused of manipulating transfer prices to maximise group profits, and any tax saving is a bonus. However, Asongu and Nwachukwu (2016) defend the MNE position arguing that tax avoidance by MNEs is compensated by their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities. Sikka and Willmott (2010: 30) refute such claims arguing that such behaviour is exploitative and detrimental to the public good. CSR by an MNE that is avoiding tax would be regarded as impression management. Our analysis reinforces the importance of the legislative and administrative capacities and capabilities of the tax authority. It moves from abstract and anecdotal evidence to empirical dissection of the TP problem in a developing set-up context. ZIMRA1 avowed that the TP manipulative behaviour of MNEs was possible due to capacities constraints faced by the revenue authority in general and concerning TP in particular. ZIMRA4 expressed that “ZIMRA has problems when it comes to resources. We are lacking in almost all aspects, including financial, technical, and human resources. TP knowledge is still scarce even among revenue officers. MNEs ride on these limitations to structure their business operations and transactions to avoid tax”. Oguttu (2016) and Sikka and Willmott (2010) allude to gaps that emerge between legislative frameworks and their implementation as what aids exploitative rationality decision-making by MNEs.

4.1.2 How Tax Authorities React to the TP Practices of MNEs

MNEs have been accused of circumventing tax through strategies such as tax havens or low-tax jurisdictions (Oguttu, 2016). Such behaviour reflects the self-serving attitude of a few MNEs to the detriment of many. Governments and tax authorities are coming up with intensive scrutiny of MNE transactions. The exploitative behaviour of MNEs induces recreation from the authorities in form of TP legislation and rules that include disclosure requirements and penalties. However, ZIMRA is not adequately capacitated both with legislative and administrative resources. ZIMRA3 said, “We are not yet fully equipped to deal with transfer pricing issues, we are still learning the principles”. This, therefore, causes implementation reality challenges. Dharmapala (2014) also stresses inconsistencies in tax laws and their implementation as a limitation to fighting profit shifting. TCs added that the Zimbabwean TP rules do not only apply to cross-border transactions but have an additional requirement for MNEs to account for their domestic transactions for TP purposes. TP is regulated by international standards (Hasseldine et al., 2012), but implementation in Zimbabwe is affected by national context and domestic legislation.

Apart from MNEs’ tax avoidance behaviour, ZIMRA has also been accused of contributing to revenue leakages through corruption. TC3 lamented that “ZIMRA is putting big banners of their vision and mission statements and banners of Zero Tolerance to Corruption while the majority of its officers are corrupt and unscrupulous”. This implies impression management, an unacceptable behaviour, especially from a revenue authority. ZIMRA itself pervades TP with complexity through their rational decisions (with a “state power on our side” mindset) which are inconsistent, uninformed, and paradoxical. This was evident at the field level. The creative and contradictory application of tax laws gives room for tax avoidance and evasion as suggested by Brunsson (1993). Corruption and the discretionary behaviour of ZIMRA officers reduce tax morale among taxpayers and this was emphasised by TC3. “There is also a challenge of lack of uniform interpretation of TP legislation among revenue offers, there is some form of knowledge gap as one officer would tell you something and another a different thing” expressed TC4. The exploitative rationality as discussed by Brunsson (1982) is evident when companies manipulate legislative inconsistencies by making rationalistic resolutions that serve their interests of reducing tax liability, without paying attention to the negative impact of reduced government revenue. This may be the case with MNEs in Zimbabwe as in the case of the Swiss company (Africa, 2020).

4.1.3 The Adequacy of TP Rules and Resources to Implement the TP Laws and Regulations and Curb Tax Avoidance

Respondents had much to say regarding the adequacy of ZIMRA’s resources to implement TP rules. They echoed that the inadequacy of resources especially in a developing country context is common knowledge. While ZIMRA believes it is sufficiently equipped to manage and monitor TP transactions in the country, TCs had a conflicting view. For instance, TC3 argued, “The effectiveness of ZIMRA is marred by cronyism and long office tenure which breeds familiarity and poor performance”. The TC gave an example of long office tenure by the then Commissioner General, and other management positions which were occupied in an acting capacity. TCs also expressed their scepticism over the ability of ZIMRA to dissect cross-border transactions and make informed decisions. TC2 added that ZIMRA does not have state-of-the-art equipment to assess TP transactions, especially those in the mining sector, which he believed provided a big opportunity for TP manipulation and revenue leakages for the country. He gave an example of a mining firm that would take mineral ore out of the country purporting that they are samples going out for testing at their South African laboratory. This depicts exploitative decisions that seek to use opportunistic logic to exploit a situation and/or the legal framework so that profit may be maximised. ‘Exploitative’ means that rules are followed in a creative and contradictory way (loopholes are found) so that tax avoidance or tax evasion happens and governance is not upheld. TC3,4, & 6 also highlighted that while the TP legislation is now in existence, the support system is still weak and vulnerable. The paper’s findings showed that Zimbabwe’s ability to detect and address TP issues was curtailed by the country’s limited administrative capacity of ZIMRA. This includes unskilled and inexperienced staff and redundant and out-of-support information technology. Mashiri et al. (2021) also emphasize the deficiencies of the TP audit systems in developing countries. Brychta et al. (2020) affirm that the major challenges faced in TP audit pertain to intangibles, and Garcia (2016) echoes that the challenges stem from the current TP regimes which are not designed to suit the digital economy and effectively regulate intangible transactions.

ZIMRA also noted with concern that the department that deals with TP issues is housed at the head department building only, which is a huge limitation when it comes to executing TP issues at a regional level. ZIMRA itself pervades TP with complexity through their rational decisions (with the code “state power on our side” mindset) which are inconsistent, uninformed, and paradoxical. This was evident at the field level. Within the overall TP practice, there were countless instances of implementation reality challenges, and opportunistic decisions infused in the empirical data categorised around the three-layered dimensions of TP regulation. This study captures the text and sub-text of TP services rendered to MNEs by tax consultants being the “Janus-faced” elements (elements where one has to look in two directions simultaneously) of compliance and exploitative responses to TP situations.

Data (ZIMRA 1, 2, 3, 4) has also revealed deficiencies in the legislation. Zimbabwe largely borrowed the OECD TP Guidelines and is faced with the dilemma to align TP rules to national priorities against appeasing global expectations. It has also shown that tax authorities are flooded with both legislative deficiencies and administrative incapacities, which undermine their enforcement abilities and determine their exploitative choices (given that they have state power on their side). For example, ZIMRA 3 acknowledged that Zimbabwe simply followed the international guidelines without adequately assessing their applicability to the Zimbabwean economy. MNEs, on the other hand, have exploitative traits “close to their skin”, and given their resourcefulness they can afford to pay exorbitant fees of tax practitioners in exchange for tax-saving advice which has negative effects on the citizens and positive effects on the shareholders.

Though ZIMRA (5, 6, 7) claim that it has administrative effectiveness, the majority of the tax consultants strongly disagreed with this. In many instances, tax consultants (TC1,2,3,4) were acknowledging the conception of an unpredictable and uneven tax system that allows inefficiencies. These inefficiencies were a product of implementation realities affected by legislative gaps, communication gaps, interpretive discord, financial constraints, and knowledge gaps. Oguttu (2016, 2020) also believes that developing countries lack the resources to fight base erosion.

ZIMRA itself pervades TP with complexity through their rational decisions (with the “state power on our side” mindset) which are inconsistent, uninformed, and paradoxical. This was evident at field level where TCs highlighted that ZIMRA is not very open to negotiating and engagement with taxpayers, they lean more on their power of “Pay now and question later” which is instituted in law to compel appealing taxpayers to pay the disputed amount and be reimbursed when proven correct. ZIMRA officials are also seen to be practising impression management by displaying banners of zero tolerance for corruption yet they are seen to be extorting money and taking bribes from taxpayers who are not willing to pay what the government is legally demanding. This was alluded to by TC3 who pointed out that “corruption is rife at ZIMRA. MNEs win some of these cases with the help of ZIMRA officials that work behind the scenes, guiding the MNEs on how to build strong cases against the revenue authority”. This behaviour has not been adequately explored in the existing literature. The use of foreign databases is permissible by law but hypocritical and exhibits impression management as these databases do not reflect the economic characteristics of Zimbabwean pricing models.

The governments, which are at the top of the hierarchy, face rational decision-making between tightening their tax laws and creating a “pro-business environment” to meet their economic needs (Hasseldine et al., 2012). For African states, the elite, especially the politicians that do not necessarily pay tax (Christensen, 2009), and because of impunity and control politics, there are very little if any legal implications on these larger-than-life political personalities who are operating big businesses in Zimbabwe. These politicians shield some MNEs from tax authorities. ZIMRA2 expressed that “as tax officers contended with so much political pressure, it is not about applying legislation by the book. Political interference is a big problem”. Sikka and Willmott (2013) observe that the political elite sometimes become a law to themselves to such an extent that legal structures such as ZIMRA become intimidated to penalise such elite figures for non-compliance with tax laws. This is typical in Zimbabwe, and such structures are barred from enforcing the law by the people who are in control of the government. Primary data (TC2 and 3) have also uncovered the corruption of unscrupulous ZIMRA officials who extort money from errant taxpayers through bribes. All this exhibits a consequentialist approach to governance which is self-serving and with negative repercussions on the economy at large.

There is a clear message throughout that Zimbabwe has the intent to respond to exploitative rationalities, however, these efforts are hindered by some implementation realities. Based on literature and primary data the study provides a framework that highlights key issues that could be useful for policymakers and tax authorities.

5 Conclusion, Limitations, and Recommendations

This study explored the decision-making behaviour of economic actors with regards to TP by applying the rationality theory. The TP phenomenon is indisputably complex and intricate yet a major tool used for tax base erosion, thus an understanding of the economic players involved is important for policymakers and tax authorities. The study also sought to establish the reactions of tax authorities and whether their strategies were enough to curtail TP manipulations. The findings show that the TP regulation can be expanded into three dimensions; legal, implementation, and exploitative realities. This regulation trichotomy is a useful lens to understand TP as a phenomenon and help uncover the hidden traits of these economic players. The findings showed the ability of MNEs to employ tax consultants in aggressive tax avoidance to maximise shareholder wealth. The study revealed that the legislative and administrative capacities availed to the tax authority are not sufficient to deal with the complex phenomenon. Therefore, the need for further government intervention in TP issues was evident if TP is to be effectively dealt with. The tug-of-war between national standards and international standards was also visible, and the study echoes the need for country-specific redress of TP issues. While the TCs cannot be exonerated from the MNE shenanigans, their role needs to be explored at length in future research. The study moves from an abstract frame of analysis to a more cogent analysis consistent with practice and its institutional dimensions and processes. The study provides a basis for which governments, policymakers, and tax authorities can devise strategies to minimise tax avoidance through TP. The regulation trichotomy presented herein becomes a practical ‘model’ for tax authorities to use in their fight against tax base erosion and profit shifting.

The study sought to explore the decision-making behaviour of economic actors concerning TP by applying the rationality theory. The study revealed that globalisation has exposed nations to a high risk of base erosion and profit shifting due to the interconnectedness of multinational transactions as well as the diverging interests in tax matters. The rationality theory has proved to be useful in extrapolating this behaviour with decisions that are favourable to one’s course emerging as the preferred choice in either party. The notion of rationality helped elucidate the intricacies and nuances of TP by developing a rationality trichotomy – the three dimensions of rationality (legal, implementation, and exploitative) that were evident in the economic actors. This three-dimensional frame of analysis was backed up through qualitative data collection and analysis through a literature review (on developing countries) and interviews focusing on one country, but with generic areas that may be applied more universally. While the legal dimension is largely independent of the tax authority and the MNEs, implementation rationality, and exploitative rationality play a significant role in both the tax authority and MNEs. For example, the tax authority’s deficiencies in the resources that enable it to enforce the TP laws allow MNEs to exploit the lack of financial resources to hire qualified personnel and even to regularly carry out audits. Similarly, the MNEs use their abundant resources to hire tax consultants to advise them on TP matters such as documentation, how to structure transactions and to assist with disputes. This touches on both implementation and exploitative dimensions. This then results in MNEs hiring the services of tax consultants that help them to reduce their tax liabilities which reveals exploitative tendencies. The study ratifies the role played by tax consultants as carriers of the Janus elements of compliance and exploitative responses to TP by MNEs.

The study acknowledges that a gap exists between the legal and the implementation rationality, which was alluded to by Oguttu (2016). She outlines three factors that aggravate BEPS in Africa. These are: (1) a lack of relevant international tax laws, (2) inadequately developed domestic laws causing techniques such as treaty abuses, and (3) limited administrative capacity (which includes heterogeneous tax systems, incompetent and corrupt tax officials, lack of training of staff, poor remuneration and poor staffing policies and lack of electronic and technological advancement of tax systems). There is strong evidence of these same issues in the data, for instance, a lack of legislative clarity, ineffective fiscal appeal, court backlogs, a lack of expertise, and corruption. Data has shown that there are inconsistencies in the legislation, for example on the application of TP rules and thin capitalisation rules which restrict the deduction of debt to 3:1 instead of allowing the arm’s length principle to determine what is deductible. ZIMRA has also bemoaned the weak judicial systems and fiscal courts, which result in protracted transfer pricing cases. These and other challenges place Zimbabwe in a precarious situation of excessive revenue losses which if harnessed could have been channelled towards the economic development of the country.

The findings of this paper show that substantial work still needs to be done to strengthen the TP rules in Zimbabwe. They also reveal that Zimbabwe is peculiar in that the canons of taxation are not observed at a higher level thereby exposing Zimbabwe to high levels of profit shifting and negatively affecting ordinary citizens. The study also concurs with Oguttu (2016) that the OECD fails to capture the specific needs of African developing states, and therefore nations should not just take up prescriptions of international laws that are a representation of a few countries, but rather exercise their sovereignty. Furthermore, the study provides insight into the practical dimensions of TP regulation as applied by the major economic actors (Government, Tax authorities, and MNEs), brings new insights, and developed a conceptual framework (Figure 2) that can be used by tax authorities and governments to help alleviate BEPS in their jurisdictions. The application of this confluence of practical dimensions has provided a certain rendition of TP as a practice. The need to balance foreign investment, public demands, global fitting, and national priorities within diverging laws, standards and processes espouse the overt and covert dimensions of TP. The findings of the study uncover the TP regulation realities, what moderates them and how they influence the tax compliance and enforcement decisions of MNEs and tax authorities respectively. The conceptual framework could be used to guide policy construction concerning TP regulation in developing countries. Despite the limitations of the qualitative method used in this study, the following recommendations are made:

5.1 Strengthen the Legislative Framework

Legislative gaps were evident, providing an opportunity for MNEs to exploit and manipulate tax liabilities. The need for a robust tax legislative system cannot be overemphasized. Zimbabwe should consider incorporating Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) and country-by-country reporting documentation as recommended by Sebele-Mpofu et al. (2021b).

5.2 Instil Cooperation and a Relationship Based on Mutual Trust, Transparency, and Respect

Purely focusing on taking rational decisions for their respective constituencies, the rational economic actors (MNEs, revenue authorities, and tax consultants) will find themselves at loggerheads yet cooperation is key to both tax legislation enforcement and compliance. The conflicting decisions perpetuate mistrust and the hide-and-seek game, crippling cooperation and voluntary disclosure as well as compliance (Sebele-Mpofu et al., 2022). There is a need to cultivate a spirit of trust, responsibility, ethical conduct, and a synergistic relationship between these key rational economic actors in the tax revenue mobilisation efforts.

5.3 Allocation of Adequate Resources for the Tax Authorities to Execute Their Mandates

Developing countries’ revenue authorities should be allocated with human and financial resources that enable them to fulfil their mandate. Given the elusive nature of intangibles, tax officials need to be trained and equipped in order for them to be able to audit intra-firm transfers of intangible assets. Although not yet adopted, developing countries should assess the applicability of Pillar One and Pillar Two frameworks.

5.4 Increase Transparency and Accountability of Public Officials

Corruption and bribes amongst tax authority officials are found to be rampant in both the literature and the empirical findings from interviews. Governments should employ stringent measures to curb such practices, for instance employing prohibitive penalties for perpetrators, that is for both MNEs and tax officials. The fear of reputational damage, as well as the fines and possibility of prosecution or cancellation of operating licenses for MNEs, could indirectly encourage compliance. Hasseldine et al. (2012) call for the calibration of policies and administrative responses to tax avoidance.

5.5 Intensive Scrutiny of MNEs

The opportunistic behaviour of MNEs is contrary to business ethics and general interest. However, a culture of cooperative compliance should be cultivated, and the onus is upon the government to develop a robust tax system, which enables ZIMRA to discharge its mandate with the necessary legislative support. It is imperative for developing countries to train their tax officers in a way that they are able to manage efficient audits to search for sophisticated profit drivers such as intangible functions. That includes tax authorities such as ZIMRA which should be actively involved in TP audits and scrutinise MNE transactions especially those in the mining sector (Mashiri et al., 2021).

5.6 Regulation of Tax Practitioners

Findings also revealed that it is not only the MNEs that need to be regulated. The call by Hasseldine et al. (2012) for states to regulate tax consultants is critical, as it is evident that other countries are prosecuting accounting firms for misconduct and for selling unacceptable tax avoidance strategies/schemes. For example, South Africa’s KPMG and the Gupta case implicated one of the big four accountancy firms in misconduct (Cropley & Brock, 2017). Most African countries including Zimbabwe do not have such regulations, so they would benefit from introducing them.

5.7 Design Regional/Nation-Specific TP Guidelines

The study also concurs with Oguttu (2016: 20) that the OECD fails to capture the specific needs of the African developing states. Consequently, these latter nations should not adopt prescriptions of international laws and guidelines which are a representation of a few countries (in some cases only developed countries), but rather exercise their sovereignty. This could help in contextualising TP regulation to the needs, risks, and challenges of African national and individual national environments.

Stemming abusive TP through strengthening the legislative framework, capacitating the tax authority, and regulating and monitoring MNE activities as well as the activities of tax consultants should help achieve a nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. Future studies should therefore explore the impact of these measures on revenue collection in developing economies.

Acknowledgment

This research is an excerpt from a PhD thesis and did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit entities.

References

Adams, L., & Drtina, R. (2010). Multinational transfer pricing: Management accounting theory versus practice. Management Accounting Quarterly, 11(3), 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

Africa. (2020). Swiss company accused of tax dodging in Zimbabwe. https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-09-03-swiss-company-accused-of-tax-dodging-in-zimbabwe/ Search in Google Scholar

Asongu, S. A. (2016). Rational asymmetric development: Transfer mispricing and Sub-saharan Africa’s extreme poverty tragedy Economics and political Implications of international financial reporting standards (pp. 282–302). IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-4666-9876-5.ch014Search in Google Scholar

Asongu, S. A., & Nwachukwu, J. C. (2016). Transfer mispricing as an argument for corporate social responsibility, AGDI working paper, No. WP/16/031. African Governance and Development Institute (AGDI), Yaoundé.10.2139/ssrn.2832655Search in Google Scholar

Asongu, S. A., Uduji, J. I., & Okolo-Obasi, E. N. (2019). Transfer pricing and corporate social responsibility: arguments, views and agenda. Mineral Economics, 32(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-019- 00195-2.10.1007/s13563-019-00195-2Search in Google Scholar

Barrogard, E., Calderón, D., de Goede, J., Gutierrez, C., & Verhelel, G. (2018). Implementing OECD/G20 BEPS Package in Developing Countries. Cooperation and IBFD. https://www.ibfd.org/sites/ibfd.org/files Search in Google Scholar

Beebeejaun, A. (2018). The efficiency of transfer pricing rules as a corrective mechanism of income tax avoidance. Journal of Civil Legal Sciences, 7(1), 1–9.Search in Google Scholar

Bhat, G. (2009). Transfer pricing, tax havens and global governance. Discussion Paper [PhD Thesis]. University of South Africa.Search in Google Scholar

Bhumika, M. (2018). The right to development and illicit financial flows: Realizing the sustainable development goals and financing for development. In Human rights council working group on the right to development nineteenth session.Search in Google Scholar

Biondi, Y. (2017). The firm as an enterprise entity and the tax avoidance conundrum: Perspectives from accounting theory and policy. Accounting, Economics, and Law: Convivium, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2017-0001.Search in Google Scholar

Blaikie, N. (2018). Confounding issues related to determining sample size in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(5), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1454644 Search in Google Scholar

Blouin, J., & Robinson, L. A. (2020). Double counting accounting: How much profit of multinational enterprises is really in tax havens? Available at SSRN 3491451.10.2139/ssrn.3491451Search in Google Scholar

Blouin, J. L., Robinson, L. A., & Seidman, J. K. (2018). Conflicting transfer pricing incentives and the role of coordination. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12375 Search in Google Scholar

Blumenthal, R., & Ratombo, M. (2017). TAX008 the challenges faced by developing countries regarding transfer pricing. In Southern African Accounting Association, Biennial International Conference Proceedings. Drakensberg South Africa. http://www.saaa.org.za Search in Google Scholar

Bradley, W. (2015). Transfer pricing: Increasing tension between multinational firms and tax authorities. Accounting and Taxation, 7(2), 65–73.Search in Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, G. T. (2014). Thematic Analysis. Qual Res Clin Health Psychol, 24, 95–114.Search in Google Scholar

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Brunsson, N. (1982). The irrationality of action and action rationality: Decisions, ideologies, and organizational actions. Journal of Management Studies, 19(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1982.tb00058.x Search in Google Scholar

Brunsson, N. (1993). The necessary hypocrisy. International Executive, 35(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.5060350102 Search in Google Scholar

Brunsson, N. (2007). The consequences of decision-making. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brychta, K., Istok, M., Sulik-Gorecka, A., & Poreisz, V. (2020). Transfer pricing in V4 countries. VUTIUM.10.13164/9788021458734Search in Google Scholar

Buttner, T., & Thiemann, M. (2017). Breaking regime stability? The politicization of expertise in the OECD/G20 process on BEPS and the potential transformation of international taxation. Accounting, Economics, and Law: Convivium, 7(1), 20160069. https://doi.org/10.1515/ael-2016-0069 Search in Google Scholar

Cazacu, A. L. (2017). Transfer Pricing – An international problem. Junior Scientific Researcher, 3(2), 19–25.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, J. P., Ishikawa, J., Okoshi, H., Tørsløv, T., Wier, L., Zucman, G., & Lockwood, B. (2020). Profit-splitting rules and the taxation of multinational digital platforms: Comparing strategies. VoxEU. org.Search in Google Scholar

Christensen, J. (2009). Africa’s Bane: Tax havens, capital flight and the corruption interface. In Working paper 1/2009 (pp. 1–23). Real Instituto Elcano. https://media.realinstitutoelcano.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/wp1-2009-christensen-africa-bane-taxhavens-capitalflight-corruption.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Collier, R. S., & Dykes, I. F. (2020). The virus in the ALP: Critique of the transfer pricing guidance on risk and capital in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bulletin for International Taxation, 74(12), 702–720.10.59403/5ec69ySearch in Google Scholar

Cooper, J., Fox, R., Loeprick, J., & Mohindra, K. (2017). Transfer pricing and developing economies: A Handbook for policymakers and practitioners. The World Bank.10.1596/978-1-4648-0969-9Search in Google Scholar

Cropley, Ed, & Brock, J. (2017). KPMG’s South Africa bosses were purged over Gupta scandal. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kpmg-safrica/kpmgs-south-africa-bosses-purged-over-gupta-scandal-idUSKCN1BQ16P [Accessed 30 September 2018].Search in Google Scholar

Curtis, M., & O’Hare, B. (2017). Lost revenues in low-income countries. Curtis Research. www.curtisresearch.com [Accessed 17 November 2020].10.2139/ssrn.3069383Search in Google Scholar

Curtis, A., & Todorova, O. (2011). Spotlight on Africa’s transfer pricing landscape. Transfer pricing perspectives: Special edition. Taking a detailed look at transfer pricing in Africa https://www. pwc. com/en_GX/gx/tax/transfer-pricing/management strategy/assets/pwc-transfer-pricing-africa-pdf. pdf [Accessed 30 August 2015].Search in Google Scholar

Dharmapala, D. (2014). What do we know about base erosion and profit shifting? A Review of the empirical literature. CESifo Working Paper. No. 4612.10.2139/ssrn.2398285Search in Google Scholar

Dharmapala, D., & Riedel, N. (2012). Earnings shocks and tax-motivated income-shifting: Evidence from European multinationals, CESifo working paper. Public Finance. No. 3791.10.2139/ssrn.2045989Search in Google Scholar

Eichfelder, S., & Kegels, C. (2012). Compliance costs caused by agency action? Empirical evidence and implications for tax complianc [Schumpeter discussion papers, No. 2012-005]. University of Wuppertal, Schumpeter School of Business and Economics. Wuppertal. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:468-20120410-151433-1 [Accessed 20 May 2019].Search in Google Scholar

Ekstrom, S. C., Dall, L., & Nikolajeva, D. (2014). Tax motivated transfer pricing. Seminar Paper 05-06-2014, LundsUniversitet.Search in Google Scholar

Elo, S., & Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.xSearch in Google Scholar

Finér, L., & Ylönen, M. (2017). Tax-driven wealth chains: A multiple case study of tax avoidance in the finnish mining sector. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 48, 53–81.10.1016/j.cpa.2017.01.002Search in Google Scholar

Garcia, J. C. D. (2016). Transfer pricing for intangibles: Problems and solutions from Colombian perspective. Revista De Derecho Fiscal, 8(8), 103–123. https://doi. org/10.18601/16926722.n8.08Guj 10.18601/16926722.n8.08Search in Google Scholar

Gauthier, B., & Goyette, J. (2014). Taxation and corruption: Theory and firm-level evidence from Uganda. Applied Economics, 46(23), 2755–2765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.909580 Search in Google Scholar

Gupta, P. (2012). Transfer pricing: Impact of taxes and tariffs in India. Vikalpa, 37(4), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920120403 Search in Google Scholar

Hai, O. T. and See, L. M.. (2011). Intention of tax non-compliance – examine the gaps. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(7), 79–83.Search in Google Scholar

Hasseldine, J., Holland, K., & van der Rijt, P. (2012). Companies and taxes in the UK: Actors, actions, consequences and responses. eJournal of Tax Research, 10(3), 532–551.Search in Google Scholar

Holtzman, Y., & Nagel, P. (2014). An introduction to transfer pricing. The Journal of Management Development, 33(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmd-11-2013-0139 Search in Google Scholar

Imam, P. A., & Jacobs, M. D. F. (2007). Effect of corruptionon tax revenues in the Middle East. International Monetary Fund.10.2139/ssrn.1075886Search in Google Scholar

Jalali, S., & Wohlin, C. (2012). Systematic literature: Database searches vs. backward snowballing. In 6th ACM-IEEE international Symposium on empirical software Engineering and measurement. ESEM.10.1145/2372251.2372257Search in Google Scholar

Jonge, J. (2012). Rethinking rational choice theory. A companion on rational and moral action. Palgrave MacMillan.Search in Google Scholar

Jose, L. B. (2009). Decision theory and rationality. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kabala, E., & Ndulo, M. (2018). Transfer mispricing in Africa: Contextual issues. Southern African Journal of Policy and Development, 4(1), 6.Search in Google Scholar

Kirchler, E., Hoezl, E., & Wahl, I. (2008). Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: The “slippery slope” framework. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.05.004 Search in Google Scholar

Klassen, K. J., Lisowsky, P., & Mescall, D. (2017). Transfer pricing: Strategies, practices, and tax minimization. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(1), 455–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12239 Search in Google Scholar

Kotz, D. (2000). Globalisation and neoliberalism. Rethinking Marxism, 12(2), 64–79.10.1080/089356902101242189Search in Google Scholar

Kwaramba, M., Mahonye, N., & Mandishara, L. (2016). Capital flight and trade misinvoicing in Zimbabwe. African Development Review, 28(S1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12181 Search in Google Scholar

Levin, J., & Milgrom, P. (2004). Introduction to choice theory. http://web.stanford.edu/∼jdlevin/Econ Search in Google Scholar

Li, J. (2006). Transfer pricing and double taxation: A review and comparison of the New Zealand, Australia and the OECD transfer pricing rules and guidelines. International Tax Journal, Spring, 9–62.Search in Google Scholar

Linder, K. (2019). Tax evasion in SubSaharan Africa. https://borgenproject.org/tax-evasion-in-sub-saharan-africa/ [Accessed 20 November 2020].Search in Google Scholar

Lohse, T., & Riedel, N. (2012). The impact of transfer pricing regulations on profit shifting within European multinationals, FZID Discussion Papers, No. 61-2012. Available from: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:100-opus-7962 [Accessed 21 January 2022].Search in Google Scholar

Marques, M., & Pinho, C. (2016). Is transfer pricing strictness deterring profit shifting within multinationals? Empirical evidence from Europe. Accounting and Business Research, 46(7), 703–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2015.1135782 Search in Google Scholar

Mashiri, E. (2018). Regulating multinational enterprises (MNEs) transactions to minimise tax avoidance through transfer pricing: Case of Zimbabwe [PhD Thesis]. UNISA.Search in Google Scholar

Mashiri, E., Dzomira, S., & Canicio, D. (2021). Transfer pricing auditing and tax forestalling by multinational corporations: A game theoretic approach. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1907012. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1907012 Search in Google Scholar

Maya, F. (2015). Can stopping ‘Tax dodging’ by MNEs close the gap in finance for development? What do the big numbers really mean? CGD Policy Paper 69:32. Center for Global Development.Search in Google Scholar

Merle, R., Al-Gamrh, B., & Ahsan, T. (2019). Tax havens and transfer pricing intensity: evidence from the French CAC-40 listed firms. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1647918. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 23311975.2019.1647918.10.1080/23311975.2019.1647918Search in Google Scholar

McBarnet, D. (2001). When compliance is not the solution but the problem: From changes in law to changes in attitude. Australian National University. Centre for tax system and integrity.Search in Google Scholar