Abstract

Owing to their remarkable characteristics, refractory molybdenum nitride (MoN x )-based compounds have been deployed in a wide range of strategic industrial applications. This review reports the electronic and structural properties that render MoN x materials as potent catalytic surfaces for numerous chemical reactions and surveys the syntheses, procedures, and catalytic applications in pertinent industries such as the petroleum industry. In particular, hydrogenation, hydrodesulfurization, and hydrodeoxygenation are essential processes in the refinement of oil segments and their conversions into commodity fuels and platform chemicals. N-vacant sites over a catalyst’s surface are a significant driver of diverse chemical phenomena. Studies on various reaction routes have emphasized that the transfer of adsorbed hydrogen atoms from the N-vacant sites reduces the activation barriers for bond breaking at key structural linkages. Density functional theory has recently provided an atomic-level understanding of Mo–N systems as active ingredients in hydrotreating processes. These Mo–N systems are potentially extendible to the hydrogenation of more complex molecules, most notably, oxygenated aromatic compounds.

1 Introduction

Transition metal nitrides (TMNs) are refractory ceramic compounds exhibiting various fascinating properties, including a high melting, remarkable oxidation resistance against wear and corrosion, chemical inertness, and excellent electrical conductivity (Oyama 1996; Toth 2014). These extraordinary properties primarily originate from the unique electronic and geometrical structures of TMNs. Their geometries comprise a mixture of covalent (metal and nonmetal), metallic (metal–metal), and ionic (metal and nonmetal charged) bonds (Calais 1977). The strong covalent bonding between TM and N atoms has been exploited in a wide range of applications, such as high-temperature coatings that resist hostile conditions (elevated temperatures and pressures, catalysts, and solar selective surfaces) (Alexander and Hargreaves 2010; Giordano and Antonietti 2011; Ham and Lee 2009; Lengauer 2000; Levy and Boudart 1973; Mitterer et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2003). Moreover, the nitrogen introduced into metal–metal bonds increases the bond distance from that of the parent metal in TMNs, providing them a unique crystal structure that has received considerable interest. Furthermore, the exclusive electronic properties of the resultant bonds result in high catalytic activities of TMTs, which is similar to those of noble metals such as Pt, Pd, and Ru.

The synthesis methods of nitride-based materials generally require high temperatures and long reaction times (Gregory 1999). The energy-intensive synthesis routes of nitride-containing compounds primarily stem from the high energy of dissociating the triple bond of nitrogen molecules (945 vs. 498 kJ mol−1 required for dissociating the double bonds of oxygen molecules) (Luo 2002). This high energy prevents nitrogen atoms from developing ionic bonds with electropositive elements. Overall, thermodynamic phenomena may explain the scarcity of nitrides and their greater propensity to form unique geometries than oxides or carbides (Gregory 1999). Molybdenum nitrides (MoN) are arguably the most discussed group in TMNs with diverse applications in catalysts and hard coating materials. Number of comprehensive reviews focus on the structures, thermodynamics, bonding nature, synthetics methods, catalysis, and characterizations of nitride-based compounds (Chen 1996; Lengauer 2005; Wang et al. 1995). This review covers two main aspects of Molybdenum nitrides -based materials:

The chemistry of molybdenum nitrides. This perspective covers structural properties, synthesis methods, and phase stability diagrams.

Catalytic mechanisms involving molybdenum nitrides in various heterogeneous reactions. This perspective focuses on the governing reaction networks, operational conditions, products, and chemical conversions.

2 Structural properties of TMNs in general

The geometric and electronic aspects of TMNs have been extensively investigated and reported (Chen 1996; Johansson 1995; Oyama 1996). As is well known, nitrides of Groups III–XII (d-block elements) exhibit an intermediate transition state between metallic and interstitial nitrides as non-metal atoms diffuse into the metal lattice (Toth 2014). Row 1 metals (Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Ni, and Co) are termed intermediate compounds, whereas Rows 2 and 3 metals, including (Zr, Nb, and Mo) and (Hf, Ta, W, and Re), respectively, from the so-called interstitial compounds. The carbides are structurally distinct from oxides. In oxides (carboides), the anions (cations) are the larger atoms and the cations (anions) occupy the interstitial sites. However, in TMNs, the nitrogen atoms are randomly distributed in half of the octahedral interstices, whereas the metal atoms occupy the lattice sites of face-centered cubic (fcc), hexagonal close packed (hcp), or simple hexagonal structures (Chen 1996). These sites may also be occupied by carbon- or oxygen-forming carbonitride and oxynitride, respectively. Furthermore, Hägg (1931) suggested that when the radius ratio of the nonmetal to metal atoms is less than 0.59, the interstitial compound group typically possesses a B1–NaCl structure (Goldschmid 2013). Although TMNs assume simple crystal structures, they typically differ from those of their corresponding parent metals. For instance, the stable version of metallic Mo crystallizes in the body-centered cubic (bcc) phase; however, its analogous stable nitride (Mo2N) exhibits an fcc-like structure as depicted in Supplementary Figure S1. These structural modifications between the parent metal and the nitrogen-containing transition metal are ascribed to electronic factors (Oyama 1996).

The predominant stoichiometries in the early transition metal nitrides are TMN and TM2N (where TM denotes transition metal). However, later transition metals mainly adopt the TM3N stoichiometry because the atomic size decreases across the groups. Consequently, the lattices of metals with a high group number cannot host interstitial nitrogen atoms in their close-packed (cp) or hexagonal close-packed (hcp) arrangements (Lee and Ham 2003; Sproul 1986).

3 Electronic properties

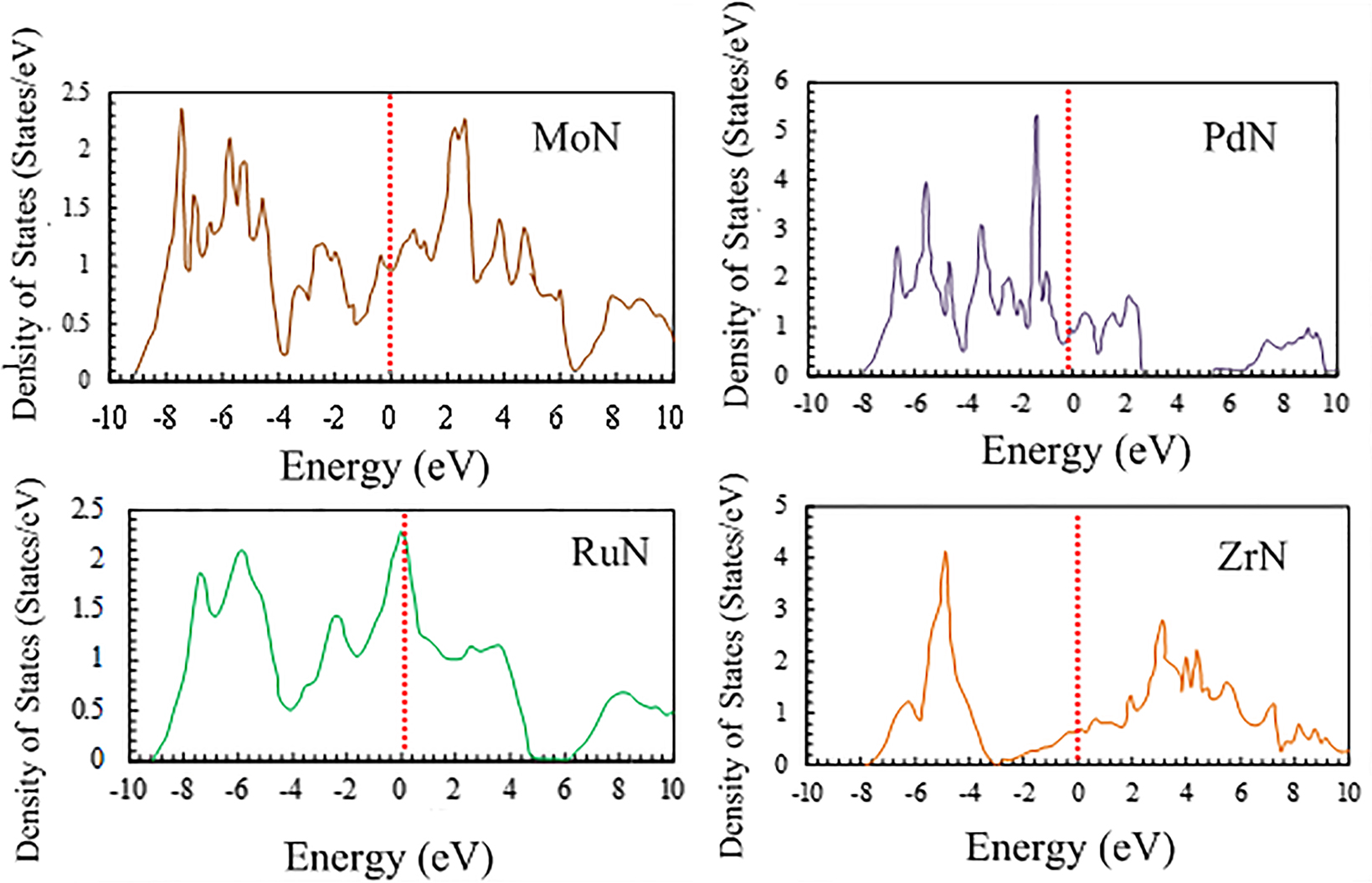

The number of valence electrons largely determines the distinctive properties of an element or compound (Lee and Ham 2003). In terms of the shape and ordering of the bands, the density of states (DOS) of TMNs follow the trend of their corresponding transition metals (Gogotsi and Andrievski 2012). In transition metals, the d-band starts to fill from Ru and Os to Pd and Pt. Furthermore, the catalytic properties of Group IV–VI TMNs are similar to those of Group VIII–X transition metals because both forms possess a similar d-band. As revealed by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS), the electronic structures of refractory TMNs strongly correlate with their properties (Greczynski et al. 2017; Höchst et al. 1982). (Brewer 1968) reported the thermodynamic properties of several crystalline transition metals based on the Engel-Brewer theories (Hume-Rothery 1968). Using the theory that combines the electronic and crystal structures of the bcc and hcp configurations with the spectroscopic data of gaseous transition metal atoms, it is suggested that the structure of a metal or substitutional alloy firmly depends on the sp electrons. In particular, the number of sp valence electrons per atom (e/a) determines the shape of the unit cell. Ratios of 1–1.5, 1.7–2.1, and 2.5–3 correspond to the bcc, hcp and fcc configurations, respectively. The valence electron concentration reportedly provides a detailed description of the mechanical properties of Group IV–XII nitrides, carbides, and carbonitrides with a salt-rock structure (Koutná et al. 2018). First-principles investigations of the electronic properties of bulk TMNs in Groups V and VI were first reported (Papaconstantopoulos et al. 1985). The energy separations in the DOSs of TMNs increase from the 3d to 5d nitrides (i.e., CrN→MoN→WN). Furthermore, the electronic DOSs in the valence and core states of TMNs are related to the covalency degree of their chemical bonding. Along the same line of enquiry, the low stability of the cubic MoN phase has been linked to the increased charge transfer from Mo-d electrons to N-p. The number of N-p electrons correlates with the stoichiometric ratio N/Mo (Lévy et al. 1999). Figure 1 displays the theoretically predicted DOSs of selected metal mononitrides. The absence of a band gap in the DOS curves indicates a metallic character (Zhao et al. 2010).

Theoretically predicted DOS of selected transition metal mononitrides. The Fermi energy level (denoted by the vertical dotted line) was arbitrarily set to zero (Zhao et al. 2010), reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

4 Mechanical properties

The hardness of a material reflects the material’s resistance to different types of distortions (such as knocking or scratching). The hardness values of TMN compounds largely depend on their M/N ratios and reduce with increasing nitrogen contents. Hones et al. (2003) observed that fcc γ-Mo2N has lower hardness than that of over-stoichiometric phases. The strength of the metal–nitrogen bonds in TMNs also contributes to their relative hardness. A decrease in hardness (i.e., elastic modulus) is mainly attributable to the diminishing covalent character of the bonding Ns. Under low nitrogen loads, the electrons in the low-lying bonding bands are only partially occupied, and the hardness increases. When the nitrogen contents increase, the low-lying bonding bands become fully occupied, the covalent bonds are broken, and the ionic bonds are weakened; accordingly, the hardness diminishes (Papaconstantopoulos et al. 1985).

Klimashin et al. (2016) thoroughly analysed the effect of N content and their vacancies on the mechanical properties of Mo–N coatings. Among all synthesized MoN x configurations, the γ-MoN0.53 displays the highest hardness of ∼33 GPa. The valance electron concentration for this particular coating amounts to 8.6. This value reflects very well other VEC values for corresponding NaCl-like structures with the maximum hardness in other transition metal nitrides such as NbN x and TaN x (Jhi et al. 1999). In this regard, we propose that DFT-based mechanical properties can now be extrapolated to real scenarios of operational temperature and pressure through the quasi-harmonic approximation (QHA) approach. Thus, it will be insightful to re-assess the impact of nitrogen content on the stability of MoN x coatings at elevated temperatures in light with published study (Klimashin et al. 2016). We have utilized the combined DFT-QHA approach to acquire volume-dependent thermo-elastic properties of two of the most investigated MoNx phases, namely, c-MoN and h-MoN (Jaf et al. 2016). Pertinent properties were obtained their melting point and a pressure of 12 GPa. We have established that the two structures of molybdenum nitride assume minor harmonic effects. This is affirmed by a negligible variation of considered thermo-mechanical properties with the increase of pressure and temperature. Similarly, Abdelkader et al. (2020) computed basic mechanical properties (including the elastic constant matrix) for the two tetragonal β-Mo2N and cubic γ-Mo2N phases pointing out to the mechanically stability of the two nitrides. However, the former was predicted to incur higher thermodynamic stability.

Yu et al. (2016) argued that the recently synthesized R3m phase of MoN2 at a modest pressure of 3.5 GPa to be thermodynamically and mechanically unstable. They examined the stable phase of MoN2 by deploying the USPEX code. Two pernitride MoN2 structures, namely hexagonal P63/mmc and tetragonal P4/mbm, were deemed to be stable. The evaluated hardness values for hexagonal P63/mmc and tetragonal P4/mbm geometries amount to 22.3 and 32 GPa, respectively. These noticeably high values render these structures as potential candidates in the synthesis of hard coating materials. Moreover, the predicted elastic constants of MoN2 P63/mmc phase were extraordinarily high (C33 value of 952 GPa) close to that of diamond (C33 = 1079 GPa).

5 Molybdenum nitride phases

Nitrides of molybdenum possess several unique properties, including high hardness and superconducting temperature (Sangiovanni et al. 2011; Soignard et al. 2003). These properties have been exploited in diverse and niche fields. Among the applications of molybdenum nitrides are hard coatings for high-temperature machinery (Khojier et al. 2013; Suszko et al. 2005), diffusion barriers in microelectronic devices (Lee and Park 1996; Li et al. 2015), and enrichment of the tribological properties of hard coatings by forming the so-called Magnéli phase (Gassner et al. 2006). Technological applications of molybdenum nitrides greatly depend on their phases, which are themselves dictated by their nitrogen loads. Supplementary Table S1 enlists geometrical features of the MoN x phases.

5.1 γ-Mo2N1 ± x phase

The gamma phase (γ-Mo2N) possesses an fcc structure with the

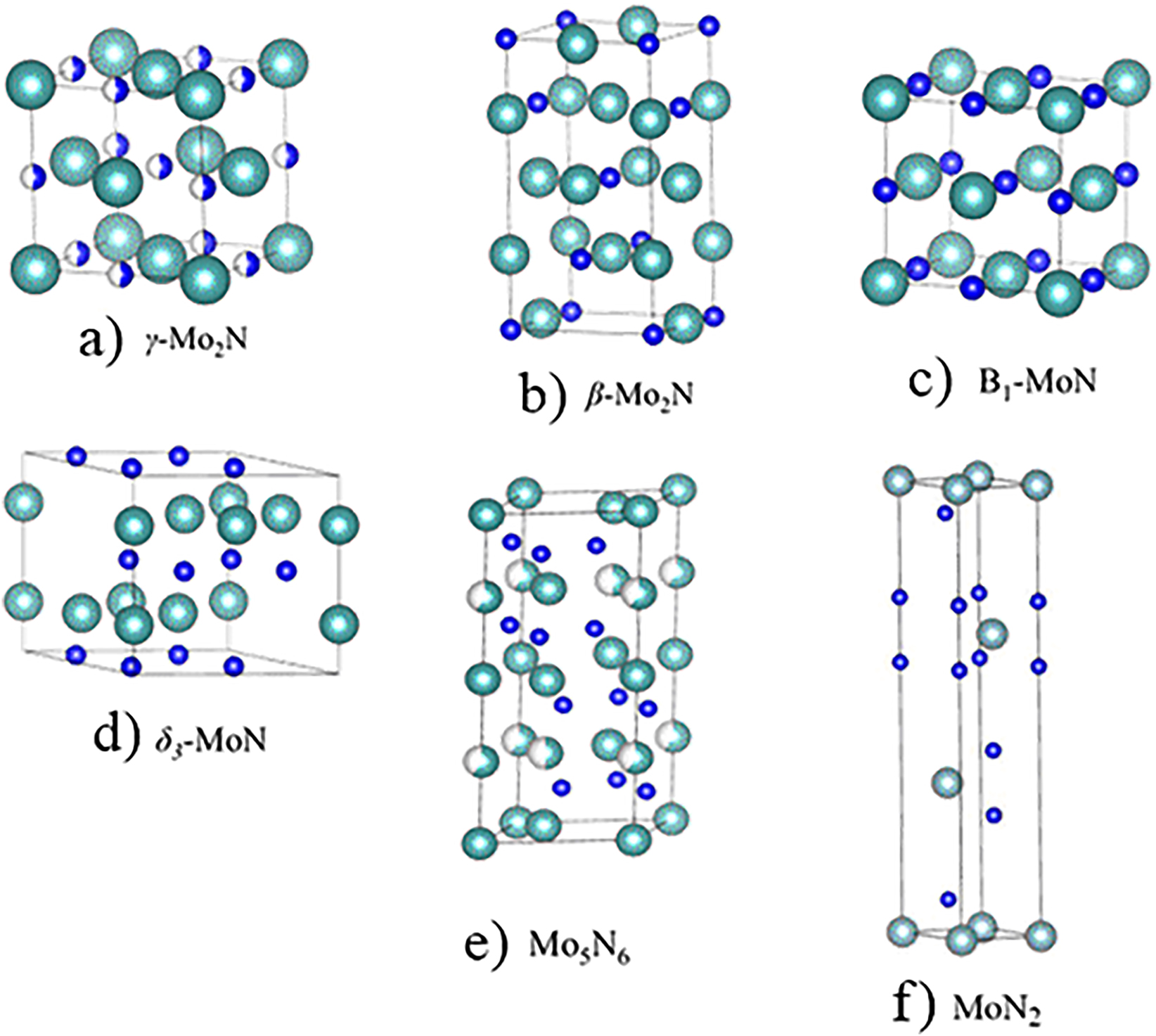

Phases of molybdenum nitrides (light blue spheres correspond to Mo atoms and blue spheres denote N atoms).

5.2 β-Mo2N phase

The β-Mo2N phase is an ordered tetragonal structure with mechanical stability at low temperatures. This structure is often considered as a tetragonal adjustment of the cubic γ-Mo2N phase with a doubled lattice constant c (forming the I41/amd space group) (Karam and Ward 1970). The γ-Mo2N phase transforms to β-Mo2N at high temperatures. The synthesis routes and characterization of β-Mo2N have been rarely reported (Ettmayer 1970). Inumaru et al. (2005) synthesized a crystalline phase of β-Mo2N by pulsed laser deposition of molybdenum metal. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed a composition of Mo2N0.85. The unit cell structure of this tetragonal phase is displayed in Figure 2b.

5.3 Metastable cubic B1-MoN

Although the stoichiometric cubic B1-MoN phase is thermodynamically unstable, it can be stabilized by carefully controlling the nitrogen concentration during synthesis (Jauberteau et al. 2015). The nitrogen amounts in MoN x films is regulated from Mo1N0.5 to Mo1N1 by varying the growth rate (i.e., the N/Mo flux ratio) during the film deposition process. In a separate work, they synthesized an epitaxial B1-MoN x (0.98 < x < 1.03) on α-Al2O3 by a thermal treatment below 650 °C (Inumaru et al. 2006b). A number of XRD studies have reported very similar lattice structures of the NaCl-Mo2N phase with a = 4.16 Å (Shen 2003) and a = 4.151 Å (Kawashima et al. 2007). The stoichiometry of the B 1 -MoN phase lies between those of MoN0.5 and MoN1.0. Any increase in nitrogen content is expected to enlarge the lattice parameter. The concentration of nitrogen vacancies primarily relies on the synthesis parameters, most notably, on the availability of nitrogen cations during sputtering (Inumaru et al. 2006a; Lin and Lai 2014) and the temperature treatments (Shen 2003). Figure 2c shows a unit cell with a NaCl-type structure.

In a comprehensive combined DFT-experimental investigation, Klimashin et al. (2016) presented relative stability diagrams for a wide spectrum of MoN structures. These structures were systematically generated using the special quasi-random structure (SQS) method. Based on computed formation energies, it was found that the WC-type δ1-MoN x and NiAs-type δ 2 -MoN x structures display similar formation energies for x resides in the vicinity of 0.85. Beyond this nitrogen content, the latter phase is energetically more preferred. In the cubic-structured NaCl-phases, configurations with N content close to 3:3 stoichiometry entails higher stability. DFT-based stability phase diagram by Klimashin et al. (2016) conveys two key remarks, First of all, the non-equilibrium technique of physical vapour deposition (PVD) can be fine-tuned to produce several metastable MoNx structures. Second of all, the change in the nitrogen chemical potential drives a significant shift in the ordering stability of the MoN x phases. However, it must be noted that the study of (Klimashin et al. 2016) utilized pure DFT functional whereas the presence of d orbitals in Mo atoms calls for the implementation of a more robust DFT + U methodology.

5.4 δ-MoN phase

The hexagonal δ-MoN configuration is arranged as metal layers with an ABAB staking sequence and a T

c

of ∼13.8 K (Wang et al. 2015a). Nonetheless, the positions of the N atoms cannot be unequivocally pinpointed, as the crystals are of poor quality (Bezinge et al. 1987). This phase has been fabricated by reduction of MoO2 with NH4Cl at high temperature (1773 K) under high NH3 pressure (2 MPa) (Zhao and Range 2000). Bull et al. (2004) synthesized hexagonal δ1-MoN via high temperature ammonolysis of MoCl5. The produced crystals exhibited the P63mc space group with lattice constants of a = 2.87 Å and c = 2.81 Å. High-pressure ammonolysis affords the highly N-ordered hexagonal phase δ3-MoN with nearly doubled lattice parameters (i.e., a = 5.73 Å and c = 5.61 Å). Ganin et al. (2006) fabricated several stoichiometric phases of hexagonal molybdenum nitrides by the plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition method and ammonolysis of MoCl5 and MoS2. The synthesised nitrides were called δ1-MoN (WC type, P

5.5 Mo5N6 phase

The Mo5N6 phase displays unequal layers of nitrogen prisms and octahedral-type arrangements along the c axis Figure 2e (Marchand et al. 1999). The nitrogen atoms form an AABB-type arrangement, analogous to the sulfur atoms in MoS2. The molybdenum atoms saturate the trigonal prismatic sites and partially fill the octahedral sites. The Mo5N6 structure mimics the configurations of the WC- and NiAs-type building blocks, with partially filled Mo sites (Ganin et al. 2006).

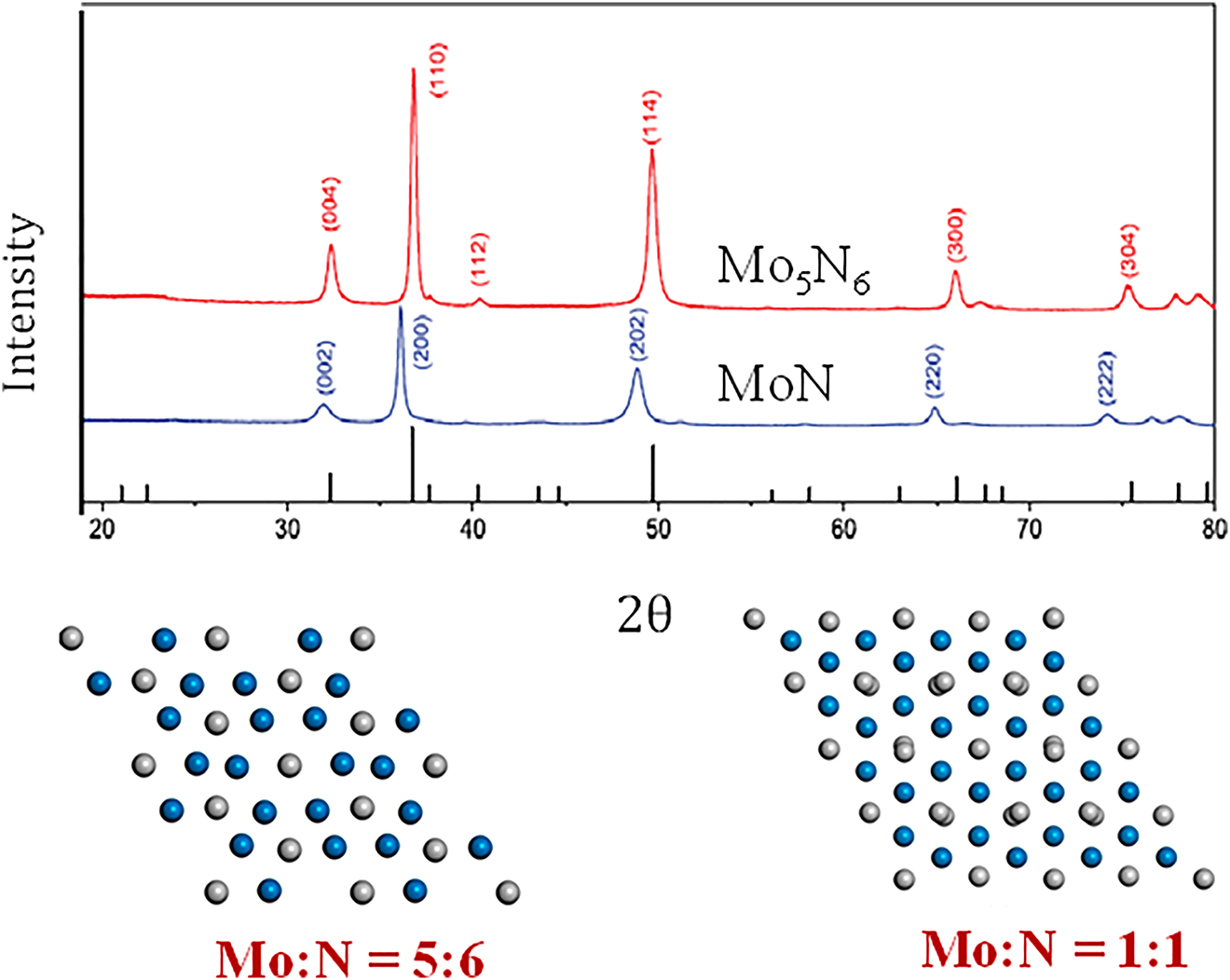

5.6 Nitrogen-rich molybdenum

Figure 2f presents the geometrical unit cell of 3R-MoN2. This cell features both a MoS2-type structure and a rhombohedral R3m arrangement. Wang et al. (2015b) produced a nitrogen-rich molybdenum nitride via the solid-state ion-exchange reaction under moderate pressure (3.5 GPa). Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of different crystal structures of MoN and Mo5N6. XRD patterns of the synthesized 2D nitrogen-rich Mo5N6 nanosheets demonstrate various peak position that deviates from MoN. Suggesting that the extra (20%) nitrogen-incorporation significantly alters the crystal structure of conventional MoN (Jin et al. 2018).

XRD patterns of Mo–M phases (Jin et al. 2018), reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society, 2018.

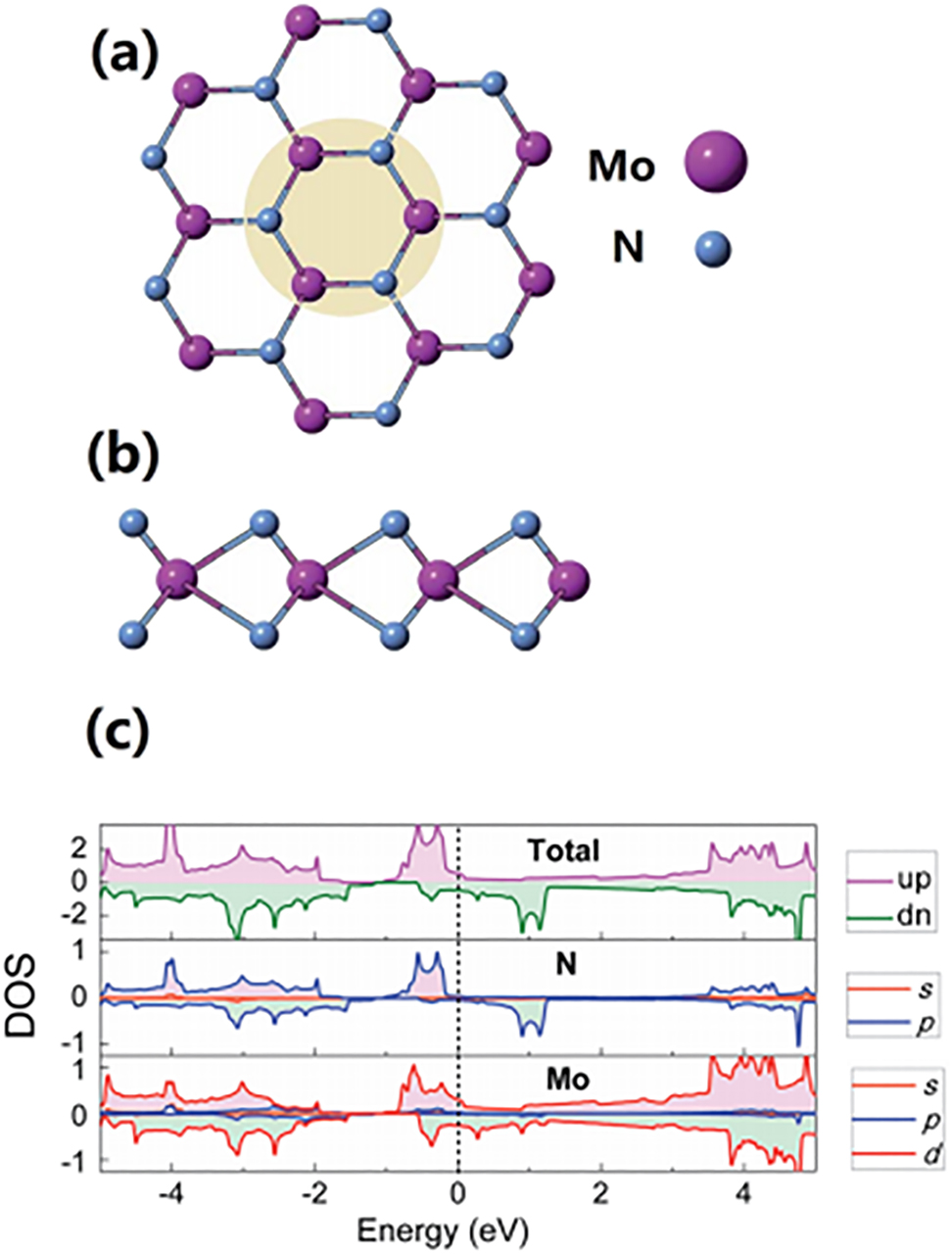

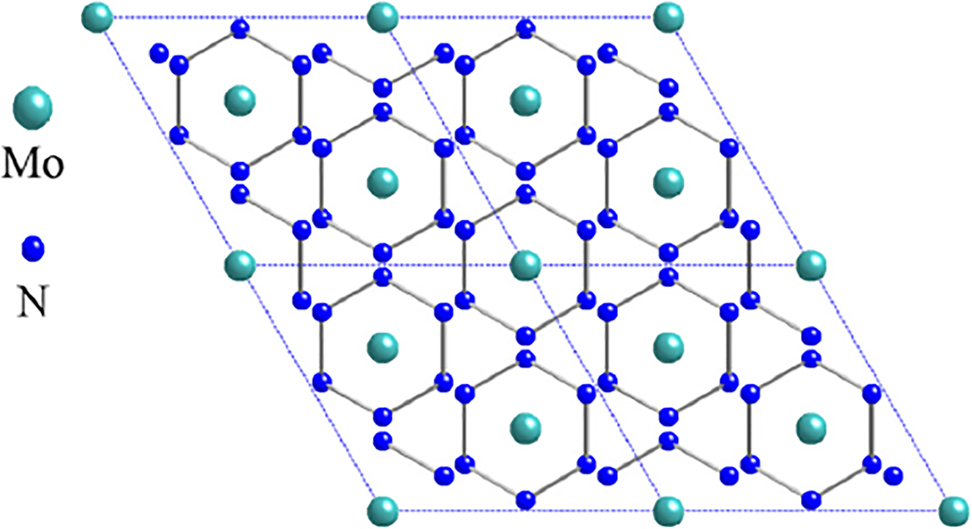

Figure 4 depicts the structure and the DOS of the N-rich MoN2 phase following a DFT investigation (Zhang et al. 2016). The MoN2 assumes a hexagonal structure, with Mo and N atoms residing at two sites of a honeycomb lattice Figure 4a and b. Monolayers of MoN2 comprises of atomic sheets stacked along the sequence N–Mo–N. As Figure 4c portrays, the MoN2 exhibits a metallic character. We envisage that this profound catalytic activity of MoN2 partially stems from this behaviour.

Top (a) and side (b) views of the MoN2 phase and (c) its DOS curves (Zhang et al. 2016), reproduced with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Similarly, Yu et al. (2016) explored the ground-state properties of bulk MoN2 by DFT calculations. They proposed that the Mo atoms are sandwiched between N atoms. They also concluded (surprisingly) that the MoS2-type MoN2 structure proposed by (Wang et al. 2015b) is thermodynamically and mechanically unstable. This conclusion was supported by the negative elastic stiffness coefficients (C44), multiple imaginary phonon frequencies, and positive enthalpy of formation. Using first-principles calculations, Wang and Ding (2016) inspected the structural stabilities and electronic properties of two-dimensional (2D) layered MoS2-like molybdenum- and tungsten-dinitride nanosheets. They reported that contrary to the corresponding disulphide nanosheets, dinitride nanosheets of the MoN2 phase contain durable soft modes that render them dynamically, thermally, and mechanically unstable. They also postulated that surface hydrogenation could effectively eliminate these soft modes. Hydrogenated MoN2H2 sheets as displayed in Supplementary Figure S2 are structurally stable and exhibit excellent electronic properties. A 2D transition metal dinitride sheet named tetra-MoN2 possesses a significantly more stable ground-state geometry than the H–MoN2 phase, along with a strain tenability that adjusts to the applied stress. Tetra-MoN2 is a semiconductor with a band gap of only 1.41 eV (Zhang et al. 2017).

6 Phase stability diagram of the Mo–N system

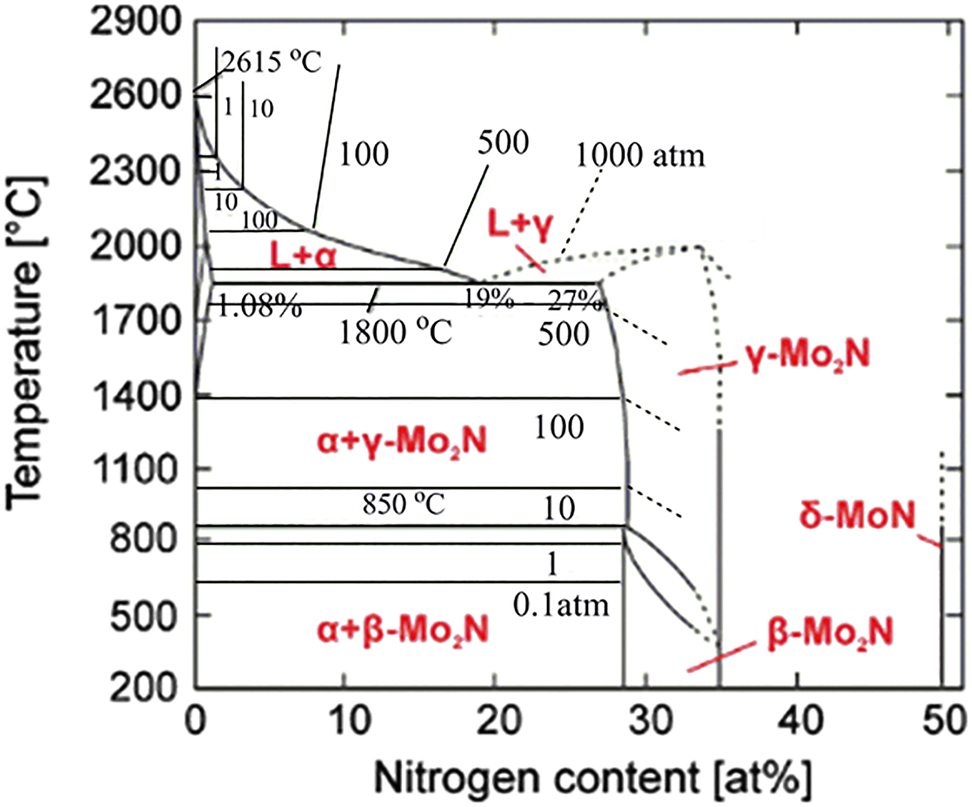

Figure 5 represents a phase diagram of the Mo–N system proposed Jehn and Ettmayer (1978). In the α-phase, molybdenum hosts a nitrogen load ranging from 0 to 1.08 atomic weight (at.%). At temperatures below 1000 °C, the atomic-nitrogen concentration in α-Mo reaches 1.08 at.% at most, which is negligible. At 1860 °C and an equilibrium pressure of 670 atm, Mo can dissolve 1.08 at.% N (Jehn and Ettmayer 1978). In the 673–1123 K range, the cubic γ-Mo2N phase is interchangeable with the tetragonal β-Mo2N phase (Jauberteau et al. 2015). Gamma-phase Mo–N (γ-Mo2N) is homogenous over a wide range of relative N ratios. This phase undergoes an ordering conversion between 400 and 850 °C (Lengauer 2000). The γ-Mo2N phase appears at high temperatures as a defective B1-NaCl structure in which half of the nitrogen lattice positions are vacant sites. The nitrogen composition of this structure is around 27–35 at %. As discussed earlier, the B1-MoN phase can be produced by gradual filling of the vacant nitrogen sites in the defective γ-Mo2N phase. This non-equilibrium phase readily transforms to the thermodynamically more stable hexagonal phase. Note that the thermodynamically unstable B1-MoN phase is absent in the stability diagram displayed in Figure 5, because it structurally rearranges into the hexagonal δ-MoN phase (Sanjinés et al. 1996). Saito and Asada (1987) concluded the same transformation sequence (γ-Mo2N → B1-type MoN → δ-MoN) according to XRD spectra of the different phases. After implanting a nitrogen ion dose of 1 × 1017 ions/cm2 into Mo thin films, they reported that the peaks corresponding to the bcc-Mo (110) and (200) directions were accompanied by new diffraction peaks belonging to the γ-Mo2N phase. Under the maximum dose of 16 × 1017 ions/cm2, the reflection peaks of the bcc-Mo crystal tended to vanish.

T–P phase stability diagram of the Mo–N system (Jehn and Ettmayer 1978), reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

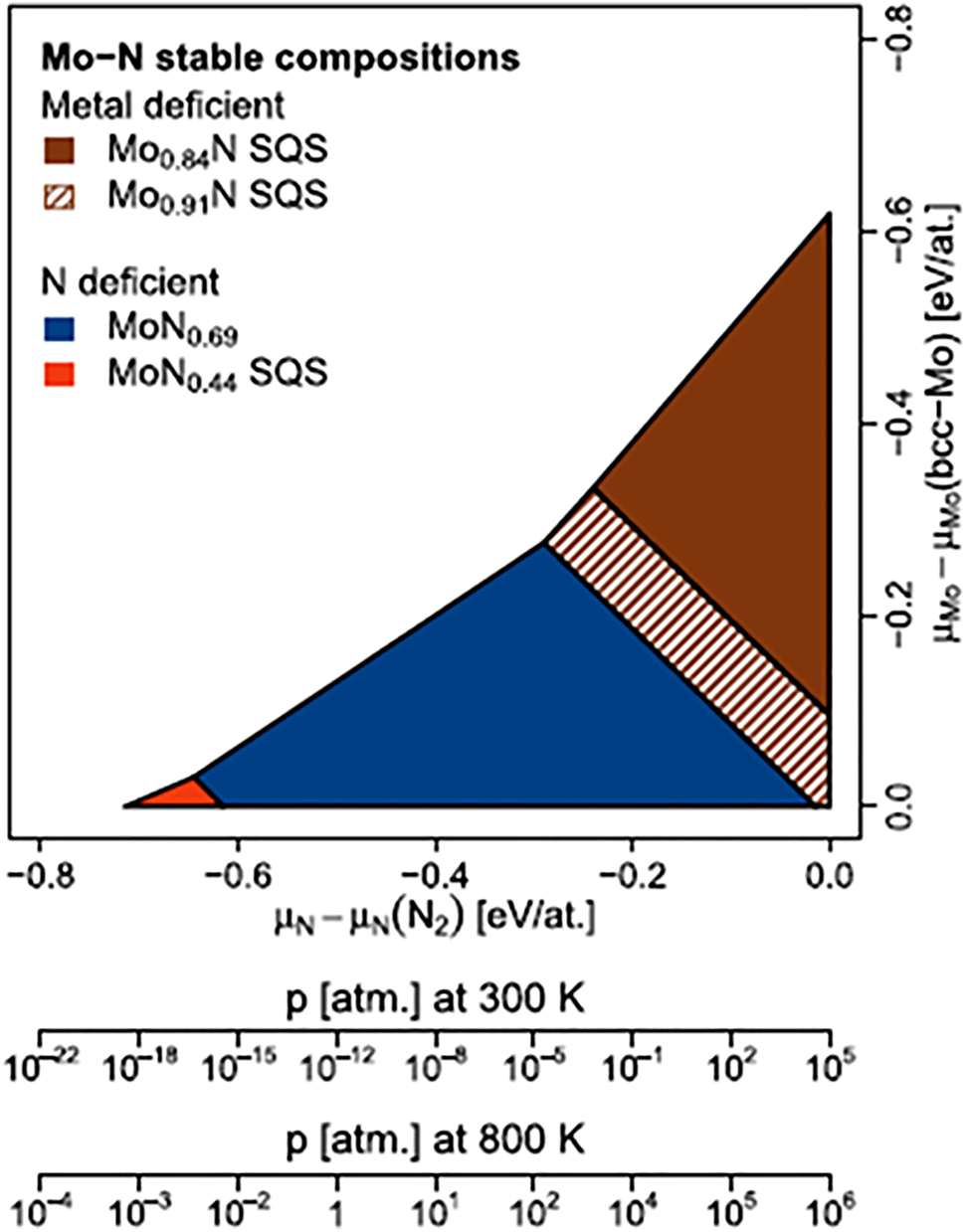

A more detail understanding pertinent to the effect of point defects in the stability ordering of MoN x phases was firstly presented by Koutná et al. (2016) for cubic MoN and subsequently extended to include other structural configurations (Klimashin et al. 2016). Figure 6 depicts DFT-based phase diagram of Mo–N system (Koutná et al. 2016). The cubic Mo–N phase diagram corresponding to the stable compositions as a function of the N and Mo chemical potentials and the most stable structures corresponds to the structures with the lowest energy of formation E f . As for the cubic phase, it was found that phases of cubic MoN with either vacant Mo or N sites exhibit similar formation energies for a vacancy concentration lower than 15%. The constructed phase diagram by Koutná et al. (2016) predicts the formation of four defect configurations ranging from fully disordered to fully ordered configurations (namely Mo0.91N, MoN0.69, MoN0.44, and Mo0.84N). Herein, we propose that 3D stability diagram could be constructed for oxynitride phases analogously following the methodology pioneered by Koutná et al. (2016) and Klimashin et al. (2016). The underlying aim is to assess the combined effect of variation in N/O chemical potential and the potential emergence of metastable MoN x O y structures.

DFT- based phase diagram of Mo–N system as a function of the N and Mo chemical potentials (Koutná et al. 2018). The article was published as open access under the CC BY 3.0 license.

The dominant phase is affected not only by the T–P conditions but also by the amount of nitrogen in the system. Klimashin et al. (2016) theoretically and experimentally assessed the effect of nitrogen content and nitrogen vacancies on the geometries and mechanical properties of Mo–N thin films. The relative proportion of N-vacant sites alters the Mo–N bonding types and hence the relative thermodynamic hardness.

The elemental analysis, and hence the load of N vacant sites, were determined by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Klimashin et al. 2016). The MoN x phases were often examined through analysis of synchrotron X-ray data (Cao et al. 2015). High resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were also obtained for molybdenum nitrides with vacant sites (Guy et al. 2020) and display rows of hollow N sites. XPS spectra estimated the distribution of Mo oxidation states, and thus, highlighting the presence of N vacant sites (Choi et al. 1992). In typical XPS analysis (McGee and Thompson 2020), the ratio of N/Mo is attained on the basis decomposition of the Mo 3p3/2 and N 1s peaks. Along the same line of enquiry, the O/Mo ratios is computed based on the Mo 3d5/2 and O 1s peak areas. Neutron diffraction also is supremely suitable to investigate the N atom positions and site occupancy due to the large scattering length for nitrogen comparing to the molybdenum atoms implying that the bound coherent scattering cross sections of Mo and N are 5.7 and 11.01 b, correspondingly (Bull et al. 2006).

(Balasubramanian et al. 2017) coupled DFT calculations with the universal structure predictor evolutionary xtallography (USPEX) algorithm, an evolutionary phase-search algorithm that estimates the thermodynamic plausibility of Mo–N phases and their stoichiometries. The DFT–USPEX computations predicted eight thermodynamically stable molybdenum nitride phases with N-rich and N-deficient configurations: hexagonal δ-Mo3N2, cubic γ-Mo11N8, cubic γ-Mo14N11, orthorhombic ε-Mo4N3, monoclinic σ-MoN, σ-Mo2N3, tetragonal β-Mo3N, and hexagonal δ-MoN2. From the thermodynamic stability diagram shown in Figure 5, we note that stoichiometric and near-stoichiometric phases of N-atom ratios and occupancies adopt hexagonal-type structures, whereas nonstoichiometric phases adopt different forms (B1-MoN, gamma γ-Mo2N, tetragonal β-Mo2N).

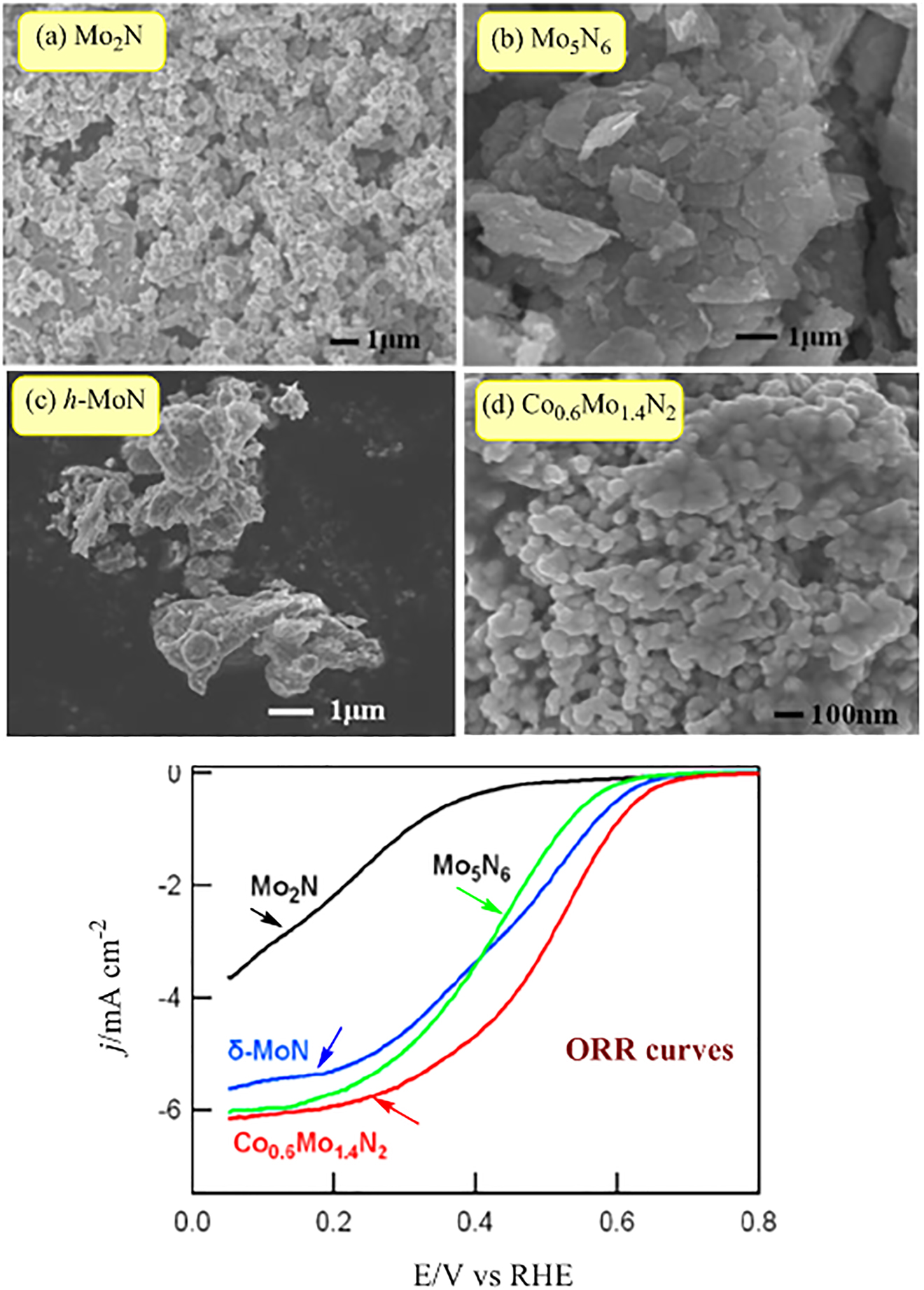

7 Morphologies of molybdenum nitride

Choi and Kumta (2011) fabricated nanocrystalline MoN x powders (x = 0.77–1.32) at low temperature (≥600 °C) via NH3 ammonolysis and nitridation of MoCl5. The powders were intended for use as super capacitors. The γ-Mo2N crystallites yielded the highest specific capacitance (111 F/g d at a scan rate of 2 mV/s). Combining experiments with DFT calculations. Xie et al. (2014) examined the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity of 1.3 nm-thick hexagonal-phase MoN nanosheets synthesised by liquid exfoliation of bulk MoN materials. In the DFT calculations, the active sites of the atomically thin MoN nanosheets were identified as surface Mo atoms that catalyze the conversion of protons to hydrogen. By virtue of their rich surface-active sites and high conductivity, the MoN nanosheets delivered a high current density of 38.5 mA cm2 at η = 300 mV. Joshi et al. (2017) synthesized micrometer-sized 2D nanosheets of hexagonal δ-MoN via a two-step process. The first step forms the 2D nanosheets from a MoO3 precursor, and the second step transforms the oxide phase to the respective nitride through a reductive annealing process. Reduction of the oxide phase is accompanied by a phase transformation of the metal oxide to nitride, sulphide, or carbide in an NH3, H2S, or CH4 environment, respectively. The formation mechanism of molybdenum nitride nanosheets was proposed by (Sun et al. 2018). They synthesized several phases of molybdenum nitride nanosheets (Mo5N6, δ-MoN, and γ-Mo2N) by incorporating MoS2 with nitrogen in a nanosheet configuration. Supplementary Figure S3 schematizes the possible reduction reactions of MoS2 and NH3. The occurring reaction is very sensitive to the working temperature. At 750 °C, Mo5N6 is generated directly with no immediate product. At 820 °C, Mo5N6 is synthesized by a one-step process and decomposes to δ-MoN when the MoS2 is spent. At 950 °C, the only detected product is the δ-MoN phase. By gradual conversion of MoS2, MoN decomposes first to γ-Mo2N and later to a merging γ-Mo2N plus β-Mo2N phase. After complete consumption of MoS2 at 1020 °C, the phase evolves as δ-MoN→ γ-Mo2N→ β-Mo2N→ Mo. At a higher temperature (1120 °C), only the β-Mo2N intermediate eventually transforms into Mo.

8 Predictive modelling of the ground-state properties of the Mo–N system

Motivated by the growing need for reliable and representative data that can be utilized for shortlisting materials and tailoring their attributes toward a category of desired applications, many researchers have applied state-of-the-art computational methods to gain atomic-level insights into the potential applications and properties of Mo–N based materials. Powerful high-performance computational facilities have enabled the accurate modelling of materials. Researchers can now confirm the thermo-mechanical properties, lattice parameters, adsorption energies, XRD patterns, reaction rate constants, and turnover frequencies in models, most commonly by first principles calculations in the DFT framework. This section outlines the recent advances in DFT predictions of the bulk and surface properties of molybdenum nitrides. Stevens et al. (2006) investigated whether DFT models can accurately calculate the equilibrium bond lengths, dipole moments, and harmonic vibrational frequencies of Group VI (Cr, Mo, W) transition metals containing diatomic molecules. Using flexible basis sets, they examined a wide range of exchange-correlation functionals, and compared their results with analogous experimental measurements. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) approach most accurately reproduced the experimental parameters. Isaev et al. (2007) investigated the ground state properties and phonon spectra of B1-type mononitrides of Group III–VI transition metals. The structural, elastic, and electronic properties of several MoN phases were investigated by (Kanoun et al. 2007) and are summarized in Table 1.

Computed and measured equilibrium lattice parameters: a (Å), c (Å), bulk modulus B (GPa), Young’s modulus E (GPa), and Poisson’s ratio v.

| NaCl–MoN | ZB–MoN | δ 1 -MoN | δ 3 -MoN | CsCl–MoN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 4.304a | 4.616a | 2.868a, 2.868b | 5.710a, 5.735b | 2.67a |

| c | – | – | 2.80a, 2.81b | 5.625a, 5.628b | – |

| B | 351.5a | 274.8a | 376.7a | 379.4, 380b | 354.8a |

| E | 461.6a | 139.6a | 640.0a | 611.3a | 695.9a |

| v | 0.23a | 0.41a | 0.24a | 0.28a | 0.13a |

-

aDFT calculations by the GGA method (Kanoun et al. 2007). bAnalogous experimental findings (Ganin et al. 2006).

In DFT calculations, Zhao et al. (2010) reported the structural, mechanical, and electronic properties of 4-d transition-metal mononitrides with NaCl, NiAs, and WC-type structures. Among the investigated geometries, the MoN phase with the NiAs-type structure displayed the highest hardness (with bulk and shear moduli of 351 and 239 GPa, respectively). Liu et al. (2014) conducted a DFT study of Group V–IIX transition metal nitrides. They reported that CrN, MoN and WN with the NbO structure exhibited the highest Vickers hardness (H V > 20 GPa).

Several recent DFT studies predicted the existence of meta-stable MoN x phases through extensive and systematic computational screening. Sun et al. (2017) employed a revolutionary data-mined structure-prediction algorithm (DMSP) to in silico synthesize new MoN x structural phases. The procedure comprises several steps. It commenced with training the DMSP on the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) followed by isostructural mapping of potential compounds with the objective to pinpoint cations that are “statistically” susceptible for atomic substitution. Accurate identification of synthesizable MoN x phases requires precise values of nitrogen chemical potential and enthalpies of formations of involved species. Through this extensive computational procedure, it has been predicted that stable structures of Mo3N5, and Mo2N3 at certain values of critical chemical potential of nitrogen (Sun et al. 2017). Most important, the DFT-powered scan procedure questioned the thermodynamic stability of the N-rich phase MoN2 in view of its compositional proximity to that of MoN at accessible values of nitrogen chemical potential. While as the MoN2 phase retains a stable phase evidenced by DFT calculations, the question arises on the governing mechanism for its formation. By using a similar global structural search approach to that of (Sun et al. 2017), Zhang et al. (2017) reached to the same conclusion; the MoS2-like MoN2 structure is not mechanically stable. They demonstrated that the ground state of the MoN2 (termed as tetra-MoN2 phase) exhibits a semi-conductor nature with higher stability than the metallic “seemingly unstable” H-MoN2 phase. This new phase features a tuneable magnetism and Mo covalent bonding.

Wei et al. (2019) applied a crystal structure search algorithm to locate R-3m MoN6 phase that is mechanically stable. This phase features a benzene-like N6 structure that encircled isolated Mo cations (Figure 7). With the presence of N single bonds, Wei et al. (2019) predicted the phase to find direct applications in high-density-energy materials. Nonetheless, it was pointed out that this phase has not yet been synthesized experimentally. It will be insightful to use the DFT-scan approach to suggest synthesis mechanisms and a working nitrogen potential for this phase. A similar structural scan was performed by Ding et al. (2018). They located a stable orthorhombic Cmc21 MoN2 configuration, which is even lower in energy than the experimental synthesized structure rhombohedral MoS2-like MoN2 structure. This finding is in accord with that of (Sun et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017).

A top view of the predicted MoN6 phase (Wei et al. 2019). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

DFT calculations can shed a light into the effect of synthesis conditions, most notably temperatures and nitrogen chemical potential, on the mechanical and electronic properties, and thermodynamic stability trends of the MoN x phases. In this regard, a recent study by Lahmer (2019) found that creation of Mo vacancies entails lower formation energies under N rich conditions. On the contrary, formation of N vacant sites ensues via accessible energies with prevailing N poor conditions. Along the same line of enquiry, we postulate that the predictive power of DFT can be tailored to comprehend several intriguing aspects, such as:

The effect of the dopants, N/Mo ratios and vacancies on the optical properties of MoN nano-sheets for applications in solar and optical devices.

Mechanical properties of MoN-films with N/Mo and oxygen content vacancies under real P/T scenarios pertinent to their potential applications in hard coating materials.

The interplay between the atomic constituents and a plausible electrochemical functionality of MoN-materials in supercapacitors.

The role of surface N atoms and N vacant sites as adsorbents for molecules; germane to removal of pollutants in the aqueous phase.

Structural stability of Mo2N layers as a building block in the synthesis of MXenes stacking’s with other metals.

The global DFT-scan approach could be applied to design, based on a precise atomic-base scale, MoN x materials with carefully manipulated catalytic properties and profound selectivity toward the formation of certain chemicals.

The combination between DFT calculations, structural search engines, and data mining are expected to enable ground-breaking discoveries in materials design a wide spectrum of applications. This is clearly underpinned by the superior benchmark accuracy of recent DFT functional that generally resides with a fraction of Å (for geometries) and a few meV (for energies) (Butler et al. 2019).

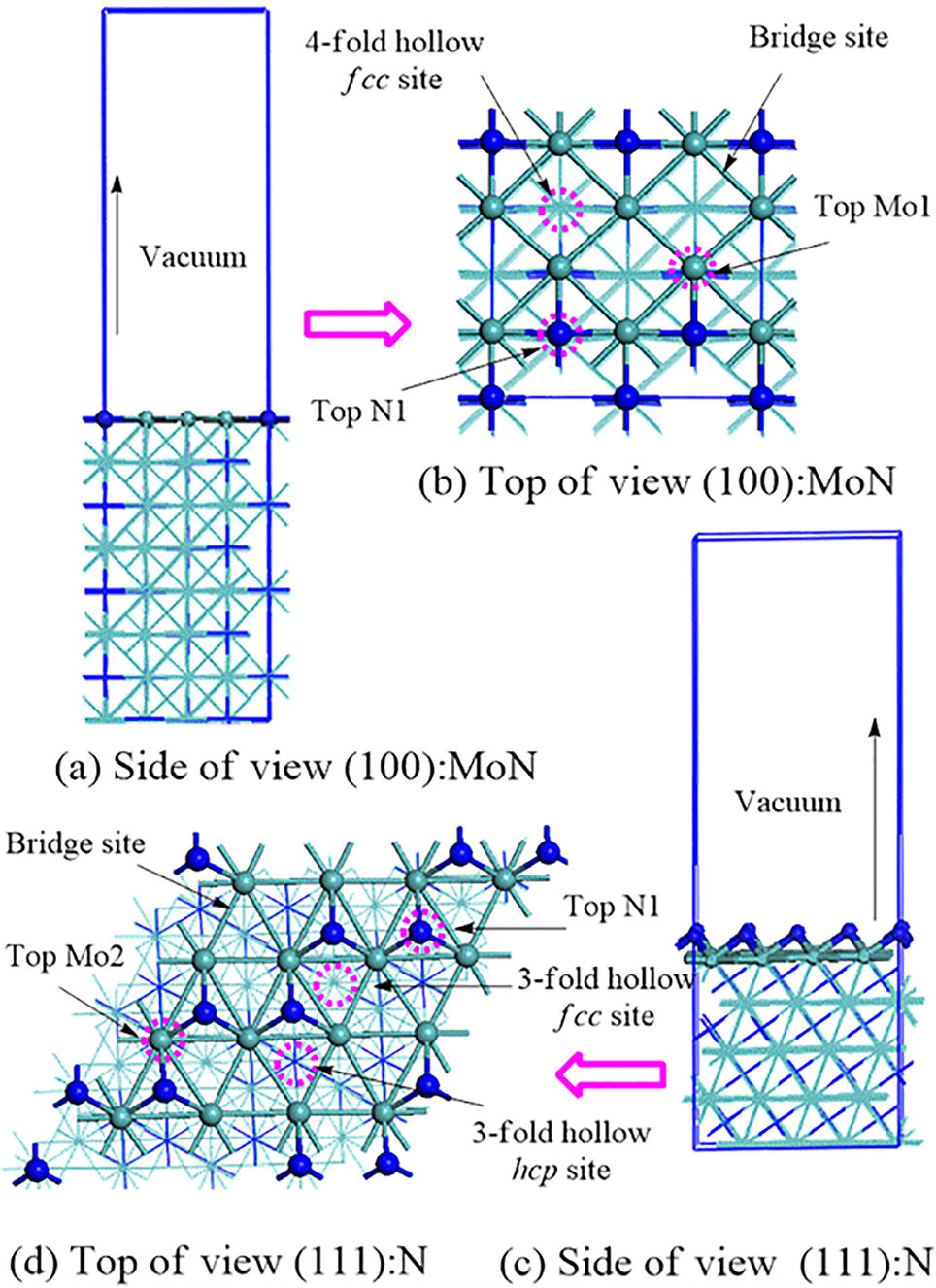

9 γ-Mo2N clean surfaces

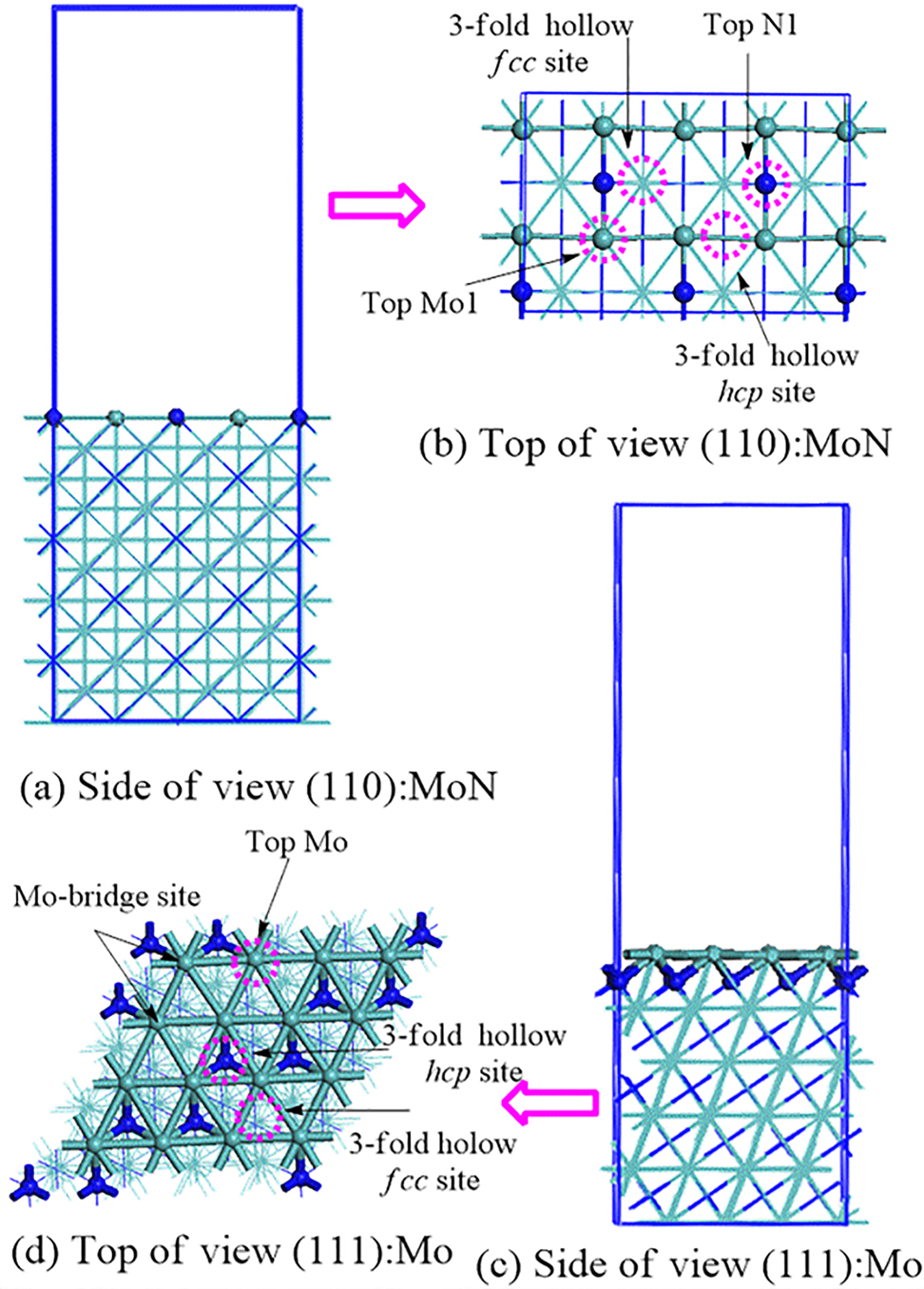

Besides revealing the properties of bulk phases, DFT studies have provided the electronic and structural properties of Mo–N surfaces, most notably those of the γ-Mo2N configuration. Surface relaxation, surface reconstructions relative to bulk positions and surface reaction rates have been most commonly reported. When cleaved along the three Miller indices, the optimized γ-Mo2N bulk yields several configurations (Altarawneh et al. 2016). Some of these surfaces contain Mo/N mixed terminations while others present only N atoms in their topmost layers. Figures 8 and 9 portray optimized (i.e., minimal energy) structures of γ-Mo2N surfaces and their potent active sites.

Optimised configurations of γ-Mo2N (100): MoN and γ-Mo2N (111): N-terminated surfaces and their possible adsorption sites. Light green, blue, and discretised pink circles denote molybdenum atom, nitrogen atoms, and surface active sites, respectively. Reproduced from (Altarawneh et al. 2016) with permission from the American Chemical Society, 2016.

Optimised configurations of γ-Mo2N (110): MoN and γ-Mo2N (111): Mo- terminated surfaces. Light green, blue, and discretized pink circles denote molybdenum atoms, nitrogen atoms, and surface active sites, respectively. Reproduced from (Altarawneh et al. 2016) with permission from the American Chemical Society, 2016.

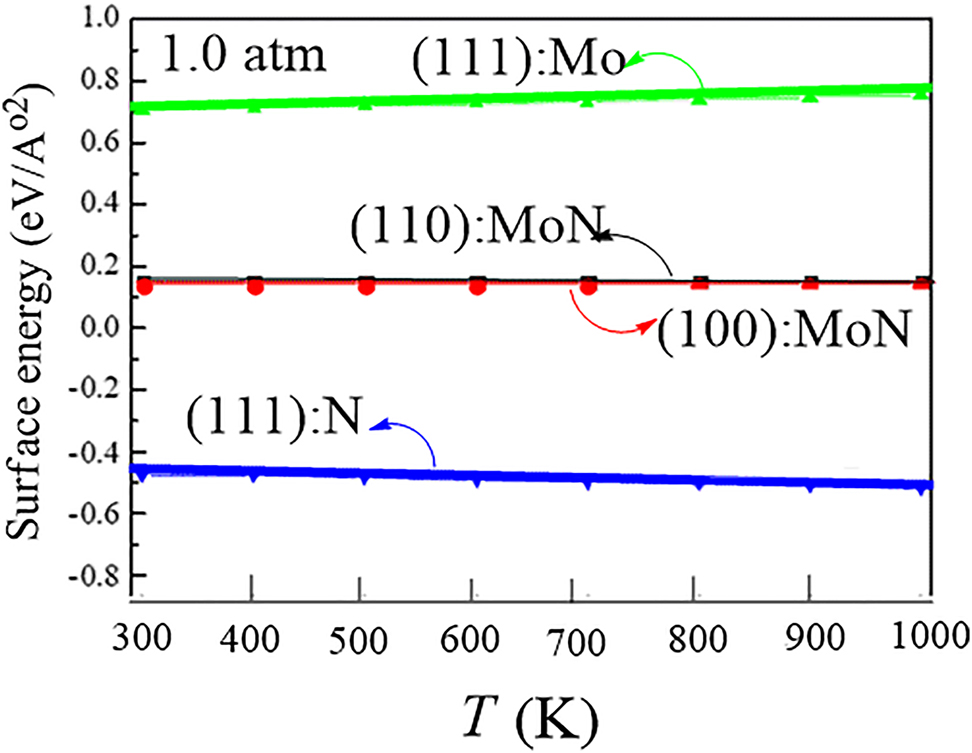

Figure 10 shows the phase stability diagram of molybdenum surfaces constructed in ab initio atomistic thermodynamics calculations. The most thermodynamically stable γ-Mo2N surface, namely, γ-Mo2N (111) has been subsequently targeted in several DFT-based studies on γ-Mo2N catalysis (Altarawneh et al. 2016; Zaman 2010).

Phase stability diagram of molybdenum nitride surfaces. Reproduced from (Altarawneh et al. 2016) with permission from the American Chemical Society, 2016.

10 General synthetic routes of Mo–N catalysts via temperature-programmed reaction (TPR)

TMNs are typically synthesized at high temperature by metallurgical processes, yielding powders with low specific surface area (SSA) (Lee and Ham 2003). However, these powders are unsuitable for catalytic applications that require materials with high SSA. High-surface-area TMNs for catalytic applications are usually prepared by temperature-programmed reactions (TPRs) (Volpe and Boudart 1985). This section reviews the synthesis of transition metal nitrides, focusing on molybdenum nitride surfaces. In general, NH3 is the preferred nitridation agent because it supplies nitrogens more easily than other nitrogen sources. The main synthetic methods of TMN catalysts are detailed elsewhere (Choi et al. 1994; Volpe and Boudart 1985). TMNs are commonly fabricated by the gas–solid reaction between MO3 (where M refers to Mo or W) and NH3 or mixed NH3 and Ar. Jaggers et al. (1990) proposed a reaction pathway yielding molybdenum nitride with a high surface area. They nitrided a MoO3 precursor with NH3, producing a mixture of MoO x N1−x and MoO2. The oxynitride MoO x N1−x was then transformed to fcc-Mo2N (at higher temperatures) and hexagonal MoN phases. However, the products of this direct nitridation method have low surface areas.

To realize the promising catalytic applications of MoN-based materials, researchers have increased the surface areas of these materials with modified synthetic methods (Mckay 2008). Volpe and Boudart (1985) reported the first synthesis of metal nitride catalysts with high surface area (220 m2 g−1), achieved by reacting NH3 with a MoO3 precursor. Electron diffraction measurements confirmed a topotactic N-induced conversion of the MoO3 platelets. Marchand et al. (1996) documented that the morphology and surface area of the prepared nitride materials can be controlled by adjusting the NH3 space velocity and operating temperature. The impact of the preparation parameters on the structural properties of synthesized catalysts was reported by Choi et al. (1994). They proposed a two-step heat treatment of molybdenum trioxide MoO3 in an NH3 atmosphere. In the first step, the temperature is increased from 623 to 723 K; in the second step, it is raised from 723 to 973 K. These two temperature processes occur at various space velocities. The results suggested that molybdenum nitride with high surface area forms by several reactions, which depend on the deployed space velocity and heating rates. They concluded that high-surface-area γ-Mo2N resulted from the conversion of MoO3 precursor into H x MoO3 and γ-Mo2O y N1 − y intermediates. However, the reaction pathway via intermediates such as MoO2 also produced molybdenum nitrides with medium and low surface areas. These categories of ammonolysis operations further promote the production of pseudo-morphic configurations (Mckay 2008). Temperature programmed ammonolysis is a widely applied technique to synthesis diverse phases of Mo–N based catalysts from different precursors (i.e., MoO3, MoS2 and MoCl5) (Hargreaves 2013). The β-Mo2N0.78 phase is formed using N2/H2 as the synthesis gas with MoO3 precursor. Moreover, MoS2 and MoCl5 δ-MoN with NiAs structure is formed while γ-Mo2N displays a fcc structure. Whereas, the formation of both δ-MoN and Mo5N6 can be attained by ammonolysis of MoS2 and MoCl5.Typically, the formation temperature, which depends upon precursor, governed the final phase produced phase, suggesting β-MoN as the low temperatures phase and γ-Mo2N as high temperature phase while intermediate temperatures entails a mixture of the two phases (Hargreaves 2013).

Baek et al. (2021) has recently surveyed operational conditions that increases the surface area of molybdenum nitrides from nitridation of α-MoO3 by ammonia. Investigated conditions spanned ammonia flow rate (2–11.5 L/h), temperature (425–846 °C), and heating rate (30–240 °C/h). It was found that a maximum surface area (∼150 m2/g) could be obtained at 630 °C. Higher temperature resulted in a phase transition γ-Mo2N → β-Mo2N (at 770 °C) and to metallic Mo at 880 °C. Other optimum conditions constitute a molar NH3 hourly space velocity at 64.2 L/h and a heating rate of 50 °C/h. More importantly, it was illustrated that the surface area is most sensitive to the nitridation temperatures. Other operational parameters exert rather a little variation. In preparation of high-surface β-Mo2N catalysts from treatment of α-MoO3 in N2/H2 stream, it is generally viewed that optimum conditions included a reaction temperature of 660–750 °C, a reaction time of 330 min, and a mixing ratio of 15% v/v N2/H2 (Cardenas-Lizana et al. 2011, 2013). As discussed earlier, the catalytic activities depend on the crystallographic phase structure and the availability of nitrogen vacant sites. For instance, in the gas phase hydrogenation of p-chloronitrobenzene (p-CNB) to p-chloroaniline (p-CAN) and through H2 chemisorption/temperature programmed desorption analysis, a higher hydrogen uptake capacity (per unit area) was reported for tetragonal γ-Mo2N (33–36 m2 g−1) in reference to the cubic β-Mo2N (7 m2 g−1) (Perret et al. 2012). Haddix et al. (1988) characterized the adsorption of H2 over γ-Mo2N with high surface area (∼120 m2 g−1) by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). They proposed that H2 strongly binds to the catalyst surface. Ranhotra et al. (1987) fabricated porous Mo2N (fcc) powders by H2 reduction of MoO3 to metallic Mo in the presence of H2. This phase contained pores of approximate diameter 17 Å, and exhibited a high Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area (180 m2/g). More recently, Roy et al. (2015) prepared bulk γ-Mo2N with a high surface area (116 m2 g−1). In the programmed ammonolysis procedure, nitrided materials are typically cooled in inert gas (helium, argon or nitrogen) or in a diluted NH3 atmosphere (Markel and Van Zee 1990). The nitrides are then passivated by passing through a dilute oxygen mixture (usually < 1%) in an inert gas (Colling et al. 1996; Furimsky 2003). Any formed oxide layer is then removed by reduction with H2 or N2/H2. As is well documented, ammonolysis of MoCl5 and MoS2 precursors yields various nitrides, most notably, δ-MoN and Mo5N6 (Ganin et al. 2006). Wise and Markel (1994) synthesized a topotactic γ-Mo2N with high surface area (150 m2 g−1) via N2/H2 treatment of MoO3. This nitridation procedure enables the facile elimination of heat transfer from the endothermic decomposition of NH3 (the N–H bond dissociation energy of NH3 is 93.21 kcal/mol (Luo 2002)). The surface area of a molybdenum nitride phase strongly depends on the synthesis conditions, namely, the flow rate of the nitrogen source, the temperature, and the heating rate. Li et al. (1998) synthesized a γ-Mo2N by TPR. They proposed that the pseudo-morphological nature of the overall NH3 + MoO3 pyrolysis reaction increases the surface area of the final nitride phase. Claridge et al. (2000) produced nitrides from carbide precursors by a complex procedure that fabricates carbide and nitride materials with high surface area from binary and ternary oxide precursors (vanadium, niobium, tantalum, molybdenum, and tungsten). Typically, the TPR of various Mo–N and Mo–C phases from MoO3 precursor. In various gas mixtures such as CH4/H2, C2H6/H2, or NH3, materials with surface areas exceeding 40 m2 g−1 can be obtained (see Supplementary Figure S4).

Cairns et al. (2010) explored the influence of impurity level on the β-Mo2N phase prepared by N2/H2 treatment of MoO3 precursors. Minor loads (1.0 wt%) of Pd, Au, Ni, or Cu significantly altered the surface area of the β-Mo2N phase obtained at 750 °C. In another study, Cairns et al. (2009) investigated the impact of precursor source on the β-Mo2N phase. MoO3 precursors supplied by different companies (AnalaR and Sigma–Aldrich, here labelled source A and source S, respectively) afforded β-Mo2N phases with different morphologies (plate-like structures and deformed rectangular blocks from sources A and S, respectively, as evidenced in SEM images). Roy et al. (2015) developed a novel sacrificial support method for an alternative TPR of MoO3 with an NH3 nitrogen source. This method converts the MoO2 intermediate using MgMoO4, which is advantageous. Xu et al. (2015) suggested a synthetic approach called the self-assembly method, which fabricates a hexagonal-like MoN hierarchical nanochex from single-crystal nanowires.

11 Catalysis by molybdenum nitrides

Catalysis by metal nitrides relies on the presence of N-vacant sites and electronic structures that mimic those of Pt-based catalysts. In hydrogenation reactions of γ-Mo2N, the N-vacant sites host the dissociated hydrogen atoms. The weakly bounded surface H atoms migrate to the adsorbed hydrocarbon species via relatively facile reactions. The governing catalytic reactions mapped in DFT studies are rather limited. Experimental studies on Mo–N based catalysts have provided the chemical conversion values and surface characteristics of adsorbed species. The near-surface structures and compositions of a series of molybdenum nitride catalysts can be detected by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy combined with Fourier analysis, NMR measurements, and XPS (Furimsky 2003). Dongil (2019) recently reviewed the synthesis methods and catalytic properties of mono, binary, and ternary metal nitrides, and discussed the effect of the promoter on improving the catalytic performance. Table 2 stated the main catalytic activities over various configurations of molybdenum nitride.

Summary of catalytic activities over various configurations of molybdenum nitride.

| Catalyst | Preparation method | Shape and morphology | Surface area | Reaction products | Applications | Catalytic activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Mo2N | TPR of MoO3 with NH3 | Spherical and cubic particles | 100 m2 g−1 | – | Pyridine hydrodenitrogenation catalysts | – | Choi et al. (1992) |

| Mo2N | TPR of MoO3 in N2/H2 treatment at 573 K, pressure of 5 MPa | – | 9–115 m2 g−1 | Phenol | Hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) of guaiacol | 10% conversion of guaiacol | Ghampson et al. (2012) |

| γ-Mo2N | TPR NH3 | – | 150 m2 g−1 | Ammonia | NH3 synthesis | Reaction rate at 673 K under 0.1 MPa was 43 μ mol h−1 g−1 | Kojima and Aika (2001) |

| Mo2N/graphite | TPR of carbon-supported Mo precursors with NH3 | – | 91 m2 g−1 | Unsaturated alcohol | Crotonaldehyde hydrogenation | High selectivity to unsaturated alcohol; crotylalcohol selectivities exceed 60% | Balasubramanian et al. (2018) |

| γ-Mo2N | TPR reduction of MoO3 in flowing NH3 | Porous particles | 108 m2 g−1 | Butane | Thiophene hydrodesulfurization (HDS) | 38.1% conversion efficiency at 673 K | Markel and Van Zee (1990) |

| NiMoN x /C | Treatment of NiMo/C in NH3 flow at 700 °C | Nanosheets | – | – | Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) | 78 mV at 0.24 mA cm−2 in acid | Chen et al. (2012) |

| Mo2N | TPR of MoO3 with a mixture of N2/H2 gases | – | 165 m2 g−1 | Methane | Hydrogenation of CO | High activity and selectivity of methane formation | Liu et al. (2003) |

| β-Mo2N | Temperature programmed treatment of MoO3 in flowing N2 + H2 | Platelets | 17 m2 g−1 | p-chloroaniline | Hydrogenation of p-chloronitrobenzene | 100% selectivity towards NO2 group reduction; reaction rate constant k = 2.0 min−1 | Cardenas-Lizana et al. (2011) |

12 Adsorption and activation of simple molecules

Molybdenum nitride compounds display high catalytic performance in a wide array of chemical reactions, including CO hydrogenation, ethane hydrogenolysis, NO reduction, and hydro-treatment processes. The availability of potent active sites on the catalyst surface critically affects the catalytic activity of a material. A catalytically potent material must adsorb and activate the commonly deployed probe molecules such as CO, H2, NO, NH3, C5H5N, and O2. Kinetically, the activation route will close if the molecular adsorption and activation are slower than the surface-mediated reactions. To avoid deactivation or positing of the active sites, the produced radicals must be rapidly desorbed. When the products are desorbed from the surface, the active sites become available for another adsorption–activation–transfer–desorption cycle.

12.1 Hydrogen (H2)

Catalysis on metal nitride surfaces is most commonly probed using hydrogen molecules. Typically, a catalyst is active when it can adsorb and activate molecular hydrogen (H2) at a sufficient reaction rate for a proposed period of time within a specific temperature window. Hydrogen adsorption over polycrystalline γ-Mo2N commences sluggishly at room temperature, indicating a controlling resistance either in the film or at the pores (Li et al. 1996b). Supplementary Figure S5 plots the hydrogen uptakes of Mo2N at 673 K (Li et al. 1996b). They measured the volumetric H2-uptake over Mo2N with a surface area of 79 m2 g−1 during reduction at 673 K. As inferred by the uptake isotherms in the 308–623 K range, the total and reversible hydrogen uptakes increased with temperature. However, the irreversible hydrogen uptake was abruptly augmented when the uptake temperature reached 423 K. The irreversible hydrogen uptake was maximized at 473 K. One proposed mechanism of hydrogen adsorption signifies the heterolytic dissociation on the surface Mo–N pairs.

Based on NMR measurements, Haddix et al. (1988) concluded that hydrogen dissociatively adsorbs over γ-Mo2N with a high surface area (∼120 m2/g). The total hydrogen uptake is upper-limited to approximately 10% of the total available BET surface area of γ-Mo2N, suggesting a relatively high activation energy of the hydrogen molecules on γ-Mo2N. The preferred adsorption sites were predicted as nitrogen-deficient sites. The interactions of H2 and NH3 with clean Mo(100) and nitrided Mo(100)-c(2 × 2)N surfaces were investigated via temperature programmed desorption (TPD) and Auger electron spectroscopy (Bafrali and Bell 1992). For a given hydrogen coverage, the H2 concentration on the nitrided surface was ∼4–10 times lower than the expected H2 concentration on a clean Mo (100) surface. Li et al. (1996a) treated γ-Mo2N with high surface area (134 m2/g) in a hydrogen environment at specific temperatures. Prior to TPD experiments, the heat-treated samples were cooled to room temperature in an H2 flow.

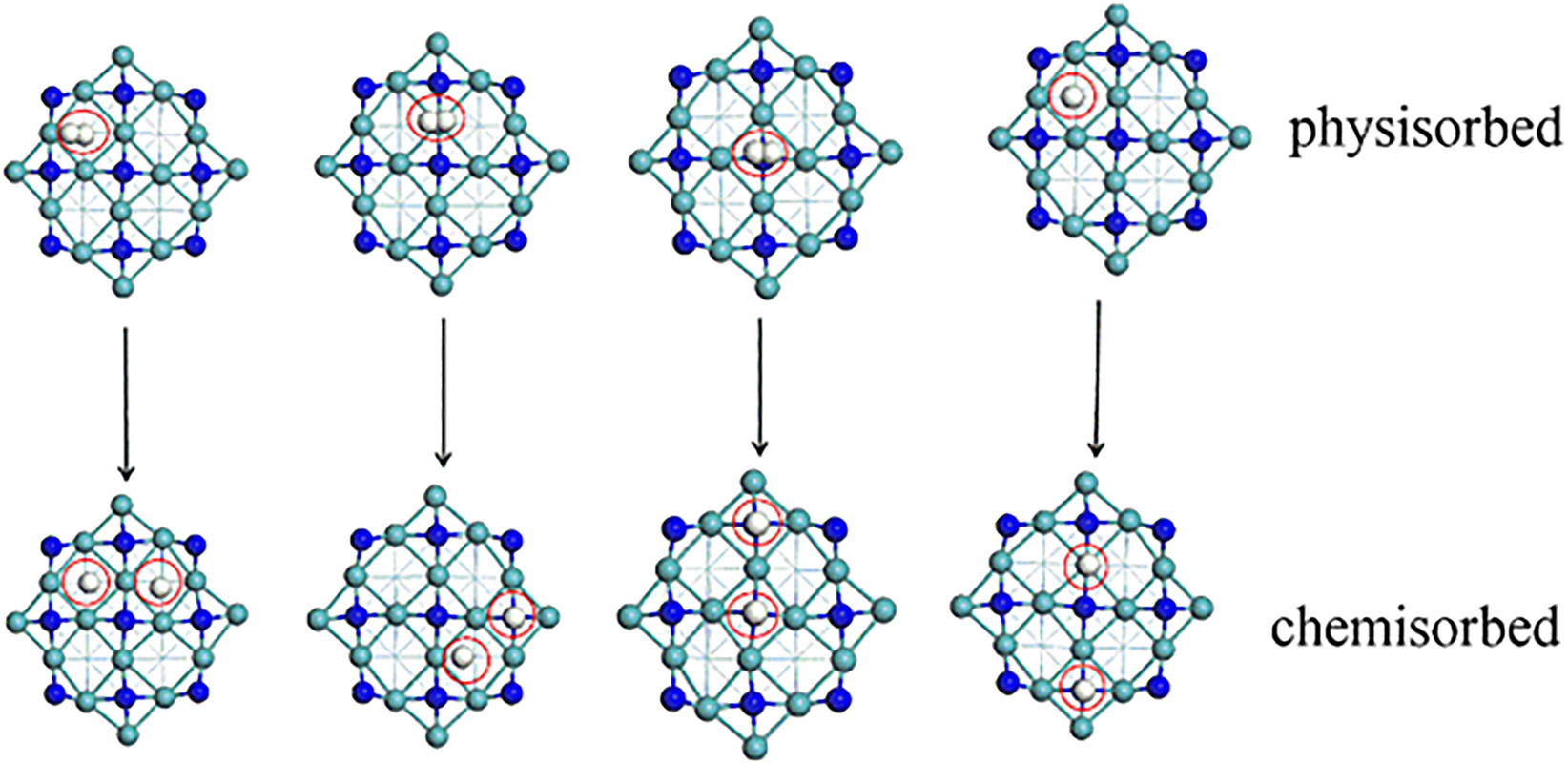

Via applying temperature programmed desorption (TPD) and temperature programmed adsorption (TPA) techniques (Zhang et al. 1997), it was found that the adsorbed hydrogen species migrated from sites with low adsorption energy (N-vacant sites) to sites with high adsorption energy (N-occupied sites). This facile surface diffusion sustains the dynamic equilibrium. Two hydrogen adsorption peaks appear at relatively high temperatures, one at 517 K and the other at 736 K, were detected, which were assigned to low and high adsorption sites, respectively. The TPD and TPA measurements indicated a rapid equilibrium between the adsorption and desorption reactions. It has been conveyed that Mo nitrides can straightforwardly chemisorb hydrogen owing to the contraction of the d-band and the changes in the electron density that result of the interstitial incorporation of N in the Mo metal lattice. Moreover, in the Mo2N-based catalysts, hydrogenation reaction occurs over nitrogen deficient surface sites and Mo/N ratio influences the catalytic performance (Dongil 2019). Jaf et al. (2017) determined the molecular hydrogen adsorption behaviour over γ-Mo2N in DFT calculations. It was demonstrated that hydrogen dissociation preferentially occurs over N vacant sites. Surface-assisted rupture over surface N sites ensues with significantly higher barriers. The H2 adsorption and dissociation modes are portrayed in Figure 11 (Jaf et al. 2017).

Non-dissociative and dissociative uptakes of molecular H2 over the γ-Mo2N (100) plane (top view), redrawn from (Jaf et al. 2017).

12.2 Oxygen (O2)

Oxygen can reportedly diffuse into the subsurface layers of molybdenum nitrides. In a dilute O2 mixture, a thin oxide passivating layer may form on the molybdenum nitride layer. The rates of subsurface oxygen diffusion and reaction with Mo are accelerated at higher temperatures. If subsurface oxygen diffusion occurs, higher operating temperatures can systematically enhance the overall uptake of oxygen because additional oxygen atoms can be adsorbed on subsurface sites (Choi et al. 1992). As shown in Supplementary Figure S6, the oxygen uptake is higher at 298 K than that at 195 K. This result can be explained by either the oxidation of subsurface layers or incomplete surface coverage. Markel and Van Zee (1990) demonstrated that the developed passivation layer produces an oxynitride phase but no distinct oxide phase.

Adsorption of oxygen on pure molybdenum surfaces results in the formation of oxynitride phases or a surface oxide layer. A recent study by Zhang et al. (2020) closely examined the role of the MoO x oxide layer on the activity of Pt/γ-Mo2N catalysts in the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction. Their kinetic analysis discloses that MoO x (2 < x < 3) actually constitutes the intrinsically active surface in the Pt/γ-Mo2N catalyst. Based on DFT computations, they explained that oxygen vacancies could readily form over the highly distorted MoO x phases, and thus facilitating dissociative adsorption of water molecules. Along the same line of enquiry, it was shown that the acid-base character of O–Mo2N surfaces strongly depends on the N/O atomic ratio (McGee and Thompson 2020). O–Mo2N surfaces with the highest N/O atomic ratio entails the highest base site density, and hence selectivity toward the formation of certain products. Clearly, more studies are needed to better understand the interplay between the different atomic constituents, strain and defects, in the heterostructured Mo–O/N structures.

While the N vacant sites in metal nitrides assume some similar roles to the O vacant sites in transition metal oxides, there are some fundamental differences in their catalytic capacity. The surface unsaturation on both metal nitrides and oxides render the N/O vacant sites to act as a potent host for incoming gas phase molecules. Over transition metal oxides, the surface unsaturation is compensated by a reaction with water leading to tailored acid–base and redox properties. The redox reactions in transition metal oxides (as in ceria for instance) is derived by a relatively facile removal of surface oxygen leading to vacant sites (Wang et al. 2018). Similarly, it was reported via analysis of formed N species with different N isotopes (14 and 15) during de-NO x reactions, that N vacant sites can be created through the removal of surface N atoms as nitrogen molecules from the γ-Mo2N surface (He et al. 2001). Our computed overall energy penalty for the creation of N sites, on the γ-Mo2N surface, amounted to 38.1 kcal/mol (Altarawneh et al. 2016). In hydrogenation reactions in particular, dissociated hydrogen atoms in transition metals resides over O sites rather than over vacant sites. In case of γ-Mo2N surface Jaf et al. (2017), we have established that hydrogen atoms preferentially occupy N vacant sites rather than surface N sites.

12.3 Carbon monoxide (CO)

(Yang et al. 1998) investigated the surface active sites and adsorption properties of CO on fresh and reduced passivated samples of Mo2N/Al2O3. The infrared (IR) spectra of CO adsorption over the fresh and reduced passivated samples exhibited distinct patterns. As presented in the IR spectrum of the fresh sample, the CO molecules adsorbed on the molybdenum and nitrogen sites, forming surface CO and NCO species. However, the reduced passivated sample formed an oxynitride layer. In general, the adsorbed CO molecules were dissociatedly adsorbed to C and O atoms. The IR results clearly demonstrated that the H2 preadsorbed on fresh Mo2N/Al2O3 hindered the CO adsorption, presumably by competing for the active sites.

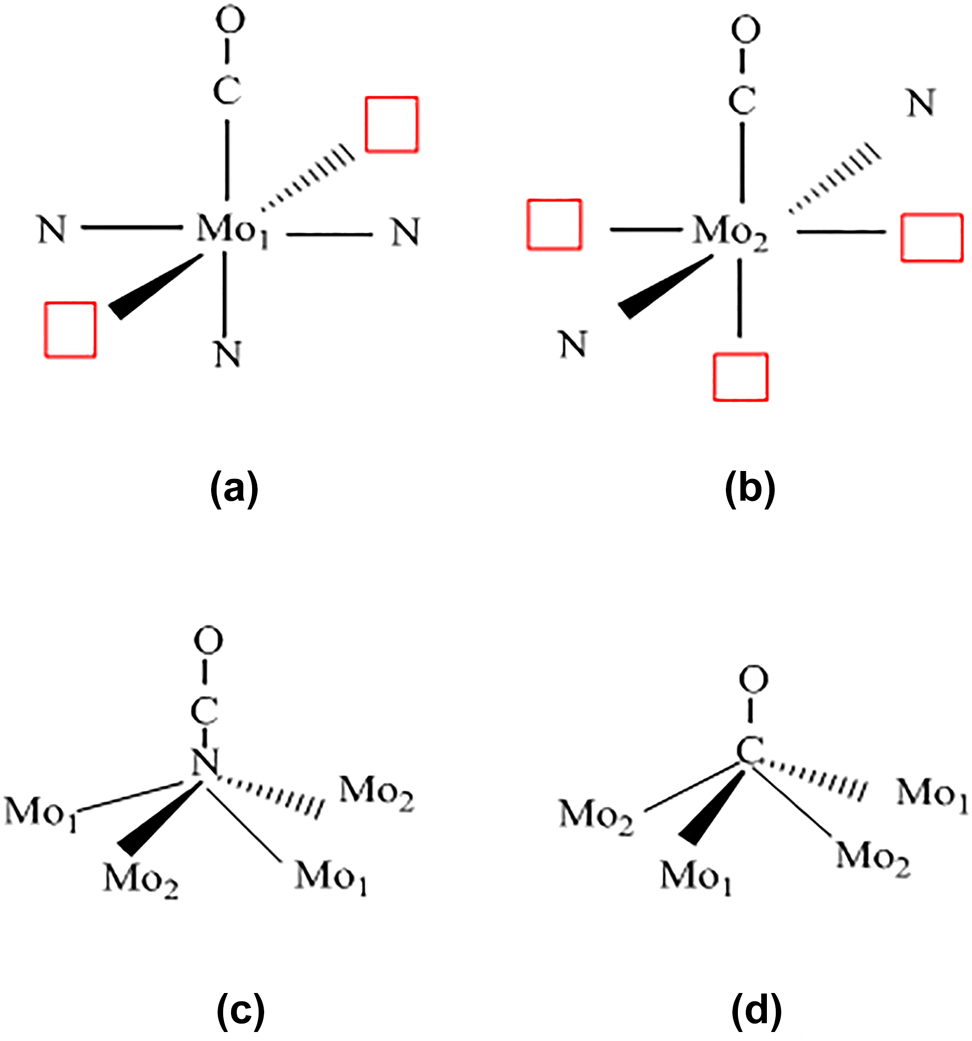

In DFT calculations, Frapper et al. (2000) determined the most favorable energetic sites for CO molecular adsorption over the γ-Mo2N (100) plane. The CO molecules were located at several adsorption sites. As shown in Figure 12, the four lowest-energy adsorption positions were Mo1, Mo2, surface N atoms, and 4-fold vacant sites. With an adsorption energy of −1.49 eV (−34.3 kcal/mol), the 4-fold vacant site was predicted to minimize the coordination mode. The adsorption energies were comparable at the three sites. Chemisorbed CO molecules on the Mo2N catalyst have not been observed in experiments; however, in the IR interpretation, 4-fold hollows on the (100) fcc surface are promising active sites for diatomic molecules. The binding energies at the Mo1 and Mo2 sites were computed as −1.43 eV (−32.9 kcal/mol) and −1.32 eV (−30.4 kcal/mol), respectively (see Figure 12), similar to the adsorption energy of CO over Pd(100) (1.44 eV or 33.2 kcal/mol). This result demonstrates the well-known Pt-like catalytic properties of nitride molybdenum catalysts (Eichler 2002). CO adsorption over N sites yields chemisorbed NCO species with a slightly endothermic adsorption energy (0.23 eV or 5.3 kcal/mol); however, no activation barrier was reported. Despite the low endothermicity, removal of surface N atoms is expected to encounter a sizable energy barrier (Frapper et al. 2000).

Schematic showing the possible active sites of CO adsorption on a clean (100) 1 × 1 surface: (a) on Mo1, (b) on Mo2, (c) on nitrogen surface atoms Nsurf, and (d) on 4-fold sites µ4-CO. Red squares symbols represent the vacant 4-fold hollow sites (Frapper et al. 2000). Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society.

12.4 Adsorption of N2

N2 dissociatively adsorbs over Mo2N and saturates the surface at high temperatures. In DFT calculations, the dissociation energy was predicted to be −2.04 eV/N2 molecule (Frapper et al. 2000). Along the same line of enquiry, Hillis et al. (1966) predicted an extremely weak adsorption of molecular nitrogen over a molybdenum dioxide (MoO2) surface during NH3 synthesis. Moreover, 146 mL (STP)/(3.39-g molybdenum) of N2 was absorbed on molybdenum metal subsequent to 69 h of nitridation in a pure N2 atmosphere (Stampfl 2005). The chemisorption of nitrogen sites by nitrogen atoms over active metal–N bonds promotes the Mars–Krevelen mechanism (Jaf et al. 2018b). Molybdenum containing ternary nitrides such as Co3Mo3N will likely act as nitrogen transfer agents via the Mars−van Krevelen-like mechanism in the cyclic release and replenishment of nitrogen. In these reactions, Co3Mo3N serves as a nitrogen-storage medium (Hunter et al. 2010; Zeinalipour-Yazdi et al. 2015).

13 Catalytic activity of molybdenum nitride compounds

Several researchers have evaluated the catalytic performance of Group V and VI metal nitrides and carbides in catalyzing various reactions, including butane dehydrogenation, isomerization, and hydrogenolysis. Neylon et al. (1999) observed that the estimated turnover frequencies of nitride and carbide catalysts were of the same order of magnitude as that of the Pt–Sn/Al2O3 catalyst. Supplementary Figure S7 presents the Arrhenius plots of HER over selected Group V and VI metal nitrides and Pt–Sn/Al2O3. The molybdenum, tungsten, and vanadium nitrides were considerably active during a number of reactions. Herein, we solely focus on Mo2N-mediated reactions as Table 2 demonstrates.

13.1 Hydrotreatment reactions

Hydrotreatment reactions are among the most essential catalytic processes in petrochemical industries. These reactions remove metals or heteroatoms such as, S, N, and O from crude oil feedstock. Depending on the target molecule and its atomic constituents, hydrogenation can be catalyzed by hydrodesulfurization (HDS), hydrodenitrogenation (HDN), hydrodeoxygenation (HDO), or hydrodemetallization (HDM) (Bafrali and Bell 1992; Furimsky 2003; Hillis et al. 1966). To limit the environmental damage caused by the increasing SO x and NO x emissions from thermal processes, strict rules and regulations have been imposed. Accordingly, catalyst scientists have turned to Mo–N as a cost-effective substitute of noble metals in hydrogenation catalyst applications (Dolce et al. 1997; Hargreaves 2013; Nagai 2007).

13.1.1 Hydrogenation (HYD)

Nitrogen inclusion significantly alters the catalytic activities of the host metal (Mo) by adjusting the bonding strengths and improving the electronic structure of the host (Oyama 1992). The higher catalytic activity and selectivity of TMNs than their metal hosts is ascribed to the electronic effect of metal nitrides, which is governed by the DOS of the d-orbital. In a nutshell, the metal–nitrogen bonds reduce the deficiency in the d-band occupancy of the metal, promoting electron donations (Heine 1967) from the metallic to the N atoms. Owing to these significant electronic changes, the catalytic capacity of Mo–N based materials in hydrotreatment processes can match those of noble metals (Chen 1996; Chen et al. 2013b; Furimsky 2003).

The catalytic performance of transitional metal nitrides is highly sensitive to the selected transition metal, nitrogen ratio, and structural phase (cubic δ or hexagonal β). The δ phase generally affords a higher turnover frequency of β-Mo2N than that in the hexagonal phase. Recent DFT studies have provided a molecular-level understanding of the catalytic reaction mechanisms over the surfaces of transitional metal nitrides. As mentioned earlier, NMR and TPD measurements provide insights into dissociative hydrogen adsorption on Mo2N (Haddix et al. 1987; Li et al. 1996a, 1996b). The literature has reported the electronic factors contributing to catalysis over transitional metal nitrides and the governing mechanisms and surface modifications during the course of gaseous molecule–surface interactions. Nonetheless, several aspects warrant further investigation; most importantly, the phenomena leading to the poisoning of catalytic active sites at higher temperatures, the potential influences of dopants and atomic terminations on surface diffusion, and the effect of oxygen-rich streams versus pyrolytic conditions on catalytic activity.

Reviews on transitional metal nitrides have mainly summarized the structures and experimental findings related to hydroprocessing. TPD results pertinent to hydrogen interaction with Mo2N have been discussed but without accounting for the mechanisms and structural/electronic factors contributing to the catalytic behaviour of TMNs. Selective HYDs are the core processes of many chemical industries. Furthermore, the HYD activity and/or the selectivity of TMNs is affected by several factors, including the SSA, nature of the surface-active sites, and crystalline phase of the catalyst (Nagai 2007).

Applying the DFT approach, Jaf et al. (2017) discussed the HYD of acetylene over catalysts assisted by γ-Mo2N (100) and (111) indices. Consistent with the experimental observations, the proposed mechanism predicted a higher (lower) selectivity for the partial hydrogenation of acetylene to ethylene (ethane). Also consistent with the experiments, the irreversible mode of C2H2 over γ-Mo2N demonstrated the exceptional catalytic properties of γ-Mo2N in the selective hydrogenation of ethyne to ethene with a selectivity of 85% (Hao et al. 2000). The results of this investigation highlighted the promising industrial applications of crystalline metal nitride catalysts that selectively hydrogenate the triple bonds of ethyne to ethene. This selectivity primary stems from a higher activation barrier for the hydrogenation of alkenes in reference to their desorption. Our constructed mechanism by DFT calculations also shows a preference for the partial hydrogenation of 1,2-butadiene into C4H8 rather than full hydrogenation into C4H10 (Jaf et al. 2018c). In other words, the selectivity toward partial hydrogenation stems from kinetic as well as thermodynamic considerations.

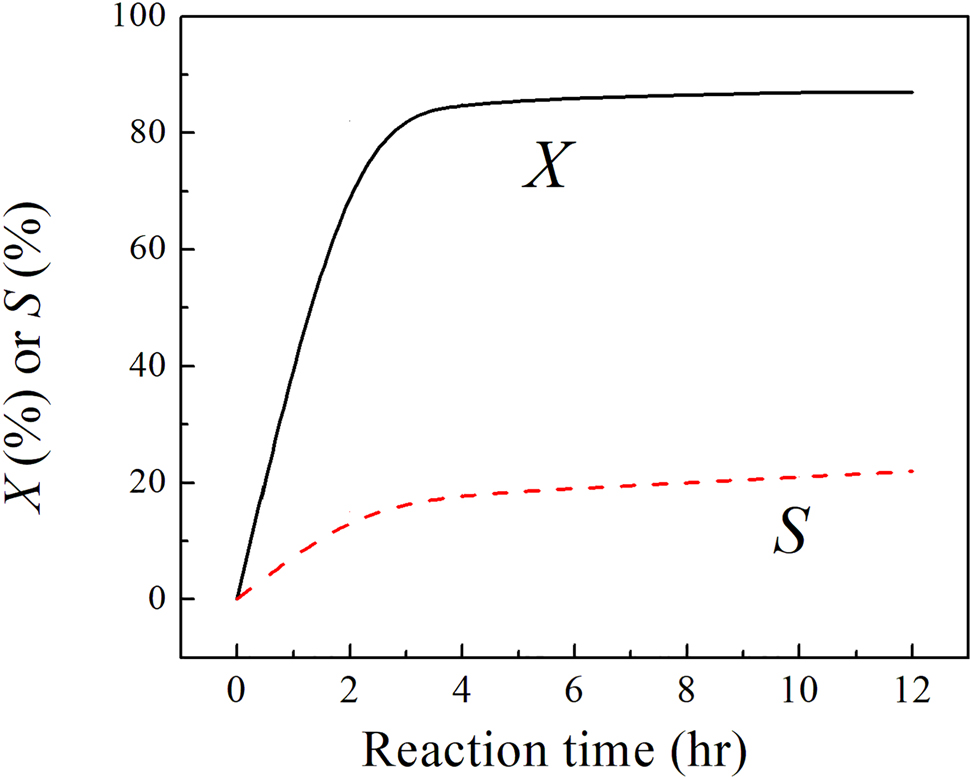

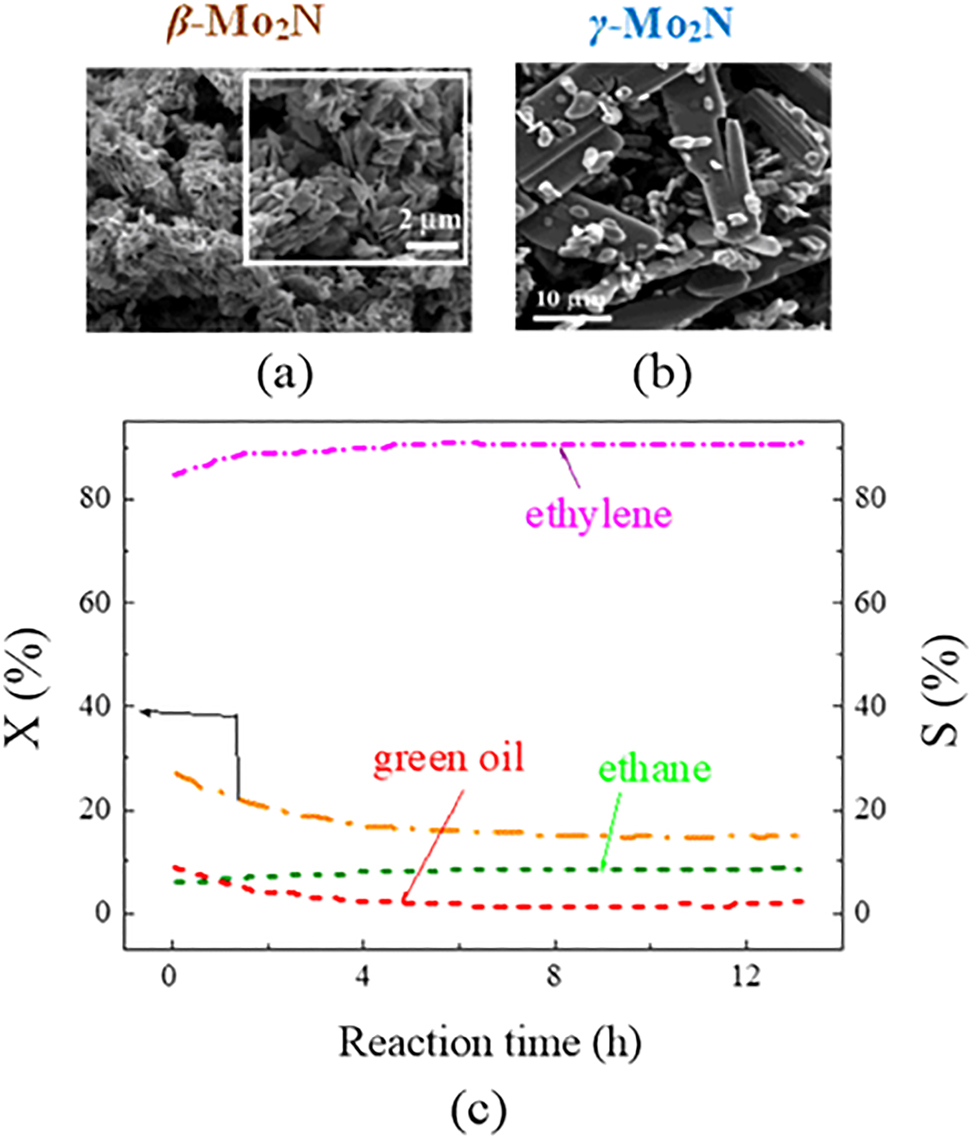

Recently, Cárdenas-Lizana et al. (2018) synthesized catalysts with two crystalline phases for the selective hydrogenation of alkyne: tetragonal β-Mo2N with surface SSA = 6–15 m2 g−1 and cubic γ-Mo2N with SSA = 45–135 m2 g−1. Catalytic tests disclosed that both materials were highly selective (77–90%) for acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene (see Figure 13).

Temporal variation of acetylene conversion (X) and selectivity (S) of ethylene over γ-Mo2N redrawn from Cárdenas-Lizana et al. (2018).

13.1.2 Hydrodesulfurization (HDS)

Mo-based catalysts have been extensively deployed in the HDS of petroleum feed stocks. The HDS process eliminates the heteroatoms from thiophenic compounds such as thiophene, benzothiophene (BT), and dibenzothiophene (DBT) (Aegerter et al. 1996; Babich and Moulijn 2003; Markel and Van Zee 1990; McCrea et al. 1997; Nagai et al. 1993). The latter group of compounds are the major S-carriers in coals and transportation fuels. Ozkan et al. (1997) prepared an unsupported γ-Mo2N catalyst for the HDS of BT in the presence/absence of NH3. The catalyst was highly active toward ethylbenzene formation in the 473–653 temperature range.

To investigate the catalytic activity of DBT toward the HDS reaction, Park et al. (1997) prepared Co- and Ni-promoted nitrided Mo/γ-A12O3 and unsupported molybdenum nitride catalysts by the TPR approach in an NH3 environment. After carefully varying the temperature, pressure, and contact time, they increased the reactivity and selectivity of the catalysts in biphenyl (BPN) and cyclohexylbenzene (CHB) production. Liu et al. (2002) prepared γ-Mo2N and Co-promoted molybdenum nitrides (Co−Mo−N) catalysts with high surface areas, and characterized them by XRD and BET. In the HDS of DBT, both γ-Mo2N and Co−Mo−N exhibited higher HDS activity and selectivity for C−S bond rupture than C–H. Furthermore, the Co-promoter considerably enhanced the HDS activity of γ-Mo2N. Supplementary Figure S8 depicts two main reaction corridors: the HYD of one aromatic ring into a mixture of 4H-DBT and 6H-DBT, which are rapidly converted to CHB by HDS, and the direct desulfurization of DBT to BPN by hydrogenolysis.

(Ramanathan and Oyama 1995) experimentally explored the catalytic activities of a series of transition metal carbides and nitrides of Mo, W, V, Nb, and Ti. The nitrides were prepared by TPR of their oxide precursors with a reactant gas (20% CH4/H2 for the carbide samples and 100% NH3 for the nitride samples). BET chemisorption measurements were probed with N2 and CO molecules. The HDN, HDS, and HDO activities of the catalysts were tested in a three-phase trickle-bed reactor. Supplementary Figure S9 compares the HDS activities of the studied catalysts. The commercial Ni–Mo/Al2O3 catalyst showed higher activity for DBT desulfurization than the transition metal carbides and nitrides. The catalytic activities of DBT desulfurization decreased in the order NiMo/Al2O3 > Mo2C > WC > Mo2N > NbC > VC > VN > TiN (i.e., group 6 > group 5 > group 4). Regardless of catalyst, benzene was the only distinguishable HDS product of DBT. The lower HDS activities of the carbides and nitrides may attributed to blockage of the available active sites by quinolone uptake. Mohammed et al. (2015) inspected the effect of Re metal on the activities of a Ni–Mo/γ-Al2O3 catalyst for sulfur removal from atmospheric gas oil as the temperature ranged from 275 to 350 °C under a pressure of 40 bar. Decoration with Re atoms improved the desulfurization activities of the Ni–Mo/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. The nitrogen-rich MoN2 phase was found to be three times more effective in HDS reaction than the commonly utilized MoS2 catalyst (Wang et al. 2015b). With the near-absence of N vacant sites in this N-rich phase, the mechanisms of HDS action could be distinctly different from these prevailing over the γ-Mo2N surface. Our preliminary DFT calculations on HDS reactions over the MoN2 could not establish a feasible route that ensues via analogues mechanism to that established for the Mo2N surface. Thus, it will be interesting to re-visit the HDS mechanism assisted by the MoN2 surface.

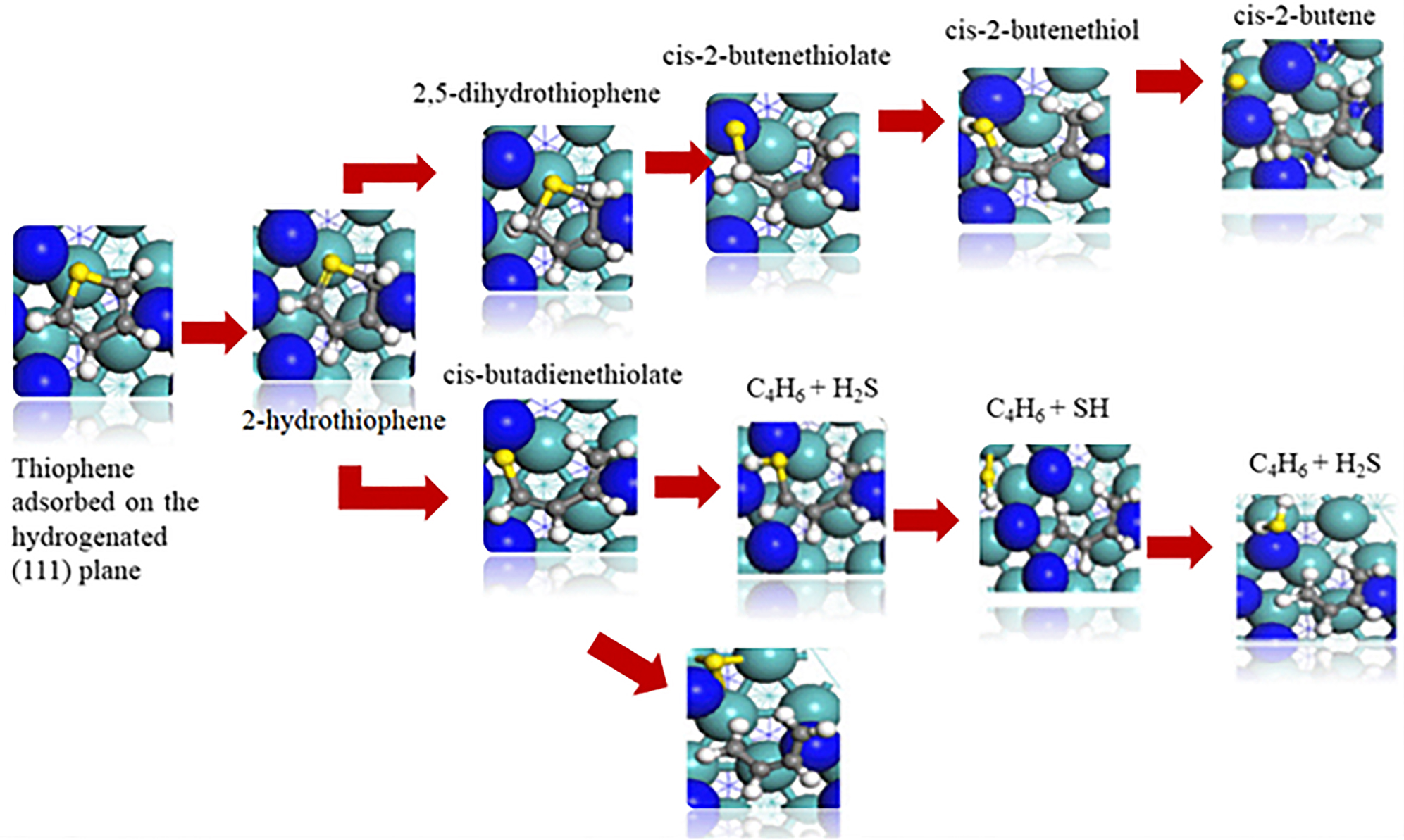

Jaf et al. (2018c) emphasized the ability of molybdenum nitride catalysts to desulfurize simple aromatic molecules such as thiophene (C4H4S). They investigated the HDS mechanism of thiophene over γ-Mo2N (111) slab by DFT. Thiophene was inferred to adsorb in a flat mode over the vacant 3-fold fcc sites. The HDS mechanism as depicted in Figure 14 ensues via complex pathways that mainly involve H transfer from the surface to the adsorbed thiophene, rupture of the C–S bond, surface hydrogenation of surface-bound S/SH adducts, and desorption of H2S and cis-2-butene. We have found that the HDS route to entail lower activation energies than direct de-sulfurization.

The proposed HDS reaction mechanism and geometries of thiophene over γ-Mo2N surface redrawn from Jaf et al. (2018c).

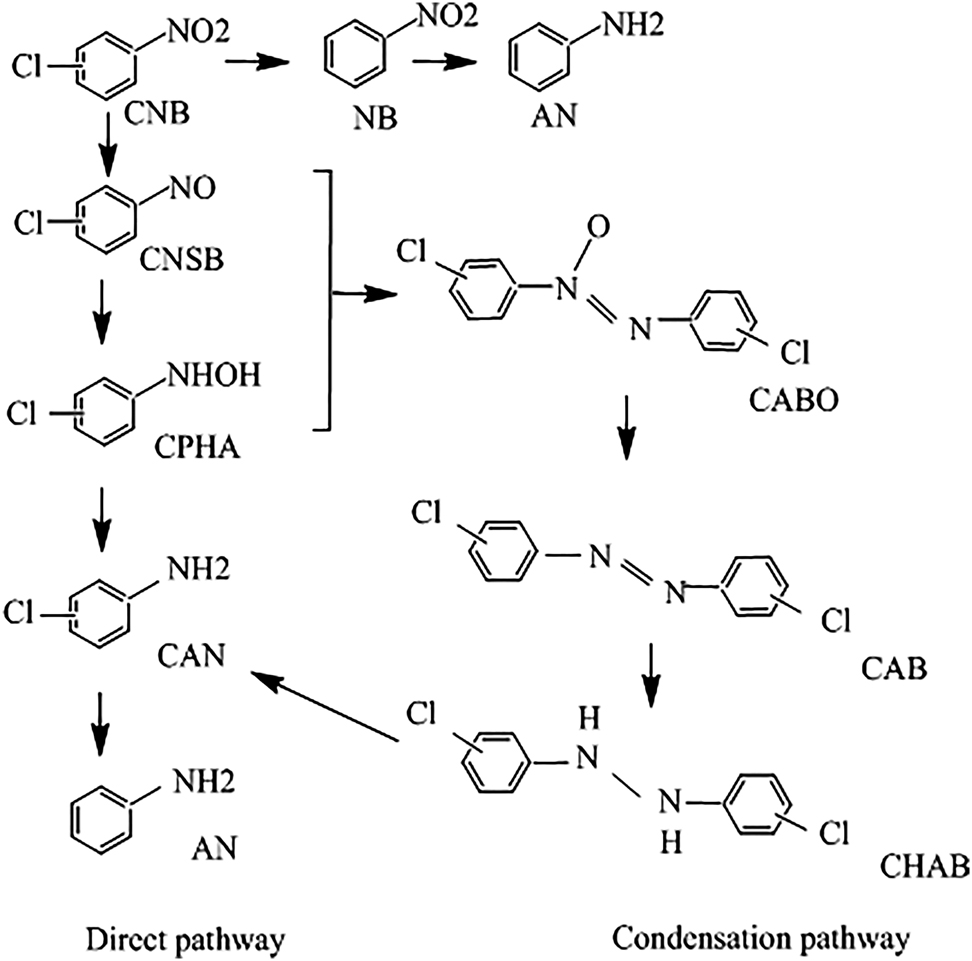

13.1.3 Hydrogenation and de-chlorination of chloroamines

Transition metal nitrides promote the production of industrially important aromatic chloroamines (Dongil 2019). This topic is gaining traction in the catalyst fields. Of particular interest is the selective hydrogenation of p-CNB to p-CAN. The latter assumes direct applications in prominent chemical industries such as pharmaceuticals, polymers and pesticides. The hydrodechlorination of p-CNB to p-CAN comprises two primary reaction routes forming several intermediates (see Figure 15) (Jaf et al. 2018a). Along the direct pathway, the HYD of p-CNB generates chloronitrosobenzene and chlorophenylhydroxylamine as reaction by-products. A further hydrogen transfer reaction yields p-CAN. This condensation pathway forms nitroso and hydroxylamine intermediates that produce several side products, such as chloroazobenzene and chlorohydrazobenzene, which are subsequently hydrogenated to p-CAN (Jaf et al. 2018a).

Reaction pathways in the hydrogenation of p-CNB to p-CAN. CNSB: chloronitrosobenzene, CPHA: chlorophenylhydroxylamine, CAB: chloroazobenzene, and CHAB: chlorohydrazobenzene, redrawn from Jaf et al. (2018a).

Several catalyst systems are selective for desired haloamines, including MgF2/Ru–Cu catalysts (Pietrowski et al. 2011), Pd catalysts (Cárdenas-Lizana et al. 2013), activated carbon-supported Pt (Pt/AC) and Fe-promoted Pt (Pt–Fe/AC) catalysts (Chen et al. 2017), Au13 and Au55 nanoclusters (Zhang et al. 2018), and Ni/TiO2 (Meng et al. 2010). Jujjuri et al. (2014) investigated the surface-mediated hydrochlorination (HDC) of 1,3-dichlorobenzene (1,3-DCB) They found that Ni/SiO2 favored the concerted removal of both Cl substituents, producing a benzene molecule. Wang et al. (2017) fabricated a nanostructured δ-MoN catalyst with an onion-like morphology for the selective hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarene compounds. Jaf et al. (2018a) reported the selectivity of the γ-Mo2N system for the HDC of aromatic molecules by probing the reduction mechanisms of p-CNB to p-CAN. Furthermore, DFT calculations of p-CNB showed a preference for two adsorption sites: Mo-hollow fcc and N-hollow hcp. The direct reduction of p-CNB to p-CAN via a chloronitrobenzene intermediate appeared to be the most preferred route. The primary steps in the constructed mechanism signifies H-transfer reactions from hollow sites to the NO/–NH groups via accessible reaction barriers followed by water elimination. Formulated thermo-kinetic model follows the reaction sequence shown in Figure 15 and elucidate the selectivity toward the hydrogenation cycle toward the experimentally observed products followed by water elimination steps. Most importantly, we have shown that direct de-chlorination through fission of the aromatic C–Cl bond to be unfeasible step. Overall, the hydrogenation of p-CNB by the Mo2N surface was comparable to that of the Pd/ZnO (Cárdenas-Lizana et al. 2013).

13.1.4 Hydrodenitrogenation (HDN)

At present, hydrogenolysis of aromatic and nonaromatic hydrocarbons is the primary strategy for producing environmentally friendly fuels with no heteroatomic contents, most notably, S and N. This strategy requires cost-effective catalysts that resist rapid activations and are catalytically efficient for HYD (Perot 1991; Rase 2016). Early studies reported the catalytic performance of high-surface-area transition metal carbides, nitrides, and borides for quinoline HDN in a batch autoclave reactor (Schlatter et al. 1988). The molybdenum carbide and nitride catalysts most effectively removed the N content from quinolone, with lower hydrogen consumption than the commercial Ni–Mo/A12O3 catalyst. The structural sensitivity (i.e., the site density n, examined via CO chemisorption) minimally affected the catalytic activity of HDN and HDS reactions. Supplementary Figure S10 compares the quinoline HDN activities of carbides and nitrides with that of NiMo/Al2O3 at 643 K and 3.1 MPa. The HDN activity of Mo2C was clearly comparable with that of a commercial NiMo/Al2O3 catalyst. The identified products of quinoline HDN were hydrogenated quinoline compounds and denitrogenated hydrocarbons (Ramanathan and Oyama 1995).

Lee et al. (1993) proposed the reaction routes of nitrogen removal from quinolone over the Mo2N surface. Quinoline HDN was highly selective for the formation of propylbenzene from 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline and disfavored the formation of propylcyclohexane from decahydroquinoline. Senzi and Lee (1998) reported the HDN capacity of indole over a Mo2N catalyst. The Mo2N exhibited higher activity toward the HDN of indole than MoNi/γ-Al2O3 and consumed less hydrogen. The major reaction products of pyridine HDN over γ-Mo2N are alkanes and pentane (Choi et al. 1992). Li et al. (1999) reported low H2 consumption and high catalytic performance (activity and selectivity) of indole over fcc-Mo2N prepared using the TPR method. They also synthesized hcp-Mo2C via a sonochemical method. It was concluded that the structure, composition, and crystallinity of the catalysts are crucial in their activity and selectivity for indole HDN.

It has conveyed that Mo2N activity greatly depends on the surface structure and availability of the active phases, which are distinguished as metallic Mo (modest-activity sites) and N deficient (high-activity sites) (Nagai 2007). Furthermore, catalytic performances of nitride catalysts for the hydrogenation reaction of carbazole HDN have been reported (Nagai et al. 2000). Nagai and Miyao (1992) demonstrated higher carbazole HDN activity in an alumina-supported molybdenum nitride catalyst than on sulfided and reduced phases at 553–633 K and 10.1 MPa total pressure. Chen et al. (2004) studied the catalytic decomposition of hydrazine (N2H4) over fresh and reduced passivated Mo2N catalysts. They suggested that N2H4 is mainly adsorbed on the Mo sites. At a nitriding temperature of 700 K or lower, hydrazine fragments into NH3 and N2. At higher temperatures, NH3 decomposes into hydrogen and nitrogen. Similar products were observed over Ir/γ-Al2O3 catalysts. Recently, Perret et al. (2019) showed contrasting effects of the Mo/N ratio on HYD and hydrogenolysis reactions. They postulated that the Mo/N ratio depends on the duration of Mo nitridation. Increasing the Mo/N ratio increased both the HYD rate of nitrobenzene with 100% selectivity to aniline and the hydrogenolysis rate of benzaldehyde to toluene.

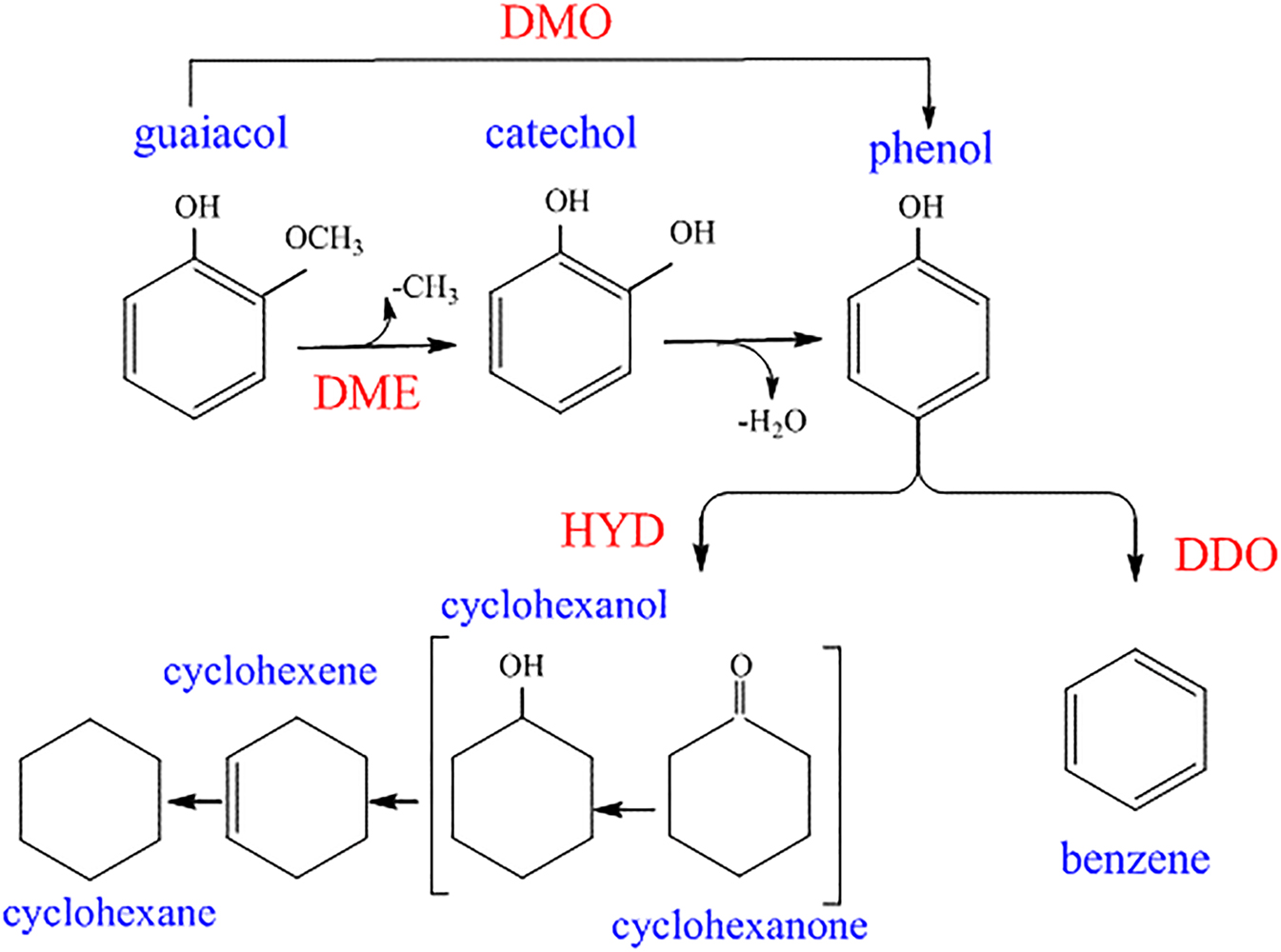

13.1.5 Hydrodeoxygenation (HDO)

The HDO reaction of oxygen-containing structural entities has been successfully implemented on commercial scales by petrochemical industries (Furimsky 2000; Şenol et al. 2005). Ghampson et al. (2012) investigated how the nitriding procedure and support affect the properties of guaiacol HDO over molybdenum nitride catalysts. The Mo–N catalyst synthesized from an N2/H2 mixture through ammonolysis routes was more active for HDO than the catalysts synthesized by other routes owing to higher dispersion of the molybdenum oxynitride phase.

In another study, the same group reported that nonpromoted Mo2N catalysts with the highest N/Mo concentration afford the maximum activity for guaiacol HDO (Ghampson et al. 2012). Furthermore, the HDO activity of guaiacol over alumina- and silica-supported molybdenum nitride catalysts was reported. The alumina-supported nitrides afforded a significant conversion of guaiacol to catechol, whereas the silica-supported catalysts achieved the highest phenol production with little catechol (Ghampson et al. 2012). Figure 16 shows the proposed reaction mechanism of guaiacol HDO over Mo2N supported on commercial activated carbons. As shown in the figure, phenol and catechol were the most abundant products (Sepúlveda et al. 2011).

Reactions of guaiacol HDO proposed by Sepúlveda et al. (2011), reproduced with permission from Elsevier.