Photographic Archives and the Anthropology of Communism in Albania

-

Gilles de Rapper

Gilles de Rapper is an anthropologist and CNRS researcher, currently Director of Modern and Contemporary Studies at the École française d’Athènes. Since 1994, he has conducted numerous fieldworks in Albania and the Balkans. His work has focused on the coexistence of Christians and Muslims in southern Albania, on cross-border relations between Greece and Albania and on the effects of Albanian migration to Greece. More recently, he has been interested in the trajectory of photographs produced during the socialist period in Albania and in their role in the current perception of the socialist past.

Abstract

The communist period in Albania was a time of intense photographic production. Much more than in previous periods, photography was perceived by those in power as an indispensable tool while at the same time becoming accessible to almost the entire population. Many photographs from the time survived the end of the communist regime and can now be used to study the history and memory of that period. To be of historical value, however, the diversity of photographic genres and practices, as well as the history of the constitution of photographic archives demands consideration of the context of the production and circulation of photographs, and that is a primary objective of this article. The author shows how he conducted an ethnography of photography based on presentation of the current state of public and private collections, and how such investigation constitutes a contribution to the anthropology of communism in Albania.

In recent years the communist period has become a research subject for historians and anthropologists interested in Albania. Recent studies have made it possible to move away from the passionate discourse that still marks the public perception of the period so as to highlight the complexity of both the history of the communist experience in Albania and of its modes of perception since the fall in 1991 of the regime established by Enver Hoxha at the end of the Second World War.[1] Some of these works are based on the exploitation of the numerous archives left by institutions as well as the also considerable printed production from the time in books and newspapers. Others use oral history from the many people still alive who experienced the period.[2] The visual production of communist Albania has received comparatively limited attention, although work has been done on film and photography.[3] As one of the first to study the period’s photographic production I should like to focus in this article on the condition of the photographic archives and their uses in Albania today, for which two points seem important to me. Visual history and anthropology now fully recognise that the materiality of photographs is as important as their iconic value, for photographs are objects as well as images, and their material nature determines not only how they are produced, used, transmitted and viewed, but how they are preserved (Edwards and Hart 2004). On the other hand, the value of a photograph for the historian or anthropologist lies not only in what it reflects as an image and as an object, of the moment of its production, but in its whole trajectory, which must be known and considered as far as that is possible. There is no doubt that the current state of the photographic archives is the product of a history to be retraced (About and Chéroux 2001).

In the first part of this article I shall describe the conditions of production of photographs during the communist period in Albania (1944–1991) by reviewing the main producing institutions as well as the destinations of the images, through which I intend to show the main directions of a history of photography in communist Albania. The article’s second part will be devoted to what I have called “the postcommunist moment” of photography, in which I shall reveal what has become of the images produced during the communist period and ask how they can constitute sources for the historian or the anthropologist. Finally, relying on my own research, I shall return to the inflection the study of photography can give to our perception and knowledge of the communist period.

Photographic Production in Communist Albania

A history of photography during the communist period in Albania remains to be written. Attempts in this direction were made in the 1970s, in the context of the rediscovery of early Albanian photography from the end of the nineteenth century until the Second World War, the precommunist period still sometimes called “the golden age” (Chauvin and Raby 2011, 3) that receives much more attention than the years following. The communist period is generally less appreciated by historians of photography, who consider the material from that period to be of lesser quality and of minor interest because of its subjection to ideology and political imperatives.[4]

There is no doubt, however, that the communist period is important to the history of photography in Albania, both because of its instrumentalisation by the state, which provided photographers with unparalleled resources and a new status; and its unprecedented diffusion among the general population. A picture of the period’s photography—its institutions, producers, genres and diffusion—is important for understanding the constitution and current state of photographic archives and allows reflection on the possibility of using photography as a source for the history of both communist and postcommunist Albania.[5]

The history of photography in communist Albania can be characterized by a double movement, that of the state growing’s control of the profession and of photographers’ output on the one hand, and on the other hand that of the diffusion and appropriation of the uses of photography among the population as a whole. I propose to call the first the “state moment” of photography and the second the “popular moment,” and together those two make the Albanian case particularly interesting—and challenging. There seems to be some tension between the state’s use of photography in what is commonly considered as one of the harshest and most isolated communist regimes in the world within which surveillance and propaganda played a major role, and the social use of photography which was supported but strictly controlled by the authorities.

The State Moment of Photography

As early as the interwar period, King Zog (r. 1928–1939) seems to have used professional photographers to disseminate images of his status as ruler and his political action. The king’s wedding and the celebration of the first ten years of his reign, in 1938, were occasions for the production of numerous official photographs that were distributed by the press. The album L’Albanie illustrée, published in 1928, can also be seen as the use of a visual propaganda medium (Selenica 1928). As a complement to a book based on official documents and presenting the state of Albania in 1927 in terms of population, economy and political situation, L’Albanie illustrée offers 400 pages of photographs of landscapes, economic activities and prominent figures of the state, most taken for the specific purpose of propaganda. A number of photographers, like Ymer Bali (1894–1967) who took most of the album’s pictures, are known to have placed themselves at the service of the state. During the Second World War, photography was used by communist party supporters for propaganda purposes, such as Mandi Koçi (1912–1986) who is cited as the photographer of the First Brigade of the National Liberation Army from 1943 onwards.[6]

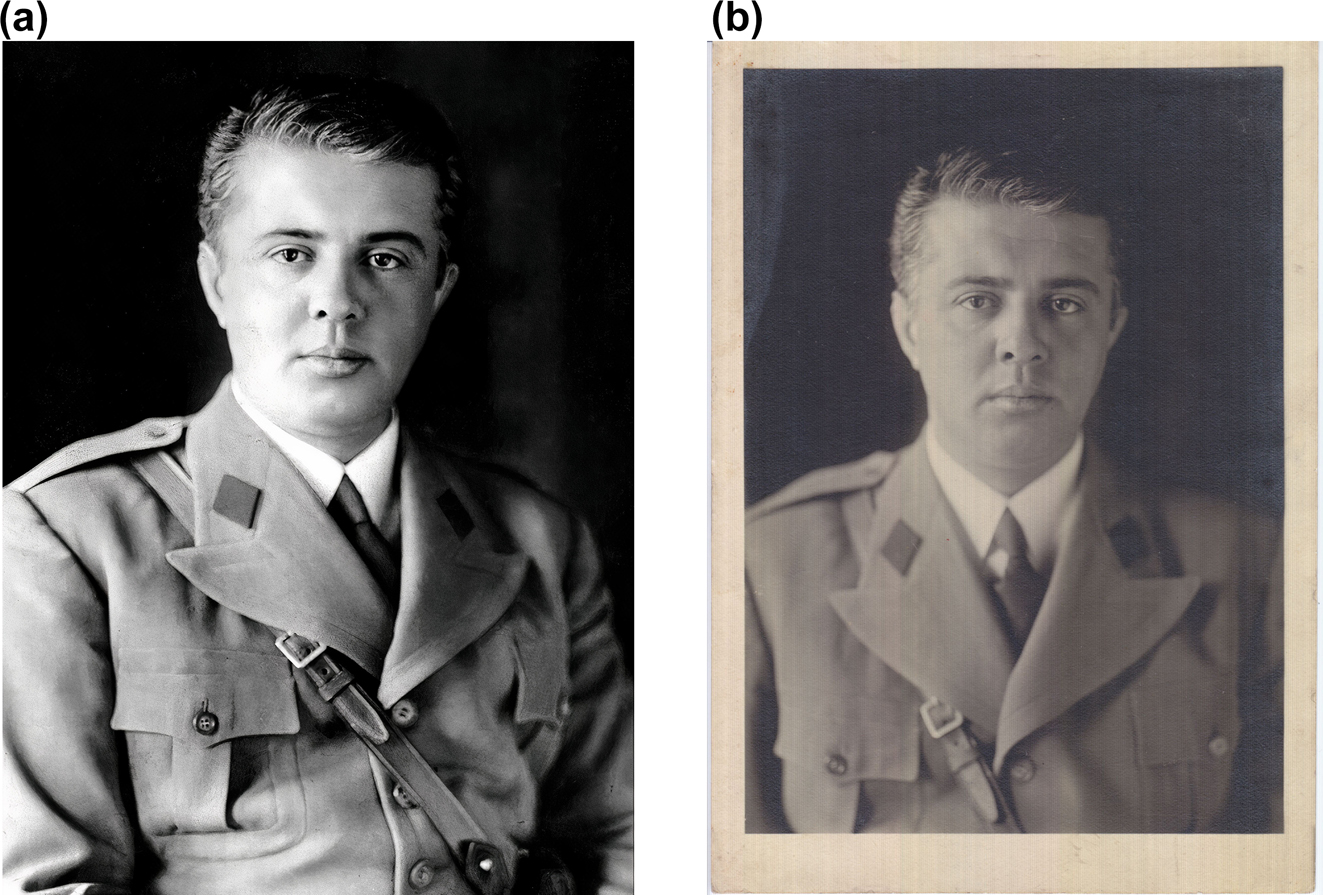

However, those few attempts were as nothing compared to what the communists did after they assumed power at the end of 1944, which resulted in almost complete control over all photographic production and usage. In December 1944 the first official portrait photographs was taken of Enver Hoxha as the leader of the new political regime. The pictures were taken by two private photographers who had been close to the court of King Zog, Vasil (1908–1989) and Jani (1913–2005) Ristani (Figure 1a and b).

Two portraits of Enver Hoxha, December 1944. Sources: (a) Enver Hoxha, Jeta dhe vepra, Tirana, 1986, 87; (b) Courtesy: private collection, Tirana. The photo on the left was used as an official portrait during the early years of communist rule and was widely circulated after Hoxha’s death in 1985. My research has shown that it was only one of nine poses taken at the same sitting and clarified the conditions under which the portrait was taken. The other poses, such as the one on the right, were never circulated (Interview, Tirana, October 2010).

The Albanian Telegraphic Agency (Agjencia telegrafike shqiptare, ATSH), heir to the press agency of the previous period, acquired a photographic laboratory only in 1947.[7] From 1948 onwards photographers’ activity, like that of the rest of the economy as a whole, was subjected to collectivization and state control. Like other craftsmen, private photographers were encouraged to join either the collective workshops, the first of which appeared as early as 1947, or the state institutions that were being established. The following section will deal more fully with collective workshops as instruments of dissemination of photography throughout Albania, so I shall review here only briefly the main institutions that employed photographers throughout the communist period and thus created photographic genres and photographic archives, some of which have survived to the present day. A review of photography is as necessary as source criticism for visual material as it is with written material.

In the early postwar years the Telegraphic Agency became a central photographic institution, its photographers responsible for documenting the country’s political, cultural and sporting events and for reporting changes in the economy, education and lifestyle (Figure 2).

The head of the ATSH photo lab, Petrit Kumi, with his collaborators. Tirana, late 1980s. Courtesy: private collection, Tirana. This image is an example of a common practice from the 1960s onwards: the self-staging of photographers’ work for self-promotion.

The Agency supplied photographs to the press and state institutions, whether or not those institutions employed their own photographers. The ATSH gradually built up a photographic archive covering all areas, a monopoly strengthened in the 1980s when, for reasons both financial and of ideological control, many photographic laboratories in ministries, the press and museums were closed. Most institutional photographers were now obliged to have their work developed and printed at the ATSH laboratory, which kept prints and negatives of a large number of photographs.

Press titles multiplied in the second half of the 1940s, both locally and nationally, and various of such newspapers and magazines published photographs, as had been the case before the Second World War. However, it was not until the 1960s that the technical means to print quality photographs became available and most newspapers were equipped with a “photo-journalist” (Alb. fotoreporter) and a photographic laboratory (Figure 3). Such illustrated periodicals were a means for the authorities to disseminate desired images of their political action and to spread imagery supporting their modernization project. Distributed throughout the country and publicly displayed and read, they also helped familiarise the population with photography.

Roland Tasho, photographer of Ylli magazine in Tirana, 1988. Courtesy: private collection, Tirana. Throughout the communist period the motorcycle was an emblematic attribute of the photojournalist’s profession. At a time when private means of transport were scarce and movement across the country was limited and controlled, the motorcycle represented both relative freedom of movement and, like the camera, technological modernity that distinguished its user.

The army was another producer of photographs and provided subjects for many photographers employed by the armed forces or in other institutions. The army had a well-equipped central photographic laboratory in Tirana, where its photographers recorded the activities of the general staff, photographing official ceremonies and parades, visits by delegations, manoeuvres across the country, or the reception or deployment of new armaments (Figure 4). Another Tirana laboratory was at the disposal of the two photo-journalists working for the army periodicals, the newspaper Luftëtari and the magazine 10 Korriku, the latter publishing many colour photographs.[8] Each military region had its own Propaganda Sector equipped with photographic material and, in each garrison town, the Officers’ House (Alb. Shtëpia e oficerëve) employed a photographer who documented the activities of local units and took portraits of soldiers (Figure 5). Petrit Ristani, former head of the army’s central laboratory (1975–1992), reports that he supervised 43 laboratories across the country (Interview, Tirana, October 2010). This broad presence of photography in an institution that occupied a fundamental place both politically and territorially—even in the very existence of the population—had a major effect on the dissemination of photography and the training of photographers in general. Many photographers received their initiation in photography or specialised in it during their military service under the supervision of military photographers.

Army photographers posing on the occasion of a photographic exhibition, Tirana. Courtesy: Private collection, Tirana. Photographic exhibitions were an important means of disseminating photography, as was the illustrated press. The ambition of every photographer was to have the chance to mount a “personal exhibition”. Whether reflecting the activity of a whole department or a single individual, exhibitions were a source of pride and gave rise to rituals, such as posing in front of the exhibited prints.

Officers and men of a unit stationed in central Albania, 1970s. Courtesy: Private collection, Përrenjas. Notable here is the absence of insignia distinguishing officers from ordinary soldiers, characteristic of the period following the Cultural Revolution of 1967.

The university founded in 1957 and later the Academy of Sciences founded in 1972 produced scientific photographs for all the physical sciences, zoology and botany, geography and geology, archaeology, and ethnography. Institutes specializing in architecture and urban planning or in the conservation of cultural monuments also had their own photographic services. In all cases, the photographers’ task was to produce scientific images and document the activities of the institutions that employed them.

Finally there were the ministries, the Central Committee of the Labour Party, and the main museums, all of which had photographic services. This brief enumeration is not intended to be exhaustive but to show the variety and sheer quantity of photographic genres. Contrary to what might be suggested by the association of communism with an economy of scarcity, or Albania’s marginal position in the economy of photographic production (Albania produces no photographic material nor equipment), photography was not scarce, for from the very beginning it was seen as a tool of government. For example, the first trade agreement with the USSR, in 1945, provided for the delivery of photographic material (Fishta and Ziu 2004, 256) and the Albanian authorities devoted very considerable means to the provision of abundant material of good quality to the photographers of the institutions. The diplomatic and economic isolation of Albania never prevented it from importing expensive cameras, including from Western countries, nor the circulation of foreign literature on photography. Albanian photographers were even sent abroad for training (Figure 6).

A delegation of Albanian photographers receives honours in China, in 1970. Courtesy: Private collection, Tirana. From left to right: Katjusha Kumi, Pleurat Sulo, Jani Ristani, and Refik Veseli spent several months in China where they were trained in various photographic techniques. They also visited the country and were offered cameras for their personal use as tourists.

It should be emphasized that state production of photography served a variety of purposes only imperfectly covered by the category “propaganda” so readily associated with photography in communist countries. Not all images were intended to be circulated or distributed to the same audiences, some being essentially informative or documentary in nature, while others were staged to convey a specific message. Some were intended for wider publication while others were firmly restricted, such as private photographs of Enver Hoxha and his family which were processed by a special photographic and archive service (de Rapper 2016a). Photographers could take pictures in different genres, perhaps taking advantage of accompanying an official delegation to a scenic region to take landscape photographs, for example. The official and generally political nature of photography that characterizes the state moment should not mask the diversity of modes of production, circulation and reception of those images. The limitations imposed on the production and use of photographs, a major feature of the conditions of the time, did not exclude a variety of genres and uses.

In any case, the category of “propaganda photography”, as it tends to be used to qualify the photographic production of the communist world, seems to be doubly restrictive, for it erases the diversity of practices and uses of photography, while tending simultaneously to isolate communist practices from other practices, previous or contemporary, that existed in the Western world or elsewhere.[9] Further research would undoubtedly show the influence on Albanian photography on photographic uses that were established in the interwar period and later both in authoritarian and democratic states. Both press and family photography, for instance, would reveal the existence of shared models beyond the communist world.

The Popular Moment of Photography

The communist period was also a time of great popularisation if not of the practice then at least of the uses of photography. Here again, the break with the previous period was not immediate, for until the 1950s photography remained an urban practice and was more widespread among the cultivated classes than among others. However, during that decade the Albanian state set up a “public service photography” organization (Alb. fotografia e shërbimit publik) that extended photographic possibilities to rural areas. Its full effect was not felt until the 1960s but by the 1980s it was common enough experience for an Albanian to be photographed. “Photography”, says an informant from Gjirokastër about this decade, “was a companion of our whole life” (fotografia ishte bashkudhëtare e jetës tonë) (Interview, Gjirokastër April 2010). For that reason professional photographers had been encouraged as early as 1947 to join cooperative workshops so that they could pool their equipment and offer their services to the general public at a lower cost than could private photographers (Figure 7). In fact from the 1960s private photographers gradually disappeared as the cooperatives were transformed into state-owned enterprises. Public studios and a peripatetic photography service were opened in every city, their employees visiting surrounding villages on fixed dates or by appointment to local institutions like schools, agricultural cooperatives, and museums, or even to individual order (de Rapper and Durand 2017a).

Photographers and employees of the Tirana craftsmen’s cooperative, 1954. Courtesy: Private collection, Tirana. The cooperative gathered tailors, shoemakers, hairdressers, launderers and photographers. This picture was taken on the occasion of a course given by the head of the photo studio, Vasil Ristani (standing, third from left) at the premises of Sami Frashëri school, Tirana.

Above all, popular photography generally meant wedding photography, as it had in the previous period. Consisting at least of a photograph of the bride and groom taken before or after the wedding, the wedding photograph became the norm and few families do not possess them. Photographs of family groups taken during weddings with or without the bride and groom were usually printed in multiple copies and distributed to guests and relatives; the new society, however, created new opportunities to be photographed.

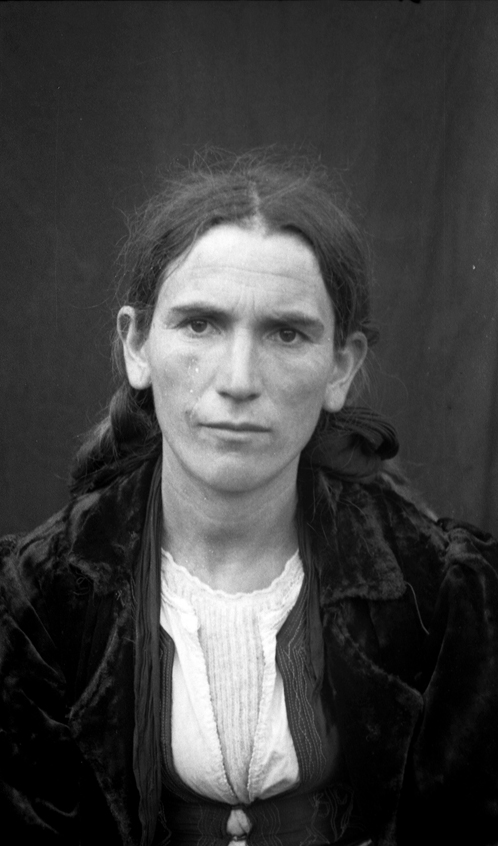

The first photographs imposed on the entire population were for identity cards, when as early as in 1948 the state enlisted photographers to go from village to village and systematically photograph all the inhabitants over the age of 16 (Figure 8).

Identity photograph taken by Filip Vito in Fushëbardhë, 1948. Courtesy: Private collection, Paris. One of 35 portraits on a film kept by the photographer’s family. The picture was taken outdoors, against a backdrop fixed to a wall. The subject was asked to remove her scarf (which can be seen at the back of her head) and is seen wearing a coat that appears in other pictures of the same series.

At that time, for many of the inhabitants of the villages this was their first time in front of a camera, and similar actions were repeated until the 1980s, each time documents had to be renewed. Such photographs were needed for many other administrative purposes such as school and university diplomas, and their use remained common throughout the communist period. In the early decades the negatives were kept by the photographers or their employers, but prints can be found in family collections, and not only on identity documents but also on tombs, with the practice of gravestone photography becoming widespread from the 1960s onwards when public studios offered a porcelain photography service (Figure 9). As has been observed in other contexts, the state origin and constrained nature of the identity photograph does not prevent its appropriation for more personal use (Peffer 2012) so that images originally intended to control and limit movement are turned, often through enhancement and colourisation for instance, into commemorative objects. The medium or material support of the image is therefore highly important for its reception.

Gravestone in Fushëbardhë. Courtesy: Gilles de Rapper, 2010. The portrait in Figure 8, here printed on porcelain, is recognisable. We learn that this woman was 26 years old at the time the photograph was taken and, presumably, that no other portrait of her was made before her death in 1958.

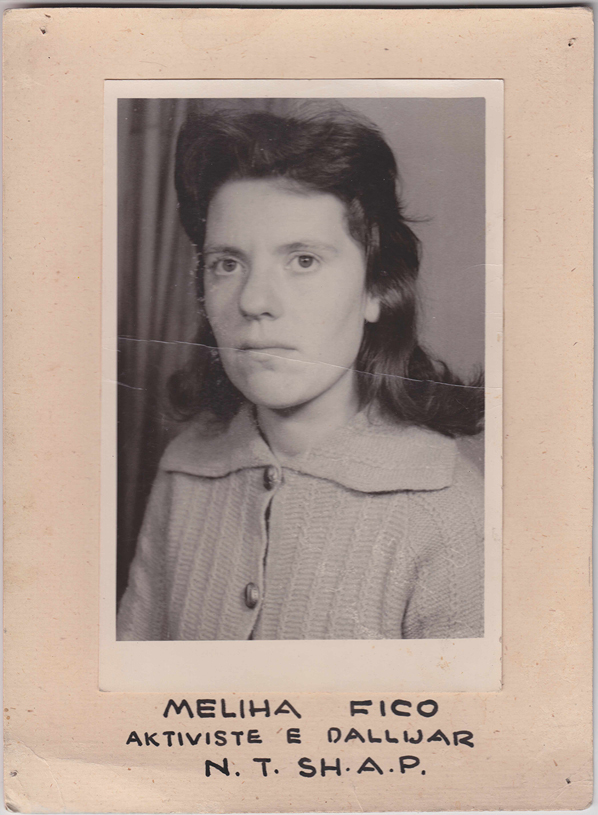

In workplaces, schools, and barracks the so-called “emulation photography” (Alb. fotografia e emulacionit) regularly distinguished the best workers, the best pupils and the best soldiers. In a Soviet-inspired practice of socialist emulation that continued until the 1980s, suitably inspiring photographic portraits were publicly displayed, in factories and schools for example, but also in town and village squares on panels known as “emulation corners” (Alb. këndi i emulacionit). According to former public service photographers, such portraits represented an important part of their work and therefore their income, because the panels were regularly renewed and new photographs were always needed (Figure 10).

Distinguished young worker from a state enterprise, Gjirokastër, 1970s. Courtesy: Private collection, Gjirokastër. Glued to a piece of cardboard with visible holes from hanging, this image bears the traces of its public use, probably on the company’s emulation board. Smiling in emulation photographs was generally forbidden.

Military service, a fundamental institution in men’s lives, was also an opportunity for photographic practice. Lasting from one to three years, depending on the period, service was a time of rupture in family life and was recorded as such. It was customary for conscripts to have their photographs taken before their incorporation—but generally after the haircut—either alone or with relatives or friends. Conscripts might also send pictures to family and friends from far-away postings, perhaps when they went out on the town or when a photographer came to the barracks (Figure 11).

Studio portrait sent by a conscript to his family, 1971. Courtesy: Private collection, Bilisht. The picture has been colourised by the photographer or, most probably, by another employee of the public studio. The text on the right gives the name of the studio and its location, in the city of Krujë, and reads: “Souvenir from the year 1971”.

After the break from the Soviet Union in 1961, periods of military training were introduced for both men and women, designed to turn the whole population into “citizen soldiers” (Alb. populli ushtar). Called zbor, they were imposed on senior school pupils every year and to varying degrees on the entire adult population, depending on the time and place. Here again, these unusual events were attended by photographers either from the military institution in charge of training or from the public service, and souvenir photographs were taken of participants, prints of which were included in family collections (Figure 12).

Young women during military training, early 1970s. Courtesy: Private collection, Bilisht. The spectacle of young women in military dress was the subject of numerous photographic representations, for private use as here, but also in the press. The same motif serves both a memorial function at the individual level and an ideological function at the level of the official discourse on the dedication of the entire population to the defence of the fatherland, as well as on female emancipation.

Finally, the relatively busy festive calendar was followed by the public service photographers who went to all the ceremonies, commemorations and community celebrations. The May Day picnic in particular inspired very many photographs, taken in public by professional photographers, which too ended up in private family collections (Figure 13).

Family picnic on May Day, Korçë, 1970s. Courtesy: Private collection, Korçë. Many of the photographic representations of the family imply a wider social framework in which both conformity and, as here, a certain hierarchy are staged: the attitude of the guests, their clothing and accessories (watches, jewellery) are indicative of their membership of the local political elite.

All these occasions produced images that were intended to be both circulated and preserved. They also served a social function, maintaining a feeling of relatedness and solidarity between members of the family and exhibiting their conformity to norms of family behaviour.[10] Whatever their origin and destination, however, such pictures should not be opposed to those produced by institutional photographers as being more “authentic” than “propaganda” photographs: their circulation in the private sphere and the appropriations that make them emotional media do not prevent them from being part of the same continuum of photographic production that tended to authorise only those prints that conformed to the image that the state wished to reinforce of the new society and the New Man. For instance, contrary to a widespread idea in Albania today, private amateur photography was not forbidden, although there was very little of it and what there was did not escape the control of the authorities—nor the self-censorship of amateur photographers, who depended on public studios for development and printing of their photographs. Knowing the public photography laboratories were watched, amateur photographers naturally enough felt themselves under surveillance too. Possession of a camera exposed them to mistrust and suspicion: would they take forbidden images? Would they sell their services illegally, to the detriment of the public studios? So it was then that even if amateur practice offered more room for manoeuvre than recourse to public service photographers for family images or artistic or technical experimentation, even amateur efforts remained part of the state organisation of photographic production (de Rapper and Durand 2017b). Although some photographers mentioned attempts at nude photography or satirical pictures, at the end of the communist period, no “forbidden” amateur photographs emerged showing anything other than what would have appeared in authorized photographs. In that regard the rise of popular photography appears not to have left a direct source documenting the daily lives of Albanians during communism, nor does it testify to the existence of counter-images challenging the official ones, suggesting that Albania might have been different from other socialist states.

The quantity of photographic production, however, as well as the significance given to it by individuals and institutions, fully justifies its consideration by historians of the communist period. Through its diversity, through the diversity of its producers and consumers, it provides access to many areas of society while making it possible to follow two fundamental characteristics of the period, those being the hold of state institutions over Albanian territory and society, and that individuals seemed reluctant to subvert that enterprise. It remains to be seen what remains, thirty years after the end of communism, of Albanian photography. In the second part of this article therefore I shall look at how certain of the photographs produced before 1991 found their way into archives, while others have disappeared.

Postcommunist Albania and Photography

In fact, state organisation of photographic production in Albania was transformed before the end of communist rule there. First of all it was weakened by the multiplication of illegal practices, especially after Enver Hoxha’s death in 1985. Professional photographers seem always to have used their equipment to offer their services privately, especially at weddings, and although still illegal and severely punishable, such activity increased in the second half of the 1980s.

In 1990 a new system was imposed on the public photographic service, something close to self-management under which photographers acquired a degree of financial autonomy. The end of the communist regime in 1991 then marked an even more radical hiatus in the activities of many professional photographers. The public studios were dismantled; premises and equipment were shared among the employees, some of whom also took over their studios’ photographic archives. Many institutional photographers left their jobs, either because their employers could no longer afford to pay them or because they felt they could earn more money and recognition as self-employed operators. It must also be said that while the need for official propaganda photography declined drastically and with it the state resources that had supported the profession, the requirements of the general population increased greatly. The 1990s saw a boom in colour photography, until then generally inaccessible, and in identity photography. Moreover, with the opening of borders and the possibilities of migration, there was an explosion in the demand for photographs for passports, visas and other certificates. D. M. for example tells us that in 1995 when he bought and equipped the first photographic studio in the town of Gjirokastër, close to the border with Greece, he could hardly cope with demand. “We would start the lab at six in the morning”, he says, “and only turn it off at ten at night” (Interview, Gjirokastër November 2009). By that time the public service had been dismantled and none of the former professional photographers had seen this explosion in demand coming.

In these conditions the durability of photographic collections was often threatened. The departure of the photographer or his reversion to private work was accompanied in a number of cases by lack of interest in previous production, much of which was simply ignored or abandoned or even destroyed. The former photographer of the officers’ house in a small town in southeastern Albania recounts that when renovation work on the building was undertaken in the 1990s after years of neglect, a truck was filled with all that was left inside and “everything was thrown in the river” (Bilisht, November 2009). The ATSH also seems to have suffered from the disorganisation of the 1990s and the subsequent closure of its photographic laboratory in 2006.

Nevertheless, many photographic collections have survived to this day, even if their degree of accessibility and valorisation is very variable. Moreover, the images themselves are not the only traces left by photographic practice, for written and oral testimonies are also useful. The following is an inventory that although admittedly incomplete still manages to indicate the main archival collections and sources available to the historian of photography in the communist period.

Institutional Archives

Although to do so accepts its reifying and simplifying nature, a distinction can be made between institutional and private archives. The former are in principle accessible to the public and benefit from cataloguing and indexing; access to the latter, on the other hand, depends on personal contacts and trust established between collection-holder and researcher. In both cases, I must acknowledge that I can present only part of a picture that can be completed only by further research. Centrally, the ATSH, which still exists, holds important photographic archives of the work of the institution’s photographers covering political activities, cultural and sporting events and the economic sphere.

In 1970, Gegë Marubi, from the third generation of a line of photographers from the town of Shkodër, effectively founded the Marubi photographic library (Fototeka Marubi) by donating the entire archive of the Marubi studio to the state (Figure 14). Marubi’s gesture inspired other photographers who were in charge of old collections, all of whom were invited to deposit their photographic archives with the newly created public archives. The creation of the photographic library marks the interest, new at the time, in photography dating from before the communist period and in particular in the origins of photography in Albania. It has awakened awareness of ancient photography among photographers and others, as shown for example by the publication in 1982 of an album devoted to the history of Albania up to the Second World War, as seen through photography (Ulqini 1982). The Marubi photographic library survived the communist period, sometimes under difficult conditions, but the creation in 2016 of the Shkodër Museum of Photography, which includes the Marubi library, opened new perspectives. By vocation the Marubi library preserves photographs from mainly the precommunist period, but its holdings nevertheless extend to the 1960s. As many as 50,000 photographs are available online (Online Archive. n.d. Marubi National Museum of Photography).

Gegë Marubi receiving a group of photographers shortly after the foundation of the Marubi Photo Library, Shkodër, early 1970s. Courtesy: Private collection, Tirana. The reasons for the donation of 200,000 photographs and whether it was voluntary or forced are still unclear but the preservation of the Marubi collection has helped maintain the fame of this line of photographers whose origins date back to the late 1850s.

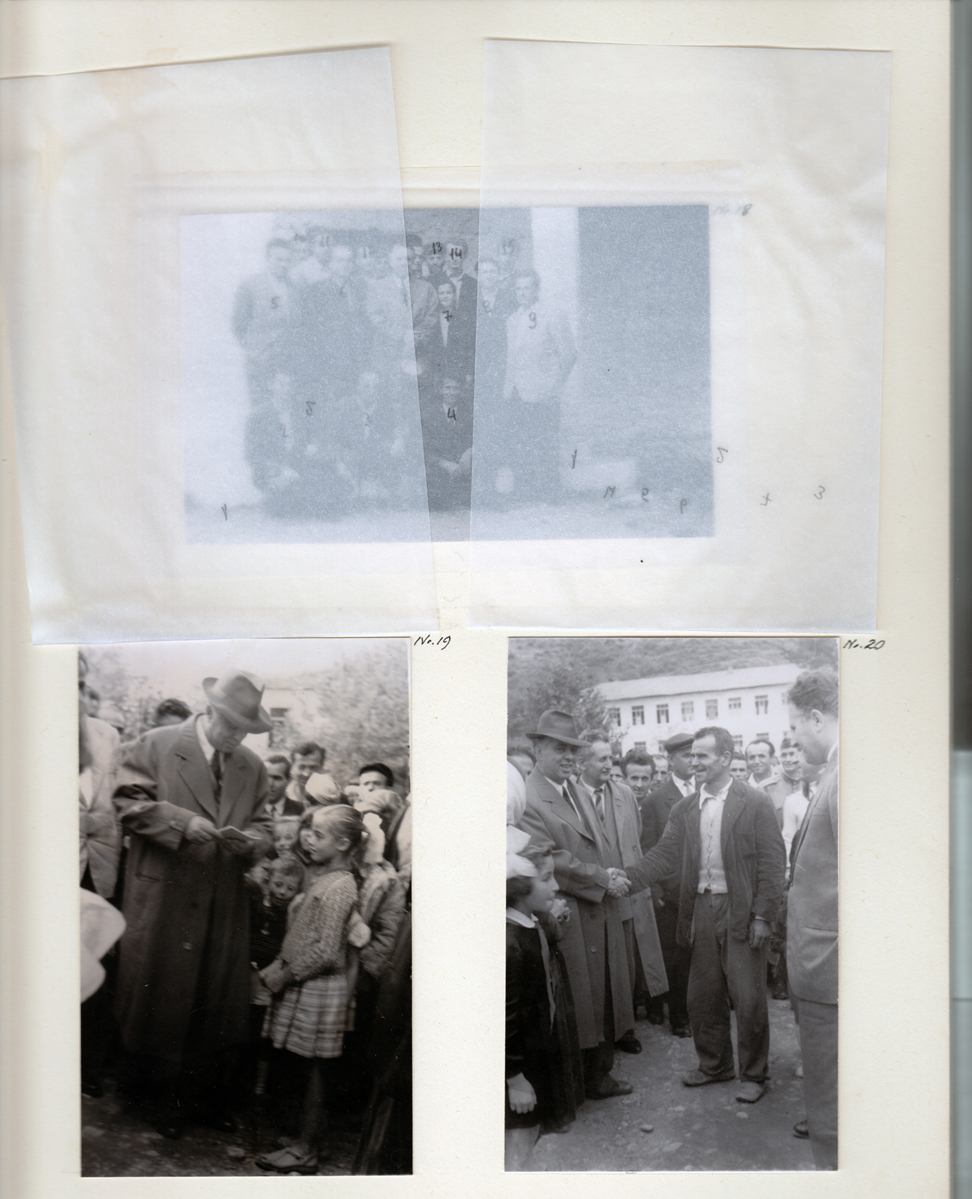

The photographic library of the national archives, the General Directorate of Archives (Drejtoria e Përgjithshme e Arkivave), is primarily concerned with the period before 1944 and contains around 135,000 photographs (Fototeka Online. n.d. Drejtoria e Përgjithshme e Arkivave). The national archives do, however, hold a series of albums from the Central Committee of the Labour Party, the committee’s archives having been transferred to the national archives in 1992. Those albums, produced from the 1950s onwards from a selection of photographs taken by ATSH or other photographers, reflect the annual activities of Central Committee members—the years 1960 and 1961, for example, are covered by ten albums and a special series is devoted to Enver Hoxha, as first secretary of the Central Committee. Each album is accompanied by a register indicating the date and subject of the photograph, a reference to the negative, its origin (ATSH, foreign press agencies, etc.) and its current location. This is followed by a description of the photograph, giving names of persons depicted. In the photographic albums an interleaved sheet of tracing paper allows each individual to be identified by a number (Figure 15). It should be noted that in addition to the photographs themselves the national archives contain a number of collections that make it possible to reconstruct the history of the photographic profession and production, such as the ministries in charge of the craft cooperatives and the service and repair companies that employed public service photographers; sources which to my knowledge have not yet been used by historians.

Page from a photograph album of the Central Committee, 1960, General Directorate of Archives, Tirana. Courtesy: Gilles de Rapper, 2009. The three images show Enver Hoxha, first secretary of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour, visiting the Shkodër district in May 1960. Hoxha’s public activities were recorded in albums separate from those of the other members of the Central Committee. The production of these albums by the staff of the Central Party Archives’ photo library began in 1969 and the one from which these three images are taken dates from 1973.

Although most ministries and institutions of the communist period kept photographic archives, they do not cover the entire period nor all the activities of the individual institutions. Petrit Ristani recounts that at the time of the great purge in the army and the Ministry of Defence in 1973–1974, the management of the Central House of the army proceeded to purge the photographic archives too: “We destroyed all the photos in which the putschists appeared. Otherwise, we would have been asked: why did you keep this? It was better to clean up than to keep the devil inside (më mirë bosh sesa shejtani brenda). There was damage, we destroyed our history, we burnt everything.”[11] Nevertheless, research centres such as the Institute of Archaeology or the Institute of Popular Culture (now the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Art Studies), the Institute of Monuments of Culture and others have very rich photographic collections the history and exploitation of which await proper attention.

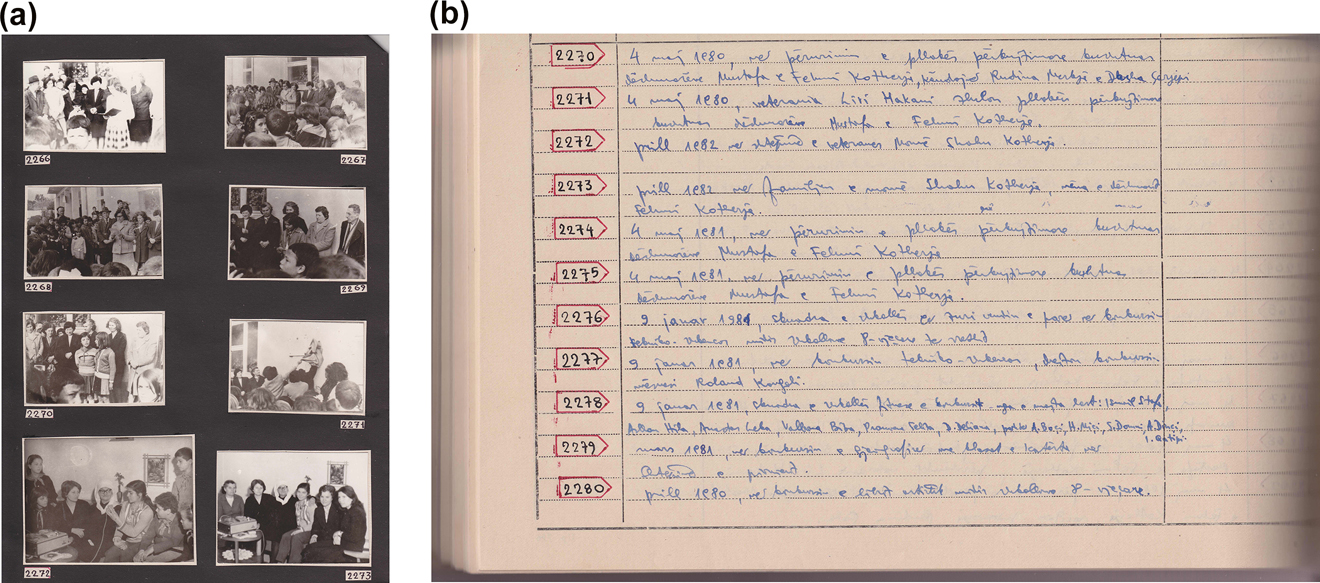

Outside the central institutions the position of the photographic collections created during the communist period is much more precarious, although certain initiatives have made it possible to safeguard or enhance particular collections. In Gjirokastër, the former photographer of the town’s theatre tells that when he retired in the early 1990s he decided to take all his archives to the Regional Archives because he was certain that no one would look after them when he left the theatre (Interview, Gjirokastër, November 2009). As another example I should mention the important photographic archive of the Naim Frashëri School in Elbasan established in 1977 which contains more than 7000 photographs tracing the history of the school from 1922. There are the usual photographs of classes, teachers and school activities, but also images collected from families in the 1980s to document the trajectories of some of the school’s pupils or teachers (Figure 16a and b). In the 2010s the museum received support from a foreign foundation to systematise and preserve the photographs, all of which are now classified and catalogued. While to my knowledge such examples are currently exceptions rather than the rule, it is certain that other collections are waiting to be rediscovered and exploited.

From the photo library of Naim Frashëri School’s museum, Elbasan. Courtesy: Gilles de Rapper, 2013. (a) Eight photographs showing the involvement of the school’s pupils in the commemorations of the “martyrs” and “veterans” of the Second World War: commemorations, collection of testimonies (using a tape recorder). The two lower photographs are from 1982, the others from 1980. These activities usually took place around 5 May, Martyrs’ Day. (b) The register gives the date and subject of each photograph.

Private Archives

These are first of all photographers’ own private archives of their work for state institutions or the public photography service. Despite the injunction to photographers in the 1970s to deposit their archives with the Marubi photo library and despite the process of centralization in the 1980s, many of them in fact kept all or part of their own production. The dismantling of state organisation of photography in the early 1990s was also an opportunity for photographers to recover part of their production or that of the institution for which they had worked. When accessible, such collections are very valuable because they provide an image of a photographer’s individual production, with its evolutions, constraints and experiments. Some of the collections have been promoted in the form of exhibitions or publications since the 1990s and more recently, for example in the work of Petrit Kumi (born 1930), a renowned photographer who was head of photography at Ylli magazine from 1964 to 1985 and then head of the ATSH laboratory until 1990. He has himself classified his own archive which he estimates at 400,000 images, and has promoted them in exhibitions and, more recently, an album containing 325 photographs (Kumi 2013). Safet and Gjylzade Dokle were employed by the city of Kukës studio between 1955 and 1983, and their archive was actively preserved in the 2000s, followed by a number of exhibitions and the publication of an album reproducing 1100 of its 22,000 images (Dokle 2014).[12]

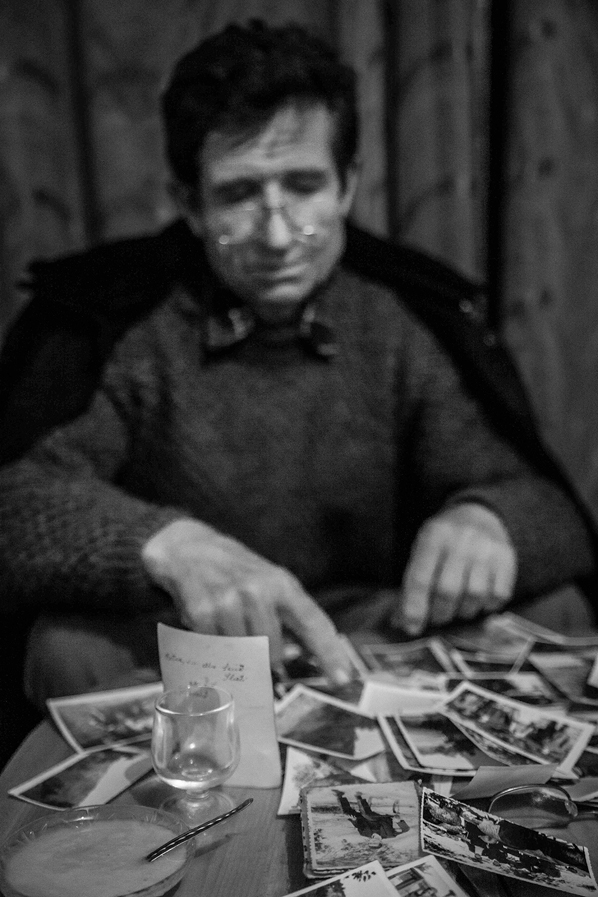

Given the wide distribution and popular enthusiasm for photography mentioned above, a very large number of family photographs too have been kept privately. The number retained depends on a variety of factors both during communism and today, in particular individuals’ positions in the system, their levels of education and geographical locations. However, it seems that everyone owned and kept photographs, due to the same state organization photography that both generated supply and provided the means of dissemination. One might think that the intimate nature of these collections—in the sense of their use rather than referring to the images themselves, which were often taken in the public space—was what preserved them from the destruction or abandonment to which some institutional collections were exposed in the early 1990s. However, that same intimate nature might just as well have been the reason for destruction or mutilation of photographs in the event of a break in family history such as divorce, criminal conviction, or migration. Nevertheless, accessible family collections provide indispensable material for understanding the role of photography in the intrusion of state institutions into private life. The number of photographs taken during state organised activities, such as the above-mentioned periods of voluntary work or military training, testifies to how those activities shaped the image of family life. The writer Ylli Demneri expresses this photographic condition: “We posed in front of the ‘state’ photographers, in the studio or in the public garden behind the statue of Skanderbeg. So, in the settings chosen by the state. […] Daily, intimate life, apart from posing in the chosen settings, remained only in people’s memories” (Demneri 2011, 9–10). Indeed, one must be careful not to reduce these collections to the category of “family photographs” as generally understood in Western societies, and even less to that of “family albums”. The latter, as objects and as a way of telling a family story, while not quite absent, probably contain only a small proportion of the photographs kept within families, and in any case their cost and rarity limited them to certain categories of the population. In most cases, photographs were kept more or less loose in boxes, envelopes, or even plastic bags (Figure 17).

Looking at family photographs, Valësh. Courtesy: Florian Bachmeier, 2013. The ethnographic method consists of both observing the photographs present in the family (number, origin, method of conservation or presentation) and recording the words of their owners. The objective is on the one hand to document each image, and on the other hand to capture how they are viewed and commented on today.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the existence of photographic collections located outside Albania that originated in the activity of foreign photographers who visited the country during the communist period. Such collections are by definition dispersed and can be located only on a case-by-case basis. Robert Elsie’s research has led to discovery of certain such collections extending into the 1940s and 1950s.[13] The history of science applied to research on Albania during the communist period has led also to the rediscovery of a fund as rich as that of Wilfried Fiedler, an East German linguist who participated in scientific expeditions in the 1950s (de Rapper 2016b).[14]

Regardless of their accessibility, visual sources pose methodological challenges to historians and anthropologists alike, which for photography can be summed up in the ambiguity of its nature, which is both indexical and symbolic. Through its technical process photography constitutes a trace of a real event, but as an image it is susceptible to multiple and potentially contradictory interpretations.[15] That ambiguity requires researchers to contextualise the moment of the photograph and to pay attention to the reception of the images and the various readings to which they are subject at various times and in various places. Such double work requires that other types of source must be taken into account.

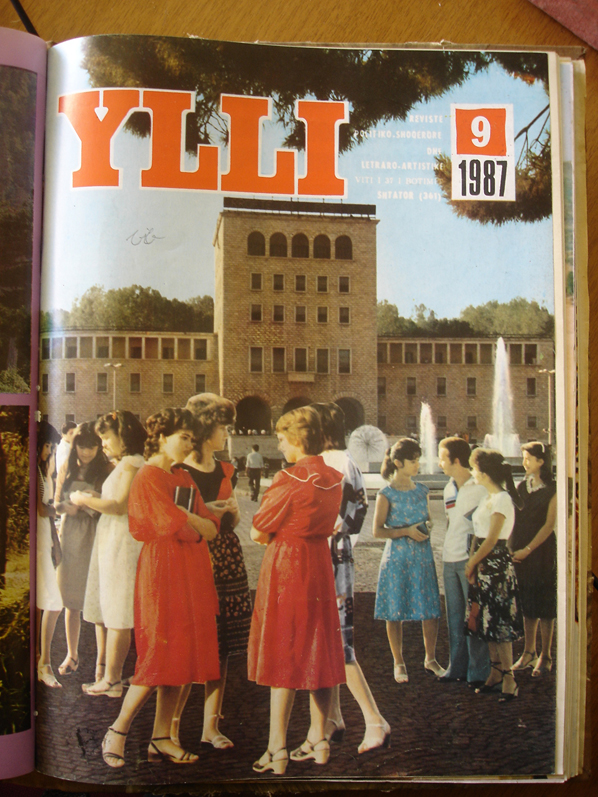

Traces and Testimonies

The photography of the communist period left traces other than the negatives and prints preserved in archives. Those objects indeed constitute fundamental visual and material data, analysis of which must be based on other types of source; in fact photographic prints are a first category of complementary source, with the press one of the first destinations of photographic production. There again, it was not until the 1960s that the technical means were available to publish photographs in high quality, but from that time onwards a number of magazines illustrated with photographs appeared regularly, the best known being Ylli (Durand and de Rapper 2012). Collections of magazines exist in most libraries and are easily accessible (Figure 18). Photographic prints are of course only a partial selection from the whole; they do, however, constitute a good example of the uses of photography and how photography fits into a discourse and a rhetoric. Works on the history of the communist press are few and do not always focus on photography (Fuga 2010; Boriçi and Marku 2010) although it is an important field in which discoveries remain to be made. In addition to the press, photographic albums were regularly published for propaganda purposes and like newspapers and magazines, such albums are an easily accessible source.

Cover from Ylli, September 1987. Courtesy: Gilles de Rapper, 2012. Copies of the magazine were bound in annual volumes and placed in public libraries. The magazine, monthly and richly illustrated, was distributed nationwide and was available on subscription. The September 1987 cover theme is the start of the new academic year and features a rare example of photo-montage by collage.

With the end of the state monopoly on book publishing and production, the 1990s saw a proliferation of books on local history, professional history, biographies and autobiographies focused on the communist period. Whether they contain photographs or report on the use of photographs, such books are a valuable source for contextualizing the production and transmission of images. Shortly before his death in 2013 the university professor and photographer Kostandin Leka published a book in which he detailed his efforts to introduce audio-visual teaching methods to the university, and his contribution to the setting up of a colour laboratory at ATSH in the 1980s. Perhaps just as interestingly, he described too his own experiments as an amateur photographer (Leka 2013). On the other hand, local historians have published accounts of villages here and there, or a small region; many illustrated their books with photographs that used to be exhibited in local museums, thus giving them new life and new meaning.[16] Finally, the flourishing trade in souvenir literature gives a great deal of information on the popular uses of photography as well as on some of the professional milieus in which photographers worked.

Beyond the content of such books, the whole emerging movement of “the memory of communism” must be observed while taking into account the role played by photography. During the first postcommunist decade photographs attracted little attention, being used primarily to denounce the crimes or failures of the political regime that had just collapsed. That was the case, for example, with part of the permanent exhibition of the National History Museum in Tirana during the 1990s. More recently, a new discourse is emerging, more memorial and less marked by the binary opposition between denunciation and glorification of the communist period. In the field of photography it is worth mentioning the initiative at the very end of the 2000s and beginning of the 2010s of former photographers, mainly from Tirana’s institutions, who sought to rehabilitate their work during the communist period. The association of the “bin masters” (Alb. mjeshtrat e baçinelave) thus aimed to highlight the professionalism, technical skill and artistic sense of these masters of film photography, in the face of the new generation of professionals who now take only digital photographs (Figure 19). Discreetly however, a new public discourse on photography from the communist period has grown, in line with current artistic practices through which the photography of that period is appropriated or diverted, not only to denounce a political regime but to express the feelings of nostalgia that this past now gives rise to.

Re-union of former photographers from the communist period, Tirana, 2009. Courtesy: Private collection, Tirana. Most of these photographers are still active in Tirana, either as independents or employed by public administrations or private companies.

A final type of source is oral interviews with former photographers or commissioners of photographs, as well as with those who posed for or possess photographs from the period. The well-known technique of “photo elicitation”, in which respondents are invited to look at photographs and give their opinions of them, whether they are their own images or images proposed by the interviewer, is particularly productive in this matter. The technique was introduced and formalised in the 1950s by John Collier (Collier and Collier 1986) and later theorised by anthropologists and sociologists such as Douglas Harper (2012, 155–187). The method provides information about the images themselves, about the time when they were taken and about the people and places depicted. It reveals too the subjects’ current reactions to and interpretations of photographs which, at the time of their production, carried a certain message. More broadly in such instances, the photograph is used to prompt discussion and reminiscence. What the respondents say might not relate directly to the images they have in front of them, but they nevertheless serve to support and evoke memories to contextualise the images. The oral survey is interested not only in the actual images but can focus on the professional and family trajectories of the photographers, on their working conditions and on the equipment and techniques they used. In this area, technical objects too should be considered—the cameras, enlargers, photographic paper, manuals, lamps, developing trays—both to document the working conditions of the photographers and to elicit more precise descriptions of technical gestures (Figure 20).

From an interview with an amateur photographer, Korçë. Courtesy: Gilles de Rapper, 2009. I. H., from a village in southeastern Albania, purchased his Russian-made Zorki camera in 1960 at the age of 22, with the support of his parents. He used it for years but now owns a digital camera sent to him by his sons who live in the United States. “It was the most precious thing I had”, he said during our meeting at his home.

But of course the oral survey is not limited to the photographers, who did not work alone but were surrounded by other technicians such as laboratory assistants, re-touchers, and archivists. Above all they worked within an institutional framework in which other people influenced the production of their photographs. In the case of print photography, they included the editors, journalists and graphic designers of illustrated magazines; and the managers of museums and cultural centres who commissioned photographs and therefore played their own roles in the production and conservation of images. Beyond the professional milieu users and consumers of photographs must be questioned so that we can acquire a different grasp on the whole process of producing photographs, whether in the studio or outdoors, and document the uses of photographs and their transmission from one generation to the next, right up until today.

On the whole, as can be seen, there is a huge quantity of accessible or potentially accessible material, and although the oldest witnesses are fading away and the longevity of the existing collections is not guaranteed, it is still possible to include photography when writing the history of communism in Albania. But to conclude, I shall return to how as an anthropologist I seized upon these photographic traces in order to construct a historical anthropology of communism in Albania, which is also an anthropology of postcommunist Albania.

My personal interest in photography of the communist era came relatively late, after more than ten years of ethnographic fieldwork in various regions of Albania. As an anthropologist I was not immediately concerned with the history of communist Albania, even though in the 1990s I saw everywhere the former system’s material traces in behaviour and ways of thinking and speaking. I was not trained in visual anthropology and never did much photography during my fieldwork. In fact and as I have described elsewhere it was through family photographs that I became interested in the photographic production of communist Albania (de Rapper 2017). In 2008 my path crossed that of the photographer Anouck Durand, who was interested in family photography as a genre and in its uses in the field of post-photography. She had published two narratives based on private photographic archives and was wondering what family photography looked like in a country that had experienced a political regime as restrictive and repressive as that of Enver Hoxha. Her interest in photography was in line with my own in family trajectories and their interaction with the system of surveillance and repression of the communist state (de Rapper 2006). Together therefore we conducted surveys over a number of years with former photographers and others involved in the production of photography, as well as with numerous families in several regions of Albania. That joint work resulted in a number of academic papers and publications but most importantly here, in the publication of a photographic novel written using archival images collected during our surveys, and interviews with former photographers (Durand 2017). A work of fiction based on testimonies and photographs from the period, the book is an example of the appropriation and recycling of archives from the communist period.

The sources left behind by the communist period are of interest to the history of Albanian photography in general, allowing us to reconstitute a particular moment in the history of photography, which we have called “the state moment”. Communist Albania is indeed a particularly clear example of how certain states seized on photography to make of it a primarily political activity.[17] Even within the communist world the overwhelming character of its state control and the longevity of it seem to make Albania a very special case.[18] The reconstruction of this state moment is also a way to counterbalance the dominant interest in the beginnings of photography or in the photography of the origins, which is particularly marked in Albania, just as it is in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean.[19] Finally, the state moment brings the history of photography in Albania closer to a general history of the medium, with the professionalization of photographers, the recognition of photography as an art form, and access to colour photography all themes that the sources allow us to address in Albanian contexts and that can provide a better understanding of certain general trends identified in the world history of photography. Beyond the international recognition of certain Albanian photographic figures—which seems to be the main objective of authors interested in the history of photography in Albania—the consideration of the communist moment can shed new light on processes of interest to the history of photography.

At a second level, the sources linked to photographic activity can contribute to the history of communism, in Albania and beyond. Tracing individual trajectories and the transformations of a professional environment, following technical developments and identifying the moments of rupture and the key events of an activity taken in its most technical aspects; all this allows access to the concrete functioning of the communist system. In the case of Albania, it has made it possible to refine and qualify the periodisation generally used for the communist period, by showing, for example, how successive political breaks were felt. The 1948 break with Yugoslavia led to an acceleration of the process of collectivisation of the profession, with the creation of cooperative photographic workshops. That of 1961 with the Soviet Union led to a tightening of control over photographic production, which culminated in complete state control at the end of the 1960s. The break with China in 1978 led to the 1980 reform towards centralisation, which saw a reorganisation of production in an increasingly difficult economic context. Apart from those historical dates, we can point to particular moments in photography. The 1960s, for example, saw a generational renewal of the profession and, above all, its feminization. Although women photographers were still rare in the central institutions, they were increasingly given laboratory tasks and the public photographic service employed many women, including for studio photography. We can also mention the beginning of the 1970s, which saw the rediscovery of ancient photography, the first attempts to write a history of photography in Albania and the emergence of demands from photographers for recognition of photography as art. Photographers requested the creation of a sector dedicated to photography at the League of Writers and Artists, in national exhibitions, and to be allowed to promote themselves and their work in the press. All of that reflects a professional awareness which, as we have seen with the Masters of the Bins, continued after communism. Finally, the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985 coincided with the multiplication of private practices on the margins of the state system of photographic production, which partly foreshadowed the dismantling of the system and its replacement in the early 1990s.

The survey also confirmed, in line with studies on everyday socialism, how far the “totalitarian” character of Albanian communism was more a matter of representation than of actual functioning. The history of the photographic profession so far traceable is indeed part of the context of a state with a vocation to organise and control the whole of its society, but it is clear that it saw its share of improvisation, failure, and contradiction.

Another example of the discrepancy between the common image of communist Albania and what is revealed by the survey of photographic production is the links photographers maintained with foreign countries throughout the communist period. Contrarily to the common image of Albania’s increasing isolation, it appears that the communist state never stopped depending on foreign countries for its photographic production. Because Albania produced none of the materials required for photographic production everything had to be imported and those imports from other communist countries continued unbroken despite the political schisms. The photographers of the main central institutions, the ATSH, the press, and scientific institutions were able to order photographic material from Western countries which from the 1970s onwards included Kodak colour film and expensive professional-quality cameras such as those by Hasselblad and Linhof. In some cases, photographers were even allowed to select and buy the equipment themselves from abroad, such as when a colour-printing laboratory was set up at the ATSH in 1981 with equipment bought in Italy (Leka 2013, 256). Finally, the same photographers could travel abroad for training and had access to foreign specialist literature in Albania. The ATSH laboratory, for example, continued to receive Soviet Photography magazine long after the break with the Soviet Union.

The investigation of photography also gives access to the entirely separate subject of the visual imagination of communism, not yet systematically explored for Albania even though recent work has shown what was playing out in other fields, in particular painting.[20] Such an investigation must of course take into account the other communist countries of the region and of Eastern Europe in general, to show both the convergences and divergences between them and Albania. The attempt to make photographic production a state monopoly and the extent to which photography participated in the surveillance and control of private lives certainly distinguishes Albania from other socialist states. A project could very well be based both on the collection and preservation of photographs from the communist period and on work on the social history of communism for all the Balkan countries and would create the opportunity for a dialogue between historians and anthropologists on the subject of the communist experience in southeastern Europe. The focus would then be on an essential dimension of communism, namely that it was a project aimed at bringing about new times and the “New Man” through a culture that was not only scriptural—already the subject of historical research—but visual too. And we can make the hypothesis that these images, some of which have remained in circulation or are being put back into circulation, are still effective not only in recalling the communist past and creating its memory, but also in qualifying the present and envisaging the future.

Given the quantity and quality of the available sources, whether visual, written or oral, it is regrettable that research on the communist experience in Albania does not make greater use of photography. That oversight may be explained by the dispersal of collections and the variable conditions of access, which in turn depend on the conditions of conservation, such as the condition of the actual photographic objects, and indexation. There is also the matter of copyright. We may think too that the methodological challenges posed by the interpretation of photographic material, well identified in relation to other periods or other spaces, including communist ones,[21] are only gradually being taken into account by researchers working on Albania. The vitality of research on the history and anthropology of photography outside the communist world should however encourage us to take full advantage of the visual sources available in Albania to contribute to the history of both photography and communism.

About the author

Gilles de Rapper is an anthropologist and CNRS researcher, currently Director of Modern and Contemporary Studies at the École française d’Athènes. Since 1994, he has conducted numerous fieldworks in Albania and the Balkans. His work has focused on the coexistence of Christians and Muslims in southern Albania, on cross-border relations between Greece and Albania and on the effects of Albanian migration to Greece. More recently, he has been interested in the trajectory of photographs produced during the socialist period in Albania and in their role in the current perception of the socialist past.

References

About, I., and C. Chéroux. 2001. “L’histoire par la photographie.” Études photographiques 10: 8–33.Suche in Google Scholar

Bardhoshi, N., and O. Lelaj. 2018. Etnografi në diktaturë. Dija, shteti dhe holokausti ynë. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave.Suche in Google Scholar

Begolli, S., and E. Begolli. 2005. Menkulasi e Dritëroit. Pogradec: D.I.J.A. Poradeci.Suche in Google Scholar

Behdad, A. 2016. Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226356549.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Boriçi, H., and M. Marku. 2010. Histori e shtypit shqiptar: nga fillimet deri në ditët tona. Tiranë: SHBLU.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (ed.) 1965. Un art moyen. Essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie. Le sens commun. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.Suche in Google Scholar

Carabott, P., Y. Hamilakis and E. Papargyriou (eds.). 2015. Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315570761Suche in Google Scholar

Çelik, Z,. and E. Eldem (eds.). 2015. Camera Ottomana. Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840–1914. Istanbul: Koç University Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Chauvin, L., and C. Raby. 2011. Albanie. Un voyage photographique, 1858–1945. Paris: Écrits de lumière.Suche in Google Scholar

Chéroux, C. (ed.) 2001. Mémoire des camps. Photographies des camps de concentration et d’extermination nazis (1933–1999). Paris: Marval.Suche in Google Scholar

Collier, J. J., and M. Collier. 1986. Visual Anthropology. Photography as a Research Method. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [original ed. 1967].Suche in Google Scholar

Colon, D. 2021. Propagande. La manipulation de masse dans le monde contemporain. Paris: Flammarion.Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. 2006. “La ‘biographie’: parenté incontrôlable et souillure politique dans l’Albanie communiste et post-communiste.” European Journal of Turkish Studies 4. https://journals.openedition.org/ejts/565 (accessed 1 October 2022).10.4000/ejts.565Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. 2016a. “Katjusha. La photographe du dictateur.” Ethnologie française 3 (163): 415–24.10.3917/ethn.163.0415Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. 2016b. “Visual Culture in Communist Albania: Photography and Photographers at the Time of the Stockmann-Sokoli Expedition (1957).” In Deutsch-Albanische Wissenschaftsbeziehungen hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang. Ed by E. Pistrick. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 113–28.10.2307/j.ctvc7709x.12Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. 2017. “La photographie de famille comme objet de recherche.” Science and Video 6. http://scienceandvideo.mmsh.univ-aix.fr/numeros/6/Pages/02.aspx. (accessed 1 October 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. 2020. “Albums de photographies et mémoire du communisme en Albanie.” Balkanologie 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.2485.Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G., and A. Durand. 2017a. “Au service du peuple. Coopératives et entreprises de photographes dans l’Albanie communiste.” In Penser le service public en Méditerranée. Le prisme des sciences sociales. Ed. by G. Gallenga and L. Verdon. Paris, Aix-en-Provence: Karthala, Maison méditerranéenne des sciences de l’homme, 219–44.Suche in Google Scholar

de Rapper, G. and A. Durand. 2017b. “Une autre image de l’Albanie communiste? Un essai d’ethnographie de la photographie amateur.” Ethnologie française 47 (2): 263–75.10.3917/ethn.172.0263Suche in Google Scholar

Demneri, Y. 2011. Më kujtohet. Tiranë: autoédition.Suche in Google Scholar

Didi-Huberman, G. 2003. Images malgré tout. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.Suche in Google Scholar

Dokle, N. 2014. Fotografët Safet e Gjylzade Dokle. Tiranë: Geer.Suche in Google Scholar

Durand, A. 2017. Eternal Friendship. Catskill, NY: Siglio Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Durand, A., and G. de Rapper. 2012. Ylli, les couleurs de la dictature. Paris: autoédition.Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards, E. and J. Hart (eds.). 2004. Photographs Objects Histories. On the Materiality of Images. New York, London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203506493Suche in Google Scholar

Elsie, Robert. n.d. Early Photography in Albania, http://www.albanianphotography.net/ (accessed 30 September 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Fishta, I., and M. Ziu. 2004. Historia e ekonomisë së Shqipërisë (1944–1960). Tiranë: Dita.Suche in Google Scholar

Fototeka Online. n.d. Drejtoria e Përgjithshme e Arkivave, https://fototeka.arkiva.gov.al (accessed 30 September 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Fuga, A. 2010. Monolog. Mediat dhe propaganda totalitare. Tiranë: Dudaj.Suche in Google Scholar

Harper, D. 2012. Visual Sociology. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203872673Suche in Google Scholar

Hirsch, M. 1997. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, Postmemory. Cambridge, Ma., London: Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoxha, E. 2017. Realizmi socialist shqiptar. Tiranë: Galeria Kombëtare e Arteve.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumi, P. 2013. Jeta përmes objektivit. Fotografi & shënime. Tiranë: Ideart.Suche in Google Scholar

Leka, K. 2013. Një jetë në shtjelljet e krijimtarisë. Tiranë: OMSCA-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Lelaj, O. 2015. Nën shenjën e modernitetit. Tiranë: Pika pa siperfaqe.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemagny, J.-C. and A. Rouillé. 1986. Histoire de la photographie. Paris: Bordas.Suche in Google Scholar

Mëhilli, E. 2017. From Stalin to Mao. Albania and the Socialist World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.10.7591/cornell/9781501714153.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Muho, Q., and L. Norra. 2009. Fushëbardha. Historia në vite. Gjirokastër: Argjiro.Suche in Google Scholar

Online Archive. n.d. Marubi National Museum of Photography, https://www.marubi.gov.al/archive (accessed 30 September 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Peffer, J. 2012. “Réflexions sur la photographie sud-africaine et l’extra-photographique.” Africultures 88: 210–226.10.3917/afcul.088.0210Suche in Google Scholar

Puto, A., and E. Gjikaj. 2008. “Kinematografia shqiptare midis nostalgjisë, groteskut dhe të ardhmes. Një histori treguar nga kineastët.” Përpjekja 25: 7–28.Suche in Google Scholar

Qëndro, G. 2014. Le surréalisme socialiste. L’autopsie d’une utopie. Paris: L’Harmattan.Suche in Google Scholar

Ragaru, N. 2010. “Les écrans du socialisme: micro-pouvoirs et quotidienneté dans le cinéma bulgare”. In Vie quotidienne et pouvoirs sous le communisme. Consommer à l’Est. Ed. by N. Ragaru and A. Capelle-Pogăcean. Paris: Karthala, 277–348.10.3917/kart.ragar.2010.01.0277Suche in Google Scholar

Selenica, T. 1928. Shqipria e ilustruar. L’Albanie illustrée. Albumi i Shqipris më 1927. Tiranë: Shtypshkronja Tirana.Suche in Google Scholar

Shevchenko, O. ed. 2014. Double Exposure: Memory and Photography. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Ulqini, K. 1982. Gjurmë të historisë kombëtare në fototekën e Shkodrës. Tiranë: 8 Nëntori.Suche in Google Scholar

Vrioni, Q. 2009. 150 vjet fotografi shqiptare. Tiranë: Milosao.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Making Sense of Archives

- Making Sense of Archives: An Introduction

- Archives of Mass Violence: Understanding and Using ICTY Trial Records

- Photographic Archives and the Anthropology of Communism in Albania

- The Franciscan Order of Things: Empire, Community, and Archival Practices in the Monasteries of Ottoman Bosnia

- Understanding Colonial Archives: Reflections on Records from Habsburg Times in the Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Article

- Welfare States and Covid-19 Responses: Eastern versus Western Democracies

- Policy Analysis

- Side Effects of “Phantom Pains”: How Bulgarian Historical Mythology Derails North Macedonia’s EU Accession

- Book Reviews

- Tibor Valuch: Everyday Life Under Communism and After: Lifestyle and Consumption in Hungary, 1945–2000

- Neven Andjelic: Covid-19, State-Power and Society in Europe: Focus on Western Balkans

- Jelena Džankić: The Global Market for Investor Citizenship. Politics of Citizenship and Migration

- Tatjana Sekulić: The European Union and the Paradox of Enlargement: The Complex Accession of the Western Balkans

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Making Sense of Archives

- Making Sense of Archives: An Introduction

- Archives of Mass Violence: Understanding and Using ICTY Trial Records

- Photographic Archives and the Anthropology of Communism in Albania

- The Franciscan Order of Things: Empire, Community, and Archival Practices in the Monasteries of Ottoman Bosnia

- Understanding Colonial Archives: Reflections on Records from Habsburg Times in the Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Article

- Welfare States and Covid-19 Responses: Eastern versus Western Democracies

- Policy Analysis

- Side Effects of “Phantom Pains”: How Bulgarian Historical Mythology Derails North Macedonia’s EU Accession

- Book Reviews

- Tibor Valuch: Everyday Life Under Communism and After: Lifestyle and Consumption in Hungary, 1945–2000

- Neven Andjelic: Covid-19, State-Power and Society in Europe: Focus on Western Balkans

- Jelena Džankić: The Global Market for Investor Citizenship. Politics of Citizenship and Migration

- Tatjana Sekulić: The European Union and the Paradox of Enlargement: The Complex Accession of the Western Balkans