Abstract

This study explores a brief intervention aimed at increasing bias awareness by emphasizing the personal relevance of individuals’ biases in the school context. The tendency to grade student performance differently due to unrelated student characteristics (e.g., migration background, gender) can lead to systematic disadvantages for specific students. Such biases can be compensated for by an awareness of biases. Hence, an intervention was evaluated focusing on changing general bias awareness, as well as awareness of biases related to three specific groups: female, male, and people with a migration background. In a longitudinal study, N = 191 prospective teachers were examined over three measurement points. The findings suggest that the intervention contributed to an increase in immediate bias awareness across all four facets and indicated potential follow-up effects (2 weeks) for the three specific groups. The results imply that short interventions could be effective in enhancing bias awareness and may serve as a valuable component of teacher education to help address biases in teachers’ judgments.

1 Introduction

A wide range of research has examined the influence of stereotypes on students’ educational experiences. In this context, stereotypes are understood as teachers’ assumptions about students’ abilities based on superficial characteristics, such as gender or migration background. These stereotypes can result in systematic misjudgments. Because these misjudgments are not random but occur consistently for students with specific characteristics, they are referred to as biases in the following. Teachers’ actions and teacher-student interactions play a pivotal role, and are often shaped by stereotypical assumptions, leading to far-reaching consequences for students. For example, research indicates that teacher evaluations are influenced not only by student performance but also by other factors such as migration background, socioeconomic status, and gender (Glock, 2016; Holder & Kessels, 2017; Tobisch & Dresel, 2017). Studies have consistently shown that students with a migration background are more likely to receive lower performance assessments and grades than their peers without such a background, even when their actual performance is comparable (Bonefeld & Dickhäuser, 2018; Glock et al., 2013; Kleen & Glock, 2018). Gender-based stereotypes also affect teacher judgments; for instance, girls’ performance in mathematics is often rated lower than that of boys, despite equal achievement levels (Holder & Kessels, 2017). Crucially, these disparities in educational outcomes cannot be attributed solely to differences in student performance, underscoring the significant role of teacher biases (Bonefeld et al., 2017).

Given these findings, it is important to note that stereotypes are generalized attributions made about social groups that arise naturally as part of human social cognition. They help to reduce the complexity of social information processing by enabling quicker judgments and decisions. However, while stereotypes can sometimes be accurate, they often involve overgeneralizations: These overgeneralizations can shape negative affective responses (e.g., prejudice) and lead to systematic behavioral patterns, i.e., biased behaviors against specific groups (e.g., discrimination). This theoretical perspective, as described in the three-component model of attitudes (Rosenberg, 1960), highlights the need to address stereotypes in the school context to prevent their adverse effects on teacher judgments and student outcomes. The role of teachers in perpetuating or mitigating educational disadvantages has been widely discussed (e.g., Jussim & Harber, 2005; McKown & Weinstein, 2008). These discussions emphasize the need to address stereotypes in the school context to prevent their adverse effects on teacher judgments and student outcomes. While the impact of stereotypes on educational disadvantages is well-documented, relatively little attention has been paid to strategies for reducing related biases. However, existing research suggests that increasing awareness of one’s own biased behaviors may help mitigate the influence of stereotypes over time (Burns et al., 2017). In other words, being aware of the existence of stereotypes can reduce the likelihood of enacting them through biased behavioral patterns. For example, studies have demonstrated that interventions aimed at increasing bias awareness can effectively reduce stereotypical thinking and its impact on judgments (Grube et al., 1994; Monteith, 1993; Monteith et al., 2010a, b; Moskowitz et al., 2011; Penner, 1971; Rokeach & Cochkane, 1972). The present study builds on these insights by evaluating an intervention designed to enhance teachers’ awareness of their biases, as a first step toward the broader goal of reducing stereotype-based educational misjudgments.

2 Theory

2.1 Attitudes: Stereotypes, Prejudices, and Bias

In social psychology, the terms stereotypes, prejudices, and bias describe related but distinct aspects of how people perceive and evaluate others based on social group membership. From the perspective of the three-component model of attitudes (Rosenberg & Hovland, 1960), stereotypes represent the cognitive component (beliefs), prejudices the affective component (feelings), and bias often reflects the behavioral component (actions or tendencies). Together, they contribute to anoverall evaluative attitude toward social groups, though not all components are inherently evaluative. Understanding the differences between these concepts is crucial for clarifying their roles in social cognition and behavior. Stereotypes are generalized cognitive beliefs or assumptions about the traits, behaviors, or characteristics of members of particular social groups (e.g., Bourne & Ekstrand, 1992; Fiske & Tablante, 2015). They serve as mental shortcuts to simplify social information processing by categorizing individuals, thereby reducing complexity and helping to anticipate social interactions (Lippmann, 1922; Strasser, 2012). However, stereotypes often ignore individual variability and can become rigid and resistant to change (Strasser, 2012). While they may contain an evaluative component, stereotypes do not necessarily involve affective responses. Prejudices are evaluative attitudes, often negative, toward individuals based on their group membership (Allport et al., 1954; Fiske & Tablante, 2015). While prejudices reflect emotional responses toward a group, stereotypes are generalized beliefs that may influence perceptions and judgments without necessarily involving personal feelings or direct experience (Allport et al., 1954; Fiske & Tablante, 2015). The concept of bias is more complex and has been interpreted in different ways. According to Gawronski et al. (2022), bias should be understood primarily as a behavioral component – that is, a reaction or response triggered by social cues. This means that bias is not something one “has” as a static mental representation (unlike stereotypes or prejudices, which are cognitive and affective components), but rather a manifestation in behavior influenced by these underlying processes. This behavioral perspective highlights that bias reflects how stereotypes and prejudices may translate into actions or judgments, sometimes without conscious intention. Consequently, biases influence social interactions and decisions in subtle yet significant ways (De Houwer, 2019; Schwarz, 2015; Vuletich & Payne, 2019). It is important to note that stereotypes, prejudices, and biases can manifest both explicitly (consciously) and implicitly (unconsciously; De Houwer, 2019; Schwarz, 2015; Vuletich & Payne, 2019). Research indicates that while explicit manifestations have declined in recent decades, implicit manifestations persist more stubbornly, continuing to affect across many social domains (Charlesworth et al., 2023; Charlesworth & Banaji, 2022). Finally, bias awareness – the capacity to recognize and critically reflect on one’s own behavioral biases based on the underlying stereotypes and prejudices – is a critical step in reducing their negative impact on social judgments and interactions (Perry et al., 2015). In summary, stereotypes and prejudices serve as cognitive and affective foundations, while bias represents the behavioral expression of these underlying processes. Understanding these distinctions is essential for developing targeted interventions to reduce discrimination and promote equitable social outcomes.

2.2 Awareness as a Mechanism to Reduce Biases Based on Stereotypes and Prejudices

Numerous studies have sought to reduce biases in judgment and to counteract the disadvantages these biases produce for marginalized groups (Lai et al., 2016). However, a definitive solution remains elusive. A common approach involves interventions that aim to dismantle stereotypes and reduce their influence on perception and judgment. For example, brief science-based online diversity training in workplace settings has been shown to lead to changes in attitudes and, in some subgroups, modest behavioral shifts, but its effects are often limited and insufficient as stand-alone solutions for promoting equality (Chang et al., 2019). Many of these interventions focus on increasing awareness, either by emphasizing contextual factors, providing guidelines for intergroup interactions (Hill & Augoustinos, 2001; Stephan & Stephan, 2001), or facilitating reflection processes (Brookfield, 2017). Yet, because stereotypes and prejudices are often activated automatically and unconsciously (Devine, 1989), increasing deliberate awareness of these internalized attitudes, i.e., bias awareness, is essential for mitigating their potential influence on judgments and behavior In this context, awareness of personal bias – meaning the individual recognition of one’s own stereotypes and prejudices – plays a particularly crucial role. Research has shown that bias awareness, defined as the sensitivity to and recognition of one’s own stereotypes and prejudices, varies considerably among individuals (Perry et al., 2019; Perry et al., 2015). Individuals with greater bias awareness are more likely to view feedback about their biases as credible and to take corrective actions (Perry et al., 2015). This form of personal insight is therefore a key factor in long-term behavioral change. One promising strategy is the “habit-breaking” approach, which treats implicit bias as a habit that can be disrupted through a combination of awareness, concern, and intentional behavioral strategies. For example, Devine et al. (2012) showed in a 12-week longitudinal study that participants who underwent such an intervention demonstrated significant and long-term reductions in implicit racial bias, particularly when they expressed concern about discrimination and actively applied the suggested strategies.

Another example is the study of Rokeach and Cochkane (1972), who demonstrated that highlighting contradictions between individuals’ values of equality and their racially biased attitudes led to significant reductions in prejudice – effects that persisted several weeks post-intervention (Grube et al., 1994). Similarly, studies have found that when White participants were made aware of their prejudice or when egalitarian values were activated, they tended to adjust their behavior accordingly (Monteith, 1993; Moskowitz & Li, 2011). However, individuals who are unaware of their biases are less likely to engage in change, underscoring the need to strengthen this awareness – especially in educational settings where teacher expectations can influence student outcomes. It is also important to distinguish bias awareness from other constructs, such as egalitarian motivation. While some individuals show strong efforts to be unbiased (Devine et al., 2002; Plant & Devine, 1998), even in the absence of strong bias awareness, the combination of both appears to be most effective. Notably, much of the empirical basis for this comes from US-based research, particularly on White-Black dynamics, and may need contextual adaptation when applied to other social groups or regions. Furthermore, individuals with high bias awareness tend to be more perceptive of subtle cues in their environment, indicating biased behavior, including in educational settings (Perry et al., 2015). This enhances their ability not only to reflect on their own actions but also to identify and respond to bias in others, making bias awareness a key target for intervention in professional training and teacher education.

2.3 Attribution Theory, Emotional Responses, and Individual Differences in Bias Awareness

The process of becoming aware of one’s own biases is often accompanied by a range of emotional responses, which can significantly influence individuals’ receptiveness to feedback and motivation for change. Weiner’s (1985) attribution theory offers a useful framework for understanding these responses. According to this theory, the emotional reaction to bias recognition depends on whether individuals attribute their biased behaviors to internal, controllable factors (such as personal responsibility) or to external, uncontrollable factors (such as societal norms). When individuals see their bias as controllable, they may experience guilt – a constructive emotion that can motivate efforts to change (Hofer & Waag, 2020). However, guilt is not a universal response. People with deeply ingrained biases may instead respond defensively or with anger, particularly if feedback threatens their self-concept (Perry et al., 2015).

Implicit bias is not always distressing or surprising. While some individuals feel guilt when confronted with their biases, others – especially those with lower bias awareness – may experience little or no emotional discomfort (Monteith & Voils, 1998). The acceptance of feedback about implicit biases varies according to prior attitudes and sensitivity to bias. Perry et al. (2015) emphasize that feedback is most effective when recipients are already aware of and motivated to address their biases, while it may provoke denial or resistance in those lacking such awareness.

These emotional and cognitive processes are closely linked to the motivation to change, which is central for effective bias reduction. Awareness alone is insufficient; it must be accompanied by motivation and personal commitment to translate into behavioral change.

2.4 Models of Prejudice Self-Regulation

In addition to awareness, self-regulatory strategies such as retrospective reflection can help individuals develop internal inhibition mechanisms against stereotypes (Monteith et al., 2010a; Moskowitz & Ignarri, 2009).

Theoretical models on self-regulation of prejudice stress the importance of discrepancy awareness – the recognition of a conflict between egalitarian values and biased behaviors (Monteith, 1993; Monteith et al., 2010a). Individuals with lower levels of prejudice who recognize such conflicts tend to experience guilt, which triggers reflection and compensatory behavior. Conversely, highly biased individuals often react with defensiveness or externalize blame, resulting in fewer adjustments.

Thus, both awareness and motivation to change are prerequisites for successful self-regulation. Research further shows that deeply held stereotypes are particularly resistant to change (Kumar et al., 2022), underscoring the importance of interventions that promote ongoing reflection and sustained personal commitment.

2.5 Implications for Bias Reduction Interventions

Awareness of one’s own biases is a significant predictor of increased intergroup empathy and reduced prejudice (Monteith et al., 2010a; Nelson et al., 2012; Ozier et al., 2019). This form of personal awareness is associated with the ability to internalize feedback about one’s own biases and to recognize that even subtle (rather than solely overt) biased behaviors, such as microaggressions, avoidance, or nonverbal cues, can reflect underlying prejudice (Perry et al., 2015). Previous research highlights the pivotal importance of recognizing one’s own biases (Perry et al., 2015). Based on the theoretical frameworks and empirical findings presented, it can be concluded that awareness of personal biases is a fundamental prerequisite for the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing them. Such awareness enables individuals to personally relate to the topics discussed, fostering sensitivity to their own biases and facilitating the adoption of self-regulatory measures to address them.

The current paper aims to build on these insights by testing the efficacy of an intervention designed to increase individual awareness of biases and provide a foundation for sustained reductions in stereotype influence. By addressing individual differences in bias awareness, this research seeks to advance understanding of how to create effective, lasting change in attitudes.

2.6 Intervention to Increase Bias Awareness

The AHA Intervention[1] is grounded in key insights from social-cognitive theories, particularly models of attitude change (e.g., Petty & Cacioppo’s Elaboration Likelihood Model, 1986) and dual-process theories of social information processing (e.g., Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). These frameworks posit that individuals form and revise attitudes and judgments through both automatic and reflective processes. The intervention was designed to activate reflective (systematic) processing to challenge automatic, biased thinking. The AHA Intervention is delivered in a single 90-min session and combines informational input with interactive, reflective elements to promote engagement and personal relevance. It is structured around a sequence of carefully aligned phases that integrate the key components of content, relevance, and surprising moments into a cohesive learning experience. Research shows that reflection is most likely when individuals encounter personally relevant, emotionally salient, and surprising information, leading to denial, assimilation, or accommodation (Boud & Walker, 1998; Brookfield, 2017). The AHA Intervention builds on this by intentionally triggering cognitive dissonance and schema conflict through carefully chosen tasks and examples. The three core components of the intervention are: (1) creating surprising moments, (2) emphasizing the controllability and changeability of biased thinking, and (3) reinforcing the personal relevance and importance of the content.

2.7 Theoretical Foundation and Intervention Components

2.7.1 Knowledge Transfer and Cognitive Processing

The intervention begins with foundational knowledge about judgment formation and the role of dual processing-introducing participants to the distinction between automatic (heuristic) and controlled (systematic) thinking (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). This aligns with social information processing models, which highlight how we often operate automatically, without conscious intent. Participants learn that biases are not inherently signs of bad character, but rather the result of cognitive shortcuts that can lead to systematic errors. The inclusion of heuristics and confirmation bias serves to illustrate the generality of biased thinking beyond intergroup contexts. These examples provide a low-threat entry point that helps participants understand bias as a universal cognitive phenomenon, which can then be applied to social judgments. This theoretical grounding helps reduce resistance and shame, setting the stage for deeper reflection on socially sensitive topics such as stereotypes and prejudices toward marginalized groups.

2.7.2 Surprising Moments

Based on reflection theory and theories of conceptual change, the intervention incorporates tasks that create “AHA moments,” meaning instances that provoke schema disruption. Examples include classic demonstrations of cognitive and stereotype-driven misjudgments. For example, participants are presented with tasks adapted from research on judgment heuristics (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1973, 1981), gender stereotypes (e.g., Stoeger et al., 2004), and confirmation bias (e.g., Wason, 1960) to illustrate how biased thinking can emerge in everyday decision-making and social judgments. These moments are designed to foster accommodative processing (Hofer & Waag, 2020; Weiner, 1985), where participants revise existing mental models rather than assimilate new information into old patterns. Research suggests that such reflection is most likely to occur when individuals encounter surprising and personally significant events (Boud & Walker, 1998; Brookfield, 2017; Schön, 1991). Responses to these events – denial, assimilation, or accommodation – depend on how individuals attribute the causes of the experience. Denial involves rejecting or avoiding the situation to protect one’s self-concept and can hinder learning. Assimilation allows individuals to maintain existing beliefs by minimally adapting them, whereas accommodation requires a more fundamental restructuring of mental schemas and is thus most desirable for lasting change (Hofer & Waag, 2020). Accommodation is particularly likely when the surprising event is perceived as important, self-relevant, and controllable (Weiner, 1985). Although this may elicit discomfort or guilt, perceiving the situation as changeable enhances motivation for future-oriented learning and self-regulation. By deliberately structuring surprising moments to be both personally relevant and framed as controllable (see below), the AHA Intervention encourages not only awareness of bias but also the motivation to change biased behavior. These reflective triggers, coupled with emotional salience and guided attribution, aim to prevent defensive reactions and foster constructive, deeper-level learning.

2.7.3 Controllability and Changeability

Drawing from attribution theory and models of self-regulation, the intervention emphasizes that while biases may arise automatically, individuals can learn to regulate their effects. This focus helps participants move from denial or defensiveness to constructive engagement by reinforcing a sense of agency. By normalizing the presence of bias and offering strategies to recognize and counteract it, the intervention aims to foster motivation for long-term change. While concrete behavioral strategies (e.g., structured evaluation tools) are only briefly introduced at this stage, the intervention lays the necessary groundwork by fostering awareness and motivation to change, which are key prerequisites for more targeted bias-reduction techniques.

2.7.4 Relevance and Contextualization

To maximize relevance, all materials are contextualized to everyday scenarios. Research findings on judgment heuristics and their real-world consequences (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1973, 1981) are presented alongside experimental studies that highlight the impact of biases on students. The inclusion of examples relevant to the participants’ context, such as their role as student teachers, reinforces the personal significance of the content and supports meaningful engagement. Besides everyday examples, the intervention includes examples related to both gender and migration background, drawn from empirical research on biased teacher judgments (e.g., Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013). These examples highlight how stereotypes can influence teacher expectations, assessment, and behavior toward students. The inclusion of examples relevant to the participants’ context, such as their role as student teachers, reinforces the personal significance of the content and supports meaningful engagement.

2.8 Study Goal and Hypotheses

The present study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a targeted intervention designed to enhance bias awareness among pre-service teachers. Specifically, it seeks to investigate whether a brief intervention can not only increase general bias awareness but also address biases related to two critical domains: migration background and gender (binary: women/men). These domains were chosen because previous research has consistently demonstrated their significant influence on teacher judgments and actions in educational contexts. By focusing on these areas, the study aims to investigate how bias awareness can be increased in pre-service teachers. This is an important prerequisite for reducing stereotype-based misjudgments in educational practice. Building on this foundation, the study addresses several key research questions:

Can the bias awareness of pre-service teachers be effectively increased through a short intervention?

Are the effects of the intervention sustained over time?

Does the impact of the intervention depend on the initial level of bias awareness in participants?

By answering these questions, the present study aims to contribute to both the theoretical understanding of bias awareness and the practical development of interventions that promote equitable teacher judgments and actions.

The combination of imparting knowledge about the unconscious influence of judgments and actions through stereotypes, with the initiation of reflection processes about one’s own (unconscious) stereotypes and prejudices, should lead to an increase in one’s own bias awareness. After the intervention, both the general bias awareness (Hypothesis 1) and the bias awareness of bias against people with a migration background (Hypothesis 2), against women (Hypothesis 3), and also against men (Hypothesis 4) should be increased. The extent to which these effects are sustainable over a period of 2–3 weeks is being explored. Furthermore, we explore whether people with a higher initial bias awareness will benefit more than people with a lower initial bias awareness, or whether people with a lower initial bias awareness benefit more. The former is conceivable, as individuals who are already open to reflecting on their biases may potentially benefit more from the intervention in line with assumptions about bias awareness. However, it is equally conceivable that they have a comparatively lower potential to further increase their bias awareness compared to individuals whose bias awareness is still less developed.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Study Design

All participants took part in the intervention with three measurement time points; there was no control group. The first measurement took place the day before the intervention and indicates the original participants’ bias awareness. The second measurement followed immediately after the intervention and should show the direct effect of the intervention on bias awareness. The third measurement was 12–35 days (M = 16.9, SD = 3.4) after the intervention and should indicate a follow-up effect of the intervention.

3.2 Participants

All participants were students of a German university and could earn participation credits, which they were required to complete as part of their study program. The sample at the first measurement includes N T1 = 320 student teachers. The dropout rate of the second measurement was 30 participants, resulting in N T2 = 290. The sample at the third measurement was reduced by further 99 participants. The final sample for all analyses consists of N = 191 participants (128 females, 62 males, 1 diverse) with a mean age of M = 21.46 years (SD = 3.12 years). The youngest participant was 18 years old, and the oldest was 41 years old. Twelve participants had a migration background. The mean number of semesters was M = 3.49 (SD = 3.04), ranging from 1 to 18 semesters. Nine participants provided no information about their number of semesters.

3.3 Materials

Bias awareness. To measure bias awareness, an adapted version of the scale by Perry et al. (2015) was used (Fehringer et al., 2025). This scale captures an individual’s perception of their own subtle biases. Moreover, the scale also accounts for concern about own biases. Originally, the scale was created to assess Whites’ perceptions of their own subtle biases toward Blacks in the United States. The scale consists of four items (Table 1), which can be answered on a 7-point Likert scale from “do not agree at all” to “agree completely.”

German bias awareness scale with English translation in brackets

| Item | German [English translation] |

|---|---|

| 1 | Obwohl ich weiß, dass es nicht angebracht ist, habe ich manchmal das Gefühl, dass ich unbewusst eine negative Einstellung gegenüber Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund habe [Even though I know it’s not appropriate, I sometimes feel that I hold unconscious negative attitudes toward people with migration background] |

| 2 | Wenn ich mit Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund spreche, mache ich mir manchmal Sorgen, dass ich mich ungewollt voreingenommen verhalte [When talking to people with migration background, I sometimes worry that I am unintentionally acting in a prejudiced way] |

| 3 | Auch wenn ich Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund mag, mache ich mir Sorgen, dass ich unbewusste Vorurteile gegenüber Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund habe [Even though I like people with migration background, I still worry that I have unconscious biases toward people with migration background] |

| 4 | Ich mache mir nie Sorgen, dass ich mich Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund gegenüber auf subtile Weise voreingenommen verhalten könnte.” (reverse-coded) [I never worry that I may be acting in a subtly prejudiced way toward people with migration background. (reverse-coded)] |

Note: There were four versions of the scale referring to four different groups. The presented items refer to people with a migration background. The other groups are females (“people with migration background” is replaced by “women”), males (replaced by “men”), and all people (replaced by “some people”).

In this study, the scale was translated into German and adapted to the German context by speaking of people with a migration background instead of Black people (Table 1, t1: Cronbach’s α = 0.84, t2: Cronbach’s α = 0.81, t3: Cronbach’s α = 0.83). In addition, other variants were developed based on the original scale and used in this study. On the one hand, the general bias awareness was recorded (Table 1, t1: Cronbach’s α = 0.81, t2: Cronbach’s α = 0.79, t3: Cronbach’s α = 0.79) and bias awareness of gender prejudices (Table 1, against women, 4 items, t1: Cronbach’s α = 0.81, t2: Cronbach’s α = 0.77, t3: Cronbach’s α = 0.80, and against men, 4 items, t1: Cronbach’s α = 0.80, t2: Cronbach’s α = 0.78, t3: Cronbach’s α = 0.81). To capture the complexity of bias awareness across different social groups, we assessed bias awareness separately for women and men, as gender-related biases can vary depending on context and target group.[2] For the migration background, a broader category was used to avoid excessive fragmentation.[3] Additionally, a general bias awareness scale was included to measure participants’ overall sensitivity to biases beyond specific social categories. This approach allowed us to examine both specific and general aspects of bias awareness relevant to the school context.

3.4 Procedure

As part of the present study, prospective teachers were asked about their own biases. On the one hand, the awareness of the influence of stereotypes and prejudices, in general, was measured, and, more precisely, the influence in relation to stereotypes and prejudices against people with a migration background or according to gender. The order of these four scales was the same for each participant: (1) General, (2) Migration Background, (3) Female, and (4) Male. In addition, a short intervention was conducted aimed at raising awareness of one’s own biases. To evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, a survey design with three measurement times (a pre-measurement, a post-measurement directly after the intervention, and a post-measurement about 14 days after the intervention) was chosen. Student teachers were invited via a university mailing list and social media to participate in this study. After prior registration for the desired dates for a 90-min input session (the short intervention), the link to the first survey was sent to the participants. The input part took place 1–3 days after the first survey (t1) digitally via Zoom (cloud-based video conference service). Immediately after the input part, the students conducted the first follow-up survey (t2). After 10 days, the participants were asked by email to participate in another follow-up survey (t3). Both the pre-measurement (pre-survey before the intervention) and the post-measurements took about 15 min and were carried out using an online questionnaire in the UNIPARK survey software.

The timeline of the intervention study was as follows:

Preliminary survey of 15 min (1–3 days before the intervention)

1 × 90 min input session via Zoom (intervention)

Follow-up survey of 15 min (immediately after the intervention)

Follow-up survey 2 of 15 min (approx. 14 days later)

Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

3.5 Analyses

Before the hypotheses were tested, a dropout analysis was conducted by four repeated measurement analyses of variance (ANOVAs), one for each bias awareness variable (i.e., general, migration background, female, male). These ANOVAs compared the two dropout groups, after the first and second measurements, as well as the group that finished the third measurement. The considered variable was always from the first measurement.

The effectiveness of the intervention (Hypotheses 1–4) was examined using repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs), conducted separately for each of the four BA scales comparing the three measurements and controlling for gender and migration background. The follow-up analyses contrast the first measurement (before the intervention) against both measurements after the intervention as well as consider all three pairwise post hoc comparisons, i.e., between the first and the second as well as the third measurement and between the second and the third measurement. The sustainability of the effects over a period of 2–3 weeks was exploratively analyzed by the post hoc comparisons between the first and the third measurement. The second explorative analysis considers the influence of the initial bias awareness on the effects and was analyzed for each BA scale by linear regression analyses. Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals for the coefficients were estimated using bootstrapping. All statistics were performed using R statistics, version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021), using the package afex, version 1.3.0 (Singmann et al., 2023), emmeans, version 1.8.7 (Lenth et al., 2023), psych, version 2.1.9 (Revelle, 2021), and boot, version 1.3-28 (Canty et al., 2021).

4 Results

The dropout analyses revealed no differences between both dropout groups (after the first and the second measurement) and the final group with respect to age, bias awareness toward people with a migration background, females, and males, F(2, 317) ≤ 1.568, p ≥ 0.210. Although there were differences in the general bias awareness between the three groups, F(2, 317) = 3.246, p = 0.040, the post hoc comparisons showed only marginal differences between the first and the second dropout group, t(317) = 2.128, p = 0.086, as well as between the final and the second dropout group, t(317) = 2.123, p = 0.087. The first dropout group and the final group were comparable, t(317) = 0.919, p = 0.628. The planned contrast between both dropout groups on the one hand and the final sample on the other hand showed no differences, t(317) = 0.324, p = 0.746. Therefore, all analyses are based on the final sample with N = 191 participants.

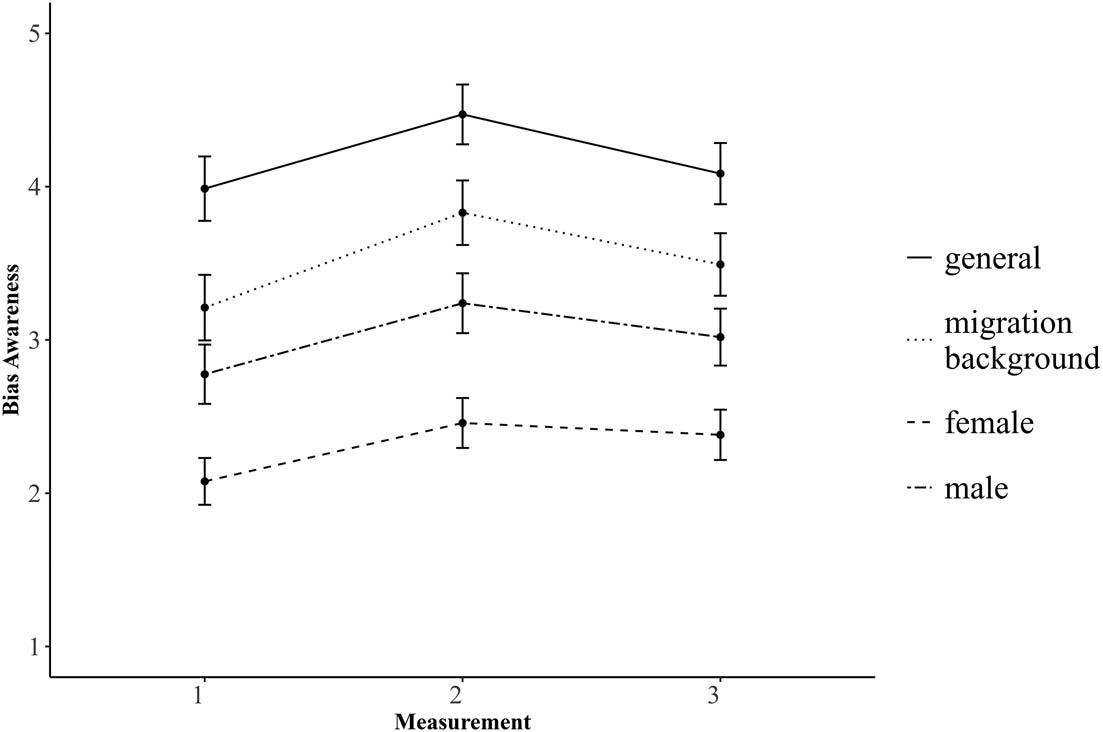

The descriptive results (Table 2) show skewness and kurtosis of all variables at all measurement time points in the acceptable range between −1 and 1. Only the bias awareness for biases against females at the first measurement and the difference in the bias awareness for biases against males between the second and third measurements have higher values. The mean and standard deviations indicate that no ceiling and floor effects occur at any measurement time point. Figure 1 shows the immediate effect as well as the resulting bias awareness at T3.

Descriptive statistics

| M | SD | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA (general) | T1 | 3.99 | 1.48 | 1 to 7 | −0.15 | −0.73 |

| T2 | 4.47 | 1.38 | 1 to 7 | −0.33 | −0.76 | |

| T3 | 4.09 | 1.41 | 1 to 7 | −0.10 | −0.75 | |

| T3–T2 | −0.39 | 1.01 | −3.50 to 2.00 | −0.66 | 0.53 | |

| BA (migration background) | T1 | 3.21 | 1.51 | 1 to 7 | 0.26 | −0.93 |

| T2 | 3.83 | 1.48 | 1 to 7 | −0.11 | −0.82 | |

| T3 | 3.49 | 1.44 | 1 to 7 | 0.13 | −0.83 | |

| T3–T2 | −0.34 | 1.03 | −4.00 to 1.75 | −0.34 | 0.68 | |

| BA (female) | T1 | 2.08 | 1.08 | 1 to 6.00 | 1.16 | 1.59 |

| T2 | 2.46 | 1.15 | 1 to 5.50 | 0.69 | −0.01 | |

| T3 | 2.38 | 1.16 | 1 to 5.75 | 0.65 | −0.11 | |

| T3–T2 | −0.08 | 1.00 | −3.75 to 2.50 | −0.37 | 0.77 | |

| BA (male) | T1 | 2.78 | 1.36 | 1 to 7 | 0.61 | −0.01 |

| T2 | 3.24 | 1.38 | 1 to 7 | 0.35 | −0.40 | |

| T3 | 3.02 | 1.31 | 1 to 7 | 0.45 | 0.02 | |

| T3–T2 | −0.22 | 1.03 | −4.50 to 2.00 | −1.16 | 2.98 |

Changes of each BA scale over the three measurements, including the 95% confidence interval.

The correlations between the four scales at the first measurement are all positive and significant, p < 0.001. The BA scales general and migration background have the highest correlation with r = 0.71. All other correlations are between 0.34 ≤ r ≤ 0.46.

4.1 Bias Awareness (General)

The ANCOVA showed a significant difference between all three measurements, F(2, 380) = 19.01, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02, and a significant contrast between the first measurement and both measurements after the intervention, t(380) = 4.05, p < 0.001 (Hypothesis 1). However, only the post hoc test between the first and the second measurement revealed a significantly increased bias awareness, t(380) = 5.83, p < 0.001. The follow-up effect between the first and the third measurement was not significant, t(380) = 1.18, p = 0.465. The post hoc comparison between the second and third measurement confirmed a significant decrease in BAS values, t(380) = 4.65, p < 0.001 (see also Figure 1).

The linear regression model demonstrates a negative relationship between the initial BAS value before the intervention and the increasing effect of the intervention measured as the increase from the first measurement to the second measurement, b = −0.36 [−0.47; −0.26], t(189) = 7.33, p < 0.001, adj. R 2 = 0.22.

4.2 Bias Awareness (Migration Background)

According to Hypothesis 2, the BA scale for migration background differed between the three measurements, F(2, 380) = 32.64, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.03, with a significant increase from the first measurement to the second and third measurement combined, t(380) = 6.78, p < 0.001. There was a significant increase from the first to the second measurement, t(380) = 8.07, p < 0.001, and contrary to the general scale of the BA, there was also a significant increase from the first to the third measurement, t(380) = 3.67, p < 0.001. However, similar to BA (general), there was a significant decrease from the second to the third measurement, t(380) = 4.40, p < 0.001 (see also Figure 1).

There was a significant negative relationship between the initial BAS values (at the first measurement) and the effect of the intervention (from the first to the second measurement), b = −0.28 [−0.38; −0.18], t(189) = 5.68, p < 0.001, adj. R 2 = 0.14.

4.3 Bias Awareness (Female)

Hypothesis 3 could also be confirmed for the BA (female) scale. The ANCOVA showed significant differences between the three measurements, F(2, 380) = 14.35, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02, and a significant contrast between the first measurement and both measurements after the intervention, t(380) = 5.26, p < 0.001. Also, both post hoc tests comparing the first measurement with the second and third measurements, respectively, were significant, t(380) = 5.07, p < 0.001, and t(380) = 4.04, p < 0.001, indicating an increase from the first measurement. In contrast to BA (general/migration), the level stayed similar from the second to third measurement, t(380) = 1.03, p = 0.560 (see also Figure 1).

This BA-scale showed the descriptively largest negative relationship between the first measurement and the effect (from the first to the second measurement, Hypothesis 2), b = −0.49 [−0.63; −0.36], t(189) = 7.24, p < 0.001, adj. R 2 = 0.21.

4.4 Bias Awareness (Male)

Similarly to the other scales, Hypothesis 4 could be confirmed with a significant ANCOVA, F(2, 380) = 17.14, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02, and a significant contrast between the first measurement and the second and third measurement, t(380) = 5.15, p < 0.001. Also, both post hoc comparisons between the first and each of the other measurements were significant, t(380) = 5.85, p < 0.001 (with the second measurement), and t(380) = 3.06, p = 0.007 (with the third measurement), indicating an increase from the first measurement. In contrast to BA (female), there was a significant decrease from the second to the third measurement, t(380) = 2.79, p = 0.015 (see also Figure 1).

Also, there was a significant negative relationship between the initial BAS values at the first measurement and the effect (increase from the first to the second measurement, Hypothesis 2), b = −0.33 [−0.44; −0.23], t(189) = 5.95, p < 0.001, adj. R 2 = 0.15.

5 Discussion

The central aim of this study was to examine whether a brief intervention can enhance prospective teachers’ awareness of their own biases. To this end, we investigated changes in bias awareness across three measurement points: before the intervention (pre-measurement), immediately after the intervention (first post-measurement), and several weeks later (second post-measurement) to assess the stability of the effects over time. The intervention was theory-based and specifically aimed at increasing bias awareness in prospective teachers by normalizing the occurrence of biases and highlighting the importance of recognizing and understanding one’s own biases as a prerequisite for reflective and equitable teaching. By doing so, the study sought to provide a nuanced understanding of how such awareness can be effectively promoted and sustained in teacher education.

It was found that bias awareness of prospective teachers was significantly higher immediately after the intervention than before the intervention. All measures recorded – be it measures of general bias awareness or measures of bias awareness in relation to bias towards people with a migration background and towards female as well as male gender – showed significantly higher bias awareness after the intervention compared to bias awareness before the intervention. The second post-measurement from the intervention revealed a mixed pattern of findings depending on the content area. Only the bias awareness regarding biases against women remained at a stable level between the two post-measurements, with a significant increase in bias awareness compared to the pre-measurement. Bias awareness in relation to biases against people with a migration background and men, however, decreased significantly from the measurement immediately after the intervention to the post-measurement, but remained at a significantly higher level compared to the pre-measurement. The general bias awareness even fell to the baseline level. How can the differential findings for the various groups be explained? Firstly, the intervention included specific examples and materials, of which the initial surprising event focused on gender-related stereotypes, particularly concerning women. This emphasis might have led participants to perceive this topic as especially relevant and personally meaningful, fostering more sustained reflection and awareness. Secondly, the baseline bias awareness toward women at the first measurement (T1) was comparatively lower than for other groups, potentially allowing for greater room for improvement. In contrast, the relatively higher initial bias awareness regarding migration background and men might have led to a ceiling effect, limiting the stability of the intervention’s impact in these areas. It is also conceivable that participants believed they were less influenced by gender stereotypes due to societal changes, but through the intervention, they became aware that these stereotypes still affect them. This could explain the relatively lower bias awareness toward women at T1 and the comparatively stronger increase at T2 and T3.

The fact that the bias awareness fell in terms of the general bias awareness and the one regarding migration background and men underlines the need for ongoing opportunities for reflection and impulses for reflection in teacher training and further education. Selective interventions such as this brief intervention can increase bias awareness and sensitize people to the issue of unconscious bias. The fact that there were signs of a decrease in the effects at the second post-measurement indicates that the content of the intervention and the personal relevance of unconscious biases can be triggered by the brief intervention in the short term, but that a refresher is necessary for the purpose of ongoing reflection processes. This is in line with findings from previous research, which shows that even one-off interventions that can target judgment and decision-making can have an impact over weeks and months (Morewedge et al., 2015), but that refreshers are necessary for effects that go beyond this (Lai et al., 2016).

Repeated opportunities for reflection over a longer period of time might achieve long-term effects on the judgments and behaviors of teachers (Devine et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2009). Considering that stereotypes are deeply ingrained through years of socialization, it is unlikely that a single short intervention can sustainably alter them. Booster sessions, which periodically revisit and reinforce the topic, may be necessary to maintain and deepen the changes over time. Although the idea of booster sessions has been proposed in various intervention contexts, there is currently a lack of empirical evidence specifically regarding their use in bias-awareness interventions in teacher education. This gap is particularly important considering that biases are deeply embedded in our socialization and thus tend to be especially persistent and resistant to change. Future research should explore how the timing, frequency, and content of such sessions might influence the sustainability of awareness and behavioral change. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that a 90-min intervention can initiate such changes and sustain them over the observed period. To this end, it is necessary in future developments of the intervention to introduce booster sessions at the point at which an initial tendency towards a decline in the effect becomes descriptively apparent, in order to recall the content of the intervention and, in particular, the self-awareness units for initiating reflection processes and to ensure the sustainability of the intervention measure. How these booster sessions should be designed in terms of intervention duration and frequency in order to ensure the sustainability of the measures should be the subject of further research.

We explored the question of whether prospective teachers with higher initial bias awareness or with lower initial bias awareness could benefit more from the tested intervention. Individuals with lower initial bias awareness benefit more from the intervention than those with higher initial bias awareness. Individuals with lower bias awareness may have greater room for growth and development. Because they are less aware of their own biases, they may benefit from our intervention by gaining a basic understanding of biases and their impact on their thinking and decisions. Further, individuals with lower bias awareness may be more susceptible to unconscious biases that influence their behavior and decisions without them realizing it. Interventions like the one tested here could help uncover these unconscious biases and teach strategies to recognize and minimize them, potentially leading to concrete improvements in their behavior. While the term “bias” in the three-component model primarily refers to behavioral tendencies, the present study focuses on “bias awareness,” i.e., the individual recognition of one’s own stereotypes and prejudices. This awareness is expected to be a prerequisite for potential changes in behavior, as recognizing one’s biases is a first step toward modifying actions and judgments. Through those targeted interventions, people with lower bias awareness are sensitized to better understand the meaning of prejudice and its impact on their daily lives. They are encouraged to critically question their own thinking and become more aware of their own biases. Individual differences and context-specific factors also may play an important role and should be targeted in future research.

The fact that the intervention is particularly helpful for people with low initial bias awareness shows that it can create the conditions for follow-up interventions that subsequently translate this created awareness into action-guiding thoughts.

5.1 Limitations

The results of our study support the assumption that prospective teachers with lower bias awareness benefit the most from the given intervention. However, it is important to emphasize that the effectiveness of interventions to increase bias awareness depends heavily on the willingness and openness of participants to accept and apply new concepts (Kumar et al., 2022). Individual differences and context-specific factors may play an important role in assessing how effective and sustainable these interventions can be for people with low bias awareness.

The present study lacks a control group and only considers a pre-post comparison, weakening the interpretation of the results (Aggarwal & Ranganathan, 2019) since the cause(s) for the changes could be others than the intervention. However, it seems implausible that all (or at least most) participants were exposed to the same (similar) “events,” reducing bias by chance during the study. Furthermore, the intervention targets well-documented theoretical constructs (Monteith et al., 2010a; Perry et al., 2015), and the outcomes align with existing literature, reinforcing the plausibility of the findings.

A selective group of people could also have taken part in the intervention, which would limit the generalizability of the results (Cook et al., 2002; Heckman, 1979). However, it should be noted that the study was announced very openly, and the participants were therefore not aware of the topic in advance. They were only informed that they would be taking part in a three-part study with an input session on a topic relevant to prospective teachers. The fact that the student teachers have additional incentives to participate regardless of the content due to the allocation of test subject hours, which all prospective teachers have to complete as part of their studies, also limits the problem that only very motivated, committed students may have taken part.

The sample size shrank from t2 to t3. This drop-out could be problematic if the drop-out is selective (Stellato et al., 2025) and, for example, all motivated or possibly already sensitized participants continue to participate, while other people drop out. A different performance of the groups in the post-measurement could then be partly due to the higher motivation or sensitization. The motivation of the participants was not recorded in this study. However, age and different bias awarenesses (separate for each group) at the three measurements as a selection factor could be ruled out. These results suggest that the dropout rate is completely at random, which would not affect the performed analyses (Stellato et al., 2025).

While our study assessed bias awareness toward migration background in a general manner, future research should consider the heterogeneity within migrant groups, as attitudes and biases may differ significantly depending on specific cultural or ethnic backgrounds.

6 Conclusion

This study provides an initial approach to increasing bias awareness among prospective teachers, which represents a starting point for follow-up studies and further development.

This brief intervention and the associated goal of increasing the bias awareness of prospective teachers were based on the assumption that people are only receptive to targeted programs to reduce stereotypes and prejudices when they recognize their personal relevance. Thus, in addition to its sole effectiveness, this brief intervention also represents an additive component to other programs aimed at reducing stereotypes and prejudices (Lai et al., 2016). Our approach addresses the gaps by embedding bias awareness in a theoretically grounded reflection process, thereby contributing a complementary and theoretically informed perspective to the current landscape of bias reduction strategies. In order to assess its effectiveness in relation to supporting and supplementing programs to reduce stereotypes and prejudices, which impart knowledge about these phenomena but do not trigger personal relevance, it is necessary to test the bias awareness intervention tested here, together with programs to reduce stereotypes and prejudices. Furthermore, the extent to which such an upstream AHA intervention to increase bias awareness can support other programs in their long-term effectiveness must be examined.

This research highlights the significance of bias awareness, emphasizing its pervasive impact on individuals. By recognizing biases and implementing effective interventions, it becomes possible to mitigate their adverse effects and foster a more inclusive and equitable environment.

The AHA intervention used here is an important starting point for creating awareness of one’s own biases. This intervention strategy is promising and can potentially be integrated into the everyday lives of teachers in a short space of time. Further research should examine how an optimal framework for the brief intervention and follow-up lessons can be designed, particularly in terms of the frequency and intensity of subsequent opportunities for reflection. In terms of content, it is relevant to further develop the intervention and, if necessary, make it even more relevant for experienced teachers (e.g., incorporate further practical exercises with a school reference for self-awareness). In the next step, it is important to link this short bias awareness intervention with other intervention approaches and to test whether the previously suggested bias awareness can actually increase their sustainability. In addition, further research is needed regarding the frequency with which bias awareness needs to be stimulated in order to achieve long-term sustainable effects and whether smaller refreshing or booster units can be sufficient for this. Overall, an intervention to increase bias awareness is crucial to combat prejudice and discrimination, promote fairer decision-making processes, strengthen empathy and collaboration, and create a fairer and more inclusive society.

-

Funding information: We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

-

Author contributions: MB conceptualized the study, designed the research, collected the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MB and BF analyzed and interpreted the data. BF contributed to writing the manuscript and provided critical feedback.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MB, upon reasonable request.

References

Aggarwal, R., & Ranganathan, P. (2019). Study designs: Part 4 – Interventional studies. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 10(3), 139. doi: 10.4103/PICR.PICR_91_19.Suche in Google Scholar

Allport, G., Clark, K., & Pettigrew, T. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonefeld, M., & Dickhäuser, O. (2018). (Biased) Grading of students’ performance: Students’ names, performance level, and implicit attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00481.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonefeld, M., Dickhäuser, O., Janke, S., Praetorius, A. K., & Dresel, M. (2017). Migrationsbedingte Disparitäten in der Notenvergabe nach dem Übergang auf das Gymnasium [Migration-related disparities in grade assignment after the transition to high school]. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 49(1), 11–23. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637/a000163.Suche in Google Scholar

Boud, D., & Walker, D. (1998). Promoting reflection in professional courses: The challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 191–206. doi: 10.1080/03075079812331380384.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourne, L. E., & Ekstrand, B. R. (1992). Einführung in die Psychologie [Introduction to Psychology] (3rd ed). Klotz.Suche in Google Scholar

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

Burns, M. D., Monteith, M. J., & Parker, L. R. (2017). Training away bias: The differential effects of counterstereotype training and self-regulation on stereotype activation and application. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73, 97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Canty, A., Ripley, B., & Brazzale, A. R. (2021). boot: Bootstrap Functions (Originally by Angelo Canty for S) (1.3-28). https://cran.r-project.org/package=boot.Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, E. H., Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D. M., Rebele, R. W., Massey, C., Duckworth, A. L., & Grant, A. M. (2019). The mixed effects of online diversity training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(16), 7778–7783.10.1073/pnas.1816076116Suche in Google Scholar

Charlesworth, T. E. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2022). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: IV. Change and stability from 2007 to 2020. Psychological Science, 33(9), 1347–1371. doi: 10.1177/09567976221084257.Suche in Google Scholar

Charlesworth, T. E. S., Navon, M., Rabinovich, Y., Lofaro, N., & Kurdi, B. (2023). The project implicit international dataset: Measuring implicit and explicit social group attitudes and stereotypes across 34 countries (2009–2019). Behavior Research Methods, 55(3), 1413–1440. doi: 10.3758/S13428-022-01851-2/FIGURES/5.Suche in Google Scholar

Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T., & Shadish, W. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference (Vol. 1195). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.Suche in Google Scholar

De Houwer, J. (2019). Implicit bias is behavior: A functional-cognitive perspective on implicit bias. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(5), 835–840. doi: 10.1177/1745691619855638.Suche in Google Scholar

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/J.JESP.2012.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Devine, P. G., Plant, E. A., Amodio, D. M., Harmon-Jones, E., & Vance, S. L. (2002). The regulation of explicit and implicit race bias: The role of motivations to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 835–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.835.Suche in Google Scholar

Fehringer, B. C. O. F., Bonefeld, M., & Schunk, F. (2025). Bias awareness in teachers: A German adaptation of the bias awareness scale for teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/S11218-025-10016-W.Suche in Google Scholar

Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 1–74). Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Fiske, S. T., & Tablante, C. B. (2015). Stereotyping: Processes and content. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, E. Borgida, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 1: Attitudes and social cognition. (pp. 457–507). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14341-015.Suche in Google Scholar

Gawronski, B., Ledgerwood, A., & Eastwick, P. W. (2022). Implicit bias ≠ bias on implicit measures. Psychological Inquiry, 33(3), 139–155. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2022.2106750.Suche in Google Scholar

Glock, S., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers’ judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(1), 111–127. doi: 10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Klapproth, F., & Böhmer, M. (2013). Beyond judgment bias: How students’ ethnicity and academic profile consistency influence teachers’ tracking judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(4), 555–573. doi: 10.1007/s11218-013-9227-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Glock, S. (2016). Does ethnicity matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on in-service teachers’ judgments of students. Social Psychology of Education, 19(3), 493–509. doi: 10.1007/s11218-016-9349-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Grube, J. W., Mayton, D. M., & Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (1994). Inducing change in values, attitudes, and behaviors: Belief system theory and the method of value self-confrontation. Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 153–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01202.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161. doi: 10.2307/1912352.Suche in Google Scholar

Hill, M. E., & Augoustinos, M. (2001). Stereotype change and prejudice reduction: short- and long-term evaluation of a cross–cultural awareness programme. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11(4), 243–262. doi: 10.1002/CASP.629.Suche in Google Scholar

Hofer, M., & Waag, A. (2020). Reflexion als zentrales Element von Service Learning. Eine theoretische Bestimmung [Reflection as a central element of service learning. A theoretical definition]. In M. Hofer & J. Derkau (Eds.), Campus und Gesellschaft: Service Learning an deutschen Hochschulen: Positionen und Perspektiven (pp. 103–120). Beltz.Suche in Google Scholar

Holder, K., & Kessels, U. (2017). Gender and ethnic stereotypes in student teachers’ judgments: A new look from a shifting standards perspective. Social Psychology of Education, 20(3), 471–490. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9384-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Jussim, L., & Harber, K. D. (2005). Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(2), 131–155. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3.Suche in Google Scholar

Kleen, H., & Glock, S. (2018). A further look into ethnicity: The impact of stereotypical expectations on teachers’ judgments of female ethnic minority students. Social Psychology of Education, 21(4), 759–773. doi: 10.1007/s11218-018-9451-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, R., Gray, D. L. L., & Kaplan Toren, N. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ desire to control bias: Implications for the endorsement of culturally affirming classroom practices. Learning and Instruction, 78, 101512. doi: 10.1016/J.LEARNINSTRUC.2021.101512.Suche in Google Scholar

Lai, C. K., Skinner, A. L., Cooley, E., Murrar, S., Brauer, M., Devos, T., Calanchini, J., Xiao, Y. J., Pedram, C., Marshburn, C. K., Simon, S., Blanchar, J. C., Joy-Gaba, J. A., Conway, J., Redford, L., Klein, R. A., Roussos, G., Schellhaas, F. M. H., Burns, M., … Nosek, B. A. (2016). Reducing implicit racial preferences: II. Intervention effectiveness across time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(8), 1001–1016. doi: 10.1037/xge0000179.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenth, R. V., Bolker, B., Buerkner, P., Giné-Vázquez, I., Herve, M., Jung, M., Love, J., Miguez, F., Riebl, H., & Singmann, H. (2023). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (1.8.7). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.Suche in Google Scholar

Lippmann, W. (1922). The world outside and the pictures in our heads. In Public opinion. (pp. 3–32). MacMillan Co. doi: 10.1037/14847-001.Suche in Google Scholar

McKown, C., & Weinstein, R. S. (2008). Teacher expectations, classroom context, and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology, 46(3), 235–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Monteith, M. J. (1993). Self-regulation of prejudiced responses: Implications for progress in prejudice-reduction efforts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(3), 469–485. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.469.Suche in Google Scholar

Monteith, M. J., Arthur, S. A., & McQueary Flynn, S. (2010a). Self-regulation and bias. In The SAGE Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination (pp. 493–507). SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781446200919.n30.Suche in Google Scholar

Monteith, M. J., Mark, A. Y., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2010b). The self-regulation of prejudice: Toward understanding its lived character. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13(2), 183–200. doi: 10.1177/1368430209353633.Suche in Google Scholar

Monteith, M. J., & Voils, C. I. (1998). Proneness to prejudiced responses: toward understanding the authenticity of self-reported discrepancies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 901–916. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.901.Suche in Google Scholar

Morewedge, C. K., Yoon, H., Scopelliti, I., Symborski, C. W., Korris, J. H., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Debiasing decisions. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(1), 129–140. doi: 10.1177/2372732215600886.Suche in Google Scholar

Moskowitz, G. B., & Ignarri, C. (2009). Implicit volition and stereotype control. European Review of Social Psychology, 20(1), 97–145. doi: 10.1080/10463280902761896.Suche in Google Scholar

Moskowitz, G. B., & Li, P. (2011). Egalitarian goals trigger stereotype inhibition: A proactive form of stereotype control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(1), 103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.08.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Moskowitz, G. B., Li, P., Ignarri, C., & Stone, J. (2011). Compensatory cognition associated with egalitarian goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(2), 365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.08.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Nelson, J. C., Adams, G., & Salter, P. S. (2012). The Marley hypothesis. Psychological Science, 24(2), 213–218. doi: 10.1177/0956797612451466.Suche in Google Scholar

Ozier, E. M., Taylor, V. J., & Murphy, M. C. (2019). The cognitive effects of experiencing and observing subtle racial discrimination. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1087–1115. doi: 10.1111/JOSI.12349.Suche in Google Scholar

Penner, L. A. (1971). Interpersonal attraction toward a black person as a function of value importance. Personality: An International Journal, 2(2), 175–187.Suche in Google Scholar

Pereira, C., Taylor, J., & Jones, M. (2009). Less learning, more often: The impact of spacing effect in an adult e-learning environment. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 15(1), 17–28. doi: 10.1177/147797140901500103.Suche in Google Scholar

Perry, S. P., Dovidio, J. F., Murphy, M. C., & Van Ryn, M. (2015). The joint effect of bias awareness and self-reported prejudice on intergroup anxiety and intentions for intergroup contact. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 89–96. doi: 10.1037/A0037147.Suche in Google Scholar

Perry, S. P., Murphy, M. C., & Dovidio, J. F. (2015). Modern prejudice: Subtle, but unconscious? The role of Bias Awareness in Whites’ perceptions of personal and others’ biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.06.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Perry, S. P., Skinner, A. L., & Abaied, J. L. (2019). Bias awareness predicts color conscious racial socialization methods among White parents. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1035–1056. doi: 10.1111/josi.12348.Suche in Google Scholar

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion. Central and peripheral routes to attitude change (pp. 1–24). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1_1.Suche in Google Scholar

Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811–832. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1.2). https://www.R-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Revelle, W. (2021). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research (2.1.9). https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych.Suche in Google Scholar

Rokeach, M., & Cochkane, R. (1972). Self-confrontation and confrontation with another as determinants of long-term value change1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2(4), 283–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1972.tb01280.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Rosenberg, M. J. (1960). Cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of attitudes. Attitude organization and change, 1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

Rosenberg, M. J., & Hovland, C. I. (1960). Cognitive, affective and behavioral components of attitudes. In M. J. Rosenberg & C. I. Hovland (Eds.), Attitude organization and change an analysis of consistency among attitude components (pp. 1–14). Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schön, D. (1991). The reflective turn: Case studies in and on educational practice. Teachers College Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schwarz, N. (2015). Metacognition. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, E. Borgida, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 1: Attitudes and social cognition (pp. 203–229). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14341-006.Suche in Google Scholar

Singmann, H., Bolker, B., Westfall, J., Aust, F., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Højsgaard, S., Fox, J., Lawrence, M. A., Mertens, U., Love, J., Lenth, R., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2023). afex: Analysis of factorial experiments (1.3-0). https://cran.r-project.org/package=afex.Suche in Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2001). Improving intergroup relations. Sage.10.4135/9781452229225Suche in Google Scholar

Stellato, R. K., van den Bor, R. M., Schipper, M., Lindeboom, M. Y. A., & Eijkemans, M. J. C. (2025). Cohort data with dropout: A simulation study comparing five longitudinal analysis methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 25(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1186/S12874-025-02506-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Stoeger, H., Ziegler, A., & David, H. (2004). What is a specialist? Effects of the male concept of a successful academic person on performance in a thinking task. Psychology Science, 46(4), 514–530.Suche in Google Scholar

Strasser, J. (2012). Kulturelle Stereotype und ihre Bedeutung für das Verstehen in Schule und Unterricht [Cultural stereotypes and their significance for comprehension in schools and classrooms]. In W. Wiater & D. Manschke (Eds.), Verstehen und Kultur (pp. 191–215). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-94085-4_9.Suche in Google Scholar

Tobisch, A., & Dresel, M. (2017). Negatively or positively biased? Dependencies of teachers’ judgments and expectations based on students’ ethnic and social backgrounds. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 731–752. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9392-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). Evidential impact of base rates. Stanford University.10.21236/ADA099501Suche in Google Scholar

Vuletich, H. A., & Payne, B. K. (2019). Stability and change in implicit bias. Psychological Science, 30(6), 854–862. doi: 10.1177/0956797619844270.Suche in Google Scholar

Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140. doi: 10.1080/17470216008416717.Suche in Google Scholar

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Positive Economic Psychology: Exploring the Intersection between Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology, edited by Rona Hart (University of Sussex, UK) - Part I

- New Frontier: Positive Economic Psychology

- The Role of Gratitude in Financial Stress and Financial Behaviours

- Research Articles

- On Panksepp’s Primary Emotional Systems, Steger’s Meaning in Life and Diener’s Satisfaction with Life: A Study Attempt from India

- Influencing Adolescents’ Gendered Aspirations for Nursing and Surgery

- Failing Despite Knowing. Repeated Decision-Making During Binary Random Sequences with Asymmetric Probabilities

- Replicability of Tightness–Looseness Scale in a Brazilian Sample: Validity and Challenges

- Unveiling Bias: Assessing the Efficacy of an Intervention in Enhancing Bias Awareness of Pre-Service Teachers

- Review Article

- Salutogenic Effects of Greenspace Exposure: An Integrated Biopsychological Perspective on Stress Regulation, Mental and Physical Health in the Urban Population

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Positive Economic Psychology: Exploring the Intersection between Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology, edited by Rona Hart (University of Sussex, UK) - Part I

- New Frontier: Positive Economic Psychology

- The Role of Gratitude in Financial Stress and Financial Behaviours

- Research Articles

- On Panksepp’s Primary Emotional Systems, Steger’s Meaning in Life and Diener’s Satisfaction with Life: A Study Attempt from India

- Influencing Adolescents’ Gendered Aspirations for Nursing and Surgery

- Failing Despite Knowing. Repeated Decision-Making During Binary Random Sequences with Asymmetric Probabilities

- Replicability of Tightness–Looseness Scale in a Brazilian Sample: Validity and Challenges

- Unveiling Bias: Assessing the Efficacy of an Intervention in Enhancing Bias Awareness of Pre-Service Teachers

- Review Article

- Salutogenic Effects of Greenspace Exposure: An Integrated Biopsychological Perspective on Stress Regulation, Mental and Physical Health in the Urban Population