Abstract

The FormCopy (FC) analysis of control proposed by Noam Chomsky develops Norbert Hornstein’s movement analysis. This paper points out that there is inconsistency between both analyses and the standard phase theory. Then, it presents a new definition of phase and the PIC that makes reference to ϕ-feature agreement in order to resolve this inconsistency. Minimal Yield (MY) is one of the conditions on Merge that distinguish the FC analysis from the movement analysis. It is a fundamental assumption in the FC analysis but rules out sideward movements employed in the movement analysis. The second part of the paper first introduces Hisatsugu Kitahara’s analysis of “proper binding” effects in terms of MY. Then, it shows that this analysis, together with the newly proposed definition of phase and the PIC, correctly predicts a surprising difference between English and Japanese with respect to the “proper binding” phenomenon. This constitutes further evidence for MY and hence for the FC analysis of control.

1 Introduction

Examples of control, such as (1a), have been analyzed without appeal to movement, in distinction with cases of raising as in (1b).

|

The crucial assumption behind this is that movement into θ-positions is prohibited. However, Hornstein (1999) argued that the assumption was warranted by the definition of D-structure as a pure representation of GF-θ and lost its ground in the Minimalist Program. He proposed to analyze control in terms of movement and to eliminate PRO, which has resisted a satisfactory analysis over the years. (1a) would then be analyzed as in (2), and the analyses for control and raising are unified.

|

Chomsky (2021) adopts Hornstein’s insights but proposes an alternative way to unify control and raising that does not rely on movement into θ-positions. Suppose, as is generally assumed, that Internal Merge copies the moved item at the landing site. Then, the matrix CP phase of (1b) is generated as in (3).

| [ CP [ TP John seems [ TP … John …]]] |

If derivations are strictly Markovian and have no access to their prior stages, it is impossible to tell from (3) whether the two Johns are copies or just repetitions of John that are to be interpreted independently from each other. It is then necessary to have an operation FormCopy (FC) to make the two Johns copies in (3). FC, an optional operation, selects an element X and searches its domain, i.e., its sister, for a structurally identical element Y. As it identifies Y, it assigns the relation Copy to <X, Y> and Y deletes. When FC identifies two structurally identical elements, it is irrelevant whether one of them was introduced into the structure by Internal Merge or both by External Merge. It should then be able to apply in control structures, as illustrated in (4).

| John tried [ CP [ TP John to win the race]] |

John is externally merged into θ-positions in both embedded and matrix clauses. Then, the operation FormCopy (FC) identifies the two instances of John as copies and the copy in the embedded clause deletes. The analysis is similar on the surface to the old equi NP deletion analysis, but is now formulated as a consequence of the Strong Minimalist Thesis.

This paper aims to develop the Hornstein-Chomsky approach to unify raising and control and to present evidence for the FC analysis. It has been assumed since Chomsky (1981) that raising and obligatory control exhibit different locality requirements. For example, it has been assumed that raising takes place within a phase but control does not because the latter applies across a CP/TP pair. However, the unification of control and raising raises a question on this assumption. In the following section, I briefly go over the analyses of control in terms of movement and FC, and point out that they necessitate a revision in the standard definition of phase and the PIC (Phase Impenetrability Condition). Then, I present the definition suggested in Saito (2017a) and show that it makes the movement/FC analyses of control consistent with the phase theory. The definition is shown in (5).

| a. | C, v(*) are phase heads. |

| b. | T/V inherits phasehood from C/v* along with ϕ-features. |

| c. | PIC: A phase HP becomes inaccessible upon the completion of the next phase up. |

According to (5), T and V with ϕ-features are phase heads and what becomes inaccessible upon the completion of a phase is not its complement but the lower phase. I show that (5) predicts the locality of obligatory control correctly.

Hornstein’s movement and Chomsky’s FC analyses have very similar empirical coverage. They are distinguished by two fundamental hypotheses employed in Chomsky (2021). One is a principle of UG called the Duality of Semantics. Its final formulation is shown in (6).

| Duality of Semantics: for A-positions, EM (External Merge) and EM alone fills a θ-position. |

This prohibits Internal Merge (movement) into θ-positions and hence is inconsistent with the movement analysis of control. The other is a condition on Merge, called Minimal Yield (MY). It reflects the Strong Minimalist Thesis (SMT) and states that Merge, as the simplest structure-building operation, can introduce at most one new accessible item in the Workspace. As shown below, it prohibits sideward movement, which Hornstein employs in the analysis of control into adjuncts and parasitic gaps. Kitahara (2017) presents an empirical argument for MY and hence for FC, showing that it provides a principled account for proper binding effect in English.[1] In Section 3 of this paper, I consider a difference between English and Japanese with respect to the proper binding effect and show that it also follows from MY, coupled with the definition of phase and the PIC in (5). This constitutes additional empirical evidence for MY, and hence, for the FC analysis of control. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 On the definition of phase and the PIC

2.1 The FormCopy (FC) analysis of control and the locality problem

In this section, I first briefly introduce Chomsky’s (2021) FC analysis of control in comparison with Hornstein’s (1999) movement analysis. In particular, I explain the fundamental assumptions behind it that distinguish it from Hornstein’s (1999) analysis. Then, I point out a locality problem that arises with it. The problem is inherited from Hornstein’s analysis and arises because control takes place across a CP/TP pair as illustrated in (2) and (4).

As noted above, Chomsky (2021) entertains two fundamental hypotheses in pursuit of the Strong Minimalist Thesis (SMT). The Duality of Semantics prohibits Internal Merge (movement) into θ-positions and hence directly contradicts the movement analysis of control. The other condition, Minimal Yield (MY), states that Merge can introduce at most one new accessible item in the Workspace (WS). Let us see how MY makes Merge simple and why it is in conflict with the movement analysis of control. Suppose Merge applies to the WS in (7a).

|

There are four items that are accessible in (7a). {a, b} and c are accessible as they are, and a and b become accessible by applying Minimal Search to {a, b}. External Merge can yield (7b) from (7a). In (7b), {a, b}, c, a and b continue to be accessible because Minimal Search into {c, {a, b}} yields them. In addition, the newly constructed item {c, {a, b}} is accessible. Thus, External Merge introduces one new accessible item to the WS. (7c) is constructed when Internal Merge applies to (7a), merging a and {a, b}. Minimal Search into {a, {a, b}} first yields a and {a, b}. At this point, the search of a for accessibility terminates and as a result, a within {a, b} is not accessible. That is, any element in the (c-command) domain of an identical element is inaccessible. Chomsky argues that this is in line with the Strong Minimalist Thesis (SMT) as it makes search computationally efficient. He also points out that there is empirical evidence to support it. His example is shown in (8).

|

The example is severely degraded and is clearly an instance of Comp-trace effect. This indicates that the movement out of the embedded CP must take place from the embedded subject position and not from the embedded object position. This implies that only who in the embedded subject position is accessible for this IM. Given this condition on accessibility, search into {a, b} in (7c) only yields b as an accessible item. Thus, the accessible items in (7c) are a, {a, b}, b, c and the newly constructed {a, {a, b}}. Again, only one new item is accessible compared with (7a).

MY, like the Duality of Semantics, is inconsistent with the movement analysis of control. (1), repeated in (9a), is an example of control into a CP complement.

| a. | John tried [ CP [ TP PRO to win the race]] |

| b. | John left the room [ PP after [ TP PRO talking to Mary]] |

However, control takes place into adjuncts as well, as shown in (9b). In this case, the example cannot be derived by direct movement as in (10) because movement out of an adjunct is illicit.

|

Hornstein (2001) proposes to derive examples of this kind with ‘sideward movement’. According to him, the derivation takes place as in (11).

| a. | Form the adjunct [PP after [TP John talking to Mary]]. |

| b. | Form the v*P of the main sentence [v*P v* [leave the room]]. |

| c. | Merge ‘John’ in the adjunct with the v*P to form [v*P John [v*P v* [leave the room]]]. |

| d. | (Pair) Merge the adjunct to the v*P formed at Step c. |

| e. | Merge T and the v*P formed at Step d to form TP. |

| f. | Internally Merge ‘John’ at Spec, v*P to TP. |

Step c is a case of ‘sideward movement’, which merges an item within α to a separately formed constituent β. And this is one case of the application of Merge that MY excludes.

Let us use the simple WS in (12a) to illustrate the point.

| a. | {{a, b}, {c, d}} |

| … accessible: {a, b}, {c, d}, a, b, c, d |

|

In (12a), {a, b} and c are accessible. If they are merged by sideward movement, the new WS (12b) is produced. It has a new accessible item {c, {a, b}}. In addition, the c within {c, {a, b}} and the c in {c, d} are both accessible as neither is in the (c-command) domain of the other. Thus, sideward movement produces two new accessible items in violation of MY.

The movement analysis of control has many attractive features. But it must be radically reformulated so that it does not involve movement if the Duality of Semantics and MY are maintained. Chomsky’s (2021) FC analysis of control was proposed to achieve this.

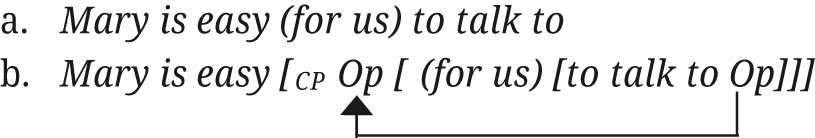

As noted at the outset of this paper, Chomsky’s analysis of control is an extension of his analysis of raising, refined under the SMT. Let us consider (13) as an example of raising and go over this point again.

|

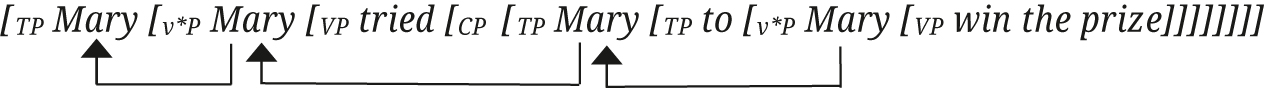

The example is derived by IM (Internal Merge), and Mary in the embedded clause is a copy of Mary in the matrix clause. But if derivations are strictly Markovian and a derived Workspace has no access to the derivational history, this information is not available at the matrix CP phase. What is found in (13) is simply two instances of Mary. Chomsky, then, proposes the operation, FormCopy (FC), to assign the relation Copy to the two Marys. At the matrix phase, MS (Minimal Search) selects Mary in the matrix clause and searches its domain (sister) for an identical element. It finds Mary in the embedded clause and takes the two Marys to be copies. Consequently, the one in the embedded clause deletes.

As FC itself has no access to the derivational history, it should apply to two identical elements regardless of how they were introduced into the structure. In particular, it should apply to two identical elements that are independently merged into the structure by EM. This, Chomsky (2021) points out, explains control. Let us consider (14) to see the point with a concrete example.

| [

CP

[

TP

Mary tried [

CP

[

TP

|

Given the Duality of Semantics, the two Marys must be introduced into their respective clauses by EM. But FC assigns the relation Copy to them and the instance in the embedded clause deletes. This analysis inherits the advantages of Hornstein’s (1999) movement analysis of control without assuming movement into θ-positions. But it also inherits a problem of locality from the movement analysis. The remainder of this section is devoted to the illustration of this problem.

The derivation of (14) under the movement analysis of control is more precisely as in (15).

|

The problematic step is the movement from the embedded Spec, TP to the matrix Spec, v*P. The standard definition of phase and the PIC, as proposed and entertained, for example, in Chomsky (2000, 2008, is as in (16).

| a. | CPs and v*Ps constitute phases. |

| b. | PIC: Once a phase is constructed, its complement is inaccessible to further operation. |

The embedded CP in (15) is a phase. Hence, upon its completion, any element within its complement TP is inaccessible and cannot be moved. The phase theory, thus, predicts that the movement from Spec, TP to Spec, v*P in (15) should be impossible.

The FC analysis faces the same problem as long as FC applies at the phase level as Chomsky (2021) assumes. The structure of the matrix v*P of (14) is as in (17).

|

Mary is merged at the embedded Spec, v*P and at the matrix Spec, v*P by EM. If Mary in the embedded clause merges at Spec, TP by IM, the structure in (17) obtains. FC assigns the relation Copy to the lowest Mary and the middle Mary, and the former deletes. Then, FC should make the middle Mary and the highest Mary copies, and the middle Mary should delete. But this should be impossible because the embedded CP is a phase. When Mary is merged at the matrix Spec, v*P, the middle Mary is already inaccessible as it is contained within the TP complement of the embedded CP phase. The problem arises in the same way even if Mary in the embedded Spec, v*P remains in place and does not internally merge at Spec, TP. It seems then necessary to adopt a definition of phase and the PIC that is different from (16) in order to make the FC analysis work properly. In the following sections, I introduce the definition of phase and the PIC proposed in Saito (2017a) and show that it serves the purpose.

2.2 ϕ-feature agreement and phase

The definition of phase and the PIC in Saito (2017a) was proposed in an attempt to develop Quicoli’s (2008) analysis of binding condition (A) effects in terms of the phase theory. I first illustrate Quicoli’s analysis and then the proposals in Saito (2017a) in this section.

Quicoli assumes, following Chomsky (2000, 2008, that the phase complement is transferred to the CI interface upon the completion of a phase and that this explains the PIC. With this assumption, he proposes (18) to capture condition (A) effects.

| Information on the reference of an anaphor is sent to the CI interface along with a transfer domain that includes the anaphor. |

This makes correct predictions for the examples in (19).

| a. | John nominated himself |

| b. | *John thinks that himself is qualified |

| c. | *John expects Mary to nominate himself |

The reflexive in (19a) is transferred to the CI interface when the v*P phase is formed as in (20).

|

The transfer domain is VP, but as John appears in the structure and c-commands himself, the information ‘himself = John’ can be sent to the CI interface along with the VP. It is thus predicted correctly that (19a) is grammatical.

In (19b), an example of the NIC effect, the reflexive is transferred upon the completion of the embedded CP phase, as illustrated in (21).

|

Here, there is no NP that c-commands himself when the complement TP is transferred. The example is ruled out because the CI interface fails to receive information on the reference of the reflexive. (19c) is an example of the SSC effect. The reflexive is transferred when the embedded v*P phase is formed as in (22).

|

Mary c-commands himself in (22) but does not qualify as its antecedent. In this case too, the information on the reference of himself cannot be sent to the CI interface along with the transfer domain.

Although Quicoli’s proposal has wide empirical coverage, there are a few patterns that it fails to explain. For example, a TP constitutes a binding domain for an anaphor in the subject position when the TP exhibits subject ϕ-feature agreement as in (19b). But as discussed in detail in Chomsky (1981), a TP without subject agreement is not a binding domain for a subject anaphor. Thus, the examples in (23) are grammatical.

|

If CP is always a phase and its complement TP is transferred upon its completion, (18) incorrectly rules out these examples.

The crucial factor that distinguishes (19b) and (23) is not whether the embedded clause has tense but is whether it exhibits agreement. Thus, as Huang (1982) and Yang (1983) showed, tensed embedded clauses pattern with (23) in East Asian languages because those languages lack ϕ-feature agreement altogether. The generalization can be illustrated with the subject-oriented local reflexive zibun-zisin in Japanese. Only the embedded subject Hanako can be the antecedent of zibun-zisin in (24).

| Taroo-wa | [ CP [ TP | Hanako-ga | zibun-zisin-o | suisensu-ru] | to] | omotte i-ru |

| Taroo-TOP | Hanako-NOM | self-self-ACC | nominate-Pres. | C | think-Pres. | |

| ‘Taroo thinks that Hanako will nominate self (= Hanako).’ | ||||||

This shows that zibun-zisin requires a local antecedent. Yet, the examples in (25) with tensed embedded clauses are grammatical just like those in (23).

| Taroo-wa | [ CP [ TP | zibun-zisin-ga | suisens-are-ru] | to] | omotte i-ru |

| Taroo-TOP | self-self-NOM | nominate-Passive-Pres. | C | think-Pres. | |

| ‘Taroo thinks that self (= Taroo) will be nominated.’ | |||||

| Hanako-wa | [ CP [ TP | zibun-zisin-ga | sore-o | mi-ta] | to] | syutyoosi-ta |

| Hanako-TOP | self-self-NOM | it-ACC | see-Past | C | insist-Past | |

| ‘Hanako insisted that self (= Hanako) saw it.’ | ||||||

This confirms that ϕ-feature agreement makes TP a binding domain for subject anaphors.

If the contrast between TPs with and without subject agreement is to be captured by Quicoli’s (2008) phase analysis, the transfer domains for CP phases should be as in (26).

|

The shaded constituent is transferred upon the completion of CP. (26b) is the pattern of (25b), for example. When the embedded CP is formed, the embedded v*P is transferred as in (27a).

|

| b. | [ v*P | Hanako-ga | [[ VP [ CP [[ TP | zibun-zisin-ga [[ v*P …] T [-AGR] ]] C]] | syutyoos] v*]] |

| Hanako-NOM | self-self-NOM | insist |

Then, the matrix v*P is constructed as in (27b). A domain that includes zibun-zisin is transferred at this point. But as Hanako is already in the structure, the information ‘zibun-zisin = Hanako’ can be sent to the CI interface at the same time.

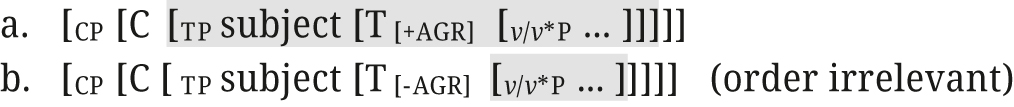

Chomsky (2008) proposes that the phase heads, C and v*, are the locus of uninterpretable ϕ-features (agreement features) and that T and V inherit them from C and v* respectively. Given this, Saito (2017a) proposes the definition of phase and transfer (or simply inaccessible) domain in (28) and shows that it yields (26).[2]

| a. | C, v(*) are phase heads. |

| b. | T/V inherits phasehood from C/v* along with ϕ-features. |

| c. | A phase HP is transferred to the CI interface (or simply becomes inaccessible) upon the completion of the next phase up. |

(28) makes the same predictions as the standard definition for CP phase and v*P phase with ϕ-feature agreement, as illustrated in (29).

|

According to (28b), TP is a phase when T inherits ϕ-features from C. It is then transferred as in (29a) upon the completion of the next phase up, that is, CP. The VP complement of v* is a phase because V inherits phasehood along with ϕ-features from v*. Then, according to (28c), the VP phase is transferred upon the completion of the v*P phase as in (29b).

But (28) makes a different prediction for CP phase without ϕ-feature agreement, as shown in (30).

|

When T does not inherit ϕ-features from C, TP is not a phase. Then, what is transferred when the CP phase is constructed is not the complement TP but the v(*)P complement of T, which is the maximal phase contained within CP. This is precisely what is illustrated in (26b), repeated below as (31).

|

Thus, the English examples in (23) and the Japanese examples in (26) are accounted for.

(28) predicts a difference between English and Japanese with respect to anaphor binding at the v*P phase as well. V inherits ϕ-features as well as phasehood from v* and becomes a phase head in English. Then, the VP complement is transferred upon the completion of a v*P phase. In Japanese, on the other hand, the VP complement of v*P is not a phase as there is no ϕ-feature agreement and no feature inheritance in the language. It is then predicted that anaphor binding in causative sentences with small clause v*P complements exhibit different patterns in the two languages. I show that this prediction is borne out in the remainder of this section.

Let us consider first the English example in (32).

| *Mary made John nominate herself |

If the clausal complement of (32) is a small clause as Stowell (1981) argues, then its structure is as in (33).

| [ v*P John [ VP nominate herself]] |

The ungrammaticality of (32) straightforwardly follows. As V inherits ϕ-features from v*, VP becomes a phase. It is transferred when v*P is completed, but the information on the reference of herself is missing at this point.

Japanese causative sentences look like simple sentences on the surface, but it has been widely assumed since Kuroda (1965) that they involve clausal embedding. The best-known evidence for this is that the long-distance subject-oriented reflexive zibun can take the causee as well as the causer as its antecedent. The dative argument in a ditransitive sentence, not being a subject, does not qualify as the antecedent of zibun, as shown in (34a).

| Hanako-ga | Taroo-ni | zibun-no | syasin-o | okut-ta |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-DAT | self-GEN | picture-ACC | send-Past |

| ‘Hanako sent her picture to Taroo.’ (zibun = Hanako) | ||||

| Hanako-ga | Taroo-ni | zibun-no | syasin-o | sute-sase-ta |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-DAT | self-GEN | picture-ACC | discard-make-Past |

| ‘Hanako made Taroo discard her/his picture.’ (zibun = Hanako or Taroo) | ||||

(34b), on the other hand, shows that the dative causee argument in a causative sentence can be the antecedent of zibun. Taroo in this example, then, must be the subject of the embedded clause. Murasigi and Hashimoto (2004) argue further that Japanese causative sentences have precisely the same structure as their English counterparts with embedded v(*)P small clauses. According to this analysis, Taroo in (34b) qualifies as a subject because it is located in the Spec position of the embedded v*P.

Interestingly, (34b) remains ambiguous even when the local reflexive zibun-zisin is substituted for zibun. Kato (2016) observes contrasts like (35) and shows that the embedded clause is normally the binding domain for a local anaphor in the embedded object position but not in causative sentences.

| Hanako-ga [ CP | Taroo-ga | zibun-zisin-o | suisensi-ta | to] | omotte i-ru | (koto) | |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-NOM | self-self-ACC | nominate-Past | C | think-Pres. | fact | |

| ‘Hanako thinks that Taroo nominated himselfself.’ (zibun-zisin = Taroo) | |||||||

| Hanako-ga | Taroo-ni | zibun-zisin-o | suisens-ase-ta | (koto) |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-DAT | self-self-ACC | nominate-make-Past | fact |

| ‘Hanako made Taroo nominate him/herself.’ (zibun-zisin = Hanako or Taroo) | ||||

As zibun-zisin is a local anaphor, it must take the embedded subject Taroo as its antecedent in (35a). But in the causative sentence (35b), the matrix subject Hanako as well as the embedded subject Taroo qualify as the antecedent of zibun-zisin. Kato’s generalization is confirmed with another local anaphor otagai ‘each other’ in (36).

| *Karera-ga [ CP | Hanako-ga | otagai-o | suisensi-ta | to] |

| they-NOM | Hanako-NOM | each.other-ACC | nominate-Past | C |

| omotte i-ru | (koto) | |||||

| think-Pres. | fact | |||||

| ‘Lit. They think that Hanako nominated each other.’ | ||||||

| Karera-ga | Hanako-ni | otagai-o | suisens-ase-ta | (koto) |

| they-NOM | Hanako-DAT | each.other-ACC | nominate-make-Past | fact |

| ‘Lit. They made Hanako nominate each other.’ | ||||

In (34b), otagai in the embedded object position can take the matrix subject as its antecedent. Thus, there is a difference between English and Japanese causative sentences with respect to the binding domain of an anaphor in the embedded object position.

This difference between English and Japanese causatives is precisely what (28) predicts. (32) is repeated in (37a) with the structure of its v*P complement in (37b).

| *Mary made John nominate herself |

| [ v*P John [ VP nominate herself]] |

As explained above, the VP in (37b) is a phase because V inherits phasehood along with ϕ-features from v*. When (37b) is formed, VP, which is the lower phase, is transferred without information on the reference of herself. The situation is different in Japanese because the language lacks ϕ-feature agreement. The structures of the embedded v*P and the matrix v*P of (35b) are shown in (38a) and (38b) respectively.

| [ v*P | Taroo-ni | [ VP | zibun-zisin-o | suisens]] |

| Taroo-DAT | self-self-ACC | nominate |

| [ v*P | Hanako-ga | [ VP [ v*P | Taroo-ni | [ VP | zibun-zisin-o | suisens]]-(s)ase]] |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-DAT | self-self-ACC | nominate-cause |

VP is not a phase in (38a) as V does not inherit ϕ-features from v*. Hence, nothing is transferred at this point. When (38b) is formed, the lower v*P phase, which includes zibun-zisin, is transferred. But as Hanako is already in the structure, the information ‘zibun-zisin = Hanako’ can be sent to the CI interface along with the v*P. Thus, (28) predicts the contrast between the English (37a) and the Japanese (35b).[3]

2.3 The locality of obligatory control

Whether the locality of anaphor binding should be explained by the phase theory is still controversial. But (28) also serves to make the movement analysis of control consistent with the phase theory, as discussed in detail in Saito (2017b). Let us consider (15) again, repeated in (39), to see how this is achieved.

|

The problem was the second step. Suppose that the complement TP becomes inaccessible when a CP is formed, as is implied by the standard definition of phase. Then, Mary in the specifier position of the embedded TP in (39) becomes inaccessible upon the completion of the embedded CP, and cannot move to a position in the matrix clause. On the other hand, the definition of phase and transfer domains in (28) allows this movement. Since the embedded T does not inherit ϕ-features from the embedded C, the embedded TP is not a phase. Then, what becomes inaccessible upon the completion of the embedded CP is not the complement TP but the embedded v*P. Mary remains accessible and can move to the specifier position of the matrix v*P.

(28) makes the phase theory consistent with the FC analysis of control in the same way. Let us go over the problem first. The relevant structure in (17) is repeated in (40).

|

Mary is externally merged at the specifier positions of the embedded v*P and the matrix v*P because of the Duality of Semantics. Mary in the embedded clause merges with the embedded TP by IM. At the embedded CP phase, FC assigns the relation Copy to the two Marys in the embedded clause and the lower copy deletes. Then, at the matrix v*P phase, FC should assign the relation Copy to the highest Mary and the middle Mary, and the latter should delete. But if the complement TP becomes inaccessible upon the completion of a CP phase, the middle Mary should be inaccessible to FC. This problem does not arise if (28) is assumed. In (40), the embedded TP is not a phase as T does not inherit ϕ-features from C. Then, what becomes inaccessible upon the completion of the embedded CP is not this TP but the embedded v*P. The middle Mary in (40) remains accessible at the matrix v*P phase, and FC can successfully apply.

(28) not only allows the derivation in (40) but accounts for the locality of obligatory control generally. For example, it rules out the following derivations:

| a. | Mary thinks [ CP that [ TP John [ v*P tried [ CP [ TP Mary to be elected]]]]] |

| b. | Mary wants (very much) [ CP for [ TP John to [ vP be proud Mary]]] |

FC cannot apply to the two Marys in (41a) because the most deeply embedded CP becomes inaccessible upon the completion of the v*P of the middle clause. For (41b), it is crucial that vP, in addition to v*P, is a phase. The vP of the embedded clause becomes inaccessible when the embedded CP is formed. Thus, the two Marys fail to have the Copy relation.

In this section, I pointed out a locality problem with Hornstein’s (1999) movement and Chomsky’s (2021) FC analyses of control and argued that the problem can be overcome by a revision in the definition of phase and the formulation of the PIC. I suggested that (28), which is motivated on independent grounds, serves the purpose and hence, can be considered a candidate for the revision.[4]

3 Evidence for Minimal Yield and hence for Form Copy

The FC analysis of control presupposes the Duality of Semantics and Minimal Yield (MY) and in this sense, is quite different from the movement analysis. Yet, the two analyses have similar empirical coverage. This is not surprising because the FC analysis follows the movement analysis in unifying raising and control. Hornstein argued that both raising and control involve movement. Chomsky, on the other hand, proposed that FC applies to both raising and control structures. Both movement and FC are phase-level operations. In this section, I discuss the similarities and differences between the two analyses in the empirical domain in more detail. In 3.1, I briefly go over how the two approaches deal with different types of control constructions and other phenomena like parasitic gaps. In 3.2, I turn to a difference between the two approaches. I introduce Kitahara’s (2017) analysis of the proper binding effect in terms of MY and present further evidence for it, showing that it also explains an interesting difference between English and Japanese with respect to proper binding. As FC is based on MY and the movement analysis of control is inconsistent with it, the evidence for MY shows that the FC approach is indeed an improvement over the movement approach on empirical grounds as well.

3.1 Control into adjuncts and related phenomena

It was illustrated in Section 2 how the movement analysis accounts for examples of control into adjuncts with sideward movement. The FC analysis straightforwardly accounts for them as well without assuming any ‘sideward relation’. FC only applies to two items in c-command relation. The two approaches also successfully explain some cases that resist analysis in terms of PRO. Let me illustrate the point first with the examples of depictive secondary predicates in (42).

| a. | John ate the meat naked |

| b. | John ate the meat raw |

In (42a), for example, John is an argument of naked as well as eat. In this case, a PRO cannot be postulated in the projection of naked if the distribution of PRO is limited to the subject position of a nonfinite TP.[5] On the other hand, the example can be straightforwardly analyzed with FC, as illustrated in (43).

|

John is externally merged in θ-positions in the main clause and in the secondary predicate (John 2 and John 3 ). John 2 internally merges at Spec, TP and then, FC applies to John 1 and John 2 as well as to John 1 and John 3 , deleting John 2 and John 3 . The movement analysis can also account for the example with sideward movement of John from the position of John 3 to the position of John 2 .

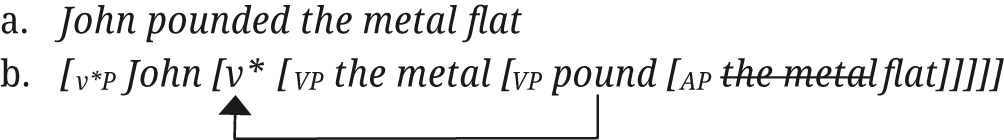

The analysis can be extended to resultative small clauses like (44a) although they are not adjuncts.

|

Let us assume that the v*P of the example has the structure in (44b).[6] The noun phrase the metal is externally merged at the object position and also within the resultative small clause. FC assigns the relation Copy to the two instances and the copy in the small clause deletes, as in depictive small clauses. In this case, the movement analysis need not appeal to sideward movement. If movement into θ-position is allowed, the metal in the AP can move to the object position of the main clause and pick up the internal θ-role of pound.[7]

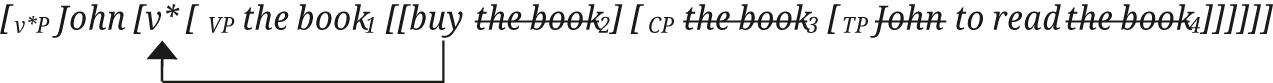

As Chomsky (2021) mentions, FC makes a principled account for parasitic gaps possible. For example, (45a) can be analyzed as in (45b).

| a. | Which paper did John file after he read |

| b. | which paper

1

[did John [file |

The wh-phrase externally merges with file (which paper2) and moves to the matrix Spec, CP (which paper1). It also externally merges with read (which paper4) and moves to Spec, CP within the adjunct (which paper3). FC applies in the usual manner, and which paper2 and which paper4 delete. In addition, it can apply to which paper1 and which paper3 as they belong to the same phase domain. Then, which paper3 deletes. The structure obtained is as if the wh-phrase moved to the matrix Spec, CP from two θ-positions although movement out of an adjunct does not actually take place.[8] Hornstein (2001), building on Nunes (1995), appeals to sideward movement for the analysis of parasitic gaps. The basic idea is that which paper in (45) moves from the position of which paper 3 to the position of which paper 2 to pick up the internal θ-role of file.

The sideward movement analysis of (45) implies that movement from an A’-position to an A-position is possible. This sort of movement is widely assumed to be illicit because the derivation of (46a) in (46b) is ruled out.

|

The illicit movement in (46b) is called improper movement. Hornstein (2001) argues that movement from an A’-position to an A-position is allowed and that examples of improper movement are ruled out on independent grounds. One possibility is to exclude them as Condition (C) violations, as originally proposed by May (1981). It is possible that John 3 is subject to Condition (C) because it internally merges at an A’ position. It is also possible that John 2 is absent at the level Condition (C) applies as it plays no role in interpretation. Then, John 3 is locally A-bound by John 1 at that level in violation of Condition (C).[9]

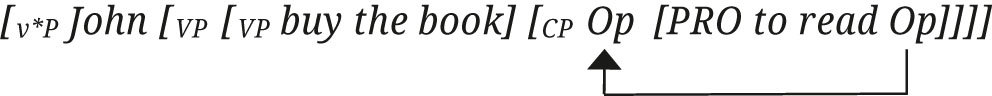

On the premise that A’-to-A movement is possible, Hornstein proposes further that null operators can be eliminated. Let us consider first the purpose expressions in (47).

| a. | John bought the book to please Mary |

| b. | John bought the book to read |

(47a) is a straightforward example of control. It can be derived as in (48), or by sideward movement if the movement in (48) is ruled out as it involves extraction out of an adjunct.

|

The standard analysis of (47b), on the other hand, is with a null operator movement as in (49).

|

Hornstein proposes to analyze the example without a null operator by moving the book from the object position of read to Spec, CP of the purpose clause, and then, to the object position of buy. As (50) illustrates, the last step is sideward movement.

|

Hornstein extends this analysis to other kinds of examples that have been analyzed with null operator movement. For example, (51a), which is standardly analyzed as in (51b), can be derived instead as in (52).[10]

|

|

(52) contrasts with (46a) and is not in violation of Condition (C). This is because the copy of Mary in Spec, CP serves a role in interpretation, mediating the relation between the other two Marys in A-positions. Although it is deleted phonetically, it is retained in Spec, CP and protects the most deeply embedded copy of Mary from being locally A-bound by the copy in Spec, AP. According to Hornstein, this is what a null operator is.

Chomsky (2021) pursues a different direction so that improper movement is excluded as a failure of FC to apply. He proposes (53).

| From an A-position, FC searches A-positions. |

Let us consider (46), repeated in (54), to see how this works.

| a. | *John seems that it is likely to submit a paper |

| b. | [

TP

John

1

[seems [

CP

|

FC searches John 1 ’s sister, which is the matrix TP excluding John 1 . But since it searches only A-positions, it fails to identify John 2 as a potential copy of John 1 . Consequently, FC does not assign the relation Copy to John 1 and John 2 , and the former fails to be connected to a θ-position.

Thus, Hornstein maintains that A’-to-A movement is allowed whereas Chomsky excludes the corresponding copy relation with (53).[11] But as far as I can see, this difference is not rooted in the difference in their approaches to control. For example, one can maintain the FC approach, and at the same time, abandon (53) on the assumption that improper movement is ruled out on independent grounds. In that case, (47b) can be analyzed as in (55).

|

The book in the purpose clause internally merges at Spec, CP (the book 3 ). On the other hand, the book in the main clause internally merges at Spec, VP (the book 1 ) so that VP can be properly labeled, as proposed in Chomsky (2015). FC applies to the book 1 and the book 3 , and the latter deletes. Similarly, (51a) can be accounted for as in (56).

|

Mary is externally merged as the complement of to (Mary 3 ) and as the specifier of the matrix vP (Mary 1 ).[12] The former internally merges at Spec, CP (Mary 2 ). FC applies to Mary 1 and Mary 2 , and the latter deletes. Mary 2 is retained in interpretation so that Mary 1 and Mary 3 can be θ-related through its mediation. Then, Mary 3 does not violate Condition (C) because it is not locally A-bound.

Thus, the FC approach and the movement approach have very similar empirical coverage. However, Kitahara (2017) presents evidence for MY, and this serves to distinguish the two approaches on empirical grounds. This is so because the FC analysis is based on MY whereas MY excludes sideward movement, which is an important part of the movement analysis of control. I turn to his argument in the following subsection.

3.2 Proper binding effects in English and Japanese

There is an asymmetry between A’-movement and A-movement with respect to the proper binding effect. This is illustrated in (57).

| a. | *[ CP [Which picture of _ ] does [ TP John [ vP wonder [ CP who [ TP Mary [ vP likes _ ]]]]]] |

| b. | I wonder [ CP [how likely _ to win] [ TP John is _ ]] |

In (57a), first, who internally merges at the Spec of embedded CP, an A’-position. Then the remnant wh-phrase, which picture of, is internally merged at the Spec of matrix CP. The wh-phrase, who, does not c-command its initial site, and the example is ungrammatical. In (57b), the initial movement is IM of John at the embedded subject position, an A-position. Then, the remnant wh-phrase, how likely to win, is internally merged at Spec, CP. The example is grammatical despite the fact that John does not c-command its initial site.

Kitahara (2017) shows that the contrast in (57) follows from the predecessor of MY, Determinacy, that Chomsky proposed in his 2017 Reading Lecture. In this subsection, I first outline his argument. I assume MY instead of Determinacy because Kitahara’s analysis holds with either of them. Then, I introduce an observation by Hoji et al. (1989) that the Japanese counterpart of (57b) is ungrammatical. I show, extending Kitahara’s analysis, that this fact also follows from MY with the definition of phase and the PIC argued for in Section 2.

Recall that MY states that Merge can introduce at most one new accessible item in the Workspace (WS). Kitahara points out that in the derivation of (57a), who must move out of which picture of who, and then, the remnant, which picture of, must move to a position higher than who at one stage of the derivation. If this happens at the edge of the embedded v*P, the two steps produce the structures in (58a) and (58b) respectively.

|

The IM of (58a) satisfies MY. The internally merged who 1 is accessible. But who 2 no longer is because it is c-commanded by who 1 . Thus, the only newly accessible item is the whole v*P produced by the IM. On the other hand, (58b) is in violation of MY. The internally merged which picture of who is accessible, and its copy at the initial site no longer is.[13] But who 3 and who 1 are both accessible because neither c-commands the other. This adds an accessible item because only one instance of who is accessible in (58a). Hence, the application of IM in (58b) adds two new accessible items, who 3 and the v*P it produces. (57a), then, is correctly ruled out by MY.

Kitahara, then, shows that the situation is different in the case of (57b). The IM of the subject and the subsequent IM of the wh-phrase produce the structures in (59a) and (59b) respectively.

|

(59a) is straightforward. John 1 is accessible but John 2 is not because it is c-commanded by John 1 . So, the new accessible item is just the TP produced by the IM. (59b), like (58b), is produced by the internal merge of a remnant wh-phrase at Spec, CP. John 3 and John 1 both appear to be accessible because neither c-commads the other. And if they are, (59b) is in violation of MY. But there is a crucial difference between (58b) and (59b). In (59b), John 1 is not at the phase edge. The internal merge at Spec, CP completes the CP phase. Then, the IM makes the complement TP inaccessible because of the PIC. As a result, there is only one instance of John that is accessible in (59b). Thus, the IM produces only one newly accessible item, that is, the CP that it forms. The IM in (59b), in contrast with the IM in (58b), conforms to MY.

With Kitahara’s (2017) analysis, the contrast in (57) constitutes solid evidence for MY. Further evidence for his analysis and MY can be obtained from examples of the proper binding effect in Japanese. The crucial data are observed in Hoji et al. (1989). Let us first consider data that are standardly discussed as examples of proper binding effect.[14] As is well known, Japanese allows scrambling rather freely as shown in (60).

| [ TP | Hanako-ga | [ VP | Taroo-o | nagiri]-sae | si-ta] |

| Hanako-NOM | Taroo-ACC | punch-even | do-Past | ||

| ‘Hanako even punched Taroo.’ | |||||

| [Taroo-o [ TP Hanako-ga [ VP _ nagiri]-sae si-ta]] |

| [[ VP Taroo-o naguri]-sae [ TP Hanako-ga _ si-ta]] |

In (60b), the object Taroo-o is scrambled to the sentence-initial position. A VP can also be scrambled when it appears with a focus particle as in (60a). This is shown in (60c). Japanese also allows multiple scrambling. Thus, (61a) is grammatical.

| [Taroo-o | (kinoo) | [[ VP _ | nagiri]-sae | [ TP | Hanako-ga | _ si-ta]]] |

| Taroo-ACC | yesterday | punch-even | Hanako-NOM | do-Past | ||

| ‘Lit. Taroo, (yesterday), even punch, Hanako did.’ | ||||||

| *[[ VP | _ nagiri]-sae | [Taroo-o | [ TP | Hanako-ga | _ si-ta]]] |

| punch-even | Taroo-ACC | Hanako-NOM | do-Past | ||

| ‘Lit. Even punch, Taroo, Hanako did.’ | |||||

However, (61b) shows that the sentence is totally ungrammatical when the scrambled VP precedes the scrambled object. This is standardly considered a proper binding effect as the scrambled object fails to c-command its initial site, that is, the object position of naguri ‘punch’ in the scrambled VP.

(61b) poses a question for Kitahara’s analysis introduced above. It is argued in Saito (1985) that any maximal projection can be a landing site of scrambling. Then, (62) should be a possible structure for (61b).

|

In (62), Taroo-o internally merges with TP and the VP, Taroo-o naguri-sae, internally merges with CP. If the PIC makes the TP complement inaccessible upon the completion of a CP phase, Taroo-o 1 is inaccessible. Then, the IM of VP to CP only produces one new accessible item, the newly formed CP, and hence, conforms to MY, just like (59b).

The problem can be seen more clearly with the observation of Hoji et al. (1989) mentioned above. They point out that VP scrambling is illicit when the verb is unaccusative or passive. (63b) is perfectly fine as the verb is unergative.

| [ TP | Hanako-ga | [ VP | hasiri-mawari]-sae | si-ta] |

| Hanako-NOM | run.around-even | do-Past | ||

| ‘Hanako even ran around.’ | ||||

| [ VP Hasiri-mawari]-sae [ TP Hanako-ga _ si-ta] |

On the other hand, unaccusative and passive verbs do not allow VP-scrambling, as shown in (64) and (65).

| [ TP | Ame-ga | [ VP | _ huri]-sae | si-ta] |

| rain-NOM | fall-even | do-Past | ||

| ‘It even rained.’ | ||||

| *[ VP _ huri]-sae [ TP ame-ga _ si-ta] |

| [ TP | Hanabi-ga | [ VP | _ uti-age-rare]-sae | si-ta] |

| firework-NOM | shoot.off-Passive-even | do-Past | ||

| ‘Even fireworks were shot off.’ | ||||

| *[ VP _ uti-age-rare]-sae [ TP hanabi-ga _ si-ta] |

Hoji et al. (1989) present (64b) and (65b) as examples of the proper binding effect. In (64b), for example, ame ‘rain’ fails to c-command its initial site within the scrambled VP. Their conclusion is that these examples constitute evidence for NP-movement in Japanese. Their point is well taken. But the examples pose a mystery as well. As seen in (57b), repeated below as (66), A’-movement can be applied to a remnant of NP-movement.

| I wonder [ CP [how likely _ to win] [ TP John is _ ]] |

(67a) and (67b) correspond more closely to (64b) and (65b) respectively.

| They said that the ball might fall _ into the ditch, and |

| fall _ into the ditch, it did _ . |

| Mary said that she would be praised _ by the critics, and |

| praised _ by the critics, she was _ . |

In the second clause of (67a), for example, it moves from the complement position of fall to the subject position as the verb fall is unaccusative. Then the VP headed by fall is preposed to the sentence-initial position. The example parallels (64a) but is grammatical. What would be the reason for this difference between English and Japanese? This has been a puzzle especially since Müller (1996) discussed and confirmed the asymmetry between A’-movement and A-movement in (57).

The ungrammaticality of (64b) and (65b) poses the same problem as (61b) with the standard definition of phase and the PIC. (64b) can be derived as in (68).

|

There is no c-command relation between ame-ga 3 and ame-ga 1 . So, the IM of VP appears to produce more than one new accessible item. But the derivation should be allowed because the TP and hence ame-ga 1 are inaccessible because of the PIC. It is then predicted incorrectly that (64b) is grammatical.

However, if the definition of phase and the PIC proposed in the preceding section is assumed, MY properly explains the contrast between the Japanese (64b)/(65b) and the English (66)/(67). The definition in (28) is repeated below in (69).

| a. | C, v(*) are phase heads. |

| b. | T/V inherits phasehood from C/v* along with ϕ-features. |

| c. | A phase HP is transferred to the CI interface (or simply becomes inaccessible) upon the completion of the next phase up. |

It does not affect Kitahara’s (2017) analysis of the English examples. For example, the derivation of the second clause of (67a) can be as in (70).

|

In (70), TP is a phase in addition to CP as T inherits phasehood as well as ϕ-features from C. Then, TP becomes inaccessible upon the completion of CP. As a result, only one instance of it is accessible and the IM of VP conforms to MY.

On the other hand, MY predicts the Japanese (64b) and (65b) to be ungrammatical. Let us take (64b) again to illustrate this. The derivation of the example is shown again in (71).

|

According to (69), the TP in this example is not a phase. As Japanese lacks ϕ-feature agreement altogether, T does not inherit ϕ-features and phasehood from C. Then, what the PIC makes inaccessible upon the completion of CP is not TP but vP, as indicated in (71). Consequently, the IM of VP in (71) produces two newly accessible items, ame-ga 3 and the CP that IM forms. The example is thus correctly ruled out by MY. The ungrammaticality of (61b), repeated in (72), is explained in the same way.

| *[[ VP | _ nagiri]-sae | [Taroo-o | [ TP | Hanako-ga | _ si-ta]]] |

| punch-even | Taroo-ACC | Hanako-NOM | do-Past | ||

| ‘Lit. Even punch, Taroo, Hanako did.’ | |||||

|

As indicated in (73), what the PIC makes inaccessible upon the completion of CP is not TP but v*P. Hence, the IM of VP produces two newly accessible items, Taroo-o 3 and the CP formed by the IM.

It was shown in this section that Kitahara’s (2017) analysis of the proper binding effect in terms of MY extends to Japanese examples that have been problematic over the years. This provides further support for his analysis and for MY.

4 Conclusions

Chomsky’s (2021) FormCopy (FC) analysis of control develops Hornstein’s (1999) movement analysis. In this paper, I first briefly explained these analyses and pointed out that the FC analysis inherits a problem with locality from the movement analysis. In particular, the FC analysis, like the movement analysis, contradicts the standard definition of phase and the PIC. Then, I showed that the revision in the definition of phase and the PIC proposed in Saito (2017a) serves to make both analyses consistent with the phase theory. Secondly, I discussed the empirical coverage of the FC analysis in comparison with the movement analysis. I showed that they are expected to have similar coverage and they in fact do. Then, I introduced Kitahara’s (2017) analysis of the proper binding effect in terms of Minimal Yield (MY) and presented supporting evidence for it. I argued that MY not only explains the proper binding effect in English, as Kitahara showed, but also explains the effect in Japanese, which exhibits different patterns from English. As MY forms a basis for the FC analysis and is inconsistent with the movement analysis, this shows that the FC analysis is an improvement over the movement analysis on empirical grounds as well.

References

Bošković, Željko. 2016. What is sent to spell-out is phases, not phase complements. Linguistica 56. 25–66. https://doi.org/10.4312/linguistica.56.1.25-66.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries. In Roger Martin, David Michaels & Juan Uriagereka (eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, 89–155. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero & Maria Luisa Zubizarreta (eds.), Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, 291–321. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262062787.003.0007Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamannand & Simona Matteini (eds.), Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, 3–16. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.223.01choSearch in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2021. Minimalism: Where are we now, and where can we hope to go. Gengo Kenkyu 160. 1–41.Search in Google Scholar

Hayashi, Norimasa. 2021. Deducing parasitic gaps from Form Copy. Kyushu University Unpublished manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Hoji, Hajime, Shigeru Miyagawa & Hiroaiki Tada. 1989. NP-movement in Japanese. Paper presented at WCCFL 8, University of British Columbia, 24–26 February.Search in Google Scholar

Hornstein, Norbert. 1999. Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry 30. 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438999553968.Search in Google Scholar

Hornstein, Norbert. 2001. Move! A minimalist theory of construal. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Hornstein, Norbert & David Lightfoot. 1987. Predication and PRO. Language 63. 23–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/415383.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kato, Shizuka. 2016. Condition (A) and complex predicates. Nanzan Linguistics 11. 15–34.Search in Google Scholar

Kitahara, Hisatsugu. 2017. Some consequences of MERGE + 3rd factor principles. Keio University Unpublished manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Kuroda, Sige-Yuki. 1965. Causative forms in Japanese. Foundations of Language 1. 30–50.10.7312/morr90852-012Search in Google Scholar

Legate, Julie Anne. 2003. Some interface properties of the phase. Linguistic Inquiry 34. 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2003.34.3.506.Search in Google Scholar

May, Robert. 1981. Movement and binding. Linguistic Inquiry 12. 215–243.Search in Google Scholar

Müller, Gereon. 1996. A constraint on remnant movement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 14. 355–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00133687.Search in Google Scholar

Murasigi, Keiko & Tomoko Hashimoto. 2004. Three pieces of acquisition evidence for the v-VP frame. Nanzan Linguistics 1. 1–19.Search in Google Scholar

Nunes, Jairo. 1995. The copy theory of movement and linearization of chains in the minimalist program. College Park, Md.: University of Maryland dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Quicoli, A. Carlos. 2008. Anaphora by phase. Syntax 11. 299–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2008.00116.x.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 1985. Some asymmetries in Japanese and their theoretical implications. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 2001. Movement and θ-roles: A case study with resultatives. In Yukio Otsu (ed.), The proceedings of the second Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, 35–60. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 2017a. A note on transfer domains. Nanzan Linguistics 12. 61–69.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 2017b. Notes on the locality of anaphor binding and A-movement. English Linguistics 34. 1–33. https://doi.org/10.9793/elsj.34.1_1.Search in Google Scholar

Stowell, Timothy A. 1981. Origins of phrase structure. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Takita, Kensuke. 2010. Cyclic linearization and constraints on movement and ellipsis. Nagoya, Japan: Nanzan University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Dong-Whee. 1983. The extended binding theory of anaphors. Language Research 19. 169–192.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: workspace, MERGE and labelling

- Articles

- On wh and subject positions, the EPP, and contextuality of syntax

- On Minimal Yield and Form Copy: evidence from East Asian languages

- A multi-dimensional derivation model under the free-MERGE system: labor division between syntax and the C-I interface

- Seeking an optimal design of Search and Merge: its consequences and challenges

- Large-scale pied-piping in the labeling theory and conditions on weak heads

- The third way: object reordering as ambiguous labeling resolution

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: workspace, MERGE and labelling

- Articles

- On wh and subject positions, the EPP, and contextuality of syntax

- On Minimal Yield and Form Copy: evidence from East Asian languages

- A multi-dimensional derivation model under the free-MERGE system: labor division between syntax and the C-I interface

- Seeking an optimal design of Search and Merge: its consequences and challenges

- Large-scale pied-piping in the labeling theory and conditions on weak heads

- The third way: object reordering as ambiguous labeling resolution