Abstract

Objectives

We measured the serum periostin levels in patients with DLBCL and determined whether the levels reflected the clinical findings.

Methods

This was a case-control study. DLBCL patients diagnosed between March 2021 and October 2021 (n=36) and healthy volunteers (n=36) (Control group) were included. The serum periostin levels of the two groups were compared. Moreover, subgroup analyses were conducted in the patient group.

Results

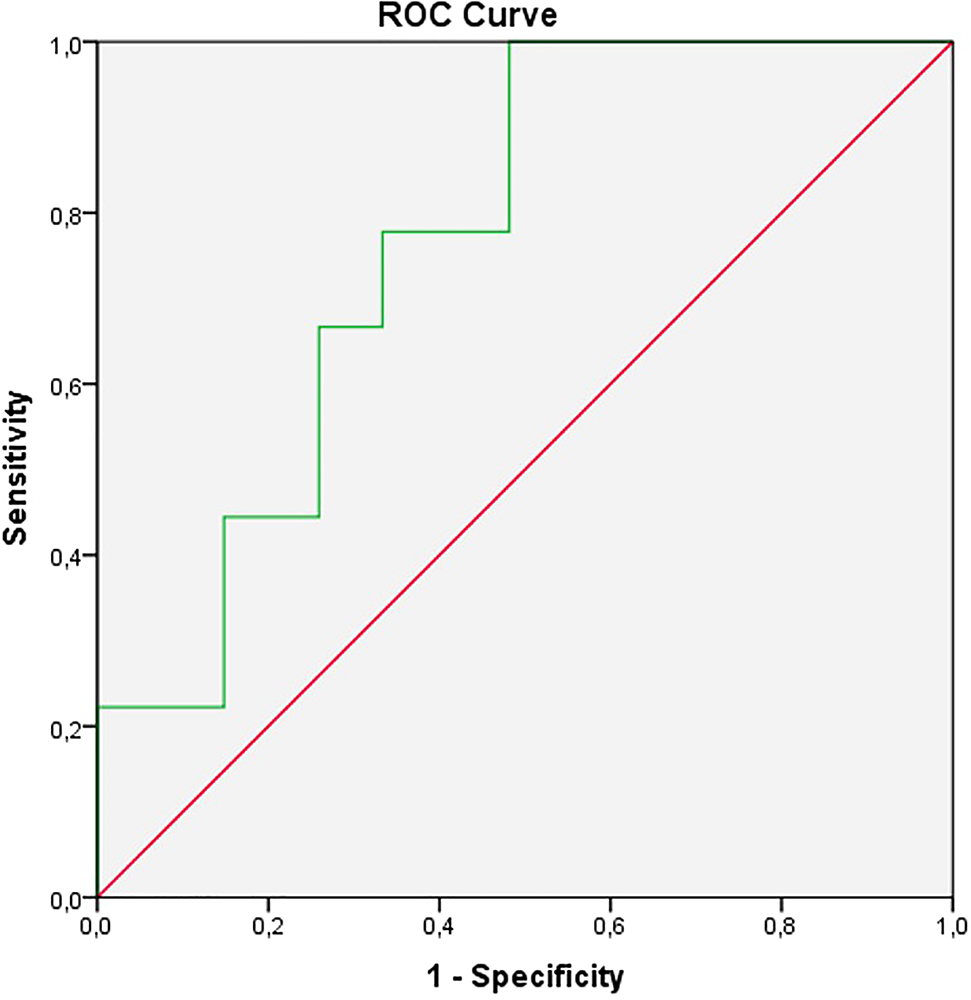

The serum periostin level was significantly higher in the patient than the control group (28.8 ± 3.2 vs. 15.1 ± 7.5 ng/mL, p=0.017). On subgroup analyses, the median serum periostin level of nine (25%) patients with bone marrow involvement was higher than that of the 27 (75%) lacking bone marrow involvement (12.7 vs. 21.7 ng/mL, p=0.018). On ROC analysis, the optimal periostin cutoff for bone marrow involvement was 17.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 77%, specificity 67%, AUC 0.765; 95% CI; 0.606–0.924, p=0.018). By the disease stage, the periostin level was higher in stage 4 patients than in those of other stages (21.3 vs. 12.0 ng/mL, p=0.029).

Conclusions

The periostin level correlated with such involvement; periostin may serve as a novel prognostic marker of DLBCL.

Introduction

Periostin (POSTN) is an extracellular matrix protein first identified in mice as an adhesion molecule and classified as an osteoblastic-specific factor. It was later termed POSTN due to the detection of its release from the periosteum in response to mechanical stress [1]. POSTN is produced in various tissues and plays a role in fibrosis, atherosclerosis, and angiogenesis. The level of POSTN is increased in solid organ tumors such as breast, lung, and gastrointestinal system tumors, and a high POSTN level is a risk factor for mortality [2]. In particular, subgroup analyses of patients with lung adenocarcinoma have revealed that POSTN is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with bone metastases [3]. In patients with pathological bone fractures, and in those with multiple myeloma (MM) and lytic lesions, the level of POSTN increases due to an increase in the expression of activin A, which is a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) family [4].

Data on the relationship between POSTN and hematological malignancies other than MM are limited to animal experiments. In vitro studies have shown that POSTN is among the extracellular matrix proteins required for the proliferation of progenitor B cells [5]. Ma et al. found that high POSTN levels lead to the progression of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in mice [6].

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) accounts for 25–30% of all lymphomas and is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma [7]. The International Prognostic Index (IPI), which is calculated with consideration of age, stage, performance status, extranodal involvement, and the serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, is a significant determinant of DLBCL prognosis [8]. Bone marrow involvement is observed in nearly 11–34% of patients at the diagnosis [9]. The sensitivity of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for detecting bone marrow involvement has been reported as 92–100% [10]. Nevertheless, bone marrow biopsy, which is an invasive procedure, is still performed in many centers.

This study investigated serum POSTN and determined whether the levels reflected the clinical findings in patients diagnosed with DLBCL.

Materials and methods

The study had a case-control design and was planned to include 36 participants in both groups (1:1 ratio) with 80% power, 5% type I error and 0.5 impact power to be predicted. The patient group consisted of patients diagnosed with DLBCL between March 2021 and October 2021, all of whom were older than 18 years and had no cardiac or pulmonary contraindications for treatment, or active infection, or chronic diseases, or malignancy history and the control consisted of healthy volunteers who presented to the internal medicine outpatient clinic. After obtaining informed consent from all participants, serum samples were collected from the control and patient groups before starting the treatment. Baseline laboratory data (hemograms, renal function tests, electrolytes, transaminases, liver function parameters, and C-reactive protein level) were obtained for both groups. The stage and risk level of patients were determined: PET/CT was used for staging and bone marrow biopsy was performed to evaluate bone marrow involvement in accordance with guidelines and our routine approach.

The primary endpoint of this study was to determine the serum POSTN level at diagnosis in DLBCL patients. We also investigated correlations between POSTN level and clinical manifestations.

Periostin

Serum samples from the patients and controls were centrifuged (37 °C for 10 min at 4,000 rpm) within 4 h and stored at −80° until the study day. The samples were analyzed in our biochemistry laboratory using human POSTN ELISA kits (Atlas Biotechnologies, Ankara, Turkey).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (ver. 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of the numerical variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) depending on the normality of the distribution. Two groups were compared with the independent samples t-test for normally distributed data, and with the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages (%). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine cutoff points, sensitivity and specificity. With regard to correlation analysis, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rho) was classified as follows: 0.2–0.4, weak; 0.4–0.6, moderate; 0.6–0.8, strong; and 0.8–1.0, very strong. The results were considered significant at p<0.05.

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Ethics Committee of Meram Faculty of Medicine, Necmettin Erbakan University (approval number: 2021/3407).

Results

The mean age was 61.4 ± 14.8 years in the DLBCL group and 61.9 ± 10.5 years in the control group (p=0.862). Both groups included 18 males and 18 females. The serum POSTN level was significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group (28.8 ± 3.2 vs. 15.1 ± 7.5 ng/mL, p=0.017). Table 1 lists the laboratory data of the two groups.

Periostin level and basic laboratuvary test on two groups.

| Parameters | Control (n:36) | Patient (n:36) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periostin, ng/mL | 15.1 ± 7.5 | 28.8 ± 3.2 | 0.017a |

| Hb, g/dL | 14.7 ± 1.5 | 11.6 ± 1.8 | <0.001a |

| WBC, 103/µL | 7.6 (6.3–8.8) | 8.3 (6.6–9.4) | 0.239 |

| PLT, 103/µL | 257.1 ± 57.7 | 293.2 ± 113.3 | 0.092 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 30.3 (25.1–39.6) | 33.4 (24.1–43.1) | 0.950 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.88 (0.77–1.0) | 0.80 (0.68–0.95) | 0.184 |

| Total protein, g/L | 74.1 (71.1–75.9) | 68.0 (60.6–74.7) | 0.002b |

| Albumin, g/L | 46.0 (44.2–47.6) | 37.0 (33.0–41.5) | <0.001b |

| LDH, IU | 190 (165–219) | 380 (230–620) | <0.001b |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.2 (3.9–5.8) | 5.4 (3.9–6.6) | 0.460 |

-

PLT, platelet; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase. aIndependent simple t test; bMann Whitney U test.

Overall, 4 (5.6%) DLBCL patients were stage 1, while 6 (8.3%) were stage 2, 8 (11.1%) were stage 3, and 18 (25%) were stage 4; the median POSTN levels were 10.4 ng/mL (range: 8.4–10.8 ng/mL), 21.2 ng/mL (range: 12.0–26.4 ng/mL), 11.3 ng/mL (range: 8.4–16.0 ng/mL), and 21.3 ng/mL (range: 12.9–7.7 ng/mL), respectively. The median POSTN level was significantly higher in the stage 4 subgroup compared to all other patients (21.3 vs. 12.0 ng/mL, p=0.029).

According to the IPI, 4 (5.6%) patients were low risk, 15 (41.6%) were low-to-moderate risk, 6 (16.6%) were moderate-to-high risk, and 11 (30.5%) were high risk. Low-and low-to-moderate-risk patients were compared to moderate-to-high- and high-risk patients in terms of median POSTN level, which was significantly higher in the latter subset of patients (11.4 vs. 20.2 ng/mL, p=0.016).

POSTN level was higher in patients with than without bone marrow involvement (21.7 vs. 12.7 ng/mL, p=0.018). Extranodal disease was present in 26 (72.2%) patients. The median POSTN level was also higher in patients with than without extranodal involvement (19.8 vs. 11.4 ng/mL, p=0.015). In analyses excluding cases of bone marrow involvement, although the POSTN level was higher in the 17 (63%) patients with extranodal involvement compared to the 10 (37%) patients without extranodal involvement, the difference was not significant (16.5 vs. 11.3 ng/mL, p=0.098). POSTN levels of DLBCL patients were also analyzed according to sex and clinical characteristics (Table 2).

Serum periostin levels on DLBCL patients.

| n (%) | Periostin (median, IQR) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 (50.0) | 19.8 (11.4–26.7) | 0.467 |

| Male | 18 (50.0) | 15.3 (9.8–35.5) | |

| Stage | |||

| <4 | 18 (50.0) | 12 (9.7–19.6) | 0.029a |

| 4 | 18 (50.0) | 21.4 (12.8–77.7) | |

| Bone marrowinvolvement | |||

| Yes | 9 (25.0) | 21.7 (15.9–75.5) | 0.018a |

| No | 27 (75.0) | 12.7 (9.4–25.6) | |

| IPI risk group | |||

| Low and low-intermediate | 19 (52.7) | 11.4 (9.0–18.0) | 0.016a |

| High and high-intermediate | 17 (47.3) | 20.2 (13.6–65.6) |

-

CR, complete remission; IPI, international prognostic score. aMann Whitney U test.

In the ROC analysis, the optimal POSTN cut-off for bone marrow involvement was 17.3 ng/mL (sensitivity=77%, specificity=67%, AUC=0.765; 95% confidence interval: 0.606–0.924, p=0.018) (Figure 1).

The ROC analysis of serum periostin.

In Spearman’s correlation analysis in patient group, POSTN level was significantly correlated with LDH (rho=0.51, p=0.001) and uric acid (rho=0.37, p=0.026) levels.

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate that POSTN expression is elevated in newly diagnosed DLBCL patients. Moreover, serum POSTN level was higher in patients with bone marrow involvement compared to those without. Finally, significant correlations were found between serum POSTN level and LDH (an IPI parameter) and uric acid (a marker of tumor burden) levels. These findings suggest that POSTN could serve as a clinical marker of bone marrow involvement in newly diagnosed DLBCL patients.

The first studies investigating POSTN focused on allergic and inflammatory diseases. The findings revealed that POSTN level is 2–3 times higher in pediatric than adult patients, that POSTN level is associated with the high osteoblastic activity seen in the bone marrow of children and that POSTN level decreases with age [11, 12]. The lack of any age difference between our patient and control groups enhanced the validity of the observed relationship between DLBCL and POSTN. In the other hand, median ages were similar between patients with bone marrow involvement and without involvement. In an observational study conducted in China, the POSTN level was non-significantly higher in females compared to males, similar to our findings [13].

Terpos et al. conducted a study on plasma cell diseases and found that serum POSTN level was higher in patients with MM, smoldering MM, and monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, compared to controls [4]. In this study, the serum POSTN level of MM patients was 537 ± 190 ng/mL; this was higher than both the control group and DLBCL patients (28.8 ± 3.2 ng/mL). Terpos et al. reported a higher bone marrow POSTN level in MM patients with lytic lesions compared to those without such lesions. These findings indicate POSTN involvement in bone turnover and resorption. POSTN is upregulated by activin A (a TGF-β pathway protein) in cases of MM and bone metastasis [14]. Our patients with bone marrow involvement did not have lytic bone lesions, although their POSTN levels were relatively high.

POSTN exerts functional effects by stimulating the Akt signaling pathway; this process involves integrin and integrin-ligand interactions. POSTN is secreted by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells, as well as by cells involved in inflammatory processes. In vitro experiments have revealed that POSTN deficiency reduced the effects of the Akt signaling pathway and cell cycle in bone marrow, thus inhibiting the differentiation of B-cell progenitors [5]. Another study found that B-cell progenitors increased POSTN secretion by stimulating mesenchymal cells through chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) [6]. Together, these results suggest that malignant lymphoma cells infiltrating bone marrow may increase POSTN secretion by stimulating bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells. We did not elucidate the pathophysiological mechanism, but we believe that this could be clarified by in vitro experiments of bone marrow POSTN levels and cell–cell interactions in patients with bone marrow involvement.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between serum POSTN level and other clinical and laboratory parameters in various diseases. Positive correlations were found between serum POSTN level and LDH levels, β2-microglobulin expression, and disease stage in MM patients [4]. Another study found that POSTN level was higher in patients with advanced-stage prostate cancer [15]. A high POSTN level has also been associated with breast cancer-related mortality [16]. As noted above, we found a significant correlation between POSTN and LDH levels. Moreover, POSTN level was high in stage IV patients and those with extranodal disease without bone marrow involvement. These findings suggest that a high POSTN level could serve as a marker of an unfavorable prognosis for DLBCL. A high LDH level, extranodal involvement, and stage IV disease all increase the IPI, which may explain the higher POSTN level of our moderate-and moderate-to-high-risk IPI groups.

One limitation of this study is that bone marrow POSTN level was not measured. Additionally, we did not analyze treatment responses, progression, or overall survival. Nevertheless, our study makes a contribution to the literature in terms of finding the POST level higher in patients with DLBCL than in the healthy population. We believe that evaluation of treatment responses, progression, and overall survival will strengthen our study. On the other hand, positive correlations were obtained between prognostic markers such as LDH and POSTN. In addition, serum POSTN level was found to be higher in DLBCL patients with bone marrow involvement compared to those without. Bone marrow involvement in DLBCL carries the disease to the 4th stage, that is, to the advanced stage, and its known that the prognosis of those patients is worse than that of earlier stage patients. This condition highlights the importance of demonstrating bone marrow involvement.

As a consequence, it is thought that serum POST level can be used as a marker to demonstrate bone marrow involvement which means advanced stage in DLBCL patients.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Author contributions: Atakan Tekinalp: Conceptualization, Methodology, Statistical Analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing, Taha Ulutan Kars: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Ali Kursat Tuna: Data curation, Resources, İbrahim Kılınç: Laboratory analysis and editing, Sinan Demircioglu: Writing–original draft. Özcan Çeneli: Writing–review & editing.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest including specific financial interests, relationships, and/or affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials included.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Ethics Committee of Meram Faculty of Medicine, Necmettin Erbakan University (approval number: 2021/3407).

References

1. Merle, B, Garnero, P. The multiple facets of periostin in bone metabolism. Osteoporos 2012;23:1199–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1892-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Yang, T, Deng, Z, Pan, Z, Qian, Y, Yao, W, Wang, J. Prognostic value of periostin in multiple solid cancers: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Cell Physiol 2020;235:2800–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29184.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Massy, E, Rousseau, JC, Gueye, M, Bonnelye, E, Brevet, M, Chambard, L, et al.. Serum total periostin is an independent marker of overall survival in bone metastases of lung adenocarcinoma. J Bone Oncol 2021;29:100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2021.100364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Terpos, E, Christoulas, D, Kastritis, E, Bagratuni, T, Gavriatopoulou, M, Roussou, M, et al.. High levels of periostin correlate with increased fracture rate, diffuse MRI pattern, abnormal bone remodeling and advanced disease stage in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 2016;6:e482. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2016.90.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Siewe, BT, Kalis, SL, Le, PT, Witte, PL, Choi, S, Conway, SJ, et al.. In vitro requirement for periostin in B lymphopoiesis. Blood 2011;117:3770–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-08-301119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ma, Z, Zhao, X, Deng, M, Huang, Z, Wang, J, Wu, Y, et al.. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell-derived periostin promotes B-ALL progression by modulating CCL2 in leukemia cells. Cell Rep 2019;26:1533–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Morton, LM, Wang, SS, Devesa, SS, Hartge, P, Weisenburger, DD, Linet, MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood 2006;107:265–76. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Zhou, Z, Sehn, LH, Rademaker, AW, Gordon, LI, LaCasce, AS, Crosby-Thompson, A, et al.. An enhanced international prognostic index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 2014;123:837–42. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-09-524108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Hantaweepant, C, Chinthammitr, Y, Khuhapinant, A, Sukpanichnant, S. Clinical significance of bone marrow involvement as confirmed by bone marrow aspiration vs. bone marrow biopsy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Med Assoc Thail 2016;99:262–9.Search in Google Scholar

10. El Karak, F, Bou-Orm, IR, Ghosn, M, Kattan, J, Farhat, F, Ibrahim, T, et al.. PET/CT scanner and bone marrow biopsy in detection of bone marrow involvement in diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170299. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170299.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Anderson, HM, Lemanske, RF, Arron, JR, Holweg, C, Rajamanickam, V, Gern, JE, et al.. Developmental assessment of serum periostin as an asthma biomarker in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:AB85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.323.Search in Google Scholar

12. Dikener, AH, Özdemir, H, Ceylan, A, Ünlü, A, Artaç, H. Serum periostin level and exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Asthma Allergy Immunol 2018;16:97–103.Search in Google Scholar

13. Tan, E, Varughese, R, Semprini, R, Montgomery, B, Holweg, C, Olsson, J, et al.. Serum periostin levels in adults of Chinese descent: an observational study ACTRN12614000122651 ACTRN 11 medical and health sciences 1102 cardiorespiratory medicine and haematology. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2018;14:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0312-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Leto, G, Incorvaia, L, Badalamenti, G, Tumminello, FM, Gebbia, N, Flandina, C, et al.. Activin A circulating levels in patients with bone metastasis from breast or prostate cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 2006;23:117–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-006-9010-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Tischler, V, Fritzsche, FR, Wild, PJ, Stephan, C, Seifert, HH, Riener, MO, et al.. Periostin is up-regulated in high grade and high stage prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2010;10:273. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-273.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Nuzzo, PV, Rubagotti, A, Zinoli, L, Salvi, S, Boccardo, S, Boccardo, F. The prognostic value of stromal and epithelial periostin expression in human breast cancer: correlation with clinical pathological features and mortality outcome. BMC Cancer 2016;16:95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2139-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2022-0146).

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- The implication of molecular markers in the early stage diagnosis of colorectal cancers and precancerous lesions

- Research Articles

- What are the predominant parameters for Down syndrome risk estimation in first-trimester screening: a data mining study

- Comparison between liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and immunoassay methods for measurement of plasma 25 (OH) vitamin D

- Comparison of Barricor tube and serum separator tube in outpatients

- Effect of hemoglobin, triglyceride, and urea in different concentrations on compatibility between methods used in HbA1c measurement

- Evaluation of hemolysis interference and possible protective effect of N-phenyl maleimide on the measurement of small peptides

- Neuroprotective and metabotropic effect of aerobic exercise training in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Serum asprosin levels in patients with retinopathy of prematurity

- Neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelet/lymphocyte ratios as a biomarker in postoperative wound infections

- Relationship between dental caries and saliva’s visfatin levels, total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and total oxidant status (TOS)

- Might periostin serve as a marker of bone marrow involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma?

- A new approach for the pleiotropic effect of metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus

- IGFBP7 is a predictor of diuretic-induced acute kidney injury in the patients with acute decompensated heart failure

- Serum vitamin D receptor and fibroblast growth factor-23 levels in postmenopausal primary knee osteoarthritis patients

- Antioxidant activity of ethanol extract and fractions of Piper crocatum with Rancimat and cuprac methods

- Lycorine impedes 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene exposed hamster oral carcinogenesis through P13K/Akt and NF-κB inhibition

- Sublethal effects of acrylamide on thyroid hormones, complete blood count and micronucleus frequency of vertebrate model organism (Cyprinus carpio)

- Acknowledgment

- Acknowledgment

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- The implication of molecular markers in the early stage diagnosis of colorectal cancers and precancerous lesions

- Research Articles

- What are the predominant parameters for Down syndrome risk estimation in first-trimester screening: a data mining study

- Comparison between liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and immunoassay methods for measurement of plasma 25 (OH) vitamin D

- Comparison of Barricor tube and serum separator tube in outpatients

- Effect of hemoglobin, triglyceride, and urea in different concentrations on compatibility between methods used in HbA1c measurement

- Evaluation of hemolysis interference and possible protective effect of N-phenyl maleimide on the measurement of small peptides

- Neuroprotective and metabotropic effect of aerobic exercise training in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Serum asprosin levels in patients with retinopathy of prematurity

- Neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelet/lymphocyte ratios as a biomarker in postoperative wound infections

- Relationship between dental caries and saliva’s visfatin levels, total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and total oxidant status (TOS)

- Might periostin serve as a marker of bone marrow involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma?

- A new approach for the pleiotropic effect of metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus

- IGFBP7 is a predictor of diuretic-induced acute kidney injury in the patients with acute decompensated heart failure

- Serum vitamin D receptor and fibroblast growth factor-23 levels in postmenopausal primary knee osteoarthritis patients

- Antioxidant activity of ethanol extract and fractions of Piper crocatum with Rancimat and cuprac methods

- Lycorine impedes 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene exposed hamster oral carcinogenesis through P13K/Akt and NF-κB inhibition

- Sublethal effects of acrylamide on thyroid hormones, complete blood count and micronucleus frequency of vertebrate model organism (Cyprinus carpio)

- Acknowledgment

- Acknowledgment