Abstract

The OECD considers compliance with the OECD principles of corporate governance and reduced corruption to be positively associated with economic prosperity. Prior empirical research supports this notion for developed countries. However, findings for developing and emerging countries are more diverse, as some studies document an “East Asia paradox” and link higher levels of corruption with positive outcomes at the firm or country level. Our case study on the Socialist Republic of Vietnam contributes to the literature by identifying determinants of these mixed findings. Relying on triangulation, our results suggest that internationalizing and international firms must adhere to OECD expectations to prosper, while domestic firms prefer operating in corrupt but stable conditions. Due to this mechanism, noncompliance with OECD principles and corruption can deter foreign direct investments and thus negatively influence economic growth. Nevertheless, noncompliance with OECD principles and corruption can still work to benefit domestic firms. Given our results for Vietnam, we argue that the internationalization of the business models of the firms analyzed might explain the prior inconclusive empirical findings.

Table of contents

Introduction

Related literature and research questions

OECD principles of corporate governance and economic prosperity

International standards of corporate governance

Association between corporate governance and economic prosperity

Corporate governance quality in Vietnam

Interrelation between corporate governance quality and corruption

Development of research question 1

Corruption and economic prosperity

nternational view on corruption

Association between corruption and economic prosperity

“East Asia Paradox”

Development of research question 2

Methodological approach

Case study and triangulation

Descriptive analysis of regulatory and macroeconomic developments

Semistructured interviews with stakeholders

Results of descriptive analysis of regulatory and macroeconomic developments

Reforms on the corporate governance framework and anti-corruption measures

Concurrent macroeconomic development

Development of quantitative measures for corporate governance quality and corruption

Correlation analysis

Discussion

Results of semistructured interviews

OECD principles and economic prosperity

General perceptions of compliance with OECD principles

Discrepancies between compliance on paper and in practice

Association between compliance with OECD principles and economic prosperity

Political stability and economic prosperity

Corruption and economic prosperity

Level of corruption and measures against corruption

Association between corruption and economic prosperity

Discussion

Summary and conclusions

Appendix A: Definition of variables

Appendix B: Sources and computation of the applied corporate governance and corruption indicators

Appendix C: Semistructured interview guidelines and open questions

References

1 Introduction

Whether an economy benefits from the adoption of international standards of corporate governance and regulatory measures against corruption appears to be a question that is easy to answer. Prior empirical research supports the notion of a positive correlation between the adoption of international standards of corporate governance and economic prosperity at the country and firm levels (e. g. La Porta, Lopez‐de‐Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1997; Levine & Zervos, 1998; Rajan & Zingales, 1998; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 2000; Gombers et al., 2003; Larcker & Tayan, 2015). There are, however, some doubts about whether those findings are generalizable to developing and emerging countries (e. g. Chen, Li, & Shapiro, 2011; Claessens & Fan, 2002; Young, Peng, Ahlstrom, Bruton, & Jiang, 2008). The findings regarding corruption are more diverse and inconclusive (OECD, 2013). Some studies find that corruption is negatively associated with economic prosperity (e. g. Ahlin & Pang, 2008; Borlea, Achim, & Miron, 2017; Donadelli, Fasan, & Magnanelli, 2014; Garmaise & Liu, 2005; Mauro, 1995; Mo, 2001; North, 1990; Romer, 1994; Shleifer & Vishny, 1993). Moreover, some studies argue that corruption negatively affects the positive association between corporate governance and economic prosperity (e. g. Owoeye & van der Pijl, 2016). Another stream of research finds an “East Asia paradox” and links higher levels of corruption with positive outcomes at the firm or country level (e. g. Cheung, 2005; Huntington, 1968; Leff, 1964; Lui, 1985; Nguyen, Doan, Nguyen, & Tran-Nam, 2016; Sahakyan & Stiegert, 2012; Wang & You, 2012). The developmental state literature finds that positive economic developments in East Asian countries such as China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and the Southeast Asian region are associated less with the adoption of international standards of corporate governance and corruption or market-conforming policies in general terms and more with government intervention, industrial policy, education and societal transformation with a shift to scientific ways of thinking (Haggard, 2018; Stiglitz, 1998, 2003).

Prior research predominantly applied quantitative research methods and examined country-level variables or employed both country- and firm-level variables. The results obtained on this aggregated level are, to some extent, mixed or inconclusive. Little is known about the determinants of such puzzling results. This paper fills this research gap and adds to the discussion on whether or why the adoption of international standards of corporate governance and reduced corruption are “good or bad” for an economy. Specifically, we aim to contribute to the literature by identifying the determinants of the inconclusive findings of prior studies. For the methodological approach, we conduct a case study on the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and rely on between-methods triangulation. We first provide a descriptive analysis of Vietnam’s macroeconomic development and concurrent regulatory reforms causing the corporate governance framework to converge towards international standards and reduced corruption. We then conduct semistructured interviews at the stakeholder level. In doing so, we examine a single case but use multiple units of analysis.

We select the case of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam for several reasons. As a frontier economy that is becoming an emerging economy, Vietnam offers a unique setting in which to examine the association among the adoption of international standards of corporate governance, high levels of corruption, and economic prosperity. Unlike the “shock-therapy” approaches of former communist countries in Eastern Europe (Black, Kraakman, & Tarassova, 2000; Popov, 2000), Vietnam has chosen a gradualist approach to reform its corporate governance framework, align it with the best practice recommendations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (IFC, 2010; Nguyen & Richard, 2011), and implement measures to reduce its persistently high level of corruption (World Bank & MPI, 2016). Unlike former Eastern European countries and other East Asian countries, such as Thailand, Vietnam has not experienced a regime change. Accordingly, the Vietnamese setting allows us to examine the association among corporate governance, corruption and economic prosperity in a frontier country that has not experienced “shock therapy” and the influences of political changes.

Our descriptive analysis shows that in Vietnam, numerous legal reforms and commitments to anti-corruption measures are linked to increases in gross domestic product (GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI). In addition to this qualitative observation of simultaneous developments, we rely on quantitative measurement approaches by the World Bank and Transparency International that capture corporate governance quality and corruption indicators. Analyzing time series data from 1996 to 2016, we find that corporate governance quality improved and corruption decreased. A correlation analysis shows a positive and statistically significant correlation among corporate governance quality metrics and GDP and FDI but a negative relation with corruption indicators. We also find a negative and statistically significant association among some corporate governance quality metrics and corruption indicators.

The findings of our semistructured interviews are in line with our main descriptive results. The interviews also reveal that stakeholders’ perceptions primarily depend on whether interviewees refer to firms with local or international business models. In general, compliance with OECD principles of corporate governance (OECD, 1999b, 2015) is considered to be associated with higher FDI and better international trade prospects on a country level, which will be reflected in better performance at the firm level and higher economic prosperity at the country level. More specifically, a positive correlation between compliance with the OECD principles of corporate governance and firm performance is expected in the long term, especially for firms that engage in international business. In the absence of enforcement and litigation, interviewees do not consider a well-known high level of corruption necessarily harmful at the firm level, but such corruption is assumed to negatively affect economic prosperity by hindering FDI. Nevertheless, for domestic firms, interviewees point to the possibility of engaging in corruption to increase revenues and firm performance.

Examining the case of Vietnam by employing between-methods triangulation leads us to observe a positive association between corporate governance and economic prosperity and a negative association between corruption and economic prosperity primarily for internationalizing and international firms, but this relation might not be apparent for local businesses, at least in the short term. While internationalizing or international firms must adhere to OECD expectations, domestic firms can make noncompliance and corruption work for their benefit or can at least navigate such an environment. Accordingly, we argue that the internationalization of analyzed firms might play an important role in explaining the puzzling results and the “East Asian paradox” found in prior research.

Our results should be interpreted with some caution, as our case study faces several limitations. Our descriptive analysis covers only a single country in a relatively short time window and, accordingly, a low number of observations. Hence, we cannot make causal inferences, nor can the results necessarily be generalized to other countries that might differ from Vietnam in many characteristics, such as the political system or cultural values. Our semistructured interviews face several common limitations of qualitative research approaches that may restrict the internal and external validity of the study.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses prior literature and develops our research questions. Section 3 introduces our methodology. Section 4 provides descriptive results by analyzing concurrent regulatory and macroeconomic developments. In Section 5, we outline our interviewees’ perceptions of the development of corporate governance and corruption in Vietnam as well as their perceptions of the association with economic prosperity. In Section 6, we summarize our results and conclude the paper.

2 Related literature and research questions

2.1 OECD principles of corporate governance and economic prosperity

2.1.1 International standards of corporate governance

International best practices of corporate governance are largely shaped by the OECD and the World Bank. In 1998, the OECD set milestones for global guidelines on corporate governance with its “OECD Principles of Corporate Governance,” (OECD, 1999b) which were revised in 2004 and updated to a G20 version in 2015 (OECD, 2015). The OECD principles ensure a basis for effective corporate governance through a framework based on five areas: the rights of shareholders, equitable treatment of shareholders, the role of stakeholders, disclosure and transparency, and responsibilities of the board. The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) recommends the OECD principles of corporate governance for emerging markets. In fact, the OECD principles serve as a blueprint when frontier or emerging countries enact corporate governance reforms. Although some researchers note that “it is unlikely that a single set of best practices exists for all firms” (Larcker & Tayan, 2015, p. 11; see also Andrews, 2010) or discuss the suitability of such practices for emerging economies (Berglöf & von Thadden, 1999; Siems & Alvarez-Macatela, 2014), OECD principles seem to be the de facto benchmark for “good” corporate governance (Jesover & Kirkpatrick, 2005; OECD, 1999a, 2011). For example, the World Bank produces “Enterprise Surveys” with a focus on the rights and treatment of shareholders and stakeholders (Mallin, 2012). Moreover, the World Bank publishes scorecards through its affiliate International Finance Corporation (IFC), which attempts to protect investors from inadequate corporate governance by publishing corporate governance ratings based on OECD principles (Larcker & Tayan, 2015).

2.1.2 Association between corporate governance and economic prosperity

Regarding the association of corporate governance and economic prosperity, La Porta et al. (1997), La Porta et al. (2000), Levine and Zervos (1998) and Rajan and Zingales (1998) find that higher levels of investor protection and more developed capital markets are associated with economic prosperity at the country level. At the firm level, Gombers et al. (2003) find stronger shareholder rights to be associated not only with higher firm value, higher profits, and higher sales growth but also with lower capital expenditures and fewer corporate acquisitions. It is also questioned whether capital market-based evidence can be generalized to emerging economies and whether OECD principles are suitable for emerging countries (Berglöf & von Thadden, 1999; Siems & Alvarez-Macotela, 2014). Emerging countries are often characterized by concentrated ownership structures, connection-based transactions and a dominant role of specific stakeholders, such as the state. These characteristics can induce an agency conflict between the controlling and minority shareholders (Young et al., 2008). Consequently, conflicts of interest between minority and majority shareholders and between firm managers and owners become more severe (Claessens & Fan, 2002). Building on these findings, Chen et al. (2011) argue and document that a commitment to OECD principles of corporate governance cannot attenuate the negative effect of controlling-shareholder expropriation on firm performance in a Chinese setting. To explain their results, the authors cite the OECD’s focus on the resolution of conflicts between shareholders and management but not on conflicts between controlling and minority shareholders. Additionally, they point to board directors who are typically not independent of controlling shareholders, while supervisory directors often have low status and weak power in a firm.

In addition to these predominantly empirical-archival papers, political science studies argue that the developmental state plays an important role in explaining economic growth (Haggard, 2018; Johnson, 1982; Stiglitz, 1998). A developmental state is characterized by, among other things, a concentration of power, authority, autonomy and competence in central political and bureaucratic institutions and can be found in many East Asian countries (Leftwich, 1995). In particular, the literature emphasizes the role of government intervention and industrial policy as well as the significance of strong states in explaining economic growth. Existing research also emphasizes the transformation of society and education. A shift to scientific ways of thinking and a narrowing technological gap are considered essential for explaining economic development (Stiglitz, 2002, 2003). Consequently, according to the developmental state literature, the adoption of international standards of corporate governance, the introduction of anti-corruption measures or the implementation of market-conforming policies in general play a weak role in economic growth (Moran, 1999; Önis, 1991; Stiglitz, 1998; Woo-Cumings, 1999).

2.1.3 Corporate governance quality in Vietnam

Considering the quality of governance in Vietnam, the state of convergence towards international standards, and in particular, the relation with economic prosperity, existing empirical findings are rather scarce. In McGee’s (2009) cross-country study of emerging countries based upon the OECD principles, Vietnam is ranked lowest in almost all areas. Nguyen (2008) concludes that Vietnam’s corporate governance system is characterized by two particular features, namely, that authority is concentrated in a few persons and that external supervision is nonexistent or very weak. He infers that this allows for abuse of power that negatively impacts the development of companies in particular and the whole economy in general. He thus suggests the need to improve corporate governance regulation and its actual enforcement. Minh and Walker (2008) conduct case studies on corporate governance issues in selected Vietnamese companies. They infer that inadequate securities regulation erodes investor protection, and they develop recommendations to address those weaknesses. In line with these findings, the IFC (2012) scorecard on the quality of corporate governance in 100 Vietnam-listed firms concludes as follows: “It is accurate to say CG practices in Vietnam remain more evident in rules than in application and implementation” (IFC, 2012, p. 14). The World Bank’s “Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC)” from August 2013 reached similar conclusions. While the ROSC acknowledges achievements such as the country’s rapid market growth since 2006 and the equitization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the report points to key obstacles; for example, “Overall, the corporate governance of many SOEs remains poor, with weaknesses in terms of transparency, board professionalism, and how the state acts as owner” (World Bank, 2013, p. 27). Owoeye & van der Pijl (2016) discuss recent corporate governance reforms in Vietnam and conclude that with the enactment of the Enterprises Law 2014, which came into force in July 2015, many of the challenges associated with corporate governance in Vietnam are being addressed. Those authors infer that the major challenge is the enforcement of the regulatory reforms, and they address the interrelation between corporate governance and corruption: “It is also important to take effective measures to address the issue of corruption as this is a serious challenge that could make the implementation of good corporate governance standards particularly daunting” (Owoeye & van der Pijl, 2016, p. 74).

2.1.4 Interrelation between corporate governance quality and corruption

In line with the argument by Owoeye & van der Pijl (2016), the empirical results by Wu (2005) indicate that good corporate governance can reduce corruption. Assuming a negative association between corruption and economic prosperity, Wu (2005) postulates that shareholders and investors in countries experiencing a high level of corruption may receive double dividends from improvements in corporate governance. At the country level, improvement in corporate governance may help a country with a high level of corruption to partially offset the negative impacts of the perception of corruption on the flow of capital (both financial and human). At the firm level, better corporate governance helps to reduce bribery practices, which can further increase firm valuation.

2.1.5 Development of research question 1

Prior research on the country and firm levels generally finds a positive association between compliance with OECD principles – or similar standards or proxies of “good corporate governance” – and performance indicators. However, some evidence for emerging countries casts doubt on whether those results can be generalized to developing and emerging economies with concentrated ownership structures and connection-based transactions. The developmental state literature emphasizes the prevailing role of government intervention, industrial policy and education as well as the significance of strong states and a transformation of society when explaining rapid economic developments in emerging countries.

In addition to the relation between corporate governance and economic prosperity, it is uncertain whether and how a high level of corruption might affect the relation between corporate governance and economic prosperity in developing and emerging countries. Because of these inconclusive empirical findings and the enduring debate on the suitability of the OECD principles of corporate governance for developing and emerging countries, we believe it is promising to complement a descriptive analysis primarily relying on archival data with qualitative insights from the field, followed by examining the role of corruption.

Research question 1: Is there an association between compliance with OECD principles and economic prosperity? If so, what are the channels through which compliance with OECD principles affects economic prosperity?

2.2 Corruption and economic prosperity

2.2.1 International view on corruption

The international perception of corruption is mainly shaped by Transparency International, which defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,” which might undermine “people’s trust in political and economic systems, institutions and leaders.” According to Transparency International, corruption “hinder[s] the development of fair market structures and distorts competition, which in turn deters investment” (Transparency International, 2017). Transparency International perceives measures against corruption to be “an integral part [of] sustainable growth” (Transparency International, 2015). To quantify the current level of corruption on a country level, Transparency International constructs and publishes a Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) on a yearly basis; the World Bank’s Control of Corruption Index (CCI) follows a similar approach. Consistent with Transparency International’s view, the OECD infers that measures against corruption and improvements to governance structures (which reduce opportunities for corruption) should be given high priority in a country’s structural reform agenda: “The subversive effects of corruption regarding general trust and government legitimacy prevail in both low and high quality governance scenarios, and their damage to overall efficiency and wellbeing is likely to be significant” (OECD, 2013, p. 36).

2.2.2 Association between corruption and economic prosperity

Prior research on the association between corruption and economic prosperity has produced puzzling results. As the OECD summarizes, empirical studies show that corruption negatively affects many of the drivers or determinants of economic growth. The OECD infers that the ultimate effect on growth is negative, despite the absence of a significant and robust direct correlation among these variables (OECD, 2013). Some empirical findings show a negative association between performance indicators and corruption at the country and/or firm level more directly. Still other papers question the direction of causality (e. g. Everett, Neu, & Rahaman, 2007).

For instance, several studies at the country level find that corruption – mostly measured by indices or scores – is negatively associated with performance indicators such as investments or growth rates (e. g. Ahlin & Pang, 2008; Borlea et al., 2017; Donadelli et al., 2014; Garmaise & Liu, 2005; Mauro, 1995; Mo, 2001; North, 1990; Romer, 1994; Shleifer & Vishny, 1993). According to Mo (2001), the most important channel through which corruption affects economic growth is political instability. Owoeye & van der Pijl (2016) point to a survey study by Hellman (2000) and suggest that corruption makes a country less competitive for investors and undermines the potential for economic prosperity. They infer that corruption not only limits the amount of FDI a country attracts but also undermines the quality of this investment. Studies that utilize country-level corruption measures based on scores are criticized because the scores might not necessarily reflect reality (for an overview, see Lopatta, Jaeschke, Tchikov, & Lodhia, 2017).

At the firm level, some studies suggest a negative association between corruption and several performance indicators. For instance, Nguyen and Van Dijk (2012) use data from the World Bank’s ‘‘Productivity and Investment Climate Enterprise Survey’’ and compare private firms with SOEs in Vietnam. Quantifying corruption by developing a corruption severity perception survey, they find that corruption harms economic growth because it favors the state sector at the expense of the private sector. Using survey data for Vietnam, Rand and Tarp (2012) find that bribe payments are associated with several firm characteristics and negatively affect firm growth.

Several studies have produced mixed or inconclusive results (e. g. Li, Xu, & Zou, 2000; Sharma & Mitra, 2015). Some studies find that corruption is less harmful in some countries than in others. According to the studies by Méndez and Sepúlveda (2006) and Huang (2016), corruption may be less harmful in developing countries and in countries that are not considered politically free. Other studies even find a positive association between corruption and performance indicators. There is a stream of literature suggesting that corruption improves efficiency and contributes to growth. Those studies argue that corruption might add to economic growth in two ways: “(i) corrupt practices such as ‘speed money’ would enable individuals to avoid bureaucratic delay; and (ii) government employees who are allowed to levy bribes have incentives to work harder and more efficiently” (Nguyen & Van Dijk, 2012, p. 2937 referring to Leff, 1964; Huntington, 1968; Lui, 1985; see also Cheung, 2005). In line with this reasoning, Zeume (2017) exploits the U.K. Bribery Act 2010 as a shock to U.K. firms’ cost of doing business and finds that U.K. firms operating in high-corruption countries experience a decline in firm value, while their non-U.K. competitors in these countries experience an increase in value. He concludes that bribes facilitate doing business in certain countries. In the Vietnamese setting, the empirical findings of Nguyen et al. (2016) also tend to support a positive association between corruption and firm performance as measured by innovation. Furthermore, a few studies explicitly examine the characteristics of corrupting firms. For instance, Sahakyen & Stiegert (2012) analyze survey data from Armenian businesses and find that corruption is perceived as favorable among firms that (1) do not face significant competition, (2) are relatively larger, and (3) are younger.

2.2.3 “East Asia Paradox”

Some papers refer to an “East Asia paradox” because countries in China and Southeast Asia show exceptional growth records despite having thriving cultures of corruption. Wang and You (2012) argue and find that there is a substitution relationship between corruption and financial development on firm growth. Thus, corruption appears not to be a vital constraint on firm growth in underdeveloped financial markets. However, pervasive corruption deters firm growth in more developed financial markets (Wang & You, 2012). Somewhat consistent with this notion, Aidt et al. (2008) build an analytical model and argue that in a regime with high-quality political institutions, corruption has a substantial negative impact on growth, whereas in a regime with low-quality institutions, corruption has no impact on growth.

2.2.4 Development of research question 2

Reviewing prior literature, we conclude that prior research on the country and firm levels produced puzzling results and divergent theories about the association between corruption and economic prosperity as well as about the channels through which corruption might affect economic prosperity. In summarizing the state of research, the OECD comes to similar conclusions and notes that corruption negatively affects many of the drivers or determinants of economic growth, suggesting that the

fact that corruption appears to be less damaging to growth in an environment of poor public sector governance does not justify complacency by policy makers. Rather, it provides a strong signal that improving governance structures (which will in turn reduce corruption opportunities) should be given high priority in the country’s structural reform agenda. The subversive effects of corruption regarding general trust and government legitimacy prevail in both low- and high-quality governance scenarios, and their damage to overall efficiency and wellbeing is likely to be significant. (OECD, 2013, p. 36)

In light of the puzzling empirical results and the persistently negative views on corruption, we believe it is promising to complement a descriptive analysis primarily relying on archival data with qualitative insights from the field in order to obtain a deeper understanding.

Research question 2: Is there an association between corruption and economic prosperity? If so, what are the channels through which corruption affects economic prosperity?

3 Methodological approach

3.1 Case study and triangulation

To analyze the association among corporate governance, corruption and economic prosperity, we follow a case study approach and employ triangulation. Triangulation is a method of cross-checking and cross-referencing data from multiple sources to search for regularities in the research data (Vidovich 2003). In particular, we use between-methods triangulation, which according to Smith (2015) combines different results from the application of different research methods and may include quantitative and qualitative approaches. More specifically, we utilize data triangulation. We examine regulatory developments and related archival data and complement this analysis with semistructured interviews. In doing so, we examine a single case but use multiple units of analysis.

3.2 Descriptive analysis of regulatory and macroeconomic developments

We start our analysis by reviewing Vietnam’s regulatory reforms that aim for convergence in the corporate governance framework towards international standards and fighting corruption. These reforms have been implemented since the “Doi Moi” policy was started in 1986. Subsequently, we link these observations with the concurrent macroeconomic development. Namely, we analyze the development of gross domestic product (GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) during this time of major regulatory reforms and employ them as a proxy for economic prosperity. Beyond this qualitative observation of simultaneous developments, we additionally perform a quantitative analysis. We utilize quantitative measurement approaches developed and published by the World Bank and Transparency International starting from 1996 and 1998, respectively, and analyze the development of those corporate governance quality and corruption indicators through 2016. From the World Bank’s “World Development Indicators” database, we obtain six scores that measure governance quality, the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). Namely, we rely on the indices Voice and Accountability (VAI), Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (PSI), Government Effectiveness (GEI), Regulatory Quality (RQI), Rule of Law (RLI), and Control of Corruption (CCI). Details on the calculation of the six scores are provided in the appendix.

From Transparency International, we use the corruption perceptions index (CPI). Notably, the CPI is not designed to allow country scores to be compared over time, as the index draws on a country’s rank in the original data sources rather than its score. Accordingly, the rank delivers only relative information. To mitigate this issue, in our descriptive analysis, we also examine the relative rank, i. e. the rank in a given year’s report divided by the number of countries included in that year’s report. Details on the CPI calculation are provided in the appendix.

To gain a deeper understanding of the development of the individual indices, the associations among them and their association with macroeconomic development (GDP and FDI), we analyze the development of the indexes over time followed by a univariate analysis of pairwise correlations. However, as we conduct a case study on a single country and the available observations are therefore limited, we refrain from performing multivariate analysis.

3.3 Semistructured interviews with stakeholders

Similar to our descriptive analysis, most prior research is conducted at an aggregated level and analyzes publicly available firm or survey data. Little is known about the perceptions of individual stakeholders. To address this research gap and to obtain a more detailed understanding, particularity of the determinants of our descriptive results, we complement our descriptive analysis with a semistructured interview approach. Semistructured interviews emerge as more appropriate than structured, unstructured or focus group interviews because expert knowledge and attitudes provide background information and business insights related to our research questions – information that interviewees are unlikely to share when they are in a group or are asked overly specific questions. This approach enables the interviewer to choose trajectories by building on what is said by the interviewee (Bryman, 2012). Using a list of open questions allows the interviewer to be prepared and appear competent during the interview (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). We composed the list of open questions not only to gather insights into the interviewees’ perceptions regarding our research questions but also to gain background knowledge about the interviewees’ arguments, opinions, and experiences. The questions are roughly structured on the basis of the OECD principles of corporate governance and address the following areas in this order: general economic performance and outlook in Vietnam, suitability of OECD principles and ratings for emerging countries, the rights of shareholders, equitable treatment of shareholders, the role of stakeholders, disclosure and transparency, responsibilities of the board, and a final overall evaluation of the quality of corporate governance in Vietnam (see the appendix for details). We did not include questions that directly address the matter of corruption because we expected interviewees to be more open to disclosing their perceptions and experiences when asked about corruption in follow-up questions. Because the interviews were conducted by a single interviewer who had to guide, follow and participate in the interview, we followed general practice by tape-recording the interviews and later transcribing them for analysis. The transcripts were analyzed by the two authors.

We conducted eleven interviews with experts from several industries in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. To randomize our sample, we gained access to interviewees through a combination of judgment sampling and different social networks. Company data and candidates were drawn from the social business networks LinkedIn and Xing, using the search words ‘Corporate Governance’ and ‘Vietnam’. Further, we obtained data through Vietnam Business TV (www.vietnambusiness.tv), the Vietnam Business Forum (www.vccinews.com) and AmCham Vietnam (www.amchamvietnam.com). Snowball sampling played a subordinate role, and the number of snowball-sampled experts was deliberately kept low because of the inherent risk of overrepresentation of a single networked group. We contacted potential candidates via e-mail. We refrained from sampling specific features, such as company size, market share, origin or industry, in order to better achieve randomness. In sum, we contacted 100 firms or individuals, of whom eleven agreed to participate. While the whole sample is dominated by three large industry groups, (i) industrial goods and services, (ii) consulting, and (iii) law and audit, the sample of interviewees (final sample, see Table 1) is mainly characterized by law and audit, although the predominant groups remain. We could not obtain any participation from banks and real estate companies. Nevertheless, we consider the agreement rate of 11 % to be within the acceptable range. For instance, Phan, Mascitelli, and Barut (2014) and Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal (2005) suggest that a common response rate for comparable long questionnaires ranges from 8 to 10 %. According to Guest et al. (2006), saturation is reached after twelve interviews, and major themes are represented after six.

Computation of the final sample of semistructured interviews.

| Industry Group | Contacted | Responded | Declined | Agreed | Response Rate | Agreement Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Goods and Services | 26 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 19 % | 8 % |

| Consulting | 25 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 12 % | 8 % |

| Law and Audit | 16 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 50 % | 31 % |

| Real Estate | 11 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 27 % | 0 % |

| Banks | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 25 % | 0 % |

| IT and Technology | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 33 % | 17 % |

| Other | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 13 % | 13 % |

| ∑ Ø | 100 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 24 % | 11 % |

To reduce bias, we assured the interviewees that we would keep their personal information confidential and refrain from publishing any information that would allow others to identify them. All interviewees were working in management positions and had an average of nine years of professional experience in Vietnam (see Table 2). Accordingly, they were able to assess the changes and developments that have occurred in recent years. Eight interviewees were non-Vietnamese nationals, and we considered them “internationals” or “expats”; three interviewees were Vietnamese nationals, and we considered them “locals.” Our international interviewees were all nationals of EU member states. The interview period lasted from October 19, 2016, to November 24, 2016. We conducted the interviews in English, and they lasted thirty-six minutes on average. Due to limitations of time and geographical coordination, two interviews were conducted via Skype. In line with prior research, our results are based on reconciled responses and further comments in subject transcripts (Cohen, Krishnamoorthy, & Wright, 2002).

Final sample of semistructured interviews and background information on interviewees.

| Number | Interviewee background | Interview information | Interviewee Code | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Rank | Professional experience in Vietnam (Years)* | Gender | Background | Duration (Minutes) | Method | Recording | Language | (Nr-Background-Industry) | |

| 1 | Law and Audit | Associate Partner | 5 | Male | International | 00:27:59 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 1-I-L |

| 2 | Industrial Goods and Services | Country Manager | 7 | Male | International | 00:36:05 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 2-I-I |

| 3 | Industrial Goods and Services | Country Manager | 4 | Male | International | 00:23:07 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 3-I-I |

| 4 | Law and Audit | Managing Director | 10 | Male | International | 00:44:53 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 4-I-L |

| 5 | Consulting | Managing Director | 6 | Female | Local | 00:48:25 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 5-L-C |

| 6 | Other | Managing Director | 5 | Male | International | 00:36:32 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 6-I-O |

| 7 | Law and Audit | Associate | 13 | Female | Local | 00:37:37 | Skype | Taped | English | 7-L-L |

| 8 | Consulting | Chief Executive Officer | 25 | Male | International | 00:40:00 | Skype | Taped | English | 8-I-C |

| 9 | IT and Technology | General Manager | 8 | Male | International | 00:35:23 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 9-I-T |

| 10 | Law and Audit | Associate | 10 | Female | Local | 00:45:49 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 10-L-L |

| 11 | Law and Audit | Managing Director | 6 | Male | International | 00:31:06 | Face-To-Face | Taped | English | 11-I-L |

-

*Years of working experience for interviewees with local background.

4 Results of descriptive analysis of regulatory and macroeconomic developments

4.1 Reforms on the corporate governance framework and anti-corruption measures

We begin our descriptive analysis with a review of major regulatory developments and subsequently examine quantitative measures and descriptive statistics.

Before starting the still ongoing process of regulatory reforms, Vietnam’s centrally planned economic regime was based on a Marxist-Leninist model (Nguyen & Richard, 2011). By 1985, economic crises and failures, as well as the decline of the Soviet Union, facilitated inflation, famines, and food shortages and created a comprehensive socioeconomic crisis (Esterline, 1987). In need of international assistance in the forms of capital and technology, Vietnam launched a process of economic renovation and adopted an “open door” policy to attract foreign investors (Nguyen & Richard, 2011). While the credo “reform or collapse” was championed (Turley & Selden, 1993), in 1986, the Sixth Communist Party Congress abandoned the centralized economy and paved the way for a transitional process en route to adopting a market-based economy (Nguyen & Tran, 2012; Odell & Castillo, 2008).

Table 3 depicts the major regulatory reforms. As a starting point and a major step, in 1990, a company law introduced limited liability companies (LLCs) and shareholding companies (SCs). In 2003, the legal framework on accounting was reformed, and in 2005, Vietnam enacted an anti-corruption law. Since 2006, Vietnam has allowed foreign investors to operate businesses, and regulations on public and listed companies have been imposed (Minh & Walker, 2008). In 2007, Vietnam introduced a Corporate Governance Code, which was amended in 2012. Since 2012, the listing rules of the Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi stock exchanges have required increased levels of disclosure (Centre for Asia Private Equity Research Ltd, 2015) and have responded to global pressure for independent directors (IFC, 2012). In addition to these legal reforms, a process of privatizing SOEs resulted in the increasing importance of the private sector and publicly traded firms (for an overview, see Nguyen & Van Dijk, 2012). Nonetheless, the unofficial securities market is still considered significantly larger than the formal market, and state ownership remains extensive. Institutions responsible for the regulation, enforcement and development of the capital market are considered to have limited capacity and resources, allowing for related-party transactions and corruption (Minh & Walker, 2008). In 2015, Vietnam tightened the regulation on corruption and corporate governance with the Penal Code 2015 and the revised Law on Enterprise 2014. The former is in line with the Vietnamese government’s repeated commitments to reduce corruption (World Bank & MPI, 2016); the latter introduced the definition and role of an independent director, allowing limited liability companies and joint stock companies to have more than one legal representative and reducing the quorum for convening a members’ council meeting and voting thresholds required to approve resolutions. According to Owoeye & van der Pijl (2016), the law addresses major weaknesses in the Vietnamese corporate governance framework.

Major regulatory reforms since 1990.

| Year | Laws/Regulations | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Company Law | – Introduction of limited liability companies (LLCs) and shareholding companies (SCs) |

| 1990 | Private Enterprise Law | – Legal recognition of private companies and their equal rights in business |

| 1995 | SOE Law | – Legal basis for the operation of SOEs with more freedom to use capital, make operational decisions and do business with other types of companies |

| 1996 | Law on Cooperatives | – Legal basis for cooperatives in Vietnam, including principles of operation and management |

| 1997 | Law on Credit Institutions | – Legal basis for credit institutions in Vietnam |

| – Prerequisites of director board and supervisory board to avoid role duality and cross ownership | ||

| – Mandatory requirements for internal inspection and auditing system | ||

| 1999 | Law on Enterprises | – Introduction of partnerships and one-organization-owned LLCs |

| – Limitations on the number of shareholders of LLCs | ||

| 2000 | Law on Insurance | – Legal basis for insurance companies, including accounting, financial statement disclosure, and transparency |

| 2003 | Law on Cooperatives | – Introduction of cooperative alliance |

| 2003 | Law on Accounting | – Legal basis for accounting, including information disclosure |

| – Requirements for accountants to avoid insider trading and fraud | ||

| 2005 | Anti-Corruption Law | – Legal basis for anti-corruption among government officials in general and managers/directors/representatives of SOEs in particular |

| 2005 | Law on Enterprises | – Rights of foreign investors to choose among different types of business |

| – Salary transparency of directors – Disclosure of director board and supervisory board members holdings in other companies |

||

| – More detailed regulations on obligations of directors/managers/supervisors | ||

| – Converting requirement of SOEs’ legal form in maximum 4 years | ||

| – Regulations on company groups | ||

| 2006 | Law of Securities | – Public and listed company definitions |

| – Disclosure regulations | ||

| 2007 | Decision 12 on Corporate Governance Code for Listed Companies | – Definition of corporate governance |

| – Regulations on compositions of director board and supervisory board | ||

| – Disclosure regulations, including compensation and beneficial transactions of directors, CEO and supervisors | ||

| – Regulations on conflicts of interest | ||

| 2007 | Decision 15 on Model Charter for Listed Companies | – Model charter for listed companies |

| 2010 | Law on Credit Institutions | – Mandatory requirement of outside directors |

| – Restrictions of ownership percentage | ||

| 2012 | Circular 121 on Corporate Governance Code for Public Companies | – Increase of the minimum number of director board members |

| – Mandatory requirement of nonexecutive directors on board (at least 1/3) | ||

| – Particular regulations for large public companies and listed companies | ||

| 2012 | Circular 52 on Disclosure Rule | – Disclosure rules for public companies, issuers, security companies, stock exchanges and other relevant parties. |

| 2012 | Law on Cooperatives | – Detail definition of cooperative alliance |

| – Rights of foreign participants | ||

| – Stricter regulations on income distribution | ||

| 2012 | Revised Law on Anti-Corruption | – Transparency in SOE management |

| – Declaration and verification of personal properties | ||

| – Regulations on the recruitment and appointment | ||

| 2014 | Law on Investment | – Abolishment of foreign ownership restrictions, except for restricted industries |

| 2014 | Revised Law on Enterprises | – Two-term limit for chairman, members of director board/supervisory board or other key management roles |

| – Addition of management and operation model | ||

| – Decrease of quorum and voting requirements | ||

| – Amendments of public disclosure on related persons’ holdings | ||

| – Reduction of large transaction threshold | ||

| – Prohibition of chairman-director duality in enterprises, in which state holds more than 50 % of voting power | ||

| – Increase of the number of company representatives | ||

| 2014 | Law on Management and Utilization of State Capital Invested in Enterprise’s Manufacturing and Business Activity | – Restructuring of state capital in the enterprise |

| – Regulations on evaluation, rating, reporting and disclosure of activities of enterprises of which 100 % charter capital is held by the state | ||

| – Regulation on director compensation and income distribution | ||

| 2015 | Penal Code | – Introduction of abuse of power |

| – Non-application of time limits for criminal prosecution | ||

| – Extension of corruption-related offences to private sector | ||

| – Introduction of corporate criminal liability for certain crimes | ||

| – Higher penalty application for corruption-related offences | ||

| – Quantification of prior qualitative phrases (criminal consequences, etc.) | ||

| 2015 | Law on Accounting | – Introduction of fair value accounting principle |

| – Specification of agencies who have the authority to decide on carrying out accounting inspections | ||

| – Supplement of the code of ethics |

||

| 2017 | Decree 71 on Corporate Governance for Public Companies | – Amendment of the number of board director members |

| – Limited number of companies in which board members simultaneously take similar positions | ||

| – Abolishment of chairman-director duality | ||

| – Mandatory requirement of quarterly meeting of director board | ||

| – Amendments of conflicts of interest |

Along with the regulatory reforms, Vietnam has simultaneously made various commitments to globalization and international trade. As summarized in Table 4, the country is a member of ASEAN, APEC, and WTO, among others. Moreover, Vietnam has signed several bilateral trade agreements and is waiting for several agreements to take effect.

Major commitments to international trade since 1995. Information on trade agreements was retrieved from the Asia Regional Integration Centre.

| Year | Trade Agreements/Commitments | Status |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Member of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) | Effective |

| 1996 | Member of ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) | Effective |

| 1996 | A founding member of Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) | Effective |

| 1998 | Member of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) | Effective |

| 2000 | Bilateral trade agreement with the USA | Effective |

| 2004 | ASEAN-People’s Republic of China Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement | Effective |

| 2006 | ASEAN-Republic of Korea Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement | Effective |

| 2007 | Member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) | Effective |

| 2008 | ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement | Effective |

| 2008 | Vietnam-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement | Effective |

| 2009 | ASEAN-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement | Effective |

| 2009 | ASEAN-Australia and New Zealand Free Trade Agreement | Effective |

| 2011 | Vietnam-Chile Free Trade Agreement | Effective |

| 2015 | Vietnam-Laos Free Trade Agreement | Effective |

| 2015 | Vietnam-South Korea Free Trade Agreement | Effective |

| 2015 | Vietnam-Eurasian Economic Union Free Trade Agreement | Effective |

| 2015 | EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement | Negotiations concluded |

| 2015 | ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) | Effective |

| 2017 | ASEAN-Hong Kong, China Free Trade Agreement | Signed but not yet in effect |

| 2018 | Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) | Signed but not yet in effect |

4.2 Concurrent macroeconomic development

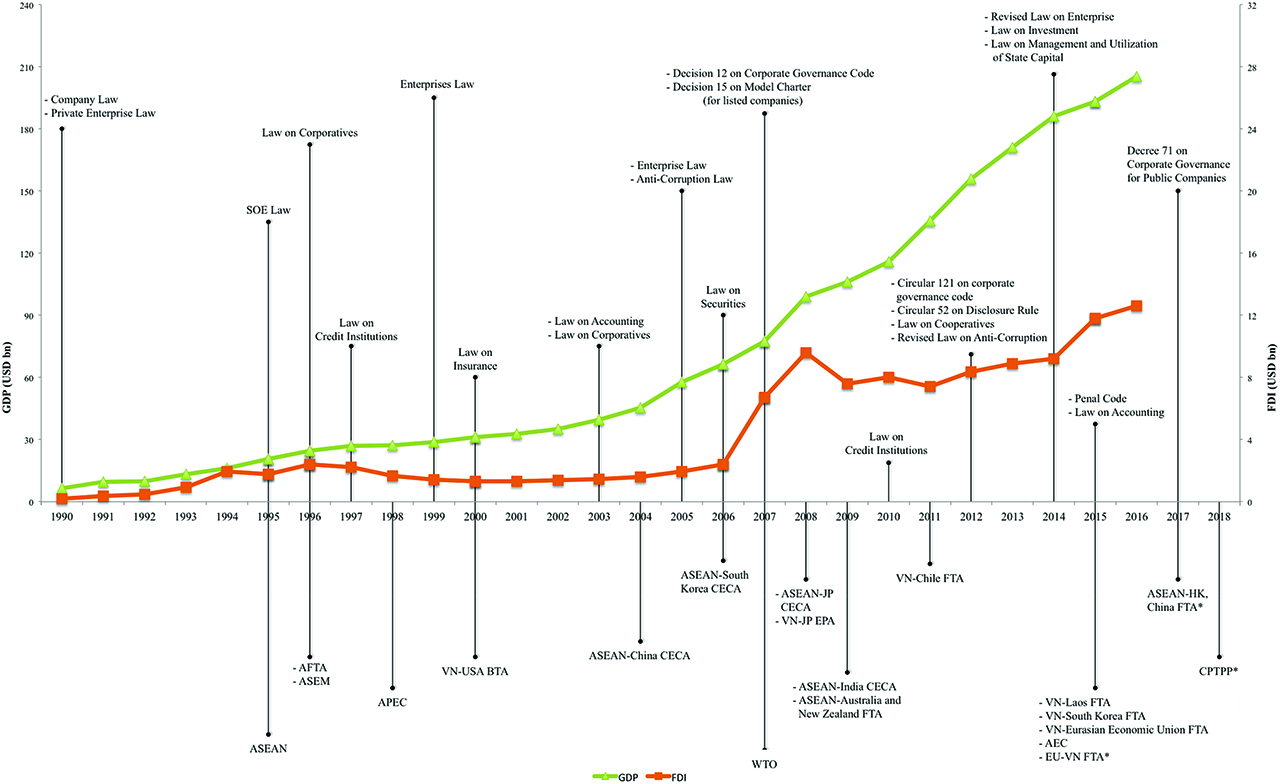

Regarding the concurrent macroeconomic development in times of major regulatory reforms and commitments to international trade, prior literature emphasizes that without political regime change, Vietnam managed to secure macroeconomic stabilization of its GDP growth and a consistently decreasing inflation rate without any significant international aid from financial institutions, such as funds from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Nguyen & Tran, 2012). Figure 1 visualizes the macroeconomic development since 1990 and integrates the concurrent legal reforms and trade agreements discussed above. Although it is impossible to draw causal inferences from those observations, we find a concurrent development of legal reforms and our macroeconomic proxies for economic prosperity. As depicted in Table 5, from 1996 to 2016, Vietnam’s GDP growth is persistently above 5 % according to the World Bank’s definition of GDP growth. During the same time, FDI was much more volatile but more than quadrupled from 1996 to 2016.

Illustration of the developments in macroeconomic data during the time of major regulatory reforms and commitments to international trade from 1990 to 2016. The data are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database, and information on trade agreements was retrieved from the Asia Regional Integration Centre.

Macroeconomic data, corporate governance quality, and corruption indicators between 1996 and 2016. The gross domestic product (GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. The estimates for the six analyzed Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), VAI, PSI, GEI, RQI, RLI, and CCI, are also drawn from this database and range from −2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong) governance performance. The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is drawn from Transparency International. The CPI rank shows Vietnam’s position in the CPI ranking in a given year. The CPI relative rank is calculated by Vietnam’s CPI rank in a given year divided by the number of countries included in that year’s Transparency International CPI report. Before 2002, some of the data were provided only every two years. More detailed explanations on the variables and their calculation can be found in Appendix A and Appendix B.

| Variable/Year | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP (Mio. USD) | 24,657 | 27,210 | 31,173 | 35,064 | 39,553 | 45,428 | 57,633 | 66,372 | 77,414 | 99,130 | 106,015 | 115,932 | 135,539 | 155,820 | 171,222 | 186,205 | 193,241 | 205,276 |

| GDP growth according to World Bank’s definition (annual %) | 9.34 | 5.76 | 6.79 | 6.32 | 6.90 | 7.54 | 7.55 | 6.98 | 7.13 | 5.66 | 5.40 | 6.42 | 6.24 | 5.25 | 5.42 | 5.98 | 6.68 | 6.21 |

| GDP growth raw data (annual %) | 18.91 | 1.36 | 8.68 | 7.28 | 12.80 | 14.85 | 26.87 | 15.16 | 16.64 | 28.05 | 6.94 | 9.35 | 16.91 | 14.96 | 9.88 | 8.75 | 3.78 | 6.23 |

| FDI (Mio. USD) | 2,395 | 1,671 | 1,298 | 1,400 | 1,450 | 1,610 | 1,954 | 2,400 | 6,700 | 9,579 | 7,600 | 8,000 | 7,430 | 8,368 | 8,900 | 9,200 | 11,800 | 12,600 |

| FDI growth raw data (annual %) | 34.52 | −24.73 | −8.07 | 7.69 | 3.57 | 11.03 | 21.37 | 22.82 | 179.17 | 42.97 | −20.66 | 5.26 | −7.13 | 12.62 | 6.36 | 3.37 | 28.26 | 6.78 |

| VAI | −1.09 | −1.35 | −1.24 | −1.45 | −1.47 | −1.34 | −1.40 | −1.54 | −1.53 | −1.50 | −1.48 | −1.50 | −1.46 | −1.42 | −1.37 | −1.37 | −1.36 | −1.41 |

| PSI | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.25 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.17 |

| GEI | −0.58 | −0.38 | −0.44 | −0.44 | −0.45 | −0.48 | −0.23 | −0.25 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.27 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| RQI | −0.60 | −0.69 | −0.73 | −0.72 | −0.56 | −0.56 | −0.60 | −0.62 | −0.56 | −0.62 | −0.62 | −0.62 | −0.60 | −0.67 | −0.64 | −0.59 | −0.48 | −0.45 |

| RLI | −0.48 | −0.45 | −0.36 | −0.64 | −0.58 | −0.57 | −0.32 | −0.52 | −0.49 | −0.47 | −0.54 | −0.59 | −0.54 | −0.55 | −0.51 | −0.36 | −0.34 | 0.05 |

| CCI | −0.49 | −0.47 | −0.57 | −0.57 | −0.50 | −0.73 | −0.72 | −0.75 | −0.63 | −0.71 | −0.54 | −0.62 | −0.61 | −0.53 | −0.48 | −0.44 | −0.43 | −0.40 |

| CPI | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 33 | |

| CPI rank | 74 | 76 | 85 | 100 | 102 | 107 | 111 | 123 | 121 | 120 | 116 | 112 | 123 | 116 | 119 | 111 | 113 | |

| CPI relative rank | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

4.3 Development of quantitative measures for corporate governance quality and corruption

Table 5 also depicts the development of the World Bank’s governance quality indices. Analyzing the time series data, we find improvements in the scores for the GEI, RQI, and RLI. Meanwhile, the VAI and PSI scores decreased. Accordingly, we conclude that regulatory reforms aligned the corporate governance framework with international standards as the World Bank’s governance quality indices emphasize some improvements in corporate governance quality.

Regarding changes in corruption, the World Bank’s CCI shows a volatile trajectory with an overall decrease in the period from 1996 to 2016. Transparency International’s CPI shows persistently high levels of corruption with some improvements between 1998 and 2016. Because the between-year comparability of the CPI is limited, we draw this conclusion primarily from Vietnam’s relative CPI rank.

4.4 Correlation analysis

In the next step, we analyze pairwise correlations among the discussed indices for governance quality, corruption and our proxies for economic prosperity. As shown in Table 6, we find a positive correlation among governance quality indices and GDP and FDI, while we find a negative relation with corruption. Moreover, we find a negative association between two governance quality indices and the relative CPI rank.

Pairwise correlation analysis of macroeconomic data, corporate governance quality, and corruption indicators between 1996 and 2016. P-values are reported in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 0.1, 0.05, and 0.01 levels, respectively. The gross domestic product (GDP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. The estimates for VAI, PSI, GEI, RQI, RLI, and CCI are also drawn from this database. The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is drawn from Transparency International. The CPI relative rank is calculated by Vietnam’s CPI rank in a given year divided by the number of countries included in that year’s Transparency International CPI report. More detailed explanations on the variables and their calculation can be found in Appendix A and Appendix B.

| GDP | FDI | VAI | PSI | GEI | RQI | RLI | CCI | relative CPI rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FDI | 0.951*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.0) | |||||||||

| VAI | −0.206 | −0.249 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.413) | (0.319) | ||||||||

| PSI | −0.629*** | −0.614*** | 0.360 | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.142) | |||||||

| GWI | 0.855*** | 0.833*** | −0.389 | −0.556** | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.110) | (0.017) | ||||||

| RQI | 0.508** | 0.528** | −0.101 | −0.491** | 0.586** | 1.000 | |||

| (0.031) | (0.024) | (0.689) | (0.038) | (0.011) | |||||

| RLI | 0.451* | 0.433* | 0.208 | −0.093 | 0.588** | 0.545** | 1.000 | ||

| (0.060) | (0.072) | (0.406) | (0.712) | (0.010) | (0.019) | ||||

| CCI | 0.466* | 0.409* | 0.368 | −0.299 | 0.282 | 0.213 | 0.402* | 1.000 | |

| (0.051) | (0.092) | (0.132) | (0.229) | (0.257) | (0.397) | (0.098) | |||

| relative CPI rank | −0.73*** | −0.725*** | 0.438* | 0.401 | −0.632*** | −0.648*** | −0.183 | 0.124 | 1.000 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.078) | (0.111) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.482) | (0.635) |

Specifically, GDP is positively and significantly correlated with GWI, RQI, and RLI and is highly and positively correlated with FDI. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that the correlations between FDI and the governance indices show a pattern similar to the pattern of correlation between GDP and the governance quality indicators. Namely, GWI, RQI, and RLI are positively and significantly correlated with FDI. However, concerning VAS and PSI, we find negative but partly nonsignificant correlations with GDP and FDI.

Regarding corruption, we find a negative and significant association with GDP and FDI. As the CCI measures the level of control of corruption and, consequently, a higher score indicates less corruption, we find that the CCI is positively associated with GDP and FDI. Since higher relative CPI ranks indicate higher levels of corruption, the correlations with GDP and FDI show a negative sign. Considering the interaction between governance and corruption, we find a negative and significant association between the relative CPI rank and GEI and RQI as well as a positive and significant association between CCI and RLI.

4.5 Discussion

Our descriptive analysis reveals that regulatory reforms towards the adoption of international standards of corporate governance occurred simultaneously with improvements in macroeconomic measures for economic prosperity. The regulatory reforms are also accompanied by improvements in quantitative measures of governance quality. In line with many prior studies, our correlation analysis confirms the positive and significant association between corporate governance quality and economic prosperity.

Regarding corruption, we find that Vietnam shows positive macroeconomic development despite exhibiting high levels of corruption. While this result might be interpreted in line with prior literature stipulating an “East Asia paradox,” our time series analysis shows a negative correlation among corruption and our macroeconomic measures for economic prosperity. Moreover, the correlation analysis shows, to some extent, that higher levels of corruption are linked with weaker regulatory quality and law enforcement, which might weaken the positive association between corporate governance and economic prosperity.

When interpreting our findings, we have to consider several limitations. We rely on a limited number of observations from a single country and a simple analysis of pairwise correlations. Therefore, it is impossible to draw causal inferences from our results or to gain insights into the direction of causality. To gain a deeper understanding, we complement our descriptive analysis with semistructured interviews in the next step.

5 Results of semistructured interviews

5.1 OECD principles and economic prosperity

5.1.1 General perceptions of compliance with OECD principles

We began the interviews by capturing views on the current economic situation and outlook in Vietnam. After these opening questions, the interviewer directed the discussion to the interviewee’s general perceptions of OECD principles.

The results show that interviewees with an international background consider compliance with OECD principles to be a prerequisite for attracting FDI and participation in international business. Moreover, interviewees consider OECD principles-based ratings to be an incentive to reform the current corporate governance framework to conform to international standards. For instance, as interviewee 9-I-T outlined,

Vietnam is interfering globally and tries to compete on an international basis, the international ranking is just logical. Although the level of development has to be taken into account, I strongly support the idea because the publishing of these numbers will encourage the government to accelerate the reforms. (9-I-T)

However, 4-I-L added that international standards and ratings might not be appropriate for Vietnam or at least not accepted by the local business community:

[I]t is unfair, but it possibly helps Vietnam to improve its own system – on which, until now, they have done a good job. And they will always go their own way. They won every war, so why should they change anything suddenly because of some overseas pressure? Which dominates the perception of the people, it is a different attitude than ours. (4-I-L)

Interviewee 6-I-O noted that Vietnam might not be important enough to justify divergence from international standards, even if international rating criteria are not completely suitable for Vietnam:

To create more investors in the future, Vietnam should create comfortable circumstances for foreign companies and set conditions for sustainable investments […] Of course, Vietnam has to consider global principles. Although they will go their own way, honestly, they are not a superior market force, like China, so if they want to participate globally, they have to adapt their system to some extent. […] Regarding the results of these ratings: In the case of an emerging country, they might provide a distorted picture from the overall conditions here. So the results have to be obtained with caution. (6-I-O)

In line with the latter argument, interviewee 2-I-I also emphasized that a poor rating might not necessarily correlate with weak business prospects at the country level:

[T]he idea behind the scorecard is to get a view on best practice, and it also includes ‘our’ principles of how to operate a company. Vietnam has a totally different perspective and varying standards. Nevertheless, scorecards […] should consider these differences and should also include cultural aspects – and evaluate it again. Of course, Vietnam wants to develop like an industrial country and wants to participate globally, so they should agree with some standards, but we should help them to do so rather than rate them [as] insufficient. Additionally, it is important to obtain local requirements and whether they are fulfilled or not. A bad rating, based on global principles, won’t tell you much about the actual possibilities Vietnam can offer to the world. (2-I-I)

Interviewees with a Vietnamese background answered similarly and emphasized the importance of compliance with OECD principles if Vietnam seeks to participate in international trade. For example, according to interviewee 7-L-L, compliance with OECD principles and corresponding rankings “might be the key issue for foreign investment” (7-L-L). Interviewee 5-L-C stated, “we have to change a lot, as we are trying to participate more globally” (5-L-C).

5.1.2 Discrepancies between compliance on paper and in practice

During our interviews, almost all interviewees pointed to a discrepancy between the adoption of international standards of “good” corporate governance on paper and the application of those standards in practice; specifically, they cited a lack of enforcement and enforceability. For instance, interviewee 1-I-L pointed out that convergence towards international standards does not guarantee consistent application: “Vietnam is already part of the ASEAN Economic Community, since the first of January 2016, but it remains unclear whether all these relevant local and domestic requirements will be applied in practice” (1-I-L). Interviewee 9-I-T made a similar comment and emphasized the importance of enforcement mechanisms for attracting FDI: “I think the codes are decent and working well – but the enforcement of these rules is the crucial fact. […] [In] order to attract foreign investors, strengthening the legal enforcement is crucial” (9-I-T). However, during the course of our interviews, we also became aware of large differences among private, public, and state-owned enterprises, as well as regional differences. For instance, interviewee 8-I-C distinguished between public and private companies:

The question might not be if you are aware of your rights – rather, are you able to enforce them? As […] a foreign investor in Vietnam, I think you are better protected if you invest in listed companies. The corporate governance standards on stock market-listed companies are pretty high. Like a copy-paste model of Singapore or Hong Kong. But if you go into private-equity, venture-capital type of companies, you need to do your homework like due diligence; otherwise, it won’t be possible to know what kind of investment you are participating in, nor will you be aware of your rights. (8-I-C)

Other interviewees pointed to large differences with respect to industries and regions:

We have to make a very strict separation between the north and the south of Vietnam. There is a significant difference between the Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City–metropolitan areas. Ho Chi Minh City remains very capitalistic, very straight forward and very investor-friendly, while Hanoi remains rather communistic and governmental oriented. (1-I-L)

Additionally, interviewee 2-I-I emphasized the importance of the region:

But it also depends on the reason, the kind of business and the location. For example, trading in Ho Chi Minh City is more developed than in rural areas, like [location anonymized by the authors], for example, where we also trade. An overall rating for Vietnam is hardly measurable without considering different phases of development in each province. (2-I-I)

5.1.3 Association between compliance with OECD principles and economic prosperity

We captured the interviewees’ perceptions regarding the association between compliance with OECD principles and economic prosperity in the first one-third of our interviews, namely, after capturing the interviewees’ perceptions of Vietnam’s general economic performance and outlook as well as their perceptions regarding the applicability of OECD principles and rankings to emerging countries. We first directed the interview towards the relation between corporate governance quality and firm performance as a disaggregated measure before talking about the wider picture. This approach reduced the possibility that interviewees would simply confirm a positive correlation because they considered such confirmation to be an expected and accepted behavior. Nevertheless, we were still able to choose and follow trajectories during our follow-up questions. In particular, we were able to explore the interviewees’ reasoning and experiences when discussing further aspects of the OECD principles and their application in Vietnam.

Among our international interviewees, interviewees 3-I-I and 11-I-L supported the notion that better OECD compliance comes with better firm performance (1.1). 3-I-I outlined: “I would definitely confirm this positive correlation. That’s why we place and advise so much emphasis on corporate governance” (3-I-I). 11-I-L commented: “Yes, of course. Because corporate governance means thinking a bit more ahead about future developments, requirements, avoiding problems, being more aware of the requirements of specific business lines – and this will lead to better results” (11-I-L). Additionally, interviewees 8-I-C and 6-I-O generally supported this view. However, they emphasized that this notion might hold only when applying a long-term perspective, as 8-I-C outlined: “The stronger the corporate governance codes in the company, the higher the stock price on the market – in the long run. But there might be distortion in short-term perception” (8-I-C). Interviewee M 6-I-O said, “From a long-term point of view, the positive correlation between corporate governance performance and company performance will be observable – but this is not the case at the moment” (6-I-O). Interviewee 2-I-I was slightly more reserved, as he observed size effects: “Of course. […][but acknowledging] the correlation may depend on the size of the company” (2-I-I). Moreover, interviewee 4-I-L expected a positive association between compliance with OECD principles and firm performance and underlined his view with a comparison between private and state-owned enterprises:

I would confirm a positive correlation. The negative example is a state-owned enterprise with a clique inside, who are in managing position, where no performance of corporate governance is found at all – and the results of these companies will suffer. […] For private sector companies, we can observe good performance of corporate governance, and it is getting better. (4-I-L)

Additionally, interviewee 9-I-T emphasized that firm performance is more than financial performance:

Yes, generally. But it is important to consider more facets. From my point of view, company performance should also be measured beyond returns on equity or revenue. I like to consider more measures of efficiency and also corporate social responsibility and social impacts. The definition of company performance is crucial. (9-I-T)

One interviewee took a more diverse perspective. Interviewee 1-I-L noted that the positive correlation might not hold for domestic firms with local business models and considered the interaction with corruption:

That depends on the society, the country itself and the business the company is running. If you are solely relying on exports or on internal outsourcing – like Vietnam is a very favorable country for internal outsourcing – then yes, the better the corporate governance, the better the general performance. […]. If you sell on the local market, if you distribute to the local market, it might be different. Because the more open you are to the widely accepted corruption, the more business turnover is receivable. (1-I-L)

Two of our interviewees with a Vietnamese background argued that compliance with OECD principles is associated with better firm performance. Interviewee 7-L-L gave a short answer: “I think there is a positive correlation because the daily operations are affected by corporate governance and vice versa” (7-L-L). Additionally, interviewee 10-L-L anticipated a correlation and pointed to long-term benefits with regard to nonfinancial performance:

Yes, I think they are going towards the same direction. […] For SMEs, it is often hard to see any benefit in corporate governance – as they are not able to evaluate the whole picture. They have to think further. This can also be related to environmental protection, […] responsibility while doing business should be one key aspect. (10-L-L)

The third local interviewee took an opposing view and referred to the issues already raised by 1-I-L. Interviewee 5-L-C noted a possible positive association between compliance with OECD principles and firm performance:

No, I would not confirm this. As the reliance on doing business is focused on insider trading and relationships, this correlation cannot be observed in Vietnam – or at least not generally. Companies in Vietnam will still be able to increase their revenue per year although their corporate governance performance, according to ‘our’ ideas, is decreasing. (5-L-C)

More generally, 5-L-C points to the importance of networks: “Starting the business and setting up your company is not difficult, but it will become difficult after you’ve started – as you need to develop your network quickly in order to not lose track” (5-L-C).

5.1.4 Political stability and economic prosperity

When discussing the suitability of OECD principles for emerging countries, corresponding ratings, and the relation between compliance with OECD principles and economic prosperity, some interviewees pointed to specific determinants of corporate governance quality that might affect firm performance and economic prosperity in the aggregate. Some of those determinants, such as equitable treatment of shareholders, enforceability of rights, and board independence, have been partly mentioned and discussed above. However, almost all interviewees pointed to political stability as another important factor that needs to be considered because political uncertainty can negatively affect the conditions for doing business. Interviewees considered Vietnam’s political stability to be high, which they cited as one of the major benefits of doing business in Vietnam. Interviewee 8-I-C noted:

In terms of corporate governance, there might be a lot of things to improve. But in general, Vietnam is a frontier market and hence still needs ongoing reforms. As Vietnam is a socialist republic, the state has the highest rank and the most powerful position in the country. In terms of political stability, Vietnam can be rated as quite high; even if you look at the World Bank statistics, it’s quite a favorable score, although coming nowhere close to Singapore – but Singapore probably has one of the best political stability scores in Asia – but Vietnam’s score is higher than China, Malaysia or of course Thailand. (8-I-C)

Interviewees 3-I-I and 11-I-L made similar comments. Interviewee 3-I-I noted,

[I]f you compare Vietnam to Thailand, the clear advantage is the stability of the government – as Thailand has a lot of problems in that area. Further, the government of Vietnam places a lot of emphasis on attracting foreign investors – or on making the investment climate very easy. (3-I-I)

Interviewee 11-I-L stated: “Vietnam is already very attractive because the economic and legal environment is very stable” (11-I-L).

For interviewee 6-I-O, political stability seems to be an important indirect determinant of economic prosperity, particularly when comparing Vietnam to other Southeast Asian countries:

The most important point is political stability, a factor which we can definitely not underestimate. Have a look at the Philippines, Thailand or Cambodia – where this may not always be the case and where things can change very fast. However, Vietnam is not a democracy – but in terms of economic opportunities and possibilities, Vietnam is a quite open-minded country. (6-I-O)

Likewise, interviewees 1-I-L and 2-I-I argued that economic prosperity might be influenced by political stability and other country-level determinants, as 1-I-L said: “An additional point is the political system, which is very stable – whether the political system is good or sustainable is a totally different topic – and the people living in Vietnam are very young and eager to learn” (1-I-L). Interviewee 2-I-I said:

Attributes of Vietnam that may attract foreign investors in the future: The big and young population, good education, good infrastructure, and the political system has been stable for years – so I don’t anticipate serious upcoming changes in the political environment within the coming years. (2-I-I)

Interviewee 4-I-L outlined: