Abstract

This study aims to investigate the chemical composition and assess the anti-cancer potential of Matricaria recutita L. essential oil against various cancer cell lines. The chemical profile of the essential oil was determined through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), identifying major constituents such as (Z)-β-farnesene, α-bisabolol oxides, and chamazulene. The anti-cancer activity was evaluated using in vitro cytotoxicity assays (MTT assay) on human lung adenocarcinoma (A549), human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231), and mouse fibroblast (L929) cell lines. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and data were analyzed using ANOVA to determine statistical significance. The main constituents of the essential oil included (Z)-β-farnesene (33.90 %), α-bisabolol oxide B (11.60 %), and others. The oil demonstrated considerable cytotoxic effects across all tested cancer cell lines, with IC50 values indicating strong anti-proliferative activity, particularly at higher concentrations and longer exposure times. The results showed dose-dependent reductions in cell viability, with significant decreases in cell proliferation observed especially at concentrations over 7.81 μg/mL. These findings support its potential as a natural, complementary agent in cancer therapy, warranting further in vivo studies for clinical application.

1 Introduction

Matricaria recutita L. (syn. Matricaria chamomilla L., Chamomilla recutita L. Rauschert) commonly known as true chamomile or German chamomile, is indigenous to Central and Southern European regions but has spread to other continents like America, Africa, and Australia. This aromatic plant yields an essential oil renowned for its distinctive properties [1], [2], [3]. German chamomile is a medicinal herb renowned for its therapeutic benefits, particularly in the form of essential oil. Extracted from the flowers of this plant, chamomile essential oil possesses a diverse array of pharmacological properties, protective activities, and therapeutic uses that have been recognized and utilized across various medical and wellness practices.

The essential oil (MEO), a dense blue liquid with a potent aroma and a bitter-aromatic taste, undergoes a fascinating transformation in colder temperatures, solidifying into a mass reminiscent of a basement. The blue hue of the oil owes itself to chamazulene, a compound derived from the dehydrogenation of proazulenes present in the raw material. Chamazulene typically constitutes 1 %–18 % of the oil, occasionally reaching up to 24 % [1], 2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10].

Scientific research has validated the biological efficacy of chamomile essential oil, showcasing its antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory characteristics [4], 5], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. As a result, it finds widespread application in medicine, cosmetics, and the food industry [1], [2], [3], [9], 14].

Medicinal plants have long been utilized for treating various types of cancer complications, and their use has gradually increased due to the side effects associated with chemical medications [19], 20]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 65 % of the global population relies on traditional medicine for primary healthcare [21], 22].

The aim of the present study is to determine chemical composition and anticancer activity of Matricaria recutita L. using different cancer cell lines.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The chamomile essential oil was provided by an essential oil manufacturer located in Southern Bulgaria. The oil is a dense blue liquid with a characteristic chamomile smell.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 GC/MS analysis

A gas chromatography (GC) analysis of the chamomile oil was performed using an Agilent 7890A (Santa Clara, CA 95051, USA) gas chromatograph, HP-5 column MS (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm), temperature: 35 °C/3 min, 5 °C/min to 250 °C for 3 min, 49 min in total, helium as carrier gas, 1 mL/min constant speed, 30:1 split ratio. A gas chromatography–mass spectrometric (GC/MS) analysis was carried out on an Agilent 5975C mass spectrometer, with helium as a carrier gas, column, and temperature the same as in the GC analysis. The identification of the chemical compounds was made by comparison to their relative retention time and library data [23]. Components were listed according to their retention (Kovat’s) indices, calculated using a standard calibration mixture of C8–C40 n-alkanes in n-hexane. Compound concentration was computed as a percentage of the total ion current (TIC).

2.2.2 Cytotoxicity assay, cell lines and culture conditions

2.2.2.1 Cell lines

Human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (A549), human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), mouse fibroblast cells (L929), and human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231) were used to evaluate cytotoxic activity of chamomile essential oil. The cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). A549, Hepg2 and L929 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM). MDA-MB-231 cell line was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium. All cell lines were supplemented with 1 % penicillin and 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % O2 humidified cell incubator. When the growth of cell monolayer reached 70–80 % confluence, 0.25 % trypsin was used for digestion and passage.

Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 culture flasks at 5 × 105/mL, harvested by trypsinization (0.05 % trypsin), and checked for reproduction daily up to 96 h. The cells were sub-cultured for three passages to check the consistency of growth, confluent stage, and viability. Every 3–4 days when the cells reached 70–80 % confluence sub-culturing was performed. To prepare the stock solution (100 mg/mL), the essential oil was dissolved in DMSO. Nine different essential oil concentrations (1,000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.62, 7.81 and 3.9 μg/mL) were prepared by diluting the stock solution with cell culture media. DMSO was used as a vehicle for the essential oil and the concentrations of DMSO in the final OEO exposure solution was ≤ 1 %.

2.2.2.2 Cytotoxicity assay (MTT assay)

The cell viability was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plate each well 1 × 104 cells and allowed adhere for overnight at 37 °C with CO2. The cells were treated with essential oil (3.9–1,000 μg/mL) over different incubation periods (24, 48, and 72 h). After incubation, 20 μL of MTT reagent (5 mg/mL MTT in PBS) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 3 h at dark. Immediately after incubation, 100 μL of DMSO was added to each well. At the end of this period, the optical density of the each well was measured at 590 nm against the reference wavelength of 670 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO). The cell viability was determined by accepting 100 % absorbance of the control group. Independent experiments were done in triplicate and repeated 3 times (n = 9).

2.2.2.3 Statistics

All measurements were carried out in triplicates. Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS v27 software package. Multiple comparisons of treatments were performed using one-way ANOVA and Post Hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. The results were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed using MS Excel software. A difference was considered to have significance at p < 0.05.

3 Results

Table 1 presents the chemical composition of the essential oil extracted from flowers, revealing a total of 47 constituents that collectively account for 99.86 % of the oil’s content. Among these constituents, several prominent compounds stand out, each comprising over 3 % of the oil’s composition. The primary constituents include (Z)-β-farnesene, constituting 33.90 % of the oil, followed by α-bisabolol oxide B at 11.60 %, (E,E)-α-farnesene at 11.00 %, α-bisabolol oxide A at 6.79 %, germacrene D at 5.96 %, chamazulene at 5.04 %, α-bisabolone oxide A at 4.18 %, and cis-Spiroether at 3.16 %. Additionally, Table 1 outlines the distribution of major aroma substance groups within the oils. Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons emerge as the dominant group, constituting 64.05 % of the chamomile oil. Following closely are oxygenated sesquiterpenes at 28.79 %, aliphatic hydrocarbons at 3.17 %, monoterpene hydrocarbons at 3.08 %, oxygenated aliphatics at 0.40 %, phenyl propanoids at 0.22 %, oxygenated monoterpenes at 0.21 %, and furans at 0.08 %.

Chemical composition of German chamomile essential oil.

| Peak | RTa | RIb | Compounds | % of TICc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 9.69 | 930 | α-pinene | 0.09 ± 0.0 |

| 2. | 11.00 | 967 | Sabinene | 0.17 ± 0.0 |

| 3. | 11.58 | 986 | 2-pentyl furan | 0.08 ± 0.0 |

| 4. | 12.69 | 1,022 | p-cymene | 0.22 ± 0.0 |

| 5. | 12.81 | 1,024 | Limonene | 0.13 ± 0.0 |

| 6. | 12.92 | 1,026 | Eucalyptol | 0.10 ± 0.0 |

| 7. | 13.08 | 1,035 | β-trans-Ocimene | 0.19 ± 0.0 |

| 8. | 13.42 | 1,043 | β-cis-Ocimene | 1.14 ± 0.0 |

| 9. | 13.77 | 1,055 | γ-terpinene | 0.92 ± 0.0 |

| 10. | 14.64 | 1,090 | Terpinolene | 0.44 ± 0.0 |

| 11. | 22.25 | 1,342 | 7-epi-Silphiperfol-5-ene | 0.10 ± 0.0 |

| 12. | 23.02 | 1,370 | α-copaene | 0.15 ± 0.0 |

| 13. | 23.20 | 1,380 | Silphiperfol-6-ene | 0.13 ± 0.0 |

| 14. | 23.37 | 1,390 | α-isocomene | 0.63 ± 0.0 |

| 15. | 23.97 | 1,410 | β-isocomene | 0.08 ± 0.0 |

| 16. | 24.20 | 1,420 | β-caryophyllene | 0.44 ± 0.0 |

| 17. | 24.66 | 1,434 | Aromadendrene | 0.16 ± 0.0 |

| 18. | 25.12 | 1,440 | (Z)-β-farnesene | 33.90 ± 0.30 |

| 19. | 25.21 | 1,456 | allo-Aromadendrene | 0.18 ± 0.0 |

| 20. | 25.62 | 1,475 | γ-muurolene | 0.42 ± 0.0 |

| 21. | 25.78 | 1,488 | Germacrene D | 5.96 ± 0.05 |

| 22. | 25.91 | 1,492 | cis-β-guaiene | 1.14 ± 0.01 |

| 23. | 25.97 | 1,494 | β-selinene | 0.31 ± 0.0 |

| 24. | 26.01 | 1,497 | Viridiflorene | 0.45 ± 0.0 |

| 25. | 26.13 | 1,501 | Bicyclogermacrene | 2.98 ± 0.0 |

| 26. | 26.32 | 1,505 | (E,E)-α-farnesene | 11.00 ± 0.10 |

| 27. | 26.37 | 1,508 | β-bisabolene | 0.17 ± 0.0 |

| 28. | 26.52 | 1,515 | γ-cadinene | 0.15 ± 0.0 |

| 29. | 26.64 | 1,520 | δ-cadinene | 0.56 ± 0.0 |

| 30. | 27.60 | 1,535 | cis-Nerolidol | 0.12 ± 0.0 |

| 31. | 28.04 | 1,581 | Spathulenol | 0.50 ± 0.0 |

| 32. | 28.25 | 1,588 | Globulol | 0.35 ± 0.0 |

| 33. | 28.46 | 1,594 | Viridiflorol | 0.27 ± 0.0 |

| 34. | 29.89 | 1,662 | α-bisabolol oxide B | 11.60 ± 0.10 |

| 35. | 30.45 | 1,683 | α-bisabolone oxide A | 4.18 ± 0.04 |

| 36. | 30.50 | 1,688 | α-bisabolol | 1.40 ± 0.01 |

| 37. | 31.53 | 1721 | Chamazulene | 5.04 ± 0.05 |

| 38. | 31.94 | 1747 | α-bisabolol oxide A | 6.79 ± 0.06 |

| 39. | 33.76 | 1848 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 0.38 ± 0.0 |

| 40. | 34.61 | 1882 | cis-Spiroether | 3.16 ± 0.03 |

| 41. | 35.44 | 1907 | Methyl hexadecanoate | 0.23 ± 0.0 |

| 42. | 36.77 | 1969 | Ethyl hexadecanoate | 0.17 ± 0.0 |

| 43. | 38.64 | 1991 | Geranyl linalool | 0.11 ± 0.0 |

| 44. | 42.28 | 2,298 | Tricosane | 0.18 ± 0.0 |

| 45. | 45.51 | 2,500 | Pentacosane | 0.52 ± 0.0 |

| 46. | 49.51 | 2,702 | Heptacosane | 0.18 ± 0.0 |

| 47. | 51.02 | 2,801 | Octacosane | 2.29 ± 0.02 |

| Aliphatic hydrocarbons,% | 3.17 | |||

| Oxygenated aliphatics,% | 0.40 | |||

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons,% | 3.08 | |||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes,% | 0.21 | |||

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons,% | 64.05 | |||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes,% | 28.79 | |||

| Furans,% | 0.08 | |||

| Phenyl propanoids,% | 0.22 |

-

aretention time, min; bretention (Kovat’s) index; ctotal ion current.

MTT assay was performed as three separate experiments to examine the cytotoxicity and the growth inhibitory potential of chamomile essential oil. The IC50 values of tested concentrations of chamomile essential oil are summarized in Table 2. It is clearly shown that essential oil showed nearly same cytotoxicity to all cancer cell lines.

IC50 values of samples showing anticancer activity against different cancer cell lines.

| Cell lines | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| L929 | 76.9 | 74.35 | 50.84 |

| A549 | 69.36 | 63.37 | 59.1 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 67.27 | 43.76 | 28.97 |

| HepG2 | 74.21 | 55.1 | 27.75 |

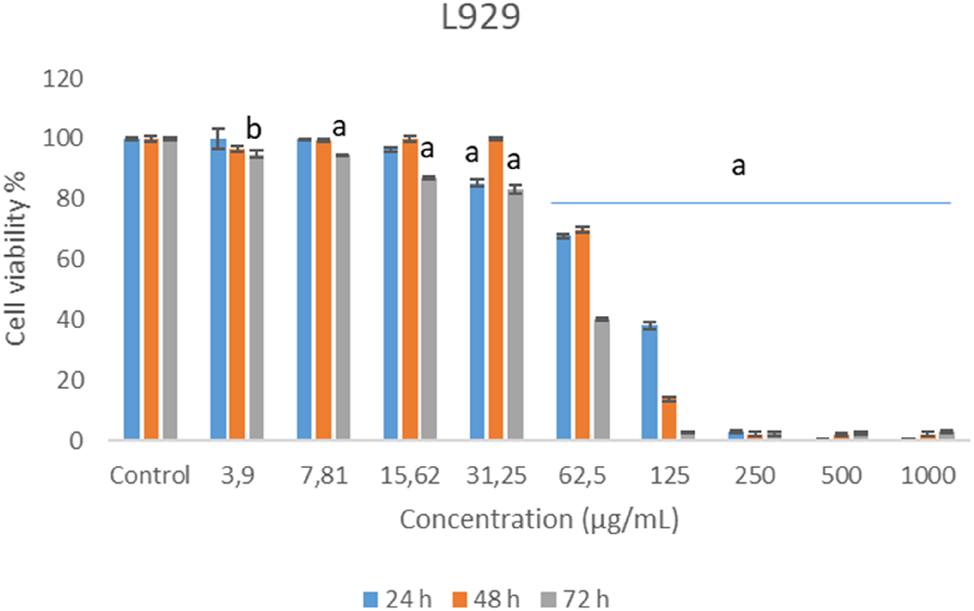

Cytotoxic activity of chamomile essential oil in L929 cell lines is illustrated in Figure 1. All tested concentrations show reduced cell survival when compared with solvent control. This decrease was generally shown in 72 h exposure of 3.9, 7.81 and 15.62 μg/mL concentrations and all exposure times of 62.50 μg/mL and higher concentrations (Figure 1).

Cytotoxic effects of German chamomile essential oil in L929 cell lines.

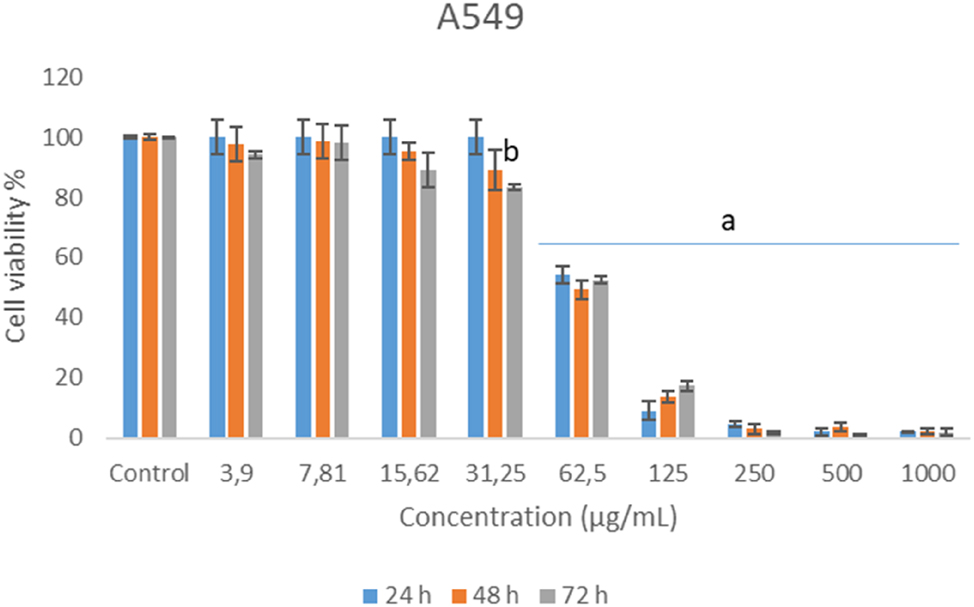

Figure 2 shows anti-proliferative activity of chamomile essential oil against human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial (A549) cell lines. All concentrations decreased the proliferation when compared with solvent control but the decrease was only found statistically significant levels at 72 h exposure of 31.25 μg/mL and all tested concentrations and exposure times of highest ones. The highest three concentrations showed nearly 100 % reduction in cell survival.

Cytotoxic effects of German chamomile essential oil in A549 cell lines.

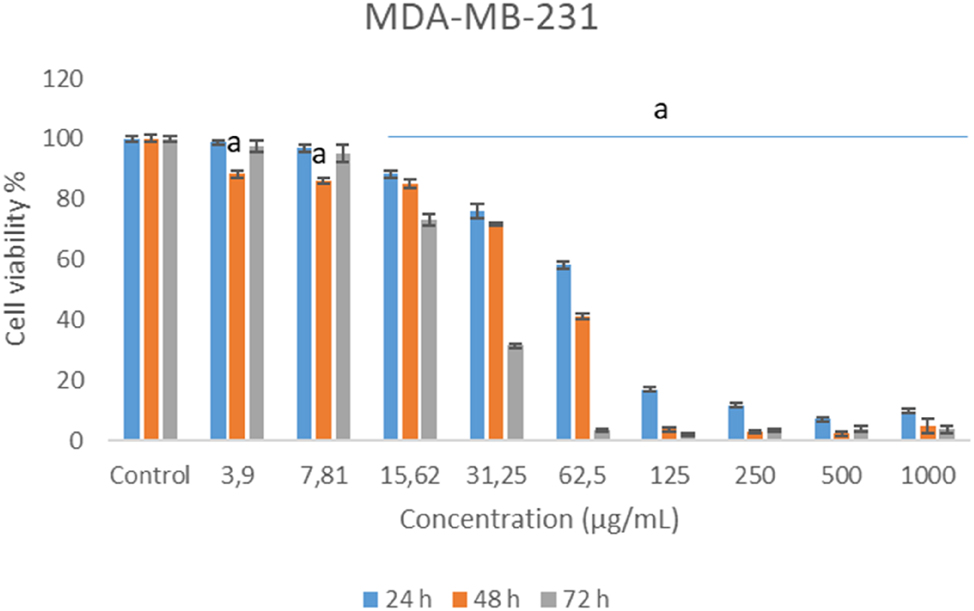

Chamomile essential oil decreased cell survival of human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231) at all concentrations tested. The reduction was found statistically significant levels at especially over 7.81 μg/mL concentrations. The highest decrease was observed at 250, 500 and 1,000 μg/mL concentrations (Figure 3).

Cytotoxic effects of German chamomile essential oil in MDA-MB-231 cell lines.

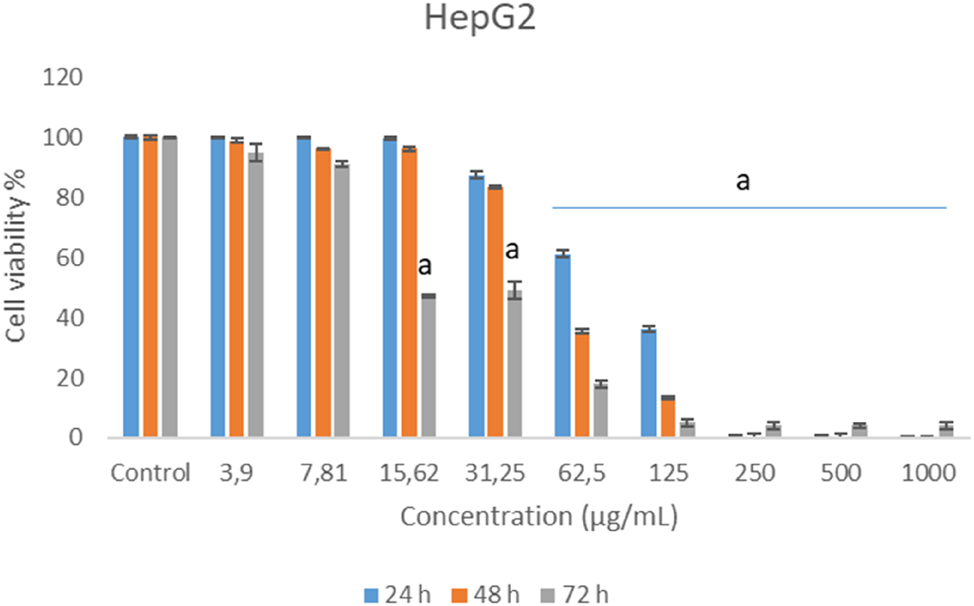

Concentrations of chamomile essential oil significantly reduced cell survival of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2) at 72 h exposure of 15.62 and 31.25 μg/mL and all exposure time of 62.5 μg/mL and over concentrations (Figure 4).

Cytotoxic effects of German chamomile essential oil in HepG2 cell lines.

4 Discussion

Based on its chemical composition, the studied chamomile essential oil can be classified as the β-farnesene chemotype, which distinguishes it from data in the literature. In our opinion, this difference may be attributed to soil and climatic conditions, as well as the various chemotypes of chamomile that grow in different regions of Europe [1].

Chamomile essential oil is rich in bioactive compounds that contribute to its pharmacological effects. One of its notable properties is its anti-inflammatory activity, attributed to constituents such as bisabolol oxide A and B. These compounds inhibit inflammatory pathways and reduce swelling, making chamomile oil effective in treating inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, dermatitis, and gastrointestinal inflammation. In this study, we determined chemical composition of chamomile essential oil and tried to figure out anti-carcinogenic profile using human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (A549), human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), mouse fibroblast cells (L929), and human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231). Our results clearly show that CEO has strong anti-proliferative capacity to all used cell lines especially at higher concentrations and treatment period.

The potential beneficial effects of chamomile essential oil were also noted in several studies. The essential oil demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability, with an IC50 of approximately 300 μg/mL. Furthermore, it significantly inhibited the levels of important angiogenesis markers in both HepG2 cells and ex vivo, as reported by [24]. Sak et al. [25] investigated the potential anticancer effects of extracts from German chamomile on human melanoma and epidermoid carcinoma cells. Methanolic extracts from chamomile flowers were evaluated using the sulforhodamine B assay to measure cytotoxic activity. The IC50 value of chamomile flower extract against melanoma cells (40.7 μg/mL) was approximately twofold higher than that against epidermoid carcinoma cells (71.4 μg/mL).

Shaaban et al. [26] have shown that the (Z)-β-farnesene component in M. chamomilla extracts has significant anticancer potential, inhibiting Caco-2 colon cancer cell migration. The (Z)-β-farnesene component in essential oil obtained from the leaves of Cedrelopsis grevei, an aromatic and medicinal plant from Madagascar, has shown a significant correlation with anticancer activity (on human breast cancer cells MCF-7) [27]. The anticancer effects and mechanisms of α-bisabolol in numerous types of cancer including, pancreatic, endometrial, breast and liver have been demonstrated in many experimental studies [28], 29]. Additionally, upregulating the expression of bcl-2 and suppression of bax, P53, APAF-1, caspase-3 and caspase-9 activity indicates the anti-apoptotic effects of α-bisabolol [28]. The molecular mechanisms underlying anti-apoptotic effects of α-bisabolol were proven in different study models. Based on those research studies, upregulating the expression anti-apoptotic bcl-2 expressions and suppression of the bax, P53, APAF-1, caspase-3 and caspase-9 activity indicates the anti-apoptotic effect α-bisabolol. It is noteworthy that, two probable molecular mechanisms for anticancer effects of α-bisabolol appear to be through NF-κB and PI3K/PDK1/Akt signaling pathways [29].

Santos et al. [30] evaluated the effects of combining the antineoplastic drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) with Matricaria recutita flower extract (MRFE) in treating mice transplanted with sarcoma 180. They assessed tumor inhibition, variations in body and visceral mass, as well as biochemical, hematological, and histopathological parameters. The study found that both isolated 5-FU and combinations of 5-FU with MRFE at doses of 100 mg/kg/day and 200 mg/kg/day reduced tumor growth. Notably, the 5-FU + MRFE at 200 mg/kg/day demonstrated a more significant reduction in tumor size compared to 5-FU alone. These findings suggest that the combination of 5-FU with MRFE at 200 mg/kg/day may enhance antitumor activity while reducing chemotherapy-induced loss of body mass and minimizing toxicity.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we explored the chemical composition and anti-cancer potential of Matricaria recutita L. essential oil from Southern Bulgaria. The detailed analysis revealed that the essential oil primarily belongs to the β-farnesene chemotype, a distinction influenced by the specific soil and climatic conditions of the region. This chemotype variation emphasizes the importance of geographic and environmental factors in defining the chemical profiles of essential oils. Our investigation into the anti-cancer properties demonstrated promising results, particularly against select cancer cell lines. The bioactive compounds identified within the oil, including chamazulene, α-bisabolol, and apigenin, have shown significant cytotoxic effects, supporting the potential of chamomile essential oil as a complementary approach in cancer treatment. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence suggesting that natural products, particularly those derived from Matricaria recutita L., could play a valuable role in cancer treatment.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have equal contribution.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Başer, K, Buchbauer, G. Handbook of essential oils: science, technology, and applications. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Bauer, K, Garbe, D, Surburg, H. Common fragrance and flavor materials. In: Preparation, properties and uses, 4th completely revised ed. Weinheim, New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto: Wiley VCH; 2001.10.1002/3527600205Suche in Google Scholar

3. Stoyanova, A. A guide for the specialist in the aromatic industry. Plovdiv: Bulgarian National Association of Essential Oils, Perfumery and Cosmetics;2022.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Ayoughi, F, Barzegar, M, Sahari, M, Naghdibadi, H. Chemical compositions of essential oils of Artemisia dracunculus L. and endemic Matricaria chamomilla L. and an evaluation of their antioxidative effects. J Agric Sci Technol 2011;13:79–88.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Farhoudi, R. Chemical constituents and antioxidant properties of Matricaria recutita and Chamaemelum nobile essential oil growing wild in the south west of Iran. J Essent Oil Bear Plants 2013;4:531–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060x.2013.813219.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Pirzad, A, Alyari, H, Shakiba, MS, Zehtab-Salmasi, A, Mohammadi. Essential oil content and composition of German chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) at different irrigation regimes. J Agron 2006;5:451–5. https://doi.org/10.3923/ja.2006.451.455.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Roby, M, Sarhan, M, Selim, K, Khalel, K. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Ind Crops Prod 2013;44:437–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.10.012.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Shams-Ardakani, M, Ghannadi, A, Rahimzadeh, A. Volatile constituents of Matricaria chamomilla L. From isfahan, Iran. Iran J Pharm Sci 2006;2:57–60.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Singh, O, Khanam, NZ, Srivastava, MM. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): an overview. Pharmacogn Rev 2011;5:82–95.10.4103/0973-7847.79103Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Stanojevic, L, Marjanovic-Balaban, Z, Kalaba, V, Stanojevic, J, Cvetkovic, D. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of chamomile flowers essential oil (Matricaria chamomilla L). J Essent Oil Bear Plants 2016;19:2017–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060x.2016.1224689.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Abdoul-Latif, F, Mohamed, N, Edou, P, Ali, AA, Djama, SO, Obame, L, et al.. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil and methanol extract of Matricaria chamomilla L. from Djibouti. J Med Plants Res 2011;5:1512–17.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Das, S, Horváth, B, Széchenyi, A, Šafranko, S, Koszegi, T, Kőszegi, T. Antimicrobial activity of chamomile essential oil: effect of different formulations. Molecules 2019;24:4321. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24234321.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Göger, G, Demirci, B, Ilgın, S, Demirci, F. Antimicrobial and toxicity profiles evaluation of the chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) essential oil combination with standard antimicrobial agents. Ind Crop Prod 2018;120:279–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.04.024.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Gupta, V, Mittal, P, Bansal, P, Khokra, S, Kaushik, D. Pharamacological potential of Matricaria recutita. Int J Pharmaceut Sci Drug Res 2010;2:12–16. https://doi.org/10.25004/ijpsdr.2010.020102.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Fırat, Z, Demirci, F, Demirci, B. Antioxidant activity of chamomile essential oil and main components. Nat Volatiles and Essent Oils 2018;1:11–16.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Katrin, S, Thi Hoai, N, Viet, DH, Thi, TD, Ain, R. Cytotoxic effect of chamomile (Matricaria recutita) and marigold (Calendula officinalis) extracts on human melanoma SK-MEL-2 and epidermoid carcinoma KB cells. Cogent Med 2017;4:1333218. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205x.2017.1333218.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Mahmmod, Z. The effect of chamomile plant (Matricaria chamomile L.) as feed additives on productive performance, carcass characteristics and immunity response of broiler. Int J Poultry Sci 2013;2:111–16.10.3923/ijps.2013.111.116Suche in Google Scholar

18. McKay, D, Blumberg, J. A Review of the bioactivity and potential health benefits of chamomile tea (Matricaria recutita L). Phytother Res 2006;20:519–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.1900.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Zhang, X, Sun, D, Qin, N, Liu, M, Zhang, J, Li, X. Comparative prevention potential of 10 mouthwashes on intolerable oral mucositis in cancer patients: a Bayesian network analysis. Oral Oncol 2020;107:104751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104751.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Maleki, M, Mardani, A, Manoochehri, M, Farahani, MA, Vaismoradi, M, Glarcher, M. Effect of chamomile on the complications of cancer: a systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther 2023;22. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347354231164600. In this issue.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Mostafapour Kandelous, H, Salimi, M, Khori, V, Rastkari, N, Amanzadeh, A, Salimi, M. Mitochondrial apoptosis induced by Chamaemelum nobile extract in breast cancer cells. Iran J Pharm Res 2016;15:197–204.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Noronha, M, Pawar, V, Prajapati, A, Subramanian, RB. A literature review on traditional herbal medicines for malaria. South Afr J Bot 2020;128:292–303.10.1016/j.sajb.2019.11.017Suche in Google Scholar

23. Adams, R. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, 4th ed. Illinois: Allured Publishing Co., Carol Stream; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Al-Dabbagh, B, Elhaty, İA, Elhaw, M, Murali, C, Mansoori, AA, Awad, B, et al.. Antioxidant and anticancer activities of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.). BMC Res Notes 2019;12:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3960-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Sak, K, Nguyen, TH, Ho, VD, Do, TT, Raal, A. Cytotoxic effect of chamomile (Matricaria recutita) and marigold (Calendula officinalis) extracts on human melanoma SK-MEL-2 and epidermoid carcinoma KB cells. Cogent Med 2017;41. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2017.1333218. In this issue.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Shaaban, M, El-Hagrassi, AM, Osman, AF, Soltan, MM. Bioactive compounds from Matricaria chamomilla: structure identification, in vitro antiproliferative, antimigratory, antiangiogenic, and antiadenoviral activities. Z Naturforsch, C: J Biosci 2022;77:85–94. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-2021-0083.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Afoulous, S, Ferhout, H, Raoelison, EG, Valentin, A, Moukarzel, B, Couderc, F, et al.. Chemical composition and anticancer, antiinflammatory, antioxidant and antimalarial activities of leaves essential oil of Cedrelopsis grevei. Food Chem Toxicol 2013;56:352–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Eddin, LB, Jha, NK, Goyal, SN, Agrawal, YO, Subramanya, SB, Bastaki, SMA, et al.. Health benefits, pharmacological effects, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic potential of α-bisabolol. Nutrients 2022;14:1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071370.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Ramazani, E, Akaberi, M, Emami, SA, Tayarani-Najaran, Z. Pharmacological and biological effects of alpha-bisabolol: an updated review of the molecular mechanisms. Life Sci 2022;304:120728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120728.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Santos, SA, Amaral, RG, Graça, AS, Gomes, SVF, Santana, FP, de Oliveira, IB, et al.. Antitumor profile of combined Matricaria recutita flower extract and 5-Fluorouracil chemotherapy in Sarcoma 180 in Vivo Model. Toxics 2023;11:375. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11040375.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.