Abstract

Despite the efforts of the Korean government to implement gender mainstreaming in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), the gender gap remains intact. The low rank of Gender Gap Indices (GGI) of Korea is mainly due to the low economic participation of women, especially in STEM. However, Korea has been steadily advancing in terms of government policies for women in STEM. The enactment of the law on fostering and supporting women in science and technology in 2002 is attributed to the collective efforts of women scientists and engineers through a women in STEM organization. The next task for women’s networks would be to identify the barriers of gender disparities by gathering the voices of women in STEM.

Introduction

STEM is the acronym of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics which has become a familiar term in itself worldwide. In countries like the United States of America (US), the term was first officially used in 2001 by the NSF [1]. The lack of skilled talents in STEM-related manufacturing jobs may have called for the need to promote STEM education [2]. In addition to the economic factors, STEM fields are recognized as basis for national competitiveness [3]. In fact in many countries including Korea, STEM literacy is linked to national prosperity and power.

One of the concerns on STEM today is the problem of gender disparities. Women are underrepresented in most STEM fields which have traditionally been perceived as those of men. Despite the efforts to increase the number of women, the ratio between the sexes has overall remained stable for decades [4]. In some countries, the drop in overall population has called for the need to adapt national policies in STEM and gender, reminiscent of the efforts to recruit women in these fields during and after World War I and World War II.

Today the issue of gender and STEM is no longer a national issue but of a global problem as reflected in all 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations (UN). However, the irony that countries with higher levels of gender equality revealing large gender gaps in STEM education as well as in the STEM workforce implies the need to shift gears from the past approaches. Stoet and Geary [4] showed that closing the gender gap in STEM will require more than improving science education and raising overall gender equality.

Although there is no single solution to closing the gender gap in STEM, supporting women’s networks in STEM has been recognized as one of the strategies by international organizations like UNESCO. How women in STEM in Korea have progressed through collective efforts in the historical context of STEM will be presented herein.

STEM and Korea

STEM development in Korea can be divided into two phases. The first phase is from 1962 to 1997 when science and technology (S&T) was considered the engine for economic growth. The second phase from 1997 is that of S&T innovation [5] (Fig. 1).

Chronicles of STEM policies in Korea before and after 1997.

Source: D. Oh et al., Dynamic history of Korean S&T (2010), KISTEP.

After the Korean war in 1950–1953, the Korean government had placed economic development based on S&T to be a national priority. In 1962, the 1st five year promotion plan on S&T is implemented and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) is established in 1967. S&T is known to have contributed immensely to the economic growth of Korea and this recognition had promoted the Ministry from a lower level, “cheo”, to a higher level “bu”, in 1998. Ironically, 1997 is the year Korea faced the economic crisis, better known to Koreans as the “IMF crisis”. Despite the need to cutback the overall spendings, the Korean government makes a bold decision to strenghthen S&T by allocating more research funds. In 2004, MOST is further promoted to a ministry headed by the Deputy Prime Minister. STEM policies take a turn from the hard core technology for economic development to a knowledge based scientific innovation. A special law on S&T is passed in 1997 followed by the Framework Act on S&T in 2001 (Fig. 1).

The continuous efforts to implement STEM as a government priority for economic growth of Korea is reflected in the Human Development Index (HDI) published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). As shown in Table 1, since 1990–2019, the HDI index of Korea increased from 0.731 to 0.916 (increase by 25.3 %). The increase is even more vivid when compared with the index of 1980 which was 0.628 (increase by 45.9 %). The HDI is attributable to the improved life expectancy, education and gross national income (GNI) per capita. As shown in Table 1, the GNI soared from 12 064 USDollars to 43 044 USD which is a 257 % increase over the 29 year period from 1990 to 2019.

HDI Indicesa for Korea, 1990–2019.

| Year | HDI value | Life expectancy at birth (years) | Expected year of schooling (years) | Mean year of schooling (years) | Gross National Income per capita (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 0.731 | 71.7 | 13.7 | 8.9 | 12 064 |

| 1995 | 0.781 | 73.9 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 16 733 |

| 2000 | 0.820 | 76.1 | 15.9 | 10.6 | 20 602 |

| 2005 | 0.860 | 78.7 | 16.7 | 11.4 | 25 340 |

| 2015 | 0.901 | 82.1 | 16.6 | 12.2 | 34 541 |

| 2019 | 0.916 | 83.0 | 16.5 | 12.2 | 43 044 |

-

aData from The 2018 Policy Report on Balanced Development of Human Resources for the Future, KWSE (2018) & UNDP Human Development Report (2020).

The gender gap in STEM in Korea

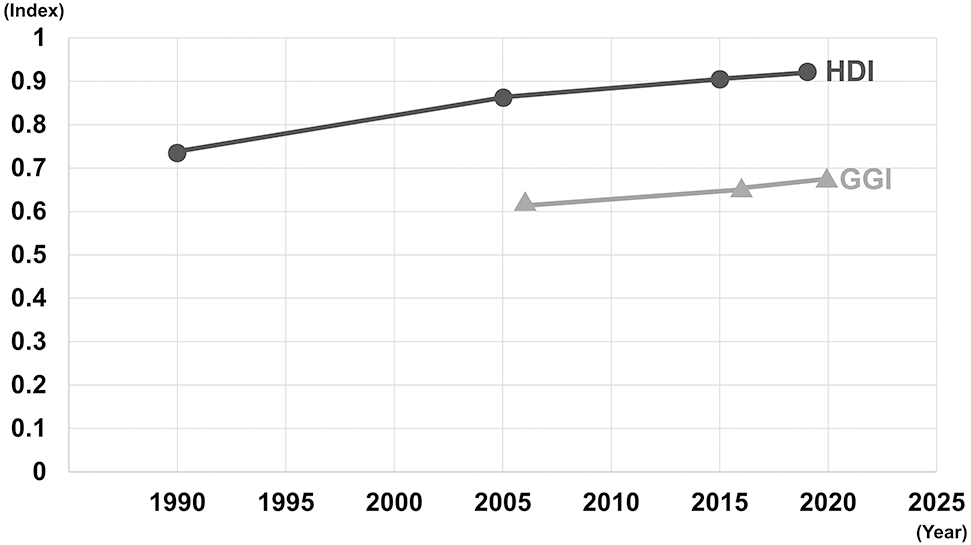

In contrast to the HDI of Korea, Gender Gap Indices (GGI) reported by the World Economic Forum (WEF) do not show much improvement since 2006 which is the year GGI was first published (Fig. 2). GGI is an index that measures gender equality in terms of women’s disadvantage compared to men. Thus, highly developed countries do not necessarily show high GGI values. As shown in Fig. 2, while HDI has reached 0.916 (1.000 means most developed) in 2019, GGI in 2020 remains at 0.672 (1.000 means fully closed gender gap). Looking at the rankings among the countries included in the WEF reports, Korea has been low ranked of 92 out of 115 countries in 2006 to 108 out of 153 in 2020 [6]. GGI ranks countries according to gender gap scores in four areas which are economy, education, politics and health (Table 2). The main reason for the low rank of Korea is the low political empowerment which was still at 0.179 in 2020; 1.000 is the highest attainable value for all these indices. This is a very slow increase from 0.067 in 2006. However, what is most vivid for Korea is the low economic participation and opportunity index of 0.555 in 2020. Very little improvement is seen from the 0.481 value in 2006 (Table 2).

The change in HDI and GGI values from 1990 to 2020 of Korea.

GGI values are not available before 2006. HDI values are from the Human Development Reports of the UNDP and GGI from the Global Gender Gap Reports of the World Economic Forum.

Gender gap indicesa for Korea, 2006–2020.

| Year (no of countries) | GGI (rank) | Economic participation and opportunity (rank) | Education attainment (rank) | Health and survival (rank) | Political empowerment (rank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 (115) | 0.616 (92) | 0.481 (96) | 0.948 (82) | 0.967 (94) | 0.067 (84) |

| 2012 (135) | 0.636 (108) | 0.509 (116) | 0.959 (99) | 0.973 (78) | 0.101 (86) |

| 2016 (144) | 0.649 (116) | 0.537 (123) | 0.964 (102) | 0.973 (76) | 0.120 (92) |

| 2020 (153) | 0.672 (108) | 0.555(127) | 0.973 (101) | 0.980 (1) | 0.179 (79) |

| Changes, ′20–′06 | 0.056 | 0.074 | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.112 |

-

aData from The 2018 Policy Report on Balanced Development of Human Resources for the Future, KWSE (2018) & GGI Report of the World Economic Forum (2020).

The economic participation rate (ECR) reported by WISET in STEM fields of Korea is shown in Fig. 3 [7]. The overall ECR for STEM fields was 91.4 % for male and 61.4 % for female, showing a 30.0 % gap in 2011. In 2019, a slight improvement in the gap is observed of 26.6 %. The gender gap in ECR for the natural sciences and engineering sepaprately show some difference. That of natural sciences is 24.3 % while for overall engineering it is 26.8 %. However, the gap is wider than for those working in the liberal arts or medical fields (Fig. 4).

Gender gap in economic participation rate in STEM in 2011 and 2019 in Korea.

Data from WISET report (2019).

Gender gap in economic participation rate in engineering, liberal arts, medical sciences, and natural sciences.

Data from WISET report (2019).

The fields with the smallest gender gap in ECR in natural sciences of BS graduates were in the sequence of Environmental Sciences (6.3 %), Life Sciences (6.8 %) and Chemistry (8.9 %) (Table 3). However, the ECR of female BS graduates was in the order of Environmental Sciences, Chemistry, and Life Sciences. In Engineering, they were in the sequence of Electrical and Computer Engineering (3.4 %), Information Technology (6.0 %), and Chemical Engineering (11.0 %). The ECR of female BS graduates was in the order of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Information Technology and Chemical Engineering.

Fields that show less gender gap in ECR in natural sciences and engineering.

| Fields (majors) | Female (%) | Male (%) | Gender gap (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural sciences | Life sciences | 52.4 | 59.2 | 6.8 |

| Chemistry | 54.8 | 63.7 | 8.9 | |

| Environmental sciences | 56.3 | 62.6 | 6.3 | |

| Engineering | Chemical engineering | 60.9 | 71.9 | 11.0 |

| Information technology | 65.1 | 71.1 | 6.0 | |

| Electrical engineering and computer engineering | 67.1 | 70.5 | 3.4 | |

The second phase of S&T development of Korea coincides with a period when gender mainstreaming is introduced as recommended by the UN in 1995 [8]. The first ministry on gender is established in 2001 (Fig. 5). Prior to this, the “Presidental Commission on Women’s Affairs” was established in 1998 to handle gender related matters. Interestingly, the Korean government’s endeavor for gender mainstreaming coincides with the efforts to bring innovations in STEM. In 1997, the special law on S&T innovation is passed as shown in Fig. 1. With the enactment of the Law on Fostering and Supporting Women in S&T (The Law, Fig. 1), a formal government commissioned center, National Institute for Supporting Women in Science and Technology (NIS-WIST, reorganized to WISET in 2012) opens in 2004, followed by four regional centers in Gwangju, Busan, Daejeon and Daegu [9]. These changes happened a few years after the first Korean women scientist’s collective movement happened, calling for policies for women in STEM.

Chronicles of STEM and Gender Policies in Korea.

Source: D. Oh et al., Dynamic history of Korean S&T (2010), KISTEP.

Women’s networks and enactment of the law

The first women in STEM organization in Korea is the Association of Korean Woman Scientists and Engineers (KWSE) which was established in 1993 in Daejeon where the Daeduk Science Town (DST, currently called Daeduk Innopolis) is located. KWSE started with 230 founding members who were mostly professionals holding Ph.D. degrees in Natural Sciences or Engineering and employed in research institutions or universities [10]. Considering that the total number of women in STEM in the DST then were about 400, the membership of KWSE reflects the eagerness of women in STEM for collective action. This is probably because women in STEM were then mostly hired as contingent employees. The founding President, Dr. Sehwa Oh’s interview[1] reveals the wage gap, discrimination in employment and overall male dominant working environment in the early 1990s [10]. The early KWSE members were those who went to college in the 1970s and 1980s which was a time when less than 30 % of the highschool graduating class went to college; among the female highschool graduates only 7.3 % went to college in 1980. Whether there is a direct relationship between the women’s networks and efforts to eradicate the gender gap will require more research. However, looking at how numbers have changed before and after the first network was formed is worth examining. What is clear is that since then many more women in STEM organizations were formed and members of KWSE played a crucial role in the enactment of the Act on Fostering and Supporting Women Scientists and Techicians[2] in 2002 [9]. It is not surprising that most of the gender in STEM issues in Korea are found in literature and publications after 2002.

Today, according to the Korea Federation of Women’s Science and Technology Associations, there are over 20 women in STEM not for profit organizations.[3] Adding women‘s committees within organizations like the Korean Chemical Society and medical science organizations brings the numbers to more than 70 networks. The rapid increase may be partly attributed to the support by the Korean government through programs like “small group support” [11] which would not have been possible without The Law enacted in 2002.

Progress in education attainment in STEM in Korea

The OECD report on education reveals a remarkable progress of the Republic of Korea over the past 60 years. The OECD report published in 2011 shows that Korea had become a country of high tertiary education attainment over a 50 year time span. What used to be a country of low education attainment where less than 10 % of the population among those born in 1933–1942 received college education, 60 % attained bachelor’s degrees among those born 1976–1984 (who went to college after 1995) [12]. As of 2015, the proportion of those aged 25–34 with tertiary education was reported to be 69 % which is higher than the OECD average of 42 % [13]. In STEM, Table 4 shows the sex ratio on education attainment. Before the 1990s female students were underrepresented in most fields that was considered “not feminine” which included social sciences, law, agriculture, natural sciences and engineering. The percentage of high school graduating class going on to college was around 30 % until the early 1990s [14]. Gender balance was reached in the natural sciences on the undergraduate level around 2006 and significant and steady increase was seen in the BS, MS and Ph.D. degree attainment in science and engineering over the years. As of 2019, Life Sciences and Chemistry had the highest and second highest number of female student ratio, respectively [7].

Ratio of women among the STEM graduating class (%).

| Degree and field | Year 1990 | Year 2000 | Year 2002 | Year 2006 | Year 2010 | Year 2018a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | STEMb | 15.9 | 27.0 | 28.0 | 31.9 | 28.5 | 31.9 |

| Sciencesc | 55.4 | 52.2 | 53.3 | ||||

| Engineering | 19.4 | 17.7 | 21.8 | ||||

| MS | STEM | 9.6 | 13.0 | 17.8 | 22.6 | 25.8 | 30.2 |

| Sciences | 43.7 | 49.1 | 51.9 | ||||

| Engineering | 12.6 | 14.6 | 19.8 | ||||

| Ph.D. | STEM | 5.3 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 18.5 | 21.6 | 22.2 |

| Sciences | 33.4 | 36.6 | 35.9 | ||||

| Engineering | 7.6 | 9.7 | 13.3 | ||||

-

Data from the Ministry of Education, Statistical Yearbook of Education (2002) & Database of WISET, Korea (2011)/aWISET (2019), Analysis Report on the Statistics of Development and Utilization of Women and Men in STEM in 2018. bSTEM refers to data from all natural sciences and engineering fields. cScience in Korea refers to Natural Sciences and Mathematics and do not include Social Sciences and Medicine.

Progress in women in STEM workforce

When the Ministry of Science and Technology proposed policies and preparation of a law to support women in STEM, KWSE hosted the public hearing in April 15, 2002[4] which led to the enactment in December, 2002. The rationale for the enactment was that the number of women graduating with STEM degrees were substantially increasing but their economic participation rate was low. Have numbers improved over the past 19 years? Very slowly.

Most of the natural sciences have achieved gender balance in numbers of students pursuing undergraduate studies. Chemistry for example shows the second highest female ratio next to Life Sciences. The membership of KWSE also reflects the relatively higher proportion of women in Chemistry; among all members, 15 % are in Chemistry only preceded by Life Sciences of 22.9 %.[5] However, the employment rate upon graduation of Chemistry majors is 54.8 % for female and 63.7 % for male students, showing a gap of 8.9 % (Table 3). Table 5 shows the latest data from WISET. A big gap in newly hired employees in STEM fields is still seen with only 28.9 % women among all new employees. The total gender share of the employees in STEM fields is 20 % thus the gap may be narrowing. However, what is noteworthy is the gap in the type of employment. Among the new recruits, only 57.6 % of women were employed in a noncontingent type, meaning a regular stable position. 42.4 % were employed in a contingent type compared to men where only 28.7 % of those employed were of contingent type. The gap between noncontingent vs contingent is 64.4:35.6 % for the overall employed women in STEM while 83.1:16.9 % for men [15].

Employment status of women and men in STEM.a

| Female (%) | Male (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| New recruitment (2018) | Gender share of the newly-hired employees in STEM field, regular | 3988 | 12 166 |

| Gender share of the newly-hired employees in STEM field, temporary | 2939 | 4908 | |

| Total | 6927 (28.9) | 17 074 (71.7) | |

| Employment | Gender share of the employees in STEM field, regular | 30 263 | 156 232 |

| Gender share of the employees in STEM field, temporary | 16 765 | 31 837 | |

| Total | 47 028 (20.0) | 188 069 (80.0) | |

| Promotion & management position | Gender share of the promoted R&D workforce | (17.4) | (82.6) |

| Gender share of the R&D manager | (10.0) | (90.0) | |

| Research project managers | Gender share of research project manager | (10.9) | (89.1) |

| Gender share of research project manager (project over 1 billion won) | (6.6) | (93.4) |

-

aData from 2018 Report on Women and Men in Science, Engineering & Technology, WISET.

Conclusion: what next for women’s networks?

Despite the efforts of the Korean government to bring more women into STEM fields, the gap is still vivid. Most seriously, the economic participation of women in STEM is quite stagnant. Barriers to gender equality have been identified but not overcome. Perhaps because the strategies to overcome the barriers did not involve the voices of women in STEM themselves. A recent study by KWSE in collaboration with the INWES APNN regional network has revealed that men and women perceive gender barriers differently [16]. Based on a study where young men and women in STEM born between 1988 and 1998 responded, statistically significant differences were observed between men and women in the perception of gender barriers [16]. The significance of the study was that it was initiated by an international network of women in STEM.

The importance of supporting women’s networks in STEM has become well recognized. One of UNESCO’s priority areas is Gender and STEM which includes strengthening networks of women scientists.[6] Moreover, G20 Leader’s Declaration of 2017, 2018 and 2019 shows particular focus on girls and women attaining skills in the natural sciences, medicine and technology, innovation and engineering. In 2016, G7 placed particular emphasis on STEM education. The Communique issued at the G7 Science and Technology Minister’s Meeting in Tsukuba in 2016 emphasized the importance of gender and human resource development for science, technology and innovation with the decision to support international networking of female researchers, scientists, engineers and students.[7] , [8]

It is high time for women in STEM networks to take the role in gathering the voices of their members in identifying the barriers that have caused the gender gap. Only through systematic studies that can be conducted by women in STEM themselves will policies be made and implemented to take action for a gender balanced world in STEM.

Article note:

A collection of invited papers on the gender gap in science.

References

[1] H. B. Gonzalez, J. J. Kuenzi. CRS report for congress (2012), Online, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42642.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[2] C. Giffi, B. Dollar, B. Gangula, M. D. Rodriguez. Deloitte Rev. 16, 97 (2015).Search in Google Scholar

[3] L. Dayton. Nature 581, S54 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01466-7.Search in Google Scholar

[4] G. Stoet, D. C. Geary. Psychol. Sci. 29, 581 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] D. Oh. Dynamic History of Korean S&T, KISTEP, Seoul, Korea (2010).Search in Google Scholar

[6] World Economic Forum. The Global Gender Gap Report 2020, Geneva, Switzerland (2020).Search in Google Scholar

[7] WISET. Analysis Report on the Statistics of Development and Utilization of Women and Men in STEM, Korea Center for Women In Science, Engineering and Technology, Seoul, Korea (2019).Search in Google Scholar

[8] S. Kim, K. Kim. Wom. Stud. Int. Forum 34, 390 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2011.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

[9] K.-B. Lee. Int. J. Gend. Sci. Technol. 2, 235 (2010).10.1017/S1759078710000528Search in Google Scholar

[10] KWSE, S. J. Joo, G. H. Cho, H. J. Yoon (Eds.). The 20 Year History of the Association of Korean Woman Scientists and Enigneers: The Future of Science and Technology made by Women Leadership 1993-2013, KWSE, Daejeon, Korea (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[11] J. S. Kim, H. Y. Park. Int. J. Gend. Sci. Technol. 6, 252 (2014).Search in Google Scholar

[12] OCED. Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, France, p. 15 (2011).Search in Google Scholar

[13] OCED. Education at a Glance 2016, OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, France, pp. 316–327 (2016).Search in Google Scholar

[14] J. S. Chung. Comp. Educ. Rev. 38, 487 (1994), https://doi.org/10.1086/447272.Search in Google Scholar

[15] WISET. 2009-2018 Report on Women in Science, Engineering and Technology, Myoungmoon Publishing, Seoul, Korea (2019).Search in Google Scholar

[16] K. J. B. Lee, H. Y. Park, J. S. Kim, Y. H. Kim. The 2018 Policy Report on Balanced Development of Human Resources for the Future, KWSE, Daejeon, Korea (2018).Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- The Gender Gap in Science – A PAC Special Topics Issue

- Invited papers

- The Global Survey of Scientists: encountering sexual harassment

- Women in physics

- Initiatives to tackle the gender gap in astronomy

- Women must be equal partners in science: gender-balance lessons from biology

- An apercu of the current status of women in ocean science

- ACM-W: global growth for a local impact

- The gender gap among scientists in Africa: results from the global survey and recommendations for future work

- Gender-based violence in higher education and research: a European perspective

- Socio-cultural developments of women in science

- Participation of women in science in the developed and developing worlds: inverted U of feminization of the scientific workforce, gender equity and retention

- How culture, institutions, and individuals shape the evolving gender gap in science and mathematics: an equity provocation for the scientific community

- What can women’s networks do to close the gender gap in STEM?

- Breaking the barriers – towards a more inclusive chemical sciences community

- Addressing the gender gap in science: lessons from examining international initiatives

- Women in science: from images to data

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- The Gender Gap in Science – A PAC Special Topics Issue

- Invited papers

- The Global Survey of Scientists: encountering sexual harassment

- Women in physics

- Initiatives to tackle the gender gap in astronomy

- Women must be equal partners in science: gender-balance lessons from biology

- An apercu of the current status of women in ocean science

- ACM-W: global growth for a local impact

- The gender gap among scientists in Africa: results from the global survey and recommendations for future work

- Gender-based violence in higher education and research: a European perspective

- Socio-cultural developments of women in science

- Participation of women in science in the developed and developing worlds: inverted U of feminization of the scientific workforce, gender equity and retention

- How culture, institutions, and individuals shape the evolving gender gap in science and mathematics: an equity provocation for the scientific community

- What can women’s networks do to close the gender gap in STEM?

- Breaking the barriers – towards a more inclusive chemical sciences community

- Addressing the gender gap in science: lessons from examining international initiatives

- Women in science: from images to data