A Transfer of Language and Culture: German Bread and Pastries and Their Names in Kosovo

-

Vjosa Hamiti

Vjosa Hamiti is an associate professor in the Department of German Studies at the University of Prishtina in Kosovo. She holds a BA (1996) and MA (2006) from the same institution, as well as a PhD in linguistics (2014) from the University of Vienna, where she also completed her postdoctoral studies (2018). Her research interests include pragmatics, contrastive linguistics, discourse analysis, and translation. She has published extensively in both national and international academic journals.and Lumnije Jusufi

Lumnije Jusufi is an Albanologist and linguist. She is a senior lecturer (Privatdozentin ) in the Institute of Slavic and Hungarian Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin, where she was awarded her habilitation in 2021. She holds a PhD from the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich (2009). In 2022 and 2024, she was a Humboldt fellow in Tirana, Albania. In her research, she studies migration and border studies through sociolinguistics.

Abstract

This article examines the linguistic and cultural influence of German bread culture in Kosovo, where bread holds significant meaning as a symbol of hospitality and community. The introduction of German bread products, driven by migration and economic changes, has transformed Kosovar “bread habits”. The Buka and Premium bakeries have played a crucial role in promoting German bread names and products, capitalising on their perceived prestige and association with healthy eating trends. The article researches German–Albanian relations and shows that there is intensive interaction especially in the area of food. This connection, along with the legacy of its former status as part of Yugoslavia, migration, and the presence of German-speaking institutions in Kosovo, highlights the role of bread as a culinary, language, and cultural link. Using the methodological lens of language and cultural transfer, the study demonstrates the significant influence of German bread culture on Kosovo’s bread-making practices and food culture.

Introduction

In his book Our Daily Bread: A Meditation on the Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bread throughout History, the Croatian writer and literary scholar Predrag Matvejević highlights the fundamental role of bread, serving as it does not only as a staple food but also as an important cultural artefact (Matvejević 2020, 7). The significance of bread is deeply rooted in the Albanian language and culture, including in Kosovo (Hamiti, Sadiku, and Rexhepi 2018; Hamiti and Dushi 2023; Hamiti and Sadiku 2018). Kosovo’s Albanians experienced a different historical trajectory to Albanians in Albania. In socialist Yugoslavia, the territory of today’s Kosovo was an autonomous province within the Socialist Republic of Serbia (Malcolm 1999; Schmitt 2008). In the context of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Kosovo’s autonomy was abolished by Slobodan Milošević’s regime, which exacerbated existing conflicts and led to the war of 1998–1999. At the end of the war, Kosovo was a United Nations protectorate (1999–2008) and in 2008 it declared its independence (Judah 2008; Hamiti and Hamiti 2018). Despite its designation as a multicultural state in the aftermath of the conflict and through its internationally monitored constitution, Kosovo is, demographically speaking, predominantly Albanian.[1]

In the context of the Albanian cultural sphere, bread occupies a prominent position, as evidenced by its historical and cultural presence and its use in culinary idioms (Hamiti, Sadiku, and Rexhepi 2018), even in the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, the Medieval customary law of the Albanians. This was originally an oral legal system that governed the basic aspects of social behaviour in the isolated regions of northern Albania. The Kanun contains both pre-Christian and Christian elements (Gjeçovi 1989; Schmidt-Neke 2014).

The importance of bread in Albanian culture (as in many cultures) is reflected not only in the language used to describe it, but also in its symbolic meaning for community and cohesion. The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini endows bread with a profound symbolic significance that extends far beyond its role as a staple food (Cara and Margjeka 2015, 185). In Albanian tradition, bukë (“bread”) plays a pivotal role in establishing and maintaining social bonds and ethical obligations, particularly in the context of hospitality (Cara and Margjeka 2015, 179-80). The maxim Mikut do t‘i bahet nderë: bukë e krypë e zemër (“The guest must be honoured: bread and salt and the heart”) suggests that honour is bestowed through bread, salt, and a welcoming heart (Gjeçovi 1989, 131), exemplifying the central role of hospitality as an enduring principle. Bread is thus more than mere physical sustenance; it also carries a deeply embedded symbolic function, underpinning the moral code of Albanian society.

When it comes to both language and cultural transfers, the prevailing argument is that contact with other languages and cultures leads to such transfers in areas that are undergoing change, thereby closing supposed gaps in one’s own language and culture, or opening up new fields. However, Albanian–German relations date back to the 13th century, when the Saxons started engaging in mining in the territory of present-day Kosovo (Gashi 1995; Gashi 2015). With the Ottomans’ conquest of today’s Albanian-speaking areas in the mid-15th century, this contact ceased for centuries, only to be resumed in a completely different form in the context of the colonialist efforts of Austria–Hungary and the German Empire and then Nazi Germany in the World Wars (Csaplár-Degovics and Jusufi 2020; Langer 2019; Zaugg 2016). In terms of language and culture transfer, very little happened during any of these phases.

After the Second World War, however, Albanian–German relations intensified and acquired a different nature. In the 1960s, there was a bilateral agreement between Yugoslavia and West Germany allowing the recruitment of Yugoslav “guest workers” (Gastarbeiter). This triggered migration which then became the main connection between the two cultures and languages (Novinšćak Kölker 2016). When Yugoslavia disintegrated in the 1990s, these “guest workers” were followed by other migrants, not only the families of the original workers, but also other compatriots, including the refugees fleeing the 1999 Kosovo War. Many of these eventually returned to their homeland (Kadriu 2024). As a consequence of the war, German–Albanian interaction acquired a third component in the form of the activities of German-speaking institutions within the framework of the international presence in Kosovo. Germany participated in the Kosovo Force (KFOR), the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), and the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) and there were also German-speaking embassies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Cultural and language interaction in the realm of culinary traditions stem from these recent developments. Germany’s close association with bread came to have a significant bearing on the baking and eating culture in Kosovo. Artisanal skills were transferred, as was a specialised language associated with the field of baking. The Buka Bakery chain in Kosovo describes itself as having its origins in Germany, specifically a bakery in the Ruhr Valley area near the city of Essen,[2] and presents as evidence the types of bread on offer as well as their names and the specialisation of the bakers working there.[3] In this article, we discuss the transfer of German language and culture in bread production.

The primary hypothesis advanced in this article is that the German cultural and language transfer we describe entered Kosovo directly after the 1999 conflict. Earlier Germanisms, several of which we mention, came to Kosovo’s Albanian-speaking population in the context of the former Yugoslavia and mostly via the Serbo-Croatian language. However, not only does Yugoslavia no longer exist, but the Serbo-Croatian language has ceased to be dominant in Kosovo, and in fact continues to carry strong negative connotations (Munishi 2020). Following Espagne and Werner’s (1985) conceptualisation of cultural transfer, the mediators (Ger. Mittler) in these recent bilateral transfers between Germany and Kosovo are the numerous and diverse Kosovar migrants in Germany. Our findings here are corroborated by our earlier studies conducted in the linguistic fields of technology (Jusufi 2023) and consumer goods (Hamiti and Dushi 2023).

State of Research

In our study, we took a multidisciplinary approach, focusing on the nexus between cultural studies, history, and linguistics. There has been a notable increase in linguistic research on the contact between Albanian and German (Maksuti 2009; Maksuti 2010; 2014]; 2015]; Sadiku and Ismajli 2017; Sadiku 2018; Sadiku and Hamiti 2021). In sociolinguistics, language contacts tend to be situated within the broader context of cultural interaction (Kadzadej and Hamiti 2020; Hamiti and Dushi 2023; Jusufi 2020; 2023]; Jusufi and Sadiku 2024). Other studies have examined the spread of the German language in Kosovo after the 1999 war (Hamiti and Ismajli 2020; Tichy and Ismajli 2022). There is a relatively limited body of research on this subject in political and historical studies, with notable exceptions that include analyses conducted at the state level (Dornfeldt and Seewald 2019), within the contexts of colonialism (Gostentschnigg 2017; Langer 2019; Csaplár-Degovics and Jusufi 2020), and migration (Novinšćak Kölker 2016). There is a marked lack of research in the field of cultural studies, specifically with regard to German–Albanian cultural contacts. Here, too, migration studies are the exception, as these do address aspects of cultural interaction (Pichler 2010; Leutloff-Grandits 2015; Novinšćak Kölker 2016).

The study of food as a cultural phenomenon spans a number of research fields and is an essential aspect of social history (Neumann 2001, 14; Ochs and Shohet 2006, 37). Historically, it is anchored in ideas and values that shape human behaviour in relation to food (Hirschfelder 2008: 368). Food is seen as an integral part of cultural identity (Tanner 1997; Neumann 2001; Goldstein and Merkle 2005; Kalinke, Roth, and Weger 2010; Hirschfelder 2013). In addition to meeting biological needs, food is underpinned by social and cultural markers, such as values, tastes, pleasures, rituals, symbols, and social relations (Den Hartog 1997; Grieshaber 1997; Neumann 2001; Meyer 2002; Aronsson and Gottzén 2011; Brombach 2011). The field of culinary studies distinguishes between food and nutrition as an action and system, on the one hand, and as a cultural good that is contingent on its context, on the other (Wierlacher 2008, 1-10). Linguistic research on food and nutrition includes semantic, pragmatic, phraseological, anthropological, and communicative/discursive studies that facilitate an understanding of the multilayered meanings and social contexts of eating habits (Szatrowski 2014; Riley and Paugh 2018; Mancuso 2021). Such a multidisciplinary perspective is also adopted in Matvejević (2020), who provides an insightful analysis of the cultural significance of bread, highlighting its religious, symbolic, and cultural dimensions.

Ethnological research on Albanian bread culture is limited. The eminent Kosovar ethnographer Mark Krasniqi (2005) employed the lens of bread culture to analyse Albanian hospitality. In his Mikpritja në traditën shqiptare (“Hospitality in the Albanian tradition”), he devoted a chapter to the rules and customs surrounding the sofra, the traditional round dining table. A key aspect of his discussion is the enduring reverence for bukë, which means both bread and food, in Albanian culture. In her work Nga djepi në përjetësi (“From the cradle to eternity”), Drita Statovci-Halimi presents a comprehensive typology of “folk food”, a detailed examination of traditional culinary practices (Statovci-Halimi 2014). Both Krasniqi and Statovci-Halimi consider food to be a central component of traditional hospitality and thus of folk cultural heritage (Canolli 2019, 37-42).

Methods

In our study, we employ the concept of language and cultural transfer as proposed by Michel Espagne and Michael Werner (1985]) and Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink (2008]). The term “language transfer” describes the process of transferring lexical, phonological, or grammatical structures from one language to another. This is frequently accompanied by the transfer of cultural connotations. In contrast, the term “cultural transfer” describes the process of transferring cultural practices, symbols, or meanings from one culture to another. Here, particular attention is paid to the mediator or Mittler (Espagne 1997a), which underpins the study of cultural transfer. In contrast to language contact, language transfer is merely a secondary process in the context of cultural transfer. Espagne later refined the concept and also placed it in the context of migration, studying, for example, the role of German winemakers in the south of France (Espagne 1997a; Espagne 1997b). Lüsebrink, drawing on intercultural studies, then placed the concept in the context of globalisation and Americanisation (Lüsebrink 2008). Both Espagne and Lüsebrink – the latter to a much greater extent – analyse in detail the factors involved in cultural transfer and the ways in which it takes place. At the heart of their work are processes of social transformation and their links with another culture and language. Both provide useful tools for the study of Albanian–German relations, namely through migration, transformation, and especially the prestige of the German language and culture among Albanians in general and those living in the area of the former Yugoslavia in particular (Jusufi and Sadiku 2024).

Empirical Data Collection

Our article is based on a broad empirical data base created using a variety of different approaches. We conducted extensive participant observation as customers in various supermarkets, bakeries, and at snack stands throughout Kosovo. Vjosa Hamiti monitored advertisements for German bakery products on all Kosovar TV channels. In April 2022, we studied the Buka Bakery chain and its products in detail, collecting empirical information in the bakery’s different branches about its range of products, their ingredients, customer preferences, and the customers themselves, compiling photographs, product and name lists, as well as ethnographic diaries. Last but not least, we were accompanied by photographer Linda Pagenelli (Berlin, Germany).

In March 2022, we conducted an in-depth interview with Raif Gashi, the proprietor of the bakery in question, and Bajram Rushiti, the managing director. The interview was recorded and transcribed and formed the basis of our qualitative analysis. The interviewees provided a comprehensive insight into the management, marketing strategies, and corporate values of their bakery, as well as the company’s history and relations with Germany. We collected the data using a semi-structured interview guide containing both targeted and open questions. We coded the transcripts in order to identify key patterns and themes.

In order to illustrate our qualitative analysis of the Buka Bakery, Table 1 presents an overview of the most important aspects addressed in the interview. These include an examination of the background and motivation behind the establishment of the German business partnership; an analysis of the cultural influences on the product development process; an investigation of the use of German ingredients and bread types; and a discussion of the challenges faced by the bakery. Furthermore, we examined social dimensions, such as health benefits and social responsibility, as well as the language aspects of communication and marketing. Additionally, we provide an overview of the Kosovar bakery industry, highlighting the cultural dimensions of economic and other pressures on traditional baking practices, especially the knowledge gaps and need to adapt in order to modernise the industry.

Qualitative analysis of the Buka Bakery.

| Area of Analysis | Content |

|---|---|

| Background and context | Recent developments in the bakery industry in Kosovo; impact of economic crises on bread quality and cultural significance; the interdependence between migration and Kosovar–German relations. |

| Cultural dimensions | The traditional Kosovar bakery is based on a combination of craftsmanship and knowledge transfer within the family, which has, for centuries, been a fundamental aspect of cultural heritage shaped by economic limitations and a lack of alignment with contemporary standards. A relative residing in Germany and employed by the German partner firm was viewed as an example to follow; German bakery products are perceived as more wholesome and nutritious. |

| Language dimensions | The product names draw on traditional German recipes, components, and artisanal techniques, the very essence of which cannot be reproduced through translation. |

| Economic challenges | In periods of economic instability, those engaged in the bakery trade were compelled to reduce expenditure and resorted more frequently to incorporating nutritionally deficient additives in their products. This resulted in a decline in the quality of the bread, which had implications for consumer health. |

| Knowledge gap and need to adapt | The traditional knowledge base regarding bread production was found to be insufficiently adapted to meet the demands of contemporary nutritional and commercial standards. This deficiency contributed to the dissemination of nutritionally substandard bread products, necessitating urgent reform. |

| Professional change | Traditionally, baking skills were acquired by the younger generation through practice within the family. At the Buka Bakery, theoretical and practical baking skills are taught, with instruction taking place in Kosovo and Germany. The company provides regular training courses for its employees in Germany. Its German partners also conduct frequent training in Kosovo. |

In our linguistic analysis, we had access to the ingredient order lists from the Buka Bakery. However, due to confidentiality constraints, we were unable to disclose these lists. We thus complemented our data with publicly accessible language samples, which included price labels displayed in retail settings as well as promotional materials from a variety of sources, including online platforms, print media, and television broadcasts.

The Linguistic and Cultural Significance of Bread

Bread serves not only as a staple food for much of humanity, but it also plays a crucial role in human cultural development (Brewer and Porter 1997). Its cultural significance covers various aspects that go beyond its function as food (Wotjak 2010, 424). The historical significance of bread is evidenced by many written records and traditions, with human diets and culinary practices evolving over time (Camporesi 1989). For example, sharing bread has promoted social bonding and served as an expression of solidarity, shaping community identity. Regional variations in bread making – use of different grains, baking techniques, and bread shapes, for instance – reflect cultural diversity (Bickel 2015). Bread also plays a special role in rites and myths. Prahl and Setzwein (1999, 17) point out that since the early modern period, religious ceremonies have influenced sensory perception and imagination. There is even historical evidence that in certain societies, “toxic substances” were added to the “bread of the poor” to supress hunger and prevent social unrest (Prahl and Setzwein 1999, 18). Proter (1989, 10), too, describes how in many cultures, various bread-making methods were used to alleviate feelings of hunger by deceiving the senses. The beginning of life is associated with rituals and myths involving bread (Buzilă and Băzgu 2005, 302; Imbrasienė 2005, 274; Poghosyan Haik 2005, 39), which thereby obtained mythical qualities in itself (Matvejević 2020, 39).

Albanian Bread Culture

In Albanian culture, it is customary to serve coffee, raki – “spirits made, typically in a home still, from distilled juice (usually grape or plum though it can be as exotic as apricot or quince) – similar to Italian grappa” (Gowing 2011, 245) – and bread as part of greeting friends (cf. Durham [1909] 2021). The ritual emphasises not only hospitality but also the importance of social ties. It includes the practice of picking up, blowing on, or kissing any bread that has fallen.[4] Any crumbs are collected from the floor immediately after the meal, as it is considered a sin to step on bread. Thus, Albanian culture, too, has rituals that emphasise the deep spiritual significance of bread, showing it reverence. Matvejević (2020, 88) even states that, in Albanian culture, bread is glorified to an almost divine status. He observes that this particular attitude towards bread is not found in the rest of the Balkans, or other regions for that matter.[5] The oath Pasha bukën! (“I swear to bread!”) is similar to Pasha zotin! (“I swear to God!”) and exists exclusively in Albanian, emphasising the unique connection between bread, language, and culture.[6]

Bread was seen as a symbol of divinity and sanctity, as British travel writer Edith Durham observed at the beginning of the 20th century: “Even the fiercely Catholic tribes of Nikaj migrate […] [to the Serbian-Orthodox monastery of Deçani] to fetch the small round loaves of holy bread distributed there, and regard ‘By the bread of Dechani’ as a binding oath” (Durham [1909] 2021, 374). On the other hand, Albanian culture also has curses that assign bread the power to harm or kill: të vraftë Zoti e të vraftë buka (“may God and bread kill you”), or simply të vraftë buka (“May bread kill you”), or të mytë buka (“bread shall kill you”) (Fishta [1937] 1999, 259). Thus, bread is significant enough for people to see it both as a life-giving food and as a potential tool of disaster or destruction. The phrase të vraftë buka jeme (“may my bread kill you”) is used metaphorically to describe a situation in which a person’s help or kindness is not properly appreciated or is abused by the other, that is it conveys the idea of ingratitude or misuse of kindness.

In Albanian, bread is understood as a meal. The expression ha bukë (“eating bread”) is used as a synonym for “eating” or A ke hangër bukë? (“Have you eaten bread?”) for “Have you already eaten?”. S’na lëshoi pa bukë (“They did not let us go without bread/food”), or Na priti me bukë (“They received us with bread”) both mean “They cooked for us”. Also widely used in Albanian is the expression po më hahet bukë (“I feel I need to eat bread”), which can be translated into other languages as “having a craving for bread”, i.e. “being hungry”. In addition, the same expression is used to mean “having an appetite”.[7]

The Evolution of Bread Culture in Kosovo

The recent evolution of bread culture in Kosovo and other Albanian-speaking regions remains a relatively under-researched topic. Personal experiences and insights gained through regular conversations with older female relatives were significant for our study.

Historically, the baking culture in the Albanian-speaking regions was characterised by the predominant use of three grain types: wheat, rye, and maize (Durham [1909] 2021, 80). This is due to the region’s climatic conditions, as all three were primarily summer grains (Pasqualone et al. 2004, 48). Until the 1980s, homemade sourdough was used as a leavening agent. For a long time, all three of the aforementioned grains were mainly ground into wholemeal flour in traditional mills (Alb. mulli/nj). Baking bread and other goods was largely done by women and culturally very important; it was a household chore carried out by every housewife. State bakeries were the only ones to provide sandwiches for working people, students, and schoolchildren; take-away meals or sandwiches are still not very common in Kosovo to this day. People did buy bread to take home, but only in exceptional cases and mainly in the towns and cities.[8]

As more people started to migrate to northern Yugoslavia, and from the late 1960s also to Western Europe, the region’s economy grew, even though Kosovo remained one of Yugoslavia’s poorest regions. As a result, however, the cultivation of cereals declined. Nowadays, white flour is purchased from state mills, and industrially produced yeast is commonly used. For Albanian families, type 500 wheat flour – in Germany known as type 550 – has become a symbol of social advancement. The introduction of type 550 white flour simplified the baking process and resulted in softer and more digestible bread with a white colour thought of as more attractive. Type 550 flour is slow to absorb liquids, such as milk or water, contributing to higher dough stability throughout the baking process. In addition, it is versatile enough to be used in a variety of baked goods beyond white bread, such as pizza bases, puff pastry, yeast pastries, quark dough, sponge dough, short crust pastry, sponge cake, and dumplings.[9] There has been no discernable social controversy surrounding the nutritional benefits of wholemeal flour.

When the Yugoslav market was disrupted due to the dissolution of the state and the eruption of the war at the beginning of the 1990s, many family-run bakeries emerged in Kosovo. It was at this time that there was a significant transition in bakery practices, which, as our Buka Bakery interviewees observed, was about the challenge of maintaining product standards: “There weren’t any ingredients, they used a lot of additives without regulation, there was no safety for […] the bakers. They were all family bakers, there were no controls. When we started in 2012, bakeries like ours were quite rare, indeed almost non-existent in Kosovo.”[10] With the increase of the formal employment of women after the end of World War II, housewives had to economise their time, and the bread culture fell victim to this development. With the onset of significant outward migration at the end of the 1960s, Kosovo’s economic situation improved somewhat due to remittances (Petreski et al. 2018), and more people could afford to purchase bread and baked goods rather than making them at home. To stop baking was seen as a way of displaying one’s wealth. However, consumption of bread and other bakery products remained stable in terms of quantity, despite a variety of changes in dietary habits. With home-baking receding and industrial yeast being introduced, bread became a form of fast food as it was readily available and inexpensive.

German Bread and Bakery Products and Their Names in Kosovo

During the transformation of Kosovo’s traditional bread culture, German bread culture was key and thus also played an important role when the Buka Bakery was founded in 2012. The English term “bakery” makes for a nice alliteration; local customers, though, habitually refer to it as Furra Buka, furra meaning “bakery” in Albanian.

How did German bread culture enter the Buka Bakery’s business concept? The idea was sparked by the owners’ relatives, who worked as bakers in Germany and noticed how digestive problems were never an issue among their customers. This transnational family connection resulted in substantial collaborative endeavours with German companies, which provided comprehensive assistance, sharing their expertise in the production of premium, healthy bread: “And then, based on that, they got in touch with that family member, who worked there and established connections. We held meetings with companies in Germany, who provided us with considerable support, including showing us how they bake their bread”.[11] This collaboration resulted in a shift in Kosovar baking practices, with a notable increase in the production of healthier and higher-quality baked goods. Germany’s influence on Kosovo’s bread culture has thus been shaped by a combination of migration and global trends towards both fast(er) food and healthy eating. Kosovo’s consumer culture has begun to be characterised by a greater emphasis on the healthier alternatives.

German Bakery Products in Kosovo

In Kosovo, bakery products have traditionally been a part of several types of meal, but were especially favoured at the evening meal. The German breakfast culture of eating Brötchen [ˈbʁøːtçən] (“bread rolls, small round loaves”) has also become popular. The mediators of this imported commodity were the migrants, as evidenced by the pronunciation of the word broçe [ˈbʁotçe], used by Albanian migrants in Germany. A large number of these migrants returned to Kosovo after the war of 1999 and again in even greater numbers after the wave of deportations from Germany in 2006 (Novinšćak Kölker 2016).

German bread rolls have truly revolutionised breakfast traditions in Kosovo. Instead of the traditional baked goods, which come with savoury fillings and in regional variations and are consumed without toppings, accompanied by yoghurt or ayran, people have moved on to broçe. These are topped with cheese, cold meat, or a sweet spread, just as they are in Germany, and are consumed with coffee and/or tea. Broçe can now be bought fresh in almost any bakery or frozen in almost any supermarket – but they are never home-baked.

While their consumption is associated with a rise in social status, they are not commonly seen as upscale cuisine. This is characteristic of postwar Kosovar society, in which migrants occupy an ambivalent social position. They have considerable purchasing power, or facilitate such spending capacity for their relatives at home, but they do not belong to the upper echelons of society, least of all the educated elite. Thus, for migrants, the German bread rolls that are a new part of Kosovar culinary culture are a symbol of social inclusion. In fact, due to its shape, the bread roll in traditional Albanian cuisine is known as kulaç which is an old loanword from Slavic languages, but Brötchen has replaced this term because it is deemed socially more advanced than the former old-fashioned, rural term (Jusufi 2020).

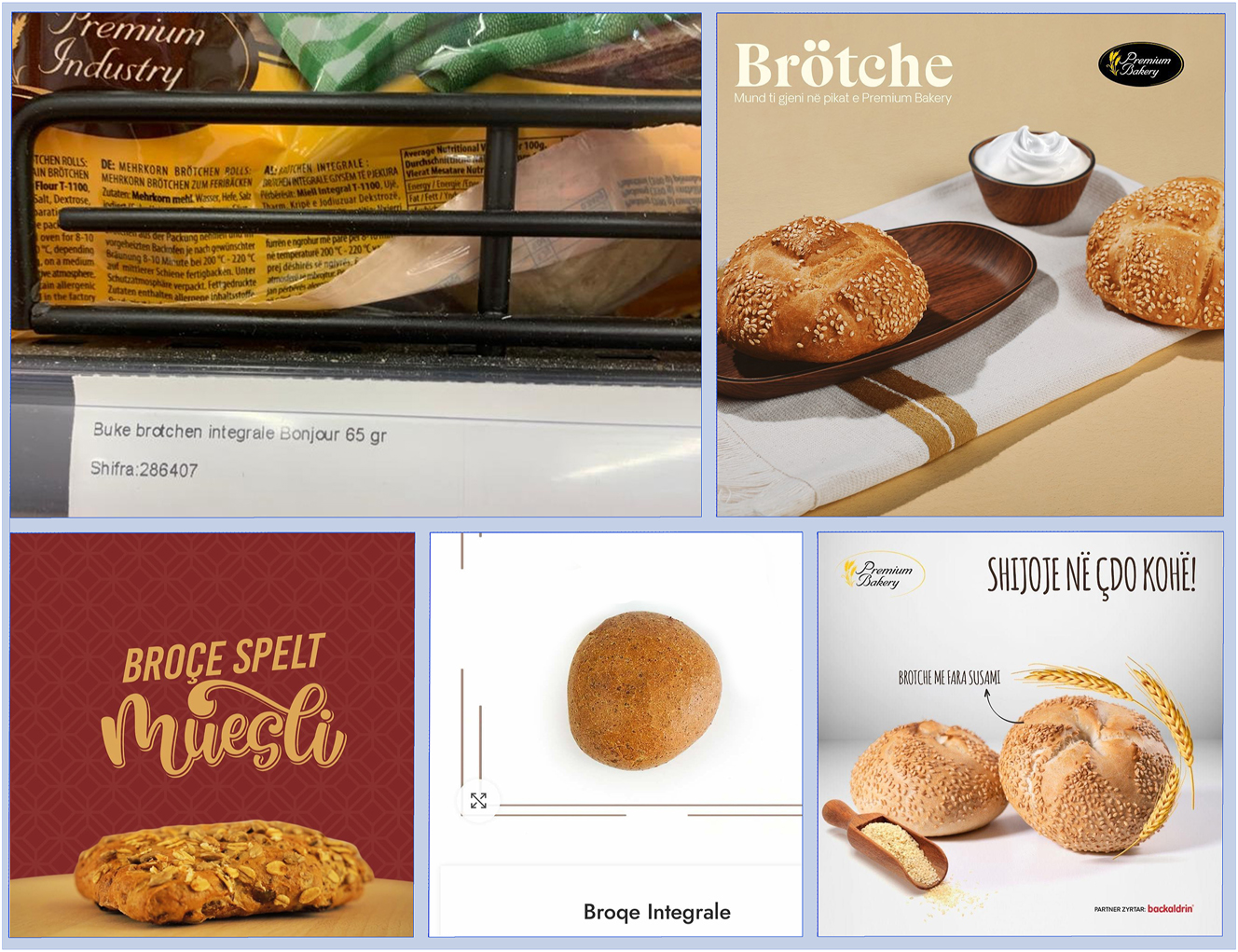

Broçe has several orthographic variants, including broqe, broche, brotche, brötche, and brotchen (Hamiti and Dushi 2023), which we gathered from print and TV advertisements as well as price tags in stores. Different variants even exist within a single company, such as the Buka Bakery or its competitor the Premium Bakery chain. The former uses the variants broçe and broqe, the latter, which entered the market shortly after Buka, brötche, brotche, and brotchen.[12] Sometimes, the German word Brötchen, in its Albanianised variant, is accompanied by the Albanian word for “bread”, bukë brotchen / brotche / brötche / broçe / broqe (Figure 1).

Brötchen in Albanianised varieties. Sources: Buka Bakery and Premium Bakery websites, https://bukabakery.com; https://www.premiumbakery.net/de/ (accessed 24 November 2024).

In advertising brochures, the word appears as broçe, as baget e rrumbullakët, meaning “round baguette”, or just as bukë, for example bukë Timalzer, meaning “Tim Mälzer bread”, in reference to the famous German TV chef. The supermarket chain Spar,[13] on the other hand, translates Brötchen as bukë rrethore meaning “round bread” (Figures 2 and 3). Spar was founded in the Netherlands in 1932 and has since spread worldwide, including to Albania in 2016, and from there to Kosovo in 2019.

Bukë Timalzer and baget i rrumbullakët, Buka Bakery, Prishtina; and bukë rrethore, Spar Bakery, Prishtina. Sources: Buka Bakery and Spar Kosova websites, https://bukabakery.com and https://spar-kosova.com (accessed 24 November 2024).

The range of “round bread” is wider however, as it includes products such as brecell < Ger. Brezel (Eng. pretzel), a word that entered Albanian in earlier times via Serbo-Croatian. But Brecell Bajerni (Eng. Bavarian pretzel), for example, are sold at the Spar supermarket, as are rollne (from German Rolle, which means “roll”), which are round and rolled up to form a snail-like shape, similar to the Swedish cinnamon rolls. Rollne can be filled with white cheese (rollne me djathë, “cheese roll”) or with poppy seeds (rollne me mak, “poppy seed roll”) (Figure 4). Similarly, the German loan translation xhep (Ger. Tasche; Eng. “pocket”) has been adopted from the German apple turnover, i.e. a long pastry filled with fruit compote.[14] In Kosovo, this item is sold with savoury fillings, as in xhep me domate dhe speca meaning “pocket with tomatoes and peppers” (Figure 5).

Rollne me mak (“poppy seed roll”) and Xhep me domate dhe speca (“pocket with tomatoes and peppers”), Buka Bakery, Prishtina, April 2022. Sources: Buka Bakery’s website, Prishtina, https://bukabakery.com (accessed 24 November 2024); and courtesy of Linda Pagenelli.

Overall, the selection of the second part of the German sweet Apfeltasche (Eng. apple turnover), i.e. Tasche (Eng. “pocket”) to create an Albanian culinary expression for a savoury bakery good is an interesting case. Albanian has different words for each of the German definitions of Tasche: for a pocket on clothing, it is xhep; for a briefcase or handbag, it is çantë; for a more general type of bag, it is torbë or qese. The concept of a Tasche as a container for a filling did not exist; no matter which of the meanings you choose, it is not quite right in Albanian. The choice of the pocket on clothing, i.e. xhep, seems idiosyncratic and not (yet) commonly accepted. For example, Spar uses the German term rollne or role < Ger.: Rolle, or even the widely known term kifle for this same product. The term kifle, derived from southern German (and Austrian) Kipferl, which is a type of croissant with or without a sweet filling, was introduced into Albanian in Kosovo via Serbo-Croatian, as these bakery goods are widespread throughout the region of former Yugoslavia.

In addition to the previously mentioned rollne me mak “poppy seed roll”, other sweet pastry categories include the berlina (Berliner, Eng. doughnut) (Figure 6). The spelling is adapted to the German pronunciation –-er > -a. The berlina in particular can be seen as a typical transfer by migrants via oral culture (Hamiti and Dushi 2023). In our interview, the owners of Buka Bakery drew a parallel between the adoption of what were originally German names in Albanian in Kosovo and the example of the French croissant: “Just as you cannot change a croissant, you cannot change a Berliner; it remains a Berliner.”[15] The transfer of both croissant and Berliner is not merely linguistic, but also cultural because, as postulated by Espagne and Lüsebrink, among others, these words signify objects that had no match in Kosovar and Albanian society.

Berlina, Buka Bakery advertisement. Source: Buka Bakery’s website, https://bukabakery.com (accessed 24 November 2024).

It is worth mentioning the pastry strudell/strudlle (Ger.: Strudel; Eng. strudel) here as it falls into the category of baked goods discussed in this section. Strudell is clearly another Germanism. However, it was already known in Kosovo before the 1990s, as it entered through the Yugoslav market as a product and through Serbo-Croatian as a word (Hamiti and Dushi 2023; Sadiku and Ismajli 2017).

German Bakery Products in Kosovo: The Influence of Healthy Eating Trends

Since the 1999 war, Kosovo has evolved both educationally and economically. Its wealthier social classes have embraced global healthy eating trends. The adoption of aspects of the German bread culture, however, came through Kosovo’s migrants, who do not necessarily belong to the better-off part of society. Thus, we find here an apt exemplification of Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Bourdieu [1979] 2010), in which he demonstrated how taste is not “personal”, but a reflection of social class and a means of strategy and competition. Those who are members of the higher social classes influence and shape the collective taste of a given society. In 2014, the UNESCO Commission granted German bread culture intangible cultural heritage status.[16] In today’s Kosovo, what are perceived as German bread products are significantly more expensive than traditional bread and baked goods.

One type of grain that was, until recently, completely unknown and certainly atypical in the region was spelt, also known as a winter grain and thus more suited to colder countries such as Switzerland and Germany. The fact that this type of grain was entirely unheard of in the Balkans until recently led to it being referred to by two German names: in Albania as Dinkel and in Kosovo as Spelt. Although the term spelt exists in English, people in Kosovo use the German pronunciation of sp- as shp-, clearly indicating a Germanism. Furthermore, the use of grains and seeds in and on bread and rolls is marketed as coming from Germany, and simultaneously as healthy. This practice, too, was unknown in traditional bread culture.

Sometimes, just a few grains strewn on the dough are enough for a bread product to be labelled bukë gjermane or “German bread”. Bukë/broçe me fara, “bread/rolls with seeds”, as well as bukë/broçe spelt, “spelt bread/rolls”, have also become common, as has bukë integrale, “wholegrain bread”. The latter is made from maize starch and buckwheat flour, without yeast. Its recipe is similar to two old types of local pastries known as leqenik, thin corn bread made with cold water, and krelanë e kallamojt, pastry made of corn and cheese. After the war of 1999, with recovery and changes setting in, people began to make both types of pastry from a mixture of maize and wheat flour, which was deemed healthier. The adoption of German bread types is quite widespread; its production and sales however have primarily been concentrated around the two major bakery chains Premium Bakery and Buka Bakery, the latter of which was the focus of our data collection.

When we inquired as to the rationale behind the decision not to translate the product names into Albanian, our interviewees responded that the product names proved untranslatable.[17] However, when it comes to marketing considerations, this lack of translation into Albanian is clearly also related to the prestige that Germany carries in Kosovo, and this goes beyond bread culture (Hamiti and Dushi 2023). Evidently, there are difficulties both in translating German bakery-related technical terms into the Albanian language in Kosovo and in adapting the terms from the German bread culture for Kosovo’s cultural context. Our interviewees employed the example of Fitnessbrot, “fitness bread”, to exemplify this untranslatability.[18] This product is promoted as being of exceptional quality, produced in Kosovo according to the original recipe and using the same premium ingredients as in Germany: “It is one hundred percent, meaning: the way we make it here is exactly how they make it there.”[19] Here prestige comes into play again, as with other “untranslatable” bread types. For example, the company circumvents the cultural bias that exists vis-à-vis certain grains in bread – such as barley or oats – due to their historical use as animal feed by naming it volkanbrot, from the German Vollkornbrot (spelled with the German v rather than the Albanian f), which means “whole grain bread” and sounds more sophisticated than any Albanian-language variant with similar ingredients that invokes the “old times”.

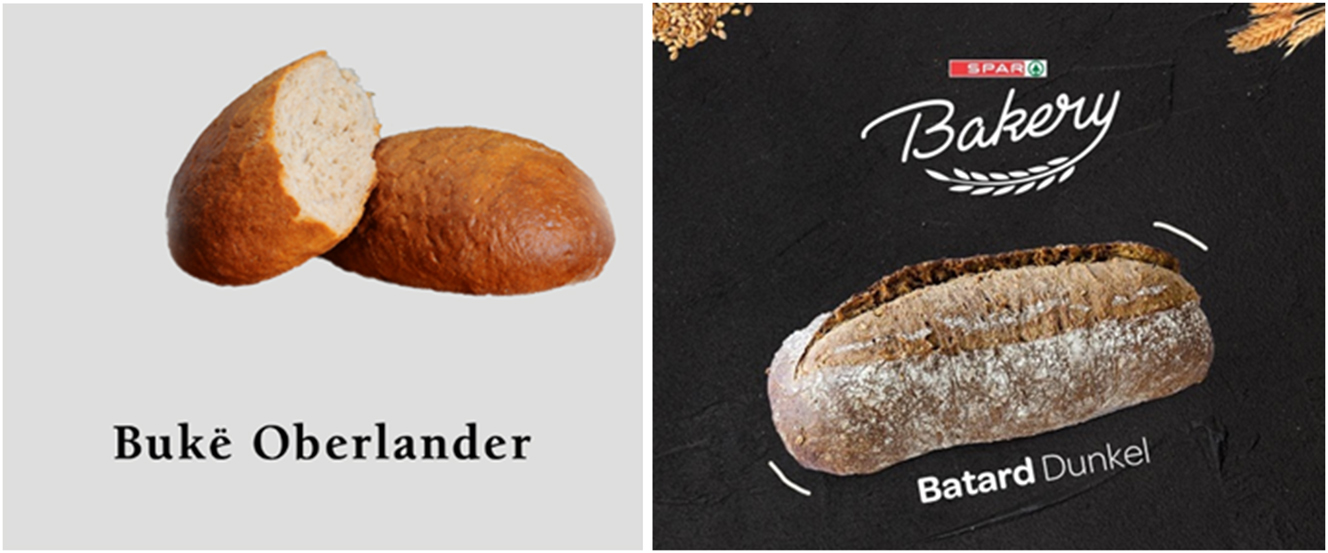

The German favourite Schwarzbrot, literally “black bread”, however, runs into cultural difficulties in the Albanian-language world. There is no direct translation or adaptation of the German Weißbrot, “white bread”, which translates as bukë e bardhë. The black variant, bukë e zezë, is problematic because the colour black carries a negative cultural connotation. For example, there is the adjective bukëzi, composed from bukë, “bread”, and zi, “black”, which effectively combines bread with the colour black, but signifies a stingy or inhospitable person. Again, there is the matter of traditional wholegrain farmer’s bread, which also has a negative association with bukë e zezë. Instead, the term Batard dunkel (“dark Batard”) is used, for example, by the Spar supermarket to sell this French type of bread, thus creating an enjoyable mix of linguistic transfers across Europe (Figure 10). To complete the picture, it is worth noting the existence of a Jugoslawisches Brot, “Yugoslav bread”, in the traditional bakery Fischer am Rathaus in Dortmund in the Ruhr Valley, which is the name it gives to its white bread variant.[20] The German language being considered synonymous with high quality in Kosovo’s new bread culture echoes other areas where this is also the case, such as technology, skilled trades, and personal hygiene products (Hamiti and Dushi 2023; Jusufi and Sadiku 2024). Examining the range of products offered by the two “Germanised” bakeries in Kosovo, it becomes evident that Buka Bakery offers a wider range (Table 2).

Bread varieties at Buka Bakery and Premium Bakery.

| Buka Bakery | |

|---|---|

| bukë gjermane | German bread |

| bukë integrale | Wholegrain bread |

| bukë dietale | Diet bread |

| bukë spelt | Spelt bread (Figure 8) |

| bukë spelt dinkelbrot | Spelt bread (in Albanian, with the addition of the German term) |

| bukë fitnesi | Fitness bread |

| bukë muesli | Muesli bread (note the German spelling ue instead of the Albanian y) |

| bukë volkanbrot | Wholemeal bread (Figure 7) |

| bukë e pjekur dy herë | Double-baked breada |

| bukë (shtëpie) me fara | (Home) grain bread |

| bukë me arra | Walnut bread |

| bukë Timalzer/Tim Malzer | Bread in the style of Tim Mälzer (Figure 2) |

| bukë Oberlander | Oberland bread (Oberländer is a bread from Cologne and the surrounding area) (Figure 9) |

|

|

|

| Premium Bakery | |

|

|

|

| bukë gjermane | German bread |

| bukë integrale | Wholegrain bread |

| bukë e përzier me fara | Mixed bread with grains |

| bukë thekre | Rye bread |

| bukë fitnesi | Fitness bread (Figure 8) |

-

Source: authors’ compilation. aThe “double-baked bread” is baked in two phases in order to create bread that remains edible for longer. For details, see https://www.homebaking.at/doppelt-gebackenes-brot/(accessed 28 November 2024).

Interestingly, alongside the brecell bajerni, “Bavarian pretzel” mentioned above, the bukë Oberlander is another bread type whose distinctively regional German origin was maintained in its transfer to Kosovo (Figure 9).

Resembling a typical German bakery: Volkanbrot, Bukë Spelt, and Bukë Fitnesi at a Buka Bakery branch in Prishtina, April 2022. Source: Courtesy of Linda Pagenelli.

Bukë Oberlander, Buka Bakery advertisement, and Batard Dunkel, Spar Bakery advertisement. Sources: Buka Bakery and Spar websites. Sources: https://bukabakery.com and https://spar-kosova.com (accessed 24 November 2024).

Buka Bakery and Premium Bakery thus represent a corporate culture that has succeeded in substantially changing Kosovo’s bread culture by introducing German-inspired products, to the point of putting traditional bread culture under pressure. Since opening its first location in Prishtina, Buka Bakery has expanded to 20 branches throughout Kosovo. Premium Bakery supplies several supermarket chains, including Viva Fresh,[21] where we found another German loan translation, pjekurina (<Germ. Backwaren), used as the collective term for “baked goods”, which however is not (yet) commonly used in Albanian. The supermarket chain Spar on the other hand demonstrates, via the bread language transfer, a difference between Albania and Kosovo. Spar does not use German names (except the aforementioned dunkel, “dark”) but its own idiosyncratic translations, as described above. Spar came to Kosovo via Albania, where Italian rather than German linguistic influences, especially in technology and the skilled trades, are much stronger (Jusufi 2023).

Advertising Bread

German bread products are promoted very professionally and exclusively by the Buka and Premium bakeries. The fact that advertising specifically for bread even exists deserves special consideration. In an Albanian culinary culture, bread and other baked goods form the core of traditional cuisine – so the promotion is hardly aimed at increasing bread consumption. Rather, it is mainly about fostering the universal trend of healthy eating, which the businesses tap into. This can be shown through the language as well.

In the past, the act of purchasing bread at a bakery in Kosovo was described as shkoj me ble bukë (“I am going to buy bread”), and this meant white bread by default. This was also mentioned by our interviewees: “They habitually used to say ‘we are going to buy bread’ […] We [in Kosovo] only had that kind of bread.”[22] Nowadays, there is wholemeal flour, and this is associated with German bread culture, which is also reflected in changes in language. Now the phrase shkoj te furra (“I am going to the bakery”) is in common usage, reflecting the shift from traditional practice to a wider acceptance and integration of wholemeal products into Kosovar diets. This has been strongly influenced by German bread culture. Our interviewees even related the medical advice they received in the process of deciding which kinds of bread to produce:

The deterioration in the quality of bread [in Kosovo] […] has pushed us, based on our personal experience with many food issues, to look for solutions. Every time we travelled, especially to Germany, we felt relief in our stomachs. After consulting with doctors, they suggested that bad quality bread may the problem. Avoid flour, avoid certain foods [they said].[23]

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate this new advertising world and testify to its level of professionalism. In Figure 11, beneath the “handmade” label, the bread is advertised as adhering to a “German recipe and quality” in both Albanian and English. The bread is filled with walnuts (arra) and grapes (rrush) and the advertisement recommends it is served with peanut butter, which is not something that is commonly used in Albanian cuisine.

Buka Bakery advertisement. Source: Buka Bakery’s website, https://bukabakery.com (accessed 24 November 2024).

Premium Bakery advertisement. Source: Premium Bakery’s website, https://www.premiumbakery.net/de/ (accessed 24 November 2024).

The two bakeries promote a health(y) trend, which is also reflected in the fact that they list their product ingredients. In Kosovo, for a long time, even industrially produced goods did not label ingredients on product packaging. Now, they can be found on bread, baked goods, and even on the price tags of unpackaged products, making everything much more transparent. According to our interlocutors from Buka Bakery, they received this idea from their German partner. Germany has a history of food labelling obligations that spans a few decades and since 2014, the same has been mandatory for all EU member states.[24] This transfer of good practice and knowledge from Germany to Kosovo may have implications beyond the mere health aspect. Yet, while the advertisements suggest that the products are healthy due to their ingredients, this is obviously not necessarily the case. Sometimes, the ads present the nutritional information in a way that resembles chemical charts, which may be difficult for customers to understand. Other adverts communicate seemingly objective health-related information to the customer, as in Figure 13, which claims that bukë dietale (“diet bread”) improves cholesterol levels (përmirëson kolesterolin).

Healthy bread, Buka Bakery advertisement. Source: Buka Bakery’s website, https://bukabakery.com (accessed 24 November 2024).

Premium Bakery on the other hand shows consumers what the grains used for making their mixed grain bread look like. These ads primarily target urban dwellers, who may not know what each type of seed and grain looks like (Figure 14). While both companies work to raise awareness of healthy bread and bakery products in Kosovar society, their main focus remains to successfully fill the market gap in Kosovo when it comes to the global trend of healthy eating.

Premium Bakery advertisement: mixed grain bread. Source: Premium bakery’s website, www.premiumbakery.net (accessed 25 November 2024).

Conclusion

As our study shows, bread has linguistic and cultural significance in the context of German–Albanian relations, particularly in Kosovo. In Albanian culture, as in many others worldwide, bread is a staple food as well as a symbol of cultural identity and community belonging. Bread is closely tied to traditional cultural practices and plays a central role in people’s daily lives. Beyond that, bread is revered, even considered divine and sacred in spiritual rituals and activities.

Migration to German-speaking countries since the 1960s, but especially in the context of the 1999 war, has contributed to the evolution of Kosovo’s bread culture. German-speaking institutions in Kosovo and the country’s economic transformation play a part too. Albanian returnees and transnational migrants from German-speaking countries in particular have introduced aspects of German bread culture and its bakery products, such as the Brötchen, to Kosovo, and these quickly gained popularity, as they were perceived as modern, convenient, and prestigious. Breakfast habits in Kosovo have changed due to introduction of the Brötchen.

We looked at how two bakeries, Buka and Premium, have significantly contributed to the spread of German bread names and products in Kosovo. The German terms have come to be seen as synonymous with the worldwide healthy eating trend. Advertising for German bread products highlight the quality and health benefits, and list the ingredients used, which further enhanced the acceptance and dissemination of these products. The two bakeries have thus successfully filled the market gap, capitalising on the entrepreneurial opportunity presented by the trend of German bread culture in Kosovo.

About the authors

Vjosa Hamiti is an associate professor in the Department of German Studies at the University of Prishtina in Kosovo. She holds a BA (1996) and MA (2006) from the same institution, as well as a PhD in linguistics (2014) from the University of Vienna, where she also completed her postdoctoral studies (2018). Her research interests include pragmatics, contrastive linguistics, discourse analysis, and translation. She has published extensively in both national and international academic journals.

Lumnije Jusufi is an Albanologist and linguist. She is a senior lecturer (Privatdozentin) in the Institute of Slavic and Hungarian Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin, where she was awarded her habilitation in 2021. She holds a PhD from the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich (2009). In 2022 and 2024, she was a Humboldt fellow in Tirana, Albania. In her research, she studies migration and border studies through sociolinguistics.

-

Research funding: Vjosa Hamiti received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Lumnije Jusufi conducted her research in the framework of the project “Migration and Cultural Transfer between Germany and the Albanian Western Balkans”, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (2019–2023) at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany.

References

Amiraslanov, Tahir. 2005. “Azerbaijan. A Cuisine In Harmony.” In Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Edited by Darra Goldstein, Kathrin Merkle, and Stephen Mennell, 65–74. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Aronsson, Karin, and Lucas Gottzén. 2011. “Generational Positions at a Family Dinner: Food Morality and Social Order.” Language in Society 40 (4): 405–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404511000455.Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Susanne. 2015. “Brotgetreide: Unser tägliches Brot.” Biologie in unserer Zeit 45 (3): 168–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/biuz.201510566.Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. [1979] 2010. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London, New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Brewer, John, and Roy Porter. 1997. Consumption and the World of Goods. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Brombach, Christine. 2011. “Soziale Dimensionen des Ernährungsverhaltens. Ernährungssoziologische Forschung.” Ernährungs-Umschau 6: 318–24. https://www.ernaehrungs-umschau.de/fileadmin/Ernaehrungs-Umschau/pdfs/pdf_2011/06_11/EU06_2011_318_324.qxd.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Buzilă, Varvara, and Todorina Băzgu. 2005. “Moldova. Ritual Bread through the Seasons.” In Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Edited by Darra Goldstein, Kathrin Merkle, and Stephen Mennell, 301–4. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Çabej, Eqrem. 1976. Studime gjuhësore. II, Studime etimologjike në fushë të shqipes P-ZH. [Linguistic Studies. II, Etymological Studies in the Field of Albanian P-ZH]. Pristina: Rilindja.Search in Google Scholar

Camporesi, Piero. 1989. Bread of Dreams. Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Canolli, Arsim. 2019. Flija: Vrojtim Etnografik. Pristina: Cuneus.Search in Google Scholar

Cara, Arben, and Mimoza Margjeka. 2015. “Kanun of Leke Dukagjini: Customary Law of Northern Albania.” European Scientific Journal 11 (28): 174–86. https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/6383.Search in Google Scholar

Csaplár-Degovics, Krizstián, and Lumnije Jusufi. 2020. Das ungarisch-albanische Wörterbuch von Zoltán László (1913). Imperialismus und Sprachwissenschaft. Vienna: Verlag der ÖAW.10.2307/j.ctv1zqdv8gSearch in Google Scholar

Den Hartog, Adel P. 1997. “Vegetables as Part of the Dutch Food Culture. Invention of a Tradition?” In Essen und kulturelle Identität: europäische Perspektiven. Edited by Hans J. Teuteberg, Gerhard Neumann, and Eva Barlösius, 372–86. Berlin: Akademie.Search in Google Scholar

Dornfeldt, Matthias, and Enrico Seewald. 2019. Kontinuitäten und Brüche: Albanien und die deutschen Staaten 1912–2019. Berlin et al.: Peter Lang.10.3726/b16031Search in Google Scholar

Durham, Edith. [1909] 2021. High Albania. Pristina: Artini.Search in Google Scholar

Espagne, Michel, and Michael Werner. 1985. “Deutsch-französischer Kulturtransfer im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Zu einem neuen interdisziplinären Forschungsprogramm des C.N.R.S.” Francia 13: 502–10. https://doi.org/10.11588/fr.1985.0.52120.Search in Google Scholar

Espagne, Michel. 1997a. “Die Rolle der Mittler im Kulturtransfer.” In Kulturtransfer im Epochenbruch. Frankreich – Deutschland 1770 bis 1815. Edited by Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, and Rolf Reichardt, 309–29. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag.Search in Google Scholar

Espagne, Michel. 1997b. “Minderheiten und Migration im Kulturtransfer.” Comparativ 5 (6): 247–58. https://core.ac.uk/download/480553741.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Fishta, Gjergj. [1937] 1999. Lahuta e Malcis. [The Highland Lute]. Pristina: Buzuku.Search in Google Scholar

Gashi, Skënder. 1995. “Albanisch-sächsische Berührungen in Kosova und einige ihrer onomastischen und lexikalischen Relikte.” Dardania. Zeitschrift für Geschichte, Kultur und Information 4: 87–127.Search in Google Scholar

Gashi, Skënder. 2015. Kërkime onomastike-historike për minoritete të shuara e aktuale të Kosovës. [Historical Onomastic Research on the Shrinking and the Present Minorities in Kosovo]. Pristina: Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts.Search in Google Scholar

Gjeçovi, Shtjefën. 1989. Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit. The Code of Lekë Dukagjini. Translated and introduced by Leonard Fox. New York: Gjonlekaj Pub. Co.Search in Google Scholar

Goldstein, Darra, and Kathrin Merkle, eds. 2005. Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity Diversity and Dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Gostentschnigg, Kurt. 2017. Wissenschaft im Spannungsfeld von Politik und Militär: Die österreichisch-ungarische Albanologie 1867–1918. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-658-18911-2Search in Google Scholar

Gowing, Elizabeth. 2011. Travels in Blood and Honey: Becoming a Beekeper in Kosovo. London: Interlink Signal.Search in Google Scholar

Grieshaber, Susan. 1997. “Mealtime Rituals: Power and Resistance in the Construction Of Mealtime Rules.” British Journal of Sociology 48 (4): 649–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/591601.Search in Google Scholar

Halimi-Statovci, Drita. 2014. Nga djepi në përjetësi. Pristina: IAP.Search in Google Scholar

Hamiti, Muhamet, and Hamiti, Vjosa. 2018. “The Emergence of a Nation: Writers and Fighters as Agents.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 21 (6): 619–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877917708626.Search in Google Scholar

Hamiti, Vjosa, and Arlinda Dushi. 2023. “Nahrungsmittel als Sprach- und Kulturbrücke im deutsch-albanischen Sprachkontakt in Kosovo.” Glottotheory 14 (2): 175–99. https://doi.org/10.1515/glot-2023-2010.Search in Google Scholar

Hamiti, Vjosa, and Blertë Ismajli. 2020. “Deutsche Sprache und Kultur als Träger für den lokalen und globalen Arbeitsmarkt.” In Germanistik in Mittelost- und Südosteuropa: Bildung und Ausbildung für einen polyvalenten Arbeitsmarkt (Berufssprache Deutsch in Theorie und Praxis). Edited by Teuta Abrashi, Ellen Tichy, and Doris Sava, 187–99. Berlin et al.: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Hamiti, Vjosa, and Milote Sadiku. 2018. “Die Fremdzuschreibung Jugo zwischen Neutralität und Slurs/Verunglimpfung. Eine Analyse des Ethnophaulismus Jugo in Presseberichten der deutschsprachigen Schweiz.” Zeitschrift für Balkanologie 54 (2): 170–83. https://www.zeitschrift-fuer-balkanologie.de/index.php/zfb/article/view/538.10.13173/zeitbalk.54.2.0170Search in Google Scholar

Hamiti, Vjosa, Milote Sadiku, and Sadije Rexhepi. 2018. “Me bukë e krip (e zemër të bardhë): Eine Kontrastive Analyse der Phrasiologismen mit Lebensmittelbezeichnungen im Albanischen und im Deutschen.” In Kulinarische Phraseologie: intra- und interlinguale Einblicke. Edited by Anna Gonde, and Joanna Szczęk, 95–112. Berlin: Frank & Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Hirschfelder, Gunther. 2008. “Esskultur – Zur Geschichte des Regionalen und den Chancen des Globalen.” Ernährung im Fokus 9: 368–71.Search in Google Scholar

Hirschfelder, Gunther. 2013. “Pelmeni, Pizza, Pirogge. Determinanten kultureller Identität im Kontext europäischer Küchensysteme.” In Russische Küche und kulturelle Identität. Edited by Norbert Franz, 31–50. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam.Search in Google Scholar

Imbrasienė, Birutė. 2005. “Lithuania. Rituals and Feasts.” In Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Edited by Darra Goldstein, Kathrin Merkle, and Stephen Mennell, 265–80. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Judah, Tim. 2008. Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/wentk/9780195376739.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Jusufi, Lumnije, and Milote Sadiku. 2024. “The Semiotics of Kosovo’s Streetscapes: German Signage on Vehicles as an Example of Moving Landscapes.” Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal 10 (1): 79–103. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.23003.jus.Search in Google Scholar

Jusufi, Lumnije. 2020. “Die kosovarischen ‘Schatzis’. Das Verhältnis zwischen den einheimischen und den ausgewanderten Bevölkerungsgruppen in Kosovo.” Südosteuropa-Mitteilungen 60 (4): 51–66.Search in Google Scholar

Jusufi, Lumnije. 2023. “Germanismen als albanische und mazedonische Fachwörter in Technik und Handwerk.” Schnittstelle Germanistik. Forum für Deutsche Sprache, Literatur und Kultur des mittleren und östlichen Europas 3 (1): 121–40. https://doi.org/10.33675/SGER/2023/1/9.Search in Google Scholar

Kadriu, Lumnije. 2024. “Self-Voluntary ‘Permanent’ Return Migration to Post-War Kosovo.” In Return Migration and its Consequences in Southeast Europe. Edited by Jasna Čapo, Rozita Dimova, and Lumnije Jusufi, 95–116. Berlin et al.: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Kadzadej, Brikena, and Vjosa Hamiti. 2020. “Nonverbal Communication in German–Albanian Cultural Contrast.” Sakarya University Journal of Education 10 (1): 187–201. https://doi.org/10.19126/suje.689503.Search in Google Scholar

Kalinke, Heinke M., Klaus Roth, and Thomas Weger, eds. 2010. Esskultur und kulturelle Identität. Ethnologische Nahrungsforschung im östlichen Europa. Munich: Oldenbourg.Search in Google Scholar

Krasniqi, Mark. 2005. Mikpritja në traditën shqiptare. Pristina: ASHAK.Search in Google Scholar

Langer, Benjamin. 2019. Fremde, ferne Welt. Mazedonienimaginationen in der deutschsprachigen Literatur seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: transcript.10.1515/9783839447840Search in Google Scholar

Leutloff-Grandits, Carolin. 2015. “Transnationale Ehen durch die Linse von Gender und Familie: Heiratsmigration aus Kosovos Süden in Länder der EU.” IMIS-Beitrage 47: 163–93.Search in Google Scholar

Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen. 2008. Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Interaktion, Fremdwahrnehmung und Kulturtransfer, 2nd. ed. Stuttgart: Metzler.10.1007/978-3-476-05214-8_4Search in Google Scholar

Maksuti, Izer. 2010. Sprachliche Einflüsse des Deutschen auf das Albanische. Deutsche Entlehnungen im albanischen Wortschatz. Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller.Search in Google Scholar

Maksuti, Izer. 2009. Internationalismen im Albanischen. Eine kontrastive Untersuchung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Alltagswortschatzes – Albanisch, Deutsch, Englisch, Französisch. Saarbrücken: Südwestdeutscher Verlag für Hochschulschriften.Search in Google Scholar

Maksuti, Izer. 2014. “Kontaktet gjuhësore të shqipes me gjermanishten.” Albanologjia. International Journal of Albanology 1–2: 149–54.Search in Google Scholar

Maksuti, Izer. 2015. “Mbi disa veçori leksikore të gjermanishtes dhe shqipes – sprovë për një krahasim të dy arealeve gjuhësore.” Filologjia. International Journal of Human Sciences 3: 30–47.Search in Google Scholar

Malcolm, Noel. 1999. Kosovo: A Short History, 2nd ed. London: Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Mancuso, Salvatore. 2021. The Language of Law and Food: Metaphors of Recipes and Rules. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003159599Search in Google Scholar

Matvejević, Predrag. 2020. Our Daily Bread: A Meditation on the Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bread Throughout History. London: Istros Books.Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, Simone. 2002. Mahlzeitenmuster in Deutschland. Munich: Herbert Utz.Search in Google Scholar

Munishi, Shkumbin. 2020. Projeksion i zhvillimeve sociolinguistike (rasti i dygjuhësisë shqip – serbisht në Kosovë). Pristina: ZeroPrint.Search in Google Scholar

Neumann, Gerhard. 2001. “Einleitung.” In Essen und Lebensqualität. Natur- und kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven. Edited by Gerhard Neumann, Alois Wierlacher, and Rainer Wild, 9–14. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.Search in Google Scholar

Novinšćak Kölker, Karolina. 2016. Migrationsnetzwerke zwischen Deutschland und den Herkunftsstaaten Republik Albanien und Republik Kosovo. Bonn, Eschborn: GIZ.Search in Google Scholar

Ochs, Elinor, and Merav Shohet. 2006. “The Cultural Structure of Mealtime Socialization.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 111: 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.154.Search in Google Scholar

Pasqualone, Antonella, Francesco Caponio, Carmine Summo, and Visar Arapi. 2004. “Characterisation of Traditional Albanian Breads Derived from Different Cereals.” European Food Research & Technology 219 (1): 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-004-0917-2.Search in Google Scholar

Petreski, Marjan, Blagica Petreski, Despina Tumanoska, Edlira Narazani, Fatush Kazazi, Galjina Ognjanov, Irena Jankovic, Arben Mustafa, and Tereza Kochovska. 2018. “The Size and Effects of Emigration and Remittances in the Western Balkans. A Forecasting Based on a Delphi Process.” Südosteuropa. Journal of Politics and Society 65 (4): 679–95. https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2017-0044.Search in Google Scholar

Pichler, Robert. 2010. “Migration, Architecture and the Imagination of Home(land). An Albanian-Macedonian Case Study.” In Transnational Societies, Transterritorial Politics. Migrations from the (Post-)Yugoslav Area. Edited by Ulf Brunnbauer, 213–36. Munich: Oldenbourg.Search in Google Scholar

Poghosyan Haik, Svetlana. 2005. “Armenia. Insights into Traditional Food Culture.” In Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Edited by Darra Goldstein, Kathrin Merkle, and Stephen Mennell, 36–52. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Porter, Roy. 1989. “Preface by Roy Porter.” In Bread of Dreams: Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Piero Camporesi, 1–16. Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Prahl, Hans-Werner, and Monika Setzwein. 1999. Soziologie der Ernährung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.10.1007/978-3-322-99874-3Search in Google Scholar

Riley, Kathleen C., and Amy L. Paugh. 2018. Food and Language: Discourses and Foodways across Cultures. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315695235Search in Google Scholar

Sadiku, Milote, and Blertë Ismajli. 2017. “Germanismen in der kosovarischen Mundart der albanischen Sprache.” Aussiger Beiträge 11: 189–208. https://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/frontdoor/index/index/year/2018/docId/47887.Search in Google Scholar

Sadiku, Milote, and Vjosa Hamiti. 2021. “Kopf-Phraseme im Albanischen, Bosnischen/Kroatischen/Serbischen und Mazedonischen im Vergleich.” Zeitschrift für Balkanologie 57 (1): 55–75. https://doi.org/10.13173/zeitbalk.57.1.0055.Search in Google Scholar

Sadiku, Milote. 2018. “Deutsche Lehnwörter in der albanischen Mundart in Kosovo: Eine Analyse ihrer morphologischen Anpassung.” In Deutsch in Mittel-, Ost- und Südosteuropa – DiMOS Füllhorn Nr. 3. Edited by Hannes Philipp, Andrea Ströbl, Bernadette Weber, and Johann Wellner, 215–23. Regensburg: Universitätsbibliothek Regensburg. https://epub.uni-regensburg.de/41112/1/Dimos-Band%20Regensburger%20Tagung_2016_VersionNovember19.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt-Neke, Michael. 2014. “Einführung.” In Der Kanun – das albanische Gewohnheitsrecht nach dem sogenannten Kanun des Lekë Dukagjini, kodifiziert von Shtjefën Gjeçovi. Edited by Robert Elsie, ix–xxvi. Berlin: Osteuropa Zentrum Berlin.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Oliver Jens. 2008. Kosovo. Kurze Geschichte einer zentralbalkanischen Landschaft. Vienna et al.: Böhlau.Search in Google Scholar

Szatrowski, Polly E., ed. 2014. Language and Food. Verbal and Nonverbal Experiences. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.238 10.1075/pbns.238Search in Google Scholar

Tanner, Jakob. 1997. “Italienische ‘Makkaroni-Esser’ in der Schweiz: Migration von Arbeitskräften und kulinarischen Traditionen.” In Essen und kulturelle Identität. Edited by Hans- Jürgen Teuteberg, Gerhard Neumann, and Alois Wierlacher, 473–97. Berlin: Akademie.Search in Google Scholar

Tichy, Ellen, and Blertë Ismajli. 2022. “Germanistik im Kosovo – Herausforderung Interdisziplinarität und Kompetenzorientierung.” In Interdisziplinarität, Kompetenzorientiertheit und Digitalisierung als aktuelle Tendenzen und Herausforderungen in der Germanistik. Edited by Roberta V. Rada, and Samira Lemkecher, 59–72. Berlin et al.: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Wierlacher, Alois. 2008. “Die Kulinarische Sprache.” In Kulinaristik. Forschung – Lehre – Praxis. Edited by Alois Wierlacher, and Regina Bendix, 112–26. Berlin: LIT.Search in Google Scholar

Wotjak, Gerd. 2010. “Schmeckt die Wurst auch ohne Brot? Deutsche Phraseologismen mit Lebensmittelbezeichnungen/Kulinarismen sowie (mehr oder weniger feste) Wortverbindungen zum Ausdruck von ungenügender bzw. übermäßiger Ernährung.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 111, Nr. 4 (2010): 421–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43344706.Search in Google Scholar

Zaugg, Franziska A. 2016. Albanische Muslime in der Waffen-SS. Von “Großalbanien” zur Division “Skanderbeg”. Paderborn: Schöningh.10.30965/9783657784363Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Constrained Choices: How Bosnian Communists Lost Their Party Before Losing the Elections

- Legal Regulation of Hybrid Work Models and Their Impact on Work-Life Balance: A Case Study of Ukraine

- Sustainable Development, Digital Democracy, and Open Government: Co-Creation Synergy in Ukraine

- A Transfer of Language and Culture: German Bread and Pastries and Their Names in Kosovo

- Book Review Essay

- Kosta Nikolić’s Book Krajina (1991–1995). An Extended Review

- Book Reviews

- Dunja Jelenković: Festival jugoslovenskog dokumentarnog i kratkometražnog filma, 1954–2004. Od jugoslovenskog socijalizma do srpskog nacionalizma

- Anna Di Lellio: La Jugoslavia crollò in miniera. Kosovo 1989: lo sciopero di Trepça e la lotta per l’autonomia

- Tanja Petrović: Utopia of the Uniform. Affective Afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army

- Eugen Străuțiu, Steven D. Roper, William E. Crowther, Dareg Zabarah-Chulak, Victor Juc, and Robert E. Hamilton: The Armed Conflict of the Dniester. Three Decades Later

- Robert Rydzewski: The Balkan Route – Hope, Migration and Europeanisation in Liminal Spaces

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Constrained Choices: How Bosnian Communists Lost Their Party Before Losing the Elections

- Legal Regulation of Hybrid Work Models and Their Impact on Work-Life Balance: A Case Study of Ukraine

- Sustainable Development, Digital Democracy, and Open Government: Co-Creation Synergy in Ukraine

- A Transfer of Language and Culture: German Bread and Pastries and Their Names in Kosovo

- Book Review Essay

- Kosta Nikolić’s Book Krajina (1991–1995). An Extended Review

- Book Reviews

- Dunja Jelenković: Festival jugoslovenskog dokumentarnog i kratkometražnog filma, 1954–2004. Od jugoslovenskog socijalizma do srpskog nacionalizma

- Anna Di Lellio: La Jugoslavia crollò in miniera. Kosovo 1989: lo sciopero di Trepça e la lotta per l’autonomia

- Tanja Petrović: Utopia of the Uniform. Affective Afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army

- Eugen Străuțiu, Steven D. Roper, William E. Crowther, Dareg Zabarah-Chulak, Victor Juc, and Robert E. Hamilton: The Armed Conflict of the Dniester. Three Decades Later

- Robert Rydzewski: The Balkan Route – Hope, Migration and Europeanisation in Liminal Spaces