Abstract

The paper argues for a bisentential, paratactic account of Hanging Topic Left Dislocations wherein the syntactically unconnected hanging topic phrase is the remnant of an elliptical copulative sentence which is linearly juxtaposed to the second, host sentence. This proposal represents a natural extension of Ott’s system for Clitic Left Dislocations and predicative non-restrictive nominal appositives. By assuming that the hanging topic is structurally disconnected from the host sentence, the analysis constitutes a radical departure from integrated/monosentential approaches within cartography, which analyze hanging topics as intrasentential, albeit peripheral, constituents in the left spine of the clause. Using data from English and Spanish as well as from other linguistic varieties, the paratactic approach provides a principled account of various issues facing monosentential analyses of hanging topics, including anti-connectivity, coreference with the resumptive/epithetic correlate, comma intonation/pause potential, case, insensitivity to locality constraints, islandhood, and potential presence of interjections between hanging topic and host sentence, amongst others. The account is also successful in capturing orphaned topics, which are not linked to any constituent in the sentence they occur with, alongside ‘interrogative’ and hyperdetached hanging topics.

Reviewed Publications:

Well, I know, after all, it is only juxtaposition, Juxtaposition, in short; and what is juxtaposition?

–Arthur Hugh Clough, English poet (1819–1861)

1 Introduction

Left dislocations came into focus in the generative tradition with the seminal work of Ross (1967). Since then, the literature has distinguished two major types of dislocations in the natural languages.[1] The first type, with which this paper concerns itself, is hanging topics (HTs), also known as the Hanging Topic Left Dislocation (HTLD) construction, illustrated for English and Spanish in (1):[2]

| Him acc and a couple of mates, they went to a casino at 4 in the morning. |

| (Tim Vickery, BBC Radio 5, cited in Radford [2018: 51]) |

| Star Wars, yeah, that was my first big mistake. |

| (Attributed to Al Pacino) |

| Yo, | las | playas | de | Canarias | me | encantan. |

| Inom | the | beaches | of | Canary-islands | cldat | charm |

| ‘As for me, I love the beaches of the Canary Islands.’ | ||||||

| (Spontaneous speech, Spain, February 2022) | ||||||

| Esta | mujer, | me | suena | su | cara. |

| this | woman | cldat | sounds | her | face |

| ‘This woman, her face looks familiar to me.’ | |||||

| (Carta a Eva, miniseries, Spanish Radio & Television Corporation, RTVE, 2013) | |||||

Prescriptively, and despite their high frequency in speech, HTs tend to be frowned upon (RAE-ASALE [2009: 2978]; see also Radford [2018]).

The second type is the topicalization construction (cf. (2)a, b), whose closest Romance counterpart is the Clitic Left Dislocation (ClLD) construction, illustrated below for Spanish (cf. (2)c) and Catalan (cf. (2)d).

| That promise of lifelong service I renew to all today. |

| (King Charles III, 9 September 2022) |

| I wanted to utter a word, but that word, I cannot remember. |

| (Mandelstam, Russian poet; translation cited in Aitchison [2012: 13]) |

| A | mi | prima | no | la | soporta | nadie. |

| clacc | my | cousinfem | not | clacc | bears | nobody |

| ‘Nobody can stand my cousin.’ | ||||||

| De | l’examen | ningú | no | n’ha | parlat | encara. | |

| of | the+exam | nobody | not | clpartitive+has | talked | yet | |

| ‘Nobody has talked about the exam yet.’ | |||||||

| (Catalan, from Casielles-Suárez [2004: 333]) | |||||||

Much research has been devoted to the Romance ClLD construction in (2)c, d, whereas HTLDs, exemplified in (1), have received much less attention in the recent syntactic literature within the transformational generative framework (though see the collection of papers in Anagnostopoulou et al. 1997).

Regarding the interpretation of dislocates such as HTLDs, van Riemsdijk (1997: 4) notes that “in the most general terms, the clause ‘is about’ the left dislocated phrase.” I will return to this issue briefly in due course. With respect to their derivation, pragmatics-oriented works have championed extra-sentential proposals, whereas syntax/cartography-oriented works have assumed HTs to be intra-sentential, though left-peripheral, constituents. As part of his discussion of previous syntactic accounts, Radford (2018: Ch. 2) refers to HTLDs as R(esumptive)-linked topics and to cases of topicalization as G(ap)-linked topics, since the former are typically linked to a resumptive pronoun (in the broad sense, as we will see), as in (1)a, b and the latter to a gap, as in (2)a, b. One of the major questions regarding the syntactic analysis of such constructions in the last decades, especially considering the by-now longstanding move-versus-merge debate within the generative tradition, has been whether they are deployed by means of movement (in more recent terms, internal merge or re-merge) or by base generation (external, direct merge) in the left position of the clause where they surface. Focusing on HTLDs (cf. (1)), there is ample consensus that such constructions do not undergo movement to the front of the sentence and are instead inserted directly in their superficial position on the left of their clause (see Radford [2018: Ch. 2] and references therein), though movement accounts have been put forward for HTLDs (see, e.g., Contreras [1976] and Boeckx and Grohmann [2005]).

My proposal aligns more with the first, non-movement line of analysis, but it radically departs from both types of syntactic analysis (i.e., base-generation/movement), most of which are couched in cartography (Rizzi 1997 et seq.). A crucial assumption of the two kinds of syntactic account is that the HT is a host-sentence-internal constituent. By contrast, the analysis pursued herein assumes two (root) sentences which establish a paratactic relation with one another: the first one is elliptical (CP1), with the HTLDed phrase being a fragment/remnant of ellipsis, and the second one is the host sentence (CP2), a syntactically complete sentence that is linearly juxtaposed to the first, elliptical one, as shown schematically in (3) for example (1)a above:

| [CP1

|

| [ CP2 they k went to a casino at 4 in the morning ] |

On this sentential-juxtaposition-cum-ellipsis kind of analysis, therefore, HTs are not just external, but extra-sentential constituents, in the spirit of the work of a number of authors of diverse theoretical persuasions, such as Dik (1978, 1989; Cinque (1997 [1983]); Ziv (1994); Acuña-Fariña (1995); Valmala (2007); López (2009); Bianchi and Frascarelli (2010); Ott (2015); Fernández-Sánchez and Ott (2020), and Keizer (2020).

I show that an analysis along the lines of (3) accounts for the data successfully and solves a number of puzzles which arise in light of previous monosentential/integrated proposals that assume base-generation of the HTLDed constituent on the left edge of the sentences they precede (i.e., [XP HTLD [… [IP/TP …]]]). On the view pursued herein, the connection between the HTLD in CP1 and its host sentence, CP2, is one of discourse grammar, not of sentence grammar, as first claimed in the transformational generative framework by Cinque (1997 [1983]: 98). As observed by Fernández-Sánchez and Ott (2020: 16), “[t]his was indeed the conclusion of Cinque (1983) (see also Shaer and Frey 2004), but it is commonly dismissed by cartographically oriented works.” In fact, as noted, a considerable body of work was devoted to HTs in the pre-cartographic era that began in the late 1990s (see, e.g., Anagnostopoulou et al. [1997]), but since then, work on HTLDs has been sparse (on which, see Radford 2018). Moreover, in addition to circumventing some problematic issues for monosentential accounts, the bisentential account makes several correct predictions concerning the syntactic behavior of HTLDs. At the same time, the paratactic proposal advocated here is compatible with the major interpretative properties attributed to HTs in the literature.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, general properties of HTs are presented, with special reference to English and Spanish, alongside a note on the interpretation of HTs; Section 3 sketches the bisentential account pursued here. The different subsections devoted to the consequences of this approach provide several (old and new) empirical arguments in favor of parataxis, some of which relate to anti-connectivity: absence of binding and bound variables (Section 3.1.1); lack of canonical agreement and issues related to pronouns (Section 3.1.2); case (Section 3.1.3); comma intonation/pause potential (Section 3.1.4); extra-sentential (not just external) nature, including complementizers, V3 phenomena, and clitic placement (Section 3.1.5); insensitivity to islands and islandhood (Section 3.1.6); intercalated interjections (Section 3.1.7); ‘interrogative’ HTs (Section 3.1.8); orphaned HTs (Section 3.1.9); no HTs in right-dislocated positions (Section 3.1.10); and hyperdetached HTs (Section 3.1.11). Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 Hang in there! There’s an alien at the beginning of that clause and it has peculiar properties

2.1 What does a HT look like?

Hanging topics, which are invariably of the DP/NP category (Cinque 1997 [1983]), can be associated with virtually any syntactic function in the sentence to which they are adjacent, as shown for Spanish in (4) (and for English by some of the English translations):

| Pedro, | no | saca | nunca | la | cartera | el | muy tacaño. |

| Peter | not | pulls-out | never | the | wallet | the | very tight-fisted |

| ‘Peter is rather tight fisted. You never see his wallet out!’ | |||||||

| Ángela la | vecina, | creo | que | a | la | tipa | la | |||

| Angela the | neighbor, | believe | that | acc | the | individual | clacc | |||

| contrataron | en | Harvard | ||||||||

| hired | in | Harvard. | ||||||||

| ‘My neighbor Angela, I believe that they hired that woman at Harvard.’ | ||||||||||

| Yo, | la | verdad | es | que | no | me | regalaron | nunca | nada. |

| Inom, | the | truth | is | that | not | cldat | gave | never | nothing |

| ‘As far as I am concerned, I must admit that I was never given anything.’ | |||||||||

| Este, ya | dijo | muy | claro | que | no | contásemos | con | él. |

| This, already | said | very | clear | that | not | count | with | him |

| ‘This one, he made it very clear that we shouldn’t count on him.’ | ||||||||

| Chueca, | ¡qué | bien | me | lo | pasaba | allí | de | joven! |

| Chueca | what | well | clrefl | cl | passed | there | of | young |

| ‘Chueca, I had so much fun there when I was younger.’ | ||||||||

| 1992, en | ese | año | me | fui | yo | de | turné | a | Sevilla |

| 1992, in | that | year | clrefl | went | I | of | tour | to | Seville |

| y | a | Barcelona. | |||||||

| and | to | Barcelona | |||||||

| ‘1992, I went on a tour to Seville and Barcelona that year.’ | |||||||||

This set of examples also provides several pieces of relevant information about the behavior of hanging topics more generally. As is well known, hanging topics carry what for now I will call default case. In Spanish, this is nominative, as shown by pronominals, as in (4)c, despite the fact that the corresponding clause-internal argument is dative, and in English, accusative (cf. (1)a), even though the clause-internal subject is nominative. ClLDs, by contrast, bear structural case, as shown by (5)a, and may be of any category, as shown by (5)b, which contrasts starkly with (4)d:

| A | mí | no | me | regalaron | nunca | nada. |

| dat | me | not | cldat | gave | never | nothing |

| ‘They never gave anything to me.’ | ||||||

| Con | él | no | se | puede | contar. |

| with | him | not | climp | can | count |

| ‘We cannot count on him.’ | |||||

Topicalization in English is also not confined to default (accusative) case, as indicated by (6), where ___ signals the gap associated with such structures. It must be noted in passing that, much like topicalizations in English examples like (5), ClLDs in Romance also tend to perform a contrastive function, as in (5) (Arregi 2003; Kempchinsky 2013; López 2016; Ott 2014, 2015, among others) (I return to the meaning of HTLDs below):

| A: After hearing the evidence against them, what do you think about John and Mary? |

| B: (i) He, I think ___ is guilty but she, I don’t think ___ is. |

| (Adapted from Radford [2018: 51]) |

Returning to the paradigm in (4), observe that a HTLD is itself compatible with a coreferential preverbal phrase in the same clause, as shown for accusative objects in (4)b and for dative ClLDs in (7), a feature already noted explicitly by van Riemsdijk (1997):[3]

| Este k, | a | él k | no | se | le | puede | decir | ni | pío. |

| this, | dat | him | not | climp | cldat | can | say | nor | cheep |

| ‘This one, you really cannot tell him anything.’ | |||||||||

As the examples of HTLDs furnished so far illustrate, HTs are associated with a resumptive element (though see Section 3.1.9). HTs may be connected to a weak (clitic-like) or strong pronoun/demonstrative, an epithetic correlate, a quantifier, or a full DP, as shown for English by the data in (8):[4]

| Chomsky, I have never read anything by him. |

| And going to work every day, that helped. |

| (Monster: Jeffrey Dahmer, episode 5, Netflix 2022) |

| But these excursions , they formed the backdrop to his first novel, The Sun Also Rises. |

| (Simon Whistler, simonwhistler.com, Biographics, Ernest Hemingway, 2017) |

| Her… that poor woman has suffered a lot. |

| Books, she doesn’t read many. |

| What Mr Cameron has started, the EU need to continue that process. |

| (Listener, BBC Radio 5, cited in Radford [2018: 53]) |

Spanish behaves in much the same way regarding resumption, which is further confirmed by the following spontaneous example from Iberian Spanish, where Facebook is interpreted as being coreferential with eso within the PP de eso:

| Facebook, | yo | de | eso | no | tengo. |

| I | of | that | not | have | |

| ‘I don’t use Facebook (or any other social media).’ | |||||

The epithetic-correlate option is not generally available to ClLDs (Villa-García 2019, inter alia), which, in contrast to HTLDs, can only be linked to a clitic (e.g., (5)a)), as (10) shows:[5]

| % A | Juan | no | lo | contrataron | al | pobre | en | Microsoft. |

| acc | John | not | clacc | hired | acc+the | poor | in | Microsoft |

| ‘Microsoft didn’t hire poor John.’ | ||||||||

HTLDed phrases are typically set off intonationally from the sentence with which they occur (see Feldhausen [2016] and references therein). The ‘comma intonation’ (or pause potential, à la Emonds [2004]) characteristic of HTs is usually represented by means of an orthographic comma, as in the preceding examples, though it is not surprising that given the occasional extra strength of this intonational break, some of my English-language and Spanish-language consultants intuitively re-wrote the sample sentences presented to them in writing using suspension points (as does RAE-ASALE [2009: 2975–2976], which in fact makes reference to the terminological variant ‘suspended topics’):[6]

| Juan… | ¡qué | alto | está | el | chaval! |

| John | what | tall | is | the | boy |

| ‘John, that boy is so tall!’ | |||||

The distinction between HTLDs and topicalizations in English is rather straightforward, as the former are Resumptive-linked, while the latter are Gap-linked (___). In Spanish, by contrast, if the dislocate is non-human, the accusative marker (viz. Differential Object Marking) will be absent in ClLDs featuring direct objects. Thus, as observed by López (2009) and Villa-García (2015), the following data are not helpful when it comes to teasing apart HTLDs and ClLDs. In (12)a, it is not obvious whether the non-human dislocate el libro is a HTLDed phrase or a ClLDed one (the only difference being possibly the potential comma that would more commonly accompany a HTLDed constituent in writing to represent the marked prosodic boundary that usually follows HTs; see also RAE-ASALE 2009: 2980). In (12)b, the problem vanishes, as the presence of the epithet ese tostón ‘that bore’ unequivocally points to the conclusion that el libro is a HT.

| El | libro | Juan | no | lo | leyó. |

| the | book | John | not | clacc | read |

| ‘The book, John didn’t read (it).’ | |||||

| El | libro, | ese | tostón | Juan | no | lo | leyó. |

| the | book | that | bore | John | not | clacc | read |

| ‘The book, John didn’t read that bore.’ | |||||||

A similar problem arises in relation to Spanish subjects, which are nominative, much like HTs. Recall that Spanish is a null subject language. As a result, a sentence like (13)a does not help distinguish a bona fide subject from a dislocated one (López 2009; Villa-García 2015, 2018). The underlying structure could be as in (13)b, with the pronominal subject in the canonical subject position, or as in (13)c; here, yo ‘I’ is a dislocated element, with the canonical subject position being filled by an empty category (by assumption, pro). Note further that it is not obvious whether yo in this instance would be a case of HTLD or of ClLD:[7]

| Yo | iré | a | la | fiesta. |

| I | will-go | to | the | party |

| ‘(As far as I am concerned), I will go to the party.’ | ||||

| Yo | iré | a | la | fiesta. |

| Yo, | pro | iré | a | la | fiesta. |

The intonation should help (yo, …), but such cases are not as easy to tease apart, particularly in writing, where prescriptively a comma between the subject and the verb is strongly discouraged. Note that having both dislocated and non-dislocated overt subjects in the same sentence is not unusual:

| Yo… | {yo} | no | me | hipoteco | {yo} | ni | en | sueños | {yo}. |

| I | I | not | clrefl | mortgage | not | in | dreams | ||

| ‘Me, I won’t ever take out a mortgage loan.’ | |||||||||

As an additional diagnostic to distinguish HTLDed subjects from non-dislocated ones, Casielles-Suárez (2004) notes that only full DPs can occupy the canonical subject position, bare NPs being confined to HTLDed contexts, as the following contrast suggests:

| *Niños | no | juegan | en | este | parque. |

| children | not | play | in | this | park |

| ‘Children don’t play in this park.’ | |||||

| Niños, | me | dijo | mi | primo | que | no | juegan |

| children | cldat | said | my | cousin | that | not | play |

| muchos | en | este | parque. | ||||

| many | in | this | park | ||||

| ‘As for kids, my cousin told me that not many play in this park.’ | |||||||

As should be evident from the preceding discussion, HTLDed subjects in English are not difficult to detect, as the HTLDed phrase is routinely marked as accusative, in spite of its frequent association with a clause-internal nominative subject:

| Me, I don’t think I’ll ever become department head. |

Another well-documented property of HTLDs is that they are not sensitive to locality-of-movement constraints, unlike topicalizations. This is illustrated in (17). The relevant configuration is an instantiation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint, which posits that extraction from one single conjunct results in ungrammaticality. As the contrast illustrates, HTLD is fine in this context (cf. (17)a), but topicalization is not (cf. (17)b):

| My father, I hardly ever see him and my mother when they are not glaring at each other. |

| *My father, I hardly ever see ___ and my mother when they are not glaring at each other. |

| (van Riemsdijk [1997: 1]) |

The same can be said of Spanish on the basis of the following data:

| Yo, | el | examen | nos | salió | mal |

| I | the | exam | cldat | exited | bad |

| a | mí | y | a | ella. | |

| dat | mi | and | dat | her | |

| ‘As far as I am concerned, neither she nor I felt we did well in the test.’ | |||||

| *A | mí | el | examen | nos | salió |

| dat | me | the | exam | cldat | exited |

| mal | ___ | y | a | ella. | |

| bad | and | dat | her |

I will defer discussion of additional properties of HTLDs until the analysis presented in this paper has been introduced. For now, it will suffice to conclude this section by summing up the major properties of HTLDs observed so far (for English and Spanish):

HTs are NPs/DPs.

HTs bear (default) accusative (English) and nominative (Spanish) case.

In the general case, HTs may be linked to virtually any syntactic function in the clause they are adjacent to.

HTs are usually connected to a resumptive, be it a (weak/strong) pronoun (e.g., a clitic), an epithetic correlate, a quantifier, or a full DP (which may itself be dislocated).

HTs are often set off intonationally from the clause with which they appear.

HTs are island-insensitive.

As far as the theoretical treatment that HTs have received in the literature is concerned, with the advent of the cartographic approach, several analyses have been proposed that try to locate HTs in the left-peripheral spine. ClLDs have been primarily analyzed as occupying the specifier position of TopicP under Rizzi’s left-peripheral/cartographic approach, as in (19)b. Since HTs routinely precede ClLDs, as indicated by (7) and (19)a, most works assume a higher, leftmost position for HTs along the clausal left edge (see, e.g., Krapova and Cinque 2008), as shown abstractly in (19)b, in some cases even above the highest split-CP projection (ForceP), which reflects their ‘extremely external’ character.

| Hemingway HTLD , | al | pobre ClLD | le | salía | todo | mal. |

| Hemingway, | dat+the | poor | cldat | exit | all | bad |

| ‘Hemingway, the poor thing was very unlucky.’ | ||||||

| [XP HTLDed phrase … [TopicP ClLDed phrase [FocusP [FinitenessP [IP/TP … ]]]]] |

Our XP projection in (19)b has been posited to be a Discourse Projection constituent (Emonds 2004); a DiscourseP above ForceP in Rizzi’s system (Benincá 2001); ForceP, with the HT in its specifier (Faure and Oliviéri 2013); an HP projection whose nucleus is a discourse head (Cinque 2008; Giorgi 2014); a FrameP constituent, as argued by Haegeman and Greco (2016); and a high position in the frame subfield resulting from the split of the topic field postulated by Benincà and Poletto (2004). Whatever the case may be, the common denominator to said accounts is the assumption that, albeit external, HTLDed constituents are part of the sentence on whose edge they occur (hence the monosentential/integrated nature of this line of analysis). Moreover, as noted in Section 1, extant accounts have also focused on addressing the question of whether HTs are derived via movement to the specifier of the XP projection in (19)b or base-generation in that slot.

Before presenting the bisentential proposal put forward here, I turn to a brief outline of the main interpretive properties of HTs mentioned in the literature.

2.2 What’s in a HT?

Regarding the interpretation of HTs, it is generally assumed by most authors in the generative tradition that HTs are aboutness topics (see below for evidence that certain topics akin to HTs are heralded by speaking about-type phrases). For instance, Cinque (1997 [1983]: 95) points out that “the lefthand phrase [i.e., the HT] is used to bring up or shift attention to a new or unexpected topic.” Bianchi and Frascarelli (2010: 15), for their part, claim that left dislocations in English constitute “a shift with respect to the aboutness topic of the previous sentence.” Put another way, HTs represent a change in what is being talked/written about. Different contexts may however trigger slightly different interpretations, as shown in (20):

| During his month’s recuperation, Ernest and Agnes explored the sights of Milan together. Hemingway, he became enamored with the dark-haired beauty who was seven years his senior. Her feelings, however, they were not so strong, despite agreeing to marry him at the war’s end. |

| (Simon Whistler, simonwhistler.com, Biographics, Ernest Hemingway, 2017) |

The first HT in (20), Hemingway, appears to be a case of topic continuation (the biographic podcast to which this excerpt belongs is all about the famous American author) or even a contrastive topic (as opposed to Agnes), as argued by Geluykens (1992: 87). The second HT, her feelings, does however constitute a case in which there is a change in what is talked about: from talking about individuals, the conversation now moves on to their feelings (see also Stark [2022]).

More specifically, Givón (1983: 32) observes that HTs (which he calls left dislocations) are employed to return topics back to the register following a gap (cf. Hemingway in (20)) and deems HTs to be paragraph-initial devices related to major thematic breaks in thematic structure. In this connection, it should be noted that HTs tend to have a headline or section-title flavor to them: X, of which something is predicated (as in examples like Girls, they wanna have fun, which, needless to say, is part of the lyrics of the famous 1983 song by Cyndi Lauper, and Maria, you’ve gotta see her, by Blondie, 1999). This basically relates to the traditional theme-rheme/topic-comment partition. In the words of Tizón-Couto (2008: 251), “[HTs] establish a point of departure on which the subsequent message is grounded.” As Krapova and Cinque (2008: 259) contend, the connection between this sort of topic and the comment “is rather loose, i.e., a HT creates only a general context for the [c]omment.” Geluykens (1992) claims that HTs serve to introduce an “irrecoverable, i.e.[,] discourse-new (but possibly inferable) referent and a proposition concerning it” (Traugott 2007: 408).

Prince (1997: 124) argues that there are different kinds of HTs attending to their meaning (see also Tizón-Couto [2008]). One sort

serves to simplify the discourse processing of Discourse-new entities by removing them from a syntactic position disfavored for Discourse-new entities and creating a separate processing unit for them. Once that unit is processed and they have become Discourse-old, they may comfortably occur in their positions within the clause as pronouns.

Another type of HT interpretation distinguished by Prince (1997) is that in which the HTLDed phrase belongs to a partially ordered set, as in (21), which may as well be deployed by means of topicalizations/ClLDs instead (note that the English paraphrase shows that the same situation can be replicated in English):[8]

| Juan | tiene | varios | tipos | de | animales | en | casa. | Los | ratones, | a | ||

| John | has | various | types | of | animals | in | home | the | mice | dat | ||

| los | pobres | no | les | presta mucha atención. | Los | peces, | sin | |||||

| the | poor | not | cldat | lends much attention | the | fish | without | |||||

| embargo, | a | esos | sí | que | no | les | falta | cariño. | ||||

| however | dat | those | yes | that | not | cldat | lack | love | ||||

| ‘John has several types of animals at home. Mice, he doesn’t pay much attention to the poor things; the fish, however, those do get much love.’ | ||||||||||||

Be that as it may, despite differences arising from the different contexts in which they occur, HTLDs can be subsumed under the general, umbrella term ‘aboutness.’ In this sense, Ziv (1994: 633) concludes that the thread linking all characterizations of the functions of hanging topics is “basically introductory.” López (2009: 19) provides a summary of the interpretation of hanging topics by noting that a HT phrase can be “a shift-topic or it can be anaphoric, contrastive or not.”

In the next section, I sketch a bisentential, paratactic analysis of HTLDs, and in so doing, I discuss further properties of said structures, to be added to the list provided at the end of the preceding subsection. Although the focus is English and Spanish HTLD, mention of the construction in other languages will be made throughout when appropriate. I also draw comparisons with competing accounts (i.e., monosentential/integrated analyses) as the discussion unfolds.

3 ‘I’m hanging in a different sentence,’ said the HTLDed phrase: toward a bisentential account of HTLD

In glaring contrast to monosentential accounts (see Section 2.1), the bisentential, paratactic analysis proposed herein is rooted in Ott’s (2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 biclausal analysis of ClLDs and also of predicative non-restrictive nominal appositives (e.g., I came across Andrew Radford, [an old professor of mine], at the store). Focusing first on ClLDs, Ott’s system constitutes a drastic departure from monosentential/integrated left-peripheral accounts of ClLDs whereby the dislocated phrase sits in the specifier of TopicP, a projection along the split CP of Rizzi (1997 et seq.), as shown abstractly and in simplified form again in (22) (see also (19)b):

| [ForceP [TopicP ClLDed phrase [FocusP [FinitenessP [IP/TP cl V…]]]]] |

An analysis of this ilk makes the claim that the ClLDed constituent is part of the clause, albeit it is situated at the front of the clause (i.e., monosententiality). In the wake of integrated proposals, Ott (2015: 225) capitalizes on Cinque’s (1990) Paradox, which contends that “dislocated XPs [e.g., ClLDs] are extra-sentential constituents akin to parentheticals while behaving in certain respects as having moved to their surface position from within the host clause, in apparent violation of the boundaries of ‘sentence grammar’ as typically defined.”[9] Put another way, ClLDs display movement and non-movement properties alike. In order to resolve this paradox, Ott develops a system wherein dislocated XPs of the ClLD kind are elliptical fragments that are linearly juxtaposed to their host clause (so that dislocate and host are paratactically ordered but anaphorically related). On this view, a Spanish sentence with a ClLDed phrase like (23)a would be analyzed as in (23)b:

| A | mi | amigo | lo | vilipendiaron. |

| acc | my | friend | clacc | vilified |

| ‘My friend was vilified/My friend, they vilified.’ | ||||

| [CP1 |

[CP2 lo vilipendiaron] |

Ellipsis resolution under this analysis can only occur once the postcedent (CP2) has been uttered, in much the same way as in regular cases of ‘backward’ ellipsis:

|

I don’t know when |

As Ott (2015) notes, the type of ellipsis featured in such constructions is not construction-specific, but attested in other ellipsis-related constructions, such as sluicing and fragment answers; the latter type is illustrated in (25):

| ¿A | quién | vilipendiaron? |

| acc | who | vilified |

| ‘Who did they vilify?’ | ||

| [ |

a | mi | amigo] |

| acc | my | friend | |

| ‘My friend.’ | |||

An immediate advantage of this analysis, which I will not review here in detail given space limitations, is that it straightforwardly explains the otherwise mysterious presence of the attending clitic in ClLDs and which in fact gives the name to the construction (cf. Clitic Left Dislocation, ClLD): under bisententiality/parataxis, lo is in a different clause from the dislocate a mi amigo, in parallel fashion to what happens in (26), which unambiguously involves a sequence of two separate root sentences. Cross-sentential coreference between the relevant nominal phrases takes place in both (23)a and (26) without further ado.

| Conocieron | a | mi | amigo. | Lo | vilipendiaron. |

| met | acc | my | friend | clacc | vilified |

| ‘They met my friend. They vilified him.’ | |||||

In essence, the clitic lo refers back to its antecedent a mi amigo in a separate, preceding sentence both in ClLD, as in (23)a, and in cases uncontroversially featuring two separate sentences, as in (26), precisely as expected under Ott’s bisentential analysis of ClLDs.

Note that the second sentence needs to be syntactically complete, and this cannot be achieved in the absence of the clitic (viz. *A mi amigo vilipendiaron vis-à-vis (23)a and Conocieron a mi amigo. *Vilipendiaron vis-à-vis (26)).

Similarly, the presence of the accusative marker a in the dislocate a mi amigo in (23)a is explained away under Ott’s analysis: this nominal receives case from the elided transitive verb vilipendiaron in a standard, head-to-complement fashion. The analysis also overcomes other issues faced by monosentential proposals, such as why no condition B effects are observed, given that in (22) the ClLDed phrase c-commands the clitic pronoun lo. This potential issue is immediately sidestepped under parataxis, since pronoun and antecedent are in separate, albeit juxtaposed, sentences (i.e., CP1 and CP2 in (23)b).

Despite the evidence indicating that HTs, our focus here, are clearly ‘satellite’ constituents that are outside the sentence they accompany (Cinque 1997 [1983], among others), a bisentential analysis for HTLDs exactly like the one that Ott has pursued for ClLDs is plainly untenable, as shown in (27). The HT bears nominative case and yet it is not the subject in (27)a, making an analysis identical to that of ClLDs outlined above implausible (cf. (27)b):

| Yo, | me | vilipendiaron. |

| Inom | clacc | vilified |

| ‘(As for) me, I was vilified.’ | ||

| *[CP1 |

[CP2 me vilipendiaron] |

Whatever the case may be, if under Ott’s analysis ClLDs are not part of the clause on whose left edge they seem to occur, this too surely must be the case of HTLDs, whose connectivity to the clause with which they appear is even more tenuous than in the case of ClLDs. Although (27)b is clearly not an option for HTLDs, my proposal draws on Ott’s general line of research. More specifically, the analysis is loosely based on Ott’s (2016) bisentential derivation of predicative non-restrictive appositives, exemplified in (28)a, which he argues should be analyzed as in (28)b:

| I met Noam Chomsky, the person who first uttered the epic sentence ‘colorless green ideas sleep furiously,’ at an event at Georgetown. |

| [CP1 I met Noam Chomsky | ⇑ | at an event at Georgetown] |

| [CP2 |

||

Using evidence from English and German, Ott (2016) shows that these non-restrictive appositives function as predicative supplements, separate propositions expressing a predication. Note that a claim made by such a proposal is that non-restrictive appositives are syntactic disjuncts (extra-sentential expressions). In the words of Ott (2016: 39), a fragment like the person who first uttered the epic sentence… in (28)a is “linearly interpolated into the externalized form of the host clause in discourse as an interrupting speech act, rather than integrated syntactically.”

Armed with the ingredients above, let us now see how an analysis of this ilk can be applied to the case of HTLDs.[10] My proposal is to analyze Hanging Topic Left Dislocations as genuinely ‘external’ constituents in a bisentential fashion. I will use an example like (29) to illustrate the account in what follows:

| His temper, it was volcanic. |

| (Simon Whistler, simonwhistler.com, Biographics, Ernest Hemingway, 2017) |

A sentence featuring a HTLDed phrase like (29) consists of two underlying sentences under the view pursued here. Despite outward appearances, (29) contains two independently generated root sentences, one of which is elliptical. More concretely, the first sentence, CP1, is an elliptical sentence in which only the element that will end up being the HTLDed phrase survives ellipsis.[11] An immediate question which arises is what the content of this elliptical sentence is. Given the ‘aboutness’ character of hanging topics, it is natural to assume an underlying sentence along the lines of the following copular constructions (see the discussion around (28) for Ott’s [2016] bisentential analysis of predicative non-restrictive appositives involving an elliptical copulative sentence): ‘the topic/theme is X,’ ‘the topic of the upcoming sentence is X,’ ‘the topic of conversation is X,’ ‘what the upcoming discourse/sentence is about is X,’ or ‘the upcoming topic is X.’ For the sake of illustration, I will choose the following:

| [CP1 |

The ‘aboutness’ and upcoming-topic-of-conversation character of HTLDs is indeed corroborated by the observation that some topics are commonly introduced by speaking about-type phrases (Rubio Alcalá 2014: 107):[12]

| Speaking of Chomsky, I was told that he doesn’t write about linguistics anymore. |

| Hablando | de | Chomsky, | me | dijeron | que | ya | no | escribe | |

| speaking | of | Chomsky | cldat | said | that | already | not | writes | |

| sobre | lingüística. | ||||||||

| about | linguistics | ||||||||

CP1 is then juxtaposed to CP2, which is an independent and syntactically complete sentence:

| [ CP2 it was volcanic ] |

Indeed, English provides evidence for the syntactic completeness of CP2/the host sentence, in whose vicinity the HT occurs. In their discussion of double-that sentences (cf. recomplementation), Villa-García and Ott (2023) show that the sentence heralded by the second instance of the complementizer needs to be syntactically complete, as the secondary that signals a restart in discourse. What this means in practice is that when it comes to embedded topicalizations (as in (33)a) and hanging topics (as in (33)b), only the latter are possible in the context of recomplementation, as the following contrast from Villa-García (2019) highlights (see Section 3.1.5 for comparable Spanish data):

| *They told me that Peter, [that they don’t like ___ ]. |

| They told me that Peter, [that they don’t like him]. |

The [second sentence] must be complete from point of view of syntax; this requirement is not met in (33)a, which is ungrammatical, but is fulfilled in (33)b, where the resumptive pronoun associated with the sandwiched HT fills in the host-sentence-internal object position, thus making the second sentence syntactically complete.

The HT in CP1 and its syntactically complete host in CP2 are therefore paratactically ordered but anaphorically related. Note that the claim is not that such examples involve hypotaxis in any sense; CP1 and CP2 are the outputs of two independent derivations (i.e., they are neither transformationally related nor subordinated to each other):

| [CP1 |

| [ CP2 it was volcanic ] |

Three questions immediately arise in light of the bisentential, paratactic proposal outlined in (34). The first issue concerns the operation of ellipsis, since parallelism of CP1 and CP2 does not obtain in (34). The second one concerns the coreference established between the HTLDed constituent and its correlate in CP2 (e.g., [His temper k], it k/*j was volcanic). The third question is related to the potential co-occurrence of HTs and ClLDs (in that order) under the approach pursued here. I will address each of them in turn.

As for ellipsis, the sentences containing HTLDs under the account currently pursued (CP1) are not reformulations but reduced copular clauses à la Ott (2016). This type of ellipsis involving copular-clause reduction is independently attested in the natural languages. Merchant (2004b) and Ott (2016) refer to this kind of ellipsis operation as limited ellipsis, which is licensed contextually and thus requires no antecedent (or postcedent) for purposes of recoverability. According to Merchant (2004b: 723), the first part of the copulative sentence, including the subject and the copula itself, can be elided “given the appropriate discourse context, which will be almost any context where the speaker can make a deictic gesture, and where the existence predicate [e.g., be] can be taken for granted.” Ott (2016: 11) takes this sort of elliptical construction to apply more broadly (i.e., to predicative non-restrictive appositives, as noted above). The operation in question is illustrated by examples like (35):

| pointing at a picture of a person on a smartphone: | ||||||

| a. | Me | / | him | / | Hemingway. | (= [CP

|

| b. | Yo | / | él | / | Hemingway. | (= [CP

|

| I | he | Hemingway | is/am I he Hemingway | |||

I thus take HTLDs to be the result of a process akin to limited ellipsis, as in (34), along the lines of Ott (2016) for predicative non-restrictive appositives. In support of this hypothesis, it should be noted that on occasion, the elided part of (35) remains visible in PF (i.e., it does not undergo ellipsis). This is actually the case with HTs as well, as the following piece of data, kindly provided by an anonymous reviewer, suggests:

| Bueno, | el | tema/problema/caso | es | tu | hija; | no | hay |

| well | the | topic/problem/case | is | your | daughter | not | there-is |

| quien | la | aguante. | |||||

| who | cl. | bears | |||||

| ‘Well, the problem is your daughter; nobody can stand her.’ | |||||||

As regards (mandatory) coreference between HT and correlate, this too cannot be enforced by parallelism between the two underlying CPs. Following Ott’s (2014, 2015, 2016 lead, I propose instead that coreference arises because of the rhetorical relation between CP1 and CP2. To illustrate this, consider (37)a vis-à-vis (37)b:

| I met Hemingway at [his mansion] j . I will now talk about [his writing] k ; it k/*j/*i was impressive. |

| [His writing] k , it k/*j/*i was impressive. |

In (37)a, once his writing is introduced into the picture, the only possible referent for the pronoun it in the last sentence contained in (37)a is his writing, not his mansion. If the (sub)topic of conversation (his writing) had not been introduced, nothing would preclude it from referring to his mansion despite the presence of an intervening sentence:

| I met Hemingway at [his mansion] j . That was back in the States. It j was impressive. |

As we see in (37)b for HTs, coreference between it and his writing is obligatory. This is not surprising, as the HT must be present in CP1 for the HTLD construction to be deployed and thus the HT phrase is the only potential discourse referent, salient antecedent for the pronoun it in CP2. Even if there is a potential antecedent right before the HT, coreference between that element and the pronoun is not possible:

| I met Hemingway at [his mansion] j . [His writing] k , it k/*j/*i was impressive. |

In other words, obligatory coreference between the HTLDed phrase in CP1 and its correlate in CP2 is enforced “not grammatically, but by text/discourse coherence” (Ott 2016: 17), which resonates with Cinque’s (1997 [1983]: 98) claim that “the ‘connection’ [between HT and correlate] is not a sentence grammar rule but a principle of discourse grammar.” Put another way, as Zubizarreta (1999: 4224) observes, the relationship between the HT and the sentence it occurs with is not syntactically restricted: the relationship is merely (co-)referential. What is more, no syntactic dependency is established between HT and host sentence, Zubizarreta contends, an aspect upon which I elaborate below. López (2009: 19), for his part, characterizes this relationship as one established “by means of a loose discourse connection (as that between a name and a pronoun).”[13]

Although the sentence that follows the HT is syntactically complete (i.e., the HT is not required as far as syntax is concerned), part of the meaning of the host sentence results from the association established with the HT. In this connection, the HTLDed construction occurs next to an open sentence, a sentence that typically contains “a pronominal position lacking independent reference” which, as Cinque (1997 [1983]: 99) notes, must be “anaphorically linked to the NP in the sentence peripheral position” –the HTLDed constituent.

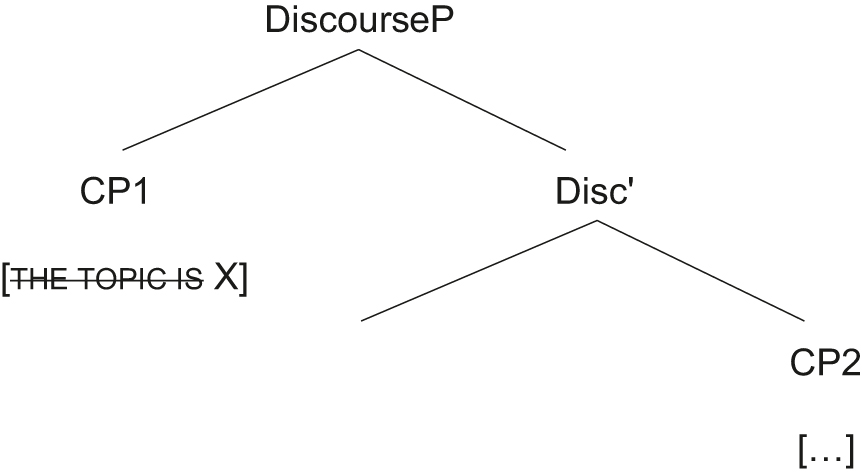

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, a note is in order regarding the association between CP1 and CP2. The work of Ott makes the claim that the pragmatic connection between CP1 and CP2 is not syntactically determined but enforced by text/discourse coherence, a notion that can be deemed to be obscure. Therefore, I will now adumbrate an alternative that circumvents this objection. According to this reviewer, a more transparent syntactic implementation of the relationship between CP1 and CP2 would be to postulate, following a long tradition (see, e.g., Bianchi and Frascarelli [2010] and references therein), a discourse-related head linking both CP1 and CP2. An immediate advantage of this move would be to dispense with hazy and potentially problematic implications of notions such as ‘discourse grammar’ or ‘text coherence,’ which are nonetheless assumed without further ado in different works, as shown in the preceding paragraph. The suggested alternative analysis would look thus:

|

In any case, due to space limitations, I will leave a more thorough investigation of the consequences of adopting the account in (40) for future research.

The third question posed by the analysis advocated here relates to HTLDs vis-à-vis ClLDs under the overall approach to left dislocations pursued here, which draws heavily on the work of Ott (2014, 2015. It is well known that HTs precede ClLDed phrases, as shown in (19)a, repeated here for convenience as part of the following contrast:

| Hemingway HTLD , | al | pobre ClLD | le | salía | todo | mal. |

| Hemingway, | dat+the | poor | cldat | exit | all | bad |

| ‘Hemingway, the poor thing was very unlucky.’ | ||||||

| *Al pobre ClLD , | Hemingway HTLD , | le | salía | todo | mal. |

Recall that for Ott, ClLD is derived in a bisentential fashion, with the ClLDed phrase being the remnant of an ellipsis operation along the lines of (42):

| [CP1

|

My proposal for HTLDs is that the type of ellipisis involved requires no parallelism with CP2 (cf. limited ellipsis; see (35)/(34)), in contrast to what happens with ClLDs (cf. (42)), which do require parallelism with the host clause. Consequently, HTLDed phrases are even more detached from the host sentence than ClLDed phrases, hence the restrictive ordering effect observed (cf. (41), where HTLD > ClLD). Moreover, the CP1 hosting the HT basically introduces the general topic of the upcoming sentence (i.e., the host sentence), which accounts for why we typically have only one HT (though see Radford 2018), as opposed to ClLDs, which can be iterative (Rizzi 1997; Ott 2015). Under the approach adopted herein, a sentence involving both a HT and a ClLD concurrently would be analyzed thus:

| [CP1 |

In the following subsections, I explore the (mainly syntactic) consequences of the bisentential, paratactic treatment of HTLDs advanced here.

3.1 Consequences of treating HTLD as a bisentential phenomenon: theoretical predictions

3.1.1 Binding and bound variables

As noted, HTLDs that have a clause-internal corresponding element establish a coreference relation with said element, as suggested again by the following sentences:

| That man k , we gave the book to him k yesterday. |

| (Dik [1978: 391]) |

| Hugo k , | Vane | cuenta | con | él k . |

| Hugo, | Vanessa | counts | with | him |

| ‘Hugo, Vanessa counts on him.’ | ||||

Under monosententiality, it is not clear how to void the Condition B effect that would arise if the HTLDed phrases (that man and Hugo) c-commanded the pronouns with which they corefer, contravening Condition B of the Binding Theory:

| [XP that man/Hugo … [IP/TP … [VP … [PP him/él …]]]] |

The HTLDed phrase may be base-generated in the specifier of a projection like XP in (45), but this does not preclude it from c-commanding the pronoun in the VP phrase, not matter how far down in the syntactic tree the pronoun occurs. Therefore, it is not at all obvious how to prevent a Condition B violation in such cases under an integrated analysis along the lines of (45). Note that such effects certainly ensue in sentences with the subject higher than the pronominal:

| That man k gave the book to him *k/i yesterday. |

| Hugo k | cuenta | con | él *k/i . |

| Hugo | counts | with | him |

| ‘Hugo counts on him.’ | |||

The same situation holds for Condition C effects, as referential expressions should be free in the overall structure (i.e., sentence) containing them, as indicated by the contrasts in (47):

| Peter j/*k /he j/*k likes Peter k . |

| Peter j/*k /he j/*k thinks that Peter k gorges on pizza. |

| I met Peter k in Notting Hill last week by chance. By the way, I was told that your mate Susan finds Peter k gorgeous. |

Again, monosententiality provides no convincing answer to why Condition C is not violated in the case of HTs and their correlates, as shown by (48).

| John k , I don’t know anybody who likes John k a whole lot. |

| (Ziv [1994: 631]) |

| Patrick k , where is Patrick k ? |

| (The Man with the Answers, 2021 movie, Cyprus, Greece, and Italy) |

| Este k , | el | pobre | chaval k | está | fatal. |

| this | the | poor | guy | is | terrible |

| ‘This one, the poor guy is not doing well.’ | |||||

| El | dinero k , | ya | me | había | olvidado | del | dinero k . |

| the | money | already | clrefl | had | forgotten | of+the | money |

| ‘The money, I had already forgotten about the money.’ | |||||||

| (Spontaneous speech, Spain, May 2022) | |||||||

Note in passing that examples (48)a, b, d actually feature cases where the HT and the correlate are the same element, the DP John/Patrick/el dinero, exactly as expected if the second sentence is an independent, syntactically complete sentence (much like what we observe in relation to unambiguously independent sentences, as in (47)c); however, this state of affairs is rather problematic under unisentential accounts.

For reasons like this and others to be explored below, in this paper, I take the characterization of HTs as ‘extra-sentential’ constituents seriously (Dik 1978, 1989; Cinque 1997 [1983]; Ziv 1994; Acuña Fariña 1995; Ott 2015; Keizer 2020, among others). In fact, my major theoretical claim is that HTs belong to a preceding, elliptical sentence juxtaposed to the host sentence, as outlined in the preceding section:

| [CP1 |

|

| [ CP2 we gave the book to him yesterday/Vane cuenta con él ] | (= (44)a, b) |

Under bisententiality, the cofererence between HT and resumptive is not established grammatically at the level of the sentence, but at the rhetorical level, in discourse grammar (see Section 3 for further details).[14] Hence, no Condition B or C violations arise. Therefore, once analyzed as extra-sentential elements, the relevant examples do not contravene either of the principles of Binding Theory (see also Ziv [1994: 631]). The same is found, unsurprisingly, in parallel cases of unambiguously separate sentences, as in (47)c/(50), which are analogous to (49), modulo the ellipsis assumed in CP1 in (49).

| We met that man k a while ago; we gave the book to that man k /him k yesterday. |

| Este | es | Hugo k ; | Vane | cuenta | con | Hugo k /él k . |

| this | is | Hugo | Vanessa | counts | with | Hugo/him |

| ‘This is Hugo; Vanessa counts on Hugo/him.’ | ||||||

All in all, under the two-sentence proposal, the potential problem of what look like anomalously coreferring nominals posed by monoclausality ceases to exist. What is more, the need for HT and resumptive to be coreferential follows from the assumptions laid out at the beginning of Section 3 without further ado.

Lastly, HTLDs stand in stark contrast with ClLDs and topicalizations in not being able to feature anaphors or reciprocals, as shown by (51):

| *Himself, he would never pass him over. |

| (Radford [2018: 48]) |

| *Él mismo, | Juan | se | manda | emails | a | él | mismo. |

| he same | John | cldat | send | emails | dat | he | himself |

| Intended: *‘Himself, John sends emails to himself.’ | |||||||

This state of affairs follows naturally under bisententiality, since the anaphor is in an elliptical copular sentence in which it fails to be bound by a suitable antecedent:

| [CP1 |

| [ CP2 he would never pass him over/Juan se manda emails a él mismo] |

The same can be said of the unavailability of the bound-variable interpretation with HTLDed constituents (for Spanish, see, especially, López 2009 and references therein):

| His supervisor k/*i , [every student] i admires him. |

| (Radford [2018: 50]) |

| Su | perro k/*i, | [todo | quisqui] i | lo | acaricia | diariamente. | |

| his/her | dog | all | everyone | clacc | pet | daily | |

| ‘His/her dog, everybody pets him/her/it every day.’ | |||||||

The data just reviewed are fully consistent with the bisentential, paratactic analysis of HTs proposed here (as the operator, e.g., every student/todo quisqui, does not c-command the possessive pronoun, namely his/su, since operator and pronoun belong to two different sentences, CP2 and CP1, respectively, much as in the case of anaphors in (52) above).

Overall, the anti-connectivity displayed by HTs can straightforwardly be accounted for by assuming that the HT and its correlate belong to two separate sentences (CP1 and CP2), linked to one another paratactically.[15] Needless to say, the evidence adduced here strongly militates against a movement analysis of HTs in a monosentential setting under integrated approaches (cf. (19)b); the binding and variable-binding evidence is at best marginally compatible with base-generation of the HT in a high position in the left periphery, although both derivations run up against non-trivial problems.

3.1.2 Agreement and pronouns

Another aspect that underscores the anti-connectivity evinced by HTs is agreement. If hanging topics are extra-sentential elements that are juxtaposed to the host sentence, one would expect a certain degree of agreement mismatches between the HT and the element associated with it inside the sentence to which it is adjacent, since the (pragmatic) connection between the two is rather loose and in no case intra-sentential. Examples like (54) confirm that lack of full agreement is sometimes the case:

| Full details and latest transfer news, it’s all on the website. |

| (Ian Abrahams, Talksport Radio, cited in Radford [2018: 53]) |

| My last boyfriend in Chicago, we were together forever. |

| (Emily in Paris, episode 9, season 3, Netflix 2022) |

Spanish also displays such mismatches:

| Claro, | las | colchas | es | distinto. |

| clear | the | duvets | is | different |

| ‘Of course, duvets, that’s different.’ | ||||

| (Marcos Marín, corpus example, cited in [Hidalgo 2002: 7])[16] | ||||

These data argue strongly against a movement analysis under monosentential/integrated accounts (Radford 2018; van Riemsdijk and Zwarts 1974); clearly, the HT cannot be a mere copy of the second NP arising via movement (e.g., full details and latest transfer news – it).[17]

Further, agreement facts in relation to collective nouns like gente ‘people’ in Spanish provide additional support for the claim being put forth here that the HT occurs in a sentence that paratactically precedes the host. Despite making reference to a group of individuals, gente is syntactically singular and feminine:

| La | gente | está | enferma. |

| the | people | is | illsg, fem |

| ‘People are not doing well.’ | |||

| Vi | a | la | gente | del | pueblo | cabizbaja. |

| saw | acc | the | people | of+the | village | dejectedsg, fem |

| ‘I saw the people from the town dejected.’ | ||||||

| Esta | es | gente | con | la | que | no | cuento. |

| thissg, fem | is | people | with | thesg, fem | that | not | count |

| ‘These are people on who(m) I don’t count.’ | |||||||

By contrast, López (2007: 81–85) notes that despite being syntactically singular, a word like gente is semantically plural. Thus, in discourse, López (2009: 15) argues, “a pronoun that refers back to gente will show up in plural form.” Note that in this case, gender is also default masculine. This is shown by (57):[18]

| La | gente | llegó | tarde. | Estaban/*estaba | agotados/ | |

| the | people | arrived | late | were was | exhaustedpl, masc | |

| *agotada. | ||||||

| exhaustedpl, fem | ||||||

| ‘People arrived very late. They were exhausted.’ | ||||||

This situation makes a very clear prediction regarding HTs. If HTs are in a different sentence from the host and the relationship between HT and host is discursive, rather than purely syntactic, then HTs should be related to a plural entity in the host sentence. In other words, we should observe a pattern of behavior akin to that manifested across sentences, as in (57), rather than inside sentences, as in (56). This prediction is borne out, as speakers manifest a strong preference for a masculine-plural correlate of the HT containing la gente:[19]

| La | gente | de | mi | pueblo… | ¡Cómo | me | insultaban | |

| the | people | of | my | village | how | clacc | insultedpl | |

| los | muy | sinvergüenzas! | ||||||

| thepl, masc | very | shamelessplural | ||||||

| ‘The people of my village, the bastards really bullied me.’ | ||||||||

| ?*La | gente | de | mi | pueblo… | ¡Cómo | me | insultaba |

| the | people | of | my | village | how | clacc | insultedsg |

| la | muy | sinvergüenza! | |||||

| thesg, fem | very | shamelesssg |

| La | gente | de | nuestra | clase… | ya | no | me |

| the | people | of | our | class | already | not | clrefl |

| hablo | con | ellos | / | los | muy | tercos. | |

| talk | with | thempl, masc | thepl, masc | very | stubborn | ||

| ‘Our classmates, I don’t talk to them/those stubborn individuals anymore.’ | |||||||

| ?*La | gente | de | nuestra | clase… | ya | no | me |

| the | people | of | our | class | already | not | clrefl |

| hablo | con | ella | / | la | muy | terca. | |

| talk | with | hersg, fem | thesg, fem | very | stubbornsg, fem |

| Esa gente, | dios, | esos | mierdas | me | jodieron | viva. |

| that people | god | those | crapperspl | clacc | screwedpl | alive |

| ‘Those people, gosh, the bastards screwed me up bigtime.’ | ||||||

| ?*Esa gente, | dios, | esa | mierda | me | jodió | viva. |

| that people | god | that | crappersg, fem | clacc | screwedsg | alive |

The agreement facts just presented corroborate the extra-sentential character of HTs, exactly as predicted under parataxis (i.e., [CP1 … HT] [CP2 host sentence]).

Finally, a related point can be made on the basis of Brazilian Portuguese pronouns, which I will illustrate through the sequence a gente ‘lit. in the people.’ Brazilian Portuguese is a language that has been reported to display only a partial-null-subject system. Moreover, at present, a gente is used instead of the first-person plural form nós ‘we.’ However, a gente agrees with a third-person singular verb form:

| A | gente | vai | à | Feira | de | São | Cristóvão. |

| the | people | gosg | to | fair | of | saint | Christopher |

| ‘We go to St. Christopher’s Fair.’ | |||||||

If a second, embedded clause appears, then a null subject can occur (Jairo Nunes, pers. comm.), as shown by (60); I use pro for expository reasons, without making a commitment to the theoretical status of the coreferential null subject:

| A | gente k | acha | que | pro k | ganou | na | lotto. |

| the | people | believesg | that | wonsg | in | lottery | |

| ‘We think that we won the lottery.’ | |||||||

Nonetheless, across sentences, a null subject is not possible: the pronoun (e.g., a gente) must be repeated:

| A | gente k | fala | muito; | a | gente k | falou | tudo. |

| the | people | speaksg | much | a | gente | spokesg | all |

| ‘We speak a lot; we said it all.’ | |||||||

When HTs are brought into the picture, their pattern of behavior aligns not with what we observe in (60) for elements across dependent clauses within the same sentence, but with what we see across independent sentences, as in (61). The pronoun must be repeated:

| A | gente k, | a | gente k | falou | tudo. |

| the | people | the | people | spokesg | all |

| ‘Us, we said it all.’ | |||||

Parataxis provides a clear answer to the pattern observed: a null subject is not possible across independent sentences in Brazilian Portuguese, and the second sentence (CP2, the host) must be syntactically complete in (62) irrespective of the occurrence of a HT. Since Brazilian Portuguese in such contexts behaves like a non-null-subject language (we are dealing with a root sentence here, not with an embedded one, as in (60)), the second occurrence of the pronoun (a gente) must be present so as to satisfy the requirement to employ an overt preverbal subject operative in this language –a null subject is not licensed (i.e., without an overt preverbal subject, CP2 would be incomplete from the syntactic point of view). Consequently, HT examples featuring pronominals like a gente in Brazilian Portuguese indicate that HTs mask two underlying root sentences juxtaposed paratactically, much like in the case of unequivocally separate sentences (cf. (61)).

3.1.3 Case

The anti-connectivity of hanging topics is substantiated by the fact that HTs across the world’s languages have been reported to appear in absolute form (without case-marking) (Hidalgo 2002), or to bear either default case (accusative case in English, as shown again in (63)a, and nominative in Spanish, as in (63)b) or, more traditionally, casus pendens (‘hanging case’):

| *I/me, they don’t trust me. |

| Yo/*mí, | no | confían | en | mí. | |

| I me | not | rely | on | me | |

| ‘Me, they don’t trust me.’ | |||||

The question which arises in relation to the case borne by HTs is how such nominals come to bear accusative or nominative case, depending on the language. Radford (2018) observes that this may be (i) default case (Schütze 2001), as the HT is outside the scope of any potential case-assigner (though see Merchant [2004a] against the notion of default case); (ii) the result of an abstract spec-head agreement relationship with a (null) topic head; or else (iii) the product of being preceded by an abstract (null) transitive topic-introducing preposition of the as-for type (e.g., as for me, they don’t trust me). The plausibility of such an account for the Spanish case is called into question by data like the following, indicating that topic-introducing expressions in Spanish typically assign accusative case (see also (31)b above):

| En cuanto | a | mí/*yo, | no | confían | en | mí. | ||

| as-for | to | me I | not | rely | on | me | ||

| ‘As for me, they don’t trust me.’ | ||||||||

There is one topic-introducing sequence, however, compatible with nominative case (albeit less common than en cuanto a):

| Lo | que | es | yo/*mí, | no | confían | en | mí. | |

| the | that | is | I me | not | rely | on | me | |

| ‘As for me, they don’t trust me.’ | ||||||||

Attractive as this account may seem, it is not clear that crosslinguistically all as-for constructions (or topic-introducing constructions more generally) constitute genuine HTs (on this issue, see, among others, Acuña-Fariña [1995]; Villalba [2000]; Krapova and Cinque [2008], and Stark [2022], among others). Moreover, an implicit assumption in some of the options suggested by Radford (2018) in (i)-(iii) is of course monoclausality, as the HT is regarded as an intra-sentential element, albeit left-peripheral.

Recall that the currently-pursued proposal constitutes a drastic departure from the above in that the HT belongs to an underlying copula sentence that has undergone ellipsis and which is juxtaposed to the host clause. The HTs are predicates in those copular clauses and as such receive the relevant case in each language: accusative in English (cf. (66)) and nominative in Spanish (cf. (67)) (see Ott [2016] for a similar approach to nominative case assignment in predicative non-restrictive nominal appositives in languages like German, illustrated for English above in (28)):

| [CP1 |

| [ CP2 I didn’t say anything ] |

| [CP1 |

|

|

|

||

| the | topic | of | conversation am me/I | ||

| [ CP2 yo | no | dije | nada ] | ||

| I | not | said | nothing |

Consequently, the bisentential account of HTs dispenses with the need to invoke ad hoc case-marking mechanisms for hanging topics; the case of such nominals is determined in CP1 in a standard, local fashion: they receive predicative accusative (English)/nominative (Spanish) case. Other languages follow this pattern too. For instance, Sigurðsson and van de Weijer (2021) show that the case exhibited in copular sentences in Swedish is nominative, in parallel fashion to Spanish. HTs likewise bear nominative case in Swedish, as expected:[20]

| Jag/*mig, | jag | gillar | bönor. |

| I/me, | I | like | beans |

| ‘Me, I like beans.’ | |||

| (Sigurðsson and van de Weijer [2021: 198]) | |||

The account put forth here can also go a long way to explain why it is only DPs/NPs that can be featured as HTs. A PP, for instance, would not be possible in predicative position:[21]

| [CP1 |

|

*de | mí ] | ||||

| the topic of conversation is/am | of | me | |||||

| [ CP2 | dijeron | cosas | de | mí ] | |||

| said | things | of | me | ||||

| Intended: ‘Me, they said things about me.’ | |||||||

A bare NP, such as niños in (15)b above, is also tolerated in the predicative position in CP1 (i.e., [CP1

el tema es/son

niños] …), which is consistent with the observation that such phrases sit well as HTs.

Having discussed anti-connectivity in terms of binding, agreement, and case, we now turn to other properties of HTs easily accommodated under bisententiality, and which further allow us to tease apart competing proposals.

3.1.4 Comma intonation/pause potential

As noted in Section 2, one of the distinguishing features of HThood is that the HT is more often than not separated from the sentence it accompanies by a salient intonational boundary (Acuña-Fariña 1995; van Riemsdijk 1997; Emonds 2004; Feldhausen 2016, among others). This is often rendered in spelling by a comma or by suspension points, as has been noted.

This is wholly compatible with the claim made here that the relation between the fragment HT (CP1) and its host sentence (CP2) is paratactic, each sentence forming a separate intonational phrase (cf. Nespor and Vogel 1986):

| (IntonP HT)CP1 | (IntonP …)CP2 |

Fragment and host thus typically exhibit ‘comma intonation’ (intonational isolation), exactly as expected if the sequence is composed of linearly juxtaposed root clauses in a paratactic rather than intrasentential arrangement. In Section 3.1.8, this claim is further substantiated by HTs whose illocutionary force differs from that of the host sentence, such as ‘interrogative’ HTs, which display their own interrogative intonation, unlike the falling intonation contour displayed by the non-interrogative sentence to which they are contiguous.

3.1.5 Really external, or rather, extra-sentential: complementizers, V3, and clitic directionality

Spanish provides a syntactic context which strongly confirms the outside-the-host-sentence character of HTLDs. In Spanish, the answer to a what-is-going-on or what-happened-to-you kind of question is typically heralded by the complementizer que ‘that.’ The data are inspired by those in Villa-García (2015):

| seeing that B has a sad face |

| ¿Qué | te | pasa? |

| what | cldat | happens |

| ‘What happens?’ | ||

| Que | depende | todo | el | mundo | de | mi | madre. |

| that | depends | all | the | world | of | my | mother |

| ‘(That) everybody depends on my mother.’ | |||||||

Now, if we try to promote the PP de mi madre to the very front, the resulting utterance is ungrammatical:

| seeing that B has a sad face |

| ¿Qué | te | pasa? |

| what | cldat | happens |

| ‘What happens?’ | ||

| *De | mi | madre, | que | depende | todo | el | mundo. |

| of | my | mother | that | depends | all | the | world |

| ‘Everybody depends on my mother.’ | |||||||

By contrast, if the element preceding que is a genuine HTLD (not a PP), the sentence becomes fully acceptable:

| seeing that B has a sad face |

| ¿Qué | te | pasa? | |

| what | cldat | happens | |

| ‘What happens?’ | |||

| Mi | madre, | que | depende | todo | el | mundo | de | ella. |

| my | mother | that | depends | all | the | world | of | her |

| ‘My mother, everybody depends on her.’ | ||||||||

That a HTLDed phrase (cf. (73)), but not a ClLDed PP (cf. (72)), can occur in pre-complementizer position confirms that the HTLDed phrase is truly external to the clause with which it appears.[22] Incidentally, a HT would be impossible in the immediate post-que position:

| seeing that B has a sad face |

| ¿Qué | te | pasa? |

| what | cldat | happens |

| ‘What happens?’ | ||

| *Que | mi | madre, | depende | todo | el | mundo | de | ella. |

| that | my | mother | depends | all | the | world | of | her |

| ‘My mother, everybody depends on her.’ | ||||||||

Not surprisingly, a true ClLDed constituent can sit well in the position immediately following que:

| seeing that B has a sad face |

| ¿Qué | te | pasa? |

| what | cldat | happens |

| ‘What happens?’ | ||

| Que | de | mi | madre | depende | todo | el | mundo. |

| that | of | my | mother | depends | all | the | world |

| ‘Everybody depends on my mother.’ | |||||||

Summarizing, we have the following possibilities in what-happened contexts in Spanish (though see fn. 22):

| *ClLD que … | (cf. (72)) |

| HTLD que … | (cf. (73)) |

| *que HTLD … | (cf. (74)) |

| que ClLD … | (cf. (75)) |

Importantly for our purposes, only a true HTLDed phrase can occur in the pre-que position in the context at issue (cf. (76)b), which corroborates the claim made here that HTLDs belong in a separate sentence and are therefore even more external than ClLDs, which may be subject to more stringent proximity requirements with respect to the host sentence (i.e., they require parallelism with CP2). Under monoclausality, an external position above the highest element in the left periphery (presumably above ForceP) would have to be invoked for HTs. Alternatively, it could be claimed that the head whose specifier is occupied by the HTLDed phrase would be lexicalized as que. However, it is not evident how this last option would be implemented, as que can occur (and normally occurs) independently of the HTLDed constituent, as indicated by (71), which severs the HTLDed element from the complementizer occurring to its right in cases like (73). Such stipulations are not necessary under bisententiality, and hence this theoretical option is to be preferred.[23]

Still within the realm of complementizers, it is important to discuss a well-known but poorly understood asymmetry in Spanish regarding the (im)possibility of embedded HTLDs. Several authors, including Zubizarreta (1999), have shown that HTs are confined to root contexts, examples like the following being illicit:

| *Estoy | segura | de | que | Bernardo, | nadie | confía | en | ese | idiota. |

| am | sure | of | that | Bernard | nobody | trusts | in | that | idiot |

| ‘Bernard, I am pretty sure that nobody trusts that idiot’. | |||||||||

| (Zubizarreta [1999: 4221]) | |||||||||

However, authors like Grohmann and Etxepare (2003), González i Planas (2011), and Villa-García (2015) have provided data to the effect that if a second que complementizer occurs after the (embedded) HT, then the HT becomes far more acceptable:

| Me | dijo | que | el | baloncesto, | que | ese | deporte | mola. |

| cldat | said | that | the | basketball | that | that | sport | rocks |

| ‘S/He told me that basketball, that that sport is fun.’ | ||||||||

| Dice | que | un | coche, | que | le | ha | cogido | la |

| says | that | a | car | that | cldat | has | taken | the |

| explosión | de | lleno. | ||||||

| explosion | of | full | ||||||

| ‘S/He says that a car, that the explosion has caught it in full.’ | ||||||||

| (Reporter, Madrid, 1973, featured in El asesinato de Carrero Blanco, Spanish Radio & Television Corporation, RTVE, 2014) | ||||||||

The obligatoriness of the second que in examples of embedded HTs like those in (78) has been shrouded in mystery to date (see Villa-García [2015] for much relevant discussion). Nevertheless, recent research has shown that secondary complementizers constitute restarts in discourse, signaling a new sentence that resumes the first one (Villa-García 2019; Villa-García and Ott 2023). If the second que marks the beginning of another sentence, as claimed by, e.g., Villa-García and Ott (2023), then the external nature of HTs (even in what appear to be cases of embedding) is not surprising: the HT is not part of the embedded clause, but outside it, much like in the cases reviewed above (cf. (71)–(75)):

| [CP1 | dice | que …] [CP2 |

|

|

|

|

|

un | coche ] | ||

| says | that | the | topic | of | conversation | is | a | car | |||

| [CP3 | … que | le ha cogido | la | explosión | de | lleno] | (= (78)b) | ||||

| that | cl has taken | the | explosion | of | full |

Since the HT in the elided CP2 is not syntactically part of the sentence heralded by dice que ‘says that’ (cf. CP1), the restart (CP3) needs to resume CP1 by means of repeating the complementizer in (79), which accounts for its mandatory occurrence in such cases.[24] In this sense, note that (78)b would be syntactically complete without the (seemingly embedded) HT:

| Dice | que | le | ha | cogido | la | explosión | de | lleno. |

| says | that | cldat | has | taken | the | explosion | of | full |

| ‘S/He says that the explosion has caught it in full.’ | ||||||||

Moving away from English and Spanish momentarily, as an additional, crosslinguistic piece of evidence symptomatic of the external or, more precisely, extra-sentential nature of HTLDs, it is important to mention the well-known fact that in German, a prototypical example of a V2 language, HTs lead to apparent V3 orders (Ziv 1994; Ott 2015, among others):

| Der | Professor, | sie | lobten | ihn. |

| thenom | professor | they | praised | himacc |

| ‘The professor, they praised him.’ | ||||

| (German, from Ziv [1994: 632, fn. 6]) | ||||

Under the two-sentence analysis pursued here, this is explained away: in the host sentence/CP2, the verb is canonically in the second position, as expected in German (i.e., … [CP2 sie lobten ihn]). The seeming V3 position of the verb in (81) is just illusory; it stems from the fact that der Professor is part of CP1, an independent elliptical copular sentence, juxtaposed to CP2.

Lastly, Bulgarian cliticization facts further support this conclusion. Bulgarian is a language which normally displays enclitics (postverbal clitics), (82)a, unless a preverbal element occurs that supports the clitic, yielding proclisis (preverbal clitics), (82)c. In other words, Bulgarian obeys Wakarnegel’s law, forcing unstressed pronouns to occur in syntactic second position.

| Vidjax | ja. |

| saw | clacc |

| ‘I saw her.’ |

| *Ja | vidjax. |

| clacc | saw |

| Otnovo | ja | vidjax. | |

| again | clacc | saw | |

| ‘I saw her again.’ | |||

| (Bulgarian, from Avgustinova [1994]) | |||

Crucially, a HT is not sufficient to support the clitic, that is, a HT does not qualify as the first syntactic element in the sentence, leading to enclisis in such cases (contra the judgments reported in Krapova and Cinque 2008):

| Az, pokanixa | me | ošte | včera | na | sreštata. |

| Inom invited | clacc | already | yesterday | to | the reunion |

| ‘Me, they invited me yesterday (already) to the reunion.’ | |||||

| (Bulgarian, Roumyana Slabakova, pers. comm.) | |||||

This follows naturally from the paratactic account advocated here: the pronominal HT az is in a separate sentence (CP1), and therefore the clitic me cannot be the first element in CP2; it needs to occur postverbally, in second position in CP2. Superficially, however, in an example like (83) the clitic seemingly occurs in third position, but in reality, it is the second element in its own sentence (CP2) (i.e., … [CP2 pokanixa me …]). Under monosentential proposals, locating the HT in a high, left-peripheral CP-related projection would lead to the expectation that the HT should serve to support the clitic, contrary to fact.[25]

Overall, the evidence regarding complementizers, V3 configurations, as well as clitic placement point to the conclusion that HTLDs are extra-sentential elements, exactly as argued under the bisentential analysis.

3.1.6 Insensivity to islands and islanhood

As noted in Section 2 in relation to examples like (17) and (18), one of the hallmarks of HTLDs is the well-documented fact that they do not obey islands. The examples therein focused on the coordinate structure constraint. That HTs are not sensitive to islands is shown again for [adjunct islands] in (84):

| Me k, my ex didn’t go to London [because I k live there]. |