A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development

-

Inam Ur Rehman

, Jakyoung Min

Abstract

The rapid expansion of nanotechnology has transformed numerous sectors, with nanoproducts now ubiquitous in everyday life, electronics, healthcare, and pharmaceuticals. Despite their widespread adoption, concerns persist regarding potential adverse effects, necessitating vigilant risk management. This systematic literature review advocates for leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) methodologies to enhance simulations and refine safety assessments for nanomaterials (NMs). Through a comprehensive examination of the existing literature, this study seeks to explain the pivotal role of AI in boosting NMs sustainability efforts across six key research themes. It explores their significance in advancing sustainability, hazard identification, and their diverse applications in this field. In addition, it evaluates the past sustainability strategies for NMs while proposing innovative avenues for future exploration. By conducting this comprehensive analysis, the research aims to illuminate the current landscape, identify challenges, and outline potential pathways for integrating AI and ML to promote sustainable practices within nanotechnology. Furthermore, it advocates for extending these technologies to monitor the real-world behaviour of NMs delivery. Through its thorough investigation, this systematic literature review endeavours to address current obstacles and pave the way for the safe and sustainable utilization of nanotechnology, thereby minimizing associated risks.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanomaterials (NMs) are a significant breakthrough in global science and technology, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm in size and exhibiting exceptional chemical, physical, and biological properties. These characteristics make NMs crucial across various fields [1]. According to MarketsandMarkets, the global market for NMs is expected to reach $75.64 billion by 2025, with a strong annual growth rate of 13.2% from 2020 to 2025 [2]. NMs are integrated into everyday products such as cosmetics, sunscreen, food packaging, medicines, water filtration systems, and energy production. The development of nanomedicines and nanotechnology has brought numerous benefits to humanity, a trend likely to continue. However, it is increasingly important to address the potential negative effects associated with their use. Currently, many diseases arise from regular exposure to harmful chemicals or materials, whose risks are often hidden by their perceived benefits [3]. NMs enter our lives through food additives, industrial processes, processed foods, packaging materials, cigarettes, cosmetics, medications, paints, and propellants. These substances can threaten human health, causing diseases like Parkinson’s, cancer, Alzheimer’s, asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, arrhythmia, urticaria, vasculitis, dermatitis, Crohn’s disease, podoconiosis, thrombosis, and hypertension [4].

To ensure safety and well-being, comprehensive nanotoxicological testing is crucial. The rapid growth of the nanoparticle (NP) market poses significant challenges for regulatory oversight and safety assessment using traditional in vitro and in vivo techniques. The increasing speed and volume of data make it difficult to evaluate chemicals with conventional methods, particularly given the numerous chemical toxicological endpoints [5]. Therefore, a shift towards computational modelling methods is needed to assess and predict the risks associated with these particles. Such approaches can expedite assessments, save resources, and help develop a framework for better health outcomes. The growing importance, complexity, and versatility of machine learning (ML)-based information techniques have brought them to the forefront of various fields [6–10]. However, acquiring substantial data for these techniques is increasingly challenging [7,10]. Typically, educational data devices are used to create broadly applicable patterns but often have lower predictive accuracy in specific scenarios [11]. This trend has significantly impacted nanotechnologies and NMs, and this influence is expected to continue [10]. High-throughput NM manufacturing and characterization have received relatively less attention despite their potential for thorough analysis using inspection methods [10]. Future advancements in high-throughput synthesis, characterization, and ML modelling are anticipated to significantly enhance the chemical industry workforce [12].

It is essential to monitor recent advancements in ML reported by scientists dedicated to developing safer NMs [10]. These advancements should be adopted by those following in their footsteps [10]. Furxhi et al. [13] demonstrate a growing preference for nonlinear modelling techniques, moving away from the prevalent use of linear regression [14]. While these methods often confirm quantitative relationships between shape and properties, there is a noticeable shift towards understanding nanospecific capabilities through physicochemical interpretations rather than purely theoretical descriptors [10].

Despite ongoing debates and the lack of widespread consensus on statistical preprocessing strategies, regulatory guidelines and validation strategies for modelling sets are underused, despite their common application in quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) studies [10]. Templates for reporting versions in regulatory risk analyses of engineered NMs are suggested to provide well-defined and organized model descriptions [14]. These templates cover QSAR model reporting and are relevant to physiologically based kinetic (PBK) and environmental exposure models for NMs, offering a comprehensive overview of the computational model landscape for hazard assessment [10]. The absence of effective analytical methods complicates the verification of models and the assessment of their application and identity in risk evaluations [10]. Recent research from the EU has explored algorithms for measuring the residence times of engineered NMs, providing guidance in the REACH regulation [14].

Various sources have extensively discussed trends in partial and widespread automation relevant to nanotechnology, highlighting the automation of nanoscience, investigation of additives, and the development of self-contained experimental devices [10]. Techniques like pulsed laser deposition, chemical vapour deposition, biomolecular templating, and electrodeposition have been utilized for the automated or semi-automated synthesis of inorganic NMs [15]. Notably, the application of flow chemistry showcases the potential for automating the generation of assemblies for colloidal NP solutions, challenging previously held beliefs [16]. Interestingly, the article discussing NPs designed for medicinal purposes intentionally excludes references to automation, informatics, or ML modelling. The use of ML to assess potential negative consequences of NM datasets, following a “safe by design” approach, is gaining momentum, particularly with the collaboration of NM regulators [17]. Similarly, ML is used to model the toxicological properties of NMs by leveraging omics data. Recent reviews have highlighted the potential of combining integrative omics with ML to profile NMs and model their biological impacts for safety and risk assessments [18–20]. Over the past decade, various computational models and ML techniques have been developed to predict the toxicological properties and adverse effects of NPs [21]. Among these, QSARs and quantitative structure–property relationships (QSPRs) are the most commonly used methods [22]. Recently, the European Commission has launched several projects to explore the potential of modelling NP toxicity and properties [23,24].

The novelty of this article lies in its thorough systematic literature review (SLR) review of existing research on using ML and artificial intelligence (AI) to improve the sustainability and safety of NMs (NMs). Unlike other reviews, this study covers almost all relevant literature, showcasing the significant progress and potential of ML and AI in making NMs more sustainable. It also tackles interdisciplinary challenges and suggests new research directions, highlighting the role of these technologies in creating safer and more sustainable nanotechnology applications. In addition, the article offers detailed recommendations for future research at the intersection of nanotechnology and ML.

Up to the author’s knowledge, the present study possesses unique characteristics that distinguish it from earlier surveys:

Comprehensive SLR: Unlike previous studies, this article conducts an extensive SLR, covering nearly all existing literature on the use of AI and ML for evaluating the sustainability of NMs.

Rigorous methodology: It employs a predefined method for searching, selecting, and extracting data from articles, which reduces bias and ensures a thorough and systematic review process.

In-depth analysis: The article offers a detailed examination of the significance and application of AI and ML in enhancing the sustainability of NMs, highlighting key advancements and the potential benefits of these technologies.

Interdisciplinary challenges and future research: It addresses interdisciplinary challenges and suggests innovative future research directions, underscoring the essential role of AI and ML in fostering safer and more sustainable nanotechnology practices.

Detailed recommendations: The article provides specific recommendations for future research at the intersection of nanotechnology and ML, offering guidance for upcoming studies and progress in this field.

1.1 Research goals

This research aims to comprehensively investigate and analyze existing studies concerning the application of AI and ML in the realm of sustainability for NMs. This study is centred around six distinct research questions.

RQ1: What is the importance of AI and ML techniques in NM sustainability?

RQ2: What is the role of AI and ML tools in the identification of hazards associated with NMs?

RQ3: What are the applications of AI and ML in NM sustainability?

RQ4: What are the past NM sustainability roadmaps?

RQ5: What are the future NM sustainability roadmaps?

RQ6: What are the recommendations for future research in the intersection of nanotechnology and ML?

1.2 Contribution and design

In this SLR, we aimed to contribute to ongoing research on the sustainability of NMs and to enhance understanding of their applications across various scientific domains. Our key findings are as follows:

We conducted an SLR focusing on the sustainability of NMs, where we pinpointed 180 primary research articles from a pool of 395 pertinent studies.

We highlighted the significance of AI and ML techniques in NM sustainability.

We outlined the applications of AI and ML in enhancing NM sustainability.

We discussed both past and future roadmaps for NM sustainability.

We presented a detailed examination of the role of ML in assessment processes related to NM sustainability.

We provided specific recommendations for future research in the intersection of nanotechnology and ML.

Table 1 presents a comparison between our systematic literature review (SLR) and existing relevant surveys, considering four key criteria: methodology, number of database sources searched, time interval, and study focus. As shown in the table, our study is unique as it is the first to conduct a comprehensive SLR specifically focused on the integration of AI and ML in the sustainability and safety assessment of NMs. This highlights the novelty and thoroughness of our research approach, which stands out from previous surveys that either did not follow a systematic methodology, searched a limited number of databases, covered shorter time spans, or addressed broader, less specific topics.

Comparison of the proposed SLR with existing reviews

| Reference | Title | Year | Methodology | Databases searched | Time interval | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | A ML examination of NM safety | 2020 | Ordinary review | ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Google Scholar and PubMed | 2010–2019 | ML methodologies used to predict toxicological outcomes |

| [22] | Practices and trends of ML application in nanotoxicology | 2020 | Ordinary review | Google Scholar, Elsevier (Scopus and ScienceDirect), Web of science and PubMed | 2013–2022 | ML application in nanotoxicology |

| [11] | Role of AI and ML in nanosafety | 2020 | Ordinary review | — | — | Roadblocks to the application of ML to predict potentially adverse effects of NMs |

| [26] | Nanotechnology for a sustainable future: addressing global challenges with the international network4sustainable nanotechnology | 2021 | Ordinary review | — | — | Global challenges to sustainable nanotechnology |

| [27] | Overcoming roadblocks in computational roadmaps to the future | 2021 | Ordinary review | — | 2000–2020 | Roadmaps for the future of safe nanotechnology |

| [19] | ML-integrated omics for the risk and safety assessment of NMs | 2021 | Ordinary review | — | — | ML in risk and safety assessment of NMs |

| [10] | ML algorithms are applied in NM properties for nanosecurity | 2022 | Ordinary review | — | — | Roadblocks to ML in nanosafety |

| [28] | Using ML to make NMs sustainable | 2023 | Ordinary review | — | 2001–2022 | ML techniques for environmental risk assessment to ensure sustainability |

| Our proposed SLR | A comprehensive systematic literature review of ML in nanotechnology for sustainable development | 2024 | Systematic literature review | Springer, IEEE Xplore, ACM, Science Direct, Wiley, and Google Scholar | 2013–2023 | Significance of ML in advancing sustainability, hazard identification, and their diverse applications in NMs, evaluates past sustainability strategies for NMs while proposing innovative avenues for future exploration, and recommendations for future research |

This research aims to aid scholars in expanding their knowledge of NM sustainability. Moreover, by exploring the use of advanced technologies like AI and ML in this context and thoroughly assessing their pros and cons, we hope to lay the groundwork for further advancements in the field.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the research methodology. Section 3.3 presents the results of the study, Section 4 discusses future research recommendations, and finally, Section 5 presents the conclusion.

2 Research methodology

The research methodology employed in this study is the SLR, which is a well-established and commonly used approach [29]. This method involves systematically analyzing existing literature by following a predetermined set of steps to identify, assess, and interpret relevant research related to the research questions [29,30]. Figure 1 illustrates the entire process of the SLR.

The entire process of selecting articles for the SLR.

2.1 Data analysis tools and methods

To ensure a robust and reproducible analysis of the collected data, a variety of statistical tools and methods were employed. The approach involved several key steps:

2.1.1 Software utilized

Microsoft access: This software was used for database management, enabling efficient storage, retrieval, and manipulation of large datasets. Custom queries were created to filter and aggregate data as needed.

draw.io: This tool was employed to create detailed diagrams and flowcharts, which helped visualize data relationships, processes, and analytical workflows. This enhanced the clarity and understanding of the analysis steps.

2.1.2 Visualization

Data visualizations were generated using draw.io, to highlight key findings and trends. draw.io was specifically utilized to design flowcharts and diagrams that mapped out the data analysis process, providing a clear visual representation of the steps and methodologies used.

By integrating these statistical tools and methods, the analysis aimed to extract meaningful insights from the data, ensuring the results were accurate, reliable, and reproducible. The use of Microsoft Access for effective data management and draw.io for clear visualization of processes further enhanced the transparency and replicability of the study.

2.2 Searching article

Conducting searches in online repositories stands as an essential phase in conducting an SLR. It involves the initial formulation of a search string, which was made based on the recommendations provided for the SLR process [29]. This procedure entailed generating a search query involving key terms and their appropriate alternatives, applying different Boolean operators. Below is the whole search query used to choose the article.

((NM sustainability OR NM safety OR nanosafety) AND (artificial intelligence OR AI) AND (machine learning OR ML))

To locate relevant articles based on the stated search criteria, we performed searches on six distinct online digital databases: Springer, IEEE Xplore, ACM, Science Direct, Wiley, and Google Scholar (Table 2). These widely recognized online repositories are expected to provide extensive literature coverage on the subject matter. In addition, we employed manual searching and the snowballing technique, as described by Alzoubi et al. [30], to uncover additional pertinent articles. By using this search approach, we located a sum of 840 articles within the stated online repositories.

Results of the articles search

| Databases | First filtration | Second filtration | Third filtration | Final selection | Selected articles (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE Xplore | 28 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 0.56 |

| Google Scholar | 184 | 48 | 29 | 42 | 23.33 |

| Science Direct | 175 | 91 | 78 | 45 | 25.00 |

| ACM | 138 | 89 | 45 | 16 | 8.89 |

| Springer | 149 | 52 | 35 | 14 | 7.78 |

| Wiley | 166 | 94 | 72 | 27 | 15.00 |

| Snowballing | 0 | 25 | 13.89 | ||

| Manual search | 10 | 5.56 | |||

| Total | 840 | 395 | 264 | 180 | 100 |

2.3 Criteria for article selection

Various filters were used to select pertinent research articles (Table 3). Initially, a set of predetermined search terms was used to query particular online digital databases for research articles, leading to the discovery of 840 articles across six databases. Afterwards, during the second stage, an in-depth review of these articles took place focusing on the significance of the article title, abstract, and keywords. A total of 185 articles were picked in this stage, with others being excluded. Finally, in the third stage, complete articles were read, following the specific inclusion and exclusion conditions:

The research articles related to the sustainability of NMs.

The research articles were relevant to AI and ML techniques.

We included research articles that underwent peer review and were written in English.

We incorporated the latest editions of research studies.

Duplicate articles were excluded from the analysis.

Stages of article filtering

| Filtration | Technique | Criteria for evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Filtration 1 | Finding pertinent research articles from an online database | Keywords |

| Filtration 2 | Excluding research solely relying on the title, abstract, and keywords | Title, abstract, and keywords |

| Filtration 3 | Including papers based on their complete content | Full paper |

| Final filtration | Final chosen articles | Final selected papers |

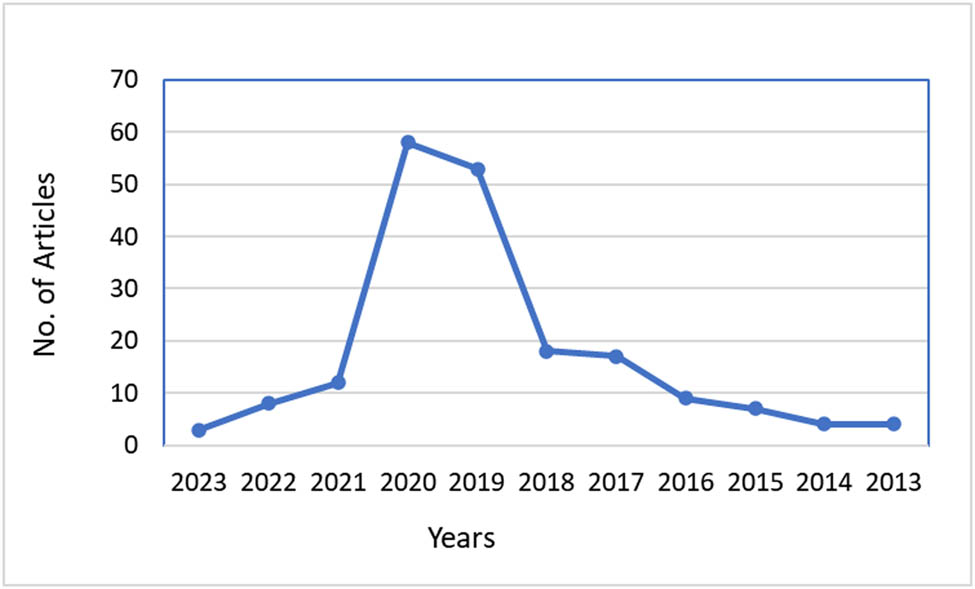

We selected 145 most relevant articles at the current stage. Subsequently, in the fourth stage, thirty-five articles were identified through manual and snowballing methods. In conclusion, a complete set of 180 relevant articles was finally selected for inclusion in this study (Figure 2). The search processes were performed on Oct 25, 2023, and all relevant research up to that date was incorporated.

Number of articles reference to each year.

3 Results

3.1 RQ1: What is the importance of AI and ML techniques in NM sustainability?

The process of exploring the biological characteristics of NMs involves several steps. First, the materials are synthesized and then subjected to relevant biological assays, generating a dataset used to train ML models [11]. Physicochemical attributes of NMs are transformed into mathematical descriptors, which are selected features from a pool and used in ML methods to build predictive models for desired properties [31]. These models are validated by predicting results for separate materials not involved in the model-building process.

In the realm of AI, AI encompasses tasks demonstrating human intellectual characteristics, while ML, as a subset of AI, accesses data, identifies patterns, and generates insights [11,32,33]. ML’s appeal lies in its versatility and platform technology functionality. Unlike traditional software, ML methods offer a more flexible approach, where the same algorithm and software program can be applied in various modelling situations, covering different materials and outcomes [34,35]. ML algorithms learn patterns from data similarly to human learning but with faster speed and an enhanced capacity to manage data with higher dimensions [36].

3.1.1 Traditional ML methods

Traditional ML methods encompass a variety of techniques, including regression, Bayesian networks, artificial neural networks (ANNs), genetic algorithms, decision trees, and support vector machines (SVMs) [37,38]. These techniques have been crucial in generating valuable models elucidating the biological properties of NMs, as extensively documented in the literature. While specific examples are discussed below, detailed explanations of these methods are omitted here due to their widespread usage and familiarity. For a thorough understanding, recent reviews and references specific to each method are recommended. Most computational models in the literature, illuminating the correlation between NM properties and biological endpoints, have predominantly utilized traditional statistical techniques. Particularly, conventional ML techniques with simple architectures, have been prominently featured in these models [39]. However, ML models [35] often lack awareness of complex environmental factors that can limit their operational effectiveness. With the increasing prominence of ANNs in broader scientific and technological fields, there is renewed interest in their application across various domains, including nanosafety and drug discovery [40]. This resurgence underscores a heightened recognition of the potential and versatility of ANNs, representing a notable evolution in their application within specialized domains.

3.1.2 Deep learning (DL) techniques

DL methods involve neural networks with multiple hidden layers and complex architectures. They have significantly impacted various fields of science and technology, particularly excelling in recognizing features in speech, images, and decision-making processes [41]. Unlike earlier simplistic approaches, contemporary DL methods have the advantage of automatically producing valuable descriptors during modelling. Researchers suggested in DL studies that deep and attention-based DL networks can achieve excellent performances [42–44]. Common DL-driven approaches are based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [45,46], recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [47], transformer models [36], generative adversarial networks (GANs) [48], and autoencoders [49]. CNNs, a type of supervised ML, are adept at identifying image features based on spatial correlations, focusing on local relationships in data and exhibiting resilience to minor alterations [12] (Figure 3).

The traditional ML techniques need feature engineering (top). The DL techniques automatically perform feature extraction and analysis (bottom).

A cascade of deep neural networks (DNNs) comprises two distinct networks: the first matches each material with an outcome, while the second links the outcome to one or more materials. This configuration, often referred to as an autoencoder, serves to both reduce dataset dimensionality and predict materials with specific properties based on the trained ML model. Generative adversarial networks GANs address the inverse mapping problem in materials design. GANs consist of a generator that produces trial structure–property models and a discriminator that evaluates the quality of these models against available unlabelled data. Originally designed to generate structures autonomously, GANs have proven effective in this capacity [12]. Similarly, active learning employs ML to select experiments efficiently to achieve predetermined goals, akin to directed evolution processes involving sequential generations of contestant structures undergoing selection, modification, and testing [12].

3.2 RQ2: What is the role of AI and ML tools in the identification of hazards associated with NMs?

ML techniques have become increasingly important for identifying hazards linked to NMs, with a strong emphasis on methods enabling thorough analysis, especially for managing large datasets and detailed content. This includes studying coronas of the protein around NMs when they interact with bodily liquids. ML shows significant promise in addressing read-across challenges, particularly in swift in vitro studies related to material properties, as indicated by a notable increase in attention (Table 4). The growing emphasis on computationally intensive network analysis further underscores its importance [50–53].

Application of ML and AI in hazard identification

| Reference | Year | Key info | ML Tools | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50,52,53] | 2019, 2019, 2020 | Hazard identification | High-throughput, network analysis | NMs hazard identification, protein corona analysis |

| [89] | 2020 | Detecting malformations | ||

| [90] | 2019 | Prediction of toxicity | Random forest | Predicting NM toxicity in zebrafish embryos |

| [91] | 2021 | ML correlation of NM parameters with in vivo toxicity in soil organisms | ||

| [92] | 2020 | ML-based graph theory for acute ecotoxicity prediction | ML graph theory | Acute ecotoxicity prediction |

| [118] | 2020 | ML method for analyzing earthworm movements | ANN-type recurrent self-organizing maps | Analyzing earthworm movements |

| [94] | 2019 | ML models for bioaccumulation and trophic transfer in conventional chemicals | ML bioaccumulation models | Studying bioaccumulation in conventional chemicals |

| [95] | 2020 | Random forests | Predicting HC50 values for conventional chemicals | |

| [96] | 2019 | ML techniques improving environmental species distribution models | Evolutionary/genetic algorithms | Improving species distribution models |

| [97] | 2020 | ML understanding of media effects on nanotoxicity | ML media effects understanding | Understanding media effects on nanotoxicity |

| [140] | 2011 | ML methods for identifying contaminants in sewage sludge | ML contaminant identification | Identifying contaminants in sewage sludge |

3.2.1 In vitro approaches

In vitro systems have traditionally been employed primarily in human health studies, but there is a growing trend in their application in environmental research is also dominant [28]. ML can optimize the process of learning new concentration-response curves through the use of nonlinear methodologies, potentially enhancing efficiency and accuracy in this aspect of research. Moreover, in hazard assessment, test platforms are often selected with the aid of integrated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA) or intelligent testing strategies (ITS) [54]. However, one notable limitation of ITS and IATA is their independence from the surrounding system, overlooking potentially crucial additional factors. The continuous evolution of sophisticated models suggests that future approaches may involve integrative ML multitasking methods. These methods could predict multiple toxicities simultaneously, mitigating the overfitting and employing techniques such as network analysis or forest trees [55,56]. Understanding mechanisms of action is crucial for comprehending hazards and facilitating risk evaluation. Omics data, including transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, serve this purpose but pose challenges due to their extensive variables [57,58]. ML offers an attractive approach to address the complexity and difficulty in identifying causal relationships within omics datasets [59–62]. While ML techniques find extensive application in omics, their application to materials and environmental risk is limited. Clustering techniques in omics analysis, while effective in finding patterns, lack explanatory power for mechanisms. Refined techniques like model-based approaches, especially when structured with known classes, provide more information on potential mechanisms [59,63]. The challenge lies in identifying causal relationships between omics expression levels and phenotypic outcomes, which ML techniques, mechanism-based or employing logic networks, can address, led by training data for causality verification [64–68]. The use of ML should align either with a highly mechanistic approach for identifying mechanisms or as a means to verify consistency with existing mechanistic understanding. In another method, ML approaches are utilized as supplementary investigative instruments rather than definitive identifiers [69–73]. Special attention must be given to the input data in dealing with complex omics data, as biases in input data can propagate through automated algorithms, impacting the final output and posing challenges when employing ML methods. This challenge is not limited to ML techniques alone; rather, it is crucial to confront them to guarantee impartial and dependable outcomes. In addition to omics approaches dedicated to the inner workings of cells, various other omics methodologies play an important role in environmental research, such as genetic barcoding for species diversity analysis, provide ideal datasets for ML applications [74–76]. In summary, environmental omics generates extensive data necessitating automated analysis to consistently identify underlying mechanisms of action.

In environmental studies, particularly those involving (smart-)NMs, in vitro techniques are gaining prominence [77]. ML approaches effectively enhance the usefulness of in vitro techniques by swiftly producing large datasets using high-content and high-throughput methods. This capability allows for the concurrent investigation of multiple materials under comparable circumstances [78,79]. ML approaches such as NNs and RF algorithms can be used with the obtained datasets to find similarities between materials by detecting patterns [80–82].

ML techniques for image analysis are also applicable to these datasets, enabling the quantification of processes during experiments, such as agglomeration, which significantly influences exposure [83–86]. However, ML image evaluations require a large and well-labelled dataset for training. Furthermore, in vitro studies can be used to determine the makeup of NMs protein coronas (PCs) [87]. For instance, Findlay et al. [88] employed existing data on bacteria and yeast to assess the effectiveness of different ML methods in foreseeing the formation of PC on basic Ag NPs, and how it correlates with the NPs’ chemical and physical attributes. Their research revealed that ML approaches allow the prediction of PC composition through conventional experimental data and readily available details about the biophysical behaviours of proteins. In summary, ML plays a vital role in uncovering attributes in in vitro analysis, and automation can contribute to enhancing repeatability.

3.2.2 In vivo approaches

In environmental hazard identification, initial tests typically involve in vivo experiments, which are considered a key aspect in many testing guidelines [28]. While ML techniques have been widely used to assess the toxicity of traditional chemicals and address environmental concerns, their application to smart NMs has been limited. Notable studies in this area include Karatzas et al. [89], who used an ML approach to automatically detect abnormalities and classify affected Daphnia organisms after exposure to silver and titanium NMs. To et al. [90] developed an ML technique using RF for predicting the harmful effects of metal-containing NMs on zebrafish embryos based on their physical and chemical properties. Similarly, Gomes et al. [91] employed ML to establish a link between various parameters of NMs and the toxicity experienced by soil organisms when exposed to different types of titanium dioxide (TiO2) materials infused with iron (Fe).

A range of ML methods is used to forecast the potential toxicity of traditional chemicals within living organisms. For instance, ML-driven graph theory has been employed to anticipate severe ecotoxicity, drawing insights from datasets such as AIST-MeRAM and ECTOX for estimation and assessment purposes [92]. In a different context, Ji et al. [93] implemented an ANN-based recurrent self-organizing map to examine the locomotion patterns of earthworms after their exposure to copper sulphate (CuSO4). This method holds significance in assessing the behavioural responses of worms following exposure to various copper-based (smart-)NMs. Trophic transfer and bioaccumulation, essential endpoints in environmental risk assessment, have been studied using linear models and ML techniques for traditional chemicals in invertebrates and fish [94]. Although ML has not been extensively applied to these endpoints in NMs, its potential is evident. In addition, ML models like random forests have been successful in predicting hazard concentration levels (HC50) for traditional chemical materials, suggesting the possibility of extending these models to NMs [95].

Environmental species distribution models, crucial for identifying potential effects, can be enhanced using ML techniques, as demonstrated by studies using evolutionary/genetic algorithms [96]. ML can also aid in understanding the effects of nanotoxicity, drawing insights from studies on conventional chemicals [97]. A significant source of NM emissions called “Sewage sludge,” could benefit from ML applications in identifying important contaminants and understanding their impact on soil and crops [98]. While previous studies focused on conventional chemicals, similar ML methods could be applied to smart NMs. Beyond direct applications to current environmental risk assessment practices, ML shows promise in handling larger datasets and integrating more complex tests [28]. Examples include using ML in animal species classification, predicting avian field biodiversity, and using DL for continuous camera monitoring to identify invertebrate species [28]. It is widely applicable in real-time analysis like in surveillance applications [99]. They suggest that ML can facilitate the combination of diverse datasets and predict NM toxicity under various scenarios, highlighting its relevance in hazard assessment and risk management [28].

3.2.3 Exposure analysis

Critical components of analyzing the fate and exposure of substances include evaluating environmental releases, forecasting substance levels in the environment, and understanding accumulation in organisms, which can be done at various scales [28]. The soil compartment is highlighted as the main sink for (smart-)NMs [28]. Various statistical and logical models have been utilized for predicting environmental concentrations, often requiring intensive data calculations [28]. Studies like Wigger et al. [100] have shown that combining various modelling techniques with ML can significantly improve the effectiveness of these models. Wikle employed ML, particularly NNs and deep hierarchical models, to predict changes in soil moisture in large geographic areas [101].

Moreover, ML has been utilized to a restricted degree in simulating the destiny and potential exposure of NMs [28]. Notably, Goldberg et al. [102] pioneered the use of ML to develop advanced fate models for NMs. Their work demonstrated that decision trees, including RF regression and classification, proved effective in identifying previously concealed key descriptors crucial for huge models. The authors highlighted the advantage of ML approaches, emphasizing their relative lack of restrictions due to the absence of prior linearity assumptions. However, a significant hurdle reported by the authors was the scarcity of data, encompassing both quantity and quality concerns. Subsequent studies, such as that by Babakhani et al. [103], leveraged ANN to investigate the transport of NMs in porous media. The study revealed that the ANN-based correlation technique outperformed existing empirical approaches in forecasting continuum model attributes and breakthrough models. These approaches hold promise in supporting other NM-specific fate models like Simplebox. Developing ML-based models specific to NM species becomes crucial, particularly because (smart-)NMs deviate from the fate and exposure models applied to traditional chemicals. Unlike chemicals assuming a steady-state condition, NMs exhibit characteristics like agglomeration/aggregation influenced by surface properties [104].

Fazeli-Sangani et al. [105] examined the effect of various features of soil and experimental variables on the movement of TiO2 in actual soil environments using data analysis techniques. Several methods such as multiple linear regression, random forest, classification and regression trees, and ANN were utilized for this purpose. Their results showed that ANN outperformed RF in predicting TiO2 transport, despite RF needing less input data. MLR techniques generally performed poorly, and CART had good calibration but poor validation. In addition, various researchers have used ML to predict environmental parameters important for fate and exposure modelling, especially in studies on soil carbon and nitrogen distributions. Pinheiro et al. [106] utilized ML, specifically regression trees, to predict soil texture through digital soil mapping, with applications in remote sensing data. These environmental ML techniques are crucial for developing local and regional predicted environmental concentration models, essential for environmental risk assessment. In addition, ML has potential to predict exposure and toxicity throughout a material’s life cycle, though this application remains underexplored. Furthermore, since organisms in nature are mostly exposed to mixtures of chemicals and materials, mixture modelling is another vital area in risk assessment where computational methods, including ML, could provide valuable insights.

3.2.4 Risk classification

During the risk assessment phase of an environmental risk assessment, the primary objective is to systematically amalgamate data related to material features, exposure, and hazards to establish a robust environmental evaluation [28]. Traditionally, this process employs tools featuring decision points based on material description, exposure, utilizing fate, and hazard data, often incorporating IATA [28]. Consequently, decisions are required regarding data selection and integration, frequently employing simple decision trees with predefined structures and binary decisions. The risk measuring paradigm aligns with ML approaches; however, ML presents the possibility of employing more intricate decision tree structures to substitute traditional IATAs [28]. In other domains, ML-based methodologies have been explored for risk assessments, such as the evaluation of flooding risks [107] and soil quality based on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) pollution [108].

As highlighted earlier, the pursuit of automation is a crucial objective in risk assessment, driven by the need for efficiency and cognitive relief for human risk assessors facing time constraints and cognitive overload due to numerous assignments requiring critical decisions without sufficient time for exhaustive data review [109–111]. In a real risk assessment where the combination of exposure, fate, and hazard data significantly influences the outcome, the choice of data and data treatment techniques, such as ranking, logical choice, ranking, or statistical techniques, play a crucial role [112]. Some ML-based methods opt for predictive approaches, sidestepping conventional explaining statistics [112]. The potential incorporation of various data and possibly new methods implies that upcoming risk assessment experts and scientists will need to navigate and select from diverse analytical frameworks, leading to varying approaches in evaluating statistical significance and importance [113–116]. This holds relevance in both the middle and ultimate phases of a risk assessment [117]. Considering the likelihood of future risk assessment methods incorporating network analysis [118], it becomes clear that risk assessors may face increasingly complex situations. In these cases, despite using advanced DL techniques, it may be not easy for anyone to fully understand the entire data processing and its outcomes, effectively making the assessment a black-box system. This challenge, familiar to those assessing conventional chemicals, is expected to intensify with the added complexity of smart-NMs [28]. This issue is particularly evident when data-intensive models, such as most ML/AI models, are applied to smaller datasets, even with validated background models [28].

However, by using appropriate data and a well-designed model-flow, new automated models are expected to deliver faster and more standardized calculations, enabling more comprehensive risk analyses than previously possible [119–121]. These models can, for example, connect exposure and toxicity parameters to global weather patterns, sea currents, soil–water flow models, and known biodiversity distributions using local/global models [122,123]. This advancement could enable the rapid integration of additional data, allowing chemometric, biometric, and risk data to be collaboratively processed with ML techniques [124]. Employing various ML techniques, such as symbolic regression, may also uncover additional biological or ecological “laws” [125].

Nonetheless, it is important to note that ML methods may encounter reproducibility challenges, especially when handling highly complex data and models [28]. A fundamental concern underlying environmental risk assessment involves the uncertainty and sensitivity associated with the outcome, represented as a value with related statistics [28]. Uncertainty arises from various sources, such as the lack of adequate input data or the selection of potentially “incorrect” input data, hindering the models from effectively addressing the risk [126]. Incorporating M does not alleviate this problem; in fact, it may further obscure the issue, particularly when using hidden layers, making it less certain which data influences the outcome. ML is generally acknowledged as data-hungry, emphasizing the heightened importance of acquiring sufficient data of high quality [28]. Sensitivity, a crucial aspect of ERA concerning how well it can capture a true effect, is also relevant to ML techniques, encompassing features like specificity and accuracy, integral to predictiveness training through training sets [28]. However, determining how an ML model is derived, especially when using deep or reinforcement learning methods involving temporary virtual nodes, can be challenging [28]. This issue can be partially addressed by employing robust adversarial controls [127]. It is also important to recognize that correlations are often misinterpreted as causality in traditional data analysis.

In the context of risk management, Hino et al. [128] presented that ML techniques can enhance the effectiveness of public agencies in meeting regulatory objectives. They trained a regression forest model to predict which facilities were at risk of failing inspections and used the model’s risk scores to propose alternative allocations of Clean Water Act inspections. These alternative strategies nearly doubled the detection rate of violations during inspections, with an increase of over 600% under the most aggressive reallocation scheme. In addition, Duan et al. [129] applied ML within a multimedia system to compare traditional environmental chemistry with ML methodologies. Forest et al. [130] highlighted the importance of selecting the appropriate endpoint in ML systems for assessing human health hazards. These studies underscore the potential for ML-based techniques from a regulatory perspective. A widely discussed topic in nano environmental health and safety (nano EHS) revolves around the potential of current ML techniques, such as read-across, classification, or ranking tools, to facilitate the grouping of materials that would otherwise be challenging to classify [111,131]. As previously mentioned, these techniques also hold promise for identifying new materials with specific properties [132,133].

ML tools must be designed to seamlessly interface with the Internet of Things (IoT) to be effectively applicable in various contexts [134]. The integration of IoT with ML applications in environmental settings [135] has the potential to facilitate comprehensive online risk management, such as precision agriculture and farming practices utilizing drone technologies [136]. This encompasses tasks like automatic regulation and enhancement of production sites, machinery, agricultural robots, and irrigation systems for the implementation of water quality measures, soil moisture control [137], and promotion of behavioural changes [138]. Nevertheless, the extensive capabilities afforded by such integration pose significant legal and ethical challenges [139] and carry the risk of potential large-scale misuse, such as through hacking. The integration of IoT remains a crucial consideration in contemporary ML implementations, enabling ML systems confined in virtual spaces to directly influence the physical world on a significant scale without human intervention [28].

3.3 RQ3: What are the applications of AI and ML in NM sustainability?

NMs are ubiquitous in modern life, present in food additives, industrial processes, cosmetics, medications, and more, with the potential to cause a range of health issues from Parkinson’s disease to cancer (Figure 4) [2,4,141]. However, evaluating their safety through conventional methods is challenging due to the rapid proliferation of NPs and the complexity of the data involved. To address this, a shift towards computational modelling methods is crucial, offering the promise of faster assessments, resource conservation, and the establishment of a unified framework for promoting better health outcomes.

![Figure 4

The potential origins (inner circle) and the resultant health effects (outer circle) stemming from exposure to NMs [2].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2024-0069/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2024-0069_fig_004.jpg)

The potential origins (inner circle) and the resultant health effects (outer circle) stemming from exposure to NMs [2].

Numerous reviews on the use of ML techniques in nanotoxicology were conducted over the past decade, as evidenced by various sources [142]. We present key examples of published research to illustrate the diverse ML approaches utilized for modelling NM properties across various applications (Table 5). Our selection aims to showcase the breadth of ML applications in predicting NM hazards and outcomes in “safe-by-design” projects, emphasizing technologies that hold promise in achieving predefined milestones.

Application of ML and AI in nanosafety

| Reference | Year | NM type | ML techniques | Biological effects studied | Performance metrics | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puzyn et al. [143] | 2011 | Metal oxide NPs | One-parameter linear regression | Cytotoxicity against Escherichia coli | Developed a linear regression model to predict cytotoxicity | |

| Epa et al. [144] | 2012 | Metal oxide NPs | Linear regression, Bayesian neural networks | Smooth muscle cell apoptosis, NP uptake | Standard error, Predictive accuracy | Created predictive models for accurate predictions for apoptosis and uptake |

| Liu et al. [146] | 2013 | Iron oxide core NPs | Self-organizing map, Bayesian classifier, logistic regression, linear discriminate analysis, nearest neighbor classifiers | Impact on four cell types, using various assays | Relatively high accuracies exceeding 78% | Effective classification models for assessing the impact of iron oxide core NPs on different cell types |

| Gernand et al. [149] | 2014 | Carbon nanotubes | Classification and regression trees, random forest | Pulmonary toxicity |

|

Demonstrated robust predictive capabilities for pulmonary toxicity, identifying key attributes contributing to toxicity |

| Mikolajczyk et al. [150] | 2015 | Metal oxide NPs | Linear regression | Zeta potential | RMSE error,

|

Predicted zeta potentials with RMSE error of 1.25 mV and

|

| Papa et al. [147] | 2015 | TiO2 and ZnO NPs | Multiple linear regression, neural networks, support vector machines | Cytotoxicity assessed through lactate dehydrogenase levels | Errors ranging from 8 to 17% relative to control cells | Nonlinear ML methods outperformed near-regression models, accurately predicted LDH levels |

| Chen et al. [148] | 2016 | NMs | Various tree algorithms (functional tree, decision tree, random tree) | Ecotoxicity classification for multiple species | Accuracies of 93 and 100% for predicting toxicity to Danio rerio in training and test sets. | Achieved accurate classifications for LC50 global models |

| Fourches et al. [39] | 2016 | Carbon nanotubes | k-Nearest neighbors, random forest, Support vector machines | Various biological endpoints including acute toxicity | Predictive accuracies of up to 77% | Predicting biological endpoints and screening potential surface ligands |

| Le et al. [152] | 2016 | ZnO NPs | Linear regression, Bayesian neural network | Biological responses in human cells (cell viability, membrane integrity, oxidative stress) | High

|

Nonlinear ML models outperformed linear ones, modelling entire NP dose–response curve |

| Oksel et al. [153] | 2016 | NMs Genetic programming-based decision tree (GPTree) | Nanostructure–activity relationship modelsv | Training accuracy = 98–100%, Test accuracy = 86–100% | GPTree provided accurate nanoSAR models | |

| Concu et al. [154] | 2017 | Metal, metal oxide, and silica NPs | Linear neural networks, radial basis functions, multilayer perceptrons, probabilistic neural networks | Ecotoxicity and cytotoxicity across various organisms | Area under ROC curve values of 0.999 for the training set and 0.998 for the test set. 98% two-class accuracy in the test set | Exceptional predictive accuracy for diverse NPs |

| Wang et al. [155] | 2017 | Gold NPs | k-Nearest neighbors | Cellular uptake, induction of oxidative stress, hydrophobicity | High cross-validated predictivity | Demonstrated efficacy in predicting various NP properties |

| Fourches et al. [142] | 2017 | Various NPs | Support vector machine, kNNs-based regression | Various toxicological properties | External prediction accuracy | 73% external prediction accuracy for classification models and

|

| Kovalishyn et al. [156] | 2018 | Inorganic NMs | k-nearest neighbours, random forest, neural networks | Toxicological or ecotoxicological properties and physicochemical properties |

|

Developed models for diverse endpoints, providing predictive power for toxicological/ecotoxicological properties |

| Hataminia et al. [157] | 2019 | Iron oxide NPs | Neural network | Toxicity on kidney cells | Specific statistical values not provided in the graphs | High predictability in modelling toxicity, detailed analysis of input parameters on kidney cell viability |

| Lazerovits et al. [67] | 2019 | NPs | Supervised DNN | Adsorption of blood proteins, blood clearance, organ accumulation | Accuracy

|

Complex protein pattern on NP surfaces predicts organ uptake |

Puzyn et al. [143] demonstrated the utilization of ML and statistical techniques to forecast the adverse characteristics of NMs. They developed a simple linear regression model with a single parameter to forecast the cytotoxicity of 17 distinct metal oxide NPs against Escherichia coli. The model used descriptors acquired from quantum chemical calculations. Similarly, Epa et al. [144] employed Bayesian regularized neural networks and linear regression for the prediction of biological effects associated with 51 metal oxide NPs including different 109 metal oxide NPs and metal cores having distinct cores but differing surface modifiers. These models assisted numerical forecasts concerning the apoptosis of flat muscle cells and the uptake of NP concentration by human pancreatic cancer cells and umbilical vein epithelial cells during in vitro experiments. They exhibited predictive accuracy in a separate test batch of NMs, with an error of

Papa et al. [147] analyzed the ZnO and TiO2 NPs’ cytotoxicity, utilizing experimental descriptors and testing different concentrations to assess their impact on disrupting lipid membranes in cells, measured through lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. They developed models employing SVMs, linear regression, and neural networks. These models exhibited accurate predictions of LDH levels in the testing while errors ranged from 8 to 17% compared to control cells. Notably, the nonlinear ML techniques surpassed the performance of the near-regression models. To overcome the limitation of available toxicity data, Chen et al. [148] used ML techniques for the classification of NM ecotoxicity. They applied read-across attributes calculated from various sources of ecotoxicity data to develop models tailored to specific species and a joined model capable of predicting toxicity across various species. Employing various tree algorithms, including decision tree, functional tree, and random tree techniques, they achieved accurate classifications for LC50 global models, correctly identifying over 70% samples in training and testing. Remarkably, the functional tree demonstrated high accuracies of 93 and 100% for predicting the toxicity of metallic NPs to Danio rerio in training and testing, respectively.

Gernand et al. [149] conducted an investigation utilizing classification and regression techniques (regression trees and random forest) to forecast the pulmonary toxicity of 17 varieties of carbon nanotubes. The utilized model incorporated descriptors associated with the nanotubes’ categories and dimensions, coverage time and dose, concentrations of metallic impurities, and features of the visible rodents. The pulmonary toxicity measures consisted of assessing the levels of macrophages and neutrophils, as well as concentrations of LDH and the total number of proteins. The models exhibited strong predictive capabilities for the four pulmonary endpoints, achieving

A revolutionary study by Fourches et al. [39] implemented the principles of “safe-by-design” by employing ML techniques to assess biological outcomes. The investigation centred on an 83-member library of surface-modified carbon nanotubes having consistent dimensions. Various biological activities, including carbonic anhydrase, bovine serum albumin, chymotrypsin, hemoglobin activity, and in vitro analyses for immune toxicity and acute toxicity, were meticulously examined. By leveraging conventional ML models such as kNNs, SVM, and random forest, they achieved impressive predictive accuracies, reaching 75% for protein binding and 77% for acute toxicity outcomes. The study revealed chemical surface features associated with specific biological actions, leading to the virtual screening of a huge library having 240,000 impending carbon nanotubes’ surface ligands. Experimental validations of these predictions demonstrated remarkable accuracy. This systematic approach, involving the modification of physicochemical properties, comprehensive biological evaluation, and computational examination, aligns seamlessly to forecast nanotoxicology outcomes and the principle of designing safety into NMs. It significantly contributes to advancing the automated comprehension of nanobio interactions and aids the development of quantitatively predictive and vigorous models for NM characteristics within applicable domains [151].

In a similar context, Le et al. [152] investigated 45 ZnO NPs, systematically altering particle dimensions, doping type, shape proportions, dopant density, and surface finishing. The biological response data resulting from this experimentation was modelled using Bayesian regularized NN and linear regression ML techniques. The biological analyses encompassed evaluations of membrane integrity, cell viability, and oxidative stress, describing the damage caused to human liver carcinoma cells (HepG2) or human umbilical vein endothelial cells by ZnO NPs. The nonlinear ML models demonstrated superior performance compared to the linear counterparts, offering predictions for an external test set with remarkable

Oksel et al. [153] introduced a new strategy employing a genetic programming-based decision tree (GPTree) to depict NM properties. This method, known for its robustness and automation, excels in constructing precise nanostructure–activity relationship (nanoSAR) models, especially when confronted with limited datasets. GPTree autonomously identifies relevant descriptors, confirming model accuracy while improving interpretability. Indicating its adaptability, the approach effectively developed precise nanoSAR models for four different datasets. Particularly, these models showed parsimony by utilizing solely thirteen (13) predictors from a wide collection of descriptors, attaining high accuracies going from 98 to 100% during training and 86 to 100% during testing, correspondingly. The decision trees generated by GPTree provided visually intuitive representations of decision thresholds associated with each descriptor, considerably improving the interpretability of models predicting the structure–activity link of NPs.

Concu et al. [154] conducted an extensive study involving 260 silica, metal, and metal oxide NPs encompassing 31 chemical compositions from various literature sources. Their investigation included measurements of ecotoxicity and cytotoxicity across a spectrum of organisms, and bacteria, spanning algae, fungi, plants, fishes, crustaceans, and mammalian cell lines. Through random combinations, they generated 54,371 pairs of NPs, with training (40,804 pairs) and test sets (13,567 pairs) formed randomly. Employing linear NNs, radial basis functions, multilayer perceptrons, and probabilistic NNs, the models demonstrated outstanding predictive precision, achieving an area in the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve values of 0.99 and 0.998 for the training and testing, respectively. The two-class accuracy for the test set reached 98%. These models also provided insights into the descriptors influencing adverse biological responses. Despite employing Y-scrambling to assess overfitting, the authors noted the challenge posed by unrealistically improved accuracy and ROC values, raising concerns about potential chance correlation problems in the models.

Wang et al. [155] analyzed NPs of gold, exploring variations in size, surface modifications, and surface coverage. Their NP collection comprised 34 particles, and by employing 29 descriptors along with the kNN algorithm, they created predictive models for the absorption of substances by human kidney cells and lungs, the capacity to activate oxidative stress and hydrophobicity. Both models, incorporating 11 or fewer descriptors, demonstrated excellent predictability during cross-validation, with

Kovalishyn et al. [156] compiled a dataset from 128 literature sources, incorporating 964 data points for inorganic NMs. Their analysis encompassed toxicological/ecotoxicological properties (EC50, MIC, LC50, and mortality rate) as well as physicochemical characteristics for metal and metal oxide NPs within the size range of 1–90,000 nm. Utilizing random forest, kNN, and NN techniques, models were developed for these endpoints across various species. Evaluation of model predictive power through cross-validation and test sets yielded

Hataminia et al. [157] utilized an NN to simulate the nephrotoxicity induced by iron oxide NPs on kidney cells. The model, which underwent training based on NP size, concentration, incubation duration, and surface charge, demonstrated high predictability, although specific statistical values were not provided in the graphs. The study extensively analyzed the impact of these four input factors on the viability of kidney cells. While DL algorithms have made a substantial impact in various fields, including materials science, their application to modelling NM properties relevant to nanosafety has been limited [158]. The DNNs can automatically produce higher features for ML models. Surprisingly, this capability has not been widely explored in predictive nanotoxicology, likely due to the shortage of nanospecific descriptors hindering progress.

Most applications of DL algorithms involve utilizing their image recognition capabilities for extracting microscopy image data of NPs/cells. Similarly, Coquelin et al. [159] used CNNs to estimate particle size distribution from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of aggregated TiO2 particles, aiming to automate SEM measurements. Context encoding was introduced to forecast absent components of combined NPs. Rusk et al. [160] applied the CNNs techniques for the segmentation of transmission electron microscopy images for different reliable size distribution calculations. Ilet et al. [161] employed image analysis utilizing open-source software tools, CellProfiler, along with a CNN algorithm named ilastik, to study NP distributions.

Lazerovits et al. [67] presented a significant utilization of ML in the area of nanosafety. Their study examined how blood proteins adhere to NPs after intravenous injection. Through the employment of data from protein mass spectrometry as inputs and correlating them with blood clearance and organ accumulation as outputs, they effectively trained a supervised DNN. The results from the network accurately anticipated the accumulation of NPs in the liver and spleen, revealing the considerable impact of the intricate protein pattern on the NP surface on organ uptake. This valuable insight has delivered a basis for the advance of NPs with obviously reduced accumulation in the liver and spleen.

3.4 RQ4: What are the past NM sustainability roadmaps?

Over the past decade, several significant roadmaps for the safe utilization of NMs have been proposed. The primary comprehensive set of milestones was established at a workshop sponsored by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) in 2011, focusing on Quantitative Nanostructure Toxicity Relationships held in Maastricht [162]. The milestones acknowledged in this roadmap and subsequent reviews emphasized crucial aspects for advancing NM research, including:

Improved material characterization for biological activity trials.

Creation of NM-oriented descriptors.

Development of high output in vitro methods.

Enhanced tracking techniques for NPs in the body.

Improved data storage/sharing.

Production of in vivo data.

Development of models for predicting NP behaviour.

These milestones, originally research-driven, have significantly influenced research agendas in Europe and the United States. The Maastricht roadmap, in particular, played a pivotal role in securing European Union funding and was used in governmental policies on NM safety, including the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology [162]. The roadmap’s impact is further reflected in the funding of numerous associated COST Actions, as well as now Horizon projects (2020) focusing on nanosafety [52,86,109,163,164,165]. Despite the passage of time, many milestones from the initial Maastricht workshop remain pertinent due to slower-than-expected progress in achieving them. Factors contributing to this slower progress include the delayed adoption of high-throughput characterization and synthesis technologies, resulting in a scarcity of big and robust datasets for ML model training and a lack of interpretable and efficient NMs descriptors.

To address these challenges, Worth et al. [166] proposed a recent US and EU Roadmap of nanoinformatics up to 2030, with a specific emphasis on using computational methods to predict potential adverse effects of NMs. This roadmap aligns with the previously identified milestones and emphasizes the need for continued efforts in nanosafety research. Different milestones of 2-, 5-, and 10-year duration have not been fulfilled, emphasizing the importance of ongoing efforts. To tackle these challenges, significant initiatives financed by the EU Horizon 2020 program aim to establish joint networks of scientists dedicated to crafting computational solutions for predicting nanosafety. These projects focus on generating relevant data, implementing nanoinformatics-driven decision-support strategies, and developing methodologies for safe-by-design NMs.

Challenges faced by regulators include adapting to a fast-varying system of industrial NMs. The NanoReg2 initiative deals with this problem by linking structure-based design to the regulatory procedure, verifying new NMs through established grouping methods. NanoSolveIT employs a nanoinformatics-centred decision-support methodology, utilizing advanced in silico techniques to recognize key features of NMs accountable for unfavourable effects.

Horizon 2020 includes 67 toxicology-related projects, including 11 focused on NM toxicity, underscoring the commitment to advancing research in this field [www.fabiodisconzi.com/open-h2020/per-topic/toxicology/list/index.html]. Recent literature also emphasizes the need for sustainable nanotechnology system governance for European society [167], aligning with the efforts of regulatory and standardization communities, such as FDA, EPA, ECHA, ISO, and OECD, in developing approved techniques for measuring inherent and external attributes of NMs.

3.4.1 Data

ML techniques hold significant potential for modelling and predicting both advantageous and detrimental characteristics of NMs. Their appeal arises from their rapid processing, independence from intricate mechanistic models, utilization of open-source and accessible technologies, and demonstrated effectiveness in discerning patterns within intricate datasets across various domains [168]. As methods grounded in data-driven principles, their efficacy is inherently tied to the information employed in their creation. The abundance, quality, diversity, and scope of data play pivotal roles in crafting resilient and anticipatory ML models that can be widely applied across diverse domains.

3.4.2 Quantity of data

The progress of nanosafety research projects faces significant challenges due to the scarcity of substantial datasets, primarily attributed to the time, expenses, and ethical concerns related to collecting data involving animals and humans. Unlike the assessment of properties in isolated, well-defined organic pristine or molecules NMs unaffected by biological environments, evaluating the NMs features that exhibit variations with time or in diverse biological fluids lacks standardization and poses technical complexities [169]. To address these limitations, read-across techniques computational models and computational models are employed to bridge data gaps [167]. However, the optimal approach is unquestionably the expansion of available datasets. In the past, advancements have been made in the high-throughput synthesis of NMs [170], accelerated physicochemical features [171], and swift in vitro toxicity screening [172,173]. The ongoing development, widespread practice, and use of these high-throughput approaches hold great promise for substantially augmenting the volume of NMs in the upcoming years.

3.4.3 Quality of data

In addition to challenges associated with the scale of datasets, similar to other material types, issues frequently arise regarding the data reliability of experiments on the biological and physicochemical impacts of NMs. Constraints related to time, cost, and ethical considerations not only limit the quantity of available data but also impact the feasibility of conducting multiple experimental replicates. These constraints have repercussions on the quality of data, signal-to-noise ratio, and the identification and handling of outliers. The reproducibility of scientific findings has emerged as a critical concern in recent years, with specific attention directed towards NMs. Various research groups have contributed methodologies aimed at enhancing the reproducibility of NM synthesis [174–177]. Addressing the reproducibility of NM bioassays, Petersen et al. [178] have made significant contributions, while Baer et al. [179] have explored the influence of materials provenance on reproducibility.

Accompanying experiments on NMs offers greater challenges as compared to small organic molecules, mainly due to intrinsic differences in their shape and size, tendencies to agglomerate, and the creation of corona. Identifying the complexity of these features, researchers are actively striving to improve experimental duplicability. Baer et al. [179] and Petersen et al. [178] have explored different features of NM bioassays and the impact of material sources on reproducibility, respectively. Notably, Galmarini et al. [180] studied the sophisticated effects of corona formation on experimental reproducibility.

3.4.4 Diversity

In conclusion, it is imperative to develop broadly applicable models for predicting potential negative characteristics of NMs. These models should be trained using data obtained from a diverse array of NMs and encompass a comprehensive range of relevant biological endpoints. Recent papers have underscored the importance of conducting systematic studies that explore various NM morphologies, types, and endpoints [151,181].

3.4.5 Description

NPs exhibit various attributes, such as agglomeration, dissolution, photocatalytic properties, and the formation of persistent complexities with biological ions. These characteristics significantly impact the biological behaviour of NMs [126,182,183], although advancements have been achieved in discerning the location, timing, and methodology for characterizing NMs, it remains challenging due to the dynamic nature of NM characteristics, which can vary considerably under various circumstances and with time. Further, these varying characteristics are highly responsive to the environment, with interactions among properties adding complexity to the characterization process.

Ideally, it is preferable to evaluate the physicochemical features of NMs within comparable biological situations, as the original characteristics of NMs tend to vary when they come into connection with biological liquids [184]. NM surfaces rapidly develop a biological layer, making a bio-corona that modifies material properties like surface charge, particle dimensions, and aggregation status quickly [185]. The corona experiences dynamic changes over time, with primarily attached macromolecules being gradually replaced by those with stronger affinities. Additional investigation is essential to fully recognize how NMs’ physicochemical properties, including surface chemistry, size, aggregation, and dissolution, are adapted in different biological settings. It is crucial to determine whether these modifications make NMs more or less toxic compared to their original state. This information is crucial for regulators to more accurately measure the risks posed by NMs to human/environmental health.

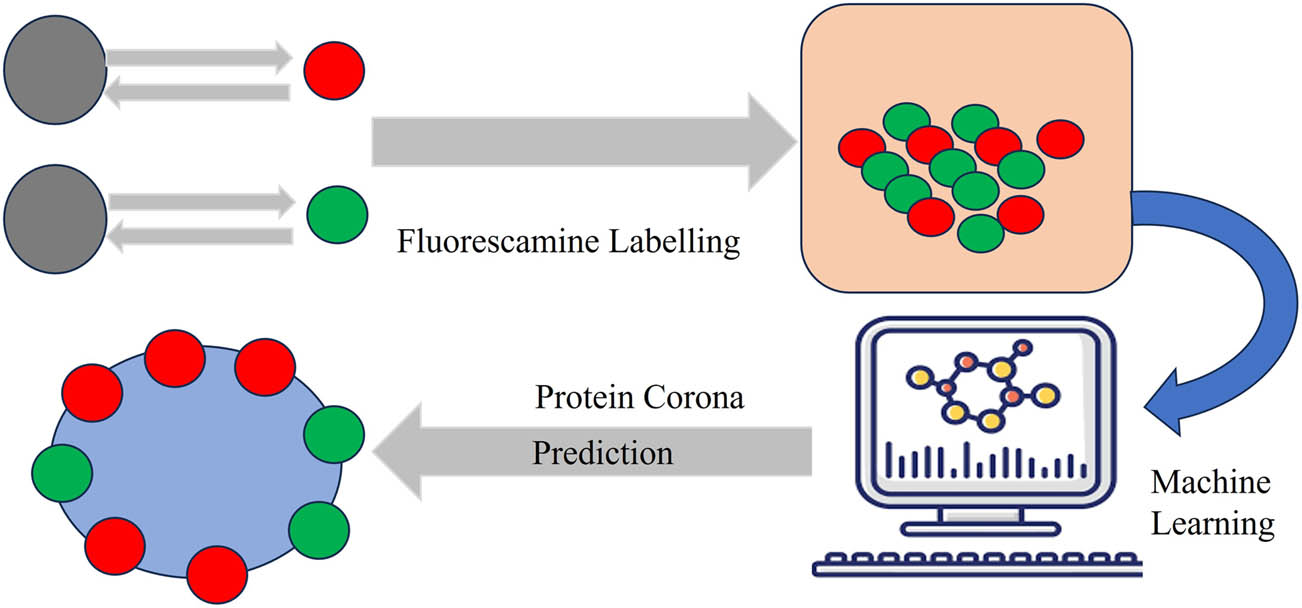

Encouragingly, advancements are being achieved in the characterization of the NP corona based on the physicochemical properties of NMs and the surrounding environment. Recent research has presented a range of mass spectrometric, spectroscopic, and chromatographic techniques aimed at evaluating NP coronas. Among these methods are some that allow the analysis of the evolving properties of biocoronas over time (Figure 5) [186–194]. These results in the creation of descriptive and potentially predictive models for the conformation of NP corona [129,195–197] and its active behaviour. These models lay the basis for the rational design and progress of NMs aimed at reducing or fully avoiding corona formation [198].

Fluorescence levels to correlate with the number of associated proteins in the corona of various NMs.

Considering solubility and biopersistence is paramount in the assessment of nanosafety, as these factors directly impact internal exposure to NMs. The main source of biological activity in soluble NMs may arise primarily from the liquefied substance rather than the NP itself, as exemplified by ZnO. The dissolution rate is subjective to various physical characteristics of NPs (size, particle shape, coating, shape, core doping), allowing potential opportunities for rationally controlling dissolution to reduce hostile biological effects [152]. Regardless of its critical significance, there remains uncertainty regarding which features of NMs impact solubility and, more specifically, biopersistence [199]. Further research is needed to comprehend how the dissolution of NMs in biological liquids or their perseverance in the body influences biodistribution and biological effects, and how these processes can be improved through formulations, coatings, or other approaches.

3.4.6 Descriptors

Molecular descriptors, capturing the necessary structural and physicochemical qualities of NMs, are pivotal components in computational modelling studies across various scientific domains, including environmental/medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, genomics, and drug design [200,201]. These descriptors can be created either through theoretical techniques or standard experiments. Theoretical descriptors offer diverse chemical property sources and wide coverage of the chemical features space, providing an extensive representation of NMs. However, experimentally derived descriptors, such as shape, size, solubility, and agglomeration, have limited applicability in ML models for biological effects due to their resource-intensive nature and unavailability for hypothetical materials [202]. Numerous theoretically sound descriptors can be calculated directly from molecular structures using different software packages [203]. Nevertheless, existing molecular descriptors and fingerprints primarily result from pharmaceuticals specifically designed for organic small molecules, lacking specificity for NMs. The unique challenges posed by NMs, such as polydispersity, complex interactions, and incomplete characterization, necessitate the development of nanospecific descriptors. DL, coupled with imaging methods, offers a promising avenue for generating such descriptors. Russo et al. [204] utilized CNNs to digitize complex nanostructures, allowing the training of predictive models for NP biological properties.

The interpretability of NM descriptors is crucial for understanding the mechanisms behind biological responses and for the rational design of improved materials. Traditional descriptors often lack interpretability, prompting the need for descriptors that are easily related to chemically recognizable features. De et al. [205] and Sizochenko et al. [206] proposed efficient and interpretable methods for encoding NM properties. De et al. [205] utilized 23 descriptors derived from the periodic table, while Sizochenko employed a “liquid drop” model and a simple representation of molecular structure for NPs.

3.4.7 Domain

ML models are essential tools in predicting NM properties, yet their efficacy is constrained by the limited datasets available, covering only a limited range of biological and physicochemical attributes [207]. The scarcity of diverse and large datasets represents a major impediment to the widespread adoption of ML techniques for NMs’ biological characteristics [208]. Computational models determine greater efficacy when operating within the multidimensional space described by different descriptors and biological reactions contained in the training data, and their reliability diminishes as predictions move further from this domain [37].

Novel modelling techniques, such as nearest neighbor Gaussian processes [37], and current ML approaches leveraging Bayesian statistics [208], offer avenues to estimate the prediction reliability. As larger and more diverse datasets become available, coupled with the adoption of ML methods that better gauge prediction uncertainties, the challenges associated with “out of domain” predictions are expected to decrease [37]. The prediction associated with in vivo responses to NMs remains a persistent challenge, primarily due to ethical, time, and cost constraints limiting experimental in vivo data generation [209,210]. By employing effective design of experiment techniques to minimize in vivo experiments and leveraging ML models, predictions within the models’ domains of applicability can be made. However, constraints on experimental in vivo testing are likely to persist, prompting the exploration of surrogate bioassays like toxicogenomics or new phenotypic assays [209,210].

The rapid advancement of high-throughput “omics” techniques, encompassing proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics, allows for the generation of extensive datasets on cellular or organism responses to NM exposure [209,210]. ML modelling methods can exploit these data by using expression profiles as descriptors to enhance predictions of in vivo responses and by employing measured nanodescriptors to model associations between NM omics signatures or pathways and physicochemical properties identified using expression profiling [211]. Furxhi et al. [211] employed physicochemical descriptors alongside experimental conditions to model biological results from genome-wide studies, demonstrating the potential of Bayesian networks. The integration of omics data with ML further contributes to modelling toxicological properties of NMs for risk assessment and safety [18–20]. Metabolomics, offering insights into metabolic dysregulation caused by NM exposure, is a valuable tool for risk assessment [212]. Metabolic and genomic fingerprints, coupled with sparse attribute selection and feature importance techniques, facilitate the training of predictive ML models for evaluating potential adverse biological characteristics of NMs.