Risk factors of long-term postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy in a solitary kidney

-

Jie Zhu

Abstract

The effect of warm ischemia time (WIT) on longterm renal function after partial nephrectomy remains controversial. In this retrospectively cohort study, 75 solitary kidney patients were included and the effects of warm ischemia time, preoperative renal function and resected normal parenchyma volume on long-term renal function were evaluated. Multivariable analysis showed that the preoperative renal function baseline was significantly associated with renal function 12 months postoperation (P=0.01), adjusting for age and comorbidities factors. Meanwhile, perioperative acute renal failure (ARF) events significantly affected postoperative renal function at postoperative time points of 12 months (P=0.001) and 60 months (P=0.03), as well as renal function change at postoperative 12 months (P<0.01). Warm ischemia time and resected normal parenchyma volume were not risk factors for long-term postoperative renal function, while the latter was significantly associated with renal function change (P=0.03 at 12 months, P<0.01 at 36 and 60 months).

In conclusion, the quality of preoperative kidney primarily determines long-term postoperative renal function, while the quantity of preserved functional parenchyma volume was the main determinant for long-term kidney recovery. ARF was an independent risk factor while WIT was indirectly associated with postoperative renal function by causing perioperative ARF.

1 Introduction

Over the last 2 decades, an increasing number of observational studies have indicated that partial nephrectomy (PN) was associated with elevated overall survival (OS) as well as better preservation of renal function, without compromising oncologic outcome, when compared with radical nephrectomy (RN) in treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [1,2,3,4]. PN has thus been accepted and applied by more and more urologists as a gold standard treatment for localized renal tumors.

The effect of warm ischemia time (WIT) on postoperative renal function remains controversial. Patil et al. indicated that ischemia was the most important and only surgically modifiable risk factor influencing the postoperative renal function after PN [5]. Similarly, Thompson et al. validated long WIT (>25 min) as a risk factor for long-term renal function after PN [6]. Yet Lane et al. considered baseline renal function and percentage of kidney preserved, rather than WIT, as key determinants of short and long-term renal function after PN [7].

To provide further evidence for this controversial topic, records of 75 solitary kidney patients were retrospectively studied, and the effect of warm ischemia time, preoperative renal function and resected normal parenchyma volume on long-term renal function were evaluated in this study.

2 Patients and methods

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Clinical center of the University Heidelberg. All patients signed an informed consent to participate in this cohort study. The clinical data of 75 solitary kidney patients undergoing 83 procedures of partial nephrectomy (6 patients with 2 PNs and 1 patient underwent 3 times PN because of cancer recurrence) at the Department of Urology, Clinical center of University Heidelberg from 08/1984 to 07/2011 were retrospectively studied. All patients with a solitary kidney who underwent partial nephrectomy were included, while the following patients were excluded to eliminate any bias: (1) patients with cold ischemia from PN approach; (2) patients with solitary kidney who underwent laparoscopic PN or robot-assisted laparoscopic PN; (3) patients with RCC over T2 stage; (4) patients with a follow-up time of postoperative renal function less than one year. Patients with multiple PNs were analyzed only once after the last surgery. The clinical features and grouping of included patients are detailed in Table 1.

Clinical feature and grouping.

| Feature (valid number of cases) [unit] Grouping | Value (%) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Patients Number | 75 | |

| PN surgery Number | 83 | |

| Mean age at surgery [yrs] | 62.58 ± 8.35 | 33-77 |

| Mean preoperative eGFR (n=83) [mL/min per 1.73m2] | 57.41 ± 13.01 | 23.66-87.72 |

| CKD II | 40 (48.19) | 60.47-87.72 |

| CKD III | 42 (50.60) | 32.25-59.31 |

| CKD IV | 1 (1.20) | 23.66 |

| Mean WIT (n=79) [min] | 18.04 ± 14.00 | 0-65 |

| WIT = 0 | 19 (24.05) | 0 |

| 0 < WIT < 20 | 22 (27.85) | 8-19 |

| 20 <= WIT < 30 | 24 (30.38) | 20-29 |

| WIT >= 30 | 14 (17.72) | 30-65 |

| Cases with ARF in perioperation (n=83) | ||

| with | 17 (20.48) | |

| without | 66 (79.52) | |

| Mean Number of tumor (n=72) | 1.36 ± 0.88 | 1-5 |

| single tumor | 58 (80.56) | |

| multiple tumors | 14 (19.44) | |

| Mean maximum diameter of tumor (n=72) [cm] | 3.38 ± 1.99 | 1-12 |

| Mean volume of resected normal parenchyma (n=72) [cm3][*] | 18.79 ± 40.37 | 0-299 |

| V < 1.38 | 18 (25.00) | |

| 1.38 <= V < 4.44 | 18 (25.00) | |

| 4.44 <= V < 22.13 | 18 (25.00) | |

| V >= 22.13 | 18 (25.00) | |

| Comorbidities (n=76)[#] | ||

| Hypertension | 41 (53.95) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (21.05) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 10 (13.16) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (6.58) | |

| Mean follow-up time (n=83) [months] | 69.39 ± 51.44 | 12-247 |

| Number of new-onset CKD IV cases | 15 (18.07) |

PN: partial nephrectomy; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD: chronic kidney disease; WIT: warm ischemia time; ARF: acute renal failure

In this study, we used the CKD-EPI (chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration) equation to calculating glomerular filtration rate (GFR), including four variables: serum creatinine, age, race, and gender (http://www.qxmd.com/renal/Calculate-CKD-EPI-GFR.php). In middle-aged and elderly population, the CKD-EPI equation is superior to the modification of diet in renal disease formula, especially when actual GFR is greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [8]. Measurement of the resected volume of normal kidney was used to indicate the residual kidney volume, as measurements of the preserved kidney volume were inaccurate. The formula of ellipsoid volume V = 4/3 Πabc (a, b and c are the largest radius of ellipsoid) was employed to calculate the volume of tumor and the resected mass, as the kidney tumor and resect mass were ellipsoid-shaped. Therefore, the volume of resected normal kidney is determined by subtracting the volume of the total resected mass with the volume of the tumor (Vnormal = Vresected –Vtumor). All data were collected from the postoperative pathology report.

Two independent parameters for evaluation of postoperative renal function were implemented :the value of postoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and the rate of post- vs. pre- operative renal function. The value of postoperative eGFR intuitively reflects the lever of renal function, which inevitably is influenced by preoperative renal function. The difference between post- and pre- eGFRs demonstrate the renal function change after PN and adequately exposes the risk factors of recovery capacity of postoperative renal function.

In this study, a mixed effect model was employed to analyze both univariate and multivariate effects among different WIT subgroups on renal function, as well as on the change rate of renal function (the postoperative eGFR/ the preoperative eGFR) at 1, 3 and 5 years after PN. The mixed effect model is a statistical model widely used in biomedical and health statistics research. It is particularly useful in settings where repeated measurements are made on the same statistical units (longitudinal study, such as renal function) and dealing with missing values. In addition, the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to analyze curve fit and create a predictive equation for postoperative eGFR.

All statistical tests were 2-tailed, with p < 0.05 being considered significant. Correlations between the outcomes and variables were expressed as HR with 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago).

Informed consent

Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Ethical approval

The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

3 Results

A total of 75 solitary kidney patients, who underwent 83 PN surgeries, were enrolled in this cohort study. The clinical features of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Among them, 6 patients underwent two PN and 1 patient underwent 3 PN due to the recurrence of cancer. The median age at surgery was 62.58 yrs. Preoperative GFR, with a mean value of 57.41 ml/min per 1.73 m2, was classified into 3 groups according to the chronic kidney disease staging criteria. The WIT were classified into 4 groups: 0; 0 < WIT < 20; 20 ≤ WIT < 30; WIT ≥ 30, with a mean value of 18.04 min. The postoperative complication with highest impact was perioperative acute renal failure (ARF, eGFR < 15 mL/min per 1.73m2). The incidence of postoperative ARF complication were 20.48% (17 cases), and these patients all recovered after conservative treatment or temporary dialysis within 3 months.

The average follow-up time was 69.39 months (ranging from 12 months to 247 months). During follow-up, we collected 72 pathology reports from the 83 PN surgeries. Among them, the average number of tumors was 1.36 (the maximum was 5). The incidence of patients with a single tumor accounted for 80.56% (58 cases), while patients with multiple tumors accounted for 19.44% (14 cases). The average tumor diameter was 3.38 cm, with the maximum tumor diameter of 12 cm. According to the quartile, patients were divided into four groups considering the resected normal renal tissue volume, with an average volume of 18.79 cm3.

The main comorbidities during follow-up were hypertension (41 cases, 53.95%), diabetes (16 cases, 21.05%), cardiovascular diseases (10 cases, 13.16%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (5 cases, 6.58%). Fifteen new cases (18.07%) of CKD stage IV nephropathy (15 < eGFR <= 29 mL/min per 1.73m2) were observed after operation, with 6, 4, 2, and 3 cases occurring at 12, 36, 60, 120 months, respectively.

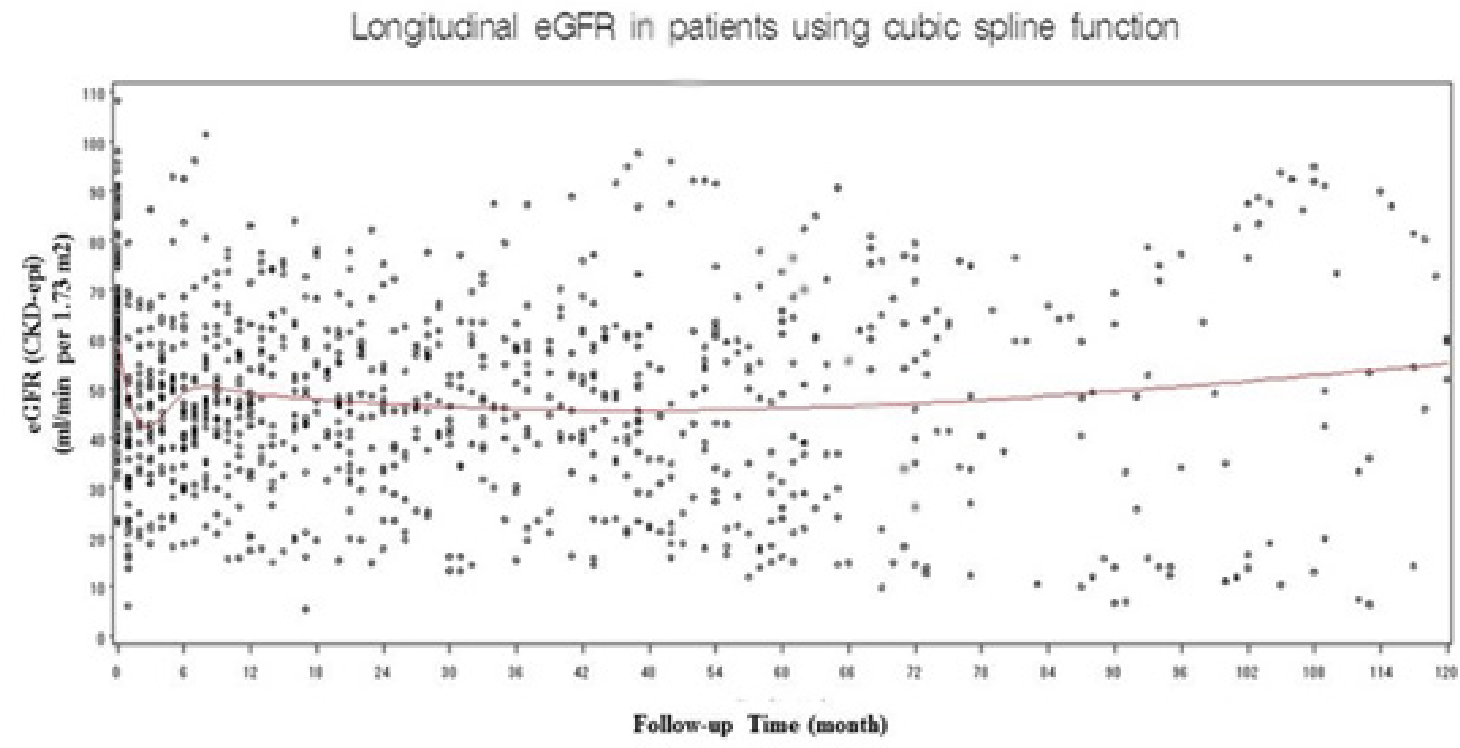

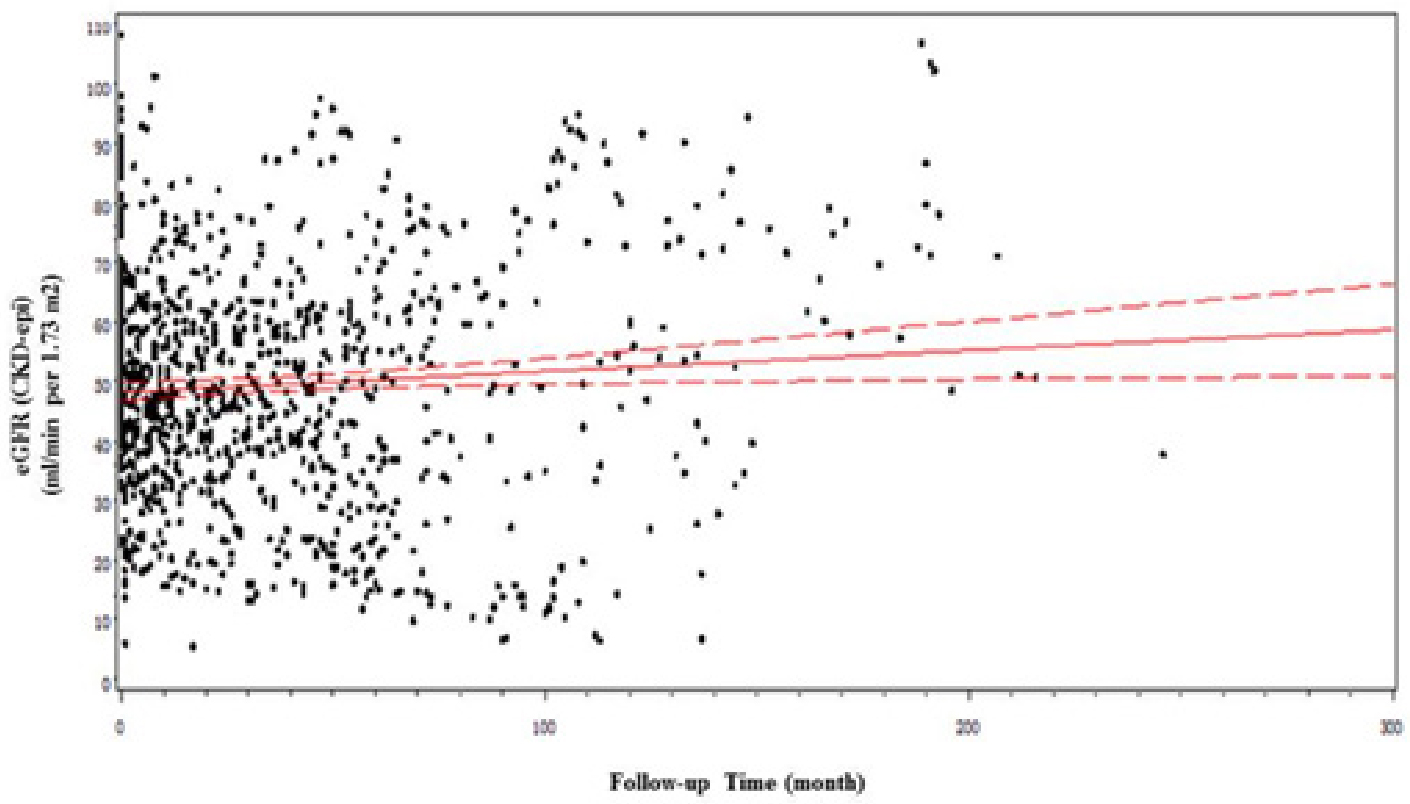

The scatterplot of postoperative eGFR and average renal function is shown in Figure 1. The postoperative renal function level dropped rapidly at first, reaching the lowest point about 1 month after surgery, and then rose gradually to the peak at around 6 months. The curve became stable 12 months after operation, following a slow decline. In addition, the scatterplot of postoperative eGFR and linear regression is shown in Figure 2. The predictive equation for postoperative renal function is: eGFR = 48.28 + 0.03×months, which indicates that the recovery course of PN postoperative renal function is slow yet continuous.

Scatter plot and longitudinal GFR overtime in patients using cubic spline function

The red curve denotes the fitted curve showing the trend of postoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Scatter plot and linear regression of postoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) dependent upon time

The red full line shows a linear regression, and the dotted lines indicate the 95% CI.

The average postoperative renal functions were 48.9, 48.8, 52.8 and 52.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at 12, 36, 60 and 120 months after surgery, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify factors associated with the long-term (> = 1 year) renal function (eGFR), and the results are detailed in Table 2. Compared with the preoperative baseline renal function, a significant difference (p = 0.01) was found at 12 months after surgery, while no differences were found at 36 months and 60 months after surgery. In addition, perioperative ARF events had a significant and continual effect on postoperative renal function (p = 0.001, after 12 months; p = 0.03, after 60 months). However, WIT and resected normal renal tissue volume were not significantly associated with longterm renal function.

Univariate and multivariable analyses of renal function level (value of postoperative eGFR)

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 m | 36 m | 60 m | 12 m | 36 m | 60 m | |

| WIT | 0.2 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 0.98 |

| Preoperative eGFR | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.69 |

| ARF | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Tumor number | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.049 | 0.8 | 0.51 | 0.049 |

| Resected renal parenchyma volume | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.22 |

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; WIT: warm ischemia time; ARF: acute renal failure

Compared with the preoperative baseline level of renal function, the rate of renal function change were 85.8% (36.6-162.1%), 83.7% (27.0-166.8%), 166.8% (34.8 -148.8%), and 148.8% (17.2 -164.1%) at 12, 36, 60 and 120 months after surgery, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed considering the long-term (> = 1 year) renal function change (postoperative eGFR/preoperative eGFR), and the results are presented in Table 3. We found that WIT (p = 0.049) and the preoperative baseline renal function (p = 0.049) had a slight, but significant, effect on the postoperative renal function change 12 months after surgery, whereas perioperative ARF events were significantly associated with the change of postoperative renal function at 12 months after surgery (p < 0.01). Yet, there was no significant difference between postoperative renal function change and the above three factors (WIT, preoperative baseline renal function and perioperative ARF events) at 36 months and 60 months after surgery. In contrast, resected renal parenchyma volume was significantly associated with postoperative renal function change at time points throughout the follow-up (p = 0.03, after 12 months; p < 0.01, after 36 months; and p < 0.01, after 60 months).

Univariate and multivariable analyses of renal function recovery (postoperative eGFR/preoperative eGFR)

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 m | 36 m | 60 m | 12 m | 36 m | 60 m | |

| WIT | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.049 | 0.9 | 0.98 |

| Preoperative eGFR | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.049 | 0.81 | 0.68 |

| ARF | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.21 | 0.051 |

| Tumor number | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.049 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.06 |

| Resected renal parenchyma volume | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; WIT: warm ischemia time; ARF: acute renal failure

Furthermore, a chi-square test was performed to determine a cutoff of WIT by investigating its relationships with perioperative ARF event, in which WIT was grouped in 5-minutes intervals. As shown in Table 4, significant differences were observed between the 2 groups when the cutoff was set as 20, 25, 30 and 35 minutes, respectively. For example, the odds of developing ARF was 4.27 (95%CI, 1.24-14.72; p=0.02) for patients treated with >20 min (vs <=20) of warm ischemia. The ratio of patients with ARF overweighed those without ARF between a cutoff WIT of 25 min and 30 min.

Chi-square test for association between WIT and perioperative ARF event

| Groups | Number of with or without ARF(%) | X2 | OR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARF (n=16) | without ARF (n=63) | ||||

| WIT < 10 | 1 (6.25%) | 21 (33.33%) | 3.57 | 7.50 (0.93, 60.68) | 0.06 |

| WIT >= 10 | 15 (93.75%) | 42 (66.67%) | |||

| WIT < 15 | 3 (18.75%) | 29 (46.03%) | 3.60 | 3.70 (0.96, 14.25) | 0.06 |

| WIT >= 15 | 13 (81.25%) | 34 (53.97%) | |||

| WIT < 20 | 4 (25.00%) | 37 (58.73%) | 5.28 | 4.27 (1.24, 14.72) | 0.02 |

| WIT >= 20 | 12 (75.00%) | 26 (41.27%) | |||

| WIT < 25 | 7 (43.75%) | 49 (77.78%) | 4.59 | 3.50 (1.13, 11.01) | 0.03 |

| WIT >= 25 | 9 (56.25%) | 14 (22.22%) | |||

| WIT < 30 | 10 (62.50%) | 55 (87.30%) | 4.90 | 4.13 (1.18, 14.47) | 0.03 |

| WIT >= 30 | 6 (37.5%) | 8 (12.70%) | |||

| WIT < 35 | 11 (68.75%) | 58 (92.06%) | 5.44 | 5.27 (1.30, 21.32) | 0.02 |

| WIT >= 35 | 5 (31.25%) | 5 (7.94%) | |||

| WIT < 40 | 13 (81.25%) | 60 (95.24%) | 3.08 | 4.62 (0.84, 25.49) | 0.08 |

| WIT >= 40 | 3 (18.75%) | 3 (4.76%) | |||

WIT: warm ischemia time; ARF: acute renal failure

4 Discussion

The kidney is highly oxygen-depended [9]. During PN, the renal artery is temporarily blocked, a process of anoxia reperfusion, triggering a cascade amplifying kidney injury. Ischemic injury can induce the release of angiotensin II, eicosanoid, and various cytokines, leading to the contraction of small arteries and increased kidney cell anoxia, which then terminates the oxidative phosphorylation process, and cause cell swelling by allowing interstitial liquid to passively spread into cells. Furthermore, after removal of the block, inflammatory factors and radicals perfuse into cells with blood, leading to further damage and necrosis of the renal cells. Therefore, ischemia can lead to renal function disorder associated with renal cell injury, eGFR decline, and urine product change [10,11,12].

In PN, the recovery of postoperative renal function and the longest blocked time that the kidney can tolerate have been hot-topic issues in clinical research. Parekh et al. reported a prospective research study on postoperative renal function and pathological changes, which compared warm ischemia (27 cases, with a mean ischemia time of 32.3 min) with cold ischemia (13 cases, with a mean ischemia time of 48.0 min). The postoperative, perioperative blood and urine markers of renal function, as well as kidney pathological changes by biopsy were investigated. The results demonstrated that differential block methods and block time durations were not associated with acute renal function damage, and there were no significant correlations between block time and postoperative renal function. In addition, this study reported surprisingly that the human kidney can tolerate an ischemia time as long as 30 to 60 min [13]. However, all patients in the study had a normal, contralateral kidney. Therefore, the presence of renal functional from the contralateral kidney may be confused. Moreover, the deleterious impact of prolonged ischemia requires time to manifest, and significant histologic changes may not be immediately found after hilar clamping.

Simmons et al. suggested that a decrease of GFR in PN surgery may be influenced by 3 factors: functional volume loss, ischemia related acute kidney injury and mechanical trauma effects [14]. Collateral damage due to renorrhaphy volume loss occurs mainly as a result of resected normal parenchyma adjacent to the tumor margin. Ischemia-reperfusion injury is associated with ischemia duration and specific approaches (i.e. super-selected arterial, warm ischemia or cold ischemia). Potential mechanisms of trauma include disruption of osmotic gradients by localized edema, cytokine inhibitory effects and alteration of regional microvascular blood flow, which can be amplified and induced by ischemia. The recovery mechanism of the kidney is complex and not presently clear. The ischemia and trauma injury are reversed within weeks to months after PN [6,15].

In the present study, we found that preoperative CKD stage (preoperative renal function) was significantly associated with renal function (postoperative eGFR) at 12 months after PN (p=0.01), whereas the volume of resected normal parenchyma had no association with long-term postoperative renal function. However, when post-/pre-operative eGFR was set as the observed variable, we found that the resected volume of normal parenchyma was significantly associated with renal function change at all time points of follow-up (p=0.03 at 12 months; P<0.01 at 36 and 60 months), whereas preoperative CKD stage was only slightly associated with renal function change at 12 months (P=0.049). These results indicate that the quality of preoperative renal function and quantity of preserved kidney parenchyma are the primary determinants of postoperative long-term renal function. The quantity of kidney influences the recovery ability of renal function in the long-term, and preoperative quality of the kidney influences the level of long-term renal function.

Consistent with the study of Lane et al., we did not found a significant association between WIT and either renal function or renal function change in the longterm follow-up (>1y). Furthermore, we identified the perioperative ARF event as a new risk factor that can influence both renal function (p=0.001 at postoperative 12 months and p=0.03 at postoperative 60 months) and renal function change (p<0.001 at postoperative 12 months). Since prolonged ischemia can result in perioperative or postoperative ARF, we infer that, although WIT has no direct association with recovery capacity and renal function level, it can indirectly affect both by causing perioperative or postoperative ARF events in longterm postoperative time period. Furthermore we used a chi-square test to analyze the association between a perioperative ARF event and WIT, which was grouped every 5 minutes. Significant differences of ARF event incidence were found between the 2 groups when the cutoff was set as 20, 25, 30 and 35 minutes respectively (Table 4). From this result we suggest that a WIT< 20 min should be the goal, with 35 minutes as the upper limit, during PN surgery. The incidence of postoperative ARF complication we found were 20.48% (17 cases), which seems higher than those from other publications. But considering the relatively small sample size of our cohort study, it is consistent with the report from Thompson et al. [16], where postoperative acute renal failure occurred in 70 patients (19%) after partial nephrectomy out of 362 consecutive patients.

In recent guidelines, “long-term renal function” is not uniformly defined. The duration of long-term renal dysfunction after surgery ranged from 1 to 6 months [7,16,17]. As can be observed from the scatterplot of postoperative eGFR and average renal function fitting curve (Figure 1), the eGFR curve declined to the lowest point at 3 months, slowly reached the peak at 6 months, and slightly declined before becoming stable after 12 months post-surgery. These findings are consistent with the result of Rochelle study [18]. Therefore, we suggest that at least 12 months’ analysis of renal function should be required after renal surgery.

The current study had several limitations. Since the data were collected in a retrospective fashion and from a single institution, there were inherent biases. A long time span (from 1981-2013) affects oncological outcomes and renal function recovery because of differential patients selection, surgery techniques and perioperative treatments. Additionally, although disturbance from normal contralateral kidney was avoided because all patients included had a solitary kidney, the imperative indications for PN translated into sophisticated procedures because the selection to use PN was forced by the oncology but not by technical feasibility of surgery as compared to elective indication. Furthermore, in the present study, we use the resected volume of normal parenchyma as an indication of preserved kidney volume. However, the measurement of resected normal parenchyma, which is more accurate and objective than Thompson’s method of estimating by the primary surgeon after PN, is still not accurate enough. Therefore, a prospective multicenter clinical trial using Medical Interaction Toolkit (Version 2011; DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany, http://www.MITK.org/Diffusion) to measure the preserved volume of kidney is of demand in the future [19].

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, a key determinant for long-term recovery of kidney capacity is the quantity of preserved functional parenchyma volume, which results in a slow but continuous recovery course. The quality of preoperative kidney determines the level of postoperative kidney function. Perioperative ARF event, as a third determinant, can influence not only recovery capacity but also renal function level over the long-term after PN surgery. Although WIT had no direct association with recovery capacity and renal function level, it can indirectly affect both recovery capacity and renal function level in the long-term by causing perioperative and postoperative ARF events. The WIT is preferable for less than 20 minutes, with an upper limit for 35 minutes during the PN surgery.

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Xylinas E., Rink M., Margulis V., Faison T., Comploj E., Novara G., et al., Prediction of true nodal status in patients with pathological lymph node negative upper tract urothelial carcinoma at radical nephroureterectomy, J. Urol., 2013, 189, 468-47310.1016/j.juro.2012.09.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Tan H.J., Norton E.C., Ye Z., Hafez K.S., Gore J.L. and Miller D.C., Long-term survival following partial vs radical nephrectomy among older patients with early-stage kidney cancer, JAMA, 2012, 307, 1629-163510.1001/jama.2012.475Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Thompson R.H., Siddiqui S., Lohse C.M., Leibovich B.C., Russo P. and Blute M.L., Partial versus radical nephrectomy for 4 to 7 cm renal cortical tumors, J. Urol., 2009, 182, 2601-260610.1016/j.juro.2009.08.087Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Clark M.A., Shikanov S., Raman J.D., Smith B., Kaag M., Russo P., et al., Chronic kidney disease before and after partial nephrectomy, J. Urol., 2011, 185, 43-4810.1016/j.juro.2010.09.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Patil M.B., Lee D.J. and Gill I.S., Eliminating global renal ischemia during partial nephrectomy: an anatomical approach, Curr. Opin. Urol., 2012, 22, 83-8710.1097/MOU.0b013e32834ef70cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Simmons M.N., Fergany A.F. and Campbell S.C., Effect of parenchymal volume preservation on kidney function after partial nephrectomy, J. Urol., 2011, 186, 405-41010.1016/j.juro.2011.03.154Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Lane B.R., Russo P., Uzzo R.G., Hernandez A.V., Boorjian S.A., Thompson R.H., et al., Comparison of cold and warm ischemia during partial nephrectomy in 660 solitary kidneys reveals predominant role of nonmodifiable factors in determining ultimate renal function, J. Urol., 2011, 185, 421-42710.1016/j.juro.2010.09.131Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., Greene T., Zhang Y.L., Beck G.J., Froissart M., et al., Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, Am. J. Kidney Dis., 2010, 56, 486-49510.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Silva P., Energy and fuel substrate metabolism in the kidney, Semin. Nephrol., 1990, 10, 432-444Search in Google Scholar

[10] Derweesh I.H. and Novick A.C., Mechanisms of renal ischaemic injury and their clinical impact, BJU Int., 2005, 95, 948-95010.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05444.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Sheridan A.M. and Bonventre J.V., Cell biology and molecular mechanisms of injury in ischemic acute renal failure, Curr.Opin. Nephrol Hypertens, 2000, 9, 427-43410.1097/00041552-200007000-00015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Simmons M.N., Schreiber M.J. and Gill I.S., Surgical renal ischemia: a contemporary overview, J. Urol., 2008, 180, 19-3010.1016/j.juro.2008.03.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Parekh D.J., Weinberg J.M., Ercole B., Torkko K.C., Hilton W., Bennett M., et al., Tolerance of the human kidney to isolated controlled ischemia, J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., 2013, 24, 506-51710.1681/ASN.2012080786Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Simmons M.N., Hillyer S.P., Lee B.H., Fergany A.F., Kaouk J. and Campbell S.C., Functional recovery after partial nephrectomy: effects of volume loss and ischemic injury, J. Urol., 2012, 187, 1667-167310.1016/j.juro.2011.12.068Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Song C., Bang J.K., Park H.K. and Ahn H., Factors influencing renal function reduction after partial nephrectomy, J. Urol., 2009, 181, 48-53; discussion 53-4410.1016/j.juro.2008.09.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Thompson R.H., Lane B.R., Lohse C.M., Leibovich B.C., Fergany A., Frank I., et al., Renal function after partial nephrectomy: effect of warm ischemia relative to quantity and quality of preserved kidney, Urology, 2012, 79, 356-36010.1016/j.urology.2011.10.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Wszolek M.F., Kenney P.A., Lee Y. and Libertino J.A., Comparison of hilar clamping and non-hilar clamping partial nephrectomy for tumours involving a solitary kidney, BJU Int., 2011, 107, 1886-189210.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09713.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] La Rochelle J., Shuch B., Riggs S., Liang L.J., Saadat A., Kabbinavar F., et al., Functional and oncological outcomes of partial nephrectomy of solitary kidneys, J. Urol., 2009, 181, 2037-2042; discussion 204310.1016/j.juro.2009.01.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Kuru T.H., Zhu J., Popeneciu I.V., Rudhardt N.S., Hadaschik B.A., Teber D., et al., Volumetry may predict early renal function after nephron sparing surgery in solitary kidney patients, Springerplus, 2014, 3, 48810.1186/2193-1801-3-488Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2017 Jie Zhuet al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Field Performance and Genetic Fidelity of Micropropagated Plants of Coffea canephora (Pierre ex A. Froehner)

- Research Articles

- Foliage maturity of Quercus ilex affects the larval development of a Croatian coastal population of Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Erebidae)

- Research Articles

- Structural and functional impact of SNPs in P-selectin gene: A comprehensive in silico analysis

- Research Articles

- High embryogenic ability and regeneration from floral axis of Amorphophallus konjac (Araceae)

- Research Articles

- Terpene content of wine from the aromatic grape variety ‘Irsai Oliver’ (Vitis vinifera L.) depends on maceration time

- Research Articles

- Light and smell stimulus protocol reduced negative frontal EEG asymmetry and improved mood

- Research Articles

- Swailing affects seed germination of plants of European bio-and agricenosis in a different way

- Research Articles

- Survey analysis of soil physicochemical factors that influence the distribution of Cordyceps in the Xiahe Region of Gansu Province

- Research Articles

- Production of biogas: relationship between methanogenic and sulfate-reducing microorganisms

- Research Articles

- Pentraxin 3 and atherosclerosis among type 2 diabetic patients

- Research Articles

- Evaluation of ribosomal P0 peptide as a vaccine candidate against Argulus siamensis in Labeo rohita

- Research Articles

- Variation of autosomes and X chromosome STR in breast cancer and gynecological cancer tissues

- Research Articles

- Response of antioxidant enzymes to cadmium-induced cytotoxicity in rat cerebellar granule neurons

- Research Articles

- Cardiac hypertrophy and IGF-1 response to testosterone propionate treatment in trained male rats

- Research Articles

- BRAF-activated non-protein coding RNA (BANCR) advances the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via cell cycle

- Research Articles

- The influence of soil salinity on volatile organic compounds emission and photosynthetic parameters of Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties

- Research Articles

- Simple Protocol for immunoglobulin G Purification from Camel “Camelus dromedarius” Serum

- Research Articles

- Expression of psbA1 gene in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is influenced by CO2

- Research Articles

- Frequency of Thrombophilic Gene Mutations in Patients with Deep Vein Thrombosis and in Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

- Research Articles

- Evaluation of anticancer properties of a new α-methylene-δ-lactone DL-249 on two cancer cell lines

- Research Articles

- Impact of heated waters on water quality and macroinvertebrate community in the Narew River (Poland)

- Research Articles

- Effects of Some Additives on In Vitro True Digestibility of Wheat and Soybean Straw Pellets

- Research Articles

- RNAi-mediated gene silencing in Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Oliver) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

- Research Articles

- New pathway of icariin-induced MSC osteogenesis: transcriptional activation of TAZ/Runx2 by PI3K/Akt

- Research Articles

- Tudor-SN protein expression in colorectal cancer and its association with clinical characteristics

- Research Articles

- Proteomic and bioinformatics analysis of human saliva for the dental-risk assessment

- Research Articles

- Reverse transcriptase sequences from mulberry LTR retrotransposons: characterization analysis

- Research Articles

- Strain Stimulations with Different Intensities on Fibroblast Viability and Protein Expression

- Research Articles

- miR-539 mediates osteoblast mineralization by regulating Distal-less genes 2 in MC3T3-E1 cell line

- Research Articles

- Diversity of Intestinal Microbiota in Coilia ectenes from Lake Taihu, China

- Research Articles

- The production of arabitol by a novel plant yeast isolate Candida parapsilosis 27RL-4

- Research Articles

- Effectiveness of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on young plants of Vitis vinifera L.

- Research Articles

- Changes of photochemical efficiency and epidermal polyphenols content of Prosopis glandulosa and Prosopis juliflora leaves exposed to cadmium and copper

- Research Articles

- Ultraweak photon emission in strawberry fruit during ripening and aging is related to energy level

- Research Articles

- Molecular cloning, characterization and evolutionary analysis of leptin gene in Chinese giant salamander, Andrias davidianus

- Research Articles

- Longevity and stress resistance are affected by activation of TOR/Myc in progenitor cells of Drosophila gut

- Research Articles

- Curcumin attenuates oxidative stress in liver in Type 1 diabetic rats

- Research Articles

- Risk factors of long-term postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy in a solitary kidney

- Research Articles

- Developmental anomalies of the right hepatic lobe: systematic comparative analysis of radiological features

- Review articles

- Genetic Defects Underlie the Non-syndromic Autosomal Recessive Intellectual Disability (NS-ARID)

- Review articles

- Research Progress on Tissue Culture and Genetic Transformation of Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus)

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- MiR-107 inhibits proliferation of lung cancer cells through regulating TP53 regulated inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (TRIAP1)

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The functional role of exosome microRNAs in lung cancer

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The diagnostic value of serum microRNA-183 and TK1 as biomarkers for colorectal cancer diagnosis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Screening feature modules and pathways in glioma using EgoNet

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Isoliquiritigenin inhibits colorectal cancer cells HCT-116 growth by suppressing the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Association between Caveolin-1 expression and pathophysiological progression of femoral nerves in diabetic foot amputation patients

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Biomarkers in patients with myocardial fibrosis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Dysregulated pathways for off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Individualized identification of disturbed pathways in sickle cell disease

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The prognostic value of serum PCT, hs-CRP, and IL-6 in patients with sepsis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Sevoflurane-medicated the pathway of chemokine receptors bind chemokines in patients undergoing CABG

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The functional role of microRNAs in laryngeal carcinoma

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Revealing pathway cross-talk related to diabetes mellitus by Monte Carlo Cross-Validation analysis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Correlation between CDKAL1 rs10946398C>A single nucleotide polymorphism and type 2 diabetes mellitus susceptibility: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Effects of environmental variables on seedling distribution of rare and endangered Dacrydium pierrei

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Study on synthesis and properties of nanoparticles loaded with amaryllidaceous alkaloids

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Bacterial Infection Potato Tuber Soft Rot Disease Detection Based on Electronic Nose

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Effects of subsoiling on maize yield and water-use efficiency in a semiarid area

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Field Performance and Genetic Fidelity of Micropropagated Plants of Coffea canephora (Pierre ex A. Froehner)

- Research Articles

- Foliage maturity of Quercus ilex affects the larval development of a Croatian coastal population of Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Erebidae)

- Research Articles

- Structural and functional impact of SNPs in P-selectin gene: A comprehensive in silico analysis

- Research Articles

- High embryogenic ability and regeneration from floral axis of Amorphophallus konjac (Araceae)

- Research Articles

- Terpene content of wine from the aromatic grape variety ‘Irsai Oliver’ (Vitis vinifera L.) depends on maceration time

- Research Articles

- Light and smell stimulus protocol reduced negative frontal EEG asymmetry and improved mood

- Research Articles

- Swailing affects seed germination of plants of European bio-and agricenosis in a different way

- Research Articles

- Survey analysis of soil physicochemical factors that influence the distribution of Cordyceps in the Xiahe Region of Gansu Province

- Research Articles

- Production of biogas: relationship between methanogenic and sulfate-reducing microorganisms

- Research Articles

- Pentraxin 3 and atherosclerosis among type 2 diabetic patients

- Research Articles

- Evaluation of ribosomal P0 peptide as a vaccine candidate against Argulus siamensis in Labeo rohita

- Research Articles

- Variation of autosomes and X chromosome STR in breast cancer and gynecological cancer tissues

- Research Articles

- Response of antioxidant enzymes to cadmium-induced cytotoxicity in rat cerebellar granule neurons

- Research Articles

- Cardiac hypertrophy and IGF-1 response to testosterone propionate treatment in trained male rats

- Research Articles

- BRAF-activated non-protein coding RNA (BANCR) advances the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via cell cycle

- Research Articles

- The influence of soil salinity on volatile organic compounds emission and photosynthetic parameters of Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties

- Research Articles

- Simple Protocol for immunoglobulin G Purification from Camel “Camelus dromedarius” Serum

- Research Articles

- Expression of psbA1 gene in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is influenced by CO2

- Research Articles

- Frequency of Thrombophilic Gene Mutations in Patients with Deep Vein Thrombosis and in Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

- Research Articles

- Evaluation of anticancer properties of a new α-methylene-δ-lactone DL-249 on two cancer cell lines

- Research Articles

- Impact of heated waters on water quality and macroinvertebrate community in the Narew River (Poland)

- Research Articles

- Effects of Some Additives on In Vitro True Digestibility of Wheat and Soybean Straw Pellets

- Research Articles

- RNAi-mediated gene silencing in Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Oliver) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

- Research Articles

- New pathway of icariin-induced MSC osteogenesis: transcriptional activation of TAZ/Runx2 by PI3K/Akt

- Research Articles

- Tudor-SN protein expression in colorectal cancer and its association with clinical characteristics

- Research Articles

- Proteomic and bioinformatics analysis of human saliva for the dental-risk assessment

- Research Articles

- Reverse transcriptase sequences from mulberry LTR retrotransposons: characterization analysis

- Research Articles

- Strain Stimulations with Different Intensities on Fibroblast Viability and Protein Expression

- Research Articles

- miR-539 mediates osteoblast mineralization by regulating Distal-less genes 2 in MC3T3-E1 cell line

- Research Articles

- Diversity of Intestinal Microbiota in Coilia ectenes from Lake Taihu, China

- Research Articles

- The production of arabitol by a novel plant yeast isolate Candida parapsilosis 27RL-4

- Research Articles

- Effectiveness of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on young plants of Vitis vinifera L.

- Research Articles

- Changes of photochemical efficiency and epidermal polyphenols content of Prosopis glandulosa and Prosopis juliflora leaves exposed to cadmium and copper

- Research Articles

- Ultraweak photon emission in strawberry fruit during ripening and aging is related to energy level

- Research Articles

- Molecular cloning, characterization and evolutionary analysis of leptin gene in Chinese giant salamander, Andrias davidianus

- Research Articles

- Longevity and stress resistance are affected by activation of TOR/Myc in progenitor cells of Drosophila gut

- Research Articles

- Curcumin attenuates oxidative stress in liver in Type 1 diabetic rats

- Research Articles

- Risk factors of long-term postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy in a solitary kidney

- Research Articles

- Developmental anomalies of the right hepatic lobe: systematic comparative analysis of radiological features

- Review articles

- Genetic Defects Underlie the Non-syndromic Autosomal Recessive Intellectual Disability (NS-ARID)

- Review articles

- Research Progress on Tissue Culture and Genetic Transformation of Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus)

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- MiR-107 inhibits proliferation of lung cancer cells through regulating TP53 regulated inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (TRIAP1)

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The functional role of exosome microRNAs in lung cancer

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The diagnostic value of serum microRNA-183 and TK1 as biomarkers for colorectal cancer diagnosis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Screening feature modules and pathways in glioma using EgoNet

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Isoliquiritigenin inhibits colorectal cancer cells HCT-116 growth by suppressing the PI3K/AKT pathway

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Association between Caveolin-1 expression and pathophysiological progression of femoral nerves in diabetic foot amputation patients

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Biomarkers in patients with myocardial fibrosis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Dysregulated pathways for off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Individualized identification of disturbed pathways in sickle cell disease

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The prognostic value of serum PCT, hs-CRP, and IL-6 in patients with sepsis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Sevoflurane-medicated the pathway of chemokine receptors bind chemokines in patients undergoing CABG

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- The functional role of microRNAs in laryngeal carcinoma

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Revealing pathway cross-talk related to diabetes mellitus by Monte Carlo Cross-Validation analysis

- Topical Issue On Precision Medicine

- Correlation between CDKAL1 rs10946398C>A single nucleotide polymorphism and type 2 diabetes mellitus susceptibility: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Effects of environmental variables on seedling distribution of rare and endangered Dacrydium pierrei

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Study on synthesis and properties of nanoparticles loaded with amaryllidaceous alkaloids

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Bacterial Infection Potato Tuber Soft Rot Disease Detection Based on Electronic Nose

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Effects of subsoiling on maize yield and water-use efficiency in a semiarid area