Abstract

Continuing advances in computational chemistry has permitted quantum mechanical calculation to assist in research in green chemistry and to contribute to the greening of chemical practice. Presented here are recent examples illustrating the contribution of computational quantum chemistry to green chemistry, including the possibility of using computation as a green alternative to experiments, but also illustrating contributions to greener catalysis and the search for greener solvents. Examples of applications of computation to ambitious projects for green synthetic chemistry using carbon dioxide are also presented.

1 Introduction

While modern quantum mechanical models of electrons in atoms and molecules arose in the early twentieth century [1], molecular quantum calculation of molecules first began to become accessible to non-theorists with the first release of John Pople’s Gaussian package in 1970 [2]. In the intervening period, advances in theory and in computing technology have made computational chemistry, specifically quantum mechanical calculations of electrons in molecules, into a widely applied technique for research in spectroscopy, thermodynamics, and the mechanism and kinetics of chemical reactions [3]. Modeling of systems within solution is now a common practice [4].

Green chemistry is research or other activity focused on the reduction of toxicity in the practice of chemistry. Unlike “environmental chemistry”, an appellation which may be used to describe a wide range of research projects, green chemistry is generally recognized as being defined by a set of twelve guiding principles [5]. In its current state, computational chemistry plays a significant role in “green” research. This chapter does not provide an exhaustive list of all of the contributions of quantum chemical computations to green chemistry, but it will show a number of intriguing examples. Computational chemistry is integral to research efforts seeking greener catalysts and to finding greener methods of testing potential catalysts for efficacy. It plays a role in investigations toward greener solvents for reactions and extractions. It provides thermodynamic and kinetic information on novel efforts to transform carbon dioxide emissions from a source of pollution to a renewable feedstock for production of useful polymers. These examples will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

2 Greening catalysis – enzyme design

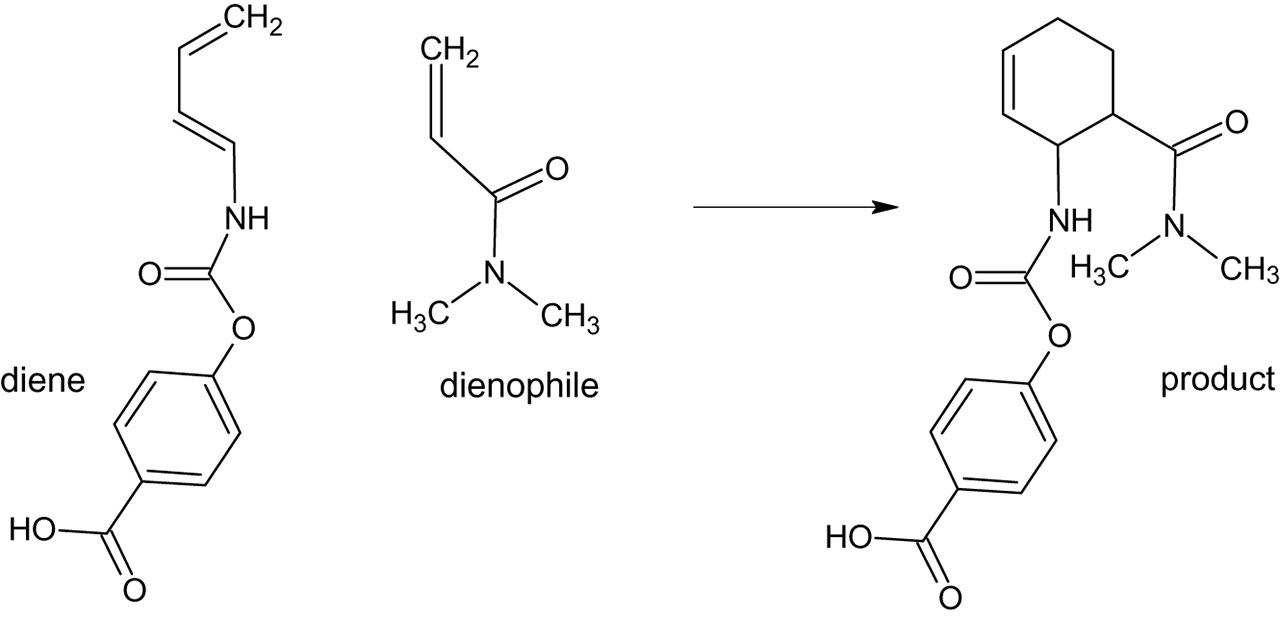

The ability to study chemical reaction pathways computationally provides a means to test reaction catalysts in silico before moving on to test promising candidates in laboratory synthetic efforts. Research of this sort has appeared in recent years in eminent publications such as Science [6], and a very recent volume of Accounts of Chemical Research has been devoted to the topic of “Computational Catalysis for Organic Synthesis” [7]. The goal of such synthetic research may be to improve stereoselectivity of products or increases in yield [6], but the methodology often simultaneously provides a possible “greening” of the synthetic process. For example, a recent article in Science [6] concerns design of an enzyme catalyst for a reaction familiar to any student of organic chemistry, the Diels-Alder synthesis. This work furthers the goal [8] of using organic catalysts to catalyze Diels-Alder syntheses, as opposed to traditional catalysts, which include toxic Lewis Acids such as boron trifluoride or tin tetrachloride [9, 10. 11]. The solvent used for experimentally implementing this enzyme is water [6], and so this work provides a very “green” example of a Diels-Alder synthesis. The Diels-Alder reaction selected is the reaction of 4-carboxybenzyl trans-1,3-butadiene-1-carbamate as the diene and with N,N-dimethylacrylamide as the dienophile. The reaction is displayed in Figure 1.

Diels-Alder reaction chosen for reference 6.

The work is an implementation of the Rosetta methodology [12] in enzyme design, in which the transition state and active site for the reaction going from substrate to product is located by quantum mechanical molecular orbital calculations and then structurally matched into a protein “scaffold” obtained from a database. The design in this work creates a “pocket” active site into which both substrates are held in an optimal encounter geometry for reaction and positioning of a hydrogen bond acceptor to interact with the NH moiety on the carbamate diene and a hydrogen bond donor to interact with the carbonyl on the dienophile. The hydrogen bond to the carbamate raises the energy of the homo on the diene, while the hydrogen bond to the dienophile stabilizes its LUMO; the net effect, in addition to holding the two molecules in position for reaction, is a reduction of the energy difference between the LUMO and the HOMO, resulting in a faster reaction rate. Siegal et al. [6] estimate that the hydrogen bonding lowers the energy of the transition state by approximately 4.7 kcal/mol.

Insertions into available protein scaffolds initially produced 84 prospective catalytic enzymes, two of which were experimentally found to have catalytic ability; additional improvements in catalytic activity were obtained by mutating the structures of enzymatic residues around the transition state. A feature of the design of the active site is that it is very stereospecific, this is in fact observed in the experimental distribution of products (>97 % for the specific isomer).

Enzyme design using a computationally designed active site is often referred to as a “theozyzme” approach [13, 14]; there is also a more empirical “minimalist “approach which does not employ quantum mechanical calculations and instead attempts to design de novo enzymes by matching desired function to known details of enzyme structures [15]. This latter approach tends to produce less efficient catalysts than the quantum-computational approach,, but it is less computationally expensive; recent work discusses this trade-off, and illustrates the possible efficacy of the minimalist approach by presenting a retroaldolase catalyzing the reverse aldol condensation of methodol [16].

With respect to green chemistry, catalysis with engineered enzymes offers the possibility of replacing toxic catalysts with non-toxic protein catalysts; additionally, the solvent for enzymatic catalysis is water, clearly a greener choice than organic solvents [16].

3 Greening catalysis – “in silico” experiments

A very common computational approach to studying the kinetics and catalysis of a reaction is the use of quantum density functional methods such as B3LYP [17] to determine the structure and energies of the reactants, products and transition state of a reaction pathway; these calculations provide predictions of the thermodynamics of the reaction and of the energetics of the barrier to reaction arising at the transition state. This data may then be used to assess the kinetics of the reaction. Recent examples of this approach have been used to replace or inform experiments using metal catalysts such molybdenum [18], rhodium [19] or ruthenium [20]. Such work lends mechanistic insight and other information which ultimately may reduce the number of experiments conducted in catalytic research; from a green perspective, this means some reduction in the use, and need for disposal of, catalysts, reagents, and organic solvents.

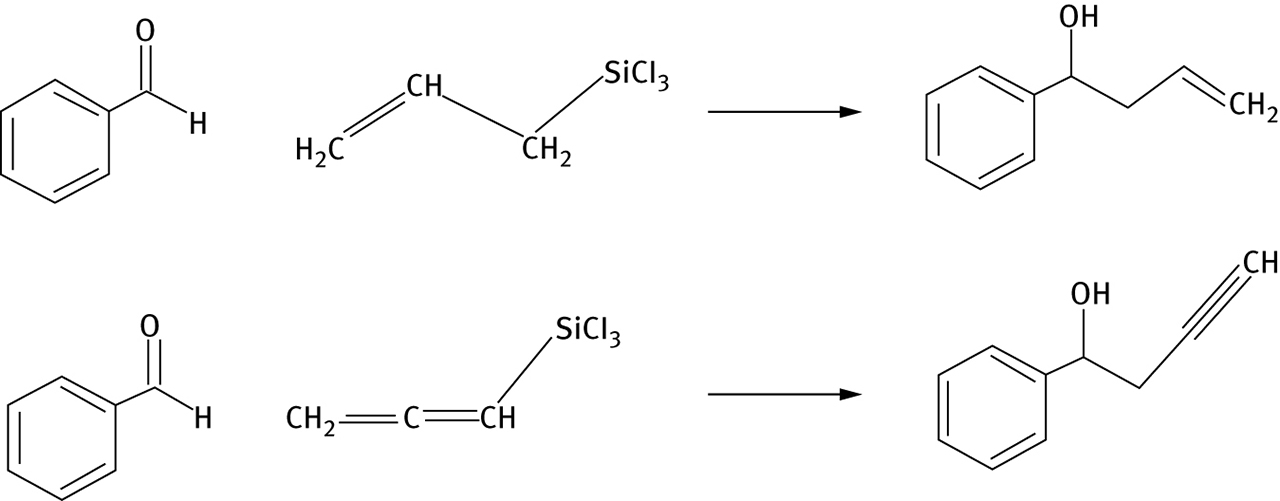

A potentially more significant opportunity for “greening” catalysis research, however, appears in a recent work by Wheeler et al. [21] Recent research in the field of organocatalysis seeks to use computational chemistry to develop methods to screen catalyst designs for stereoselectivity, hence eliminating the need to synthesize and test many catalysts which would ultimately fail to provided desired degrees of stereoselection [21, 22, 25]. The work discussed here [21] is motivated by a desire to understand the effect of non-covalent interactions on Lewis-Base alkylation reactions, focusing in particular upon the allylation or propargylation of benzaldehyde by means of allyl silanes, which produces substituted alcohols as shown in Figure 2.

Allylation (top) or propargylation (bottom) of benzaldehyde discussed in reference 19.

This reaction is known to be catalyzed by pyridine N-oxide and N,N′-dioxide catalysts, with varying degrees of enantioselectivity on the hydroxyl-substituted carbon. For several catalysts for these alkylation reactions, computational research was able to produce a predicted distribution of enantiomers which matched the experimentally observed product distribution. A challenging aspect of this work was that a particular catalyzed alkylation reaction might have 10 or even 20 relevant transition states connecting the reactant to the chiral products; these transition states are specific to formation of either R or S products, and predicting the distribution of enantiomeric products requires computations to determine all the structures and energies of all these transition states.

The task of predicting stereoselectivities for a large number of bipyridine N,N′-dioxide catalysts would then involve the computation of hundreds of transition states, a trying and time-consuming task. Sparks and Wheeler et al. were able to automate this work with the development of a computational tool kit referred to as AARON (Automated Alkylation Reaction Optimizer for N-oxides) [21, 26]. Testing of the AARON package revealed that in the case of allylations it was able to reproduce the experimentally known steroselectivities of a set of 18 bipyridine N,Nʹ dioxide catalysts [21, 27]. The package has since been used to predict the results of propargylations with 100 new bipyridine N,Nʹ dioxide catalysts. Some of these have a high degree of predicted enantioselectivity; the authors hope there will be experimental testing of some of their predictions. Meanwhile, Sparks and Wheeler are developing a new version of AARON [21, 28] capable of dealing with a broad variety of organocatalyzed organic reactions. The implications for “greening” here are apparent; a future in which literally hundreds of experiments, with attendant use of materials and generation of chemical wastes, might be able to be replaced by implementation of a quantum computational package.

4 Toward greener solvents

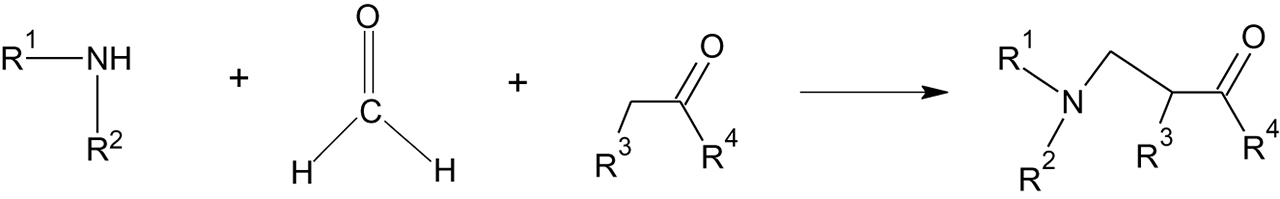

Specific applications of quantum computational methods to green chemistry appear regularly in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Green Chemistry. Much of this research is devoted to reducing usage of harmful or toxic solvents. An example of recent work [29] explores alternative solvents for the Mannich reaction [9, 29], the reaction of an amine, aldehyde, and enolizable ketone to produce a β-amino carbonyl compound, or Mannich base, as shown in Figure 3. This reaction plays an role in synthesis of bioactive species and pharmaceuticals [29, 30], but the synthesis is commonly run in organic solvents such as benzene, THF, acetone, and DMSO [29, 30].

The Mannich reaction.

Computational work [29] explores green catalysis of the Mannich reaction. Nornicotine, a natural product produced within tobacco plants, is a known catalyst for the aldol condensation in water [31], illustrating its ability to function as a catalyst in an aqueous medium. It is chosen for investigation as a green catalyst in aqueous solvent in this work. The computational work implements M062X hybrid density functional theory [32] and model solvents with the self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) in the form of the polarizable continuum model [33]. Investigation of the reaction potential energy surface finds that the energetic profile of intermediates and transition states along the reaction path with this catalyst are nearly identical in aqueous and DMSO or other organic solvent.

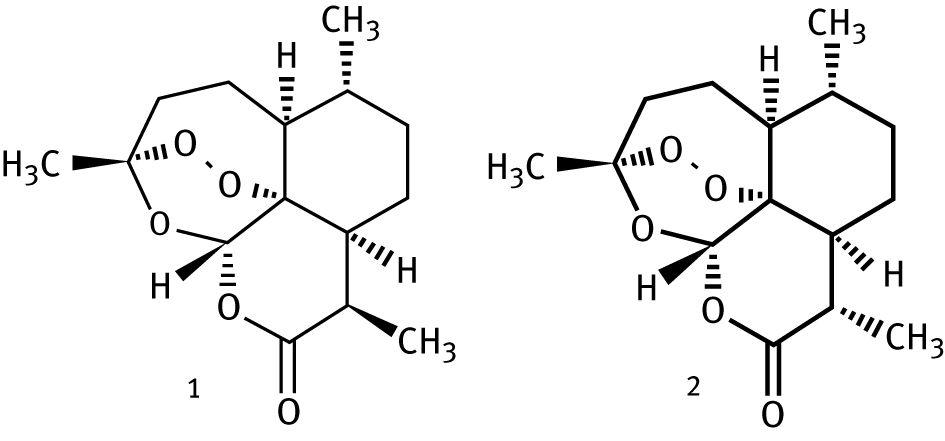

Another recent intensive use of quantum chemistry [34] has combined density functional calculations of the conformers of artemisinin (see Figure 4) with the COSMO_RS statistical mechanics method [35, 36] to a search for greener solvents for artemisinin extraction.

Structure of Artemisinin (1) and its diasteromer epiartemisinin (taken from reference 35).

Artemisinin is an antimalarial commonly extracted from the sweet wormwood plant [37] from which it is commonly extracted using hexane solvents [34, 38] or petroleum ether [34, 39], a mixture of hydrocarbons containing hexanes [40]. Newer approaches for extraction use fluorocarbons or the iodated fluorocarbon iodotrifluoromethane [34], compounds which have significant global warming potential [34, 41] as well as some environmental toxicity [34, 42].

The combined quantum mechanical/statistical mechanical modeling was employed to calculate the solubility of artemisinin, as well as its diastereomer, epiartemisinin, in a wide range of solvents. The predicted values for water and a number of common organic solvents were compared to available experimental values, finding generally good agreement in most cases, such as water, alcohols, and chloroform. Further calculations obtained predicted solubilities in a large number of “novel” solvents, for which little experimental data is available. Diacetone alcohol, DMPU (1,3-Dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone), DMI (1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone) and organic carbonates are predicted to be effective solvents with low toxicity. DMPU, glyceryl carbonate, ethyl lactate, and glycerol isobutyral in particular were identified as solvents that could be obtained from renewable feedstocks.

5 Polymer production from CO2 emissions

As the quantity of atmospheric carbon dioxide increases, there is an increase in concern for the implications for global warming and climate change. As a result, recent quantum-computational investigations have been concerned with remediation of increasing concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide. While some computational studies deal with capture and storage of carbon dioxide [43], other investigations deal with the green approach of finding uses for CO2 as a feedstock for syntheses of chemical products, a feedstock conceivably renewed by ongoing use of the otherwise polluting emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels. One example of such work may be found in a recent Green Chemistry publication involving the carboxylation of organoboron compounds by means of catalysis with rhodium complexes; density functional theory is used to compare the relative efficacies of catalysis when diboron and diphosphane ligands are used within the rhodium complex [44].

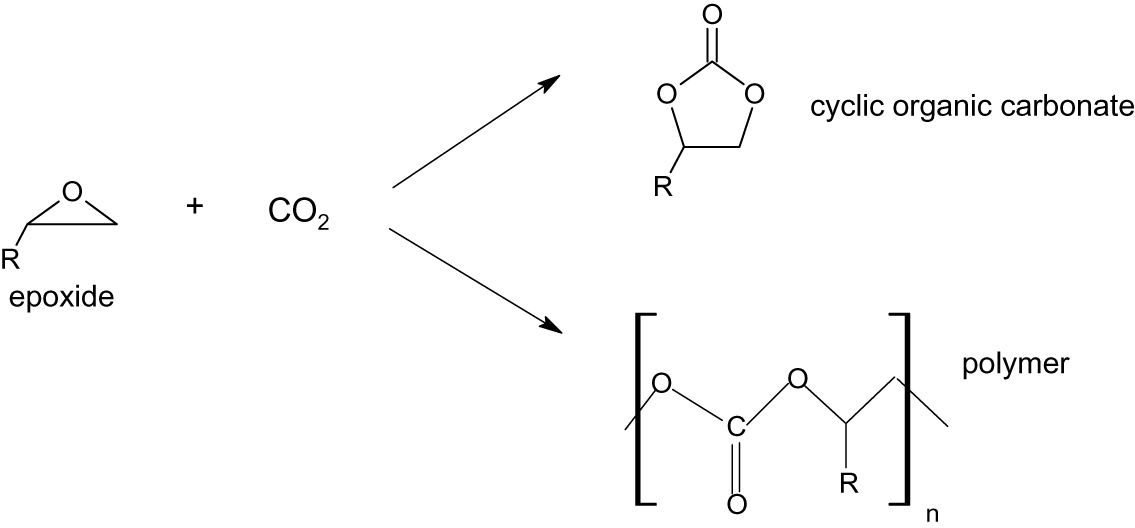

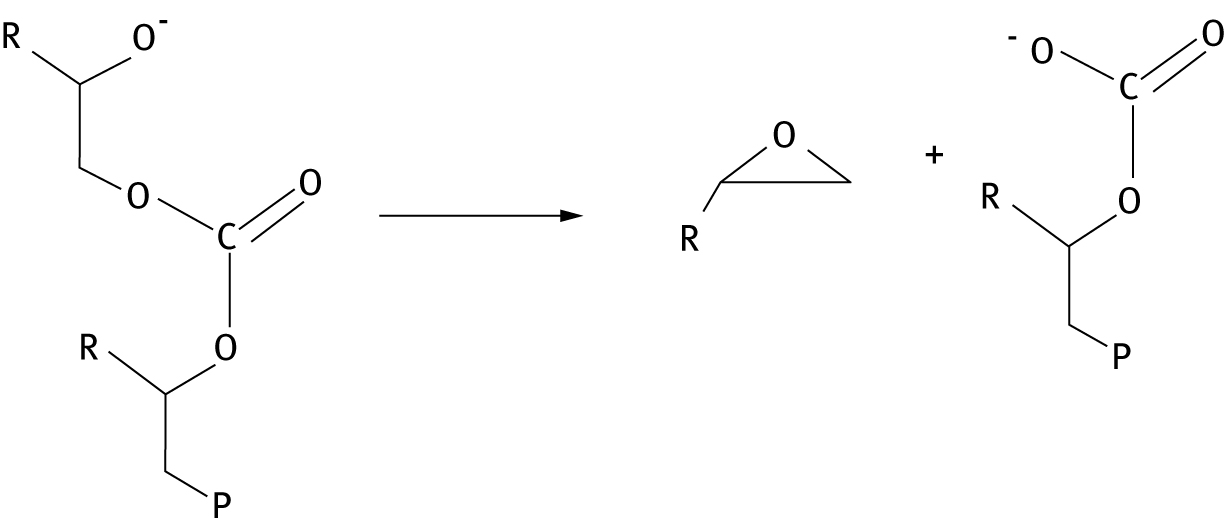

An intriguing line of research in CO2 utilization has focused on the reaction of carbon dioxide with epoxides to produce commercially useful polymers or cyclic organic carbonates; which, as we have seen, have uses as green solvents. The reactions are illustrated in Figure 5.

Reactions of CO2 with epoxides.

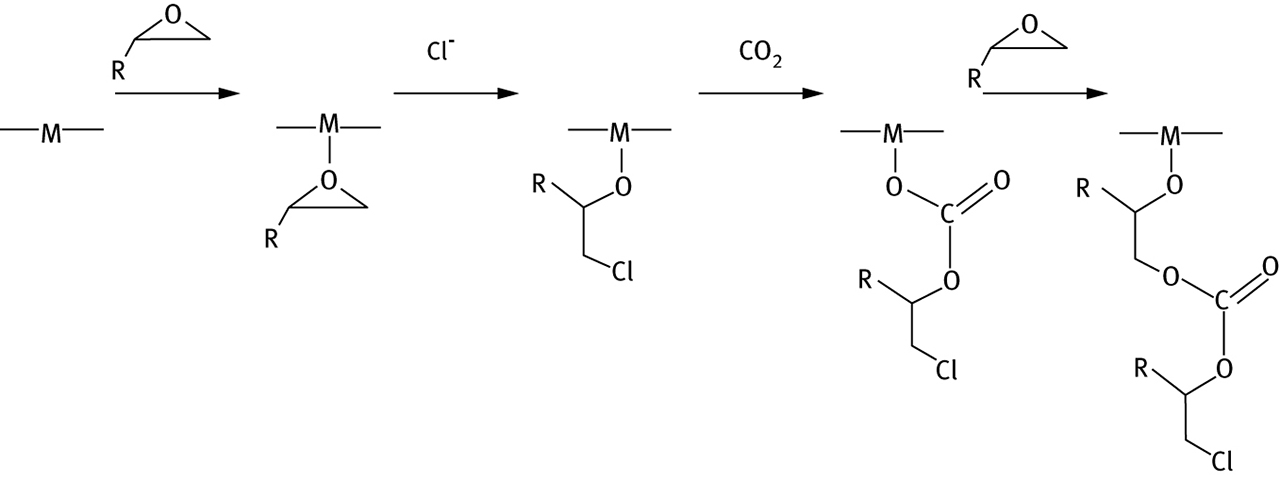

The polymer formation reaction has long been known to be catalyzed by complexes of zinc ions [45], but relatively more recent experimental work [45] has focused on the mechanism of the reaction when catalyzed by complexes of Cr3+, Co3+, or Al3+, with bis(salicylaldimine) ligands; the reaction begins with complexation of the epoxide to the metal, followed by ring opening with an anion initiator such as Cl– or N3–; this is followed by insertion of CO2 and then alternating epoxide and CO2 insertion as shown in Figure 6.

Catalyzed copolymerization of CO2 and epoxide. Cl- is shown as the initiator.

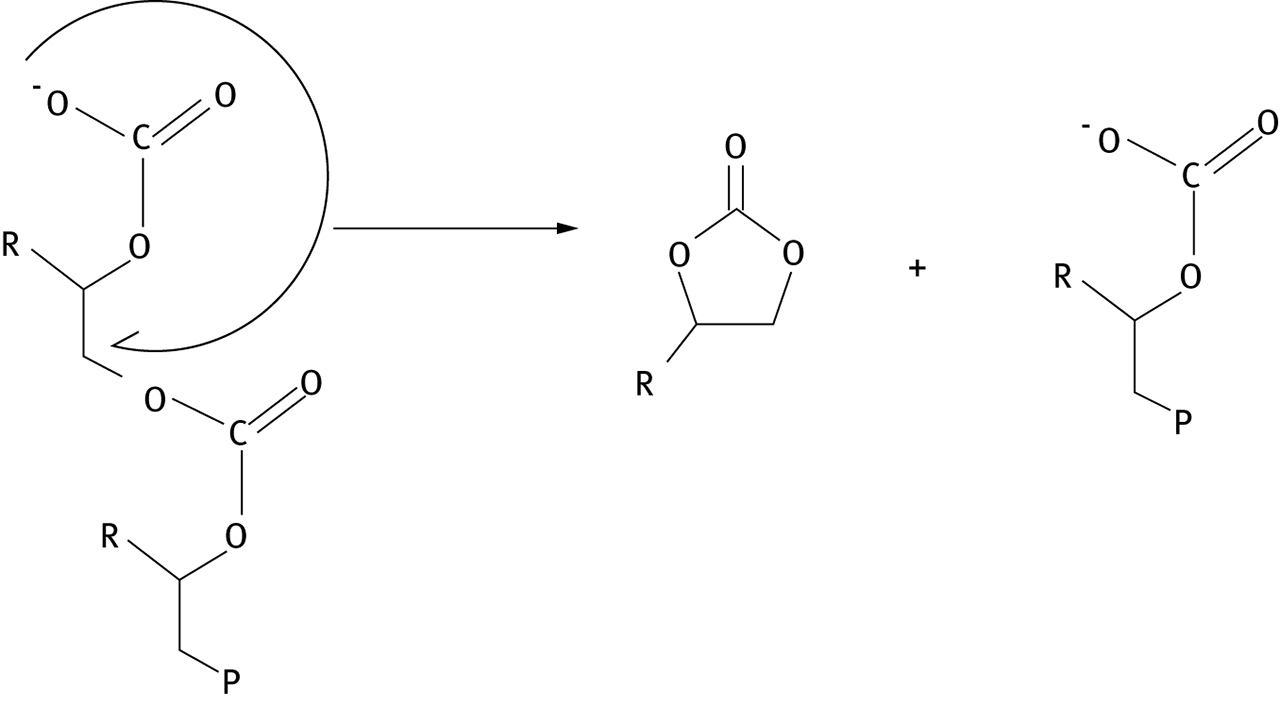

Research in computational chemistry has provided a significant amount of information about this process. Experimental data on the thermodynamics of epoxide formation are sparse, but a quantum computational study has been made of the thermodynamics of CO2-epoxide copolymerization, and of the competing process, carbonate formation, for a number of candidate epoxides [46]. In general, the formation of the polymer is found to be the more exothermic of the two reactions, but calculations of free energy changes for polymerization and carbonate formation indicate the formation of cyclic carbonates is generally more thermodynamically favored, due to entropy considerations; the authors note that this makes the formation of carbonate byproduct temperature sensitive. Consideration of computational work [46] with experimental data on metal-catalyzed reactions [47, 48] suggests that the competing carbonate formation most likely proceeds from a carbonate back biting reaction which proceeds most rapidly in a “metal-free” fashion as opposed to via a metal complex, as shown in Figure 7. The reaction is found to be in general exergonic for a number of epoxide substrates.

Carbonate back-biting reaction. “P” indicates polymer chain.

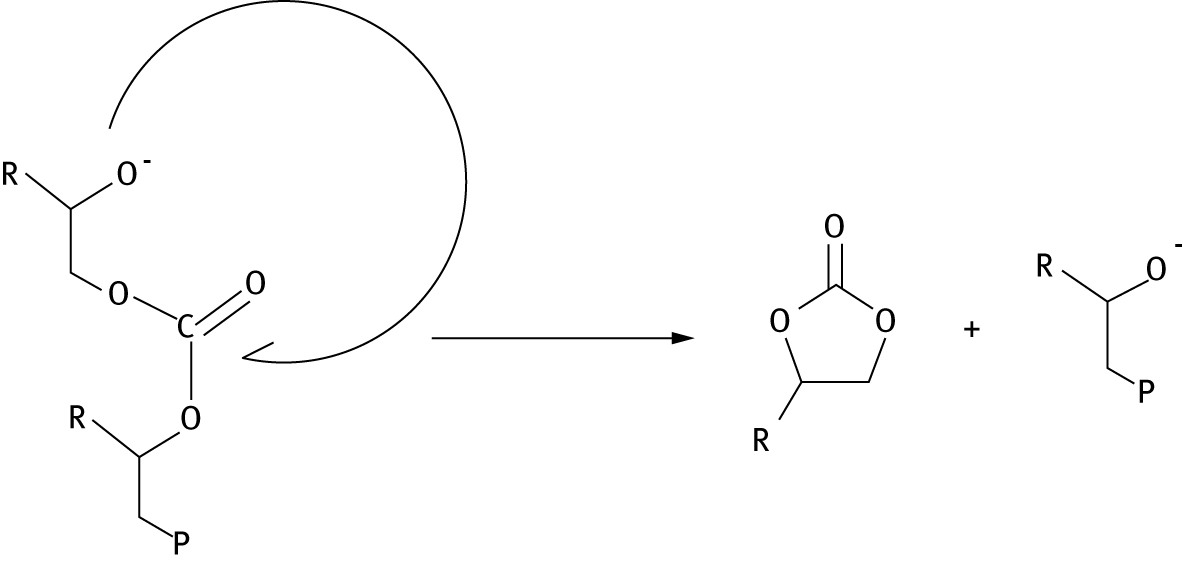

While carbonate back-biting is expected to be a degradation mechanism in ambient conditions, with CO2 available, alkoxide back-biting reactions may cause depolymerization in more basic conditions [46, 49], these alkoxide reactions may cause cyclic carbonate formation (Figure 8) or complete decomposition to epoxides (Figure 9). In general, for a number of copolymers, calculations determine that barriers to the formation of epoxide are higher than those for the formation of cyclic carbonate.

Alkoxide “back-biting” reaction producing a cyclic organic carbonate. “P” represents polymer chain.

Alkoxide back-biting reaction producing an epoxide. “P’ represents polymer chain.

Quantum computations determine that epoxide forming reactions are thermodynamically favorable; however, cyclic carbonate is in general the only product because epoxide formation has a higher barrier for reaction. In addition, the epoxide-forming reaction gives rise to carbonate polymers that undergo carbonate back-biting.

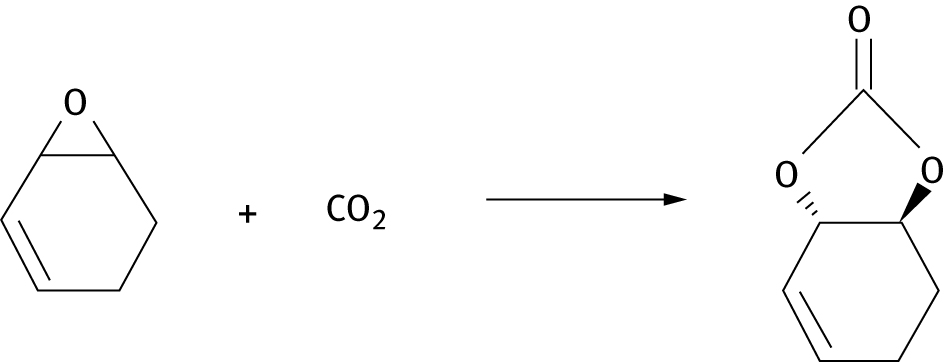

Similar calculations [50] in conjunction with experiments have examined the impact of different epoxide substrates, in particular 1,4 and 1,3-cyclohexadiene oxides, or 1,2-epoxy-4-cyclohexene and 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene. Computations compared 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene, 1,2-epoxy-4-cyclohexene and cyclohexene oxide (1,2 epoxy cyclohexane) . Experiments show that 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene is the more reactive species than 1,2-epoxy-4-cyclohexene for formation of products, computation explains that this is the result of lower barriers to the epoxide ring-opening step involved in both polymerization and carbonate formation.

Experiments indicate that the reaction of 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene produces copolymer and cis-cyclic carbonate, but no trans cyclic carbonate is formed (see Figure 10) The calculations show that 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene is unusual in that polymer formation is thermodynamically more favorable than trans-cyclic carbonate formation; in particular trans carbonate formation is endergonic in the case of 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene substrate.

Hypothetical reaction of 1,2-epoxy-3-cyclohexene to produce a trans cyclic carbonate. This product is not observed experimentally, the corresponding cis product is.

6 Conclusion

Quantum computational chemistry has been shown to be an important contributor to green chemistry in several promising and exciting ongoing developments. In synthetic chemistry, the ability to study reactions and catalysis “in silico” increasingly offers a means of replacing some experimental laboratory research. Quantum computation has also been shown to offer information on choosing greener solvents. Computation plays a key role in advancing prospects for the design of enzyme catalysts; these catalysts offer the hope of replacing toxic catalysts and organic solvents with non-toxic organic catalysts and aqueous solvents. Molecular orbital quantum calculations play an ongoing role in green methods for the remediation and recycling of carbon dioxide.

As stated previously, this chapter does not attempt to discuss all applications of quantum calculations to making chemistry “greener”. The journal Green Chemistry regularly provides accounts of such efforts, and the importance of green chemistry assures that other examples will continue to appear in other prominent journals.

Acknowledgment

This article is also available in: Benvenuto, Green Chemical Processes. De Gruyter (2017), isbn 978–3–11–044487–2.

References

1. Born M, Oppenheimer RJ. “Zur Quantentheorie der Molekeln” [On the quantum theory of molecules]. Ann Der Phys. 1927;389:457–522.10.1002/andp.19273892002Search in Google Scholar

2. Hehre WJ, Lathan WA, Ditchfield R, Newton MD, Pople JA. Gaussian 70. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.. Quantum Chemistry Program Exchange, Program No. 237 1970 .Search in Google Scholar

3. Hehre WJ. A Guide to Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Calculations. Irvine, CA: Wavefunction, Inc., 2003. Available at: https://www.wavefun.com/support/AGuidetoMM.pdf. Accessed: 15 Dec 2016.Search in Google Scholar

4. Skyner RE, McDonagh JL, Groom CR, Van Mourik T, Mitchell JB. A review of methods for the calculation of solution free energies and the modelling of systems in solution. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:6174–6191.10.1039/C5CP00288ESearch in Google Scholar

5. Warner Babcock Institute for Green Chemistry. The 12 principles. Available at: http://www.warnerbabcock.com/green-chemistry/the-12-principles/. Accessed: 15 Dec 2016.Search in Google Scholar

6. Siegel JB, Zanghellini A, Lovick HM, Kiss G, Lambert AR, St. Clair JL, et al. Computational design of an enzyme catalyst for a stereoselective bimolecular Diels-Alder reaction. Science. 2010;329:309–319.10.1126/science.1190239Search in Google Scholar

7. Tantillo D. Computational catalysis for organic synthesis. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:6 .Search in Google Scholar

8. Ahrendt KA, Borths CJ, MacMillan DW. New strategies for organic catalysis: the first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels-Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122 4243−4244.10.1021/ja000092sSearch in Google Scholar

9. Stretiweiser A, Heatchcock CH. Introduction to organic chemistry, 3rd ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1985.Search in Google Scholar

10. Boron trifluoride, Center for Disease Control, The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/7637072.html. Accessed: 15 Dec 2016.Search in Google Scholar

11. Tin Tetrachloride. National Institute of Health Pubchem., 2016 Dec 15 Accessed:15Dec2016. Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/7637072.html.Search in Google Scholar

12. Zanghellini A, Jaing L, Wollacot AM, Gong C, Meiler J, Althoff EA, et al. New algorithms and an in silico benchmark for computational enzyme design. Protein Sci. 2006;12(15):2785–2794 .10.1110/ps.062353106Search in Google Scholar

13. Tantillo DJ, Houk KN. Theozymes and compuzymes: theoretical models for biological catalysis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1998;2:743–750.10.1016/S1367-5931(98)80112-9Search in Google Scholar

14. Kries H, Blober R, Hilvert D. De novo enzymes by computational design. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:1–8.10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.02.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. DeGrado WF, Wasserman ZR, Lear JD. Protein design, a minimalist approach. Science. 1989;243:622–628.10.1126/science.2464850Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Raymond EA,, Mck KL, Yoon JH, Moroz OV, Moroz YS, Korendoych IV. Design of an allosterically regulated retroaldolase. Protein Sci. 2015;24:561–570.10.1002/pro.2622Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98 5648−5652.10.1063/1.464913Search in Google Scholar

18. Tanaka H, Nishibayashi Y, Yoshizawa K. Interplay between theory and experiment for ammonia synthesis catalyzed by transition metal complexes. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49(5):987–995.10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Park Y, Ahn S, Kang D, Baik M-H. Mechanism of Rh-catalyzed oxidative cyclizations: closed versus open shell pathways. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49(6):1263–127.10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00111Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Zhang X, Chung L-W, Wu Y-D. New mechanistic insights on the selectivity of transition-metal-catalyzed organic reactions: the role of computational chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49(6):1302–1310.10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00093Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Wheeler SE, Seguin TJ, Guan Y, Doney AC. Noncovalent interactions in organocatalysis and the prospect of computational catalyst design. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49 1061−1069.10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00096Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Chen J, Captain B, Takenaka N. Helical chiral 2,2′-bipyridine N-monoxides as catalysts in the enantioselective propargylation of aldehydes with allenyltrichlorosilane. Org Lett. 2011;13 1654−1657.10.1021/ol200102cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Lu T, Zhu R, An Y, Wheeler SE. Origin of enantioselectivity in the propargylation of aromatic aldehydes catalyzed by helical N-oxides. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134 3095−3102.10.1021/ja209241nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Lu T, Porterfield MA, Wheeler SE. Explaining the disparate stereoselectivities of n-oxide catalyzed allylation and propargylation of aromatic aldehydes. Org. Lett.. 2012;14 5310−5313.10.1021/ol302493dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Sepúlveda D, Lu T, Wheeler SE. Performance of DFT methods and origin of stereoselectivity in bipyridine n,n′-dioxide catalyzed allylation and propargylation reactions. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12 8346−8353.10.1039/C4OB01719FSearch in Google Scholar

26. Rooks BJ, Wheeler SE. AARON, automated alkylation reaction optimizer for N-oxides, version 0.72. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

27. Rooks BJ, Haas MR, Sepúlveda D, Lu T, Wheeler SE. Prospects for the computational design of bipyridine N,N′-dioxide catalysts for asymmetric propargylations. ACS Catal. 2015;5 272− 280.10.1021/cs5012553Search in Google Scholar

28. Guan Y, Rooks BJ, Wheeler SE. AARON: an automated reaction optimizer for non-metal catalyzed reactions, version 0.91. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

29. Yang S-C, Lankau T, Yu C-H. A theoretical study of the nornicotine-catalyzed Mannich reaction in wet solvents and water. Green Chem. 2014;16:3999–4008.10.1039/C4GC01021CSearch in Google Scholar

30. Pyne SG, Au CW, Davis AS, Morgan IR, Ritthiwigrom T, Yazici A. Exploiting the borono-Mannich reaction in bioactive alkaloid synthesis. Pure Appl Chem. 2008;80(4):751–762.10.1351/pac200880040751Search in Google Scholar

31. Dickerson TJ, Janda KM. Aqueous aldol catalysis by a nicotine metabolite. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3220–3221.10.1021/ja017774fSearch in Google Scholar

32. Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194101.10.1063/1.2370993Search in Google Scholar

33. Miertuš S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J. Electrostatic Interaction of a Solute with a Continuum. A Direct Utilizaion of AB Initio Molecular Potentials for the Prevision of Solvent Effects. Chem Phys. 1981;55:117–129.10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2Search in Google Scholar

34. Lapkin AA, Peters M,, Greiner L, Chemat S, Leonhard K, Liauw MA, et al. Screening of new solvents for artemisinin extraction process using ab initio methodology. Green Chem. 2010;12:241–251.10.1039/B922001ASearch in Google Scholar

35. Klamt A, Eckert F, Hornig M, Beck ME, B¨Urger T. Fast solvent screening via quantum chemistry: COSMO-RS approach. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:275–281.10.1002/jcc.1168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Lei Z, Chen B, Li C. COSMO-RS modeling on the extraction of stimulant drugs from urine sample by the double actions of supercritical carbon doxide and ionic liquid. Chem Eng Sci. 2007;62:3940–3950.10.1016/j.ces.2007.04.021Search in Google Scholar

37. Lite J. Scientific American. Accessed: 15 Dec 2016. 2008. What is Artemisinin?23 DecAvailable at:http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/artemisinin-coartem-malaria-novartis/.Search in Google Scholar

38. ELSohly HN, Croom EM, El-Faraly FS, El Sherei MM. A large-scale extraction technique of artemisinin from artemisia annua. J Nat Prod. 1990;53(6):1560–1564.10.1021/np50072a026Search in Google Scholar

39. Lapkin A, Plucinski PK, Cutler M. Comparative assessment of technologies for extraction of artemisinin. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1653–1664.10.1021/np060375jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Center for Disease Control. 2016 Dec 15 Accessed:15Dec2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pdfs/77-192c.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

41. Stevens JE, Macomber LD, Davis LW. IR spectra and vibrational modes of the hydrofluoroethers CF3OCH3, CF3OCF2H, and CF3OCF2CF2H and corresponding alkanes CF3CH3, CF3CF2H, and CF3CF2CF2H. Open Phys Chem J. 2010;4:17–27.10.2174/1874067701004010017Search in Google Scholar

42. Stevens JE, Jabo Khayat RA, Radkevich O, Brown J. * CF3CFHO vs. CH3CH2O: an ab initio molecular orbital study of mechanisms of decomposition and reaction with O2. J Phys Chem. 2004;108:11354–11361.10.1021/jp0468509Search in Google Scholar

43. Morris W, Leung B, Hiroyasu F, Yaghi OK, Ning H, Hayashi H, et al. A combined experimental-computational investigation of carbon dioxide capture in a series of isoreticular zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11006–11008.10.1021/ja104035jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Qin H-L, Han J-B, Hao J-H, Kansten EA. Computational and experimental comparison of diphosphane and diene ligands in the Rh-catalysed carboxylation of organoboron compounds with CO2. Green Chem. 2014;16:3224–3229.10.1039/c4gc00243aSearch in Google Scholar

45. Darensbourg J, Mackiewicz RM, Phelps AL, Billodeaux DR. Copolymerization of CO2 and epoxides catalyzed by metal salen complexes. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:836.10.1021/ar030240uSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Darensbourg DJ, Yeung AD. Thermodynamics of the carbon dioxide−epoxide copolymerization and kinetics of the metal-free degradation: a computational study. Macromolecules. 2013;46 83−95.10.1021/ma3021823Search in Google Scholar

47. Darensbourg DJ, Bottarelli P, Andreatta JR. Inquiry into the formation of cyclic carbonates during the (Salen)CrX Catalyzed CO2/cyclohexene oxide copolymerization process in the presence of ionic initiator. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7727.10.1021/ma071206oSearch in Google Scholar

48. Darensbourg DJ, Yarbrough JC, Ortiz C, Fang CC. Comparative kinetic studies of the copolymerization of cyclohexene oxide and propylene oxide with carbon dioxide in the presence of chromium salen derivatives. in situ ftir measurements of copolymer vs cyclic carbonate production. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7586.10.1021/ja034863eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Darensbourg DJ, Yeung AD, Wei S-H. Base initiated depolymerization of polycarbonates to epoxide and carbon dioxide co-monomers: a computational study. Green Chem.. 2013;15:1578.10.1039/c3gc40475gSearch in Google Scholar

50. Darensbourg DJ, Chung W-C, Yeung AD, Luna M. Dramatic behavioral differences of the copolymerization reactions of 1,4-cyclohexadiene and 1,3-cyclohexadiene oxides with carbon dioxide. Macromolecules. 2015;48 1679−1687.10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00172Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Applications of silver nanoparticles stabilized and/or immobilized by polymer matrixes

- Addressing the challenges of standalone multi-core simulations in molecular dynamics

- Virtually going green: The role of quantum computational chemistry in reducing pollution and toxicity in chemistry

- BioArtificial polymers

- Green analytical chemistry – the use of surfactants as a replacement of organic solvents in spectroscopy

- Membrane contactors for CO2 capture processes – critical review

- Elemental Two-Dimensional Materials Beyond Graphene

Articles in the same Issue

- Applications of silver nanoparticles stabilized and/or immobilized by polymer matrixes

- Addressing the challenges of standalone multi-core simulations in molecular dynamics

- Virtually going green: The role of quantum computational chemistry in reducing pollution and toxicity in chemistry

- BioArtificial polymers

- Green analytical chemistry – the use of surfactants as a replacement of organic solvents in spectroscopy

- Membrane contactors for CO2 capture processes – critical review

- Elemental Two-Dimensional Materials Beyond Graphene