Translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English translation

-

Haru Deliana Dewi

ABSTRACT

This paper is a small part of my dissertation which particularly describes translation and language errors based on trends in Translation Studies. Translation and language errors are important to assess the quality of a translation product. However, little or almost none of the literature has discussed the translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English language pair. This study aims to discover the types of translation and language errors mostly found in the Indonesian–English translation. The data were obtained by conducting several projects in the translation classes of LBI (Lembaga Bahasa International – International Language Institution) of the Faculty of Humanities (FIB) of Universitas Indonesia (UI) for 2 years from 2013 to 2015 by asking the students to do translation from an Indonesian text into English. The results show that the most frequent errors occurring are incorrect usage, grammatical errors, and omissions. This paper can be considered as preliminary research on translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English language pair which should be further investigated.

1. Introduction

Translators, both novices and professionals, make errors (Séguinot 1990, 68) because humans have limited cognitive processing capacity or limitations on short-term memory (Séguinot 1989, 75), and because translators sometimes have vocabulary and knowledge gaps that are not always filled in time (1990, 68). Therefore, translation errors can be found almost in any translation, especially in the first draft. Nevertheless, what are translation errors? Are they different from language errors? Vinay and Dalbernet are among the earliest TS scholars who discuss translation errors, although they do not explicitly provide a definition of translation errors per se. They state that translation errors occur when translators do not carefully pay attention to the subtle differences of the meanings of words that on the surface appear to be interchangeable (1958/1995, 58).

The Canadian Language Quality Measurement System (SICAL).

| Major error | Minor error | |

|---|---|---|

| Translation error | Serious mistranslation Significant omission Nonsense | [Trivial] Mistranslation, Shift in Meaning Ambiguity, Addition, Omission |

| Language error | Unintelligible language Grossly incorrect language Unacceptable neologism | Diction Punctuation Syntax, Style, Morphology Cohesion Devices Spelling Others |

Translation error typology of Lee & Ronowick (Korean to English).

| Miscomprehension of source text | ||

|---|---|---|

| Causes of errors | Misuse of Korean | |

| Types of errors | Lexical errors | Incorrect word |

| Loan word | ||

| Word to be refined | ||

| Redundant word | ||

| Incorrect terminology | ||

| Collocation | ||

| Syntactical errors | Parts of speech | |

| Ending | ||

| Voice | ||

| Word order | ||

| Agreement | ||

| Incomplete sentence | ||

| Tautology | ||

| Omission | ||

| Hygiene errors | Spacing | |

| Punctuation | ||

| Results of errors | Distortion | |

| Ambiguity | ||

| TT unacceptability | ||

| Information loss | ||

| Significance of errors | Major | Minor |

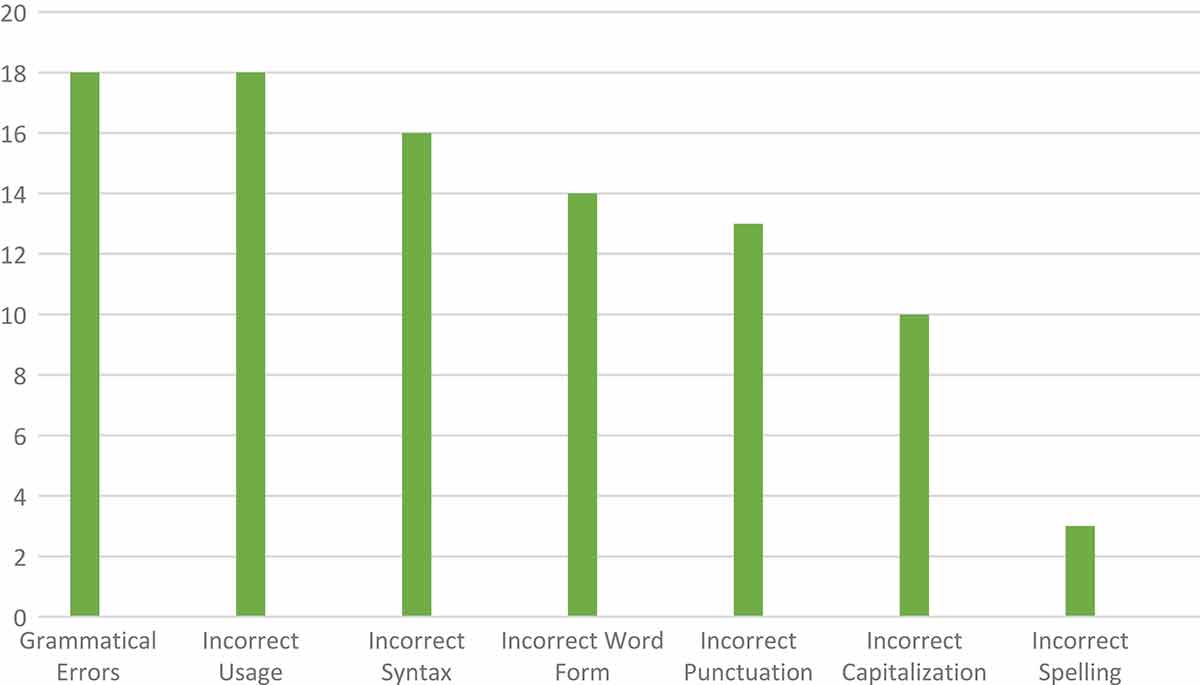

Types and frequency of errors from pilot project results.

| Types of errors | Frequency of errors | |

|---|---|---|

| Translation error | Addition errors | 14 |

| Ambiguity | 2 | |

| Incorrect terminology | 14 | |

| Incorrect word order | 4 | |

| Literalness or faithfulness | 4 | |

| Mistranslation | 10 | |

| Omission errors | 15 | |

| Language error | Grammatical errors | 18 |

| Incorrect capitalization | 10 | |

| Incorrect punctuation | 13 | |

| Incorrect spelling | 3 | |

| Incorrect syntax | 16 | |

| Incorrect usage | 18 | |

| Incorrect word form | 14 | |

Types and frequency of errors from the formal project results.

| Types of errors | Frequency of errors in paragraph 1 | Frequency of errors in paragraph 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Translation errors | Addition errors | 4 | 3 |

| Ambiguity | 0 | 0 | |

| Incorrect terminology | 2 | 2 | |

| Incorrect word order | 0 | 0 | |

| Literalness or faithfulness | 0 | 0 | |

| Mistranslation | 4 | 2 | |

| Omission errors | 7 | 10 | |

| Language errors | Grammatical errors | 13 | 12 |

| Incorrect capitalization | 0 | 1 | |

| Incorrect punctuation | 2 | 3 | |

| Incorrect spelling | 5 | 5 | |

| Incorrect syntax | 4 | 5 | |

| Incorrect usage | 11 | 13 | |

| Incorrect word form | 5 | 5 | |

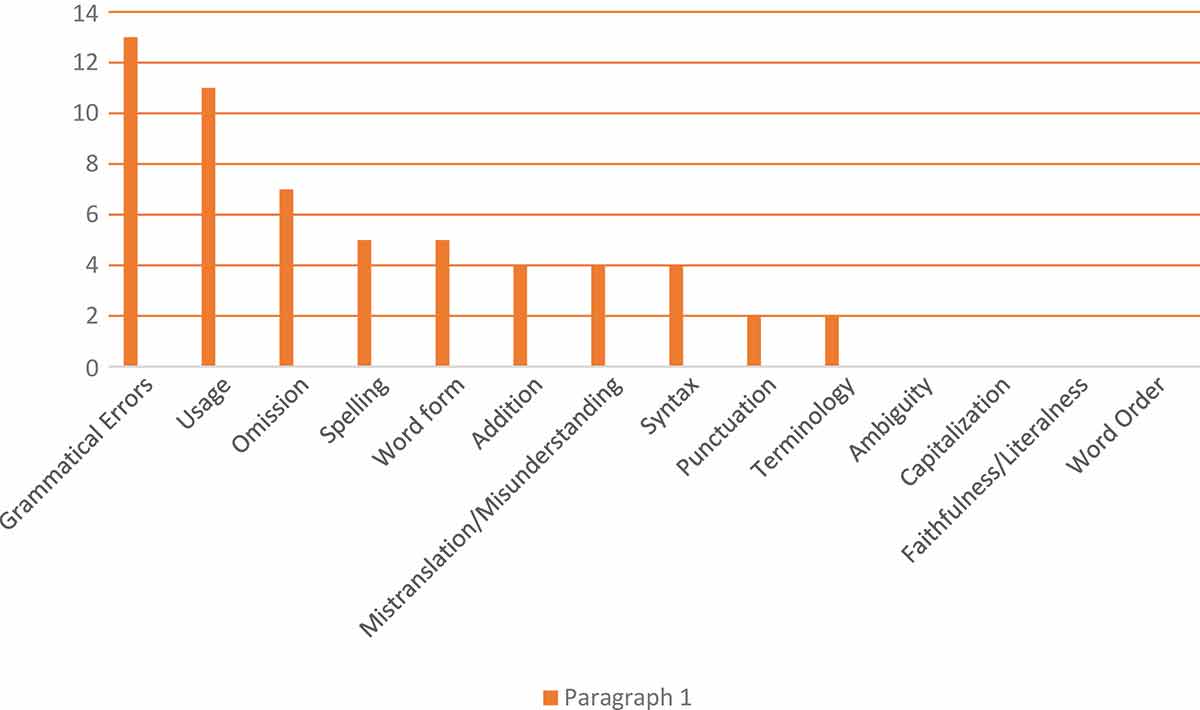

Types and frequency of all errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 1

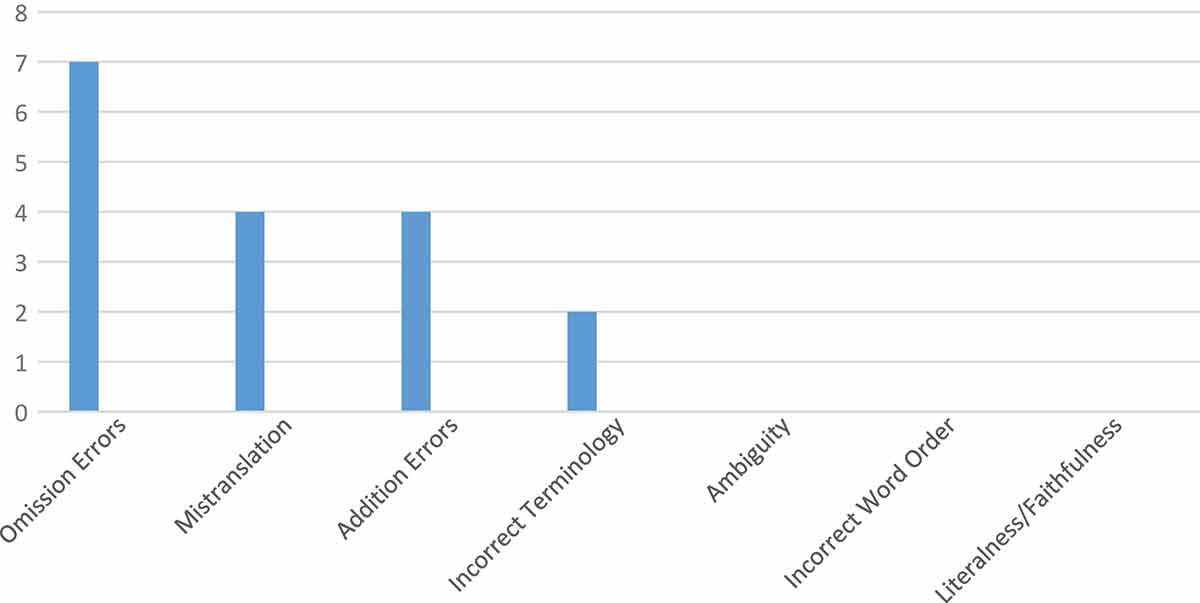

Types and frequency of translation errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 1

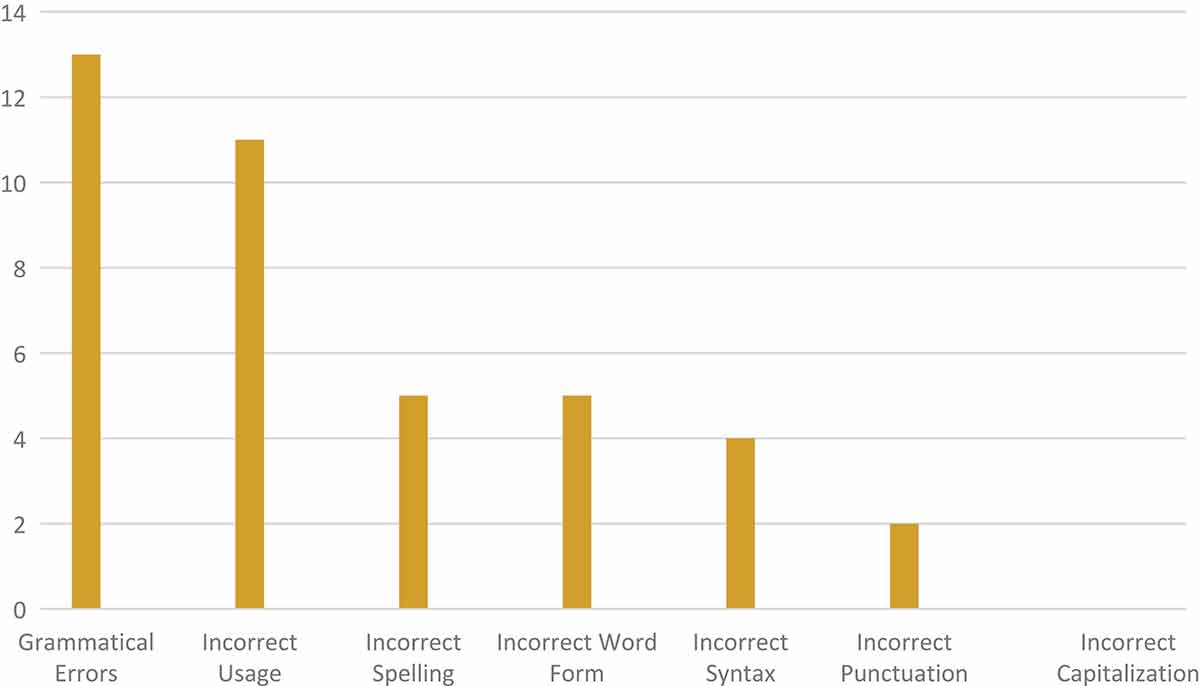

Types and frequency of language errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 1

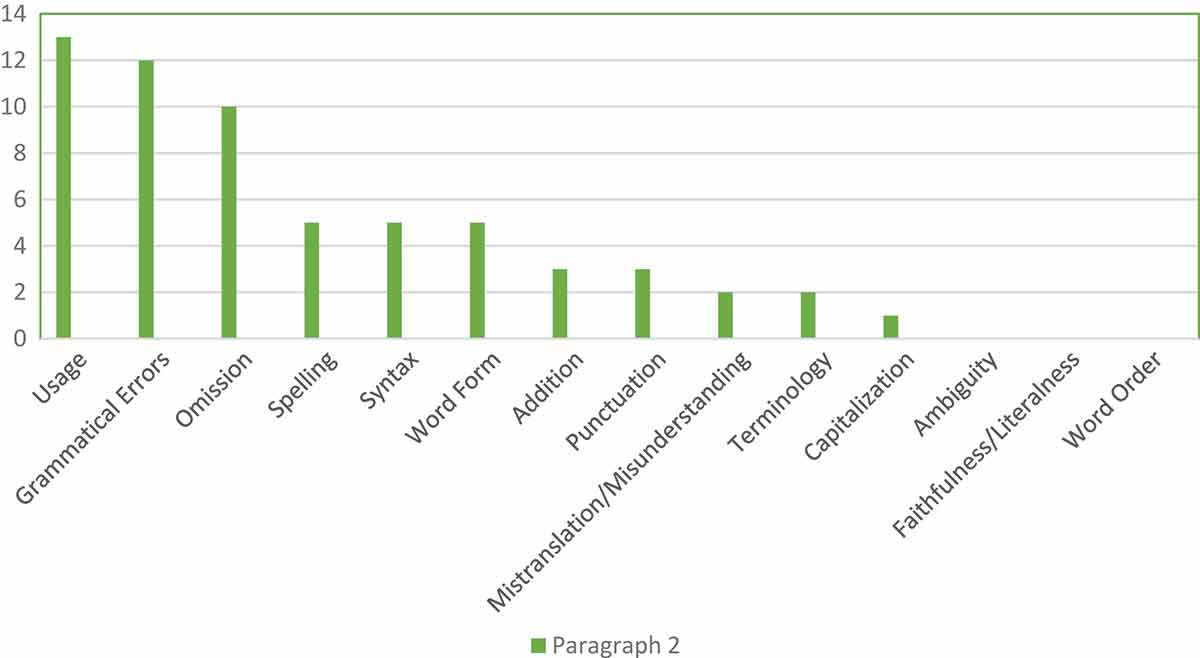

Types and frequency of all errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 2

Types and frequency of translation errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 2

Types and frequency of language errors from the formal project results.

Paragraph 2

Viewed from the standpoint of equivalence between a source text (ST) and a target text (TT), a translation error, according to Koller, is considered as nonequivalence between ST and TT or non-adequacy of the TT (1979, 216). Viewed from a functionalist approach, Sigrid Kupsch-Losereit (1985) was the first to introduce the notion of translation errors. Her definition of a translation error is as “an offence against: (1) the function of the translation, (2) the coherence of the text, (3) the text type or text form, (4) linguistic conventions, (5) culture- and situation-specific conventions and conditions, (6) the language system” (1985, 172). Williams provides a definition for a major translation error but not for a minor translation error. He explains that a major translation error is “the complete failure to render the meaning of a word or group of words conveying an essential part of the message of the document” (1989, 24). Nord states that translation errors happen due to structural distinctions in the syntax and suprasegmental features of the two languages (1997, 66). Based on the Skopos theory or functionalism, the definition of a translation error is stated “as a failure to carry out the instructions implied in the translation brief and as an inadequate solution to a translation problem” (75) and is an unsuccessful fulfilment of the TT-function and the receiver’s expectations (Schmitt 1998, 394; Nord 2009, 190).

Thus, based on these definitions, what a translation error is has a variety of meanings depending on translation theories and norms (Hansen 2010, 385). Hansen also states that translation errors appear since something “goes wrong” during the transfer and movement from the ST to the TT (Hansen 2010, 385). Then, Conde discusses the differences between language errors and translation errors. He maintains that language errors are found in the TT and are often similar to the errors on target language expression consisting of mistakes in vocabulary, syntax, grammar, punctuation, coherence, style, etc., whereas translation errors are “explained by the existence of a previous text: the source text upon which the target text depends” (2013, 98). Both Williams (1989) and Conde (2013) classify translation errors as errors of meaning. Lee and Ronowick also explain the differences between translation errors and language errors, which are similarly described by Conde (2013). They state that “translation errors, regardless of whether they are major or minor, are associated more with the source text, while language errors are associated more with the target text” (Lee & Ronowick 2014, 42).

This study applies two assessment models, the ATA Framework and the LBI Bandscale, as an effort to compare the effectiveness of those models in assessing translation for my dissertation. The ATA Framework was chosen as it is applied as an assessment rubric at the translation program classes of Kent State University where I studied for my Ph.D. This model is a translation assessment rubric of the American Translators’ Association (ATA) and provides a simple definition of a translation error. It is written in the form with the title ATA Framework for Error Marking (see Appendix 1) that translation errors are negative impact(s) on the understanding or use of a TT. Translation errors in this model are also called strategic or transfer errors. Moreover, this rubric also lists pure language and grammatical errors called mechanical errors. This model uses an error analysis approach which focuses on errors found in a translation result.

The other model used in this study, the LBI Bandscale, was chosen because it is used as the translation assessment rubric of the institution where I work now as the manager of the translation program. However, this model does not provide any definition of translation errors. It applies a holistic approach where it has descriptors describing the good and bad aspects of a translation result (see Appendix 1). It provides grades from A to D where A is the highest level and D is the lowest. It does not focus on errors, but it mentions several translation errors as also found in the ATA Framework, such as mistranslation, misunderstanding, and unclear, awkward, and ambiguous meanings and/or expressions.

Several Translation Studies scholars and translation assessment models have proposed their own error typologies. Chien states that up to now there have not been commonly agreed or confirmed categories of translation errors (2015, 91). In other words, there is still no universal translation error typology. This might be the case because, first, the definitions of translation errors vary according to different translation theories, which lead to different categorizations of errors as well. Second, different translation language pairs could result in different types of errors. In the following, we can see the different error typology proposed, including the error typology from these projects.

Williams divides errors into translation/transfer errors and language errors, and each consists of major and minor errors (1989, 2001). This error typology has been applied by SICAL (the Canadian Language Quality Measurement System) developed by Canadian government’s Translation Bureau where Williams was the head of the committee that designed the assessment model and that decided the categories of errors (1989, 23). Williams explains that there are three types of errors or defects in industrial quality control theory: critical, major, and minor (1989, 23). A critical error is defined as an error that can lead to dangerous or hazardous conditions for anyone applying the product with such an error. A major error is defined as an error resulting in failure or reducing the usability of the product with such an error. A minor error is defined as an error that will not reduce the usability of the product with such an error; in other words, this error will have only little impact on the effectiveness of a tool or a product (William 1989, 23).

Major translation errors, according to Williams, are the combination of critical and major errors as described for industry (24) and involve macro-level misinterpretations (2001, 331). The examples of major translation errors of SICAL described by Lee & Ronowick are serious mistranslation, significant omissions, and nonsense (2014, 43). In contrast, minor translation errors are microlevel misinterpretations (Williams 2001, 331), which include [trivial] mistranslations, shift in meaning, ambiguity, addition, and omission (2001, 328–333; Lee and Ronowicz 2014, 43). Furthermore, a major language error refers to a serious language error, such as an unwarranted neologism (Williams 1989, 24–25), unintelligible language, or grossly incorrect language (Lee and Ronowicz 2014, 43). Minor language errors are small errors, in word-level structures, which do not disrupt the meaning in the target text (Williams 2001, 331). His examples of minor language errors involve diction, punctuation, syntax, style, morphology, cohesion devices, spelling, and others (William 2001, 331; Lee and Ronowicz 2014, 43). Unfortunately, Williams and Lee & Ronowich do not provide definitions and examples of those types of errors. Table 1 above shows the SICAL error typology.

Pym has proposed two types of translation errors: binary errors and nonbinary errors. He explains that “a binary error opposes a wrong answer to the right answer,” so for this type of errors it is about “right” and “wrong” (1992, 282). Binary errors are typically very rapidly and punctually corrected (285). On the contrary, nonbinary errors or nonbinarism “requires that the target text actually selected be opposed to at least one further target text, which could also have been selected, and then to possible wrong answers” (282). There is a minimum of two right answers and two wrong answers for nonbinary errors (282). The time needed for correcting nonbinary errors can take long until there are no more significant differences (285). Pym maintains that all translational errors (as opposed to language errors) are nonbinary by definition (Pym’s definition), but nonbinary errors are not necessarily all translational (283).

For pedagogical purposes, Nord categorizes translation errors into four types: pragmatic, cultural, linguistic, and text-specific (1997, 64). Pragmatic translation errors occur because of insufficient solutions to translation-oriented understanding and resolution of pragmatic ambiguities posed by the source text (75). An example of a pragmatic translation problem is a lack of receiver orientation. According to Nord, this problem appears because there are differences between the source text and TT situations, and it can be identified by observing extratextual factors, such as sender, receiver, medium, time, place, motive, text function (65). For instance, when we translate a legal term from Indonesian to English, such as the expression putusan sela, the translation tends to be “(court) decision” as it is the literal translation of the term; however, it should be translated as “order” because functionally it is the meaning. Thus, to avoid this type of pragmatic translation errors, we must pay attention to the function of a term or an expression in the TT. The second type of translation errors is cultural translation errors. These errors occur “due to an inadequate decision with regard to reproduction or adaptation of cultural-specific conventions” (75). Because conventions from one culture to another are not the same, cultural translation errors will be different for different language pairs (66).

The third type of translation errors is linguistic translation errors. These errors are caused by inadequate translation when the focus is on language structures, such as in foreign language classes (75). Linguistic translation errors are restricted to language pairs since structural differences in the syntax and suprasegmental features of one language pair might be different from those of another language pair (66). The fourth type of translation errors is text-specific translation errors. These errors, of course, depend on the text translated and are typically evaluated from a functional or pragmatic point of view (76). Solutions to these text-specific errors can never be generalized and cannot even be applied to similar cases. The examples of these errors are incorrect figures of speech, improperly formed neologisms or puns, etc. (67).

Hansen categorizes translation errors into pragmatic, text linguistic, semantic, idiomatic, stylistic, morphological, and syntactical errors (2009, 2010). Pragmatic errors refer to misinterpretation of the translation brief and/or the communication situation (2009, 320). The examples of these errors are an incorrect translation type, lack of important information, unwarranted omission of ST units, too much information related to the ST and/or the TT receiver’s needs in the situation, disregarding norms and conventions as to genre, style, register, abbreviations, etc. (2009, 320). Text-linguistic errors constitute a violation of the semantic, logical, or stylistic coherence, such as incoherent text caused by incorrect connectors or particles, incorrect or vague reference to phenomena, unclear temporal cohesion, incorrect category (using active voice instead of passive voice, or the other way around), incorrect modality, incorrect information structure caused by word order problems, and unmotivated change of style (320–321).

Semantic (lexical) errors are incorrect choices of words or phrases (321). Idiomatic errors are semantically correct words and phrases, but these errors will not be used in an analogous context in the TL. Stylistic errors refer to incorrect choices of stylistic level, stylistic elements, and stylistic devices. Morphological errors, also called “morpho-syntactical errors,” include incorrect word structure or mistakes in number, gender, or case. Syntactical errors include incorrect sentence structure, for example (321).

Angelone describes several translation errors which are quite similar to Hansen’s list, but there are a few which are different. His study focuses on lexical errors, syntactic errors, stylistic errors, and mistranslation errors (2013, 263). Lexical errors refer to using incorrect terminology, false cognates, and incorrect or weak collocations. Syntactic errors include errors in word order, verb tense, incomplete or run-on sentences, and subject-verb agreement. Stylistic errors are caused by inappropriate register, lexical or grammatical inconsistency, or lexical and grammatical redundancy. Mistranslation errors happen due to inappropriate additions or omissions and errors causing incorrect meaning transfer to appear (2013, 263).

Lee & Ronowick have their own categories of translation errors based on the Korean–English translation. Their framework of error typology includes the causes of errors, the types of errors, the results of errors, and the significance of errors (2014, 47). Below is the table containing the framework or error typology from Lee & Ronowick (Table 2).

Lee & Ronowick explain that the “causes of errors” category aims to identify which of the two languages is the source of errors in the translations. They describe in their framework that the causes of errors derive from errors in the comprehension and reformulation phases (2014, 47). More specifically, in the Korean–English translation, the causes of errors are from the misinterpretation of the source text, such as misunderstanding of words, phrases, and clauses of the source text (48–49). “Types of errors” refer to the skills and knowledge of students that must be improved, and there are three types of errors in this study: lexical (incorrect word, loan word, word to be refined, redundant word, incorrect terminology, collocation), syntactical (parts of speech, ending, voice, word order, agreement, incomplete sentence, tautology, omission), and “hygiene” (spacing, punctuation) errors (48–49).

Lee & Ronowick explain that “results of errors” involve the impacts resulting from the different types of errors (48). These results of errors have three aspects: (1) fidelity in meaning transfer from the ST to the TT, such as distortion and ambiguity, (2) grammar in the TT, such as TT unacceptability, and (3) the coverage of content, such as information loss. Then, “significance of errors” in their study is adopted from the NAATI and SICAL methods of assessment, and this aims to decide if translations are good or bad. This significance of errors consists of major and minor errors, and the concept of these major and minor errors follows the concept discussed by SICAL and NAATI. They further explain that minor errors include easily corrected errors in the TT without analyzing the ST and simple language errors. Major errors include errors that require analysis of the ST and errors that cause the TT to be incomprehensible (48).

Based on the literature review above, there have been many scholars from several countries discussing the definitions of translation errors and the types of translation errors. However, the translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English language pair have not been researched and discovered. Thus, this study aims to reveal the types of translation and language errors and to discover the most frequent translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English translation results via several projects conducted in translation classes of LBI FIB UI in Jakarta, Indonesia. These translation error types will be based on the types found in the ATA Framework.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and informed consent

The projects conducted from September 2013 to May 2015 were actually meant to obtain data for my dissertation. Some of the data, however, are about translation and language errors, which become the focus of this paper. The research projects were held at the Indonesian–English general translation classes of LBI FIB UI in Salemba, Central Jakarta, Indonesia. LBI is a business venture under the Faculty of Humanities (FIB) of Universitas Indonesia (UI) and has three (3) subdivisions: PPB for teaching foreign languages, BIPA for teaching Indonesian language for foreigners, and PPP for translation and interpreting services and training. The terms of classes in LBI are divided into 3 terms in 1 year. One term consists of 10 weeks or almost 3 months. Term 1 starts in January and ends in April, term 2 starts in May and ends in August, and term 3 starts in September and ends in December. Thus, there were five (terms) of classes included in the study, namely term 3/2013, term 1/2014, term 2/2014, term 3/2014, and term 1/2015.

The respondents of the research were the participants of the general translation classes, and the number was different from one term to another. In term 3/2013 there were 13 respondents, 5 in term 1/2014, 4 in term 2/2014, 6 in term 3/2015, and 3 in term 1/2015. The total number of respondents is 31. Despite a long period of data collection time, the number of respondents who were willing to participate in the projects was low, as the number of students registered to the Indonesian–English general translation class of PPP LBI UI per term is not high, only between 5 and 15 maximum. The age of the participants varies from their 20s to their 50s, and their occupation also varies, from employees, teachers, students, self-employed, to housewives. All respondents are native Indonesians whose English proficiency is at least at intermediate level since they had to pass the placement test before joining the translation class. Before conducting the projects, the respondents were asked to sign a consent form, and this form can be seen in Appendix 3.

2.2. Research design

As previously explained, this study is part of my dissertation research which compares the effectiveness of two different models of translation assessment, the ATA Framework which applied an error analysis approach and the LBI Bandscale which adopts a holistic approach. In comparing those two models, I used quantitative and qualitative methods, and in the quantitative method translation and language errors were counted in the translation results, some of which were assessed using the ATA Framework and some others using the LBI Bandscale. However, the determination of the translation and language errors found applied the list in the ATA Framework as it provides the detailed types of those errors, while the LBI Bandscale does not contain the list of errors. Nevertheless, the calculation of the errors did not apply the scale used by the ATA Framework where each error might have different weight; instead, each error was counted as one, for the focus lied in the types and frequency of those errors found.

The study began with pilot projects in term 3/2013 and term 1/2014 to test the validity and reliability of the research instruments and variables. After the pilot projects, the formal projects were conducted in term 2/2014, term 3/2014, and term 1/2015. In each project, the respondents were requested to do translation, and then their translation results were assessed by me as the researcher and returned to the respondents to be revised by them. The translation results were assessed using those two aforementioned assessment models: (1) the ATA Framework, which is an assessment rubric used by the American Translator Association to assess the results of translation qualification (see Appendix 1) and (2) the LBI Bandscale, which is an assessment rubric used by LBI FIB UI to assess the translation class participants’ exam results (see Appendix 1). The participants were asked to improve their translation based on the feedback and the translation assessment model they obtained. The projects were continued by requesting the respondents to fill in an online survey after they submitted their revised work to the researcher. Those complete steps of the projects were necessary for the data collection of my dissertation; however, for translation errors, the data were sufficiently collected from the phase after the respondents finished doing their translation. Thus, it was not necessary to include the data from the second phase when the respondents returned the second version of their translation after they revised it.

2.3. Data sources and data analysis

As aforementioned that the data for translation errors were obtained from the translation results of the respondents or from the first phase of the projects. The material used in the pilot projects is different from the material used in the formal projects. In the pilot projects, the Indonesian ST is a nontechnical text which consists of 182 words. The title is Tembus Rekor Lagi, Penggangguran di 17 Negara Pengguna Euro Capai 19,38 Juta (Breaking the Record Again, the Unemployment Rate in 17 Euro Countries Reaches 19.38 Millions). It was taken from an Indonesian news website (http://finance.detik.com/read/2013/06/01/103621/2262089/4/tembus-rekor-lagi-pengangguran-di-17-negara-pengguna-euro-capai-1938-juta?), and it is about the increase in the unemployment rate in Euro countries. The ST used in the formal projects is also a nontechnical text, but it consists of 2 paragraphs with the total of 314 words. This first paragraph is about the high tuition fee for a special international school in Indonesia named Rintisan Sekolah Bertaraf Internasional (Pioneered International Standard School) or RSBI for short, and it consists of 183 words. The second paragraph is about the use of English as the language of instructions in RSBI in Indonesia, and it consists of 131 words. The STs of both projects can be seen in Appendix 2.

Those data on translation errors were analyzed using the ATA Framework because it contains types of translation errors. In this framework, the translation errors are not divided into major and minor. Instead, the errors are categorized into translation/strategic/transfer errors and mechanical errors and weighted according to an exponential scale of 1/2/4/8/16, which takes the place of the notion of minor and major. When an error type is given the value 1/2/4, it means the error is considered minor. When it receives a value 8 or 16, it means the error is major. As described above, translation errors in this model refer to negative impact(s) on understanding or use of a TT. These errors include mistranslation (MT), misunderstanding (MU), addition (A), omission (O), terminology or word choice (T), register (R), faithfulness (F), literalness (L), faux ami (FA – false friend), cohesion (COH), ambiguity (AMB), style (ST – inappropriate for specified type of text), and other (OTH – if there are other types of errors that have not been covered in these translation errors). Mechanical errors in this model refer to negative impact(s) on overall quality of a TT. These errors include grammar (G), syntax (SYN – phrase/clause/sentence structure), punctuation (P), spelling or character (SP/CH), diacritical marks or accents (D), capitalization (C), word form or part of speech (WF/PS), usage (U), and others (OTH – if there are other types of mechanical errors that have not been covered). The points for G, SYN, P, WF/PS, U, and OTH can be 1, 2, or 4, and the points for SP/CH, D, and C can be 1 or 2. The rational for the scale is that the reader of the TT will likely notice the error, perhaps be irritated by it, but will not misread the message of the test.

In contrast, the LBI Bandscale has no list of errors. It presents a set of model scales, each of which focuses on the translator’s understanding or comprehension of the ST and on the translator’s rendition of the TT. There are several types or error mentioned, but not described or explained in this model, such as spelling errors, punctuation errors, incorrect terminology or word choices, collocation errors, and misunderstandings. Nor does this model categorize errors into major and minor, and there are no points to scale the errors mentioned. Each grade provided (A, B, C, and D) refers to overall performance, the strengths and the weaknesses of a translation result. Hence, this rubric cannot be applied to analyze the translation and language errors found from the project translation results.

3. Findings and discussion

In these projects where the respondents were asked to translate from Indonesian to English, a number of error types were discovered. As the error types follow the list in the ATA Framework, those are divided into translation errors and mechanical or language errors. The translation errors include incorrect terminology, mistranslation, literalness/faithfulness (considered as one type of error since the difference between the two cannot be seen obviously in the translation results), ambiguity, omission, addition, and incorrect word order. The errors related to misunderstanding of the ST, register, faux ami (false friend), cohesion, style, indecision, inconsistency, and failure to use items mentioned in class were not found in the translation results. Moreover, the language errors discovered are incorrect usage, incorrect syntax, incorrect capitalization, incorrect punctuation, incorrect spelling, grammatical errors, and incorrect word form. Errors of diacritics were not found in the translation results. The analysis, first, will start from the pilot projects and then continued with the results of the formal projects. In the end, the results from both projects will be combined to discover the frequency and the types of the translation and language errors of this study. The errors were counted based on the types that occurred in each respondent’s translation result. Hence, for instance, when there are three errors of terminology in one result, it will be considered as one type of error occurring.

Before the discussion of each of the project results, types of translation and language errors need to be explained in detail first. The order of the explanation of the errors is not based on the most common to the least common, but it starts from the most serious error to the least serious error. The first translation error is mistranslation which reflects the change of the meaning or the introduction of different meanings in the TT from the ST. The second is literalness or faithfulness errors that refer to the expressions in the TT being translated very close to the meaning and to the structure of the expressions in the ST, so the translation becomes awkward or the meaning is not transferred correctly. The third one is incorrect terminology, which means the wrong, improper, or uncommon translation of a term. The fourth error is ambiguity errors that include words and expressions having ambiguous or unclear meanings. The fifth is omission errors which occur when there are expressions, sentences, words, articles, and prepositions missing or not translated into the TT. The sixth is addition errors that happen when there are unnecessary expressions, sentences, words, articles, prepositions added to the translation, and when there is redundancy. The seventh is incorrect word order that involves putting a word or an expression in an uncommon or inappropriate location in a sentence, although it might not interrupt the meaning of the whole sentence or the entire TT.

For the first serious language error, it is incorrect syntax which includes run-on-sentences and incorrect sentence structure. The second is incorrect usage, which refers to awkward expressions, incorrect words or expressions, unclear expressions, and inappropriate expressions. The third is grammatical errors which include singular-plural and countable-uncountable errors, incorrect tenses, incorrect articles, incorrect prepositions, incorrect connectors, problems with subject-verb agreement, and problems with active-passive voice. The fourth is incorrect word form that involves not the right forms of a word. The fifth is incorrect capitalization, which means that a letter (usually the first letter) in a word should be in a capital letter, but it is not, or a letter should not be in a capital form, but it is. The sixth error is incorrect punctuation which refers to the wrong or inappropriate use of punctuation. The seventh or the least serious language error found is incorrect spelling which refers to the wrong spelling of a word.

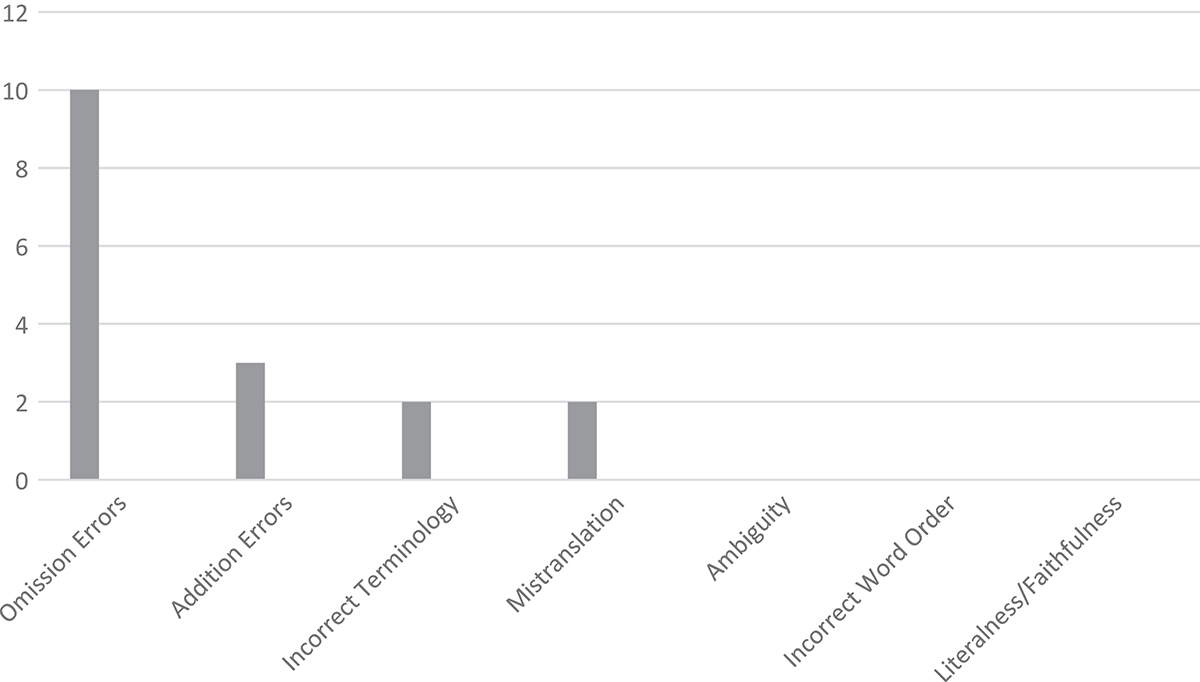

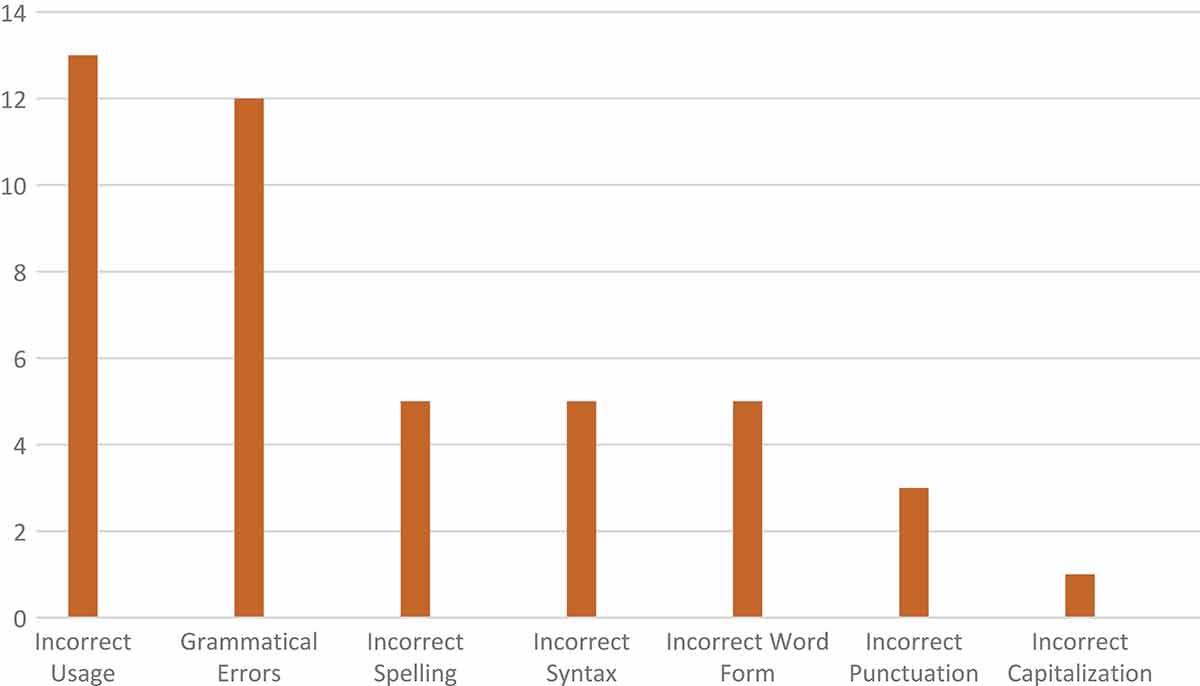

3.1. First project results

In these projects, conducted from September 2013 to April 2014, there were 18 respondents that submitted their translation to the researcher. There were 13 respondents from term 3/2013 and 5 respondents from term 1/2014. Respondents from one term to another were different people. Below are the table and the figures showing the types and frequency of errors from the pilot project results (Table 3, Figures 1–3). The errors in Table 3 have been arranged alphabetically, while the errors in Figures 1–3 are arranged based on the frequency they occur from the most common to the least common.

Types and frequency of all errors from the pilot project results.

Frequency of translation errors from pilot project results.

Frequency of language errors from pilot project results.

Based on the table and the figures below (Table 3, Figures 1–3), the first most common translation error is omission. In the ST, after the title, it shows the time 10:36 WIB, but some respondents decided not to translate WIB (Western Indonesian Time) into the English text, while the abbreviation has an important function to show the exact time when the news was published, so it should not be omitted. The second most common errors are incorrect addition and incorrect terminology. An example for incorrect addition is in the phrase “24.4% percentage”, as it is redundant to put the word “percentage” after the symbol %. For the incorrect terminology, for instance, EUROSTAT stands for Statistical Office of European Communities; however, several respondents wrote “European Union Statistic’s Agency” or “Europe Statistic Commission Office,” which is incorrect. The third most common error is mistranslation. For example, in the ST of the pilot projects, it is mentioned that “for this month the unemployment rate reached 12.2%, while in the previous month it was 10%, so the increase is 2.2%.” However, several respondents misunderstood the text, and they translated that “the increase was 10% from the previous month.” The fourth most common errors are faithfulness/literalness and incorrect word order. One example for faithfulness/literalness is the expression “17 Euro users” is a literal translation from the Indonesian ST, while the appropriate translation should be “17 Euro country users.” An example for incorrect word order is a time phrase ‘in April 2013ʹ was put in the middle of a sentence “The youth unemployment below 25 in April 2013 reached 36 million…”, while it should be at the end of the sentence, although the meaning of that sentence is not really disturbed. The fifth most common error is ambiguity. For example, the sentence “the lowest number of unemployment is Austria with 4.9%” is confusing and unclear, as it should be “Austria has the lowest number of unemployed with 4.9%.”

The first most common language errors found in the pilot projects are grammatical errors and incorrect usage. Some of the examples of grammatical errors are the problem with subject-verb agreement and wrong tenses. For instance, in the sentence “the unemployment rate are increasing to 95 thousand people in April 2013”, it consists of two grammatical errors, as the verb should be for a singular subject and the tense should be in a simple past tense, so the right sentence should be “the unemployment rate increased to 95 thousand people in April 2013.” An example for incorrect usage is the expression “the number of unemployment,” which should be “the number of unemployed” or “unemployment rate.” The second most common error is incorrect syntax, and an example can be found in the sentence “…the unemployment rate in Germany is 5.4%%, while in Luxemberg is 5.6%.” In that sentence, after the connector “while” there should be a subject before the verb “is”; without the subject the clause is incomplete and wrong. The third most common error is incorrect word form. One example of incorrect word form is in the following phrase “an additional of 95 thousand people”, as the word “additional” (an adjective) should be “addition” (a noun) in that phrase. The fourth most common error is incorrect punctuation. For example, in English we must use a comma for the number above a thousand, such as 1,200, and not a period (e.g., 1.200) as in Indonesian. The fifth most common error is incorrect capitalization. For incorrect capitalization, for instance, one of the respondents wrote the word “user” as part of the title of the text all in a small letter, whereas the letter “u” must be in a capital letter (“User”) because the word “user” is an important word. The sixth most common error is incorrect spelling. For instance, the word “quite” was written “quiet,” or the word “economist” was written “ekonomist.”

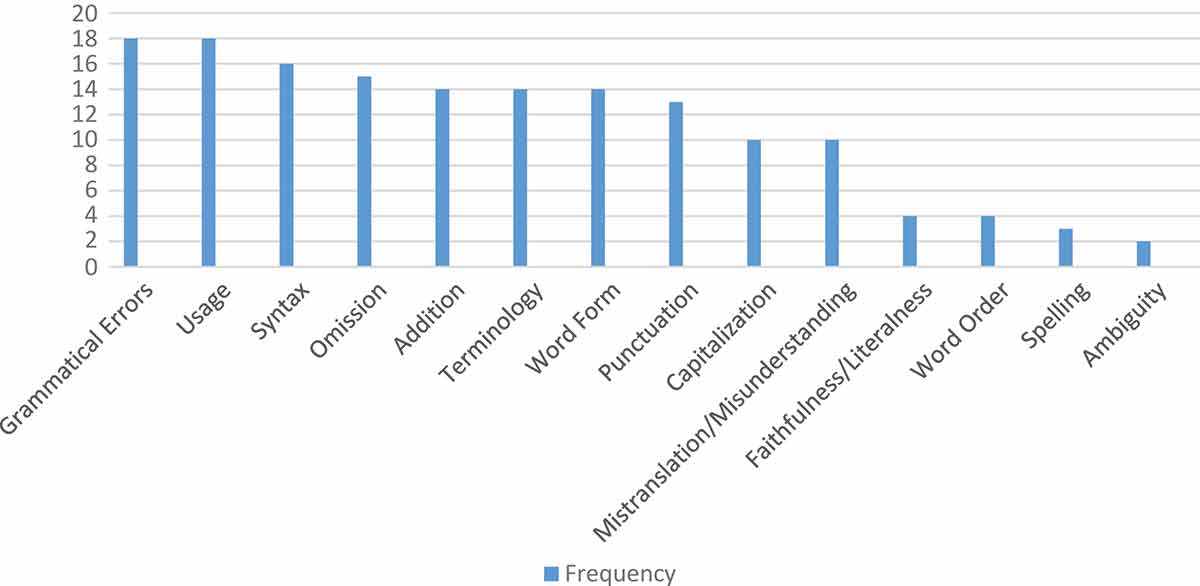

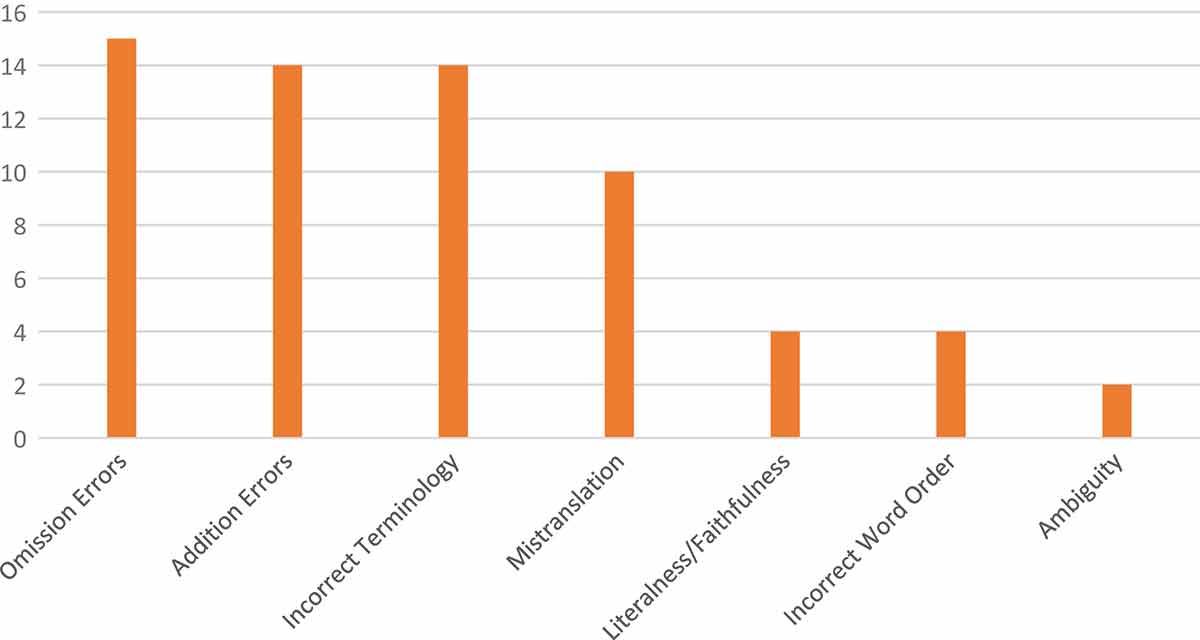

3.2. Formal project results

Formal projects were conducted from May 2014 to April 2015, and there were 13 respondents submitting their translation, 4 from term 2/2014, 6 from term 3/2014, and 3 from term 1/2015. The respondents from one term to another are not the same people. Below are the table and the figures showing the types and frequency of all errors from the formal project results (Table 4, Figures 4–6). The errors in Table 4 have been arranged alphabetically, while the errors in the figures (Figures 4–6) are arranged based on the frequency they occur from the most common to the least common. The results from paragraph 1 and from paragraph 2 are shown separately.

In Paragraph 1, the first most common translation error is incorrect omission. For example, in a sentence “most agreed that government task is to provide good quality education…”, there are three important thing omitted, namely: (1) after the word “most” it has to be added with a noun (people, persons, or participants) to make it clear; (2) after “that” the article “the” must be added; and (3) after “government” it has to be added with ’s. Thus, the correct sentence becomes: “most people agreed that the government’s task is to provide good quality education….” The second most common errors are incorrect addition and mistranslation. An example of incorrect addition is found in a phrase “The news on expensive tuition fee” as the subtitle of Paragraph 1, while the correct should be “News on expensive tuition fee”, so the article “the” becomes unnecessary addition. For mistranslation, an example is in a sentence “…they are mostly poor…,” while it is supposed to be “…they are from poor family….” Thus, there is a little misunderstanding there or there is a little different meaning by putting the word “mostly.” The third most common error is incorrect terminology. For incorrect terminology, for instance, the term “education fee” is not the same with “tuition fee”, as education fee is more general and more abstract than tuition fee. What is surprising is that there are no errors of ambiguity, faithfulness/literalness, and word order found in the translation results of Paragraph 1.

The first most common language error is grammatical errors. An example of this type of error is the problem with subject-verb agreement in a sentence “There is also students….”, while “is” should be “are” because the subject is “students.” The second most common error is incorrect usage. For instance, the expression “Most FGD members…” is not the right one because FGD is a Focus Group Discussion, not an organization, an association, or a group which has members. It is more appropriate to use the word “participants.” The third most common errors are incorrect spelling and incorrect word form. For incorrect spelling, for instance, the word “tuition” was written “tution” by one of the respondents. An example for incorrect word form can be found in the phrase “the expensive of tuition fee”, while it should be “the expensiveness of tuition fee” as “expensive” is an adjective and “expensiveness” is a noun which is the proper form of word in that phrase. The fourth most common error is incorrect syntax. An example of incorrect syntax can be found in the sentence “However, different fees in which determined by each school make…,” as the clause “in which determined” is definitely incorrect because there is no subject of that clause, and the verb should be in a passive voice. The fifth most common error is incorrect punctuation. An example for incorrect punctuation is found in the sentence “Some members who agree with the news, state that…”, as it is wrong to put a comma between the word “news” and the word “state”. There should not be any comma there. There is no incorrect capitalization in this paragraph translation results.

Moreover, in Paragraph 2 (Table 4, Figures 7–9) the first most common translation error is incorrect omission. For example, in a subtitle of Paragraph 2, a respondent wrote the translation as follows: “English as the Language of Instruction,” while the word “berita” (news) from the ST is not translated in the TT, or it is omitted. It should be “News on English as the Language of Instruction.” The second most common error is incorrect addition. An example for incorrect addition is found in the sentence “Besides the teacher’s incapability and unpreparedness, not all students also have the same capability in speaking English.” The word “also” is redundant addition, as at the beginning of the sentence there is the transition “Besides.” The third most common errors are mistranslation and incorrect terminology. An example of mistranslation/misunderstanding can be found in the sentence “…the schools were considered to force themselves to have English as the language of instruction.’ However, the correct message from the ST is “there are schools that force their teachers to apply English as the language of instruction.” Hence, there is a slight different meaning. An example for incorrect terminology is the term “Lingua Franca” or “Bridge Language” which is not the proper term for “the Language of Instruction.” There are no errors of ambiguity, faithfulness/literalness, and word order in the translation results of Paragraph 2.

The first most common language error is incorrect usage. For example, in the expression “the introductory language”, the correct one should be “the language of instruction.” The second most common error is grammatical errors. For instance, in a sentence “….that only some schools used English as the language of Instruction…,” the verb must be in a present tense (“use”), not in a simple past because it is a fact that some schools in Jakarta use English as the language of instruction. The third most common errors are incorrect spelling, incorrect syntax, and incorrect word form. An example for incorrect spelling is the word “itselves,” while it is supposed to be “itself.” An example for incorrect syntax can be found in the sentence “In addition, to all the teachers who have not been able and ready, as well as students whose English language abilities are not evenly distributed” it is not clear what is the main subject of that sentence. Another example of incorrect syntax, in a dependent clause “…if Indonesian values to be instilled,” this clause has no subject and no verb, and it is more like a phrase than a clause. An example of incorrect word form is in a phrase “nationality values” where the word ‘nationality (a noun) should be “national” (an adjective), so the correct one is “national values.” The fourth most common error is incorrect punctuation. For incorrect punctuation, for instance, in a sentence “It means, the government policy is considered right,” the comma between the word “means” and the word “the government” should not exist. The fifth most common error is incorrect capitalization. For instance, one of the respondents wrote: “however, it was….” The word “however” is located at the beginning of a sentence, so it should be “However, it was….”

4. Conclusion

Based on the results of the projects, we can discover that there are 14 types of errors occurring from the Indonesian–English translation results. Seven errors are translation errors, and the other seven are language errors. The translation errors found are incorrect terminology, mistranslation, literalness/faithfulness, ambiguity, omission, addition, and incorrect word order. The language errors discovered are incorrect usage, incorrect syntax, incorrect capitalization, incorrect punctuation, incorrect spelling, grammatical errors, and incorrect word form. The ST of the pilot projects is different from that of the formal projects, so the result discussion of the two projects is separated. However, we can conclude that the most common errors from both project results are language errors, such as grammatical errors and incorrect usage. However, the least common errors in the pilot project results are faithfulness/literalness, incorrect word order, and ambiguity for the translation errors, and incorrect spelling for the language error. The least common errors in the formal project results for Paragraph 1 are incorrect punctuation (a language error) and incorrect terminology (a translation error), and there are no errors of ambiguity, capitalization, faithfulness/literalness, and word order. For Paragraph 2, the least common errors are mistranslation/misunderstanding, incorrect terminology, and incorrect capitalization, and there are no errors of ambiguity, faithfulness/literalness, and incorrect word order.

The findings of this study should be considered as preliminary results, as this research is just an early study of this type of research. Further research is required to acquire more data to confirm more scientific results. Another study that should be conducted in the future is about the translation and language errors from English to Indonesian translation results, as English translation and language errors and Indonesian translation and language errors must be different. Thus, the classification of Indonesian translation and language errors is expected to be dissimilar from the results of this study. So far, there has not been any research on such topic yet.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

AngeloneE.2013. “The Impact of Process Protocol Self-Analysis on Errors in the Translation Product.” In Translation and Interpreting Studies, edited by B. E.Dimitrova, U.Norberg, S.Hubscher-Davidson, and M.Ehrensberger-Dow, 8(2), 253–271. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

ChienC.-W.2015. “EFL Undergraduates’ Awareness of Translation Errors in Their Everyday Environment.” Journal of Language Teaching and Research6 (1): 91–98. doi:10.17507/jltr.0601.11.Search in Google Scholar

CondeT.2013. “Translation Versus Language Errors in Translation Evaluation.” In Assessment Issues in Language Translation and Interpreting, edited by D.Tsagari and R.van Deemter, 97–112. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

HansenG.2009. “A Classification of Errors in Translation and Revision.” In Enhancing Translation Quality: Ways, Means, Methods, edited by H.Lee-Jahnke, P. A.Schmitt, and M.Forstner, 313–327. CIUTI-Forum 2008.Search in Google Scholar

HansenG.2010. “Translation ‘Errors’.” In Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Y.Gambier and L.van Doorslaer, 385–388. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/hts.1.tra3Search in Google Scholar

KollerW.1979. Einführung in die Űbersetzungswissenschaft [Introduction to Translation Studies/Science]. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.Search in Google Scholar

Kupsch-LosereitS.1985. “The Problem of Translation Error Evaluation.” In Translation in Foreign Language Teaching and Testing, edited by C.Tietford and A. E.Hieke, 169–179. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.Search in Google Scholar

LeeY. O., and E.Ronowicz. 2014. “The Development of an Error Typology to Assess Translation from English into Korean in Class.” Babel60 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1075/babel.60.1.03lee.Search in Google Scholar

NordC.1997. Translating as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Manchester, UK: St Jerome Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

NordC.2009. Textanalyse und Űbersetzen [Text Analysis and Translation]. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.Search in Google Scholar

PymA.1992. “Translation Error Analysis and the Interface with Language Teaching.” In Teaching Translation and Interpreting: Training, Talent, and Experience (Papers from the First Language International Conference), edited by C.Dollerup and A.Loddegaard, 279–290. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.56.42pymSearch in Google Scholar

SchmittP. A.1998. “Qualitätsmanagement (Quality Management).” In Handbuch Translation (The Handbook of Translation), edited by M.Snell-Hornby, H. G.Hönig, P.Kussmaul, and P. A.Schmitt, 394–399. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.Search in Google Scholar

SéguinotC.1989. “Understanding Why Translators Make Mistakes.” TTR (Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction)2 (2): 73–102. doi:10.7202/037047ar.Search in Google Scholar

SéguinotC.1990. “Interpreting Errors in Translation.” Meta25 (1): 68–73. doi:10.7202/004078ar.Search in Google Scholar

VinayJ., and J.Darbelnet. 1958/1995. Comparative Stylistics of French and English. Amsterdam &Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.11Search in Google Scholar

WilliamsM.1989. “The Assessment of Professional Translation Quality: Creating Credibility Out of Chaos.” TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction2 (2): 13–33. doi:10.7202/037044ar.Search in Google Scholar

WilliamsM.2001. “The Application of Argumentation Theory to Translation Quality Assessment.” Meta: Translators’ Journal46 (2): 326–344. doi:10.7202/004605ar.Search in Google Scholar

AppendicesAppendix 1. The ATA framework and the LBI bandscale

The ATA framework for error marking

| One | Two | Four | Eight | Sixteen | Code | Reason | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation/strategic/transfer errors: Negative impact on understanding/use of target text | |||||||

| MT | - Mistranslation into target language | ||||||

| MU | - Misunderstanding of the source text | ||||||

| A | - Addition | ||||||

| O | - Omission | ||||||

| T | - Terminology, word choice | ||||||

| R | - Register | ||||||

| F | - Faithfulness | ||||||

| L | - Literalness | ||||||

| FA | - Faux ami (false friend) | ||||||

| COH | - Cohesion | ||||||

| AMB | - Ambiguity | ||||||

| ST | - Style | ||||||

| IND | - Indecision, gave more than one option | ||||||

| INC | - Inconsistency | ||||||

| CLS | - Failure to use items mentioned in class | ||||||

| WO | - Word order | ||||||

| Mechanical errors: Negative impact on overall quality of target text. | |||||||

| G | Grammar | ||||||

| SYN | - Syntax (phrase/clause/sentence structure) | ||||||

| P | - Punctuation | ||||||

| SP | Spelling | ||||||

| D | - Diacritics | ||||||

| C | - Capitalization | ||||||

| WF | - Word form (part of speech) | ||||||

| U | - Usage | ||||||

| Total error points: | |||||||

| Quality points: | Explanation: | ||||||

| 0 | |||||||

| Combined score: | 0 | ||||||

Assessment bandscale for PP LBI UI translator trainings

| Indonesian | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Pemahaman TSu dan penulisan TSa baik sekali. Sesekali secara kreatif mampu menemukan padanan yang sangat sesuai. | The source text (ST) understanding and the target text (TT) writing are excellent. Sometimes the student can creatively discover very suitable equivalents. | A = 4 A- = 3.5 |

| B | Pemahaman TSu baik, namun adakalanya terjadi kesalahpahaman TSu, terutama jika menerjemahkan bagian teks yang sulit. Penulisan dalam BSa umumnya baik, tidak banyak membuat kesalahan ejaan dan/atau tanda baca. | The ST understanding is good, but occasionally there is ST misunderstanding, especially when translating a difficult part of the text. The writing in the target language (TL) is generally good, not making many errors in spelling and/or punctuation marks. | B+ = 3.2 B = 3 B- = 2.8 |

| C | Pemahaman TSu cukup baik jika tingkat kesulitan teks tidak tinggi. Namun jika teks memiliki banyak ungkapan idiomatis atau terminologi khusus, peserta sering tidak mampu memahami teks dengan baik. Dalam hal penulisan dalam Bsa, peserta seringkali membuat kesalahan yang terkait dengan pilihan kata, kolokasi, ejaan dan tanda baca. | The ST understanding is quite good if the text difficulty level is not high. However, if the text has a large number of idiomatic expressions or special terminology, the student will often be unable to understand the text well. In terms of the TL writing, the student often makes mistakes related to choices of words, collocation, spelling, and punctuation marks. | C+ = 2.5 C = 2 C- = 1.5 |

| D | Pemahaman TSu perlu ditingkatkan lagi. Banyak kesalahan pengungkapan pesan ke dalam Bsa yang menyebabkan salah pengertian. | The ST understanding needs to be improved further. Many errors in the message transfer into the TL causing misunderstanding. | D = 1 |

Appendix 2. The source texts for pilot and formal projects

Pilot project source text

Indonesian Source Text: (Teks Sumber Berbahasa Indonesia)

Tembus Rekor Lagi, Pengangguran di 17 Negara Pengguna Euro Capai 19,38 Juta

Wahyu Daniel – detikfinance

Sabtu, 01/06/2013 10:36 WIB

London – Jumlah pengangguran di 17 negara Eropa pengguna mata uang euro kembali menembus rekor. Pada April 2013, persentase pengangguran di 17 negara tersebut mencapai 12,2%, naik dari bulan sebelumnya 10%.

Dikutip dari BBC, Sabtu (1/6/2013), ada tambahan pengangguran sebanyak 95 ribu orang di April 2013. Sehingga total pengangguran di 17 negara Eropa tersebut mencapai 19,38 juta orang.

Angka pengangguran tertinggi terjadi di Yunani dan Spanyol yang persentasenya 25%. Sedangkan angka pengangguran terendah adalah di Austria sebesar 4,9%.

Kantor Komisi Statistik Eropa yaitu Eurostat mengatakan, angka pengangguran di Jerman adalah 5,4%, sementara di Luxemburg adalah 5,6%. Angka pengangguran di Yunani adalah 27%, di Spanyol 26,8%, dan Portugal 17,8%.

Sementara angka pengangguran di Prancis selaku ekonomi dengan skala terbesar di Eropa, tingkat pengangguran menembus rekor di April. “Kami tidak melihat adanya kestabilan pengangguran sebelum pertengah 2014,” ujar seorang Ekonom Frederik Ducrozet.

Pengangguran remaja juga terus meningkat. Jumlah pengangguran berusia di bawah 25 tahun pada April 2013 berjumlah 3,6 juta orang, atau persentasenya 24,4%.

Formal project source text

Indonesian Source Text: (Teks Sumber Berbahasa Indonesia)

Paragraph 1:

Berita tentang mahalnya biaya sekolah. Pembaca yang menjadi peserta FGD berpendapat bahwa biaya RSBI sebenarnya tidak semahal sekolah swasta. Namun demikian, biaya yang tidak seragam antar sekolah dan ditetapkan oleh masing-masing sekolah ini yang kemudian membuka peluang bagi sekolah untuk menentukan harga semaunya. Sebagian peserta FGD mengatakan bahwa isi berita tentang mahalnya biaya dinyatakan memberikan referensi yang baik sehingga mereka mencari tahu dan membandingkan antar sekolah RSBI. Ketidak seragaman biaya menurut mereka tidak baik. Seharusnya pemerintah membuat keputusan tentang penyeragaman biaya sesuai dengan taraf hidup masyarakat di mana RSBI tersebut berada. Terhadap isi berita mengenai mahalnya biaya memunculkan kesenjangan dan menutup peluang bagi keluarga kurang mampu untuk menyekolahkan anaknya di RSBI ternyata memunculkan pro dan kontra. Sebagian setuju dengan isi berita tersebut dengan mengatakan bahwa tugas pemerintah adalah menyediakan pendidikan yang baik bagi masyarakat secara merata, tidak justru membuat kesenjangan dalam perolehan pedidikan. Sementara itu, pembaca yang tidak setuju menyatakan bahwa mereka keluarga kurang mampu dan anaknya bersekolah di RSBI. Terdapat juga siswa peserta FGD yang mengatakan berita tersebut terlalu mengeneralisasikan, karena dia yang berasal dari keluarga sederhana dan dapat bersekolah di RSBI.

Paragraph 2:

Berita tentang penggunaan bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa pengantar. Pembaca berita menyikapi hal ini dengan cukup bijak. Artinya, sebenarnya kebijakan pemerintah dinilai benar bahwa hanya sebagian dari mata pelajaran yang menggunakan bahasa pengantar bahasa Inggris. Namun demikian, sekolah yang justru dianggap memaksakan diri menggunakan bahasa pengantar bahasa Inggris untuk semua mata pelajaran. Selain gurunya tidak semua mampu dan siap, demikian pula siswanya yang belum merata kemampuan bahasa Inggrisnya. Meski demikian, sebagian besar peserta mengatakan setuju bahwa sebaiknya semua mata pelajaran diberikan dalam bahasa Indonesia dan penguatan bahasa Inggris diberikan pada mata pelajaran bahasa Inggris itu sendiri dengan ditambah berbagai aktivitas penunjang. Penggunaan bahasa Inggris dinilai akan kontraproduktif dengan penanaman nilai-nilai keindonesiaan yang seharusnya dapat berakar kuat dalam diri siswa, dan menjadi nilai keutamaan yang unggul dalam persaingan global sumber daya manusia nantinya.

Appendix 3. Consent form

Informed consent to participate in a research study

Study Title:

COMPARING TWO TRANSLATION ASSESSMENT MODELS: CORRELATING STUDENT REVISIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Principal Investigator: Dr. Sue Ellen Wright

Co-Investigator: Haru Deliana Dewi, M.Hum.

You are being invited to participate in a research study. This consent form will provide you with information on the research project, what you will need to do, and the associated risks and benefits of the research. Your participation is entirely voluntary. Please, read this form carefully. It is important that you ask questions and fully understand the research in order to make an informed decision. You will receive a copy of this document to take with you.

Purpose: This study aims to discover the effectiveness of two translation assessment models and to correlate student perspectives on assessment with their translation results.

Procedure: You will be presented with a short source text (2 paragraphs, each consisting of around 150 to 160 words) and be requested to translate them into English at home. You will be expected to work individually for three (3) hours and can use any resources available. After you have finished, please send the results to hdewi@kent.edu. Two weeks later, you will receive the assessment and feedback on your work. One paragraph will be assessed using one model of assessment, and the other paragraph will be assessed using the other model of assessment. Next, you will be requested to revise your first versions based on this assessment and feedback. You will have a week to do the revision. Please also send the revisions to hdewi@kent.edu. Then you will be asked to fill in a simple short survey to report your perspective on these two models of assessment.

Benefits: The potential benefits of participating in this study include having your translation assessed and receiving feedback to help improve your translation skills. Once you have completed your participation, you will be entitled to receive a token of appreciation, such as a keychain or something similar, and a certificate of participation directly from Kent State University after the research is concluded. You will also be provided with a short report describing the results of this research, which may provide insights into your own understanding of translation assessment in the future.

Risks and Discomforts: There are no anticipated risks beyond those encountered in everyday life.

Privacy and Confidentiality: No identifying information will be collected. Your signed consent form will be kept separate from your study data, and responses/results will not be linked to you.

Voluntary Participation: Taking part in this research study is entirely voluntary. You may choose not to participate or you may discontinue your participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which you are otherwise entitled. You will be informed of any new, relevant information that may affect your health, welfare, or willingness to continue your study participation.

Contact Information: If you have any questions or concerns about this research, you may contact Haru Deliana Dewi at hdewi@kent.edu. This project has been approved by the Kent State University Institutional Review Board. If you have any questions about your rights as a research participant or complaints about the research, you may call the IRB at +1 330–672 1797 or kmccrea1@kent.edu.

(The accompanying Indonesian form is a true and fair equivalent of this original English form. Kent State University requires that all materials presented to subjects be translated into their native language. See the third and fourth pages of the Indonesian version of this document.)

I have read this consent form and have had the opportunity to have my questions answered to my satisfaction. I voluntarily agree to participate in this study. I understand that a copy of this consent will be provided to me for future reference.

(Saya telah membaca formulir persetujuan tertulis ini dan telah mempunyai kesempatan bagi pertanyaan saya terjawab secara memuaskan. Saya secara sukarela setuju untuk berpartisipasi dalam penelitian ini. Saya mengerti bahwa salinan persetujuan tertulis ini akan disediakan bagi saya untuk rujukan di masa depan.)

______________________________________ ______________________________________

Participant SignatureDate

(Tanda Tangan Peserta)(Tanggal)

© 2018 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Article

- Issues and challenges of teaching communicative English in professional institutions: the case of northern India

- Emerging second language writing identity and complex dynamic writing

- College English teaching in China: opportunities, challenges and directions in the context of educational internationalization

- Translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English translation

Articles in the same Issue

- Article

- Issues and challenges of teaching communicative English in professional institutions: the case of northern India

- Emerging second language writing identity and complex dynamic writing

- College English teaching in China: opportunities, challenges and directions in the context of educational internationalization

- Translation and language errors in the Indonesian–English translation