Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

-

Tasmia Irshad

, Muhammad Imran Din

Abstract

Three new inorganic–organic hybrid nanocomposites (In–WO3@rGO, Mo–WO3@rGO, and Mn–WO4@rGO) were synthesized by hydrothermal method and applied for recoverable and efficacious ODS process of real oil. The physicochemical analysis of novel nanocatalysts was conducted by various techniques, i.e., powder X-ray diffraction, fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. XRD and SEM analyses depicted that the nanoparticles (In–WO3, Mn–WO4, and Mo–WO3) were well embellished on the exterior of reduced GO with an amazing morphology, having a crystallite size of less than 40 nm. The catalytic activity of nanocomposites was scrutinized for real fuel (diesel and kerosene) and model fuel (DBT) using the radical initiator mechanism of the ODS pathway. Excellent efficiency can be obtained under optimized conditions using 0.1 g catalyst, 1 mL oxidant (H2O2), and100 ppm DBT at 40°C with a time duration of 180 min. Various factors such as time, DBT concentration, catalyst amount, oxidant amount, and temperature that affect catalytic activity directly or indirectly were also studied. A pseudo-first-order kinetics model was followed, and due to spontaneous reaction, a negative value of ΔG was observed with an activation energy of 6.54 kJ/mol for Mo–WO3@rGO, which is lower than that of the other two hybrids. The synthesized nanohybrids showed remarkable durability and recovery up to five times for the ODS process without significant change in proficiency.

1 Introduction

With the increasing world population, the sulfur content in the atmosphere is increasing day by day because of the emission of gases as a result of excessive human activities such as transportation, electricity, and construction of materials. This increase in sulfur-containing particles causes air pollution and is depleting our environment. The issue of the environment is becoming more severe day by day due to industrialization, urbanization, etc., which are negatively affecting our ecosystem. According to UNO legislation, the limit of sulfur content in HCSs is not to be more than 10 ppm for gasoline and 15 ppm for diesel. Fuel is one of the important sources of energy that is essential for human growth and development. Hence, desulfurization has become one of the worldwide concerns [1,2]. The sulfur contents in fuel are generally classified as disulfides, thiophenes, BT, DBT, mercaptans, etc., which convert sulfur in fuel into SO x after combustion [3]. In addition, it causes acid rain that contributes to the occurrence of London smog (sulfurous smog), which causes headaches and eye irritation; however, long-term exposure may ultimately cause death. Nowadays, in fuel refineries, the main challenge is the removal of sulfur content and its compounds because of strict legislation on environmental remediation [4]. Hydrodesulfurization was the traditional desulfurization technology, which requires hydrogen under high temperature and pressure to eliminate cyclic compounds, i.e., DBT, BT, etc. Therefore, an efficient desulfurization technology needs to be developed that will remove sulfur compounds from fuel to achieve environmental sustainability [5]. Technologies that have been proposed for fuel oil desulfurization, such as adsorptive desulfurization [6], extractive desulfurization [7], bio-desulfurization, and oxidative desulfurization (ODS) [8], are under development [9]. Among all, ODS is gaining colossal attention for the removal of sulfur due to its low cost, higher adaptability for the selectivity of aromatic compounds, high efficiency, and eco-friendly behavior. The scientific community is paying top-tier importance to ODS, as it is the best methodology to liberate sulfur-based ring substances from fluid. This technology requires an oxidative reaction to convert organo-sulfur compounds into sulfones and sulfoxides in the presence of oxidizing agents, such as H2O2, under the influence of a suitable catalyst. Then, oxidized compounds are separated by using polar solvents, such as acetonitrile (extractant), through a solvent extraction technique [10]. Over time, this method has evolved into a more beneficial and remarkably cost-effective process, as it now demands microscopic quantities of oxidants and elementary equipment or conditions.

In the past, oxidative catalysis was used in various fields such as water splitting, desulfurization of oil, and pollutant degradation, etc. [11]. Desulfurization assisted by ODS is an easily accessible process for the removal of aromatic sulfur compounds from fuel oil owing to mild operating conditions with no consumption of H2 [12]. ODS is a two-step process: oxidation followed by elimination of sulfones and sulfoxide through extraction using the extractant MeCN. Among the recently used catalysts for ODS, the newly emerging class of modern material POM@MOF-based composites [13], such as supported metal oxides, titanate nanotubes [14], and phase transfer materials, are used as the best choice of catalyst for deep oil desulfurization.

TBA-Si2W18Mn4@SAB with CH3COOH/H2O2 as an oxidizing agent was found to be an excellent catalyst for ODS, having 97% removal of sulfur content from gasoline following a first-order reaction. The oxidation reactivity of sulfur compounds is designated in decreasing order as DBT > BT > Th [15]. The nanocomposites for the efficient removal of DBT using Bi2WO6@rGo and CuWO4@rGo catalysts obtained 90% efficiency under optimal reaction conditions via ODS. The kinetics were a pseudo-first-order reaction with optimum energies of 16.91 and 14.57 kJ/mol [16]. (Gly)3PMo12O40@MnFe2O4 hybrid nanocomposites were used in the CAT-ODS reaction for the withdrawal of dangerous organo-sulfur contents from model fuel oil and gasoline. The removal efficiency was 95% under optimized conditions at a temperature of 35°C with a contact time of 1 h following the kinetics of a pseudo-first-order reaction model. The substrates such as DBT, BT, and Th were catalytically removed with efficiency yields of 98.3, 97.6, and 96.4%, respectively [17]. MOF-derived nanocomposites were used as an efficient catalyst for ODS and ODN.

PTA@H2N-MIL-101-Cr showed excellent efficiency for the removal of DBT from n-heptane in the presence of MeCN and H2O2 with high reaction rates. Among DBT, 4,6-DMBT, and BT, DBT shows the highest efficiency of 99.6%, followed by 88.2 and 70.5%, respectively [18]. CoW(20)/rGO hybrid nanocomposites were utilized as an efficient catalyst for impressive ODS performance for the model as well as real fuel in the manifestation of hydrogen peroxide [19]. Recent studies show that the rGO-based catalyst for the removal of sulfur compounds effectively contributes to cleaner energy production and a safer environment. Moreover, the importance of hybrid Ni/Fe3O4/rGO is its large surface area and electrical conductivity that facilitate the effective adsorption and activation of sulfur-containing compounds [20]. This catalyst showed excellent sulfur removal efficiency in model diesel fuel, surpassing traditional catalysts in terms of activity and durability. Another heterogeneous catalyst, FeW11V@CTAB-MMT, used for ODS of gasoline following pseudo-first-order kinetics, has the best removal efficiency of DBT, BT, and Th with more than 97% efficiency at 35°C after 1 h [21]. This catalyst is perfectly used to remove hazardous sulfur compounds from gasoline. Homogeneous and heterogeneous polyoxometalates are used as efficient catalysts for the ODS process of fuel by removing refractory sulfur compounds, e.g., DBT and BT, under mild reaction conditions but with high efficacy [22]. The heterogeneous catalyst Fe6W18O70 ⊂ CuFe2O4 exhibited an extraordinarily high efficiency with the removal of thiophene 98%, DBT 99%, and BT 99% when used in ultra-deep ODS of real gasoline and simulated fuel. The reaction occurs under optimized conditions of a temperature of 35°C with a contact time of 1 h and shows an oxidation reaction efficiency of 95% [23].

In recent years, carbon materials, particularly graphene oxide, have been utilized as catalyst support for ODS because of their special surface properties, unique interlayer structure, and extremely large surface area. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) is a two-dimensional, crystalline allotrope possessing a six-membered ring, lattice structure made from pure carbon atom, sp2 hybridization, with unique electrical and thermal properties [24]. A high surface area results in more active sites for the catalytic reaction, allowing effective adsorption of sulfur-containing compounds. While rGO-based nanocomposites play a vital function in this process, immense research concerning the ODS of oil by hybrid materials needs to be paid attention to. Researchers have reported rGO-supported TM-modified catalysts, mesoporous silica, and MOF@POM hybrid materials for efficient and green ODS. 2D-GO not only possesses great thermal and electrical properties but also contains functional groups having oxygen that play an essential role in chemical modifications. These hybrid nanocomposites have found applications in diverse fields of interest, playing a decisive role in advancing modernization breakthroughs and facilitating innovation in the realms of energy and environment. As a result, their utilization spans various sectors within these environmental domains [24]. Moreover, owing to rGO, chemical stability is enhanced, ensures long-term stability of catalysts, and reduces operational cost.

The current work includes fabrication of Mo–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and In–WO3@rGO nanocomposites (recoverable, TM-free) and their catalytic testing for the ODS process for oils. The characterization of the prepared materials is performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), XRD (powder X-ray diffractometer), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), IR spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) study. Various parameters, including the concentration of sulfur content, time interval of absorption–desorption equilibrium, temperature, and catalyst concentration, were investigated to regulate the ODS process. Furthermore, the recovery of the catalyst, mechanism and testing of oil were inspected, and detailed insights into these aspects are provided in the subsequent analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

KMnO4 99.9%, H2SO4 98%, graphite powder, H2O2 30% by weight, prepared catalysts (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), Na2WO4·2H2O 99%, and dibenzothiophene (DBT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., and indium sulfate [In2(SO4)3], manganese acetate C4H14MnO8, and ammonium molybdate 4-hydrate[(NH4)3 Mo7O24·4H2O] were acquired from Merck.

2.2 Production of GO, exfoliated GO, and reduced GO

rGO was prepared following an earlier method with a few minor modifications [24]. An ice bath was used for half an hour to maintain the temperature <5°C while mixing continuously, and 4 g of powdered graphite was weighed and placed in a beaker with 100 mL of pure sulfuric acid. The main purpose of using an ice bath was to maintain temperature to avoid thermal degradation of the GO precursor material, as high temperature may lead to incomplete synthesis or degradation of the desired product. Thus, cooling the reaction media helps to obtain better control of reaction conditions. The mixture was constantly stirred after introducing 12 g of KMnO4 while keeping the temperature below 10°C in a cold pot. Later, it was diluted by the addition of 100 mL of deionized H2O with constant shaking. H2O2 (30 wt%) was added to the mixture to reduce the remaining KMnO4. Then, screening was completed, the deposit was separated by filtration, and it was rinsed with 5% aqueous solution of HCl and water till the pH remained 6 to further guarantee that ions were eradicated. Hydrogen peroxide played a vital role as an oxidizing agent, often used to oxidize graphene to GO by initiating oxygen-containing groups, i.e., hydroxyl groups, epoxide to the graphene sheet, and transforming sp2 carbon atoms to sp3 hybrid form. Dehydration of the GO product was carried out at 45°C for 1 day in a furnace.

Exfoliation of the product was performed by dissolution of 2 g of GO in 500 mL of deionized water with constant stirring for 6 h. As unexfoliated nanocomposite piped out during the reaction, the synthesized XGO was then dehydrated for a day at 45°C, and centrifugation and ultrasonication were performed to remove any unexfoliated GO. XGO (1 g) was introduced to 0.5 L of distilled water to synthesize rGO by heating and stirring at 90°C for 4 days. The prepared rGO at 120°C was dried in an oven.

2.3 Synthesis of In–WO3, Mn–WO4, and Mo–WO3, In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO

For the preparation of In–WO3, 1 g of Na2WO4 and 1 g of In2(SO4)3 were mixed in a 250 mL beaker containing 100 mL of deionized water. The mixture was stirred for 25–30 min. After agitation, sodium borohydride (NaBH4) was added to the beaker containing the previous mixture till the formation of bubbles stopped. Later, it was placed in a Teflon-assisted steam vessel/cylinder and kept in a furnace for 6 h at 155°C. The same procedure was adopted for Mn–WO4 and Mo–WO3 using manganese and molybdenum salts, i.e., manganese acetate and ammonium molybdate, respectively. A combination of TMs (indium, manganese, and molybdenum) supported on rGO was created by incorporating ∼20% TMs-WO3 onto ∼80% rGO. The fabrication was done using an autoclave at 150°C for 7–8 h. These parameters of time and temperature conditioning are very crucial as this temperature range allows the uniformity of composite structures and also increases the diffusion of the precursor. Moreover, all MOs required a specific range of optimal temperatures for the synthesis of the desired hybrid oxides. In addition, the duration of the autoclave gives the overall reaction time and extent of interaction between rGO sheets and TMs-WO3. These two factors depict the overall morphology, phase composition, and crystallinity of nanohybrids, and their adjustments control the synthesis mechanism. After filtration, the products (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) were heated for 6 h at 300°C.

2.4 Characterization techniques

The prepared materials (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) were subjected to characterization using multiple techniques, such as FT-IR spectroscopy using IR-TRACER-100, a wavelength of 4,000–400/cm with a scanning speed of 15/cm; powder X-ray diffraction of Cu-kα (0.154 nm or 1.54 Å) with a range of 5°–70° and a scanning speed of 2°/min; SEM for morphology was performed using NOVA NANO together with EDX and TGA under an inert atmosphere in the range of 400–800°C. Furthermore, the properties of fuel were assessed using PETRA-XRF, a total sulfur tester ASTM D-4294, an H2O content analyzer (China PT-D4006-8929A, volume %, ASTM D-4006), a hydrometer (density analyzer) at 15.6°C @gmol−1, ASTM D-1298), and a Distillation Tester (ASTM D-86, PAC, PMD 110).

2.5 ODS procedure

Catalytic testing was inspected using 1,000 ppm DBT in n-hexane and 40 mL of an extractant using 0.1 g of the catalyst (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) under ideal conditions, and the conditions for the catalytic reaction were optimized to achieve the best possible performance. The mixture (model fuel, extractant, and catalyst) was poured into a cone-shaped flask and kept in the absence of light for 15 min to obtain as adsorption–desorption stability curve. Later on, 1 mL of 30 wt% oxidant H2O2 was added to the flask. The reaction converts sulfur compounds in model fuel to sulfones. Then, sulfoxides were liberated in a polar medium containing extractants; thus, other rested sulfur in the non-polar medium can be calculated using an ultraviolet-visible spectrometer with λ max = 285 nm (transition from n to π*). Moreover, a total sulfur analyzer (PETRA XRF) was utilized to measure the amount of rested sulfur in the liquid phase at various time spans. The effectiveness of model fuel elimination could be determined using the mathematical equation:

Here, C f is the final amount of DBT in model fuel, and C i is the original amount of DBT in the fuel determined by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

3.1.1 FT-IR spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy is majorly concerned with the vibration of molecules that correspond to specific vibrational energy levels. FT-IR studies were performed to investigate the vibrational band stretching of functional groups present in the prepared rGO and its hybrid materials, Mo–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and In–WO3@rGO in the range between 4,000 and 400/cm, as shown in Figure 1. In rGO, the characteristic peaks were observed: 3,600–3,200/cm (–OH stretching), 3,050/cm (sp2 CH stretching), 2,915/cm (sp3 CH stretching), 1,730/cm (C═O stretching), 1,600–1,500/cm (C═C stretching of aromatic ring), 1,200–1,100/cm (C–O stretching), and 1,030/cm (C–C stretching), all these crests are the clear verification of the formation of rGO material successfully. All the peaks are similar in rGO-supported nanocomposites with just one extra peak owing to the M–O bond peak at 600–500/cm (M = W), which confirms the formation of composites fruitfully.

IR vibrational analysis of (a) rGO, (b) In-WO3@rGO, (c) Mn-WO4@rGO, and (d) Mo-WO3@rGO.

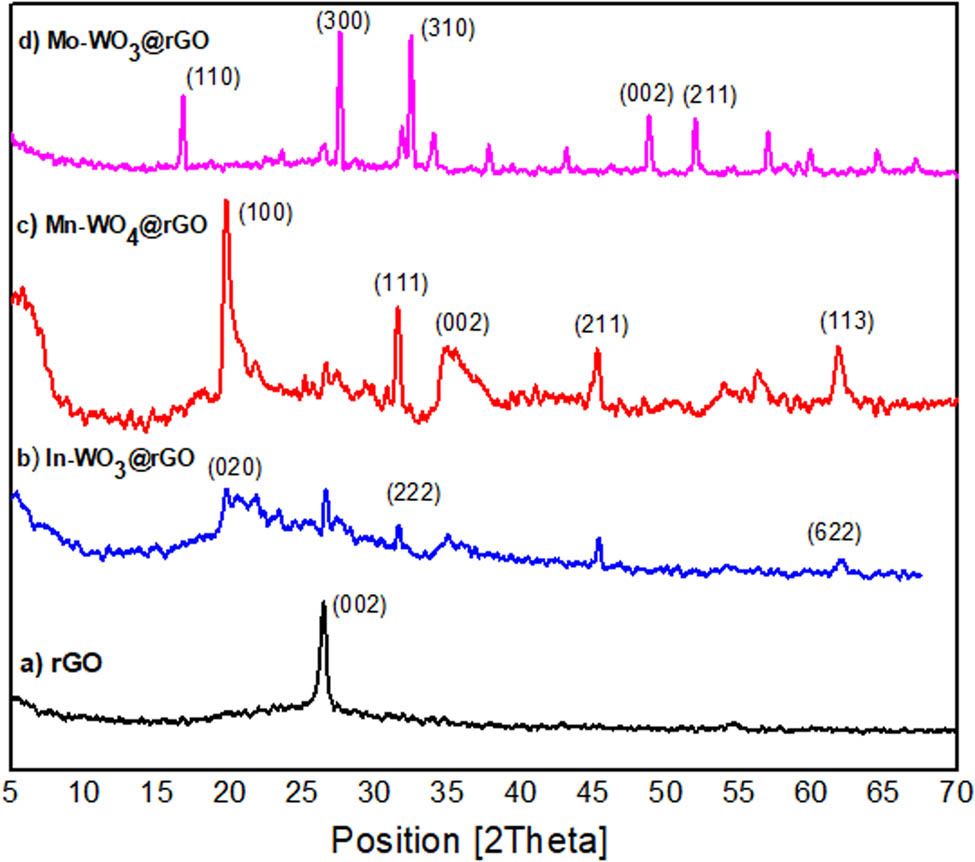

3.1.2 XRD

X-ray diffraction of Cu-kα (0.154 nm) with a span of 2θ = 5°–70° was used to verify the XRD spectrum of rGO and In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO to measure the average crystallite size, basal plane, and crystal system, as shown in Figure 2. There is just a single characteristic peak in the XRD spectra of rGO at 2θ = 26.3° having a basal plane of the (002) plane with a d-space of 0.34 nm, consistent with the JCPDS Card No. 75-2078. The (002) plane, ascribed to the lighter films of rGO due to greater extent of flaking as well as phase of rGO, is quite comparable to g–C3N4. It is confirmed that graphitic coatings may be diminished after loading with nanocomposites of In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO that leads to stacking in an irregular pattern when the intensity of the peak with a basal plane of (002) decreased. Graphene strips are separated into thinner layers with varying latticework, differentiating them from both GO and graphite flakes, as documented in earlier studies. The notable peaks in nanoparticles are as follows: In–WO3@rGO: 2θ = 20.1 (020), 31.5 (222), 63.47 (622); Mn–WO4@rGO: 2θ = 20.23 (100), 32.73 (111), 35.81 (002), 45.21 (211), 62.01 (113); and Mo–WO3@rGO: 2θ = 17.37 (110), 27.81 (300), 34.21 (310), 49.37 (002), 52.32 (211), in which (002), (222), and (020) are correlated with WO3 (JCPDS card no. 72-1465) [25]. As indicated by JCPDS card no. 72-1465, pure WO4 demonstrates the monoclinic crystal structure as outlined in the previous literature, and after successful loading of In and Mo into WO3 makes an orthorhombic geometry. In the XRD pattern of Mn–WO4@rGO, (100), (111), and (113) planes are due to the presence of Mn. Moreover, impurity related peaks have not been found in hybrid materials that depicted the loading of M onto the W latticework rather than the interstitial sites [19]. The average crystallite size was determined through the Debye–Scherrer equation (D = (kλ)/(β cos θ)), where Scherrer constant (k) is equal to 0.9, λ is the wavelength of Cu-kα (0.154 nm), β is the full width at half-maximum, and θ is the Bragg’s angle. The mean crystallite size of rGO, In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO are 18.78, 37.66, 23.41 and 21.26 nm, respectively. Notably, the intensity of the rGO peak is lowered in composites due to doping effect, structural changes, inference, and interaction with other materials in the composites. Composites have diffraction peaks that overlap with rGO peaks, making it hard to distinguish them separately.

XRD pattern of (a) rGO, (b) In-WO3@rGO, (c) Mn-WO4@rGO, and (d) Mo-WO3@rGO.

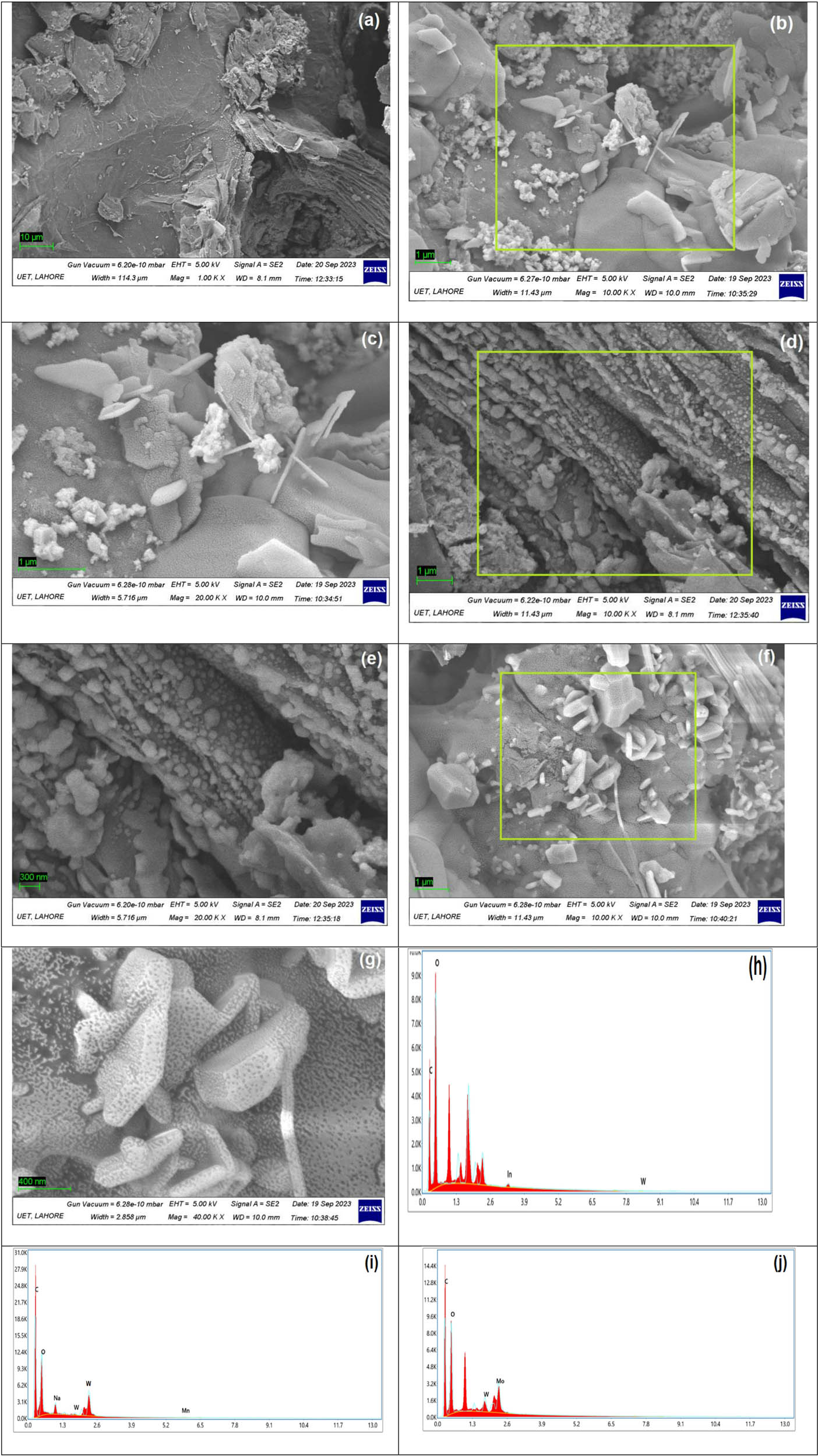

3.1.3 SEM and EDX

SEM uses an intensive beam of energized electrons, instead of light, that investigates the morphology and chemical composition for imaging by scanning and normally for micrometer or nanometer particulates. The micrographs of rGO (Figure 3(a)) and rGO-supported novel nanocomposites of In–WO3@rGO (Figure 3(b) and (c)), Mn–WO4@rGO (Figure 3(d) and (e)), and Mo–WO3@rGO (Figure 3(f) and (g)) were collected using a NOVA NANO SEM. The results revealed that rGO is primarily composed of wrinkled, thin, overlapped sheets, and agglomerated solids were placed willy-nilly with precise and well-defined edges [26]. The indefinite rGO sheets exemplify a clear and apparent manifestation of GO flaking as the length between sheets reduced; however, in composites of rGO, due to doping phenomena, random particles were visible on the exterior of rGO [27]. At elevated magnification, an even dispersion on the exterior of rGO in the case of nanocomposites confirms that rGO granules are not single, but some of them are accumulated between overlapped and agglomerated rGO sheets [28,29]. The particles of In, Mn and Mo are decorated very well on the surface of the rGO sheets and showed interesting morphology, which increased its catalytic activity by increasing the surface area and change in morphology. Furthermore, EDX analysis was used to explore the component pattern in rGO-based materials with X-rays. The occupancy of In, Mn, Mo, and W together with carbon and oxygen atom vertex confirm that In–WO3, Mn–WO4, and Mo–WO3 are successfully doped onto rGO (Figure 3(h), (i) and (j)).

SEM micrographs of rGO (a), In-WO3@rGO (b) and (c), Mn-WO4@rGO (d) and (e), and Mo-WO3@rGO (f) and (g). EDX of In-WO3@rGO (h), Mn-WO4@rGO (i), and Mo-WO3@rGO (j).

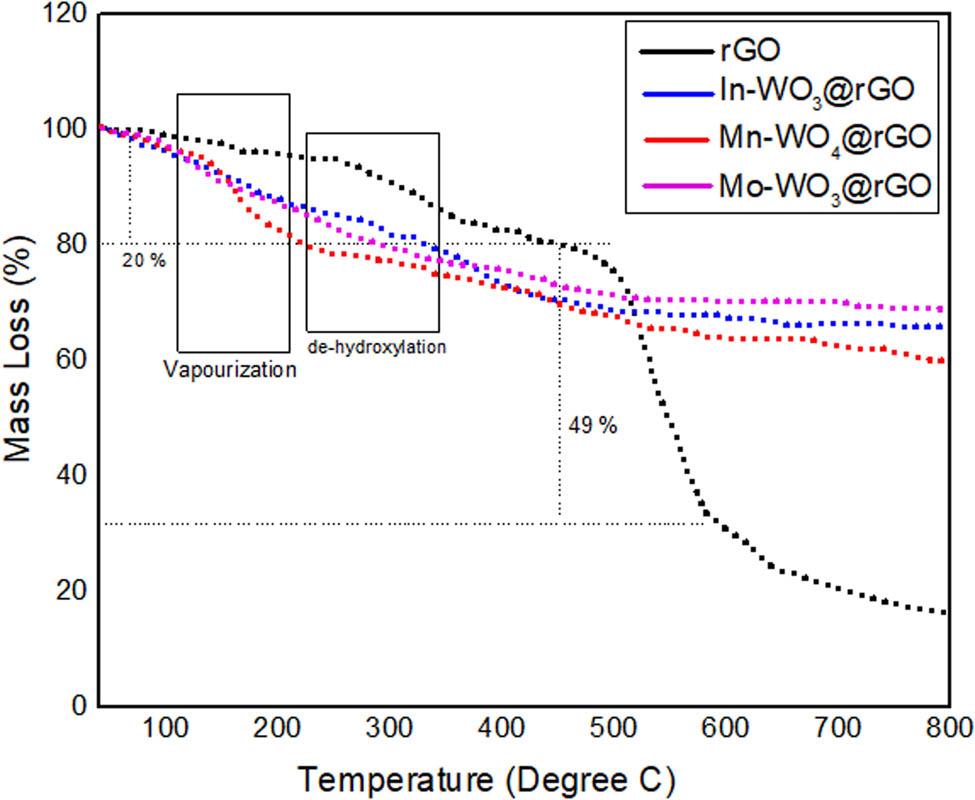

3.1.4 TGA

TGA was performed to observe the heat endurance and disintegration activity of the synthesized materials in the range of 40–800°C, with a scan rate of 5°C/min under inert (He) environments. As shown in Figure 4, at 100–150°C, due to the vaporization of water molecules or other impurities present in rGO, a slight mass loss of 20% was observed [30]. However, for composites (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO), only 9% weight loss was observed up to 200°C, which depicts the loss of remaining oxygen molecules and removal of water molecules that are connected with the surface of rGO. Next, in the range of 300–450°C, 49% mass loss is associated with the removal of carbonaceous material for composites (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO). After 550°C, no significant weight loss was observed for composites and unchangeable mass is reduced to 800°C. Moreover, up to 800°C, almost 80–85% decomposition of rGO took place, which confirmed that temperature had a remarkable effect on the thermal properties of the composites. Pure rGO has a greater weight loss compared to composites in the range of 500–700°C, which proves that nanocomposites are more efficient and reliable for catalytic activity. The hardness, modulus of elasticity, yield strength, and durability of alloy and metal increased as the temperature decreased. In addition, the composites (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) show significant affinity and high thermal stability with rGO.

TGA weight loss curves of rGO, In-WO3@rGO, Mn-WO4@rGO, and Mo-WO3@rGO.

All characterization techniques complement each other by giving in-depth information about the structure of the material, properties, composition, and nature of the composite. IR spectroscopy gives an in-depth understanding of the functional group identification that helps us to correlate the crystallinity determined by XRD. SEM informs about the shape, particle size, and surface topography, while EDX confirms the composition of specific regions identified in SEM images. Overall, all these allow researchers to know about materials’ potential, synthesis, optimization, quality control, and applications.

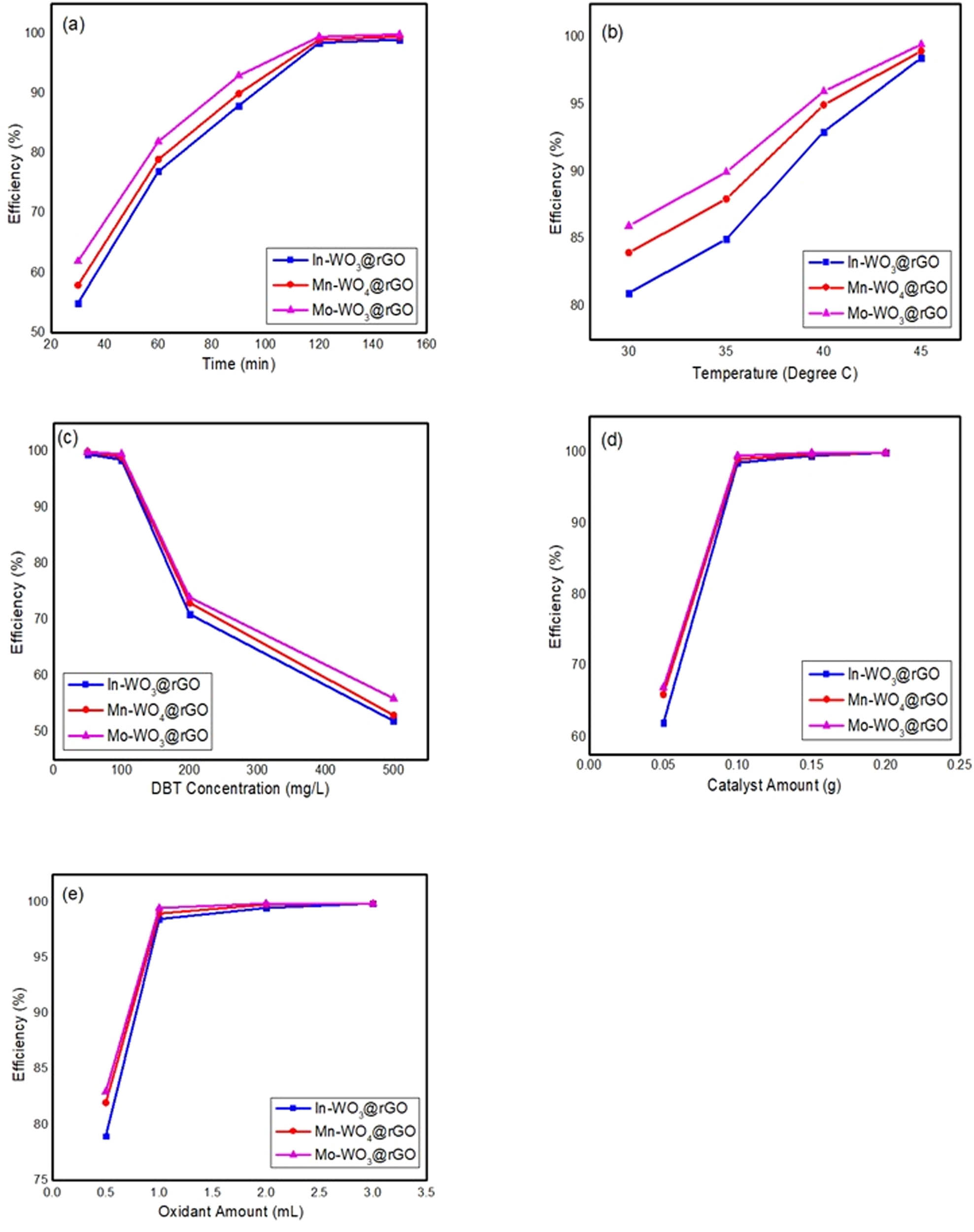

3.2 Optimization

Experiments at different temperatures and times were conducted to determine the effect of temperature (25, 45, 60, and 90°C) and time (30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min), where other parameters were kept constant such as the catalyst, DBT concentration, and amount of H2O2. Illustrating from the graph (temperature versus efficacy), it is unambiguous that temperature had an inverse effect on the activity of the catalyst, which means an increase in temperature decreases the catalytic activity [31]. However, in the case of the time vs efficiency plot, time is directly related to the activity of the stimulant [32]. This is evident that with an increase in temperature, the activity of the catalyst and reaction rate decrease due to the decomposition of the oxidant, as shown in Figure 5(a) and (b). Hence, optimized parameters of time of 2 h and temperature of 45°C were used for subsequent study.

Impact of time (a), temperature (b), DBT dose (c), catalyst amount (d) and oxidant amount (e) on desulfurization of DBT.

Regarding the effect of DBT amount, as shown in Figure 5(c) (50, 100, 200, and 500 mg/L), it is clear that it has an indirect effect with efficiency as a constant catalyst dose is insufficient to provide catalytic sites to oxidize 500 mg/L in 2 h. Hence, a prolonged duration is recommended to oxidize sulfur containing compounds thoroughly at high concentrations. It was investigated that if lower the dose of DBT molecules, the more effective the desulfurization under optimized conditions. As the catalyst amount has foremost effect on catalytic effectiveness, as shown in Figure 5(d), it is clearly investigated that the stimulant dose effects on efficacy (0.05–0.2 g of In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) has positive effect on the catalytic activity while keeping other parameters constant, i.e., the time interval, temperature, DBT extent, and quantity of oxidant. The efficiency of materials (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) enhanced to 99.8% when the catalyst amount increased from 0.05 to 0.2 g. A greater amount of DBT remained unoxidized due to a small dose of catalyst, as there were few catalytic sites available to perform the reaction [33]. Moreover, further increase in the catalyst dosage decreased the catalyst efficiency due to catalyst agglomeration, which blocked the active sites. It is clear from the figure that greater efficiency was achieved by Mo–WO3@rGO compared to the other TMs-WO3 hybrids (Mn–WO4@rGO and In–WO3@rGO), and the highest DBT conversion through Mo–WO3@rGO because of changes in auxiliary/secondary metal performance from regulator to opponent and excellent metal-supported interactions. Moreover, TM molybdenum (Mo)-based hybrid material have low adsorption energy, which results ultimately in lower Ea compared to manganese (Mn) and indium (In). Hydrogen peroxide, which is an oxidant, has a main role in the desulfurization of DBT as it was used as an initiator in reaction media. By maintaining other parameters steady (0.1 g catalyst, 100 mg/L DBT model fuel, 45°C, and time 120 min), the amount of oxidant was changed (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mL) to determine the effect of the oxidant on the efficacy, as depicted in Figure 5(e). Concluding the optimized conditions, a greater quantity of catalyst will lower the DBT content (1 mL of oxidant at approximately 40–45°C), as high concentrations of catalyst may raise the probability of maximum oxidation of sulfur content in the fuel. The study clearly investigated that the H2O2 oxidant has a positive impact on efficiency as it expedites by increasing the amount of initiator/oxidant. Further, no effect was observed when the amount exceeds 2 mL. In this reaction medium, H2O2 acts as an initiator, which confirms its positive behavior by depicting that with the increase in the promoter amount, the efficiency of the catalyst also increases. In the ODS process, hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizing agent has the potential to selectively oxidize sulfur and sulfur-containing compounds (lower oxidation state) under ambient conditions of pressure and temperature and convert them into polar compounds of sulfones and sulfoxides (higher oxidation states).

3.3 Kinetics, thermodynamics, and the ODS mechanism

Kinetic studies provided strong evidence in support of speed and oxidative processes, as they follow the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. From this, the value of the constant is measured, which helps in the estimation of the kinetics of the oxidation reaction [34]. A plot of C F/C I versus time (min) at various temperatures is demonstrated only for Mo–WO3@rGO, as it showed the highest efficiency compared to In–WO3@rGO and Mn–WO4@rGO (Figure S1) and the coherence coefficient (R 2) was ∼1, where C I is the initial concentration and C F is the final concentration of the DBT solution, indicating that the ODS reaction followed pseudo-first-order kinetics at temperatures of 30, 35, 40 and 45°C. Moreover, the optimum energy in the ODS process of DBT can be estimated via the Arrhenius plot by drafting coordinates ln K vs 1/T. The values are calculated using the Arrhenius equation and it was 6.540 kJ/mol for Mo–WO3@rGO. The Arrhenius equation is given as

To understand the effect of temperature on DBT oxidation, a curve was plotted between ln K c and 1/RT to calculate the standard Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy of activation (ΔH°), and entropy of activation (ΔS) via the Eyring equation [35]

In this equation, T denotes absolute temperature, K and K c denotes equilibrium constant where ΔG (the standard Gibbs free energy) can be evaluated using [36,37]

From the plot ln K c vs 1/RT, the given outcomes show positive values of ΔS and ΔH depicting an endothermic process and haphazardness in the reaction medium, respectively, as listed in Table 1. However, negative values of the standard Gibbs free energy indicate that DBT removal via In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO is a stable and thermodynamically useful ODS process.

Thermodynamic factors affecting the removal of sulfur content (DBT) through oxidative desulfurization

| Novel catalyst | ΔG (kJ/mol) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (kJ/mol K) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298.5 K | 303.5 K | 308.5 K | 313.5 K | |||

| Mo–WO3@rGO | −0.506 | −2.551 | −5.193 | −14.016 | 260.27 | 0.854 |

3.4 ODS of real fuel oils

Catalytic testing of synthesized nano-composites (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO) was carried out for fuel samples available in the market using 0.2 g catalyst, 3 mL of H2O2, 50 mL of fuel sample, and time span of 180 min at 45°C. To determine the sulfur content, pre- and post-ODS processes were completed via PETRA XRF. Moreover, other fuel properties such as distillation (ASTM D-86), moisture content (ASTM D-4006), and relative gravity (ASTM D-1298) were also investigated before and after ODS and provided in Table 2. A slight difference was noted before and after ODS in fuel properties, which is a clear confirmation that the catalytic system does not impact the characteristics of oil except specific elimination of sulfur species [38,39]. From the ODS of oil (In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and Mo–WO3@rGO), results declared that Mo–WO3@rGO is slightly more efficient than In–WO3@rGO and Mn–WO4@rGO for both real and model fuel. Besides this, all nanocomposites proved optimistic and robust for the effective removal of DBT.

ODS of real oil via In–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO and Mo–WO3@rGO

| Specific gravity (g/mL at 15.6°C) | Total sulfur by petra X-ray (ppm) | Water content (vol%) | Distillation (°C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel and catalysts | 50% | 90% | |||||

| Kerosene | Before ODS | 0.831 | 1,525 | Nil | 241 | 304 | |

| After ODS | In–WO3@rGO | 0.830 | 135 | Nil | 236 | 302 | |

| Mn–WO4@rGO | 0.828 | 144 | Nil | 238 | 299 | ||

| Mo–WO3@rGO | 0.827 | 152 | Nil | 238 | 298 | ||

| Diesel | Before ODS | 0.885 | 4,596 | Nil | 286 | 345 | |

| After ODS | In–WO3@rGO | 0.882 | 425 | Nil | 279 | 337 | |

| Mn–WO4@rGO | 0.879 | 433 | Nil | 279 | 342 | ||

| Mo–WO3@rGO | 0.877 | 449 | Nil | 280 | 338 | ||

3.5 Reusability of catalyst

Catalysts speed up the reaction mechanism, depriving of a structural or compositional modification, i.e., help to cause a reaction at a faster rate by reducing the activation energy of the chemical reaction. The reusability of the catalyst plays an important role due to its practical uses as it assesses the financial viability of the newly created catalyst scheme. To test restoration and recovery of catalysts (Mo–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and In–WO3@rGO) via simple filtration technique, first, it is detached from the reaction medium, rinsed with n-hexane/dichloromethane (any non-polar solvents), dried, and reused. After the evaluation test of reusability was performed, results indicated no significant alteration in the efficacy of the catalyst for the conversion rate of DBT even after five times. A slight loss in efficiency was noted after five cycles, and this occurred due to a decrease in catalytic sites and mass damage of the catalyst during the purification process. The catalysts (Mo–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and In–WO3@rGO) showed excellent stability and maintained its potency up to five catalytic rounds. Previously reported studies for ODS using rGO-based catalysts are provided in Table 3. The reported literature confirmed that there is no report on rGO as supported TMs (Mo, Mn, and In) doped tungstate. This study consisting of newly synthesized hybrids of Mo–WO3@rGO, Mn–WO4@rGO, and In–WO3@rGO have been certified for the first time for the oxidative process for the extraction of DBT. Moreover, there are sufficient reported data on rGO-assisted transition metal-based catalysts.

Comparison with other reported studies

| Material | Oxidant | Sulfur specie | DBT concentration (ppm) | Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi2WO6@rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 100 | 97 | [16] |

| CuWO4@rGO | DBT | 100 | 99 | ||

| NiWO3@g–C3N4 | H2O2 | DBT | 100 | 97 | [2] |

| Kerosene | 1,635 | 91.5 | |||

| Diesel | 4,630 | 89.5 | |||

| WO3/g–C3N4 | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | 91.2 | [40] |

| NiW/rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | >90 | [19] |

| CoW/rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | ∼100 | |

| CoMo/rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | 99 | [41] |

| g–C3N4 | TBHP | DBT | 500 | >10 | [42] |

| MoO2/g–C3N4 | TBHP | DBT | 500 | ∼100 | |

| Mo–WO3@rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | 99.8 | Current study |

| Mn–WO4@rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | 99.5 | Current study |

| In–WO3@rGO | H2O2 | DBT | 500 | 99 | Current study |

4 Conclusion

The fruitful hydrothermal treatment of rGO-supported nanohybrids was carried out for the first time for ODS of real as well as model fuel. Out of these three hybrids, remarkable desulfurization efficiency of model fuel was accompanied by Mo–WO3@rGO 98.5% using H2O2 as an oxidant. XRD results revealed an average crystallite size of less than 40 nm, and morphology observed through SEM indicated that hybrids are well embellished on the exterior of rGO. The activity for real fuel oil was scrutinized by using these three catalyst and removal efficiencies were 90.23 and 90.03% for diesel and kerosene oil for In–WO3@rGO; for Mo–WO3@rGO, 90.7 and 91.15%; for Mn–WO4@rGO, 90.57 and 90.55%, respectively, under optimum conditions. Multiple parameters such as time, catalyst amount, oxidant amount, and concentration were determined and found that all had a direct relationship with efficiency, except the DBT concentration that followed a pseudo-first order with a negative value of ΔG, depicting thermodynamic stability at 298.5, 303.5, 308.5, and 313.5 K. In addition, five times reusability of the catalyst confirmed its stability, with little reduction in effectiveness for the ODS process. Therefore, complete novel innovation depicts the eminence of the synthesized nanomaterials for the green generation of sulfur-free fluid.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University of the Punjab for assistance.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Jabar G, Saeed M, Khoso S, Zafar A, Saggu JI, Waseem A. Development of graphitic carbon nitride supported novel nanocomposites for green and efficient oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil. Nanomater Nanotechnol. 2022;12:1–13.10.1177/18479804221106321Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Saeed M, Munir M, Intisar A, Waseem A. Facile synthesis of a Novel Ni-WO3@g-C3N4 nanocomposite for efficient oxidative desulfurization of both model and real fuel. ACS Omega. 2022;7:15809–20.10.1021/acsomega.2c00886Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Ahsan H, Anayyat U, Saeed M, Anwar A, Haider S, Intisar A, et al. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of rGO supported novel hybrid materials for green fuel production. J Indian Chem Soc. 2024;101:101141.10.1016/j.jics.2024.101141Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Lu L, Cheng S, Gao J, Gao G, He MY. Deep oxidative desulfurization of fuels catalyzed by ionic liquid in the presence of H2O2. Energy Fuels. 2007;21:383–4.10.1021/ef060345oSuche in Google Scholar

[5] Rivoira LP, Valles VA, Martínez ML, Sa-ngasaeng Y, Jongpatiwut S, Beltramone AR. Catalytic oxidation of sulfur compounds over Ce-SBA-15 and Ce-Zr-SBA-15. Catal Today. 2021;360:116–28.10.1016/j.cattod.2019.08.005Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Saeed M, Riaz A, Intisar A, Iqbal Zafar M, Fatima H, Howari H, et al. Synthesis, characterization and application of organoclays for adsorptive desulfurization of fuel oil. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7362.10.1038/s41598-022-11054-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Rezvani MA, Ardeshiri HH, Aghasadeghi Z. Extractive-oxidative desulfurization of real and model gasoline using (gly)3H[SiW12O40] ⊂ CoFe2O4 as a recoverable and efficient nanocatalyst. Energy Fuels. 2023;37:2245–54.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c03265Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Saeed M, Waseem A, Intisar A. Catalytic activity of MnWO4@g-C3N4 and CuWO4@g-C3N4 nano-composites for green fuel production. Catal Surv Asia. 2024. 10.1007/s10563-024-09437-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Haruna A, Merican ZMA, Musa SG. Recent advances in catalytic oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil – A review. J Ind Eng Chem. 2022;112:20–36.10.1016/j.jiec.2022.05.023Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Hossain MN, Park HC, Choi HS. A comprehensive review on catalytic oxidative desulfurization of liquid fuel oil. Catalysts. 2019;9:229.10.3390/catal9030229Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Jiang W, Zhu W, Chang Y, Chao Y, Yin S, Liu H, et al. Ionic liquid extraction and catalytic oxidative desulfurization of fuels using dialkylpiperidinium tetrachloroferrates catalysts. Chem Eng J. 2014;250:48–54.10.1016/j.cej.2014.03.074Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Chen L, Ren JT, Wang HY, Sun ML, Yuan ZY. Engineering a local hydrophilic environment in fuel oil for efficient oxidative desulfurization with minimum H2O2 oxidant. ACS Catal. 2023;131:2125–33.10.1021/acscatal.3c02509Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Rezvani MA, Shaterian M, Akbarzadeh F, Khandan S. Deep oxidative desulfurization of gasoline induced by PMoCu@MgCu2O4-PVA composite as a high-performance heterogeneous nanocatalyst. Chem Eng J. 2018;333:537–44.10.1016/j.cej.2017.09.184Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Lorençon E, Alves DCB, Krambrock K, Ávila ES, Resende RR, Ferlauto AS, et al. Oxidative desulfurization of dibenzothiophene over titanate nanotubes. Fuel. 2014;132:53–61.10.1016/j.fuel.2014.04.020Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Rezvani MA, Aghbolagh ZS, Monfared HH. Green and efficient organic–inorganic hybrid nanocatalyst for oxidative desulfurization of gasoline. Appl Organomet Chem. 2018;32:e4592.10.1002/aoc.4592Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Riaz A, Saeed M, Munir M, Intisar A, Haider S, Tariq S, et al. Development of reduced graphene oxide-supported novel hybrid nanomaterials (Bi2WO6@rGO and Cu-WO4@rGO) for green and efficient oxidative desulfurization of model fuel oil for environmental depollution. Environ Res. 2022;212:113160.10.1016/j.envres.2022.113160Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Rezvani MA, Khandan S, Rahim M. Synthesis of (Gly)3PMo12O40@MnFe2O4 organic/inorganic hybrid nanocomposite as an efficient and magnetically recoverable catalyst for oxidative desulfurization of liquid fuels. Int J Energy Res. 2022;46:2617–32.10.1002/er.7332Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Bhadra BN, Jhung SH. Oxidative desulfurization and denitrogenation of fuels using metal-organic framework-based/-derived catalysts. Appl Catal, B. 2019;259:118021.10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118021Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Hasannia S, Kazemeini M, Seif A, Rashidi A. Oxidative desulfurization of a model liquid fuel over an rGO-supported transition metal modified WO3 catalyst: Experimental and theoretical studies. Sep, Purif Technol. 2021;269:118729.10.1016/j.seppur.2021.118729Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Rashid T, Raza A, Saleh HAM, Khan S, Rahaman S, Pandey K, et al. Green synthesis of Ni/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites for desulfurization of fuel. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2023;6:18905–17.10.1021/acsanm.3c03270Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Rezvani MA, Khandan S. Synthesis and characterization of a new nanocomposite (FeW11V@CTAB-MMT) as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for oxidative desulfurization of gasoline. Appl Organomet Chem. 2018;32:e4524.10.1002/aoc.4524Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Ahmadian M, Anbia M. Oxidative desulfurization of liquid fuels using polyoxometalate-based catalysts: A review. Energy Fuels. 2021;35:10347–73.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00862Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Rezvani MA, Imani A. Ultra-deep oxidative desulfurization of real fuels by sandwich-type polyoxometalate immobilized on copper ferrite nanoparticles, Fe6W18O70 ⊂ CuFe2O4, as an efficient heterogeneous nanocatalyst. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9:105009.10.1016/j.jece.2020.105009Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Salmanzadeh Otaghsaraei S, Kazemeini M, Hasannia S, Ekramipooya A. Deep oxidative desulfurization via rGO-immobilized tin oxide nanocatalyst: Experimental and theoretical perspectives. Adv Powder Technol. 2022;33:103499.10.1016/j.apt.2022.103499Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Zhai C, Zhu M, Jiang L, Yang T, Zhao Q, Luo Y, et al. Fast triethylamine gas sensing response properties of nanosheets assembled WO3 hollow microspheres. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;463:1078–84.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.09.049Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Zuo P, Liu Y, Jiao J, Ren J, Wang R, Jiao W. Ultrafine W2c well-dispersed on N-doped graphene: extraordinary catalyst for ultrafast oxidative desulfurization of high sulfur liquid fuels. SSRN Electron J. 2022;643:118791.10.1016/j.apcata.2022.118791Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Munir M, Saeed M, Ahmad M, Waseem A, Alsaady M, Asif S, et al. Cleaner production of biodiesel from novel non-edible seed oil (Carthamus lanatus L.) via highly reactive and recyclable green nano CoWO3@rGO composite in context of green energy adaptation. Fuel. 2023;332:126265.10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126265Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Alam SN, Sharma N, Kumar L. Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO) by modified hummers method and its thermal reduction to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene. 2017;6:1–18.10.4236/graphene.2017.61001Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Guex LG, Sacchi B, Peuvot KF, Andersson RL, Pourrahimi AM, Ström V, et al. Experimental review: Chemical reduction of graphene oxide (GO) to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) by aqueous chemistry. Nanoscale. 2017;9:9562–71.10.1039/C7NR02943HSuche in Google Scholar

[30] Li Y, Xiao X, Ye Z. Fabrication of BiVO4/RGO/Ag3PO4 ternary composite photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;467–468:902–11.10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.10.226Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang W, Li G, Wang W, Qin Y, An T, Xiao X, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic mechanism of Ag3PO4 nano-sheets using MS2 (M = Mo, W)/rGO hybrids as co-catalysts for 4-nitrophenol degradation in water. Appl Catal, B. 2018;232:11–8.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Sharma V, Jain Y, Kumari M, Gupta R, Sharma SK, Sachdev K. Synthesis and characterization of graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) for gas sensing application. Macromol Symp. 2017;376:1700006.10.1002/masy.201700006Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Rezvani MA, Maleki Z. Facile synthesis of inorganic–organic Fe2W18Fe4@NiO@CTS hybrid nanocatalyst induced efficient performance in oxidative desulfurization of real fuel. Appl Organomet Chem. 2019;33:e4895.10.1002/aoc.4895Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Kayedi N, Samimi A, Asgari Bajgirani M, Bozorgian A. Enhanced oxidative desulfurization of model fuel: A comprehensive experimental study. S Afr J Chem Eng. 2021;35:153–8.10.1016/j.sajce.2020.09.001Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Rezvani MA, Khandan S. Synthesis and characterization of new sandwich-type polyoxometalate/nanoceramic nanocomposite, Fe2W18Fe4@FeTiO3, as a highly efficient heterogeneous nanocatalyst for desulfurization of fuel. Solid State Sci. 2019;98:106036.10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.106036Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Saeed M, Munir M, Nafees M, Shah SSA, Ullah H, Waseem A. Synthesis, characterization and applications of silylation based grafted bentonites for the removal of Sudan dyes: Isothermal, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;291:109697.10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.109697Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Tariq S, Saeed M, Zahid U, Munir M, Intisar A, Asad Riaz M, et al. Green and eco-friendly adsorption of dyes with organoclay: isothermal, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Toxin Rev. 2022;41:1105–14.10.1080/15569543.2021.1975751Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Rezvani MA, Hadi M, Mirsadri SA. Synthesis of new nanocomposite based on nanoceramic and mono substituted polyoxometalate, PMo11Cd@MnFe2O4, with superior catalytic activity for oxidative desulfurization of real fuel. Appl Organomet Chem. 2020;34:e5882.10.1002/aoc.5882Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zhang H, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Pei T, Dong L, Zhou P, et al. Acidic polymeric ionic liquids based reduced graphene oxide: An efficient and rewriteable catalyst for oxidative desulfurization. Chem Eng J. 2018;334:285–95.10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.042Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Zhao R, Li X, Su J, Gao X. Preparation of WO3/g-C3N4 composites and their application in oxidative desulfurization. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;392:810–6.10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.08.120Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Hasannia S, Kazemeini M, Rashidi A, Seif A. The oxidative desulfurization process performed upon a model fuel utilizing modified molybdenum based nanocatalysts: Experimental and density functional theory investigations under optimally prepared and operated conditions. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;527:146798.10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146798Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Chen K, Zhang XM, Yang XF, Jiao MG, Zhou Z, Zhang MH, et al. Electronic structure of heterojunction MoO2/g-C3N4 catalyst for oxidative desulfurization. Appl Catal, B. 2018;238:263–73.10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.07.037Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory

- One-pot fabrication of open-spherical shapes based on the decoration of copper sulfide/poly-O-amino benzenethiol on copper oxide as a promising photocathode for hydrogen generation from the natural source of Red Sea water

- A penta-hybrid approach for modeling the nanofluid flow in a spatially dependent magnetic field

- Advancing sustainable agriculture: Metal-doped urea–hydroxyapatite hybrid nanofertilizer for agro-industry

- Utilizing Ziziphus spina-christi for eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Antimicrobial activity and promising application in wound healing

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a copper oxide/silicon dioxide nanocomposite by an antimicrobial study

- Effects of PVA fibers and nano-SiO2 on rheological properties of geopolymer mortar

- Investigating silver and alumina nanoparticles’ impact on fluid behavior over porous stretching surface

- Potential pharmaceutical applications and molecular docking study for green fabricated ZnO nanoparticles mediated Raphanus sativus: In vitro and in vivo study

- Effect of temperature and nanoparticle size on the interfacial layer thickness of TiO2–water nanofluids using molecular dynamics

- Characteristics of induced magnetic field on the time-dependent MHD nanofluid flow through parallel plates

- Flexural and vibration behaviours of novel covered CFRP composite joints with an MWCNT-modified adhesive

- Experimental research on mechanically and thermally activation of nano-kaolin to improve the properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Analysis of variable fluid properties for three-dimensional flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid on a stretching sheet with MHD effects

- Biodegradability of corn starch films containing nanocellulose fiber and thymol

- Toxicity assessment of copper oxide nanoparticles: In vivo study

- Some measures to enhance the energy output performances of triboelectric nanogenerators

- Reinforcement of graphene nanoplatelets on water uptake and thermomechanical behaviour of epoxy adhesive subjected to water ageing conditions

- Optimization of preparation parameters and testing verification of carbon nanotube suspensions used in concrete

- Max-phase Ti3SiC2 and diverse nanoparticle reinforcements for enhancement of the mechanical, dynamic, and microstructural properties of AA5083 aluminum alloy via FSP

- Advancing drug delivery: Neural network perspectives on nanoparticle-mediated treatments for cancerous tissues

- PEG-PLGA core–shell nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of picoplatin–hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in triple-negative breast cancer: In vitro and in vivo study

- Conduction transportation from graphene to an insulative polymer medium: A novel approach for the conductivity of nanocomposites

- Review Articles

- Developments of terahertz metasurface biosensors: A literature review

- Overview of amorphous carbon memristor device, modeling, and applications for neuromorphic computing

- Advances in the synthesis of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) of proteins extracted from nature

- A review of ternary polymer nanocomposites containing clay and calcium carbonate and their biomedical applications

- Recent advancements in polyoxometalate-functionalized fiber materials: A review

- Special contribution of atomic force microscopy in cell death research

- A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery

- Cellular senescence and nanoparticle-based therapies: Current developments and perspectives

- Cyclodextrins-block copolymer drug delivery systems: From design and development to preclinical studies

- Micelle-based nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive properties for drug delivery

- Critical assessment of the thermal stability and degradation of chemically functionalized nanocellulose-based polymer nanocomposites

- Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder

- Nanoformulations for lysozyme-based additives in animal feed: An alternative to fight antibiotic resistance spread

- Incorporation of organic photochromic molecules in mesoporous silica materials: Synthesis and applications

- A review on modeling of graphene and associated nanostructures reinforced concrete

- A review on strengthening mechanisms of carbon quantum dots-reinforced Cu-matrix nanocomposites

- Review on nanocellulose composites and CNFs assembled microfiber toward automotive applications

- Nanomaterial coating for layered lithium rich transition metal oxide cathode for lithium-ion battery

- Application of AgNPs in biomedicine: An overview and current trends

- Nanobiotechnology and microbial influence on cold adaptation in plants

- Hepatotoxicity of nanomaterials: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy

- Applications of micro-nanobubble and its influence on concrete properties: An in-depth review

- A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

- Exploiting the nanotechnological approaches for traditional Chinese medicine in childhood rhinitis: A review of future perspectives

- Twisto-photonics in two-dimensional materials: A comprehensive review

- Current advances of anticancer drugs based on solubilization technology

- Recent process of using nanoparticles in the T cell-based immunometabolic therapy

- Future prospects of gold nanoclusters in hydrogen storage systems and sustainable environmental treatment applications

- Preparation, types, and applications of one- and two-dimensional nanochannels and their transport properties for water and ions

- Microstructural, mechanical, and corrosion characteristics of Mg–Gd–x systems: A review of recent advancements

- Functionalized nanostructures and targeted delivery systems with a focus on plant-derived natural agents for COVID-19 therapy: A review and outlook

- Mapping evolution and trends of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles: A bibliometric analysis and scoping review

- Nanoparticles and their application in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- In situ growth of carbon nanotubes on fly ash substrates

- Structural performance of boards through nanoparticle reinforcement: An advance review

- Reinforcing mechanisms review of the graphene oxide on cement composites

- Seed regeneration aided by nanomaterials in a climate change scenario: A comprehensive review

- Surface-engineered quantum dot nanocomposites for neurodegenerative disorder remediation and avenue for neuroimaging

- Graphitic carbon nitride hybrid thin films for energy conversion: A mini-review on defect activation with different materials

- Nanoparticles and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials and Composites for Energy Conversion and Storage - Part II

- Highly safe lithium vanadium oxide anode for fast-charging dendrite-free lithium-ion batteries

- Recent progress in nanomaterials of battery energy storage: A patent landscape analysis, technology updates, and future prospects

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part II

- Calcium-, magnesium-, and yttrium-doped lithium nickel phosphate nanomaterials as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water oxidation reaction

- Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology

- Mesoporous silica-grafted deep eutectic solvent-based mixed matrix membranes for wastewater treatment: Synthesis and emerging pollutant removal performance

- Electrochemically prepared ultrathin two-dimensional graphitic nanosheets as cathodes for advanced Zn-based energy storage devices

- Enhanced catalytic degradation of amoxicillin by phyto-mediated synthesised ZnO NPs and ZnO-rGO hybrid nanocomposite: Assessment of antioxidant activity, adsorption, and thermodynamic analysis

- Incorporating GO in PI matrix to advance nanocomposite coating: An enhancing strategy to prevent corrosion

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal stability, and application of microporous hyper cross-linked polyphosphazenes with naphthylamine group for CO2 uptake

- Engineering in ceramic albite morphology by the addition of additives: Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide for energy applications

- Nanoscale synergy: Optimizing energy storage with SnO2 quantum dots on ZnO hexagonal prisms for advanced supercapacitors

- Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation

- Tuning structural and electrical properties of Co-precipitated and Cu-incorporated nickel ferrite for energy applications

- Sodium alginate-supported AgSr nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of malachite green and methyl orange in aqueous medium

- An environmentally greener and reusability approach for bioenergy production using Mallotus philippensis (Kamala) seed oil feedstock via phytonanotechnology

- Micro-/nano-alumina trihydrate and -magnesium hydroxide fillers in RTV-SR composites under electrical and environmental stresses

- Mechanism exploration of ion-implanted epoxy on surface trap distribution: An approach to augment the vacuum flashover voltages

- Nanoscale engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts boosting charge separation for solar-driven H2 production: Recent advances and future perspective

- Excellent catalytic performance over reduced graphene-boosted novel nanoparticles for oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil

- Special Issue on Advances in Nanotechnology for Agriculture

- Deciphering the synergistic potential of mycogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles and bio-slurry formulation on phenology and physiology of Vigna radiata

- Nanomaterials: Cross-disciplinary applications in ornamental plants

- Special Issue on Catechol Based Nano and Microstructures

- Polydopamine films: Versatile but interface-dependent coatings

- In vitro anticancer activity of melanin-like nanoparticles for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma

- Poly-3,4-dihydroxybenzylidenhydrazine, a different analogue of polydopamine

- Chirality and self-assembly of structures derived from optically active 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and catecholamines

- Advancing resource sustainability with green photothermal materials: Insights from organic waste-derived and bioderived sources

- Bioinspired neuromelanin-like Pt(iv) polymeric nanoparticles for cancer treatment

- Special Issue on Implementing Nanotechnology for Smart Healthcare System

- Intelligent explainable optical sensing on Internet of nanorobots for disease detection

- Special Issue on Green Mono, Bi and Tri Metallic Nanoparticles for Biological and Environmental Applications

- Tracking success of interaction of green-synthesized Carbopol nanoemulgel (neomycin-decorated Ag/ZnO nanocomposite) with wound-based MDR bacteria

- Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using genus Inula and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications

- Biogenic fabrication and multifunctional therapeutic applications of silver nanoparticles synthesized from rose petal extract

- Metal oxides on the frontlines: Antimicrobial activity in plant-derived biometallic nanoparticles

- Controlling pore size during the synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using CTAB by the sol–gel hydrothermal method and their biological activities

- Special Issue on State-of-Art Advanced Nanotechnology for Healthcare

- Applications of nanomedicine-integrated phototherapeutic agents in cancer theranostics: A comprehensive review of the current state of research

- Smart bionanomaterials for treatment and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease

- Beyond conventional therapy: Synthesis of multifunctional nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis therapy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Tension buckling and postbuckling of nanocomposite laminated plates with in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised gold nanoparticle coatings inhibit blood protein adsorption

- Energy and mass transmission through hybrid nanofluid flow passing over a spinning sphere with magnetic effect and heat source/sink

- Surface treatment with nano-silica and magnesium potassium phosphate cement co-action for enhancing recycled aggregate concrete

- Numerical investigation of thermal radiation with entropy generation effects in hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet

- Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials

- Using nano-CaCO3 and ceramic tile waste to design low-carbon ultra high performance concrete

- Numerical analysis of thermophoretic particle deposition in a magneto-Marangoni convective dusty tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow – Thermal and magnetic features

- Dual numerical solutions of Casson SA–hybrid nanofluid toward a stagnation point flow over stretching/shrinking cylinder

- Single flake homo p–n diode of MoTe2 enabled by oxygen plasma doping

- Electrostatic self-assembly effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on performance of carbon nanotubes in cement-based materials

- Multi-scale alignment to buried atom-scale devices using Kelvin probe force microscopy

- Antibacterial, mechanical, and dielectric properties of hydroxyapatite cordierite/zirconia porous nanocomposites for use in bone tissue engineering applications

- Time-dependent Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid comprising the CNTs through a Riga plate with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation

- Durability prediction of geopolymer mortar reinforced with nanoparticles and PVA fiber using particle swarm optimized BP neural network

- Utilization of zein nano-based system for promoting antibiofilm and anti-virulence activities of curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Antibacterial effect of novel dental resin composites containing rod-like zinc oxide

- An extended model to assess Jeffery–Hamel blood flow through arteries with iron-oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles and melting effects: Entropy optimization analysis

- Comparative study of copper nanoparticles over radially stretching sheet with water and silicone oil

- Cementitious composites modified by nanocarbon fillers with cooperation effect possessing excellent self-sensing properties

- Confinement size effect on dielectric properties, antimicrobial activity, and recycling of TiO2 quantum dots via photodegradation processes of Congo red dye and real industrial textile wastewater

- Biogenic silver nanoparticles of Moringa oleifera leaf extract: Characterization and photocatalytic application

- Novel integrated structure and function of Mg–Gd neutron shielding materials

- Impact of multiple slips on thermally radiative peristaltic transport of Sisko nanofluid with double diffusion convection, viscous dissipation, and induced magnetic field

- Magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially stretching sheet with thermal convective and mass flux conditions: HAM solution

- A numerical investigation of the two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic water-based hybrid nanofluid flow composed of Fe3O4 and Au nanoparticles over a heated surface

- Development and modeling of an ultra-robust TPU-MWCNT foam with high flexibility and compressibility

- Effects of nanofillers on the physical, mechanical, and tribological behavior of carbon/kenaf fiber–reinforced phenolic composites

- Polymer nanocomposite for protecting photovoltaic cells from solar ultraviolet in space

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and nano-silica in early low-temperature environments

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar

- CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co–Au) and trihybrid (Co–Au–ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium

- Forced convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow subject to heat source/sink and Lorentz force over a permeable wedge: Numerical exploration

- Physiochemical and electrical activities of nano copper oxides synthesised via hydrothermal method utilising natural reduction agents for solar cell application

- A homotopic analysis of the blood-based bioconvection Carreau–Yasuda hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective conditions

- In situ synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnIn4S8 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic performance for pollutant degradation

- A coarse-grained Poisson–Nernst–Planck model for polyelectrolyte-modified nanofluidic diodes

- A numerical investigation of the magnetized water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over an extending sheet with a convective condition: Active and passive controls of nanoparticles

- The LyP-1 cyclic peptide modified mesoporous polydopamine nanospheres for targeted delivery of triptolide regulate the macrophage repolarization in atherosclerosis

- Synergistic effect of hydroxyapatite-magnetite nanocomposites in magnetic hyperthermia for bone cancer treatment

- The significance of quadratic thermal radiative scrutinization of a nanofluid flow across a microchannel with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- Ferromagnetic effect on Casson nanofluid flow and transport phenomena across a bi-directional Riga sensor device: Darcy–Forchheimer model

- Performance of carbon nanomaterials incorporated with concrete exposed to high temperature

- Multicriteria-based optimization of roller compacted concrete pavement containing crumb rubber and nano-silica

- Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts

- Exploration of irreversibility process and thermal energy of a tetra hybrid radiative binary nanofluid focusing on solar implementations

- Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of ternary limestone clay cement paste

- Improved mechanical properties of graphene-modified basalt fibre–epoxy composites

- Sodium titanate nanostructured modified by green synthesis of iron oxide for highly efficient photodegradation of dye contaminants

- Green synthesis of Vitis vinifera extract-appended magnesium oxide NPs for biomedical applications

- Differential study on the thermal–physical properties of metal and its oxide nanoparticle-formed nanofluids: Molecular dynamics simulation investigation of argon-based nanofluids

- Heat convection and irreversibility of magneto-micropolar hybrid nanofluids within a porous hexagonal-shaped enclosure having heated obstacle

- Numerical simulation and optimization of biological nanocomposite system for enhanced oil recovery

- Laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition to prepare a nanostructured PPy layer on the Ti surface

- Cilostazol niosomes-loaded transdermal gels: An in vitro and in vivo anti-aggregant and skin permeation activity investigations towards preparing an efficient nanoscale formulation

- Linear and nonlinear optical studies on successfully mixed vanadium oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique

- Analytical investigation of convective phenomena with nonlinearity characteristics in nanostratified liquid film above an inclined extended sheet

- Optimization method for low-velocity impact identification in nanocomposite using genetic algorithm

- Analyzing the 3D-MHD flow of a sodium alginate-based nanofluid flow containing alumina nanoparticles over a bi-directional extending sheet using variable porous medium and slip conditions

- A comprehensive study of laser irradiated hydrothermally synthesized 2D layered heterostructure V2O5(1−x)MoS2(x) (X = 1–5%) nanocomposites for photocatalytic application

- Computational analysis of water-based silver, copper, and alumina hybrid nanoparticles over a stretchable sheet embedded in a porous medium with thermophoretic particle deposition effects

- A deep dive into AI integration and advanced nanobiosensor technologies for enhanced bacterial infection monitoring

- Effects of normal strain on pyramidal I and II 〈c + a〉 screw dislocation mobility and structure in single-crystal magnesium

- Computational study of cross-flow in entropy-optimized nanofluids

- Significance of nanoparticle aggregation for thermal transport over magnetized sensor surface

- A green and facile synthesis route of nanosize cupric oxide at room temperature

- Effect of annealing time on bending performance and microstructure of C19400 alloy strip

- Chitosan-based Mupirocin and Alkanna tinctoria extract nanoparticles for the management of burn wound: In vitro and in vivo characterization

- Electrospinning of MNZ/PLGA/SF nanofibers for periodontitis

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by Nd-doped titanium dioxide thin films

- Shell-core-structured electrospinning film with sequential anti-inflammatory and pro-neurogenic effects for peripheral nerve repairment

- Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory