Abstract

This paper experimentally investigates the two generalizations for multiple sluicing (MS) recently presented by Klaus Abels and Veneeta Dayal: first, that wh-remnants must have clausemate correlates in the antecedent utterance and, second, that wh-remnants in MS can have correlates in the antecedent clause that are contained in a strong syntactic island. The fact that MS displays both of these properties is puzzling since island insensitivity under sluicing favors a non-sententialist approach to MS, while the clausemate requirement on MS is most straightforwardly explained by postulating a silent structure at the ellipsis site. Even though the clausemate condition has been reported in several languages, no experimental work has been conducted so far to examine its precise effects on the acceptability of MS constructions. In this paper, I will present the results of a series of experiments in German, English, and Spanish (employing both acceptability judgment tasks and a self-paced reading task), where the factors of clausemateness and islandhood have been examined systematically. The results provide solid cross-linguistic support for Abels and Dayal’s generalizations by showing that multiple sluices originating from islands and non-islands are equally acceptable and do not exhibit online processing differences. Furthermore, the acceptability judgment tasks show a significant degradation in acceptability when the correlates in the antecedent do not stem from the same finite clause, thus violating the clausemate condition. I will interpret these results as supporting a particular strand of sententialist research known as the island evasion approach and, in particular, defend that MS is derived from a non-isomorphic short source sluice.

1 Theoretical background

There has been a perennial debate across generative linguistic frameworks about whether seemingly non-sentential utterances, such as fragment answers and sluicing configurations, are genuinely non-sentential (non-sententialism) or instead are elliptical sentences (sententialism). The most prominent contemporary sententialist position – the PF-deletion approach (e.g., Merchant 2001, 2004; Ross 1969) – assumes that sluices are merely standard interrogative clauses to which a superficial phonological deletion operation applies (1a).[1] Conversely, non-sententialist approaches (e.g., Culicover and Jackendoff 2005; Ginzburg and Sag 2000; Sag and Nykiel 2011) assume that sluiced wh-phrases are genuine syntactic orphans and suggest that the sluice is either indirectly licensed or directly interpreted by the context provided by the antecedent, as in (1b).

| Larissa | ist | fröhlich, | weil, | David | jemandem | gratuliert | hat, |

| Larissa | is | happy | because | David | someone.dat | congratulated | has |

| aber | ich | weiß | nicht … | ||||

| but | I | know | not |

| wem i |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| who.dat | Larissa | is | happy | because | David | congratulated | has. |

| wem. |

| who.dat |

Multiple sluicing (MS) configurations – clausal ellipsis involving two or more adjacent wh-interrogative phrase remnants (Abels and Dayal 2017, 2022; Takahashi 1994) – as in (2) represent a particularly interesting lens through which to assess the efficacy of these two different theories, as they display two properties that do not appear to be natural bedfellows under either theory, namely clausemateness and island-insensitivity.

| Ben will be mad [ island if every student talks to one of the teachers], but he just couldn’t remember which student to which teacher. |

Clausemateness refers to the fact that the wh-remnants must have correlates in the antecedent clause that occupy the same finite clausal domain.[2] In (2), this clausemate condition is obeyed, as the correlates every student and to one of the teachers occupy the same adverbial clause. Island-insensitivity alludes to the fact that, in MS configurations such as (2), having island-bound correlates causes no degradation in acceptability, at least when the island in question is a sentential island.

Non-sententialism naturally accounts for island-insensitivity since the absence of silent linguistic structure at the sluicing-site precludes island violations. Nevertheless, the clausemate condition does not fall out straightforwardly from a non-sententialist account, and therefore, these antecedent accessibility constraints would require encoding into the extant matching conditions on remnants. But this leads to a conceptual problem: if we can encode such accessibility constraints for clausemateness, then why not for islands? On the other hand, sententialism can explain the clausemate condition with relative ease; see, e.g., Abels and Dayal’s 2022 scopal-movement account or Lasnik’s (2014) rightward focus extraposition account. Nevertheless, under sententialist approaches, island-insensitivity is harder to explain since the underlying syntactic structure should observe the same constraints imposed for regular wh-movement. One popular way to explain the observed island-insensitivity is to invoke the notion of island-repair. Working under the assumption that ellipsis sites and their antecedents must be structurally isomorphic, the island-repair approaches propose that any markers of ungrammaticality present in a pre-sluice[3] that arise through island-violating movements are eliminated when ellipsis applies (see, e.g., Fox and Lasnik 2003; Merchant 2008; Ross 1969). This approach, however, has attracted much criticism, as it requires island-repair to be selective, i.e., the repair is postulated to occur when island-insensitivity is attested but is postulated not to occur when island-sensitivity is observed. For instance, unlike simplex and multiple sluicing, contrast sluicing (e.g., Griffiths and Lipták 2014; Merchant 2008) and sprouting (Chung et al. 1995; Yoshida et al. 2013) have been argued not to repair islands by deletion. This tends toward unfalsifiability, leading to Stainton (2006: 139) characterizing island-repair as a “get-out-of-counterexample-free card.” Also, island-repair seems incapable of salvaging many cases of island-violating movement that one might expect should be salvaged. For instance, ellipsis fails to repair the unacceptability of the multiple wh-questions under sluicing as in (3), even though it should if we were to assume that island-repair was a real grammatical phenomenon.[4]

| *Every businessman wants an expensive watch, but I don’t know which businessman how expensive. |

A more promising sententialist solution to the current paradox (namely, that MS is subject to a clausemate condition yet usually exhibits island-insensitivity) is encapsulated in the island-evasion approach (see, e.g., Abels 2011; Barros et al. 2014; Merchant 2001). This approach jettisons the assumption that ellipsis sites and their antecedent must be structurally isomorphic, thus yielding the possibility that ellipsis sites can ‘evade’ islands simply by exhibiting a syntactic structure that contains no island in the first place. Possible island-evading sources are pseudosluices,[5] which are copular clauses (e.g., They will hire someone who speaks a certain Balkan language, but I can’t remember which one

it is

) (see, e.g., Barros 2014; Merchant 2001; Vicente 2018; cf. Erteschik-Shir 1973), or short sources, which are non-copular clauses that usually correspond to some subclause in the antecedent (e.g., They will hire someone who speaks a certain Balkan language, but I can’t remember which one

he speaks

). Often, either only a pseudosluice or only a short source will be available as a possible ellipse due to extraneous factors, such as the morphological case-marking on the remnant(s) or the available interpretation of the elliptic clause (Abels 2011; Merchant 2001; see also, Grewendorf and Poletto 1991). The example in (4) shows the potential non-isomorphic pre-sluices and the fact that case-marked wh-phrases are incompatible with a copular source.[6]

| Larissa | ist | fröhlich, | weil | David | jemandem | gratuliert | hat, |

| Larissa | is | happy | because | David | someone.dat | congratulated | has |

| aber | ich | weiß | nicht … | ||||

| but | I | know | not |

| ?*wem i | es | war | t i . | | | *wem j | er | war | t j . |

| who.dat | it | was | who.dat | he | was |

| wem i | David | t i | gratuliert | hat. |

| who.dat | David | congratulated | has. |

Conceptually, the island-evasion is preferred over the island-repair analysis, as the former, unlike the latter, requires no appeal to a sui generis repair process. Moreover, the island-evasion approach has empirical advantages, too. First, non-isomorphic elliptic clauses are needed independently in sententialist fragments to derive the correct interpretations for cases such as (5) and (6) (see, e.g., Merchant 2001; Rudin 2019; Thoms 2013; Vicente 2015).

|

I

will

fix the car as soon as I work out how { |

| (adapted from Merchant 2001: 22) |

|

Sally

has

a new boyfriend, but we don’t know who { |

| (adapted from Barros and Vicente 2016: 60) |

Furthermore, the island-evasion approach makes the prediction that when no suitable island-evading elliptical clause is available, island-sensitivity arises (cf. Barros and Frank 2022, see also discussion in Section 3). This prediction is borne out, as the examples in (7) and (8) show. As a matter of fact, neither of the strike-through short paraphrase continuations produce an acceptable pre-sluice.

|

*They hired a hard worker, but I don’t know how hard {

|

| (adapted from Barros and Vicente 2016: 62) |

|

*They didn’t hire anyone who speaks a Balkan language, but I can’t remember which [one] { |

| (adapted from Merchant 2001: 211) |

The idea that elliptical clauses can be structurally non-isomorphic to their antecedents has also had an impact sententialist research into MS, where the notion that ellipsis sites are short sources has found much favor (e.g., Abels and Dayal 2017, 2022; Lasnik 2014; Marušič and Žaucer 2013; Merchant 2001). The above-mentioned authors thus propose that MS sentences like (9) have (9a) as their pre-sluice version instead of (9b). Furthermore, evidence is now accruing from experimentally oriented studies that MS favors a short source interpretation in German (Cortés Rodríguez in prep; Cortés Rodríguez and Griffiths 2022).

| The teacher knew that every kid played with some toy, but I just don’t know which kid with which toy. |

| …which kid played with which toy |

| …which kid the teacher said that played with which toy. |

If this short source analysis is indeed correct, it can be predicted that, regarding MS, the languages[7] examined here will not disclose acceptability differences regarding island-sensitivity. As a matter of fact, both non-island[8] (10a) and island (10b) containing multiple sluices would stem from the same pre-sluice, namely (10c).

| My father said that everyone laughed at something, but I just don’t know who at what. |

| My father was happy because everyone laughed at something, but I just don’t know who at what. |

| … who laughed at what. |

In summary, Abels and Dayal’s 2022 claims lend significant support for a PF-deletion-style sententialist approaches to (multiple) sluicing that permit ellipsis sites to display syntactically non-isomorphic sources to their antecedents. However, Abels and Dayal’s generalizations about the existence of a clausemate condition in MS and about the island-insensitivity of MS configurations are based primarily on informally collected judgments. Since English judgments about MS configurations are highly variable (Kotek and Barros 2018; Lasnik 2014; Merchant 2001), and because MS judgments are subtle in general (Cortés Rodríguez under review), these claims need independent empirical verification. Moreover, to ensure that Abels and Dayal’s claims are generalizable, cross-linguistic experimental validation is required. This paper provides this verification by reporting the results from a set of experiments in which (i) proper experimental methodologies were employed and (ii) tests were conducted across languages.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents three parallel acceptability judgment studies in three languages – German, English, and Spanish – investigating experimentally the two generalizations presented in Abels and Dayal (2017, 2022). In other words, those three studies test the contrast between correlates originating inside an island or a non-island and examine the difference between correlates in the antecedent originating as clausemates or in boundary-separated clauses. This section also presents a follow-up study in German using a self-paced reading. In Section 3, I discuss the experimental results and argue that those results are compatible with a short source identity approach to multiple sluicing. Additionally, I argue that some of the counterexamples to the short source approach presented in the literature (see Barros and Frank 2016, 2017, 2022) either fail to have cross-linguistic support, or they can be reanalyzed as actual short sources. I conclude in Section 4 that the empirical evidence presented here supports Abels and Dayal’s two generalizations for multiple sluicing, and I will defend that these results are indicative of the underlying structure at the sluice to be short source; in other words, a short paraphrase of the antecedent which does not contain an island at the sluicing-site.

2 Experimental evidence

In this section, I provide experimental evidence supporting the two generalizations for MS introduced in Abels and Dayal (2017, 2022): (i) all wh-remnants must originate inside the same finite clause, and (ii) correlates in the antecedent can originate from within an island. I investigate these two generalizations in three different languages. The languages used for investigation are single-wh-fronting; hence, they form standard multiple wh-questions by fronting one of the wh-phrases and leaving the others in situ. This derivation is also possible in embedded contexts. German, English, and Spanish allow (to some degree) long-distance wh-movement out of that-clauses, as the ‘a’ examples in (11)–(13) show.[9] However, such wh-fronting is impossible when the wh-phrase originates inside an island and moves to a sentence-initial position, as this will incur an island violation. See the ‘b’ examples in (11)–(13).

| %Wer 1 | meinte | Angela, | (dass) | t 1 | wen | geküsst | hat? |

| who.nom | thought | Angela | that | who.acc | kissed | has |

| *Wer 2 | war | Angela, | böse | weil | t 2 | wen | geküsst | hat? |

| who.nom | was | Angela | angry | because | who.acc | kissed | has |

| %Who 1 did Angela think (that) t 1 kissed who(m)? |

| *Who 2 did Angela get angry because t 2 kissed who(m)? |

| %¿Quién 1 | pensó | Angela | que | t 1 | besó | a | quién? |

| who | thought | Angela | that | kissed | DOM | has |

| *¿Quién 2 | se | enfadó | Angela, | porque | t 2 | besó | a | quién? |

| who. | refl | got.angry | Angela | because | kissed | DOM | who |

Nevertheless, both that-clauses and because-islands seem to be valid embedding clauses in the antecedent of MS. As long as the correlates are inside the same clause, multiple sluicing should be possible (Abels and Dayal 2017, 2022). This prediction also finds empirical support in simple sluicing in English, where experimental results show no difference for correlates positioned in a that-clause or a because-island (Yoshida et al. 2013). Yet, no in-depth investigation has been conducted concerning MS and its island insensitivity. Given the clausemate constraint presented above, and assuming that, same as in simplex sluicing, complex-antecedent multiple sluicing (caMS) is also acceptable to a comparable extent regardless of whether the embedded clause in the antecedent is a complement-clause or an adjunct-island, the two generalizations of Abels and Dayal’s (2017, 2022) seem to be correct. As those generalizations have not yet been tested experimentally, and in order to make them generalizable, I have conducted three acceptability judgment studies to investigate them. The predictions for these experiments are directly derived from Abels and Dayal’s (2017, 2022) two generalizations for multiple sluicing:

Predictions

| Prediction 1 |

| caMS constructions where all the correlates originate within the same clause, i.e., as clausemates, are more acceptable than where the correlates are separated by a (tensed) clause boundary. |

| Prediction 2 |

| caMS constructions allow correlates to originate inside an island to the same extent as when the correlates originate in an embedded non-island clause. The acceptability is not predicted to be dependent on the type of embedded clause in the antecedent; therefore, no difference is predicted between island and non-island conditions. |

| Prediction 3 |

| For Predictions 1 and 2 to be generalizable, they must find cross-linguistic support. For this reason, the same experiment was conducted in three different languages, namely German, English, and Spanish, where analogous results are expected. |

2.1 Experiment 1 | Acceptability judgment task: multiple sluicing in German boundary and islandhood

2.1.1 Methods

2.1.1.1 Design and materials

I constructed 24 sentence quadruplets containing multiple sluicing using a 2 × 2-design with boundary and islandhood as within-item and within-subject factors. boundary was controlled to represent two levels clausemate and across, indicating whether the correlates in the antecedent originate within the same finite clause or across clause boundaries, respectively. islandhood also represented two different levels: first, island describes the items that contain an adjunct island – specifically a weil-island (‘because-island’) – as their embedded clause in the antecedent; secondly, non-island characterizes the instances where the embedded clause is a dass-clause (‘that-clause’).

Each experimental sentence consists of three parts: antecedent, intro, and sluice. The antecedent is formed by two clauses, namely the matrix clause and the embedded clause, where the embedded clause encompasses either an island or a non-island configuration. There are two quantifiers in the antecedent. The first quantifier has a universal force, and the second one has an existential character, following the pattern ∀ → ∃. Thus, the universal quantifier takes surface scope over the existential quantifier (see Merchant 2001; Nishigauchi 1998). It is worth noting that the initial correlate is a nominal phrase, and the second correlate is prepositional (Lasnik 2014; cf., Cortés Rodríguez under review; Richards 2010). Additionally, while all the initial correlates comprised an animate entity, in the second correlate, half of the items contained an animate entity jemanden/jemandem (‘someone.acc/someone.dat’), and the other half consisted of an inanimate entity etwas (‘something’).[10] An example item is provided in (17):

| Simon | berichtete, | dass | jeder | an | etwas | [clausemate, non- island] |

| Simon | reported | that | everyone | about | something |

| gedacht | hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | wer | an | was. | ||

| thought | has | but | I | know | not | who | about | what |

| Simon | war | begeistert, | weil | jeder | an | etwas | [clausemate, island] |

| Simon | was | reported | because | everyone | about | something |

| gedacht | hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | wer | an | was. | |

| thought | has | but | I | know | not | who | about | what |

| Jeder | berichtete, | dass | Simon | an | etwas | [across, non-island] |

| everyone | reported | that | Simon | about | something |

| gedacht | hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | wer | an | was. | ||

| thought | has | but | I | know | not | who | about | what |

| Jeder | war | begeistert, | weil | Simon | an | etwas | [across, island] |

| everyone | was | reported | because | Simon | about | something |

| gedacht | hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | wer | an | was. | |

| thought | has | but | I | know | not | who | about | what |

All items were distributed across four lists according to the Latin square design and randomized within each list. Participants saw a total of 6 items in each condition. In addition to the 24 critical items, 72 fillers were included. Fifteen out of those filler sentences corresponded to the 5-degree standardized items from Featherston (2009), which range from A-type fillers (most natural) to E-type fillers (least natural) to ensure proper scale usage and allow for comparison.

2.1.1.2 Participants and procedure

An acceptability judgment task was designed using PsychoPy 3 experiment creation application (Peirce et al. 2019). Thirty-two self-reported native German speakers (mean age = 31.8, sd = 9.73) were recruited via the Prolific [11] platform, and they were all naive with respect to the purpose of the experiment. Participants were asked to rate the naturalness of sentences on a 7-point scale, from 1 (very unnatural) to 7 (very natural). Additionally, they were also instructed that there is no “right” or “wrong” answer and that they should follow their own intuitions. Participants received monetary compensation of £3.00 for their participation in this study lasting approximately 15 min. Based on the judgments given by the participants to the standardized items (Featherston 2009), 3 participants were excluded for misusing the rating scale; therefore, 29 participants entered the statistical analysis. Finally, before starting to judge the experimental items, every participant had a practice round with five sentences. Overall, a total of 96 items were presented in each trial, and within a session, critical items and filler sentences were ordered randomly.

2.1.2 Data analysis and results[12]

The judgment data were analyzed employing a cumulative link mixed model (CLMM) using the ordinal package (Christensen 2019) from the statistics software R, Version 4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020). The model with the best fit for the data was selected using a manual backward model section process; thus, starting with the full model, which included all experimental factors and interactions as fixed effects, as well as random effects for items and subjects with maximal random slopes and their interactions. I included the model that would converge with the most complex random effect structure (Barr et al. 2013). Should the model fail to converge, the model structure would be simplified gradually. Here, I report the model with the best maximal random effect structure supported by the data, and the corresponding formula is included in the table with the statistical analyses. Finally, the p-values are estimated via maximum likelihood using the Laplace approximation.

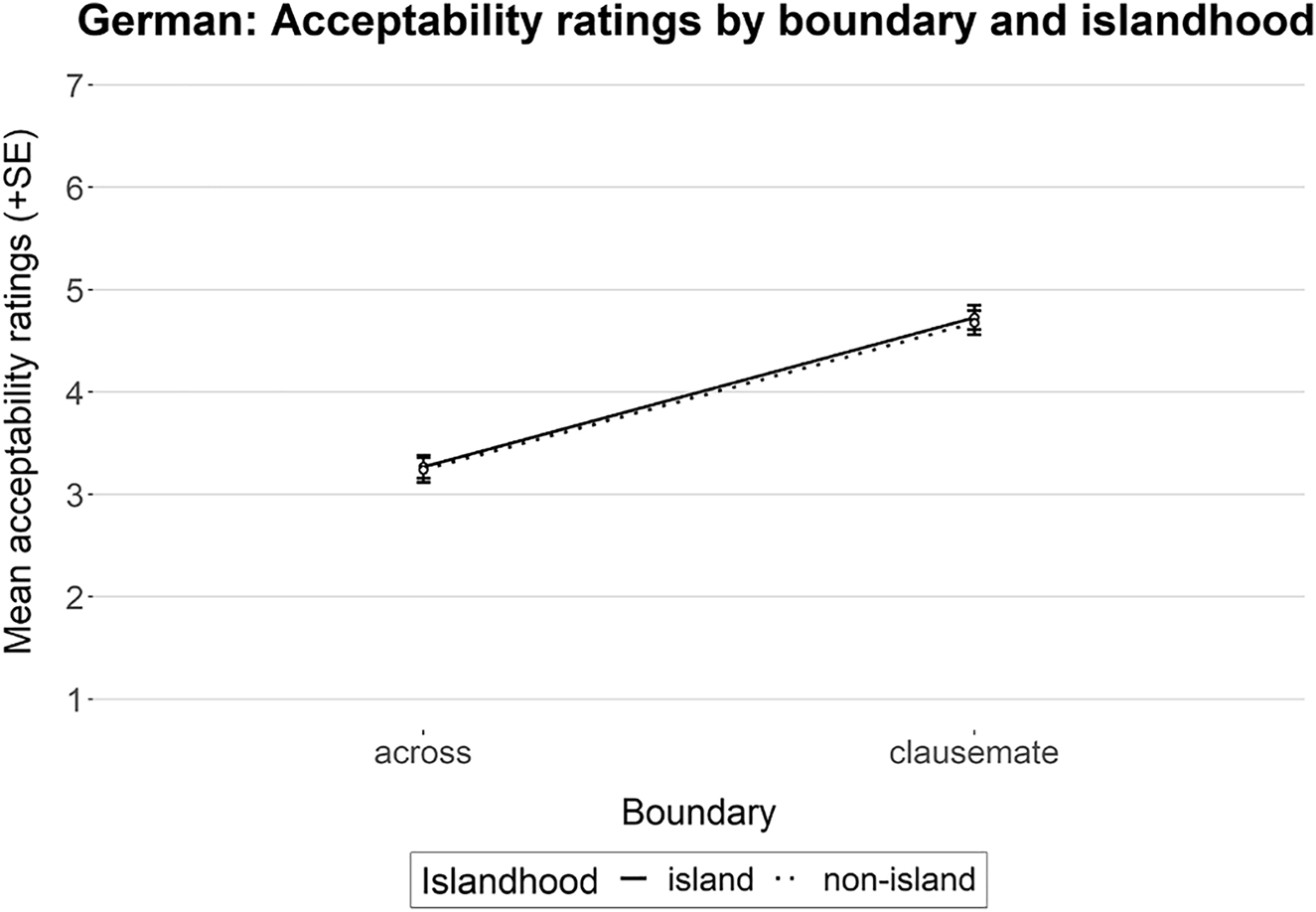

Figure 1 shows the mean acceptability ratings obtained for this experiment, and the results of its statistical analysis are presented in Table 1. The model yielded a main effect for boundary, where MS sentences with clausemate correlates were judged significantly more acceptable than those with each correlate separated by a clause boundary. There was no main effect for islandhood; therefore, whether the embedded clause in the antecedent constituted an island or a non-island did not make a difference. The interaction between the factors was also not significant.

Mean acceptability rating (n = 29). Error bars show standard error.

Cumulative Link Mixed Model fitted with the Laplace approximation.

| Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| boundary | −3.04969 | 0.58594 | −5.205 | 1.94e−07*** |

| islandhood | 0.11030 | 0.14946 | 0.738 | 0.461 |

| boundary:islandhood | 0.05082 | 0.29658 | 0.171 | 0.864 |

-

Formula: rating ∼ boundary * islandhood + (boundary * islandhood | subject) + (boundary * islandhood | item).

The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p<.05 = *; p<.01 = **; p<.001 = ***.

2.2 Experiment 2 | Acceptability judgment task: multiple sluicing in English boundary and islandhood

2.2.1 Methods

2.2.1.1 Design and materials

Following the same design as in Experiment 1, I constructed 24 quadruplets containing multiple sluicing using a 2 × 2-design with boundary (across and clausemate) and islandhood (island and non-island) as within-item and with-subject factors. For the English experiment, I use the same adjunct island type as in the German experiment, namely a because-island. The experimental sentences were constructed following the same pattern described in Experiment 1. An example item is provided in (18):[13]

| Linda remembered that everyone prepared for something, but I just don’t know who for what. | [clausemate, non- island] |

| Linda was moved because everyone prepared for something, but I just don’t know who for what. | [clausemate, island] |

| Everyone remembered that Linda prepared for something, but I just don’t know who for what. | [ across, non- island] |

| Everyone was moved because Linda prepared for something, but I just don’t know who for what. | [across, island] |

Item and filler distribution followed the same principle as Experiment 1. The only difference in this experiment concerned the 15 standardized items, which in this case were taken from Gerbrich et al. (2019).

2.2.1.2 Participants and procedure

The procedure used in this experiment is the same as for the MS experiment in English presented above, except that all the instructions in the experiment were presented in English. Thirty-two self-reported native speakers (mean age = 30.7, sd = 11.69) of English residing either in the UK or the USA participated in the experiment. Based on participants’ ratings for the standardized items (Gerbrich et al. 2019), 5 participants were excluded; thus, 27 participants entered the statistical analysis.

2.2.2 Data analysis and results

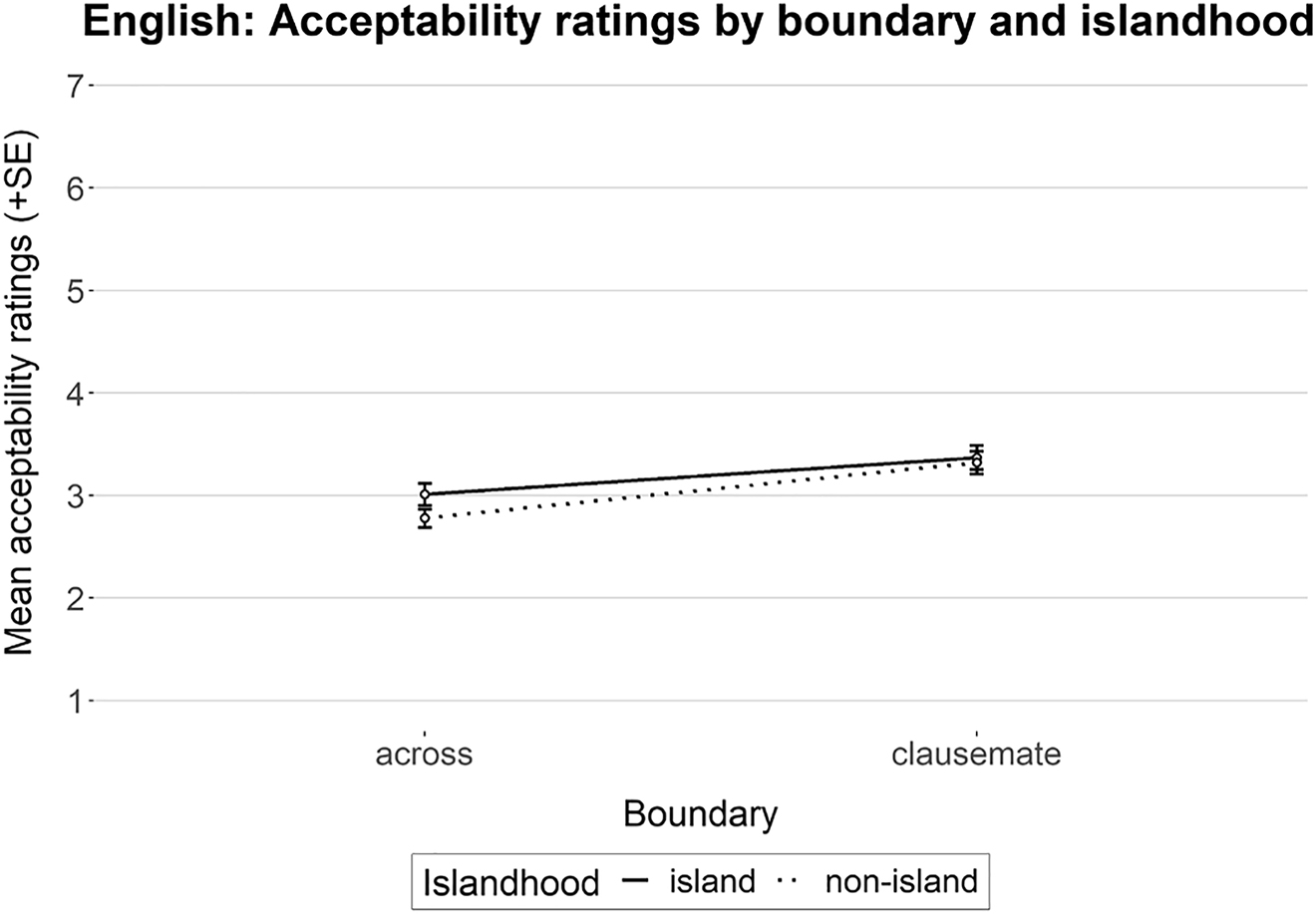

The experimental data were analyzed following the same procedure as in Experiment 1. Figure 2 shows the mean acceptability ratings obtained for Experiment 2, and its statistical analysis is given in Table 2. The results are comparable to those found in Experiment 1. The model yielded only one main effect for boundary, whereby clausemate correlates were judged as significantly more acceptable than correlates positioned across a clause boundary. There was no main effect for islandhood, nor an interaction between the factors.

Mean acceptability rating (n = 27). Error bars show standard error.

Cumulative Link Mixed Model fitted with the Laplace approximation.

| Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| boundary | −1.0831 | 0.3586 | −3.020 | 0.00252** |

| islandhood | 0.3324 | 0.2317 | 1.435 | 0.15140 |

| boundary:islandhood | 0.1131 | 0.4323 | 0.262 | 0.79360 |

-

Formula: rating ∼ boundary * islandhood + (boundary * islandhood | subject) + (boundary * islandhood | item). The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p<.05 = *; p<.01 = **; p<.001 = ***.

2.3 Experiment 3 | Acceptability judgment task: multiple sluicing in Spanish boundary and islandhood

2.3.1 Methods

2.3.1.1 Design and materials

Experiment 3 followed the same design as in Experiments 1 and 2.[14] Another 24 experimental items were constructed following a 2 × 2-design with boundary (across and clausemate) and islandhood (island and non-island) as within-item and with-subject factors. The island was represented by the adjunct island as in the experiments above, i.e., porque-island (‘because-island’). The non-island level is described by a que-clause (‘that-clause’). The construction of the experimental sentences followed the same pattern as in Experiments 1 and 2. An example item is provided in (19):

| Marta | sospechó | que | alguien | mintió | sobre | [clausemate, non- island] | |

| Marta | suspected | that | someone | lied | about |

| algo, | pero | no | sé | quién | sobre | qué. | ||

| something | but | not | know.1.sg | who | about | what |

| Marta | estaba | decepcionada | porque | alguien | mintió | [clausemate, island] |

| Marta | was | disappointed | because | someone | lied |

| sobre | algo, | pero | no | sé | quién | sobre | qué. | |

| about | something | but | not | know.1.sg | who | about | what |

| Alguien | sospechó | que | Marta | mintió | sobre | [across, non- island] | ||

| someone | suspected | that | Marta | lied | about |

| algo, | pero | no | sé | quién | sobre | qué. | ||

| something | but | not | know.1.sg | who | about | what |

| Alguien | estaba | decepcionado | porque | Marta | mintió | sobre | [across, island] |

| someone | was | disappointed | because | Marta | lied | about |

| algo, | pero | no | sé | quién | sobre | qué. | |||

| something | but | not | know.1.sg | who | about | what |

All items and fillers followed the same distribution as Experiments 1 and 2. Additionally, I created 15 items to emulate the 15 standardized items used in previous experiments (Featherston 2009; Gerbrich et al. 2019). I adapted sentences labeled with different grammaticality labels in the literature to create five different degrees of acceptability.

2.3.1.2 Participants and procedure

Experiment 3 followed the same procedure as Experiments 1 and 2, but in this case, all items and instructions were presented in Spanish. Twenty-eight self-reported native speakers (mean age = 25.5, sd = 7.94) of Spanish residing in Spain participated in the experiment. One participant was excluded for misusing the rating scale; therefore, a total of 27 participants entered the statistical analysis.

2.3.2 Data analysis and results

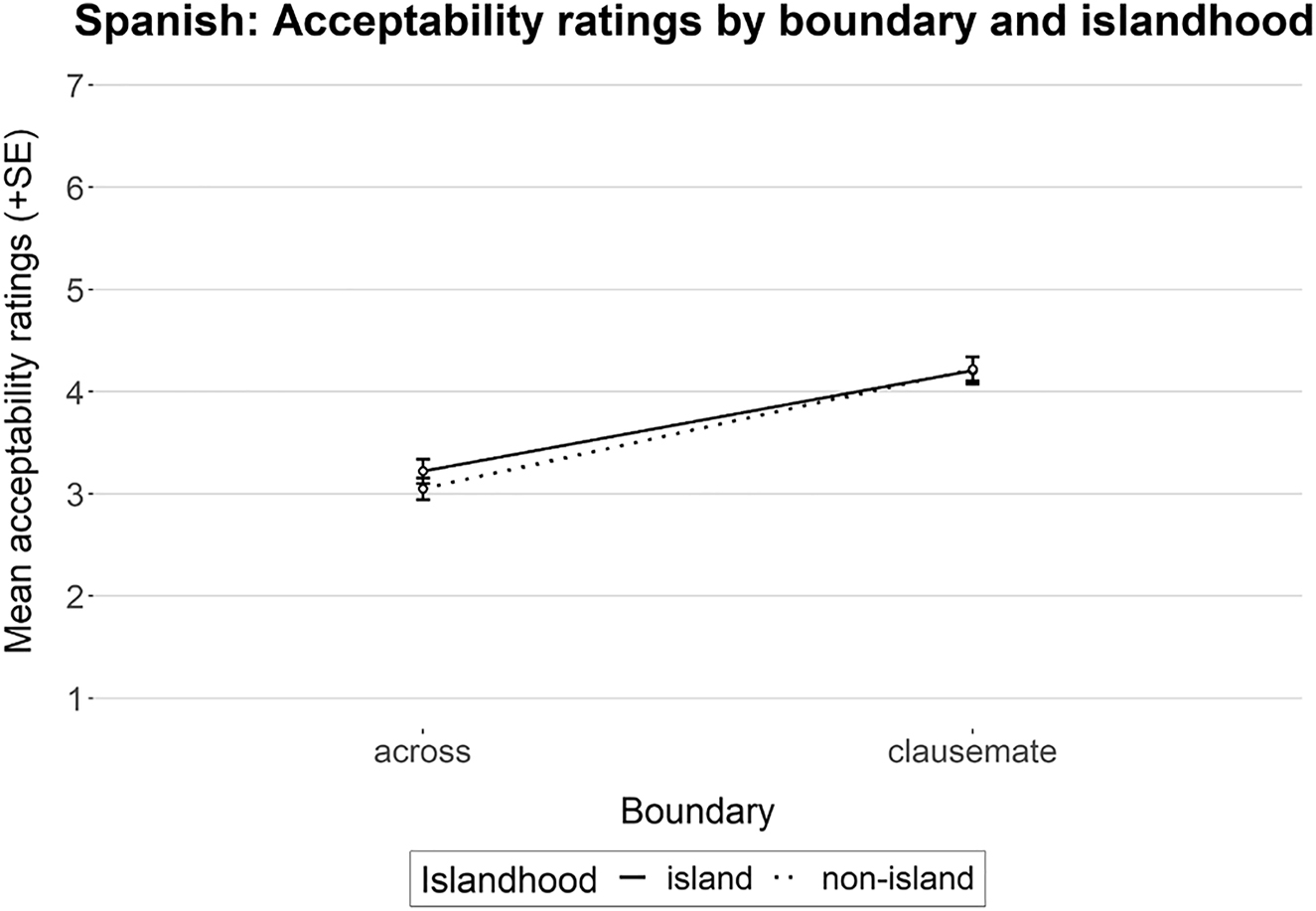

Data were analyzed following the same statistical procedure as in Experiments 1 and 2. Figure 3 shows the mean acceptability ratings obtained for Experiment 3, and its statistical analysis is given in Table 3. The results showed a highly significant effect for boundary: clausemate conditions received higher ratings than across conditions. No main effect was obtained for islandhood, and the interaction between the factors was not significant either.

Mean acceptability rating (n = 27). Error bars show standard error.

Cumulative Link Mixed Model fitted with the Laplace approximation.

| Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| boundary | −2.41369 | 0.50357 | −4.793 | 1.64e−06*** |

| islandhood | 0.05551 | 0.18931 | 0.293 | 0.769 |

| boundary:islandhood | 0.24455 | 0.36316 | 0.673 | 0.501 |

-

Formula: rating ∼ boundary * islandhood + (boundary * islandhood | subject) + (boundary * islandhood | item).

The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p<.05 = *; p<.01 = **; p<.001 = ***.

2.4 Experiment 4 | Self-paced reading study: multiple sluicing in German antecedent type

Despite having obtained the predicted null differences for island insensitivity in Experiments 1, 2, and 3, I conducted a follow-up online experiment with another island type – subject island – to show that the lack of differences found in the offline acceptability data is indeed a stable effect. This online experiment investigates, in particular, the claims in Abels and Dayal (2017, 2022) that MS is possible even in cases where the correlates originate inside an island. To investigate whether this prediction holds for different islands as well as non-islands, I compared the reading times for the resolution of wh-elements when their correlates originate in three contrasting antecedents.

2.4.1 Methods

2.3.4.1 Design and materials

The material for this self-paced reading study resembles the one presented in the acceptable judgment study in Section 3.1 with the necessary methodological adaptations. Fifteen sentence triplets were constructed following a univariate within-item and within-subject design. Each experimental item consists of three sentences. The manipulated factor was antecedent type, representing three levels: noIsland, the embedded clause is a that-clause, weilIsland, the embedded clause is a because-adjunct-island, and subjectIsland, the antecedent is a sentential subject, thus a subject-island. The structure of the items followed this pattern: the first sentence was the context, namely the antecedent, which was presented as a single chunk. The antecedent contained two bare quantifiers (in every case, the universal quantifier taking surface scope over the existential quantifier). Moreover, there were three types of antecedents comprised either by a matrix and an embedded clause – the latter featuring a that-clause or a because-island – or a matrix clause with a sentential subject.

The second sentence conveys the intro and the sluice in a preposed [15] configuration. The two wh-remnants appear preceded by aber (‘but’) and followed by weiß ich nicht (‘I don’t know’). The last sentence presents material that provides additional information about the event which is not relevant to the purpose of the experiment. The region of interest is the segment including the two wh-elements and the subsequent spill-over region containing the verb weiß of the intro clause. The spill-over region(s) remained equal across items. The segmentation of the regions is displayed by pipes (|) in the example item in (20):

| Olaf | berichtete, | dass | jeder | etwas | im | [noIsland] | ||

| Olaf | reported | that | everyone | something | in.the |

| Fernsehen | anschaut. | |

| television | watched |

| Olaf | ist | aufgeregt, | weil | jeder | etwas | im | [weilIsland] |

| Olaf | is | excited | because | everyone | something | in.the |

| Fernsehen | anschaut. | | ||||||

| television | watched |

| Dass | jeder | etwas | im | Fernsehen | anschaut, | [subjectIsland] |

| that | everyone | something | in.the | television | watched |

| hat | Olaf | aufgeregt. | | ||||

| has | Olaf | excited |

| Aber | | wer was | | weiß | | ich | | nicht. | | [intro+sluice] | |

| but | who what | know | I | not |

| Vermutlich | | werde | | ich | | ihn | | danach | | fragen. | | [continuation] |

| presumably | will | I | him | about.it | ask |

All items were distributed across three lists according to Latin square design, randomized, and presented along with 65 additional filler sentences.

2.3.4.2 Participants and procedure

Thirty-two students of the University of Kassel (mean age = 22.2; sd = 2.91) participated in the experiment for course credit. All participants were native speakers of German and naive with respect to the purpose of the experiment. Participants were invited to the lab to complete a computer-based experiment. The experiment was programmed using the E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA 2016). Sentences were presented visually in the center of a computer screen using a self-paced moving window paradigm (Just et al. 1982). Before the experiment started, participants were instructed to read sentences at a natural pace and to advance from one segment to the following by pressing the spacebar. Each trial started with a fixation star appearing in the center of the screen. After the start, the stimulus appeared. The first sentence (namely the antecedent) was presented as a whole after the fixation star. The remaining sentences were presented segmentwise, i.e., every word was initially covered by a dash. By pressing the spacebar, the dashes revealed words, and the sentence unfolded in a way that the preceding segment changed back to dashes as the following segment appeared. After every sentence, participants had to answer a yes–no comprehension question. These questions served as a method to exclude uncooperative participants. Before the actual experiment started, participants were presented with two sentences as practice trials and were encouraged to ask clarification questions if necessary. The entire procedure lasted approximately 20 min.

2.4.2 Data analysis and results

First, I analyzed the responses given to the comprehension question in order to remove non-collaborative participants. Only those participants with a 75% or higher accuracy were kept for further analysis. This treatment did not lead to the exclusion of any participant. Second, reading times were corrected for outliers. On the one hand, reading times longer than 750 ms and shorter than 100 ms per segment were removed, which led to a data loss of 5.87%. On the other hand, all data points diverging 2.5 standard deviations from the mean per segment and participant were discarded, leading to an additional data loss of 2.19%. All remaining reading times were normalized by log-transformation and analyzed using the statistics software R, Version 4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020). The reading time data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effect model (LMEM) with the lme4 package and the lmer function (Bates et al. 2015). The model included the single experimental factor as a fixed effect and random intercepts for participant and item (since random slopes failed to converge). p-Values were obtained using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. 2017), which uses Satterthwaite’s method.

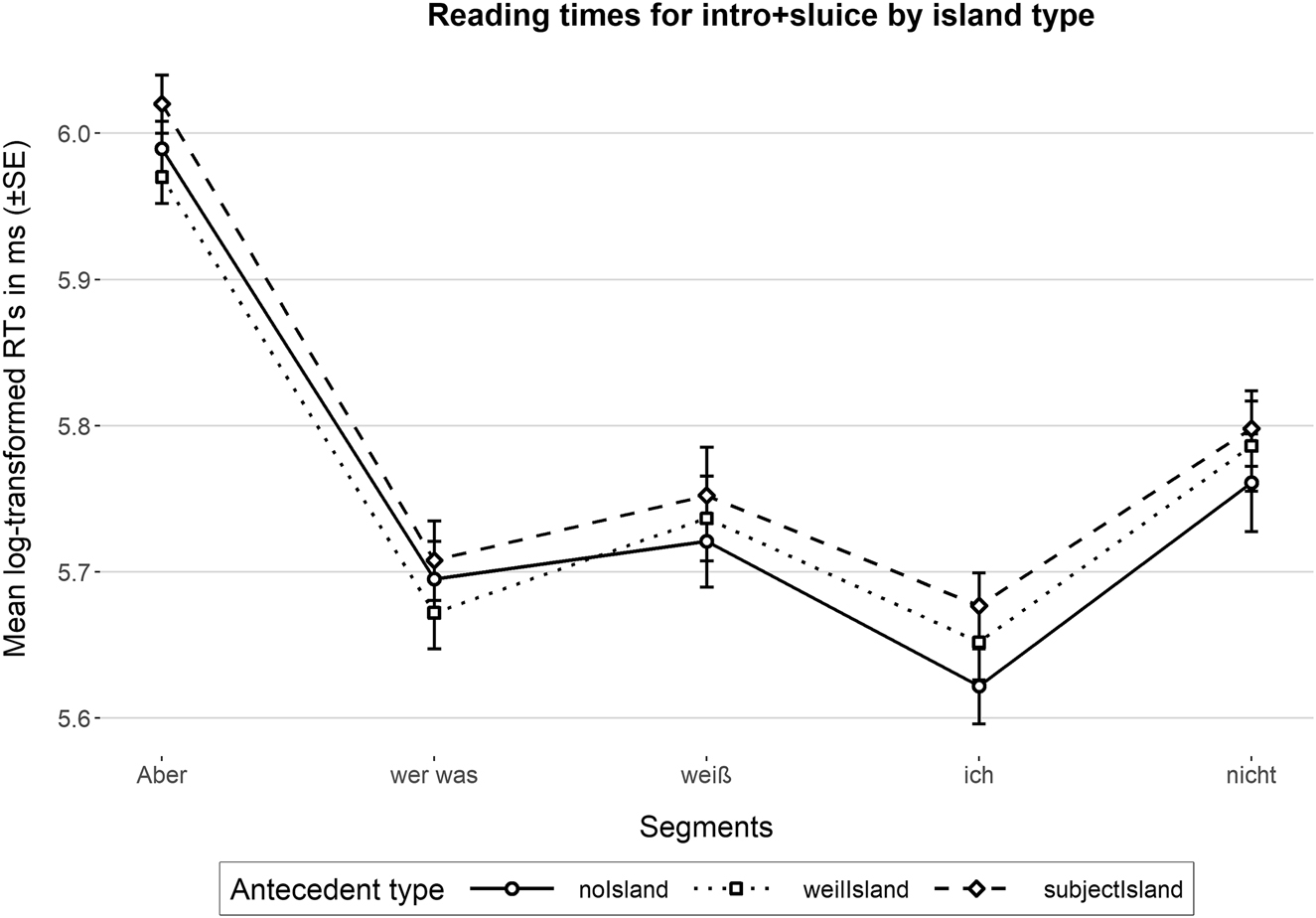

Figure 4 shows the descriptive statistics with the log-transformed mean reading times for the three antecedent types in each segment of the intro + sluice. The full model for the critical region (i.e., the segment in Figure 4 labeled wer was) is provided in Table 4, and the model for the spill-over region (i.e., the segment in Figure 4 labeled weiß) is provided in Table 5. The results showed no significant effects for antecedent type. In other words, reading times were not modulated by the island type. Therefore, regardless of where the correlates in the antecedent originate (that-clause, a because-island, or a subject island), the reading times for the anaphoric wh-pronouns at the sluice did not differ.

Means of log-transformed reading times (n = 32). Error bars show standard error.

Linear Mixed Effect Model fitted by maximum likelihood (critical region).

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.70041 | 0.04286 | 48.11573 | 133.014 | <2e−16*** |

| weiIsland | −0.01716 | 0.02714 | 406.05093 | −0.632 | 0.528 |

| subjectIsland | 0.01111 | 0.02719 | 405.74444 | 0.408 | 0.683 |

-

Formula: logRT ∼ antecedent type + (1 | subject) + (1 | item).

The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p<.05 = *; p<.01 = **; p<.001 = ***.

Linear Mixed Effect Model fitted by maximum likelihood (spill-over region).

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.72680 | 0.04782 | 46.59387 | 119.756 | <2e−16*** |

| weiIsland | 0.01247 | 0.03438 | 391.17068 | 0.363 | 0.717 |

| subjectIsland | 0.02063 | 0.03499 | 393.45066 | 0.590 | 0.556 |

-

Formula: logRT ∼ antecedent type + (1 | subject) + (1 | item).

The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p<.05 = *; p<.01 = **; p<.001 = ***.

3 General discussion

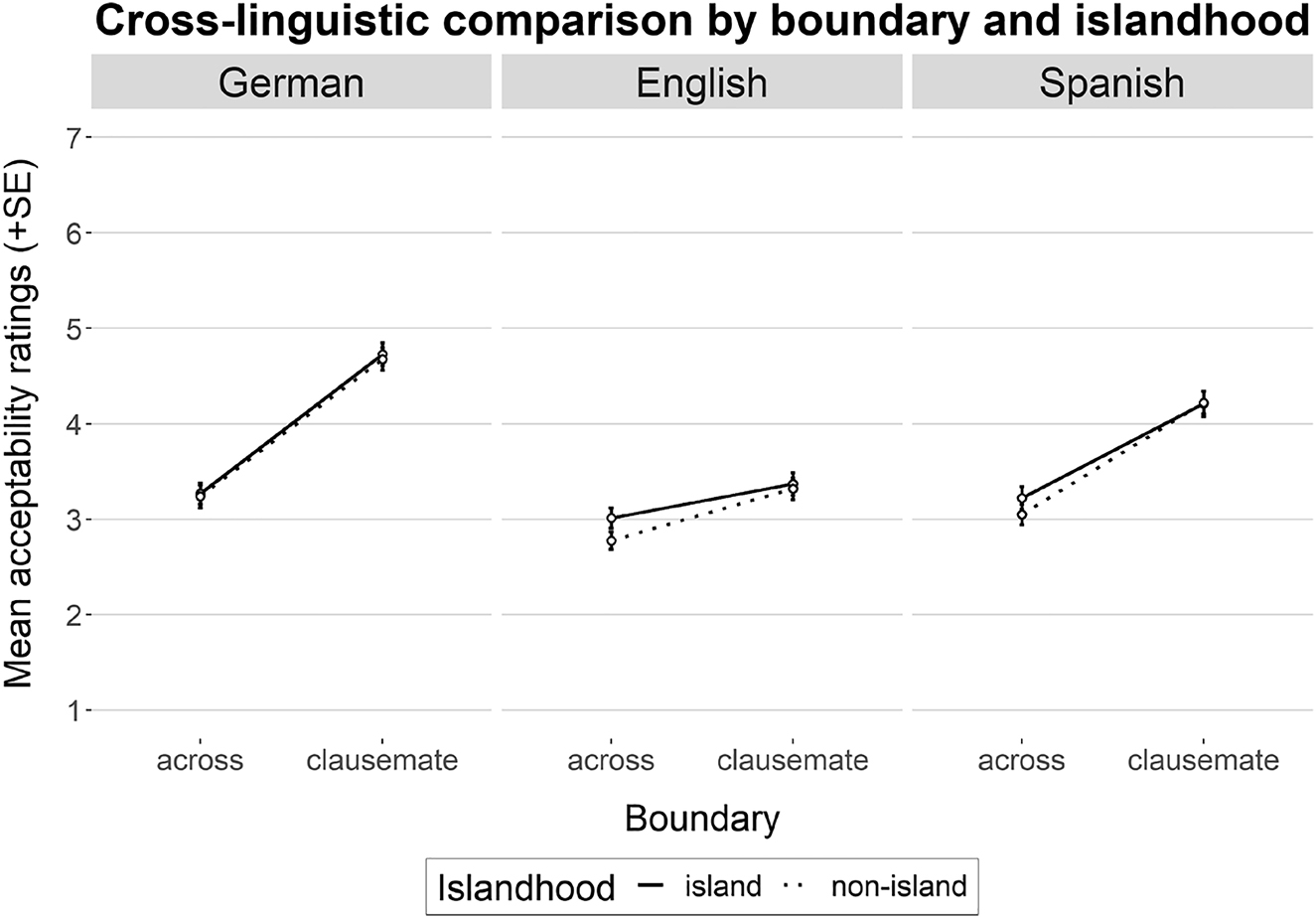

Empirical support has been obtained for the predictions outlined in Section 2. Prediction 1 is borne out since a main effect was obtained in all three experiments for boundary. Conditions with clausemate correlates in the antecedent were judged as more acceptable than conditions where the initial and the non-initial correlate are separated by a clause boundary. Prediction 2 is also borne out; no main effect was observed for the factor islandhood. Multiple sluicing constructions whose remnants originate either in an embedded that-clause (non-island) or an embedded because-adjunct-clause (island) received analogous results. It is important to acknowledge that these interpretations are based on non-significant effects, which could be viewed as problematic given that a prediction based on the lack of differences cannot be tested via hypothesis-testing. Being aware of this limitation, I conducted the same experiment in three languages to show at least that these null differences remain stable across languages. Additionally, I conducted a follow-up self-paced reading experiment in German, where the online data also showed that varying the type of the antecedent does not impact reading times. Lastly, Prediction 3 is also borne out since the results for the three languages display the already-mentioned main effect for boundary, a null effect for islandhood, and the absence of an interaction between the factors. However, it is worth mentioning that, despite the inferential statistics yielding the same effects, the main effect for boundary differs in effect size across languages.

Figure 5 shows the mean acceptability ratings obtained for each of the three experiments. The German ratings are generally higher than those for English and almost on a par with the Spanish ones. The average rating for all German MS conditions is μ = 3.98 (σ = 1.55), which is comparable to the range of standard item C (μ = 4.23, σ = 1.48) (Featherston 2009). English MS, on the other hand, received lower ratings across the board (μ = 3.12 σ = 1.36), therefore scoring lower than the mean for standard items D (μ = 3.44, σ = 1.52) (Gerbrich et al. 2019). Lastly, Spanish MS sentences in this experiment averaged to μ = 3.68 (σ = 1.51). There are no standardized items for Spanish that can be used as a baseline of comparison. The mean results per language are in-line with an observation made in the literature, namely that German accepts MS more readily than English (Merchant 2006; Winkler 2013). The same difference was reported by Cortés Rodríguez (under review) for German and English MS configurations in which the antecedent is monoclausal. Similarly, the means reported for ‘simple antecedent’ MS in Spanish (Cortés Rodríguez 2021) are proportionally higher than those obtained for caMS.[16]

Mean acceptability ratings for multiple sluicing across languages. Error bars show standard error.

The fact that no difference in acceptability arises for multiple sluicing configurations when one varies the structural context of the correlates in the antecedent (such that they are either contained in an island or a non-island) raises many questions about the nature of the sluice. I have defended the position that these results provide evidence for the short source approach, according to which islands are evaded under ellipsis, rather than island-crossing movement being repaired by ellipsis. It should be pointed out that, despite there being independent arguments for the short source approach (see Barros et al. 2014; Merchant 2001), various arguments have been advanced in the literature to suggest that island-insensitivity under clausal ellipsis is still observed when no short source is available (see Lasnik 2001, 2005; Rottman and Yoshida 2013; Yoshida et al. 2015, 2019).

However, the validity of each of these arguments is questionable. I now wish to demonstrate this by focusing solely on counterexamples offered recently by Barros and Frank (2016, 2017, 2022) against the short source approach to MS. These authors offer a pragmatic account of the clausemate condition on MS that revolves around discourse-centering (à la Grosz et al. 1995). They argue that violations of the clausemate condition arise whenever the subject of the embedded clause in caMS is “shifty,” where “shifty” means that the expression is not coreferential with the most prominent discourse referent in the matrix clause and therefore displaces the attention from this expression. Put differently, they claim that the absence of a “shifty subject” in the embedded clause suspends the need for the correlates to be clausemates. For their analysis to have any conceptual bite, there must exist acceptable MS configurations with “non-shifty” embedded subjects and no potential short elliptic source. Although Barros and Frank offer such examples, I believe that, for many such examples, a short analysis is indeed available, contrary to their claim.[17] For example, Barros and Frank correctly observe about (21a) that the short source ‘…which student was a problem with which professor’ is unavailable in this context (as it yields incongruity). However, they fail to notice that the short source presented in (21b) is readily available and yields a congruous utterance, as one can easily accommodate the inference that the problem being claimed to exist by the student is a problem that the student her/himself has with the professor. When the context no longer permits such inferences to be made, and thus the short source becomes unavailable, the same MS configuration is judged as highly degraded/unacceptable, as shown in (21c). This change in acceptability is predicted by the short source approach but not by Barros and Frank’s discourse-centering analysis.

|

Some student claimed that there was a problem with some professor, but I can’t recall which student

i

with which professor

j

|

| (Barros and Frank 2022: 9) |

| …which student had a problem with which professor. |

|

*?Some student claimed that there was a pile of books in some professor’s office, but I can’t recall which student

i

in which professor’s office

j

|

Barros and Frank also employ the opposite argument against the short source approach to clausemate condition violations: they argue that there are MS configurations in which a short source is available, yet the clausemate condition still applies due to the embedded subject being “non-shifty.” Their evidence comes from (22a), which is unacceptable despite a short source being available, as shown in (22b). I contend Barros and Frank’s assumption that the unacceptability of (22a) arises from a violation of the clausemate condition. I claim instead that (22a) is unacceptable because bound objects pronouns cannot be used as correlates in English caMS, which I tentatively postulate to be caused by the lack of overt case marking in the wh-phrases. Justification for this alternative explanation comes from the fact that the German equivalent in (23a) is perfectly acceptable, and indeed the long source alternative (23b) is much degraded, contra Grano and Lasnik’s (2018) and Barros and Frank’s (2022) predictions. Precisely why a cross-linguistic difference is obtained between English and German remains to be determined – what is important here is that (23a) does not provide evidence against the short source approach.[18]

| *Some student claimed that Mary introduced him to some professor, but I don’t know which student to which professor |

| … which student Mary introduced to which professor. |

| (Barros and Frank 2022: 7) |

| Ein | Student i | behauptete, | dass | Mary | ihn i | einem | Professor | vorgestellt | |

| a.nom | student | claimed | that | Mary | he.acc | a.dat | professor | introduced |

| hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | genau | welchen | Studenten | welchem | Professor |

| has | but | I | know | not | exactly | which.acc | student | which.dat | professor |

| ?*Ein | Student i | behauptete, | dass | Mary | ihn i | einem | Professor | vorgestellt | |

| a.nom | student | claimed | that | Mary | he.acc | a.dat | professor | introduced |

| hat, | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | genau | welcher | Student | welchem | Professor |

| has | but | I | know | not | exactly | which.nom | student | which.dat | professor |

To summarize, I have discussed a few of the arguments from the literature against a short source explanation for the clausemate condition obviations and demonstrated that each fails to withstand scrutiny and, therefore, that none of them seem to represent a genuine problem for the short source analysis.

4 Conclusion

The studies presented in this paper have shown that the two generalizations for multiple sluicing outlined by Abels and Dayal (2017, 2022) are supported by experimental data. Those generalizations have been investigated side-by-side in three parallel acceptability judgment studies in three different single wh-fronting languages, namely German, English, and Spanish, as well as in an additional follow-up self-paced reading experiment in German.

On the one hand, the first generalization, i.e., the correlates in a caMS configuration must originate within the same clause, was examined. Across the three acceptability judgment studies, the same significant effect was obtained, whereby correlates originating within the same tensed clause boundary were judged significantly more acceptable than those originating across clause boundaries. The second generalization states that correlates in a caMS structure can originate inside an island. In order to investigate this, I compared the acceptability of caMS sentences where the embedded clause in the antecedent was a non-island (that-clause) or a strong island (because-island). The prediction based on Abels and Dayal’s generalization assumes that there should not be a difference between both levels. Since this null difference cannot be directly tested using a hypothesis testing experimentation – the type of studies used here – I conducted parallel cross-linguistic studies to try to mitigate this shortcoming and provide evidence that this null difference is replicable. The results showed no significant differences in the acceptability of caMS based on the islandhood of the embedding clause in the antecedent. Additionally, to show that the null differences are not just caused by the offline nature of the study, I conducted a follow-up reading time study. The results of this online experiment showed that the reading times concerned with the resolution of the wh-remnants are analogous, regardless of whether correlates in the antecedent of caMS constructions originate in a that-clause, a because-island, or a subject-island. All in all, the results obtained across the four experiments provide experimental evidence for Abels and Dayal’s claims and show that they are generalizable since the three investigated languages displayed comparable results.

Those results have been interpreted as providing additional evidence for a short source identity approach in sluicing and, particularly, in caMS. I have argued that the material at the sluicing site feeding the meaning of the wh-remnants is a non-isomorphic short paraphrase of the actual antecedent (Abels and Dayal 2017, 2022; Lasnik 2014; Marušič and Žaucer 2013). The non-isomorphic paraphrase is a monoclausal short source (not containing the island or the that-clause). Therefore, the underlying syntactic structure assigning the meaning to the wh-remnants is indeed the same, namely a short source. In Section 3, I discussed the most recent arguments presented in Barros and Frank 2022 where the clausemate condition is suspended. Those authors argue that discourse factors such as a “shifty subject” in the embedded clause moving the attention away from the most salient referent in the main clause are responsible for triggering a clause-boundedness effect. They present examples where MS constructions not involving a bound pronoun are possible, which would go against a short source analysis. Nevertheless, I have provided arguments and counterexamples that challenge their “shifty subject” analysis. It is, however, still necessary to investigate the arguments presented in Barros and Frank more systematically and test their counterarguments.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 75650358 – SFB 833

References

Abe, Jun. 2015. The in-situ approach to sluicing. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/la.222Suche in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus. 2011. Don’t repair that island! It ain’t broke. Paper presented at the islands in contemporary linguistic theory conference. Vitoria/Gasteiz, University of the Basque Country.Suche in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus. 2018a. Movement and islands. In Jeroen van Craenenbroeck & Tanja Temmerman (eds.), The Oxford handbook of ellipsis, 389–424. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198712398.013.17Suche in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus. 2018b. On “sluicing” with apparent massive pied-piping. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37. 1205–1271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9432-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus & Veneeta Dayal. 2017. On the syntax of multiple sluicing. In Andrew Lamont & Katerina A. Tetzloff (eds.), North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 47, 1–20. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus & Veneeta Dayal. 2022. On the syntax of multiple sluicing and what it tells us about wh scope taking. Linguistic Inquiry 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00448.Suche in Google Scholar

Achimova, Asya, Viviane Deprez & Julien Musolino. 2010. What makes pair list answers available: An experimental approach. In Yelena Fainleib, Nicholas LaCara & Yangsook Park (eds.), North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 41. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Bai, Xue & Daiko Takahashi. submitted. Pair-list interpretation in multiple sluicing in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistic Inquiry 1–17.10.1162/ling_a_00527Suche in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew. 2014. Sluicing and identity in ellipsis. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew & Luis Vicente. 2016. A remnant condition for ellipsis. In Kyeong-min Kim (ed.), Proceedings of West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 33, 57–66. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew & Robert Frank. 2017. A constraint on long-distance multiple sluicing. Poster presented at GLOW, 40.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew & Robert Frank. 2016. Discourse domains and syntactic phases: A constraint on long-distance multiple sluicing. Handout for NYU Syntax Brown Bag.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew & Robert Frank. 2022. Attention and locality: On clause-boundedness and its exceptions in multiple sluicing. Linguistic Inquiry. Advance publication. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00458.Suche in Google Scholar

Barros, Matthew, Patrick Elliott & Thoms Gary. 2014. There is no island repair. Ms. Rutgers, UCL, University of Edinburgh.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Benjamin M. Bolker & Steven C. Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Suche in Google Scholar

Chiu, Liching Livy. 2007. A focus-movement account on Chinese multiple sluicing. Nanzan Linguistics 1(1). 23–31.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Christensen, Rune Haubo B. 2019. ordinal – Regression models for ordinal data. R package version 2019. 12–10. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal.Suche in Google Scholar

Chung, Sandra, William A. Ladusaw & James Mccloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language Semantics 3. 239–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01248819.Suche in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara & Martina Gračanin-Yuksek. 2020. Conjunction saves multiple sluicing: How *(and) why? Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(1). 1–29. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1112.Suche in Google Scholar

Cortés Rodríguez, Álvaro. 2021. Multiple adjacent wh-interrogatives in Spanish. Presentation at II. Encuentro de Lingüística Formal en México. México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Puebla (Online).Suche in Google Scholar

Cortés Rodríguez, Álvaro. in prep. An experimental lens on multiple sluicing: Amelioration effects, cross-linguistic variation and processing. Tübingen: Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Cortés Rodríguez, Álvaro. under review. Which syntactician which kind of ellipsis: An experimental investigation of multiple sluicing. In Andreas, Konietzko & Susanne, Winkler (eds.), Information Structure and Discourse in Generative Grammar. Mechanisms and Processes, vol. SGG 146. Boston & Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Cortés Rodríguez, Álvaro & James Griffiths. 2022. Experimental evidence from German for a short source approach to apparent clausemate condition obviations in multiple sluicing. Presentation at GLOW 45.Suche in Google Scholar

Culicover, Peter W. & Ray Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199271092.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Dayal, Veneeta. 2016. Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199281268.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Dayal, Veneeta & Roger Schwarzschild. 2010. Definite inner antecedents and Wh-correlates in sluices. In Peter Staverov, Daniel Altshuler, Aaron Braver, Carlos A. Fasola & Sarah Murray (eds.), Rutgers working papers in linguistics, vol. 3, 92–114. New Brunswick, NJ: LGSA.Suche in Google Scholar

Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 1973. On the nature island constraints. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Featherston, Sam. 2009. A scale for measuring well-formedness: Why linguistics needs boiling and freezing points. In Sam Featherston & Susanne Winkler (eds.), The fruits of empirical linguistics, vol. 1, 47–74. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110216141.47Suche in Google Scholar

Fox, Danny & Howard Lasnik. 2003. Successive-cyclic movement and island repair: the difference between sluicing and VP-ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 34. 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438903763255959.Suche in Google Scholar

Gallego, Ángel J. 2017. Multiple Wh-movement in European Spanish exploring the role of interface conditions for variation. In Olga Fernández-Soriano, Elena Castroviejo & Isabel Pérez-Jimenez (eds.), Boundaries, phases and interfaces. Case studies in honor of Violeta Demonte, 195–221. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/la.239.10galSuche in Google Scholar

Gerbrich, Hannah, Vivian Schreier & Sam Featherston. 2019. Standard items for English judgment studies: Syntax and semantics. In Sam Featherston, Robin Hörnig, Sophie von Wietersheim & Susanne Winkler (eds.), Experiments in focus: Information structure and semantic processing, 305–328. Berlin: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110623093-012Suche in Google Scholar

Ginzburg, Jonathan & Ivan A. Sag. 2000. Interrogative investigations: The form, meaning, and use of English interrogatives. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Grano, Thomas & Howard Lasnik. 2018. How to neutralize a finite clause boundary: Phase theory and the grammar of bound pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 49(3). 465–499. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00279.Suche in Google Scholar

Grewendorf, Günther & Cecilia Poletto. 1991. Die Cleft-Konstruktion im Deutschen, Englischen und Italienischen. In Gisbert Fanselow & Sascha W. Felix (eds.), Strukturen und Merkmale syntaktischer Kategorien, 174–216. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Griffiths, James & Anikó Lipták. 2014. Contrast and island sensitivity in clausal ellipsis. Syntax 17(3). 189–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12018.Suche in Google Scholar

Grosz, Barbara J., Aravind K. Joshi & Scott Weinstein. 1995. Centering: A framework for modeling the local coherence of discourse. Computational Linguistics 21(2). 203–206.10.21236/ADA324949Suche in Google Scholar

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier. 1996. The scope of universal quantifiers in Spanish interrogatives. In Karen Zagona (ed.), Grammatical theory and romance languages, 87–98. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/cilt.133.08gutSuche in Google Scholar

Hoyt, Frederick & Alexandra Teodorescu. 2012. How many kinds of sluicing, and why? Single and multiple sluicing in Romanian, English, and Japanese. In Jason Merchant & Andrew Simpson (eds.), Sluicing: Cross-linguistic perspectives, 83–103. Oxford: Oxford University Pressoup.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199645763.003.0005Suche in Google Scholar

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT.Suche in Google Scholar

Just, Marcel Adam, Patricia A. Carpenter & Jacqueline D. Woolley. 1982. Paradigms and processes in reading comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 111(2). 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.111.2.228.Suche in Google Scholar

Kotek, Hadas & Matthew Barros. 2018. Multiple sluicing, scope, and superiority: Consequences for ellipsis identity. Linguistic Inquiry 49(4). 781–812. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00289.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff & Rune Haubo B. Christensen. 2017. lmerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82(13). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.Suche in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. When can you save a structure by destroying it. In Minjoo Kim & Uri Strauss (eds.), North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 31, vol. 2, 301–320. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard. 2005. Review: The syntax of silence by Jason merchant. Language 81(1). 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0025.Suche in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard. 2014. Multiple sluicing in English? Syntax 17(1). 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12009.Suche in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard & Mamoru Saito. 1992. Move alpha: Conditions on its application and output. Nature. Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Martín González, Javier. 2010. Voice mismatches in English and Spanish sluicing. Iberia 2(2). 23–44.Suche in Google Scholar

Marušič, Franc & Rok Žaucer. 2013. A note on sluicing and island repair. In Steven Franks (ed.), Annual workshop on formal approaches to Slavic linguistics: The Third Indiana Meeting 2012, vol. 59, 176–189. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199243730.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2004. Fragments and ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27. 661–738.10.1007/s10988-005-7378-3Suche in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2006. Sluicing. In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), The syntax companion, vol. 1, 269–289. London: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470996591.ch60Suche in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2008. Variable island repair under ellipsis. In Kyle Johnson (ed.), Topics in ellipsis, 132–153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511487033.006Suche in Google Scholar

Nishigauchi, Taisuke. 1998. “Multiple sluicing” in Japanese and the functional nature of the wh-phrase. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 7(2). 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008246611550.10.1023/A:1008246611550Suche in Google Scholar

Pafel, Jürgen. 2005. Quantifier scope in German. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/la.84Suche in Google Scholar

Partee, Barbara. 1995. Quantificational structures and compositionality. In Emmon Bach, Eloise Jelinek, Angelika Kratzer & Barbara Partee (eds.), Quantification in natural languages, 541–602. Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-017-2817-1_17Suche in Google Scholar

Peirce, Jonathan, Jeremy R. Gray, Sol Simpson, Michael MacAskill, Richard Höchenberger, Hiroyuki Sogo, Erik Kastman & Jonas Kristoffer Lindeløv. 2019. PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods 51(1). 195–203. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Psychology Software Tools. 2016. Pittsburgh, PA: Inc [E-Prime 3.0]. Available at: https://support.pstnet.com/.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.r-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Richards, Norvin. 2010. Uttering trees. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262013765.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Rodrigues, Cilene, Andrew Ira Nevins & Luis Vicente. 2009. Cleaving the interactions between sluicing and P-stranding. In Danièle Torck & W. Leo Wetzels (eds.), Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2006. Selected papers from “Going Romance”, Amsterdam, 7–9 December 2006, 175–198. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/cilt.303.11rodSuche in Google Scholar

Ross, John Robert. 1969. Guess who? In Robert I. Blinnick, Alice Davison, Georgia M. Green & Jerry L. Morgan (eds.), Papers from the fifth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 252–286. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chicago Linguistic Society.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199645763.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Rottman, Isaac & Masaya Yoshida. 2013. Sluicing, idioms, and island repair. Linguistic Inquiry 44(4). 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00142.Suche in Google Scholar

Rudin, Deniz. 2019. Head-based syntactic identity in sluicing. Linguistic Inquiry 50(2). 253–283. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00308.Suche in Google Scholar

Sag, Ivan A. & Joanna Nykiel. 2011. Remarks on sluicing. In Stefan Müller (ed.), 18th International conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar, 188–208. Standford, CA: CLSI Publications.10.21248/hpsg.2011.11Suche in Google Scholar

Stainton, Robert J. 2006. Words and thoughts: Subsentences, ellipsis, and the philosophy of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199250387.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Stjepanović, Sandra. 1999. Multiple sluicing and superiority in Serbo-Croatian. In Pius Tamanji, Masako Hirotani & Nancy Hall (eds.), North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 29, Vol. 2, 145–160.Suche in Google Scholar

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2007. Strong vs. weak islands. The Blackwell Companion to Syntax 4. 479–531.10.1002/9780470996591.ch64Suche in Google Scholar

Takahashi, Daiko. 1994. Sluicing in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3(3). 265–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01733066.Suche in Google Scholar

Takahashi, Daiko & Sichao Lin. 2012. Two notes on multiple sluicing in Chinese and Japanese. Nazan Linguistics 8. 129–145.Suche in Google Scholar

Thoms, Gary. 2013. Lexical mismatches in ellipsis and the identity condition. In Stefan Keine & Shayne Slogett (eds.), North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 42. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Vicente, Luis. 2015. Morphological case mismatches under sluicing. Snippets 29. 16–17. https://doi.org/10.7358/snip-2015-029-vice.Suche in Google Scholar

Vicente, Luis. 2018. Sluicing and its subtypes. In Jeroen van Craenenbroeck & Tanja Temmerman (eds.), The Oxford handbook of ellipsis, 478–503. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198712398.013.22Suche in Google Scholar

Winkler, Susanne. 2013. Syntactic diagnostics for extraction of focus from ellipsis site. In Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng & Norbert Corver (eds.), Diagnosing syntax, 463–484. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199602490.003.0023Suche in Google Scholar

Yoshida, Masaya, Jiyeon Lee & Michael Walsh Dickey. 2013. The island (in)sensitivity of sluicing and sprouting. In Jon Sprouse & Norbert Hornstein (eds.), Experimental syntax and island effects, 360–376. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139035309.018Suche in Google Scholar

Yoshida, Masaya, Tim Hunter & Michael Frazier. 2015. Parasitic gaps licensed by elided syntactic structure. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33(4). 1439–1471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9275-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Yoshida, Masaya, David Potter & Tim Hunter. 2019. Condition C reconstruction, clausal ellipsis and island repair. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37(4). 1515–1544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9433-0.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: Special issue on empirical approaches to elliptical constructions

- Articles

- Explaining ellipsis without identity*

- Experimentally testing the interpretation of multiple sluicing and multiple questions in Hungarian

- Multiple sluicing and islands: a cross-linguistic experimental investigation of the clausemate condition

- Pseudogapping in English: a direct interpretation approach

- Me too fragments in English and French: a direct interpretation approach

- Complementizer deletion in embedded gapping in Spanish

- An experimental perspective on embedded gapping in Persian

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: Special issue on empirical approaches to elliptical constructions

- Articles

- Explaining ellipsis without identity*

- Experimentally testing the interpretation of multiple sluicing and multiple questions in Hungarian

- Multiple sluicing and islands: a cross-linguistic experimental investigation of the clausemate condition

- Pseudogapping in English: a direct interpretation approach

- Me too fragments in English and French: a direct interpretation approach

- Complementizer deletion in embedded gapping in Spanish

- An experimental perspective on embedded gapping in Persian