Abstract

Although scant, the previous research on Guatemalan Spanish has suggested that both /f/ lenition, /f/ → [h], and /f/ fortition, /f/ → [p], are more common among Mayan-Spanish bilinguals with lower levels of education as /f/ is not present in any Mayan language. The present study analyzes 1,430 tokens of /f/ from sociolinguistic interviews in Spanish from 40 bilinguals of Spanish and the Mayan language K’iche’ according to both linguistic and extra-linguistic factors. Overall, both lenition and fortition were relatively infrequent. The results indicate that /f/ lenition is favored by the following phonetic contexts of [u̯i] and [u̯e] and by speakers with less formal education, especially for those who were more K’iche’-dominant. /f/ fortition is favored by previous nasals and pauses and by speakers who were more K’iche’-dominant. That is, while /f/ fortition is predicted by language dominance, /f/ lenition, similar to other varieties of Spanish, is most predicted by educational attainment, although with an interaction between education and language dominance. Thus, it is argued that in this community, /f/ lenition is due to sociolinguistic variation of a diachronic sound change while /f/ fortition is a result of language contact and processes of enregisterment. The findings indicate that sociolinguistic studies in bilingual communities must examine the role of education, language dominance, and the interaction between the two as language dominance does not inherently explain all variation in situations of language contact.

1 Introduction

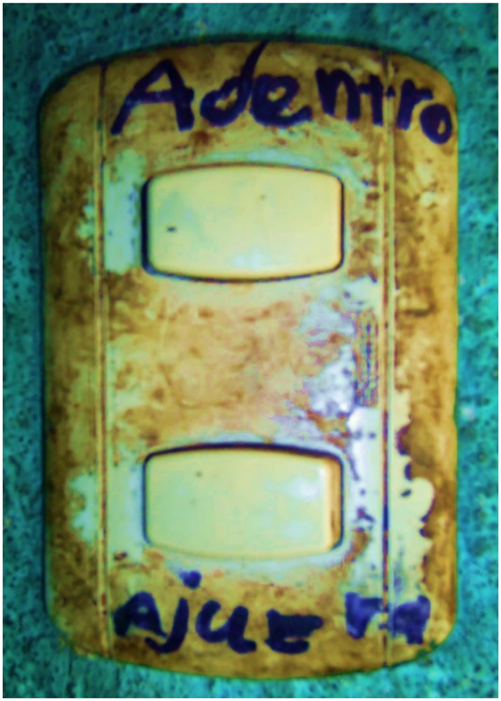

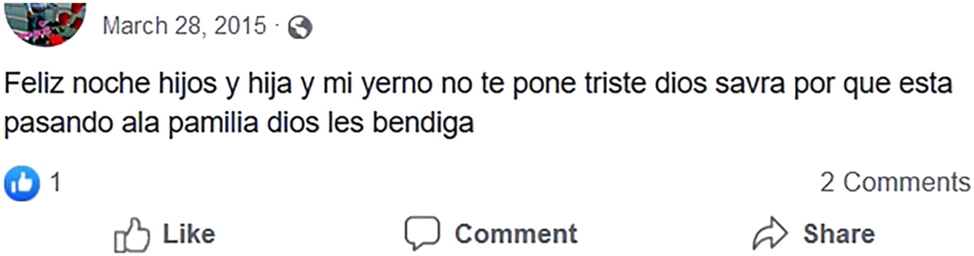

Phonemic conflict sites are defined as areas in which the phonemic inventories of two languages in contact differ (Stewart 2015, see also Poplack and Meechan 1988). As such, these sites may involve cases in which a particular phoneme exists in one of the languages but not the other. The outcomes of such phonemic conflict sites shed light on how speakers navigate differences between languages, how certain languages and dialects have evolved, and often inform us of larger, cross-linguistic tendencies of language contact and bilingualism in general. The focus of this study is one such phonemic conflict site: the voiceless labiodental fricative, /f/, that is part of the consonantal inventory of Spanish (Hualde 2005) but does not exist in any Mayan language (England and Baird 2017). Within the sociohistorical context of Guatemala, Spanish has been in contact with various Mayan languages since the 16th century and has resulted in ample cross-language influences between Spanish and Mayan languages (Baird forthcoming a). In particular, the Spanish /f/ has been reported to be realized in at least three different ways among speakers of Guatemalan Spanish: the canonical [f], a lenited, or aspirated, voiceless glottal fricative, [h], and, in cases of fortition as a voiceless bilabial stop, [p] (Aleza Izquierdo 2010; Alvar 1980; French and García Matzar 2023; García Tesoro 2008; Lentzner 1893; Predmore 1945; Utgård 2010). Orthographic representations of lenition, /f/ → [h], and fortition, /f/ → [p], in Guatemalan Spanish are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

A light switch in the K’iche’-speaking municipality of Nahualá, Guatemala. The switches are labeled as adentro ‘inside’ and ajuera ‘outside’, with the grapheme j taking the place of f in ‘outside’, denoting lenition (Photo by the first author).

Social media post of a K’iche’-Spanish bilingual from Nahualá illustrating the fortition of f amilia to p amilia ‘family’ (28 March, 2015. Retrieved from www.facebook.com).

/f/ lenition is well-documented in the historical literature on Spanish and has been found to occur across different varieties regardless of contact with other languages. However, research has also shown that language contact and bilingualism may be significant factors in the rate of /f/ lenition (Van Buren 2017). On the other hand, /f/ fortition is much rarer, and has only been ascribed to situations in which Spanish is in contact with languages that do not have /f/ (Chappell 2021; Flores Farfán 2000; Lipski 1987; Quilis 1996; Rodríguez Cadena 2008). To date, the existing literature on these realizations of /f/ in Guatemalan Spanish is sparse, consisting of brief mentions by a handful of different scholars (Aleza Izquierdo 2010; Alvar 1980; French and García Matzar 2023; García Tesoro 2008; Lentzner 1893; Predmore 1945; Utgård 2010). Thus, the primary goal of this paper is to provide the first quantitative acoustic sociophonetic study of /f/ in Guatemalan Spanish. As the aforementioned literature on /f/ in Guatemalan Spanish suggests that both lenition and fortition are more likely to occur in areas of intense contact and among bilinguals, the focus of this analysis is the speech of bilinguals of Spanish and the Mayan language K’iche’ (also spelled Quiché/K’ichee’). The rest of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on /f/ lenition and fortition in Spanish in general and in Guatemalan Spanish in particular. Section 3 reviews the methods including data collection, variables included, and statistical analyses. Section 4 presents the results while Section 5 discusses the results in connection to previous literature and overall conclusions are offered in Section 6.

2 Background

Five centuries of contact between Spanish and Mayan languages in what is now Guatemala have produced many expected results. Throughout Guatemala’s history, the Maya, their languages, and their cultures were deemed inferior to the Spanish language and to Ladino (non-Mayas in Guatemala) society. As in other contexts throughout Latin America, this has led to a general shift away from Mayan languages and culture (French 2010). Although recent political efforts have made progress on these fronts, these past few decades of language and cultural revitalization have not overcome centuries of oppression and attempts at extermination as the Maya, their languages, and their cultures continue to be viewed poorly by Ladinos and even by some Maya themselves (Baird 2019).

Even as some Mayan languages are losing speakers, they have left their mark on Guatemalan Spanish (Baird forthcoming a).[1] The use of different Mayan phonological and morphosyntactic features in Guatemalan Spanish has been described as either language specific, e.g., “K’iche’-accented”, “Mam-accented”, or, more generally, “Mayan-accented” Spanish (Romero 2015: 67). Phonemic conflict sites are often the epicenter of phonological characteristics of Mayan-accented Spanish, as seen in studies on stressed and unstressed vowels (Baird 2020, 2021a), stops (McKinnon 2020a, 2020b), and rhotics (Baird forthcoming b; McKinnon 2023), among others. As previously mentioned, the lack of /f/ in any Mayan language establishes the phonemic conflict site of interest in this study and two non-canonical allophonic realizations have been reported: [h] and [p].

2.1 /f/ lenition

The historical literature on the lenition/aspiration of /f/ is well-documented. According to most scholars, the variation between [f], [h] and even ∅ has been present in Spanish since before the early modern period and has gone through periods of allophonic loss and reintroduction (Brown and Raymond 2012; Lapesa 2008; Penny 2000, 2002; among others). This variability is reflected in the graphemes f and h, the latter not being pronounced, in etymologically related words: fumar [fuˈmaɾ] ‘to smoke’, versus humo [ˈumo] ‘smoke’ (Van Buren 2017: 163). According to Penny (2000: 45–46), word-initial /f/ in words of Latin origin that had become [h] were starting to be dropped altogether by the 16th century and this process was spread to the Americas. Of particular interest to contemporary cases of lenition, /f/ before /uV/ diphthongs was realized as a voiceless labiovelar fricative [ʍ] and, unlike initial [h], this allophone was maintained. Although it is not entirely understood why, /f/ was reintroduced into the phonemic inventory of Spanish and [f] became the canonical variant towards the end of the Middle Ages (Penny 2000: 72–73). Nevertheless, this allophonic variation in cases where /f/ preceded /uV/ still exists today, where non-canonical realizations of /f/ are associated with rural and lower socioeconomic-class speakers (Penny 2000: 163). The exact phonetic realization of non-canonical /f/ before /uV/ in contemporary Spanish varies; as [ʍ] may have become an aspirated, or debuccalized, voiceless glottal fricative [h], a voiceless velar fricative [x], a voiceless labiovelar fricative [ʍ], or a voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ] in different dialects (Penny 2000; Pensado 1993; Renaud 2014; among others). Nonetheless, an exact definition may be futile as distinctions between several of these variants are lost in this specific phonological context. For example, the difference between [h] and [ɸ] may be negligible as [h] generally assimilates in rounding before the rounded semivowel of the following /uV/ diphthongs and thus indistinguishable from [ɸ] (Ladefoged and Disner 2012). As such, we use the generally accepted variant [h] when discussing cases of /f/ lenition in this paper.

Studies on contemporary Spanish have demonstrated that rates of /f/ lenition are conditioned by both linguistic and extra-linguistic factors. Phonetically, /f/ lenition is most common preceding /uV/ diphthongs. In fact, in some studies it has only been found in this context (Van Buren 2017). Experimental work has demonstrated that some phonetic factors that promote [f]/[h] variation in Spanish include the ambiguity of these two fricatives before rounded vowels, such as /u/, both in terms of production and perception (Foulkes 1997; Greenlee 1992; Renaud 2014). Additionally, several studies have found that the preceding sound may also condition /f/ lenition. Specifically, it has been found to be more common after non-high vowels (Brown and Alba 2017; Brown and Raymond 2012; Mazzaro 2015) and after the voiced alveolar lateral /l/ (Mazzaro 2015). In some studies, stress appears to facilitate lenition as well, as lenition is more common in unstressed syllables (Brown and Alba 2017; Brown and Raymond 2012; Mazzaro 2015); however, stress was not a significant factor in Renaud (2014). Studies that have analyzed the effects of word position on /f/ lenition have produced conflicting results. For example, Mazzaro (2015) finds that word-initial position was a conditioning factor for lenition whereas Renaud’s (2014) analysis found no effect of word position on the lenition of /f/.

Concerning extra-linguistic factors, the sociolinguistic work on /f/ lenition in Spanish has produced some expected results that pattern after general sociolinguistic trends (Labov 2001): females and younger speakers have been shown to prefer the prescriptive “standard” [f] (Mazzaro 2015; Resnick 1975; Van Buren 2017). The most common variable associated with /f/ lenition in the literature is that of socioeconomic status, often analyzed via the proxy of education, as many authors have associated /f/ lenition with lower socioeconomic classes (Agüero Chaves 1962; Alvar 2013; Canfield 1981; Lipski 2008; Moya 1981; Parodi 2001; Penny 2000; Quesada Pacheco 2013; Resnick 1975; Zamora Vicente 1996). This correlation has been verified via quantitative studies such as Calvo Shadid (1996), Mazzaro (2015), Renaud (2014), and Van Buren (2017); Brown and Alba’s (2017) analysis demonstrated a trend in this direction that approached significance. As some of these authors explain, higher levels of education often go hand in hand with higher levels of literacy; as speakers’ knowledge of Spanish orthography increases, they are better able to connect the graphemes f and h with specific words, particularly those that are more frequent in everyday speech, and produce far less cases of non-prescriptive or “non-standard” realizations of /f/ (Mazzaro 2011: 164; Renaud 2014: 267).

Many of these studies investigate speakers that are bilingual and in language contact situations; however, few of them have analyzed bilingualism or language contact as a variable. Van Buren (2017) presents one of these few studies of the lenition/aspiration of /f/ in an investigation of Spanish monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual Mexican migrant workers in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Although some findings of /f/ lenition in this context parallel results in the abovementioned studies, Van Buren’s analysis reveals that education is not a significant variable among this population. However, bilinguals produce /f/ lenition at a lower rate than Spanish monolinguals. She hypothesizes that within this context, bilingualism is a sign of upward mobility and could be functioning as a proxy for socioeconomic class instead of education. Additional results from this study of bilinguals and monolinguals that contrast the previous studies include the heighted use of [h] among younger speakers, and a higher rate of [h] following the high vowel /i/.

In Guatemala, the context is not only multilingual, but also one in which the Spanish /f/ is found in a phonemic conflict site with Mayan languages. Although there are few studies on /f/ lenition in Guatemalan Spanish, one of the first is that of Lentzner (1893: 42), who briefly mentions that it is quite common among bilinguals. Predmore’s (1945: 278) description of Guatemalan Spanish states that /f/ is lenited among bilinguals, those with less education and in more colloquial speech, and that there is also an allophonic variant [ɸf]; this specific variant, however, has not been corroborated by any other researcher. Among speakers in southwestern Guatemala, Alvar (1980: 272) finds most cases of [h] in word-initial position and lenition is common before all vowels, not just /uV/ diphthongs. Speakers in Alvar’s study also associated /f/ lenition with lower socioeconomic classes and the Maya population. Utgård (2010: 58) states that [f] is by far the most common realization of /f/, but that lenited forms are more common before non-front vowels, especially before /uV/ diphthongs. Utgård also concludes that it is generally the older speakers that produce more lenition. Finally, French and García Matzar (2023) specifically list /f/ lenition among Kaqchikel-Spanish bilinguals as the direct result of a phonemic conflict site and only report it when preceding /uV/ diphthongs. In sum, the existing literature on /f/ lenition in Guatemalan Spanish offers some linguistic factors that may differ from other varieties of Spanish and mentions of extra-linguistic factors coincide with Spanish in general. In some cases, contact with Mayan languages is presented as a factor. However, these studies were largely based on observations and not quantitative statistical analyses, and none present any acoustic data.

2.2 /f/ fortition

Unlike /f/ lenition, the fortition of /f/ cannot be traced to any diachronic variation in Spanish, but to language contact. Across different varieties of Spanish, /f/ fortition has only been reported in specific areas of contact with languages that do not possess the phoneme. For example, Lipski (1987: 215) and Quilis (1996: 241) note that in the Philippines, /f/ → [p] occurs among bilinguals, especially those that speak Chavacano creole, Rodríguez Cadena (2008: 155) reports that in Colombian Spanish in contact with Wayuunaiki, “semi Spanish speakers” replace /f/ with [ph], as in “[kon p h amilia] ‘with family’”, and Chappell (2021: 189–190) states that it occurs in Nicaraguan Spanish in contact with Miskitu, as in [p]echa for [f]echa ‘date’. Outside of Guatemala, Flores Farfán (2000: 147) reports that some Spanish-Yucatec Maya bilinguals in Southern Mexico, especially those whose L1 is Yucatec Maya, produce /f/ fortition: “[p]ernando for [f]ernando”. Further examples of this process can be seen in the language in contact with Spanish. For example, in Spanish loan words in Mayan languages, /f/ is primarily replaced with /p/: Spanish /ˈfɾuta/ → K’iche’ /ˈprut/ ‘fruit’; Spanish /kaˈfe/ → K’iche’ /kaˈpe/ ‘coffee’ (Baird 2023b: 5).

Even though there is ample contact with Mayan languages, there has been some debate among scholars as to whether the fortition of /f/ to [p] occurs in Guatemalan Spanish. In one of the first accounts of Guatemalan Spanish, Lentzner (1893: 42) states that when Maya individuals “try to speak Spanish as an L2,” they replace the [f] with [p] and gives the examples such as p amilia for f amilia ‘family’ and p os p or for f ós f oros ‘matches’.[2] However, Alvar (1980: 272) refutes this claim, or at the least states that if did occur a century before when Lentzner first reported it, that it no longer occurs. On the other hand, García Tesoro (2008: 105–106) states that while /f/ fortition still occurs in Guatemalan Spanish, “we have only observed it among bilingual speakers with low levels of education.” Aleza Izquierdo (2010: 86) states that “[i]n zones with Mayan influence … the consonant /f/, which does not exist in Mayan languages, is pronounced as the bilabial occlusive [p] among bilinguals with low levels of education.” In the same year, Utgård (2010: 59) reports that “what Lentzner described in 1893 [fortition] has not been confirmed among the participants of this study.”

These mentions of /f/ fortition in Guatemalan Spanish in the literature are brief, as they are not the primary focus on these works. In fact, no one offers any linguistic factors that may condition /f/ fortition, nor any acoustic data. However, those that corroborate /f/ fortition bring up the same extra-linguistic factors; it primarily occurs among bilinguals with lower levels of education. In a pair of perception studies, Baird (2023a, 2023b) used the matched guise technique to analyze the sociolinguistic attitudes of /f/ fortition among native speakers of Guatemalan Spanish. The results corroborate the brief sociolinguistic comments of these previous authors as they demonstrate that /f/ fortition is highly stigmatized among Guatemalans and indexes a lower socioeconomic status and indigeneity.

2.3 The present study

Although the existing research on the lenition and fortition of /f/ in Guatemalan Spanish is sparse, two specific characteristics may be inferred. First, lenition appears to be more widespread than fortition, as the former is not disputed in the literature. Second, both lenition and fortition are more likely to occur among Spanish speakers that are bilingual in a Mayan language and have lower levels of education. However, as previously mentioned, the previous accounts lack acoustic data and quantitative analyses. As such, this study was guided by the following two research questions: First, what is the overall frequency of lenition ([h]) and fortition ([p]) realizations for /f/ present in the speech of simultaneous bilingual K’iche’-Spanish speakers? Second, what are the linguistic and extra-linguistic factors that condition the processes of lenition and fortition in the speech of simultaneous bilingual K’iche’-Spanish speakers?

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

In the summer of 2019, 40 K’iche’-Spanish simultaneous bilinguals (23 females, 17 males) participated in sociolinguistic interviews. All participants were from the municipality of Nahualá in the western highlands of Guatemala and ranged in age from 18 to 67 (M: 31.3, SD: 13.0). The participants varied in educational attainment in which 6 had completed less than a secondary education, 21 had completed secondary education, and 13 had at least some college education. Each participant completed the Bilingual Language Profile (henceforth BLP) (Birdsong et al. 2012) to examine language dominance. For reference, BLP scores range from −218 to +218 with a score of 0 being an idealized balanced-bilingual. In the current study, larger negative scores indicate more K’iche’ dominance, and larger positive scores indicates more Spanish dominance. Scores ranged from −83.9 (K’iche’-dominant) to 25.4 (Spanish-dominant) (M: −28.8, SD: 33.5). Of note is that 33 of the 40 participants were K’iche’-dominant according to the BLP scores. This is in line with the larger community of Nahualá as it has been shown to be a municipality with high levels of K’iche’-dominance among bilinguals (Baird 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021b).

3.2 Data collection and procedures

The sociolinguistic interviews were conducted in Spanish in Nahualá, Guatemala and ranged between 30 and 50 minutes in length. The sociolinguistic interviews included open-ended questions regarding themes such as cultural practices and personal histories to encourage naturalistic speech. All participants were recorded via a Marantz PMD661 digital voice recorder digitized at 16 bits (44.1 kHz) with a Shure SM10A head mounted microphone. The sociolinguistic interviews were conducted by K’iche’-Spanish simultaneous bilingual research assistants who were also from Nahualá and were the same biological sex as the participant and neither author was present during the interviews in order to reduce effects from the observer’s paradox (Labov 1972). The research assistants were trained by the first author in how to conduct a sociolinguistic interview.

3.3 Segmentation of tokens

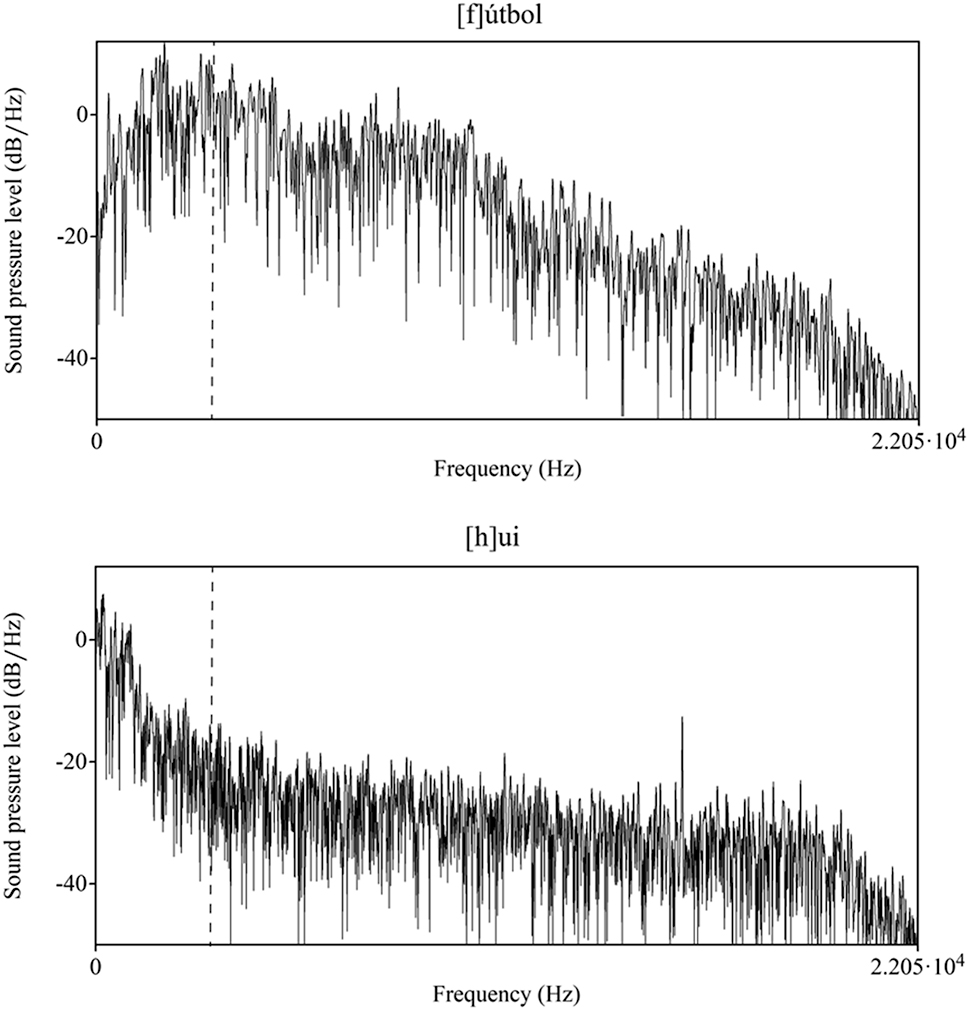

Textgrids in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2019) were created for each recording. A research assistant was trained to segment each word that contained an underlying /f/, resulting in 1,430 total tokens analyzed.[3] The first author then segmented each /f/ token in Praat. Based on both auditory and acoustic cues, the tokens were coded as [f], [h], or [p]. Both [f] (Figure 3) and [h] (Figure 4) demonstrated frication in the waveform and spectrogram. However, [f] tokens present a much higher center of gravity (Hz) than [h] tokens as noted in the spectrograms as well as much more frication as noted in the waveform. Furthermore, tokens coded as [f] had a sound pressure level (dB/Hz) that continues past 3,000 Hz whereas tokens coded as [h] had a sound pressure level (dB/Hz) that drops before 3,000 Hz (Ladefoged and Disner 2012) (see Appendix I). Finally, [p] realizations (Figure 5) were coded as any tokens that presented an occlusion of at least 20 ms or more.

![Figure 3:

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [f] token in fútbol ‘soccer/football’.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_003.jpg)

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [f] token in fútbol ‘soccer/football’.

![Figure 4:

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [h] token in fui ‘I went/I was’.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_004.jpg)

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [h] token in fui ‘I went/I was’.

![Figure 5:

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [p] token in enfermedad ‘illness/disease’.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_005.jpg)

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid of [p] token in enfermedad ‘illness/disease’.

3.4 Independent and dependent variables

For one of the extra-linguistic factors and several linguistic factors, the original coding included many more levels than the final statistical analysis. As several independent variables have many levels, and some of the levels had few tokens, this may result in a lack of convergence of a regression model, or result in Type I or Type II errors. To avoid these issues, data visualization was conducted for each independent variable to see if certain levels that behaved similarly and could be combined into one level. Thus, below we list the original levels for each factor, and then in some cases, the reduced number of levels.

Four extra-linguistic factors were included: sex, age, education, and language dominance. Age was considered a continuous variable. For education, participants were placed in the highest level of educational attainment: less than secondary education, secondary education, at least some college education, college education, and graduate education. Given the number of educational levels, we examined the data prior to conducting inferential statistics. The large cutoff in terms of linguistic practice was between those with secondary (or less) education and those with some college (or more) education.[4] Based on these observations, we reduced these categories into two levels: secondary (or less) education, some college education (or more). It should be noted that the current study examines education not necessarily as a proxy for social class, but rather as a factor in its own right. Several variationist studies have utilized a socioeconomic index (Cedergren 1973; Labov 1966, 1972, 2001; Trudgill 1972; Wolfram 1969) that includes occupation, education, and income. Many studies have used education as a proxy for social class. However, the end goal of those studies is not to study social class, but rather that “class is meant to model the socioeconomic hierarchy of a community” (Tagliamonte 2012: 25), and not necessarily a “discrete set of identifiable classes” (Labov 2001: 113), to see how said socioeconomic hierarchy reveals “dynamics of language variation and change” (Mallinson and Dodsworth 2009: 265). It has been suggested that “linguists might treat education as a separate variable, independent of social class” (Ash 2013: 356) as previous studies demonstrate that education may not “contribute to the social stratification of speakers.” As previous /f/ studies (Mazzaro 2011: 164; Renaud 2014: 267) have indicated, more years of formal education is a direct connection between literacy, orthography, and more prescriptive phone-to-grapheme realizations. Thus, education will be treated solely as referring to education. There is most likely some collinearity with social class, as is common in many communities, but this study is more interested in the effect of formal education (i.e., literacy and orthography) on /f/ lenition and fortition. Finally, language dominance was measured based on a continuous BLP score (Birdsong et al. 2012) from −218 to +218. Prior to statistical analyses, both age and BLP were normalized and scaled using the scale() function in R so that they were centered at zero with a standard deviation of one.

For the extra-linguistic factors, prior to running any models, we examined any important differences or possible examples of collinearity that would confound the models. A Pearson correlation was conducted to examine collinearity between speaker age and BLP score. There was a close to (but not) significant weak negative correlation between age and BLP score (n = 40, df = 38, r = −0.298, R2 = 0.088, p = 0.062). Thus, we included both independent variables within the analysis. However, it should be noted, given how close to significant this correlation is, that any age-related effects should be taken with caution. To examine if there were differences in BLP scores based on educational attainment we conducted a Paired Welch two-sample t-test and found that those with more some college (or more) education (M: −11.37, SD: 38.7) were overall slightly less K’iche’-dominant than those with secondary (or less) education (M: −37.18, SD: 37.62), p = 0.045. While barely significant, this would indicate that there is some amount of collinearity between the two variables. However, the authors decided to include them in the same models as educational attainment and language dominance are not two measures of the same variable. Finally, to examine whether there were any BLP score differences between the male and female speakers, a Paired Welch two-sample t-test was conducted and found that there were no significant differences in BLP scores between the female speakers (M: −29.70, SD: 29.03) and male speakers (M: −27.57, SD: 39.61) included in the sample, p = 0.853.

Four linguistic factors were also considered: previous segment, following segment, sentence position, and lexical stress. For previous segment, there were originally five levels, including: pause, vowel, nasal, liquid, fricative. Following previous research (Stivers et al. 2009), a pause was coded when there were 250 ms or longer of no speech prior to the segment. This was later reduced into three levels: other, pause, nasal. For following segment, it was originally coded with eleven levels including: [a], [e], [i], [i̯a], [i̯e], [l], [o], [ɾ], [u], [u̯e], and [u̯i].[5] This was then reduced to three levels: [u̯e], [u̯i], and other. Position in the sentence included three levels: beginning, middle, and end. Lexical stress was a binary coding of tonic or atonic. Finally, speaker was considered as a random factor.

The dependent variable was the segmental coding of [f], [h], and [p]. As described below, these were treated as a binary dependent variable of [f] versus [h] (lenition) and [f] versus [p] (fortition).

3.5 Statistical analysis

Prior to regression modeling, a random forest was conducted using the cforest function from the party package (Hothorn et al. 2020) to determine the importance of each independent variable prior to conducting regression analyses following Tagliamonte and Baayen (2012). This is important as the order in which independent variables are placed into each model may affect the output. Thus, according to the results from the random forest, independent variables were placed into order of importance within the regression models.

The current study employed a Bayesian approach instead of a frequentist approach for two principle reasons. First, the Bayesian approach allows for mixed effects with logistic and multinomial regressions, while the frequentist only allows mixed effects for a logistic regression. Second, a common issue with frequentist approaches, particularly that of logistic regressions, is (quasi-)separation in which “one predictor completely or almost completely separates the binary response in the observed data” (Kimball et al. 2019: 231). This is highly problematic for logistic mixed effects models (i.e., glmer) as separation or quasi-separation can then “cause problems for model estimation that result in convergence errors or in unreasonable model estimates” (Kimball et al. 2019: 231) in which some estimates “become extremely- even infinitely- large” (Fonteyn and Petré 2022: 86). This particular issue was found in exploring the data with frequentists models, hence the authors employed a Bayesian approach to avoid (quasi-)separation issues following previous literature (Fonteyn and Petré 2022; Kimball et al. 2019).[6]

Using the information from the random forest, a three-way ([f], [h], [p]) mixed-effects multinomial Bayesian regression models were conducted in R (R Core Team 2024) using the brm package (Bürkner 2017). However, after running several models, particularly those that included the most important independent variables (according to the random forest), there were too many error messages to continue (i.e., transition issues after warmup, R-hat values well above 1.1, too low of a Bulk Effective Sample Size, too low of a Tail Effective Sample Size). A multinomial regression, as compared to logistic regressions, requires significantly more data. Hence, the warnings for Effective Sample Size (Bulk and Tail) and R-hat value issues would indicate that we do not have enough data to run a mixed effects multinomial regression.

Thus, statistical analyses were separated for lenition ([f] and [h]) and fortition ([f] and [p]) into two Bayesian mixed effects logistic regressions using the brm function in R from the brms package (Bürkner 2017). One difference between a frequentist and a Bayesian approach is that of having constraints on the model parameters. In frequentist models, the values of β are assumed to be equally likely, ranging from “negative infinity to infinity” (Kimball et al. 2019: 238). Bayesian approaches, on the other hand, allow the researcher to begin with starting constraints, known as priors, which help avoid the over estimation of effects when there is quasi-separation or separation issues (2019: 238). Thus, rather than assume that estimates range from negative infinity to infinity, the current model begins with the assumption that most values will be near zero and thus the priors for all models were “weakly informative priors” using the following code: c(set_prior(“normal(0,1)”, class = “b”)). To determine which was the best model, we utilized the Bayesian leave-one-out cross validation (LOO-CV; Vehtari et al. 2017) method using the loo function in which the best model has the lowest LOOIC score. Finally, the visualization of the data was created with ggplot2 (Wickham 2016). Given that many interactions in each model would not allow the regressions to converge, a conditional inference tree using the cforest function in the party package (Hothorn et al. 2020) was conducted to examine possible interactions.

4 Results

Below we examine the results in terms of lenition and fortition. However, prior to this, here we present a global view of the variation. Of the 1,430 total tokens, there were 1,288 [f] tokens (90.07 %), 71 [h] tokens (5.0 %), and 71 [p] tokens (5.0 %) (see Appendix II for individual speaker token counts). Thus, prior to presenting the inferential statistics, the descriptive statistics indicate that overall neither lenition nor fortition is frequent in the data.

4.1 Lenition: [f] & [h] variation

The random forest results indicate that for [h]/[f] variation, the most important predictor is following sound, followed by educational attainment, speaker, scaled BLP score, syllabic stress, sex, scaled age, previous sound, and finally, sentence position (Figure 6). Of note, syllabic stress was not included in the regression modeling for [h]/[f] variation due to its collinearity with following sound (that is, [u̯i] and [u̯e] contexts are almost always in the tonic syllable).

![Figure 6:

Random forest of [h]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_006.jpg)

Random forest of [h]/[f] variation.

A Bayesian mixed effects regression model was conducted. The best fit Bayesian mixed effect logistic regression model is shown in Table 1. Of note, the reference level for realization was [f], coded as 0, and [h] realizations were coded as 1. The model selected is that with the lowest LOOIC vales (see Appendix III for loo() model comparison).

Best fit Bayesian mixed effects logistic regression model for [h]/[f], speaker as a random factor n = 1,359 (1.0 for Rhat indicates a convergence).

| Population level effects | Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | Rhat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −6.22 | 0.72 | −7.72 | −4.88 | 1.0 |

| FollowingSound (Ref = Other) | – | – | – | – | – |

| [u̯e] | 2.59 | 0.62 | 1.38 | 3.80 | 1.0 |

| [u̯i] | 2.23 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 3.58 | 1.0 |

| Education (Ref = SomeCollegeOrMore) | – | – | – | – | – |

| SecondaryOrLess | 0.67 | 0.66 | −0.62 | 1.98 | 1.0 |

| BLP | −0.06 | 0.47 | −0.98 | 0.85 | 1.0 |

| Sex (Ref = Female) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Male | −0.75 | 0.46 | −1.66 | 0.16 | 1.0 |

| FollowingSound:Education | – | – | – | – | – |

| [u̯e]:SecondaryOrLess | 1.98 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 3.24 | 1.0 |

| [u̯i]:SeconaryOrLess | 2.69 | 0.70 | 1.34 | 4.08 | 1.0 |

| Education:BLP | – | – | – | – | – |

| SomeCollegeOrMore:BLP | −0.77 | 0.53 | −1.83 | 0.26 | 1.0 |

The model indicates a strong effect of following sound in which both [u̯i] and [u̯e] strongly favor [h] realizations in comparison to other following sounds. The next strongest predictor was the interaction between following sounds and education in both following diphthongs, [u̯e] and [u̯e], most favor [h] realizations among those with secondary (or less) education (Figure 7). Education as a simple predictor also indicated that those with some college education or more strongly disfavor [h] realizations compared to those with secondary (or less) education. The next strongest predictor was the interaction of education and BLP score in which those with some college or more, regardless of language dominance, show little to no [h] realizations (Figure 8). On the other hand, among those with secondary or less education, language dominance plays more of a role in which higher K’iche’-dominant speakers produce more [h] than speakers who are less K’iche’-dominant or more Spanish-dominant. The model also showed a relatively weak effect for the BLP score in which those with lower negative BLP scores (i.e., very K’iche’-dominant speakers), produce more [h] than those with less negative BLP scores or positive BLP scores (less K’iche’-dominant and Spanish-dominant speakers). Finally, there was a simple effect for sex in which women favored [h] more than men.

![Figure 7:

Interaction of following sound and education for [h]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_007.jpg)

Interaction of following sound and education for [h]/[f] variation.

![Figure 8:

Interaction of education and BLP score for [h]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP values as opposed to the scaled values in the model).](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_008.jpg)

Interaction of education and BLP score for [h]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP values as opposed to the scaled values in the model).

To explore the relationship between the fixed factors in the above model, a conditional inference tree was conducted. As seen in Figure 9, the model demonstrates that the most important predictor, similar to the random forest, is that of following sound, in which there are no [h] realizations for other following sounds but is only produced in the context of a following [u̯e] or [u̯i] diphthongs. Within the context of these diphthongs, it is then only those with secondary or less education who produce [h] realizations, while those with some college education or more generally realized an [f] even in the context of these following diphthongs. For those with only secondary or less education, the most K’iche’-dominant speakers (less than −71.65) produce more [h] than those who are less K’iche’ dominant. Among those with secondary (or less) education, women produce more [h] than men.

![Figure 9:

Conditional inference tree of factors that predict [h]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_009.jpg)

Conditional inference tree of factors that predict [h]/[f] variation.

4.2 Fortition: [f] and [p] variation

The random forest results indicate that for [p]/[f] variation, the most important predictor is previous sound, followed by speaker, scaled BLP score, syllabic stress, educational attainment, following sound, scaled age, sex, and finally, sentence position (Figure 10).

![Figure 10:

Random forest of [p]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_010.jpg)

Random forest of [p]/[f] variation.

The best fit Bayesian mixed effect logistic regression model for [p]/[f] variation is shown in Table 2. Of note, the reference level for realization was [f], coded as 0, and [p] realizations were coded as 1. The model selected, that with the lowest LOOIC values (see Appendix IV for loo() model comparison) is more complex than what the frequentist models would allow.

Best fit Bayesian mixed effects logistic regression model for [p]/[f], speaker as a random factor n = 1,359 (1.0 for Rhat indicates a convergence).

| Population level effects | Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | Rhat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −6.13 | 0.77 | −7.85 | −4.8 | 1.0 |

| Previous Sound (Ref = Other) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pause | 1.95 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 2.89 | 1.0 |

| Nasal | 3.48 | 0.48 | 2.55 | 4.42 | 1.0 |

| BLP | −1.13 | 0.59 | −2.33 | 0.01 | 1.0 |

| Stress (Ref = Atonic) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tonic | −0.61 | 0.34 | −1.30 | 0.04 | 1.0 |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.51 | −0.93 | 1.09 | 1.0 |

| PreviousSound:BLP | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pause:BLP | −0.88 | 0.60 | −2.07 | 0.26 | 1.0 |

| Nasal:BLP | −1.85 | 0.63 | −3.12 | −0.66 | 1.0 |

The model revealed that previous sound is the strongest predictor of [p] realizations in which a previous nasal most favors [p] realizations, followed by a previous pause, as compared disfavor [p] realizations (Figure 11A). Another linguistic factor, syllabic stress, demonstrated a simple effect into which atonic syllables favored [p] realizations more than tonic syllables (Figure 11B). The model also showed an effect for the BLP score in which those with lower negative BLP scores (i.e., K’iche’-dominant speakers), produce more [p] than those with less negative BLP scores or positive BLP scores (i.e., Spanish-dominant speakers) (Figure 12A). However, the interaction between BLP and following sound demonstrates that those who are most K’iche’-dominant produce more [p] than those who are less K’iche’-dominant or Spanish-dominant in the context of a previous nasal and also with a previous pause (Figure 13). Finally, the model demonstrated a very weak effect for age in which older speakers produced more [p] realizations than younger speakers (Figure 12B). As mentioned previously, age nearly correlated with BLP scores. Between that, and the low estimate, this simple effect should be taken with caution.

![Figure 11:

Simple effects of previous sound (A) and syllabic stress (B) for [p]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_011.jpg)

Simple effects of previous sound (A) and syllabic stress (B) for [p]/[f] variation.

![Figure 12:

Simple effect of BLP score (A) and for Age (B) for [p]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP scores and Age values as opposed to the scaled values in the model).](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_012.jpg)

Simple effect of BLP score (A) and for Age (B) for [p]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP scores and Age values as opposed to the scaled values in the model).

![Figure 13:

Interaction of previous sound and BLP for [p]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP scores as opposed to the scaled values in the model).](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_013.jpg)

Interaction of previous sound and BLP for [p]/[f] variation (note: these are the actual BLP scores as opposed to the scaled values in the model).

To explore the relationship between the fixed factors, a conditional inference tree was conducted. As seen in Figure 14, the model demonstrates that the most important predictor is previous sound. For previous nasal segments, the model shows this interacts with BLP score in which the model separates those with a score of −33.6 and even more negative (i.e., K’iche’-dominant speakers) as the speakers most producing [p] with previous nasal segments. Then following the tree, for previous pause, it interacts with syllabic stress in which overall there is more [p] with atonic syllables, but again, among the most K’iche’-dominant speakers. Then for other previous segments, this again interacts with BLP. However, it appears to segment off one K’iche’-dominant speaker (with a score of −78.8) who produced a high number of [p] and thus this particular partitioning should be taken with caution (the same model was run with age and this same speaker (age 46) was separated from the group).

![Figure 14:

Conditional inference tree of factors that predict [p]/[f] variation.](/document/doi/10.1515/shll-2025-2001/asset/graphic/j_shll-2025-2001_fig_014.jpg)

Conditional inference tree of factors that predict [p]/[f] variation.

5 Discussion

5.1 Returning to the research questions

Here we review the results in connection to the research questions and previous studies, followed by theoretical implications. Regarding the first research question (What is the overall frequency of lenition ([h]) and fortition ([p]) realizations for /f/ present in the speech of simultaneous bilingual K’iche’-Spanish speakers?), the overall frequency of /f/ lenition and /f/ fortition is relatively low. Specifically, for lenition, [h] only accounted for 5.0 % of all realizations. This low frequency of [h] realizations supports Utgård’s (2010) findings that [f] is the more common realization with few [h] realizations in Guatemalan Spanish. Similarly, regarding [p] fortition, [p] realizations only accounted for 5.0 % of all realizations. While overall few in number, this data supports previous studies that /f/ fortition does occur in Guatemalan Spanish (Aleza Izquierdo 2010; García Tesoro 2008; Lentzner 1893), while contradicting claims that it no longer occurs in Guatemalan Spanish (Alvar 1980; Utgård 2010). However, the overall low number of [p] tokens among this particular population, which is quite K’iche’-dominant, may help explain these contradictions in the literature. It is certainly feasible that /f/ fortition would not be found at all among groups of speakers in Guatemala that are either monolingual in Spanish or Spanish-dominant bilinguals.

While frequency (Bardovi-Harlig 1987) can play a role in salience, a lack of frequency does not inherently indicate a lack of salience with these features. As Babel (2011) notes in cases of language contact, it is essential to understand the process of enregisterment (Agha 2005, 2007). Agha (2005: 38) defines enregisterment as “processes whereby distinct forms of speech come to be socially recognized (or enregistered) as indexical of speaker attributes by a population of language users.” As seen through Spanish-Quechua contact, Babel (2011: 59) states that enregisterment “can be described as the historical process by which people link linguistic signs to social meanings, producing relationships between signs and social categories (in other words, linguistic features become indices of social categories and stances).” These features tend to occur more in informal conversations than in more formal contexts (Babel 2011: 88). Of importance is that whether these linguistic features are frequent or not, the process of enregisterment allows for such features to be associated with social groups (Babel 2011: 88) so that even infrequent realizations may still index social meaning. For example, the celebrated Guatemalan author Flavio Herrera employed /f/ fortition for words like empermo ‘sick’ when depicting the spoken dialogue of Maya, but not Ladino, characters in his novels (1935: 145). Quantitatively, the results from Baird’s (2023a, 2023b) social perception studies examining the evaluations of stimuli with [f] and [p] realizations for /f/ also support that [p] realizations have undergone this process of enregisterment. Baird found that listener responses indicated that [p] realizations remain a stereotypical feature of the Maya and is highly stigmatized in Guatemalan Spanish. Thus, even if used infrequently, the process of enregisterment (Agha 2005, 2007) allows for [p] realizations to have salient semiotic associations for Guatemalan listeners, including for previous linguists’ descriptions of the Guatemalan Spanish. Furthermore, as orthography (Regan 2022: 503; Trudgill 1986: 11) has been shown to play a role in salience, the phone-to-grapheme mismatch may contribute to making [p] realizations salient, even if infrequent.

In terms of the second research question (What are the linguistic and extra-linguistic factors that condition the processes of lenition and fortition in the speech of simultaneous bilingual K’iche’-Spanish speakers?), we first discuss lenition. The strongest predictor was the linguistic factor of following sound in which /f/ followed by the diphthongs [u̯i] and [u̯e] were most likely to favor lenition. This finding that /f/ followed by /uV/ leads to lenition is supported by previous studies (Penny 2000; Utgård 2010; Van Buren 2017; among others). This particular phonetic context is one that has been in diachronic variation between [f] and [h] across many varieties of Spanish (Penny 2000: 72). The simple effect of education in which those with lower educational attainment favor /f/ lenition more than those with more educational attainment also supports previous studies (Mazzaro 2011; Predmore 1945; Renaud 2014; among others). As indicated by previous scholars who have analyzed /f/ lenition (Mazzaro 2011: 164; Renaud 2014: 267), more formal education indicates speakers have been exposed to more prescriptive phone-to-grapheme realizations. It is of interest, however, that following sound and education interact indicating that those with less educational attainment are most likely to produce the diachronic variation following [u̯i] and [u̯e].

The simple effect of BLP (language dominance), with a very weak estimate, suggests that those who are most K’iche’-dominant favor /f/ lenition more than those who are less K’iche’-dominant or Spanish-dominant. Of all the previous /f/ studies, only Van Buren (2017) examined the role of bilingualisms in /f/ lenition and found what may appear to be the opposite tendency in which Spanish-English bilinguals were less likely to produce [h] than Spanish monolinguals. However, there are several differences between Van Buren’s (2017) bilingual population and those of Nahualá. First, migration plays a significant role for Spanish-English bilinguals in the Pacific Northwest, while it is not a factor in Nahualá, Guatemala; all participants in this study were from Nahualá. Also, English, different from K’iche’, has the phoneme /f/, which does not make this a phonemic conflict cite among Spanish-English bilinguals as it does for K’iche’-Spanish bilinguals. Nevertheless, when considering the social status of these languages, the results of this study corroborate Van Buren (2017). In the Pacific Northwest of the United States and in Nahualá, Guatemala, individuals that speak or are more dominant in the language that symbolizes upwards mobility are less likely to lenite /f/ in Spanish, regardless of what the institutionally prestigious language may be: English in the United States and Spanish in Guatemala. Additionally, while the simple effect of language dominance is of interest here, it is more important to examine the interaction between language dominance and education, which demonstrated a larger estimate in the model. That is, the current study found that /f/ lenition is most common among those who are most K’iche’-dominant who have secondary or less education. On the other hand, K’iche’-dominant speakers with some or more college education demonstrated almost no /f/ lenition similar to Spanish-dominant speakers with some or more college. Thus, /f/ lenition cannot simply be attributed here to language dominance, but rather an example of diachronic variation that varies in large part due to phonetic context and educational level.

The simple effect of speaker sex demonstrated that women produce more [h] than men. The conditional inference tree indicates that this is most true among women with less formal education. This would present a counter example to the Principle 2 of the “Gender paradox” (Labov 1990: 210: 2001 266) that states that in stable linguistic variation, that in general, women produce more of the institutionally prescribed variant than men. However, given the few tokens in this study, this finding should be taken with caution.

Regarding fortition, the strongest predictor was previous sound in which previous nasals most favored /f/ fortition, followed by a previous pause, while other previous sounds disfavored /f/ fortition. These coincide with positional factors that promote fortition cross-linguistically. Specifically, it is more common for fortition to occur in what Ségéral and Scheer (2008: 135) refer to as “strong positions” in which the articulators are already found in positions that facilitate fortition. In Spanish, the most common “strong positions” tend to be immediately following a nasal or a pause. For example, /b, d, g/ are often produced as stops in these positions, or that fortition is maintained, whereas they tend to undergo lenition elsewhere (Hualde 2005; among many others). As such, the speakers in this study that produce /f/ fortition appear to be following a similar fortition/lenition allophonic distribution as in /b, d, g/. There was also a simple effect of syllabic stress in which atonic syllables slightly favored /f/ fortition, although this should be taken with caution as the model indicated low estimates for this simple effect.

The simple effect of BLP (language dominance) indicated that /f/ fortition was favored by those who are most K’iche’-dominant more than those who are less K’iche’-dominant or Spanish-dominant. This supports previous studies in Guatemala that attribute /f/ fortition to bilinguals (Aleza Izauierdo 2010; García Tesoro 2008; Lentzner 1893) as well as previous studies that document /f/ fortition in Spanish due to contact with other languages such as Chavacano in the Philippines (Lipski 1987; Quilis 1996), Wayuunaiki in Colombia (Rodríguez Cadena 2008), Miskitu in Nicaragua (Chappell 2021), and Yucatec Maya in Southern Mexico (Flores Farfán 2000). Finally, it should be noted that BLP interacted with previous sound in which those who were most K’iche’-dominant demonstrated more [p] more so with a previous nasal or a previous pause, indicating that even those who are K’iche’-dominant demonstrated very little [p] realizations with other previous sounds.

The simple effect of age is of note. This may suggest a change in progress (Labov 2001) in this community. However, this notion should be taken with caution for three reasons: (i) the very weak estimate in the model, (ii) the overall number of tokens, and (iii) the near close significant correlation between age and BLP score. Future studies should explore this in depth with more tokens and a larger population size.

5.2 Theoretical implications

The role of education warrants further discussion. In variationist sociolinguistics it has been common to include education, with both occupation and residence value to form a socioeconomic index (Labov 2001: 60–61) while other studies have used education by itself as a proxy for social class (Agüero Chaves 1962; Aleza Izquierdo 2010; Alvar 1980, 2013; Canfield 1981; García Tesoro 2008; Moya 1981; Penny 2000; Quesada Pacheco 2013; Resnick 1975; Zamora Vicente 1996). However, the current study has followed the suggestion from Ash (2013: 356) that sociolinguists examine education as a separate factor from social class. Surprisingly, within the sociolinguistic literature, there is a lack of discussion of the role of orthography within the educational system in sociophonetic variation. This may perhaps be due to the fact that much sociolinguistic theory is based on studies examining English (Docherty and Mendoza-Denton 2012: 47). In general, the English language has a poor phone-to-grapheme correlation, and as such may not be as much as a factor within English sociophonetic variation. The role of orthography, particularly in the context of a grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence, is fundamental to understand /f/ variation in the present study. Orthography has been shown to be key in sociophonetic variation in non-English languages. For example, previous studies have demonstrated a split of a phonetic merger is possible where there are grapheme-to-phoneme correspondences (Lin 2018: 41; Regan 2020: 184, 2022: 503). Thus, if one has increased educational attainment, they will be exposed to prescriptive phone-to-grapheme realizations. As stated by previous scholars (Mazzaro 2011: 164; Renaud 2014: 267), increased educational attainment indicates more exposure to the prescriptive phone-to-grapheme for /f/ realizations in the Spanish-speaking world.

Of importance in the discussion of education is that of language dominance. As much of sociolinguistic theory is based on monolingual varieties, it is important to note that language dominance must be given more consideration. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that education is not necessarily correlated with language dominance in any given community. For example, Baird (2019) found that in Nahualá, many relatively highly educated people make conscious efforts to be K’iche’-dominant. Accordingly, it is crucial in bilingual communities to not only look at possible simple effects of education and language dominance, but at the interaction between the two. In the current study, we see that /f/ lenition ([h]) is most predicted by educational attainment, especially among those who are most K’iche’-dominant, but not simply being K’iche’-dominant favors [h] production. However, then when we examine /f/ fortition ([p]) this does demonstrate a more direct relationship with language dominance.

While the overall frequency of fortition ([p]) and lenition ([h]) is the same, it is interesting to note that different independent variables govern these realizations. While we acknowledge the linguistic factors that govern these realizations (following sound for lenition and previous sound for fortition) as described below, here we briefly focus on the social factors. It is noteworthy that educational attainment was only significant for /f/ lenition. Both /f/ lenition and /f/ fortition present cases of phone-to-grapheme mismatch (read: prescriptively <f> = /f/).[7] Previously, studies have noted that orthography (Regan 2022: 503; Trudgill 1986: 11) has been shown to play a role in salience. Given this salience, one would predict that more years in the educational system would favor the orthographically prescribed phone (/f/). The results for lenition, a common diachronic process across the (monolingual and bilingual) Spanish speaking world, are in line with this process (and of course in interaction with language dominance). What is interesting is the fact that education was not a significant simple effect or a significant interaction with language dominance. That is, this would indicate that /f/ fortition, in this contact site between K’iche’ and Spanish, is governed by language dominance. In this sense, those who are most K’iche’-dominant, regardless of educational attainment, even if infrequently, favor [p] realizations more than other groups. That is, following Babel’s (2011) use of enregisterment (Agha 2005, 2007), this feature has become associated with those who are K’iche’-dominant. This notion is supported by Baird’s (2023a, 2023b) aforementioned perception studies. This demonstrates the need to examine both educational levels as well as language dominance in situations of language contact.

6 Conclusions

The present study increases our knowledge of outcomes of the phonemic conflict site that is the Spanish /f/ in contact with K’iche’ in Guatemalan Spanish. The findings of this study indicate that, although rare, both lenition ([h]) and fortition ([p]) occur among this population of K’iche’-Spanish bilinguals. Specifically, /f/ lenition is more likely to occur before /uV/ diphthongs and among speakers with lower levels of educational attainment, followed by more language dominance in K’iche’ whereas /f/ fortition is more likely after a nasal or a pause and among speakers that are more dominant in K’iche’. As such, these results indicate that the variants of /f/ cannot be completely attributed to contact with Mayan languages. Although several scholars have indicated that both lenition and fortition of /f/ are common among Mayan-Spanish bilinguals and are characteristics of “Mayan-accented” Spanish, the data presented here reveal that while that may be true of /f/ fortition, education is a more significant factor in /f/ lenition than language dominance, and lenition has even been reported among Guatemalan Spanish monolinguals (Utgård 2010). Furthermore, although this study demonstrates the scarcity of these specific characteristics of so-called Mayan-accented Spanish among a group of speakers that are highly dominant in a Mayan language, the previous perception studies indicate that these features remain indexical of the Maya and highly stigmatized in Guatemalan Spanish (Baird 2023a, 2023b). Thus, it is argued that in this community, /f/ lenition is due to sociolinguistic variation of a diachronic sound change (similar to other Spanish speaking communities) while /f/ fortition is a result of language contact and processes of enregisterment (Agha 2005; Babel 2011). In conclusion, sociolinguistic studies in bilingual communities should examine the role of education in promoting prescriptive phone-to-grapheme norms, language dominance, and the interaction between the two as language dominance, or bilingualism in general, does not inherently explain all variation in language contact.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the Maya of Nahualá, particularly to our research assistants, and to Leah Metzger, who assisted in the coding of the data. Sib’alaj maltyox chiwee iwonojel. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviews for their invaluable input. All errors remain our own.

Appendix I: Top: Spectral slice of the middle of the [f] token in fútbol where the sound pressure level (dB/Hz) continues past 3,000 Hz: Bottom: Spectral slice of the middle of the [h] token in fui where the sound pressure level (dB/Hz) drops before 3,000Hz. The dotted vertical line indicates 3,000 Hz in both spectral slices

Appendix II: Individual speaker frequency count

| Speaker | [f] | [h] | [p] | total/speaker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 | 3 | 0 | 38 |

| 2 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 20 |

| 3 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 17 |

| 4 | 33 | 2 | 0 | 35 |

| 5 | 39 | 5 | 0 | 34 |

| 6 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| 7 | 28 | 3 | 1 | 32 |

| 8 | 19 | 3 | 6 | 28 |

| 9 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 10 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 23 |

| 11 | 18 | 5 | 1 | 24 |

| 12 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 13 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| 14 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| 15 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 17 |

| 16 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| 17 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 56 |

| 18 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| 19 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 21 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| 22 | 29 | 3 | 0 | 32 |

| 23 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| 24 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 63 |

| 25 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| 26 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| 27 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| 28 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 29 | 44 | 0 | 7 | 51 |

| 30 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 48 |

| 31 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| 32 | 79 | 2 | 1 | 82 |

| 33 | 51 | 11 | 4 | 66 |

| 34 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 57 |

| 35 | 65 | 2 | 0 | 67 |

| 36 | 58 | 14 | 18 | 90 |

| 37 | 50 | 4 | 6 | 60 |

| 38 | 79 | 1 | 0 | 80 |

| 39 | 11 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| 40 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 19 |

Appendix III: Model comparison with LOO for [h]/[f] variation (Vehtari et al. 2017)

| Model | LOOIC | SE | ΔLOOIC | Δ SE | Population level effects (Factors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| brm1 | 273.2 | 22.8 | −5.4 | 1.9 | FollowingSound + Education4 + BLP_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm2 | 274.3 | 22.4 | −5.9 | 2.5 | FollowingSound + Education4 + (1|Speaker) |

| brm3 | 272.1 | 22.6 | −4.8 | 2.0 | FollowingSound + Education4*BLP_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm4 | 272.1 | 23.1 | −4.8 | 1.4 | FollowingSound + Education4 + BLP_scaled + Sex + (1|Speaker) |

| brm5 | 263.4 | 23.1 | −0.4 | 0.9 | FollowingSound*Education4 + Education4*BLP_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm6 | 272.6 | 22.8 | −5.0 | 1.9 | FollowingSound + Education4 + BLP_scaled + Age_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm7 | 262.8 | 23.1 | −0.2 | 0.9 | FollowingSound*Education4 + Education4*BLP_scaled + Age_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm8 | 263.5 | 23.7 | −0.5 | 0.2 | FollowingSound*Education4 + Education4*BLP_scaled + Sex + Age_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm9 | 262.5 | 23.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | FollowingSound*Education4 + Education4*BLP_scaled + Sex + (1|Speaker) |

| brm10 | 262.7 | 23.5 | −0.1 | 0.2 | FollowingSound*Education4 + Education4*BLP_scaled + BLP_scaled*Sex + (1|Speaker) |

Appendix IV: Model comparison with LOO for [p]/[f] variation (Vehtari et al. 2017)

| Model | LOOIC | SE | ΔLOOIC | Δ SE | Population level effects (Factors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| brm1 | 231.6 | 24.9 | −0.1 | 0.2 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + Stress + (1|Speaker) |

| brm2 | 231.7 | 24.9 | −0.2 | 0.4 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + Stress + Education4 + (1|Speaker) |

| brm3 | 234.2 | 24.6 | −1.4 | 1.7 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + Education + (1|Speaker) |

| brm4 | 233.9 | 24.5 | −1.3 | 1.7 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm5 | 237.4 | 24.2 | −3.0 | 2.0 | PreviousSound + BLP_scaled*Education + (1|Speaker) |

| brm6 | 231.3 | 24.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + Stress + Age_scaled + (1|Speaker) |

| brm7 | 233.3 | 24.5 | −1.0 | 1.7 | PreviousSound*BLP_scaled + BLP_scaled*Education + Stress + (1|Speaker) |

References

Agha, Asif. 2005. Voice, footing, enregisterment. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15(1). 38–59. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.38.Search in Google Scholar

Agha, Asif. 2007. Language and social relations. New York: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Agüero Chaves, Arturo. 1962. El español en Costa Rica. San José: Universidad de Costa Rica.Search in Google Scholar

Aleza Izquierdo, Milagros. 2010. Fonética y fonología. In Milagros Aleza Izquierdo & José María Enguita Utrilla (eds.), La lengua española en América: normas y usos actuales, 51–94. Valencia: Universitat de València.Search in Google Scholar

Alvar, Manuel. 1980. Encuestas fonéticas en el suroccidente de Guatemala. Lingüística Española Actual 2. 245–298.Search in Google Scholar

Alvar, Manuel. 2013. Paraguay. In Manuel Alvar (ed.), Manual de dialectología hispánica: el español de América, 196–208. Barcelona: Ariel.Search in Google Scholar

Ash, Sharon. 2013. Social class. In Jack K. Chambers & Natalie Schilling (eds.), The handbook of language variation and change, 2nd edn. 350–367. Somerset: Wiley.10.1002/9781118335598.ch16Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2015. Pre-nuclear peak alignment in the Spanish of Spanish-K’ichee’ (Mayan) bilinguals. In Erik W. Willis, Pedro Martín Butragueño & Esther Herrera Zendejas (eds.), Selected proceedings of the 6th Conference on Laboratory Approaches to Romance Phonology, 163–174. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2017. Prosodic transfer among Spanish-K’ichee’ Bilinguals. In Kate Bellamy, Michael W. Child, Paz González, Antje Muntendam & M. Carmen Parafita Couto (eds.), Multidisciplinary approaches to bilingualism in the Hispanic and Lusophone world, 147–172. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2018. Syntactic and prosodic contrastive focus marking in K’ichee’. International Journal of American Linguistics 84(3). 295–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/697585.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2019. Ciudadano maya 100%: uso y actitudes de la lengua entre los bilingües k’iche’-español. Hispania 102(3). 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpn.2019.0070.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2020. The vowel spaces of Spanish-K’ichee’ bilinguals. In Rajiv G. Rao (ed.), Spanish phonetics and phonology in contact: Studies from Africa, the Americas, and Spain, 63–81. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ihll.28.03baiSearch in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2021a. “Para mí, es indígena con traje típico”: Apocope as an indexical marker of indigeneity in Guatemalan Spanish. In Luis A. Ortiz & Eva-María Suárez Budenbender (eds.), Topics in Spanish linguistic perceptions, 223–239. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003054979-15Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2021b. Bilingual language dominance and contrastive focus marking: Gradient effects of K’ichee’ syntax on Spanish prosody. International Journal of Bilingualism 25(3). 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006920952855.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2023a. Social perceptions of /f/ fortition in Guatemalan Spanish. Spanish in Context 20(3). 599–625. https://doi.org/10.1075/sic.20011.bai.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. 2023b. Clothing, gender, and sociophonetic perceptions of Mayan-accented Spanish in Guatemala. Languages 8(3). 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030189.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. forthcoming a. Spanish in contact with Mayan languages in Guatemala. In Leonardo Cerno, Hans-Jörg Döhla, Miguel Gutiérrez Maté, Robert Hesselbach & Joachim Steffen (eds.), Contact varieties of Spanish and Spanish-lexified contact varieties. Volume II, Indigenized varieties of Spanish in multilingual scenarios. Berlin: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, Brandon. forthcoming b. Bilingualism and the assibilated /r/ in Guatemalan Spanish. In Mark Amengual & Amanda Dalola (eds.), Interdisciplinary approaches to Romance linguistics: In honor of Barbara E. Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Babel, Anna M. 2011. Why don’t all contact features act alike? Contact features and enregistered features. Journal of Language Contact 4. 56–91. https://doi.org/10.1163/187740911x558806.Search in Google Scholar

Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 1987. Markedness and salience in second language acquisition. Language Learning 37. 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1987.tb00577.x.Search in Google Scholar

Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken & Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An easy-to-use instrument to assess bilingualism. COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available at: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/.Search in Google Scholar

Boersma, Peter & David Weenink. 2019. Praat: A system for doing phonetics by computer. [Computer program]. Available at: http://www.praat.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Earl K. & Matthew C. Alba. 2017. The role of contextual frequency in the articulation of initial /f/ in Modern Spanish: The same effect as in the reduction of Latin /f/? Language Variation and Change 29. 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394517000059.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Esther L. & William D. Raymond. 2012. How discourse context shapes the lexicon: Explaining the distribution of Spanish f-/h words. Diachronica 29(2). 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.29.2.02bro.Search in Google Scholar

Bürkner, Paul-Christain. 2017. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software 80(1). 1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Calvo Shadid, Annette. 1996. Variation of the phoneme /f/ in two Costa Rican sociolects. Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica 22. 119–127. https://doi.org/10.15517/rfl.v22i1.21006.Search in Google Scholar

Canfield, D. Lincoln. 1981. Spanish pronunciation in the Americas. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cedergren, Henrieta J. 1973. The interplay of social and linguistic factors in Panama. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Chappell, Whitney. 2021. ‘En esta petsa, este anio’: The Spanish sound system in contact with Miskitu. In Manuel Díaz-Campos & Sandro Sessarego (eds.), Aspects of Latin American Spanish dialectology: In honor of Terrel A. Morgan, 181–203. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ihll.32.08chaSearch in Google Scholar

Docherty, Gerard & Norma Mendoza-Denton. 2012. Speaker-related variation- sociophonetic factors. In Abigail C. Cohn, Cecile Fougeron & Marie K. Huffman (eds.), The Oxford handbook of laboratory phonology, 44–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199575039.013.0004Search in Google Scholar

England, Nora & Brandon Baird. 2017. Phonology and phonetics. In Judith Aissen, Nora England & Roberto Zavala (eds.), The Mayan languages, 175–200. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315192345-7Search in Google Scholar

Flores Farfán, José Antonio. 2000. Por un programa de investigación del español indígena en México. In Julio Calvo Pérez (ed.), Teoría y práctica del contacto el español de América en el candelero, 145–158. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.31819/9783865278883-008Search in Google Scholar

Fonteyn, Lauren & Peter Petré. 2022. On the probability and direction of morphosyntactic lifespan change. Language Variation and Change 34(1). 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394522000011.Search in Google Scholar

Foulkes, Paul. 1997. Historical laboratory phonology – Investigating /p/> /f/> /h/ changes. Language and Speech 40. 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/002383099704000303.Search in Google Scholar

French, Brigittine. 2010. Maya ethnolinguistic identity: Violence, cultural rights, and modernity in highland Guatemala. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.Search in Google Scholar

French, Brigittine & Lolmay Pedro García Matzar. 2023. Memorias mayas del genocidio en Guatemala y el habla de los sobrevivientes kaqchikeles. Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital 18. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.22201/cimsur.18704115e.2023.v18.674.Search in Google Scholar

García Tesoro, Ana Isabel. 2008. Guatemala. In Azucena Palacios (ed.), El español en América: contactos lingüísticos en Hispanoamérica, 97–117. Barcelona: Ariel Letras.Search in Google Scholar

Greenlee, Mel. 1992. Perception and production of voiceless Spanish fricatives by Chicano children and adults. Language and Speech 35(1–2). 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/002383099203500214.Search in Google Scholar

Guirao, Migeulina & María A. García Jurado. 1990. Frequency of occurrence of phonemes in American Spanish. Revue Quebecoise de Linguistique 19(2). 135–149. https://doi.org/10.7202/602680ar.Search in Google Scholar

Herrera, Flavio. 1935. La tempestad. México D.F.: Unión tipográfica.Search in Google Scholar

Hothorn, Torsten, Kurt Hornik, Carolin Strobl & Achim Zeileis. 2020. Party: A laboratory for recursive partytioning, R package ver. 1.3-4. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/party/index.html.Search in Google Scholar

Hualde, José Ignacio. 2005. The sounds of Spanish. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. 2018. XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII Censo Nacional de Vivienda. https://www.censopoblacion.gt/ (accessed 20 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Kimball, Amelia E., Kailen Shantz, Christopher Eager & Joseph Roy. 2019. Confronting quasi-separation in logistic mixed effects for linguistic data: A Bayesian approach. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 26(3). 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1499457.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1966. The social stratification of English in New York City. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1990. The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change. Language Variation and Change 2(2). 205–254.10.1017/S0954394500000338Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 2001. Principles of linguistic change. Vol. 2: Social factors. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Ladefoged, Peter & Sandra Ferrari Disner. 2012. Vowels and consonants, 3rd edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Lapesa, Rafael. 2008. Historia de la lengua española. Madrid: Editorial Gredos.Search in Google Scholar

Lentzner, Karl. 1893. Observations on the Spanish language in Guatemala. Modern Language Notes 8(2). 41–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/2918323.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Yuhan. 2018. The role of educational factors in the development of lexical splits. Asian-Pacific Language Variation 4(1). 36–72. https://doi.org/10.1075/aplv.17004.lin.Search in Google Scholar

Lipski, John M. 1987. Breves notas sobre el español filipino. Anuario de Letras 25. 209–219.Search in Google Scholar

Lipski, John M. 2008. Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.10.1353/book13059Search in Google Scholar

Mallinson, Christine & Robin Dodsworth. 2009. Revisiting the need for new approaches to social class in variationist sociolinguistics. Sociolinguistic Studies 3(2). 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v3i2.253.Search in Google Scholar

Mazzaro, Natalia. 2011. Experimental approaches to sound variation: A Sociophonetic study of labial and velar fricatives and approximants in Argentine Spanish. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Mazzaro, Natalia. 2015. Explaining variation and change in Spanish peripheral fricatives. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 7(2). 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1515/shll-2014-1169.Search in Google Scholar

McKinnon, Sean. 2020a. Un análisis sociofonético de la aspiración de las oclusivas sordas en el español guatemalteco monolingüe y bilingüe (español-kaqchikel). Spanish in Context 17(1). 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1075/sic.00051.mck.Search in Google Scholar

McKinnon, Sean. 2020b. Quantifying propagation in language contact: A variationist analysis of stops in bilingual (Spanish-Kaqchikel Maya) Guatemalan Spanish. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

McKinnon, Sean. 2023. Phonological contrast maintenance and language contact: An examination of the Spanish rhotic system in a bilingual Guatemalan speech community. In Brandon Baird, Osmer Balam & M. Carmen Paratifa Couto (eds.), Linguistic advances in Central American Spanish, 41–71. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.10.1163/9789004679931_004Search in Google Scholar

Moren Sandoval, Antonio, Doroteo T. Toledo, Raúl de la Torre, Marta Garrote & José M. Girao. 2008. Developing a phonemic and syllabic frequency inventory for spontaneous spoken Castilian Spanish and their comparison to text-based inventories. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2008, 1097–1100.Search in Google Scholar

Moya, Ruth. 1981. Simbolismo y ritual en el Ecuador Andino/El quichua en el español de Quito. Otavalo, Ecuador: Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología.Search in Google Scholar

Nalborczyk, Ladislas, Cédric Batailler, Hélène Lœvenbruck, Anne Vilain & Paul-Christian Bürkner. 2019. An introduction to Bayesian multilevel models using brms: A case study of gender effects on vowel variability in standard Indonesian. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 62(5). 1225–1242. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_jslhr-s-18-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Parodi, Claudia. 2001. Contacto de dialectos y lenguas en el Nuevo Mundo: La vernacularización del español en América. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 149. 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2001.022.Search in Google Scholar

Penny, Ralph. 2000. Variation and Change in Spanish. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139164566Search in Google Scholar