Abstract

This article discusses the origins and development of research on online media and online political communication studies in Brazil. It analyzes the factors influencing the origins and development of the research on online media in the country. One the one hand, Brazil belongs to the semiperiphery of the international research system. On the other hand, when the online media appeared, there was already a solid tradition of Communication research in the country. It presents an overview of how Communication education and research organized in Brazil. Against this backdrop, it presents three stages of online media research development in Brazil: (a) incipient, (b) consolidation, and (c) new frontiers. In particular, it examines the impact that online media had on the Brazilian Political Communication research agenda.

1 Introduction

This article explores the evolution of the research on online media in Brazil. Brazil has been often defined as a country belonging to the semiperiphery of the international research system (Bennett 2014). We argue that Brazil already had an established tradition in Communication research for decades before the emergence of online media research. However, much of this research is unknown to foreign audiences, since there is a language barrier, as much of it is published in Portuguese. We present a study based on a historical reconstruction of the field, drawing on interviews with senior scholars, online documents, and a dataset of theses and dissertations on the field, collected from the most important Brazilian database of theses and dissertations, the CAPES/CNPq database.[1] Our paper is organized as follows: First, it locates the origin of Brazilian Communication research in the context of a broader Latin American movement. Second, it discusses how Communication studies and research are organized in Brazil. The third section presents the method we employed in our study. The fourth section discusses how the scholarship on online media communication developed in Brazil, and how this affected the agenda of the scholarly research. Sections five and six present respectively the early debate and the consolidation of research on online media in Brazil. The last section examines how online media affected Political Communication, which is one of the most institutionalized subfields of Communication research in Brazil. The focus on a specific subfield may provide a more detailed account of the impact of the online media research in Brazilian Communication scholarship.

2 Brazil in the context of Latin America

When online media took its first steps in Brazil, the country already had a solidly established tradition in Communication research, focusing mainly on popular and mass communication (Albuquerque and Tavares 2021). Brazilian communication studies developed both about and in opposition to the US tradition, as it has in other Latin American countries since the 1960s. This happened for two complementary reasons. On the one hand, at that time, the influence of the US media in Latin America was greater than everywhere else. Countries like Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela adopted a commercial-oriented model of radio and television broadcasting, inspired by the US (Sinclair 1997), instead of the state-owned or public service models that predominated in most parts of the world.

On the other hand, many Latin American intellectuals were afraid of the US cultural influence in their native societies, which some of them dubbed “cultural imperialism” (Beltran 1976; Boyd-Barrett 2018). For this reason, communication studies developed in the region in a very different way than in the US: In the US, Communication developed primarily as “administrative research”, in association with an agenda of controlling public opinion (Glander 2000); otherwise, in Latin American Communication studies followed mainly a critical and cultural approach (Oliveira et al. 2021). Many Latin American intellectuals resisted the US ideology of developmentalism and the “Americanized” mass media, which, according to them, were in the service of US cultural imperialism (Boyd Barrett 2018). Latin American intellectuals exerted an important role in the making of UNESCO’s document “Many Voices, One World”, published in 1980.

The proximity between the languages spoken in Brazil (Portuguese) and the other countries in Latin America (Spanish) allowed these countries to establish a vigorous intellectual exchange, which has somewhat hampered the influence of the US academic agenda in the region (Demeter et al. 2022). Otherwise, Latin America has historically been intellectually closer to Western Europe, particularly countries that speak Romance languages like Spain and, especially, France (Daros 2021).

Latin America built a considerable academic infrastructure to support this exchange, including regional scientific associations such as CIESPAL (Centro Internacional de Estudios Superiores de Comunicación para América Latina, or International Center for High Studies in Communication for Latin America), ALAIC (Associación Latino Americana de Investigadores de La Comunicación, or Latin American Communication Researchers Association). Latin American researchers also developed a vast network of Communication journals. Unlike Anglophone journals, which are typically associated with commercial publishers and accessible via a paywall system, Latin American Communication journals are typically open access (Mellado 2010; Oliveira et al. 2021).

Since the 1990s, Latin America lost much of its international visibility (Ganter and Ortega 2019; Waisbord and Mellado 2014). At that time, there was a push for internationalizing Communication research, led by the US. This movement led the English language to become a lingua franca in international scholarship (Suzina 2021). A strongly US (and, to a lesser extent, Western) biased ranking system resulted in a global downgrade of Latin American Communication Studies (Albuquerque and Tavares 2021; Ganter and Ortega 2019). Nonetheless, the prospects for Latin American research’s global impact have recently improved. In a time when demands for de-Westernizing became more common, some scholars have suggested that the Ibero-American academic circuit may provide an “alternative universe to mainstream English-based communication research” (Demeter et al. 2022).

3 Communication education in Brazil

In Brazil, university undergraduate Communication programs developed earlier than in countries like Spain (Lopez-Escobar and Algarra 2017) and the United Kingdom (Golding 2019). The first one – Casper Libero College’s Journalism program – dates from 1947. In 1951, the Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, or PUC-RIO) created the first Advertising program. In the following year, Rio Grande do Sul Federal University (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, or UFRGS) created the first Public Relations program. During the 1950s 14 communication programs were created. By the end of the 1960s, there were 37 communication undergraduate programs in Brazil. For comparison, in Spain, the first communication program dates from 1958.

The premature development of communication programs in Brazil results from the cultural influence exerted by the United States in the country. Still, during World War II, the US government created the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) to establish closer relations with Latin American countries, based on the idea of “good neighbors” (Tota 2010). As consequence of these efforts, the US models became the gold standard for Brazilian communication professionals.

The number of communication programs in Brazil increased exponentially over the following decades. At the end of the 2010s, there were 445 programs in Journalism, 382 in Advertising, and 57 in Public Relations in the country. Brazilian undergraduate courses had a strong professional approach, although they usually had disciplines with a more theoretical approach, too. Reforms promoted by the National Council of Education diminished the number of disciplines with a theoretical approach in favor of those with a more “practical” tone (Albuquerque and Tavares 2021).

Brazil also has a five-decade tradition of graduate communication programs. São Paulo Catholic University (Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, or PUC-SP) created the first of such programs in 1970. Other programs were created by the University of São Paulo (Universidade de São Paulo, or USP), and Rio de Janeiro Federal University (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, or UFRJ) in 1972. By the end of the 1990s, there were 15 graduate programs in Brazil. Different from the undergraduate programs, Brazilian graduate programs have approached Communication from a broad perspective, keeping in mind the nature of the mediated messages and their social and cultural impact. When these graduate programs were created, the media that were the subject of analysis were principally broadcast and print media. Since the 2000s, Communication graduate programs have boomed in Brazil. At the present, there are 57 of these programs working in 24 of the 27 states of the country. Different from the early programs, for these newly created ones, online media was not a novelty, but the “new normal”.

Added to the universities, scientific associations and journals are core elements of the Brazilian Communication infrastructure. The two most important Communication scientific associations in Brazil are Intercom and Compós (Associação Nacional de Programas de Pós Graduação, or National Association of Graduate Programs in Communication). Both are catch-all organizations promoting annual national meetings for Communication researchers. There is also an association that specialized on online media, entitled ABCiber (Brazilian Association of Cyberculture Studies). Brazil has also dozens of open access Communication journals. Most of them are published by Communication associations or programs. At the present, the journals counting with the bigger h5 index, according to Google Scholar, are Revista Observatório (19), Reciis (16), Matrizes (14), Famecos (13), E-Compós and Galáxia (12), Contracampo and Intercom (11), and Intexto (10).

4 Methods

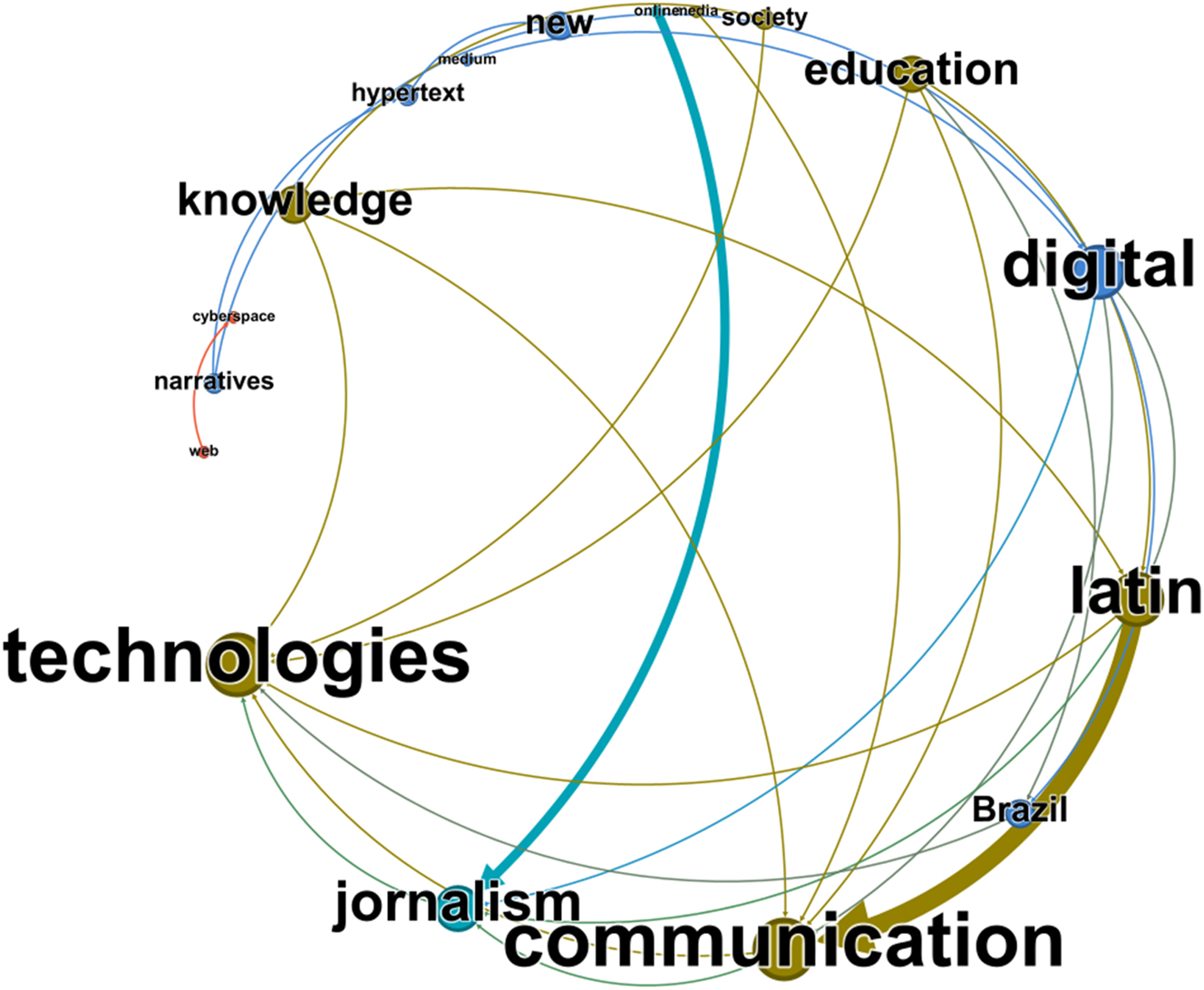

In this paper, we reconstruct and discuss the history and tradition of Brazilian Online Communication Studies. In particular, we focus on how research on online media impacted Brazilian Political Communication studies. Since the early 1990s, Political Communication has been one of the most consolidated research subjects in Brazilian Communication studies. For this motive, it provides a useful analytical subject for discussing the impact of online media on the Brazilian scholarly agenda. We adopted two different methodological strategies for discussing these two subjects. For analyzing research on online media as whole we employed: (1) informal interviews with three key senior scholars to reconstruct the history of the field and workgroups, based on the reconstruction of the timeline; (2) documental research on the major institutional repository in the country: the national dissertations/theses database from CAPES/CNPq. We used eight general keywords to search the databases to find research connected to the online communication studies in Brazil: “cyberculture”, “new information and communication technologies” (NICT), “digital” (D), “computer-mediated communication” (CMC), “online” (ON) and collected data on 1997 works; (3) quantitative computational content analysis of the general themes of these theses/dissertations, where we analyzed the titles and themes connected to these works. We used network analysis to better visualize the themes and their connections on the examined database. The graphs show the themes’ prevalence in each dataset (size of the theme) and its connections to others (thickness of the connection). The colors are used to show proximity among themes.

We opted to analyze theses and dissertations instead of articles published in journals for pragmatical reasons. On the one hand, the CAPES/CNPq databases are relatively well-organized to allow keyword-based research. The same does not happen to Brazilian journals. At the same, the time span covered by the theses and dissertations database is more comprehensive than the one provided by the Brazilian Communication journals or other databases we investigated. For this motive, the theses/dissertations databases provide a better tool for analyzing the evolution of online media research in Brazil, since its beginning.

The analysis of the political communication subfield follows a different approach. It explores the papers published in the annals of the Political Communication Working group. Compós’ Working Groups are very selective – initially twelve and later ten papers are discussed each year – and therefore this sample allows a more qualitative approach regarding its content. Given that only papers from 2000 are available in the Compós website, we recurred to personal interviews with researchers to obtain information about the previous meetings.

5 Online Media studies in Brazil: origins and evolution

Brazil has an established tradition of research in online media, which traces back to the late 1990s. Working Groups (WG) in Communication Studies national associations were critical in defining the parameters of the debate on this topic. The WG Communication and Cyberculture of Compós, created in 2004, was the most important reference for the institutionalization of online media studies in Brazil. Originally named “Information, Communication and Technological Society” (from 1996 to 2002) and later “Informational Technologies of Communication and Society” (2003–2006), it was renamed “Cyberculture” in 2007.

At the time, the concept of “cyberculture” was extremely popular in Brazil, owing primarily to Pierre Lévy’s work (and book of the same name published in 2001) and the pioneering work of Brazilian researcher André Lemos, who developed both the concepts of “cyberspace” and “cyberculture” (Lemos 2002; Lemos and Palácios 2000). In fact, Lemos’ university (UFBA – Universidade Federal da Bahia) was one the first research centers to introduce key concepts to communication research, such as “online journalism”, “computer-mediated interaction” and “online sociability” (Lemos 1997, 2001).

This historical timeline is supported by the number of thesis and dissertations about the theme in Brazil. While the database from CAPES/CNPq goes beyond the 90s, the first works we found started appearing around 1998 (see Figure 1). As research groups led by many of the early researchers (mostly with PhDs from other countries) started growing, more and more works appeared in the database.

Number of thesis/dissertations on the subjects published in the CAPES/CNPq database per year.

The peak of published works is around the 2010s, after when this number started to decrease, as, probably, the research around the topics of online media became more specialized. Thus, rather than belong to a single topic, it became pervasive among all topics. Figure 2 shows the general main topics of research and their connections from this database. The themes refer to the general period. We can see the strong themes are “journalism”, “culture” and “media”. The “political” theme, which marks the political communication field is one of the most connected ones, but it is not among the most used, suggesting that it exists as a more pervasive topic, rather than an independent one.

Network analysis of the most frequent themes from the Brazilian thesis and dissertations.

For the sake of simplicity, we divide the evolution of Brazilian research on online media into stages. The first one refers to the early debate on online media, then discussed under the label “new technologies of information and communication”. The second part discusses the consolidation of research on online media. The third part explores the new frontiers in research on online media. We will further explore the data focusing on this timeline.

6 The early debate

The first wave of research on online media happened at a time when they were still a novelty in Brazil. The creation of the internet in Brazil dates to 1992. At that time, the country was hosting the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (also known as Rio-92) in Rio de Janeiro. The National Education and Research Network (Rede Nacional de Ensino e Pesquisa, hereafter RNP) – an institution associated with the Ministry of Science and Technology – was responsible for providing the earlier backbone for the internet in Brazil. During its first years, the internet remained a pure academic network. Initially, the internet relied on telephone lines and the connection speed of the Brazilian internet was only 64 kb. This allowed Brazilian internet users to make very basic use of online resources. The opening of commercial internet occurred three years later, in 1995 (Rede Nacional de Ensino e Pesquisa 2022). Yet, in the following years, access to the internet remained precarious and restricted to the elite. According to World Bank data, in 2000 less than 3 percent of Brazilians had access to the internet (World Bank 2020). In 2005 this number has expanded to 20 percent of Brazilians.

As it happened elsewhere, the early debate on online media was characterized by the attempt to make sense of something radically new. For several decades, Brazilian communication studies had a clear idea about what their research subject was: The media were the print media, the radio, and the television. Although different in many substantial aspects, these media had an important characteristic in common. In all cases, there were technical apparatuses establishing a core distinction between the few who had the means for sending messages and those – much of the population – limited to receiving them. The media were mass media. By the mid-1990s, the certainty surrounding this idea was shaken by the emergence of a new set of technologies – known as “new technologies of information and communication”. The rise of online media – then referred to simply as the “internet” – presented a promise of change in this respect.

Early internet research in Brazil appeared in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and it was very pulverized among individual researchers from several universities in the country. During this time, the majority of the work was focused on discussing the differences between online media (the internet) and mass media (Lemos 1998; Silva 1999; Trivinho 1995; Vaz 2001), as well as emerging social phenomena from the digital, which mirrored some of the Anglo-Saxon work on the same concepts and theoretical and philosophical debates over the effects of technology on society (Trivinho 1995; Vaz 2001).

At that time, the debate on new technologies was largely concentrated in the United States. Not only was this country in the vanguard of the digital revolution, but it also became the undisputed leader of the world, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the communist regimes associated with it. A “new global order” emerged, under the influence of the neoliberal credo. Accordingly, neoliberal premises influenced much of the rhetoric about “new technologies”. They were supposed to erase the old order and, by doing so, provide the basis for something entirely new. Nicholas Negroponte (1996) expressed this perspective radically. According to him, the logic of the “atoms” would be replaced by another, made of “bits”. This project of societal dematerialization was consistent with the premises of global financial capitalism. Furthermore, the think tank Progress and Freedom Frontier (PFF) took the lead in describing the potential of new technologies to core neoliberal political principles in texts such as “Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age” (Mosco 2005). This view promoted a perspective focusing primarily on individual freedom from political institutions and the state (Mosco 2005). Other authors who were very influential in Brazil were Howard Rheingold (1993) and his concept of virtual communities; the notions of “cyberspace” (Barlow 1990); Negroponte and his “Being Digital” (1996) among others.

As it happened in other countries, these neoliberal ideas about how the internet should (and would) change the world exerted a tremendous influence in the Brazilian scholarly debate. However, they were, in a large measure, mediated by European, especially French authors (Daros 2021), such as Pierre Lévy (1999), Jean Baudrillard (1994), Michel Maffesoli (1988), and others. Both Lévy and Maffesoli provided very optimistic prospects with respect to the social changes coming in a near future. They approached these changes from different analytical angles, though. While Lévy considered the problem primarily from a technological perspective, Maffesoli adopted a more strictly sociological approach. In his opinion, the world was undergoing a process of re-enchantment, which would allow people to reconnect with one another in new and more meaningful ways. Another important author was the Spaniard Manuel Castells (1990) and his work on the impact of technology on culture on the trilogy “The Information Age” (1995–1997). Castells was also a highly important author for Brazilian research, particularly on his concept of “networked society”.

In these early days, the research in Brazil laid the foundation for the connection and evolution of the field. Fundamental concepts were “connected” and “online”, as a social and communicational phenomenon was also created. Brazilian researchers focused on more broad themes, as a way of exploring the connections between online media, hypertext, and literature (Palácios 1999; Pereira 2000); society (Couto 1997); cybersociality and virtual communities (Lemos 1997; Sá 2001); the impact on academic research (Palácios 1997).

The network of themes from this decade (1989–2000) shows these early concepts (Figure 3). Early research was also focusing on the application of these concepts brought from outside of Brazil in our context and Latin American context.

Early concepts from the published thesis/dissertations from 1989 to 2000.

7 The consolidation of research on online media

After the early 2000s and for the next ten years, research on online media flourished in Brazil, as did internet access. This consolidation resulted from different factors. To begin with, online media in the country has become more familiar and accessible. In 2002, Brazil had a little less than 10 percent of its population with internet access. By 2012, this number jumped to 49 percent and in 2020 this proportion jumped to 81 percent (Rede Nacional de Ensino e Pesquisa 2022). As online media became an essential part of the everyday life of a growing part of the Brazilian population, it did not make sense anymore to look at it as a “novelty”. In this context, generalist speculations regarding the impact of online media on different aspects of life were no longer relevant. Then, a new wave of more empirical studies focused on the specificities of the Brazilian digital environment took their place.

Second, the expansion of graduate programs in Brazil provided a unique environment for new research to emerge, and as people became increasingly interested in what was happening, online research also grew. In 1990, there were seven graduate programs in Brazil. Currently, there are more than fifty programs. This provided a powerful stimulus for the development and specialization of Brazilian online media research. Research on the broad concept of “cyberculture”, for example, was transformed in several areas. The type of research done also changed. Brazilian researchers started discussing the influence of online media with very theoretical and philosophical views. During this time, however, more and more empirical studies appeared, as well as new methodological approaches, and there was a shift in the direction, more toward the usage of empirical research and less about the theoretical debate. These studies also became more interdisciplinary, as data shows the presence of more themes from other fields.

Figure 4 shows how prolific these studies grew to be on our dataset. The key themes changed and became more specific. “Cyberculture” became more central, and the local discussion (of how these discussions impact “Brazil” was more prominent). The central theme of “politics” also became bigger, with more studies on society, campaigns, and elections.

Themes from the thesis/dissertations from CAPES/CNPq from 2001 to 2010.

Several early works discussed more specific phenomena from online media at the start of this trend. These early studies were the seed for the consolidation of what became several fields and subfields of online research. Some of the perspectives constructed during this period were:

Sociological approaches – The study of online groups, and the specification of the discussion on conversations, language, and interactions. The works on the fundamental notion of interactivity (Fragoso 2001; Primo 2001) created the basis for more specific works on social behavior (Lemos 2002), social platforms such as blogs (Carvalho 2002; Recuero 2001), and others. These studies are marked in Figure 4 by the keywords “society”, “communities”, “language”, “interactions”, “networks”, “blogs”, “Orkut” and so on.

Cultural approaches – the study of emerging cultural practices influenced by the digital medium. Studies in this group explore a variegated range of topics. A non-exhaustive list includes digital subcultures such as cyberpunk (Amaral 2003; Lemos 2001); fan cultures (Sá 2004); death and mourning online (Cunha Filho 2000); the effects on specific cultural groups (Sá 2000); and game cultures (Fragoso et al. 2017). These studies are marked in Figure 4 on keywords such as “culture”, “games”, “art”, “cyberspace”, “identity”, “practices”, and so on.

Psychological approaches – These studies were based on psychological views and discussions. In this field, we find studies about the relationships between online media and the body (Couto 1999; Sibilia 2002); and the effects of online media on privacy and surveillance (Vaz and Bruno 2003). These works appear with keywords such as “bodies”, “media”, “identity”, “subjectivity” and so on.

Political approaches – This field, influenced by political science, focused on variegated themes, such as activism (Antoun 2006), digital campaigns, deliberation studies (Maia 2008; Sampaio et al. 2011), democracy, and citizenship (Gomes 2002, 2008). These themes appear in Figure 4 as “political”, “citizenship”, “elections” and so on.

Journalism approaches – This group connects journalism studies and the development of the notion of online journalism (Antoun 2001; Palácios et al. 2002; Palácios and Mielniczuk 2002). These studies focus on the effects and connections of online media on journalism practices, audiences, and hypertext and hypermedia. Figure 4 shows these concepts as “journalism”, “web journalism”, “hypertext”, “convergence” and others.

Methodological approaches – Because empirical research began to grow, the discussion over the adaptation of existing methods or the creation and combination of different ones also started in the Brazilian body of work. Examples of these works are Amaral et al. (2008), Montardo and Passerino (2006), among others, and later, a compilation of these early works and methodological views. These methodological views appear mostly through their object, such as “communication technologies”, “practices” and “studies” in Figure 4. After 2010, the field became more pervasive in Communication Studies, as

Figure 1 shows. So, instead of a particular area, the studies became more specialized and part of all the other more traditional areas. Therefore, the number of thesis and dissertations on the keywords and themes start to fall, as the studies on journalism became studies on digital journalism and studies about culture, became also studies about “digital culture”. The keywords and themes expanded. The Working Groups that congregate these researchers became less about the theme and more about new approaches and “materialities”, while works with online objects expanded and spread to all other groups.

8 Online media and political communication

Political Communication is one of the most institutionalized research areas in Communication Studies in Brazil. Since 1992, a Working Group on Political Communication (WGPC) has been active in Compós. Historically, the WGPC has been very selective. Every year, roughly 30–40 papers are submitted to it, but only 10 of them are selected to be presented. It follows that the papers presented in the WGPC are not representative of the overall debate on political communication, but they present a certain aura of “distinction” concerning the debate on this issue. After all, Compós has been a central reference for the development of graduated Communication studies in Brazil. Moreover, the structure of Compós meetings allows the papers presented on them to be subject of intense debates. Each paper is debated for 1 h, and the participants in the working groups are supposed to read and comment their colleagues’ work. All papers presented at the Compós annual meeting since 2000 are available on the association’s website. At the same time, when we focus on the general dataset, used by this paper, we can see that the number of works published on online political communication appear around 2000 and grow until late 2010s, when decreases (Figure 5).

Online political communication thesis and dissertations (Series 2, orange) in relation to general online thesis and dissertations (Series 1, blue).

What does this sample tell us about Brazilian political communication scholars and social media? First, until the 2010s, online media remained a relatively irrelevant topic of research. From 2000 to 2009, for instance, only ten papers presented at the WGPC focused on online media. At that time, political communication was mainly associated with mass communication, especially journalism and political advertising. In the following ten years, however, the attention given to online media quadrupled, suggesting the institutionalization of online media as a subject of research for political communication scholars. Figure 5 shows how the proportion of works on online political communication grows among our dataset from the end of the 2000s and on. This is also evidence of how the area started to recognize itself as works became more focused on aspects of political communication and less general (such as “cyberculture”, for example).

Added to this, most of the papers presented from 2000 to 2009 have a clear exploratory character: They describe the advent of something essentially new. Examples include the rise of the internet as a virtual public sphere (Maia 2001), the relevance of using a civil conversation approach for analyzing the political debates on the internet (Marques 2006), and the rise of blogs as political vehicles (Aldé et al. 2006). Most of these initial studies share an optimistic view about the potential of online media to change the dynamics of political relations. These beliefs were associated with the belief that online media would result in the “liberation of the emission pole” (Lemos 2003; Sampaio et al. 2016), that is, that the agents who had previously been limited to the role of “receivers” of messages in the mass communications model would now be free to publish public content as well.

Many of the early studies in Brazilian political communication echo neoliberal premises about the online media’s potential to promote individual freedom, which has been decisive in the configuration of the early imaginary about the internet’s potential to change the world, as seen before. As a result, they portray digital technology as an essentially benign force that allows people to establish more free and authentic relationships with one another. One example is the idea that the internet would create the conditions for a virtual public sphere, in which everyone would be allowed to take part. Following the steps of Jurgen Habermas and authors like Castells (2000), Lévy (1999), and Papacharissi (2002), a solid tradition of research developed in Brazil, exploring the potential offered by the online media for providing the basis for a more inclusive and qualified (in terms of the exchange of arguments) political debate in Brazil. By being inclusive, the research considers the participatory advances and pitfalls provided by new media, expanding political action repertoires in civil society (Gomes 2008). Authors define “qualified” as the formation of conversational arenas between engaged citizens who exchange rational opinions and may lead to a deliberative system (Maia 2001; Marques 2006).

By 2010, this theoretical approach had evolved towards a “struggle for recognition” theoretical framework. While there is some continuity in the public sphere approach, there is also some discontinuity. Still, in this new approach, the focus of the research exchange shifts slightly from political debate to political activism. According to this approach, online media would provide a particularly important resource for marginalized groups in their search for visibility and recognition (Maia 2007). As an example, empirical research demonstrates how hearing impaired people appropriate digital forums and early social media, such as Orkut to create communities of personal expression of resilience and defense of sign language (Garcêz and Maia 2009).

A complementary approach focuses on the role of online media as tools for contentious politics. Here, the emphasis of the analysis lies more on political activism than on intellectual exchange. This approach gained ground in Brazil in the aftermath of the 2013 street protests that took place in several cities. Many studies have analyzed the Brazilian protests considering others demonstrations, happening elsewhere, such as the Occupy protests in the United States (Peruzzo 2013), the Indignados protests in Spain, and the Arab Spring protests, which took place in many Middle Eastern and North African countries (Gohn 2014), among many others. The works of Castells (2015) and Bennett and Segerberg (2013) became particularly influential in this respect. Drawing on Twitter data and connective action theory, Antoun and Falcão (2015) argued that June 2013 empowered the multitudes to narrate struggles and mobilize political action without the mediation of traditional political organizations, such as parties.

A third group of studies explores questions related to initiatives aiming to foster digital democracy. Strongly influenced by the neoliberal media governance and accountability agenda, these studies most often equate democracy with good practices intended to provide transparency of public and government institutions’ information for the benefit of the citizens. The empirical analysis surveyed digital democracy initiatives developed by the Brazilian federal government in 2017, highlighting that most of the projects provided public transparency to citizens, such as websites monitoring public expending (Almada et al. 2019). This is, probably the most institutionalized group of studies in Brazilian digital political communication studies, as it counts with a large project supported by the Brazilian science foundation CNPq, which reunites researchers working in several universities. Another example refers to the role performed by Cefor – a non-university research center, associated with the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies – in setting the agenda of digital government studies. It is worth noting that Brazilian studies on digital democracy usually focus on the online media associated with the political institutions, but rarely examine how these media affect or interact with the behavior of these political institutions. Two exceptions to that rule are Albuquerque and Martins (2010) and Santos Júnior and Albuquerque (2020), which discuss, respectively, how political considerations affect the manner in which political parties use their websites and how social media allows party factions to circumvent the authority of the parties’ leadership.

The optimistic attitude regarding the democratic potential of online media suffered a major setback in the late 2010s. The election of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right politician with anti-democratic agendas, to the presidency of Brazil, provided strong evidence against the premise that online media improved the quality of democracy. After all, Bolsonaro used social media to spread misinformation during his 2018 election campaign. The research is focused on two main topics: (a) the use of digital platforms by the far-right to spread disinformation and hate speech and mobilize supporters to challenge the democratic order; and (b) the challenges that the process of platformization poses to the survival and business models of journalism. The first strand of research is a major topic of attention in Brazilian scholarship, at least ever since the parliamentary coup against President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 (Santos Junior 2019), and became increasingly important in the aftermath of Jair Messias Bolsonaro’s election in 2018. Particularly, Bolsonaro’s victory challenged the political communication paradigm in Brazil since the far-right candidate had scarce time of political propaganda on television but compensated with an enormous capacity for capturing attention and engaging his electorate on social media and conversation apps, such as WhatsApp (Evangelista and Bruno 2019). The second strand of study is dedicated to understanding the impacts of big tech platforms on the advertising-based financial model of journalism, both through studying innovations in alternative journalism (Becker and Waltz 2017) and investigating the challenges to how precarious working conditions for journalists became (Grohmann 2020).

9 Conclusion

In this paper, we reconstruct a portion of the history and origins of the online communication research tradition in Brazil, as well as how it influenced the study of political communication in the country. We demonstrated how different traditions were created from an initial French concept matrix and then expanded with other North American and European ideas. We discussed how the debate on online media evolved along three different stages. The first moment corresponds to a time when online media was still a novelty, accessible only to a few. In this phase, the Brazilian discussion on online media consisted mostly of speculations about their potential for changing society. Then, the concept of “cyberculture” was central to Brazilian research. The second moment corresponds to the consolidation of research on online media. The research has a more empirical orientation, and a more specialized nature. At that time, different approaches to online media developed: sociological, cultural, psychological, political, journalistic, and methodological.

The last section focused on a specific subfield of Communication studies: Political Communication. We explored how online media came to dominate the attention of Brazilian political communication scholars, especially in the 2010s. We also discussed how attitudes toward online media have shifted. Initially, these studies echoed optimistic expectations about the role of these media as a democratizing factor. Following the massive street protests in several Brazilian cities in 2013, subsequent research concentrated on how online media became a tool for contentious politics. Finally, the election of Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency sparked a wave of skepticism about the political impact of the digital, with Brazilian scholars increasingly emphasizing the dangers that social media pose to democracy as disinformation disseminators.

What challenges does the future present to the Brazilian scholars? In a time when the unipolar order structured around the United States growingly cedes place to a more multipolar world, Brazilian researchers need to find their own voice in the international scholarly arena. To achieve this goal, they must significantly improve their research networks, enhancing their ability to set their research agenda in a more active manner. Recently, a group of scholars working from different universities in Brazil and abroad took an important step in this direction. They had a major research project, focusing on the challenges that a globalized world present to the exercise of information sovereignty approved by Brazil’s funding agency CNPq, as a part of its Institutos Nacionais de Ciência e Tecnologia (INCT, National Institutes for Science and Technology, in English) program.

It is worthy to note that this study has an important limitation. Much of the early debate on online media in Brazil cannot be accessed through databases. We tried to overcome this problem through the resource to secondary literature and, when it was possible, direct contact with the authors of the pioneer papers on online media. However, we are aware that this problem may result in significant ellipses in our argument.

Funding source: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico

Award Identifier / Grant number: 302489/2022-3

Award Identifier / Grant number: 305556/2022-3

Award Identifier / Grant number: 406504/2022-9

Funding source: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Rio Grande do Sul

Award Identifier / Grant number: 19/2551-0000688-8

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (302489/2022-3, 305556/2022-3, 406504/2022-9) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Rio Grande do Sul (19/2551-0000688-8).

References

Albuquerque, Afonso de & Martins, Adriane Figueirola. 2010. Apontamentos para um modelo de análise dos partidos na Web. Proceedings of the 19th Compós meeting. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso & Camilla Quesada Tavares. 2021. Corporatism, fractionalization and state interventionism: The development of communication studies in Brazil. Publizistik 66(1). 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-020-00622-3.Search in Google Scholar

Aldé, Alessandra, Juliana Escobar & Viktor Chagas. 2006. A febre dos blogs de política [The fever of political blogs]. 15th Compós Meeting. Available at: https://proceedings.science/compos/compos-2006/papers/a-febre-dos-blogs-de-politica.Search in Google Scholar

Almada, Maria Paula, Wilson Gomes, Rodrigo Carreiro & Samuel Barros. 2019. Democracia digital no Brasil: Obrigação legal, pressão política e viabilidade tecnológica [Digital democracy in Brazil, legal obligation, political pressure, and technological viability]. Matrizes 13(3). 161–181. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v13i3p161-181.Search in Google Scholar

Amaral, Adriana R. 2003. Minority report: Rastreando as origens do cyberpunk [Minority report: Tracking the origins of cyberpunk]. BOCC. Biblioteca On-line de Ciências da Comunicação 1. 01–12.Search in Google Scholar

Amaral, Adriana, Geórgia Natal & Luciana Viana. 2008. Netnografia como aporte metodológico da pesquisa em comunicação digital [Netnography as a methodological device in the research on digital communication]. Famecos 35. 34–40.Search in Google Scholar

André, Lemos & Marcos Palácios (eds.). 2000. Janelas do ciberespaço: Comunicação e cibercultura. Porto Alegre: Sulina.Search in Google Scholar

Antoun, Henrique. 2001. Jornalismo e ativismo na hipermídia: Em que se pode reconhecer a novamídia. Revista Famecos 8(16). 135–148.10.15448/1980-3729.2001.16.3144Search in Google Scholar

Antoun, Henrique. 2006. Mobilidade e Governabilidade nas Redes Interativas de Comunicação Distribuída [Mobility and governance in interative networks of distributed communication]. Razón y Palabra 49. 1–18.Search in Google Scholar

Antoun, Henrique & Paula Falcão. 2015. As jornadas de 2013: O# vemprarua no Brasil. Esferas 7. 143–151.10.31501/esf.v2i7.6953Search in Google Scholar

Barlow, John P. 1990. Crime and puzzlement. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/pt-br/pages/crime-and-puzzlement (retrieved 8 October, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and simulation. Chicago: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9904Search in Google Scholar

Becker, Beatriz & Igor Waltz. 2017. Mapping journalistic startups in Brazil: An exploratory study. Media and Communication 13. 113–135.10.1108/S2050-206020170000013012Search in Google Scholar

Beltran, Luis R. 1976. Alien promises, objects, and methods in Latin American communication research. Communication Research 3(2). 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365027600300202.Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, K. 2014. The “butler” syndrome: Academic culture on the semiperiphery. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 69. 155–171.Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, W. Lance & Alexandra Segerberg. 2013. The logic of connective action. In Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139198752Search in Google Scholar

Boyd-Barrett, Oliver. 2018. Cultural imperialism and globalization. In Oxford research Encyclopedia of communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.678Search in Google Scholar

Carvalho, Rosa Meire. 2002. Diários Íntimos na Era Digital. Diários Públicos, Mundos Privados [Intimate diaries in the digital era. Public diaries, private worlds]. Disponível no website do Grupo de Ciberspesquisa da Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade Federal da Bahia, em (02/08/2002).Search in Google Scholar

Castells, Manuel. 2000. The rise of the network society: The information age: Economy, society and culture. John Wiley & Sons.Search in Google Scholar

Castells, Manuel. 2015. Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age, 2nd edn. London: Polity.10.7312/blau17412-091Search in Google Scholar

Couto, Edvaldo S. 1997. A Sociedade Tecnológica. [The Technological Society]. Vide Verso 2. 37–38.Search in Google Scholar

Couto, Edvaldo S. 1999. Estética e virtualização do corpo [Aesthetic and body virtualization]. Revista Fronteiras 1. 63–76.Search in Google Scholar

Cunha Filho, Paulo C. 2000. Cibercepção da morte, luto virtual e misticismo tecnológico [Cyberperception of death, virtual grief, and technological mysticism]. 9th Compós Meeting. Available in https://proceedings.science/compos/compos-2000/papers/cibercepcao-da-morte–luto-virtual-e-misticismo-tecnologico?lang=pt-br (Acesso em 23 nov. 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Daros, Otavio. 2021. French theoretical and methodological influences on Brazilian journalism research. Media, Culture & Society 43(8). 1553–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443721999936.Search in Google Scholar

Demeter, Marton, Manuel Goyanes, Federico Navarro, Judith Mihalik & Claudia Mellado. 2022. Rethinking de-westernization in communication studies: The Ibero-American movement in international publishing. International Journal of Communication 16. 3027–3046.Search in Google Scholar

Evangelista, Rafael & Fernanda Bruno. 2019. WhatsApp and political instability in Brazil: Targeted messages and political radicalisation. Internet Policy Review 8(4). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1434.Search in Google Scholar

Fragoso, Suely. 2001. De interações e interatividade. Revista Fronteiras–estudos midiáticos 3(1). 83–96.Search in Google Scholar

Fragoso, Suely, Rebeca R. Rebs, Breno M. Reis, Luiza Santos, Dennis Messa, Mariana Amaro & Mayara Caetano. 2017. Estudos de Games na área da Comunicação no Brasil: Tendências no período 2000–2014. Verso e Reverso 31. 2–13.10.4013/ver.2016.31.76.01Search in Google Scholar

Ganter, Sarah A. & Félix Ortega. 2019. The invisibility of Latin American scholarship in European media and communication studies: Challenges and opportunities of de-westernization and academic cosmopolitanism. International Journal of Communication 13. 68–91.Search in Google Scholar

Garcêz, Regiane L. & Rousiley Maia. 2009. Lutas por reconhecimento dos surdos na Internet: Efeitos políticos do testemunho [Struggle for recognition of deafs on internet: Political effects of testemonies]. Revista de Sociologia e Política 17. 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-44782009000300007.Search in Google Scholar

Glander, Timothy. 2000. Origins of mass communication research during the American Cold War: Educational effects and contemporary implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Gohn, Maria G. 2014. Manifestações de junho de 2013 no Brasil e praças dos indignados no mundo [June 2013 Protest in Brazil, and the indignados’ squares across the world]. Petrópolis: Vozes.Search in Google Scholar

Golding, Peter. 2019. Media Studies in the UK. Publizistik 64(4). 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-019-00518-x.Search in Google Scholar

Gomes, Wilson S. 2002. Internet, Censura e Liberdade [Internet, Censorship, and Freedom]. In Raquel Paiva (ed.), Ética, Cidadania e Imprensa [Ethics, Citizenship, and the Press], 133–164. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad.Search in Google Scholar

Gomes, Wilson S. 2008. Internet e participação política em sociedades democráticas [Internet and political participation in democratic societies]. Revista Famecos 12(27). 58–78. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-3729.2005.27.3323.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, André. 2002. Cibercultura. Porto Alegre: Sulina.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, André C. 2003. Cibercultura: Alguns pontos para compreender a nossa época [Cyberculture: Some points to understand our time]. In Paulo C. Cunha Filho (ed.), Olhares sobre a cibercultura [Perspectives on cyberculture]. Sulina: Porto Alegre.Search in Google Scholar

Grohmann, Rafael. 2020. Plataformização do trabalho: entre dataficação, financeirização e racionalidade neoliberal. Eptic 22(1). 106–122.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, André. 1997. Cibersocialidade [Cybersociality]. Logos 6. 15–19.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, André. 1998. O Imaginário da Cibercultura [The cyberculture imaginary]. São Paulo em Perspectiva 12(4). 46–53.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, André. 2001. Cyberpunk. Apropriação, desvio e despesa improdutiva. Revista Famecos 8(15). 44–56.10.15448/1980-3729.2001.15.3119Search in Google Scholar

Lévy, Pierre. 1999. Collective intelligence: Mankind’s emerging world in cyberspace. New York: Basic Books.Search in Google Scholar

Lopez-Escobar, Esteban & Manuel M. Algarra. 2017. Communication teaching and research in Spain: The calm and the storm. Publizistik 62(1). 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-016-0306-4.Search in Google Scholar

Maffesoli, Michel. 1988. Le temps de tribus [Time of tribes]. Paris: Méridiens-Klincksieck.Search in Google Scholar

Maia, Rousiley C. M. 2001. Democracia e a internet como esfera pública virtual: Aproximando as condições do discurso e da deliberação [Democracy and internet as a virtual public sphere. Approaching the conditions for discourse and deliberation]. 10th Compós Meeting, Brasília. https://proceedings.science/compos/compos-2001/papers/democracia-e-a-internet-como-esfera-publica-virtual–aproximando-as-condicoes-do-discurso-e-da-deliberacao.Search in Google Scholar

Maia, Rousiley C. M. 2007. Deliberative politics and typology of public sphere. Studies in Communication 1. 69–102.Search in Google Scholar

Maia, Rousiley C. M. 2008. Redes cívicas e internet: Efeitos democráticos do associativismo [Civic networks and internet: democratic effects of associativism]. Logos 14. 43–62.Search in Google Scholar

Marques, Francisco Jamil. 2006. Debates políticos na internet: A perspectiva da conversação civil. Opinião Pública 12(1). 164–187.10.1590/S0104-62762006000100007Search in Google Scholar

Mellado, Claudia. 2010. La influencia de CIESPAL en la formación del periodista latinoamericano. Una revisión crítica [The influence of CIESPAL on the formation of the Latin-American journalist. A critical revision]. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 16. 307–318.Search in Google Scholar

Montardo, Sandra Portella & Liliana Maria Passerino. 2006. Estudo dos blogs a partir da netnografia: Possibilidades e limitações [Studying blogs through netnography: Possibilities and limitations]. CINTED-UFRGS: Novas Tecnologias na Educaçãov 4(2). https://doi.org/10.22456/1679-1916.14173.Search in Google Scholar

Mosco, Vincent. 2005. The digital sublime: Myth, power, and cyberspace. Boston: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2433.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Negroponte, Nicolas. 1996. Being digital. New York: Vintage Books.Search in Google Scholar

Oliveira, Thaiane M., Francisco P. J. Marques, Augusto V. Leão, Afonso de Albuquerque, José Luiz A. Prado, Rafael Grohmann, Anne Clinio, Denise Cogo & Liziane Guazina. 2021. Towards an inclusive agenda of open science for communication research: A Latin American approach. Journal of Communication 71(5). 785–802.Search in Google Scholar

Palácios, Marcos. 1997. Impactos e Efeitos da Internet Sobre A Comunidade Acadêmica [Impacts and effects of internet on the academic community]. Tendências 2. 58–67.Search in Google Scholar

Palácios, Marcos. 1999. Hipertexto, Fechamento e o uso do conceito de não-linearidade discursiva [Hypertext, closure, and the use of the concept of discoursive non-linearity]. Lugar Comum 8. 111–121.Search in Google Scholar

Palácios, Marcos, Luciana Mielniczuk, Suzana Barbosa, Beatriz Ribas & Sandra Narita. 2002. Um Mapeamento de características e tendências no jornalismo online brasileiro e português [Mapping characteristics and trends in the Brazilian and Portuguese online journalism]. Comunicarte 1(2). 160–171.Search in Google Scholar

Palácios, Marcos & Luciana Mielniczuk. 2002. Considerações para um estudo sobre o formato da notícia na Web: o link como elemento paratextual [Considerations for a study on the news form on web: The link as paratextual element]. Pauta Geral 9(4). 33–50.Search in Google Scholar

Papacharissi, Zizi. 2002. The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society 4(1). 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614440222226244.Search in Google Scholar

Pereira, Vinicius A. 2000. Dinâmicas Contemporâneas de Subjetivação: Metamorfose das Ciências e Hipertexto [Contemporary dynamics of subjetivation: Metamorphosis of Science and Hypertext]. Revista Fronteira 2(1). 151–170.Search in Google Scholar

Peruzzo, Cicilia. 2013. Movimentos sociais, redes virtuais e mídia alternativa no junho em que “o gigante acordou” [Social movements, virtual networks, and alternative media in the June when “the giant woke up”]. Matrizes 7(2). 73–93. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v7i2p73-93.Search in Google Scholar

Primo, Alex. 2001. Ferramentas de Interação em ambientes educacionais mediados por computador. Educação 24(44). 127–149.Search in Google Scholar

Recuero, Raquel. 2001. Comunidades Virtuais – Uma abordagem teórica. Ecos Revista, Pelotas/RS 5(2). 109–126.Search in Google Scholar

Rede Nacional de Ensino e Pesquisa. 2022. The evolution of internet in Brazil. https://www.rnp.br/en/news/evolution-internet-brazil (accessed 4 November 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Rheingold, Howard. 1993. Daily life in cyberspace. The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. New York: HarperCollins.Search in Google Scholar

Sá, Simone A. P. 2000. O Samba em Rede – Comunidades Virtuais e Carnaval carioca [Samba in network – virtual communities and Carioca Carnival]. Lugar Comum 1. 107–136.Search in Google Scholar

Sá, Simone A. P. 2001. Utopias Comunais em Rede: Discutindo a noção de comunidade virtual. Revista Fronteiras, São Leopoldo-Rio Grande do |Sul.Search in Google Scholar

Sá, Simone A. P. 2004. O que os fãs de Arquivo X podem nos revelar sobre a comunicação mediada por computador? [What can the X Files fans tell us about computer-mediated communication?]. In Simone A. P. Sá & Ana L. Enne (eds.), Prazeres Digitais: Computadores, entretenimento e sociabilidade. [Digital Pleasures: Computers, entertainment, and sociability], 7–26. Rio de Janeiro: E-Papers.Search in Google Scholar

Sampaio, Rafael C., Rousiley C. M. Maia & Francisco P. J. Marques. 2011. Participation and deliberation on the internet: A case study on digital participatory budgeting in Belo Horizonte. Journal of Community Informatics 7. 1–22.10.15353/joci.v7i1-2.2561Search in Google Scholar

Sampaio, Rafael C., Raquel C. Bragatto & Maria A. Nicolás. 2016. A construção do campo de internet e política: Análise dos artigos brasileiros apresentados entre 2000 e 2014 [Building the internet and politics field: Analysis of the Brazilian articles published between 2000 and 2014]. Revista Brasileira de Ciencia Poitica 21. 285–320. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-335220162108.Search in Google Scholar

Santos Junior, M. 2019. Vaipracuba!: a gênese das redes de direita no Facebook [GotoCuba! The genesis of the rightwing networks on Facebook]. Curitiba: Appris.Search in Google Scholar

Santos Junior, Marcelo & Afonso Albuquerque. 2020. PSOL versus PSOL: Facções, partidos e mídias digitais. Opinião Pública 26(1). 98–126.10.1590/1807-0191202026198Search in Google Scholar

Sibilia, Paula. 2002. O Homem Pós-Orgânico: Corpo, subjetividade e tecnologias digitais [The post-organic man: Body, subjectivity, and technologies], vol 1, p. 232. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará.Search in Google Scholar

Silva, Juremir M. 1999. Internet, Naviguer: Rêve de Navigation Ou Navigation de Rêve? [Internet, navigate: Dream of navigation or navigation of a dream?]. Cultures en mouvement 15. 28–29.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John. 1997. Latin America television: A global view. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Suzina, Ana C. 2021. English as lingua franca. Or the sterilisation of scientific work. Media, Culture & Society 43(1). 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720957906.Search in Google Scholar

Tota, Antonio Pedro. 2010. The seduction of Brazil: The americanization of Brazil during world war II. Austin: University of Texas Press.10.7560/719934Search in Google Scholar

Trivinho, Eugênio. 1995. À luz dos espectros expressivos: A obliteração das massas na autora do cyberspace [In the light of expressive spectres: The obliteration of masses in the aurora of cyberspace]. Atrator Estranho 13. 21–36.Search in Google Scholar

Vaz, Paulo. 2001. Mediação e tecnologia, 16, 45–58. Porto Alegre: Revista FAMECOS.10.15448/1980-3729.2001.16.3137Search in Google Scholar

Vaz, Paulo & Fernanda Bruno. 2003. Types of self-surveillance: From abnormality to individuals ‘at risk’. Surveillance and Society 1(3). 10–20. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v1i3.3341.Search in Google Scholar

Waisbord, Silvio & Claudia Mellado. 2014. De-westernizing communication studies: A reassessment. Communication Theory 24(4). 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12044.Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2020. Individuals using the internet (% of population). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=BR (accessed 4 November 2022).Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Essay

- Global streaming media, European green consumption, perception of China before & after COVID-19 and online memes on corruption

- Original Articles

- Streaming media business strategies and audience-centered practices: a comparative study of Netflix and Tencent Video

- What influences public support for plastic waste control policies and green consumption? Evidence from a multilevel analysis of survey data from 27 European countries

- News exposure and Americans’ perceptions of China in 2019 and 2021

- “We are only to Appear to be Fighting Corruption…We can’t even Bite”: online memetic anti-corruption discourse in the Ghanaian media

- Review Essay

- Online communication studies in Brazil: origins and state of the art

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- The “computational turn”: an “interdisciplinary turn”? A systematic review of text as data approaches in journalism studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Essay

- Global streaming media, European green consumption, perception of China before & after COVID-19 and online memes on corruption

- Original Articles

- Streaming media business strategies and audience-centered practices: a comparative study of Netflix and Tencent Video

- What influences public support for plastic waste control policies and green consumption? Evidence from a multilevel analysis of survey data from 27 European countries

- News exposure and Americans’ perceptions of China in 2019 and 2021

- “We are only to Appear to be Fighting Corruption…We can’t even Bite”: online memetic anti-corruption discourse in the Ghanaian media

- Review Essay

- Online communication studies in Brazil: origins and state of the art

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- The “computational turn”: an “interdisciplinary turn”? A systematic review of text as data approaches in journalism studies