Abstract

A new isoquinoline quinone system and its iodinated derivatives were isolated from the ascidian tunicate Ascidia virginea Müller 1776 (Phlebobranchia: Ascidiidae). Structures were elucidated by spectroscopic methods and derivatization reactions. Ascidine A (3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione (1), ascidine B (3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxy-3′-iodophenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione (2), and ascidine C (3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-diiodophenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione (3) represent a novel type of tyrosine-derived alkaloids.

1 Introduction

Ascidians have been shown to produce a wide variety of biologically active natural products [1]. The majority of the ascidian species studied so far are of tropical, subtropical, or Mediterranean origin, whereas only few species from the Northeastern Atlantic have been investigated [2, 3]. To the best of our knowledge, (R)-2,6-dimethylheptyl sulfate, which is relatively wide spread among Ascidians, is the only secondary metabolite known from A. virginea (http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=103717). Here we report on the isolation and structure elucidation of three unprecedented isoquinoline quinones isolated from the red colored Ascidia virginea, an ascidian frequently found in the Norwegian fjords [4].

2 Results and discussion

Frozen specimens of A. virginea were homogenized and subsequently extracted with acetone. The resulting extracts were combined and concentrated to give an inhomogeneous aqueous residue, which was extracted with dichloromethane. The 1H NMR spectrum of the crude, deep red-colored extract revealed the presence of relatively large amounts of unsaturated and/or aromatic compounds. Fractionation over Sephadex LH-20, followed by HPLC separation, revealed the red-colored fraction to contain two major components, 1 and 2, and a minor component 3, which we named ascidine A, B, and C, respectively. The UV–vis spectra of these compounds showed maxima at 485 and 322 nm.

Mass spectra were acquired using atmospheric pressure and chemical ionization in negative ion mode (NI-APCI-MS). The mass spectrum of the crude extract (Figure 1) was dominated by three intense signals at m/z 283, m/z 409, and m/z 535, which were assigned to ascidines A, B, and C (1, 2, and 3). HPLC/HR-MS revealed their elemental composition to be C15H9NO5 (m/z 283, 1), C15H8INO5 (m/z 409, 2), and C15H7I2NO5 (m/z 535, 3). These data suggested 1–3 to form molecular ions [M]− by electron capture (EC) rather than pseudo-molecular ions [M–H]− via deprotonation. EC is well known to occur with halogenated compounds but is also characteristic for carbonyl compounds such as quinones [5]. The easiness of 1–3 to undergo EC was helpful for structure assignments of these compounds. Since the nonhalogenated component 1 was no less susceptible to EC than the iodinated compounds 2 and 3, the presence of a quinoid substructure seemed likely, which was supported by the relatively high number of oxygens in all three compounds as well as by their remarkably intense red color.

NI-APCI-mass spectrum of the crude extract of A. virginea.

In addition to ascidines A–C (1–3), some trace components (4–6) were detected by NI-APCI-MS. The isotopic patterns and masses of molecular ions at m/z 361/363, m/z 439/441/443, and m/z 487/489 suggested the formulas C15H8BrNO5 (4), C15H7Br2NO5 (5), and C15H7BrINO5 (6), presumably corresponding to brominated derivatives of 1–3. However, owing to their low abundance, the elemental compositions of 4–6 could not be determined by HR-MS.

Compounds 1 and 2 could be isolated by preparative HPLC in quantities sufficient for NMR-spectroscopic analysis. The low number of hydrogen atoms as determined by high-resolution MS corresponded to very simple 1H NMR-spectra (see Tables 1 and 2 ). Ascidine A (1) showed three singlets (8.69, 8.93, and 9.90 ppm), each representing one proton, one pair of doublets, and an aromatic AA′BB′ system. Using HMQC and HMBC experiments, the doublets at 6.72 and 7.34 ppm were shown to represent a cis-substituted double bond, which was likely conjugated with a carbonyl group. The AA′BB′ system at 6.89 and 7.20 ppm indicated the presence of a para-substituted phenol. Subtracting this phenol unit (C6H4OH) from the overall molecular formula C15H9NO5, left a C9H4NO4 core to be characterized.

NMR data of ascidine A (1).a

| Position | 13C δ [ppm] | 1H δ [ppm] | COSY90 | HMBC | NOESY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 162.33 | ||||

| 3 | 161.28 | ||||

| 4 | 126.58 | ||||

| 4a | 136.94 | ||||

| 5 | 138.93 | 7.34, 1H, d, J=10.0 Hz | H-6 | C-1, C-4, C-4a, C-7, C-8, C-8a, C-6a | H-6 |

| 6 | 129.64 | 6.72, 1H, d, J=10.0 Hz | H-5 | C-3, C-4a, C-7, C-8, C-8a | H-5 |

| 7 | 179.80 | ||||

| 8 | 148.58 | ||||

| 8a | 92.46 | ||||

| 1′ | 122.63 | ||||

| 2′/6′ | 133.11 | 7.20, 2H, d, J=8.5 Hz | H-3′/5′ | C-3a, C-4, C-4aa, C-2′/6′, C-4′, C-3′/5′ | H-3′/5′ |

| 3′/5′ | 114.91 | 6.89, 2H, d, J=8.5 Hz | H-2′/6′ | C-4a, C-1′, C-2′/6′, C-3′/5′, C-4′ | H-2′/6′, 4′-OH |

| 4′ | 158.40 | ||||

| 1-OH | – | 8.69, 1H, s(b) | C-7, C-8a | 8-OHb | |

| 8-OH | – | 8.93, 1H, s(b) | C-7 | 1-OHb | |

| 4′-OH | – | 9.90, 1H, s | – | C-2′/6′, C-3′/5′, C-4′ | H-3′/5′ |

aRecorded in DMSO-d6, 1H: 500 MHz, 13C: 100.6 MHz.

NMR data of ascidine B (2).a

| Position | 13C δ [ppm] | 1H δ [ppm] | COSY90 | HMBC | NOESY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 162.6a | ||||

| 3 | ? | ||||

| 4 | 125.0 | ||||

| 4a | 137.4 | ||||

| 5 | 138.7 | 7.32, 1H, d, J=10.0 Hz | H-6 | C-1, C-4, C-4a, C-7, C-8a | H-6, H-2′ |

| 6 | 130.0 | 6.72, 1H, d, J=10.0 Hz | H-5, OH-8 | C-4a, C-8 | |

| 7 | 180.0 | ||||

| 8 | 148.9 | ||||

| 8a | 92.6 | ||||

| 1′ | 125.0 | ||||

| 2′ | 141.6 | 7.69, 1H, d, J=2.1 Hz | H-6′ | C-1′, C-3′, C-4′, C-6′ | |

| 3′ | 84.2 | ||||

| 4′ | 157.7 | ||||

| 5′ | 114.2 | 6.99, 1H, d, J=8.3 Hz | H-6′ | C-1′, C-3′, C-4′ | |

| 6′ | 133.0 | 7.20, 1H, dd, J=2.1 Hz, 8.3 Hz | H-2′, H-5′ | C-1′, C-2′, C-4′ | |

| 1-OH | – | 8.74, 1H, s(b) | 8-OHb | ||

| 8-OH | – | 8.97, 1H, s(b) | C-7 | 1-OHb | |

| 4′-OH | – | 10.82, 1H, s(b) |

aRecorded in DMSO-d6, 1H: 500 MHz, 13C: 100.6 MHz.

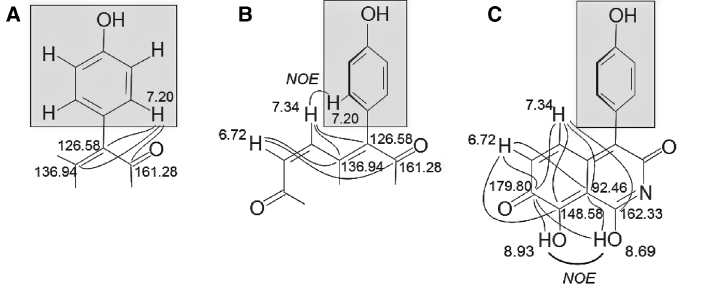

The 13C NMR spectrum of ascidine A (1) displayed 13 signals for the 15 carbon atoms. Four signals (114.91, 122.63, 133.11, and 158.40 ppm) were assigned to the six carbon atoms of the p-hydroxyphenyl substituent. Of the remaining nine signals, two sp2-methines (129.64, 138.93 ppm) represented the aforementioned cis-double-bond while the remaining seven signals belonged to sp2-quarternary carbons (92.46, 126.58, 136.94, 148.58, 161.28, 162.33, and 179.80 ppm). HMBC cross peaks of the protons at 7.20 ppm of the p-hydroxyphenyl unit to carbon atoms at 161.28, 126.58, and 136.94 ppm allowed the connection of this substituent to the C9H4NO4 core (Figure 2A).

Selected HMBC and NOE correlations in ascidine A (1).

The proximity of the cis-double bond to the attachment site of the hydroxyphenyl substituent was evident from HMBC cross peaks of the protons at 6.72 and 7.34 ppm, which are part of the C9H4NO4 unit. In addition, NOESY cross peaks between the proton at 7.34 ppm of the cis-double bond and the protons at 7.20 ppm of the p-hydroxyphenyl substituent supported the partial structure shown in Figure 2B. The NOESY and HMBC spectra of 1 are shown as supporting material.

The remaining two protons, which appeared as broad singlets at 8.69 and 8.93 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum, were assigned to two phenolic hydroxy groups. A positive NOESY cross peak between these two hydroxy groups indicated spatial proximity (Figure 2C). The remarkably low chemical shift of 92.46 ppm – unusual for an sp2-hybridized carbon atom – suggested this carbon to be spatially close to the two phenolic hydroxy groups. C–H-long-range correlations of the cis-double bond protons (6.72 and 7.34 ppm) and of the OH groups (8.69 and 8.93 ppm) to the keto group (179.80 ppm) as well as to the quarternary carbon at 92.46 ppm allowed to complete the structure. The placement of C-1 was based on HMBC cross peaks from H-5 (Figure 2C). The position of the nitrogen as part of an imide is in agreement with the 13C chemical shifts of the adjacent carbons (C-1 and C-3) and was supported by intense IR-absorption bands at 1617, 1598, and 1587 cm−1 [6]. Thus, the C9H4NO4 core was assigned to be a 3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxyisoquinolin-3,7-dione and, consequently, compound 1 (ascidine A) was identified as 3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)isoquinolin-3,7-dione.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the iodinated 2 differed from that of 1 by showing a three-proton spin system corresponding to a 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group, which replaced the AA′BB′ system found in 1. 1H,1H-COSY, and HMBC data revealed the iodine substituent to be in ortho-position to the hydroxy group of the hydroxyphenyl substituent. The 1H and 13C signals of the remaining C9H4NO4 core were almost identical to those of 1, and consequently, ascidine B was identified to be 3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxy-3′-iodophenyl)isoquinolin-3,7-dione. The 1D and 2D NMR data of the compound are given in Table 2.

Having the structures of ascidine A and B assigned, the structures of the minor compound 3 and the trace components 4–6, which could not be isolated or fully characterized, were proposed. The doubly iodinated 3 (ascidine C) was likely to have both iodine substituents placed in ortho-position to the hydroxy group of the hydroxyphenyl substituent – a structural motif well known from other iodinated aromatic natural products [7]. To scrutinize this assumption, ascidine A (1) was treated with the mild iodination reagent bis(pyridine)iodonium tetrafluoroborate [8, 9], which is known to transform phenols into their ortho-mono- and diiodo derivatives. As expected, the crude reaction mixture contained both ascidine B (2) and a doubly iodinated compound that was identical with 3 with respect to HPLC retention time and mass spectrometric properties. Thus, the structure of 3 was assigned to be the 3′,5′-diiodo derivative of 1. Furthermore, based on mass spectroscopic evidence, we propose the trace components 4–6 (ascidines D, E, and F) to be halogenated derivatives of 1, namely 4 is 3′-bromo-1 and 5 is 3′,5′-dibromo-1, whereas 6 is 5′-bromo-3′-iodo-1.

Oxygenated isoquinoline antibiotics are widespread natural products. Several 5,8-dihydroisoquinoline-5,8-diones such as the yellow mimosamycin, isolated from a Streptomyces strain [10, 11], or the cytotoxic caulibugulone A and its 6-halogenated derivatives, constituents of the marine bryozoan Caulibugula intermis [12] (for structures, see Figure 3), as well as structurally related 5,8-isoquinoline quinones have been described from marine sponges [13, 14] or nudibranchs [15]. However, in contrast to all these compounds, the newly discovered ascidines represent an unprecedented suite of 3,7-isoquinolone quinones. Nevertheless, mimosamycin shows an oxygenation pattern similar to that of the new natural products. The discovery of these secondary metabolites, featuring an intensively red chromophore, raises the question of their physiological or ecological function in the tunicate. To date nothing is known about predators of A. virginea or its need to control bacterial or fungal overgrowth. However, it is remarkable that in contrast to several closely related species found in the same habitat, such as Ascidia mentula, sampled specimens of A. virginea never appeared to be damaged by feeders and did not show any signs of infestation by microorganisms. Given their unusual structures, it is likely that the novel ascidines play a significant role in the chemical ecology of this ascidian. Investigations on the biological properties of the ascidines are in progress.

Stuctures of ascidines, mimosamycin, and caulibugulone A.

3 Experimental section

3.1 General experimental procedures

IR spectra were recorded with a Thermo Nicolet® Avatar 370 FT IR spectrometer. NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker DRX 500 (500 MHz) and AMX 400 (400 MHz) as well as Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometers. Low- and high-resolution mass spectrometry was performed on a ThermoQuest® Finnigan MAT 95XL mass spectrometer, equipped with an APCI source. Analytical and preparative HPLC separations were carried out with Merck-Hitachi® HPLC systems, using an L-4500 diode array detector for the acquisition of UV spectra.

3.2 Animal material

Specimens of Ascidia virginea were collected in the Korsfjord area of Bergen, Norway. Sampling was performed with a triangular dredge from the research vessel “Hans Brattström” at 60 m depth. The samples were frozen and stored at −30 °C until extraction.

3.3 Extraction and purification

Wet frozen material (170 g) was homogenized and extracted three times with 100-mL acetone (Merck, SupraSolv® grade). The total acetone extract was concentrated, and the aqueous residue first extracted with pentane to remove lipophilic material and subsequently with dichloromethane. The dichloromethane layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. Chromatography of the crude natural products was performed over a column packed with Sephadex LH-20 using acetone–dichloromethane 1:1, which was monitored visually via the red color of components. The red-colored fractions containing the ascidines were submitted to HPLC, using a Kromasil® RP-18 column (21.2×250 mm, 5 μm particle size) and acetonitrile–water 1:1. Ascidine A (1) eluted before its 3′-iodo derivative 2.

Ascidine A (=3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione, 1). Dark red amorphous powder (acetone). UV–vis (acetonitrile-water 1:1): λmax=322 nm, 485 nm. IR (KBr): 3530, 3365, 3276, 1734, 1707, 1617, 1598, 1587, 1375, 1310, 1285, 1238, 1188, 1162, 1117, 1094, 1027, 982, 843, 638 cm−1. NMR: see Table 1. HR-APCI-MS: m/z 283.0474 (calcd for C15H9NO5, 283.0481).

Further details concerning NMR-spectra of Ascidine A are provided in the Supplement.

Ascidine B (=3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxy-3′-iodophenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione, 2). Red amorphous powder (acetone or dichloromethane). UV–vis (acetonitrile–water 1:1): λmax=322 nm, 485 nm. IR (KBr): ν 3422, 3318, 1735, 1686, 1585, 1384, 1311, 1288, 1233, 1140, 1094, 985, 841, 802 cm−1. NMR: see Table 2. HR-APCI-MS: m/z 408.9441 (calculated for C15H8INO5, 408.9447).

Further details concerning NMR-spectra of Ascidine B are provided in the Supplement.

Ascidine C (=3,7-dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-4-(4′-hydroxy-3′,5′-diiodophenyl)isoquinoline-3,7-dione, 3). HR-APCI-MS: m/z 534.8416 (calcd for C15H7I2NO5, 534.8414).

3.4 Conversion of ascidine A into ascidines B and C

A sample of 1 (~50 μg) was dissolved in dry dichloromethane (1–2 mL) and treated with a solution of bis(pyridine)iodonium tetrafluoroborate (~130 μg IPy2BF4 in 130-μL dichloromethane, two equivalents). After stirring for 20 min at room temperature, the crude reaction mixture was submitted to HPLC/DAD and APCI-MS analysis.

Dedication: In memoriam Lothar Jaenicke

Acknowledgment

This paper represents publication no. 52 of the research program BOSMAN (03F0358 A-F). Financial support was provided by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). Access to the installations at the University of Bergen was supported by the IHP (Improving Human Research Potential) program from the European Union through contract no. HPRI-CT-1999-00056. We are grateful to the Marine Biological Station (University of Bergen, Norway) for sampling. Bioassays were carried out at the Institute of Biotechnology and Drug Research (IBWF), Kaiserslautern, Germany. We would like to acknowledge the excellent collaboration of Prof. Dr. H. Anke (IBWF) and the expertise of Mrs. Anja Meffert.

References

1. Marinlit, Marine Literature DataBase, devised by Murray H. G. Munro, John W. Blunt, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.Search in Google Scholar

2. Barenbrock JS, Köck M. Screening enzyme-inhibitory activity in several ascidian species from Orkney Islands using protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) bioassay-guided fractionation. J Biotechnol 2005;117:225–32.10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.01.009Search in Google Scholar

3. Tadesse M, Gulliksen B, Strøm MB, Styrvold OB, Haug T. Screening for antibacterial and antifungal activities in marine benthic invertebrates from Northern Norway. J Inverteb Pathol 2008;99:286–93.10.1016/j.jip.2008.06.009Search in Google Scholar

4. De Rosa S, Milone A, Crispino A, Jaklin A, De Giulio A. Absolute configuration of 2,6-dimethylheptyl sulfate and its distribution in ascidiacea. J Nat Prod 1997;60:462–3.10.1021/np9605753Search in Google Scholar

5. Gross JH. Mass spectrometry. A textbook. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag, 2004:331.10.1007/3-540-36756-X_7Search in Google Scholar

6. McKittrick PT, Katon JE. Infrared and raman group frequencies of cyclic imides. Appl Spectrosc 1990;44:812–7.10.1366/0003702904087000Search in Google Scholar

7. Carroll AR, Bowden BF, Coll JC. Studies of Australian ascidians. II. Novel cytotoxic iodotyrosine-based alkaloids from colonial ascidians, aplidium sp. Aust J Chem 1993;46:825–32.10.1071/CH9930825Search in Google Scholar

8. Barluenga J, García-Martín MA, González JM, Clapés P, Valencia G. Iodination of aromatic residues in peptides by reaction with IPy2BF4. J Chem Commun 1996;1505–6.10.1039/CC9960001505Search in Google Scholar

9. Barluenga J, González JM, García-Martín MA, Campos PJ, Asensio G. Acid-mediated reaction of bis(pyridine)iodonium(I) tetrafluoroborate with aromatic compounds: a selective and general iodination method. J Org Chem 1993;58:2058–60.10.1021/jo00060a020Search in Google Scholar

10. Fukumi H, Kurihara H, Hata T, Tamura C, Mishima H. Mimosamycin, a novel antibiotic produced by Streptomyces lavendulae No. 314: structure and synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett 1977;43:3825–8.10.1016/S0040-4039(01)83364-5Search in Google Scholar

11. Fukumi H, Maruyama F, Yoshida K, Arai M, Kubo A, Arai T. Production, isolation and chemical characterization of mimosamycin. J Antibiotics 1978;31:847–9.10.7164/antibiotics.31.847Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Milanowski DJ, Gustafson KR, Kelley JA, McMahon JB. Caulibugulones A-F, novel cytotoxic isoquinoline quinones and iminoquinones from the marine bryozoan Caulibugula intermis. J Nat Prod 2004;67:70–3.10.1021/np030378lSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

13. He H, Faulkner DJ. Renieramycins E and F from the sponge Reniera sp.: reassignment of the stereochemistry of the renieramycins. J Org Chem 1989;54:5822–4.10.1021/jo00285a034Search in Google Scholar

14. Plubrukarn A, Yuenyongsawad S, Thammasoroj T, Jitsue A. Cytotoxic isoquinoline quinones from the thai sponge Cribrochalina. Pharmaceutical Biol 2003;41:439–42.10.1076/phbi.41.6.439.17829Search in Google Scholar

15. Huang R-Y, Chen W-T, Kurtán T, Mándi A, Ding J, Li J, et al. Bioactive isoquinolinequinone alkaloids from the South China Sea nudibranch Jorunna funebris and its sponge-prey Xestospongia sp. Future Med Chem 2016;8:17–27.10.4155/fmc.15.169Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplemental Material:

The online version of this article (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-2017-0012) offers supplementary material, available to authorized users.

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Section – Tribute

- Lothar Jaenicke and C1-metabolism: his first 25 years of research

- Lothar Jaenicke (1923–2015) zum Gedächtnis

- Special Section – Research Articles

- The AtMYB12 activation domain maps to a short C-terminal region of the transcription factor

- 3,7-Isoquinoline quinones from the ascidian tunicate Ascidia virginea

- Scent gland constituents of the Middle American burrowing python, Loxocemus bicolor (Serpentes: Loxocemidae)

- Effects of extracts and compounds from Tricholoma populinum Lange on degranulation and IL-2/IL-8 secretion of immune cells

- A succinct access to ω-hydroxylated jasmonates via olefin metathesis

- Research Articles

- PEGylation potentiates hepatoma cell targeted liposome-mediated in vitro gene delivery via the asialoglycoprotein receptor

- A detailed experimental study of a DNA computer with two endonucleases

- Different sensitivities of photosystem II in green algae and cyanobacteria to phenylurea and phenol-type herbicides: effect on electron donor side

- Response of alternative splice isoforms of OsRad9 gene from Oryza sativa to environmental stress

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Section – Tribute

- Lothar Jaenicke and C1-metabolism: his first 25 years of research

- Lothar Jaenicke (1923–2015) zum Gedächtnis

- Special Section – Research Articles

- The AtMYB12 activation domain maps to a short C-terminal region of the transcription factor

- 3,7-Isoquinoline quinones from the ascidian tunicate Ascidia virginea

- Scent gland constituents of the Middle American burrowing python, Loxocemus bicolor (Serpentes: Loxocemidae)

- Effects of extracts and compounds from Tricholoma populinum Lange on degranulation and IL-2/IL-8 secretion of immune cells

- A succinct access to ω-hydroxylated jasmonates via olefin metathesis

- Research Articles

- PEGylation potentiates hepatoma cell targeted liposome-mediated in vitro gene delivery via the asialoglycoprotein receptor

- A detailed experimental study of a DNA computer with two endonucleases

- Different sensitivities of photosystem II in green algae and cyanobacteria to phenylurea and phenol-type herbicides: effect on electron donor side

- Response of alternative splice isoforms of OsRad9 gene from Oryza sativa to environmental stress