Abstract

Chiral N-heterocyclic organoboronates represent promising intermediates for the preparation of various bioactive and pharmaceutical compounds. We recently reported the first asymmetric dearomative borylation of indoles by copper-catalyzed borylation. Then we further developed dearomatization/enantioselective borylation sequence. Chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydropyridines and chiral boryl-tetrahydroquinolines via the copper(I)-catalyzed regio-, diastereo- and enantioselective borylation of 1,2-dihydropyridines and 1,2-dihydroquinilines, which were prepared by the partial reduction of the corresponding pyridine or quinoline derivatives. This dearomatization/enantioselective borylation procedures provide a direct access to chiral piperidines and tetrahydroquinolines from readily available pyridines or quinolines in combination with the stereospecific transformation of the stereogenic C–B bond.

Introduction

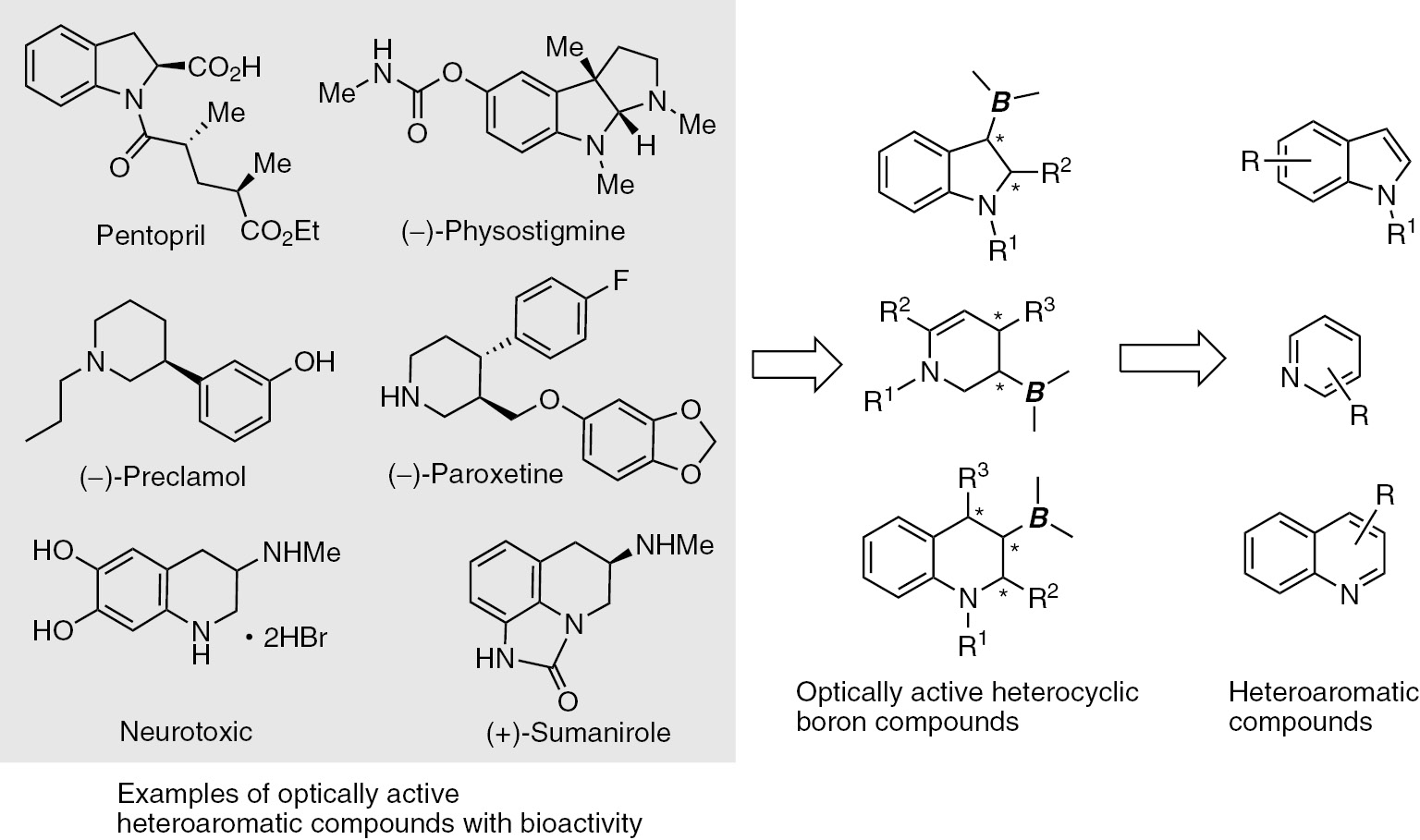

Aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds are ubiquitous in nature and readily available as synthesized compounds. The enantioselective dearomatization reactions of aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds are very powerful synthetic strategies [1], [2], [3], [4]. This method can be used to provide direct access to a wide variety of chiral cyclic and heterocyclic compounds, which are important structures of pharmaceutical drugs and various bioactive molecules. Thus, the development of novel reactions for the creation of consecutive stereogenic centers via the stereoselective dearomatization of aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds should have important practical implications for organic synthesis. Enantioenriched organoboron compounds are recognized as useful chiral building blocks in synthetic chemistry because chiral organoboron compounds are readily applied to the stereospecific functionalization of stereogenic C–B bonds [5], [6], [7]. The development of new methods for the metal-catalyzed enantioselective hydro- and protoboration reactions of prochiral C=C double bonds were extensively researched [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Despite the significant and rapid progress in this subject, there have been no studies on the enantioselective C–B bond-forming dearomatization reactions involving aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds [21], [22], [23]. The lack of research of this would be caused by the high activation energy to break the aromatic systems. The development of an enantioselective C–B bond-forming dearomatization reaction will provide an attractive approach for the synthesis of complex, functionalized cyclic molecules in combination with the stereospecific functionalization of a stereogenic C–B bond formed by the enantioselective borylations (Scheme 1). We recently published new dearomatization borylation reactions of indoles, pyridines, and quinolones [24], [25], [26]. These methods provide novel pathway for the chiral heteroaromatic compounds.

Schematic presentation of enantioselective dearomative borylation.

Results and discussion

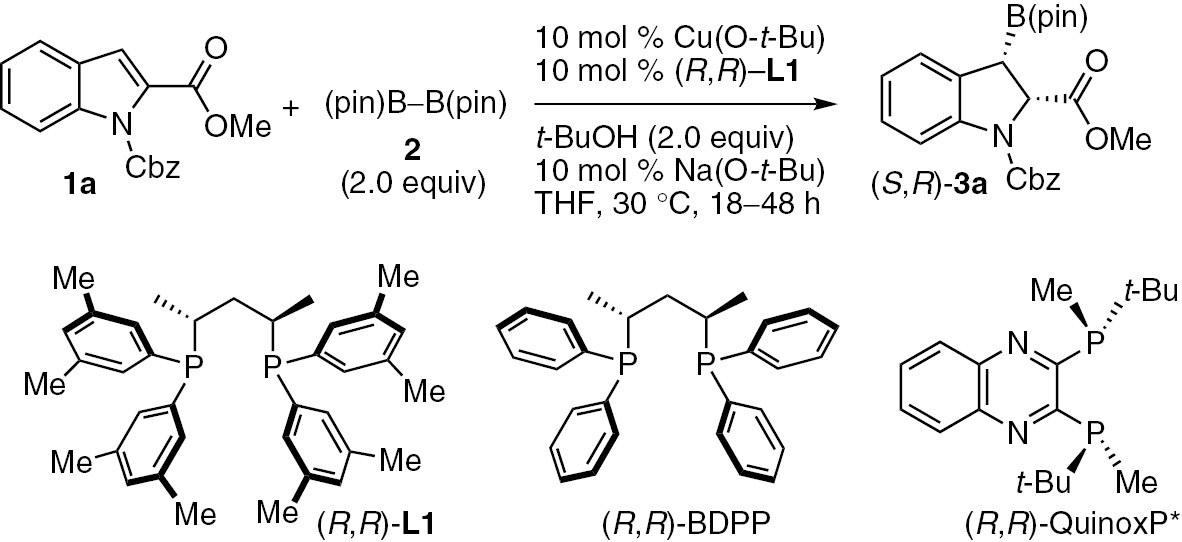

Dearomative asymmetric borylation of indole derivatives [24]

We envisioned that asymmetric dearomatization of indole derivatives will be a powerful method to access indolines and other heterocyclic compounds [27], [28], [29]. The optimization experiments revealed that the reaction of carboxybenzyl (Cbz)-protected methyl indole-2-carboxylate (1a) with bis(pinacolato)diboron (2) (2.0 equiv) in the presence of Cu(O-t-Bu)/(R,R)-L1 (10 mol%), Na(O-t-Bu) (10 mol%) and t-BuOH (2.0 equiv) in THF at 30°C afforded the desired dearomatization product (S,R)-3a in high yield (98%), with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivities (d.r. 97:3, 93% ee, Table 1, entry 1). Notably, no product was observed when the reaction was conducted in the absence of Cu(O-t-Bu) or the chiral ligand L1 (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). A lower yield (74%) of the dearomatization product 3a was obtained when Na(O-t-Bu) was omitted from the reaction (Table 1, entry 4), although the absence of t-BuOH led to a significant decrease in the yield and stereoselectivity of the product (33%, d.r. 76:24, 74% ee) (Table 1, entry 5). Less sterically hindered (R,R)-BDPP ligand resulted in a lower enantioselectivity (74% ee), which indicated that the nature of the substituent on the phenyl group of the ligand played an important role in the high enantioselectivity of the reaction (Table 1, entry 6). (R,R)-QuinoxP*, which showed excellent results in many enantioselective borylations [4], resulted in inferior results in terms of enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 7). The diastereoselectivity of B(pin) and the ester group was syn because of the protonation occurred from the enolate intermediate so as to avoid the steric hindrance of B(pin) and the alcohol [24]. Several other chiral bisphosphine ligands were also tested in the reaction, but they only showed inferior results compared to that of entry 1.

Asymmetric dearomative borylation of indole derivative 1a with 2.

| Entrya | Catalyst | Yieldb (%) | d.r.c | eed (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Standard conditions | 98 | 97:3 | 93 |

| 2 | No Cu(O-t-Bu) | <5 | – | – |

| 3 | No (R,R)-L1 | <5 | – | – |

| 4 | No Na(O-t-Bu) | 74 | 89:11 | 93 |

| 5 | No t-BuOH | 33 | 76:24 | 74 |

| 6 | (R,R)-BDPP instead of (R,R)-L1 | 98 | 89:11 | 74 |

| 7 | (R,R)-QuinoxP* instead of (R,R)-L1 | 93 | 90:10 | 27 |

-

aReactions were performed with 1a (0.5 mmol), Cu(O-t-Bu) (0.05 mmol), chiral ligand (0.05 mmol), bis(pinacolato)diboron 2 (1.0 mmol), Na(O-t-Bu) (0.05 mmol) and alcohol (1.0 mmol) in THF (1.0 mL), unless stated otherwise in the table. bDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture with an internal standard. cDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. dDetermined by HPLC analysis.

With the optimized conditions in hand, we investigated the scope of the reaction using various indole substrates (1b–1i, Scheme 2). Indole derivatives with a halo, methoxy or phenyl substituent at their six-position also reacted efficiently under the optimized conditions to give the corresponding dearomatization products with excellent stereoselectivity (3b–3f). The borylation of an indole wtih an ethyl ester group (3g) proceeded with high enantioselectivity (95% ee), but with an inferior product yield (52%). The reaction of fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected indole (3h) failed to provide any of the desired product, probably because of the reaction of the acidic proton of the Fmoc group with strong base, Na(O-t-Bu), which resulted in the formation of a complex mixture. We also found that Me-protected indoles were not suitable substrate (3i).

Asymmetric dearomative borylation of indole derivatives. aConditions: Cu(O-t-Bu) (0.05 mmol), (R,R)-L1 (0.05 mmol), 1 (0.5 mmol), bis(pinacolato)diboron 2 (1.0 mmol), Na(O-t-Bu) (0.05 mmol) and t-BuOH (1.0 mmol) in THF (1.0 mL). bIsolated yields. NMR yields are shown in parentheses.

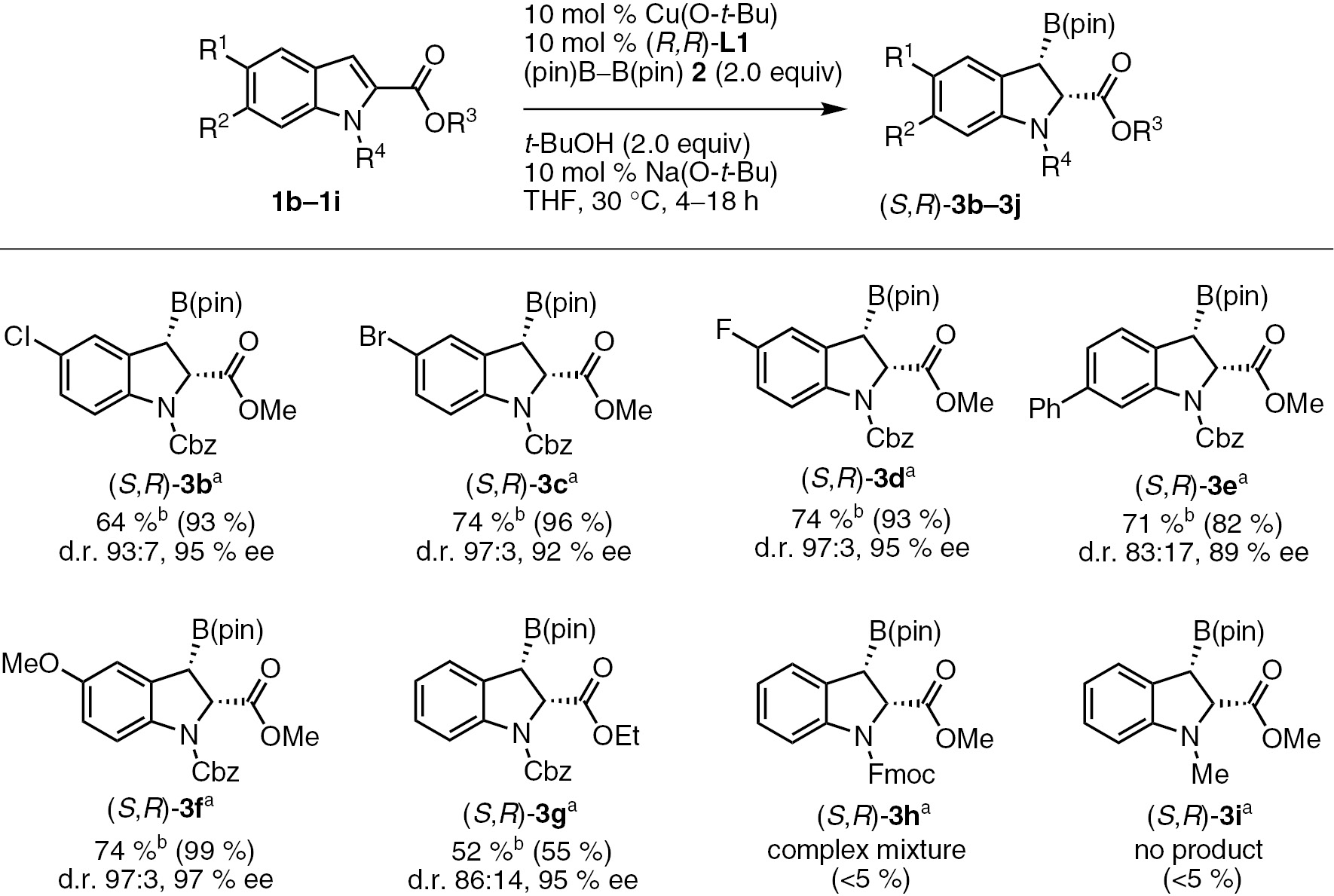

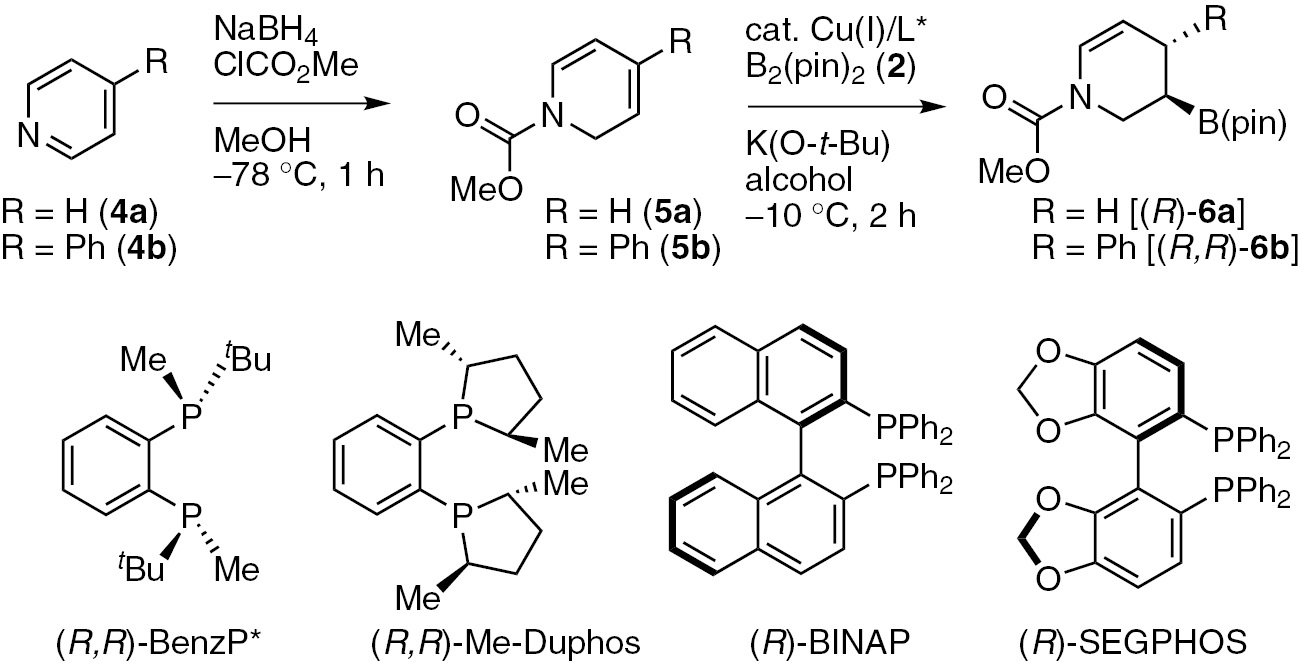

Sequential procedure of dearomative asymmetric borylation of pyridines [25]

Pyridines are excellent substrate for the dearomatization reaction, but they are unreactive toward copper(I)-catalyzed borylations under standard conditions [30], [31], [32], [33]. We then attempted a direct C–B bond forming method using an N-acyl pyridinium salt as the substrate under copper(I) catalysis with the concomitant dearomatization of the pyridine ring. Although the 1,2-borylation reaction proceeded as anticipated, we failed to isolate the desired product because there are many side products. Then we focused on the development of an alternative stepwise strategy involving the combination of Fowler’s dearomative reduction of pyridines with the copper(I)-catalyzed enantioselective borylation of the resulting unstable 1,2-dihydropyridines [34]. After the results of an extensive optimization process, we found that the reaction of methoxycarbonyl-protected 1,2-dihydropyridine 5a (R=H), which was isolated from pyridine 4a after the treatment of Fowler’s reduction method, with bis(pinacolato)diboron (2) (1.2 equiv) in the presence of CuCl/(R,R)-QuinoxP* (5 mol%), K(O-t-Bu) (20 mol%) and MeOH (2.0 equiv) in THF at −10°C afforded the chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydropyridine (R)-6a in high yield with excellent enantioselectivity (Table 2, entry 1). The use of (R,R)-BenzP* or (R,R)-Me-Duphos also provided excellent enantioselectivity (Table 2, entries 2 and 3). No product was observed when a triarylphosphine-type ligand, such as (R)-BINAP or (R)-SEGPHOS was used in the reaction (Table 2, entries 4 and 5). The catalyst with (R,R)-BDPP ligand afforded the product in high yield, but with poor enantioselectivities (97%, 55% ee, Table 2, entry 6). Notably, the reaction proceeded smoothly on a 5.0 mmol scale to give gram quantities of the desired product with excellent enantioselectivity (Table 2, entry 7). This enantioselective borylation reaction also proceeded efficiently with a lower loading (1 mol%) of the copper(I) catalyst and showed high enantioselectivity (99% ee), although this required a longer reaction time to complete (Table 2, entry 8). We then proceeded to investigate the borylation of 4-phenyl-1,2-dihydropyridine 5b in the presence of the Cu/QuinoxP* catalyst (Table 2, entry 9). However, we observed a lower enantioselectivity (25% ee) than that obtained under the same conditions, even though the regio- and diastereoselectivity were excellent (d.r. 99:1). A series of optimization reactions using 5b as a substrate was investigated. The results revealed that the use of the (R)-SEGPHOS chiral ligand with t-BuOH in a toluene/DME/THF co-solvent system gave the desired chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydropyridine (R,R)-6b bearing consecutive stereogenic centers in good yield (94%) with high diastereo- and enantioselectivity (d.r. 97:3, 92% ee) (Table 2, entry 10). The diastereoselectivity of B(pin) and the phenyl group was anti because syn protonation occurred from the alkyl copper intermediate [25].

The optimized conditions were used for further evaluation of the substrate scope of this sequential reaction (Scheme 3). The reactions of 1,2-dihydropyridines bearing various carbamate-type protecting groups (5a–5m) in the presence of the copper(I)/(R,R)-QuinoxP* catalyst proceeded to afford the desired dearomatization products [(R)-6a–(R)-6m] with excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 3). The 6-substituted 1,2-dihydropyridines (5h and 5i) were also borylated to afford the corresponding chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydropyridines [(R)-6h and (R)-6i] with excellent enantioselectivities without any of the other undesired regioisomers being detected (Scheme 3). The copper(I)/(R)-SEGPHOS catalyst promoted the enantioselective borylation of various 4-aryl-1,2-dihydropyridines (5b, 5j–5l) to give the corresponding borylated products with consecutive stereogenic centers with high diastereo- and enantioselectivities (d.r. 96:4–98:2, 93–96% ee). However, the reactions of 5m with copper(I)/(R)-SEGPHOS catalyst resulted in a low yield (10%). However, we found that the use of (R,R)-BDPP gave the corresponding products [(R,R)-6m], although the enantioselectivity was moderate (74% ee). (S,S)-6l was further derivatized to the (–)-paroxetine stereoselectively [25].

Sequential asymmetric dearomative borylation of various pyridine derivatives. aConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), (R,R)-QuinoxP* (0.025 mmol), 5 (0.5 mmol), 2 (0.6 mmol), MeOH (1.0 mmol) and K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol) in THF at –10 °C for 2 h. bConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), (R)-SEGPHOS (0.025 mmol), 5 (0.5 mmol), 2 (0.6 mmol), t-BuOH (1.0 mmol) and K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol) in THF/toluene/DME (1:6:6 – v/v/v) at 0 °C for 1 h. cConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), (R,R)-BDPP (0.025 mmol), 5 (0.5 mmol), 2 (0.6 mmol), t-BuOH (1.0 mmol) and K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol) in THF at 0 °C for 1 h. d4g was prepared by the treatment of 4f with K(O-t-Bu). e(S)-SEGPHOS was used.

Sequential asymmetric dearomative borylation of pyridine derivative 4a and 4b.

| Entrya | R | Chiral ligand | Alcohol | dr | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H (4a) | (R,R)-QuinoxP* | MeOH | – | 93 | 99 |

| 2 | H (4a) | (R,R)-BenzP* | MeOH | – | 92 | 98 |

| 3 | H (4a) | (R,R)-Me-Duphos | MeOH | – | 82 | 93 |

| 4 | H (4a) | (R)-BINAP | MeOH | – | <5 | – |

| 5 | H (4a) | (R)-SEGPHOS | MeOH | – | <5 | – |

| 6 | H (4a) | (R,R)-BDPP | MeOH | – | 97 | 55 |

| 7d | H (4a) | (R,R)-QuinoxP* | MeOH | – | 96 | 99 |

| 8e | H (4a) | (R,R)-QuinoxP* | MeOH | – | 91 | 99 |

| 9f | Ph (4b) | (R,R)-QuinoxP* | MeOH | 99:1 | 83 | 25 |

| 10f | Ph (4b) | (R)-SEGPHOS | t-BuOH | 97:3 | 94 | 92 |

-

aConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), ligand (0.025 mmol), 4 (0.5 mmol), bis(pinacolato)diboron 2 (0.6 mmol), alcohol (1.0 mmol) and K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol) in THF; bNMR yield; cthe ee values were determined by HPLC analysis of the corresponding benzoate ester; dthe reaction was carried out on a 5 mmol scale; e1 mol% CuCl and ligand were used. The reaction time was 16 h; fthe reaction was carried out at 0°C and the reaction time was 1 h.

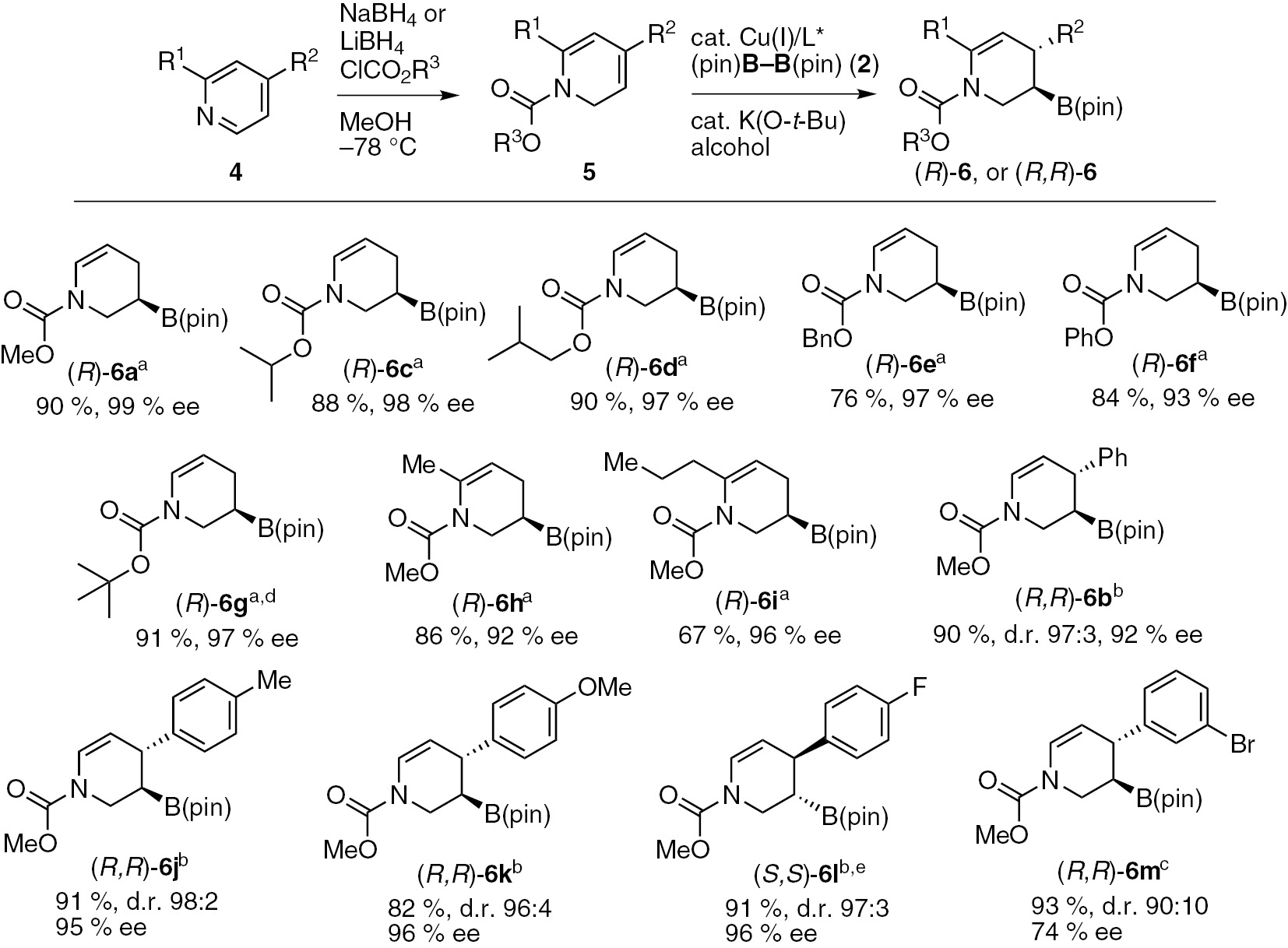

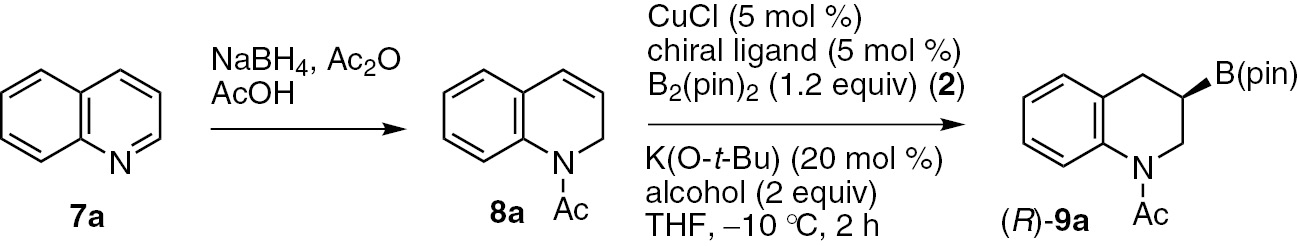

Sequential procedure of dearomative asymmetric borylation of quinolines [26]

The dearomative borylation of quinoline is also attractive target; [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42] however, same as the pyridine case, the direct borylation of quinoline failed. Optimization experiments for the dearomatization sequential procedure revealed that the reaction of N-acetyl 1,2-dihydroquinoline 8a which was prepared through the NaBH4 reduction of quinoline (7a) [11], with bis(pinacolato)diboron (2, 1.2 equiv) in the presence of CuCl/(R,R)-QuinoxP* (5 mol%), K(O-t-Bu) (20 mol%) and MeOH (2.0 equiv) in THF at 10°C afforded the desired chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydroquinoline (R)-9a in high yield (90%) with excellent enantioselectivity (98% ee) (Table 3, entry 1). The use of (R,R)-BenzP* or (R,R)-Me-Duphos instead of (R,R)-QuinoxP* also provided high levels of enantioselectivity (Table 3, entries 2 and 3, 97% ee and 95% ee, respectively). Contrary, lower chemical yields and enantioselectivities were observed when a triarylphosphine-type ligand, such as (R)-BINAP or (R)-SEGPHOS was used (Table 3, entries 4 and 5). Several other chiral ligands, including (R,R)-BDPP and (R,S)-Josiphos, were also screened in the reaction. Although these ligands both provided the desired borylation product, they afforded only poor enantioselectivities (Table 3, entries 6 and 7, –14% ee and –29% ee, respectively).

Sequential asymmetric dearomative borylation of quinoline derivative 7a.

| Entrya | Chiral ligand | Alcohol | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (R,R)-QuinoxP* | MeOH | 90 | 98 |

| 2 | (R,R)-BenzP* | MeOH | 96 | 97 |

| 3 | (R,R)-Me-Duphos | MeOH | 90 | 95 |

| 4 | (R)-BINAP | MeOH | 26 | 81 |

| 5 | (R)-SEGPHOS | MeOH | 12 | 58 |

| 6 | (R)-BDPP | MeOH | 94 | −14 |

| 7 | (R,S)-Josiphos | MeOH | 12 | −29 |

-

aConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), ligand (0.025 mmol), 8a (0.5 mmol), bis(pinacolato)diboron 2 (0.6 mmol), K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol), alcohol (1.0 mmol) in THF (1.0 mL). bDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture with an internal standard. cDetermined by HPLC analysis.

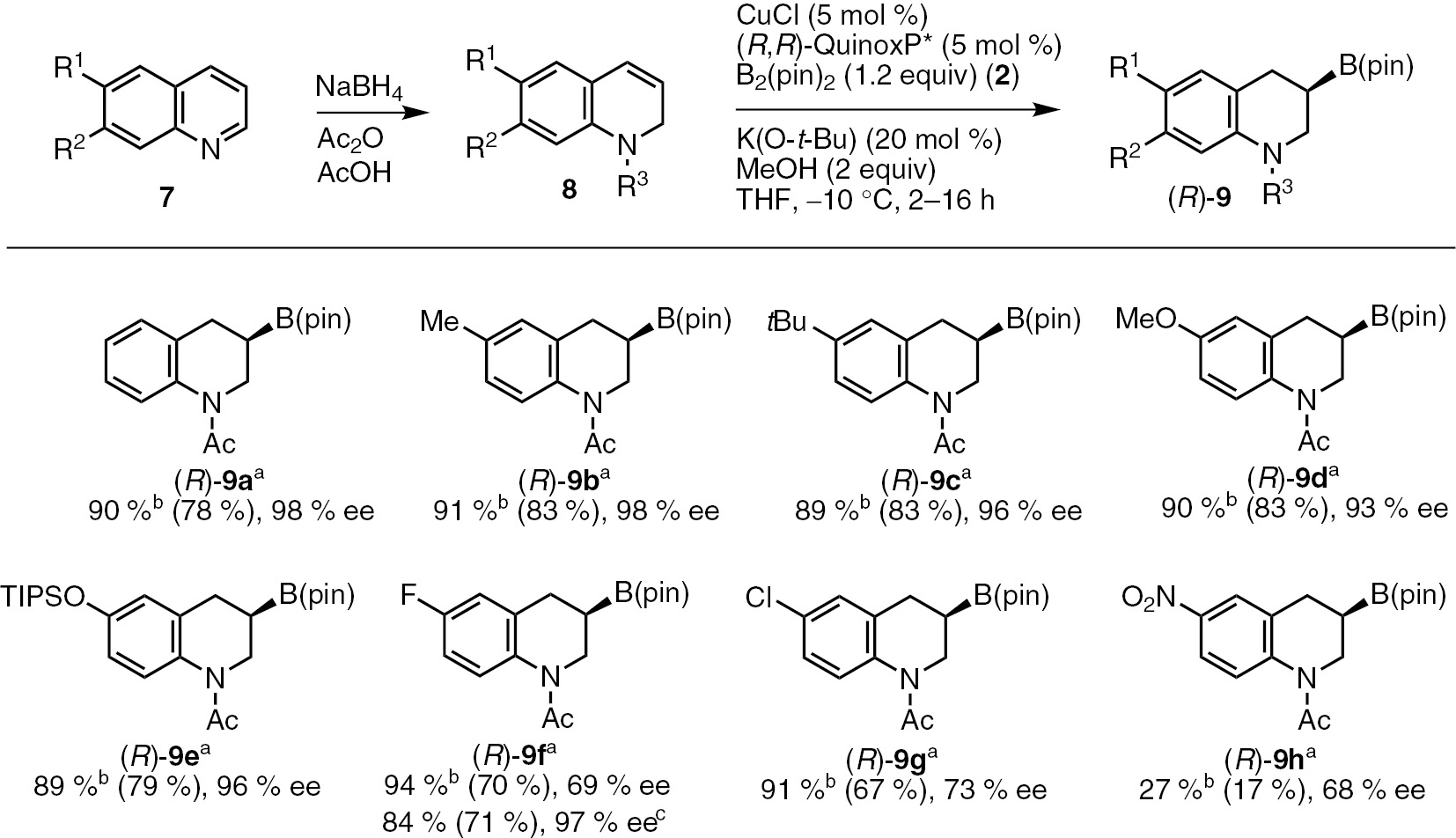

The optimized conditions were in hand, we conducted experiments for further evaluation of the substrate scope (Scheme 4). The borylation products in Scheme 4 were isolated by derivatized into the corresponding silyl ethers after a sequential oxidation/silylation of the C−B bond in the products. The reactions of 1,2-dihydroquinolines bearing Me-, t-Bu-, MeO- and TIPSO- groups at their six-position (8b–8e) in the presence of the copper(I)/(R,R)-QuinoxP* catalyst system proceeded to give the desired products [(R)-9b–(R)-9e] with high enantioselectivities (93–98% ee) (Scheme 4). The substrates with electron-withdrawing groups such as halogens and nitro group (2g and 2h) gave moderate enantioselectivities (68–73% ee) (Scheme 4).

Sequential asymmetric dearomative borylation of various quinoline derivatives. aConditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), (R,R)-QuinoxP* (0.025 mmol), 8 (0.5 mmol), bis(pinacolato)diboron 2 (0.6 mmol), K(O-t-Bu) (0.1 mmol), MeOH (1.0 mmol) in THF (1.0 mL). b1H NMR yields of the borylation products. Isolated yields of the corresponding silyl ethers after an sequential oxidation/silylation of borylation products 9 are shown in parenthesis. c(R,R)-BenzP* was used instead of (R,R)-QuinoxP*.

Summary

The dearomative asymmetric borylation can be a useful method for obtaining synthetic plat form for preparation of more complicated molecules including chiral heterocyclic structure. Very recently, Hou and co-workers reported copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric borylation of racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines including kinetic resolution process [44]. The various dearomatization procedure with other aromatic systems followed by copper(I)-catalyzed borylation are desirable for future research.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON-16), Hong Kong, 9–13 July 2017.

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by the MEXT (Japan) program (Strategic Molecular and Materials Chemistry through Innovative Coupling Reactions) of Hokkaido University, as well as the JSPS (KAKENHI Grant Numbers 15H03804 and 15K13633).

References

[1] C. X. Zhuo, W. Zhang, S. L. You. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 12662 (2012).10.1002/anie.201204822Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] C. X. Zhuo, C. Zheng, S. L. You. Acc. Chem. Res.47, 2558 (2014).10.1021/ar500167fSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] S. P. Roche, J. A. Porco. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.50, 4068 (2011).10.1002/anie.201006017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Q. P. Ding, X. L. Zhou, R. H. Fan. Org. Biomol. Chem.12, 4807 (2014).10.1039/C4OB00371CSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] D. G. Hall. Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis, Medicine and Materials, 2nd revised Ed, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011.10.1002/9783527639328Suche in Google Scholar

[6] M. Burns, S. Essafi, J. R. Bame, S. P. Bull, M. P. Webster, S. Balieu, J. W. Dale, C. P. Butts, J. N. Harvey, V. K. Aggarwal. Nature513, 183 (2014).10.1038/nature13711Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] S. N. Mlynarski, C. H. Schuster, J. P. Morken. Nature505, 386 (2014).10.1038/nature12781Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] J. E. Lee, J. Yun. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 145 (2008).10.1002/anie.200703699Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Y. M. Lee, A. H. Hoveyda. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 3160 (2009).10.1021/ja809382cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] V. Lillo, A. Prieto, A. Bonet, M. M. Diaz-Requejo, J. Ramirez, P. J. Perez, E. Fernandez. Organometallics28, 659 (2009).Suche in Google Scholar

[11] D. Noh, H. Chea, J. Ju, J. Yun. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 6062 (2009).10.1002/anie.200902015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] J. M. O‘Brien, K. S. Lee, A. H. Hoveyda. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 10630 (2010).10.1021/ja104777uSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] R. Corberan, N. W. Mszar, A. H. Hoveyda. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.50, 7079 (2011).10.1002/anie.201102398Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] J. C. H. Lee, R. McDonald, D. G. Hall. Nat. Chem.3, 894 (2011).10.1038/nchem.1150Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] H. Ito, S. Ito, Y. Sasaki, K. Matsuura, M. Sawamura. J. Am. Chem. Soc.129, 14856 (2007).10.1021/ja076634oSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] H. Ito, S. Kunii, M. Sawamura. Nat. Chem.2, 972 (2010).10.1038/nchem.801Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Y. Sasaki, C. M. Zhong, M. Sawamura, H. Ito. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 1226 (2010).10.1021/ja909640bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] K. Kubota, E. Yamamoto, H. Ito. Adv. Synth. Catal.355, 3527 (2013).10.1002/adsc.201300765Suche in Google Scholar

[19] E. Yamamoto, Y. Takenouchi, T. Ozaki, T. Miya, H. Ito. J. Am. Chem. Soc.136, 16515 (2014).10.1021/ja506284wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] K. Kubota, E. Yamamoto, H. Ito. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 420 (2015).10.1021/ja511247zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] K. Oshima, T. Ohmura, M. Suginome. J. Am. Chem. Soc.133, 7324 (2011).10.1021/ja2020229Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] K. Oshima, T. Ohmura, M. Suginome. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 3699 (2012).10.1021/ja3002953Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] T. Ohmura, Y. Morimasa, M. Suginome. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 2852 (2015).10.1021/jacs.5b00546Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] K. Kubota, K. Hayama, H. Iwamoto, H. Ito. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.54, 8809 (2015).10.1002/anie.201502964Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] K. Kubota, Y. Watanabe, K. Hayama, H. Ito. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 4338 (2016).10.1021/jacs.6b01375Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] K. Kubota, Y. Watanabe, H. Ito. Adv. Synth. Catal.358, 2379 (2016).10.1002/adsc.201600372Suche in Google Scholar

[27] D. Crich, A. Banerjee. Acc. Chem. Res.40, 151 (2007).10.1021/ar050175jSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] F. Kolundzic, M. N. Noshi, M. Tjandra, M. Movassaghi, S. J. Miller. J. Am. Chem. Soc.133, 9104 (2011).10.1021/ja202706gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] W. W. Zi, Z. W. Zuo, D. W. Ma. Acc. Chem. Res.48, 702 (2015).10.1021/ar5004303Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] J. A. Bull, J. J. Mousseau, G. Pelletier, A. B. Charette. Chem. Rev.112, 2642 (2012).10.1021/cr200251dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] J. Y. Ding, D. G. Hall. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 8069 (2013).10.1002/anie.201303931Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] E. M. P. Silva, P. Varandas, A. M. S. Silva. Synthesis45, 3053 (2013).10.1055/s-0033-1338537Suche in Google Scholar

[33] A. S. Dudnik, V. L. Weidner, A. Motta, M. Delferro, T. J. Marks. Nat. Chem.6, 1100 (2014).10.1038/nchem.2087Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] F. W. Fowler. J. Org. Chem.37, 1321 (1972).10.1021/jo00968a046Suche in Google Scholar

[35] D. Brundish, A. Bull, V. Donovan, J. D. Fullerton, S. M. Garman, J. F. Hayler, D. Janus, P. D. Kane, M. McDonnell, G. P. Smith, R. Wakeford, C. V. Walker, G. Howarth, W. Hoyle, M. C. Allen, J. Ambler, K. Butler, M. D. Talbot. J. Med. Chem.42, 4584 (1999).10.1021/jm9811209Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] V. Sridharan, P. A. Suryavanshi, J. C. Menendez. Chem. Rev.111, 7157 (2011).10.1021/cr100307mSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] L. Jean-Gerard, F. Mace, A. N. Ngo, M. Pauvert, H. Dentel, M. Evain, S. Collet, A. Guingant. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 4240 (2012). Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejoc.201200344/full.10.1002/ejoc.201200344Suche in Google Scholar

[38] P. Ferraboschi, S. Ciceri, P. Grisenti. Tetrahedron-Asymmetry24, 1142 (2013).10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.07.008Suche in Google Scholar

[39] G. Masson, C. Lalli, M. Benohoud, G. Dagousset. Chem. Soc. Rev.42, 902 (2013).10.1039/C2CS35370ASuche in Google Scholar

[40] V. Rawat, B. S. Kumar, A. Sudalai. Org. Biomol. Chem.11, 3608 (2013).10.1039/c3ob40320cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] M. Fochi, L. Caruana, L. Bernardi. Synthesis46, 135 (2014).10.1055/s-0033-1338581Suche in Google Scholar

[42] T. Nemoto, M. Hayashi, D. S. Xu, A. Hamajima, Y. Hamada. Tetrahedron-Asymmetry25, 1133 (2014).10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.06.018Suche in Google Scholar

[43] V. K. Tiwari, G. G. Pawar, R. Das, A. Adhikary, M. Kapur. Org. Lett.15, 3310 (2013).10.1021/ol401349aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] D. Kong, S. Han, R. Wang, M. Li, G. Zi, G. Hou. Chem. Sci.8, 4558 (2017).10.1039/C7SC01556ASuche in Google Scholar

©2018 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)