Abstract

With the large-scale application of computational propaganda, disinformation campaigns have emerged globally in response to the logic of “post-truth” politics. Organized disinformation campaigns operate frequently on overseas social media platforms, with China often being the target. In order to understand the dissemination mechanisms of such disinformation campaigns, the study found that the dissemination of disinformation became a key strategy for the campaign’s emotional mobilization. The main subjects of disinformation have formed an international communication matrix, creating and spreading all kinds of disinformation on a large scale. The “coalition of protesters” is based on the shared emotional experience evoked by disinformation and characterized by the act of spreading disinformation. Then, the widespread dissemination of the corresponding emotions leads to different perceptions of the “target,” thus prompting protesters to adopt different types of collective action. This mechanism of emotional mobilization shows that facts are “too big to know,” which exacerbates confirmation bias and provides more space for the spread of disinformation. The strong emotions embedded in disinformation contributed to the completion of the protesters’ imagination of community, and emotions became the dominant factor in coalescing the group and providing motivational support for collective action.

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of various social media platforms, disinformation is spreading on an increasingly large scale and has produced a wide range of social, political and economic impacts. In particular, in various types of social movements, groundless or seriously distorted political news, using rumors and slanders as the major means, and attacking politicians, national policies, and political opinions as the fundamental goal, have caused social cognitive confusion and group confrontation, or even directly led to social unrest. In recent years, organized disinformation campaigns have frequently occurred on overseas social platforms, often with China as the target. Bolsover and Howard (2019), two academics at the University of Oxford, found that there is no automated posting of China-related political information on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform. In contrast, a lot of anti-China information posted on Twitter in simplified Chinese has seen automated dissemination. In this context, it is of great importance to study the communication mechanism of international China-related disinformation campaigns, so as to prevent and deal with the attacks of disinformation campaigns scientifically and improve international communication.

In 2019, Hong Kong was caught in turbulence over Anti-extradition Law Protests. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government’s amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance was aimed at fixing “legal flaws and loopholes.” The procedure was legal and steady, but it met with continuous protests and even led to clashes between the police and the public, arousing worldwide concern. In this campaign, the wide spread of disinformation became the focus of public opinion. By carefully selecting hot events and seizing the “pain points” of the public, protesters created disinformation, triggered large-scale social media sharing, and then created hot topics. It was reported that the widespread disinformation in the turbulence became a tool of psychological warfare (Banjo and Lung 2019; Lew 2019). Furthermore, disinformation also catalyzed mass gatherings that continue to set the agenda for protests. For example, in the Prince Edward Station Incident, several people were reportedly beaten to death by the police. As a result, many large-scale actions of solidarity and mourning erupted. Even one year after the incident, when the truth had long been revealed, many people still gathered at the station to offer flowers, and related commemorative activities were also found in many other countries and regions. Behind these activities stand the institutions from countries or regions such as the United States, Britain and Taiwan, and the goal is to advance Hong Kong-related policy interests in their countries or regions. In this situation, the Anti-extradition Law Protests can serve as a typical case for in-depth investigation of the communication mechanism of the international China-related disinformation movement, and the emotional transmission and mobilization mechanism formed by disinformation has also become the key to understanding the mobilization mechanism in the protests.

2 Literature review

Disinformation is related to, but different from, concepts including fake news and rumor. In academic terms, disinformation refers to information that is deliberately fabricated to deceive and mislead others, while misinformation means inaccurate information spread through negligence and unconscious bias (Tandoc 2019). Under this definition, false rumors are generally classified as misinformation, while organized propaganda is considered to be disinformation. In other words, disinformation is invented to manipulate and confuse people, while misinformation is misleading information without clear manipulation or malicious intent. Fake news is usually regarded as fictitious information that imitates the form of the news media (Lazer et al. 2018). However, the term “fake news” is also used by politicians to discredit the critical reports of some news organizations (Ross and Rivers 2018), so that its connotation has become ambiguous (Tandoc et al. 2018). In general, factuality and intentionality are the two dimensions frequently used for the concepts of misinformation, disinformation, and fake news. However, there are problems with this approach to defining concepts. Some studies pointed out that we are in a “hybrid news system” with an extremely diverse and complex communicator environment and multiple media roles. Circulation of misinformation/disinformation is through the interaction of various actors with different intentions and biases. It has become an “information chain” with a mixed and complex nature, rather than an entity with static properties (Giglietto et al. 2019). Therefore, on the one hand, it is difficult for us to clearly distinguish the true intentions of the initial communicators, and it is also difficult to determine whether a piece of spreading information fits into a single category of misinformation or disinformation. In this study, the research object includes both misinformation and disinformation, i.e., information that has a clear intention of manipulation or is unconsciously circulated but is essentially lacking in factual basis or misrepresented to deceive and mislead people.

“Mobilization” has the connotation of deploying resources for a specific purpose. Durkheim introduced mobilization into sociological research and believed that collective emotions play a role in social integration (Durkheim 2013). In modern sociology before the 1980s, the study of emotions has long been secondary; emotions were either ignored or considered irrational in the study of collective action and social movements. An example is the theory of resource mobilization based on the assumption of rational actors. But with the emergence and influence of cultural analysis and the sociology of emotions, emotions have re-entered the study of social movements (Yang and Pace 2016). Emotions have strong social properties and emerge through social interactions in a certain social environment. Emotions are not only tools and resources, but also motivators of struggle (Yang 2009). Moreover, compared with traditional political mobilization, the mobilization process relying on the Internet is more dependent on the emotional power of culture and discourse. Especially in the context of social media, the absence of the body makes struggles and protests more dependent on the connection between discourse, opinions and emotions. Therefore, studies on online collective action have emphasized the role of emotional mobilization of culture, discourse, symbols and images (Yang 2013). For example, Yang (2009) studied the two emotional mobilization styles of tragedy and ridicule in online events; Guo studied the evolution mechanism of emotional mobilization and struggling repertoires of scene construction, identity construction and public opinion trial in online rumors (Guo 2013; Guo and Yan 2014).

Disinformation has the effect of emotional mobilization in collective action, and it is often used as a discourse strategy for communication, which helps to achieve certain emotional appeals, and then affects the behavior of the audience (Bennett and Livingston 2018; Scheufele and Krause 2019). Related research can be traced back to Allport’s research on rumors. He believed that “rumors are the projection of an altogether subjective emotional condition,” and pointed out that rumors usually have three common purposes: exaggerating harm to create fear, creating hatred and sense of tearing and providing hope (Allport and Postman 1947).

However, studies on disinformation and emotional mobilization have become a new hot topic in recent years. Overall, related research focuses on the following aspects:

How disinformation stimulates different emotional responses through different narrative strategies. For example, Polletta and Callahan argue that the elite media narratives in the United States use existing historical memory and personal experience to effectively establish a collective identity and sense of identification, and form a solid “echo chamber” by constant retelling and quotation of the right-wing media (Polletta and Callahan 2017). Mourao and Robertson found that “fake news” sites during the U.S. elections tended to use disinformation, partisanship, sensationalism to deliver anti-establishment narratives, and that fake news were more correlated with partisanship and political identity (Mourão and Robinson 2019).

How disinformation constructs or attacks the image of the opponent to arouse negative emotions of the target readers. For example, some studies found that during the 2004 U.S. election, political activists and interest groups formed information clusters through links between blogs and partisan websites, deliberately using disinformation to damage the credibility and public image of political opponents (Rojecki and Meraz 2016).

How different emotions affect people’s self-belief and cognitive attribution. For example, some studies found that perceptions of reality caused by exposure to fake news have a mediating effect in political inefficacy (feelings of inability to understand and participate effectively in politics), alienation (feelings of inability to influence and control public policy), or cynicism (expressing disapproval of government through cynicism) (Balmas 2014).

On this basis, some studies found that different emotional and cognitive attributions can affect the collective to take different actions. For example, some studies of Chinese online communities suggested that fear-inducing news can enhance member participation in personalized meaning construction, moral evaluation, mobilization, and cohesion maintenance (Zou 2020). Other studies suggested that hostile negative information (Pinazo-Calatayud et al. 2020), anger, and political satire that arouses negative emotions towards the power body (Chen et al. 2017; Lee and Kwak 2014) can all intensify political participation. However, the action relationships corresponding to different emotions in different situations are not so simple, and factors such as media environment and psycho-social basis also have complex mechanisms of action. For example, Schuck and de Vreese (2012) found that positive news framing in support of EU integration have the reverse mobilization effect of stimulating skeptics to vote, which indicates the dual effect of risk perception and high self-efficacy.

To sum up, the communication effects of disinformation have been extensively studied and rich findings have been generated. Some studies summarized the circulation patterns of disinformation in the new communication environment and explored the diverse effects of disinformation on the emotions of target audiences. It is noteworthy that disinformation is deeply influenced by the political structure and is a reflection of people’s deep emotions, and it also counteracts social movements and makes them more polarized and radicalized. And in a polarized and low-trust environment, emotional, scandalous and conflict-oriented contents tend to circulate more widely (Bennett and Livingston 2018; Umbricht and Esser 2016). And in this process, questions remain to be explored in depth as to how disinformation becomes a narrative strategy that produces different affective frames and thus influences collective action.

3 Research design

A review of scholarly literature shows that the subject and theme of disinformation are the two core elements that are most closely related to the emotions embedded in it. On this basis, to analyze disinformation’s emotional mobilization effect, it is necessary to start from two dimensions: online and offline. Therefore, with the aim of analyzing how emotions are transmitted through the disinformation during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong, and further exploring the mechanism of emotion-based disinformation in social movements, this paper poses the following questions:

Who spread disinformation in the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong?

Who are the subjects of the disinformation during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong? That is, who are the subjects this disinformation attempts to promote or attack?

What are the main themes constructed by this disinformation? What types of emotions are transmitted through these different types of themes?

Concerning online data, what is the relationship between the types of emotions conveyed by this disinformation and the communication effect of these disinformation?

Concerning offline protests, what is the relationship between the types of emotions conveyed by this disinformation and the types of actions taken by the protest subjects?

3.1 Data collection

One main feature of the incident is its international reach, with protesters using a wide range of social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Telegram, Instagram, and LIHKG for the purpose of social mobilization. Gaining support from international organizations and foreign dignitaries became an aim for the protesters and a tool for them to prove the legitimacy of their movement and deepen their social mobilization. Preparatory research revealed that Twitter was the main public platform for international propaganda and social mobilization in Hong Kong Anti-extradition Law Protests worldwide. Therefore, we chose the data of Twitter as the object of our study. However, it is necessary to note that multi-platform coordination is a typical strategy for disinformation dissemination. Fact-checking used in this paper targets not only Twitter, but the same disinformation jointly disseminated by multiple platforms. Therefore, the selection of Twitter data is not intended to underestimate the influence of other platforms. The specific steps are as follows.

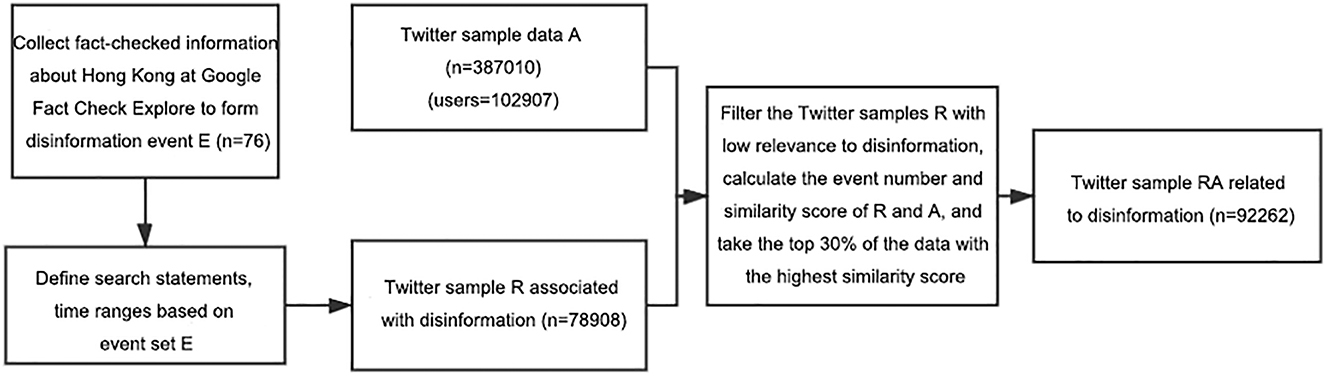

First, taking “‘香港’ OR ‘Hong Kong’ OR ‘HK’” as the keyword, we used the crawler to obtain the original tweets with more than one retweets, likes, and comments respectively on Twitter between January 1, 2019 and January 31, 2020 as data sample A (a total of 387,010 tweets and 102,907 accounts). Then, we retrieved fact-checked information about Hong Kong through Google Fact Check Explore (a collaborative project between Google and Duke University, the largest fact-checking tool in the world), and obtained a total of 76 pieces of fact-checked information excluding those unrelated to Hong Kong Anti-extradition Law Protests, to obtain the verified disinformation event set E. After that, based on the fact-checked information in the disinformation event set E, we traced the content of the original disinformation text, and defined keywords and Twitter search statements (including traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese and English) for each disinformation. A time series autocorrelation analysis was conducted on data sample A, and the results showed that the autocorrelation impact of topics at a certain point was about “the following 7 days.” Therefore, for data completeness, this study retrieved information posted 3 days before and 7 days after the release time of the original disinformation, and obtained the disinformation-related tweet data sample R (a total of 78,908 tweets).

Second, keyword data of the disinformation event set E was used to test the similarity between the tweet data sample A and the disinformation-related sample R based on word embedding, so that each tweet data (from R + A) corresponds to a disinformation event number (from E), and samples with low similarity scores were removed.

Third, the top 30 % of the aggregated disinformation events with the highest similarity scores (excluding samples with low content relevance) were selected as a larger disinformation-related data set RA (92,262 items) with an average similarity of 0.74. The data sample RA was the main research object (as shown in Figure 1).

Data collection process.

3.2 Content analysis

According to the disinformation event set E (n = 76), disinformation in the set is characterized by cross-platform dissemination and high engagement. For example, a head CT scan of a person claimed to have been beaten and injured by the police was widely spread on multiple social platforms. The event set also contains a large number of events that are directly related to the protests and have a sustained impact, such as the “831 Prince Edward Station Incident,” which was used by protesters as an excuse to organize several large-scale rallies. The content subjects of the disinformation were manually coded into seven categories, and the emotional polarity they triggered were divided into positive and negative. In order to classify the offline movements during the Hong Kong Anti-extradition Law Protests period, this study collected information from the Wikipedia list of Hong Kong Anti-extradition Law Protests, the South China Morning Post (Robles 2020), and other media as the main sources. The timeline of the movements from June 1 to December 31, 2019, with the time, location, and form of each movement, was used to classify the daily concerted actions into four types (as shown in Table 1).

In addition, the study further screened the event samples for theme coding and emotion analysis of disinformation from the protesters’ camp based on the content subject and emotional polarity of the disinformation event set (as shown in Table 1). Two coders independently coded the above items, and Cronbach’s alpha coder reliability is shown in Table 2.

Coding sheet.

| Category | Coding | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Disinformation content subjects | HKP | Hong Kong police |

| PROTESTER | Hong Kong protesters | |

| GOC | The government of China | |

| HKSAR | Hong Kong SAR Government | |

| PEC | HK Pro-establishment camp | |

| PDC | HK Pro-democracy camp | |

| CE | Chinese-funded enterprise | |

| Emotional polarity | Positive | Positive |

| Negative | Negative | |

| Types of actions | Concentrated violence (CV) | A concentrated outbreak of violent actions in one or two places, and participants such as protesters or police use force. The violent actions concentrated in Wanchai District and Central and Western District happened on June 9, June 12, and July 1 are examples. |

| Decentralized violence (DV) | Violence erupts simultaneously in multiple places and districts within a day, such as violent actions occurred in Sai Kung District, Central and Western District, Yau Tsim Mong District, Wong Tai Sin District, Yuen Long District, Sha Tin District and other places on August 4. | |

| Peaceful march (PM) | Smaller peaceful marches, non-violent. | |

| Mass rally (MR) | Large peaceful gatherings with documented numbers, non-violent, such as the August 18 rally in Victoria Park and other places (protesters claimed 1.7 million people participated, while police estimated there were 128,000 people). | |

| Types of themes | Alliances building (AB) | Fictitious alliances, fictitious characters or actions supporting the protesters |

| Blame shifting (BS) | Minimize and deny violence, shift responsibility | |

| Sad victim (SV) | Constructing the image of the tragic victims of the protesters | |

| Local identity (LI) | Create local identities for protesters | |

| Personal image attacking (PIA) | Attacks on personal image, personal attacks | |

| White terror (WT) | Fictionalize extreme government measures and exaggerate white terror | |

| Police brutality (PB) | Defamation of police’s lawlessness and abuse of violence |

Coder reliability.

| Variable | Cronbach’s alpha | n |

|---|---|---|

| Content subject | 0.956 | 76 |

| Emotional polarity | 0.917 | 76 |

| Types of actions | 0.977 | 110 |

| Types of themes | 0.854 | 41 |

All variables had high reliability due to the distinct features. Finally, based on word embedding similarity calculation between the disinformation event set E and the Twitter sample, the above items also became attributes of the Twitter sample RA.

3.3 Emotion analysis

To study the differences in emotional types evoked by disinformation, this study adopted a text emotion analysis method based on an emotion dictionary. The NRC Emotion Lexicon, created by the National Research Council Canada, is an authoritative emotion lexicon commonly used by the international academic community. It provides eight basic emotions: anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust, as well as two emotional polarities: negative and positive (Mohammad and Turney 2010, 2013). The NRC Emotion Lexicon is mainly in English, but a Chinese translation is also available, which was used for emotion analysis of Chinese texts, with manual adjustment for individual translation deviations to improve the accuracy of the lexicon. The above processed NRC Emotion Lexicon was used to calculate the word frequency of each emotion type in the English and Chinese texts of the data sample RA, and the proportion of the word frequency of each emotion type in each text was taken as its score.

3.4 Time series analysis

In this study, time series analysis was adopted to explore the mechanism of emotional mobilization of disinformation. For the correlation analysis, the Spearman correlation coefficient between the time series of the variables was calculated as the basis of correlation. For the causality analysis, the nonlinear causal network analysis method PCMCI (Runge et al. 2019a, 2019b) was mainly adopted to calculate the causal relationships within n-period lags of multiple time series with each other (n is the maximum number of lags) and construct a two-way causal network to explain the complex interactions among the variables.

In terms of data processing methods for the samples, this study mainly calculates two types of time series data: (1) time series data of communication effects, obtained by mean aggregation of communication effect indicators (retweets, comments, likes) for each tweet data in each day and hour; and (2) time series data of emotion change, obtained by mean aggregation of different emotion types’ scores of each tweet in each day and hour.

In addition, considering the rigor and efficiency of data analysis, some methods and parameters need to be adjusted: (1) Narrow the time granularity. For example, the smallest time granularity for protest action is “day,” while that for emotion and communication effect is “hour”; (2) Select the maximum lag time. The maximum number of lags is 7 when the data is in “days” and 24 when it is in “hours”; (3) Residualization. Before causality analysis, it is necessary to calculate residual series of time series data (eliminate the influence of cycle and trend based on the X-11 model and STL model), to avoid the problem of “false regression” and improve the explanative power of causality (Cai 2009; Wang 2008); and (4) The significance indexes are taken as less than 0.05.

4 Research findings

4.1 Polarized camps: analysis of the content subjects of disinformation during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong

The content subjects of disinformation include: Hong Kong protesters (PROTESTER, 47.37 %), Hong Kong police (HKP, 23.68 %), the central government of China (GOC, 11.84 %), HK Pro-establishment camp (PEC, 9.21 %), Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government (HKSAR, 6.58 %), Chinese-funded enterprise (CE, 1.32 %). In general, protesters and Hong Kong police are the major content subjects of disinformation, showing a clear trend of polarization. It is not surprising that protesters are one of the subjects of disinformation, considering the subjects of any social movement will disseminate various messages to construct their images. In terms of the specific demands of the protest against the extradition bill campaign, the protesters mainly targeted at the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government and the central government of China. However, in the disinformation, Hong Kong police, rather than the above-mentioned two governments, become the main target of attacks. The police-versus-civilians not only creates a stronger visual effect of confrontation, but also provides more sufficient narrative tension in terms of connotation.

4.2 Constructing an emotional community: analysis of narrative theme types of disinformation during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong

By manually summarizing the themes of the 76 pieces of fact-checked information, we found that this disinformation can be grouped into seven types (the specific analysis process is shown in Table 1: Types of themes). In terms of the distribution of theme types, “white terror” (31.38 %) is the most prevalent theme, followed by “personal image attacking” (23.03 %), “police brutality” (22.12 %), and then “sad victim” (13.71 %), “alliances building” (7.18 %), “blame shifting” (2.44 %), and lastly “local identity” (0.14 %).

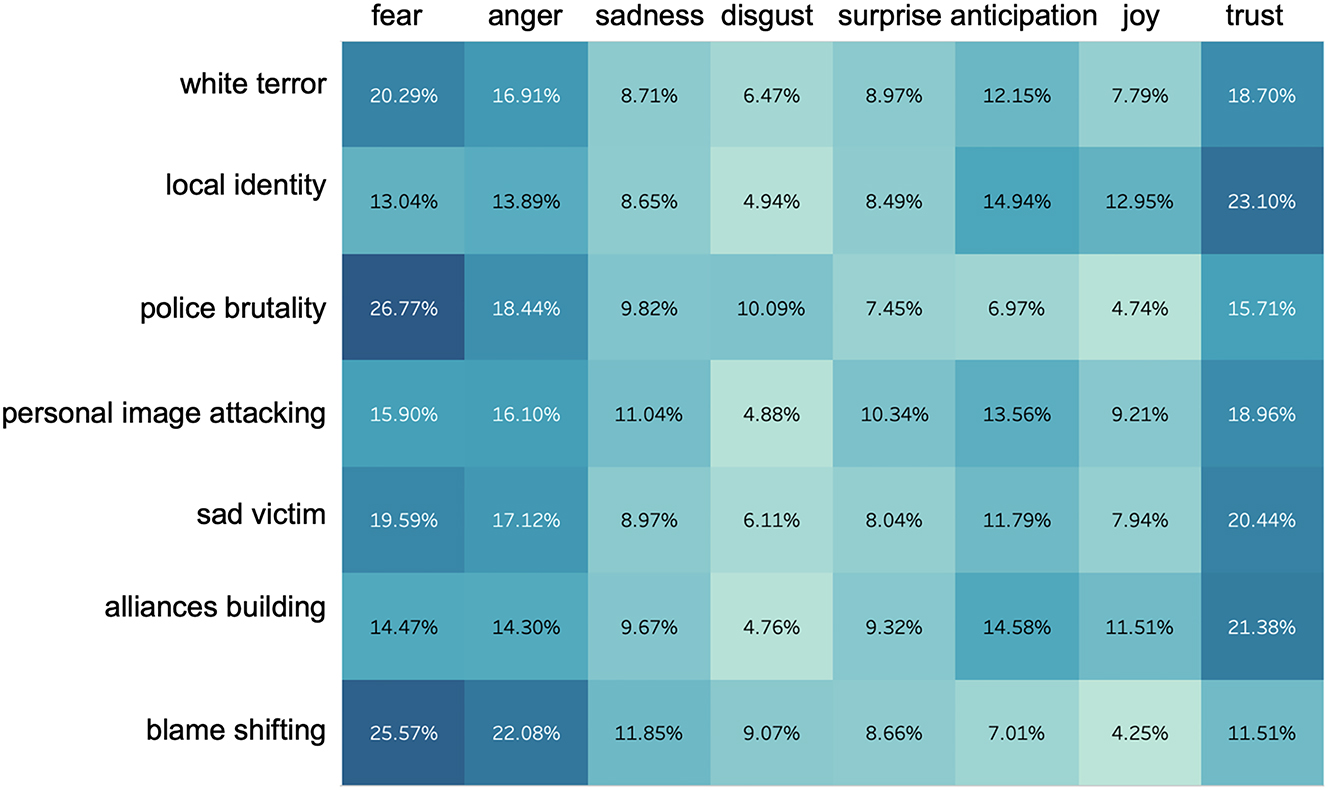

As shown in Figure 2, there are differences in the types of emotions embedded in the different theme types. For example, “white terror” and “police brutality” highlight the emotions of fear and anger. The percentage of fear in “white terror” is as high as 20.29 % and the percentage of anger is 16.91 %, while the percentage of fear in “police brutality” is the highest at 26.77 % and the percentage of anger is 18.44 %. This narrative theme, dominated by fear and anger, visualizes the “external enemy” of the protesting group, and allows the protesters to rationalize and legitimize their actions and maintain the momentum of the group’s common action.

Narrative themes of disinformation and the distribution of embedded emotion types.

In comparison, the themes of “alliance building” and “local identity” both have a high percentage of positive emotions. In addition, “sad victim” also has a high percentage of trust, which accounts for 20.44 %. The positive emotions of trust, expectation and pleasure are prominent in the narrative themes to strengthen the group’s sense of identity and belonging by shaping the identity of the protesters and constructing collective memory. The theme of “sad victim” is to construct the collective memory of the protest movement, and to continue and strengthen the emotional ties of the protesters’ group through commemorative discourses and rituals. It can be seen that the protesters have gained a collective emotional experience through the widespread dissemination of this emotion and have formed a community of emotions through group representations such as retweets, comments and likes. This form of emotion-centered community is a new evolutionary trend of the “imagined community” based on social media platforms, as social media provide the possibility for the instantaneous transmission of emotions across regions, groups and cultures. It is in this sense that Michel Maffesoli has developed the concept of affectual tribes (Maffesoli and Foulkes 1988), which have become a metaphor for the emotional community that not only forms the social basis of post-modernity, but also contributes to the creation of a zeitgeist (Xu and Petit 2014). The emotional community that the protesters tried to construct is an “affectual tribe” that is linked by collective emotional experience and characterized by communication behavior on social media platforms. With the widespread dissemination of this emotion and the expansion of the community, the protesters perceived that the group is supported by the external society and that their behavior is in line with the social expectations, thus gaining a sense of empowerment and thus reshaping their selves. Therefore, these themes played an important role in enhancing the internal cohesion of the protesting groups and increasing their sense of participation.

4.3 Expanding the “imaged alliance”: a correlation between the type of emotion embedded in disinformation and the effect of online communication

For social movements, in addition to strengthening identity and forming an emotional community within the protesters, it is also necessary to find potential sympathizers and supporters in the international arena to further expand “alliances.” In the case of Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong, disinformation also plays an important role in this regard. This information is a projection of people’s political tendencies and deep-seated desires as well as a reflection of their emotional purposes (Allport and Postman 1947). Interactive behaviors such as liking, commenting and retweeting can not only quickly promote the relevant information, but also in effect form and develop an “alliance” of protesters based on such communication behaviors. Thus, the evaluation of the data on these communication behaviors becomes an important way to analyze the mobilization of protesters by setting different emotional frames for different subjects. To do so, we first analyzed the subjects in the disinformation network.

Based on the sample R of Twitter data related to disinformation (a total of 78,908 tweets), we statistically analyzed the relevant subjects involved in the dissemination of disinformation. By summing up the three types of data of retweets, comments and likes, we ranked these accounts (see Table 3: Head accounts of disinformation dissemination. In the interest of saving space, only the top 20 accounts were selected). From these influential accounts, it can be seen that the accounts involved in spreading disinformation about the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong are relatively diverse, including Hong Kong media platforms, organizations and individuals, as well as international mainstream media, political figures, NGOs, and some social activists. According to the data, tweets published by these head accounts were also transmitted widely. This shows that during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong, the disinformation “captured” many international mainstream media, famous politicians and KOLs, forming an international communication matrix, and thus creating a larger communication effect and forming an international “alliance.” This internationalization of mobilization has a special significance in the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong. In the protesters’ view, the international community’s stance and support can, on the one hand, provide proof of the movement’s legitimacy, and on the other hand, provide an opportunity to mobilize public opinion in Western countries and motivate anti-Chinese politicians to push for the introduction of relevant Hong Kong-related bills, which is the reason why the opposition attaches great importance to Twitter and actively promotes international propaganda through the platform although Twitter is not as popular as Facebook in Hong Kong.

Head accounts who spread disinformation.

| serial number | Account | Account profile | Retweets | Likes | Comments | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HongKongFP | The official account of Hong Kong Free Press, which mainly reports news related to Hong Kong. | 654,222 | 789,029 | 57,968 | 1,501,219 |

| 2 | VOAChinese | The official account of Voice of America Chinese website | 238,738 | 665,571 | 229,956 | 1,134,265 |

| 3 | rihanna | Personal account of Barbados entertainer, businessman and diplomat Robyn Rihanna Fenty | 121,304 | 893,770 | 12,662 | 1,027,736 |

| 4 | Reuters | The official account of Reuters news agency | 413,966 | 513,806 | 68,239 | 996,011 |

| 5 | QuickTake | The official account of the media Bloomberg QuickTake News | 405,652 | 529,201 | 44,900 | 979,753 |

| 6 | benedictrogers | Personal account of Benedict Rogers, human rights activist on Asia-related affairs and member of the Conservative Party Human Rights Committee | 393,940 | 495,171 | 48,721 | 937,832 |

| 7 | HawleyMO | Personal account of Missouri Senator and constitutional lawyer Josh Hawley | 317,008 | 493,603 | 66,899 | 877,510 |

| 8 | realDonaldTrump | The official account of the then (45th) US President Trump | 133,865 | 618,121 | 115,854 | 867,840 |

| 9 | joshuawongcf | The personal account of Huang Zhifeng, then secretary-general of the Hong Kong Zhongzhi Organization | 294,935 | 527,094 | 31,618 | 853,647 |

| 10 | JoshuaPotash | We-Media accounts, mainly focusing on social and political movements around the world | 240,053 | 565,680 | 18,852 | 824,585 |

| 11 | RFA_Chinese | The official account of Radio Free Asia | 192,221 | 453,095 | 92,227 | 737,543 |

| 12 | nytimes | The official account of The New York Times | 227,991 | 370,746 | 37,552 | 636,289 |

| 13 | LifetimeUSCN | The We-Media account of “LIFETIME Vision”, claiming to be an independent researcher on China issues and Sino-US relations | 144,198 | 447,405 | 38,340 | 629,943 |

| 14 | SpeakerPelosi | The personal account of then-Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi | 130,111 | 410,253 | 61,510 | 601,874 |

| 15 | SenRickScott | Personal account of then U.S. Senator of Florida Rick Scott | 230,335 | 324,511 | 41,308 | 596,154 |

| 16 | MarshaBlackburn | Personal account of junior U.S. Senator of Tennessee Marsha Blackburn | 218,512 | 290,242 | 33,847 | 542,601 |

| 17 | choi_bts2 | The personal account of a Korean working in Hong Kong, claiming to be a fan of the Korean male idol group BTS | 128,969 | 404,771 | 5,483 | 539,223 |

| 18 | business | The official account of Bloomberg Businessweek | 227,069 | 272,861 | 33,676 | 533,606 |

| 19 | Jordan_Sather | Personal account of Jordan Sather, a We-Media content producer, focusing on international political and economic issues | 117,367 | 396,168 | 5,833 | 519,368 |

| 20 | lihkg_forum | The official account of LIHKG, a discussion forum of Hong Kong hot topic | 241,214 | 244,113 | 14,040 | 499,367 |

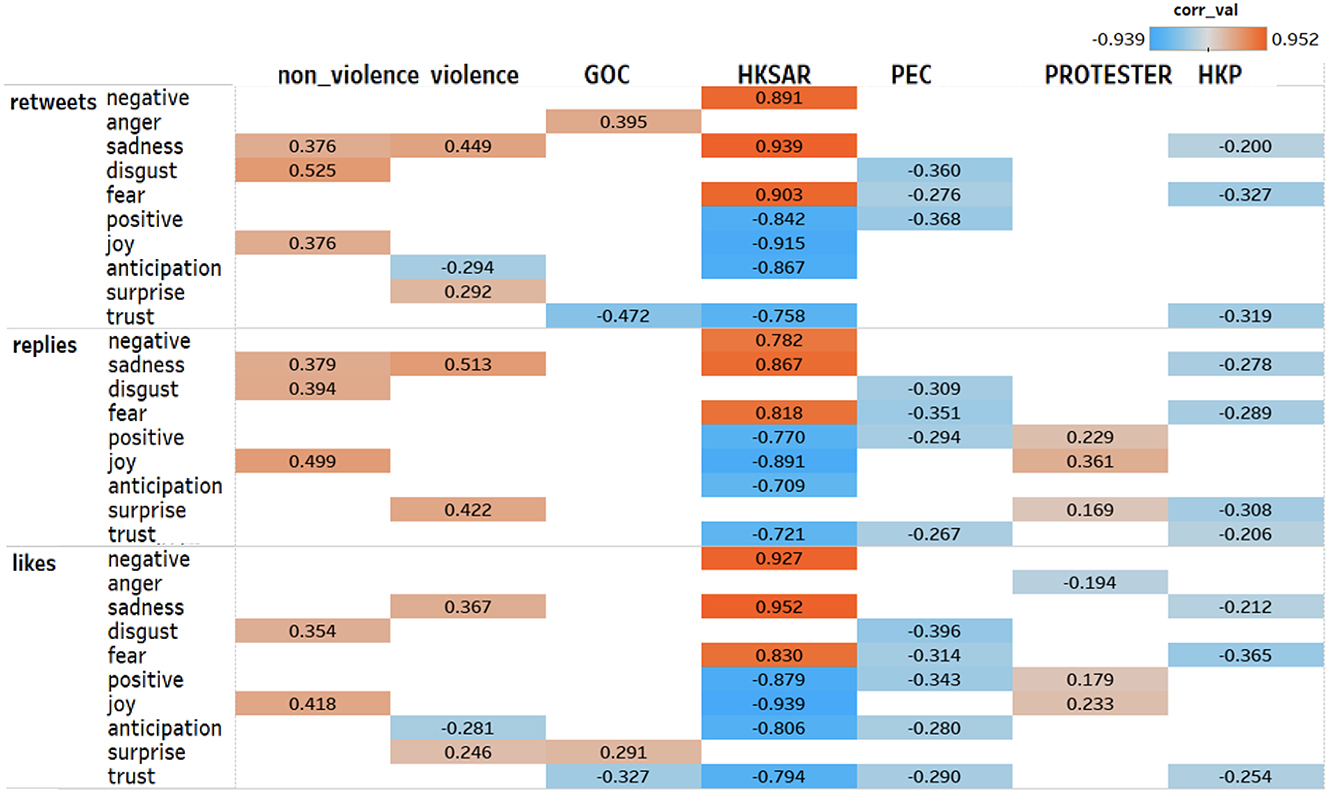

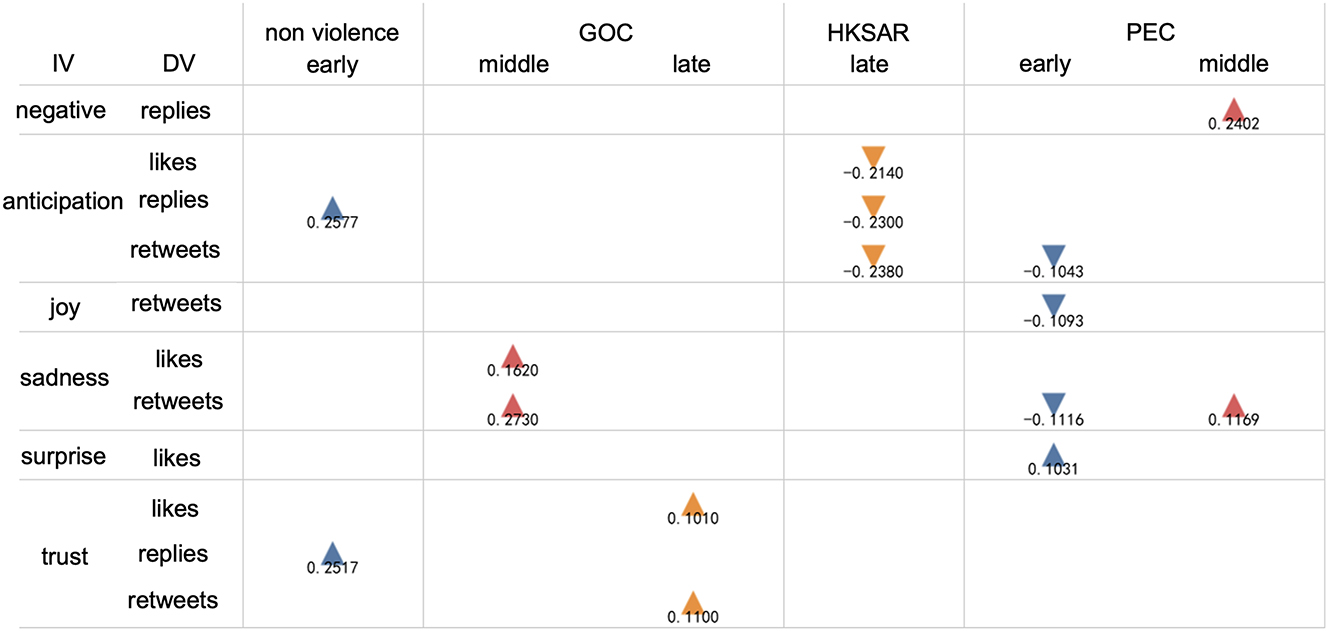

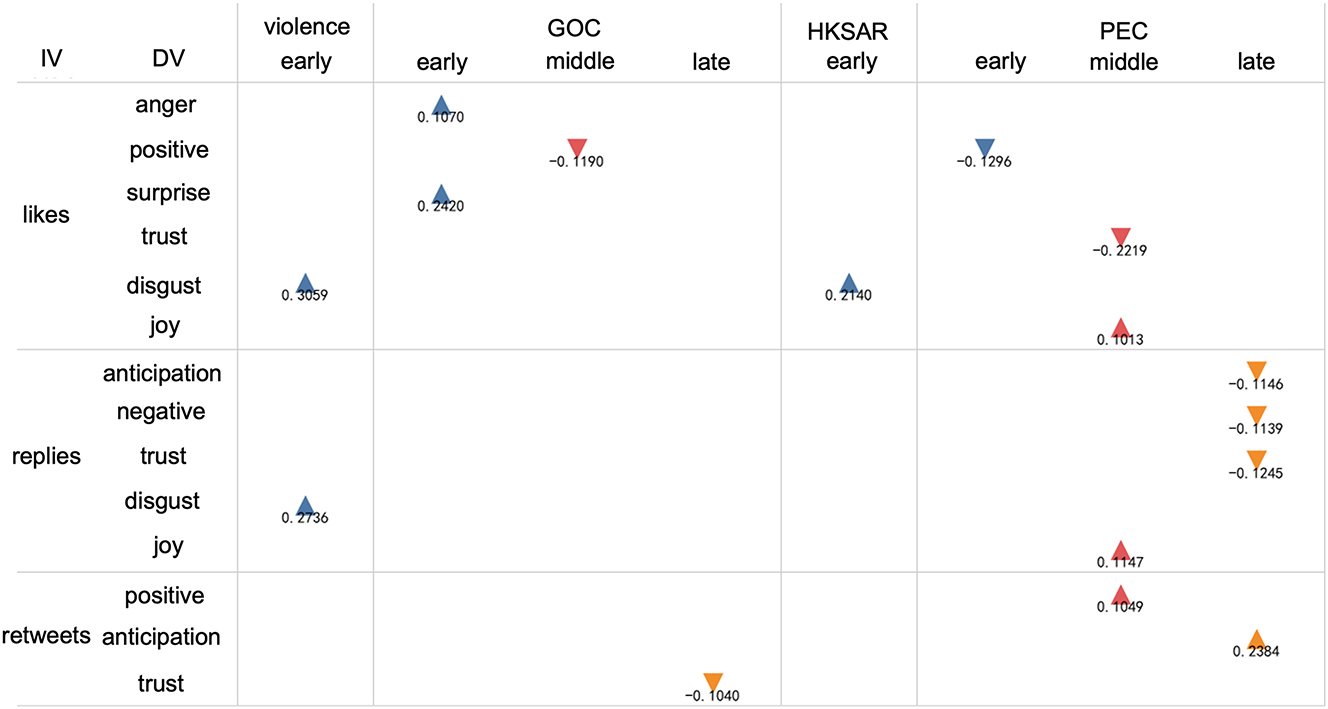

The strategies protesters use to mobilize a wide range of international “alliances” is extremely detailed. As seen in the specific practices of Anti-extradition Law Protests, protesters not only designed different emotional frameworks for different subjects, but also released various information depending on the type of action and the stage of the movement. To this end, we compared the correlation between the communication effects (retweets, comments, and likes) and the emotional types of the disinformation targeting at the protesters, Hong Kong police, the central government of China, the pro-establishment legislators, and the Hong Kong SAR Government under two different types of actions: violent and non-violent. In order to know the dynamic communication effect, we also adopted time series correlation analysis for the combination of the above variables and retained significant inter-variate relationships (p < 0.05) for data visualization (e.g., as shown in Figure 3).

The correlation results of disinformation in communication effect and sentiment. Note: only the data of the significant part (p < 0.05) are shown in the figure.

The analysis found that the relationship between the emotion type of disinformation and the communication effect was different under different conditions: (1) under the conditions of violent and non-violent actions, disinformation expressing sadness and disgust generally achieved better communication effect; (2) when targeting at the HKSAR Government, the relationship between positive and negative emotions in the disinformation and the communication effect was sharply polarized, disinformation with negative emotions achieve better communication effect and the opposite is true for disinformation with positive emotions; (3) when targeting at protesters, disinformation with positive, pleasant and surprising emotions achieve better communication effect.

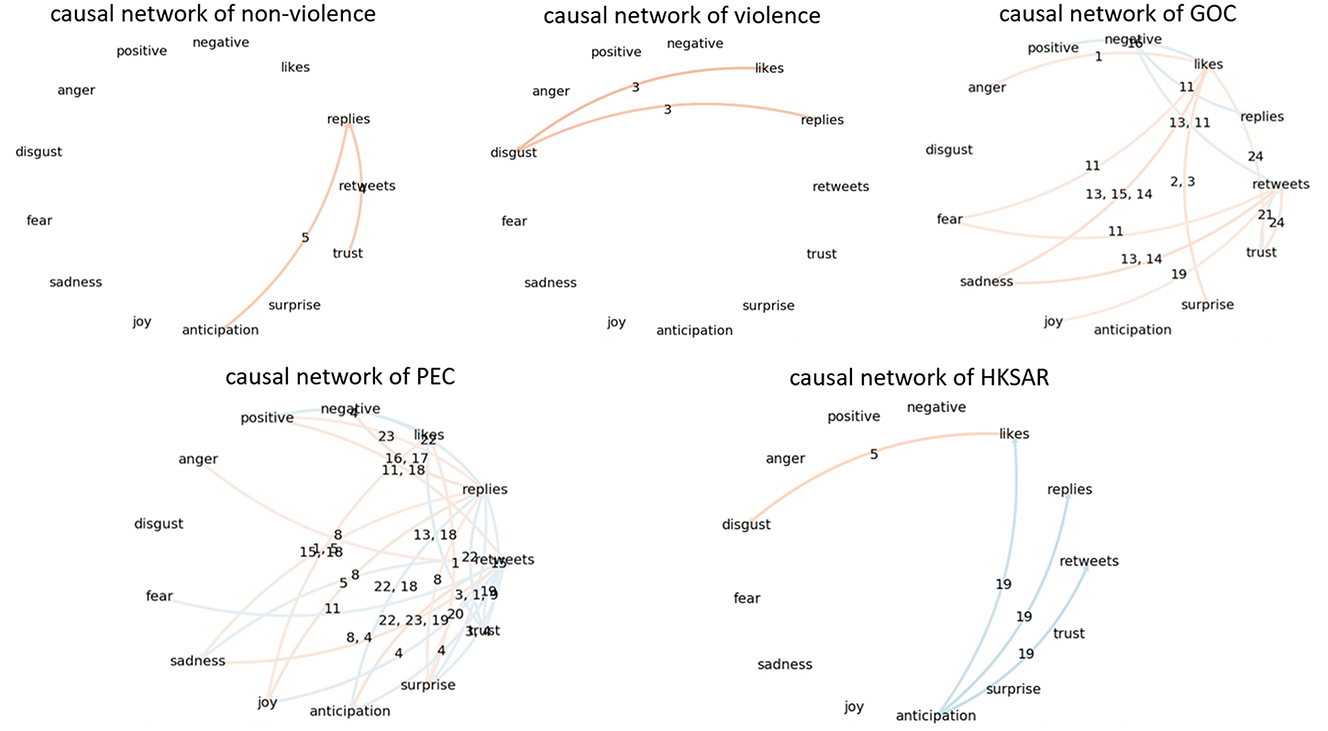

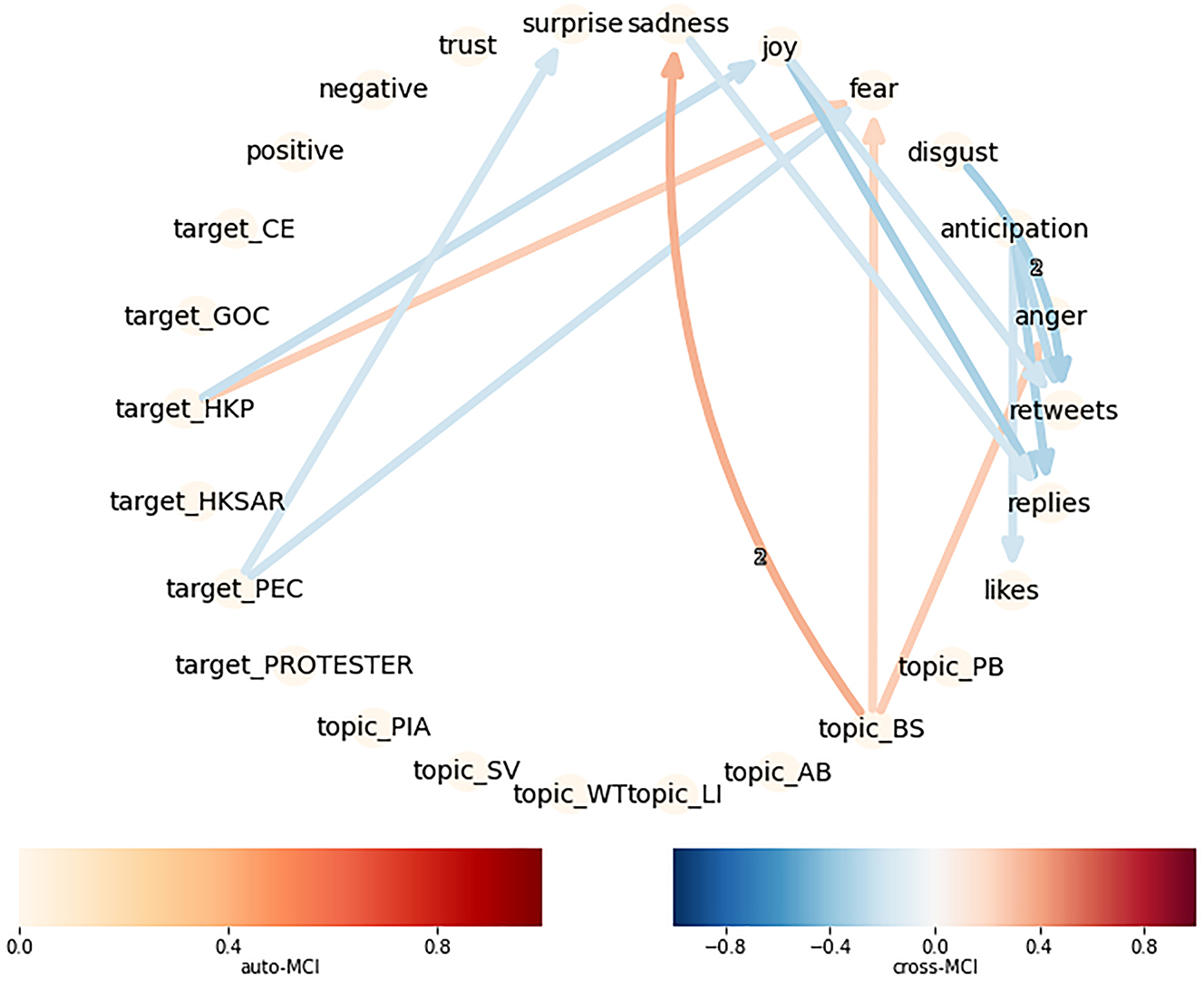

The above analysis shows a correlation between the type of emotion embedded in disinformation and the communication effect, but it is insufficient to explain the interaction between the two. For this reason, we conducted a non-linear causal analysis of the same data sample based on time series (as shown in Figure 4). To sort out the causal network more clearly, we used emotion type and communication effects as independent and dependent variables, respectively, and divided the lagged period of causal influence into early, middle, and late periods (early ≤ 6, 6 < middle < 18, and late ≥ 18 with hourly time granularity) for two-way causal presentation (as shown in Figures 5 and 6).

24-period lagged time series causality network between the emotion type embedded in disinformation and communication effects under different conditions. Note: the nodes of the network are various variables, the connected edges of the network indicate the existence of a causal relationship between two variables, the point of the arrow indicates the influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable, the number of lags of the connected edges indicates the existence of the causal relationship, blue indicates negative causality, red indicates positive causality.

Causal relationship when emotion type is the independent variable. Note: triangular indicates positive causal influence, inverted triangle indicates negative causal influence, and the number below the image indicates the value of the causal association, and all causal correlations shown in the figure are significant (sig < 0.05).

Causal relationship when communication effect is the independent variable. Note: triangular indicates positive causal influence, inverted triangle indicates negative causal influence, and the number below the image indicates the value of the causal association, and all causal correlations shown in the figure are significant (sig < 0.05).

The analysis revealed a clear difference in the order of causality between the emotion type embedded in the disinformation and its communication effect in violent and non-violent actions: (1) under the condition of violent actions, the early-stage communication effect as the independent variable mainly drove the negative emotion (mainly aversion); (2) under the condition of non-violent actions, the positive emotion (mainly expectation and trust) in the early stage promoted further transmission of disinformation.

In addition to emotional factors, do other content factors (e.g., the subject and theme contained in the content) also have an impact on the communication effect? In order to further analyze the mechanism of the effect of online communication, this study continued to include the factors of the subject and theme contained in the content to construct a causality network (as shown in Figure 7). The variables concerning subjects and themes are also time series obtained by aggregation calculations. The results show that there is a correlation between the amount of content containing individual subjects (Hong Kong police and pro-establishment legislators) and the emotions embedded in the disinformation. For example, the more content about the Hong Kong police, the more pronounced the fear embedded in the disinformation, and the opposite for pleasure. Individual subjects (blame shifting) can also have an impact on the emotions embedded in disinformation. However, neither the subjects nor the themes contained in the content have a direct effect on the communication effect itself. It is the emotion embedded in the disinformation that directly affects the communication effect. This indicates that the influence of emotional factors on online likes, comments and retweets is more significant.

A time-series causal network of subjects, themes, emotions and online communication effects contained in disinformation.

It is thus clear that emotion is the direct and significant influencing factor in communication effects of disinformation, and content with emotional arousal may be more likely to proliferate. The types of emotions embedded in disinformation under different conditions have diverse relationships with the communication effects.

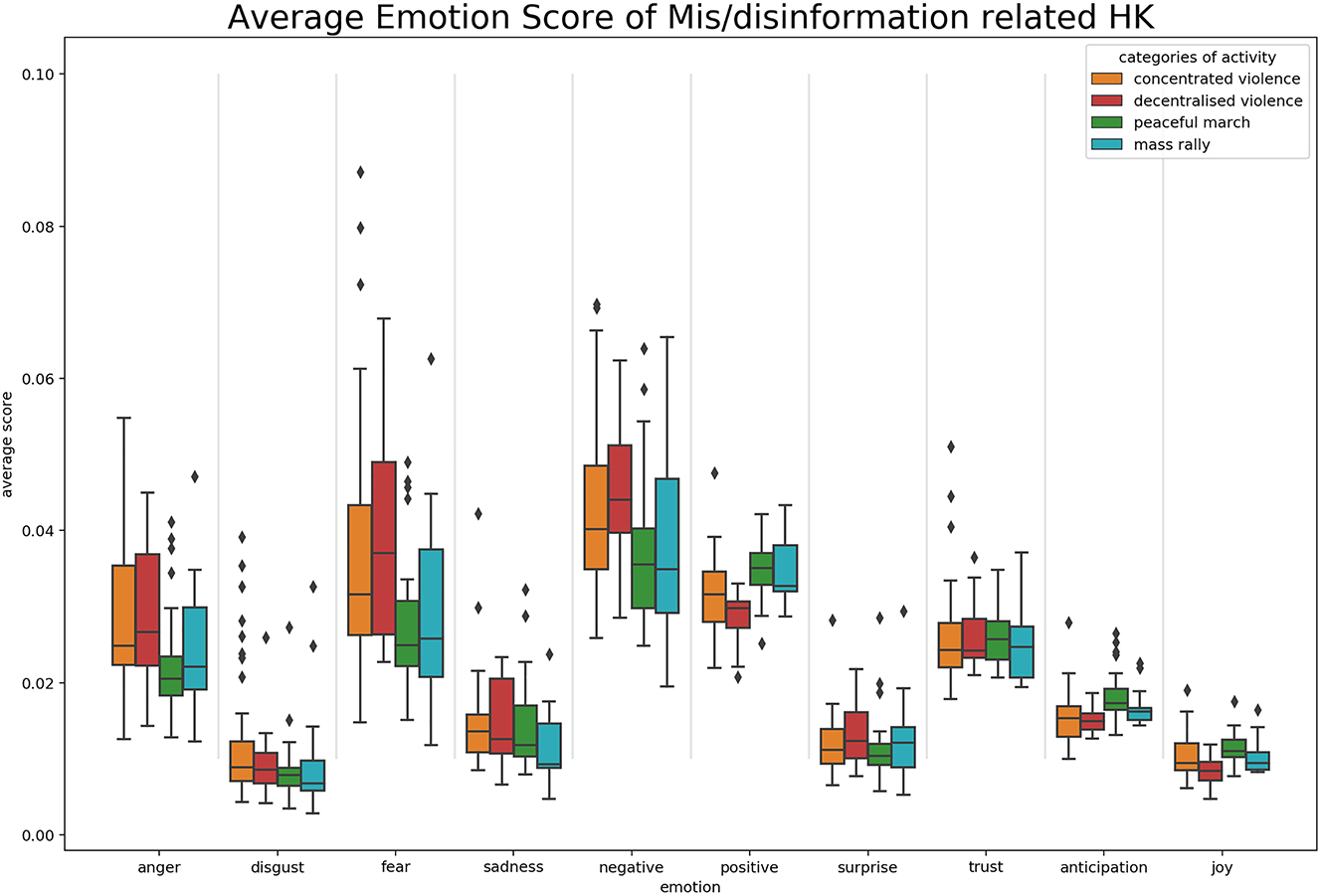

4.4 Concerted action: an analysis of the correlation between the type of emotion embedded in disinformation and the type of concerted action

The mechanism by which disinformation acts on social movements lies in its emotional mobilization, so what is the relationship between the different types of emotions embedded in disinformation and the forms taken by actions? In order to answer this question, an emotion analysis of disinformation in different action types is required. The daily average scores for each emotion type were calculated and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed. The results are shown in Table 4: during the different types of actions, there were significant differences in anger, fear, and sadness in the negative emotions of disinformation (p < 0.05), and in expectation and pleasure in the positive emotions (p < 0.01). However, the overall level of significance cannot explain specifically which types of actions show emotion differences in their comparisons, so pairwise comparisons are also needed.

Kruskal-Wallis test and pairwise comparison of daily mean scores for each emotion type.

| Types of actions (median) | Kruskal-Wallis test statistic | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrated violence (n = 44) | decentralized violence (n = 17) | Mass rally (n = 15) | Peaceful march (n = 26) | |||

| Anger | 0.025 | 0.027 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 9.586 | 0.022* |

| Disgust | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 4.074 | 0.254 |

| Fear | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 10.63 | 0.014* |

| Sadness | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 8.149 | 0.043* |

| Negative | 0.04 | 0.044 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 9.893 | 0.019* |

| Positive | 0.032 | 0.03 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 29.026 | 0.000** |

| Surprise | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.01 | 3.334 | 0.343 |

| Trust | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 1.07 | 0.784 |

| Anticipation | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 15.453 | 0.001** |

| Joy | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 14.95 | 0.002** |

| Emotion | Sample 1–sample 2 | Test statistics | Standard error | Standardized test statistic | Significance | Adjusted significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | Concentrated violence-peaceful march | 19.370 | 7.319 | 2.646 | 0.008 | 0.049* |

| Anticipation | Concentrated violence-peaceful march | −25.281 | 7.319 | −3.454 | 0.001 | 0.003** |

| Anticipation | Decentralized violence-peaceful march | −29.372 | 9.229 | −3.183 | 0.001 | 0.009** |

| Fear | Decentralized violence-peaceful march | 25.275 | 9.229 | 2.739 | 0.006 | 0.037* |

| Joy | Decentralized violence-peaceful march | −35.492 | 9.229 | −3.846 | 0.000 | 0.001** |

| Negative | Decentralized violence-peaceful march | 26.006 | 9.229 | 2.818 | 0.005 | 0.029* |

| Positive | Decentralized violence-mass rally | −38.647 | 10.482 | −3.687 | 0.000 | 0.001** |

| Positive | Decentralized violence-peaceful march | −44.820 | 9.229 | −4.857 | 0.000 | 0.000** |

| Positive | Concentrated violence-peaceful march | −26.184 | 7.319 | −3.578 | 0.000 | 0.002** |

-

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

-

Note: tables only show significant results. The null hypothesis for each row test is that sample 1 and sample 2 are equally distributed. Asymptotically significant (two-sided test) is shown. The significance level is 0.05. Significance values have been adjusted for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction.

Looking further at the distribution of daily mean scores for each type of disinformation emotion (as shown in Figure 8) and the results of pairwise comparisons (shown in Table 4), important differences can be found: different from peaceful marches, anger is more prominent in disinformation disseminated during concentrated violent actions, and fear is more prominent in disinformation disseminated during decentralized violent actions; while compared to decentralized violent actions, the positive emotions of expectation and pleasure are more prominent in the disinformation during the peace march.

Average daily distribution of each type of emotion during different types of actions.

How can we understand the distinct differences in the emotions embedded in disinformation during peaceful marches compared to decentralized or concentrated violence? The emotion types and their intensity underlie social movements from emergence to decline, and emotions not only influence the various phases of the movement but are also key to the fight (Yang and Pace 2016). Specifically, emotions not only strengthen the sense of group identity and belonging, expands sympathizers and supporters, but also may shape the group’s perception of the target of phased action (Jasper 1998). Research in political psychology have also found that anger and fear drive very different political actions (Brader and Marcus 2013): anger, which is usually attributed to a specific source from which individuals perceive themselves to be suppressed, is more likely to form unifying goals or antagonistic enemies and to increase intra-group identity and solidarity (Nepstad 2004); in contrast, however, fear, which usually points to an unknown outcome, is more of a negative emotion that lacks a sense of control. Thus, when movement participants have a clear target to blame, attention is unified and anger is directed toward hatred of the “external enemy” and the “sense of justice” that comes from attacking the “enemy.” The more likely outcome is concentrated violence. However, it was found in this study that overall fear was more prominent than anger (as shown in Figure 8), with higher levels of fear embedded in disinformation when violent actions happen simultaneously in multiple zones. This is a time when movement participants are less unified and lack control over their attack targets and are more likely to engage in decentralized violence. In contrast, positive emotions such as expectation and pleasure are more prominent during peaceful actions. Peaceful actions, i.e. marches and rallies, are used to disseminate the demands of the protesting group, focusing on the “ideals” and “values” of the group, to gain external sympathy or support, and at the same time reinforcing the sense of belonging and identity of the community through rituals. Peaceful action has a special significance for sustaining the movement itself. Goodwin and Pfaff argued from a theoretical perspective of emotion management that when collectives face fear deterrence, movement participants mobilize “motivation mechanisms” (e.g., peace rallies) to “manage fear,” and movement activists strive to build emotional solidarity and a sense of collective identity (Goodwin and Pfaff 2001).

However, it is difficult for difference statistics to reveal the direction of action among various factors. To further analyze the dynamic relationship between the emotions embedded in disinformation and offline activities, this study continued to construct a time-series causality network. In this regard, the various emotions embedded in disinformation remain aggregated by date for the scores, while the variables on violent and peaceful actions are aggregated by date for the number of occurrences of the actions. The results, as shown in Table 5, show a significant current effect between emotions embedded in disinformation and offline activities: emotions of anger and fear embedded in disinformation promote the occurrence of violent activities. Conversely, positive emotions have a negative effect on the occurrence of violent activities, which echoes the analysis above.

The causal relationship between the emotion inherent in disinformation and offline activities.

| Independent variable | Dependent variable | Lag period | Causality value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | Violent action | 0 | 0.1522 | 0.0456* |

| Fear | Violent action | 0 | 0.1882 | 0.0132* |

| Positive | Violent action | 0 | −0.2488 | 0.0009** |

-

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

In conclusion, through social media platforms, disinformation, together with the narrative themes produced by various types of emotions, can construct protesters’ imagination of the community and maintain the emotional dynamics of action by establishing group identity and boundaries and strengthening the sense of identity and belonging of the group, which demonstrates the social integration role of emotions. The emotions embedded in disinformation not only influence the effect of online communication, but also influence the development of collective activities offline, which has a mobilizing effect.

5 Conclusions

In the Hong Kong Anti-extradition Law Protests, the disinformation targeting at different subjects, such as protesters and Hong Kong police officers, adopted different narrative strategies, produced different emotional frames, and exerted significant mobilization effects. It was found that (1) the emotions embedded in the disinformation had a direct impact on the online communication effect, rather than the subjects and themes contained in the content. There is a complex correlation and bidirectional causality between the types of emotions embedded in disinformation and their communication effects under different conditions: negative emotions dominated by disgust, sadness, and anger generally achieve good communication effects, while emotions such as expectation and trust drove communication effects in the context of nonviolent actions. (2) There are significant differences in the types of emotions embedded in disinformation under different types of protest actions: anger embedded in disinformation is more prominent in concentrated violent actions, fear embedded in disinformation is more prominent in decentralized violent actions, while positive emotions of anticipation and joy embedded in disinformation are more prominent in peaceful actions; moreover, the emotions of anger and fear are causally associated with the development of violent actions.

The emotions embedded in disinformation have a powerful effect on the community, reinforcing group boundaries by creating an “external enemy” on the one hand, and creating a sense of belonging to the group and strengthening identity by constructing collective memory on the other. Based on the establishment of identity, the “emotional community” is continuously expanded through the emotional orientation of different “target” groups, and the scale of their alliance is enlarged, and groups of protesters also take different levels of violent actions or peaceful marches and rallies. This reflects the characteristics of “post-truth politics,” in which identity and emotion, rather than facts and truth, become the factors that sustain and dominate group action, and “identity” becomes the overriding group cohesion. This is not only related to the uncertainty of today’s politics and economy, the growth of post-modernism and relativism, but also to the complex form of facts and truth under the influence of media today. Facts and truths are increasingly becoming a kind of data facts and networked facts, and the “big and unknowable” nature of facts has exacerbated the confirmation bias (Hu 2017). In the context of the lack of attractiveness of facts and truth, emotion and identity become the dominant factors to unite the group. Disinformation on the one hand creates a mimetic environment to influence the audience’s cognitive attributions, and on the other hand, with the help of the strong emotions it contains, prompts protesters to complete their imagination of the community, and also attracts international supporters across geography, race, and culture. It is particularly alarming that the sustainment of emotional power is one of the important factors that caused the Anti-extradition Law Protests to last for such a long time and trigger serious violent actions.

However, some weaknesses exist in this paper. First, there are limitations in using the emotion lexicon approach for emotion analysis. The Twitter data used in this study contains a certain proportion of “traditional Chinese” data (mainly from Cantonese speakers). Some of these “slang” words are not included in the conventional emotion lexicon, which may bias the emotion analysis results to some extent. Second, this study focuses only the textual data on Twitter, while images and videos have been widely disseminated during the Anti-extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong, and the effect of visual analysis on emotional mobilization needs to be further explored. Third, in reality, social action is a mixed information environment of true and false information, and one of the main strategies of disinformation is the interplay of true and false information. The interrelationship between true and false information and its impact on social movements also deserve further examination.

Acknowledgement

This article is a phased research output of the National Social Science Foundation’s key project, “Research on Risk Communication and Effectiveness Assessment in Public Crises” (Project No. 20AXW008).

References

Allport, Gordon & Leo Postman. 1947. The psychology of rumor. New York: Henry Holt and Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Balmas, Meital. 2014. When fake news becomes real: Combined exposure to multiple news sources and political attitudes of inefficacy, alienation, and cynicism. Communication Research 41(3). 430–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212453600.Suche in Google Scholar

Banjo, Shelly & Natalie Lung. 2019. How fake news and rumors are stoking division in Hong Kong. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-11/how-fake-news-is-stoking-violence-and-anger-in-hong-kong (accessed 11 November 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Lance & Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33(2). 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317.Suche in Google Scholar

Bolsover, Gillian & Philip Howard. 2019. Chinese computational propaganda: Automation, algorithms and the manipulation of information about Chinese politics on Twitter and Weibo. Information, Communication & Society 22(14). 2063–2080. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2018.1476576.Suche in Google Scholar

Brader, Ted. & George Marcus. 2013. Emotion and political psychology. In Leonie Huddy (ed.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology, 165–204. New York: Reprinted by Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199760107.013.0006Suche in Google Scholar

Cai, Ruixiong. 2009. Financial time series analysis. Beijing: China Machine Press. 蔡瑞胸. 2009. 金融时间序列分析. 北京: 机械工业出版社.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Hsuan-Ting, Chen Gan & Ping Sun. 2017. How does political satire influence political participation? Examining the role of counter-and pro-attitudinal exposure, anger, and personal issue importance. International Journal of Communication 11(2017). 3011–3029.Suche in Google Scholar

Durkheim, Emile. 2013. The division of labor in society, 204–218. Digireads.com Publishing (e-book edition).Suche in Google Scholar

Giglietto, Fabio, Laura Iannelli, Augusto Valeriani & Luca Rossi. 2019. ‘Fake news’ is the invention of a liar: How false information circulates within the hybrid news system. Current Sociology 67(4). 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119837536.Suche in Google Scholar

Goodwin, Jeff & Steven Pfaff. 2001. Emotion work in high-risk social movements: Managing fear in the U.S. and East German civil rights movements. In Jeff Goodwin (ed.), Passionate politics: Emotions and social movements, 282–302. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226304007.003.0017Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, Xiao’an. 2013. The sympathetic resonance aroused by rumors in the network-protest: Strategies and repertoires. Chinese Journal of Journalism & Communication 35(12). 56–69. 郭小安. 2013. 网络抗争中谣言的情感动员: 策略与剧目. 国际新闻界 35(12). 56–69.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, Xiaoan & Shiyao Yan. 2014. Rumors and emotional mobilization in online public events: A reanalysis of the “Li Gang scandal”. Cultural Studies (03). 102–114. 郭小安 & 严诗瑶. 网络公共事件中的谣言与情感动员——“李刚门” 事件的再分析. 文化研究 (03). 102–114.Suche in Google Scholar

Hu, Yong. 2017. “Post-truth” and the future of politics. Journalism & Communication 24(04). 5–13. 胡泳. 2017. 后真相与政治的未来. 新闻与传播研究》24(04). 5–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Jasper, James. 1998. The emotions of protest: Affective and reactive emotions in and around social movements. Sociological Forum 13(3). 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022175308081.10.1023/A:1022175308081Suche in Google Scholar

Lazer, David M., Matthew A. Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J. Berinsky, Kelly M. Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J. Metzger, Brendan Nyhan, Gordon Pennycook, David Rothschild, Michael Schudson, Steven A. Sloman, Cass R. Sunstein, Emily A. Thorson, Duncan J. Watts & Jonathan L. Zittrain. 2018. The science of fake news. Science 359(6380). 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Hoon & Nojin Kwak. 2014. The affect effect of political satire: Sarcastic humor, negative emotions, and political participation. Mass Communication and Society 17(3). 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891133.Suche in Google Scholar

Lew, Linda. 2019. Fake news and Hong Kong protests: Truth becomes the victim. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3032734/fake-news-and-hong-kong-protests-psychological-war-hearts (accessed 14 October 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Maffesoli, Michel & Charles R. Foulkes. 1988. Jeux de masques: Postmodern tribalism. Design Issues 4(1/2). 141–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511397.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohammad, Saif & Peter Turney. 2013. Crowdsourcing a word–emotion association lexicon. Computational Intelligence 29(3). 436–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8640.2012.00460.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohammad, Saif & Peter Turney. 2010. Emotions evoked by common words and phrases: Using mechanical turk to create an emotion lexicon. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Analysis and Generation of Emotion in Text, 26–34.Suche in Google Scholar

Mourão, Rachel R. & Craig Robertson. 2019. Fake news as discursive integration: An analysis of sites that publish false, misleading, hyperpartisan and sensational information. Journalism Studies 20(14). 2077–2095. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2019.1566871.Suche in Google Scholar

Nepstad, Sharon Erickson. 2004. Convictions of the soul: Religion, culture, and agency in the Central America solidarity movement. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0195169239.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Pinazo-Calatayud, Daniel P. C., Eloísa N. A. Nos-Aldás, Sonia A. N. Agut-Nieto, Daniel Pinazo-Calatayud, Eloisa Nos-Aldas & Sonia Agut-Nieto. 2020. Positive or negative communication in social activism. Comunicar. Media Education Research Journal 28(62). 69–78. https://doi.org/10.3916/c62-2020-06.Suche in Google Scholar

Polletta, Francesca & Jessica Callahan. 2017. Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 5(3). 392–408. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-017-0037-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Robles, Pablo. 2020. Hong Kong protests: Key events of the past six months. South China Morning Post. http://bit.ly/2LXHsjg (accessed 2 February 2020).Suche in Google Scholar

Rojecki, Andrew & Sharon Meraz. 2016. Rumors and factitious informational blends: The role of the web in speculative politics. New Media & Society 18(1). 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814535724.Suche in Google Scholar

Ross, Andrew & Damian Rivers. 2018. Discursive deflection: Accusation of “fake news” and the spread of mis- and disinformation in the tweets of President Trump. Social Media + Society 4(2). 2056305118776010. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118776010.Suche in Google Scholar

Runge, Jakob, Sebastian Bathiany, Erik Bollt, Gustau Camps-Valls, Dim Coumou, Ethan Deyle, Clark Glymour, Marlene Kretschmer, Miguel D. Mahecha, Jordi Muñoz-Marí, Egbert H. van Nes, Jonas Peters, Rick Quax, Markus Reichstein, Marten Scheffer, Bernhard Schölkopf, Peter Spirtes, George Sugihara, Jie Sun, Kun Zhang & Jakob Zscheischler. 2019a. Inferring causation from time series in Earth system sciences. Nature Communications 10(1). 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10105-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Runge, Jakob, Peer Nowack, Marlene Kretschmer, Seth Flaxman & Dino Sejdinovic. 2019b. Detecting and quantifying causal associations in large nonlinear time series datasets. Science Advances 5(11). eaau4996. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4996.Suche in Google Scholar

Scheufele, Dietram & Nicole Krause. 2019. Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(16). 7662–7669. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805871115.Suche in Google Scholar

Schuck, Andreas & Claes de Vreese. 2012. When good news is bad news: Explicating the moderated mediation dynamic behind the reversed mobilization effect. Journal of Communication 62(1). 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01624.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Tandoc, Edson. 2019. The facts of fake news: A research review. Sociology Compass 13(9). e12724. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12724.Suche in Google Scholar

Tandoc, EdsonJr, Zheng Wei Lim & Richard Ling. 2018. Defining “fake news” a typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism 6(2). 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143.Suche in Google Scholar

Umbricht, Andrea & Frank Esser. 2016. The push to popularize politics. Journalism Studies 17(1). 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2014.963369.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Yan. 2008. Applied time series analysis. Beijing: China Renmin University Press. 王燕. 2008. 应用时间序列分析. 北京: 中国人民大学出版社.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, Tiebing & Hubert Petit. 2014. Research on the theory of tribes according to Michel Maffesoli. Journal of Northwest University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 44(01). 21–27. 许轶冰 & 波第·于贝尔. 2014. 对米歇尔·马费索利后现代部落理论的研究. 西北大学学报(哲学社会科学版) 44(01). 21–27.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Guobin & Jonathan Pace. 2016. Emotions and social movements. In Ritzer George (ed.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology, 1–4. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.10.1002/9781405165518.wbeose040.pub2Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Guobin. 2013. Online civil movement within multiple interaction. Journalism Evolution 29(02). 4–16. 杨国斌. 多元互动条件下的网络公民行动. 新闻春秋 29(02). 4–16.10.12677/JWRR.2013.22020Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Guobin. 2009. Of sympathy and play: Emotional mobilization in online collective action. The Chinese Journal of Communication and Society 9. 39–66. 杨国斌. 2009. 悲情与戏谑: 网络事件中的情感动员. 传播与社会学刊 9. 39–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Zou, Sheng. 2020. Emotional news, emotional counterpublic unraveling the construction of fear in Chinese diasporic community online. Digital Journalism 8(2). 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1476167.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Themed Section Editorial Essay

- Digital cities theme section editorial essay: approach digital cities from the communication perspective

- Summer Issue Editorial Essay

- Summer 2023 editorial essay: digital cities, ChatGPT use in Africa, Nigerian online news coverage of the Russian–Ukraine war and use of emotional mobilization and disinformation in Hong Kong anti-extradition protests

- Themed Section: Digital Cities and Re-Mediation of Global Civilization

- Beyond the smart city: a communications-led agenda for twentyfirst century cities

- Managing future cities: media and information and communication technologies in the context of change

- Data plantation: Northern Virginia and the territorialization of digital civilization in “the Internet Capital of the World”

- Original Articles

- CHATGPT and the Global South: how are journalists in sub-Saharan Africa engaging with generative AI?

- Sahara Reporters and Premium Times online coverage of the Russia–Ukraine war

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Emotional community and concerted action: on the emotional mobilization mechanism of disinformation in the Anti-extradition Law amendment movement in Hong Kong

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Themed Section Editorial Essay

- Digital cities theme section editorial essay: approach digital cities from the communication perspective

- Summer Issue Editorial Essay

- Summer 2023 editorial essay: digital cities, ChatGPT use in Africa, Nigerian online news coverage of the Russian–Ukraine war and use of emotional mobilization and disinformation in Hong Kong anti-extradition protests

- Themed Section: Digital Cities and Re-Mediation of Global Civilization

- Beyond the smart city: a communications-led agenda for twentyfirst century cities

- Managing future cities: media and information and communication technologies in the context of change

- Data plantation: Northern Virginia and the territorialization of digital civilization in “the Internet Capital of the World”

- Original Articles

- CHATGPT and the Global South: how are journalists in sub-Saharan Africa engaging with generative AI?

- Sahara Reporters and Premium Times online coverage of the Russia–Ukraine war

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Emotional community and concerted action: on the emotional mobilization mechanism of disinformation in the Anti-extradition Law amendment movement in Hong Kong