Abstract

Objectives

This study emphasizes the importance of determining the serum levels of pentraxin-3 (PTX3), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), and tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TNFAIP6) in patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF).

Methods

This prospective study involved 30 confirmed CCHF patients and 30 healthy controls. Serum concentrations of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 were quantified utilizing a quantitative sandwich ELISA method.

Results

CCHF patients exhibited markedly elevated PTX3 levels, reflecting an acute inflammatory response. As a long pentraxin, PTX3 functions as a pattern recognition receptor that activates the complement system to aid in pathogen clearance. Additionally, FGF2 levels were significantly increased, indicating a potential role in repairing endothelial damage. Known for promoting angiogenesis and immune regulation, FGF2 may counteract endothelial dysfunction induced by CCHF. Conversely, TNFAIP6 levels were lower in patients, possibly due to shifts in cytokine activity that suppress its anti-inflammatory and extracellular matrix-regulating effects, potentially leading to greater tissue injury.

Conclusions

The dysregulation of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 in CCHF patients signifies a disrupted equilibrium in inflammatory and vascular response mechanisms. This triad of biomarkers could serve as a valuable tool for assessing the severity of CCHF and may present therapeutic targets for modulating inflammation and mitigating endothelial damage. Achieving a balance among PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 could be instrumental in alleviating disease complications, thereby suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for managing CCHF effectively.

Introduction

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a significant viral zoonosis caused by the CCHF virus, a member of the Orthonairovirus genus in the Nairoviridae family of the Bunyavirales order. This disease is primarily transmitted to humans through bites from infected ticks, particularly the Hyalomma species, or through contact with the blood and tissues of infected animals, making it a notable public health concern in endemic regions across Europe, Asia, and Africa [1], [2], [3], [4]. The clinical presentation of CCHF can range from mild febrile illness to severe hemorrhagic manifestations, with case fatality rates reported between 9 and 50 %, depending on the outbreak and geographical context [1], 5], 6]. Despite the existence of a vaccine, its limited efficacy and the challenges associated with tick control have hindered effective prevention strategies [1], 7]. Moreover, treatment options remain controversial, with ribavirin being the most used antiviral, although its effectiveness is still debated [8]. The epidemiological landscape of CCHF is dynamic, with recent studies indicating an increase in cases and the emergence of new strains, necessitating enhanced surveillance and preparedness measures [5], 9], 10].

Coagulation abnormalities, uncontrolled bleeding, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction are central to the disease’s pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. Despite these findings, there remains a critical need to further elucidate the pathogenesis of CCHF. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the infection is essential, particularly in identifying biomarkers that can reliably track disease progression and predict clinical outcomes. Such biomarkers will not only be useful in early diagnosis but also facilitate the development of targeted therapies aimed at modulating inflammation and preserving endothelial function. Consequently, continued research is necessary to address these gaps and develop a more comprehensive approach to managing CCHF infection.

Pentraxin-3 (PTX3) is a long pentraxin that plays a multifaceted role in the regulation of inflammation and immune responses [11], 12]. PTX3 has been shown to modulate the activity of the complement system, enhancing its opsonic capacity while also serving as a negative regulator to limit excessive inflammation [13], 14]. This dual functionality underscores its importance in maintaining homeostasis during inflammatory responses, particularly in conditions such as acute kidney injury and infections [15], 16]. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), another critical player in tissue repair and regeneration, interacts with PTX3 in various biological contexts. FGF2 is known for its roles in angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and differentiation, and it has been implicated in protective mechanisms against ischemia-reperfusion injury [17], 18]. The interplay between PTX3 and FGF2 particularly contributes to the modulation of inflammatory pathways and tissue repair processes [17], 19]. Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TNFAIP6) has emerged as a significant mediator in the context of inflammation and tissue repair, often acting in concert with PTX3 and FGF2 [20]. TNFAIP6 is known to modulate the extracellular matrix and inhibit pro-inflammatory signaling, thus playing a protective role in various inflammatory conditions [20]. The collaborative actions of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 highlight a complex network of interactions that govern inflammatory responses and tissue regeneration, suggesting potential avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by dysregulated inflammation [21].

This study hypothesizes that the interaction between PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of CCHF. These are key factors in vascular integrity and immune responses, both of which are disrupted in CCHF. The importance of this study lies in its focus on a novel regulatory mechanism involving PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 in the context of CCHF, a relationship that has not been previously investigated. Understanding how these molecules interact could provide new insights into the vascular dysregulation and immune response seen in CCHF, opening potential therapeutic avenues to modulate angiogenesis and disease outcomes.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This prospective study was conducted in the Department of Clinical Microbiology, School of Medicine, Sivas Cumhuriyet University. A total of 60 subjects, including 30 CCHF patients and 30 healthy controls, were enrolled in the study. The initial diagnosis of the disease relied on a combination of clinical observations and laboratory test results. The definitive confirmation of CCHF was conducted at the National Reference Virology Laboratory in Ankara, Türkiye. This confirmation was established by identifying CCHF virus RNA in the bloodstream by applying reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). For the healthy control group, the exclusion criteria included a clinical suspicion of any neurological disorders, infections, or the presence of liver disease, kidney disease, rheumatic disease, malignancy, pregnancy, or smoking. The procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sivas Cumhuriyet University in accordance with the ethical standards established by the institution where the experiments were performed or in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (no: 2024-11/10). All participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Samples and biochemical analyses

Fasting blood samples were collected, and sera fractions were separated by centrifugation (3,500 rpm, 15 min, and 4 °C). They were then aliquoted and rapidly stored at −80 °C (WiseCryo, South Korea). Then quantitative sandwich ELISA technique was used for the determination of serum PTX3, FGF2 (Elabscience Biotechnology, China), and TNFAIP6 (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, China). The detection ranges of the ELISA kits were 0.3–20 ng/L for PTX3, 15.6–1,000 ng/L for FGF2, and 47–3,000 ng/L for TNFAIP6, and the intra-assay precision was<10 %. ELISA tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Patient samples were taken on the first day after admission. Patients records were obtained from Sivas Cumhuriyet University Hospital laboratory information system to determine age, gender, and the values of creatinine, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase (CK), total protein, albumin, amylase, lipase, ferritin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), fibrinogen, D-dimer and complete blood count (CBC) parameters. Biochemical analyses were performed using the Cobas 8,000 system (c702 and e801 modules, Roche Diagnostics, Germany), coagulation assessments were conducted with the CS-5100 analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Japan), and hemogram evaluations were carried out using the BC-6200 instrument (Mindray, China).

Statistical analysis

Histogram and Q-Q plots were examined, Shapiro-Wilk’s test was applied to test the data normality. In descriptive statistics, mean ± standard deviation, median (1st-3rd quartiles) were used for numerical data, and n (%) was used for categorical data. The Levene test was used to assess variance homogeneity. To compare the differences between groups, either a two-sided independent samples t–test or Mann–Whitney U tests were applied for continuous variables. ROC analyses were applied to identify the predictive ability of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 markers on groups. The area under ROC curves were calculated with 95 % confidence intervals and compared each other using DeLong’s test. For each marker, cut-off values are determined using the Youden index. Using these cut-off values, for each marker, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values are calculated with 95 % confidence intervals. Analyses were conducted using R 4.3.1 (www.r-project.org) software and GraphPad Prism version 8.3.0 (GraphPad software, USA, www.graphpad.com). A p-Value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

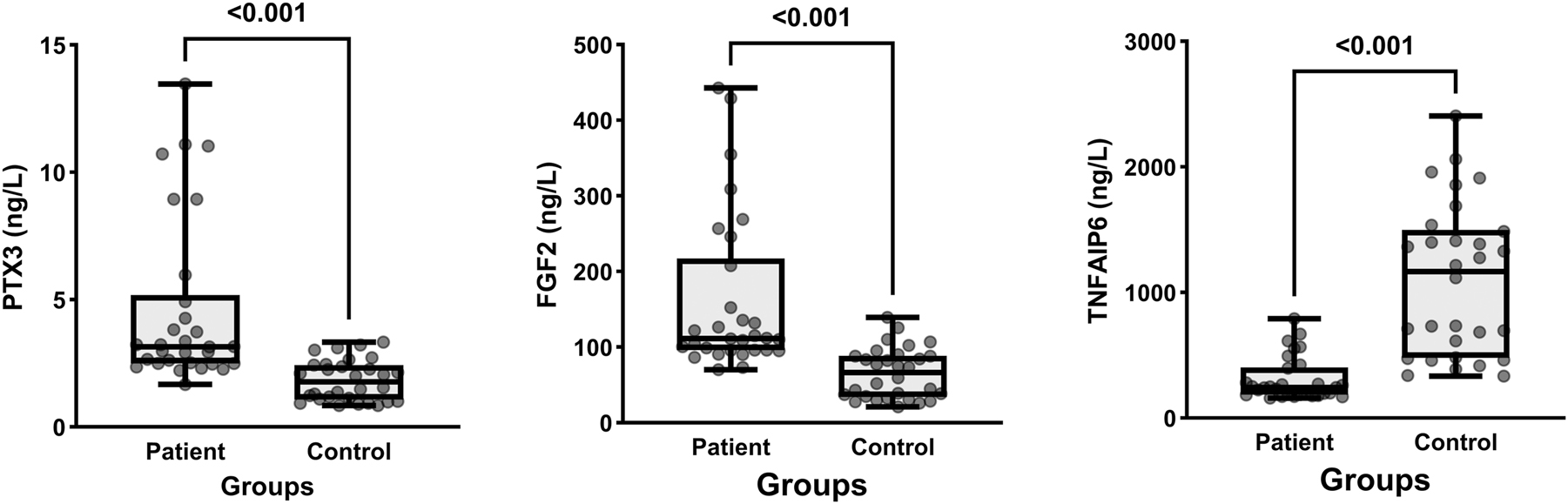

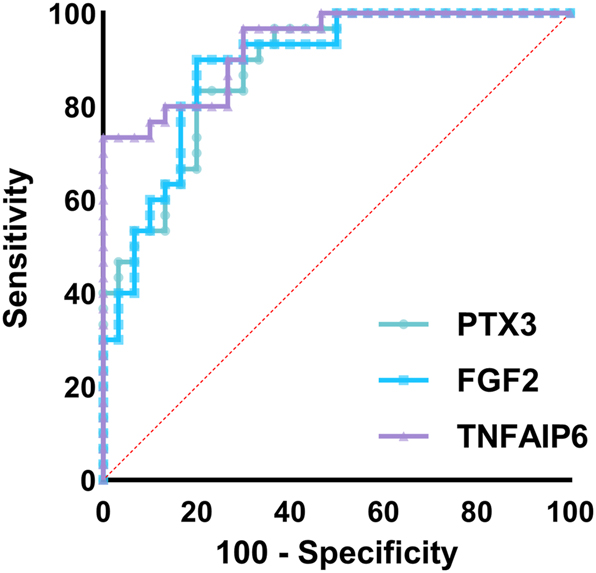

The study included 60 participants, divided equally between control (n=30) and patient (n=30) groups. The average age of participants was 51 ± 15 years. The gender distribution consisted of 56.7 % male (n=34) and 43.3 % female (n=26) participants. Among the CCHF patients, 83.3 % (n=25) survived, while 16.7 % (n=5) did not. CCHF patients were significantly older than controls (55 ± 17 vs. 47 ± 10 years, p=0.025). Biomarker analysis revealed markedly elevated PTX3 (3.10 vs. 1.80 ng/L, p<0.001) and FGF2 (112 vs. 66.5 ng/L, p<0.001) levels in patients compared to controls. In contrast, TNFAIP6 levels were significantly lower in patients (243 vs. 1,166 ng/L, p<0.001) (Table 1 and Figure 1). In CCHF patients, those who did not survive showed significant alterations in several biomarkers. Although PTX3 (2.95 vs. 3.7 ng/L, p=0.191), FGF2 (109 vs. 135 ng/L, p=0.113) and TNFAIP6 (225 vs. 251 ng/L p=0.232) levels were higher in non-survivors, this difference was not statistically significant. Key findings included substantially lower total protein and fibrinogen levels in non-survivors and significant elevations in leucocytes, neutrophils, AST, ALT, LDH, and ferritin. Additionally, non-survivors displayed profound coagulation abnormalities, with marked increases in APTT, PT, INR, and D-dimer levels compared to survivors (Table 2). The ROC curve analysis for PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 levels indicated a high diagnostic accuracy in predicting CCHF patients, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 88.1–93.0 %. FGF2 exhibited the highest sensitivity (90.0 %) and negative predictive value (88.9 %) at a cut-off >90.1 ng/L, whereas TNFAIP6 demonstrated the greatest specificity (100 %) and positive predictive value (100 %) at a cut-off <282 ng/L. No statistically significant difference was observed when the AUC values for these three tests were compared (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Comparisons of the variables between CCHF patients and healthy control groups.

| Variables | Groups | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=30) | Patient (n=30) | ||

| Age, years | 47 ± 10 | 55 ± 17 | 0.025 |

| PTX3, ng/L | 1.8 (1.1–2.4) | 3.1 (2.5–5.2) | <0.001 |

| FGF2, ng/L | 66.5 (34.1–88.6) | 112 (96.0–217) | <0.001 |

| TNFAIP6, ng/L | 1,166 (479–1,500) | 243 (185–403) | <0.001 |

-

CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; PTX3, pentraxin-3; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; TNFAIP6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

A box plot comparing the concentrations of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 between CCHF patients and healthy controls. CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; PTX3, pentraxin-3; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; TNFAIP6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6.

Comparison of deceased and surviving CCHF patients in terms of laboratory variables.

| Variables | Patient’s outcome | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survive (n=25) | Non-survive (n=5) | ||

| Age, years | 54 ± 18 | 62 ± 17 | 0.345 |

| PTX3, ng/L | 2.95 (2.49–5.27) | 3.73 (3.15–6.42) | 0.191 |

| FGF2, ng/L | 109 (95.4–220) | 135 (119–244) | 0.113 |

| TNFAIP6, ng/L | 225 (182–405) | 251 (240–411) | 0.232 |

| Ferritin, µg/L | 855 (338–3,958) | 10,769 (9,552–1,03,969) | 0.003 |

| IL-6, ng/L | 20.8 (11.4–63.1) | 138 (63–1,137) | 0.006 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 1.7 (0.8–3.7) | 0.231 |

| ALT, U/L | 25 (17–79) | 209 (63–803) | 0.008 |

| AST, U/L | 37 (27–131) | 642 (165–3,559) | 0.003 |

| ALP, U/L | 69 (57–99) | 284 (107–615) | 0.004 |

| GGT, U/L | 24 (16–37) | 171 (95–667) | 0.002 |

| LDH, U/L | 377 (246–540) | 693 (553–2,488) | 0.007 |

| CK, U/L | 233 (158–650) | 449 (200–2,462) | 0.330 |

| Total protein, g/L | 65.9 ± 5.96 | 57.0 ± 3.25 | 0.003 |

| Albumin, g/L | 41.3 (37.4–44.6) | 31.7 (30.7–36.4) | 0.004 |

| Amylase, U/L | 73 (52–85) | 114 (62–219) | 0.113 |

| Lipase, U/L | 45 (27–70) | 86 (43–628) | 0.155 |

| APTT, s | 29.7 (26.3–33.3) | 75.8 (38.9–160) | 0.003 |

| PT, s | 9.5 (9.0–11.6) | 16.1 (11.2–20.7) | 0.008 |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 2.0 (1.4–2.5) | 0.002 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 289 ± 66.3 | 172 ± 104 | 0.003 |

| D-dimer, mg/L FEU | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 21.2 (15.8–38.2) | 0.002 |

| Leucocytes, 109/L | 2.8 (2.0–4.6) | 6.8 (4.1–12.3) | 0.015 |

| Neutrophils, 109/L | 2.1 (1.3–3.5) | 4.3 (2.7–10.4) | 0.032 |

| Lymphocytes, 109/L | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.8 (0.6–2.4) | 0.062 |

| Monocytes, 109/L | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.1 (0.1–0.5) | 0.435 |

| IG, 109/L | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.4 (0.3–1.8) | 0.001 |

| IG, % | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 8.3 (6.8–14.7) | 0.001 |

| Thrombocytes, 109/L | 92 (76–119) | 28 (15–73) | 0.011 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.5 ± 1.9 | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 0.143 |

-

CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; PTX3, pentraxin-3; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; TNFAIP6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6; IL-6, interleukin-6; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK, creatin kinase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalization ratio; IG, immature granulocytes. Statistically significant p-Values are shown in bold.

The results of ROC curve analysis and statistical diagnostic measures for predicting CCHF disease.

| Variables | ROC statistics | Statistical diagnostic measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | AUC (95 %CI) | Sen (95 %CI) | Spe (95 %CI) | PPV (95 %CI) | NPV (95 %CI) | |

| PTX3, ng/L | >2.46 | 88.1 (77.2–95.0) | 83.3 (65.3–94.4) | 80.0 (61.4–92.3) | 80.6 (66.7–89.7) | 82.8 (67.9–91.6) |

| FGF2, ng/L | >90.1 | 88.6 (77.7–95.3) | 90.0 (73.5–97.9) | 80.0 (61.4.-92.3) | 81.8 (68.5–90.3) | 88.9 (72.9–96.0) |

| TNFAIP6, ng/L | <282 | 93.0 (83.4–98.0) | 73.3 (54.1–87.7) | 100 (88.4–100) | 100 | 78.9 (67.4–87.2) |

-

AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; CI, confidence interval; CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; PTX3, pentraxin-3; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; TNFAIP6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6.

Diagnostic accuracy of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 in CCHF prediction: ROC curve analysis. CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; PTX3, pentraxin-3; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; TNFAIP6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6.

Discussion

In this study, we observed higher PTX3 and FGF2 and lower TNFAIP6 levels in patients than healthy controls. PTX3 is a crucial component of the innate immune response, functioning as a soluble pattern recognition receptor that plays a significant role in various infectious diseases. As a member of the long pentraxin family, PTX3 is synthesized in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, including cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α [22], 23]. This synthesis occurs in multiple cell types, including neutrophils, monocytes, endothelial cells (ECs), and macrophages, particularly at sites of inflammation or infection [24], 25]. PTX3 is known for its ability to bind to pathogens and activate the complement system, thereby enhancing pathogen recognition and clearance [26], 27]. For instance, it has been shown to facilitate the recognition of bacteria and viruses by macrophages and dendritic cells, promoting phagocytosis [26], 27]. Accordingly, we think that the elevation of PTX3 levels in patients with CCHF can be attributed to several interrelated mechanisms associated with the disease’s pathophysiology. One of the primary reasons for increased PTX3 levels during CCHF is its role as an acute-phase protein in response to inflammation [28]. Moreover, PTX3 has been shown to interact with the complement system, enhancing opsonization and clearance of pathogens while also modulating inflammation [14]. This dual role of PTX3, acting both as a pro-inflammatory mediator and as a regulator of inflammation, suggests that its elevated levels in the complement activation mediated by PTX3 can lead to increased recruitment of neutrophils and other immune cells to the site of infection, which is crucial in combating the viral pathogen [29].

In the present study, we determined higher levels of FGF2 in patients compared to the healthy controls. A potential reason for increased FGF2 levels is the activation of ECs by the CCHF virus. The virus has been shown to induce significant changes in EC function, leading to increased vascular permeability and inflammation [30]. This endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of viral hemorrhagic fevers, where the integrity of the vascular barrier is compromised, resulting in hemorrhagic manifestations [31]. FGF2, a potent angiogenic factor, is upregulated in response to endothelial injury and inflammation, suggesting that its elevated levels may be a compensatory mechanism aimed at restoring vascular integrity and promoting tissue repair [31]. FGF2 is primarily known for its involvement in angiogenesis, wound healing, and tissue repair, but its implications in infectious disease mechanisms are increasingly recognized. FGF2 has been shown to modulate the immune response during viral infections. For instance, in the context of the influenza A virus (IAV), FGF2 is crucial for recruiting neutrophils to the site of infection, thereby mitigating acute lung injury associated with the virus. Studies demonstrate that FGF2 deficiency exacerbates the severity of IAV infections due to impaired neutrophil recruitment, while recombinant FGF2 administration significantly alleviates lung injury and enhances survival in infected models [32]. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that FGF2 can enhance the protective effects of PTX3 [33], 34]. Thus, we think that novel therapeutic strategies can be used targeting this synergistic relationship to modulate endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and immune response in CCHF patients.

TNFAIP6 plays a crucial role in modulating inflammatory responses and extracellular matrix dynamics. In the context of CCHF, lower levels of TNFAIP6 can be attributed to several molecular mechanisms that disrupt its expression and function. Firstly, TNFAIP6 is known to be regulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which can enhance its expression under normal circumstances. However, in the presence of viral infections like CCHF, the inflammatory milieu may shift, leading to altered cytokine profiles that could suppress TNFAIP6 expression. For instance, studies have shown that TNFAIP6 expression can be downregulated in conditions of chronic inflammation where high levels of IL-6 are present, indicating a complex interplay between cytokines that may inhibit TNFAIP6 production [35], 36]. Furthermore, the presence of inflammatory mediators can lead to the activation of signaling pathways that suppress TNFAIP6 transcription, such as the NF-κB pathway, which is often activated during viral infections [37].

The ROC curve analysis of PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 levels in our study demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in predicting CCHF patients. The highest sensitivity and negative predictive value were associated with FGF2, while the highest specificity and positive predictive value were observed for TNFAIP6. These results suggest that PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 are reliable biomarkers for identifying CCHF patients with high sensitivity and specificity. However, a similar difference was not observed between deceased and surviving patients. This suggests that these molecules play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease but are not associated with mortality.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated significant alterations in biomarker levels among CCHF patients compared to healthy controls, with markedly elevated PTX3 and FGF2 levels and significantly reduced TNFAIP6 levels in patients. These findings suggest that PTX3, FGF2, and TNFAIP6 may serve as valuable biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of CCHF, contributing to improved risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

-

Research ethics: The procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sivas Cumhuriyet University in accordance with the ethical standards established by the institution where the experiments were performed or in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (no: 2024-11/10).

-

Informed consent: All participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Mendoza, E, Warner, B, Safronetz, D, Ranadheera, C. Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever virus: past, present and future insights for animal modelling and medical countermeasures. Zoonoses Public Health 2018;65:465–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12469.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Kalal, MN. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: a global perspective. Int J Med Sci 2019;7:4812. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20195562.Search in Google Scholar

3. Messina, JP, Pigott, DM, Golding, N, Duda, KA, Brownstein, JS, Weiss, DJ, et al.. The global distribution of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:503–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trv050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Ekici-Günay, N, Koyuncu, S. An overview of procalcitonin in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: clinical diagnosis, follow-up, prognosis and survival rates. Turk J Biochem 2020;45:593–600. https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2020-0001.Search in Google Scholar

5. Ahmed, A, Ali, Y, Salim, B, Dietrich, I, Zinsstag, J. Epidemics of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) in Sudan between 2010 and 2020. Microorganisms 2022;10:928. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10050928.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Atkinson, B, Chamberlain, J, Logue, CH, Cook, N, Bruce, C, Dowall, SD, et al.. Development of a real-time RT-PCR assay for the detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2012;12:786–93. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0770.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Al-Abri, SS, Al, AI, Fazlalipour, M, Mostafavi, E, Leblebicioglu, H, Pshenichnaya, N, et al.. Current status of crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in the world health organization eastern mediterranean region: issues, challenges, and future directions. Int J Infect Dis 2017;58:82–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Kouhpayeh, H. A systematic review of treatment strategies including future novel therapies in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Int J Infect 2021;8. https://doi.org/10.5812/iji.113427.Search in Google Scholar

9. Maltezou, H, Andonova, L, Andraghetti, R, Bouloy, M, Ergonul, O, Jongejan, F, et al.. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Europe: current situation calls for preparedness. Euro Surveill 2010;15:19504. https://doi.org/10.2807/ese.15.10.19504-en.Search in Google Scholar

10. Knust, B, Medetov, ZB, Kyraubayev, KB, Bumburidi, Y, Erickson, BR, MacNeil, A, et al.. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Kazakhstan, 2009-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:643. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1804.111503.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Akyüz, M, Doğru, Y, Rudarli Nalcakan, G, Ulman, C, Taş, M, Varol, R. The effects of various strength training intensities on blood cardiovascular risk markers in healthy men. Turk J Biochem 2021;46:693–701. https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2021-0023.Search in Google Scholar

12. Inforzato, A, Reading, PC, Barbati, E, Bottazzi, B, Garlanda, C, Mantovani, A. The “sweet” side of a long pentraxin: how glycosylation affects PTX3 functions in innate immunity and inflammation. Front Immunol 2013;3:407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00407.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Ciancarella, V, Lembo-Fazio, L, Paciello, I, Bruno, AK, Jaillon, S, Berardi, S, et al.. Role of a fluid-phase PRR in fighting an intracellular pathogen: PTX3 in Shigella infection. PLoS Pathog 2018;14:e1007469. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007469.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Divella, C, Stasi, A, Franzin, R, Rossini, M, Pontrelli, P, Sallustio, F, et al.. Pentraxin-3-mediated complement activation in a swine model of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:10920. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202992.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Lech, M, Römmele, C, Gröbmayr, R, Susanti, HE, Kulkarni, OP, Wang, S, et al.. Endogenous and exogenous pentraxin-3 limits postischemic acute and chronic kidney injury. Kidney Int 2013;83:647–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2012.463.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Perea, L, Coll, M, Sanjurjo, L, Blaya, D, Taghdouini, AE, Rodrigo-Torres, D, et al.. Pentraxin‐3 modulates lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammatory response and attenuates liver injury. Hepatology 2017;66:953–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29215.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Tan, X, Tao, Q, Li, G, Xiang, L, Zheng, X, Zhang, T, et al.. Fibroblast growth factor 2 attenuates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.00147.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Tan, XH, Zheng, XM, Yu, LX, He, J, Zhu, HM, Ge, XP, et al.. Fibroblast growth factor 2 protects against renal ischaemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating mitochondrial damage and proinflammatory signalling. J Cell Mol Med 2017;21:2909–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13203.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Liebman, B, Schwaegler, C, Foote, AT, Rao, KS, Marquis, T, Aronshtam, A, et al.. Human growth factor/immunoglobulin complexes for treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022;10:749787. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.749787.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Leali, D, Inforzato, A, Ronca, R, Bianchi, R, Belleri, M, Coltrini, D, et al.. Long pentraxin 3/tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 interaction: a biological rheostat for fibroblast growth factor 2-mediated angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:696–703. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.111.243998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Maina, V, Cotena, A, Doni, A, Nebuloni, M, Pasqualini, F, Milner, CM, et al.. Coregulation in human leukocytes of the long pentraxin PTX3 and TSG-6. J Leukoc Biol 2009;86:123–32. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0608345.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Zhang, Y, Li, X, Zhang, X, Wang, T, Zhang, X. Progress in the study of pentraxin-3 (PTX-3) as a biomarker for sepsis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024;11:1398024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1398024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Caironi, P, Masson, S, Mauri, T, Bottazzi, B, Leone, R, Magnoli, M, et al.. Pentraxin 3 in patients with severe sepsis or shock: the ALBIOS trial. Eur J Clin Invest 2017;47:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12704.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Luo, Q, He, X, Ning, P, Zheng, Y, Yang, D, Xu, Y, et al.. Admission pentraxin‐3 level predicts severity of community‐acquired pneumonia independently of etiology. Proteonomics Clin Appl 2019;13:1800117. https://doi.org/10.1002/prca.201800117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Chen, H, Li, T, Yan, S, Liu, M, Liu, K, Zhang, H, et al.. Pentraxin-3 is a strong biomarker of sepsis severity identification and predictor of 90-day mortality in intensive care units via sepsis 3.0 definitions. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:1906. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11101906.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Du, H, Hu, H, Wang, P, Wang, X, Zhang, Y, Jiang, H, et al.. Predictive value of pentraxin-3 on disease severity and prognosis in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:445. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06145-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Astrup, E, Janardhanan, J, Otterdal, K, Ueland, T, Prakash, JA, Lekva, T, et al.. Cytokine network in scrub typhus: high levels of interleukin-8 are associated with disease severity and mortality. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis 2014;8:e2648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002648.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Guo, H, Qiu, X, Deis, J, Lin, TY, Chen, X. Pentraxin 3 deficiency exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2020;44:525–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0402-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Daigo, K, Yamaguchi, N, Kawamura, T, Matsubara, K, Jiang, S, Ohashi, R, et al.. The proteomic profile of circulating pentraxin 3 (PTX3) complex in sepsis demonstrates the interaction with azurocidin 1 and other components of neutrophil extracellular traps. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012;11:M111–015073. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.m111.015073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Connolly-Andersen, AM, Moll, G, Andersson, C, Åkerström, S, Karlberg, H, Douagi, I, et al.. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus activates endothelial cells. J Virol 2011;85:7766–74. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02469-10.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Ghazaei, C. The role of endothelial cell dysfunction in hemorrhagic fevers. Int J Basic Sci Med 2023;8:84–91. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijbsm.29634.Search in Google Scholar

32. Wang, K, Lai, C, Li, T, Wang, C, Wang, W, Ni, B, et al.. Basic fibroblast growth factor protects against influenza A virus-induced acute lung injury by recruiting neutrophils. J Mol Cell Biol 2018;10:573–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjx047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Koledová, Z, Sumbal, J, Rabata, A, de La Bourdonnaye, G, Chaloupková, R, Hrdličková, B, et al.. Fibroblast growth factor 2 protein stability provides decreased dependence on heparin for induction of FGFR signaling and alters ERK signaling dynamics. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019;7:331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2019.00331.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Nunes, QM, Li, Y, Sun, C, Kinnunen, TK, Fernig, DG. Fibroblast growth factors as tissue repair and regeneration therapeutics. PeerJ 2016;4:e1535. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. He, X, Chen, S, Wang, X, Kong, M, Shi, F, Qi, X, et al.. TSG6 plays a role in improving orbital inflammatory infiltration and extracellular matrix accumulation in TAO model mice. J Inflamm Res 2023;16:1937–48. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.s409286.Search in Google Scholar

36. Tan, KT, Baildam, AD, Juma, A, Milner, CM, Day, AJ, Bayat, A. Hyaluronan, TSG-6, and inter-α-inhibitor in periprosthetic breast capsules: reduced levels of free hyaluronan and TSG-6 expression in contracted capsules. Aesthetic Surg J 2011;31:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820x10391778.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Wang, H, Chen, Z, Li, XJ, Ma, L, Tang, YL. Anti-inflammatory cytokine TSG-6 inhibits hypertrophic scar formation in a rabbit ear model. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;751:42–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Unveiling the hidden clinical and economic impact of preanalytical errors

- Research Articles

- To explore the role of hsa_circ_0053004/hsa-miR-646/CBX2 in diabetic retinopathy based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification

- Study on the LINC00578/miR-495-3p/RNF8 axis regulating breast cancer progression

- Comparison of two different anti-mullerian hormone measurement methods and evaluation of anti-mullerian hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome

- The evaluation of the relationship between anti angiotensin type I antibodies in hypertensive patients undergoing kidney transplantation

- Evaluation of neopterin, oxidative stress, and immune system in silicosis

- Assessment of lipocalin-1, resistin, cathepsin-D, neurokinin A, agmatine, NGF, and BDNF serum levels in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Regulatory nexus in inflammation, tissue repair and immune modulation in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: PTX3, FGF2 and TNFAIP6

- Pasteur effect in leukocyte energy metabolism of patients with mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19

- Thiol-disulfide homeostasis and ischemia-modified albumin in patients with sepsis

- Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and oxidative imbalance: evaluation of ischemia-modified albumin and oxidant stress

- Antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of flavonoids isolated from fermented leaves of Camellia chrysantha (Hu) Tuyama

- Examination of the apelin signaling pathway in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Integrating network pharmacology, in silico molecular docking and experimental validation to explain the anticancer, apoptotic, and anti-metastatic effects of cosmosiin natural product against human lung carcinoma

- Validation of Protein A chromatography: orthogonal method with size exclusion chromatography validation for mAb titer analysis

- The evaluation of the efficiency of Atellica UAS800 in detecting pathogens (rod, cocci) causing urinary tract infection

- Case Report

- Exploring inherited vitamin B responsive disorders in the Moroccan population: cutting-edge diagnosis via GC-MS profiling

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor: “Gene mining, recombinant expression and enzymatic characterization of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Unveiling the hidden clinical and economic impact of preanalytical errors

- Research Articles

- To explore the role of hsa_circ_0053004/hsa-miR-646/CBX2 in diabetic retinopathy based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification

- Study on the LINC00578/miR-495-3p/RNF8 axis regulating breast cancer progression

- Comparison of two different anti-mullerian hormone measurement methods and evaluation of anti-mullerian hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome

- The evaluation of the relationship between anti angiotensin type I antibodies in hypertensive patients undergoing kidney transplantation

- Evaluation of neopterin, oxidative stress, and immune system in silicosis

- Assessment of lipocalin-1, resistin, cathepsin-D, neurokinin A, agmatine, NGF, and BDNF serum levels in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Regulatory nexus in inflammation, tissue repair and immune modulation in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: PTX3, FGF2 and TNFAIP6

- Pasteur effect in leukocyte energy metabolism of patients with mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19

- Thiol-disulfide homeostasis and ischemia-modified albumin in patients with sepsis

- Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and oxidative imbalance: evaluation of ischemia-modified albumin and oxidant stress

- Antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of flavonoids isolated from fermented leaves of Camellia chrysantha (Hu) Tuyama

- Examination of the apelin signaling pathway in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Integrating network pharmacology, in silico molecular docking and experimental validation to explain the anticancer, apoptotic, and anti-metastatic effects of cosmosiin natural product against human lung carcinoma

- Validation of Protein A chromatography: orthogonal method with size exclusion chromatography validation for mAb titer analysis

- The evaluation of the efficiency of Atellica UAS800 in detecting pathogens (rod, cocci) causing urinary tract infection

- Case Report

- Exploring inherited vitamin B responsive disorders in the Moroccan population: cutting-edge diagnosis via GC-MS profiling

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor: “Gene mining, recombinant expression and enzymatic characterization of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase”