The relationship between the author and the translator from the perspective of power of tenor of discourse: a case study of the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi

-

Jiao Zhang

Jiao Zhang Wei He

ABSTRACT

Within the framework of Poynton’s power of tenor of discourse, this study explores the power relationship between the author and the translator and how the relationship is presented in the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi. The study firstly reinterprets Poynton’s power of tenor of discourse and proposes two new concepts, viz. “primary factor” and “secondary factor”. And based on this, the power relationship between the author and the translator is expounded. When the “primary factor” is status, the author and the translator are equal, but when the “primary factor” is expertise, the author and the translator are unequal, with the author dominant over the translator. The analysis of the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi shows that the equality can be presented in the subtitle and the structure of the translations while the inequality can be displayed in the interpretation of culturally loaded words, particularly Confucian core concepts, and Mengzi’s thoughts. It is also found that the equality is usually caused by translation purpose, strategy, publication requirements, etc. and the inequality is generally relevant to the translator’s limited knowledge of the original, his/her thoughts, beliefs, and life experiences, the social, cultural and historical backgrounds, inadequate references, etc.

1. Introduction

Early since the appearance of translation activities, the relationship between the author and the translator has been a frequent topic of discussion in translation studies. It is usually investigated as a part of intersubjectivity of translation together with other sets of relationships, such as the translator and the reader, and the translator and the patron. The studies on this subject are mainly carried out by a large number of Chinese researchers who mostly take the view of philosophy (e.g., Xu 2003; Yang 2005; Li 2006; Fang 2011; Chang 2011). There are undoubtedly some scholars outside China who also make considerable contributions to this field from different perspectives, including communication theory (e.g., Hatim and Mason [1990] 2001, 1997), functionalist approach (e.g., Nord 2001), postrationalism (e.g., Robinson 2001), postcolonism and feminism (e.g., Rani 2004), and poststructuralism (e.g., Van Wyke 2012). Yet few researchers have ever studied this issue from the systemic functional perspective.

Therefore, this paper attempts to explore this topic based on the power of tenor of discourse of systemic functional linguistics (SFL, hereafter) with the intention to show what the power relationship is between the author and the translator and how the relationship is reflected in the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi (Mencius). The reason for selecting Mengzi as our research data is that as one of the most famous Confucian classics, its English versions have not yet been researched from the systemic functional perspective. By contrast, the translations of Lun Yu (The Analects of Confucius), the most famous Confucian classic, have increasingly aroused the attention from the systemic functional scholars and fruitful results have been yielded in recent years (e.g., Chen 2009, 2010; Huang 2011, 2012; He and Zhang 2013, 2014).

It is expected that this study will be proved valuable for the future studies of the translations of Mengzi as well as of intersubjectivity of translation, particularly of the relationship between the author and the translator.

2. Previous studies of the relationship between the author and the translator

With regard to the relationship between the author and the translator, it is inevitable to start with the opinions of the author’s and the translator’s role in the history of translation studies. According to Pan (2002), the history of translation studies is divided into three periods, namely, the traditional period, the modern period and the contemporary period, which witness the decline of the author and the rise of the translator.

During the traditional period, scholars mostly show special interest in exploring translation methods, and in establishing translation criteria or norms. Accordingly, the author is considered as an authoritative and inviolable “master”. The translator, on the other hand, is perceived as a “servant” who should be faithful to the author, remain in a subordinate position and restrain any addition, deletion or alternation of the original. Such notions of the author as a “master” while the translator as a “servant” remain basically unchanged even in the modern period, when the translation studies is principally based on linguistic theories, such as Catford’s translation shifts (Catford 1965), and Nida’s formal equivalence and functional equivalence (Nida [1964] 2004; Nida and Taber [1969] 2004). It is in the period of the contemporary translation studies that such views have been replaced by the recognition or even highlighting of the status of the translator. For example, the hermeneutic translation theorists propose the concept of “understanding as translation” (Steiner [1998] 2001; Berman 2000) and confirm the translator’s positive function in the interpretation of the original. According to the hermeneutic theorists, the translator is not a passive recipient but an active and creative agent who may infuse his/her own cultural background, life experience, aesthetic taste, value orientation, etc. into the process of interpreting the original. A more radical translation theory that enhances the status of the translator to an unprecedented level is the destructuralist thoughts which deny the existence of the ultimate meaning of the original, subvert the author’s authority and claim that the translator is a creative subject (Derrida 1992; Venuti 1995, 1998; Davis [2001] 2004).

The views of three periods mentioned above are summarized by Chen (2005, 2007) as three research paradigms, namely, the author-centered theory in the traditional period, the text-centered theory in the modern period and the translator-centered theory in the contemporary period. He (2005) also argues that “these three research paradigms are essentially concerned with individual subjectivity and they all overlook the sociality of the human beings”. He accordingly (2005) proposes the “intersubjectivity shift”, i.e., “translation studies should shift from subjectivity to intersubjectivity”. Actually, the concept of intersubjectivity is not fresh and it has been noticed early by some scholars. Bassnett, for instance, believes that “Translation is, after all, dialogic in its very nature, involving as it does more than one voice” ([1998] 2001, 138). Toury also expresses similar ideas when he elaborates the concept of norms: “Between these two poles lies a vast middle-ground occupied by intersubjective factors commonly designated norms” ([1995] 2001, 54).

Nevertheless, it is regrettable that the early scholars only mention the relationship existing between subjects but not make any further relevant explorations. It is after Chen’s launch of “intersubjectivity shift” that some scholars (particularly Chinese scholars) start to take intersubjectivity as the research focus. Viewed from the research perspective, the current studies of intersubjectivity are mostly based on philosophy, such as Husserl’s phenomenology, Heidegger’s existentialism, Gadamer’s hermeneutics and Habermas’s communicative action theory (Xu 2003; Yang 2005; Li 2006; Fang 2011; Chang 2011). There are also a few studies researched from other perspectives, such as communication theory (Hatim and Mason [1990] 2001, 1997), functionalist approach (Nord 2001), postrationalism (Robinson 2001), postcolonism and feminism (Rani 2004), and poststructuralism (Van Wyke 2012). As regards the research results, some studies show that there is a dialogue relationship between the subjects (Hatim and Mason [1990] 2001; Xu 2003; Yang 2005; Fang 2011). Hatim and Mason, for instance, focus on the relationship between the author, the translator and the target reader and propose that “the translator stands at the center of this dynamic process of communication, as a mediator between the producer of a source text and whoever are its TL receivers” ([1990] 2001, 223). There are also some researches indicating that there exists an interaction relationship between the subjects (Nord 2001; Robinson 2001; Li 2006; Chang 2011). For example, Nord (2001, 15–26) studies the roles of initiator and commissioner, translator, source-text producer, target-text receiver, and target user, and considers translating as an intentional and interpersonal interaction.

Through the review above, it can be seen that previous studies relating to the relationship between the subjects, including between the author and the translator, are essentially confined to the philosophical perspective and have achieved no substantial development to date. In addition, the descriptions of the relationship between the subjects, namely, the dialogue or interaction relationship, are relatively general, and even vague. It is not very clear how the subjects communicate in the dialogue or interaction.

Therefore, we intend to clarify the relationship between the author and the translator from the perspective of SFL1. In SFL, the relationship between participants in a language event is called tenor of discourse2, which includes social roles relationship and interactional roles relationship (Zhang 1991). Thus, the relationship between the author and the translator can be expounded from these two aspects. But in view of the limited space and the complexity of social roles relationship, this paper only investigates the social roles relationship, specifically speaking, the power relationship, between the author and the translator based on the concept of power of tenor of discourse. As regards other aspects of social roles relationship as well as the interactional roles relationship, we will discuss them in future papers. Hopefully, from the perspective of power of tenor of discourse, this paper can give a clear elaboration of the power relationship between the author and the translator and cast new light on translation studies.

3. The concept of power in SFL

Power, a sociological term, has been employed to explain linguistic phenomena by many researchers (e.g., Brown and Gilman 1960; Brown and Ford 1964; Fairclough 1989; Fasold [1990] 2000; Hudson [1996] 2000). According to Brown and Gilman (1960), “power is a relationship between at least two persons, and it is nonreciprocal in the sense that both cannot have power in the same area of behavior”. In SFL, power is a dimension of tenor of discourse, even though it is explored under different names by different researchers3 (e.g., Hasan 1978; Halliday and Hasan 1985; Poynton 1984, 1989, 1990; Zhang 1991, 1998; Martin [1992] 2004; Gao 2001; Butt, forthcoming, Butt and Moore 2013; Zhu 2009). This paper will be founded upon Poynton’s model because it is more influential and contributes a lot to the establishment of the subsequent models of power (e.g., Zhang 1991, 1998; Martin [1992] 2004; Gao 2001). In what follows we will briefly review this model.

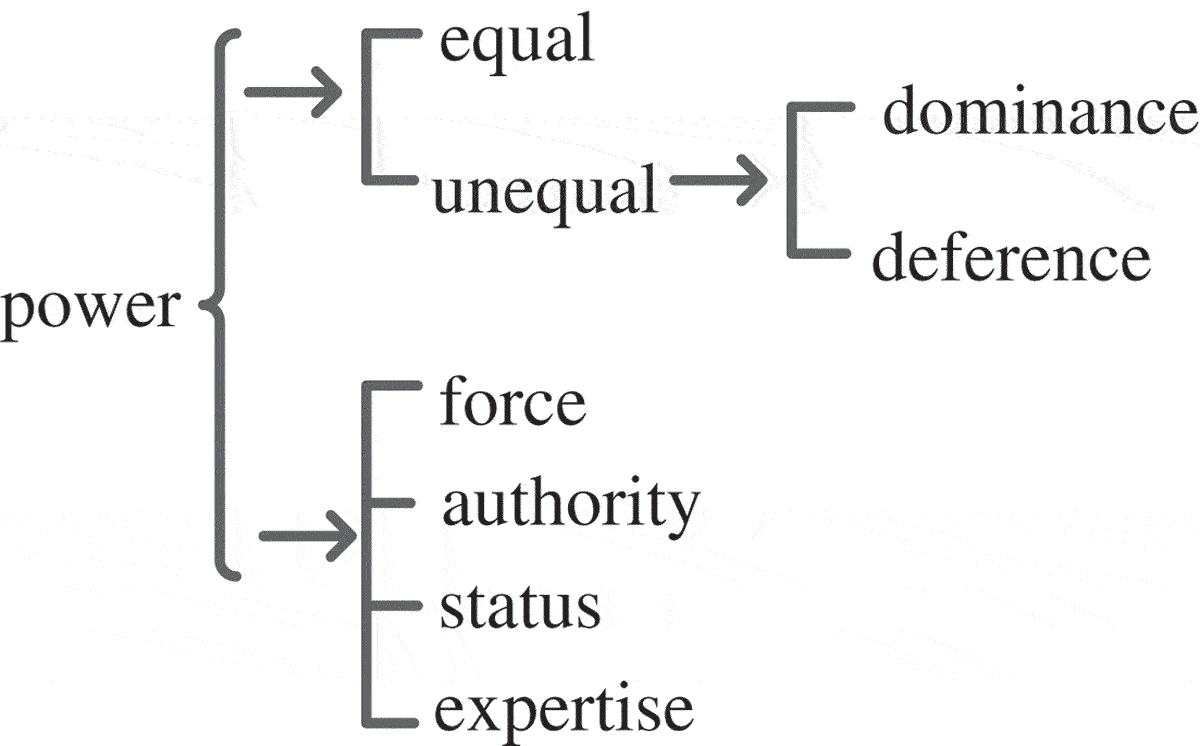

Poynton’s model of power is founded upon Brown and his colleagues’ studies (Brown and Gilman 1960; Brown and Ford 1964) which suggest two dimensions of social relations: a vertical power dimension and a horizontal solidarity dimension. Poynton (1984, 1989, 1990) preserves the power dimension but splits the solidarity dimension into contact and affect4. Power is classified into equal and unequal, with the latter further categorized into dominance and deference. It should be noted that the two extremities of equal and unequal are not two discrete choices but have a cline between them. In addition, Poynton (1989, 76–77) identifies four factors that contribute to the power system: force, authority, status, and expertise. Specifically, force indicates “physical superiority”; authority refers to “a function of socially legitimated inherently unequal role relationships such as parent-child, teacher-child, employer-employee, or ruler-ruled”; status involves “a matter of relative ranking with respect to some unevenly distributed but socially desirable object or standing or achievement, e.g., wealth, profession/occupation, level of education, hereditary status, location of residence, overseas travel”; expertise means “a matter of the extent to which an individual possesses knowledge or skill, e.g., the expert knitter compared with the novice, the nuclear physicist with the high school student beginning to study physics”. Poynton’s network is shown in Figure 1.

Poynton’s network of power (1989, 77)5.

Poynton’s network of power is comparatively elaborate and illuminating and provides some enlightenment for her successors. Martin ([1992] 2004), for example, follows Poynton’s model and makes more contributions to the linguistic realization of unequal status. Zhang (1991, 1998), based on Poynton’s network, proposes a new concept, i.e., interactional tenor, which constitutes tenor of discourse, along with social tenor. An important point to realize is that the two terms “equal” and “unequal” are relative concepts and the power relationship between participants is subject to the alternation of the factors involved in the context of situation, as Hasan points out, “control may shift from one agent role to the other, and that a person carrying a subordinate hierarchic role in the agent dyad is not necessarily submissive” (Halliday and Hasan 1985, 57). For example, an employer has control over an employee in terms of authority. But if the employee happens to be a good cook while the employer knows little about cooking, the control may shift from the employer to the employee when they are talking about cooking, because the employee has more power in terms of cooking expertise. Similarly, if the employer and the employee are both amateurs respectively from two amateur football teams, they tend to be equal in a football match, for they have a peer-hood relationship in such an environment.

However, there is a problem in Poynton’s power network, viz., the classification of the four sets of factors covers up the complexity of the power relationship between participants. In SFL, “{” means “both…and choice” and “[” refers to “either…or choice”. In other words, “{” indicates that the choice is inclusive and all systems on the right should be chosen while “[” signifies that the choice is exclusive and only one system on the right can be chosen. Actually, the relationship between participants may be more complex in a specific context of situation because there may be more than one factor at work. For example, it is very easy to justify that a president is dominant over his/her aide when giving orders, since there is only one factor, namely, authority, at work. However, the relationship between a president and an economist may be quite complex in a specific situation, such as talking about making economic policies, because both authority and expertise may play roles. Specifically speaking, both the president and the economist may pay much more attention to their wordings, tones, etc., because the economist is inferior in authority while the president is in a subordinate position in terms of expertise, i.e., the knowledge of economics. Hence, we think that the coexistence of two or more factors in a specific context of situation conflicts with the “either…or choice” principle. As for this problem, neither Poynton nor her successors, such as Martin, Zhang, and Gao, give any explanation6.

To solve this problem, we think that it is necessary to measure which factor is more important in a specific context of situation. Here we can borrow the two terms “primary” and “secondary” from Halliday’s clarification of “primary clause” and “secondary clause” (Halliday 1994). In a situation where the factor plays a crucial role in determining the language forms of the participants, the factor is the “primary factor”, while other factors “secondary factor(s)”. Therefore, when there are two or more factors at work, the “primary factor” should be firstly identified so that the power relationship between participants can be known. Thus, it is not difficult to tell the power relationship between the economist and the president, since the “primary factor” in the situation of talking about making economic policies is the economic expertise although “the secondary factor”, i.e., authority, is also involved. Concretely speaking, the economist has control over the president although the factor of authority may make the economist more cautious of his/her tone, word choice, or even manner. In addition, there seems to be more than one “primary factor” in some contexts of situation. But actually, there is only one factor that can play a crucial role in determining the power relationship between participants. For instance, in a classroom, an economist seems to be dominant over his/her students in terms of both authority and expertise. But it is authority that plays a decisive role in determining the power relationship between them, for the economist’s expertise may be occasionally challenged by his/her students.

4. The power relationship between the author and the translator

Based on what has been discussed in the prior section, let us explain the power relationship between the author and the translator in this section.

As the power relationship between participants is subject to the four sets of factors, it is essential to first clarify all the factors that are associated with the power relationship between the author and the translator. Of the four sets of factors, only status and expertise can affect the relationship between them. By contrast, force and authority are irrelevant factors since the author and the translator cannot be compared in terms of physical superiority and socially legitimated inherently relationship. After discerning the related factors, in the following paragraphs we are going to identify the “primary factor”, and thereby the power relationship between the author and the translator can be determined.

Translation is a complex process in which the “primary factor” is not fixed and it depends on what the specific process is. For example, translation can be seen as a process of creating a new work. Or in other words, it not only prolongs the original text but also gives it a second life (Escarpit 1958). In this case, the translator can be viewed as an “author”. Thus the “primary factor” is status and the “secondary factor” is expertise, because the translator assumes the role of “author” in creating a new work. In terms of status, the author and the translator are equal because neither is superior or inferior to the other in “socially desirable object or standing or achievement”. Specifically speaking, the author’s business is writing while the translator’s business is translating. Both are equal occupations and cannot be determined which one is superior or inferior to the other. The great effort the translator devotes is similar to the hard work the author undertakes in writing.

However, when translation is viewed as the manifestation of the translator’s understanding of the source text, the “primary factor” is expertise while the “secondary factor(s)” is status. In this case, the author is dominant over the translator because the author has more knowledge of the original than the translator. Concretely speaking, the author infuses his/her thoughts, emotions, life experiences, etc., into the source text and knows more about his/her own work than the translator. The translator is firstly required to interpret the original as a reader before s/he begins translating. S/he has to follow the author and bases his/her understanding on the original. Hence, the translator is in a disadvantageous position in comprehending the source text. It is important to note that the expertise in question is only confined to the knowledge concerning the original and the author. Therefore, the translator’s inferiority discussed here does not imply that the translator has less knowledge of other aspects compared with the author. As regards what results in the translator’s inferiority, besides his/her limited knowledge of the original, his/her thoughts, beliefs, and life experiences, the social, cultural, and historical backgrounds; lack of materials and reference books; etc. are also involved. For example, literary works usually contain some idioms, allusions, sayings, culturally loaded words, etc. If the materials and reference books are less accessible, the translator will be in an unfavorable position when interpreting such things.

In the ensuing section, the equality and inequality between the author and the translator will be discussed by examining the peritexts7 of the translated versions of Mengzi.

5. The equality and inequality in the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi

Mengzi, as one of the most influential Confucian classics, occupies an important place in traditional Chinese cultural studies. It is a work of quotation and generally believed to be written by Mengzi and his disciples8. Mengzi records the speeches and actions of Mengzi, as well as his dialogues with his contemporaries, reflecting his political doctrines, ethical, philosophical and educational thoughts.

Mengzi has already been translated into many languages, and there have been a dozen translations in English, abridged and unabridged, since the publication in 1828 of that by David Collie (Ji 2011). This section will focus on unabridged translations, such as Legge’s (1970), Dobson’s (1963), Lau’s (1970), He’s (1999), Zhao, Zhang, and Zhou (1999), Van Norden’s (2008) and Bloom’s (2009).

5.1. The equality

As we have suggested in the above section, when translation is regarded as a process of producing a work, the “primary factor” is status; thus, the author and the translator are equal. In other words, both the author and the translator are engaged in different word activities where they share equal status and enjoy equal rights.

Such equality can be manifested in the peritexts of a translation in two aspects: one is in the title and the other in the structure. As for Mengzi, it is mainly shown in the subtitle and the structural configuration.

5.1.1. The equality in the title

Equality between the author and the translator can be firstly illustrated in the title of a translation. The title of a literary work is usually determined by the author after deep thinking and repeated scrutiny. It customarily comprises a limited number of words, yet makes a highly condensed summary of the work and contains abundant associative meanings. Consequently, the translator can be exempt from the restrictions of the original title and names his/her own translation according to the theme of the original. For example, when the Russian novel Как Закалялась Сталь was translated into Chinese, the translator did not render it freely but followed the literal meaning of the title and translated it as 钢铁是怎样炼成的 (gangtie shi zenyang lian cheng de: How was the steel tempered?). Its English title, by contrast, was The Making of a Hero, which apparently was based on the theme of the novel rather than the literal meaning of the original title. Strictly speaking, this English title is not a translated, but a new name given by the translator.

As for traditional Chinese classics, the equality is primarily reflected in the subtitle. When translating the title of a Confucian classic, the translator usually transliterates it or renders it according to its literal meaning. For example, the Chinese title 孟子 is either transliterated into Mengzi, or Mencius, or translated into “The Works of Mencius”, or “The Sayings of Mencius”. In addition, a subtitle may be added in some versions, such as “A New Translation” in “The Sayings of Mencius: A New Translation”, and “A New Translation Arranged and Annotated for the General Reader” in “Mencius: A New Translation Arranged and Annotated for the General Reader”. In Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners, “subtitle” is defined as “an additional title that appears after the main title of a piece of writing such as a book, song, or play, and gives extra information” (2003, 1433). As for a translated work, its subtitle provides the extra information that mainly reveals “the features or main focuses of the translation” (Huang 2011). Accordingly, only with a quick glance at the subtitle, some attentive readers may instantly learn the features or main focuses of the translation, feel the presence of the translator and realize his/her translation purpose and strategy. In addition, the subtitle of a translation indicates that the translator has the right to title his translation according to its features, just as the author has the right to title his work according to its contents. Thus from this perspective, both the author and the translator enjoy the same status, for they have equal right to title their respective works.

For example, when turning over the cover page of Van Norden’s version, some careful readers who have ever read other English versions may perceive the particular features of this translation by a glimpse of the subtitle “With Selections from Traditional Commentaries”. This subtitle means that there are some traditional Chinese commentaries in the translated work. Such commentaries do not exist in the original work and are also rarely seen in other English versions. With the subtitle, Van Norden indicates the philosophical style of his translation, as Philip J. Ivanhoe remarks, “This is the most accurate, readable, and philosophically revealing version of the Mengzi available” (Van Norden 2008, back cover). Moreover, with the subtitle, Van Norden reveals one of his translation purposes, viz., to make the reader understand Mengzi with the assistance of traditional commentaries, as he (2008, xiv) points out, “even a text like the Mengzi, which often speaks in terms that a person in any era or culture could appreciate, sometimes cries out for philosophical commentary”.

Another convincing example can be seen in the subtitle of Dobson’s version, namely, “A New Translation Arranged and Annotated for the General Reader”. When taking a brief glance at it, some perceptible readers may realize the main features of the translation, i.e., the rearrangement in the organization of the source text and the annotations provided for the general reader; some inquisitive readers may have some doubts in mind, and for example, why is it arranged and annotated for the general reader? With such doubts in mind, they may infer that the original is incoherent and abstruse. And they can find that their inferences are correct when reading Dobson’s introduction9. Thus, it can be seen that only by reading the subtitle can some readers easily identify the translation features and purposes of a version.

5.1.2. The equality in the structure

The other aspect of equality is mainly manifested in the structural organization of a translation. The translator does not have to follow the organization of the original; instead he enjoys much freedom to rearrange the structure of his translation and makes it more like a creative work rather than a translation. Moreover, the translator can add some parts, viz., the peritexts, to the translation, such as a preface, an introduction, a glossary, an appendix, and some notes.

As Mengzi is a work of quotation, its paragraphs are put together at random, which makes it rather difficult for the reader to get a coherent picture of Mengzi’s thoughts. To resolve this problem, some translators rearrange the organization of the original. A typical example is Dobson’s translation. The original is composed of seven “books”, with each “book” containing two “parts”, which may respectively include varying numbers of “passages”. Dobson, however, does not follow this organization, but reorganizes the “passages” into seven “chapters” in accordance with the topics “with the intention that the reader may thus obtain a more coherent picture of Mencius’ thought” (Jonker 1967). The seven “chapters” are respectively named Mencius at Court, Mencius in Public Life, Mencius and His Disciples, Mencius and His Rivals, Comment on the Times, The Teachings of Mencius and Maxims. Moreover, each “chapter” is again divided into a number of smaller “sections” according to the topics and each of the smaller “section” is again given a heading. Mencius at Court, for instance, covering the “passages” that record Mengzi’s conversation with kings, is divided into four “sections”: At the Court of King Hsuan of Ch’I, At the Court of the Kings of Liang, At the Court of the Duke of T’eng and In the State of Song. It can be said that Dobson’s version is a typical variation translation (Huang 2002) and he alters the original structure so dramatically that his translation looks more like a new work.

There are only a few translators who make great variations to the main body of the original work as Dobson does. Most translators, however, make minor changes to the main body, but add some parts, i.e., the peritexts, to the translation, such as a preface, an introduction, a glossary, an appendix, and some notes. Such a translation can also be seen as an independent work because its structure is more comprehensive than that of the original and the translator enjoys much freedom in structuring his/her translation. Legge’s version is a representative of thick translation, and besides the Chinese text and the translation, it also includes an elaborate prolegomenon, lots of footnotes and three indexes. Van Norden’s version of Mengzi, similarly, consists of a preface, an introduction, a timeline, two bibliographies of relevant works, a glossary and massive traditional Chinese commentaries interwoven in the translation. By contrast, the structure of He’s version is very simple, and there is only a very brief preface, a short forward, and a small number of notes attached to the Chinese text and the translation. Such a simple structure can be also found in Zhao, Zhang and Zhou’s translation, which is composed of a bilingual preface, a bilingual introduction, a bilingual table of translated nouns or terms, in addition to the Chinese text and the translation. Bloom’s version lies between them and it consists of a preface, a glossary, a reading section, and a translation with some notes. The translators may structure their translations differently for various reasons, such as their different translation purposes, strategies, and publishing restrictions. For instance, the valuable peritexts of Legge’s version are intended to give the target reader (mainly the missionaries) a complete picture of traditional Chinese thought and culture (i.e., Confucianism), and thereby promote the spread of Christianity. He’s version, by contrast, mainly aims to “help young readers understand this great Chinese classic” (1999, foreword), so its peritexts are fewer and less academic. Thus, the versions discussed above can form a continuum in terms of their structure, with Legge’s translation at one end, He’s version at the other, and Bloom’s and Zhao, Zhang, and Zhou’s translation lying between them.

In addition, the equality between the author and the translator is also reflected in the space that such peritexts take up in a translation. In Legge’s version, for instance, each passage of the source text is accompanied by a footnote so that the footnotes in a page occupy roughly the same space as the source text together with its translation does. In other words, a page is evenly divided into two parts, one for the source text and its translation and the other for its footnotes. Moreover, it’s worth mentioning that Legge provides a more than 100 pages of prolegomena, which constitutes approximately one-fifth of the whole book. In general, the room the peritexts occupy in Legge’s version is much more than that the source text as well as the translation does. The peritexts of Van Norden’s translation also take up much space. Different from the organization of Legge’s translation, Van Norden’s version has no source text and its translation is interwoven with traditional Chinese commentaries, primarily drawn from Zhu Xi’s interpretation of Mengzi’s thoughts. The space that some commentaries take up is even more than that the translated text does. For example, the passage未有仁而遗其亲者也,未有义而后其君者也。王亦曰仁义而已矣,何必曰利 (wei you ren er yi qi qin zhe ye, wei you yi er hou qi jun zhe ye. Wang yi yue ren yi er yi yi, he bi yue li) is rendered by Van Norden (2008, 1) as follows:

Never have the benevolent left their parents behind. Never have the righteous put their ruler last. Let Your Majesty speak only of benevolence and righteousness. Why must one speak of “profit”?

This translation only has 31 words and takes up less than two lines in Van Norden's work. However, it is followed by a nearly full page, amounting to 350 words of comments by Zhu Xi, together with Van Norden’s own understanding of this passage10. Furthermore, the font size of the commentaries is as same as that of the target text and the only difference is that the commentaries are italicized and placed in square brackets.

In short, the author and the translator are equal in terms of status when translation is seen as a process of producing a book. The equality between the author and the translator can be demonstrated in both the title and the structure. On the one hand, the translator is allowed much latitude to give a title, especially a subtitle, to his/her translation in accordance with the features of the translation. On the other hand, the translator has much right to add some peritexts to the translation, assign the space the peritexts take up and even rearrange the organization of the source text.

5.2. The inequality

When translation is considered as the embodiment of the translator’s comprehension of the source text, the “primary factor”, i.e., the factor that plays a decisive role, is expertise. Thus, the author and the translator are unequal, with the author dominating over the translator, since it is the author who creates the original work and fits his/her thoughts, opinions, feelings, emotions, etc. into the work. In other words, compared with the translator, the author knows more about his/her work and qualifies more for the interpretation of the source text. The translator, however, stands in an inferior position and s/he may not fully comprehend or even misinterpret the source text. For example, it is generally believed that the author of a professional astronomy book is knowledgeable than a translator in terms of the knowledge of astronomy. Thus, the author may have more power than the translator in interpreting his/her book. Likewise, the author of a traditional Chinese classic, such as Mengzi, has more control over the translator in interpreting the original.

Such inequality can be manifested in the translator’s inferiority in interpreting such things as the author’s thoughts, opinions, feelings, and emotions, as well as the professional knowledge that the author has. As regards Mengzi, such inequality is mainly demonstrated in the peritexts in two ways: one is the translator’s inferiority in explaining the culturally loaded words, particularly Confucian core concepts, and the other is in interpreting Mengzi’s thoughts.

5.2.1. The translator’s inferiority in explaining the culturally loaded words

In Confucian classics, there are a large number of culturally loaded words, among which Confucian core concepts, such as仁 (ren), 义 (yi), 礼 (li), 智 (zhi), 德 (de), 天 (tian), 命 (ming), 道 (dao) and 气 (qi)11, often confuse translators because they contain rich and deep ethical and philosophical connotations. They were initially proposed by Kongzi (Confucius) and many of them were developed and endowed with new meanings by Mengzi and other Confucians. In the translations of Mengzi, such core concepts are usually interpreted in the peritexts, such as in the introduction, footnotes, the glossary, and the appendix. However, according to our close reading of the original, we find that some interpretations of the translations are either incomprehensive or simplified, which indicates the translator is in a subordinate position when comprehending these core concepts.

In Van Norden’s version of Mengzi, there is an English-Chinese glossary presenting a list of such core concepts, each of which contains the Chinese character, and its pinyin, translation and meanings. Through a careful reading, it is found that some of them are not comprehensively interpreted. The concept天 (tian), for instance, is translated into “Heaven” and interpreted in the glossary as follows: “A semipersonal higher power, responsible for ‘the Way’ and ‘fate’” (2008, 202). According to this interpretation, 天 (tian) contains two layers of meaning: one is about “the Way” and the other is about “fate”. 天 (tian) meaning “the Way” means天 (tian) has the property of virtue, like tian 天 in the Chinese text: 仁义忠信,乐善不倦,此天爵也 (ren yi zhong xin, le shan bu juan, ci tian jue ye: benevolence, righteousness, faithfulness, truthfulness, and a tireless spirit of benefiting others – these are honors bestowed by Heaven.). 天 (tian) meaning “fate” denotes an invisible and enormous power which is beyond the control of human beings, like天 (tian) in the sentence: 莫之为而为者,天也 (mo zhi wei er wei zhe, tian ye: when a thing is done by an unknown agent, then it is the work of Heaven.). However, Mengzi’s concept of天 (tian) is not confined to these meanings but extends to “nature” (eg. He 1995; Zeng 2008). In 1A6, the Chinese text reads: 天油然作云,沛然下雨,则苗浡然兴之矣 (tian you ran zuo yun, pei ran xia yu, ze miao bo ran xing zhi yi: If the clouds gather densely in the sky, and rains come pouring down, then the plants will flourish again.). The term 天 (tian) in this passage does not carry the philosophical meaning of “the Way” or “fate”, but refers to “nature”, i.e., the sky seen from the earth’s surface. So it is incorrect to treat it as “Heaven” in his translation: “But when Heaven abundantly makes clouds, and copiously sends down rain, then the sprouts vigorously rise up” (2008, 7). Here the interpretation of 天 (tian) is obviously philosophy-oriented. As Yuet (2011) remarks, Van Norden tends to over-philosophize these concepts; therefore, some of them are not adequately interpreted. We think that such over-philosophization is probably influenced by his identity and life experiences. Van Norden is currently a philosophy professor from Vassar College and he (2008, ix) mentions in the preface that his version is based on his previous translations of some portions of Mengzi for use in his own classes. Furthermore, Van Norden (2008, ix) stresses that he is heavily indebted to three of his teachers, viz., Lee H. Yealey, David S. Nivison and Philip J. Ivanhoe. All of them are renowned sinologists who focus on traditional Chinese classics from the perspective of philosophy. Consequently, it is plausible that his interpretation is strongly philosophical.

The translator’s secondary position is also demonstrated in his/her simplified treatment of some core concepts. For example, in Bloom’s translation (2009, 7),德 (de) is interpreted in the footnote as follows:

The word translated “Virtue” here is de 德. It connotes the moral quality of a person’s character–good or bad. One with abundant, good Virtue enjoys a kind of moral charisma, which attracts and secures the support of others.

It is evident that from Bloom’s point of view, the concept德 (de) only expresses one layer of meaning, i.e., “the moral quality of a person’s character.” As for what “the moral quality of a person’s character” denotes, there is no further explanation. Moreover, further information concerning this concept is nowhere to be found. Actually, 德 (de) occurs many times in the original work and contains multiple meanings, hence such a simple footnote cannot interpret them distinctly. For example, the passage 天下有达三尊: 爵一, 齿一, 德一 (tianxia you da san zun: jue yi, chi yi, de yi: There are three things that are generally accepted by the world as exalted: rank, age and virtue.) discusses the three categories of people who deserve respect in that historical period, therefore德 (de) here is surely interpreted as “the moral quality of a person’s character”, concretely speaking, “the good moral quality of a person”. However, in 德何如则可以王矣 (de he ru ze keyi wang yi: With what kind of virtue can one unify all the states?), 德 (de) conveys another implication, which can be inferred from the co-text. This is a question raised by King Xuan of Qi who intends to seek Mengzi’s advice on the unification of all the states. Regarding this question, Mengzi says: 保民而王, 莫之能御也 (bao min er wang, mo zhi neng yu ye: No one can be prevented from unifying all the states if he cares for the people.). Mengzi’s answer shows that bao min er wang 保民而王 (bao min er wang: caring for the people) is the 德 (de) that ensures one’s winning the unification of all the states. Hence, 德 (de) in his passage can be interpreted as “ruling measures”. Moreover, in 求也为季氏宰, 无能改于其德 (qiu ye wei jishi zai, wu neng gai yu qi de: Qiu was the steward of the Ji Family and was unable to change their behavior.), 德 (de) is generally interpreted as “a behavior” (Yang 1960, 175; Jiao 1987, 515; Zhao 1999, 202; Fu 2006, 127), or specifically speaking, “an evil behavior”, namely, the intention of increasing tax revenue “by changing the tax system” (He 1999, 230). Then, why is the interpretation of 德 (de) in Bloom’s version so simplified? According to its preface (2009, vii), it was not completed independently because Bloom was seriously ill during her translation of Mengzi. Accordingly, the work afterward, such as editing and adding a preface, an introduction, references, etc., was completed by Philip J. Ivanhoe. Accordingly, it is obscure who makes the note of 德 (de), or in Godin’s (2010) words, “since Ivanhoe did not indicate any of his emendations in the text, it is impossible for a reader of the published book to tell who was responsible for what”. Since there is no any indication of who made the note, it is rather difficult to determine why德 (de) is interpreted in such a simplified way.

5.2.2. The translator’s inferiority in interpreting Mengzi’s thoughts

Based on Confucius’ doctrines, Mengzi puts forward his own ethical and philosophical thoughts, such as “the theory of good nature”, “the policy of benevolence”, “the doctrine of kingcraft” and “the people-oriented thought”. These thoughts are unique to Chinese culture and less accessible to the target reader. Accordingly, the translator usually opts to clarify them in the peritexts. However, it is mainly due to the translator’s finite knowledge about Mengzi that some of the thoughts are sometimes not clearly illustrated and even misinterpreted.

There is a famous passage in Mengzi, which reads as follows: 天时不如地利, 地利不如人和 (tian shi buru di li, di li buru ren he: In the war, the favorable weather is less important than the terrain advantage and the terrain advantage is less important than the unity of people). This passage emphasizes the dominant roles that people play in a war by comparing three conditions, viz. 天时 (tian shi: the favorable weather), 地利 (di li: the terrain advantage) and人和 (ren he: the unity of people), reflecting Mengzi’s “people-oriented thought”. Nevertheless, this thought seems to be not clearly illustrated in the notes of some versions. For instance, Van Norden (2008, 50) makes no mention of this thought in the notes, but pays more attention to the “three powers”, i.e., 天 (tian: Heaven), 地 (di: Earth), and 人 (ren: People). The “three powers”, containing rich and profound philosophical meanings, refer to the three elements that make something possible. It is obvious that Van Norden ignores the basic idea of this passage and concerns more about the philosophical meaning of the “three powers”. We think his deviation of interpretation is closely related to his own personal experiences, which we have specified in the previous section. In other words, since his educational background and research focus never go beyond philosophy, it is inevitable that his interpretation is so philosophical. By comparison, Lau (1970, 85) clearly presents the “people-oriented thought” in the footnote: “Mencius is here claiming for Man an importance greater even than Heaven and Earth”. Lau is not only a sinologist, linguist and translator but also a philosopher, so why does Lau’s interpretation appear less philosophy-oriented? We think the answer lies partly in his translation purpose. According to the comments on Lau in the Honorary Degrees Congregation12, Lau was entrusted by Penguin to translate the three traditional Chinese classics, i.e., Tao Te Ching, Mengzi, and Lun Yu, after he expressed as a reviewer his dissatisfaction with the translations of Tao Te Ching by others. One of the reasons for his dissatisfaction was that those translations were lacking in authenticity. Then, we may safely draw a conclusion that one of his translation purposes is to present authenticity of the traditional Chinese classics. Therefore, it is natural that his interpretation of this passage is not too philosophical. Moreover, Lau’s version is “presumably intended both for the general public and for the sinologist” (Jonker 1973), so his interpretation can balance the needs of both sides.

Another example can be illustrated in the passage that concerns Mengzi’s position as a teacher, namely, 人之患在好为人师 (4A23) (ren zhi huan zai hao wei ren shi: The trouble with people is their being too eager to assume the role of teacher.). This passage may confuse some people because it appears that Mengzi is critical of teaching others. In other words, why does Mengzi say that since he is also a teacher? Furthermore, does it contradict with Mengzi’s great reverence for Confucius who ran a private school and recruited disciples? Actually, Mengzi does not object to teaching but opposes those who are conceited and prefer to pose as a teacher so as to show off their learning. The notes in some translations show that some translators do not completely understand this passage. Van Norden, for instance, points out in the note that Mengzi’s view is echoed in George Savile’s words: “Gegorege Savile made a similar point: ‘The Vanity of teaching often tempteth a Man to forget he is a Blockhead’” (2008, 100). Here Van Norden’s knowledge formerly stored in his mind is retrieved and plays a key role in his understanding of this passage. However, there are differences between such knowledge (academically speaking, intertextual knowledge) and what the passage really means. According to our understanding, George Savile intends to criticize those who pretend to know what they don’t know. Legge (1970, 311), by contrast, makes notes as follows: “Commentators suppose that Mencius’s lesson was that such a liking indicated a self-sufficiency which put an end to self-improvement”. Apparently, Legge’s understanding follows the interpretations of some commentators, probably of Zhu Xi, because such an interpretation is given in Zhu Xi’s Sishu Jizhu (Reflections of the Four Books), one of the most important references that Legge consults in his translation13.

To sum up, when translation is considered as the manifestation of the translator’s understanding of the original, the author has an advantage over the translator in interpreting the source text, for the “primary factor” in such a context is expertise. Concretely speaking, the culturally loaded words, especially the Confucian core concepts, are characterized by rich connotations, and thereby put the translator in an unfavorable position in translation. There does exist a certain gap between the translator’s understanding and what the concepts really mean in the source text. Likewise, Mengzi’s thoughts are abstruse and profound, which may also leave the translator in a disadvantageous situation. The translator cannot comprehend the thoughts the works deliver as deeply as the author does. In addition, from the perspective of cultural communication, the incompletion, simplification, or even misinterpretation of the core concepts and Mengzi’s thoughts undermine to a certain extent the outward spread of Mengzi’s thoughts.

6. Summary

From the perspective of Poynton’s power of tenor of discourse, this study investigates the power relationship between the author and the translator and how the relationship is shown in the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi, with the aim to clarify the relationship from a new point.

Before examining the relationship between the author and the translator, the paper firstly revises Poynton’s power of tenor of discourse and proposes two new concepts, i.e., the “primary factor” and the “secondary factor(s)”. Based on this, the paper specifies the relationship between the author and the translator: when translation is seen as a process of producing a book, the “primary factor” is status, and thereby the author and the translator are equal; when translation is perceived as the manifestation of the translator’s understanding of the source text, the “primary factor” is expertise, and thus the author and the translator are unequal.

After clarifying the relationship between the author and the translator, the paper explores how the peritexts of Mengzi are presented when they are equal or unequal and what reasons may lead to equality or inequality. Concretely speaking, the equality between the author and the translator is shown in the choice of the subtitle and the arrangement of the structure of the target text, which may be influenced by such factors as translation purpose, strategy and publication requirements; the inequality between the author and the translator is displayed in the interpretation of the culturally loaded words, particularly Confucian core concepts, and Mengzi’s thoughts, which may be impacted by the translator’s limited knowledge of the original, his/her thoughts, beliefs, and life experiences, the social, cultural and historical backgrounds, inadequate references, etc.

Funding source: Beijing Social Science Fund10.13039/501100009625

Award Identifier / Grant number: 16YYB014

Funding source: China Women’s University Scientific Research Project10.13039/501100008524

Award Identifier / Grant number: KY2018-0304

Funding statement: This study is supported by the Beijing Social Science Fund [16YYB014] and the China Women’s University Scientific Research Project [KY2018-0304].

About the authors

Jiao Zhang, PhD of literature, lecturer of Foreign Languages Department, China Women's University. Research interests: systemic functional linguistics, translation studies, discourse analysis

Wei He, PhD of literature, professor of Beijing Foreign Studies University. Research interests: systemic functional linguistics, translation studies, ecolinguistics, discourse analysis

Notes

- 1.

There have been a very few pioneers who study the translation subjectivity based on SFL. Among them, Munday (2008) is the most representative.

- 2.

- 3.

Power is called “status” by Zhang (1991, 1998), Martin ([1992] 2004) and Gao (2001).

- 4.

Contact refers to “a social distance or intimacy” and involves four factors: the frequency of interaction, the extent in time of the contact, the extent of the role-diversification and the orientation of the interaction. Affect means “attitude or emotion towards addressee (or towards the field of discourse)” and includes two factors: marked and unmarked (Poynton 1989, 76–78). Both of them can be employed to explore the relationship between the author and the translator. But due to the space limitation, this thesis is only based on power and follow-up studies will deal with contact and affect.

- 5.

In SFL, “{”means “both…and choice” and “[” means “either…or choice”.

- 6.

Martin ([1992] 2004), Zhang (1991, 1998) and Gao (2001) do not classify the factors. That is probably why they have no explanation for this problem.

- 7.

- 8.

Mengzi is a renowned thinker, educator, and philosopher living in the Warring States Period of Ancient China. There are two other opinions concerning Mengzi’s author: one is to believe that it is written by Mengzi himself and the other is by his disciples. Please see Lv (1986) for more details.

- 9.

Please see Dobson (1963, xi-xviii) for more details.

- 10.

In view of limited space, the commentaries are not quoted here in this paper. For more details, please see Van Norden (2008, 1–2).

- 11.

Most core concepts contain multiple meanings, each of which are subject to a specific context situation; hence, their meanings are not indicated here.

- 12.

For more details, Please see http://www4.hku.hk/hongrads/index.php/archive/graduate detail/172.

- 13.

According to Cheng (2002), Legge draws extensively from Sishu Jizhu (Reflections of the Four Books).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

BassnettS.[1998] 2001. “The Translation Turn in Cultural Studies.” In Constructing Cultures: Essays on Literary Translation, edited by S.Bassnett and A.Lefevere, 123–140. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

BermanA.2000. “Translation and the Trials of the Foreign.” In The Translation Studies Reader, edited by L.Venuti, 284–297. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

BloomI.2009. Mencius. New York: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

BrownR., and M.Ford. 1964. “Address in American English.” In Language in Culture and Society, edited by D.Hymes, 234–244. New York: Harper and Row.Search in Google Scholar

BrownR., and A.Gilman. 1960. “The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity.” In Style in Language, edited by T. A.Sebeok, 253–276. Massachusetts: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

ButtD.Forthcoming. Parameters of Context: On Establishing the Similarities and Differences between Social Processes.Search in Google Scholar

ButtD., and A.Moore. 2013. “Contexts and Registers through Network Representations: The Textures of Text and of Social Experience.” Paper presented at the 40th International Systematic Functional Congress, July 15–19, Guangzhou.Search in Google Scholar

CatfordJ. C.1965. A Linguistic Theory of Translation: An Essay in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

ChangH.2011. “Fanyi ‘Zhuti Jianxing’ De Bianzheng Lijie [Dialectical Interpretation of Intersubjectivity of Translation].” Foreign Language Research3: 113–116.Search in Google Scholar

ChenD.2005. “Fanyi Yanjiu: Cong Zhutixing Xiang Zhuti Jianxing Zhuanxiang [From Subjectivity to Intersubjectivity: A Paradigm Shift in Translation Studies].” Chinese Translators Journal2: 3–9.Search in Google Scholar

ChenD.2007. “Fanyi Zhuti Jianxing Zhuanxiang De Zai Sikao—Jian Da Liu Xiaogang Xiansheng [Thinking Further the Intersubjective Turn in Translation Studies].” Foreign Languages Research2: 51–55.Search in Google Scholar

ChenY.2009. “Lun Yu Sange Yingyiben Fanyi Yanjiu De Gongneng Yuyanxue Tansuo [A Functional Analysis of Quotations from Lun Yu].” Foreign Languages and Their Teaching2: 49–52.Search in Google Scholar

ChenY.2010. “Lun Yu Yingyiben Yanjiu De Gongneng Yupian Fenxi Fangfa [A Functional Discourse Analysis of English Translations of Lun Yu].” Foreign Language and Literature1: 105–109.Search in Google Scholar

ChengG.2002. “Legge Yu Waley Lun Yu Yiwen Tixian De Yili Xitong De Bijiao Fenxi [A Comparative Analysis of the Philosophical Connotations Respectively Shown in Legge’s and Waley’s Translations of Lun Yu].” Confucius Studies2: 17–28.Search in Google Scholar

DavisK.[2001] 2004. Deconstruction and Translation. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

DerridaJ. J.1992. “From Des Tours De Babel.” In Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida, edited by R.Schulte and J.Biguenet, translated by J. F. Graham, 218–227. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

DobsonW. A.1963. Mencius: A New Translation Arranged and Annotated for the General Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.10.3138/9781442653825Search in Google Scholar

EscarpitR.1958. Sociologie De La Litérature. Paris: Presses Universitaries de France.Search in Google Scholar

FaircloughN.1989. Language and Power. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

FangX.2011. “Cong Daiweisen Yuyan Jiaoliu De ‘Sanjiao Celiang’ Moshi Kan Fanyi De Zhuti Jianxing [On the Intersubjectivity in Translation in the Light of Donald Davidson’s “Triangualation” Model of Communication by Language].” Foreign Language Research3: 117–120.Search in Google Scholar

FasoldR.[1990] 2000. The Sociolinguistics of Language. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

FuP. R.2006. Fu Peirong Jiedu Mengzi [Mengzi Interpreted by Fu Peirong]. Beijing: Thread-Binding Books Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

GaoY. M.2001. “Huayu Jidiao Moshi Tantao [Research on Models of Tenor of Discourse].” Journal of PlA University of Foreign Languages1: 1–5.Search in Google Scholar

GenetteG.1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by J. E. Lewin.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511549373Search in Google Scholar

GodinP. R.2010. “Review: Mencius by Irene Bloom.” Journal of Chinese Studies51: 381–383.Search in Google Scholar

GregoryM.1967. “Aspects of Varieties Differentiation.” Journal of Linguistics3 (2): 177–198. doi:10.1017/S0022226700016601.Search in Google Scholar

GregoryM., and S.Carroll. 1978. Language and Situation: Language Varieties and Their Social Contexts. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K.1994. Introduction to Functional Grammar. 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

HallidayM. A. K., and R.Hasan. 1985. Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective. Victoria, Australia: Deakin University Press.Search in Google Scholar

HasanR.1978. “Text in Systemic-Functional Model.” In Current Trends in Textlinguistics, edited by W. U.Dressler, 228–246. Berlin: Walter. de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110853759.228Search in Google Scholar

HatimB., and I.Mason. 1997. The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

HatimB., and I.Mason. [1990] 2001. Discourse and the Translator. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

HeW., and J.Zhang. 2013. “Lun Yu Yinan Zhangju De Yunei Fanyi Moshi [An Intralingual Translation Model for Controversies in Lun Yu].” Foreign Language Education6: 85–98.Search in Google Scholar

HeW., and J.Zhang. 2014. “Dianji Yingyi Zhong De ‘Xianxing Yuzhi’ He ‘Yinxing Yuzhi’—Yi Lun Yu Weizheng Pian (6) Wei Li [‘Over Tenor’ and ‘Covert Tenor’ in the Translation of Chinese Classics—A Case Study of Chapter 2 (6) of Lun Yu].” Foreign Languages in China1: 78–84.Search in Google Scholar

HeX. M.1995. “Mengzi “Tian” Lun Pouxi [Interpretation of Mengzi’s Concept of “Tian”].” Qilu Journal1: 60–64.Search in Google Scholar

HeZ. K.1999. Mencius. Beijing: Sinalingua.Search in Google Scholar

HuangG. W.2011. “Lun Yu De Pianzhang Jiegou Ji Yingyu Fanyi De Jige Wenti [The Textual Structure of Confucius Lun Yu (The Analects) in Relation to the English Translation of the Book].” Foreign Languages in China6: 88–95.Search in Google Scholar

HuangG. W.2012. “Dianji Fanyi: Cong Yunei Fanyi Dao Yuji Fanyi–Yi Lun Yu Yingyi Wei Li [A Unique Feature of Translating Ancient Chinese Works: From Intralingual Translation to Interlingual Translation].” Foreign Languages in China6: 16–21.Search in Google Scholar

HuangZ. L.2002. Bianyi Lilun [Theory of Translation Variation]. Beijing: China Translation and Publishing Corporation.Search in Google Scholar

HudsonR. A.[1996] 2000. Sociolinguistics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

JiH. Q.2011. “Mengzi Ji Qi Yingyi [Mencius and Its Translation into English].” Foreign Language Research1: 113–116.Search in Google Scholar

JiaoX.1987. Mengzi Zhengyi [Re-Interpretation of Mencius]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.Search in Google Scholar

JonkerD. R.1967. “Review: Mencius by W. A. C. H. Dobson.” T’oung Pao53 (4/5): 300–304.10.2307/2932444Search in Google Scholar

JonkerD. R.1973. “Review: Mencius by D. C. Lau.” T’oung Pao59 (1/5): 268–272.Search in Google Scholar

LauD. C.1970. Mencius. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

LeggeJ.1970. The Works of Mencius. 2nd ed. New York: Dover Publications.Search in Google Scholar

LiM.2006. “Cong Zhuti Jianxing Lilun Kan Wenxue Zuopin De Fuyi [Retranslation of Literary Works from the Perspective of Intersubjectivity].” Journal of Foreign Languages4: 66–72.Search in Google Scholar

LvT.1986. “The Author of Mengzi.” Confucius Studies3: 123–124.Search in Google Scholar

MartinJ. R.[1992] 2004. English Text: System and Structure. Beijing: Peking University Press.Search in Google Scholar

MundayJ.2008. Style and Ideology in Translation. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

NidaE.[1964] 2004. Toward a Science of Translating. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

NidaE., and C.Taber. [1969] 2004. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

NordC.2001. Translating as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

PanW. G.2002. “Dangdai Xifang De Fanyi Yanjiu–Jian Tan ‘Fanyixue’ De Xueke Xing Wenti [The Contemporary Western Translation Studies—A Discussion of the Disciplinarity of ‘Translation Studies’].” Chinese Translators Journal1: 31–34.Search in Google Scholar

PoyntonC.1984. “Forms and Functions: Names as Vocatives.” Nottingham Linguistic Circular13: 1–34.Search in Google Scholar

PoyntonC.1989. Language and Gender: Making the Difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

PoyntonC.1990. “Address and the Semiotics of Social Relations: A Systemic-Functional Account of Address Forms and Practices in Australian English.” PhD diss., University of Sydney. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-2-327.Search in Google Scholar

RaniK. S.2004. “Writer-Translator Discourse: Translating Australian Aboriginal Women’s Writing.” Translation Today1 (1): 163–170.Search in Google Scholar

RobinsonD.2001. Who Translates? Translator Subjectivities beyond Reason. Albany: State University of New York Press.Search in Google Scholar

SteinerG.[1998] 2001. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. 3rd ed. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

TouryG.[1995] 2001. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

Van NordenB. W.2008. Mengzi: With Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, .Search in Google Scholar

Van WykeB.2012. “Borges and Us: Exploring the Author-Translator Dynamic in Translation Workshops.” The Translator18 (1): 77–100. doi:10.1080/13556509.2012.10799502.Search in Google Scholar

VenutiL.1995. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

VenutiL.1998. The Scandals of Translation: Towards an Ethics of Difference. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203269701Search in Google Scholar

XuJ.2003. “Fanyi De Zhuti Jianxing Yu Shijie Ronghe [A Preliminary Study of Intersubjectivity and Perspective Integration in Translation].” Foreign Language Teaching and Research4: 290–295.Search in Google Scholar

YangB. J.1960. Mengzi Yizhu [A Translation of Mencius with Annotations]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.Search in Google Scholar

YangL.2005. “Fanyi ‘Jianxing Wenhua’ Lun [Interness as the Cultural Ideal of Translation].” Chinese Translators Journal3: 20–26.Search in Google Scholar

YuetK. L.2011. “Review: Mengzi: With Selections from Traditional Commentaries.” Philosophy East and West61 (2): 399–401. doi:10.1353/pew.2011.0024.Search in Google Scholar

ZengZ. Y.2008. “Cong Chutu Wenxian Zai Lun Xunzi ‘Tian’ Lun Zhexue Xingzhi [Concerning the Cultural Meaning of Xunzi ‘Tian’ Thought in New Archaeological Finds].” Qilu Journal4: 5–10.Search in Google Scholar

ZhangD. L.1991. “Role Relationships and Their Realization in Mood and Modality.” Text II, no. 2: 289–318. doi:10.1515/text.1.1991.11.2.289.Search in Google Scholar

ZhangD. L.1998. “Lun Huayu Jidiao De Fanwei Ji Tixian [On the Scope of Tenor of Discourse and Its Realization].” Foreign Language Teaching and Research1: 8–14.Search in Google Scholar

ZhaoQ.1999. Mengzi Zhushu [Exegeses of Mencius]. Beijing: Peking University Press.Search in Google Scholar

ZhaoZ. T., W. T.Zhang, and D. Z.Zhou. 1999. Mencius. Chashang: Hunan People’s Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

ZhuW.2009. “Huayu Jidiao Dongtai Gailan [A Review of the Trend of the Research on Tenor].” Foreign Languages and Their Teaching9: 14–17.Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Article

- Arabic language in Zanzibar: past, present, and future

- Is EFL students’ academic writing becoming more informal?

- Has the prose quality of science textbook improved over the past decade? A linguistic perspective

- The relationship between the author and the translator from the perspective of power of tenor of discourse: a case study of the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi

Articles in the same Issue

- Article

- Arabic language in Zanzibar: past, present, and future

- Is EFL students’ academic writing becoming more informal?

- Has the prose quality of science textbook improved over the past decade? A linguistic perspective

- The relationship between the author and the translator from the perspective of power of tenor of discourse: a case study of the peritexts of the translations of Mengzi