Cavitation-induced damage on a ship propeller’s Kort nozzle made of AISI 316L and investigation of the near-surface microstructural changes

-

R. Haubner

, P. Linhardt

Paul Linhardt is Ao. Univ. Prof. at TU-Wien. He is specialized on corrosion of metallic materials with emphasis on electrochemical mechanisms and a particular field of interest is microbially influenced corrosion. A major part of his work is related to failure analysis and material testing.Maria Victoria Biezma is full professor of Materials Science and Engineering of University of Cantabria, Spain. She is currently involved in the study of the relationship between chemical composition, microstructure, and corrosion behavior of different metallic systems, mainly copper based alloys and superduplex stainless steels, as well as failure analysis of materials.

Abstract

A piece of a Kort nozzle, a ring-shaped component enclosing a ship’s propeller severely damaged by cavitation was examined. The nozzle was made of stainless steel grade AISI 316L.

The piece of steel examined exhibits a damage gradient which can be explained by cavitation of regionally varying severity. Areas severely stressed by cavitation are characterized by an increased material removal and high surface roughness.

Since cavitation-induced material removal can be attributed to a mechanical damage to the surface, the aim was to investigate the microstructural changes in the steel. Samples were taken along the gradient and cross-sections were prepared.

The etched metallographic section revealed clear evidence of deformation. Toward the lower load, a decreasing amount of deformation twins can be observed along the cavitation gradient and also from the surface toward the base material. It can also be assumed that severe deformation leads to the formation of deformation martensite. Against the background of a significant increase in magnetizability from the unaffected material toward the damage zone identified through qualitative analysis, magnetic measurements were performed and confirmed a higher magnetizability in the damaged near-surface areas.

The steel’s base metal has a uniform, austenitic microstructure.

Kurzfassung

Ein durch Kavitation stark geschädigtes Stück einer Kortdüse, einem ringförmigen Bauteil, das einen Schiffspropeller umschließt, wurde untersucht. Es handelt sich dabei um rostfreien Stahl der Qualität AISI 316L.

An dem untersuchten Stahlstück ist ein Schädigungsgradient zu sehen, der auf regional unterschiedlich starke Kavitation zurückzuführen ist. Bereiche mit starker Kavitationsbelastung zeigen erhöhten Materialabtrag und hohe Oberflächenrauigkeit.

Da Materialabtrag durch Kavitation auf mechanische Schädigung der Oberfläche zurückzuführen ist, sollten die Gefügeveränderungen im Stahl untersucht werden. Es wurden Proben entlang des Gradienten entnommen und Querschliffpräparationen angefertigt.

Am geätzten, metallographischen Schliff sind die Verformungsspuren deutlich zu erkennen. Eine Abnahme an Verformungszwillingen ist entlang des Kavitationsgradienten, in Richtung geringer Belastung, und auch von der Oberfläche Richtung Grundwerkstoff festzustellen. Es ist auch anzunehmen, dass bei starker Verformung Umformmartensit gebildet wird. Da bereits qualitativ ein deutlicher Anstieg der Magnetisierbarkeit vom unbeeinflussten Werkstoff in Richtung der Schädigungszone festzustellen war, wurden magnetische Messungen durchgeführt, die eine höhere Magnetisierbarkeit der geschädigten oberflächennahen Bereiche bestätigten.

Das Grundmetall des Stahls zeigt ein gleichmäßiges, austenitisches Gefüge.

1 Introduction

The formation and subsequent collapse of vapor bubbles in liquids is referred to as cavitation [1]. Vapor bubbles form when the static pressure of a liquid falls below its vapor pressure. This phenomenon can appear in fast-flowing liquids. However, it can also be ultrasound-induced. If the pressure rises rapidly, the damaging effect occurs in which vapor bubbles implode near surfaces. A micro-jet is thus formed, hitting the material at high speed and exerting mechanical stress on it [1].

Aimed at preventing the formation of vapor bubbles, studies on cavitation in components typically focus on fluid dynamics rather than on the material damage caused. Literature on the interactions between cavitation and materials is thus scarce [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

AISI 316L steel (equivalent to material no. 1.4404) is widely used. According to its specifications, it should be purely austenitic. However, if due to solidification δ ferrite remains in the microstructure, austenitic steels may also contain a ferritic fraction. Owing to a steel deformation the δ ferrite then appears as an elongated microstructural constituent [8]. δ ferrite, as a type of ferrite, is magnetic and thus increases the magnetizability of the austenitic steel [9].

Another phase that may be formed in austenite is the so-called deformation martensite. It is formed at high degrees of deformation subsequent to the formation of deformation twins. These twins thus constitute the precursor to the formation of martensite [10]. Owing to its crystal structure, martensite is also magnetic. Furthermore, martensite in austenite alters the corrosion resistance of an austenitic steel and may thus lead to preferential corrosion in the martensitic microstructural constituents [11, 12, 13].

Experiments were performed aimed at documenting the deformation gradient and the associated martensite formation in this steel severely damaged by cavitation (Figure 1).

View of the damaged area on the Kort nozzle. a) Front, b) back (© Paula Solla Besada).

Bild 1a und b: Ansicht der schadhaften Stelle an der Kortdüse. a) Vorderseite, b) Rückseite. (© Paula Solla Besada).

2 Examination methods

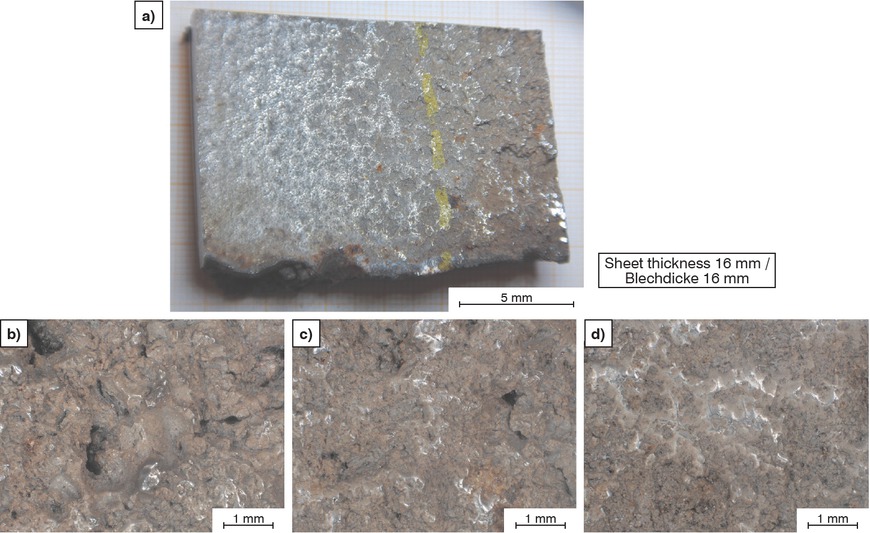

Two slices were cut from the sample (Figure 2a) using a cutting machine. One slice was cut into three approximately equal-sized pieces for metallographic examinations. The second slice was, once again, cut into pieces of approximately 0.3 g for magnetic measurements.

Examined piece of steel. a) Overall view, b) severely damaged, c) moderately damaged, d) slightly damaged, b–d) 3D digital microscopy images.

Bild 2a bis d: Untersuchtes Stahlstück. a) Gesamtansicht, b) stark geschädigt, c) mittelmäßig geschädigt, d) wenig geschädigt, b–d) 3D-Digitalmikroskopiebilder.

Metallography: the samples were embedded in epoxy resin. Subsequent to plane grinding (P220), polishing steps were performed using 9 to 1 μm diamond suspensions. Lichtenegger-Blöch etchant was used to reveal the microstructure [14]. The prepared sections were examined using a light microscope (LOM) and a backscattered electron detector (BSE) in a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Magnetic measurements: a Foerster “Foerster-Koerzimat 1.096” was used to determine the magnetic saturation moment [15]. Samples with an approx. weight of 0.3 g were used to calculate the magnetizability, since this can indicate the ferrite content in the samples by comparing it to standard ferrite.However, due to the relatively low weight of the samples and the small magnetic fraction, the results obtained are only semiquantitative.

3 Results and discussion

Cavitation deformed the steel surface and eroded it until perforation (Figure 1a). In areas substantially affected by cavitation, deep holes and a severely roughened surface are recognizable (Figure 2b). These effects disappear with increasing distance from the point of perforation (Figures 2c and d).

3.1 Surface severely deformed by cavitation

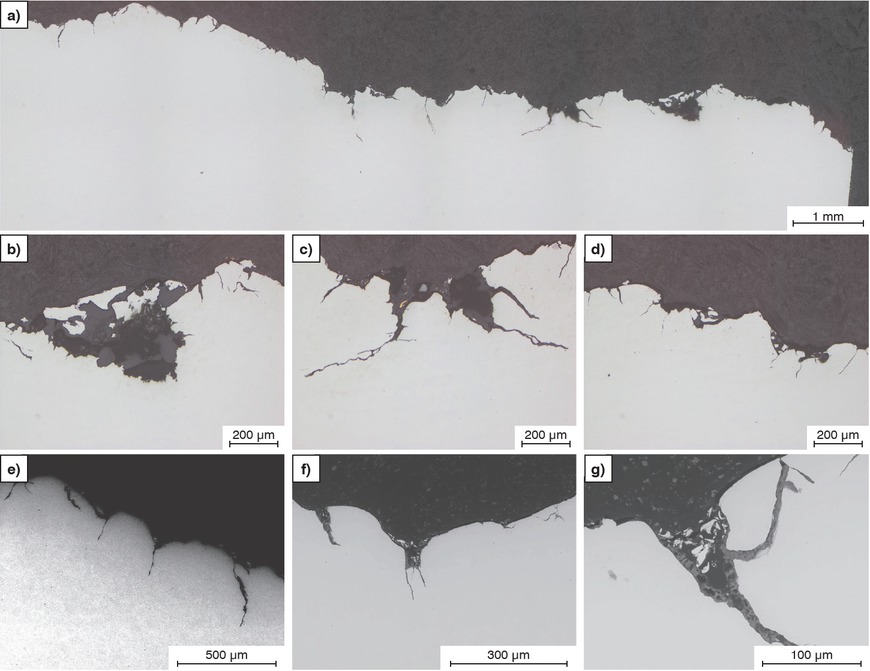

The polished cross-section of the sample reveals the heavily furrowed surface of the steel (Figure 3a) as well as holes and cracks (Figures 3b–g). The holes are up to 500 μm deep and also contain corrosion products (Figures 3b, c, g). The cavitation-induced opening of the fresh, non-passive metal surface likely caused the formation of the corrosion products. Cracks can be observed initiating from the holes, but also from the surface extending up to 1 mm into the steel (Figures 3a, c, e).

Polished cross-section. a) Overview image, b–g) differently deformed surfaces with cracks. a–d) LOM, e–g) SEM.

Bild 3a bis g: Querschnitt poliert. a) Übersichtsaufnahme, b–g) unterschiedlich deformierte Oberflächen mit Rissen. a–d) LOM, e–g) REM.

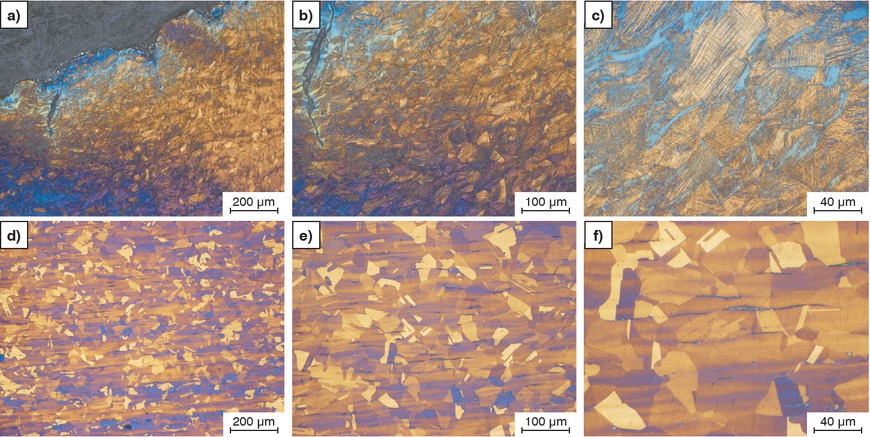

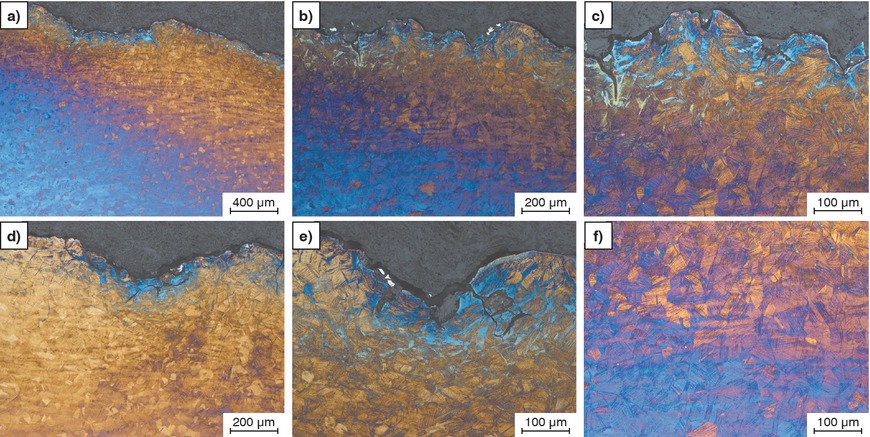

Subsequent to etching, deformed areas can be identified by the high density of deformation twins (Figures 4a–c). The highest density of deformation twins is recorded near the surface (Figure 4c), where, bluish areas can also be observed; which could represent the deformation martensite. The Lichtenegger-Blöch etchant does not color ferrite. However, it colors the martensite which appears light blue. The proximity to the heavily deformed surface and to cracks extending up to 500 μm into the steel is further evidence that the material is martensite (Figures 5a–c).

a–c) Severely deformed near-surface area, d–f) undamaged microstructure in the center of the sample. Etching according to Lichtenegger-Blöch, LOM.

Bild 4a bis f: a–c) Stark verformter, oberfächennaher Bereich, d–f) ungeschädigtes Gefüge in der Probenmitte. Ätzung Lichtenegger Blöch, LOM.

a–c) Severely deformed near-surface area, Lichtenegger-Blöch, LOM.

Bild 5a bis c: a – c) Stark verformter oberfächennaher Bereich, Lichtenegger Blöch, LOM.

The severely deformed area extends up to 1 mm below the surface (Figure 4a). The deformation then gradually decreases towards the undamaged initial microstructure of the steel (Figures 4d–f). The austenitic steel has a grain size of up to 50 μm. It is furthermore characterized by a rolled microstructure featuring typical segregation bands. Small amounts of δ ferrite are also present (Figure 4f).

3.2 Moderately stressed surface

In areas subjected to moderate cavitation stress, the severely deformed zone characterized by strong twinning and martensite formation is considerably narrower (approx. 500 μm) (Figures 6a and b). Cracks can also be observed. However, they are only about 100 μm long. Martensite is presumably present in the near-surface areas. Compared to the severely deformed microstructure, it is less abundant (Figures 6c–e). The deformed area is followed by the transition to the unaltered austenitic microstructure (Figure 6f).

a–e) Moderately deformed near-surface region, f) slightly deformed transition region. Etching according to Lichtenegger-Blöch, LOM.

Bild 6a bis f: a–e) Mittelstark verformter oberfächennaher Bereich, f) wenig verformter Übergangsbereich. Ätzung Lichtenegger Blöch, LOM.

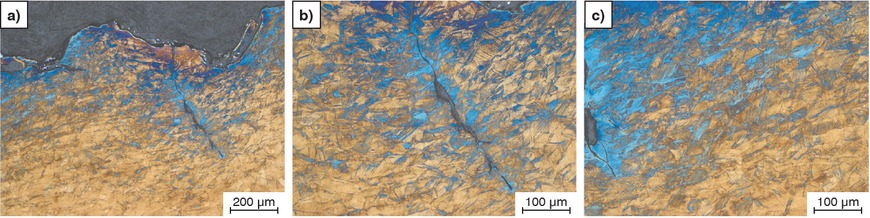

Figure 7 shows a transition to a less stressed area. The layer of deformation martensite is approximately 300 μm thick here (Figure 7a). The number of deformation twins in the austenite grains is rather small. However, the martensite remarkably has the same orientation as the deformation twins (Figures 7b and c). This suggests that martensite is formed from the deformation twins.

a–c) Moderately deformed near-surface area. Etching according to Lichtenegger-Blöch, LOM.

Bild 7a bis c: a–c) Mittelstark verformter oberfächennaher Bereich. Ätzung Lichtenegger Blöch, LOM.

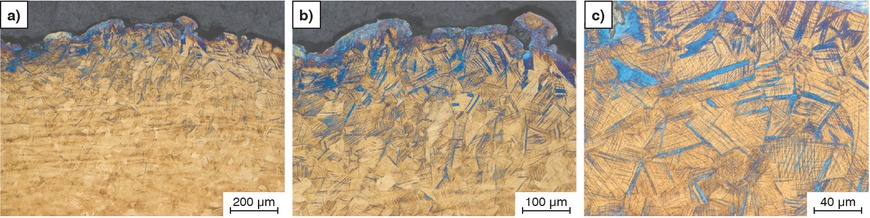

3.3 Slightly stressed surface

In this area, no holes or cracks are visible on the surface (Figure 8a). Isolated deformation twins are visible down to a depth of approximately 400 μm (Figures 8b and c). However, martensite is barely observed.

a–c) Slightly deformed near-surface area. Etching according to Lichtenegger-Blöch, LOM.

Bild 8a bis c: a–c) Schwach verformter oberfächennaher Bereich. Ätzung Lichtenegger Blöch, LOM.

3.4 Magnetic measurements

In the severely deformed section of the sample, approximately 3 wt. % ferrite was measured. Near the surface, in areas less impacted by cavitation, the values drop to 1.5 wt. %. In the austenitic base material, approximately 0.2 wt. % ferrite was recorded, which can be explained by the presence of δ ferrite.

Although only semi-quantitative, the measurements have shown that cavitation causes the partial transformation of non-magnetic austenitic steel into magnetic martensite.

4 Conclusions

A steel grade AISI 316L severely damaged by cavitation was examined. Samples were taken along the cavitation gradient and metallographically prepared.

Areas subjected to severe cavitation stress exhibit holes of a depth of up to 500 μm as well as cracks. They can be attributed to an increased material removal. A large number of deformation twins is visible in the austenitic grains, and martensite is also present near the surface.

Along the gradient, both the amount of deformation twins and deformation martensite decrease.

Magnetic measurements have consequently also shown that the magnetizability is higher in areas with deformation martensite.

1 Einleitung

Als Kavitation wird die Bildung und anschließende Auflösung von Dampfblasen in Flüssigkeiten bezeichnet [1]. Dampfblasen entstehen, wenn der statische Druck einer Flüssigkeit unter den Dampfdruck der Flüssigkeit absinkt. Dies kann bei schnell fließenden Flüssigkeiten auftreten aber auch durch Ultraschall ausgelöst werden. Der schädigende Effekt tritt bei nachfolgendem raschen Druckanstieg und Implosion der Dampfblasen in der Nähe von Oberflächen auf. Dabei entsteht ein Mikrojet, der mit hoher Geschwindigkeit auf das Material trifft und mechanisch belastet [1].

Untersuchungen zur Kavitation in Bauteilen befassen sich üblicherweise mit Fluiddynamik zur Verhinderung der Dampfblasenbildung und nicht mit den verursachten Materialschädigungen. Dementsprechend findet man nur wenig Literatur bezüglich der Wechselwirkungen zwischen Kavitation und Werkstoff [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

Der Stahl AISI 316L (äquivalent Werkstoff Nr. 1.4404) wird vielfach eingesetzt und sollte laut Spezifikation rein austenitisch sein. Austenitische Stähle können aber auch ferritische Anteile enthalten, wenn, bedingt durch die Erstarrung, δ-Ferrit im Gefüge verbleibt. Infolge Verformung des Stahls erscheint der δ-Ferrit dann als länglicher Gefügebestandteil [8]. Als Ferrit ist auch der δ-Ferrit magnetisch und erhöht die Magnetisierbarkeit des austenitischen Stahls [9].

Als eine weitere Phase kann im Austenit sogenannter Umformmartensit gebildet werden. Dies erfolgt bei hohen Verformungsgraden nach der Bildung von Verformungszwillingen. Diese bilden somit die Vorstufe der Martensitbildung [10]. Aufgrund seiner Kristallstruktur ist auch der Martensit magnetisch. Martensit im Austenit verändert auch die Korrosionsbeständigkeit eines austenitischen Stahls, was zu bevorzugter Korrosion in den martensitischen Gefügebestandteilen führen kann [11, 12, 13].

An dem vorliegenden Stahl, der durch Kavitation stark geschädigt wurde (Bild 1), erfolgten auch Versuche, den Verformungsgradienten und die damit verbundene Martensitbildung zu dokumentieren.

2 Untersuchungsmethoden

Von der Probe (Bild 2a) wurden mit einer Trennmaschine zwei Scheiben abgeschnitten.

Eine Scheibe wurde für die metallographischen Untersuchungen in drei annähern gleich große Teile getrennt. Die zweite Scheibe wurde für die Magnetmessungen weiter, in etwa 0,3 g schwere Stücke geteilt.

Metallographie: Die Proben wurden in Epoxidharz eingebettet. Nach dem Planschleifen (P220) folgten die Polierstufen mit 9 bis 1 μm Diamantsuspensionen. Zur Entwicklung der Mikrostrukturen wurde das Ätzmittel Lichtenegger-Blöch verwendet [14]. Die präparierten Schliffe wurden mittels Lichtmikroskop (LOM) und Rasterelektronenmikroskop (REM) im Rückstreuelektronendetektor (BSE) untersucht.

Magnetische Messungen: Zur Bestimmung des magnetischen Sättigungsmoments wurde ein „Foerster-Koerzimat 1.096“ der Firma Foerster eingesetzt [15]. Es wurden etwa 0,3 g schwere Stücke verwendet und durch Vergleich mit einem Ferrit-Standard die Magnetisierbarkeit als prozentueller Ferrit-Gehalt der Probe errechnet. Aufgrund des relativ kleinen Probengewichts und des niedrigen magnetischen Anteils konnten allerdings nur halbquantitative Ergebnisse erhalten werden.

3 Ergebnisse und Diskussion

Durch die Kavitation wurde die Oberfläche des Stahls verformt und bis zum Durchbruch abgetragen (Bild 1a). In stark durch Kavitation belasteten Bereichen sind teilweise tiefe Löcher und eine stark aufgeraute Oberfläche erkennbar (Bild 2b). Diese Effekte verschwinden mit zunehmender Entfernung von der Durchbruchstelle (Bilder 2c und d).

3.1 Stark durch Kavitation verformte Oberfläche

Im polierten Querschnitt der Probe ist einerseits die stark zerfurchte Oberfläche des Stahls erkennbar (Bild 3a) und andererseits Löcher und Risse (Bilder 3b–g). Die Löcher sind bis zu 500 μm tief und enthalten auch Korrosionsprodukte (Bilder 3b, c, g). Die durch die Kavitation hervorgerufene Öffnung frischer, nicht passiver Metalloberfläche dürfte die Bildung der Korrosionsprodukte bewirkt haben. Von den Löchern, aber auch von der Oberfläche ausgehend, sind Risse zu sehen, die bis zu 1 mm in den Stahl hineinreichen (Bilder 3a, c, e).

Nach einer Ätzung sind die verformten Bereiche anhand der großen Dichte an Verformungszwillingen zu erkennen (Bilder 4a–c). Nahe der Oberfläche, tritt die höchste Dichte an Verformungszwillingen auf (Bild 4c), aber auch bläuliche Bereiche, die der Umformmartensit sein könnten. Das Ätzmittel nach Lichtenegger-Blöch färbt Ferrit nicht an, sehr wohl aber den Martensit, der hier hellblau erscheint. Ein weiteres Indiz, dass es sich um Martensit handelt, ist die Nähe zur stark verformten Oberfläche und zu Rissen, die bis zu 500 μm in den Stahl hineinreichen (Bilder 5a–c).

Der stark verformte Bereich reicht bis zu 1 mm unter die Oberfläche (Bild 4a) und nimmt dann kontinuierlich ab bis zum ungeschädigten Ausgangsgefüge des Stahls (Bilder 4d–f). Der austenitische Stahl hat eine Korngröße von bis zu 50 μm und weist auch ein Walzgefüge mit typischen Seigerungszeilen auf. Es sind auch geringe Anteile an δ-Ferrit vorhanden (Bild 4f).

3.2 Mittelmäßig beanspruchte Oberfläche

In Bereichen mit mittelmäßiger Kavitationsbelastung ist die stark verformte Zone mit starker Verzwillingung und Martensitbildung deutlich schmäler (ca. 500 μm) (Bilder 6a und b). Es sind auch Risse zu sehen welche aber nur etwa 100 μm lang sind. In den oberflächennahen Bereichen befindet sich vermutlich der Martensit und tritt im Vergleich zum stark Verformten Gefüge in geringerem Ausmaß auf (Bilder 6c–e). An den verformten Bereich schließt der Übergang zum unveränderten, austenitischen Gefüge an (Bild 6f).

Ein Übergang zu einem eher wenig beanspruchten Bereich ist in Bild 7 zu sehen. Die Schicht mit Verformungsmartensit ist hier etwa 300 μm dick (Bild 7a). Die Anzahl an Verformungszwillingen in den Austenitkörnern ist hier eher gering. Es ist aber auffällig, dass der Martensit dieselbe Orientierung aufweist, wie die Verformungszwillinge (Bilder 7b und c). Daraus könnte man ableiten, dass sich aus den Verformungszwillingen der Martensit bildet.

3.3 Wenig beanspruchte Oberfläche

In diesem Bereich sind keine Löcher oder Risse an der Oberfläche erkennbar (Bild 8a). Vereinzelte Verformungszwillinge sind bis in eine Tiefe von etwa 400 μm zu sehen (Bild 8b und c), jedoch wird kaum Martensit beobachtet.

3.4 Magnetische Messungen

Im Probensegment mit starker Verformung wurden etwa 3 Gew.% Ferrit gemessen. Nahe der Oberfläche nehmen die Werte in Bereichen mit geringerem Kavitationseinfluss auf 1,5 Gew.% ab. Im austenitischen Basismaterial wurden etwa 0,2 Gew.% Ferrit gemessen, was durch die Anwesenheit von δ-Ferrit erklärt werden kann.

Wenn auch nur halb-quantitativ haben die Messungen doch gezeigt, dass durch Kavitation der nicht-magnetische austenitische Stahl teilweise in magnetischen Umformmartensit umgewandelt wird.

4 Schlussfolgerungen

Ein durch Kavitation stark geschädigter Stahl der Qualität AISI 316L wurde untersucht. Entlang des Kavitationsgradienten wurden Proben entnommen und metallographisch präpariert.

Bereiche mit starker Kavitationsbelastung zeigen bis zu 500 μm tiefe Löcher und auch Risse. Dies ist auf einen erhöhten Materialabtrag zurückzuführen. In den austenitischen Körner ist hier eine große Anzahl an Verformungszwillingen zu sehen und nahe der Oberfläche liegt auch Umformmartensit vor.

Entlang des Gradienten nimmt die Menge an Verformungszwillingen ab und auch der Umformmartensit wird weniger.

Messungen der Magnetisierbarkeit haben folgerichtig auch gezeigt, dass diese in Bereichen mit Umformmartensit höher ist.

About the authors

Paul Linhardt is Ao. Univ. Prof. at TU-Wien. He is specialized on corrosion of metallic materials with emphasis on electrochemical mechanisms and a particular field of interest is microbially influenced corrosion. A major part of his work is related to failure analysis and material testing.

Maria Victoria Biezma is full professor of Materials Science and Engineering of University of Cantabria, Spain. She is currently involved in the study of the relationship between chemical composition, microstructure, and corrosion behavior of different metallic systems, mainly copper based alloys and superduplex stainless steels, as well as failure analysis of materials.

5 Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the company “Astilleros de Santander, S. A. U.” (“ASTANDER”, Spain) for the sample material.

The authors would like to thank the TU Vienna Library for the financial support through its Open Access Funding Program.

5 Danksagung

Wir möchten der Firma „Astilleros de Santander, S. A. U. (“ASTANDER”, Spain)“ für das Probenmaterial danken.

Die Autoren danken der TU Wien Bibliothek für die finanzielle Unterstützung durch ihr Open-Access-Förderprogramm.

References / Literatur

[1] Brennen, C. E.: Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. Oxford University Press, New York 1995, ISBN: 0-19-509409-3 DOI:10.1093/oso/9780195094091.001.000110.1093/oso/9780195094091.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

[2] Li, X. Y.; Yan, Y. G.; Ma, L.; Xu, Z. M.; Li, J. G.: Cavitation erosion and corrosion behavior of copper-manganese-aluminum alloy weldment, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 382 (2004) 1/2, pp. 82–89. DOI:10.1016/j.msea.2004.04.03210.1016/j.msea.2004.04.032Search in Google Scholar

[3] Qin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wu, Z.; Shen, B.; Liu, L.; Hu, W.: Microstructure design to improve the corrosion and cavitation corrosion resistance of a nickel-aluminum bronze, Corrosion Science 139 (2018), pp. 255–266. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2018.04.04310.1016/j.corsci.2018.04.043Search in Google Scholar

[4] Galván, L. G.; Biezma, M. V.; Linhardt, P.: Cavitation Typology in the Marine Environment in Copper-Based Alloys: Particular Case of Copper, Brass, NAB (Nickel Aluminium Bronze) and MAB (Manganese Aluminium Bronze. In: Proc. IV Iberoamerican Congress of Naval Engineering and 27th Pan-American Congress of Naval Engineering, Maritime Transportation and Port Engineering (COPINAVAL) (2024), pp. 181–187. DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-49799-5_2710.1007/978-3-031-49799-5_27Search in Google Scholar

[5] Biezma, M. V.; Galván, L. G.; Linhardt, P.: Cavitation of some copper alloys for naval propellers: electrolyte effect. August 2023IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering 1288 (2023) 1, p. 012056. DOI:10.1088/1757-899X/1288/1/01205610.1088/1757-899X/1288/1/012056Search in Google Scholar

[6] Linhardt, P.; Biezma, M. V.; Strobl, S.; Haubner, R.: Influence of Cavitation in Seawater on the Etching Attack of Manganese-Aluminum-Bronzes. Solid State Phenomena 341 (2023), pp. 25–30. DOI:10.4028/p-7nbo0010.4028/p-7nbo00Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sieber, A. B.; Preso, D. B.; Farhat M.: Cavitation bubble dynamics and microjet atomization near tissue-mimicking materials. Phys. Fluids 35 (2023), p. 027101. DOI:10.1063/5.013657710.1063/5.0136577Search in Google Scholar

[8] Strobl, S.; Haubner, R.: Delta-Ferrit und Umformmartensit in austenitischen Stählen. Sonderbände der Praktischen Metallographie zur 54. Metallographie Tagung, A. Neidel (Hrg.); DGM-Inventum GmbH (2020), S. 51–56. ISBN: 978-3-88355-422-8Search in Google Scholar

[9] Magnetische Eigenschaften nichtrostender Stähle. https://www.edelstahl-rostfrei.de/fileadmin/user_upload/ISER/downloads/MB_827.pdf (letzter Zugriff: 2025-05-05).Search in Google Scholar

[10] Roth, I.; Krupp, U.; Christ, H. J.; Kübbeler, M.; Fritzen, C.-P.: Deformation induced martensite formation in metastable austenitic steel during in situ fatigue loading in a scanning electron microscope, ESOMAT 2009, 06030 (2009). DOI:10.1051/esomat/20090603010.1051/esomat/200906030Search in Google Scholar

[11] Linhardt, P.; Biezma, M. V.; Haubner, R.; Schuster, R.; Wojcik, T.: Hollow wire corrosion of stainless steel ropes in a marine mooring system and its relation to microstructure. Materials and Corrosion. 74 (2023), pp. 818–830. DOI:10.1002/maco.20221369910.1002/maco.202213699Search in Google Scholar

[12] Strobl, S.; Haubner, R.; Linhardt, P.: Mikrobiell induzierte Lochkorrosion eines austenitischen Edelstahlrohres. in: Sonderbände der Praktischen Metallographie 2018, H. Clemens, S. Mayer, M. Panzenböck (Hrg.); INVENTUM GmbH (2018), pp. 279–284. ISBN: 978-3-88355-416-7Search in Google Scholar

[13] Strobl, S.; Linhardt, P.; Ball, G.; Haubner, R.: Pitting Corrosion on a Water Pipe of the Grade 1.4301. Pract. Metallogr. 55 (2018), pp. 469–477. DOI:10.3139/147.11051010.3139/147.110510Search in Google Scholar

[14] Vander Voort, G. F.: in: Metallography – Principles and Practice. ASM International, Materials Park, OH, 3rd printing, 2004Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ouda, K.; Danninger, H.; Gierl-Mayer, C.: Magnetic measurement of retained austenite in sintered steels – benefits and limitations, Powder Metallurgy 61 (2018), pp. 1–11. DOI:10.1080/00325899.2018.153085010.1080/00325899.2018.1530850Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 R. Haubner, P. Linhardt, S. Strobl, M. V. Biezma, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Contents

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Evaluation of damage mechanisms in full-forward rod extruded AISI 5115 steel by AI-based image segmentation

- A roll-headed pin from Getzersdorf, Austria, opens up interesting questions about iron metallurgy in the Hallstatt period

- Magneto-optical Kerr effect analysis of strain-induced martensite formation during flow forming of metastable austenitic steel AISI 304L

- Materials scientific challenges of a circular economy of high-alloy tool steels

- Cavitation-induced damage on a ship propeller’s Kort nozzle made of AISI 316L and investigation of the near-surface microstructural changes

- Preparation of aluminum thin films and laminates

- Preparation and microstructural examination of additively manufactured alloys 316L and 17-4PH

- Results of a round robin test on grain boundary determination by image analysis in the DGM working group ‘Quantitative Structural Analysis’

- Deep learning-based precipitate quantification in STEM images of complex steel microstructures

- A bronze fibula foot from the Roman Carnuntum, Lower Austria

- Optimization of preparation methods for EBSD analysis of highly metastable austenitic steels

- Picture of the Month

- Picture of the Month

- People

- Interview with Gaby Ketzer-Raichle on the occasion of the new edition of “Schumann Metallography”, published by Heinrich Oettel and Gaby Ketzer-Raichle

- News

- News

- Meeting Diary

- Meeting Diary

Articles in the same Issue

- Contents

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Evaluation of damage mechanisms in full-forward rod extruded AISI 5115 steel by AI-based image segmentation

- A roll-headed pin from Getzersdorf, Austria, opens up interesting questions about iron metallurgy in the Hallstatt period

- Magneto-optical Kerr effect analysis of strain-induced martensite formation during flow forming of metastable austenitic steel AISI 304L

- Materials scientific challenges of a circular economy of high-alloy tool steels

- Cavitation-induced damage on a ship propeller’s Kort nozzle made of AISI 316L and investigation of the near-surface microstructural changes

- Preparation of aluminum thin films and laminates

- Preparation and microstructural examination of additively manufactured alloys 316L and 17-4PH

- Results of a round robin test on grain boundary determination by image analysis in the DGM working group ‘Quantitative Structural Analysis’

- Deep learning-based precipitate quantification in STEM images of complex steel microstructures

- A bronze fibula foot from the Roman Carnuntum, Lower Austria

- Optimization of preparation methods for EBSD analysis of highly metastable austenitic steels

- Picture of the Month

- Picture of the Month

- People

- Interview with Gaby Ketzer-Raichle on the occasion of the new edition of “Schumann Metallography”, published by Heinrich Oettel and Gaby Ketzer-Raichle

- News

- News

- Meeting Diary

- Meeting Diary