Abstract

We empirically assess the impact of ride-hailing platforms on the incidence of drunk-driving fatal crashes and fatalities in Chile. Using a difference-in-differences approach, we study heterogeneous effects in fatalities by gender and role in the crash (driver or passenger). Our results suggest that the introduction of ride-hailing platforms has significantly reduced fatal crashes and fatalities, especially the number of female passengers’ fatalities and the number of male drivers’ fatalities at night. The former result may evidence that ride-hailing platforms like Uber can contribute to the mitigation of the mobility bias against women in the traditional transport sector.

Appendix A: Additional Tables and Figures

Uber entry dates in Chile.

| Municipality/region | Date | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Santiago (Region Metropolitana) | January 2014 (Black) and June 2015 (X and SUV) | https://www.economiaynegocios.cl/noticias/noticias.asp?id=176161 and printed version of Uber’s website in Chile available upon request |

| Valparaiso and Bio Bio (Concepcion) | July 2016 | https://www.fayerwayer.com/2016/06/uber-oficializa-servicio-para-regiones-de-valparaiso-y-biobio/ |

| Iquique, La Serena/Coquimbo, Temuco and Puerto Montt | January 2017 | https://www.elobservatodo.cl/noticia/sociedad/lo-esperabas-uber-anuncia-llegada-la-serena |

| Arica, Calama, Antofagasta, Copiapò, Ovalle, Rancagua, Valdivia, Osorno, Punta Arenas | April 2017 | https://www.latercera.com/noticia/arica-punta-arenas-uber-llega-10-nuevas-ciudades-chile/ |

Summary statistics of the first four dependent variables studied (nighttime).

| Obs. | Mean | St. dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of drunk-driving crashes | 12,017 | 1.53 | 3.50 | 0 | 52 |

| Number of drunk-driving fatal crashes | 12,017 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0 | 9 |

| Number of fatalities in drunk-driving crashes | 12,017 | 0.30 | 0.93 | 0 | 23 |

| Number of fatalities and injured people in drunk-driving crashes | 12,017 | 1.65 | 3.80 | 0 | 53 |

Summary statistics of the four gender-specific variables studied (nighttime).

| Obs. | Mean | St. dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of female driver fatalities | 12,017 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0 | 2 |

| Number of male driver fatalities | 12,017 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0 | 6 |

| Number of female passenger fatalities | 12,017 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0 | 6 |

| Number of male passenger fatalities | 12,017 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0 | 6 |

Characteristics of control and treatment municipalities according to the specification considered.

| Characteristic | Group | Municipalities considered by population size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ≥100,000 | ≥75,000 | ≥50,000 | ||

| # of municipalities | Control | 283 | 28 | 33 | 47 |

| Treatment | 52 | 30 | 39 | 42 | |

| Pop. in 2015 | Control | 37,666.9 | 196,384.7 | 180,792.4 | 144,352.5 |

| Treatment | 140,657.2 | 203,586.8 | 177,247.5 | 169,193.7 | |

| Female pop. in 2015 | Control | 18,883.3 | 99,636.9 | 91,800.2 | 73,277.5 |

| Treatment | 71,835.5 | 104,181.7 | 90,732.2 | 86,530.6 | |

| Male pop. in 2015 | Control | 18,783.6 | 96,747.8 | 88,992.1 | 71,075 |

| Treatment | 68,821.7 | 99,405.1 | 86,515.3 | 82,663.1 | |

| # of vehicles in 2015 | Control | 10,026.8 | 51,287.3 | 46,779.4 | 37,065.5 |

| Treatment | 36,657.9 | 49,004.2 | 45,073.0 | 43,140.6 | |

| # of automobiles in 2015 | Control | 5,764.8 | 33,042.3 | 29,935.7 | 23,410.6 |

| Treatment | 24,678.6 | 33,568.1 | 30,864.4 | 29,407.8 | |

| # of taxis and ‘collectivos’ in 2015 | Control | 305.7 | 1,334.0 | 1,238.6 | 977.3 |

| Treatment | 748.0 | 1,031.1 | 907.4 | 867.3 | |

| Population density in 2015 | Control | 447.9 | 569.2 | 549.7 | 447.9 |

| Treatment | 7,012.8 | 8,220.7 | 7,518.0 | 7,012.8 | |

| # of drunk-driving fatal crashes in 2014q4 | Control | 0.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| Treatment | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| # of fatalities in drunk-driving crashes in 2014q4 | Control | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Treatment | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| Vehicles per person in 2015 | Control | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Treatment | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.19 | |

| Taxis per person in 2015 | Control | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Treatment | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

Poisson model estimates of Uber’s entry on the number of drunk-driving crashes and the number of dead and injured people.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dead and injured people | Number of drunk-driving crashes | Number of dead and injured people at night | Number of drunk-driving crashes at night | |

| Uber Black | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.045 | 0.16 |

| (0.21) | (0.22) | (0.21) | (0.25) | |

| UberX | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.060 | 0.19 |

| (0.18) | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.19) | |

| N | 2,447 | 2,447 | 2,447 | 2,447 |

| Chi-squared | 222.5 | 408.8 | 287.6 | 442.6 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Deaths and all types of injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians are considered. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as control variables. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of Uber’s entry on the number of drunk-driving non-fatal crashes.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of drunk-driving non-fatal crashes | Number of drunk-driving non-fatal crashes at night | |

| Uber Black | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| (0.23) | (0.27) | |

| UberX | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| (0.19) | (0.20) | |

| N | 2,447 | 2,447 |

| Chi-squared | 422.0 | 437.9 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as control variables. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

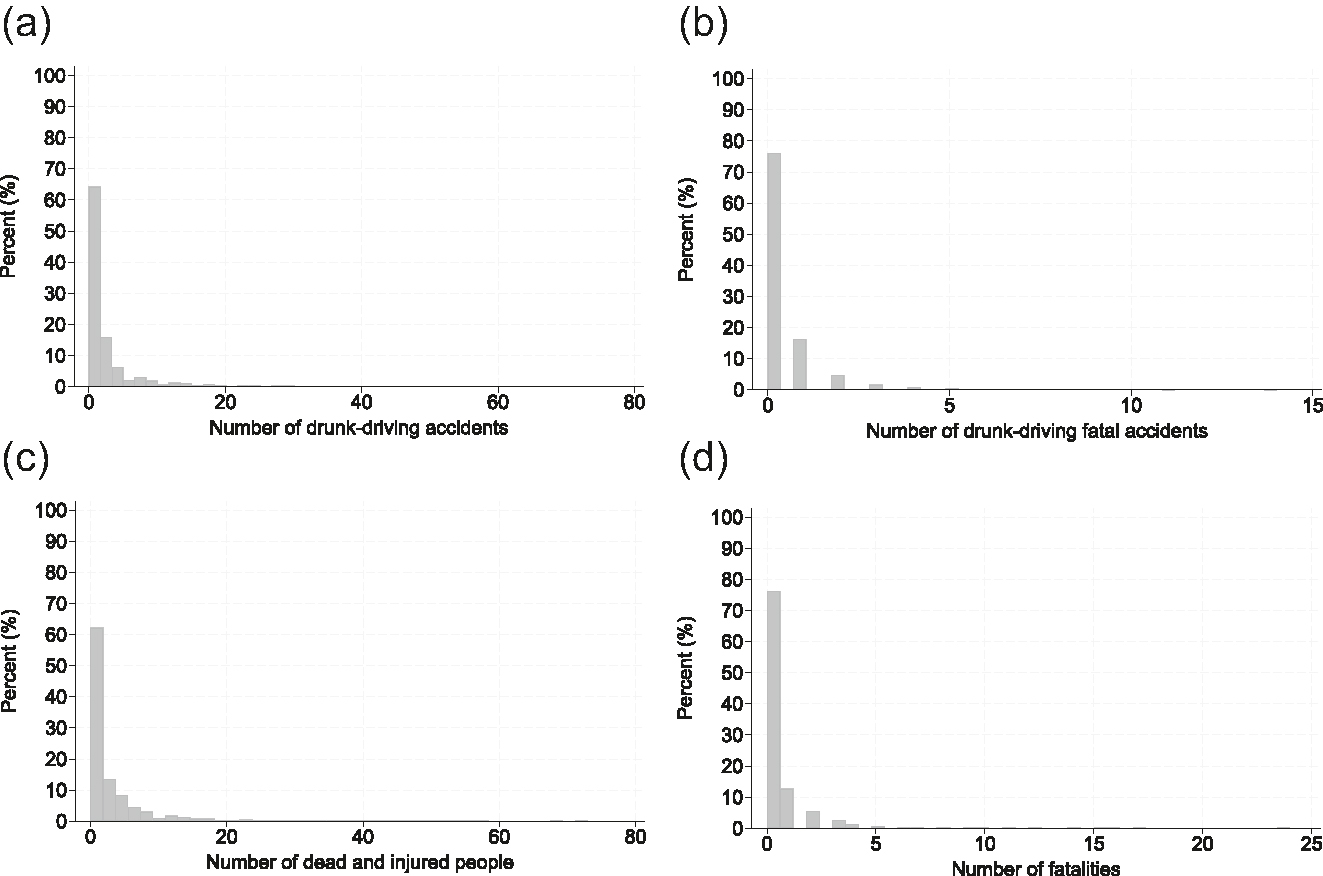

Distribution of the global outcomes studied.

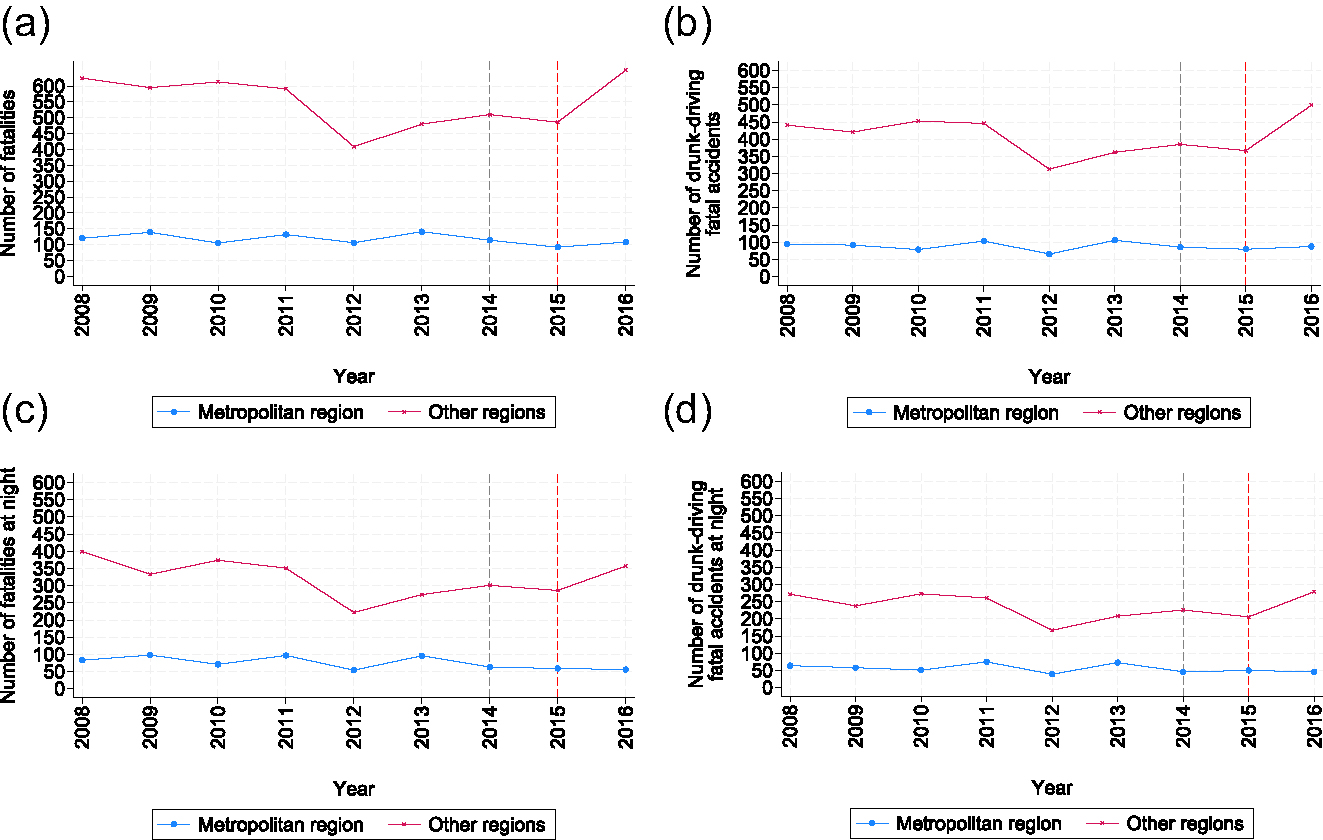

Evolution of drunk-driving fatalities and crashes (Metropolitan Region vs. other regions – 2008–2016). (a) Number of fatalities. (b) Number of fatal crashes. (c) Number of fatalities at night. (d) Number of fatal crashes at night.

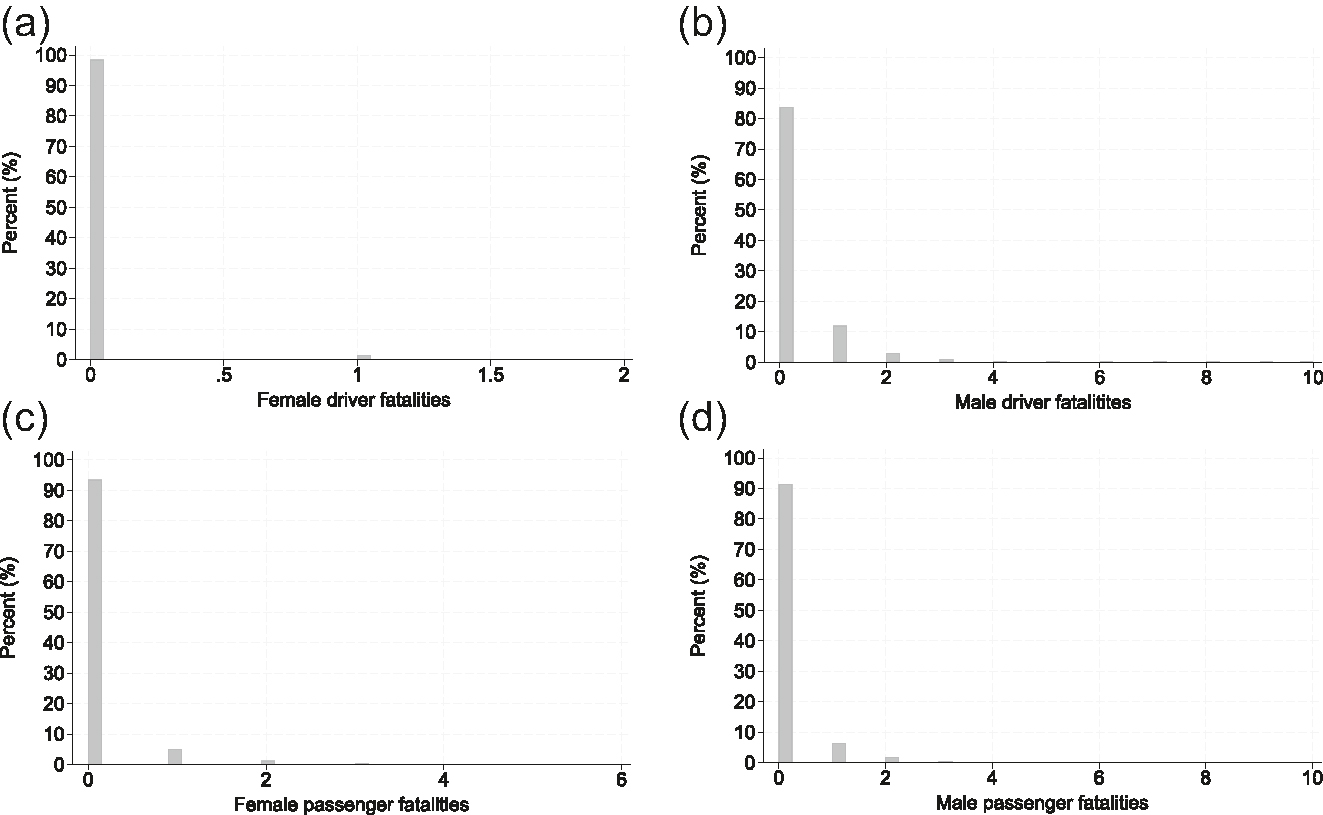

Distribution of the main gender-specific dependent variables studied.

Appendix B: Robustness Checks

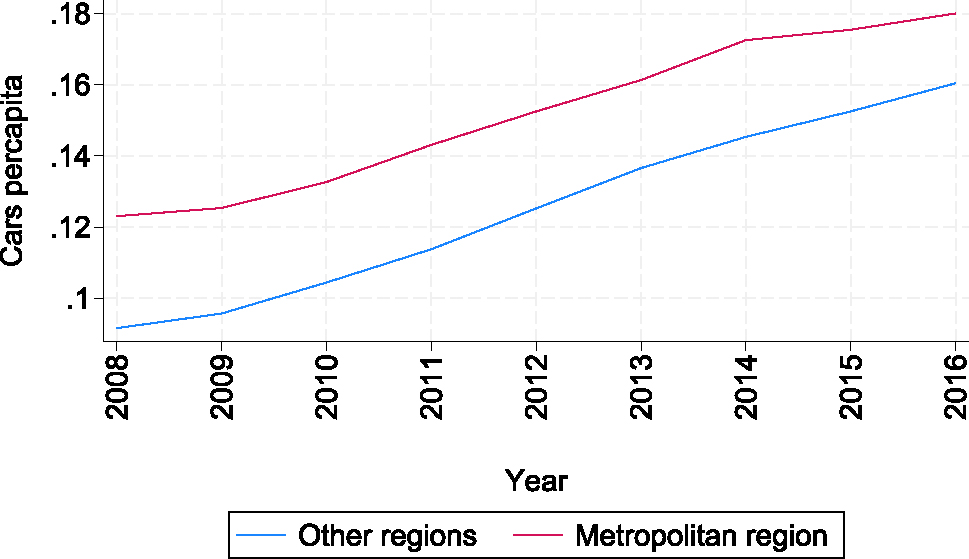

Evolution of the number of cars per-capita. Note: The number of cars does not consider off-road vehicles, commercial vans, minibuses, pick-ups, motorcycles, and other motorized and non-motorized vehicles. In addition, it does not consider public transportation vehicles and trucks. Source: INE.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on the number of drunk-driving crashes (total and only fatal) according to different specifications.

| Control groups | Control variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of drunk-driving fatal crashes | Number of drunk-driving fatal crashes at night | Number of drunk-driving crashes | Number of drunk-driving crashes at night | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.49** | −0.61*** | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Population and Population2 | −0.45** | −0.62** | 0.22 | 0.21 | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.36* | −0.46** | 0.28 | 0.30 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.41* | −0.57** | 0.23 | 0.24 | |

| Population density | −0.50** | −0.74*** | 0.27 | 0.26 | |

| Vehicle density | −0.64*** | −0.84*** | 0.35* | 0.35* | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.41** | −0.51** | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Population and Population2 | −0.37* | −0.50** | 0.17 | 0.14 | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.34* | −0.43** | 0.19 | 0.17 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.35* | −0.47** | 0.16 | 0.14 | |

| Population density | −0.40* | −0.57** | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| Vehicle density | −0.60*** | −0.74*** | 0.17 | 0.15 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatal crashes consider deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on the number of dead and injured people according to different specifications.

| Control groups | Control variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of fatalities | Number of fatalities at night | Number of dead and injured people | Number of dead and injured people at night | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.67*** | −0.90*** | 0.070 | 0.023 |

| Population and Population2 | −0.63*** | −0.91*** | 0.089 | 0.051 | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.53** | −0.72*** | 0.14 | 0.11 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.59** | −0.84*** | 0.061 | 0.034 | |

| Population density | −0.71*** | −1.07*** | 0.093 | 0.025 | |

| Vehicle density | −0.81*** | −1.13*** | 0.11 | 0.057 | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.54** | −0.67** | 0.076 | 0.035 |

| Population and Population2 | −0.51** | −0.66** | 0.10 | 0.070 | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.46** | −0.55** | 0.11 | 0.087 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.47** | −0.59** | 0.068 | 0.043 | |

| Population density | −0.54** | −0.74** | 0.11 | 0.060 | |

| Vehicle density | −0.74*** | −0.95*** | 0.055 | 0.020 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Estimates of UberX’s entry on the number of drunk-driving fatal crashes and fatalities.

| Estimation method | Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of fatalities in drunk-driving crashes | Number of drunk-driving fatal crashes | Number of fatalities in drunk-driving crashes at night | Number of drunk-driving fatal crashes at night | ||

| OLS | Counts | −0.63** | −0.45*** | −0.39* | −0.28** |

| Log(1 + counts) | −0.17** | −0.15** | −0.15** | −0.13** | |

| Poisson | Counts | −0.54** | −0.40* | −0.74** | −0.57** |

| Counts per 100,000 inhabitants | −0.48* | −0.40* | −0.56 | −0.45 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of car of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatal crashes consider deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects. Population Density is included as control variable except for specifications with count rates as dependent variable. The results of our main specification (count data) estimated with Poisson are included here for comparison. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on gender-specific outcome variables according to different specifications (drivers).

| Control groups | Control variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female driver fatalities | Female driver fatalities night | Male driver fatalities | Male driver fatalities night | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.51 | −0.62 | −0.50** | −0.72** |

| Population and Population2 | −0.36 | −0.58 | −0.45* | −0.69** | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.19 | −0.30 | −0.38 | −0.57* | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.18 | −0.50 | −0.43* | −0.65** | |

| Population density | −0.72 | −0.93 | −0.50** | −0.86*** | |

| Vehicle density | −1.26* | −1.12 | −0.55** | −0.84*** | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.65 | −0.89 | −0.33 | −0.52* |

| Population and Population2 | −0.57 | −0.90 | −0.29 | −0.48* | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.42 | −0.74 | −0.26 | −0.43* | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.52 | −1.01 | −0.28 | −0.48* | |

| Population density | −0.77 | −1.01 | −0.30 | −0.57* | |

| Vehicle density | −1.32** | −1.43 | −0.45** | −0.66** |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on gender-specific outcome variables according to different specifications (passengers).

| Control groups | Control variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female passenger fatalities | Female passenger fatalities night | Male passenger fatalities | Male passenger fatalities night | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −0.97** | −1.28** | −1.13** | −1.15* |

| Population and Population2 | −0.94** | −1.49** | −1.21** | −1.16* | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −0.87* | −1.21** | −1.09** | −0.94 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −1.08** | −1.67*** | −1.18** | −0.98 | |

| Population density | −1.21** | −1.80** | −1.10** | −1.25* | |

| Vehicle density | −1.23** | −1.71** | −1.09** | −1.33* | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | No controls | −1.12*** | −1.37** | −0.71 | −0.36 |

| Population and Population2 | −1.09** | −1.47** | −0.73 | −0.32 | |

| Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −1.03** | −1.35** | −0.74 | −0.22 | |

| Population and Population2 + Vehicle and Vehicle2 | −1.11** | −1.53*** | −0.74 | −0.21 | |

| Population density | −1.25*** | −1.67** | −0.63 | −0.35 | |

| Vehicle density | −1.50*** | −1.93*** | −0.72 | −0.56 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of Uber’s entry on gender and role-specific outcome variables (nighttime) – population density as exposure measure.

| Number of fatalities at night | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger | Driver | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Uber Black | 0.14 | −0.56 | 0.15 | −0.34 |

| (0.44) | (0.40) | (.) | (0.22) | |

| UberX | −1.39** | −0.37 | −0.91 | −0.54* |

| (0.61) | (0.60) | (.) | (0.27) | |

| N | 2,039 | 2,108 | 1,224 | 2,379 |

| Chi-squared | 189.8 | 149.6 | 8,755.3 | 199.5 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects as control variables. The exposure measure is Population Density. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of Uber’s entry on gender and role-specific outcome variables (nighttime) – population density as control variable and vehicles per capita as exposure measure.

| Number of fatalities at night | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger | Driver | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Uber Black | −0.040 | −0.55 | 0.14 | −0.37 |

| (0.51) | (0.42) | (0.70) | (0.24) | |

| UberX | −1.66** | −0.36 | −0.94 | −0.57* |

| (0.67) | (0.66) | (0.98) | (0.31) | |

| N | 2,039 | 2,108 | 1,224 | 2,379 |

| Chi-squared | 349.5 | 265.9 | 10,476.7 | 180.1 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatalities include deaths and severe injuries. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as control variable. The exposure measure is the number of vehicles per capita. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on gender specific outcomes according to different specifications (no control variables other than time and municipality fixed effects – different exposure measures).

| Control groups | Exposure measure | Fatalities | Fatalities at night | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger | Driver | Passenger | Driver | ||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | Population density | −0.98** | −1.14** | −0.50 | −0.51** | −1.30** | −1.16* | −0.63 | −0.73** |

| Population between 15 and 59 density | −0.98** | −1.13** | −0.50 | −0.51** | −1.29** | −1.16* | −0.62 | −0.72** | |

| Vehicles per capita | −0.96** | −1.09** | −0.45 | −0.48** | −1.26** | −1.12* | −0.50 | −0.69** | |

| Taxis per capita | −1.07** | −1.27** | −0.58 | −0.63*** | −1.39** | −1.29** | −0.68 | −0.85*** | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | Population density | −1.14*** | −0.72 | −0.66 | −0.35 | −1.39** | −0.37 | −0.91 | −0.54* |

| Population between 15 and 59 density | −1.14*** | −0.72 | −0.65 | −0.35 | −1.38** | −0.37 | −0.90 | −0.53* | |

| Vehicles per capita | −1.09** | −0.66 | −0.59 | −0.30 | −1.33** | −0.31 | −0.79 | −0.48* | |

| Taxis per capita | −1.21*** | −0.84* | −0.74 | −0.43** | −1.48** | −0.49 | −0.98 | −0.63** | |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatal crashes consider deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on gender specific outcomes according to different specifications (population density, time and municipality fixed effects as control variables – different exposure measures).

| Control groups | Exposure measure | Fatalities | Fatalities at night | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger | Driver | Passenger | Driver | ||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| Municipalities with 100,000 or more inhabitants | Population between 15 and 59 density | −1.20** | −1.08** | −0.69 | −0.48** | −1.79** | −1.23* | −0.91 | −0.84*** |

| Vehicles per capita | −1.23** | −1.11** | −0.72 | −0.52** | −1.81** | −1.27* | −0.87 | −0.87*** | |

| Taxis per capita | −1.30** | −1.24** | −0.77 | −0.63*** | −1.88** | −1.39** | −0.98 | −0.98*** | |

| Municipalities with 75,000 or more inhabitants | Population between 15 and 59 density | −1.26*** | −0.62 | −0.76 | −0.30 | −1.67** | −0.34 | −1.00 | −0.57* |

| Vehicles per capita | −1.26*** | −0.63 | −0.75 | −0.31 | −1.66** | −0.36 | −0.94 | −0.57* | |

| Taxis per capita | −1.34*** | −0.77 | −0.86 | −0.41* | −1.76** | −0.49 | −1.11 | −0.68** | |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatal crashes consider deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as controls. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Estimates of UberX’s entry on gender and role-specific fatalities.

| Estimation method | Dependent variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female passenger | Male passenger | Female driver | Male driver | ||

| OLS | Counts | −0.18* | −0.073 | −0.036 | −0.27** |

| Log(1 + counts) | −0.081* | −0.031 | −0.023 | −0.12* | |

| Poisson | Counts | −1.25*** | −0.63 | −0.77 | −0.30 |

| Counts per 100,000 inhabitants | −0.92* | −0.42 | −0.63 | −0.29 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of car of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Fatal crashes consider deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects and Municipality Fixed Effects. Population Density is included as control variable except for specifications with count rates as dependent variable. The results of our main specification (count data) estimated with Poisson are included here for comparison. Robust standard errors are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of UberX’s entry on the number of crashes and fatalities originated by different causes.

| Time frame | Cause of crash | Fatal crashes | Fatalities | Female driver | Female passenger | Male driver | Male passenger |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| All | Driver distraction | −0.086 | −0.11 | 0.28 | −0.12 | −0.30 | 0.36 |

| Driving without reasonable distance | 0.27 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.40 | −0.17 | |

| Lost control of vehicle | −0.13 | −0.087 | −0.58 | −0.77** | 0.078 | 0.17 | |

| Undetermined causes | 0.091 | 0.10 | 0.23 | −0.26 | 0.21 | −0.055 | |

| All causes except drunk-driving | −0.0100 | −0.017 | −0.026 | −0.048 | −0.022 | 0.11 | |

| All causes | −0.027 | −0.047 | −0.052 | −0.14 | −0.034 | 0.015 | |

| At night | Driver distraction | −0.049 | 0.037 | 0.058 | −0.025 | −0.41 | −0.058 |

| Driving without reasonable distance | 0.30 | 0.23 | 17.2 | 0.45 | 0.11 | −0.26 | |

| Lost control of vehicle | −0.46* | −0.35 | −0.10 | −1.81** | −0.32 | −0.039 | |

| Undetermined causes | 0.15 | 0.15 | −0.17 | −1.02 | 0.0058 | 0.47 | |

| All causes except drunk-driving | −0.095 | −0.11 | 0.24 | −0.38 | −0.23 | 0.15 | |

| All causes | −0.15 | −0.21* | 0.10 | −0.57** | −0.28* | 0.054 |

-

Note: Total fatalities include deaths and severe injuries of drivers, passengers and pedestrians. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications consider Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as control variables. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

Poisson model estimates of Uber’s entry on the number of people per car in drunk-driving crashes.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Average number of people per car in drunk-driving crashes | Average number of people per car in drunk-driving fatal crashes | |

| Uber Black | 0.059 | 0.084 |

| (0.081) | (0.21) | |

| Uber X | 0.098 | −0.16 |

| (0.10) | (0.20) | |

| N | 2,447 | 2,447 |

| Chi-squared | 91.8 | 88.2 |

-

Note: The model only considers crashes where the cause was “alcohol in the driver”, there was at least one private driver (at least 18 years old) and the type of car of at least one of the vehicles was an automobile, a van or a jeep. Treatment and control municipalities considered are those with 75,000 inhabitants or more in 2015. All specifications include Time Fixed Effects, Municipality Fixed Effects and Population Density as control variables. Robust standard errors, shown in parentheses, are clustered by municipality. Symbols *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

References

Allen, H., L. Pereyra, L. Sagaris, and G. Cárdenas. 2017. “Ella Se Mueve Segura. She Moves Safely. A Study on Women’s Personal Security and Public Transport in Three Latin American Cities.” fia Foundation Research Series, Paper, 10.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, M. L., and L. W. Davis. 2021. “Uber and Alcohol-Related Traffic Fatalities (No. w29071).” National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w29071Search in Google Scholar

Autor, D. 2003. “Outsourcing at Will: The Contribution of Unjust Dismissal Doctrine to the Growth of Employment Sourcing.” Journal of Labor Economics 21: 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1086/344122.Search in Google Scholar

Badger, E. 2014. “Are Uber and Lyft Responsible for Reducing Duis?” Washington Post, Washington, DC, July 10, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

Barrios, J. M., Y. Hochberg, and H. Yi. 2020. “The Cost of Convenience: Ridehailing and Traffic Fatalities (No. w26783).” National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w26783Search in Google Scholar

Berger, T., C. Chen, and C. B. Frey. 2018. “Drivers of Disruption? Estimating the Uber Effect.” European Economic Review 110: 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

Bian, B. 2018. “Search Frictions, Network Effects and Spatial Competition: Taxis Versus Uber.” Working Paper. Pennsylvania State University Department of Economics. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/17361.Search in Google Scholar

Brazil, Noli, and David S. Kirk. 2016. “Uber and Metropolitan Traffic Fatalities in the United States.” American Journal of Epidemiology 184 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww062.Search in Google Scholar

Brazil, N., and D. Kirk. 2020. “Ridehailing and Alcohol-Involved Traffic Fatalities in the United States: The Average and Heterogeneous Association of Uber.” PLoS One 15 (9): e0238744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238744.Search in Google Scholar

Castillo, M., R. Petrie, M. Torero, and L. Vesterlund. 2013. “Gender Differences in Bargaining Outcomes: A Field Experiment on Discrimination.” Journal of Public Economics 99: 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

Comisión Nacional de Productividad y Fundación Chile. 2018. “Conocimiento y uso de las plataformas digitales de transporte.” Technical Report.Search in Google Scholar

Dills, A. K., and S. E. Mulholland. 2018. “Ride-Sharing, Fatal Crashes, and Crime.” Southern Economic Journal 84: 965–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12255.Search in Google Scholar

Duchène, C. 2011. “Gender and Transport. International Transport Forum.” Discussion Paper 2011 – 11.Search in Google Scholar

European Institute for Gender Equality. 2016. “Gender in Transport.” Technical Report.Search in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 2006. “Women and Transport,” IP/B/TRAN/ST/2005_008. Technical Report.Search in Google Scholar

Granada, I., A. M. Urban, A. Monje Silva, P. Ortiz, D. Pérez, L. Montes, et al.. 2016. “The Relationship Between Gender and Transport.” Inter-American Development Bank. Technical Report.10.18235/0006303Search in Google Scholar

Greenwood, B. N., and S. Wattal. 2017. “Show me the Way to Go Home: An Empirical Investigation of Ride-Sharing and Alcohol Related Motor Vehicle Fatalities.” MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 41 (1): 163–87. https://doi.org/10.25300/misq/2017/41.1.08.Search in Google Scholar

Haldun Anil, B., and S. Fisher Ellison. 2022. “Regulatory Distortion: Evidence from Uber’s Entry Decisions in the US.” Mimeo. https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Uber_Project%20%281%29.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, J. D., C. Palsson, and J. Price. 2018. “Is Uber a Substitute or Complement for Public Transit?” Journal of Urban Economics 108: 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

Harris, C. R., M. Jenkins, and D. Glaser. 2006. “Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why do Women Take Fewer Risks than Men?” Judgment and Decision Making 1 (1): 48. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1930297500000346.Search in Google Scholar

Henao, A., and W. E. Marshall. 2019. “The Impact of Ride-Hailing on Vehicle Miles Traveled.” Transportation 46: 2173–94, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-018-9923-2.Search in Google Scholar

Jackson, C. K., and E. G. Owens. 2011. “One for the Road: Public Transportation, Alcohol Consumption, and Intoxicated Driving.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (1–2): 106–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Z., Y. Hong, and Z. Zhang. 2016. “Do Ride-Sharing Services Affect Traffic Congestion? An Empirical Study of Uber Entry.” SSRN Electronic Journal 2002: 1–29.10.2139/ssrn.2838043Search in Google Scholar

Liu, M., E. Brynjolfsson, and J. Dowlatabadi. 2018. “Do Digital Platforms Reduce Moral Hazard? The Case of Uber and Taxis (No. w25015).” National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w25015Search in Google Scholar

Martin-Buck, F. 2017. “Driving Safety: An Empirical Analysis of Ridesharing’s Impact on Drunk Driving and Alcohol-Related Crime.” University of Texas at Austin Working Paper.Search in Google Scholar

Morrison, C. N., S. F. Jacoby, B. Dong, M. K. Delgado, and D. J. Wiebe. 2017. “Ridesharing and Motor Vehicle Crashes in 4 US Cities: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis.” American Journal of Epidemiology 187 (2): 224–32, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx233.Search in Google Scholar

Ng, W. and A. Acker. 2018. “Understanding Urban Travel Behavior by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies.” International Transport Forum. Discussion Paper 2018 – 01.Search in Google Scholar

Peck, J. L. 2017. “New York City Drunk Driving After Uber.” Working Papers 13. City University of New York Graduate Center, Ph.D. Program in Economics.Search in Google Scholar

Peters, D. 2013. “Gender and Sustainable Urban Mobility. Thematic Study Prepared for Global Report on Human Settlements 2013.” https://civitas.eu/sites/default/files/unhabitat_gender_surbanmobilitlity_0.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, D. C., and D. Sandler. 2015. “Does Public Transit Spread Crime? Evidence from Temporary Rail Station Closures.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 52: 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2015.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

Quinones, L. M. 2020. “Sexual Harassment in Public Transport in Bogotá.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 139: 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.06.018.Search in Google Scholar

Rayle, L., S. Shaheen, N. Chan, D. Dai, and R. Cervero. 2014. App-Based, On-Demand Ride Services: Comparing Taxi and Ridesourcing Trips and User Characteristics in San Francisco University of California Transportation Center (uctc). University of California, Berkeley, United States.Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, J., R. Hodgson, and P. Dolan. 2011. ““It’s Driving Her Mad”: Gender Differences in the Effects of Commuting on Psychological Health.” Journal of Health Economics 30 (5): 1064–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.07.006.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, H. L. 1984. Deterring the Drinking Driver: Legal Policy and Social Control, Vol. 1982. Lexington: Lexington Books.Search in Google Scholar

Shapiro, M. 2018. “Density of Demand and the Benefit of Uber.” https://files.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/200255159.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Silverstein, S. 2014. “These Animated Charts Tell you Everything About Uber Prices in 21 Cities.” Business Insider 16. http://www.businessinsider.fr/us/uber-vs-taxi-pricing-by-city-2014-10.Search in Google Scholar

Teltser, K., C. Lennon, and J. Burgdorf. 2021. “Do Ridesharing Services Increase Alcohol Consumption?” Journal of Health Economics 77: 102451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102451.Search in Google Scholar

Thurman, Q., S. Jackson, and J. Zhao. 1993. “Drunk-Driving Research and Innovation: A Factorial Survey Study of Decisions to Drink and Drive.” Social Science Research 22 (3): 245–64. https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1993.1012.Search in Google Scholar

Tirachini, A., and A. Gomez-Lobo. 2020. “Does Ride-Hailing Increase or Decrease Vehicle Kilometers Traveled (VKT)? A Simulation Approach for Santiago de Chile.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 14 (3): 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1539146.Search in Google Scholar

Turrisi, R., and J. Jaccard. 1992. “Cognitive and Attitudinal Factors in the Analysis of Alternatives to Drunk Driving.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53 (5): 405–14. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1992.53.405.Search in Google Scholar

Uteng, Tanu Priya. 2012. “Gender and Mobility in the Developing World.” World Bank Publications - Reports 9111. The World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a9b17dbd-1764-569c-b8c5-f8fb8522d5d3/content.Search in Google Scholar

Vanier, C., and H. D’arbois de Jubainville. 2018. “Le sentiment d’insécurité dans les transports en commun: situations anxiogènes et stratégies d’évitement.” Grand Angle n°46 INHESJ/ONDRP, January 2018.Search in Google Scholar

Vergara-Cobos, E. 2018. Learning from Disruption: The Taxicab Market Case. Mimeo.Search in Google Scholar

Wooldridge, J. M. 1999. “Distribution-Free Estimation of Some Nonlinear Panel Data Models.” Journal of Econometrics 90 (1): 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(98)00033-5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston