Abstract

This study investigated the influence of gender stereotypes on adolescents’ vocational aspirations and the potential mitigating effects of gender-inclusive linguistic forms. Building on Fox and Barth’s (2017. The effect of occupational gender stereotypes on men’s interest in female-dominated occupations. Sex Roles, 76(7–8), 460–472) findings and literature on gender-fair language, we tested if various presentations of occupation titles within healthcare occupational descriptions could decrease the saliency of gender stereotypes. Two hundred and twenty-two adolescents aged between 12 and 19 were provided with descriptions, in French, of healthcare occupations either without any title, in the Masculine grammatical form (the so-called generic form) or in the Pair Form (gender-fair condition). Adolescents’ interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations were measured. Girls’ and boys’ interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations were in line with gender stereotypes, regardless of how the occupations’ titles were presented. We discuss these findings in relation to potential interventions that may help reduce gendered interests in adolescents and health careers.

1 Introduction

In this article, we present a study on the impact of gender stereotypes on adolescents’ vocational aspirations in the field of health care – a feminine-stereotyped domain (e.g. Nguyen, 2018; Tellhed et al., 2017) – and the potential mitigating effect of different linguistic presentations on gendered aspirations. We are particularly interested in reducing gender segregation.

Occupational gender segregation prevents competent people from accessing certain occupations and contributes to wage inequality (Hegewisch et al., 2010). While a large body of research has investigated the underrepresentation of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), to the best of our knowledge, only a few of them have questioned the lack of men in stereotypically feminine domains such as nursing (e.g. Chaffee et al., 2020; Croft et al., 2015; Fox & Barth, 2017). This may seem rather surprising, as some have argued that encouraging pre-high school students (Cohen et al., 2004; Nevidjon & Erickson, 2001) and men (e.g. Block et al., 2019; Croft et al., 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2010) into healthcare occupations is especially relevant considering the worldwide shortage of healthcare professionals (Addati et al., 2018; Michel & Ecarnot, 2020; Nevidjon & Erickson, 2001). Plus, some argue that increasing gender diversity among surgeons would benefit healthcare (Hemal et al., 2021; Troppmann, 2009). To achieve this, several obstacles need to be surmounted, including the challenge of overcoming gender biases.

Some have argued that different linguistic presentations of role nouns could influence some gender biases, such as gender stereotypes, as well as those inherent to the grammatical structure of certain languages. At the heart of the influence of grammatical gender is the semantic ambiguity associated with the masculine form. Whereas English does not grammatically mark gender on most occupation titles (i.e., “nurse” does not denote the gender of the person), occupation titles in French can differ, in that they can be presented in the feminine (e.g. une infirmière [FEM] [woman nurse]) or the masculine form (e.g. un infirmier [MASC] [man nurse]). Importantly, in many grammatical gender languages, the masculine form can theoretically be considered as the unmarked, or neutral form, potentially also referring to a woman, or to a group of women and men, or to people for whom gender is irrelevant (Gygax et al., 2019a). Although allegedly generically understandable, the masculine form has been shown to generate a masculine bias (e.g. Braun et al., 2005; Gygax & Gabriel, 2008; Gygax et al., 2008, 2009, 2012; Horvath & Sczesny, 2016; Kim et al., 2023; Kollmayer et al., 2018; Sato et al., 2013; Stahlberg et al., 2001; Tibblin et al., 2023; Xiao et al., 2023). To counter this masculine bias, the pair form – a form where both women and men are made explicit – can be used and has been shown to alleviate the effects of both masculine bias and occupational gender stereotypes (e.g. Vervecken et al., 2013).

In the present study, we compared the use of the masculine form alone (e.g. les infirmiers [MASC] [men nurses]), to both the pair form (e.g. Infirmières [FEM] et infirmiers [MASC] [women and men nurses]) and an unspecified gender form (i.e., a no title condition). The latter condition was inspired by Fox and Barth’s (2017) seminal study, in which removing the title of an occupation in its description (e.g. using “People who do this job use […]” instead of “Nurses use […]”) was shown to increase men’s interest in stereotypically feminine occupations. As Fox and Barth’s (2017) results seemed to attenuate the influence of gender stereotypes on adults, we decided to further explore this approach by conducting a study on adolescents’ vocational aspirations.

To investigate gender-stereotyped vocational aspirations and the potential effect of various linguistic presentations, we measured two constructs – interest and anticipated sense of belonging – which are both important for the elaboration of vocational aspirations during adolescence (e.g. Tellhed et al., 2017; Volodina & Nagy, 2016), a crucial stage in the development of career aspirations (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997; Gottfredson, 1981; Porfeli & Lee, 2012; Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013; Volodina & Nagy, 2016). We concentrated on three healthcare occupations bearing different gender stereotypicality: nurse as the stereotypically feminine one, surgeon as the stereotypically masculine one, and clinical psychologist as neither stereotypically feminine nor masculine (which will be referred to as “neutral” throughout this article) (Misersky et al., 2014). Note that the terms “women/girl” and “men/boy” are used throughout, to avoid “female” and “male,” most commonly associated with “biological sex” rather than gender identity (Ansara & Hegarty, 2014). Additionally, studies presented in this article have used different names to refer to occupations/professions/activities, such as “role nouns,” “role names,” or “profession titles.” In the present article, as we are only concerned with healthcare occupations, and for coherence purposes, we use the term “occupation title” throughout.

1.1 The Concepts of Gender and Gender Stereotypes and Their Influence on Vocational Aspirations Towards Healthcare Occupations

1.1.1 Gender as a System

In most studies that we present in the next sections, both gender stereotypes and grammatical gender were manipulated, making the notion of gender the cornerstone of this type of research. Although we do not directly address the construct of gender in the present article, it is important to specify how we conceptualise the notion of gender. According to Bereni et al. (2012), gender can be, and has often been defined as a “hierarchical bicategorisation system,” containing two sexes – women and men – and representations associated with each – feminine and masculine. This definition mainly suggests that gender is more than just an individual identity but rather a “relational process” (Bereni et al., 2012, p. 7), meaning that stereotypically feminine characteristics are constructed in opposition to stereotypically masculine ones and vice versa (Bereni et al., 2012). Not only are those characteristics built in opposition, but they are embedded in a power relationship in that masculine representations and men (in opposition to feminine representations and women) are given a higher value. Plus, almost every society tends to allocate economic and political resources unequally (e.g. feminine attributes are systematically disvalued compared to masculine ones) (Bereni et al., 2012). This unequal repartition of resources leads to global inequalities towards women in different domains, such as those we are interested in (Saguy et al., 2021). In our research, though, we are particularly interested in two gender dimensions: gender of the participant and gender stereotypes, and their influence on adolescents’ vocational aspirations for occupations (i.e., nurse, surgeon) that carry stereotypical (and hierarchical) gender representations.

1.1.2 Gender Stereotypes and Vocational Aspirations

A stereotype has been defined as a belief about a group’s attributes and characteristics (e.g. the belief that women are more caring) (Eagly & Wood, 2012), which often leads to prejudice and discrimination (Dayer, 2017). According to the Social Role Theory, stereotypes are ascribed to one specific gender depending on one’s frequent observations of women and men in social roles that require certain qualities. These stereotypes stem from gender roles (Eagly & Wood, 2012), which often give the essentialist impression that they are constructed through “natural” aspects of gender (e.g. Dayer, 2017; Saguy et al., 2021). As women are more likely than men to be in care roles and men are more likely than women to be in leading positions, people infer that women have communal and men have agentic traits (Eagly & Wood, 2012; Koenig & Eagly, 2014). Communion and agency represent key characteristics of femininity and masculinity (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007), with communion referring to caring about people and social relationships, whereas agency is associated with personal goals (Abele et al., 2008; Eagly & Wood, 2012; Gustafsson Sendén et al., 2020; Koenig & Eagly, 2014). These characteristics are internalised during childhood (Olsen et al., 2022) and are at the heart of beliefs associated with healthcare occupations, on which we focus in the present article. Concurrent to Social Role Theory is the System Justification Theory which posits that individuals are driven by the motive to justify the existing social system. This implicit and unconscious motive is found amongst dominating and subordinated social groups, and is one of the causes of outgroup favouritism and internalisation of inferiority among subordinated group members (Jost et al., 2004). On this view, gender stereotypes play a key role in system justification by providing a rationale for gender segregation (Jost & Banaji, 1994). More specifically, the belief of complementarity between gender stereotypes (i.e., between communal vs agentic traits) reinforces women’s tendency to justify the status quo (Jost et al., 2004). Note that gender stereotypes are not always positive for the dominating group and negative for the dominated one, which means that positive traits can also contribute to the justification of the status quo (Jost & Banaji, 1994).

In our article, we manipulated stereotypicality in the occupation title (i.e., nurse vs surgeon vs clinical psychologist), yet keeping communion and agency balanced across the descriptions. This balance was intended to ensure that our title conditions (i.e., No Title vs Masculine form vs Pair Form) were at the centre of our attention and interest. As will be discussed in the section on Fox and Barth’s ( 2017 ) study, we therefore decided to deviate from Fox and Barth’s (2017) original study.

Gender stereotypes have been shown to influence occupational representations and career interests (e.g. Barth & Masters, 2024; Hoff et al., 2018; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013; Wilbourn & Kee, 2010). According to the Theory of Circumscription and Compromise (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997; Gottfredson, 1981), gender stereotypes associated with occupations are the first criterion used by children to rule out occupational possibilities, followed by prestige, as defined by social class (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997; Gottfredson, 1981). Since gender is a core component of self-concept and cannot be ignored, it plays a significant role in our identity in society (Gottfredson, 1981), especially for adolescents who are reluctant to compromise it (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997). Ironically, adolescence is a crucial period of life in vocational development (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997; Gottfredson, 1981; Porfeli & Lee, 2012; Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013) since teenagers are expected to make concrete decisions to pursue their aspirations (Porfeli & Lee, 2012).

1.1.3 Gender Stereotypes and Healthcare Occupations

While many studies have explored strategies to increase girls’ interest in occupations where men are the majority (STEM) (e.g. Tellhed et al., 2017), to the best of our knowledge and as raised by some (e.g. Croft et al., 2015; Fox & Barth, 2017; Olsen et al., 2022; Tellhed et al., 2017), little has been done to interest boys in occupations predominantly held by women (HEED – Healthcare, Early Education and Domestic Roles). This asymmetry is at least partly explained by the lower status of communal occupations (Croft et al., 2015), which often leads to less support for social actions that support gender balance in these occupations (Block et al., 2019). Moreover, efforts aimed at increasing women’s participation in STEM occupations have resulted in more intervention and research funding (Croft et al., 2015). These funding asymmetries also led to social psychology research focusing more on this topic, often at the expense of issues related to men in communal roles (Croft et al., 2015).

Yet, the healthcare domain remains gender segregated both between and within occupations (e.g. Hay et al., 2019; Porter, 1992; Williams, 1992) as shown by horizontal segregation – men dominating higher-paid occupations and women being the majority in lower-paid ones (Addati et al., 2018; Battagliola, 2001; Gianettoni et al., 2015; Murphy & Oesch, 2016) – as well as vertical segregation – men being more prone to get promoted to leading positions while women remain in subordinated positions (Gianettoni et al., 2015). Importantly, healthcare occupations are heterogeneous, with significant differences in income, status, and working conditions. Within healthcare occupations, nursing represents the biggest group, and with higher rates of women (Addati et al., 2018). Some have argued that women are the majority in nursing as it is often thought of as being an extension of domestic work, which would “naturally” come to women (Abbott & Meerabeau, 1998; Addati et al., 2018; Benelli & Modak, 2010; Teresa-Morales et al., 2022). However, a few leading positions in the health sector are occupied by women (WHO, 2020). This is most likely due to stereotypes associated with some healthcare occupations, as requiring more communal (i.e., feminine-associated) traits and some as more agentic ones (i.e., masculine-associated). For example, Gustafsson Sendén et al. (2020) showed that participants associated nursing with communal traits (e.g. “caring,” “understanding,” “sensitive,” […]), irrelevant of the pronoun used (she vs he) to refer to the person in the occupation, demonstrating the strength of the association between nursing and communion (Gustafsson Sendén et al., 2020). Others have even shown that medical and nursing students both believed that physicians were more competent and agentic than nurses (Sollami et al., 2015), which shows the associations of those occupations with communion (for nurses) and agency (for surgeons). In line with this assumption is the well-known riddle, first introduced by Sanford (1985), and further tested by Reynolds et al. (2006), about a surgeon who cannot operate on a child whose father has just died because the surgeon claims to be the child’s parent. Most people have trouble resolving this riddle (i.e., the surgeon is the mother of the child) as the occupation title surgeon automatically activates the representation of a man (Reynolds et al., 2006). This stereotypically masculine occupation (e.g. Carreiras et al., 1996; Chatard et al., 2005; Couch & Sigler, 2001; Misersky et al., 2014; Reynolds et al., 2006) is also characterised by a prestigious status (Hoffmann et al., 2014; Zelek & Phillips, 2003). Although some have argued that increasing the number of women surgeons would benefit the quality of care (Hemal et al., 2021), women still perceive themselves as not fitting the surgeon prototype (e.g. Peters et al., 2012), and negative stereotypes remain about women surgeons’ performance and ability (e.g. Salles et al., 2016). Some studies even suggest that women in surgical practice are rated as higher on warmth (a stereotypical trait associated with communion) than men (Ashton-James et al., 2019).

Therefore, investigating ways to influence adolescents’ preferences for either nursing or surgical practice could help improve the current shortage in some healthcare occupations (Cohen et al., 2004), in parallel to globally improving the working conditions of healthcare professionals (Dante et al., 2014; Michel & Ecarnot, 2020). To address this issue, we investigated the influence of gender stereotypes and linguistic formulations of occupation titles on vocational aspirations regarding healthcare occupations. As vocational aspiration is a rather broad concept, we explain its theoretical foundation and operationalisation next.

1.1.4 Vocational Aspirations: An Operationalisation Through Interest and Anticipated Sense of Belonging

Vocational interests during adolescence are the most important predictors of occupational choices (Volodina & Nagy, 2016) and career expectations (Paa & McWhirter, 2000), yet they are often conditioned by gender stereotypes (Gianettoni et al., 2015). Consequently, and in line with Fox and Barth (2017), we used interest as our dependent variable to operationalise vocational aspirations. We complemented it with a measure of anticipated sense of belonging, as Good et al. (2012) argued that a sense of belonging was an important component of vocational aspirations and may be considered a factor in gender gaps in some occupations. In fact, some studies have shown that sense of belonging could fluctuate as a function of gender cues (Hentschel et al., 2021; Stout & Dasgupta, 2011; Tellhed et al., 2017). For example, Tellhed et al. (2017) showed that Swedish high school students’ anticipated sense of belonging partially mediated gender differences in interest in HEED and STEM for both genders. In Hentschel et al.’s (2021) study, participants saw a picture of a woman or a man recruiter with a speech bubble describing a career programme either using feminine- (people-oriented, supportive, cooperative, …) or masculine-stereotyped (e.g. determined, outstanding, leadership, …) words. Results showed that when women were presented with advertisements for career programmes worded with masculine-stereotyped adjectives, they anticipated lower levels of belonging if the recruiter was a man. Similarly, Stout and Dasgupta (2011) – whose study will be detailed in the next section – showed that linguistic gender cues also impacted participants’ anticipated sense of belonging.

From an applied perspective, we reason that considering the impact of gender stereotypes on vocational aspirations is critical when considering gender work inequalities. Since research has shown that gender information can be modulated using distinct linguistic forms (detailed in the next section), this study explores the impact of gender stereotypes and different linguistic forms in the titles of occupations on vocational aspirations.

1.2 Grammatical Gender, Mental Representations, and Their Impact on Adolescents’ Vocational Aspirations

In French, as in many grammatical gender languages, the masculine form, although used to refer exclusively to a man or a group of men (i.e., the specific use of the masculine form), can also be used to refer to a group of people constituted of both women and men, even if women are the numerical majority. This is called the generic use, or generic interpretation of the masculine form. For example, it is grammatically correct to use “les infirmiers[MASC]” to refer to a group of women and men nurses. However, a large body of evidence has shown that the masculine form tends not to be spontaneously interpreted as generic, but as specific, leading to heightened mental representations of men (e.g. Brauer, 2008; Braun et al., 2005; Gygax & Gabriel, 2008; Gygax et al., 2008, 2012, 2021; Kim et al., 2023; Kollmayer et al., 2018; Richy & Burnett, 2021; Sato et al., 2013; Stahlberg et al., 2001; Tibblin et al., 2023; Xiao et al., 2023), even among a younger cohort (e.g. Gygax et al., 2019b). Although there are other options to avoid the use of the masculine form as generic, this form is still commonly used in French, arguably enforcing a societal androcentric perspective (Gygax et al., 2021).

One solution that has been suggested to avoid the use of a masculine form to refer to a group of women and men is to use the pair form, a grammatically correct form that highlights the presence of women in a group by explicitly referencing them using the grammatical feminine form such as in the expression “les infirmières[FEM] et infirmiers[MASC]” [the women and men nurses]. This form has received extensive attention in the literature and has been shown to increase the visibility of women (i.e., increase the presence of women in readers’ mental representations) (Chatard et al., 2005; Horvath & Sczesny, 2016; Horvath et al., 2016; Tibblin et al., 2023; Vervecken & Hannover, 2015; Vervecken et al., 2015).

Most importantly for this study, besides decreasing the masculine bias, the pair form has also been shown to decrease adolescents’ gender-stereotyped perceptions and interest regarding occupations. In their study, Vervecken et al. (2015) presented French-speaking adolescents aged 12–17 with 15 occupations (stereotypically feminine, stereotypically masculine, and stereotypically neutral) either in the masculine form or in the pair form, accompanied by a short description of the activities of each occupation. They showed that the pair form activated more gender-balanced representations of occupational success than the masculine form, in stereotypically masculine, stereotypically feminine, and neutral occupations. Similarly, Vervecken and Hannover (2015) presented gender-stereotypical occupations and short descriptions in the masculine form or the pair form to Dutch- and German-speaking children aged between 7 and 13 years old. They mainly showed an increase in both girls’ and boys’ self-efficacy regarding stereotypical masculine occupations when the pair form were used. These results echo those of Chatard et al. (2005), who showed that French-speaking girls’ and boys’ (aged 13–14 years) self-efficacy increased when they were presented with the pair form (e.g. with the structure [masculine form]/[feminine form]) compared to a masculine form. Interestingly, this effect was especially important for high-prestige occupations, such as surgeon (Chatard et al., 2005). Vervecken et al. (2013) also showed that – among other results – girls aged between 6 and 13 years expressed more interest in stereotypically masculine occupations (i.e., higher prestige occupations) when these were shown in the pair form.

Some have also demonstrated that the use of gender-fair language (i.e., the use of forms that do not refer exclusively to men) in English (i.e., he or she) can impact the feeling of belonging among undervalued groups (Stout & Dasgupta, 2011), with the feeling of belonging defined as a feeling of fitting in or being a member of a group (Good et al., 2012). As previously detailed, this feeling is crucial in the elaboration of vocational aspirations and is prone to the influence of gender stereotypes (e.g. Good et al., 2012; Hentschel et al., 2021; Tellhed et al., 2017). In Stout and Dasgupta (2011), undergraduate women and men were tasked with passing a mock interview with a man recruiter using either gender-exclusive language (e.g. using masculine forms such as “his,” and “guys”) or gender-fair language (e.g. using gender-fair forms such as “his or hers”, and “employees”). In the first part of the interview, the recruiter would present general information about the occupation, and in the second part, participants would fill out some questionnaires. They showed that women anticipated lower levels of belonging, showed less motivation, and felt lower levels of identification with the occupation when the recruiter used gender-exclusive language compared to gender-fair language. Based on those results, we included two scales of anticipated sense of belonging, which will be detailed in the method section.

1.2.1 Fox and Barth’s (2017) Study

A great deal of research has demonstrated that occupation titles are strongly associated with gender stereotypes (e.g. Blakemore, 2003; Wilbourn & Kee, 2010), and that targeting these titles may attenuate gender stereotypes (e.g. Fox & Barth, 2017). For example, Fox and Barth (2017, p. 465) attenuated gender stereotypes by using a more generic title expression (“People in this job”), as opposed to explicitly using occupation titles. To the best of our knowledge, this manipulation has not been replicated or further tested.

In Fox and Barth’s (2017) study, STEM students (a domain in which men are the majority) from the U.S. were presented with 20 descriptions, 16 of which were stereotypically feminine occupations (some of which were healthcare occupations). For each feminine occupation, four versions of the descriptions (two sentences in length) were prepared; half of the descriptions started with the occupation title (e.g. “Nurses”) while the other half started with “People who do this job […].” Then, half of the title descriptions encompassed feminine characteristics (e.g. “intuitive”) and the other half masculine ones (e.g. “analytical”). Thus, participants were presented with stereotypically feminine occupations in four conditions: feminine description with the title, feminine description without the title, masculine description with the title, and masculine description without the title. The descriptions of four stereotypically masculine occupations were added as a comparison point and were always presented with titles and descriptions containing masculine-stereotyped characteristics. Participants rated their level of interest in the presented occupation on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all interested to 5 = Very interested). Results indicated that men showed lower levels of interest in stereotypically feminine occupations when the titles were presented. Women had higher levels of interest in the stereotypically feminine occupations presented with titles and encompassing feminine characteristics than men. However, it is worth noting that both genders showed less interest in stereotypically feminine occupations presented with the title (although the effect was smaller for women) than in the ones without the title.

In sum, Fox and Barth’s (2017) study provided valuable insight into possible linguistic interventions to alleviate stereotypical effects when describing certain occupations. Consequently, in addition to contrasting the masculine form and the pair form, we included a condition in which the title was removed (No Title) (and replaced by “People who do this job…”). We also made important modifications to the Fox and Barth’s (2017) study. First, to the best of our knowledge, Fox and Barth (2017) did not conduct any pretest to ensure internal validity, namely to ensure that the descriptions from which the title was removed would still be associated with the relevant occupation. So, for example, a description of nurse may have been mistaken for another medical/healthcare occupation when its title was removed, making the interpretation of the results rather speculative. To overcome this limitation, we conducted a pretest to ensure that the descriptions without the title were still understood as describing the intended occupations. Second, unlike Fox and Barth (2017) who used rather short descriptions of occupations (two sentences in length) and had a sample consisting of undergraduate students, we explored younger adolescents’ vocational aspirations for healthcare occupations using longer and more natural texts. We thus created longer texts (around 185 words), to provide appropriate depth of the descriptions of occupations for adolescents who might not have advanced knowledge of certain occupations. Third and finally, within each text and to ensure that the focus was on occupation titles, we balanced feminine and masculine characteristics. Conversely, Fox and Barth (2017) presented participants with separate feminine and masculine descriptions.

To sum up, unlike in English, occupation titles in French have a grammatical gender marking (i.e., les infirmières[FEM] et les infirmiers[MASC]). As detailed in the previous section, the masculine form can be used as an unmarked form and hence could theoretically refer to a group of women and men, yet it has been shown to create a masculine bias. This masculine bias has been shown to be alleviated by the pair form, activating more gender-balanced representations. To examine the impact of such gender-fair forms on adolescents’ interest and anticipated sense of belonging, we added a third condition to Fox and Barth’s (2017) study, resulting in description without the title, description with the title in the masculine form, and description with the title in the Pair Form. Based on Fox and Barth’s (2017) results, we expect the No Title condition to prevent the automatic activation of gender stereotypes (Fox & Barth, 2017; Oakhill et al., 2005) and to allow participants to engage in an unbiased exploration of their aspirations for the presented occupations (Fox & Barth, 2017). The other conditions, including the title, however, might trigger occupational gender stereotypes (i.e., Masculine and the Pair Form). Nonetheless, we expect this effect to be attenuated in the Pair Form, as previous research has also shown this particular form to elicit more gender-balanced representations. Finally, we also expect the Masculine Form condition to generate an overall masculine bias.

1.3 The Present Study

In this study, we investigated gender-stereotyped vocational aspirations in three occupations: a stereotypically feminine (nurse), a stereotypically masculine (surgeon), and a gender-neutral occupation (clinical psychologist). Additionally, linguistic presentations were manipulated as follows: a condition in which the title was removed, inspired by Fox and Barth (2017), a condition where the title is in the Masculine Form, and one in the Pair Form. We therefore investigated three independent variables expected to influence adolescents’ interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to different occupations: (1) the gender stereotypes associated with the occupation (Stereotype: Masculine, Feminine, Neutral), (2) the condition in which the name of the occupation is presented (Title: No Title, Masculine title, Pair Form title), and (3) Participant’s Gender (Gender: Girl, Boy). The dependent variables were (1) levels of interest in the presented occupations and (2) levels of anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations.

1.3.1 Hypotheses for Girls and Boys (Lower Secondary Level)

We expected several effects. First, inspired by Fox and Barth’s (2017) title vs No Title effect (i.e., more interest in the No Title condition), we expect a main effect of Title, whereby the absence of a title should result in the highest interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations. Then, in line with previous research on gender-fair language, the Pair Form should lead to higher interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations than the Masculine Form (both expectations merged as Hypothesis 1). Based on Vervecken and Hannover (2015) and Chatard et al. (2005), we expected this main effect to be qualified by a Title by Gender interaction effect, whereby participants should show higher interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations in the No Title condition than in the Pair Form (i.e., the form including the feminine form), followed by the Masculine Form condition, but we expected this effect to be stronger for girls (Hypothesis 2). We also expected a Gender by Stereotype interaction for interest and anticipated sense of belonging (Barth & Masters, 2024; Fox & Barth, 2017; Tellhed et al., 2017). Specifically, we expected girls and boys to show higher levels of interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to occupations congruent with the stereotype associated with their gender (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we expected a three-way Title by Gender by Stereotype interaction effect. Namely, participants – both girls and boys – should show higher levels of interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the counter-stereotypical occupation when it is presented in the No Title condition (Fox & Barth, 2017) than in the Pair Form followed by the Masculine Form. In other words, girls should show higher levels of interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the stereotypically masculine occupation (surgeon) whereas boys should show this for the stereotypically feminine occupation (nurse), and this should mainly occur in the No Title condition (Hypothesis 4).

1.3.2 Hypotheses Specific for Girls (Lower and Upper Secondary Levels)

As detailed below, we had access to an additional cohort of older girls, resulting in a rather unbalanced gender sample. We therefore additionally analysed the entire sample of girls (lower and upper secondary levels combined), without boys. For this sample, we expected a Title effect, a Stereotype effect, and a Title by Stereotype effect for this sample. First, the absence of a title should result in the highest interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations. Then, according to past research on gender-fair language, the Pair Form should lead to higher interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations than the Masculine Form (Hypothesis 5). Second, we expected girls to show higher levels of interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to the stereotypically feminine occupation than to the neutral, followed by the stereotypically masculine occupation (Hypothesis 6). Third and finally, we expected a two-way interaction Title by Stereotype. Namely, girls should show higher levels of interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to occupations when presented in the No Title condition than in the Pair Form, followed by the Masculine Form, and we expect this effect to be especially strong for the stereotypically masculine occupation (Hypothesis 7).

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Two hundred and twenty-two participants from lower (9th to 11th grades) and upper secondary levels, aged from 12 to 19 years old (M Age = 14.95; SDAge = 1.34) were recruited within the French-speaking region of Switzerland. Note that in the Swiss Education System, 9th to 11th is part of compulsory education (lower secondary level), whereas upper secondary level is part of post-compulsory education (Federal Statistical Office - Section Educational Processes, n.d.). The inclusion criteria were to understand French fluently and not have participated in another study on gender-fair language and vocational aspirations in the previous years. As such, all students from the lower and upper secondary levels were eligible for the study regardless of the school section they were enrolled in.

Gender was assessed via the following self-identification question: “What is your gender?” for which they could select “Girl” (n = 149) or “Boy” (n = 64) or “Other” (n = 9). Note that our upper secondary level cohort was mostly composed of girls (89%). While there are differences in gender distributions in education, with 27% of girls and 18% of boys receiving a diploma from baccalaureate schools in Switzerland (Office fédéral de la statistique, 2021), the overrepresentation of girls at upper secondary level in our sample is most likely due to selection bias in that these girls were overrepresented in the classes that consented to participate in the study. As such, and as mentioned earlier, girls at upper secondary level were only included in an additional analysis focusing exclusively on girls (lower and upper secondary levels).

Our main analysis is therefore exclusively based on girls and boys at the lower secondary level (n = 121; 62 girls; M Age = 13.96; SDAge = 0.83) whereas our secondary analysis is exclusively based on girls at the lower and upper secondary levels (n = 149; 87 girls at upper secondary level; M Age = 15.28; SDAge = 1.37). The sample from the lower secondary level was characterised by different school levels: n = 67 in the “p” section (i.e., a section that prepares for the upper secondary level and further education at university, high requirements), n = 32 in the “m” section (i.e., “modern,” intermediate requirement) and n = 19 in the “g” section (i.e., “general,” basic requirements). Three participants selected “other” (EDK CDIP CDEP CDPE, 2024). Participants in upper secondary level were mostly in baccalaureate schools (leading to universities) (n = 84), and the remainder (n = 3) were in general studies, which can give access to Universities of Applied Sciences. None of the participants were involved in vocational training.

Participants were excluded from the analyses if they did not identify as girl or boy (n = 9), answered without properly reading the instructions (e.g. answering similarly to all items of Good et al.’s scale for at least two occupations; n = 13) and did not entirely complete the experiment (n = 40).

The teachers responsible for overseeing the execution of the experiments signed a consent form, while parental consent was not requested for participation in this study, as it is in line with the school’s mission on vocational aspirations. Participants were informed that they could stop at any point. The study is in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Fribourg granted ethical approval for the study.

2.2 Materials and Procedure

2.2.1 Construction of Job Descriptions

We selected a stereotypically masculine, a stereotypically feminine, and a neutral occupation based on Misersky et al.’s (2014) classification, although their sample was slightly older than ours (M = 21.11, SD = 3.28). In this classification, a higher mean represents a higher estimation of the number of women in a given occupation. The mean rating in French was M = 0.42, SD = 0.04. We thus chose nurse as the feminine occupation (M = 0.72, SD = 0.13) because it is a stereotypically feminine essential healthcare occupation, surgeon as the masculine occupation as it is the most stereotypically masculine healthcare occupation (M = 0.3, SD = 0.13) and clinical psychologist as the gender-neutral healthcare occupation (M = 0.58, SD = 0.12; see Appendix 1). For each occupation, we then created descriptions detailing the particularities of each of their occupational functions. Critically, these descriptions took into consideration the three title conditions. More specifically, the descriptions referred to the group of people composing the occupation as “People” (Les personnes) in the No title condition, the occupation name in the grammatically masculine form in the Masculine condition, as in “Les infirmiers[MASC]” (men nurses or generically interpreted nurses), and the occupation name in the grammatically feminine and masculine form in the Pair Form condition, as in “Les Infirmières[FEM] et infirmiers[MASC]” (women and men nurses). We did not add a condition in which the feminine form was presented alone, as the grammatical feminine form is exclusive (i.e., only referring to women or girls), hence providing little insight into general adolescents’ interests and anticipated sense of belonging (especially for boys). Each description comprised five paragraphs containing between 11 and 13 sentences and ranging from 173 to 192 words depending on the title condition (see Appendix 3). The title condition was manipulated 5 times throughout each of the five-paragraph-long descriptions. In the No Title condition, neutral expressions were sometimes used (e.g “these people” or “this job”) instead of “people who do this job” to prevent cumbersome text.

We drew inspiration from Switzerland’s official information portal for vocational, academic and career guidance (Le Portail Officiel Suisse d’information de l’orientation Professionnelle, Universitaire et de Carrière, n.d.). Each description of the three occupations included three positive traits related to communion and three positive ones related to agency to maintain the focus on the occupation title. These traits were selected from Abele et al.’s (2008) corpus (see Appendix 2). Passive constructions were used to circumvent the use of adjectives that would require agreement with the gender of the human referent in the sentence. For instance, “show understanding” was used instead of “are understanding,” resulting in “ont de la compréhension” instead of “sont compréhensives[FEM] ou compréhensifs[MASC]” in French.

We conducted a pretest on the No Title condition descriptions to ensure that even without the title, they would still activate the occupation that we were interested in. For example, we wanted to ensure that by removing the title of nurse, participants would not consider the description as one of surgeon, most likely biasing the results. In line with Misersky et al.’s sample (2014) from which we extracted the stereotypicality of our occupations, 31 first-year Bachelor students were recruited for the pretest. They were presented with the occupation descriptions in the No Title condition and were asked to estimate, for each target occupation, on a 0–100% scale, the probability for each description to fit each of the three occupations. Results of the pretest showed that participants were able to guess the correct occupation described in the condition without any title (M Nurse = 95.81, 95% CINurse [92.98, 98.63]; M Surgeon = 88.32, 95% CISurgeon [79.58, 97.07]; M ClinicalPsychologist = 96.29, 95% CIClinicalPsychologist [93.45, 99.13]). As such, our pretest confirmed that the content of our items was well-suited (even when the title was missing).

Detailed information about the pretest and all materials can be downloaded in the Open Science Framework (OSF) following this link: https://osf.io/fwkh7.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Interest

We assessed participants’ level of interest in each occupation using a single item, a common method in studies on adolescents’ and undergraduates’ aspirations (e.g. Diekman et al., 2010, 2011; Fox & Barth, 2017; Iacoviello et al., 2024; Tellhed et al., 2017; Veldman et al., 2021; Vervecken et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2024). This method was chosen due to the time constraints of the class period. The specific question was: “How interested are you in [this occupation (No Title)/occupation in the Masculine Form/occupation in the Pair Form?”] on a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Not interested at all; 5 = Very interested) based on Fox and Barth (2017).

2.3.2 Anticipated Sense of Belonging (Two Scales)

As this measure has not been widely used in studies on children and adolescents, we employed two distinct scales for the anticipated sense of belonging. Furthermore, employing two measures of anticipated sense of belonging provided a comprehensive measure that ensured that the subtleties of this dimension were addressed.

The first of the two scales is a composite scale and is specific to educational and vocational belonging, as well as to the population of children and adolescents. This scale incorporates items from various scales, with all items being positively framed to avoid any confusion. More specifically, this scale consists of a total of five items, three of which were inspired by Murphy and Zirkel’s (2015) anticipated educational belonging scale: (1) “If you were to do this job, would you feel like you belong to the group of people doing this job? (No Title) or “If you were a [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form] would you feel like you belong to the group of people doing this job?”; (2) “If you were to do this job, do you think you would feel comfortable? (No Title) or “If you were a [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form], do you think you would feel comfortable?”; (3) “If you were to do this job, do you feel like you could ‘be yourself’ (No Title)?” or “If you were a [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form], do you feel like you could ‘be yourself’?”). The remaining two questions were inspired by vocational belonging studies: (1) “If you were to do this job, do you think you would feel proud?” (No Title) or “If you were a [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form], do you think you would feel proud?” (Baskaya et al., 2020) and (2) “If you were to do this job, do you think you would get along with the people doing this job?” or “If you were a [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form], do you think you would get along with the people doing this job?” (Cheryan et al., 2013) (Appendix 4.1).

For the second scale, we adapted two dimensions from Good et al.’s (2012) Sense of Belonging to Math scale to create an anticipated sense of belonging scale. This scale, which participants respond to on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all; 5 = Yes, for sure) (see Appendix 4.2), consists of positive and negative feelings, and was developed for a slightly older population (undergraduate) to measure their current feeling of belonging to mathematics majors. Using this scale allowed us to explore various constructs, including acceptance and affects. Negative items were reverse-coded so that the highest score meant a higher level of anticipated sense of belonging (Cronbach’s α = 0.88). The question was: “If you were to do this job […]” (No Title) or “If you were [occupation in the Masculine Form or in the Pair Form] […]” followed by items of the two dimensions presented in a random order for each participant. There was a positive correlation between the two scales, r(122) = 0.75, p < 0.05.

2.4 Design and Procedure

Participants were presented with the three occupational descriptions in a randomised order. Participants were randomly and evenly assigned to one of the three title conditions: (1) excluding the occupation title (No Title), (2) including the occupation title in the Masculine Form, or (3) including the occupation title in the Pair Form. Each participant was presented with the three occupations (one of each stereotype) in the title condition to which they were assigned. While Fox and Barth (2017) presented brief descriptions of occupations in their experiments, we gave participants more detailed information to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the presented occupations.

All data were collected during school time via a self-administered questionnaire online via the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, 2022, https://www.qualtrics.com/) on Samsung Galaxy Tab A7 tablets. Two women experimenters gave the instructions verbally and supervised the classroom during data collection. The participants were told that the aim of the questionnaire was “to know more about what they think about certain occupations.” The experimenters explicitly reassured the participants that there were no correct or wrong answers. Participants initially completed some sociodemographic questions, which were then followed by the main experimental questionnaire.

3 Results

To address our hypotheses, we analysed the data with a three-way mixed-design ANOVA for interest, as well as for anticipated sense of belonging, with Participant Gender (Girl; Boy) and Title (No Title; Masculine Form; Pair Form) as between-participant factors and Stereotype (Feminine; Masculine; Neutral) as a within-participant factor. Although incorporating participants’ educational level in the analysis would have provided valuable insights, the size of our sample would have resulted in overly small groups and compromised statistical power. As mentioned above, we also conducted separate analyses on girls at upper and lower secondary levels in order to include to include this cohort. That is, we analysed their data with a two-way mixed-design ANOVA for each dependent variable (i.e., interest, anticipated sense of belonging) with Title (No Title; Masculine Form; Pair Form) as a between-participant factor and Stereotype (Feminine; Masculine; Neutral) as a within-participant factor. All analyses can be found on the OSF repository: htts://osf.io/fwkh7.

3.1 Primary Analysis: Girls and Boys at the Lower Secondary Level

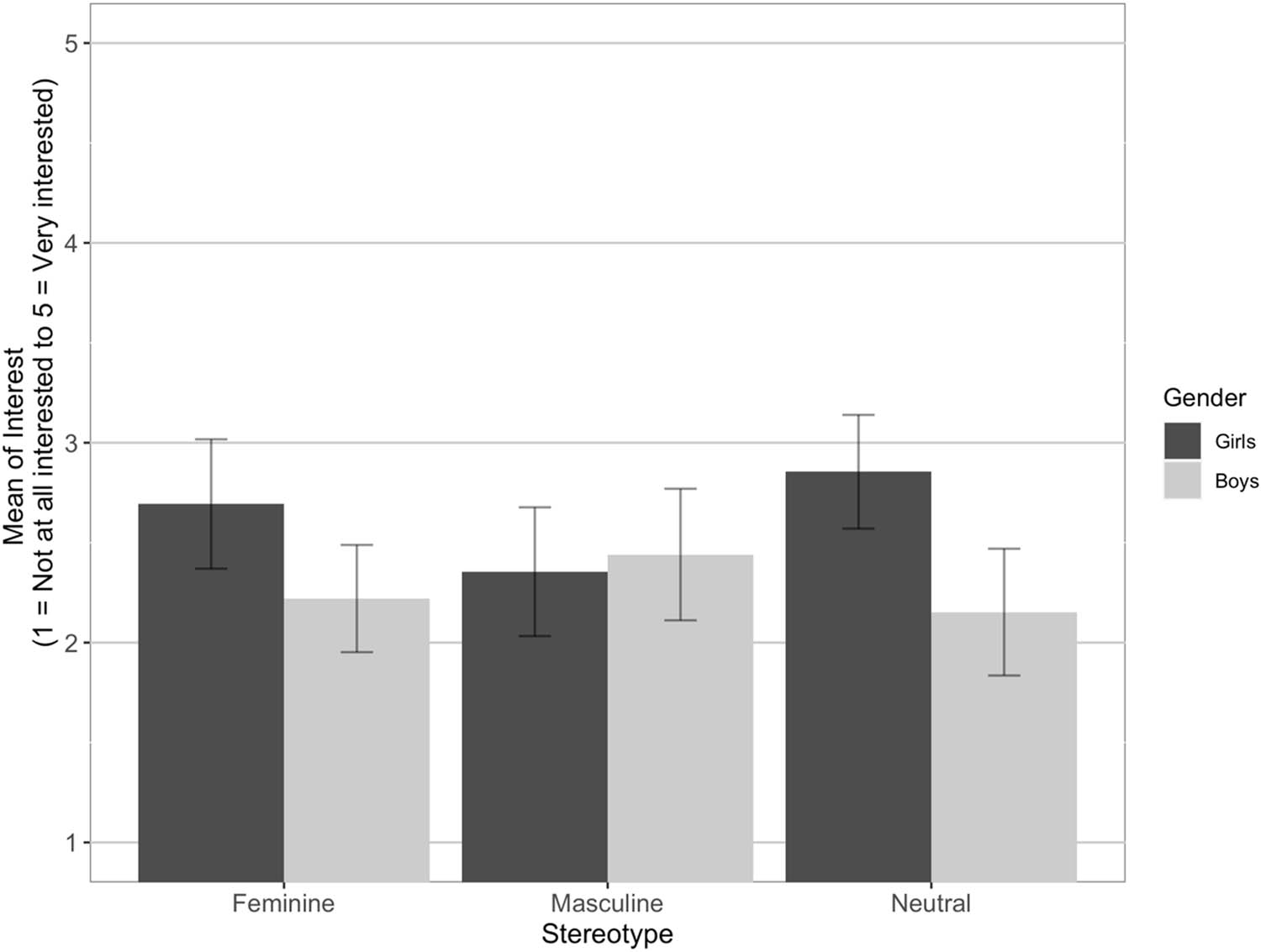

3.1.1 Interest

In contrast to our expectations, neither the main effect of Title, F(2, 115) < 1 (Hypothesis 1) nor the interaction Title by Gender, F(2, 115) < 1, was significant (Hypothesis 2). The analysis revealed a main effect of Gender, which we did not expect, F(1, 115) = 4.44, p < 0.05,

Mean of interest values as a function of occupational stereotype (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) for girls and boys at the lower secondary level (1 = Not at all interested; 5 = Very interested).

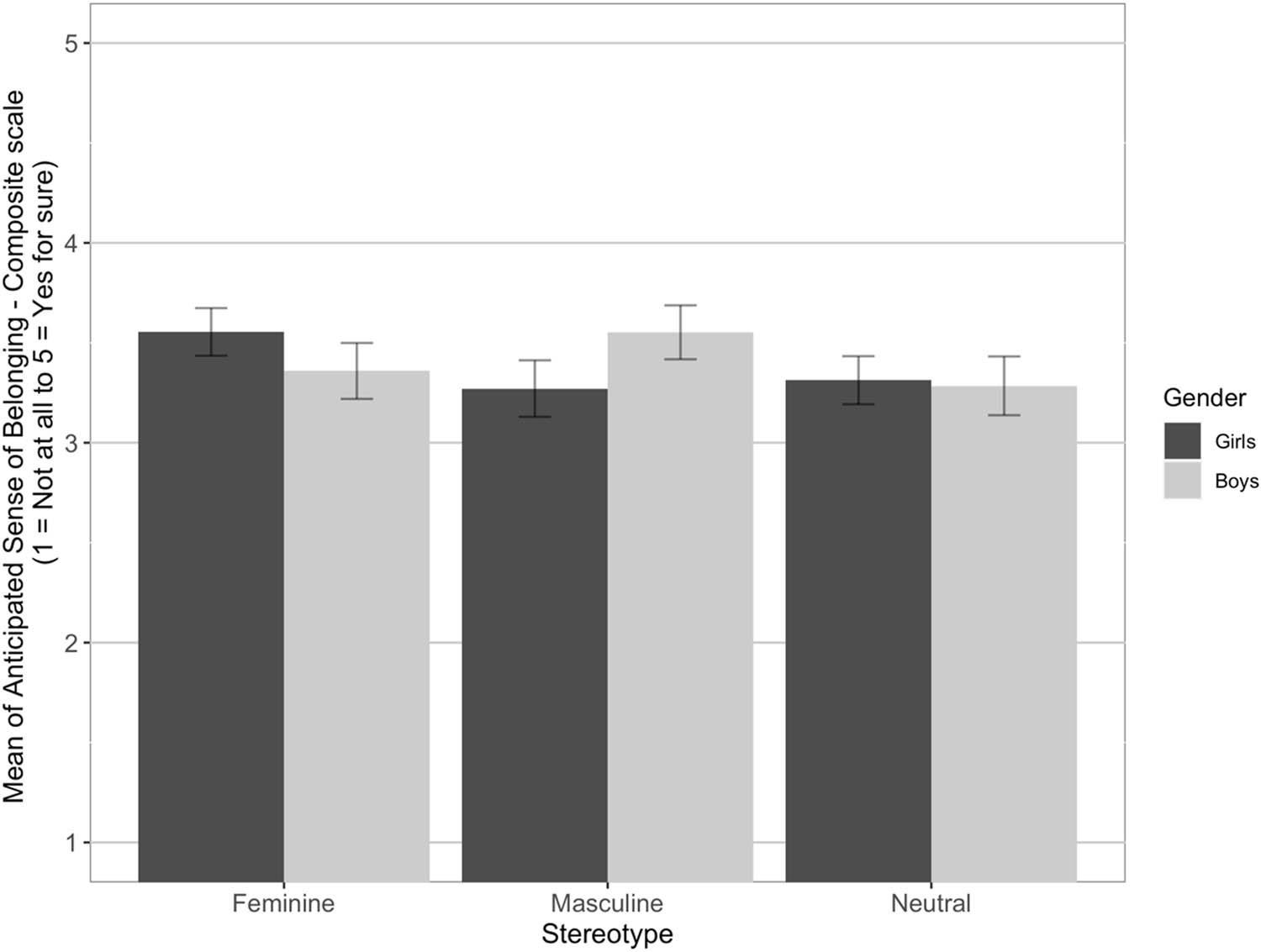

3.1.2 Anticipated Sense of Belonging – Composite Scale (Cronbach's α = 0.80)

The mixed ANOVA revealed that neither the main effect of Title (Hypothesis 1) nor the Title by Gender interaction (Hypothesis 2) was significant (both F < 1). There was, however, a significant Gender by Stereotype interaction in line with Hypothesis 3 (Figure 2), F(1.88, 216.17) = 3.81, p < 0.05,

Mean of Anticipated sense of belonging (composite scale) values as a function of occupational stereotype (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) (1 = Not at all; 5 = Yes, for sure) for girls and boys at the lower secondary level.

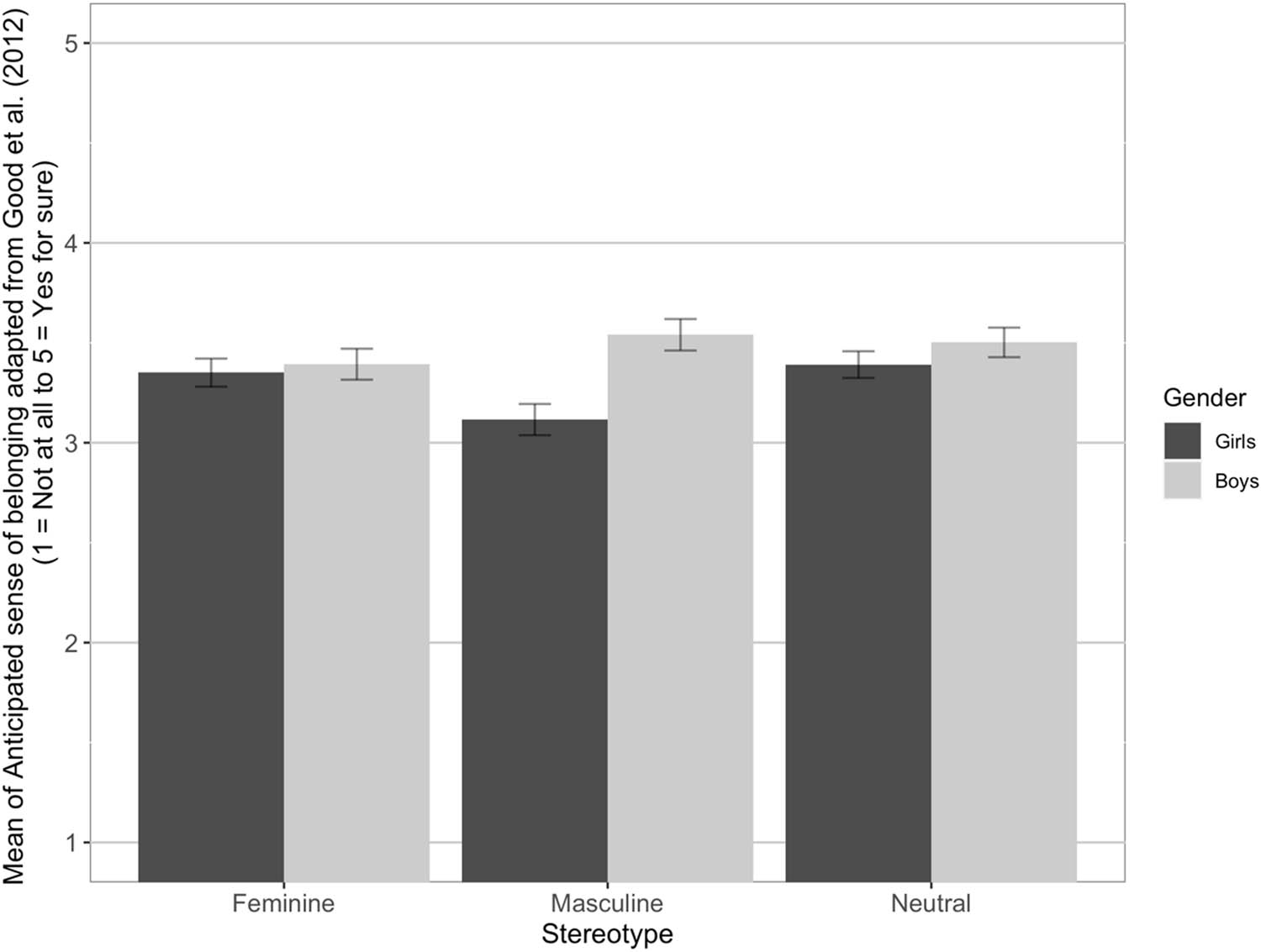

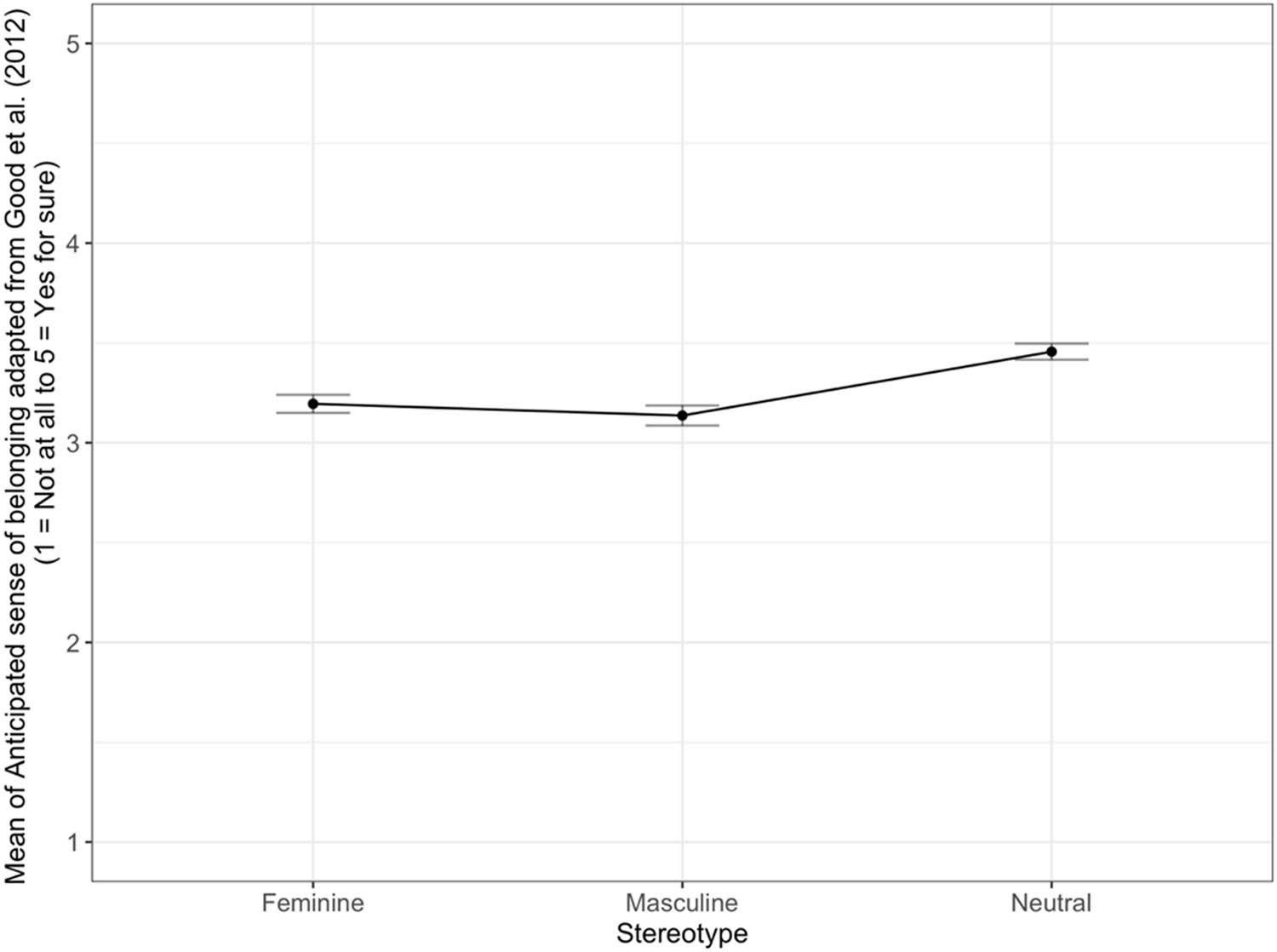

3.1.3 Anticipated Sense of Belonging – Acceptance and Affect Adapted from Good et al. (2012) (Cronbach’s α = 0.88)

Participants showed an average mid-scale anticipated sense of belonging (M

Belonging = 3.38, SDBelonging = 1.19). The mixed ANOVA revealed that neither the main effect of Title (Hypothesis 1), F(2, 115) < 1, nor the interaction Title by Gender (Hypothesis 2) was significant, F(2, 115) < 1 (with Greenhouse–Geiser correction). As expected, results showed a Gender by Stereotype interaction effect, which also supports Hypothesis 3, F(1.93, 222.06) = 5.79, p < 0.05,

Mean of Anticipated sense of belonging (adapted from Good et al., 2012) values as a function of occupational stereotype (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) (1 = Not at all; 5 = Yes, for sure) for girls and boys at the lower secondary level.

3.2 Secondary Analyses: Girls at the Lower and Upper Secondary Levels

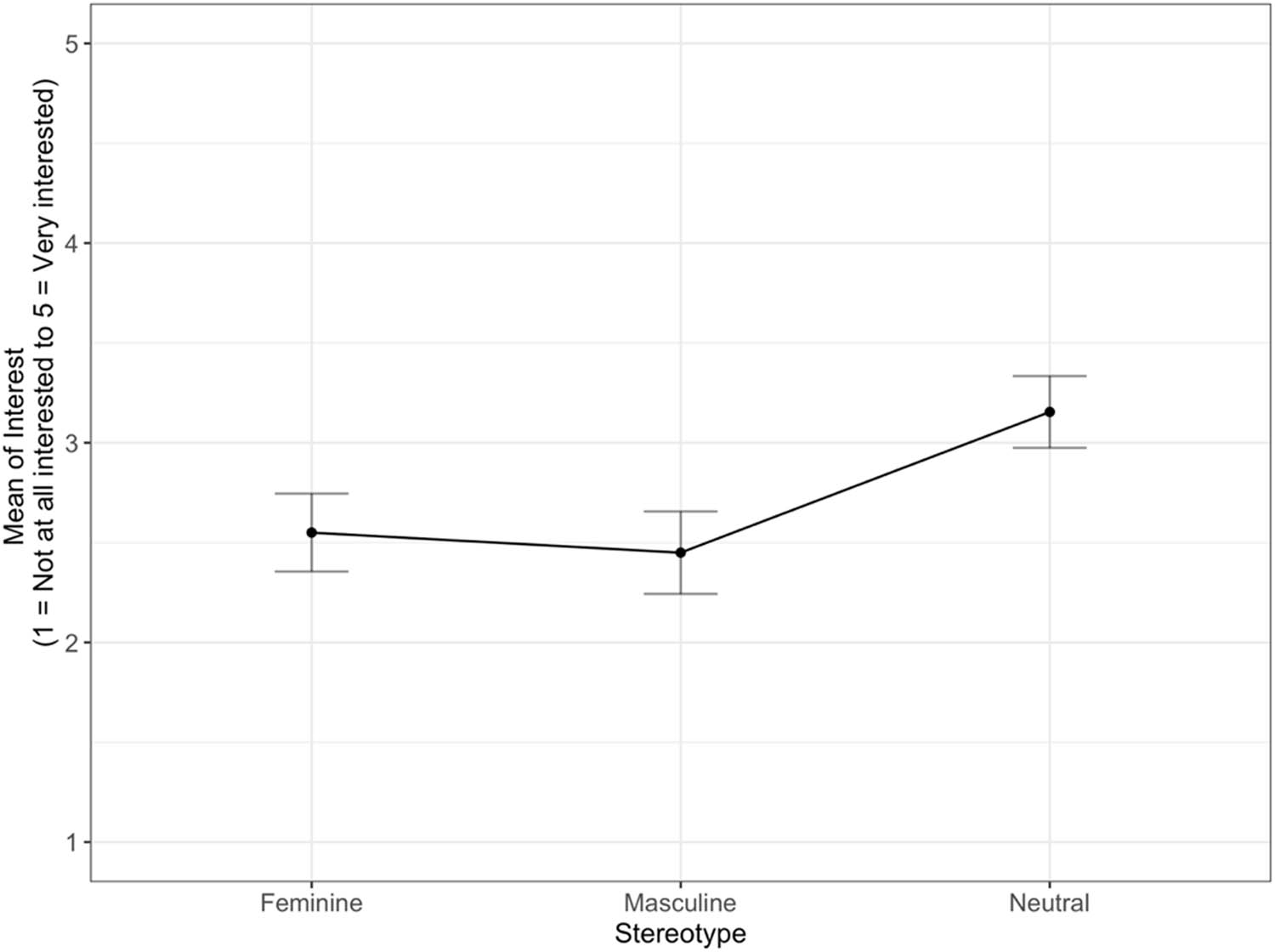

3.2.1 Interest

In contrast to our expectations, neither the main effect of Title, F(2, 146) < 1 (Hypothesis 5) nor the interaction Title by Stereotype, F(3.56, 259.79) = 1.77, p > 0.05, were significant (Hypothesis 7). The analysis revealed a main effect of Stereotype, F(1.78, 259.79) = 21.83, p < 0.05,

Mean of interest values as a function of occupational stereotype (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) for girls at the lower and upper secondary levels (1 = Not at all interested; 5 = Very interested).

3.2.2 Anticipated Sense of Belonging – Composite Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.73)

On the composite scale, girls showed an average mid-scale anticipated sense of belonging (M Belonging = 3.40, SDBelonging = 1.10). The mixed ANOVA revealed that none of the expected effects was significant; neither the main effect of Title, F(2, 146) = 1.59, p > 0.05 (Hypothesis 5), nor the main effect of Stereotype, F(1.90, 276.95) = 1.12, p > 0.05 (Hypothesis 6), nor the interaction Title by Stereotype, F(3.79, 276.95) = 1.34, p > 0.05, were significant (Hypothesis 7).

3.2.3 Anticipated Sense of Belonging – Acceptance and Affect Adapted from Good et al. (2012)

On the anticipated sense of belonging adapted from Good et al. (2012) (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), girls showed an average mid-scale anticipated sense of belonging (M

Belonging = 3.26, SDBelonging = 1.14). Neither the main effect of Title, F(2, 146) = 1.64, p > 0.05 (Hypothesis 5) nor the interaction Title by Stereotype, F(3.74, 272.67) = 1.10, p > 0.05, were significant (Hypothesis 7). However, the analysis revealed a main effect of Stereotype, F(1.87, 272.67) = 18.53, p < 0.05,

Mean of Anticipated sense of belonging (adapted from Good et al., 2012) values as a function of occupational stereotype (with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals) (1 = Not at all; 5 = Yes, for sure) for girls at the lower and upper secondary levels.

4 Discussion

The study presented in this article aimed to investigate (1) the impact of gender stereotypes on adolescents’ vocational aspirations in healthcare occupations and (2) the possibility for them to be attenuated by using various title conditions (No Title, Masculine Form, or Pair Form). The No Title condition was inspired by Fox and Barth’s (2017) study, and the Pair Form condition was based on a large body of evidence of the alleviating effect of this form on gendered vocational representations. Our study was based on adolescents at the lower and upper secondary levels. Due to the gender imbalance in the upper secondary level (i.e., majority of girls), we conducted two separate sets of analyses. A first set based on girls and boys at the lower secondary level, and a second based exclusively on girls from both the lower and upper secondary levels.

Compared to Fox and Barth’s (2017) seminal study, whose sample was only composed of men, our study provides different results on adolescents’ interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to gender-stereotyped occupations. First of all, our first sets of analyses revealed a Gender by Stereotype interaction (Hypothesis 3) in that girls were more interested in the neutral and feminine occupations than boys. However, the difference between girls and boys in their interest in the stereotypically masculine occupation was not significant. As for the anticipated sense of belonging, boys did show a significantly higher level of anticipated sense of belonging to the masculine occupation than girls did. Overall, this is reminiscent of research on gender stereotypes and vocational aspirations that demonstrated that adolescent girls and boys anticipate a higher sense of belonging to domains in which their gender group is dominant (e.g. Tellhed et al., 2017). Our findings also echo results showing that a masculine-stereotyped environment decreases women’s, but not men’s, sense of belonging (Cheryan et al., 2009). Still, girls’ level of interest was more similar across stereotypically feminine and masculine occupations than boys’. This is in line with Wood et al. (2022), who found that 13–15 years old boys in the UK tend to select more gender-congruent stereotypical school subjects than girls, who tend to choose a more equitable proportion of each. Similarly, in Switzerland, 19.1% of girls of the same age range aspire to counterstereotypical careers in Switzerland, whereas only 6.7% of boys do (Guilley et al., 2014).

Interestingly, analyses exclusively on girls (lower and upper secondary levels) revealed a main effect of stereotype (Hypothesis 6) on girls’ levels of interest in, and anticipated sense of belonging to the presented occupations. Girls showed significantly higher levels of interest in, and levels of anticipated sense of belonging to, the neutral occupation than to the stereotypically feminine and masculine ones.

The results regarding the neutral occupation might appear surprising, yet one could argue that the occupation of clinical psychologist slightly leans towards the feminine stereotype (Guilley et al., 2014; Misersky et al., 2014). In fact, although clinical psychologist was a masculine occupation until the eighties in Switzerland (Nguyen, 2018), clinical psychology encompasses feminine-stereotyped traits such as empathy (Harton & Lyons, 2003). A recent study on Swiss adolescents aged 13–15 years, in fact, showed that clinical psychologist was perceived as mostly neutral in terms of gender yet with a slight bias towards feminine stereotypes (Guilley et al., 2014). This may partly explain girls’ high interest in and anticipated belonging to this occupation.

In line with Social Role Theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012), our results show the self-perpetuating nature of gender stereotypes, as they seem to influence adolescents’ career interests. Additionally, our findings suggest that girls might be driven by system-justification motives, in that their aspirations are consistent with the gender stereotypes. One could argue that our experiment made gender too salient, similar to Bonnot and Jost’s (2014) study, in which girls underestimated their competence in maths when system justification concerns were made prominent. Note that the more unfair the system is, the higher the need to justify it (Jost & Banaji, 1994). As careers are key in shaping gender inequalities and gender identities, girls might have been more inclined to adopt a justification approach.

One limitation of our study (next section provides more limitations) lies within the possible confound of prestige. Namely, it would have been valuable to include a self-report measure of participants’ perception of the prestige of each occupation. While prestige could be measured based on salary (e.g. Vervecken & Hannover, 2015), it could also be based on required education (Guilley et al., 2014) and/or difficulty (Vervecken & Hannover, 2015). Most importantly, the perception of prestige may also be influenced by characteristics of respondents, such as gender and/or social class (Guilley et al., 2014). As such, girls may perceive clinical psychology as being more prestigious than boys (Guilley et al., 2014). We would thus argue that stereotype and prestige might play together in girls’ interest in and anticipated sense of belonging to clinical psychologist. Note that the present study was conducted in 2022, two years after the first worldwide COVID-19 outbreak. During the pandemic, nursing has been at the centre of social discourse, leading to a better recognition of their work (Monteverde & Eicher, 2023). However, despite their depiction as heroes, media coverage has also underlined their challenging working conditions (Monteverde & Eicher, 2023). The impact of such depictions on adolescents’ interest in this career may be difficult to accurately capture, but one could argue that the anticipation of such working conditions might undermine their aspirations for nursing compared to those for clinical psychology.

Contrary to our expectations, there was neither a main effect of Title (Hypothesis 1), nor any interaction effects involving Title (Hypotheses 2, 4, and 7). Our participants, whether girls or boys, were never affected by seeing (either in the Masculine form or in the Pair Form) or not seeing the titles of the occupations they were presented with. As such, the present study failed to replicate Fox and Barth’s (2017) findings regarding the presence or absence of a title, as removing the title of the presented occupations did not increase participants’ interest in any of them (e.g. counter-stereotypical occupations). Similarly, our results do not align with the existing literature on gender-fair language and vocational aspirations, as the Pair Form did not yield more gender-balanced representations. The absence of the effect of our linguistic manipulation might suggest that the effect of stereotype may be potentially stronger than that of the title, which could be attributed to multiple reasons. First and foremost, our study differs from that of Fox and Barth (2017) and from the literature on gender-fair language (e.g. Chatard et al., 2005; Vervecken & Hannover, 2015) in that adolescents were presented with detailed descriptions. The additional information might have drawn their attention to other gender-stereotyped cues other than the linguistic form. Second, girls’ levels of interest in the masculine occupation were not significantly different from those of boys. As such, despite the demonstrated benefit of the pair form (a) on the perception of women’s and men’s success (e.g. Vervecken et al., 2015), (b) on girls’ interest in stereotypically masculine occupations (e.g. Vervecken et al., 2013), and (c) girls’ self-efficacy in these fields (e.g. Chatard et al., 2005), the use of gender-fair language might still not be sufficient to enhance their anticipated sense of belonging. Third, evidence on the effect of gender-fair language on boys’ aspirations remains ambiguous. While some studies found no effect of this linguistic manipulation on boys’ vocational interest (Vervecken et al., 2013), some studies have shown linguistic manipulations to increase boys’ self-efficacy in stereotypically feminine occupations (Chatard et al., 2005), and more gender-balanced perception of success in stereotypically feminine occupations (Vervecken et al., 2015). Based on these findings, we expected this linguistic form to attenuate the effect of gender stereotypes. However, one explanation for the lack of such an effect may stem from the low status of stereotypically feminine occupations, as well as the fact that the pair form may not change this status (Vervecken & Hannover, 2015). In fact, some studies suggest that boys often prioritise salary when considering their aspirations, whilst girls tend to be motivated by the opportunity to help others (Barth & Masters, 2024). In addition, nursing has always, historically, been considered a subordinate occupation (Teresa-Morales et al., 2022; Toffel, 2020), associated with feminine stereotypes, low salary, low status and low prestige (Teresa-Morales et al., 2022). In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, where the present study was conducted, nurses still face challenges in gaining autonomy and legitimacy within the healthcare system despite the academisation of nursing training (Toffel, 2020).

Overall, our findings suggest several practical implications. First, our results suggest that linguistic interventions might not always suffice and that other interventions should be combined with the use of gender-fair language to mitigate occupational stereotypes. Some have suggested that enhancing recognition, societal status, and remuneration for communal roles could effectively promote healthcare careers such as nursing (e.g. Diekman & Benson-Greenwald, 2018; Michel & Ecarnot, 2020; Olsen et al., 2022). Simultaneously, considering communality and agency as either feminine or masculine, as well as being constrained to stereotypically feminine or masculine occupations, should be challenged (e.g. Diekman et al., 2017). This approach might be beneficial to prevent girls’ low anticipated sense of belonging to stereotypically masculine occupations (e.g. Diekman et al., 2015, 2017). Additionally, communal traits could (and should) be encouraged regardless of gender (Twenge, 2009). Some authors recommend eliminating gender stereotypes in nursing advertisements, for example, by avoiding the use of feminine terms only, to enhance the visibility of professional skills and responsibilities (e.g. Teresa-Morales et al., 2022). As such, nurses’ autonomy would be highlighted as it may benefit adolescents’ interest in this occupation (Cohen et al., 2004), especially as Generation Z (i.e., individuals born between the mid-1990s and the early 2010s) value creativity in their vocational aspirations (Barth & Masters, 2024). As a final note, although concealing the title is an interesting experimental manipulation (Fox & Barth, 2017), its practical feasibility is limited, as using such a presentation in vocational guidance materials could raise ethical concerns and may be misleading for adolescents.

Although inspired by Fox and Barth (2017), the present study differed from the latter in several ways, and each could explain why we did not replicate their findings on the effect of No Title. First, we ran a pre-test to ensure that participants would be able to recognise the occupation described in the No Title condition, which Fox and Barth (2017) did not, at least to our knowledge. By removing the title, Fox and Barth (2017) may have changed the perceived occupation, which may explain some of their findings. For instance, the description of nurse is rather broad and could apply to other healthcare occupations with different levels of prestige and gender stereotypicality (e.g. general practitioners or even surgeons). Consequently, boys in Fox and Barth (2017) might have found it easier to consider the occupation in the No Title condition because they may have understood the occupation described as being something other than nursing (i.e., surgeon). Moreover, despite the presence of stereotypically feminine adjectives in the descriptions, removing the title may have allowed boys to explore their interests more easily. This is reminiscent of an early study on this topic (Jessell & Beymer, 1992), in which videotapes of a woman and a man narrator talking about 18 occupations (including healthcare occupations) were shown to adolescents, making the title manipulation more salient (i.e., in one condition narrators only read the occupation title while in the other condition, participants would listen to a description of occupations without the title of the occupation being given). The study showed that the occupation title activated a more gender-stereotyped representation of occupations, whereas not mentioning the title allowed participants to explore their interests based on the descriptions (Jessell & Beymer, 1992). Second, we had a more heterogeneous and younger sample than Fox and Barth (2017), who conducted their study on STEM students. Our sample contained a wide age range (from 12 to 19 years old) from different French-speaking cities of Switzerland. As opposed to the STEM students in Fox and Barth’s (2017) study, our participants were still in lower and upper secondary levels. Therefore, they had not engaged in any specific curriculum yet and were at a different stages of career commitment than those of Fox and Barth (2017). This might explain the strong stereotype effect we found, with adolescents grounding their responses in undocumented and thus shallow information. We further discuss the limitations of our sample in the Limitations. Third, we provided our participants with longer job descriptions than those used by Fox and Barth (2017). We posit that those longer descriptions may have decreased the saliency of the title manipulation and may have caused some attentional shift away from the actual titles. In our study, we presented the occupation title five times in each description, yet excluded it in the final paragraph. Fox and Barth (2017) presented the occupation title once in a two-sentence description, which might have made their title manipulation more salient. Fourth and finally, we balanced the feminine and masculine stereotypical traits in our descriptions. Namely, the presented occupations were stereotypically gendered, but we did not manipulate the descriptions in terms of making them more or less stereotypical, as we balanced the number of agentic and communal adjectives in each description. One could argue that this reduced the attention to stereotypicality, yet this is rather implausible, as stereotype effects did emerge. In fact, we would argue that the mere presence of stereotypical traits (whether feminine or masculine) may render stereotypes salient. This is reminiscent of Gaucher et al. (2011), in which the mere presence of masculine-stereotyped adjectives in occupational advertisements increased the number of perceived men in stereotypically masculine occupations. Consequently, describing personal characteristics required for an occupation might consistently reinforce gender stereotypes, even if the characteristics are balanced in terms of stereotypes. Additionally, in the case of true balance, attentional mechanisms may not be equally divided among the information provided. Some studies have shown that information aligning with specific occupational stereotypes receives greater attention (Rothbart et al., 1979). In our case, adolescents might have focused more on agentic traits when presented with the surgeon and on communal traits in the two other conditions.

One solution to counter the reinforcement of stereotypes caused by merely mentioning stereotypical yet balanced personal characteristics could be to replace communal and agentic traits with gender-neutral traits. However, a downside of this is that personal adjectives/traits describing healthcare professionals might always have some sort of gender-stereotypicality attached to them.

4.1 Limitations of the Present Study

This study presents several limitations. First, due to the habitual constraints when testing in schools, our sample size was not ideal, especially in light of some of the interactions we explored. The limited sample size was further exacerbated by rather unbalanced gender distributions, forcing us to run separate sets of analyses. Given that our sample reflects a current reality in the population of the Swiss upper secondary level, in that girls are overrepresented (Office fédéral de la statistique, 2021), only a few boys at the upper secondary level participated in our study. A larger sample of boys would have allowed us to gain valuable insights into their aspirations for health careers, and, as a corollary, to conduct analyses that would have better controlled for educational attainment. The second set of analyses was informative about girls’ (12–19 years old) aspirations for the presented occupations, yet offered no comparison point with boys at upper secondary level. In other words, the conclusions from this set of analyses must be interpreted with caution, as they only apply to girls. Further studies with a more balanced sample are necessary to investigate (younger and older) boys’ aspirations for occupations in the health domain. Second, our age range was rather large and may have masked age differences. In fact, during this period, adolescents’ vocational aspirations (Gottfredson & Lapan, 1997) and adherence to gender stereotypes may evolve (Hoff et al., 2018). Both being intrinsically intertwined, as gender stereotypes have been shown to shape adolescents’ and young adults’ career choices and interests. Third, occupations were selected from Misersky et al.’s (2014) classification based on a slightly older population, as was our pretest. Young adults may have more extensive and diversified knowledge of the three occupations we tested. While we cannot exclude that our adolescents were not as able to distinguish them as well as undergraduates did, the fact that we still had strong stereotype effects seems to indicate that our population responses were in line with younger adults’ representations. Fourth, this study aimed to examine adolescents’ interest in, and anticipated sense of belonging to, only three healthcare occupations. Although adding more diverse occupations might be difficult in the constraints of testing in schools, a wider range of occupations would enable the generalisation of these results to other gender-stereotyped occupations. The results presented in this experiment might be specific to the three selected occupations. Importantly, it would have been beneficial to also factor in status/prestige, as it is most likely also a very important component of vocational interest. In fact, Gottfredson (1981) argued that stereotypically feminine occupations tend to be more homogeneous than stereotypically masculine ones in terms of prestige and status. Similarly, status has been frequently associated with occupational gender stereotypes, stereotypically masculine occupations benefiting from a higher status (e.g. Liben et al., 2001), and stereotypically feminine ones from a lower one (e.g. Teig & Susskind, 2008). Some have even shown that the highest-status feminine occupations are still perceived by children as lower than the highest-status masculine ones (e.g. Teig & Susskind, 2008). Fifth, in our experimental design, stereotype was a within-participant factor, which implies that participants rated their aspirations for all the occupations. As adolescents and university students tend to self-stereotype more in the context of intergroup social comparisons (i.e., women vs men) (Guimond et al., 2006), the forced comparison between gender stereotypical occupations might have reinforced the influence of stereotypes. Replicating the same study with Stereotype as a between-participant factor would provide valuable insights into the influence of comparison between gender stereotypical occupations on self-reported aspirations and its potentially undermining effect on the title manipulation. Finally, while the self-reported question “What is your gender?” aimed to gather information about participants’ gender identity, it cannot be excluded that participants reported the gender recorded on their official documents rather than the one they identified with. As such, asking participants with which gender they identify or to what extent they consider themselves as a woman, man, or outside of the dichotomy on different non-mutually exclusive scales would be more inclusive (Blondé et al., 2021).

4.2 Future Research

In this research, we analysed differences in vocational aspirations through the lens of gender (most specifically by comparing women and men), as society is marked by great gender inequalities in the workforce. Despite gender being an important factor to consider when investigating vocational aspirations, this research could benefit from a more intersectional perspective. For instance, socioeconomic status (Baxter, 2017; Howard et al., 2011), ethnicity (Howard et al., 2011), and parents’ occupations (Ramaci et al., 2017) are also of great influence on adolescents’ vocational aspirations and choices. Plus, when investigating gender work discrimination, one should bear in mind the concept of the glass escalator. This concept, theorised by Williams (1992), describes the process by which men access higher status and better-paying positions in stereotypically feminine occupations. The facilitation induced by gender is also highly influenced by race, as shown by Wingfield (2009); black men do not benefit from the same privileges as their white counterparts in nursing. While white masculinity is often associated with competence, which gives white men access to higher positions in nursing, black men nurses face discrimination from patients and peers. This discrimination is illustrated by the fact that white men nurses are often mistaken for doctors while people assume that black men nurses are janitors (Wingfield, 2009). Finally, as women represent many employees in care occupations (e.g. nursing), they are commonly referred to as “women-dominated occupations.” One must, however, be conscious of this expression since despite women being the majority of the workforce, men tend to have higher positions in these occupations (Hicks, 1999) and to be perceived as more competent (Zinn, 2019).

The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of gender-fair language and the impact of masking the occupation’s title on gender-stereotypical occupational preferences according to gender. In our experimental design, participants’ gender was considered an independent variable. For this reason, we did not add an open-text choice as we wanted to avoid missing data or absurd answers (Lindqvist et al., 2021). Therefore, the study forced participants to self-identify in strict gender categories. As a result, this experiment considers gender as very binary, which is not in agreement with the current conceptualisation of gender.

5 Conclusion

We conducted an experiment on adolescents’ gender-stereotypical vocational aspirations and the potential alleviating effect of various linguistic presentations, with a special focus on healthcare occupations. In line with a large amount of research, we observed a strong influence of gender stereotypes on adolescents’ vocational interest and anticipated sense of belonging. However, we did not find any effect of Title manipulations (i.e., removing the title or using gender-fair language) in decreasing stereotypical choices. Thus, interventions in promoting adolescents’ aspirations for the healthcare domain are needed, although increasing the social recognition for these occupations will be essential to enhance the value and attractiveness of these occupations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the schools that welcomed us for testing and the participants in this research. We also thank Joost van de Weijer for his careful review of the statistical analyses.

-

Funding information: The research reported in this article was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF; FN-501100001711-188841), awarded to Pascal Mark Gygax (PI), Ute Gabriel, and Jane Oakhill.

-

Authors contributions: LE: conceptualisation, methodology, data collection, data preparation, analyses, writing (original draft, editing), review. PG: funding, conceptualisation, methodology, review. SS: conceptualisation, methodology, review. UG: funding, conceptualisation, methodology, review. JO: funding, conceptualisation, methodology, review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethics approval: The heads of the schools gave their consent for their school to take part in this study. Participants were informed that they could stop at any point. The study is in line with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Fribourg granted ethical approval for the study.

-

Data availability statement: Experimental materials, data, and analyses of the pretest and the study can be downloaded on the Open Science Framework (OSF): htts://osf.io/fwkh7.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Gender stereotypes associated with selected occupations according to Misersky et al. ( 2014 ) and their title conditions in French

| Masculine Form (French) | Pair Form (French) | English | Mean in French (Misersky et al., 2014 ) | Gender stereotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Les infirmiers | Les infirmières et infirmiers | Nurses | 0.72 | Feminine |

| Les chirurgiens | Les chirurgiennes et chirurgiens | Surgeons | 0.3 | Masculine |

| Les psychologues cliniciens | Les psychologues cliniciennes et cliniciens | Clinical psychologists | 0.58 | Neutral |

Note. In Misersky et al.’s ( 2014 ) classification, a higher mean represents a higher estimation of the number of women in a given occupation. The mean rating in French was M = 0.42, SD = 0.04.

Appendix 2

Communal and agentic adjectives in Abele et al. (2008)

| Positive traits in French | Positive traits in English | Valence |

|---|---|---|

| Endurant | Industrious | Agentic |

| Indépendant | Independent | Agentic |

| Intelligent | Intelligent | Agentic |

| Rationnel | Rational | Agentic |

| Autonome | Self-reliant | Agentic |