Abstract

Objectives

The onset and advancement of silicosis are intricately linked to immune system activation and oxidative stress. We aimed to examine whether occupational silica exposure induces alterations in neopterin levels, the immune system, or the oxidant/antioxidant system.

Methods

Fifty-two healthy individuals, 47 workers with silica exposure who did not develop the disease, and 71 silicosis patients were included in the study, totaling 170 participants. Neopterin was measured in serum and urine. Chromatographic analysis of neopterin level was performed with Thermo Ultimate 3000 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OH-dG), glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) were measured in serum. Immune and oxidative stress parameters were measured by spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric methods.

Results

Serum neopterin levels were significantly different between the study groups, while urinary neopterin levels were not. Serum neopterin levels were significantly decreased in the silicosis group compared to the exposure and non-exposed group groups. TNF-α, IFN-γ, FGF, IL-1α, 8-OH-dG, and GR increased with silica exposure, while SOD and GPx decreased. Serum neopterin, IL-1α, GR, age, and forced expired volume (FEV1%) were found to be risk factors for silicosis development. A negative correlation existed between neopterin levels, TNF-α, and overall exposure duration.

Conclusions

Neopterin is applicable in the diagnosis and monitoring of oxidative stress and alterations in the immune system associated with silicosis. Thus, it can ensure that preventive measures are taken at an early stage.

Introduction

Neopterin is considered an early biomarker of the cellular immune response. This low-molecular-mass compound belongs to the pteridine class and is a guanosine triphosphate metabolite produced by activated macrophages and dendritic cells after stimulation with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) released from T-cells. Along with IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) also plays an important role in neopterin production [1]. It has been proposed that neopterin is not only an indication of oxidative stress arising from immunological activation but also contributes to oxidative stress by modifying the effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [2], 3]. An international group recognizes that serum neopterin levels can be used as an indicator of the impact of silica exposure and other occupational diseases [4].

Understanding the pathogenesis of silicosis is still incomplete, and there is limited data in humans [5]. In the early phase of inflammation in silica exposure, macrophages, mostly an M1 pro-inflammatory type, predominate. These macrophages secrete highly inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukins (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and ROS, which are necessary to eliminate silica particles. Since silica particles phagocytized by macrophages cannot be eliminated like infectious agents, they cause the continuation of inflammation and oxidative stress through persistent macrophage activation [6], [7], [8], [9]. Oxidative stress causes damage to the lungs, leading to an imbalance between oxidants (8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OH-dG)) and antioxidants (glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT)) in silicosis [10], [11], [12], [13]. In the late fibrosis stage of silicosis, M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages contribute to the resolution of inflammation, tissue repair, remodeling, immunosuppression, and fibrogenesis via anti-inflammatory cytokines [14], [15], [16]. Increased neopterin levels, closely associated with increased inflammation and oxidative stress, may lead to the onset of “immunodeficiency” with reduced T-cell response [17].

Clinical and functional changes in silicosis usually occur as the disease progresses. The identification of potential biomarkers for early detection of biological effects before these changes occur is crucial in terms of high-risk occupational exposures [18]. The objective of our study is to assess whether serum and urinary neopterin levels serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of silicosis. The study also aims to reveal the relationship between neopterin and the immune system (fibroblast growth factor (FGF), IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1α) and oxidative stress (SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, and 8-OH-dG).

Materials and methods

Study design and population

Individuals with silica exposure who presented to Ankara Occupational and Environmental Diseases Hospital for periodic health examinations were included in the study. The study population consisted of 170 participants, including 52 healthy individuals (non-exposed group), 47 people with silica exposure who did not develop disease (exposure), and 71 with silicosis.

All participants’ age, gender, pulmonary symptoms, smoking (mean pack-years), total working hours, use of protective equipment, physical examination findings, chest radiographs, high-resolution chest tomography (HRCT), pulmonary function tests (PFTs), and laboratory results were recorded on the evaluation form. Participants who were taking medication that affected neopterin levels, had a disease that affected neopterin levels such as chronic disease, autoimmune disease, infection, and malignancy, were younger than 18 years of age, and had worked in the same job for less than 1 year were not included in the study. The non-exposed group comprised office workers unexposed to silica, matched with the employee group by age and gender. All participants provided written informed consent.

Each individual underwent PFTs with the appropriate technique. The chest radiographs of all individuals included in the study, which were taken with a technique per International Labor Organization (ILO) standards, were evaluated by two pulmonologists with ILO radiography reading training certificates [19]. All those with silica exposure underwent HRCT. This research received approval from the Scientific Ethics Committee of Gülhane Military Medical Academy on June 16, 2016, with the number 50687469-1491-450-16/1648-1572.

Chemicals and kits

Blood and urine samples were collected in the morning and screened from direct light. Serum was acquired using centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The separated serum and urine samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. All chemicals were purchased from Algen Diagnostics Medical Ltd., Ankara, Türkiye. Neopterin, TNF-α, IFN-γ, FGF, IL-1α, IL-1β, GPx, CAT, and 8-OH-dG kits were obtained from Cloud-Clone Corp. (Wuhan, CHINA). SOD and GR kits were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Michigan, USA).

Neopterin operating procedure; 200 μL of ethanol was added to a 100 μL sample for protein precipitation and vortexed for 1 min. This material was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected in insert vials, and 20 μL of injection volume was injected into the chromatography device. Chromatographic analysis was performed with a Thermo Ultimate 3,000 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system. Chromatographic separation utilized a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, part no: 00b-4041-e0) with a mobile phase consisting of a water:acetonitrile mixture in a 99:1 ratio. The column oven temperature was optimized to 35 °C, and the flow rate was set to 1.5 mL/min. Measurements were performed at wavelengths of 353–438 nm in a fluorescence detector. The total analysis time was set at 5 min.

Immune and oxidative stress parameters; SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) was used for spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric measurements, and SoftMax Pro Software (Molecular Devices,CA, USA) for quantification. A ClarioStar microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) was used for ELISA analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using R Software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org). Numerical data that met the normality assumption were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), otherwise median (1st quartile – 3rd quartile). Categorical data were presented as frequency (n) and percentage (%). The Shapiro-Wilk’s normality test was used to control that the data met the normality assumption. In addition, to assess whether the assumption of homogeneity of the variances of the study groups was met, Levene’s test was performed. The differences in the numerical variables between the groups according to the fulfilment of the assumptions were analysed with the help of the Welch’s F test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. If significant differences were found as a result of these tests, Welch’s F test followed by Games-Howell test and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction were used for pairwise comparisons. Chi-square analysis was conducted to assess the association between study groups and categorical variables. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the differences between simple and complicated silicosis according to serum and urinary neopterin levels and immunological and oxidative stress parameters. Spearman’s rho analysis was utilized to assess the association among neopterin levels, TNF-α, and duration of exposure. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to predict the diagnostic ability of serum neopterin levels for distinguishing silicosis. The area under the curve (AUC) was computed with a 95 % confidence interval (CI). The statistical diagnostic metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV), were computed for the established ideal cut-off points. To determine the independent risk factors that were related to a higher risk of silicosis, multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted with the stepwise variable selection method. The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were presented with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Overall model fit test statistics and related p-value were obtained by Chi-square sample distribution, and Akaike information criteria (AIC), Bayesian information criteria (BIC) as fit measures of models, and also Nagelkerke’s R2 statistics as determination coefficients pseudo R2 was used to explain the model’s fit performance. In addition, area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, specificity and sensitivity values were used to examine the predictive performance measure of model at cut-off value of 0.5. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Sample size calculation

To detect a significant difference in serum neopterin levels between the study groups, we performed a prior sample size calculation using the “pwr” package in R version 4.2.1 (www.r-project.org), indicating that the minimum sample size of 46 in each arm would be required to detect a large effect size (Cohen’s f=0.4) with 99 % statistical power (1 − β) at the 5 % significance level (α).

Results

A total of 170 individuals with a mean age of 40.61 (±8.18, range: 18–72 years) were included in the study. Forty-seven were exposed to silica without silicosis (27.6 %), 53 (74.6 %) were diagnosed with simple silicosis, and 18 (25.4 %) were diagnosed with complicated silicosis. The demographic attributes of the study cohorts are outlined in Table 1. The percentages of forced expired volume (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were markedly reduced in the silicosis group relative to the non-exposed group (p=0.001). The average diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) in the silicosis cohort was considerably lower than that in the exposure cohort (p=0.042).

The demographical characteristics, and neopterin levels, immunological and oxidative stress parameters of the study groups.

| Variables | Silicosis (n=71) | Exposure (n=47) | Non-exposed (n=52) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.5±7.1a | 37.5±6.5b | 40.9±10.0 | <0.0011 |

| Cough | 24 (33.8) | 8 (17) | 0.0733 | |

| Sputum | 16 (22.5) | 8 (17) | 0.6213 | |

| Dyspnea | 38 (53.5) | 9 (19.1) | <0.0013 | |

| Chest pain | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0.5174 | |

| Smoking status | 0.0015 | |||

| Never | 11 (15.5)a | 8 (17)a | 23 (44.2)b | |

| Current smoker | 42 (59.2)a | 33 (70.2)a | 21 (40.4)b | |

| Ex-smoker | 18 (25.4) | 6 (12.8) | 8 (15.4) | |

| Cigarette pack years | 13.5 (8.75–20) | 12 (8–15.5) | 12 (10–16) | 0.7182 |

| Duration of exposure, years | 15.7±7.8 | 11.0±7.8 | – | 0.0026 |

| Using protective equipment | 63 (88.7) | 46 (97.9) | – | 0.0844 |

| Use of mask | 60 (84.5)a | 45 (95.7) | – | 0.1083 |

| Use of glove | 61 (85.9)a | 44 (93.6) | – | 0.3143 |

| Use of goggles | 55 (77.5)a | 37 (78.7)a | – | >0.9993 |

| Use of aspirator | 47 (66.2)a | 37 (78.7)a | – | 0.2073 |

| PFT result | ||||

| FVC, % | 89.2±17.4a | 93.9±10.1a | 101±12.3b | <0.0011 |

| FEV1, % | 88.4±19.2a | 94.9±11.7a | 102±11.11b | <0.0011 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 82 (78–85) | 84 (79–88) | 84 (80–86) | 0.0752 |

| DLCO, % | 93±17.4 | 101±17.4 | – | 0.0426 |

-

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, median with quartiles (1st quartile–3rd quartile), or count (n) and percentage (%), as appropriate. Different small superscript in each column indicates the statistically significant differences after multiple comparison. 1Welch’s F-test, followed by Games-Howell post-hoc test. 2Kruskal-Wallis H test, followed by Dunn post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction. 3Chi-square test with Yates continuity correction. 4Fisher-exact test. 5Pearson chi-square test, followed by two-proportion Z-test. 6Student’s t-test. FEV1, forced expired volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; PEF, peak expiratory flow; DLCO, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide.

The comparison of the serum and urinary neopterin levels and immunological and oxidative stress parameters of the study groups is shown in Table 2. Compared to those in the non-exposed group, the TNF-α, IFN-γ, and 8-OH-dG levels in the silicosis and exposure groups were significantly higher, and SOD level was lower. The FGF level in the exposure group was significantly higher than in the non-exposed group. GPx levels were lowest in the exposure group and significantly lower in the silicosis group compared to the non-exposed group. The IL-1α level was highest in the exposure group, followed by the silicosis group, with a statistically significant difference observed among all groups. Compared with the non-exposed group, GR levels were significantly higher in the silicosis and exposure groups.

The neopterin levels, immunological and oxidative stress parameters of the study groups.

| Variables | Silicosis (n=71) | Exposure (n=47) | Non-exposed (n=52) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 121 (112–253)a | 200 (114–220)a | 101 (90–108)b | <0.001 |

| FGF, pg/mL | 340 (26.4–408) | 394 (317–503)a | 268 (178–462)b | 0.004 |

| IFN-γ, pg/mL | 786 (656–831)a | 772 (636–866)a | 614 (521–688)b | <0.001 |

| SOD, U/mL | 0.04 (0.03–0.05)a | 0.04 (0.03–0.04)a | 2.02 (2.01–2.03)b | <0.001 |

| IL-1β, pg/mL | 272 (217–325) | 287 (237–317) | 260 (211–304) | 0.387 |

| IL-1α, pg/mL | 74.6 (68.8–76.7)a | 76.3 (75.6–77.1)b | 65.3 (59.1–67.6)c | <0.001 |

| GPx, nmol/min/mL | 4.51 (3.64–5.65)a | 3.71 (3.37–4.42)b | 6.2 (5.29–6.43)c | <0.001 |

| Catalase, U/mL | 0.96 (0.48–1.34) | 0.93 (0.58–1.36) | 1.29 (0.67–1.55) | 0.121 |

| 8-OH-dG, pg/mL | 2,615 (1780–3,435)a | 2,170 (1723–2,880)a | 1,505 (1,253–1806)b | <0.001 |

| GR, nmol/mL/min × 103 | 4.33 (3.08–10)a | 4.5 (3.25–10)a | 4 (2.29–5)b | 0.033 |

| Serum neopterin, ng/mL | 19.4 (16.5–26.5)a | 27.7 (19.5–35.4)b | 28.3 (19.3–37.1)b | 0.003 |

| Urinary neopterin, ng/mL | 1,387 (1,013–1852) | 1,359 (1,063–1,624) | 1,438 (1,234–1,699) | 0.678 |

-

Data were expressed as median with quartiles (1st quartile–3rd quartile). Different small superscript in each column indicates the statistically significant differences after multiple comparison. p-Values obtained by Kruskal-Wallis H test, followed by Dunn post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; SOD, superoxide dismutase; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-1α, interleukin-1α; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; 8-OH-dG, 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine; GR, glutathione reductase.

While the serum neopterin levels were significantly different among study groups (p=0.003, Figure 1A), the urinary neopterin levels were not different (p=0.678, Figure 1B). The Bonferroni adjusted Dunn post-hoc test revealed the serum neopterin level in the silicosis group (19.48 (16.53–26.51)) significantly decreased compared to the exposure (27.72 (19.53–35.38), adj. p-value=0.008) and non-exposed (28.32 (19.26–37.14), adj. p-value=0.015) groups.

Comparison of (A) serum neopterin and (B) urinary neopterin levels among the study groups. Each dot shows an individual neopterin level. p-Values were computed by the Kruskal-Wallis H test. *, **denote the statistically significant differences after multiple comparisons via the Dunn post-hoc test with Bonferroni adjustment.

The comparison of serum and urinary neopterin levels and immunological and oxidative stress parameters between simple and complicated silicosis is shown in Table 3. The TNF-α level was significantly higher in simple silicosis patients compared to complicated silicosis patients, while the GPx level was lower. We found no significant difference in FGF, IFN-γ, SOD, IL-1β, IL-1α, CAT, 8-OH-dG, GR, serum (Figure 2A), and urinary (Figure 2B) neopterin levels between simple and complicated silicosis patients. There was a significant and negative relationship between serum neopterin level and TNF-α (Spearman’s rho= −0.229, p=0.023) and duration of exposure (Spearman’s rho= −0.217, p=0.032).

The comparison of the serum and urinary neopterin levels, immunological and oxidative stress parameters between simple and complicated silicosis.

| Variables | Simple silicosis (n=53) | Complicated silicosis (n=18) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 157 (115–306) | 118 (109–132) | 0.0161 |

| FGF, pg/mL | 324 (264–403) | 398 (324–471) | 0.0871 |

| IFN-γ, pg/mL | 812 (651–831) | 740 (711–830) | 0.3781 |

| SOD, U/mL | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) | 0.04 (0.03–0.04) | 0.4231 |

| IL-1β, pg/mL | 272 (223–323) | 260 (191–325) | 0.4191 |

| IL-1α, pg/mL | 74.7 (70.0–76.8) | 72.4 (67–76.5) | 0.2711 |

| GPx, nmol/min/mL | 4.42±1.23 | 5.11±1.18 | 0.0422 |

| Catalase, U/mL | 1.03 (0.85–1.30) | 0.75 (0.24–1.58) | 0.3241 |

| 8-OH-dG, pg/mL | 2,590 (1780–3,805) | 2,770 (1,421–3,245) | 0.4081 |

| GR, nmol/mL/min × 103 | 4.17 (3.33–10) | 4.75 (3.04–10) | 0.5571 |

| Serum neopterin, ng/mL | 19.4 (17.3–23.8) | 19.8 (16.5–41.6) | 0.7211 |

| Urinary neopterin, ng/mL | 1,353 (1,013–1817) | 1,498 (1,014–1852) | 0.9571 |

-

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation or median with quartiles (1st quartile–3rd quartile), as appropriate. 1Mann-Whitney U test (Un-paired Wilcoxon test). 2Student’s t-test. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; SOD, superoxide dismutase; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-1α, interleukin-1α; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; 8-OH-dG, 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine; GR, glutathione reductase.

Comparison of (A) serum neopterin and (B) urinary neopterin levels between simple and complicated silicosis. Each dot shows an individual neopterin level. p-Values were computed by the Mann-Whitney U test (unpaired Wilcoxon test).

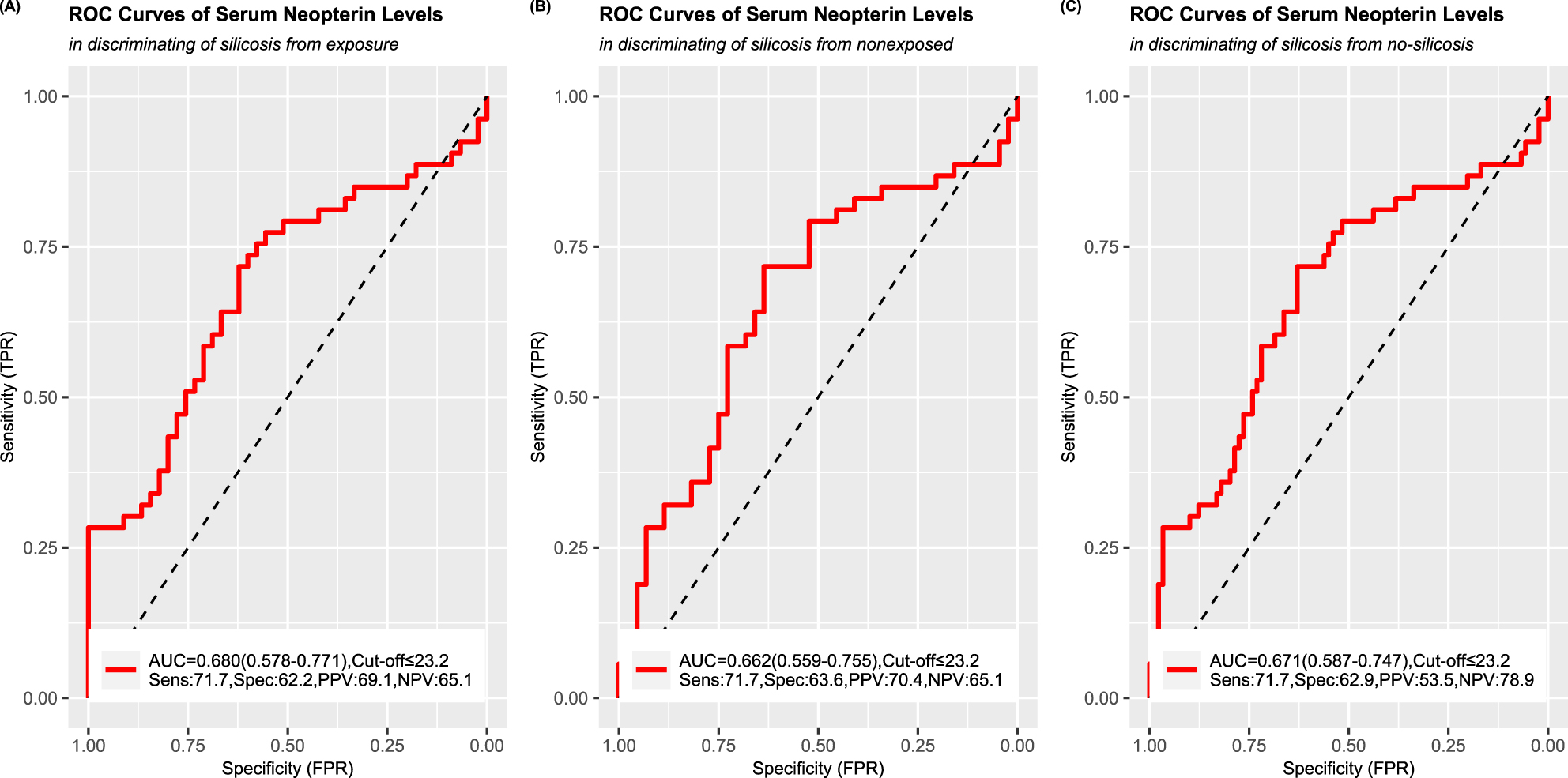

A ROC curve analysis for serum neopterin level as a biomarker for distinguishing silicosis from exposure showed that the AUC value was 0.680 (95 % CI, 0.578–0.771). The optimal cut-off value of serum neopterin was 23.2 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 71.7 %, a specificity of 62.2 %, a PPV of 69.1 %, and an NPV of 65.1 % (Figure 3A). The ROC curve AUC to discriminate silicosis from non-exposed serum neopterin levels was 0.662 (95 % CI, 0.559–0.755). 23.2 ng/mL of serum neopterin level was determined as the optimal cut-off point, with a resulting sensitivity of 71.7 %, specificity of 63.6 %, PPV of 70.4 %, and NPV of 65.1 % (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows a ROC curve that estimates the predictive capacity of the serum neopterin level in distinguishing silicosis from no-silicosis (including both exposure and non-exposed patients). The AUC value for silicosis diagnosis was 0.671 (95 % CI, 0.587–0.747). The optimal cut-off value of serum neopterin was 23.2 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 71.7 %, a specificity of 62.9 %, a PPV of 53.5 %, and an NPV of 78.9 %.

ROC curve analysis to distinguish patients with silicosis from (A) exposure, (B) non-exposed, and (C) no-silicosis (including both exposure and non-exposed patients).

To identify the risk factors associated with silicosis against individuals exposed to silica and non-exposed, multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted (Table 4), including the following variables with p<0.05 in the univariate analysis: age, duration of exposure (only for exposure), smoking status, FVC, FEV1, serum neopterin (≤23.2 vs. >23.2), IL-1α, and GR. Finally, the multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age, serum neopterin, and IL-1α were independent risk factors for the diagnosis of silicosis between patients with silicosis and those exposed to silica. Further, the multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age, FEV1 (%), serum neopterin, IL-1α, and GR were independent risk factors for the diagnosis of silicosis between patients with silicosis and those who were not exposed.

Analysis of multiple logistic regression models for the diagnosis of silicosis.

| Risk factors | Silicosis vs. exposure | Silicosis vs. non-exposed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95 % CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95 % CI) | p-Value | |

| Age, years | 1.114 (1.031–1.204) | 0.006 | 1.147 (1.028–1.279) | 0.014 |

| FEV1, % | – | 0.876 (0.805–0.954) | 0.002 | |

| Serum neopterin, ng/mL | 4.428 (1.669–11.746) | 0.003 | 26.145 (2.918–234.242) | 0.004 |

| IL-1α, pg/mL | 0.887 (0.809–0.972) | 0.011 | 1.528 (1.228–1.901) | <0.001 |

| GR, nmol/mL/min × 103 | – | 2.092 (1.286–3.405) | 0.003 | |

| Performance measures of model | ||||

| Overall model test statistics | 33.176 | 77.488 | ||

| p-Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Deviance | 102.027 | 40.521 | ||

| AIC | 110.027 | 52.521 | ||

| BIC | 120.367 | 67.316 | ||

| Nagelkerke’s R2 | 0.384 | 0.794 | ||

| Predictive performance measure of model at cut-off value of 0.5 | ||||

| Accuracy | 0.724 | 0.885 | ||

| Specificity | 0.667 | 0.833 | ||

| Sensitivity | 0.774 | 0.922 | ||

| AUC | 0.817 | 0.963 | ||

-

AIC, Akaike Information Criteria; BIC, Bayesian Information Criteria; AUC, area under the curve; FEV1, forced expired volume; IL-1α, interleukin-1α; GR, glutathione reductase.

Discussion

Studies evaluating neopterin levels in silica exposure are very limited and have been conducted in small populations. In some of the studies, only exposure and healthy groups were compared [18], 20], 21], while in others, silicosis and healthy controls were measured [22], 23]. No study has compared serum and urine neopterin levels among silicosis patients, exposed individuals, and healthy control groups. Therefore, neopterin levels in studies have not been able to distinguish between people with silicosis and silica exposure. We know that not all people exposed to silica develop silicosis. In studies conducted on individuals exposed to silica [18], 20], 21], it is not known whether individuals with elevated neopterin develop silicosis during follow-up. Therefore, biomarkers measured at exposures may not provide accurate information on disease development. Some of the studies measured neopterin only in urine [21], 22], and some only in serum [23], 24], while only two studies evaluated neopterin levels in both urine and serum [18], 20]. In our study, we evaluated serum and urine neopterin levels, oxidative stress and inflammation parameters in patients with silicosis, a silica-exposed cohort and a control group. We also demonstrated the relationship of these parameters with clinical, radiological and functional variables.

A study on silicosis patients revealed that urinary neopterin levels differed from those of controls, and neopterin levels linked with disease severity. It was emphasized that increased neopterin levels are an indicator of cellular immunity in silica exposure [22]. In another study, serum and urine neopterin levels were elevated in the silica-exposed group (n=22) compared to the healthy controls (n=20). It was emphasized that neopterin levels have diagnostic value in silica exposure and can be utilized for diagnostic and monitoring purposes. Urinary neopterin levels had increased in relation to duration of work exposure [20].

Serum neopterin levels were found to be significantly higher in silicosis patients compared to the control group. Elevated neopterin levels in silicosis patients are highlighted as an early marker of cellular immune response activity and macrophage contribution to the disease’s pathogenesis, serving as diagnostic criteria alongside characteristic radiomorphological alterations [25]. A study conducted at an insulator manufacturing facility found that urine and serum neopterin levels were significantly higher in the group exposed to silica than in the unexposed group. Considering the sensitive and easy measurement of neopterin in biological fluids and the positive correlation between silica concentration in air and neopterin levels, more extensive studies in this field have been suggested. In a study conducted in glass sandblasting workers, it was emphasized that urinary neopterin could be evaluated as a biomarker of exposure to crystalline silica aerosols. However, no association was found between silica exposure and neopterin levels [21].

In our investigation, serum neopterin levels exhibited significant differences among the silicosis, exposure, and non-exposed group groups (respectively, 19.48 (16.53–26.51), 27.72 (19.53–35.38), 28.32 (19.26–37.14)) (p=0.003). No difference was found between the groups in terms of urine neopterin levels (p=0.678). In silicosis patients, serum neopterin levels were significantly lower than in both exposure and non-exposed groups. Serum neopterin levels were able to distinguish silicosis patients from exposure, non-exposed group, and non-silicosis (including both exposure and non-exposed) groups. The optimal cut-off value of serum neopterin was 23.2 ng/mL. Individuals with reduced serum neopterin levels (≤23.2 ng/mL) had a 4.4-fold higher risk of silicosis than the exposure group and a 26-fold higher risk than healthy individuals. Serum neopterin levels can predict the diagnosis of silicosis in 71 % of cases. Decreased neopterin levels in silicosis patients may indicate immunosuppression in the pathogenesis of the disease. While the increase in neopterin levels in silica exposure reflects the inflammatory response, the decrease in neopterin levels when silicosis develops suggests that it is a consequence of a reduced T-cell response. We recommend using serum neopterin levels as an early indicator to assess the risk of silicosis. When compared to silicosis and exposure groups, serum neopterin, age, and IL-1α levels were identified as risk factors for silicosis. In comparison to the silicosis and non-exposed group, we observed that GR and FEV1 (%) values heightened the probability of silicosis alongside these risk factors. The negative correlation between serum neopterin and duration of exposure has once again revealed the importance of neopterin in the evaluation of chronic exposure before the development of silicosis.

The differences in serum and urine neopterin levels of our patients may be due to the stability and sensitivity of serum and urine samples. Since serum neopterin levels tend to be more stable and sensitive, they may more accurately reflect the immune responses occurring in the body. Urine neopterin levels may fluctuate more depending on the hydration status of the individual and the time of sample collection [26], 27].

The relationship between neopterin levels and functional and radiologic parameters has not been comprehensively studied [18], 20], 21]. When Provake et al. divided silicosis into three groups: round, irregular small opacities, and large opacities, they found no difference in neopterin levels. The absence of a significant difference in neopterin levels among the three groups of silicosis patients indicates that macrophage activation is constant, while the radiological and morphological changes observed in the lungs are probably resulting from the additive impact of the activated cellular immune response [23]. In our study, serum and urine neopterin levels were found to be lower in simple silicosis compared to complicated silicosis, but the difference was not significant. There was no correlation between neopterin levels, the ILO profusion score, or functional parameters. There was no significant difference in neopterin levels between the silicosis categories. In the silicosis and exposure cohorts, FEV1 and FVC were reduced compared to the non-exposed group. Decreased FEV1 levels were a risk factor for the development of silicosis. DLCO, an early marker of interstitial lung diseases, was significantly lower in silicosis patients than in the exposure group.

A study on neopterin levels in transplant patients and those with infectious, inflammatory, and malignant diseases has demonstrated the important role of cellular immunity in these diseases [25]. Elevated neopterin formation and tryptophan catabolism may lead to “immunodeficiency” characterized by diminished T-cell responsiveness [17]. It is not known whether the individuals participating in the studies were questioned about conditions (e.g., autoimmune disease, cancer, infection) that may cause neopterin elevation [20], 28]. Therefore, attributing neopterin elevation solely to silica exposure may be questionable. Patients were included in our study after the exclusion of diseases that could cause neopterin elevation.

There are almost no studies evaluating neopterin, oxidative stress, and anti-inflammatory parameters together in silica exposure. Several recent studies have suggested that exposure to crystalline silica aerosols may affect immunological functions, including T lymphocytes, neutrophils, and immunoglobulins [20], 23]. A significant increase in IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels was found in ceramic workers with intense silica exposure, and it was emphasized that silica activates the immune system [13]. A study on cultures of cells sampled from rodent lung tissue showed that, after exposure to crystalline silica, IL-1α was rapidly released by alveolar macrophages, which stimulated IL-1β production and thus promoted lung inflammation [29]. Furthermore, the authors suggest that IL-1β biomarker levels can be used to assess the risk of silicosis among workers exposed to dust [30]. Studies have shown that TNF-α levels are elevated before the onset of clinical signs associated with silicosis, making TNF-α a valuable option for early diagnosis [31], 32]. A notable elevation in inflammation markers, such as TNF-α, FGF, IFN-γ, and IL-1α, was observed in the silicosis and exposure groups relative to the non-exposed group. The inflammatory response to silica was highest in the exposure group. In particular, the risk of silicosis increased 1.5-fold with increased IL-1α compared to healthy individuals. Neopterin and inflammatory markers tended to increase during the exposure period, while they tended to decrease with the effect of anti-inflammatory mechanisms when silicosis developed. Thus, neopterin may be considered a peripheral marker of respiratory epithelial damage that protects the airways against oxidative stress-induced inflammation.

Studies have shown that neopterin has great potential as a biomarker for early diagnosis of silicosis; nevertheless, measuring oxidative stress indicators is recommended for enhanced accuracy [26]. Glutathione (GSH) levels in red blood cells decrease in the initial stage of silicosis and increase in the later stages of the disease [33]; antioxidant levels in alveolar macrophages in the lung decrease in laboratory conditions following exposure to crystalline silica [34].

In another study, serum SOD, CAT, GPx, malondialdehyde (MDA), 8-OH-dG, IL-17, IL-23, and IL-27 levels were found to be higher in silicosis patients compared to the control group. It was emphasized that changes in inflammatory and oxidant/antioxidant systems may shed light on the mechanisms of silicosis [12]. Some studies have emphasized that plasma/serum MDA levels can be used as an indicator of lipid peroxidation, 8-OH-dG as a marker of oxidative stress, and glutathione levels as an indicator of antioxidant status in participants exposed to silica [11], 21], 35], 36].

In our study, 8-OH-dG, which is an indicator of oxidative DNA damage, was found to be increased in silicosis and exposure groups, while GPx and SOD, which are antioxidants among body defense mechanisms, were found to be low due to consumption. GR was higher in silica exposure (including both silicosis and exposure). We found a 2-fold increased risk of developing silicosis in individuals with elevated GR. The fact that serum neopterin levels are higher in silica-exposure patients than in silicosis patients supports oxidative stress, while lower levels in silicosis patients may indicate that neopterin contributes to antioxidant defense mechanisms in the body. When we compared simple and complicated silicosis patients, TNF-α among inflammatory markers was found to be high in simple silicosis patients, while GPx among antioxidants was found to be low. In the early period, defense mechanisms are activated along with the inflammatory response in silicosis patients.

The limitations of our study are that we were not able to perform a measurement analysis for the concentration of silica in the environment. Additionally, we were also unable to evaluate neopterin, immune, and oxidative parameters in bronchoalveolar lavage. If we had been able to perform these measurements, we could have evaluated the relationship between neopterin, immune, and oxidative parameters more clearly.

Conclusions

In summary, in our study, neopterin was able to differentiate silicosis from silica-exposed individuals who did not develop the disease, indicating that neopterin may be a biomarker that enables closer follow-up of exposed workers for silicosis in daily practice. Neopterin can be used to monitor the development and progression of the disease in periodic examinations in workplaces with silica exposure. Today, studies are needed to identify biomarkers for the development of disease from exposure. In light of these biomarkers, medical surveillance for early diagnosis in sectors with occupational exposures may contribute to reducing labor loss and disability rates.

-

Research ethics: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. This study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Gülhane Military Medical Academy on June 16, 2016, with the number 50687469-1491-450-16/1648-1572.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: Concept and Design: R.E., E.Ö., D.E. Supervision: D.E., R.E., Resource: D.E., R.E. Materials: D.E., R.E. Data Collection and/or Processing: D.E., R.E., E.Ö., D.E.O. Analysis and/or Interpretation: D.E., R.E., M.K.K. Literature Search: R.E., E.Ö, D.E. Writing: R.E., D.E. Critical Reviews: R.E., D.E. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by Selcuk University Scientific Research Project (grant code: 20401060).

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Werner, ER, Werner-Felmayer, G, Fuchs, D, Hausen, A, Reibnegger, R, Yim, JJ, et al.. Biochemistry and function of pteridine synthesis in human and murine macrophages. Pathobiology 1991;59:276–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000163662.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Murr, C, Fuith, L, Widner, B, Wirleitner, B, Baier-Bitterlich, G, Fuchs, D. Increased neopterin concentrations in patients with cancer: indicator of oxidative stress? Anticancer Res 1999;19:1721–8.Search in Google Scholar

3. Hoffmann, G, Wirleitner, B, Fuchs, D. Potential role of immune system activation-associated production of neopterin derivatives in humans. Inflamm Res 2003;52:313–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-003-1181-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Pingle, SK, Tumane, RG, Jawade, AA. Neopterin: biomarker of cell-mediated immunity and potent usage as biomarker in silicosis and other occupational diseases. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2008;12:107–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.44690.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Walters, EH, Shukla, SD. Silicosis: pathogenesis and utility of animal models of disease. Allergy 2021;76:3241–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14880.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Marrocco, A, Frawley, K, Pearce, LL, Peterson, J, O’Brien, JP, Mullett, SJ, et al.. Metabolic adaptation of macrophages as mechanism of defense against crystalline silica. J Immunol 2021;207:1627–40. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2000628.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Fubini, B, Hubbard, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) generation by silica in inflammation and fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med 2003;34:1507–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00149-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Kelly, B, Tannahill, GM, Murphy, MP, O’Neill, LA. Metformin inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species from NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase to limit induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and boosts interleukin-10 (IL-10) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages. J Biol Chem 2015;290:20348–59. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m115.662114.Search in Google Scholar

9. Gozal, E, Ortiz, LA, Zou, X, Burow, ME, Lasky, JA, Friedman, M. Silica-induced apoptosis in murine macrophage: involvement of tumor necrosis factor-α and nuclear factor-κ B activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:91–8. https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4790.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Castranova, V, Vallyathan, V. Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:675–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/3454404.Search in Google Scholar

11. Orman, A, Kahraman, A, Çakar, H, Ellidokuz, H, Serteser, M. Plasma malondialdehyde and erythrocyte glutathione levels in workers with cement dust-exposure silicosis. Toxicology 2005;207:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.07.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Kurt, O, Ergun, D, Anlar, H, Hazar, M, Aydin Dilsiz, S, Karatas, M, et al.. Evaluation of oxidative stress parameters and genotoxic effects in patients with work-related asthma and silicosis. J Occup Environ Med 2023;65:146–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000002701.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Anlar, HG, Bacanli, M, İritaş, S, Bal, C, Kurt, T, Tutkun, E, et al.. Effects of occupational silica exposure on oxidative stress and immune system parameters in ceramic workers in Turkey. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2017;80:688–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2017.1286923.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Huang, L, Nazarova, EV, Tan, S, Liu, Y, Russell, DG. Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo segregates with host macrophage metabolism and ontogeny. J Exp Med 2018;215:1135–52. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20172020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Mould, KJ, Barthel, L, Mohning, MP, Thomas, SM, McCubbrey, AL, Danhorn, T, et al.. Cell origin dictates programming of resident versus recruited macrophages during acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2017;57:294–306. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2017-0061oc.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Zhao, Y, Hao, C, Bao, L, Wang, D, Li, Y, Qu, Y, et al.. Silica particles disorganize the polarization of pulmonary macrophages in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020;193:110364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Wilmer, A, Nölchen, B, Tilg, H, Herold, M, Pechlaner, C, Judmaier, G, et al.. Serum neopterin concentrations in chronic liver disease. Gut 1995;37:108–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.37.1.108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Mohammadi, H, Dehghan, SF, Golbabaei, F, Ansari, M, Yaseri, M, Roshani, S, et al.. Evaluation of serum and urinary neopterin levels as a biomarker for occupational exposure to crystalline silica. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2016;6:274–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/amhsr.amhsr_140_16.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. ILO. Guidelines for the use of the ILO international classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

20. Altindag, ZZ, Baydar, T, Isimer, A, Sahin, G. Neopterin as a new biomarker for the evaluation of occupational exposure to silica. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2003;76:318–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-003-0434-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Mansour, RA, Behnam, R, Mohammad Ali, M, Mohammad, M, Sussan, S. Serum malondialdehyde and urinary neopterin levels in glass sandblasters exposed to crystalline silica aerosols. Int J Occup Hyg 2011;3:29–32.Search in Google Scholar

22. Palabiyik, SS, Girgin, G, Tutkun, E, Yilmaz, ÖH, Baydar, T. Immunomodulation and oxidative stress in denim sandblasting workers: changes caused by silica exposure. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 2013;64:431–7. https://doi.org/10.2478/10004-1254-64-2013-2312.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Prakova, G, Gidikova, P, Slavov, E, Sandeva, G, Stanilova, S. The potential role of neopterin as a biomarker for silicosis. Trakia J Sci 2005;3:37–41.Search in Google Scholar

24. Prakova, G, Gidikova, P, Slavov, E, Sandeva, G, Stanilova, S. Serum neopterin in workers exposed to inorganic dust containing free crystalline silicon dioxide. Cent Eur J Med 2009;4:104–9.10.2478/s11536-008-0084-0Search in Google Scholar

25. Fuchs, D, Weiss, G, Reibnegger, G, Wachter, H. The role of neopterin as a monitor of cellular immune activation in transplantation, inflammatory, infectious, and malignant diseases. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1992;29:307–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408369209114604.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Căluțu, IM, Smărăndescu, RA, Rașcu, A. Biomonitoring exposure and early diagnosis in silicosis: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Biomedicines 2022;11:100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11010100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Berdowska, A, Zwirska-Korczala, K. Neopterin measurement in clinical diagnosis. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001;26:319–29. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00358.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Ulker, OC, Yucesoy, B, Durucu, M, Karakaya, A. Neopterin as a marker for immune system activation in coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Toxicol Ind Health 2007;23:155–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233707083527.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Rabolli, V, Badissi, AA, Devosse, R, Uwambayinema, F, Yakoub, Y, Palmai-Pallag, M, et al.. The alarmin IL-1α is a master cytokine in acute lung inflammation induced by silica micro-and nanoparticles. Part Fibre Toxicol 2014;11:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-014-0069-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Zhou, T, Rong, Y, Liu, Y, Zhou, Y, Guo, J, Cheng, W, et al.. Association between proinflammatory responses of respirable silica dust and adverse health effects among dust-exposed workers. J Occup Environ Med 2012;54:459–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0b013e31824525ab.Search in Google Scholar

31. Blanco-Pérez, JJ, Blanco-Dorado, S, Rodríguez-García, J, Gonzalez-Bello, ME, Salgado-Barreira, Á, Caldera-Díaz, AC, et al.. Serum levels of inflammatory mediators as prognostic biomarker in silica exposed workers. Sci Rep 2021;11:13348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92587-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Slavov, E, Miteva, L, Prakova, G, Gidikova, P, Stanilova, S. Correlation between TNF-alpha and IL-12p40-containing cytokines in silicosis. Toxicol Ind Health 2010;26:479–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233710373082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Borm, P, Baste, A, Wouters, E, Slangen, J, Swaen, G, De Boorder, T. Red blood cell anti-oxidant parameters in silicosis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1986;58:235–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00432106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Zhang, Z, Shen, H-M, Zhang, Q-F, Ong, C-N. Critical role of GSH in silica-induced oxidative stress, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity in alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol 1999;277:L743–8. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.4.l743.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Liu, HH, Lin, MH, Liu, PC, Chan, CI, Chen, HL. Health risk assessment by measuring plasma malondialdehyde (MDA), urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OH-dG) and DNA strand breakage following metal exposure in foundry workers. J Hazard Mater 2009;170:699–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Sato, T, Takeno, M, Honma, K, Yamauchi, H, Saito, Y, Sasaki, T, et al.. Heme oxygenase-1, a potential biomarker of chronic silicosis, attenuates silica-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:906–14. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200508-1237oc.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2024-0302).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Unveiling the hidden clinical and economic impact of preanalytical errors

- Research Articles

- To explore the role of hsa_circ_0053004/hsa-miR-646/CBX2 in diabetic retinopathy based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification

- Study on the LINC00578/miR-495-3p/RNF8 axis regulating breast cancer progression

- Comparison of two different anti-mullerian hormone measurement methods and evaluation of anti-mullerian hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome

- The evaluation of the relationship between anti angiotensin type I antibodies in hypertensive patients undergoing kidney transplantation

- Evaluation of neopterin, oxidative stress, and immune system in silicosis

- Assessment of lipocalin-1, resistin, cathepsin-D, neurokinin A, agmatine, NGF, and BDNF serum levels in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Regulatory nexus in inflammation, tissue repair and immune modulation in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: PTX3, FGF2 and TNFAIP6

- Pasteur effect in leukocyte energy metabolism of patients with mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19

- Thiol-disulfide homeostasis and ischemia-modified albumin in patients with sepsis

- Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and oxidative imbalance: evaluation of ischemia-modified albumin and oxidant stress

- Antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of flavonoids isolated from fermented leaves of Camellia chrysantha (Hu) Tuyama

- Examination of the apelin signaling pathway in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Integrating network pharmacology, in silico molecular docking and experimental validation to explain the anticancer, apoptotic, and anti-metastatic effects of cosmosiin natural product against human lung carcinoma

- Validation of Protein A chromatography: orthogonal method with size exclusion chromatography validation for mAb titer analysis

- The evaluation of the efficiency of Atellica UAS800 in detecting pathogens (rod, cocci) causing urinary tract infection

- Case Report

- Exploring inherited vitamin B responsive disorders in the Moroccan population: cutting-edge diagnosis via GC-MS profiling

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor: “Gene mining, recombinant expression and enzymatic characterization of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Unveiling the hidden clinical and economic impact of preanalytical errors

- Research Articles

- To explore the role of hsa_circ_0053004/hsa-miR-646/CBX2 in diabetic retinopathy based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification

- Study on the LINC00578/miR-495-3p/RNF8 axis regulating breast cancer progression

- Comparison of two different anti-mullerian hormone measurement methods and evaluation of anti-mullerian hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome

- The evaluation of the relationship between anti angiotensin type I antibodies in hypertensive patients undergoing kidney transplantation

- Evaluation of neopterin, oxidative stress, and immune system in silicosis

- Assessment of lipocalin-1, resistin, cathepsin-D, neurokinin A, agmatine, NGF, and BDNF serum levels in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Regulatory nexus in inflammation, tissue repair and immune modulation in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: PTX3, FGF2 and TNFAIP6

- Pasteur effect in leukocyte energy metabolism of patients with mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19

- Thiol-disulfide homeostasis and ischemia-modified albumin in patients with sepsis

- Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and oxidative imbalance: evaluation of ischemia-modified albumin and oxidant stress

- Antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of flavonoids isolated from fermented leaves of Camellia chrysantha (Hu) Tuyama

- Examination of the apelin signaling pathway in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Integrating network pharmacology, in silico molecular docking and experimental validation to explain the anticancer, apoptotic, and anti-metastatic effects of cosmosiin natural product against human lung carcinoma

- Validation of Protein A chromatography: orthogonal method with size exclusion chromatography validation for mAb titer analysis

- The evaluation of the efficiency of Atellica UAS800 in detecting pathogens (rod, cocci) causing urinary tract infection

- Case Report

- Exploring inherited vitamin B responsive disorders in the Moroccan population: cutting-edge diagnosis via GC-MS profiling

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor: “Gene mining, recombinant expression and enzymatic characterization of N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase”