Abstract

The appearance of Ἰουδαίαν in the table of nations (Acts 2:9–11) has troubled interpreters for centuries. Several scholars have proposed to emendate the text. The argumentations for such conjectures vary in elaboration and support. This article gives a diachronic overview of the conjectured emendations. It concludes with an evaluation of the discussion from a phenomenological perspective and a summary of the used argumentation, thereby providing input for a reversed engineering approach to the issue.

1 Introduction

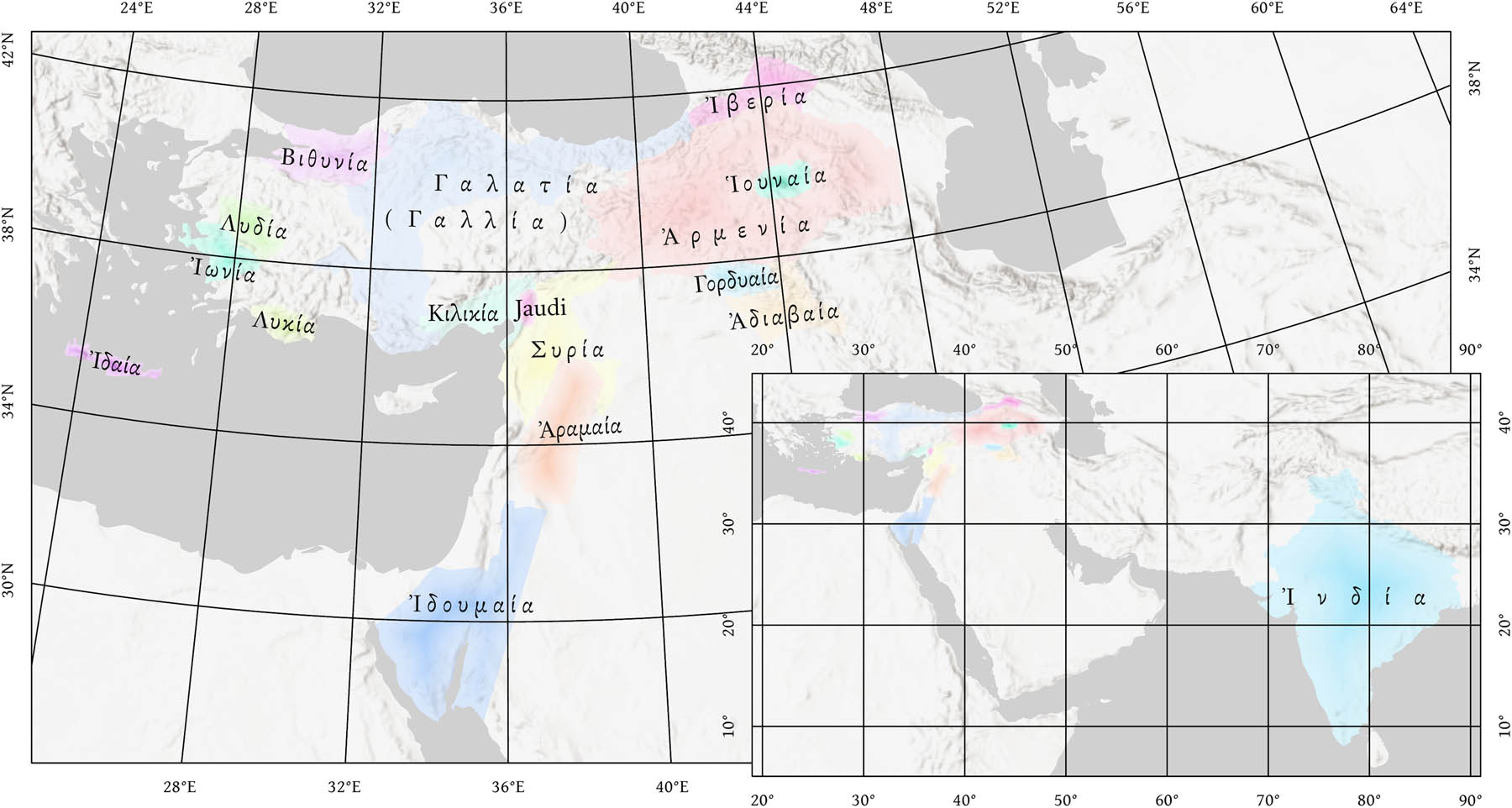

In the context of the Pentecost story (Acts 2:1–13), the author mentions a list of nations, the inhabitants of which miraculously hear the apostles speak in their own language. Over the centuries, this list gave rise to a vast amount of discussion. [1] Especially, Ἰουδαίαν in 2:9 has been regarded as intrinsically difficult on the basis of three observations: (1) the reference to Judea and hence Jews hearing the apostles speak in their native tongue seems awkward, [2] (2) the reference to Judea (v. 9) does not fit very well in the geographical arrangement [3] between Mesopotamia in the east and Cappadocia in the north [4] (Figure 1), and (3) Ἰουδαίαν should be regarded as an adjective.

The geographical structure of the list of nations in Acts 2:9–11.

The difficulties are not equally weighed [5] by interpreters, and diverse solutions have been offered. Literary connections with Old Testament table of nation traditions (esp. Gen 10), [6] Old Testament prophecies like Isa 11:11, contemporary Jewish [7] and astrological [8] geographical lists have been suggested and debated. Furthermore, a background in contemporary classical geography (i.e. Strabo) [9] has been discussed as well as the influence of the geographic viewpoint on Luke’s programmatic perspective. [10] Wendt’s suggestion that the Pentecost miracle presupposes a “new language” solves the problem but is as ingenious as it is speculative. [11]

Other interpreters tried to solve the difficulty by assuming a very early corruption in the transmission of the text. The next step to speculate about an alternative location in exchange for Judea was easily made, and a plethora of toponyms have been offered to emend the text. A partial overview of this discussion has been provided by Clemen, [12] Hatch, [13] and Metzger, [14] but the emendations proposed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have not been discussed systematically.

This article presents the discussion to date by providing an overview of the proposed conjectures, including the corresponding considerations, argumentation, and reception history in Section 2. Section 3 concludes this article with an evaluation of the discussion from a phenomenological perspective and a summary of the used argumentation.

2 A history of conjectures on Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9

The way interpreters have tried to emend the text of Acts 2:9 can be distinguished in three categories: (1) a change in grammatical function, (2) a correction to an assumed corruption of the text, and (3) by conjecture of a different toponym.

The information provided here mainly follows what is incorporated in the Amsterdam Database of New Testament Conjectural Emendation (ADNTCE). [15] Contrary to the ADNTCE, the data are classified according to the above-mentioned categories and subsequently presented in chronological order, thereby making the discussion and the interrelations between conjectures more explicit. For some cases, more information has been added to complement the data available in the ADNTCE.

2.1 Ἰουδαίαν as an adjective

It has been proposed to interpret the grammatical function of Ἰουδαίαν as an adjective. This proposal poses the question to which toponym it should be attached. In 1858, Heinrich Ewald, a German orientalist, Protestant theologian, and Biblical exegete, evaluates Ἰουδαίαν as “völlig unpassend” in the geographic arrangement, since he expects “das große Syrien” in the enumeration. He suggests Συρίαν might have been omitted during textual transmission. [16] According to Ewald, the text should be restored to Ἰουδαίαν Συρίαν. He reaffirmed his position in 1872, now adding the error is Luke’s who was unable to finish his work. [17] Both Meyer [18] and Wendt [19] rejected this conjecture. However, a similar case is made by Martin Hengel who interprets Ἰουδαίαν as Greater Judea, i.e. Syria. [20]

Adolf Hilgenfeld (1895) also took Ἰουδαίαν as an adjective. [21] He attached it however to Mεσοποταμίαν Ἰουδαίαν. Sahlin supported this proposal but wrongly attributed it to Von Harnack. [22] Metzger rebutted the idea since it is not clear to him “why Mesopotamia should deserve to be called ‘Judean.’” [23]

2.2 When in doubt, leave it out

Of the many solutions to the interpretive problem of Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9, the remedy to regard it as a later inclusion [24] or a very early corruption [25] of the text for which we are not able to identify the original has been widely discussed. The idea to regard it as a corruption was introduced by the English theologian, historian, and mathematician William Whiston [26] (1746), although an early citation in Theophylact [27] (1097) might hint in its direction. This line of reasoning stems from the observation that a certain geographical clustering can be perceived in the enumeration of countries and peoples if Ἰουδαίαν is left out. [28] The view has been reinvented twice [29] and has been equally opposed [30] as advocated. [31] Among its advocates, it finds Richard Pervo. [32]

Pervo’s other option, to mark the spot with a blank space, indicating that the original cannot be identified with reasonable certainty, resonates with the opinion of Johannes Marinus Simon Baljon (1898), who was familiar with the readings Συριαν, Aρμενιαν, Bιθυνιαν, Iδουμαιαν, and Ποντον τε και Aσιαν and their originators. Ultimately, Baljon regarded Ἰουδαίαν as a corruption. He did not adopt any of the offered emendations. [33]

2.3 Conjectured emendations

One of the earliest proposals to substitute Ἰουδαίαν with another toponym might be found in a writing of Aurelius Augustine (397). [34] He quoted Acts 2:9 with Ἀρμενίαν, but there is no accompanying remark. Although Tertullian (Adv. Jud. 7.4) cited the proposal, Augustine’s solution did not convince many. [35]

Some 15 years later, in 410, Jerome [36] cited Acts 2:7–11 in his commentary on Isaiah 4:11. In his citation, Ἰουδαίαν was substituted with Συρίαν. There is no discussion of the reading and therefore it is debatable whether it should be regarded as a proper conjecture. Baljon [37] and Blass [38] lend some support to it but do not seem very confident. Opponents simply advocate omission [39] or prefer different conjectures. [40]

The German philologist and writer, Caspar Barthius, proposed Ἰδουμαίαν in 1624. Since the narrative is located in Judaea, it seems redundant to explicitly mention Jews in the enumeration of countries.

He therefore proposes to read Ἰδουμαίαν. Support for this conjecture can be found in Josephus and Pliny who distinguish Ἰδουμαία as a separate region from Palestine. Further support might be found in Stephanus who calls the Idumeans Eβραίων ἔθνος. [41]

This suggestion was reinvented in 1720 by Richard Bentley [42] and once again by Otto Lagercrantz [43] in 1910. A few scholars [44] were in favour of this conjecture. Both Bloomfield [45] and Penn [46] argue for palaeographical confusion and they also provide manuscript support. Bloomfield claims support for this confounding from Josephus, and Penn refers to textual variants on Mk 3:7. Furthermore, understanding Ἰδουμαίαν as “that tract of country situated on the other side of Jordan, and south-east of Judaea, which was sometimes called Arabia Petraea,” [47] “exactly fits the geographical order.” [48] Others [49] were at least familiar with the proposal. However, quite a number of opponents can be found for this conjecture. [50]

The intrinsic difficulty of native Jews hearing their native language seems to have led another German, Erasmus Schmidius [51], mathematician and philologist, to propose Ἰνδίαν in 1634. [52] The logic behind this conjecture assumes a clustering according to the four cardinal directions on the compass. Exchanging Ἰουδαία for Ἰνδία would create a geographical cluster of Persia, Media, Parthia, Mesopotamia, and India in the East, before proceeding to the geographical clusters in the North, South, and West. Interestingly, there is a passage in John Chrysostom (403) which seems to offer support for this conjecture. [53] Although Schmidius’ proposal was considered by some [54] in the early twentieth century, the overarching opinion was against it. [55] One of the reasons to discard the suggestions was the misfit of the geographical order.

In 1703, Joannes Georgius Graevius, a German-Dutch classical philologist and professor in Duisburg, Deventer, and Utrecht, proposed Γορδυαίαν or Γορδαίαν, some region of Armenia. [56] The conjecture was reinvented by Francis Crawford Burkitt, Norris Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge. [57] Burkitt discards Ἰουδαίαν based on the geographical arrangement and discusses Tertullian’s Ἀρμενίαν. Although both Γορδυαία and Ἀρμενία appear to be ideal candidates from a geographical point of view, ultimately Burkitt prefers Γορδυαία on palaeographic grounds. His argumentation gained some support [58] but was mainly rejected. [59]

In 1720, the English classical scholar, critic, and theologian, Richard Bentley, preferred Λυδίαν over Ἰδουμαίαν. His emendation did not receive much support. Although it was sometimes only mentioned, [60] it was already rejected by Heringa in 1793, [61] followed by many others in subsequent years. [62] A variation to this suggestion can be found in the proposal Kαππαδοκίαν τε καὶ Λυδίαν by Jacob Bryant [63] (1767) who substitutes and transposes the word order. Not much is known about its reception. It is mentioned by Van Manen [64] and criticized by Michelsen. [65]

Gustav Georg Zeltner (†1738), a Lutheran theologian from Germany, introduced Ἰδαιᾶν or Ἰδαίαν. His view is only known to us from Schulthess who acknowledges a phonetical resemblance but discards the toponym due to its geographical insignificance. [66]

In 1742, Thomas Mangey, an English clergyman and scholar, known for his edition of Philo, proposed to restore Kιλικίαν in the text. [67] Some support can be found in geographical lists in Philo as well as in Acts 6:9. However, Mangey himself already observed Jas 1:1 and 1 Pet 1:1 seem to contradict his proposal. Although his suggestion suits the geographical arrangement, it did not find acclaim. [68]

The Dutch theologian and philologist Tiberius Hemsterhuis, Greek professor in Franeker and Delft, proposed Bιθυνίαν in 1766. A few scholars [69] followed. Van de Sande Bakhuyzen [70] and Valckenaer [71] were most explicit in their support, and from these resources we can reconstruct the line of reasoning, which is based on geographic and palaeographic arguments and supported from the co-occurrence in enumerations of geographical areas in classical sources. [72] The conjecture was widely discussed, though some scholars did not take a stance [73] but recognized a possible allusion to 1 Pet 1:1. [74] Others however rebutted this proposal, mainly because they favoured other emendations. [75]

Several other proposals, although less widely and rigorously debated, have been offered: in 1818, Johannes Schulthess, a Swiss, reformed theologian, assumed that the original reading Ἱουναίαν is a half-correct rendering of a Semitic name near Ararat. [76]

As an alternative to the option to omit Ἰουδαίαν, Jan Hendrik Adolf Michelsen, an Evangelical-Lutheran minister and modest adept of the Dutch radical critics, suggested Ἀραμαίαν (1879). [77] This position has also been put forward independently by Hatch in 1908. [78]

Professor of New Testament and religious history at the University of Bonn, Carl Clemen (1895) ascribed the conjecture Jaudi to Gunkel. [79] This proposal was supported by Eissfeldt [80] but opposed by Hatch. [81] The conjecture, however, appears to be based on erroneous transcription of Hebrew words. [82]

Thomas Kelly Cheyne, Oriel Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture at Oxford, suggested Ἰωνίαν in 1901. Cheyne was inspired by a similar conjecture on 1 Macc 8:8 (which substitutes Ionia for India), and he argues that place names are easily confounded. He agrees with Blass that Judea is “intolerable” in the geographical arrangement in Acts 2:9–11. [83] However, Hatch preferred Ἀραμαίαν against it. [84]

The eminent German biblical scholar, textual critic, orientalist, and editor of Novum Testamentum Graece, Eberhard Nestle, proposed Ἀδιαβαίαν in 1908. [85] His suggestion was implicitly contested by Samuel Krauss [86] who deduced from Rabbinic sources that “Erez Israel” could be used for (a part of) Mesopotamia, which in consequence might explain the occurrence of Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9. Hoennicke simply preferred Ἰνδίαν or Ἰδουμαίαν over Ἀδιαβαίαν. [87]

Although the German scholar Theodor Zahn previously expressed sympathy for Ἰνδίαν, [88] in 1916 he argued for Ἰουδαῖοι. [89] He appealed to an Old Latin translation to support his position. [90] Weinstock referred to this solution [91] but suggests to either omit Ἰουδαίαν or, preferably, read Ἀρμενίαν. [92] Ropes contested Zahn’s claim to support from an ancient Latin manuscript. [93]

Γαλατίαν or Γαλλίαν (both indicating the same area in Asia Minor) [94] was suggested in 1941 by Martin Dibelius, professor of New Testament in Heidelberg. He remarked “Judea may have been substituted by an unthinking copyist, especially since Judea is always close to the mind of a Bible reader.” [95] Dibelius admitted there is no specific palaeographic reason, but thought his proposal fitted the geographical arrangement well. Metzger [96] referred in his rebuttal to Weinstock’s argument about a geographic arrangement according to the zodiac circle, [97] but he seems neither convinced by that view. [98]

After having evaluated several other conjectures, with special attention for Λυδίαν, Eberhard Güting (1975) suggested Λυκίαν, which he regarded “im hohem Maß als passend” due to its importance in Roman times. [99]

Based on the geographical arrangement, John MacDonald Ross (1985) expected “a territory somewhere between Syria and the Caucasus Mountains”. In his opinion, Ἰβερίαν (an ancient name for modern Georgia) fits this requirement. [100]

3 Conclusion

The survey in the preceding section demonstrates the challenge posed by the text of Acts 2:9. Although interpreters detected serious internal difficulties with the reading Ἰουδαίαν, the supporting external manuscript evidence for this reading has been regarded as overwhelming. [101]

Simultaneously, the internal difficulties are not easily solved. Therefore, conjectural emendations abound: Cilicia, Armenia, Ida, Iounaia, Ionia, Jaudi, Iberia, Bithynia, Adiabene, Aramea, Idumea, Lydia, Gorduaia, Lycia, Galatia, Gallia, India, and Syria have all been suggested during the past centuries, cf. Figure 2.

Locations of the conjectural emendations to Ἰουδαία which can be found in the Amsterdam Database of New Testament Conjectural Emendation (ADNTCE).

When evaluating the historical overview from a phenomenological perspective, we observe that the issues with the originality of Ἰουδαίαν have been considered that serious, and each proposed conjectured emendation that unconvincing that numerous new attempts to solve the issue were attracted. Furthermore, confusion was created by imprecise formulation (see the case of Indian, note 51) or by attributing a conjecture erroneously ascribed to an honoured scholar (the case of Jaudi, see notes 79 and 82).

The overview is also illustrative in showing the diversity of considerations to opt for a certain candidate. In some cases, the fittingness in the geographical arrangement seems to have been the main motivation, while others sought to solve the issues in three different ways: by positing a scribal interpolation, by taking Ἰουδαίαν as an adverb (thus, interpreting a different grammatical function) to a different toponym, or by presuming palaeographical confusion.

In the end, “no one conjecture has proved generally acceptable.” [102] The unease remains and the discussion is undecided. In the second part of this article series, the issue will be revisited by addressing the question whether it might be possible to identify an acceptable alternative toponym assuming palaeographical confusion. It will use a computer algorithm to gauge the probability that Ἰουδαίαν could have been the result of a misreading of the original toponym due to letter confusion of majuscule script.

References

Aland, Kurt, Aland, Barbara, Karavidopoulos, Johannes, Martini, Carlo M., and Metzger, Bruce M. Novum Testamentum Graece. 28th ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Augustine, Aurelius. “Contra epistulam quam vocant fundamenti.” In De utilitate credendi, de duabus animabus, contra Fortunatum, contra Adimantum, contra epistulam fundamenti, contra Faustum. Corpus scriptorum ecclesiasticorum latinorum, edited by Joseph Zycha, 193–248. 25.1. Vienna: Tempsky, 1891.Search in Google Scholar

Baljon, Johannes Marinus Simon. Novum Testamentum Graece. Praesertim in usum studiosorum recognovit et brevibus annotationibus instruxit. Groningen: Wolters, 1898.Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, Charles Kingsley. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles: In Two Volumes. Vol. 1: Preliminary Introduction and Commentary on Acts I–XIV. The International Critical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament. London: T&T Clark, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

Barthius, Caspar. Adversariorum commentariorum libri LX quibus ex universa antiquitatis serie, omnis generis, ad vicies octies centum, auctorum, plus centum quinquaginta millibus, loci, tam gentilium quam christianorum, theologorum, iureconsultorum, medicorum, philosophorum, philologorum, oratorum, rhetorum etc. obscuri, dubii, maculati, illustrantur, constituuntur, emendantur, cum rituum, morum, legum, sanctionum, sacrorum, ceremoniarum, pacis bellique artium, formularum, locutionum denique, observatione et eludicatione tam locuplete et varia, ut simile ab uno homine nihil umquam in litteras missum videri possit. Eduntur praeterea ex vetustatis monumentis praeclara hoc opere non pauca, nec visa hactenus, nec videri sperata. Cum undecim indicibus, VII auctorum, IV rerum et verborum. Frankfurt, Main: Aubrius, n.d.Search in Google Scholar

Bauckham, Richard. “James and the Jerusalem Church.” In The Book of Acts in Its Palestinian Setting, Vol. 4 of The Book of Acts in Its First Century Setting, edited by Richard Bauckham, 415–80. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Bengel, Johann Albrecht. Gnomon Novi Testamenti, in quo ex nativa verborum vi simplicitas, profunditas, concinnitas, salubritas sensuum coelestium indicatur, 1st ed. Tübingen: Schramm, 1742.Search in Google Scholar

Bentley, Richard. In Bentleii Critica Sacra: Notes on the Greek and Latin Text of the New Testament, Extracted from the Bentley Mss. in Trinity College Library, edited by Arthur Ayres Ellis. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, 1862.Search in Google Scholar

Bishop, Eric Francis Fox. “Professor Burkitt and the Geographical Catalogue.” Journal of Roman Studies 42 (1952), 84–5.10.2307/297518Search in Google Scholar

Blass, Friedrich. Acta apostolorum sive Lucae ad Theophilum liber alter. Editio philologica apparatu critico, commentario perpetuo, indice verborum illustrata. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1895.Search in Google Scholar

Bloomfield, Samuel Thomas. Ἡ Kαινη Διαθηκη. The Greek Testament, with English Notes, Critical, Philological, and Exegetical, 1st ed. vol. 1. Cambridge: Smith, 1832.Search in Google Scholar

Bloomfield, Samuel Thomas. Ἡ Kαινη Διαθηκη. The Greek Testament, with English Notes, Critical, Philological, and Exegetical. Second Edition, Corrected, Greatly Enlarged, and Considerably Improved, vol. 1. London: Longman, Rees & Co., 1836.Search in Google Scholar

Bowyer, William. Conjectures on the New Testament, Collected from Various Authors, as Well in Regard to Words as Pointing: With the Reasons on Which Both Are Founded, 2nd ed. London: Nichols, 1772.Search in Google Scholar

Bowyer, William and Nichols, John. Critical Conjectures and Observations on the New Testament, Collected from Various Authors, as Well in Regard to Words as Pointing: With the Reasons on Which Both Are Founded … The Fourth Edition, Enlarged and Corrected. 4th ed. London: Nichols, 1812.Search in Google Scholar

Bruce, Frederick Fyvie. The Book of the Acts. Rev. ed. The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988.Search in Google Scholar

Bryant, Jacob. Observations and Inquiries Relating to Various Parts of Ancient History; Containing Dissertations on the Wind Euroclydon, and on the Island Melite, Together with an Account of Egypt in Its Most Early State, and of the Shepherd King. Cambridge: Archdeacon, 1767.Search in Google Scholar

Burkitt, Francis Crawford. “Text and Versions.” Encyclopaedia Biblica. A Critical Dictionary of the Literary, Political, and Religious History, the Archaeology, Geography, and Natural History of the Bible. IV. Q to Z:4977–5031.Search in Google Scholar

Cheyne, Thomas Kelly. “India.” Encyclopaedia Biblica. A Critical Dictionary of the Literary, Political, and Religious History, the Archaeology, Geography, and Natural History of the Bible. II. E to K:1145–2688.Search in Google Scholar

Chrysostom, John. Homiliae in Acta apostolorum. PG 60. Paris: Migne, 1862.Search in Google Scholar

Clemen, Carl. “Die Zusammensetzung von Apg. 1–5.” Theologische Studien und Kritiken 68 (1895), 297–357.Search in Google Scholar

Dibelius, Martin. “The Text of Acts: An Urgent Critical Task.” The Journal of Religion 21 (1941), 421–31.10.1086/482808Search in Google Scholar

Döderlein, Johann Christoph. “Review of Tiberius Hemsterhuis, Ti. Hemsterhusii orationes, quarum prima est de Paulo apostolo. L.C. Valckenari tres orationes, quibus subiectum est schediasma, specimen exhibens adnotationum criticarum in loco quaedam librorum sacrorum Novi Foederis. Praefiguntur duae orationes Ioannis Chrysostomi in laudem Pauli apostoli, cum veteri versione Latina Aniani, ex cod. MS. hic illic emendata ed. Lodewijk Casper Valckenaer; Leiden: Luchtmans & Honkoop, 1784.” Ausserlesene theologische Bibliothek 3:4 (1785), 268–78.Search in Google Scholar

Eissfeldt, Otto Wilhelm Hermann Leonhard. “‘Juda’ in 2. Könige 14, 28 und ‘Judäa’ in Apostelgeschichte 2, 9.” Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Martin-Luther-Universität, Gesellschafts- und Sprachwissenschaftliche Reihe 12 (1963), 229–38.Search in Google Scholar

Ewald, Heinrich. Geschichte des apostolischen Zeitalters bis zur Zerstörung Jerusalem’s. Göttingen: Dieterich, 1858.Search in Google Scholar

Ewald, Heinrich. Die drei ersten Evangelien und die Apostelgeschichte übersetzt und erklärt. Zweite, vollständige Ausgabe. Zweite hälfte. Göttingen: Dieterich, 1872.Search in Google Scholar

Gilbert, Gary. “The List of Nations in Acts 2: Roman Propaganda and the Lukan Response.” Journal of Biblical Literature 121:3 (2002), 497.10.2307/3268158Search in Google Scholar

Griesbach, Johann Jakob. Novum Testamentum Graece. Textum ad fidem codicum versionum et patrum recensuit et lectionis varietatem adiecit D. Io. Iac. Griesbach. Volumen II. Acta et epistolas apostolorum cum Apocalypsi complectens. Editio secunda emendatior multoque locupletior. Halle: Curtius, 1806.Search in Google Scholar

Güting, Eberhard. “Der geographische Horizont der sogenannten Völkerliste des Lukas (Acts 2 9-11).” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche 66 (1975), 149–69.Search in Google Scholar

Haenchen, Ernst. Die Apostelgeschichte. Neu übersetzt und erklärt. 7., durchgesehene und verbesserte Auflage dieser Neuauslegung. 16th ed. Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar über das Neue Testament 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1977.Search in Google Scholar

Harnack, Adolf von. Die Apostelgeschichte. Vol. 3 of Beiträge zur Einleitung in das Neue Testament. Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1908.Search in Google Scholar

Hatch, William Henry Paine. “Zur Apostelgeschichte 2, 9.” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche 9 (1908), 255–56.Search in Google Scholar

Heinrichs, Joannes Henricus. Novum Testamentum Graece perpetua annotatione illustratum. Editionis Koppianae vol. III. part. I. complectens Acta Apostolorum Cap. I–XII. Göttingen: Dieterich, 1809.Search in Google Scholar

Hengel, Martin. “Ioudaia in the Geographical List of Acts 2: 9–11 and Syria as Greater Judea.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 10 (2000), 161–80.10.2307/26422215Search in Google Scholar

Heringa, Jodocus. Vertoog over het vereischt gebruik, en hedendaegsch misbruik der kritiek, in de behandelinge der heilige Schriften. Verhandeling van het genootschap tot verdediging van den christelijken godsdienst. Amsterdam: Allart, van der Aa & Scheurleer, 1793.Search in Google Scholar

Hilgenfeld, Adolf. “Die Apostelgeschichte nach ihren Quellenschriften untersucht.” Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Theologie 38 (1895), 65–115.Search in Google Scholar

Hoennicke, Gustav. Die Apostelgeschichte. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1913.Search in Google Scholar

Hülsemann, Friedrich. “Dritte Fortsetzung der allgemeinen Bemerkungen über das Bibelstudium u. s. w. Ueber die Anwendung der Conjekturalkritik auf das N. T.” Neue theologische Bibliothek 3 (1800), 316–36.Search in Google Scholar

Jerome. “Commentariorum in Esaiam libri I–XI.” In Corpus Christianorum: Series Latina 73, edited by Marcus Adriaen. Turnhout: Brepols, 1963.Search in Google Scholar

Keener, Craig S. Acts: An Exegetical Commentary – Introduction and 1:1-2:47, vol. 1. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Kilpatrick, George Dunbar. “Conjectural Emendation in the New Testament.” In New Testament Textual Criticism: Its Significance for Exegesis: Essays in Honour of Bruce M. Metzger, edited by Eldon Jay Epp & Gordon D. Fee, 349–60. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Georg Christian. “Sylloge Notabiliorum aut Celebratiorum Coniecturarum de Mutanda Lectione in ll. N. T.” In Novum Testamentum Graece. Recognovit atque insignioris lectionum varietatis et argumentorum notationes subiunxit, edited by Georg Christian Knapp, 767–84. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, 1813.Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, Georg Christian. “Sylloge Notabiliorum aut Celebratiorum Coniecturarum de Mutanda Lectione in ll. N. T.” In Novum Testamentum Graece. Recognovit atque insignioris lectionum varietatis et argumentorum notationes subiunxit, edited by Moritz Rödiger, 767–91. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, 1829.Search in Google Scholar

Krans, Jan & Lietaert Peerbolte, Bert Jan. “The Amsterdam Database of New Testament Conjectural Emendation,” 2016–present. http://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/nt-conjecturesSearch in Google Scholar

Krauss, Samuel. “Erez Israel’ im weiteren Sinne.” Zeitschrift des deutschen Palästina-Vereins 33 (1910), 224–25.Search in Google Scholar

Kuinoel, Christianus Theophilus. Commentarius in libros Novi Testamenti historicos. Volumen IV. Acta apostolorum. Leipzig: Barth, 1818.Search in Google Scholar

Lagercrantz, Otto. “Zu Act. Ap. 2:9.” Eranos. Acta philologica suecana 10 (1910), 58–60.Search in Google Scholar

Loisy, Alfred Firmin. Les Actes des apôtres. Paris: Nourry, 1920.Search in Google Scholar

Mangey, Thomas, ed. Φιλωνος του Iουδαιου τα ευρισκομενα απαντα. Philonis Judaei opera quae reperiri potuerunt omnia. Textum cum MSS. contulit, quamplurima etaim e Codd. Vaticano, Mediceo, et Bodleiano, Scriptoribus item vetustis, necnon Catenis Graecis ineditis, adiecit, Interpretationemque emendavit, universa Notis et Observationibus illustravit. London: Bowyer, 1742.Search in Google Scholar

Metzger, Bruce Manning. “‘Methodological Weakness’ (Review of Martin Dibelius, Studies in the Acts of the Apostles [Ed. Heinrich Greeven; London: SCM, 1956]).” Interpretation. A Journal of Bible and Theology 11 (1957), 94–6.10.1177/002096435701100112Search in Google Scholar

Metzger, Bruce Manning. “Ancient Astrological Geography and Acts 2:9-11.” In Apostolic History and the Gospel: Biblical and Historical Essays Presented to F. F. Bruce on His 60th Birthday, edited by W. Ward Gasque and Ralph P. Martin, 123–33. Exeter: Paternoster, 1970.10.1163/9789004379282_004Search in Google Scholar

Metzger, Bruce Manning. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, a Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament (4th Rev. Ed.), 2nd ed. London, New York: United Bible Societies, 1994.Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, Heinrich August Wilhelm. Kritisch-exegetisches Handbuch über die Apostelgeschichte, 3rd ed. Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar über das Neue Testament (Meyer-Kommentar) 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1861.Search in Google Scholar

Michelsen, Jan Hendrik Adolf. In Submission to “Prijsvraag G 94: een verhandeling over de toepassing van de conjecturaal-kritiek op den tekst van de schriften des Nieuwen Testaments (1877), II–14. ATS 1258. Haarlem: Archief Teylers Stichting, 1879.Search in Google Scholar

Nestle, Eberhard. “Ein eilfter Einfall zu Apostelgeschichte 2, 9.” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche 9 (1908), 253–54.Search in Google Scholar

Olshausen, Hermann. Biblischer Commentar über sämmtliche Schriften des Neuen Testaments zunächst für Prediger und Studirende. Zweiter Band. Das Evangelium des Johannes, die Leidensgeschichte und die Apostelgeschichte enthaltend. Königsberg, Prussia: Unzer, 1832.Search in Google Scholar

Pallis, Alexandros. Notes on St Luke and the Acts. London: Milford, 1928.Search in Google Scholar

Pearce, Zachary. In A Commentary, with Notes, on the Four Evangelists and the Acts of the Apostles; Together with a New Translation of St. Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, with a Paraphrase and Notes. To Which Are Added Other Theological Pieces, edited by John Derby. Vol. II. London: Cadell, 1777.Search in Google Scholar

Penn, Granville. Annotations to the Book of the New Covenant: With an Expository Preface. London: Duncan, 1837.Search in Google Scholar

Pervo, Richard Ivan. Acts: A Commentary. Hermeneia, edited by Harold W. Attridge. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Preuschen, Erwin. Die Apostelgeschichte. Handbuch zum Neuen Testament 4.1. Tübingen: Mohr, 1912.Search in Google Scholar

Ropes, James Hardy. The Beginnings of Christianity. Part I. The Acts of the Apostles. Vol. III. The Text of Acts. London: Macmillan, 1926.Search in Google Scholar

Rovers, Marinus Anne Nicolaas. Submission to “Prijsvraag G 94: een verhandeling over de toepassing van de conjecturaal-kritiek op den tekst van de schriften des Nieuwen Testaments (1877)”. ATS 1257. Haarlem: Archief Teylers Stichting, 1879.Search in Google Scholar

Sahlin, Harald. “Emendationsvorschläge zum griechischen Text des Neuen Testaments II.” Novum Testamentum 24 (1982), 180–9.10.1163/156853682X00033Search in Google Scholar

Schmidius, Erasmus. Versio Novi Testamenti nova, ad Graecam veritatem emendata, et notae ac animadversiones in idem: quibus partim mutatae alicubi Versionis redditur ratio, partim alia necessaria monentur. Accedit sacer contextus Graecus, cum Versione veteri: nec non Index Rerum et Verborum locupletissimus. Nuremberg: Michael Endter, 1658.Search in Google Scholar

Schmiedel, Paul Wilhelm. “Spiritual Gifts.” Encyclopaedia Biblica. A Critical Dictionary of the Literary, Political, and Religious History, the Archaeology, Geography, and Natural History of the Bible. IV. Q to Z:4755–76.Search in Google Scholar

Schmiedel, Paul Wilhelm. “Pfingsterzählung und Pfingstereignis.” Protestantische Monatshefte 24 (1920), 73–86.Search in Google Scholar

Schulthess, Johannes. De charismatibus spiritus sancti. Pars prima. De vi et natura, ratione et utilitate dotis linguarum, in primos discipulos Christi collatae atque in posteros omnes deinceps ad finem usque seculi perennantis. Quam prolusionem muneris ineundi dedit. Leipzig: Reclam, 1818.Search in Google Scholar

Scott, Edward. “ACTS II. 9.” The Athenaeum 1 (1894), 180.Search in Google Scholar

Scott, James M. “Luke’s Geographical Horizon.” In The Book of Acts in Its Graeco-Roman Setting. Vol. 2 of The Book of Acts in Its First Century Setting, edited by David W. J. Gill & Conrad H. Gempf, 483–544. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994.Search in Google Scholar

Spitta, Friedrich. Die Apostelgeschichte, ihre Quellen und deren geschichtlicher Wert. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, 1891.Search in Google Scholar

Spitzel, Gottlieb. Sacra bibliothecarum illustrium arcana retecta, sive mss. theologicorum, in praecipuis Europa bibliothecis extantium designatio, cum praeliminari dissertatione, specimine novae bibliothecae universalis, et coronide philologica. Augsburg: Goebel, 1668.Search in Google Scholar

Theophylact of Ohrid. “Ex S. Joannis Chrysostomi exegeticis et nonnullorum patrum expositiones in Acta Apostolorum concise ac breviter collectae a ….” In Opera quae reperiri potuerunt omnia, edited by Jacques-Paul Migne. Patrologia Graeca 125. Paris: Migne, 1864.Search in Google Scholar

Valckenaer, Lodewijk Casper. In Schediasma, specimen exhibens adnotationum criticarum in loco quaedam librorum sacrorum novi foederis in Ti. Hemsterhusii orationes, quarum prima est de Paulo apostolo. L.C. Valckenari tres orationes, quibus subiectum est schediasma, specimen exhibens adnotationum criticarum in loco quaedam librorum sacrorum Novi Foederis. Praefiguntur duae orationes Ioannis Chrysostomi in laudem Pauli apostoli, cum veteri versione Latina Aniani, ex cod. MS. hic illic emendata, 324–414. Leiden: Luchtmans & Honkoop, 1784.Search in Google Scholar

van Altena, Vincent, Bakker, Henk, and Stoter, Jantien. “Advancing New Testament Interpretation through Spatio-Temporal Analysis: Demonstrated by Case Studies.” Transactions in GIS 22:3 (2018), 697–720. 10.1111/tgis.12338Search in Google Scholar

van Altena, Vincent, Krans, Jan, Bakker, Henk, Dukai, Balász, and Stoter, Jantien. “Spatial Analyis of New Testament Textual Emendations Utilizing Confusion Distances.” Open Theology 5:1 (2019), 44–65.10.1515/opth-2019-0004Search in Google Scholar

van de Sande Bakhuyzen, Willem Hendrik. Over de toepassing van de conjecturaal-kritiek op den tekst des Nieuwen Testaments. Verhandelingen, raakende den natuurlyken en geopenbaarden godsdienst, nieuwe serie 9.2. Haarlem: Bohn, 1880.Search in Google Scholar

van Houwelingen, P. H. R. Apostelen: dragers van een spraakmakend evangelie. Commentaar op het Nieuwe Testament. Derde serie, Afdeling Handelingen en Apostelen. Kampen: Kok, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

van Manen Christiaan, Willem. Conjecturaal-kritiek toegepast op den tekst van de Schriften des Nieuwen Testaments. Verhandelingen, raakende den natuurlyken en geopenbaarden godsdienst, nieuwe serie 9.1. Haarlem: Bohn, 1880.Search in Google Scholar

Verschuir, Johannes Hendrik. In Opuscula in quibus de variis S. Literarum locis, et argumentis exinde desumtis, critice et libere disseritur, edited by Johannes Anthonie Lotze. Utrecht: Wild & Altheer, 1810.Search in Google Scholar

von Dobschütz, Ernst. “Zu der Völkerliste Act. 2, 9–11.” Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Theologie 45 (1902), 407–10.Search in Google Scholar

Weinstock, Stefan. “The Geographical Catalogue in Acts II, 9–11.” Journal of Roman Studies 38 (1948), 43–6.10.2307/298169Search in Google Scholar

Wellhausen, Julius. Kritische Analyse der Apostelgeschichte. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Philologisch-Historische Klasse, N.F. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1914.Search in Google Scholar

Wendt, Hans Hinrich. Kritisch exegetisches Handbuch über die Apostelgeschichte, 5th ed. Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar über das Neue Testament (Meyer-Kommentar) 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1880.Search in Google Scholar

Whiston, William. The Sacred History from the Beginning of the World ’till the Days of Constantine; Part the Second. Or, the Times of the New Testament. Containing, a General Ecclesiastical History, from the Nativity of Our Blessed Saviour, to the First Establishment of Christianity by Human Laws, under the Emperor Constantine the Great. Including the Interval of 317 Years, vol. V. London: [s.n.], 1746.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Charles Stephen Conway. A Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles. Black s New Testament Commentaries. London: Black, 1957.Search in Google Scholar

Witherington, Ben. The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, Paternoster, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, Johann Christoph. Curae philologicae et criticae in IV. SS. Evangelia et Actus apostolicos, quibus integritati contextus Graeci consulitur, sensus verborum ex praesidiis philolog. illustratur, diversae interpretum sententiae summatim enarrantur, et modesto examini subiectae vel approbantur vel repelluntur. Hamburg: Kisner, 1725.Search in Google Scholar

Zahn, Theodor. Einleitung in das Neue Testament. Erster Band, vol. 1. Leipzig: Deichert, 1897.10.1515/9783111551128-001Search in Google Scholar

Zahn, Theodor. Die Urausgabe der Apostelgeschichte des Lucas. Forschungen zur Geschichte des neutestamentlichen Kanons und der altkirchlichen Literatur 9. Leipzig: Deichert, 1916.Search in Google Scholar

Zahn, Theodor. Die Apostelgeschichte des Lucas. Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 5.1. Leipzig: Deichert, 1919.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Vincent van Altena et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Topical Issue: Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World, edited by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle and Sarah Nicholson

- Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World: Editorial Introduction

- A Nameless Bride of Death: Jephthah’s Daughter in American Jewish Women’s Poetry

- Social Justice and Gender

- Bereaved Mothers and Masculine Queens: The Political Use of Maternal Grief in 1–2 Kings

- Gendering Sarai: Reading Beyond Cisnormativity in Genesis 11:29–12:20 and 20:1–18

- Thinking Outside the Panel: Rewriting Rebekah in R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis

- What is in a Name? Rahab, the Canaanite, and the Rhetoric of Liberation in the Hebrew Bible

- Junia – A Woman Lost in Translation: The Name IOYNIAN in Romans 16:7 and its History of Interpretation

- Topical issue: Issues and Approaches in Contemporary Theological Thinking about Evil, edited by John Culp

- Introduction for the Topical Issue “Issues and Approaches in Contemporary Theological Thinking about Evil”

- Oh, Sufferah Children of Jah: Unpacking the Rastafarian Rejection of Traditional Theodicies

- Why the Hardship? Islam, Christianity, and Instrumental Affliction

- Can God Promise Us a New Past? A Response to Lebens and Goldschmidt

- Hyper-Past Evils: A Reply to Bogdan V. Faul

- A Theodicy of Kenosis: Eleonore Stump and the Fall of Jericho

- Getting off the Omnibus: Rejecting Free Will and Soul-Making Responses to the Problem of Evil

- On Quentin Meillassoux and the Problem of Evil

- Befriending Job: Theodicy Amid the Ashes

- Evil, Prayer and Transformation

- Rethinking Disaster Theology: Combining Protestant Theology with Local Knowledge and Modern Science in Disaster Response

- Topical issue: Motherhood(s) in Religions: The Religionification of Motherhood and Mothers’ Appropriation of Religion, edited by Giulia Pedrucci

- The Entanglement of Mothers and Religions: An Introduction

- Kourotrophia and “Mothering” Figures: Conceiving and Raising an Infant as a Collective Process in the Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Worlds. Some Religious Evidences in Narratives and Art

- Pregnancy, Birthing, Breastfeeding and Mothering: Hindu Perspectives from Scriptures and Practices

- “Like a Mother Her Only Child”: Mothering in the Pāli Canon

- Mothers of a Nation: How Motherhood and Religion Intermingle in the Hebrew Bible

- Milk Kinship and the Maternal Body in Shi’a Islam

- Back Home and Back to Nature? Natural Parenting and Religion in Francophone Contexts

- Topical issue: Phenomenology of Religious Experience IV: Religious Experience and Description, edited by Olga Louchakova-Schwartz, James Nelson and Aaron Preston

- Religious Experience and Description: Introduction to the Topical Issue

- Being and Time-less Faith: Juxtaposing Heideggerian Anxiety and Religious Experience

- Some Moments of Wonder Emergent within Transcendental Phenomenological Analyses

- The Fruits of the Unseen: A Jamesian Challenge to Explanatory Reductionism in Accounts of Religious Experience

- Reading in Phenomenology: Heidegger’s Approach to Religious Experience in St. Paul and St. Augustine

- Noetic and Noematic Dimensions of Religious Experience

- Religious Experience, Pragmatic Encroachment, and Justified Belief in God

- On Music, Order, and Memory: Investigating Augustine’s Descriptive Method in the Confessions

- Experiencing Grace: A Thematic Network Analysis of Person-Level Narratives

- Senseless Pain in the Phenomenology of Religious Experience

- The Invisible and the Hidden within the Phenomenological Situation of Appearing

- The Phenomenal Aspects of Irony according to Søren Kierkegaard

- To Hear the Sound of One’s Own Birth: Michel Henry on Religious Experience

- Is There Such a Thing as “Religion”? In Search of the Roots of Spirituality

- Transliminality: Comparing Mystical and Psychotic Experiences on Psycho-Phenomenological Grounds

- Regular Articles

- Being and Becoming a Monk on Mount Athos: An Ontological Approach to Relational Monastic Personhood in the “Garden of the Virgin Mary” as a Rite of Passage

- Stylizations of Being: Attention as an Existential Hub in Heidegger and Christian Mysticism

- Quantum Entanglements and the Lutheran Dispersal of Salvation

- On Caputo’s Heidegger: A Prolegomenon of Transgressions to a Religion without Religion

- Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9: a Diachronic Overview of its Conjectured Emendations

- Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9: Reverse Engineering Textual Emendations

- Women’s Nature in the Qur’an: Hermeneutical Considerations on Traditional and Modern Exegeses

- The Problem of Arbitrary Creation for Impassibility

- Morality politics: Drug use and the Catholic Church in the Philippines

- Distant Reading of the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of John: Reflection of Methodological Aspects of the Use of Digital Technologies in the Research of Biblical Texts

- Greek Gospels and Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls: Compositional, Conceptual, and Cultural Intersections

- Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza and the Quest for the Historical Jesus

- Between the Times – and Sometimes Beyond: An Essay in Dialectical Theology and its Critique of Religion and “Religion”

- The Social Sciences, Pastoral Theology, and Pastoral Work: Understanding the Underutilization of Sociology in Catholic Pastoral Ministry

Articles in the same Issue

- Topical Issue: Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World, edited by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle and Sarah Nicholson

- Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World: Editorial Introduction

- A Nameless Bride of Death: Jephthah’s Daughter in American Jewish Women’s Poetry

- Social Justice and Gender

- Bereaved Mothers and Masculine Queens: The Political Use of Maternal Grief in 1–2 Kings

- Gendering Sarai: Reading Beyond Cisnormativity in Genesis 11:29–12:20 and 20:1–18

- Thinking Outside the Panel: Rewriting Rebekah in R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis

- What is in a Name? Rahab, the Canaanite, and the Rhetoric of Liberation in the Hebrew Bible

- Junia – A Woman Lost in Translation: The Name IOYNIAN in Romans 16:7 and its History of Interpretation

- Topical issue: Issues and Approaches in Contemporary Theological Thinking about Evil, edited by John Culp

- Introduction for the Topical Issue “Issues and Approaches in Contemporary Theological Thinking about Evil”

- Oh, Sufferah Children of Jah: Unpacking the Rastafarian Rejection of Traditional Theodicies

- Why the Hardship? Islam, Christianity, and Instrumental Affliction

- Can God Promise Us a New Past? A Response to Lebens and Goldschmidt

- Hyper-Past Evils: A Reply to Bogdan V. Faul

- A Theodicy of Kenosis: Eleonore Stump and the Fall of Jericho

- Getting off the Omnibus: Rejecting Free Will and Soul-Making Responses to the Problem of Evil

- On Quentin Meillassoux and the Problem of Evil

- Befriending Job: Theodicy Amid the Ashes

- Evil, Prayer and Transformation

- Rethinking Disaster Theology: Combining Protestant Theology with Local Knowledge and Modern Science in Disaster Response

- Topical issue: Motherhood(s) in Religions: The Religionification of Motherhood and Mothers’ Appropriation of Religion, edited by Giulia Pedrucci

- The Entanglement of Mothers and Religions: An Introduction

- Kourotrophia and “Mothering” Figures: Conceiving and Raising an Infant as a Collective Process in the Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Worlds. Some Religious Evidences in Narratives and Art

- Pregnancy, Birthing, Breastfeeding and Mothering: Hindu Perspectives from Scriptures and Practices

- “Like a Mother Her Only Child”: Mothering in the Pāli Canon

- Mothers of a Nation: How Motherhood and Religion Intermingle in the Hebrew Bible

- Milk Kinship and the Maternal Body in Shi’a Islam

- Back Home and Back to Nature? Natural Parenting and Religion in Francophone Contexts

- Topical issue: Phenomenology of Religious Experience IV: Religious Experience and Description, edited by Olga Louchakova-Schwartz, James Nelson and Aaron Preston

- Religious Experience and Description: Introduction to the Topical Issue

- Being and Time-less Faith: Juxtaposing Heideggerian Anxiety and Religious Experience

- Some Moments of Wonder Emergent within Transcendental Phenomenological Analyses

- The Fruits of the Unseen: A Jamesian Challenge to Explanatory Reductionism in Accounts of Religious Experience

- Reading in Phenomenology: Heidegger’s Approach to Religious Experience in St. Paul and St. Augustine

- Noetic and Noematic Dimensions of Religious Experience

- Religious Experience, Pragmatic Encroachment, and Justified Belief in God

- On Music, Order, and Memory: Investigating Augustine’s Descriptive Method in the Confessions

- Experiencing Grace: A Thematic Network Analysis of Person-Level Narratives

- Senseless Pain in the Phenomenology of Religious Experience

- The Invisible and the Hidden within the Phenomenological Situation of Appearing

- The Phenomenal Aspects of Irony according to Søren Kierkegaard

- To Hear the Sound of One’s Own Birth: Michel Henry on Religious Experience

- Is There Such a Thing as “Religion”? In Search of the Roots of Spirituality

- Transliminality: Comparing Mystical and Psychotic Experiences on Psycho-Phenomenological Grounds

- Regular Articles

- Being and Becoming a Monk on Mount Athos: An Ontological Approach to Relational Monastic Personhood in the “Garden of the Virgin Mary” as a Rite of Passage

- Stylizations of Being: Attention as an Existential Hub in Heidegger and Christian Mysticism

- Quantum Entanglements and the Lutheran Dispersal of Salvation

- On Caputo’s Heidegger: A Prolegomenon of Transgressions to a Religion without Religion

- Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9: a Diachronic Overview of its Conjectured Emendations

- Ἰουδαίαν in Acts 2:9: Reverse Engineering Textual Emendations

- Women’s Nature in the Qur’an: Hermeneutical Considerations on Traditional and Modern Exegeses

- The Problem of Arbitrary Creation for Impassibility

- Morality politics: Drug use and the Catholic Church in the Philippines

- Distant Reading of the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of John: Reflection of Methodological Aspects of the Use of Digital Technologies in the Research of Biblical Texts

- Greek Gospels and Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls: Compositional, Conceptual, and Cultural Intersections

- Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza and the Quest for the Historical Jesus

- Between the Times – and Sometimes Beyond: An Essay in Dialectical Theology and its Critique of Religion and “Religion”

- The Social Sciences, Pastoral Theology, and Pastoral Work: Understanding the Underutilization of Sociology in Catholic Pastoral Ministry